![]()

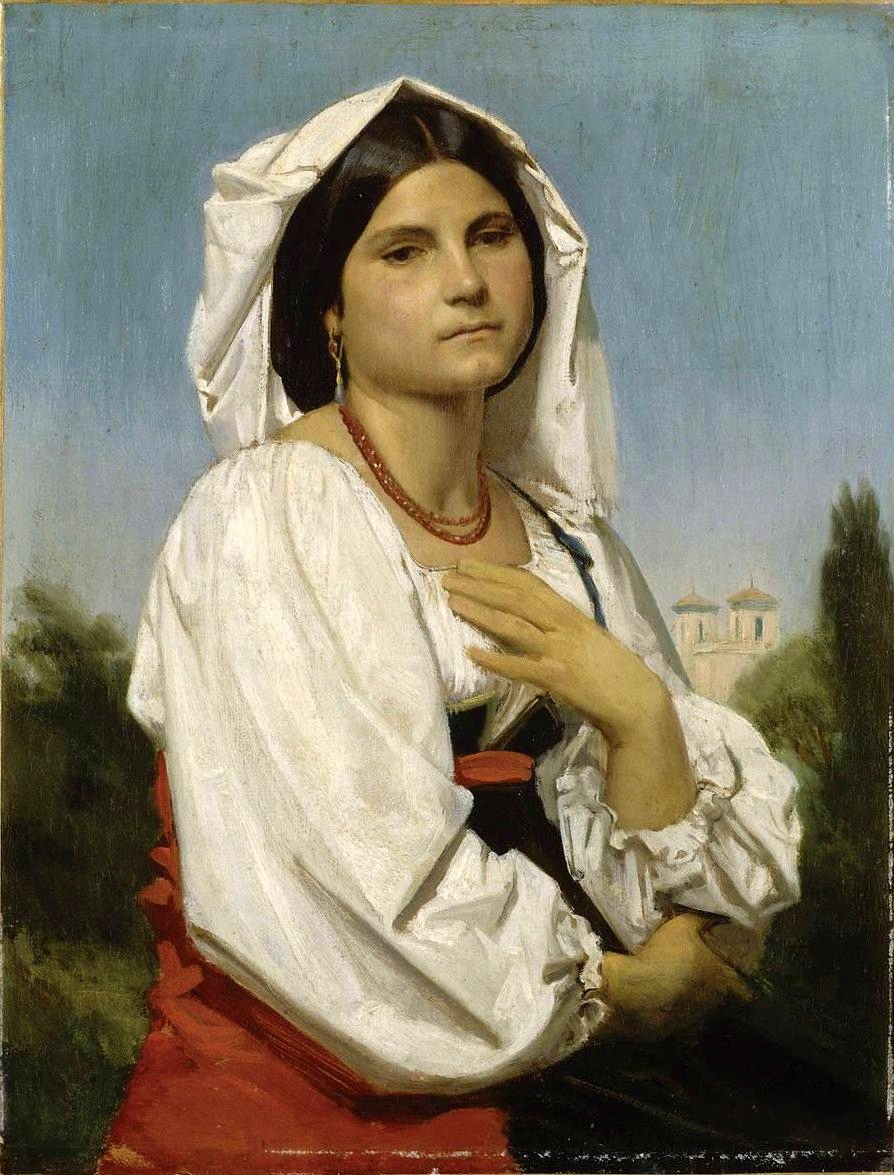

William Adolphe Bouguereau, Italian Woman at the Fountain, 1869

| Artist | William Adolphe Bouguereau, French, 1825–1905 |

| Title | Italian Woman at the Fountain |

| Object Date | 1869 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (Unframed) | 39 3/4 x 31 7/8 in. (101 x 81 cm) |

| Signature | Signed and dated lower left: W. BOVGVEREAV / 1869 |

| Credit Line | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. M. B. Nelson, F88-17 |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Stanton Thomas, “William Adolphe Bouguereau, Italian Woman at the Fountain, 1869,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.502.5407.

MLA:

Thomas, Stanton. “William Adolphe Bouguereau, Italian Woman at the Fountain, 1869,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.502.5407.

With her flawless skin, sensual gaze, and pristine clothing, the title figure of Italian Woman at the Fountain exemplifies the escapist fantasies about contented European peasants that resonated with wealthy collectors throughout the United States, especially when painted by William Adolphe Bouguereau. For the many American collectors of the late 1800s who were flush with recently made fortunes, the artist’s beautiful imagery effectively conveyed the idea of quality and tradition; his works were freshly painted Old Masters for their newly minted American money. Indeed, in the Gilded AgeGilded Age: A period in United States history from about 1870 to 1900 characterized by corrupt politicians and great financial gain through monopolies on industrial production. Although wages of industrial and skilled workers rose, the greatest wealth was collected by the entrepreneurs variously called “captains of industry” or “robber barons.” The new influx of wealth contributed to gross materialism.—from the late 1870s to about 1900—Bouguereau’s works were so popular that “no respectable amateur would mention his new fad of picture-collecting until he had secured a ‘Bouguereau’ for his parlor,”1“W. A. Bouguereau,” The Collector and Art Critic 3, no. 11 (September 1905): 147. as a critic for a New York art journal put it. Many of these paintings that hung in the homes of American robber barons and merchant princes were markedly similar to Italian Woman at the Fountain, with one contemporaneous American critic noting that the artist “is known in this country solely by his paintings, the greater number of which have Italian scenes and Italian figures for their subject.”2“ Bouguereau’s ‘Italian Women at the Fountain,’” Art Journal 1 (1875): 88.

The appeal of Italian Woman at the Fountain is in some ways quite obvious, embodying much of what made Bouguereau so enduringly popular. One cannot fault the model’s extraordinarily luminous skin or the beautifully molded forms of her face, neck, and hands, all effectively contrasted with cloth, metal, foliage, stone, and earth. Her pose is finely balanced: she leans gracefully against the ashlar wall of the fountain enclosure; her intertwined hands are masterfully drawn and painted. Behind her a wall of green gives way to a stony outcropping, which in turns leads the eye upward to the beguiling image of a hill town bathed in evening light. Such paintings seduced both American collectors and critics, with one of many positive reviews praising these “peasant girls Bouguereau paints so charmingly; the arms and hands are marvels of shading and finish.”3Lucy H. Hooper, “ Among the Studios of Paris, “ Art Journal 1 (1875): 62.

Italian Woman at the Fountain belongs to a type of painting that Bouguereau began to produce in the early 1860s and continued to paint into the following decade. They focus on images of beautiful Italian working-class women, with or without children, in tightly focused rustic outdoor settings or domestic or church interiors. Many of these figures, like this one, wear the traditional dress of the Ciociaria region of central Italy: a loosely fitted white blouse; shoulder-tied bodice; strings of heavy beads; a dark, full skirt; and an apron, usually dark green or blue, embroidered with wide bands of red, gold, and green floral motifs.4See, for instance, M. A. Racinet, Le Costume Historique, vol. 6 (Paris: Libairie de Firmin-Didot et Cie, 1888), unpaginated. Such ensembles usually include a voluminous headdress of white cloth; this also may have served as padding to lessen the discomfort of heavy, head-borne loads. It is worth noting that the woman leans on a traditional Italian copper water vessel, or conca, which is usually carried on the head.

Although painted in 1869, Italian Woman at the Fountain directly derives from Bouguereau’s sojourn in Rome nearly twenty years earlier. After applying three times for the prestigious Prix de Rome—granted to the most gifted students of the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture in Paris—the artist finally succeeded to this honor in 1850. Receiving this scholarship gave Bouguereau the chance to travel to Rome, study with French masters at the Villa Medici, and explore the city and surrounding areas. Bouguereau spent three years in Italy and traveled widely, often on foot. He filled his days with studying and copying the masterpieces of art and architecture that abound in Rome and surrounding regions, paying particular attention to the Renaissance masters, among whom Raphael (Italian, 1483–1520) was a favorite. Bouguereau also completed copious sketches and watercolors of local landscapes, hill towns, beggars, and rural workers.

While paintings like Italian Woman at the Fountain, to some extent, resonated with Americans because of their sheer beauty, technical mastery, and visual references to Raphael and other Renaissance masters, the appeal of Bouguereau’s work in the United States is far more complicated and nuanced. Perhaps the most astute look at Bouguereau comes from the famed and sometimes refreshingly acid-tongued American art critic Clarence Chatham Cook. In his popular publication Art and Artists of Our Time, the writer offers some perceptive observations about paintings like Italian Woman at the Fountain:

Bouguereau never forgets that he is painting pictures that are to be bought by rich people for the adornment of their drawing-rooms, and he takes care that nothing in them shall be out of keeping with the tasteful and elegant things that surround them. . . . Bouguereau has provided for his admirers an ample supply of pretty beggar-children, young peasants, mothers of the picturesque poor, and so forth and so on, who are in truth people of the upper class, or seem to be such, with beautiful faces, fine heads of hair, rich eyes, chiseled lips, ivory skins, hands that never wore gloves, feet that never wore shoes, and in a state of immaculate cleanliness.9Clarence Cook, Art and Artists of Our Time (New York: S. Hess, 1888), 1:87–88.

Once again, Bouguereau’s works are revealed as fantasies—images of impossibly beautiful and nymph-like peasants who live an Arcadian existence, far from the constraints of a modern industrialized society. Their informal dress and relatively low décolleté would have contrasted with standards of clothing for the Victorian period in the United States. This would have not only connoted freedom from societal constraints but might also have suggested the possibility of licentious behavior. In addition, there is a slightly fairy-tale quality to Italian Woman at the Fountain, both in the model—whose flawless beauty contrasts with her rustic dress and occupation—and in the castle atop a hill in the distance. Bouguereau also appears to have replaced the simple red or blue beads that were normally part of the Italian peasant costume with a string of massive and lustrous pearls.

In addition to the more fantastical elements of the painting, the costume of Italian Woman at the Fountain lends the picture a slightly exotic air. This is something that viewers of the time would have noticed, and something that may well have contributed to the popularity of such works in the United States. Exoticism, though more commonly associated with the European and American fascination with Asia or the Near East, is the attraction felt by artists or viewers for any culture different from their own. Bouguereau’s work often includes appealing “foreign” elements, as here. One of the connotations of exoticism is that because it is different and “other,” it represents a way of departing from the everyday. This framework reinforces the idea of Italian Woman at the Fountain as an elegant but clearly escapist fantasy.

Although the painting’s history of ownership extends back to its purchase, from Bouguereau, by the Paris firm Goupil and Company in 1869, there is a frustrating gap in ownership from 1870 to 1932. The painting was probably one of the many “smooth, attitudinizing canvases, which found greedy takers, especially in France and the United States,” in the words of an American critic—pictures that often appealed to the more conservative tastes of America’s nouveau riche merchants and captains of industry.10“W. A. Bouguereau,” 147. Indeed, by 1932 it was in the possession of Mack Barnabus Nelson (1872–1950) and his wife, May (née Milhon, 1874–1951), of Kansas City. Like many of Bouguereau’s collectors, Mack was a self-made man. At the age of fifteen he left his native Arkansas for Mexico, and he eventually rose to become the president of the Long-Bell Lumber Company. In 1914, he and May constructed a mansion on Ward Parkway that befitted their wealth and social standing. Bouguereau’s Italian Woman at the Fountain hung in the home’s two-story interior courtyard (Fig. 3). The Italian subject matter coordinated perfectly with the open space surrounded by columns, an adaptation of an ancient Roman peristyle. The painting also beautifully complemented the courtyard’s furniture, which was inspired by classical models.

Notes

-

“W. A. Bouguereau,” The Collector and Art Critic 3, no. 11 (September 1905): 147.

-

“Bouguereau’s ‘Italian Women at the Fountain,’” Art Journal 1 (1875): 88.

-

Lucy H. Hooper, “Among the Studios of Paris,” Art Journal 1 (1875): 62.

-

See, for instance, M. A. Racinet, Le Costume Historique, vol. 6 (Paris: Libairie de Firmin-Didot et Cie, 1888), unpaginated.

-

John C. Van Dyke, “Style and Individuality,” Decorator and Furnisher 12, no. 4 (July 1888): 131.

-

Bouguereau also shared an ongoing visual dialogue with Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796–1875), who produced a series of Italian female figures in the 1860s and early 1870s. Many of them wear similar clothing, are posed in similar settings, and have similar props as the woman in the Nelson-Atkins painting. Some examples include: Agostina (1866; National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.46583.html), Gypsy Girl at a Fountain (1865–1870; Philadelphia Museum of Art, https://philamuseum.org/collection/object/102994), and Italian Woman at the Fountain (1865–1870; Kunstmuseum Basel, Inv. G 1963.28 (http://sammlungonline.kunstmuseumbasel.ch/ eMuseumPlus?service=ExternalInterface &module=collection&objectId=1465&viewType =detailView). I am grateful for Brigid M. Boyle, Bloch Family Foundation Doctoral Fellow, for sharing this insight.

-

“En prenant Raphaël pour point de départ, M. Bouguereau a montré que le sentiment moderne pouvait s’accommoder d’une forme ancienne.” Clément de Ris, quoted in Catalogue illustré des œuvres de W. Bouguereau (Paris: Librarie d’art, 1885), 15; translation by the author.

-

“A Modern Holy Family,” The Aldine: The Art Journal of America 8, no. 4 (April 1876): 124.

-

Clarence Cook, Art and Artists of Our Time (New York: S. Hess, 1888), 1:87–88.

-

“W. A. Bouguereau,” 147.

-

“See, for example, Louise d’Argencourt and Mark Steven Walker, William Bouguereau, 1825–1905, exh. cat. (Montreal: Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, 1984); and Tanya Paul and Stanton Thomas, Bouguereau and America, exh. cat. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019).”

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Mary Schafer, “William Adolphe Bouguereau, Italian Woman at the Fountain, 1869,” technical entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.502.2088.

MLA:

Schafer, Mary. “William Adolphe Bouguereau, Italian Woman at the Fountain, 1869,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.502.2088.

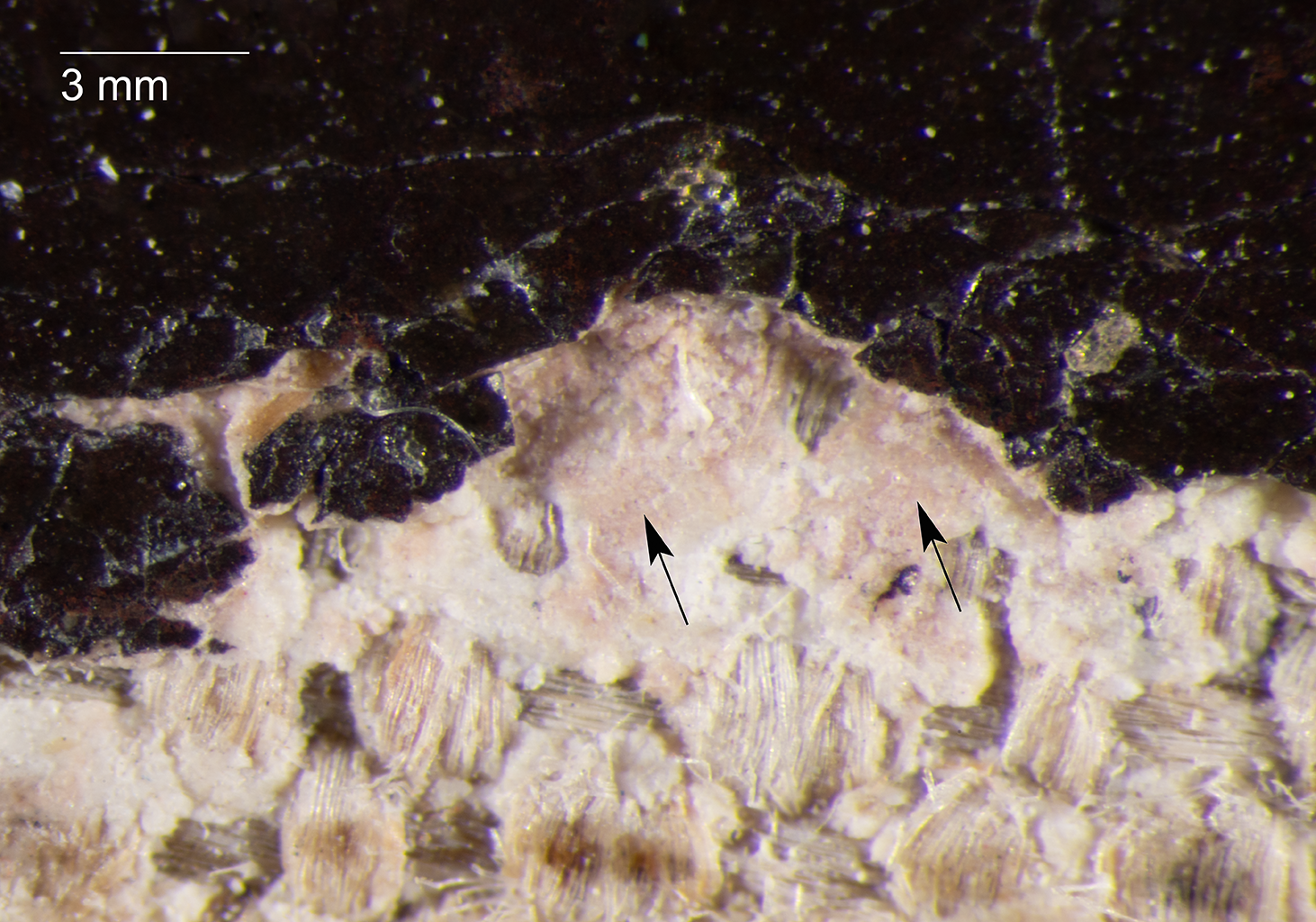

Italian Woman at the Fountain appears to have been executed on a plain-weaveplain weave: A basic textile weave in which one weft thread alternates over and under the warp threads. Often this structure consists of one thread in each direction, but threads can be doubled (basket weave) or tripled to create more complex plain weave. Plain weave is sometimes called tabby weave. canvas with an initial, bright white ground layerground layer: An opaque preparatory layer applied to the support, either commercially or by the artist, to prevent absorption of the paint into the canvas or panel. See also priming layer. followed by an upper ground of pale pink (Fig. 4). The tacking marginstacking margins: The outer edges of canvas that wrap around and are attached to the stretcher or strainer with tacks or staples. See also tacking edge. have been removed, making it difficult to determine whether the ground was commercially prepared, artist-applied, or a combination of the two.1The ground layers beneath Seated Nude (1884; Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, MA) consist of a lower commercially applied gray layer that continues onto the preserved tacking margins, over which an upper pale pink ground was applied by the artist. See technical report by Sandra Webber in Nineteenth-Century European Paintings at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, ed. Sarah Lees (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012), 84. Equidistant stretcher cracksstretcher cracks: Linear cracks or deformations in the painting’s surface that correspond to the inner edges of the underlying stretcher or strainer members. and areas where paint stops short of the outer edges suggest that the dimensions of the painting (101 x 81 cm), which are close in size to standard-formatstandard-format supports: Commercially prepared supports available through art suppliers, which gained popularity in the nineteenth century during the industrialization of art materials. Available in three formats figure (portrait), paysage (landscape), and marine (marine), these were numbered 1 through 120 to indicate their size. For each numbered size, marine and paysage had two options available: a larger format (haute) and smaller (basse) format. no. 40 figure stretcherstretcher: A wooden structure to which the painting’s canvas is attached. Unlike strainers, stretchers can be expanded slightly at the joints to improve canvas tension and avoid sagging due to humidity changes or aging. (100 x 81 cm),2David Bomford, Jo Kirby, John Leighton, and Ashok Roy, Art in the Making: Impressionism (London: Yale University Press, 1991), 46. have not been substantially altered.

Fig. 6. Detail of the forehead, Italian Woman at the Fountain (1869), showing the gradual transitions from light to shadow

Fig. 6. Detail of the forehead, Italian Woman at the Fountain (1869), showing the gradual transitions from light to shadow

Fig. 7. Photomicrograph of the proper right eyelid, Italian Woman at the Fountain (1869)

Fig. 7. Photomicrograph of the proper right eyelid, Italian Woman at the Fountain (1869)

Fig. 8. Detail of the pearl necklace, Italian Woman at the Fountain (1869)

Fig. 8. Detail of the pearl necklace, Italian Woman at the Fountain (1869)

Fig. 9. Ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescence photograph, Italian Woman at the Fountain (1869)

Fig. 9. Ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescence photograph, Italian Woman at the Fountain (1869)

Notes

-

The ground layers beneath Seated Nude (1884; Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, MA) consist of a lower commercially applied gray layer that continues onto the preserved tacking margins, over which an upper pale pink ground was applied by the artist. See technical report by Sandra Webber in Nineteenth-Century European Paintings at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, ed. Sarah Lees (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012), 84.

-

David Bomford, Jo Kirby, John Leighton, and Ashok Roy, Art in the Making: Impressionism (London: Yale University Press, 1991), 46.

-

For an overview of Bouguereau’s preparatory process, see Mark Steven Walker, “Bouguereau at Work,” in William Bouguereau 1825–1905, ed. Mortimer Schiff, exh. cat. (Montreal: Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, 1984), 71-74. See also Damien Bartoli and Frederick Ross, William Bouguereau: His Life and Works (Antique Collectors Club: Art Renewal Center and the William Bouguereau Committee, 2010), 468-74.

-

Émile Bayard, “William Bouguereau,” Le Monde Moderne (Paris: A. Quantin, 1897), 854, cited and translated in Bartolio and Ross, William Bouguereau, 469.

-

See technical entries for Nymphs and Satyr (1873) and Seated Nude (1884) by Sandra Webber in Nineteenth-Century European Paintings, 81, 84.

-

“The exact method that Bouguereau used for transferring the cartoons to canvas is also not known. There are no pounce marks or grids to be found on them, but in view of the fact that their main contours [of the cartoon] are usually heavily reinforced with graphite, it is likely that a pressure technique was involved. In other instances there is no graphite along the contours but rather a groove indicating the passage of a stylus.” Walker, “Bouguereau at Work,” 74.

-

François Flameng, “Notice sur la vie et les travaux de M. Bouguereau, lue dans la séance du 24 février 1906, Institut de France, Académie des Beaux-Arts” (Paris: Firmin-Didot, 1906), cited and translated in Walker, “Bouguereau at Work,” 75.

-

Helmut Schweppe and John Winter, “Madder and Alizarin,” in Artists’ Pigments: A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics, ed. Elisabeth West FitzHugh (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1997) 3:124.

-

“Laque de garance foncée” is listed in the description of Bouguereau’s palette in Charles Moreau-Vauthier, Comment on peint aujourd’hui (Paris: Henri Floury, 1923), 24. Additionally, a number of lake pigments are listed in Bouguereau’s 1869 sketchbook. William Bouguereau, sketchbook no. 5, 1869, Bouguereau Family Estate, cited in Walker, “Bouguereau at Work,” 77.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “William Adolphe Bouguereau, Italian Woman at the Fountain, 1869,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.502.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “William Adolphe Bouguereau, Italian Woman at the Fountain, 1869,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.502.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “William Adolphe Bouguereau, Italian Woman at the Fountain, 1869,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.502.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “William Adolphe Bouguereau, Italian Woman at the Fountain, 1869,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.502.4033.

Purchased from the artist by Goupil et Cie, Paris, stock book no. 4, stock no. 4695, as Italienne à la fontaine, December 31, 1869–June 12, 1870;

Purchased from Goupil et Cie by Henry Wallis (1805–1890), London, June 12, 1870 [1];

Mr. Mack Barnabus “M. B.” (1872–1950) and Mrs. Cora “May” (née Milhon, 1874–1951) Nelson, Kansas City, MO, by 1932–June 10, 1950 [2];

Inherited by his wife, May Nelson, Kansas City, MO, June 29, 1950–May 23, 1951 [3];

Estate of M. B. and May Nelson, 1951–1956 [4];

Bequeathed by M. B. and May Nelson to The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, June 14, 1956 [5];

Notes

[1] Henry Wallis was the owner of the French Gallery in London. Per Pamela Fletcher, at that time, it was normal for dealers to own the works they exhibited. See correspondence from Fletcher to Meghan Gray, The Nelson-Atkins, July 27, 2010, The Nelson-Atkins curatorial files. The gallery continued after Wallis’s death under the direction of his descendants until 1929.

[2] See autochrome photograph of the painting hanging in the Nelsons’ interior patio, dated August 23, 1932, Frank Lauder Autochrome collection (P22), Missouri Valley Special Collections, Kansas City Public Library. Mr. Nelson visited England, Ireland, and Scotland in 1889, and, in 1911 he and his wife visited Southampton, England. These were opportunities where they may have purchased the painting.

[3] M. B. Nelson died on June 10, 1950. Nelson’s will was filed in the Jackson County Probate court on June 29, 1950. The will indicates that the home on 5500 Ward Parkway, Kansas City, MO, was held jointly by his widow, May Nelson. The entire estate was left to Mrs. Nelson, who was named jointly with the Commerce Trust company as executor of the estate. The will was dated March 9, 1950. See “M. B. Nelson Will Filled,” Kansas City Star 70, no. 285 (June 29, 1950): 3.

[4] The painting remained in the Nelsons’ house at 5500 Ward Parkway, which was inherited by Mrs. Nelson’s sisters, Katherine “June” Carlberg (née Milhon, 1876–1964) and Vida Clara Frick (née Milhon, 1890–1978). In 1956, Carlberg and Frick sold the mansion and brought the painting to the Nelson-Atkins. It was accepted into the museum’s reserve collection as a gift by bequest on June 14, 1956, but on January 4, 1957, the museum loaned Frick the painting, which she hung in her apartment at 5050 Oak Street, Kansas City, MO. See The Nelson-Atkins registration files; and Erma Young, “Family Treasures as Key to Décor,” Kansas City Star 80, no. 192 (March 27, 1960): 6H.

[5] On October 17, 1974, the Nelson’s nephew, William M. Frick (1914–2000), Kansas City, MO, returned the painting to the museum. The museum offered the painting for sale in 1985 at Nineteenth Century European Paintings, Drawings, and Watercolors, Christie’s, New York, October 30, 1985, lot 88, but it failed to sell. The painting was accessioned into the permanent collection on June 20, 1988. See The Nelson-Atkins curatorial files.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “William Adolphe Bouguereau, Italian Woman at the Fountain, 1869,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.502.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “William Adolphe Bouguereau, Italian Woman at the Fountain, 1869,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.502.4033.

William Adolphe Bouguereau, Portrait of Teresa, 1854, oil on canvas, 15 3/4 x 12 5/8 in. (40 x 32 cm), Musée des Beaux-Arts de Valenciennes, France.

William Adolphe Bouguereau, Harvester, 1868, oil on canvas, 41 7/8 x 33 1/2 in. (106.5 x 85 cm), private collection, illustrated in Damien Bartoli and Frederick Ross, William Bouguereau: Catalogue Raisonné of his Painted Works (Port Reading, NJ: Antique Collector’s Club and Art Renewal Center, 2010), no. 1868/07, p. 2:170.

William Adolphe Bouguereau, Italian Girl Drawing Water, 1871, oil on canvas, 47 x 31 1/8 in. (119.4 x 78.7 cm), private collection, illustrated in Damien Bartoli and Frederick Ross, William Bouguereau: Catalogue Raisonné of his Painted Works (Port Reading, NJ: Antique Collector’s Club and Art Renewal Center, 2010), no. 1871/13, p. 2:137.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “William Adolphe Bouguereau, Italian Woman at the Fountain, 1869,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.502.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “William Adolphe Bouguereau, Italian Woman at the Fountain, 1869,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.502.4033.

Possibly Seventeenth Annual Exhibition in London of Pictures: The Contributions of French and Flemish Schools at the Gallery, French Gallery, London, 1870, no. 96, as A Day-dream at the Well.

Winslow Homer and the Critics: Forging a National Art in the 1870s, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, February 18–May 6, 2001; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, June 10–September 9, 2001; High Museum of Art, Atlanta, October 6, 2001–January 6, 2002 (Kansas City only), hors cat.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “William Adolphe Bouguereau, Italian Woman at the Fountain, 1869,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.502.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “William Adolphe Bouguereau, Italian Woman at the Fountain, 1869,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.502.4033.

Possibly Seventeenth Annual Exhibition in London of Pictures: The Contributions of French and Flemish Schools at the Gallery, exh. cat. (London: French Gallery, 1870).

Possibly “The French Gallery: Seventeenth Exhibition,” Art-Journal 32 (London) (May 1, 1870): 149, as A Day-dream at the Well.

Ch. Vendryès, Catalogue illustré des œuvres de W. Bouguereau, ed. L. Baschet (Paris: Librairie d’Art, 1885), 45, as l’Italienne à la Fontaine.

Comte de Franqueville [Amable Charles Franquet],Le premier siècle de l’Institut de France, 25 oct. 1795–25 oct. 1895 (Paris: J. Rothschild, 1895), 1:370, as l’Italienne à la fontaine.

Marius Vachon, W. Bouguereau (Paris: A. Lahure, 1900), 149, as Italienne A [sic] La Fontaine.

Erma Young, “Family Treasures as Key to Décor,” Kansas City Star 80, no. 192 (March 27, 1960): 6H, (repro.).

Nineteenth-Century European Paintings, Drawings, and Watercolors (New York: Christie’s, October 30, 1985), unpaginated, (repro.), as Italienne À La Fontaine.

“New at the Nelson,” Calendar of Events (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (January 1989): 2, (repro.), as Standing Woman (L’Italienne à la fontaine).

Robert Rosenblum et al., William-Adolphe Bouguereau: L’Art Pompier, exh. cat. (New York: Borghi, 1991), 68, as Italienne à la fontaine.

Roger B. Ward and Patricia J. Fidler, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collection, 1st ed. (New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1993), 205, (repro.), as Standing Woman (also called Italian Woman at a Fountain).

“Educational Insights,” Calendar of Events (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (September 2001): 4, (repro.), as Standing Woman.

Deborah Emont Scott, ed., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collection, 7th ed. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2008), 116, (repro.), as Italian Woman at the Fountain.

Damien Bartoli and Fred Ross, “Biography of William Bouguereau,” Art Renewal Center (January 1, 2002): https://www.artrenewal.org/Article/Title/biography-of-william-bouguereau#12, as L’Italienne à la fontaine.

Damien Bartoli and Fred Ross, William Bouguereau: His Life and Works; Catalogue Raisonné of his Painted Works (Port Reading, NJ: Antique Collector’s Club in cooperation with the Art Renewal Center, 2010), no. 1869/18, pp. 1:188, 2:122, (repro.), as L’Italienne á la fontaine (The Italian girl at the fountain).

Didier Jung, William Bouguereau: le peintre roi de la Belle Époque (Saintes: Le Croît Vif, 2014), 346, as Italiennes [sic] á la fontaine.

Catherine Futter et al., Bloch Galleries: Highlights from the Collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2016), 53, (repro.), as Italian Woman at the Fountain.

Tanya Paul and Stanton Thomas, Bouguereau and America, exh. cat. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019), 42, The Italian Woman at the Fountain.

Fausto Boga, “La Transformazione della Realtà in Bellezza,” Hestetika Magazine 37 (February 2021): 33, (repro.), as Italian Woman at the Fountain.