![]()

Edouard Manet, The Croquet Party, 1871

| Artist | Edouard Manet, French, 1832–1883 |

| Title | The Croquet Party |

| Object Date | 1871 |

| Alternate and Variant Titles | The Croquet Party at Boulogne-sur-Mer; La partie de croquet |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (Unframed) | 18 x 28 3/4 in. (45.7 x 73 cm) |

| Signature | Signed lower right: Manet |

| Credit Line | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Gift of Marion and Henry Bloch, 2015.13.11 |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Simon Kelly, “Edouard Manet, The Croquet Party, 1871,” catalogue entry in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.522.5407

MLA:

Kelly, Simon. “Edouard Manet, The Croquet Party, 1871,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.522.5407.

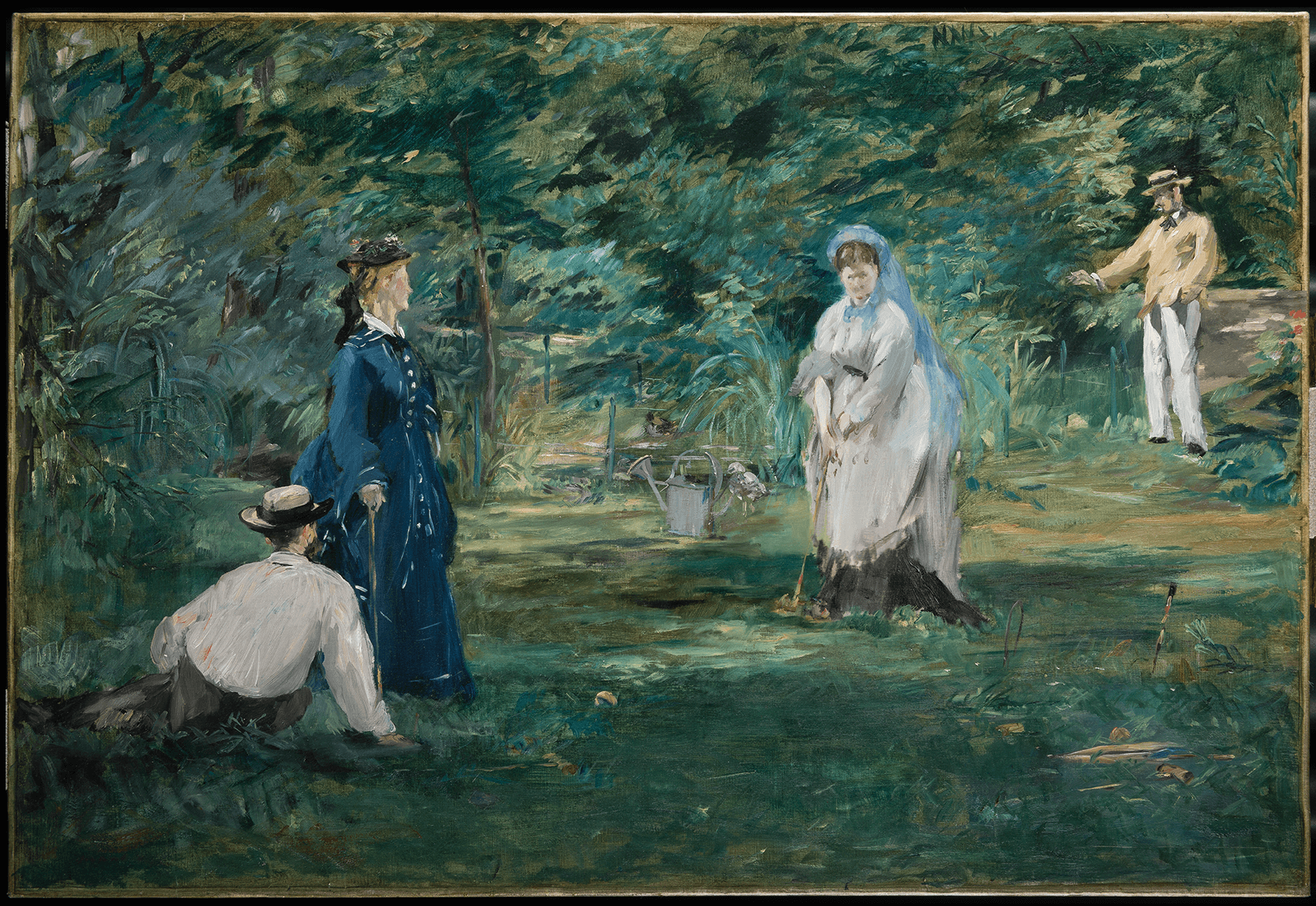

The Croquet Party shows Manet’s fascination with the seaside resort of Boulogne, which he visited repeatedly and painted on at least forty occasions.6For the most detailed study of Manet’s time at Boulogne, see Juliet Wilson-Bareau and David Degener, "Manet and the Sea," in Manet and the Sea, exh. cat. (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2003), 55–101. About half of Manet’s total number of marines were painted at Boulogne. The town had expanded greatly as a resort since 1848, when a railroad line connected it to Paris. It became even more of an attraction following the opening of its casino and beach house in 1863, and these locations soon became the center of tourist life for the city. Five members of Manet’s family, including the artist himself, took a one-month subscription to the beach house on July 16, 1864. In the summer of 1868, Manet spent about two months in Boulogne with his wife and stepson.

On the advice of his doctor, Manet probably returned to Boulogne in the summer of 1871 to treat his nervous exhaustion following the siege of Paris by the Prussians during the Franco-Prussian WarFranco-Prussian War: The war of 1870–1871 between France (under Napoleon III) and Prussia, in which Prussian troops advanced into France and decisively defeated the French at Sedan. The defeat marked the end of the French Second Empire. For Prussia, the proclamation of the new German Empire at Versailles was the climax of Bismarck’s ambitions to unite Germany., and the subsequent bloody episode of the Paris Commune, when up to twenty thousand Parisians were killed.7Une correspondance inédite d’Édouard Manet: Les lettres du siège de Paris, 1870–1871, ed. Adolphe Tabarant (Paris: Mercure de France, 1935), 35. The Croquet Party has generally been dated to 1871, a dating that is followed here.8That Jeanne Gonzalès is in the painting supports this date, since Manet was only introduced to the Gonzalès sisters in 1869. Adolphe Tabarant initially dated the picture to 1873, based on an inscription on a photograph by Fernand Lochard of the related The Croquet Party at the Stadel Museum, Frankfurt (see Fernand Lochard, three albums of photographs of the work of Edouard Manet, ca. 1883, Morgan Library and Museum, New York, MA 3950, vol. 2, cat. no. 69). Tabarant subsequently amended his dating to 1871: "…cette peinture de plein air qui est la Partie de crocket. Théodore Duret la place en 1873, et nous l’y avions placée après lui, sur la loi d’une mention que porte une photo Lochard. Rectifions" la Partie de Crocket est de 1871." A[dolphe] Tabarant, Manet et ses Œuvres, 5th ed. (Paris: Gallimard, 1947), 191. Also dating the painting to 1871 is Étienne Moreau-Nélaton, Manet Raconté par Lui-Même (Paris: Henri Laurens, 1926), 1:153. See also Théodore Duret, Histoire d’Édouard Manet et de Son Œuvre, Avec un Catalogue des Peintures et des Pastels, new ed. (Paris: Bernheim-Jeune, 1919), 137, no. 169. The Rouart and Wildenstein catalogue raisonné also follows this dating; see Denis Rouart and Daniel Wildenstein, Edouard Manet" Catalogue raisonné (Lausanne: Bibliothèque des arts, 1975), 1:154, no. 173. There are two photographs by Manet’s photographer colleagues, Godet et Cie, of the Nelson-Atkins The Croquet Party (photographs of the work of Edouard Manet, undated [portions ca. 1872–74 and 1884], Morgan Library and Museum, New York, MA 3950, vol. 1, no. 21, and MA 3950, vol. 2, no. 16. The latter has an inscription dating the picture to 1871. Editions of both the Godet and Lochard photography albums owned by the Morgan Library and Museum bear different handwritten inscriptions than the albums owned by the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris. The editor would like to thank María Isabel Molestina, The Morgan Library and Museum, New York, for her assistance in researching these volumes.). Wilson-Bareau and Degener have suggested an alternate date of ca. 1872, arguing that the artist may have made an undocumented trip that summer. Wilson-Bareau and Degener, Manet and the Sea, 73, 135. In a provocative reading, Joachim Pissarro sees the picture in relation to the trauma of the recent events experienced by Manet in Paris in 1870–71.9Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 30–33. He argues that the work reflects the artist’s continuing disorientation and retains elements of alienation and detachment, even comparing the isolation of the figures to a play by Samuel Beckett. As is generally the case with Manet, however, readings are never clear, and the bright colors of the scene, notably Jeanne’s dress, and quaint details, such as the scrapping dogs, argue for a less dark reading.

In depicting the game of croquet, Manet was showing a sport that was newly imported

to France from England in the mid-nineteenth century. Equally suited to men and

women, croquet rapidly became popular among the upper classes. The 1874 edition of

Merridew’s Guide to Boulogne-sur-Mer and its Environs noted: “On the terrace next

to the sea will be found spacious lawns, on which the game of croquet is played.“10Merridew’s Visitor’s Guide to Boulogne-sur-Mer and its Environs; With Some Account of Its Early History, and a Notice of the Objects Most Worthy of Visiting in the City and District (London: Simpkin, Marshall, 1874), 71.

Juliet Wilson-Bareau and David Degener have described The Croquet Party as “a

brilliant comedy of manners.”11Wilson-Bareau and Degener, Manet and the Sea, 73, 135. Croquet was

recognized as a space for flirtation between the sexes, and it is possible that

Manet intended to suggest a sexual attraction or tension between Léon and Jeanne,

both nineteen-year-old young adults. Jeanne, as the many portraits of her by her

sister reveal, was an attractive young woman. Léon, for his part, takes on an air

of detachment, as is often the case in Manet’s images of him. Could he be playing

hard to get?

Manet shows a game of doubles in process, or alternatively two separate games of

singles. The four protagonists hold mallets, ready to strike red and yellow balls

toward the croquet peg, marked in blue, red, yellow, green and black. Not

represented, and presumably obscured, are the game’s hoops.12There is a preliminary sketchbook drawing which shows a large group of hoops alongside a peg (Cabinet des dessins, Fonds des dessins et miniatures, Musée du Louvre, Paris Croquis [RF 30494, verso]).

Manet’s picture can be situated within the context of his interest in representing

contemporary leisure, and specifically sporting activities. He painted a related

croquet scene of around 1873 (Fig. 2), depicting the very different setting of the

garden of his friend, the Belgian painter, Alfred Stevens (1823–1906).13Leenhoff noted that Manet’s idea for this picture came from croquet games played in the beach club garden at Boulogne-sur-Mer. See Léon Leenhoff, "Registre manuscrit: Œuvres d’Edouard Manet (peintures, pastels, dessins, et estampes) recensées dans son atelier en 1883 ou chez leur propriétaire," 1883, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, Département des Estampes et photographie, 8-Yb34649 Res, folio 16. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b105469429.

He also produced views of boating and skating. As a group, these form an important c

hronicle of modern sporting life.

Manet shows his interest in contemporary fashion in The Croquet Party. Fashion

magazines at the time recommended specific types of dress and headwear for visits

to the beach. The youthful Gonzalès wears a dress, in bright blue and yellow, with

a short skirt that leaves her ankle boots visible and that first came into fashion

around 1867.14See correspondence from Justine de Young to Simon Kelly, January 21, 2020. A print from this time shows a young

woman wearing a very similar dress (Fig. 3).15Thanks to Justine de Young for providing the author with this image. The

exotic blue bird ornamenting Gonzalès’ toque, perhaps an African starling,

coloristically complements her auburn hair.16In a pastel portrait of Jeanne by Eva Gonzales from 1869–70 (private collection), she appears with darker hair, in line with her Spanish ancestry. Manet may have therefore taken some license with her hair shade. Suzanne

and her partner are dressed in more muted colors and wear small crinoline cages,

rather than bustles, also reflecting the continuing influence of late 1860s

fashions.17Justine de Young to Simon Kelly, January 21, 2020. Paul Roudier wears a dark suit and bowler

hat, and Léon Leenhoff a checkered, tightly fitted gray jacket, brown pants, and

a black fedora, animated by a brown feather.

The Croquet Party is among Manet’s most rapidly worked paintings and relates

closely to the painterly practice of the Impressionists. Although the artist never

exhibited with this group, this picture shows his closeness to their work in its

rapidly gestural technique and evocation of atmosphere. The picture has been

compared to Garden at Saint-Adresse by Claude Monet (1840–1926) for its similar

frontal view of a windy beachside with blowing flags; Manet is known to have

admired that picture on a visit to the studio of Frédéric Bazille (1841–1870)

around 1867. Despite its air of spontaneity and sense of the “captured moment,”

The Croquet Party was based on at least ten watercolor and pencil studies, also

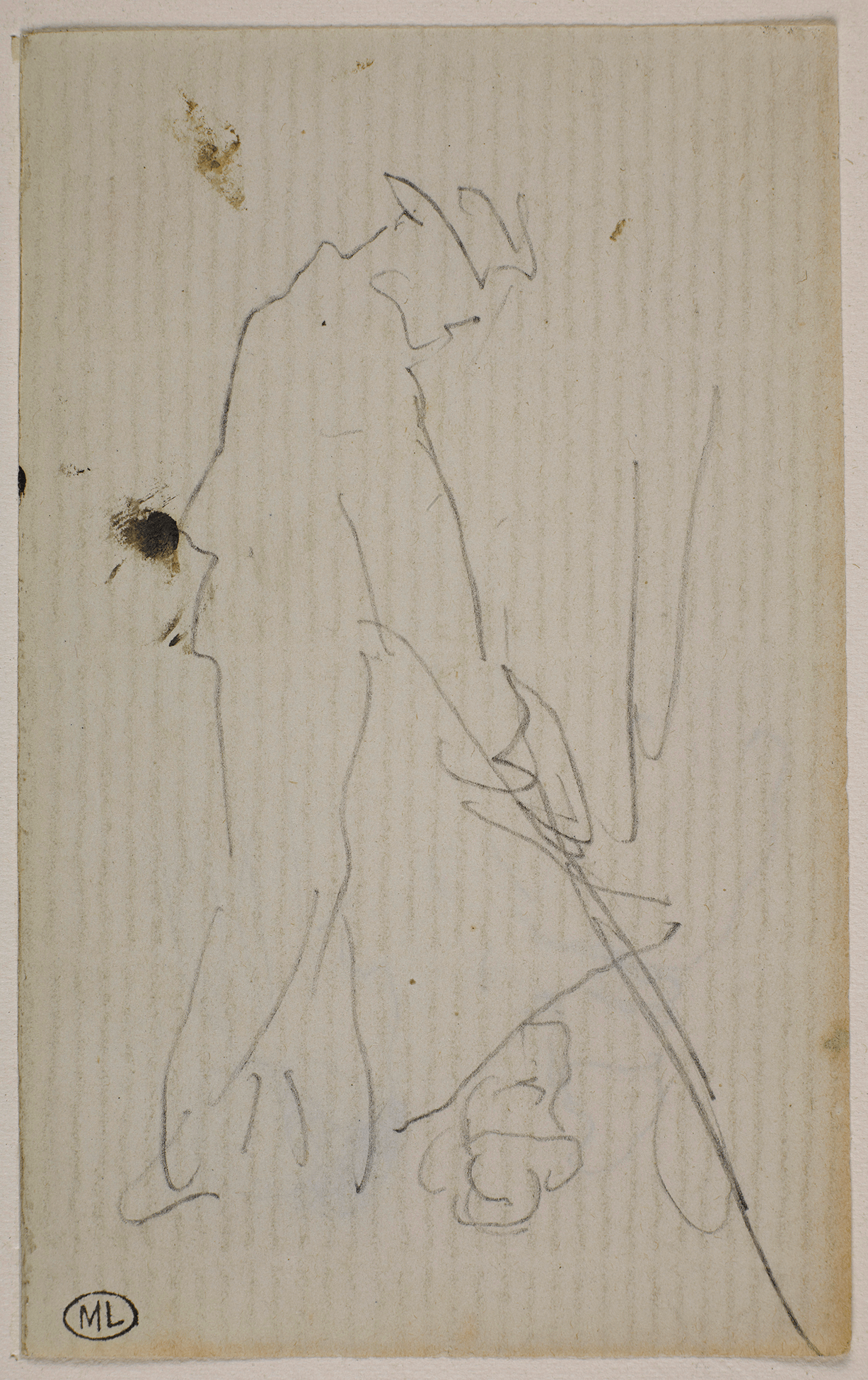

probably made in 1871.18Juliet Wilson-Bareau argues that the sketches were not made in 1868 at the same time as the Boulogne 1868 (Whatman) sketchbook (Musée d’Orsay, Paris, RF 11169), which also "includes many blank pages, so it seems unlikely that the small Folkestone Boat and Croquet sketches were made at the same time." She has suggested a date for these sketches of ca. 1872. See Wilson-Bareau and Degener, Manet and the Sea, 71–72. The sketchbook dates from Manet’s lengthy vacation in Boulogne in 1868 and is composed of paper watermarked "J WHATMAN." See Juliet Wilson-Bareau and David Degener, Manet and the American Civil War: The Battle of USS Kearsarge and CSS Alabama, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2003), 69, 72n15. It was thus probably

composed in the studio rather than being painted en plein airen plein air (adjective: plein-air): French for “outdoors.” The term is used to describe the act of painting quickly outside rather than in a studio..19See the following preparatory drawings for two croquet paintings by Manet from the Cabinet des dessins, Fonds des dessins et miniatures, Musée du Louvre, Paris: Femme debout, coiffée d’un chapeau, tenant un maillet de croquet, ca. 1871, pencil on laid paper (RF 30410); Femme debout, de dos, ca. 1871, pencil on laid paper (RF 30412); Homme, debout, un maillet à la main, pencil on laid paper (RF 30476); and Femme debout, tenant un maillet, pencil and watercolor on laid paper (RF 30538).

Manet’s practice of conflating plein-air pencil studies into a studio picture is

also evident in On the Beach at Boulogne-sur-Mer (1868; Virginia Museum of Fine

Arts, Richmond). The drawings for The Croquet Party include a rapid sketch of

Jeanne Gonzalès holding a croquet mallet behind her back, which underpins her

final pose in the painting (Fig. 4), and a pencil sketch of Léon Leenhoff

preparing to hit the croquet ball (Fig. 5). Other sketches, as in the rapidly

worked watercolor study Two Croquet Players (Musée du Louvre, Paris, RF 30549),

are more loosely connected to the picture.

The Croquet Party was acquired by the painter Gustave Caillebotte (1848–1894) directly from Manet in 1879 for the comparatively low sum of 600 francs.20See Anne Distel, "Essai de récapitulation de la collection de Gustave Caillebotte," in Anne Distel et al., Gustave Caillebotte: 1848–1894, exh. cat. (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 1994), 42–43. In 1894, Caillebotte offered it as part of his bequest to the French state. The two other Manets in his bequest (Angelina and The Balcony) were accepted, but this work was refused for unclear reasons. Today, it can be considered one of Manet’s most intriguing paintings. The artist’s vibrant, abstracted brushwork is clearly part of the picture’s modernity. So, too, is Manet’s depiction of a newly fashionable sporting activity. The painting provides a glimpse into his private inner circle, showing his wife and stepson, his longtime male friend, and a favored female artist friend, all enjoying a moment of escape and respite after a recent period of unimaginable horror.

Notes

-

“ . . . dans le cercle des amis de Manet, au premier rang desquels était Paul Roudier qui l’accompagnait partout, aux jeudis de son père et de sa mère et aux vendredis du café Guerbois . . . ” Antonin Proust, Edouard Manet: Souvenirs (Paris: Librairie Renouard et H. Laurens, 1913), 37. Manet had previously used Roudier as a model for the legs in his 1866 full-length portrait The Tragic Actor (Rouvière as Hamlet), depicting the actor Philibert Rouvière (National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC).

-

Jeanne Gonzalès showed at the Paris Salon from 1878 until 1889, producing impressive pictures such as Portrait of Eva at Dieppe (private collection), a portrait of her sister. She was often represented by her sister. See Eva Gonzalès, Jeanne Gonzales in Profile (Portrait de femme), 1865–70, oil on canvas, 6 5/16 x 5 1/2 in. (16 x 14 cm), Musée des Beaux-Arts, Marseille, inv. 797. Both were daughters of novelist Emmanuel Gonzalès. See “Jeanne Guérard-Gonzalès,” in Marie-Catherine Sainsaulieu and Jacques de Mons, Eva Gonzalès, 1849–1883: Étude critique et catalogue raisonné (Paris: La Bibliothèque des Arts, 1990), 32–42. See also Russell T. Clement, “Jeanne Gonzalès” in Dictionary of Artists’ Models, ed. Jill Berk Jimenez (2001; repr. New York: Routledge, 2013), 241–42. In 1872, for example, the two sisters exhibited a pastel that they signed jointly as Jeanne-Eva Gonzalès. See also Janalee Emmer, “Rethinking Self: Eva Gonzalès on Her Own,” paper presented at the Hawaii International Conferences on Arts and Humanities, Honolulu, HI, January 9, 2012, http://www.huichawaii.org/assets/emmer,-janalee—rethinking-self–eva-gonzales-%281849-1883%29-on-her-own.pdf.

-

See Carol Jane Grant, Eva Gonzalès: An Examination of the Artist’s Style and Subject Matter (PhD diss., Ohio State University, 1994), 78.

-

For Manet’s relationship with Léon, see Nancy Locke, Manet and the Family Romance (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001). See also “Léon Koella-Leenhoff in Dictionary of Artists’ Models, 302–5.

-

We might conjecture that the faceless woman could be Eva Gonzalès or perhaps the mother of the Gonzalès sisters, since the Gonzalès family generally holidayed together.

-

For the most detailed study of Manet’s time at Boulogne, see Juliet Wilson-Bareau and David Degener, “Manet and the Sea,” in Manet and the Sea, exh. cat. (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2003), 55–101.

-

Une correspondance inédite d’Édouard Manet: Les lettres du siège de Paris, 1870–1871, ed. Adolphe Tabarant (Paris: Mercure de France, 1935), 35.

-

That Jeanne Gonzalès is in the painting supports this date, since Manet was only introduced to the Gonzalès sisters in 1869. Adolphe Tabarant initially dated the picture to 1873, based on an inscription on a photograph by Fernand Lochard of the related The Croquet Party at the Stadel Museum, Frankfurt (see Fernand Lochard, three albums of photographs of the work of Edouard Manet, ca. 1883, Morgan Library and Museum, New York, MA 3950, vol. 2, cat. no. 69). Tabarant subsequently amended his dating to 1871: “ . . . cette peinture de plein air qui est la Partie de crocket. Théodore Duret la place en 1873, et nous l’y avions placée après lui, sur la loi d’une mention que porte une photo Lochard. Rectifions: la Partie de Crocket est de 1871.” A[dolphe] Tabarant, Manet et ses Œuvres, 5th ed. (Paris: Gallimard, 1947), 191. Also dating the painting to 1871 is Étienne Moreau-Nélaton, Manet Raconté par Lui-Même (Paris: Henri Laurens, 1926), 1:153. See also Théodore Duret, Histoire d’Édouard Manet et de Son Œuvre, Avec un Catalogue des Peintures et des Pastels, new ed. (Paris: Bernheim-Jeune, 1919), 137, no. 169. The Rouart and Wildenstein catalogue raisonné also follows this dating; see Denis Rouart and Daniel Wildenstein, Edouard Manet Catalogue raisonné (Lausanne: Bibliothèque des arts, 1975), no. 173, p. 1:154. There are two photographs by Manet’s photographer colleagues, Godet et Cie, of the Nelson-Atkins The Croquet Party (photographs of the work of Edouard Manet, undated [portions ca. 1872–74 and 1884], Morgan Library and Museum, New York, MA 3950, vol. 1, no. 21, and MA 3950, vol. 2, no. 16. The latter has an inscription dating the picture to 1871. Editions of both the Godet and Lochard photography albums owned by the Morgan Library and Museum bear different handwritten inscriptions than the albums owned by the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris. The editor would like to thank María Isabel Molestina, The Morgan Library and Museum, New York, for her assistance in researching these volumes). Wilson-Bareau and Degener have suggested an alternate date of ca. 1872, arguing that the artist may have made an undocumented trip that summer. Wilson-Bareau and Degener, Manet and the Sea, 73, 135.

-

Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 30–33.

-

Merridew’s Visitor’s Guide to Boulogne-sur-Mer and its Environs; With Some Account of Its Early History, and a Notice of the Objects Most Worthy of Visiting in the City and District (London: Simpkin, Marshall, 1874), 71.

-

Wilson-Bareau and Degener, Manet and the Sea, 73, 135.

-

There is a preliminary sketchbook drawing that shows a large group of hoops alongside a peg (Cabinet des dessins, Fonds des dessins et miniatures, Musée du Louvre, Paris Croquis [RF 30494, verso]).

-

Leenhoff noted that Manet’s idea for this picture came from croquet games played in the beach club garden at Boulogne-sur-Mer. See Léon Leenhoff, “Registre manuscrit: Œuvres d’Edouard Manet (peintures, pastels, dessins, et estampes) recensées dans son atelier en 1883 ou chez leur propriétaire,” 1883, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, Département des Estampes et photographie, 8-Yb34649 Res, folio 16, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b105469429.

-

See correspondence from Justine de Young to Simon Kelly, January 21, 2020.

-

Thanks to Justine de Young for providing the author with this image.

-

In a pastel portrait of Jeanne by Eva Gonzales from 1869–1870 (private collection), she appears with darker hair, in line with her Spanish ancestry. Manet may have therefore taken some license with her hair shade.

-

Justine de Young to Simon Kelly, January 21, 2020.

-

Juliet Wilson-Bareau argues that the sketches were not made in 1868 at the same time as the Boulogne 1868 (Whatman) sketchbook (Musée d’Orsay, Paris, RF 11169), which also “includes many blank pages, so it seems unlikely that the small Folkestone Boat and Croquet sketches were made at the same time.” She has suggested a date for these sketches of ca. 1872. See Wilson-Bareau and Degener, Manet and the Sea, 71–72. The sketchbook dates from Manet’s lengthy vacation in Boulogne in 1868 and is composed of paper watermarked “J WHATMAN.” See Juliet Wilson-Bareau and David Degener, Manet and the American Civil War: The Battle of USS Kearsarge and CSS Alabama, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2003), 69, 72n15.

-

See the following preparatory drawings for two croquet paintings by Manet from the Cabinet des dessins, Fonds des dessins et miniatures, Musée du Louvre, Paris: Femme debout, coiffée d’un chapeau, tenant un maillet de croquet, ca. 1871, pencil on laid paper (RF 30410); Femme debout, de dos, ca. 1871, pencil on laid paper (RF 30412); Homme, debout, un maillet à la main, pencil on laid paper (RF 30476); and Femme debout, tenant un maillet, pencil and watercolor on laid paper (RF 30538).

-

See Anne Distel, “Essai de récapitulation de la collection de Gustave Caillebotte,” in Anne Distel et al., Gustave Caillebotte: 1848–1894, exh. cat. (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 1994), 42–43.

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Diana M. Jaskierny, “Edouard Manet, The Croquet Party, 1871,” technical entry in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.522.2088

MLA:

Jaskierny, Diana M. “Edouard Manet, The Croquet Party, 1871,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.522.2088.

The Croquet Party was completed on a plain weaveplain weave: A basic textile weave in which one weft thread alternates over and under the warp threads. Often this structure consists of one thread in each direction, but threads can be doubled (basket weave) or tripled to create more complex plain weave. Plain weave is sometimes called tabby weave. canvas of nonstandard sizestandard-format supports: Commercially prepared supports available through art suppliers, which gained popularity in the nineteenth century during the industrialization of art materials. Available in three formats figure (portrait), paysage (landscape), and marine (marine), these were numbered 1 through 120 to indicate their size. For each numbered size, marine and paysage had two options available: a larger format (haute) and smaller (basse) format., with the nearest size being a no. 20 marine.1David Bomford, Jo Kirby, John Leighton, and Ashok Roy, Art in the Making: Impressionism (London: Yale University Press, 1991), 45–46. The Croquet Party measures 73.2 x 45.9 cm, while no. 20 marine size measured 73 x 50 cm from Bourgeois and 72.9 x 48.6 cm from Lefranc & Company. The original tacking marginstacking margins: The outer edges of canvas that wrap around and are attached to the stretcher or strainer with tacks or staples. See also tacking edge. remain intact, with one set of tack holes on each margin, spaced approximately two centimeters apart, and with minor cuspingcusping: A scalloped pattern along the canvas edges that relates to how the canvas was stretched. Primary cusping reveals where tacks secured the canvas to the support while the ground layer was applied. Secondary cusping can form when a pre-primed canvas is re-stretched by the artist prior to painting. visible on all four tacking margins.2Due to how minor the cusping appears, it is likely secondary cusping caused by the stretching onto the original stretcher (no longer extant) and not due to sizing and ground application. The ground layerground layer: An opaque preparatory layer applied to the support, either commercially or by the artist, to prevent absorption of the paint into the canvas or panel. See also priming layer. is white, smooth, and even in application. It is thinly applied, extending to the edges of the tacking margins, indicating that it was commercially primed.3Estimated single layer; no samples were taken.

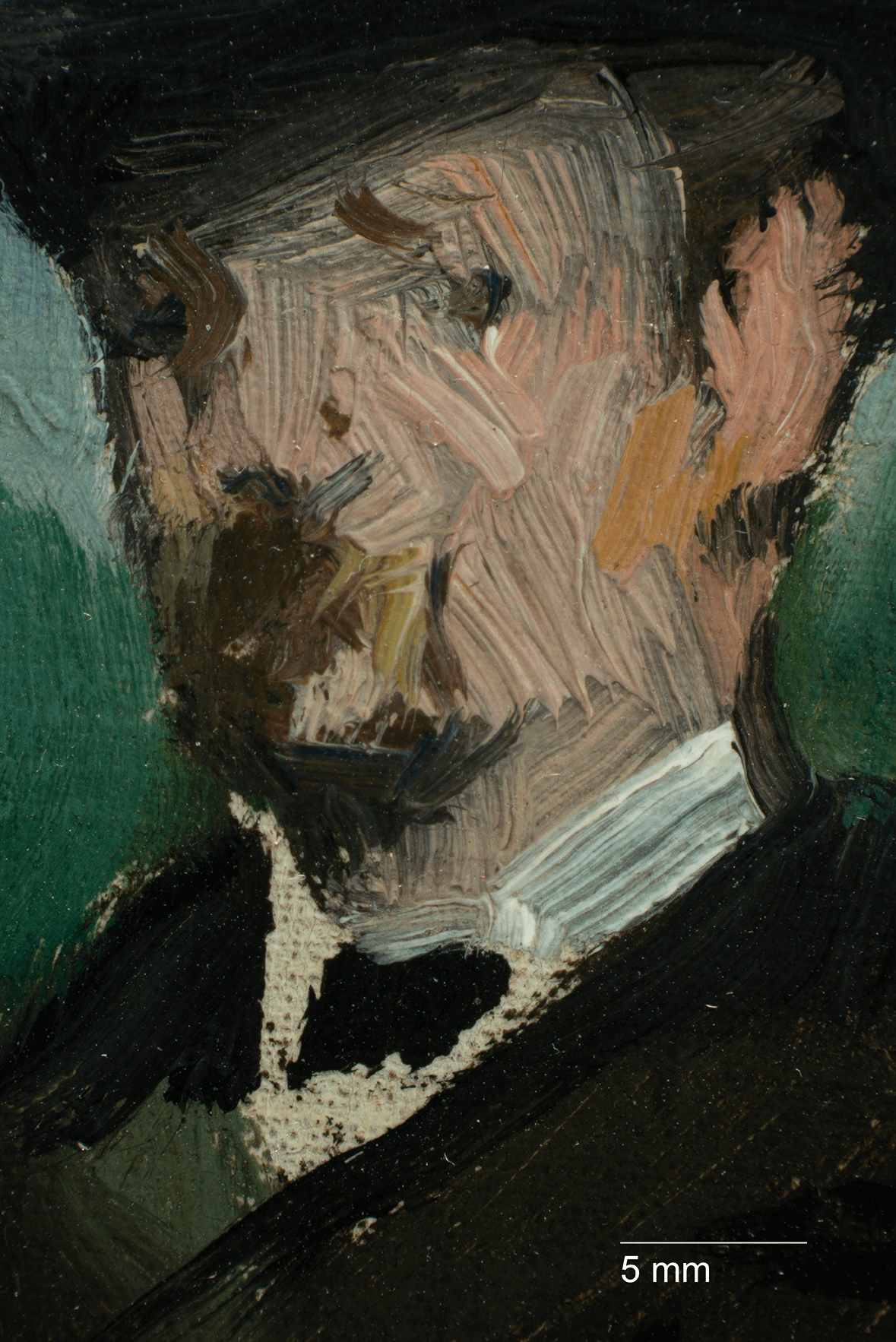

Overall the paint layer has minimal impastoimpasto: A thick application of paint, often creating texture such as peaks and ridges. and

seems to have been applied with brushes predominantly ranging from 1/8 inch to

1/2 inch, with smaller brushes likely used for details. While there is no

indication of an underdrawingunderdrawing: A drawn or painted sketch beneath the paint layer. The underdrawing can be made from dry materials, such as graphite or charcoal, or wet materials, such as ink or paint.,4With infrared reflectography, no underdrawing was detected using the Hamamatsu infrared vidicon camera.

there is outlining of compositional elements, such as the hands, which at first

glance can resemble a drawing. However, when examined with magnification, it

becomes clear that these darker "outlines" are paint strokes that exhibit

wet-over-wetwet-over-wet: An oil painting technique which involves drawing a stroke of one color across the wet paint of another color. application with the surrounding paint. The clearest

example of this is within the hands of the left female figure (Fig. 6).

Both wet-over-wet and wet-over-drywet-over-dry: An oil painting technique that involves layering paint over an already dried layer, resulting in no intermixing of paint or disruption to the lower paint strokes. paint applications are visible throughout, providing information on the paint application order.5Wet-into-wet paint application is also present, mostly found in the faces and the orange croquet ball. Minimal design preparation is visible; however, within the foreground there appears to be a lower application of uniform green paint beneath most areas of the grass. Exposed ground between the foreground figures and the grass indicates that either reservesreserve: An area of the composition left unpainted with the intention of inserting a feature at a later stage in the painting process. were left for the figures or the figures were the first compositional elements painted.6Exposed ground was a technique often used by Manet throughout his career and seen in paintings such as Music in the Tuileries Garden (1862; The National Gallery, London) and Madame Manet in the Conservatory (1879; The National Gallery of Art, Architecture, and Design, Oslo) as described by Bomford et al., Art in the Making, 115. See also Diana M. Jaskierny and Samantha Roberts, "Madame Manet in the Conservatory: A Comparison Between Two Versions," The Courtauld Institute of Art, June 26, 2016, https://assets.courtauld.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/31141247/Final-Madame-Manet-in-the-Conservatory-Research-Forum-report-26062016.pdf?_ga=2.99880669.2105545459.1581955581-78815541.1573242359. Glimpses of exposed ground within the figures suggest that there is no ébaucheébauche: The first applications of paint that begin to block in color and loosely define the compositional elements. Also called underpainting. layer, or initial blocking-in, beneath the composition.7The use of an ébauche was common practice for Manet, stemming from his training by Thomas Couture. See Devi Ormond and Catherine Schmidt Patterson with Douglas MacLennan and Nathan Daly, "The Making of a Parisienne: Manet’s Methods and Materials" in Manet and Modern Beauty: The Artist’s Last Years, ed. Scott Allen, Emily A. Beeny, and Gloria Groom (Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2019), 149–50. For more information on Manet and his use of the ébauche stage, see Anne Coffin Hanson, Manet and the Modern Tradition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979), 141–42, 158–59. Examples of this include exposed ground in the shoes of the central male figure and in the blue skirt. With no detectable underlying design for the figures, it can be assumed that the figures were the first elements painted. In transmitted lighttransmitted light: An examination technique in which light is projected through the painting to examine the painting substrate or to reveal variations in paint application., the free brushwork of the figures is visible. This is especially striking in the dress of the left female figure (Fig. 7).

In some instances, the exposed ground is used within a compositional element, such as the left male figure’s collar (Fig. 8), the left female figure’s hands, and the two right female figures’ croquet mallets (Fig. 9). White ground around the central male figure’s mallet indicates that this shape, too, was likely part of Manet’s initial compositional plan. In comparison, the lower green foreground paint extends beneath the croquet balls, the marker (Fig. 10), and the dogs, confirming that these elements were added at a later stage in his painting process.

Fig. 7. Transmitted light image of left female figure, The Croquet Party (1871)

Fig. 7. Transmitted light image of left female figure, The Croquet Party (1871)

Fig. 8. Photomicrograph of left male figure’s collar, The Croquet Party (1871)

Fig. 8. Photomicrograph of left male figure’s collar, The Croquet Party (1871)

Fig. 9. Photomicrograph of right-most figure’s mallet, The Croquet Party (1871)

Fig. 9. Photomicrograph of right-most figure’s mallet, The Croquet Party (1871)

Fig. 10. Photomicrograph of croquet marker, The Croquet Party (1871)

Fig. 10. Photomicrograph of croquet marker, The Croquet Party (1871)

Within the sea, it appears that again the background was painted around the figures, with the blue-green paint of the sea overlapping the figures slightly, as can be seen over and around the eyelashes of the left female figure (Fig. 13). Some wet-over-wet paint is visible between the sea and figures, as well as wet-over-dry and glimpses of exposed ground, indicating that varying sections were sometimes revisited and painted at different moments. The two left boats were painted wet-over-wetwet-over-wet: An oil painting technique which involves drawing a stroke of one color across the wet paint of another color. with the sea and sky, while the right-most boat was painted into the wet sky, or wet-into-wetwet-into-wet: An oil painting technique which involves blending of colors on the picture surface., creating the illusion of distance (Fig. 14).

Fig. 11. Photomicrograph of left female figure’s bodice, The Croquet Party (1871)

Fig. 11. Photomicrograph of left female figure’s bodice, The Croquet Party (1871)

Fig. 12. Photomicrograph showing green paint on center-right female figure’s face, The Croquet Party (1871)

Fig. 12. Photomicrograph showing green paint on center-right female figure’s face, The Croquet Party (1871)

Fig. 13. Photomicrograph showing middle ground (sea) paint over eyelashes of left female figure, The Croquet Party (1871)

Fig. 13. Photomicrograph showing middle ground (sea) paint over eyelashes of left female figure, The Croquet Party (1871)

Fig. 14. Photomicrograph of right-most ship, The Croquet Party (1871)

Fig. 14. Photomicrograph of right-most ship, The Croquet Party (1871)

There are two prominently raised vertical strokes when viewed in raking lightraking light: An examination technique in which light is placed at a shallow angle from one direction to reveal the surface topography., which likely reveal the earlier placement of the two flagpoles. Within the drying cracksdrying cracks: Also known as traction cracks, these are formed as the paint dries. They are usually the result of a "lean" paint with a small percentage of oil drying faster than an underlying "fat" paint layer with a higher percentage of oil. The quick drying of the top layer causes the paint layer to shrink and crack. in the sky, glimpses of brown and yellow paint of the earlier right flagpole are visible, closely resembling the colors of the existing flagpole (Fig. 16). Approximately five centimeters to the right of the flagpole pentimentopentimento (pl: pentimenti): A change to the composition made by the artist that is visible on the paint surface. Often with time, pentimenti become more visible as the upper layers of paint become more transparent with age. Italian for "repentance" or "a change of mind.", red paint is visible in drying cracks, exposing the likely original placement of the flag (Figs. 17, 18). To a lesser extent, red paint is also visible two centimeters to the right of the left flagpole pentimento. Other pentimenti include minor alterations to the shapes of the figures, such as the hat of the second figure from the right, where blue water paint has covered the brim of the hat, and the left-most figure’s right arm, which has been slimmed using green foreground paint.

Fig. 15. Transmitted light illustrating the more opaque paint in the right-side sky, The Croquet Party (1871)

Fig. 15. Transmitted light illustrating the more opaque paint in the right-side sky, The Croquet Party (1871)

Fig. 16. Photomicrograph showing brown paint through drying cracks in sky, The Croquet Party (1871)

Fig. 16. Photomicrograph showing brown paint through drying cracks in sky, The Croquet Party (1871)

Fig. 17. Detail showing red paint through drying cracks in sky, The Croquet Party (1871)

Fig. 17. Detail showing red paint through drying cracks in sky, The Croquet Party (1871)

Fig. 18. Photomicrograph showing red paint through drying cracks in sky, The Croquet Party (1871)

Fig. 18. Photomicrograph showing red paint through drying cracks in sky, The Croquet Party (1871)

Notes

-

David Bomford, Jo Kirby, John Leighton, and Ashok Roy, Art in the Making: Impressionism (London: Yale University Press, 1991), 45–46. The Croquet Party measures 73.2 x 45.9 cm, while the no. 20 marine size measured 73 x 50 cm from Bourgeois and 72.9 x 48.6 cm from Lefranc & Company.

-

Due to how minor the cusping appears, it is likely secondary cusping caused by the stretching onto the original stretcherstretcher: A wooden structure to which the painting’s canvas is attached. Unlike strainers, stretchers can be expanded slightly at the joints to improve canvas tension and avoid sagging due to humidity changes or aging. (no longer extant) and not due to sizingsizing layer: A dilute glue layer, usually animal-based protein such as hide glue, applied to a canvas prior to the ground and paint layers. Its purpose is to shrink the canvas before use and to act as a sealant, protecting the canvas from degradation of acidic materials, such as oils. The glue material is often called size, while the process is called sizing. and ground application.

-

Estimated single layer; no samples were taken.

-

Wet-into-wetwet-into-wet: An oil painting technique which involves blending of colors on the picture surface. paint application is also present, mostly found in the faces and the orange croquet ball.

-

Exposed ground was a technique often used by Manet throughout his career and seen in paintings such as Music in the Tuileries Garden (1862; The National Gallery, London) and Madame Manet in the Conservatory (1879; The National Gallery of Art, Architecture, and Design, Oslo) as described by Bomford et al., Art in the Making, 115. See also Diana M. Jaskierny and Samantha Roberts, “Madame Manet in the Conservatory: A Comparison Between Two Versions,” The Courtauld Institute of Art, June 26, 2016, https://assets.courtauld.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/31141247/Final-Madame-Manet-in-the-Conservatory-Research-Forum-report-26062016.pdf.

-

The use of an ébauche was common practice for Manet, stemming from his training with Thomas Couture. See Devi Ormond and Catherine Schmidt Patterson with Douglas MacLennan and Nathan Daly, “The Making of a Parisienne: Manet’s Methods and Materials” in Manet and Modern Beauty: The Artist’s Last Years, ed. Scott Allen, Emily A. Beeny, and Gloria Groom (Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2019), 149–50. For more information on Manet and his use of the ébauche stage, see Anne Coffin Hanson, Manet and the Modern Tradition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979), 141–42, 158–59.

-

Hanson, Manet and the Modern Tradition, 160–61. See also Ormond et al., Manet and Modern Beauty, 156.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Mary Frances Ivey, “Edouard Manet, The Croquet Party, 1871,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.522.4033

MLA:

Ivey, Mary Frances. “Edouard Manet, The Croquet Party, 1871,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.522.4033

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Mary Frances Ivey, “Edouard Manet, The Croquet Party, 1871,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.522.4033

MLA:

Ivey, Mary Frances. “Edouard Manet, The Croquet Party, 1871,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.522.4033.

The artist, Paris, 1871–1879;

Purchased from the artist by Gustave Caillebotte (1848–1894), Paris, 1879–February 21, 1894 [1];

To his brother, Martial Caillebotte (1853–1910), Paris, 1894–January 16, 1910 [2];

Inherited by his wife, Marie Caillebotte (née Minoret, 1863–1931), Paris or Pornic, France, 1910–October 5, 1931;

By descent to her daughter, Geneviève Chardeau (née Caillebotte, 1890–1986), Paris, 1931–1973 [3];

Deposited with Galerie Lorenceau, Paris, by a member of the Chardeau family, January 23, 1973 [4];

Possibly with Galerie Schmit, Paris, after January 23, 1973 [5];

Purchased [from Galerie Schmit?] by Juan Guillermo de Beistegui (1930–2017), Paris, after January 23, 1973–January 7, 1986 [6];

Purchased from de Beistegui, through Margo Pollins Schab, New York, by Marion (née Helzberg, 1931–2013) and Henry (1922–2019) Bloch, Shawnee Mission, KS, 1986–June 15, 2015 [7];

Their gift to The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 2015.

Notes

[1] See Étienne Moreau-Nélaton, “Copie faite pour E. Moreau-Nélaton de documents sur Manet appartenant à Léon Leenhoff,” ca. 1910, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Département des Estampes et photographie, RESERVE 8-YB3-2401, folio 79, as Croquet. On November 20, 1883, Caillebotte added a codicil to his will stipulating that his collection should be given to the Musée du Luxembourg after his death. The museum was notified of this bequest in early March 1894, but many of the paintings, including The Croquet Party, were refused by the Comité consultatif des musées nationaux after 18 months of deliberation and returned to his brother, Martial Caillebotte. See [Adolphe] Tabarant, “Le peintre Caillebotte et sa collection,” Bulletin de la Vie Artistique, no. 15 (August 1, 1921): 405–13; and A[dolphe] Tabarant, Manet: Histoire catalographique (Paris: Éditions Montaigne, 1931), 244.

[2] Martial Caillebotte, the artist’s younger brother, offered The Croquet Party to the French government in 1904 and 1908, but it was refused both times. See Bernard Denvir, The Chronicle of Impressionism: An Intimate Diary of the Lives and World of the Great Artists (London: Thames and Hudson, 1993), 198.

[3] See emails from Gilles Chardeau, grandson of Geneviève Chardeau, to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, July 30, 2015; Sylvie Brame, Galerie Brame et Lorenceau, to Mary Frances Ivey, NAMA, November 30, 2018; and Sophie Pietri, Wildenstein-Plattner Institute, to Mary Frances Ivey, NAMA, December 17, 2018, NAMA curatorial files.

On August 4, 1970, seventeen paintings in Chardeau’s collection, including “The Croquet Game,” were stolen. They were returned anonymously to a Paris metro station in November 1970 and restituted to Chardeau. See Janet Flanner, “Letters from Paris,” New Yorker (August 22, 1970): 85, as The Croquet Game.

[4] See emails from Sophie Pietri, Wildenstein-Plattner Institute, to Mary Frances Ivey, NAMA, December 17, 2018, and Sylvie Brame, Galerie Brame et Lorenceau, to Mary Frances Ivey, NAMA, November 30, 2018, NAMA curatorial files.

A sales receipt from Margo Pollins Schab indicates that the painting was owned by the Peugeot family, France, before its purchase by de Beistegui. This was published in Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 155. However, neither Pollins Schab nor the Peugeot family can confirm this information. Conversation with Margo Pollins Schab and Mary Frances Ivey, NAMA, January 11, 2019, and email from Dominix Kirchner, Peugeot family descendant, to Mary Frances Ivey, NAMA, February 13, 2019, NAMA curatorial files.

[5] See email from Miguel de Beistegui, son of Juan Guillermo de Beistegui, to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, May 15, 2015, NAMA curatorial files. Galerie Schmit has not responded to emails.

[6] According to Denis Rouart and Daniel Wildenstein, Edouard Manet: Catalogue raisonné, vol. 1, Peintures (Lausanne: Bibliothèque des arts, 1975), no. 173, the painting was owned by P. A., Suisse, or “propriété anonyme.” De Beistegui did not live in Switzerland and was living in Paris at the time that he purchased the w ork; see email from Miguel de Beistegui, son of Juan Guillermo de Beistegui, to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, May 15, 2015, NAMA curatorial files.

[7] Conversation with Margo Pollins Schab and Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, May 18, 2015, notes in NAMA curatorial files. According to Schab, her gallery had The Croquet Party on consignment from Juan de Beistegui.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Mary Frances Ivey, “Edouard Manet, The Croquet Party, 1871,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.522.4033

MLA:

Ivey, Mary Frances. “Edouard Manet, The Croquet Party, 1871,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.522.4033.

Edouard Manet, The Croquet Game, 1873, oil on canvas, 28 5/16 x 41 3/4 in. (72 x 106 cm), Städel Museum, Frankfurt.

Preparatory Works

Citation

Chicago:

Mary Frances Ivey, “Edouard Manet, The Croquet Party, 1871,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.522.

MLA:

Ivey, Mary Frances. “Edouard Manet, The Croquet Party, 1871,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.522.

Edouard Manet, Femme, debout, coiffé d’un chapeau, 1875, graphite on laid paper, 3 15/16 x 2 1/2 in. (10 x 6.3 cm), Musée du Louvre, Paris, Cabinet des dessins, Fonds des dessins et miniatures, RF 30409, Recto.

Edouard Manet, Femme debout, coiffée d’un chapeau, tenant un maillet de croquet, 1875, graphite on laid paper, 4 x 2 1/2 in. (10.1 x 6.3 cm), Musée du Louvre, Paris, Cabinet des dessins, Fonds des dessins et miniatures, RF 30410, Recto.

Edouard Manet, Femme debout, coiffée d’un chapeau, 1875, graphite on laid paper, 3 13/16 x 2 1/2 in. (9.7 x 6.4 cm), Musée du Louvre, Paris, Cabinet des dessins, Fonds des dessins et miniatures, RF 30411, Recto.

Edouard Manet, Femme debout, de dos, 1875, graphite on laid paper, 4 x 2 1/2 in. (10.1 x 6.4 cm), Musée du Louvre, Paris, Cabinet des dessins, Fonds des dessins et miniatures, RF 30412, Recto.

Edouard Manet, Femme debout, tenant un maillet, ca. 1871–1873, graphite on laid paper, 4 x 2 1/2 in. (10.3 x 6.3 cm), Musée du Louvre, Paris, Cabinet des dessins, Fonds des dessins et miniatures, RF 30418, Recto.

Edouard Manet, Feuille d’études avec personnages, ca. 1871–1873, graphite on laid paper, 7 3/4 x 4 7/8 in. (19.7 x 12.4 cm), Musée du Louvre, Paris, Cabinet des dessins, Fonds des dessins et miniatures, RF 30475, Recto.

Edouard Manet, Homme, debout, un maillet à la main, ca. 1871–1873, graphite on laid paper, 4 x 2 1/2 in. (10.3 x 6.4 cm), Musée du Louvre, Paris, Cabinet des dessins, Fonds des dessins et miniatures, RF 30476, Recto.

Edouard Manet, Homme, de dos, jouant au croquet, ca. 1871–1873, graphite on laid paper, 3 7/8 x 2 1/2 in. (9.8 x 6.3 cm), Musée du Louvre, Paris, Cabinet des dessins, Fonds des dessins et miniatures, RF 30478, Recto.

Edouard Manet, Femme debout, tenant un maillet, ca. 1871–1873, graphite with brown wash on laid paper, 3 15/16 x 2 1/2 in. (10 x 6.4 cm), Musée du Louvre, Paris, Cabinet des dessins, Fonds des dessins et miniatures, RF 30538, Recto.

Edouard Manet, Femme debout, jouant au croquet, ca. 1871–1873, graphite retouched with watercolor on laid paper, 3 15/16 x 2 1/2 in. (10 x 6.4 cm), Musée du Louvre, Paris, Cabinet des dessins, Fonds des dessins et miniatures, RF 30539, Recto.

Edouard Manet, Femme debout, de face, jouant au croquet, ca. 1871–1873, graphite retouched with watercolor on laid paper, 3 15/16 x 2 1/2 in. (10 x 6.4 cm), Musée du Louvre, Paris, Cabinet des dessins, Fonds des dessins et miniatures, RF 30540, Recto.

Edouard Manet, Deux personnages en plein air, jouant au croquet, ca. 1871–1873, watercolor, 3 15/16 x 2 1/2 in. (10 x 6.4 cm), Musée du Louvre, Paris, Cabinet des dessins, Fonds des dessins et miniatures, RF 30459 Recto.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Mary Frances Ivey, “Edouard Manet, The Croquet Party, 1871,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.522.4033

MLA:

Ivey, Mary Frances. “Edouard Manet, The Croquet Party, 1871,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.522.4033.

Exposition des Œuvres de Édouard Manet, École nationale des beaux-arts, Paris, January 1884, no. 73, as La partie de crocket [sic].

Works in Oil and Pastel by the Impressionists of Paris, American Art Association, New York, April 10–28, 1886; National Academy of Design, New York, May 25–June 30, 1886, no. 249, as A Game of Croquet.

Le Salon d’automne, 3ème Exposition: Peinture, dessin, sculpture, gravure, architecture et art décoratif exposés au Grand Palais des Champs-Elysées du 18 octobre 1905 au 25 novembre 1905, Société du Salon d’Automne, Galeries Nationales d’Exposition du Grand Palais, Paris, 1905, as Partie de Croquet.

Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, June 9–September 9, 2007, no. 1, as The Croquet Party (La partie de croquet).

References

Citation

Chicago:

Mary Frances Ivey, “Edouard Manet, The Croquet Party, 1871,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.522.4033

MLA:

Ivey, Mary Frances. “Edouard Manet, The Croquet Party, 1871,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.522.4033.

Anatole Godet, Reproductions de tableaux d’Edouard Manet: photographies (n.p.: 1872), unpaginated, (repro.).

Léon Leenhoff, “Registre manuscrit: Œuvres d’Edouard Manet (peintures, pastels, dessins, et estampes) recensées dans son atelier en 1883 ou chez leur propriétaire,” 1883, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, Département des Estampes, Yb3 4649 Res, folio 16, as Partie de crocket faites dans le jardin des Casino de Boulogne sur Mer.

Joséphin Péladan, “Le procédé de Manet: D’après l’exposition de l’École des beaux-arts,” L’Artiste 1 (February 1884): 114, as Partie de Crocket [sic].

Exposition des œuvres de Édouard Manet, exh. cat. (Paris: Imprimerie de A. Quantin, 1884), 49, as La partie de crocket [sic].

Works in Oil and Pastel by the Impressionists of Paris, exh. cat. (New York: J. J. Little, 1886), 39, as A Game of Croquet.

H. N., “Enquète: À Propos de la Collection Caillebotte,” Journal des Artistes (April 8, 1894): 529–30.

Théodore Duret, Histoire d’Édouard Manet et de son œuvre (Paris: H. Floury, 1902), no. 169, pp. 102, 243–44, as La Partie de crocket [sic].

Hugo von Tschudi, Édouard Manet (Berlin: Bruno Cassirer, 1902), 32–33.

“Manet et le Salon d’automne,” L’ermitage: Revue de littérature et d’art 2, no. 8 (August 15, 1905): 128, as Partie de Croquet.

La Revue 7, no. 47 (September 1, 1905): 262, as Partie de Croquet.

François Benoit et al., Histoire du Paysage en France (Paris: Librairie Renouard et H. Laurens, 1908), 308.

Julius Meier-Graefe, Édouard Manet (Munich: Piper, 1912), 219–20, (repro.), as La Partie de Crocket [sic].

Théodore Duret, Histoire d’Édouard Manet et de Son Œuvre, Avec un Catalogue des Peintures et des Pastels, new ed. (Paris: Bernheim-Jeune, 1919), no. 169, pp. 137, 259, as La Partie de Croquet.

Adolphe Tabarant, “Le peintre Caillebotte et sa collection,” Le Bulletin de la Vie Artistique, no. 15 (August 1, 1921): 406, 410–13, (repro.), as La partie de crocket [sic].

Étienne Moreau-Nélaton, Manet Raconté par Lui-Même (Paris: Henri Laurens, 1926), 1:134–35, 153; 2:3–4, 111, as La partie de crocket [sic].

Waldemar George, “Art in France,” Burlington Magazine 51 no. 292 (July 1927): 49–50.

Adolphe Tabarant, Manet: Histoire catalographique (Paris: Éditions Montaigne, 1931), no. 194, pp. 243–44, as Partie de Crocket à Boulogne [sic].

Paul Jamot and Georges Wildenstein, Manet (Paris: Beaux-Arts, 1932), no. 197, 1:89, 142; 2:175, (repro.), as La Partie de Croquet.

Gotthard Jedlicka, Edouard Manet (Erlenbach, Switzerland: Eugen Rentsch, 1941), 172, as Krocketpartie.

Hans Huth, “Impressionism Comes to America,” Gazette des Beaux-Arts 29 (April 1946): 239–40 as Croquet Party.

Michel Florisoone, Manet (Monaco: Documents d’art, 1947), XX, as Partie de croquet.

Adolphe Tabarant, Manet et ses Œuvres, 5th ed. (Paris: Gallimard, 1947), 114, 191, 491, 512, 538, 608, (repro.), as Partie de crocket à Boulogne [sic].

Jacques Lethève, Impressionnistes et Symbolistes devant la presse (Paris: Armand Colin, 1959), 147.

Germain Bazin, Trésors de l’Impressionnisme au Louvre, 3rd ed. (1958; Paris: Éditions Aimery Somogy, 1965), 45, 45n1, as Joueurs de croquet.

Sandra Orienti, The Complete Paintings of Manet, 1st ed. (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1967), no. 151, p. 100, (repro.), as Partie de Croquet à Boulogne-Sur-Mer (The Game of Croquet at Boulogne-sur-Mer).

Sandra Orienti, The Complete Paintings of Manet, 2nd ed. (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1970), no. 151, p. 100, (repro.), as Partie de Croquet à Boulogne-Sur-Mer (The Game of Croquet at Boulogne-sur-Mer).

Alain de Leiris, The Drawings of Edouard Manet (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1969), 35n48, 71n20, 119–20, as La Partie de croquet à Boulogne.

Janet Flanner, “Letters from Paris,” New Yorker (August 22, 1970): 85, as The Croquet Game.

“Paris Police Fine Art Haul in Metro,” Times (London), no. 58026 (November 18, 1970): 5.

Pierre Courthion, Impressionism, trans. John Shepley (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1972), 110, as Partie de croquet.

Denis Rouart and Daniel Wildenstein, Edouard Manet: Catalogue raisonné, vol. 1, Peintures (Lausanne: Bibliothèque des arts, 1975), no. 173, pp. 5–6, 27, 154–55, (repro.), as La Partie de croquet.

Alice Bellony-Rewald, The Lost World of the Impressionists (London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1976), 79, 282, (repro.), as The Croquet Party.

Jeanne Laurent, Pierre Vaisse, and Jacques Chardeau, “The New Caillebotte Affair,” October 31 (Winter 1984): 69–90.

Kirk Varnedoe, Gustave Caillebotte (1987; repr. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000), 203, as La partie de croquet.

Nicolai Cikovsky, ed., Winslow Homer: A Symposium, proceedings of the Symposium “Winslow Homer” sponsored by the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts, National Gallery of Art, 18 April 1986 (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1990), 87n42.

Juliet Wilson-Bareau, Manet by Himself: Correspondence and Conversation; Paintings, Pastels, Prints and Drawings (London: Macdonald, 1991), 197, 311, (repro.), as Croquet at Boulogne.

Vivien Perutz, Edouard Manet (Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press, 1993), 154, as Croquet Party.

Marie Berhaut, Gustave Caillebotte: Catalogue Raisonné des Peintures et Pastels, rev. ed. (Paris: Wildenstein Institute, 1994), 281, as La Partie de croquet.

Anne Distel et al., Gustave Caillebotte: 1848–1894, exh. cat. (Paris: Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 1994), 31, 42–43, 360, 374, (repro.), as La Partie de croquet.

Klaus Herding et al., eds., Impressionisten/Städel, exh. cat. (Frankfurt: Städel, 1999), 66–83.

Nancy Locke, Manet and the Family Romance (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001), 126, 128, 222, (repro.), as The Croquet Party at Boulogne-sur-Mer.

Ina Conzen, Edouard Manet: und die Impressionisten (Stuttgart: Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, 2002), 70, (repro.), as Die Krocketpartie.

James E. Cutting, “Gustave Caillebotte, French Impressionism, and Mere Exposure,” Psychonomic Bulletin and Review 10, no. 2 (2003): 339.

Pierre Cabanne, Les grands collectionneurs (Paris: Les Éditions de l’Amateur, 2003), 236, as La Partie de croquet.

David Degener and Juliet Wilson-Bareau, Manet and the Sea, exh. cat. (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2003), 72–73, 96n78, 96n79, 96n80, 97n82, 135, (repro.), as Croquet at Boulogne.

Caillebotte: Au cœur de l’impressionnisme, exh. cat. (Lausanne: Bibliothèque des Arts, 2005), 178, as La partie de crocket [sic].

Rebecca Dimling Cochran and Bobbie Leigh, “100 Top Collectors Who Have Made a Difference,” Arts and Antiques 29, no. 3 (March 2006): 90, as The Croquet Party.

Bobbie Leigh, “Magnificent Obsession,” Art and Antiques 29, no. 6 (June 2006): 65, as The Croquet Party.

“Inaugural Exhibitions Celebrate Kansas City,” Member Magazine (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (Fall 2006): 3.

Sidsel Maria Søndergaard, ed., Women in Impressionism: From Mythical Feminine to Modern Woman, exh. cat. (Milan: Skira, 2006), 204, 209, 223n60, (repro.), as The Croquet Party.

Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 2, 11, 15, 30–33, 153, 155, (repro.), as The Croquet Party (La partie de croquet).

Alice Thorson, “First Public Exhibition: Marion and Henry Bloch’s Art Collection,” Kansas City Star (June 3, 2007): E4.

“Lasting Impressions: A Tribute to Marion and Henry Bloch,” Member Magazine (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (Fall 2007): 12.

Steve Paul, “Pretty Pictures: Marion and Henry Bloch’s collection of superb Impressionist masters,” Panache 4, no. 3 (Fall 2007): 24, (repro.), as The Croquet Party.

“Kansas City Riches,” New York Times 159, no. 54,942 (February 5, 2010): C26.

Alice Thorson, “Museum to Get 29 Impressionist Works from the Bloch Collection,” Kansas City Star (February 5, 2010): A1.

James H. Rubin, Manet: Initial M, Hand and Eye (Paris: Flammarion, 2010), 290–92, 294, (repro.), as Croquet at Boulogne.

Thomas M. Bloch, Many Happy Returns: The Story of Henry Bloch, America’s Tax Man (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, 2011), 174, as The Croquet Party.

Manet: Portraying Life, exh. cat. (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2012), 199.

Nancy Locke, “Visible Specters, Images from the Atmosphere,” Nonsite no. 14 (December 15, 2014): https://nonsite.org/article/visible-specters, (repro.), as Croquet Party at Boulogne.

Diane Stafford, “Bloch Gift to Go for Nelson Upgrade,” Kansas City Star 135, no. 203 (April 8, 2015): A1, A8, (repro.), as The Croquet Party.

“World-Class Bloch Art Collection Will Be on Permanent View in Renovated Galleries at the Nelson-Atkins,” Artdaily.org (April 9, 2015): http://artdaily.com/news/77729/World-class-Bloch-Art-Collection-will-be-on-permanent-view-in-renovated-galleries-at-the-Nelson-Atkins#.VSayTFI5C9I, as The Croquet Party.

“Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art officially accessions Bloch Impressionist masterpieces,” Artdaily.org (July 25, 2015): http://artdaily.com/news/80246/Nelson-Atkins-Museum-of-Art-officially-accessions-Bloch-Impressionist-masterpieces#.V6oGwlKFO9I, as The Croquet Party.

Julie Paulais, “Le Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art reçoit des tableaux impressionnistes en échange de leurs répliques,” Le Journal des arts (July 30, 2015): http://www.lejournaldesarts.fr/site/archives/docs_article/129801/le-nelson-atkins-museum-of-art-recoit-des-tableaux-impressionnistes-en-echange-de-leurs-repliques.php, (repro.), as Partie de croquet à Boulogne-sur-Mer.

Josh Niland, “The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Acquires a Renowned Collection of Impressionist and Postimpressionist Art,” architecturaldigest.com (August 6, 2015): https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/nelson-atkins-museum-accessions-bloch-art-collection, (repro.), as The Croquet Party,

Nancy Staab, “Van Gogh is a Go!” 435: Kansas City’s Magazine (September 2015): 76, (repro.), as The Croquet Party.

Felix Krämer, ed., Monet and the Birth of Impressionism, exh. cat. (Munich: Prestel, 2015), 137–38, (repro.), as The Game of Croquet / La Partie de croquet.

Nina Siegal, “Upon Closer Review, Credit Goes to Bosch,” New York Times 165, no. 57130 (February 2, 2016): C5.

“Nelson-Atkins to unveil renovated Bloch Galleries of European Art in winter 2017,” Artdaily.org (July 20, 2016): (repro.), as The Croquet Party, http://artdaily.com/news/88852/Nelson-Atkins-to-unveil-renovated-Bloch-Galleries-of-European-Art-in-winter-2017-#.W-NDepNKhaQ.

Catherine Futter et al., Bloch Galleries: Highlights from the Collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2016): 70, (repro.), as The Croquet Party.

Albert Hect, “Henry Bloch’s Masterpieces Collection to Go on Display at Nelson-Atkins Museum,” Jewish Business News (February 26, 2017): http://jewishbusinessnews.com/2017/02/26/henry-bloch-masterpieces-collection/.

David Frese, “Inside the Bloch Galleries: An interactive experience,” Kansas City Star 137, no. 169 (March 5, 2017): 1D, 5D, (repro.), as The Croquet Party.

“Editorial: Thank you, Henry and Marion Bloch”, Kansas City Star (March 7, 2017): http://www.kansascity.com/opinion/editorials/ article137040948.html.

Hampton Stevens, “(Not Actually) 12 Things To Do During The Big 12 Tournament,” Flatland: KCPT’s Digital Magazine (March 9, 2017): http://www.flatlandkc.org/arts-culture/sports/not-actually-12-big-12-tournament/.

Laura Spencer, “The Nelson-Atkins’ Bloch Galleries feature Old Masterworks and New Technology,” KCUR (March 10, 2017): http://kcur.org/post/nelson-atkins-bloch-galleries-feature-old-masterworks-and-new-technology#stream/0.

Victoria Stapley-Brown, “Nelson-Atkins Museum’s new European art galleries come with a ‘love story’,” Art Newspaper (March 10, 2017): http://theartnewspaper.com/news/museums/nelson-atkins-museum-s-new-european-art-galleries-come-with-a-love-story/.

Harry Bellet, “Don du ciel pour le Musée Nelson-Atkins,” Le Monde (March 13, 2017): http://www.lemonde.fr/arts/article/2017/03/13/don-du-ciel-pour-le-musee-nelson-atkins_5093543_1655012.html, (repro.).

Menachem Wecker, “Jewish Philanthropist Establishes Kansas City as Cultural Mecca,” Forward (March 14, 2017): http://forward.com/culture/365264/jewish-philanthropist-establishes-kansas-city-as-cultural-mecca/ [repr. in Menachem Wecker, “Kansas City Collection Is A Chip Off the Old Bloch,” Forward (March 17, 2017): 20–22].

Juliet Helmke, “The Bloch Collection Takes up Residence in Kansas City’s Nelson Atkins Museum,” BlouinArtInfo International (March 15, 2017): http://www.blouinartinfo.com/news/story/2005267/the-bloch-collection-takes-up-residence-in-kansas-citys.

Erich Hatala Matthes, “Digital replicas are not soulless—they help us engage with art,” Apollo: The International Art Magazine (March 23, 2017): https://www.apollo-magazine.com/digital-replicas-3d-printing-original-artworks/.

Louise Nicholson, “How Kansas City got its magnificent museum,” Apollo: The International Art Magazine (April 7, 2017): https://www.apollo-magazine.com/how-kansas-city-got-its-magnificent-museum/.

Lilly Wei, “Julián Zugazagoitia: ‘Museums should generate interest and open a door that leads to further learning,’” Studio International (August 21, 2017): http://studiointernational.com/index.php/julian-zugazagoitia-director-nelson-atkins-museum-of-art-kansas-city-interview.

Robert D. Hershey Jr., “Henry Bloch, H&R Block’s cofounder, dies at 96,” Boston Globe (April 23, 2019): https://www3.bostonglobe.com/metro/obituaries/2019/04/23/henry-bloch-block-cofounder/?arc404=true.

Robert D. Hershey Jr., “Henry W. Bloch, fTax-Preparation Pioneer (and Pitchman), Is Dead at 96,” New York Times (April 23, 2019): https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/23/obituaries/henry-w-bloch-dead.html.

Ignacio Villarreal, “Nelson-Atkins mourns loss of Henry Bloch,” ArtDaily.org (April 24, 2019): http://artdaily.com/news/113035/Nelson-Atkins-mourns-loss-of-Henry-Bloch#.XMB76qR7laQ, as The Croquet Party.

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “H&R Block co-founder, philanthropist Bloch dies,” Cass County Democrat Missourian 140, no. 29 (April 26, 2019): 1A.

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “KC businessman and philanthropist Henry Bloch dies,” Lee’s Summit Journal 132, no. 79 (April 26, 2019): 1A.

Luke Nozicka, “Family and friends remember Henry Bloch of H&R Block,” Kansas City Star 139, no. 225 (April 30 2019): 4A [repr. Luke Nozicka, “Family and friends remember Henry Bloch of H&R Block,” Kansas City Star 139, no. 228 (May 3, 2019): 3A].