![]()

Manner of Odilon Redon, Vase of Flowers, after 1928

| Artist | Manner of Odilon Redon, French, 1840–1916 |

| Title | Vase of Flowers |

| Object Date | after 1928 |

| Alternate and Variant Titles | Vase fleuri |

| Medium | Pastel on paper |

| Dimensions (Unframed) | 26 3/4 x 20 1/4 in. (68 x 51.4 cm) |

| Signature | Signed lower right: ODILON REDON |

| Credit Line | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Purchase: the Kenneth A. and Helen F. Spencer Foundation Acquisition Fund, F76-1 |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Manner of Odilon Redon, Vase of Flowers, after 1928,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.722.5407.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Manner of Odilon Redon, Vase of Flowers, after 1928,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.722.5407.

Vase of Flowers entered the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art collection in 1976 as an autograph work by Symbolist artist Odilon Redon (1840–1916). It came with a letter of certification from German art historian Klaus Berger, who had authored the first catalogue raisonné of Redon’s oeuvre (excluding his print production) in 1964.1See Klaus Berger, Odilon Redon: Fantasy and Colour, trans. Michael Bullock (1964; London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1965). After examining the pastel closely in person, Berger determined that it was “entirely by Odilon Redon’s hand” and “in near perfect condition.”2Letter of certification from Klaus Berger, October 26, 1974, NAMA curatorial files. “Le soussigné, Klaus Berger, déclare et certifie que le pastel reproduit au verso que j’ai pu examiner à loisir est entièrement de la main d’Odilon Redon. . . . Il est en état presque parfait” (I, the undersigned, Klaus Berger, declare and certify that the verso pastel, which I was able to examine at my leisure, is entirely by Odilon Redon’s hand. . . . It is in near perfect condition). All translations are by Brigid M. Boyle, unless otherwise noted. He proposed a date of 1911 or 1912 on stylistic grounds, noting that the still life possessed “all the properties” of Redon’s so-called “crystalline” period.3In his monograph, Berger describes a “crystalline structure” typical of Redon’s mature floral pieces, namely those produced after his wife, Camille, inherited property in Bièvres in 1910. See Berger, Odilon Redon: Fantasy and Colour, 91. Subsequent scholars have not adopted this nomenclature. Of the Nelson-Atkins pastel, Berger wrote: “Il présente toute les qualités de sa meilleure période dite “cristalline”” (It displays all the qualities of his best, so-called “crystalline” period). Letter of certification from Klaus Berger, October 26, 1974, NAMA curatorial files. Berger’s confident assessment, which he probably undertook at the request of Belgian dealer Andrée Stassart (b. 1925), helped persuade museum trustees of the picture’s merits. The Nelson-Atkins acquired Vase of Flowers from Stassart with funding from local philanthropist Helen Foresman Spencer, who can be seen posing beside the pastel with museum director Laurence Sickman at the opening of the Spencer Impressionist Gallery on February 22, 1976 (Fig. 1).

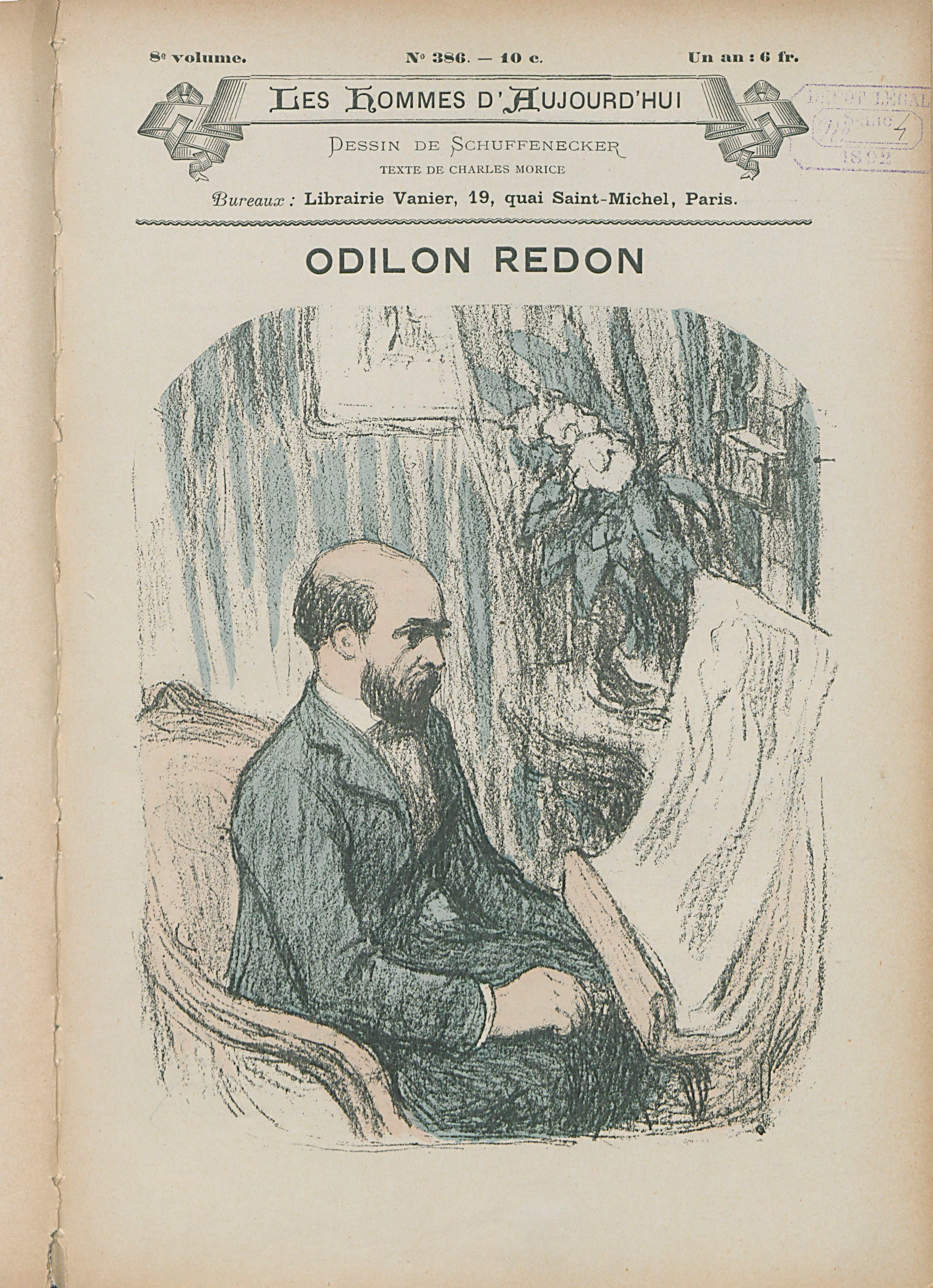

Although Redon studied painting under Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904) at the École des Beaux-Arts in 1864, he gravitated early on to charcoal drawings and prints. It was not until the mid-1870s that he began experimenting with pastel, right as Jean-François Millet (1814–1875) and Edgar Degas (1834–1917) were spearheading a pastel revival.10Harriet K. Stratis, “Beneath the Surface: Redon’s Methods and Materials,” in Douglas W. Druick et al., Odilon Redon: Prince of Dreams, 1840–1916, exh. cat. (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 1994), 367–68. This revival was the subject of the exhibition Peasants in Pastel: Millet and the Pastel Revival, Getty Center, Los Angeles, October 29, 2019–May 10, 2020. For two pastels by Degas in the Nelson-Atkins collection, see Dancer Making Points (ca. 1874–1876) and Rehearsal of the Ballet (ca. 1876). Initially, Redon relied on charcoal underdrawings to guide his application of pastel, but as he grew more confident in his handling he abandoned this practice.11Stratis, “Beneath the Surface,” 372. Over time, pastel pictures superseded his work in black and white. At the March 1899 exhibition of avant-garde artists at the Galerie Durand-Ruel, art critic Julien Leclercq noted Redon’s shift in media and said his pastels displayed “the same lovely qualities of mystery and inner passion” as his drawings.12Julien Leclercq, “Petites expositions,” La Chronique des arts et de la curiosité, no. 11 (March 18, 1899): 95. “Les mêmes belles qualités de mystère et de passion intérieure.” By Redon’s final years, his commitment to pastel was such that he described himself as a “simple pastellist” in a letter to his son, Arï.13Odilon Redon to Arï Redon, July 10, 1915, in Lettres d’Odilon Redon, 1878–1916, publiées par sa famille (Paris and Brussels: G. Van Oest et Cie, 1923), 132. “Je ne suis qu’un simple pastelliste” (I am only a simple pastellist).

Coinciding with the surge in Redon’s pastel production was his embrace of new subject matter. Where previously Redon’s oeuvre had been dominated by biblical heroes, mythological figures, portraits, humanoid monsters, and dream fragments, he turned increasingly to flower pictures in the 1890s. Since their heyday in seventeenth-century Dutch art, floral still lifes had declined in popularity, but they made a comeback in nineteenth-century France.14See Heather MacDonald and Mitchell Merling, Working Among Flowers: Floral Still-Life Painting in Nineteenth-Century France, exh. cat. (Dallas: Dallas Museum of Art, 2014); and “The Revival of the Floral Still Life” in Colta Ives, Public Parks, Private Gardens: Paris to Provence, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2018), 127–63. Margret Stuffmann posits that Redon drew inspiration from Eugène Delacroix’s (1798–1863) forays into this genre.15Margret Stuffmann and Max Hollein, eds., Odilon Redon: As in a Dream, exh. cat. (Ostfildern, Germany: Hatje Cantz, 2007), 288. It is also likely that Redon’s interest in flowers stemmed from his decades-long friendship with botanist Armand Clavaud. A professor at the Jardin des Plantes in Bordeaux, Clavaud not only published a catalogue of flowers native to that region but also researched the metaphysical dimensions of plants, arguing that each species had “its own living personality.”16Barbara Larson, The Dark Side of Nature: Science, Society, and the Fantastic in the Work of Odilon Redon (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2005), 10. Clavaud’s magnum opus, Flore de la Gironde, appeared in two volumes between 1881 and 1884. For more on Clavaud’s life and career, see Nancy Davenport, “Odilon Redon, Armand Clavaud, and Benedict Spinoza: Nature as God,” Religion and the Arts 10, no. 1 (March 2006): 1–38. Redon, who met Clavaud around 1857 and remained close with him until the latter’s death in 1890, found this idea compelling. He developed an appreciation for the natural world, writing in his journal: “I love nature in all her forms; I love her in the smallest blade of grass, the humble flower, tree, grounds, and rocks, up to the majestic peaks of mountains.”17Odilon Redon, To Myself: Notes on Life, Art and Artists, trans. Mira Jacob and Jeanne L. Wasserman (1979; New York: George Braziller, 1986), 86–87.

Contemporaries of Redon responded enthusiastically to his flower pictures. Parisian industrialist Arthur Fontaine wrote that Redon’s blooms seemed to be made of “a sublime, precious, and mysterious substance; they enclose light.”21Arthur Fontaine to Odilon Redon, June 23, 1904, in Roseline Bacou, ed., Lettres de Gauguin, Gide, Huysmans, Jammes, Mallarmé, Verhaeren . . . à Odilon Redon (Paris: Librairie José Corti, 1960), 291. “Elles sont d’une matière admirable, précieuse et mystérieuse; elles enferment de la lumière.” Marius-Ary Leblond, a shared pen name for art critics Georges Athénas and Aimé Merlo, perceived spiritual undertones in his floral still lifes. They described them as “Nativities of flowers” and claimed that Redon “sees flowers in the heavens just as the ancient painters of the Virgin Mary and the Christ Child, from Giotto to Da Vinci, saw cherubs there.”22Marius-Ary Leblond, “Odilon Redon: Le merveilleux dans la peinture,” La Revue illustrée, no. 1 (December 20, 1906): 160. “Il voit des fleurs dans le ciel comme les anciens peintres de la Madone et de l’Enfant, de Giotto à Vinci, y voyaient de petits anges.” This positive reception stoked demand for Redon’s floral works. By the early 1900s, an “ever-broadening audience” of collectors was clamoring for them, creating a market for copies.23Kevin Sharp, “Redon and the Marketplace before 1900,” in Druick et al., Odilon Redon, 270. According to art historian David Freeman, who founded a consultancy specializing in fine art authentication and fraud detection, Redon’s flower pictures are “quite often faked” and imitated.24See “Odilon Redon: Art Authentication and Attribution Investigation,” FreemanArt Consultancy, accessed May 31, 2022, http://www.freemanart.ca/Redon.htm. Several floral still lifes by the “circle of Odilon Redon” or similar have appeared at auction in recent years.25See, for example, Important Annual Spring Antiques and Fine Art Auction, Nadeau’s Auction Gallery, Windsor, CT, April 11, 2015, lot 256A, Circle of Odilon Redon, Still Life of Flowers in a Vase; and Art européen, art canadien, mobilier, antiquités et objets de collection, Fraser-Pinney’s Auction, Montreal, November 23, 1993, lot 65, Attributed to Odilon Redon, Flowers in a Blue Vase.

On the one hand, Vase of Flowers evinces many of the qualities that scholars associate with Redon’s floral works, supporting a possible attribution to the artist. More than two dozen blossoms of varying hues, shapes, and sizes are clustered in a pearlescent vase. Some of these flowers are recognizable, such as the red nasturtium and poppy on the left side of the bouquet, the blue and white anemones to their right, and the daisies at top; others, however, may be products of the artist’s imagination. Unlike in Redon’s painting The Green Vase, where the titular vessel rests on a flat surface, here the vase is unanchored in space. Seemingly weightless, it floats unsupported against a yellow-orange background, surrounded by butterflies and scattered petals. This flattening of space is typical of Redon’s mature still lifes.26Berger, Odilon Redon: Fantasy and Colour, 90.

On the other hand, the vessel featured in Vase of Flowers does not appear in any of Redon’s acknowledged works. Alec Wildenstein and Agnès Lacau St. Guilly identified eighty-one different vases, pots, and pitchers that Redon used for 332 still lifes.27Wildenstein and Lacau St. Guily, Odilon Redon, 7–10. Certain vessels are simple and utilitarian, while others are highly ornamental. Several vases recall ceramic wares that Redon could have seen at world fairs, the Louvre, or the Musée de Cluny, and a select few are vases made by Redon’s friend, Russian potter Maria Sergeevna Botkina (1870–1960).28Wildenstein and Lacau St. Guily, Odilon Redon, 5. For an example of Botkina’s handiwork, see Odilon Redon, Bouquet of Flowers, ca. 1900–1905, pastel on paper, 31 5/8 x 25 1/4 in. (80.3 x 64.1 cm), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 56.50. None of the containers in the Wildenstein inventory are a precise match for the one in the Nelson-Atkins pastel, however, which is narrow at the bottom, bulbous in the middle, tapered toward the rim, and lacking in handles or decorative motifs. Its closest equivalent in shape and simplicity of design is a blue vase in a privately owned Redon still life (Fig. 3).29See Impressionist and Modern Paintings and Sculpture, Part I (New York: Sotheby’s, November 15, 1989), lot 44, Vase de fleurs. This pastel corresponds to cat. 1573 in the Wildenstein catalogue raisonné. Other vases with similar silhouettes appear in cats. 1574–76, 1637–47, and 1648–65.

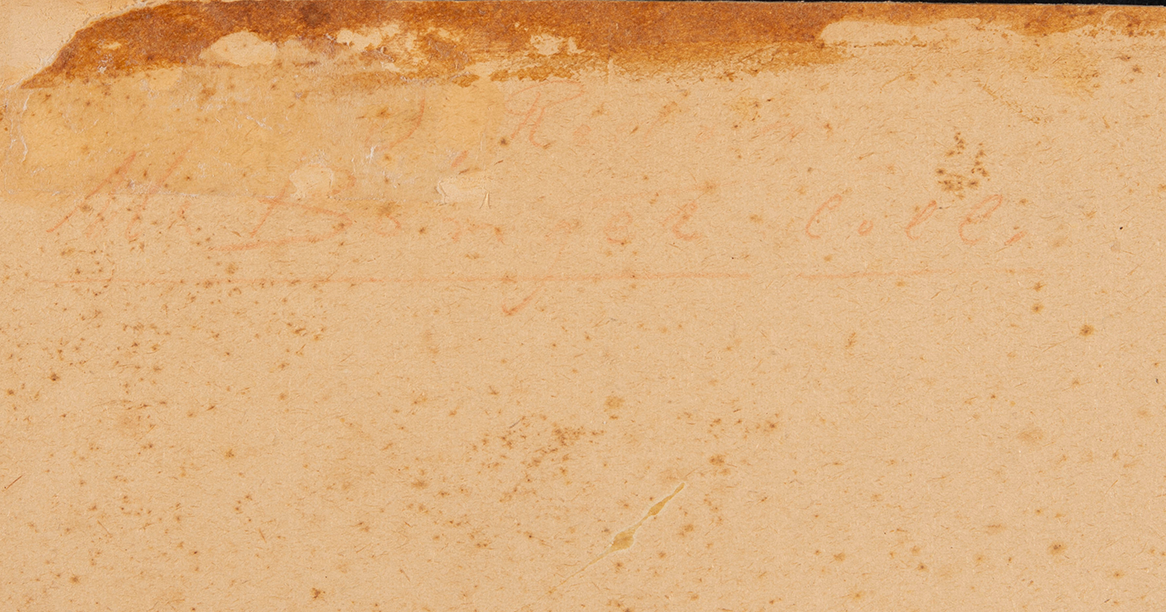

Fig. 4. Detail of verso of Manner of Odilon Redon, Vase of Flowers (after 1928): inscription in red wax pencil that reads, “[O]. Redon / M. Bo[n]ger coll.”

Fig. 4. Detail of verso of Manner of Odilon Redon, Vase of Flowers (after 1928): inscription in red wax pencil that reads, “[O]. Redon / M. Bo[n]ger coll.”

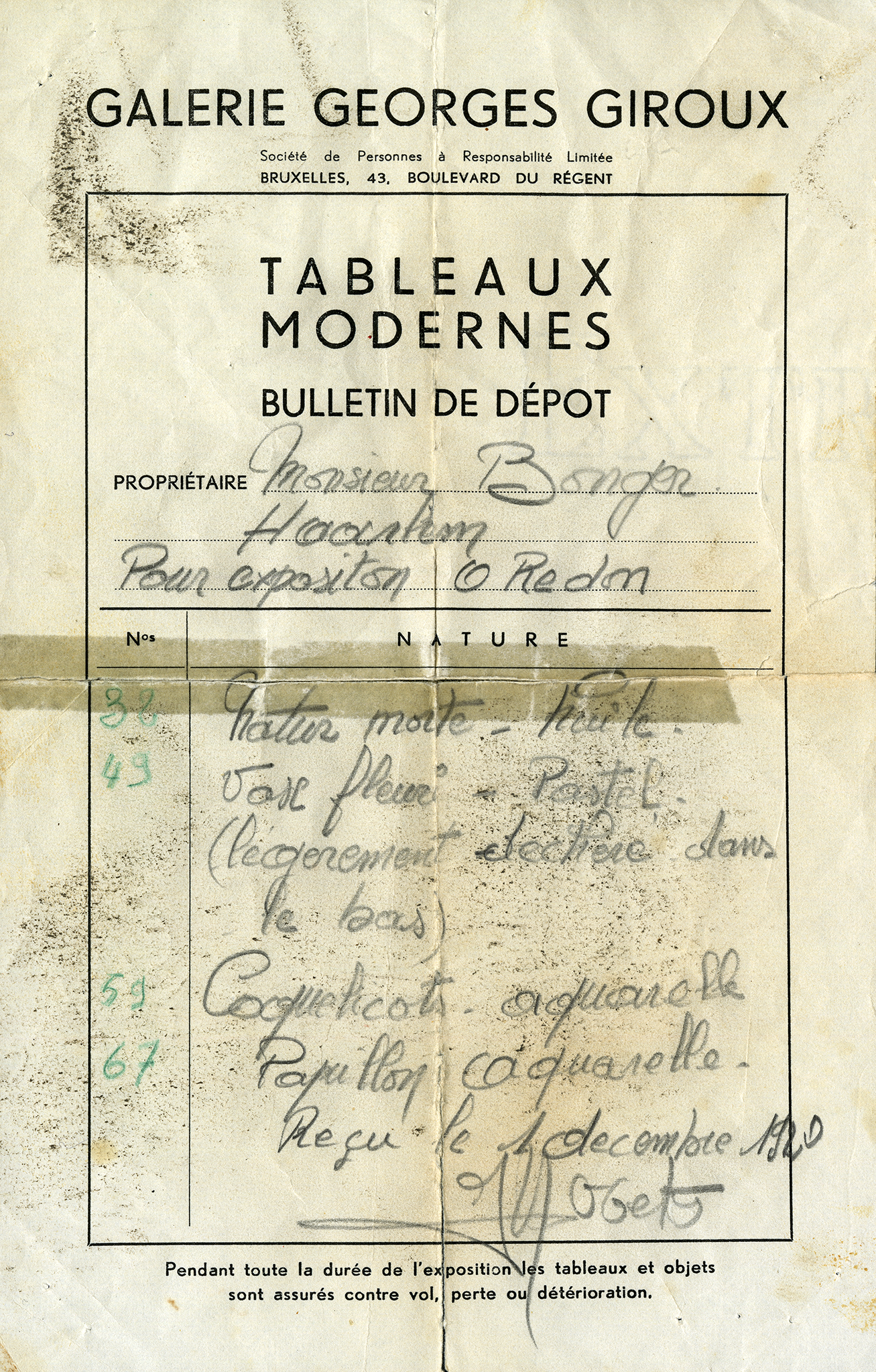

Fig. 5. Galerie Georges Giroux deposit receipt acknowledging delivery of four works by Odilon Redon for a retrospective on the artist, December 1, 1920, NAMA registration files. The receipt reads: “Vase fleuri – pastel / (légèrement déchiré dans / le bas)” (Vase of Flowers – pastel / [slightly torn at / the bottom])

Fig. 5. Galerie Georges Giroux deposit receipt acknowledging delivery of four works by Odilon Redon for a retrospective on the artist, December 1, 1920, NAMA registration files. The receipt reads: “Vase fleuri – pastel / (légèrement déchiré dans / le bas)” (Vase of Flowers – pastel / [slightly torn at / the bottom])

Moreover, if Bonger did indeed own Vase of Flowers and lend it to the Galerie Georges Giroux in 1920, one would expect to find a paper trail in the Bonger archive at the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. Bonger kept detailed records of his purchases and sales for insurance purposes, but Redon expert Fred Leeman found no reference to Vase of Flowers in Bonger’s extant records.41Fred Leeman, independent art historian, to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, October 26, 2020, NAMA curatorial files. He is also unaware of any connection between Bonger and Léonard de Selliers de Moranville, though he notes that Bonger’s business correspondence was destroyed after his death; the men may have been professional acquaintances.42Fred Leeman, independent art historian, to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, October 26, 2020, and January 4, 2021, NAMA curatorial files. When presented with the Galerie Georges Giroux receipt, Leeman speculated that Bonger could have lent Vase of Flowers on behalf of Redon’s widow, which might explain its absence from Bonger’s “otherwise meticulous and complete archive.” Fred Leeman to Brigid M. Boyle, January 28, 2021, NAMA curatorial files. A member of the Committee Odilon Redon at the Wildenstein Plattner Institute, Leeman could not comment directly on the pastel’s authenticity. Belgian historian Norbert Hostyn, who published an article on Léonard de Selliers de Moranville and knew his son-in-law, violinist Lucien Van Branteghem (1910–1994), was likewise surprised to learn of Léonard and Bonger’s friendship. Hostyn knew nothing of Léonard’s collecting activities and remarked that Van Branteghem “never told me about a Redon in the family.”43Norbert Hostyn, independent art historian, to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, January 4–5, 2021, NAMA curatorial files. Further research has shed no light on Léonard and Bonger’s relationship, and all evidence points to Léonard’s acquisition of the Nelson-Atkins pastel being anomalous.

Ultimately, although Raoul’s testimony corroborated some of the provenance data on Stassart’s précis, the date and means by which his grandfather obtained Vase of Flowers remain unclear. The absence of the pastel from the Bonger archive, its disputed inclusion in the 1920–1921 Brussels exhibition, the additional signatures observed by Heugh, and the anachronous pigments cast serious doubt on the work’s autograph status. Despite the picture’s luminous palette and otherworldly ambiance, so characteristic of Redon’s floral arrangements, it is likely by another’s skilled hand.

Notes

-

See Klaus Berger, Odilon Redon: Fantasy and Colour, trans. Michael Bullock (1964; London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1965).

-

Letter of certification from Klaus Berger, October 26, 1974, NAMA curatorial files. “Le soussigné, Klaus Berger, déclare et certifie que le pastel reproduit au verso que j’ai pu examiner à loisir est entièrement de la main d’Odilon Redon. . . . Il est en état presque parfait” (I, the undersigned, Klaus Berger, declare and certify that the verso pastel, which I was able to examine at my leisure, is entirely by Odilon Redon’s hand. . . . It is in near perfect condition). All translations are by Brigid M. Boyle, unless otherwise noted.

-

In his monograph, Berger describes a “crystalline structure” typical of Redon’s mature floral pieces, namely those produced after his wife, Camille, inherited property in Bièvres in 1910. See Berger, Odilon Redon: Fantasy and Colour, 91. Subsequent scholars have not adopted this nomenclature. Of the Nelson-Atkins pastel, Berger wrote: “Il présente toute les qualités de sa meilleure période dite ‘cristalline’” (It displays all the qualities of his best, so-called ‘crystalline’ period). Letter of certification from Klaus Berger, October 26, 1974, NAMA curatorial files.

-

The basis for Wildenstein’s initial rejection is unclear. Either the committee communicated its decision verbally to the Nelson-Atkins or a letter of notification from Wildenstein has been lost. It is unlikely that Wildenstein examined the pastel in person.

-

See Roger Ward, NAMA, to Ay-Huang Hsia, Wildenstein Institute, January 4, 1993, and Marie-Christine Decroocq, Wildenstein Institute, to Roger Ward, NAMA, January 15, 1993, NAMA curatorial files. Ward’s reply to Decroocq has been lost, so it is unclear whether he supplied any documentation.

-

Heugh-Edmondson Conservation Services, Technical Examination and Condition Report, October 10, 2012, NAMA conservation files, F76-1. One of the signatures is to the left of the vase; the other three are to the right. Another floral still life with two signatures, both of them visible in normal illumination, recently sold at auction as an autograph work by Redon; see Impressionist and Modern Works on Paper and Day Sale, Christie’s, New York, May 14, 2022, lot 733, Odilon Redon, Vase de fleurs, pastel on paper laid down on card, 27 3/4 x 19 1/4 in. (70.4 x 48.7 cm), https://www.christies.com/lot/lot-6369515. Curiously, neither the object information nor the lot essay acknowledges the presence of multiple signatures. The auction webpage notes that the pastel is “signed ‘ODILON REDON’ (lower left)” but makes no mention of the fainter signature at lower right. Unlike the Nelson-Atkins pastel, this floral still life appears in the Redon catalogue raisonné; see Alec Wildenstein and Agnès Lacau St. Guily, Odilon Redon: Catalogue raisonné de l’œuvre peint et dessiné, vol. 3, Fleurs et paysages (Paris: Wildenstein Institute, 1996), no. 1492, p. 95. For further details about this work’s inscriptions, condition, and mounting, see John Twilley, “Notes on ODILON REDON, Vase de fleurs, Christie’s sale 20682, lot 733,” May 6, 2022, NAMA conservation file, F76-1.

-

See “Research Proposal: Mellon Conservation Science Endowment,” August 12, 2021, NAMA conservation file, F76-1. As Freeman notes, Redon could afford new pastel supports at this stage in his career.

-

For the latter, see John Twilley, “Pigment Analyses for a Pastel Bearing Multiple Signatures ‘Odilon Redon,’ F76-1,” March 20, 2022, NAMA conservation file, F76-1.

-

The new date accounts for the presence of Pigment Blue 15:3, one of the polymorphic form of phthalocyanine blue, in a microsample taken by Twilley. This pigment was not invented until 1928. See Twilley, “Pigment Analyses for a Pastel,” 3.

-

Harriet K. Stratis, “Beneath the Surface: Redon’s Methods and Materials,” in Douglas W. Druick et al., Odilon Redon: Prince of Dreams, 1840–1916, exh. cat. (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 1994), 367–68. This revival was the subject of the exhibition Peasants in Pastel: Millet and the Pastel Revival, Getty Center, Los Angeles, October 29, 2019–May 10, 2020. For two pastels by Degas in the Nelson-Atkins collection, see Dancer Making Points (ca. 1874–1876) and Rehearsal of the Ballet (ca. 1876).

-

Stratis, “Beneath the Surface,” 372.

-

Julien Leclercq, “Petites expositions,” La Chronique des arts et de la curiosité, no. 11 (March 18, 1899): 95. “Les mêmes belles qualités de mystère et de passion intérieure.”

-

Odilon Redon to Arï Redon, July 10, 1915, in Lettres d’Odilon Redon, 1878–1916, publiées par sa famille (Paris and Brussels: G. Van Oest et Cie, 1923), 132. “Je ne suis qu’un simple pastelliste” (I am only a simple pastellist).

-

See Heather MacDonald and Mitchell Merling, Working Among Flowers: Floral Still-Life Painting in Nineteenth-Century France, exh. cat. (Dallas: Dallas Museum of Art, 2014); and “The Revival of the Floral Still Life” in Colta Ives, Public Parks, Private Gardens: Paris to Provence, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2018), 127–63.

-

Margret Stuffmann and Max Hollein, eds., Odilon Redon: As in a Dream, exh. cat. (Ostfildern, Germany: Hatje Cantz, 2007), 288.

-

Barbara Larson, The Dark Side of Nature: Science, Society, and the Fantastic in the Work of Odilon Redon (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2005), 10. Clavaud’s magnum opus, Flore de la Gironde, appeared in two volumes between 1881 and 1884. For more on Clavaud’s life and career, see Nancy Davenport, “Odilon Redon, Armand Clavaud, and Benedict Spinoza: Nature as God,” Religion and the Arts 10, no. 1 (March 2006): 1–38.

-

Odilon Redon, To Myself: Notes on Life, Art and Artists, trans. Mira Jacob and Jeanne L. Wasserman (1979; New York: George Braziller, 1986), 86–87.

-

Redon did not have a studio proper. See Dario Gamboni, The Brush and the Pen: Odilon Redon and Literature, rev. ed., trans. Mary Whittall (1989; Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011), 206–7.

-

For a photograph of Camille Redon arranging flowers in a vase, see Jean Cassou, Odilon Redon (1971; Milan: Fratelli Fabbri, 1974), 12.

-

Odilon Redon to Andries Bonger, May 1, 1912, in Suzy Lézy, ed., Lettres inédites d’Odilon Redon à Bonger, Jourdain, Viñes . . . (Paris: Librairie José Corti, 1987), 220. “J’aime ces fleurs bien plus en vase sur la cheminée, que dans les champs plantées comme elles le sont nécessairement par plates-bandes d’une seule couleur.”

-

Arthur Fontaine to Odilon Redon, June 23, 1904, in Roseline Bacou, ed., Lettres de Gauguin, Gide, Huysmans, Jammes, Mallarmé, Verhaeren . . . à Odilon Redon (Paris: Librairie José Corti, 1960), 291. “Elles sont d’une matière admirable, précieuse et mystérieuse; elles enferment de la lumière.”

-

Marius-Ary Leblond, “Odilon Redon: Le merveilleux dans la peinture,” La Revue illustrée, no. 1 (December 20, 1906): 160. “Il voit des fleurs dans le ciel comme les anciens peintres de la Madone et de l’Enfant, de Giotto à Vinci, y voyaient de petits anges.”

-

Kevin Sharp, “Redon and the Marketplace before 1900,” in Druick et al., Odilon Redon, 270.

-

See “Odilon Redon: Art Authentication and Attribution Investigation,” FreemanArt Consultancy, accessed May 31, 2022, http://www.freemanart.ca/Redon.htm.

-

See, for example, Important Annual Spring Antiques and Fine Art Auction, Nadeau’s Auction Gallery, Windsor, CT, April 11, 2015, lot 256A, Circle of Odilon Redon, Still Life of Flowers in a Vase; and Art européen, art canadien, mobilier, antiquités et objets de collection, Fraser-Pinney’s Auction, Montreal, November 23, 1993, lot 65, Attributed to Odilon Redon, Flowers in a Blue Vase.

-

Berger, Odilon Redon: Fantasy and Colour, 90.

-

Wildenstein and Lacau St. Guily, Odilon Redon, 7–10.

-

Wildenstein and Lacau St. Guily, Odilon Redon, 5. For an example of Botkina’s handiwork, see Odilon Redon, Bouquet of Flowers, ca. 1900–1905, pastel on paper, 31 5/8 x 25 1/4 in. (80.3 x 64.1 cm), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 56.50.

-

See Impressionist and Modern Paintings and Sculpture, Part I (New York: Sotheby’s, November 15, 1989), lot 44, Vase de fleurs. This pastel corresponds to cat. 1573 in the Wildenstein catalogue raisonné. Other vases with similar silhouettes appear in cats. 1574–76, 1637–47, and 1648–65.

-

See undated précis on Stassart’s letterhead, NAMA curatorial files.

-

Statement of certification from Raoul de Selliers de Moranville, April 27, 1974, NAMA curatorial files. The work “a été acheté ou échangé par mon grand-père le chevalier L. de Selliers de Moranville à Monsieur Bonger qui était un excellent ami. Ce pastel a été vendu par moi-même en 1972 à la baronne Gacionia habitant Palerme.” Selliers de Moranville may have misspelled the baroness’s surname; Giaconia is a fairly common surname in Palermo, but Gacionia is virtually nonexistent.

-

See Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, to Stassart’s daughter, Claude Deloffre, January 20, 2021, NAMA curatorial files. A native of Liège, Stassart moved to Paris sometime after World War II and organized exhibitions of modern art at premises near the Bois de Boulogne. She remained active in the art trade until at least the mid-1980s. The only other artwork that Stassart sold to the Nelson-Atkins was Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s (1841–1919) bronze sculpture The Large Bather (F77-57). I am grateful to Nancy E. Edwards, Curator of European Art/Head of Academic Services, Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth; and Victoria Reed, Sadler Curator of Provenance, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, for sharing information about Stassart.

-

For a concise biography of Léonard de Selliers de Moranville, see Norbert Hostyn, “Vergeten Oostendse kunstschilders: Léonard de Selliers de Moranville,” De Plate 10, no. 12 (December 1981): 243. For the Selliers de Moranville coat of arms, see Oscar Coomans de Brachène, État présent de la noblesse belge (Brussels: Collection “Etat présent,” 1981), 106. I am grateful to Marc Libert, Archives Générales du Royaume de Belgique, Brussels; and Patricia le Grelle, Association de la Noblesse du Royaume de Belgique, Brussels, for their assistance with genealogical research. I refer to Léonard and Raoul by their first names rather than their shared surname so as to distinguish them.

-

It has not been possible to contact Mr. Dehon. Raoul could not recall Dehon’s first name but remembered that his son, Richard Dehon, formerly worked for Radiotélévision Belge Francophone (RTBF) in Brussels. Emails to RTBF went unanswered. See Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, to Christine Thiran, RTBF, December 29, 2020, and January 26, 2021, NAMA curatorial files.

-

For this paragraph, see Raoul de Selliers de Moranville to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, December 28 and 29, 2020, NAMA curatorial files.

-

Stassart could also have confused Andries Bonger with his younger brother, criminologist Willem Adriaan Bonger (1876–1940).

-

Fred Leeman, Odilon Redon and Emile Bernard: Masterpieces from the Andries Bonger Collection, exh. cat. (Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum, 2009), 11, 57. For more on Bonger, see Roseline Bacou, “The Bonger Collection at Almen, Holland,” Apollo 80, no. 33 (November 1964): 398–401; J. L. Locher, Vormgeving en structuur: Over kunst en kunstbeschouwing in de negentiende en twintigste eeuw (Amsterdam: Meulenhoff, 1973), 98–125; Henk Bonger, “Un Amstellodamois à Paris: Extraits des lettres écrites à Paris entre 1880 et 1890 par Andries Bonger à ses parents à Amsterdam,” in ed. Dieuwke de Hoop Scheffer, Carlos van Hasselt, and Christopher White Liber amicorum Karel G. Boon (Amsterdam: Swets en Zeitlinger, 1974), 61–70; and Suzy Lévy, Odilon Redon et le Messie féminin (Paris: Cercle d’art, 2007), 61–70.

-

The exhibition opened on December 18, 1920, and closed on January 8, 1921.

-

See Alec Wildenstein and Marie-Christine Decroocq, Odilon Redon: Catalogue raisonné de l’œuvre peint et dessiné, vol. 4, Études et grandes décorations; Supplément (Paris: Wildenstein Institute, 1998), 342.

-

Olivier Bertrand, Belart International, to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, June 7, 2022, NAMA curatorial files.

-

Fred Leeman, independent art historian, to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, October 26, 2020, NAMA curatorial files.

-

Fred Leeman, independent art historian, to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, October 26, 2020, and January 4, 2021, NAMA curatorial files. When presented with the Galerie Georges Giroux receipt, Leeman speculated that Bonger could have lent Vase of Flowers on behalf of Redon’s widow, which might explain its absence from Bonger’s “otherwise meticulous and complete archive.” Fred Leeman to Brigid M. Boyle, January 28, 2021, NAMA curatorial files. A member of the Committee Odilon Redon at the Wildenstein Plattner Institute, Leeman could not comment directly on the pastel’s authenticity.

-

Norbert Hostyn, independent art historian, to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, January 4–5, 2021, NAMA curatorial files.

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Rachel Freeman, “Manner of Odilon Redon, Vase of Flowers, after 1928,” technical entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.722.2088.

MLA:

Freeman, Rachel. “Manner of Odilon Redon, Vase of Flowers, after 1928,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.722.2088.

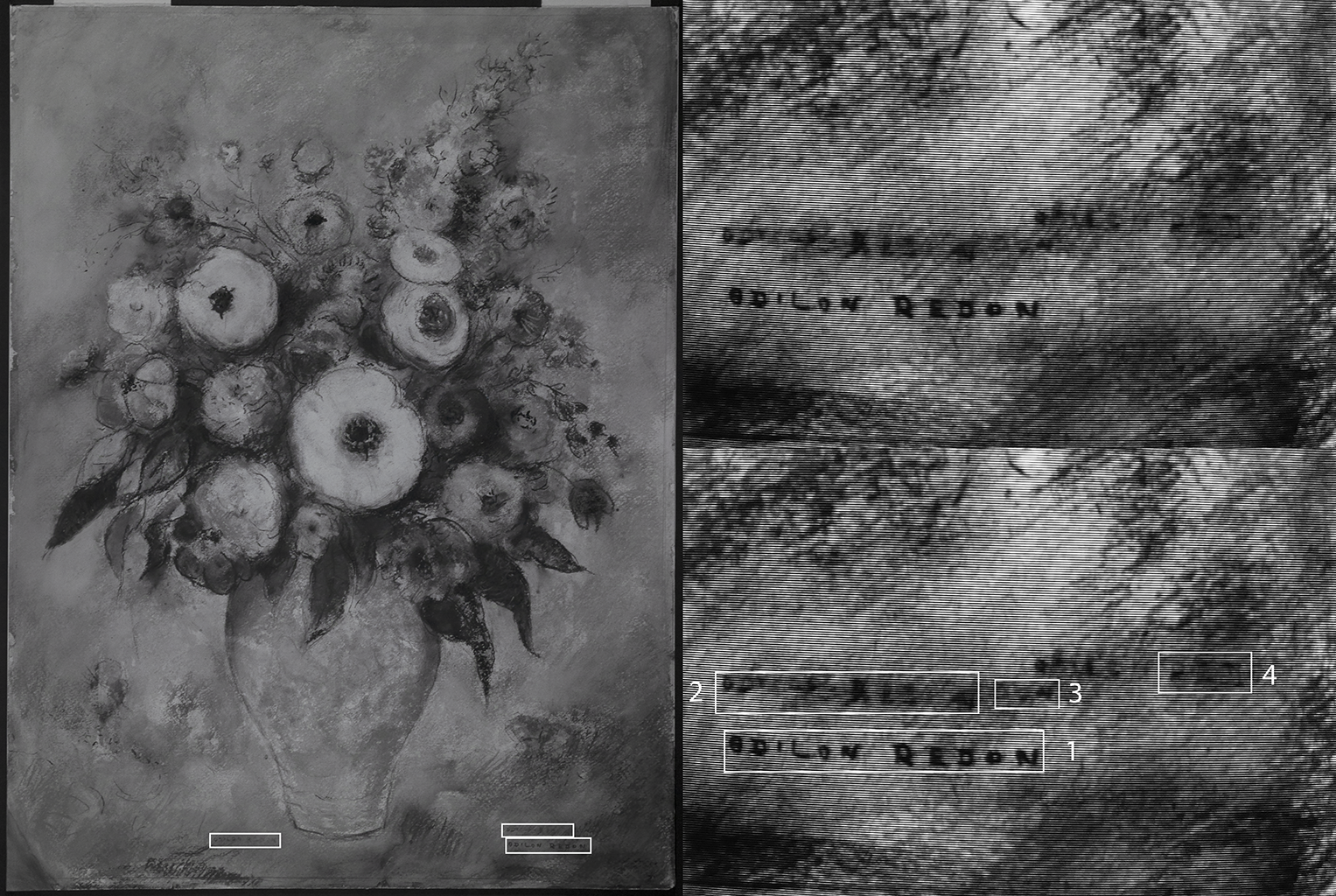

Vase of Flowers, originally accessioned as an autograph pastel painting by Odilon Redon, is an enigmatic artwork. While the subject matter is consistent with Redon’s late still lifes of flowers and vases, inconsistencies in technique and material choices, as well as a multiplicity of signatures, raise doubts about its authenticity. Analysis of the pastel determined that it is partly composed of materials that did not come into use until after Redon’s death. This entry briefly discusses the materiality of Vase of Flowers and how the materials and techniques present in the artwork differ from what is known of Redon’s later pastels.

Digital infrared (IR) photographyinfrared (IR) photography: A form of infrared imaging that employs the part of the spectrum just beyond the red color to which the human eye is sensitive. This wavelength region, typically between 700-1,000 nanometers, is accessible to commonly available digital cameras if they are modified by removal of an IR blocking filter that is required to render images as the eye sees them. The camera is made selective for the infrared by then blocking the visible light. The resulting image is called a reflected infrared digital photograph. Its value as a painting examination tool derives from the tendency for paint to be more transparent at these longer wavelengths, thereby non-invasively revealing pentimenti, inscriptions, underdrawing lines, and early stages in the execution of a work. The technique has been used extensively for more than a half-century and was formerly accomplished with infrared film.3Infrared Digital photograph captured using a Nikon D700 UV-VIS-IR modified camera with Kodak Wratten 87C filter. See also Notes to Reader. of the work revealed an underdrawingunderdrawing: A drawn or painted sketch beneath the paint layer. The underdrawing can be made from dry materials, such as graphite or charcoal, or wet materials, such as ink or paint.. Where visible in normal illumination, the underdrawing appears to be in a finely pointed, black pastel or compressed charcoalcompressed charcoal: A dry drawing material composed of charcoal, ground to a powder, and formed into a stick with aid of a small amount of a non-waxy and non-oily binder. The line created by compressed charcoal is characterized by a firm and dense appearance.. There are multiple layers of pastel on the work. In the initial layers, dull tans and beiges dominate the palette. Layered over these are the greens and blues of the leaves, the vibrant colors of the flowers, and the bright hues of the background. The intermediate layers of pastel are blended, but not to the extent that the first layers exhibit. The final layers are characterized by short, diagonally applied strokes of pastel in the background and outlines, individual strokes, and dots of color in the leaves and flowers. The upper layers of pastel are loose and powdery, and some of the whites in the flowers at the top of the bouquet appear to be opaque watercolor. Although there is no visual evidence of a fixativefixative: An adhesive or varnish that is applied to the surface of powdery media (pastel, chalk, charcoal, or graphite pencil) to prevent smudging or smearing. Fixatives may be applied during the composition process, so that new layers of media can be added without disturbing the underlayers, or after the artwork is complete. Historic fixatives include natural resins, vegetable gums or starches, animal or fish glues, casein, egg white, and a variety of other materials. In the nineteenth century, cellulose nitrate and other early synthetic polymers were available, and in the twentieth century, acrylics and polyvinyl co-polymers were included in fixative solutions. Until the early twentieth century, when methods for containing pressurized gasses were developed and disposable spray cans became common, the fixative could be spattered over the paper with a brush or applied with an atomizer (also called a blow-pipe or mouth sprayer).4In this entry, “fixative” refers to a dark brown substance applied (either purposefully or by accident) in a spatter pattern to the vase and background in this pastel. When the word appears without quotation marks, the indication is of a traditional artist’s fixative. between the layers of pastel, it is assumed to be present since the underlayers would be easily disturbed if left unfixed. There are a few small, dark brown spatters of a “fixative” within the vase and in the background immediately surrounding the bouquet.5The dark brown spatters were assumed to be a fixative by both Rachel Freeman and Nancy Heugh. See “Research Proposal: Mellon Conservation Science Endowment,” August 12, 2021, NAMA conservation file, F76-1, and Nancy Heugh, spring 2012, French Painting Catalogue Project Technical Examination and Condition Report, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, F76-1. See also Notes to Reader. At lower right, one signature, in pointed charcoal pencil, is visible in normal illumination. A faint letter “O” from another signature is also partially legible. The remainder of the signature is obscured by overlying pastel. With the aid of infrared reflectography (IRR)infrared reflectography (IRR): A form of infrared imaging that exploits the behavior of painting materials at wavelengths beyond those accessible to infrared photography. These advantages sometimes include a continuing increase in the transparency of pigments beyond wavelengths accessible to infrared photography (i.e, beyond 1,000 nanometers), rendering underdrawing more clearly. The resulting image is called an infrared reflectogram. Devices that came into common use in the 1980s such as the infrared vidicon effectively revealed these features but suffered from lack of sharpness and uneven response. Vidicons continue to be used out to 2,200 nanometers but several newer pixelated detectors including indium gallium arsenide and indium antimonide array detectors offer improvements. All of these devices are optimally used with filters constraining their response to those parts of the infrared spectrum that reveal the most within the constraints of the palette used for a given painting. They can be used for transmitted light imaging as well as in reflection.,6For specifications for the Hamamatsu C1000-03 vidicon camera, please see the Infrared Examination section in the Notes to Reader. The sensor (the lead sulfide tube) in the Hamamatsu C1000-03 is capable of recording wavelengths in the SWIR region (1000–2500 nm). Photographs of this type are called reflectograms. However, the only method for documenting the image is to photograph the Tektronics monitor screen. The infrared modified camera at The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art is capable of documenting wavelengths in the NIR region (700–1000 nm.) conservator Nancy Heugh noted a total of five probable signatures, one at lower left and four at lower right, including the two mentioned above.7Nancy Heugh, spring 2012, French Painting Catalogue Project Technical Examination and Condition Report, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, F76-1. The author of this entry documented all signatures in late 2020 (Fig. 7).

The reuse of a damaged support was also a cause for concern. Redon’s late career successes increased his income, making it possible for him to invest in new, quality materials. In contrast to the damaged support, the pastel maintains a vivid coloration overall, even though the colors in other pastel paintings by the artist are known to have faded significantly.10See Stratis’s commentary on The Boat and Orphelia in “Beneath the Surface: Redon’s Methods and Materials,” 374.

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art did not undertake a full analysis of the pastel on Vase of Flowers. Instead, pigment testing was carried out as the most expedient method of determining the age of the artwork. John Twilley, Mellon science advisor, removed microsamples of pigment from representative areas of the composition. Microsampling locations were selected based on visual, textural, and UV fluorescence behavior and included the restored lower left corner. Samples were analyzed by scanning electron microscopyscanning electron microscopy (SEM): Performed on a microsample of paint, the SEM provides a means of studying particle shapes beyond the magnification limits of the light microscope. This becomes increasingly important with the painting materials introduced in the early modern era, which are finer and more diverse than traditional artists’ materials. The SEM is routinely used in conjunction with an X-ray spectrometer, so that elemental identifications can be made selectively on the same minute scale as the electron beam producing the images. SEM methods are particularly valuable in studying unstable pigments, adverse interactions between incompatible pigments, and interactions between pigments and surrounding paint medium, all of which can have profound effects on the appearance of a painting. with elemental analysis provided by energy dispersive X-ray spectrometry (SEM-EDS)electron-beam-excited X-ray spectrometry (sometimes referred to as XES for “X-ray energy spectrometry” or EDX for “energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometry”): An analytical technique used for the identification of elements without regard to their state of combination. The underlying principle of X-ray spectrometry is the same as that of X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF): individual elements can be induced to emit unique identifying X-rays. When used during examination of a sample in the scanning electron microscope (SEM), it offers several profound advantages over in-situ analysis with the handheld unit or XRF elemental mapping spectrometer. Electron beam excitation in the SEM favors the response of light elements including even carbon and oxygen. Also, the extreme localization of the electron beam exciting the response allows individual pigment particles to be analyzed in complicated mixtures while simultaneously revealing particle shapes. For example, the presence of both lead and chromium in a single rod-like particle differentiates it as chrome yellow from the case of viridian merely mixed with lead white, where chromium (oxide) and lead (carbonate) occur in separate particles., by Raman spectroscopyRaman spectroscopy: A microanalytical technique applicable primarily to pigments and minerals, differentiating them based on both chemical bonding and crystal structure, often with extremely high sensitivity for individual particles. For example, traditional indigo and synthetic phthalocyanine blue are both carbon compounds not well differentiated by other methods utilized here, especially when used dilutely. However, they give unique Raman spectra. Calcium carbonates derived from chalk or pulverized oyster shell of identical chemical compositions can be differentiated based on their crystal structures (calcite and aragonite, respectively)., and by polarized light microscopy (PLM)polarized light microscopy (PLM): A method used for the study and differentiation of pigments based on the optical properties of individual particles, including color, refractive index, birefringence, etc. PLM is particularly useful in identifying the presence of organic pigments such as indigo and Prussian blue, which often cannot be differentiated from paint medium in the scanning electron microscopy (SEM); differentiating synthetic pigments from their natural analogs by particle shape or the presence of extraneous mineral matter; and disclosing the presence of pigments with similar composition but differing color, such as red and yellow iron oxides. of the dispersed pigment particles. The results demonstrated the presence of anatase titanium white in highlights in the vase and flowers in the bouquet and phthalocyanine blue in the bouquet.11John Twilley, “Pigment Analysis for a Pastel Bearing Multiple Signatures ‘Odilon Redon,’ F76-1,” March 20, 2022, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, F76-1. Titanium white was introduced in the early 1920s, while phthalo blue came into use in the 1930s. The presence of these pigments indicates that the creation of Vase of Flowers occurred after Redon’s death on July 6, 1916.

While portions of the pastel had a tough consistency suggesting impregnation by a fixative, the delicate surface precluded sampling for its identification. The “fixative” spatters on the surface of the pastel could be detached and were sampled for analysis by Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR): A broadly applicable microanalysis method for the identification of paint media classes such as oils, polysaccharides (gum arabic, etc.), proteins (glue and casein tempera), waxes (medium additions and restoration treatments), resins (varnish components), and synthetic media (restoration acrylics). FTIR is also very important for identifying pigments and fillers, and for differentiating closely-related compounds (e.g. neutral and basic lead carbonates, both of which may be found in lead white).. Evidence of glues—Redon’s fixative of choice with his pastels—was not present in the samples. Broad carbonyl peaks suggested the presence of a dried oil; however, as Twilley notes, the peaks were “too broad to be simply drying oildrying oil: Drying oils are oils which have the property of forming a solid, elastic substance when exposed to the air. Drying oils that commonly occur in oil paints are linseed, walnut, and poppyseed.” and might represent a non-artist material that accidently adhered to the surface of the artwork.

Technical examinations and chemical analyses of the materials both disclose problematic aspects of Vase of Flowers. While the pastel painting very closely replicates Redon’s late artistic interests, factors such as the numerous signatures, anachronistic pigments, and deviations from Redon’s typical materials and techniques indicate that the artwork was likely produced by an artist working in the manner of Redon’s luminous still lifes.

Notes

-

The description of paper color, texture, and thickness follows the standard set forth in Elizabeth Lunning and Roy Perkinson, The Print Council of America Paper Sample Book: A Practical Guide to the Description of Paper (Boston: Print Council of America, 1996), unpaginated.

-

In this entry, paperboard refers to “stiff and thick ‘paper’ which may range from a ‘card’ of 0.20 mm or 1/125th of an inch or more and vary in composition from pure rag to wood, straw, and other substances having little or no affinity with ‘paper’ beyond the method of manufacture.” See E. J. Labarre, A Dictionary of Paper and Paper-making Terms (Amsterdam: N.V. Swets and Zeitlinger, 1937), 208–09.

-

Infrared Digital photograph captured using a Nikon D700 UV-VIS-IR modified camera with Kodak Wratten 87C filter. See also Notes to Reader.

-

In this entry, “fixative” refers to a dark brown substance applied (either purposefully or by accident) in a spatter pattern to the vase and background in this pastel. When the word appears without quotation marks, the indication is of a traditional artist’s fixative.

-

The dark brown spatters were assumed to be a fixative by both Rachel Freeman and Nancy Heugh. See “Research Proposal: Mellon Conservation Science Endowment,” August 12, 2021, NAMA conservation file, F76-1, and Nancy Heugh, spring 2012, French Painting Catalogue Project Technical Examination and Condition Report, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, F76-1. See also Notes to Reader.

-

For specifications for the Hamamatsu C1000-03 vidicon camera, please see the Infrared Examination section in the Notes to Reader. The sensor (the lead sulfide tube) in the Hamamatsu C1000-03 is capable of recording wavelengths in the SWIR region (1000–2500 nm). Photographs of this type are called reflectograms. However, the only method for documenting the image is to photograph the Tektronics monitor screen. The infrared modified camera at The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art is capable of documenting wavelengths in the NIR region (700–1000 nm.)

-

Nancy Heugh, spring 2012, French Painting Catalogue Project Technical Examination and Condition Report, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, F76-1.

-

Harriet Stratis, “Beneath the Surface: Redon’s Methods and Materials,” in Douglas W. Druick et al., Odilon Redon: Prince of Dreams, 1840–1916, exh. cat. (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 1994), 354–77; and Harriet K. Stratis, “A Technical Investigation of Odilon Redon’s Pastels and Noirs,” The Book and Paper Group Annual of the American Institute for Conservation 14 (1995): 87–105.

-

Stratis, “A Technical Investigation of Odilon Redon’s Pastels and Noirs,” 104.

-

See Stratis’s commentary on The Boat and Orphelia in “Beneath the Surface: Redon’s Methods and Materials,” 374.

-

John Twilley, “Pigment Analysis for a Pastel Bearing Multiple Signatures ‘Odilon Redon,’ F76-1,” March 20, 2022, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, F76-1.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Manner of Odilon Redon, Vase of Flowers, after 1928,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.722.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Manner of Odilon Redon, Vase of Flowers, after 1928,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.722.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Manner of Odilon Redon, Vase of Flowers, after 1928,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.722.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Manner of Odilon Redon, Vase of Flowers, after 1928,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.722.4033.

Possibly Andries Bonger (1861–1936), Aerdenhout, The Netherlands, by December 1, 1920 [1];

Acquired from Bonger through purchase or exchange by Léonard-L.-Maurice-G. de Selliers de Moranville (1853–1946), Ostend, Belgium, no later than February 5, 1946 [2];

By descent to his grandson, Raoul-Léonard-Émile Bernard de Selliers de Moranville (b. 1942), Liège, Belgium, by February 5, 1946–1972 [3];

Purchased from the latter through Dehon, Schaerbeek, Belgium, by Baroness Giaconia, Palermo, Italy, 1972 [4];

With Andrée Stassart, Paris, by October 23, 1975–February 15, 1976 [5];

Purchased from Stassart by the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1976.

Notes

[1] For the possible date of acquisition, see the Galerie Georges Giroux, Bulletin de Dépôt, December 1, 1920, NAMA curatorial files, which acknowledges the receipt of four works from “Monsieur Bonger, Haarlem” for the Exposition rétrospective d’Odilon Redon, Galerie Georges Giroux, Brussels, December 18, 1920–January 8, 1921. The second work listed (no. 49, Vase fleuri, pastel) may be the Nelson-Atkins still life, although other scholars have previously identified no. 49 as Wildenstein cat. 1474 or 1512; see Alec Wildenstein and Marie-Christine Decroocq, Odilon Redon: Catalogue raisonné de l’œuvre peint et dessiné, vol. 4, Études et grandes décorations; Supplément (Paris: Wildenstein Institute, 1998), 342.

Vase of Flowers does not appear in Andries Bonger’s insurance inventories of his collection, which are housed at the Bonger Archive, Rijksmuseum Amsterdam; see emails from Fred Leeman, independent art historian, to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, October 26, 2020 and January 28, 2021, NAMA curatorial files. Leeman notes that Redon’s widow, Camille Redon (née Falte, 1853–1923) actively organized exhibitions and sales of her late husband’s work during the 1920s, and he speculates that Bonger could have acted as an intermediary in her sale of Vase of Flowers, which could explain its absence from the Bonger Archive. We have not been able to corroborate this suggestion, however.

A verso inscription on the Nelson-Atkins pastel reads: “[O]. Redon / M. Bo[n]ger Coll.”

[2] Selliers de Moranville was an artist, musician, and civil engineer; see Norbert Hostyn, “Vergeten Oostendse kunstschilders: Léonard de Selliers de Moranville,” De Plate 10, no. 12 (December 1981): 243. He and Bonger were supposedly close friends; see statement of certification from Raoul-Léonard-Émile Bernard de Selliers de Moranville, grandson of Léonard-L.-Maurice-G. de Selliers de Moranville, April 27, 1974, NAMA curatorial files. Selliers de Moranville passed away on February 5, 1946.

[3] Raoul-Léonard-Émile Bernard de Selliers de Moranville was only four years old when his grandfather passed away on February 5, 1946, so he is unsure exactly when the latter bequeathed the pastel to him. Raoul does not believe that his father, Maurice-Jules-Léonard de Selliers de Moranville (1911–1947), who died prematurely of typhus, ever owned the pastel. See emails from Raoul-Léonard-Émile Bernard de Selliers de Moranville to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, December 27 and 29, 2020, NAMA curatorial files.

[4] Raoul-Léonard-Émile Bernard de Selliers de Moranville cannot recall the first names of either Dehon, whom he described as an “expert en œuvre d’art,” or Baroness Giaconia; see email to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, December 29, 2020, NAMA curatorial files.

[5] Andrée Stassart (b. 1925) and her husband, Alexander N. Donskoy, were both dealers active in Paris. The pastel was in Stassart’s possession by autumn 1975; see letter from Ralph T. Coe, NAMA, to Andrée Stassart, October 23, 1975, NAMA curatorial files. She may have acquired it as early as April 27, 1974, the date that Klaus Berger (1901–2000), a retired art historian living in Paris, certified its authenticity, possibly at her request; see statement of certification by Klaus Berger, April 27, 1974, NAMA curatorial files.

The Nelson-Atkins paid for the purchase in two installments, the second of which was delivered on February 15, 1976; see letter from Andrée Stassart to Ralph T. Coe, NAMA, January 17, 1976, NAMA curatorial files.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Manner of Odilon Redon, Vase of Flowers, after 1928,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.722.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Manner of Odilon Redon, Vase of Flowers, after 1928,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.722.4033.

Possibly Exposition rétrospective d’Odilon Redon, Galerie Georges Giroux, Brussels, December 18, 1920–January 8, 1921, no. 49, as Vase fleuri.

Dürer to Matisse: Master Drawings from the Permanent Collection, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, July 12–September 6, 1998, hors. cat.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Manner of Odilon Redon, Vase of Flowers, after 1928,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.722.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Manner of Odilon Redon, Vase of Flowers, after 1928,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.722.4033.

Possibly Exposition rétrospective d’Odilon Redon, exh. cat. (Brussels: Galerie Georges Giroux, 1920), unpaginated, as Vase fleuri.

Ralph T. Coe, “Odilon Redon’s Vase Fleurie,” Bulletin (The Nelson Gallery and Atkins Museum) 5, no. 3 (February 1976): 2, (repro.), as Vase Fleurie.

D[onald] H[offmann], “Another Spencer Gift,” Kansas City Star 96, no. 151 (February 15, 1976): [1]D, (repro.).

“New Day for the Nelson,” Kansas City Star 96, no. 162 (February 26, 1976): 28.

“Principales acquisitions des musées en 1976,” La Chronique des Arts: supplément à la Gazette des Beaux-Arts, no. 1298 (March 1977): S61, (repro.), as Vase fleuri.

Donald Hoffmann, “Certain Surprises and Delights,” Kansas City Star 97, no. 184 (March 20, 1977): 3E.

“Nelson Trust Tops $14 Million,” Kansas City Star 97, no. 296 (July 10, 1977): 8A, (repro.), as Vase Fleurie.

The Kenneth and Helen Spencer Art Reference Library: Given to Complement the Nelson Gallery Collections 1962 (Independence, MO: Graham Graphics, [1978]), unpaginated, as Vase de Fleurs.

Michael Churchman and Scott Erbes, High Ideals and Aspirations: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1933–1993 (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1993), 96, (repro.), as Vase of Flowers.

Roger Ward and Patricia J. Fidler, eds., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collection (New York: Hudson Hills Press, in association with Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1993), 49, 131, 217, (repro.), as Vase of Flowers.

“Blooming Art,” Kansas City Star 117, no. 199 (April 4, 1997): E3, (repro.), as Vase of Flowers.

Alice Thorson, “Shows to show the need for more space,” Kansas City Star 118, no. 305 (July 19, 1998): K3.

Deborah Emont Scott, ed., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collection, 7th ed. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2008), 128, (repro.), as Vase of Flowers.

Kristie C. Wolferman, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A History (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2020), 252, as Vase of Flowers.