Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Pierre Bonnard, The White Cupboard, 1931–1932,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.706.5407.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Pierre Bonnard, The White Cupboard, 1931–1932,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.706.5407.

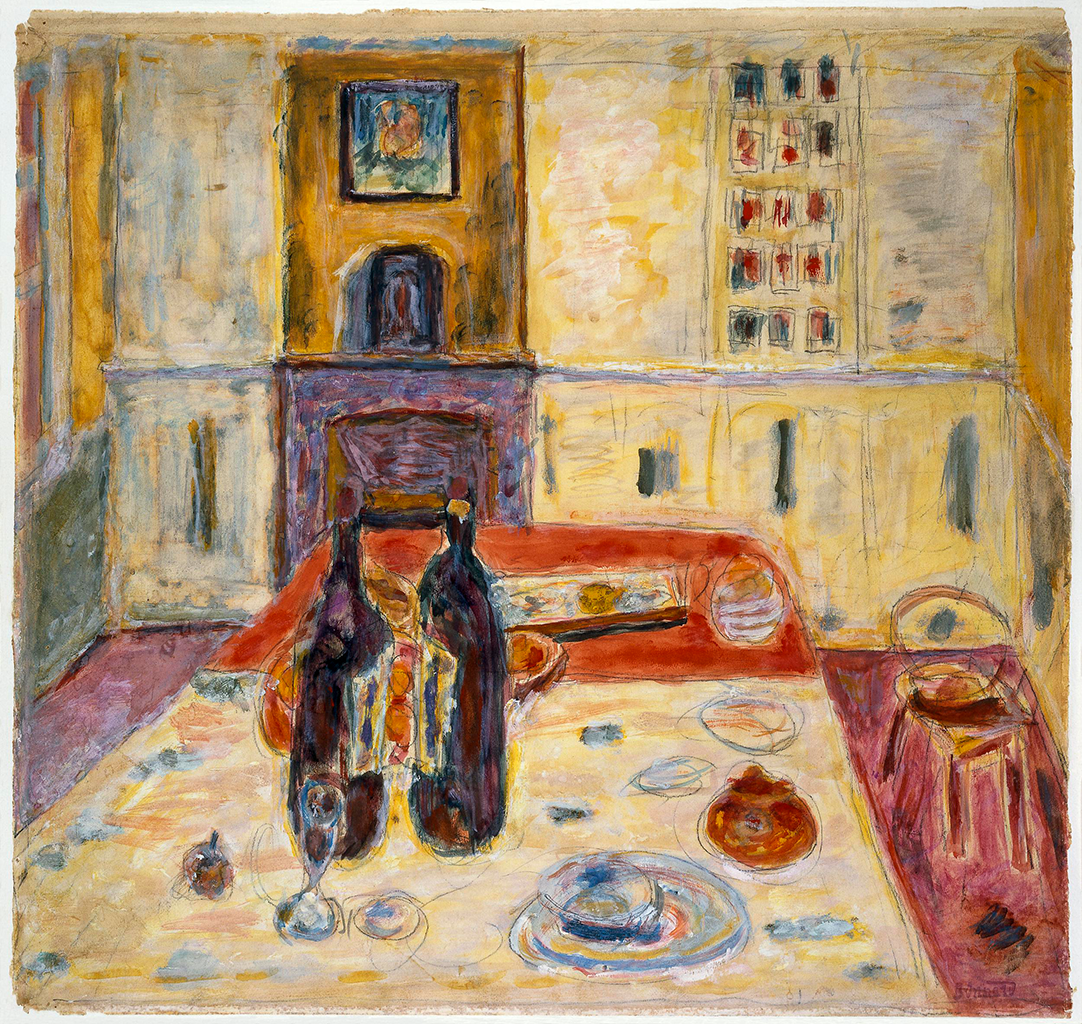

Pierre Bonnard was a mature artist in the fifth decade of his career

when he painted The White Cupboard. A sizable picture measuring more

than four feet tall by three feet wide, it appears, at first glance, to

record a simple domestic scene: a woman arranging dishware in a dining

room cabinet. The setting is Le Bosquet (French for “The Grove”),

Bonnard’s hilltop property in the village of Le Cannet. Located near

Cannes in southern France, Le Cannet was much quieter than its flashy

neighbor in the early twentieth century. Fewer than seven thousand

people inhabited Le Cannet when Bonnard purchased a house there in 1926,

compared to more than forty-two thousand living in Cannes.1For census data, see Claude Motte and Marie-Christine Vouloir, “Le Cannet” and “Cannes,” Des villages de Cassini aux communes d’aujourd’hui, Laboratoire de démographie historique, Centre national de la recherche scientifique, École des hautes études en sciences sociales, accessed November 8, 2022, http://cassini.ehess.fr/fr/html/fiche.php?select_resultat=6809 and http://cassini.ehess.fr/fr/html/fiche.php?select_resultat=6809. Le Cannet had 6,244 residents in 1926, whereas Cannes boasted 42,427. An early

twentieth-century postcard offers a general view of Le Cannet, with its

historic Church of Sainte-Catherine in the left foreground and private

dwellings scattered among the highlands (Fig. 1).2This postcard bears the insignia of ND Phot., a Parisian publishing house founded as Neurdein Frères around 1885 and renamed ND Phot. in 1906. See “Neurdein Frères / Neurdein et Cie / ND Phot.,” Dumbarton Oaks Archives, accessed November 8, 2022, https://www.doaks.org/research/library-archives/dumbarton-oaks-archives/collections/ephemera/names/nd-phot. Like many of the

homes seen here, Bonnard’s villa overlooked the Esterel mountains, which

he painted on several occasions.3See, for example, Pierre Bonnard, Landscape at Le Cannet, 1928, oil on canvas, 50 3/8 x 109 1/2 in. (128 x 278.2 cm), Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, TX, AP 2018.01, https://kimbellart.org/collection/ap-201801. Although Le Bosquet was not the

artist’s sole residence—he also owned real estate in Vernonnet and

maintained both a studio and an apartment in Paris—he spent the majority

of his time in Le Cannet from the late 1920s onward, as evidenced by his

creative output. By one scholar’s tally, Bonnard produced 217 oil

paintings and fifty-nine gouaches of his beloved Le Bosquet.4Michel Terrasse, Bonnard at Le Cannet, trans. Sebastien Wormell (New York: Pantheon Books, 1988), 121.

The female figure in the Nelson-Atkins work is Bonnard’s wife and model, Marthe de Méligny (née Maria Boursin, 1869–1942).5The timing of and motivation for Marthe’s name change are unclear. Tradition has it that Marthe introduced herself to Bonnard as “Marthe de Méligny” when they first met, but Lucy Whelan casts doubt on this long-held assumption; see Lucy Whelan, “New Light on Pierre Bonnard’s Wife and Model Marthe,” Burlington Magazine 162, no. 1406 (May 2020): 417–18. According to Marthe’s great-niece Pierrette Vernon, Marthe’s adopted surname probably derives from a village in the Cher department called Méligny, close to where Marthe grew up. See Sarah Whitfield, “Fragments of an Identical World,” in Sarah Whitfield and John Elderfield, Bonnard, exh. cat. (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1998), 30n41. Due to this complex history, scholars refer to Bonnard’s wife simply as “Marthe” in the literature on him; I have followed their lead. Born near Bourges in central France to a working-class family, she moved to Paris in the late 1880s with her mother and two older sisters and sought employment in the artificial flower trade. It is often reported that Marthe met Bonnard while peddling flowers on the Boulevard Haussmann,6See, for example, William D. Montalbano, “A Brush With, or Without, Greatness?” Los Angeles Times (March 21, 1998): https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1998-mar-21-ca-31063-story.html; and and Alastair Sooke, “In the Bath with Mrs. Bonnard: How the Painter’s Difficult Marriage Inspired His Art,” Telegraph (January 20, 2019): https:www.telegraph.co.uk/art/artists/bath-mrs-bonnard-painters-difficult-marriage-inspired-spellbinding/. but the precise circumstances of both their first encounter and Marthe’s job are unknown; like many fleuristes, Marthe may have been a factory worker producing artificial blooms for the millinery industry.7Whelan, “New Light,” 413. In any case, Marthe and Bonnard crossed paths around 1893, when she began appearing in the artist’s paintings and journal entries, but—contrary to popular belief—they did not form a lifelong attachment straightaway.8Whitfield’s statement that “at the age of twenty-six, Bonnard decided to make his life with Marthe” is typical of the scholarship on the artist. See Whitfield, “Fragments of an Identical World,” 15. As Lucy Whelan revealed, Marthe married another man sometime before 1899. Little is known of their union, but it seems to have fizzled by 1905–1907, when Marthe resurfaced in Bonnard’s pictures and diaries. For the next three and a half decades, she was his near-constant companion. They wed belatedly in 1925, perhaps after the death or divorce of Marthe’s first husband.9Whelan, “New Light,” 414–16, 418.

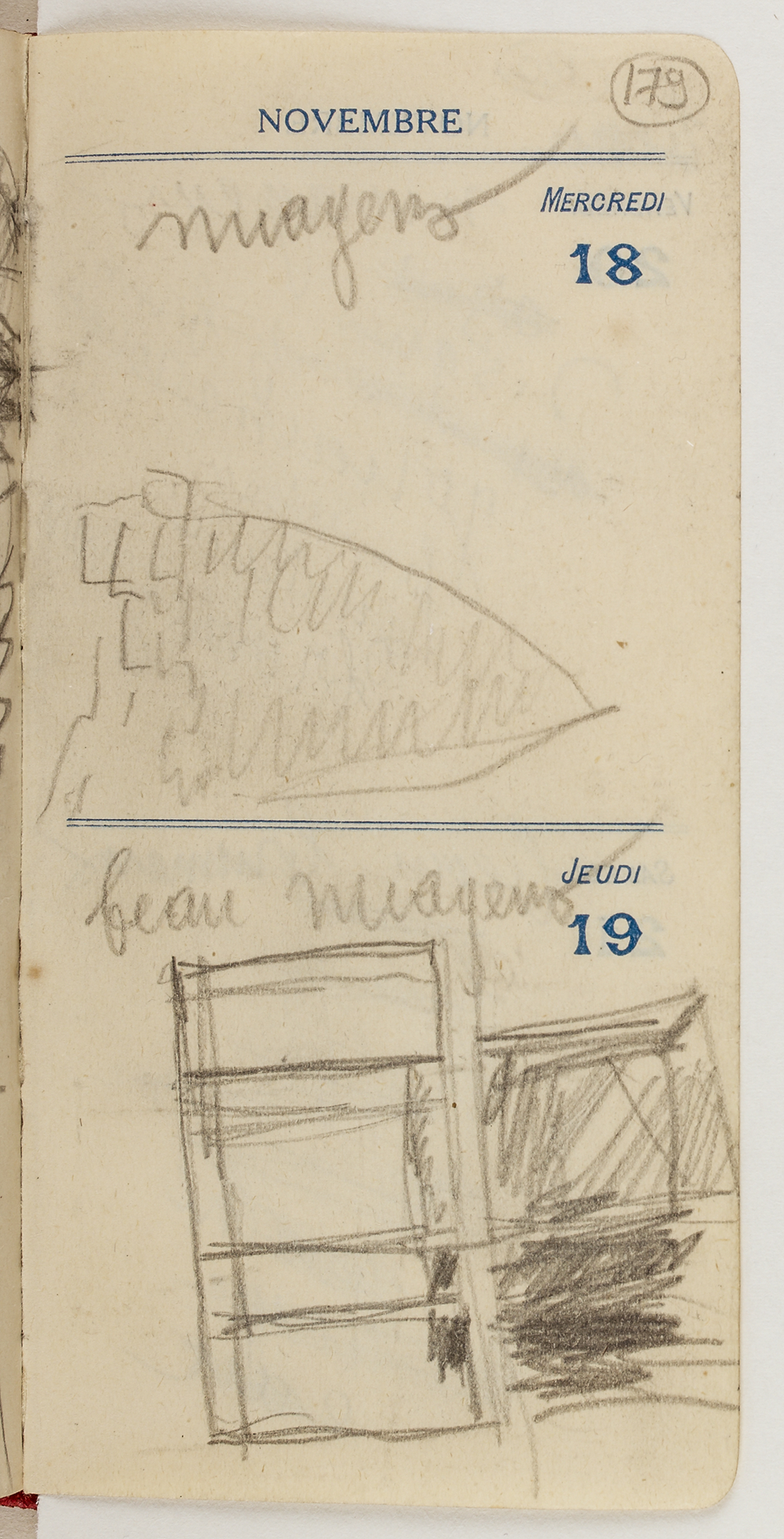

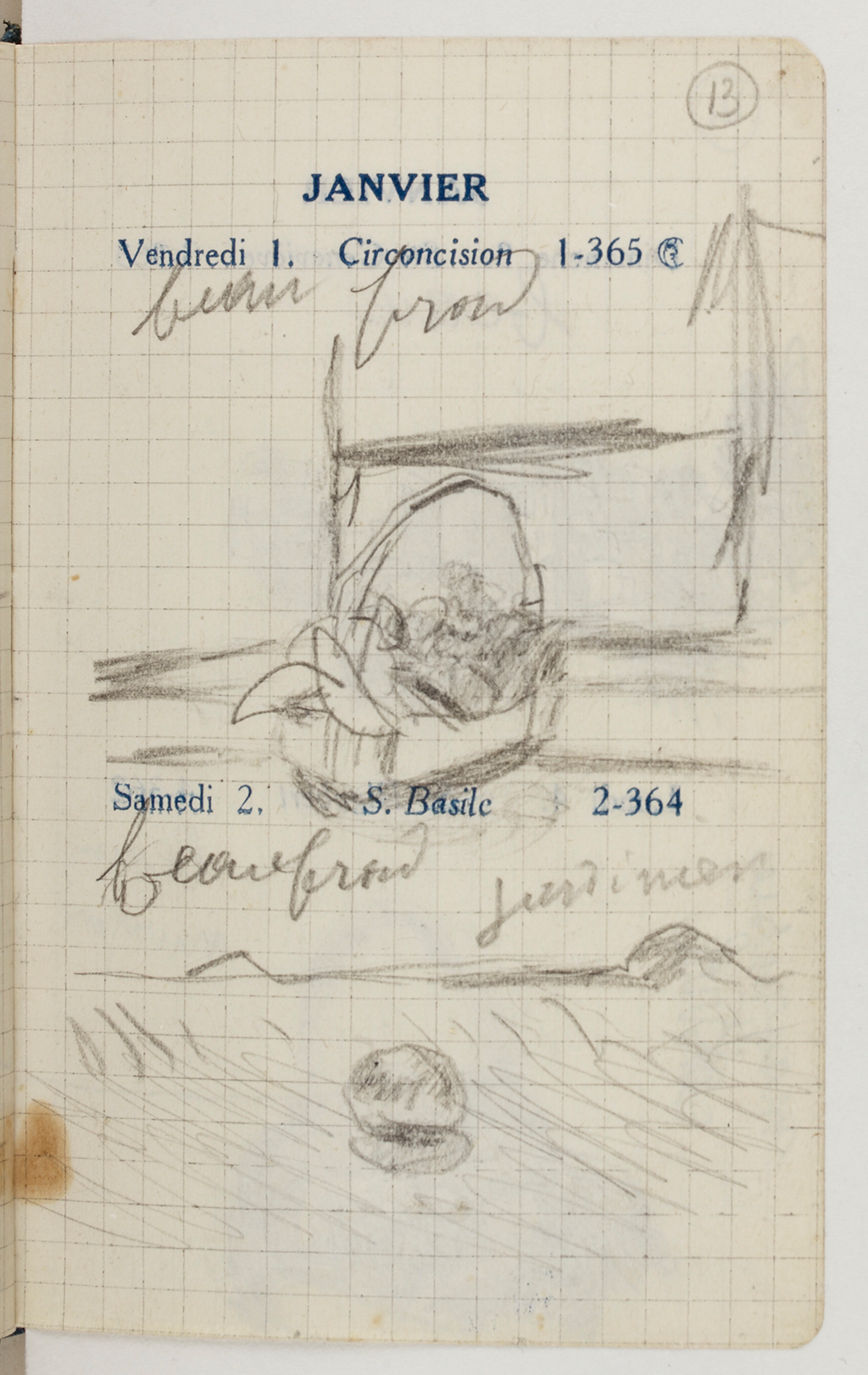

One might assume, given the personal subject and setting of the Kansas City work, that Bonnard executed it sur le motifsur le motif: French for “in front of the object.” A term used for sketching or painting from life., but this working method did not appeal to him. In an oft-quoted statement, Bonnard explained that “the presence of the object, the motif, is very cramping for the painter at the moment of painting” and could cause him “to lose the initial idea.”15Quoted in Michael Harrison and Judith Kimmelman, eds., Drawings by Bonnard, exh. cat. (London: Arts Council of Great Britain, 1984), 7. It was better, in his opinion, to make daily sketches of interesting objects or arrangements and then use those drawings as source material for paintings, often weeks or months after the fact. Bonnard also preferred to record these drawings in journals, rather than traditional sketchbooks, with the result that each one bears a precise date—a boon for art historians, since Bonnard rarely dated his paintings after 1900.16Whitfield and Elderfield, Bonnard, 53. The White Cupboard, which is signed but undated, has traditionally been assigned a date of 1931 or 1933. French art critic George Besson, who knew Bonnard well, dated the picture to 1933 in his monograph on the painter, probably because it was first exhibited in that year, and many scholars have followed his lead.17See George Besson, Bonnard (Paris: Éditions Braun, 1934), unpaginated; François-Joachim Beer, Pierre Bonnard (Marseille: Éditions Françaises d’Art, 1947), 103; Raymond Cogniat, Bonnard (Paris: Fernand Nathan, 1950), 38; and Bonnard, exh. cat. (Geneva: Galerie Krugier, 1969), 26. However, Jean and Henry Dauberville dated the work to 1931 in their catalogue raisonné of Bonnard’s oeuvre,18Jean and Henry Dauberville, Bonnard: Catalogue Raisonné de l’Œuvre Peint (Paris: Éditions Bernheim-Jeune, 1973), no. 1476, p. 3:375. and the painting’s stretcher, which conservation staff believe to be original, bears the cursive inscription “Placard Cannet 31” (Cupboard Cannet 31).19For more on the stretcher, see Scott Heffley, “Painting Report of Examination,” June 5, 2015, NAMA conservation file. The French term “cannet” can also refer to a cabinet or swing gate with open grillwork.

Fig. 3. Pierre Bonnard, untitled sketches from November 18–19, 1931, annotated with weather observations: “nuageux” (cloudy) and “beau nuageux” (nice cloudy), in Agenda 1931, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris. © 2023 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Fig. 3. Pierre Bonnard, untitled sketches from November 18–19, 1931, annotated with weather observations: “nuageux” (cloudy) and “beau nuageux” (nice cloudy), in Agenda 1931, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris. © 2023 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Fig. 4. Pierre Bonnard, untitled sketch from January 1–2, 1932, annotated with weather and property observations: “beau froid” (nice cold) and “beau froid jardinier” (nice cold gardener), in Agenda 1932, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris. © 2023 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Fig. 4. Pierre Bonnard, untitled sketch from January 1–2, 1932, annotated with weather and property observations: “beau froid” (nice cold) and “beau froid jardinier” (nice cold gardener), in Agenda 1932, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris. © 2023 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The tight framing of the Kansas City picture focuses attention on Marthe and her prosaic household chore. Although the activity of organizing tableware necessarily involves some degree of movement, the scene is characterized by an unnatural stillness; Marthe seems frozen in place. She forecloses any possibility of intimacy by turning away from viewers, either unaware of or determinedly ignoring our presence. This emotional disconnect must have appealed to Bonnard, because an individual seen from behind was one of his favorite figural conventions. More than seventy paintings in the Dauberville catalogue raisonné contain one or more people with their backs to the viewer.25I thank Pegeen Blank, volunteer, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, for her assistance with this tally. An early example is The Inspection (1890; private collection), which features a dozen French troops standing at attention. One row of soldiers faces the beholder, but a second row faces the opposite direction.26See Impressionist and Modern Art Evening Sale (New York: Christie’s, November 11, 2019), lot 10A, La Revue or L’Exercice, https://www.christies.com/lot/lot-pierre-bonnard-la-revue-ou-lexercice-6233778. In other pictures, we see women doing laundry27See Modern Day Auction (New York: Sotheby’s, November 17, 2021), lot 341, Femme étendant du linge, https://www.sothebys.com/en/buy/auction/2021/modern-day-auction/femme-etendant-du-linge. or examining their reflection in a mirror,28See Pierre Bonnard, Dame vor dem Spiegel, ca. 1905, oil on canvas, 20 5/8 x 14 7/8 in. (52.4 x 37.8 cm), Neue Pinakothek, Munich, inv. no. 8665, https://www.sammlung.pinakothek.de/en/artwork/Pdxz0XVGw5/pierre-bonnard/dame-vor-dem-spiegel. men shopping at a flea market,29See Art impressionniste et moderne (Paris: Christie’s, December 2, 2008), lot 11, Dans la rue (La Devanture), https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-5147251. city-dwellers strolling the streets of Paris30See Pierre Bonnard, Place Pigalle at Night, ca. 1905–1908, oil on panel, 22 5/8 x 26 15/16 in. (57.5 x 68.4 cm), Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT, 1955.23.1, https://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/9808.—all with their backs to us. Bonnard was particularly fond of portraying female figures from behind. Time and time again, Marthe and other women in his orbit avoid a confrontation with the outside world by physically spurning its gaze.31For two examples of Marthe posed in this manner, see Pierre Bonnard, The Yellow Shawl, ca. 1925, oil on canvas, 50 1/4 x 37 3/4 in. (127.6 x 95.9 cm), Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT, 2006.140.1, https://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/112769; and Pierre Bonnard, Coin de salle à manger au Cannet, ca. 1932, oil on canvas, 31 7/8 x 35 7/16 in. (81 x 90 cm), Musée d’Orsay, Paris, RF 1977 64, https://www.musee-orsay.fr/fr/oeuvres/coin-de-salle-manger-au-cannet-69573.

Although Bonnard often represented Marthe as aloof or withdrawn, critics failed to notice her detachment in The White Cupboard when the painting debuted at Galerie Bernheim-Jeune’s 1933 retrospective on the artist. Most reviewers interpreted Bonnard’s paintings as evocations of contented domesticity. Armand Dayot described the many dining room and washroom scenes in the exhibition as images of private life, “simple and everyday, but invariably happy.”32A[rmand] D[ayot], “Les expositions: Deux expositions de Pierre Bonnard,” L’Art et les artistes 26, no. 139 (July 1933): 351. Per Dayot, the pictures represented “la vie simple, quotidienne, mais immuablement heureuse.” This and subsequent translations by Brigid M. Boyle. Art historian Waldemar George went further. He construed Bonnard’s female figures not as representations of specific people but as emblems of French bourgeois womanhood:

The women whom Bonnard paints exude that nurturing calm and douceur de vivre [sweetness of life] so characteristic of French culture. The work and play of these young housewives consist of arranging flowers or decorating the table. Bonnard’s smiling heroines are the guardian angels of the households which they imbue with their real presence. Their homes are made in their image.33W[aldemar] G[eorge], “Défense et illustration de la bourgeoisie française: Bonnard et la douceur de vivre,” Formes, no. 33 (1933): 381. “Les femmes que peint Bonnard répandent autour d’elles ce calme bienfaisant et cette douceur de vivre qui sont les attributs de la culture française. Les travaux et les jeux de ces jeunes bourgeoises consistent à arranger les fleurs ou à garnir une table. Les souriantes héroïnes de Bonnard sont les anges-gardiens des foyers qu’elles imprègnent de leur présence réelle. Leurs intérieurs sont faits à leur image.”

George’s nationalistic reading is hard to reconcile with The White Cupboard, which he illustrated in his article. Marthe is the inverse of a “smiling heroine,” and the dining room at Le Bosquet is suffused with the artist’s spirit as much as his wife’s. It was Bonnard, after all, who oversaw the room’s renovation and selected its palette. Nevertheless, Dayot and George’s notion of Bonnard as someone who painted joyful scenes of daily life persisted for decades in the scholarship on the artist—Claude Roger-Marx famously dubbed Bonnard the “painter of happiness” in 195634Claude Roger-Marx, “Bonnard, peintre du bonheur,” Illustration, no. 23 (March 1956): 73–81.—and it is only recently that this idea has been debunked.

Today, Le Bosquet is recognized as a historic monument by the French government. Still in the hands of Bonnard’s descendants, who have scrupulously restored the home to its original state,35After Bonnard’s death, a lengthy legal battle ensued between his heirs and those of Marthe (see note 10), and Le Bosquet fell into a state of disrepair. It was not until 1968 that Jean-Jacques Terrasse, the artist’s great-nephew, purchased the property at auction and set about restoring it. See Terrasse, Bonnard at Le Cannet, 27–31. it stands as testament to an artist who produced some of his most inventive and psychologically complex paintings of domestic life there, including The White Cupboard.

Notes

-

For census data, see Claude Motte and Marie-Christine Vouloir, “Le Cannet” and “Cannes,” Des villages de Cassini aux communes d’aujourd’hui, Laboratoire de démographie historique, Centre national de la recherche scientifique, École des hautes études en sciences sociales, accessed November 8, 2022, http://cassini.ehess.fr/fr/html/fiche.php?select_resultat=6809 and http://cassini.ehess.fr/fr/html/fiche.php?select_resultat=6809. Le Cannet had 6,244 residents in 1926, whereas Cannes boasted 42,427.

-

This postcard bears the insignia of ND Phot., a Parisian publishing house founded as Neurdein Frères around 1885 and renamed ND Phot. in 1906. See “Neurdein Frères / Neurdein et Cie / ND Phot.,” Dumbarton Oaks Archives, accessed November 8, 2022, https://www.doaks.org/research/library-archives/dumbarton-oaks-archives/collections/ephemera/names/nd-phot.

-

See, for example, Pierre Bonnard, Landscape at Le Cannet, 1928, oil on canvas, 50 3/8 x 109 1/2 in. (128 x 278.2 cm), Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, TX, AP 2018.01, https://kimbellart.org/collection/ap-201801.

-

Michel Terrasse, Bonnard at Le Cannet, trans. Sebastien Wormell (New York: Pantheon Books, 1988), 121.

-

The timing of and motivation for Marthe’s name change are unclear. Tradition has it that Marthe introduced herself to Bonnard as “Marthe de Méligny” when they first met, but Lucy Whelan casts doubt on this long-held assumption; see Lucy Whelan, “New Light on Pierre Bonnard’s Wife and Model Marthe,” Burlington Magazine 162, no. 1406 (May 2020): 417–18. According to Marthe’s great-niece Pierrette Vernon, Marthe’s adopted surname probably derives from a village in the Cher department called Méligny, close to where Marthe grew up. See Sarah Whitfield, “Fragments of an Identical World,” in Sarah Whitfield and John Elderfield, Bonnard, exh. cat. (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1998), 30n41. Due to this complex history, scholars refer to Bonnard’s wife simply as “Marthe” in the literature on him; I have followed their lead.

-

See, for example, William D. Montalbano, “A Brush With, or Without, Greatness?” Los Angeles Times (March 21, 1998): https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1998-mar-21-ca-31063-story.html; and Alastair Sooke, “In the Bath with Mrs. Bonnard: How the Painter’s Difficult Marriage Inspired His Art,” Telegraph (January 20, 2019): https:www.telegraph.co.uk/art/artists/bath-mrs-bonnard-painters-difficult-marriage-inspired-spellbinding/.

-

Whelan, “New Light,” 413.

-

Whitfield’s statement that “at the age of twenty-six, Bonnard decided to make his life with Marthe” is typical of the scholarship on the artist. See Whitfield, “Fragments of an Identical World,” 15.

-

Whelan, “New Light,” 414–16, 418.

-

Bonnard supposedly had affairs with two of his models, Lucienne Dupuy de Fenelle and Renée Montchaty, while in a relationship with Marthe; see Véronique Serrano, “He Who Sings is Not Always Happy,” in Matthew Gale, ed., The C C Land Exhibition: Pierre Bonnard; The Colour of Memory, exh. cat. (London: Tate, 2019), 35. He also forged Marthe’s will in order to retain full possession of their shared estate, leading to a decades-long inheritance struggle after his own death; see Sarah Whitfield, “A Question of Belonging,” in Pierre Bonnard: The Work of Art; Suspending Time (Paris: Paris-Musées, 2006), 65.

-

Marthe suffered from respiratory problems, possibly due to the long hours she worked as a fleuriste. The adhesive pastes and gases used to make artificial flowers were known to cause health issues. See Whelan, “New Light,” 413, 417; Octave Uzanne, Parisiennes de ce temps: En leurs divers milieux, états et conditions (Paris: Mercure de France, 1910), 159–60; and Mary Van Kleeck, Artificial Flower Makers (New York: Survey Associates, 1913), 153.

-

Quoted in Jacqueline Munck, “‘The Cat Drank All the Milk!’: Bonnard’s Continuous Present,” in Dita Amory, ed., Pierre Bonnard: The Late Still Lifes and Interiors, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009), 63. Similarly, in 1931 Bonnard rescinded an invitation to George Besson to visit him at Le Bosquet due to Marthe’s mental health. See Chantal Duverget, George Besson, 1882–1971: Itinéraire d’un passeur d’art (Paris: Somogy éditions d’art, 2012), 98–100. These incidents notwithstanding, some Bonnard experts believe reports of Marthe’s antisocial behavior to be overblown. Whelan argues that Marthe’s reputation as a recluse derives largely from the inheritance dispute between Bonnard’s descendants and Marthe’s heirs, in which the former presented Marthe as “a strange and secretive individual”—a legal strategy that ultimately helped win their case. See Whelan, “New Light,” 417.

-

When Bonnard informed Henri Matisse (1869–1954) of Marthe’s passing, his heavy emotions were evident: “You can imagine my grief and my solitude, filled with bitterness and worry about the life I may be leading from now on.” Quoted in Antoine Terrasse, ed., Bonnard/Matisse: Letters between Friends, 1925–1946, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1992), 101.

-

As Bonnard’s great-nephew observed, Bonnard recorded Marthe’s likeness in drawings, paintings, engravings, photographs, and even sculpture. See Antoine Terrasse, “A World Devoted to the Feminine,” in Guy Cogeval and Isabelle Cahn, Pierre Bonnard: Painting Arcadia, exh. cat. (San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 2016), 206.

-

Quoted in Michael Harrison and Judith Kimmelman, eds., Drawings by Bonnard, exh. cat. (London: Arts Council of Great Britain, 1984), 7.

-

Whitfield and Elderfield, Bonnard, 53.

-

See George Besson, Bonnard (Paris: Éditions Braun, 1934), unpaginated; François-Joachim Beer, Pierre Bonnard (Marseille: Éditions Françaises d’Art, 1947), 103; Raymond Cogniat, Bonnard (Paris: Fernand Nathan, 1950), 38; and Bonnard, exh. cat. (Geneva: Galerie Krugier, 1969), 26.

-

Jean and Henry Dauberville, Bonnard: Catalogue Raisonné de l’Œuvre Peint (Paris: Éditions Bernheim-Jeune, 1973), no. 1476, p. 3:375.

-

For more on the stretcher, see Scott Heffley, “Painting Report of Examination,” June 5, 2015, NAMA conservation file. The French term “cannet” can also refer to a cabinet or swing gate with open grillwork.

-

In the latter, the woman is slightly hunched, and her head is turned away from the cabinet, whereas in The White Cupboard Marthe stands erect and faces the shelves. Nevertheless, the drawing is compositionally similar to the Nelson-Atkins work. See Pierre Bonnard, entries for January 4 and December 16–17, 1932, Agenda 1932, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris. I am grateful to Danielle Hampton Cullen, project assistant, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, for identifying these and other sketches.

-

Doric pilasters replaced the original partition. See “The Bosquet: The House of Pierre Bonnard,” virtual visit, Le Musée Bonnard, accessed March 14, 2023, http://www.museebonnard.fr/index.php/fr/ressources/pedagogiques/133-visites-virtuelles-documentaires.

-

Terrasse, Bonnard at Le Cannet, 13–14.

-

For Bonnard’s contrasting palette in northern and southern locales, see Nicholas Watkins, Bonnard (London: Phaidon, 1994), 116–63; and Nicholas Watkins, Interpreting Bonnard: Color and Light, exh. cat. (New York: Stewart, Tabori, and Chang, 1998), 63.

-

Had Bonnard widened his viewing angle still further, one would have seen a framed lithograph of Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s (1841–1919) Pinning the Hat hanging kitty-corner from the cupboard, evidence of the two artists’ longstanding friendship. The Renoir print is visible in period photographs of the dining room, such as Henri Cartier-Bresson’s Bonnard at Home, Le Cannet, 1944, gelatin silver print, 7 1/16 x 10 9/16 in. (17.9 x 26.9 cm), Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson, Paris, reproduced in Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 149.

-

I thank Pegeen Blank, volunteer, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, for her assistance with this tally.

-

See Impressionist and Modern Art Evening Sale (New York: Christie’s, November 11, 2019), lot 10A, La Revue or L’Exercice, https://www.christies.com/lot/lot-pierre-bonnard-la-revue-ou-lexercice-6233778.

-

See Modern Day Auction (New York: Sotheby’s, November 17, 2021), lot 341, Femme étendant du linge, https://www.sothebys.com/en/buy/auction/2021/ modern-day-auction/femme-etendant-du-linge.

-

See Pierre Bonnard, Dame vor dem Spiegel, ca. 1905, oil on canvas, 20 5/8 x 14 7/8 in. (52.4 x 37.8 cm), Neue Pinakothek, Munich, inv. no. 8665, https://www.sammlung.pinakothek.de/en/artwork/ Pdxz0XVGw5/pierre-bonnard/dame-vor-dem-spiegel.

-

See Art impressionniste et moderne (Paris: Christie’s, December 2, 2008), lot 11, Dans la rue (La Devanture), https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-5147251.

-

See Pierre Bonnard, Place Pigalle at Night, ca. 1905–1908, oil on panel, 22 5/8 x 26 15/16 in. (57.5 x 68.4 cm), Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT, 1955.23.1, https://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/9808.

-

For two examples of Marthe posed in this manner, see Pierre Bonnard, The Yellow Shawl, ca. 1925, oil on canvas, 50 1/4 x 37 3/4 in. (127.6 x 95.9 cm), Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT, 2006.140.1, https://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/112769; and Pierre Bonnard, Coin de salle à manger au Cannet, ca. 1932, oil on canvas, 31 7/8 x 35 7/16 in. (81 x 90 cm), Musée d’Orsay, Paris, RF 1977 64, https://www.musee-orsay.fr/fr/oeuvres/coin-de-salle-manger-au-cannet-69573.

-

A[rmand] D[ayot], “Les expositions: Deux expositions de Pierre Bonnard,” L’Art et les artistes 26, no. 139 (July 1933): 351. Per Dayot, the pictures represented “la vie simple, quotidienne, mais immuablement heureuse.” This and subsequent translations by Brigid M. Boyle.

-

W[aldemar] G[eorge], “Défense et illustration de la bourgeoisie française: Bonnard et la douceur de vivre,” Formes, no. 33 (1933): 381. “Les femmes que peint Bonnard répandent autour d’elles ce calme bienfaisant et cette douceur de vivre qui sont les attributs de la culture française. Les travaux et les jeux de ces jeunes bourgeoises consistent à arranger les fleurs ou à garnir une table. Les souriantes héroïnes de Bonnard sont les anges-gardiens des foyers qu’elles imprègnent de leur présence réelle. Leurs intérieurs sont faits à leur image.”

-

Claude Roger-Marx, “Bonnard, peintre du bonheur,” Illustration, no. 23 (March 1956): 73–81.

-

After Bonnard’s death, a lengthy legal battle ensued between his heirs and those of Marthe (see note 10), and Le Bosquet fell into a state of disrepair. It was not until 1968 that Jean-Jacques Terrasse, the artist’s great-nephew, purchased the property at auction and set about restoring it. See Terrasse, Bonnard at Le Cannet, 27–31.

Technical Entry

Technical entry forthcoming.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Pierre Bonnard, The White Cupboard, 1931–1932,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.706.2088.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Pierre Bonnard, The White Cupboard, 1931–1932,” documentation entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.706.2088.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Pierre Bonnard, The White Cupboard, 1931–1932,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.706.2088.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Pierre Bonnard, The White Cupboard, 1931–1932,” documentation entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.706.2088.

Purchased from the artist by Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, Paris, possibly stock no. 25375, Paris, possibly by June 15, 1933 [1];

Charles-Henri Pomaret (1897–1984) and Marie-Paule Fontenelle-Pomaret (1889–1975), Paris and Aix-en-Provence, by June 1937–1973 [2];

Purchased from the Pomarets by Wildenstein and Co., New York, stock no. 667, November 28, 1973–1979 [3];

Purchased from Wildenstein by Marion (née Helzberg, 1931–2013) and Henry (1922–2019) Bloch, Shawnee Mission, KS, April 30, 1979–June 15, 2015;

Their gift to the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 2015.

NOTES:

[1] Bonnard was under contract with Galerie Bernheim-Jeune from 1904 to 1940. Galerie Bernheim-Jeune may have purchased the painting as early as June 15, 1933, when an exhibition featuring it opened at Galerie Bernheim-Jeune. See Exposition Pierre Bonnard, exh. cat. (Paris: Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, 1933), 4.

A set of six-digit numbers on the verso, “25375,” is similar to Galerie Bernheim-Jeune stock numbers. Another painting in the collection of the Nelson-Atkins also has a Bernheim-Jeune stock number; Vincent van Gogh 37-1 was stock number “26801” and was owned by Galerie Bernheim-Jeune by December 1935. Since the Bonnard stock number 25375 precedes 26801, it was probably in the inventory of Galerie Bernheim-Jeune before 1935.

[2] Charles Pomaret was minister of labor in France from 1938 to 1940, and his wife, Marie-Paule Fontenelle-Pomaret, was the director of the art periodical La Renaissance and an avid art collector.

According to the 1973 catalogue raisonné, the painting was in a private collection in Aix-en-Provence. See Jean and Henry Dauberville, Bonnard: Catalogue Raisonne de l’Œuvre Peint, 1888–1905 (Paris: Éditions J et H. Bernheim-Jeune, 1973), no. 1476, p. 3:375. The private collectors are the Pomarets, who moved from Paris to Aix-en-Provence by 1946. See email from Joseph Baillio, Wildenstein, to MacKenzie Mallon, NAMA, May 4, 2015, NAMA curatorial files.

[3] For date of purchase, see email from Joseph Baillio, Wildenstein, to MacKenzie Mallon, NAMA, May 4, 2015, NAMA curatorial files.

Preparatory Works

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Pierre Bonnard, The White Cupboard, 1931–1932,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.706.2088.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Pierre Bonnard, The White Cupboard, 1931–1932,” documentation entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.706.2088.

Pierre Bonnard, untitled sketch (sketch of a cupboard), page of Bonnard’s Agenda 1931, dated November 17, 1931, pencil on paper, 5 1/8 x 3 1/8 in. (13 x 8 cm), Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, RESERVE 4-EF-500 (B,5), p. 178.

Pierre Bonnard, untitled sketch (sketch of a cupboard), page of Bonnard’s Agenda 1931, dated November 19, 1931, pencil on paper, 5 1/8 x 3 1/8 in. (13 x 8 cm), Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, RESERVE 4-EF-500 (B,5), p. 179.

Pierre Bonnard, untitled sketch (sketch of a cupboard and basket of fruit), pages of Bonnard’s Agenda 1931, dated December 12–13, 1931, pencil on paper, 5 1/8 x 3 1/8 in. (13 x 8 cm), Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, RESERVE 4-EF-500 (B,5), p. 191.

Pierre Bonnard, untitled sketch (sketch of a cupboard, basket of fruit, tablecloth, and fruit), pages of Bonnard’s Agenda 1932, dated January 1–2, 1932, pencil on paper, 5 1/8 x 3 1/8 in. (13 x 8 cm), Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, RESERVE 4-EF-500 (B,6), p. 13.

Pierre Bonnard, untitled sketch (sketch of a basket of fruit), page of Bonnard’s Agenda 1932, dated January 4, 1932, pencil on paper, 5 1/8 x 3 1/8 in. (13 x 8 cm), Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, RESERVE 4-EF-500 (B,6), p. 14.

Pierre Bonnard, untitled sketch (sketch of a cupboard and woman, probably Marthe), pages of Bonnard’s Agenda 1932, dated December 16–17, 1932, pencil on paper, 5 1/8 x 3 1/8 in. (13 x 8 cm), Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, RESERVE 4-EF-500 (B,6), p. 189.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Pierre Bonnard, The White Cupboard, 1931–1932,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.706.2088.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Pierre Bonnard, The White Cupboard, 1931–1932,” documentation entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.706.2088.

Pierre Bonnard, The Dining Room, 1927, oil on canvas, 29 7/8 x 29 1/2 in. (76 x 75 cm), illustrated in Jean and Henry Dauberville, Bonnard: Catalogue raisonné de l’œuvre peint, 1920–1939 (Paris: Éditions Bernheim-Jeune, 1973), no. 1212, p. 3:178, (repro.).

Pierre Bonnard, Corner of the Dining Room at Le Cannet, 1932, oil on canvas, 31 7/8 x 35 1/2 in. (81 x 90 cm), Centre Pompidou, Paris, RF 1977 64.

Pierre Bonnard, Marthe in the Dining Room, 1933, oil on canvas, 43 1/4 x 23 1/4 in. (111 x 59 cm), Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lyon, France.

Pierre Bonnard, Interior, The Dining Room, 1943, oil on canvas, 21 5/8 x 17 5/16 in. (55 x 44 cm), illustrated in Jean and Henry Dauberville, Bonnard: Catalogue raisonné de l’œuvre peint, 1940–1947 (Paris: Éditions Bernheim-Jeune, 1973), no. 1635, p. 4:64, (repro.).

Pierre Bonnard, The Dining Room, ca. 1940–1947, oil on canvas, 33 1/8 x 39 3/8 in. (84.1 x 100 cm), Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, 2006.46.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Pierre Bonnard, The White Cupboard, 1931–1932,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.706.2088.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Pierre Bonnard, The White Cupboard, 1931–1932,” documentation entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.706.2088.

Exposition Pierre Bonnard, Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, Paris, June 15–23, 1933, no. 15, as Le Placard.

Les Maitres de l’Art Indépendant, 1895–1937, Petit Palais, Paris, June–October 1937, no. 18, as Le buffet.

Bonnard, Musée des Ponchettes, Nice, August–September 1955, no. 37, as L’armoire blanche.

Douze jeunes peintres autour de Bonnard, Palais de la Méditerranée, Nice, February 5–March 14, 1965, no. 9, as La Femme à l’armoire.

Bonnard, Galerie Krugier, Geneva, June 1969, no. 24, as L’armoire blanche.

The Bloch Collection, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, June–August 1982, no cat.

Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, June 9–September 9, 2007, no. 29, as The White Cupboard (L’armoire blanche).

Magnificent Gifts for the 75th, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, February 11–April 4, 2010, no cat.

Bonnard’s Worlds, Kimbell Art Museum, November 5, 2023–January 28, 2024; The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC, March 2–June 2, 2024, no. 38, as The White Cupboard.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Pierre Bonnard, The White Cupboard, 1931–1932,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.706.2088.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Pierre Bonnard, The White Cupboard, 1931–1932,” documentation entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.706.2088.

Jacques Guenne, “Bonnard ou le bonheur de vivre,” L’Art Vivant, no. 176 (September 1933): 374–75, (repro.), as Le Placard.

Exposition Pierre Bonnard, exh. cat. (Paris: Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, 1933), (repro).

W[aldemar] G[eorge], “Défense et Illustration de la Bourgeoisie Française: Bonnard et la Douceur de Vivre,” Formes, no. 33 (1933): (repro.), as Le Placard [repr., in Formes: An International Review of Plastic Art, 1929–1933, vol. 6, No. 28–33, 1932–1933 (New York: Arno, 1971), (repro.), as Le Placard].

George Besson, Bonnard (Paris: Les Éditions Braun, 1934), unpaginated, (repro.), as L’armoire blanche.

Waldemar George, “L’art français et l’esprit de suite,” La Renaissance, nos. 3–4 (March–April 1937): 8, (repro.), as Le Placard.

Les maitres de l’art indépendant, 1895–1937, exh. cat. (Paris: Éditions Arts et Métiers Graphiques, 1937), 60, (repro.), as Le buffet.

“Seven Paintings by Pierre Bonnard,” Coronet 3, no. 4 (February 1, 1938): 23, (repro.), as The Cupboard.

Pierre Loeb, “Pierre Bonnard, peintre français,” L’Age Nouveau, no. 19 (March 1947): unpaginated, (repro.).

François-Joachim Beer, Pierre Bonnard (Marseille: Éditions Françaises d’Art, 1947), 103, (repro.), as L’armoire blanche.

Raymond Cogniat, Bonnard (Paris: Fernand Nathan, 1950), 38, (repro.), as L’armoire blanche.

Bonnard, exh. cat. (Nice: Musée des Ponchettes, 1955), 31, as L’armoire blanche.

Claude Roger -Marx, “Bonnard, peintre du Bonheur,” Illustration, no. 23 (March 1956): 74–75, (repro.), as L’armoire blanche.

Gerard Jarlot, “L’Affaire Bonnard,” Elle, no. 694 (April 3, 1959): 89, (repro.), as L’armoire blanche.

Douze jeunes peintres autour de Bonnard, exh. cat. (New York: Wildenstein, 1965), unpaginated, as La Femme à l’armoire.

Bonnard, exh. cat. (Geneva: Galerie Krugier, 1969), 19, 26, (repro.), as L’armoire blanche.

Jean and Henry Dauberville, Bonnard: Catalogue Raisonné de l’Œuvre Peint, 1920–1939 (Paris: Éditions Bernheim-Jeune, 1973), no. 1476, pp. 3:374–75, (repro.) as Le placard ou L’armoire blanche.

“The Bloch Collection,” Gallery Events (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) (June–August 1982): unpaginated.

Sasha M. Newman, ed., Bonnard: The Late Paintings, exh. cat. (New York: Thames and Hudson, 1984), 259, as L’Armoire blanche.

Donald Hoffmann, “Eileen Jagoda’s lyrical collages suffer from formless tenor,” Kansas City Star 105, no. 140 (March 3, 1985): 6F.

Michel Terrasse, Bonnard at Le Cannet (Paris: Herscher, 1987), 124, as Le placard ou l’armoire blanche.

Michel Terrasse, Bonnard: du dessin au tableau (Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1996), 214–15, (repro.), as Le Placard blanc.

Rebecca Dimling Cochran and Bobbie Leigh, “100 Top Collectors who have made a difference,” Art and Antiques (March 2006): 90.

Bobbie Leigh, “Magnificent Obsession,” Art and Antiques 29, no. 6 (June 2006): 65, (repro.), as The White Cupboard.

Alice Thorson, “A final countdown—A rare showing of Impressionist paintings from the private collection of Henry and Marion Bloch is one of the inaugural exhibitions at the 165,000-square-foot glass-and-steel structure,” Kansas City Star (June 29, 2006): B1.

“Inaugural Exhibitions Celebrate Kansas City,” Member Magazine (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (Fall 2006): 3.

Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 10, 12, 18, 146–49, 162, (repro.), as The White Cupboard (L’armoire blanche).

Alice Thorson, “A Tiny Renoir Began an Impressive Obsession,” Kansas City Star 127, no. 269 (June 3, 2007): E4, as The White Cupboard.

“Lasting Impressions: A Tribute to Marion and Henry Bloch,” Member Magazine (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (Fall 2007): 10–11, (repro.).

Steve Paul, “Pretty Pictures: Marion and Henry Bloch’s Collection of Superb Impressionist Masters,” Panache 4, no. 3 (Fall 2007): 20.

“A 75th Anniversary Celebrated with Gifts of 400 Works of Art,” Art Tattler International (February 2008): unpaginated, (repro.), as The White Cupboard (L’armoire blanche).

Alice Thorson, “Museum to Get 29 Impressionist Works from the Bloch Collection,” Kansas City Star (February 5, 2010): A1, as White Cupboard.

Carol Vogel, “Inside Art: Kansas City Riches,” New York Times 159, no. 54,942 (February 5, 2010): C26.

Alice Thorson, “Bloch: Nelson to receive impressionism collection,” Kansas City Star (February 7, 2010): G1, G2, The White Cupboard.

Alice Thorson, “Marc Wilson: The Nelson Years,” Kansas City Star (April 25, 2010): F2, (repro.), as L’armorie Blanche.

Thomas M. Bloch, Many Happy Returns: The Story of Henry Bloch, America’s Tax Man (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, 2011), 174–75, (repro.), as The White Cupboard.

Diane Stafford, “Bloch Gift to Go for Nelson Upgrade,” Kansas City Star 135, no. 203 (April 8, 2015): A8.

“Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Officially Accessions Bloch Impressionist Masterpieces,” Artdaily.org (July 25, 2015): http://artdaily.com/news/80246/Nelson-Atkins-Museum-of-Art-officially-accessions-Bloch-Impressionist-masterpieces#.V6oGwlKFO9I.

Julie Paulais, “Le Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art reçoit des tableaux impressionnistes en échange de leurs répliques, ” Le Journal des arts (July 30, 2015): http://www.lejournaldesarts.fr/site/archives/docs_article/129801/le-nelson-atkins-museum-of-art-recoit-des-tableaux-impressionnistes-en-echange-de-leurs-repliques.php.

Josh Niland, “The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Acquires a Renowned Collection of Impressionist and Postimpressionist Art,” architecturaldigest.com (August 6, 2015): https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/nelson-atkins-museum-accessions-bloch-art-collection.

Nina Siegal, “Upon Closer Review, Credit Goes to Bosch,” New York Times 165, no. 57130 (February 2, 2016): C5.

“Nelson-Atkins to unveil renovated Bloch Galleries of European Art in winter 2017,” Artdaily.org (July 20, 2016): http://artdaily.com/news/88852/Nelson-Atkins-to-unveil-renovated-Bloch-Galleries-of-European-Art-in-winter-2017-#.W-NDepNKhaQ.

“Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art celebrates generosity of Henry Bloch with new acquisition,” Artdaily.org (October 18, 2016): http://artdaily.com/news/90923/Nelson-Atkins-Museum-of-Art-celebrates-generosity-of-Henry-Bloch-with-new-acquisition#.W-NDv5NKhaQ.

Catherine Futter et al., Bloch Galleries: Highlights from the Collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2016), 121, (repro.), as The White Cupboard.

Kelly Crow, “Museum Rewards Donor with Fake Art to Hang at Home,” Wall Street Journal (January 25, 2017): https://www.wsj.com/articles/museum-rewards-donor-with-fake-art-to-hang-at-home-1485370768, (repro.), as The White Cupboard.

David Frese, “Bloch savors paintings in redone galleries,” Kansas City Star 137 (February 25, 2017): 1A.

Albert Hect, “Henry Bloch’s Masterpieces Collection to Go on Display at Nelson-Atkins Museum,” Jewish Business News (February 26, 2017): http://jewishbusinessnews.com/2017/02/26/henry-bloch-masterpieces-collection/.

David Frese, “Inside the Bloch Galleries: An interactive experience,” Kansas City Star 137, no. 169 (March 5, 2017), 1D, 4D, (repro.), as White Cupboard.

“Editorial: Thank you, Henry and Marion Bloch,” Kansas City Star (March 7, 2017): http://www.kansascity.com/opinion/editorials/ article137040948.html, [repr., in “Thank you, Henry and Marion Bloch,” Kansas City Star 137, no. 172 (March 8, 2017): 16A].

Hampton Stevens, “(Not Actually) 12 Things To Do During The Big 12 Tournament,” Flatland: KCPT’s Digital Magazine (March 9, 2017): http://www.flatlandkc.org/arts-culture/sports/not-actually-12-big-12-tournament/.

Laura Spencer, “The Nelson-Atkins’ Bloch Galleries feature Old Masterworks and New Technology,” KCUR (March 10, 2017): http://kcur.org/post/nelson-atkins-bloch-galleries-feature-old-masterworks-and-new-technology#stream/0, (repro.).

Victoria Stapley–Brown, “Nelson-Atkins Museum’s new European art galleries come with a ‘love story’,” Art Newspaper (March 10, 2017): http://theartnewspaper.com/news/museums/nelson-atkins-museum-s-new-european-art-galleries-come-with-a-love-story/.

Harry Bellet, “Don du ciel pour le Musée Nelson-Atkins,” Le Monde (March 13, 2017): http://www.lemonde.fr/arts/article/2017/03/13/don-du-ciel-pour-le-musee-nelson-atkins_5093543_1655012.html, as White wardrobe.

Menachem Wecker, “Jewish Philanthropist Establishes Kansas City as Cultural Mecca,” Forward (March 14, 2017): http://forward.com/culture/365264/jewish-philanthropist-establishes-kansas-city-as-cultural-mecca/, [repr., in Menachem Wecker, “Kansas City Collection Is A Chip Off the Old Bloch,” Forward (March 17, 2017): 20-22].

Juliet Helmke, “The Bloch Collection Takes up Residence in Kansas City’s Nelson-Atkins Museum,” BoulinArtInfo International (March 15, 2017): http://www.blouinartinfo.com/news/story/2005267/the-bloch-collection-takes-up-residence-in-kansascitys.

Erich Hatala Matthes, “Digital replicas are not soulless—they help us engage with art,” Apollo (March 23, 2017): https://www.apollo-magazine.com/digital-replicas-3d-printing-original-artworks/.

Louise Nicholson, “How Kansas City got its magnificent museum,” Apollo (April 7, 2017): https://www.apollo-magazine.com/how-kansas-city-got-its-magnificent-museum/.

Lilly Wei, “Julián Zugazagoitia: ‘Museums should generate interest and open a door that leads to further learning,’” Studio International (August 21, 2017): http://studiointernational.com/index.php/julian-zugazagoitia-director-nelson-atkins-museum-of-art-kansas-city-interview.

Robert D. Hershey Jr., “Henry Bloch, H&R Block’s cofounder, dies at 96,” Boston Globe (April 23, 2019): https://www3.bostonglobe.com/metro/obituaries/2019/04/23/henry-bloch-block-cofounder/?arc404=true.

Robert D. Hershey Jr., “Henry W. Bloch, Tax-Preparation Pioneer (and Pitchman), Is Dead at 96,” New York Times (April 23, 2019): https://www3.bostonglobe.com/metro/obituaries/2019/04/23/henry-bloch-block-cofounder/?arc404=true.

Claire Selvin, “Henry Wollman Bloch, Collector and Prominent Benefactor of Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Is Dead at 96,” ArtNews (April 23, 2019): http://www.artnews.com/2019/04/23/henry-bloch-dead-96/.

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “Henry Bloch, co-founder of H&R Block, dies at 96,” Kansas City Star 139, no. 219 (April 24, 2019): 1A.

“Henry Wollman Bloch (1922–2019),” Art Forum (April 24, 2019): https://www.artforum.com/news/henry-wollman-bloch-1922-2019-79547.

Frank Morris, “Henry Bloch, Co-Founder Of H&R Block, Dies At 96,” npr.org (April 24, 2019): https://www.npr.org/2019/04/24/716641448/henry-bloch-co-founder-of-h-r-block-dies-at-96.

Ignacio Villarreal, “Nelson-Atkins mourns loss of Henry Bloch,” ArtDaily.org (April 24, 2019): http://artdaily.com/news/113035/Nelson-Atkins-mourns-loss-of-Henry-Bloch#.XMB76qR7laQ.

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “H&R Bloch co-founder, philanthropist Bloch dies,” Cass County Democrat Missourian 140, no. 29 (April 26, 2019): 1A

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “KC businessman and philanthropist Henry Bloch dies,” Lee’s Summit Journal 132, no. 79 (April 26, 2019): 3A.

Luke Nozicka, “Family and friends remember Henry Bloch of H&R Block,” Kansas City Star 139, no. 225 (April 30, 2019): 4A [repr., Kansas City Star 139, no. 228 (May 3, 2019): 3A].

Eric Adler, “Sold for $3.25 million, Bloch’s home in Mission Hills may be torn down,” Kansas City Star 141, no. 90 (December 16, 2020): 2A.

Guy-Patrice and Floriane Dauberville, Bonnard: 2e Supplément, Catalogue Raisonné de l’Œuvre Peint (Paris: Editions G-P. F. Dauberville and Archives Bernheim-Jeune, 2021), 140, (repro).

George T. M. Shackelford, Bonnard’s Worlds, exh. cat. (Fort Worth, TX: Kimbell Art Museum, 2023), 86, 88, 169–72, 251, (repro.), as The White Cupboard.