Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “Armand Guillaumin, Moret-sur-Loing, Evening Effect, No. 2, ca. 1902,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.622.5407.

MLA:

Marcereau DeGalan, Aimee. “Armand Guillaumin, Moret-sur-Loing, Evening Effect, No. 2, ca. 1902,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.622.5407.

Moret-sur-Loing, a picturesque town on the Loing River about forty miles southeast of Paris, is celebrated for its medieval architecture, stone mills, and avenues of poplars lining the riverbanks. Its scenic charm attracted numerous artists, most famously Alfred Sisley (English, born Paris, 1839–1899), who immortalized the Gothic church of Notre-Dame and the bustling river scenes in a series of works from 1889 until his death in 1899. His prolific depictions of these sites from various vantage points inspired other painters who followed, including Camille Pissarro (1830–1903) and Claude Monet (1840–1926). Like Sisley and Monet, Armand Guillaumin embraced the concept of serial compositions, exploring a single motif through the changing effects of light and weather.

Guillaumin’s Moret-sur-Loing, Evening Effect, No. 2 pictures the view from the east bank of the Loing, looking south or upstream toward the stone-arch bridge known as the Pont de Moret. It is highly likely, given the canvas’s relatively modest scale and the artist’s preference for working en plein airen plein air (adjective: plein-air): French for “outdoors.” The term is used to describe the act of painting quickly outside rather than in a studio., that he realized the composition directly in front of his subject. Near the center of the bridge stands the Provencher mill,1The mill was reduced to its foundation and waterwheel following World War II; see Sylvie Patin’s catalogue entry for “The Provencher Watermill at Moret,” in Alfred Sisley, ed. MaryAnne Stevens (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 1992), 204, no. 55. consisting of the pair of large buildings seen at center left in the composition. The bridge enters the once-walled town at the Porte de Bourgogne, the tall tower with a poplar tree in front of it, at right. The belfry of Notre-Dame is visible at the far right of the composition.

Fig. 1. Armand Guillaumin, The Old Samois, ca. 1902, oil on canvas, 11 x 15 3/4 in. (28 x 40 cm), private collection, Lille

Fig. 1. Armand Guillaumin, The Old Samois, ca. 1902, oil on canvas, 11 x 15 3/4 in. (28 x 40 cm), private collection, Lille

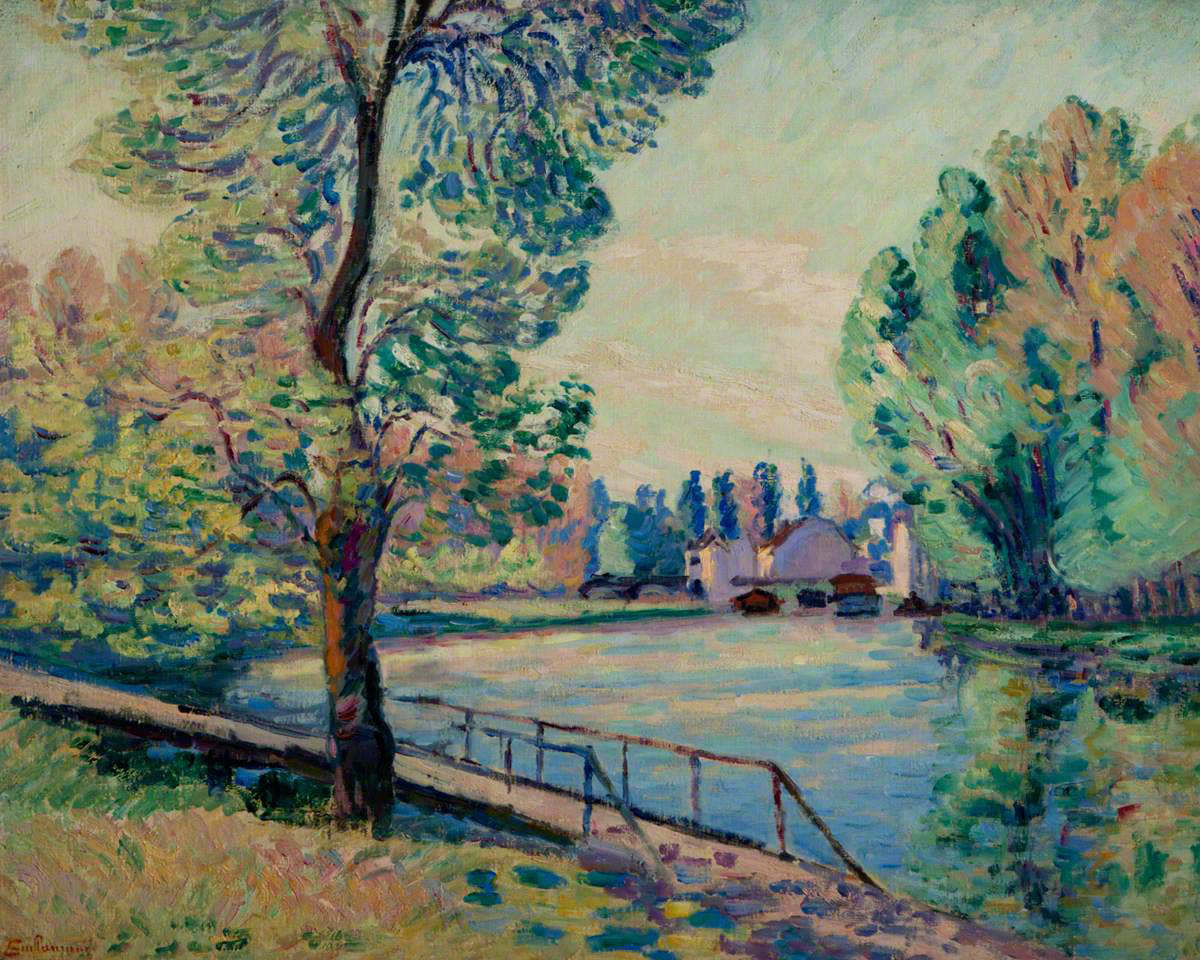

Fig. 2. Armand Guillaumin, The Jetty, ca. 1902, oil on canvas, 20 1/2 x 25 in. (52.5 x 63.5 cm), National Trust for Scotland, Brodie Castle, 73.555

Fig. 2. Armand Guillaumin, The Jetty, ca. 1902, oil on canvas, 20 1/2 x 25 in. (52.5 x 63.5 cm), National Trust for Scotland, Brodie Castle, 73.555

Painted on a standard size-15standard-format supports: Commercially prepared supports available through art suppliers, which gained popularity in the nineteenth century during the industrialization of art materials. Available in three formats figure (portrait), paysage (landscape), and marine (marine), these were numbered 1 through 120 to indicate their size. For each numbered size, marine and paysage had two options available: a larger format (haute) and smaller (basse) format. canvas (65 x 54 cm) that was small enough to facilitate working directly outdoors, the Nelson-Atkins landscape belongs to a subgroup of six works realized from similar vantage points. A smaller, more loosely handled version (Fig. 1) is likely a preparatory study, while another canvas with autumnal trees shows a vantage point slightly leftward, shifting the town into the distant right (or west) corner (Fig. 2). All three works include a diagonal footbridge spanning the foreground. In contrast, Moret, The Morning, or The Old Samois (Fig. 3), The Old Samois (Fig. 4),2See Georges Serret and Dominique Fabiani, Armand Guillaumin, 1841–1927: Catalogue raisonné de l’œuvre peint (Paris: Mayer, 1971), nos. 502, 503. Although the Nelson-Atkins painting is not included in the first volume of Guillaumin’s catalogue raisonné, it will be featured in a forthcoming supplement. and a larger canvas at the Tate (Fig. 5) omit the footbridge and move closer to the town, adding boaters or tethered boats indicating proximity to the Matrat Boatyard.3See, for example, Alfred Sisley, The Matrat Boatyard, Moret-sur-Loing, Rainy Weather, 1892, oil on canvas, 23 7/8 x 29 1/8 in. (60.7 x 74 cm), Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT, 1983.53.7, https://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/26800. The Nelson-Atkins painting notably omits the fisherman seen in figures 3 and 4, focusing instead on the architecture and vibrant reflections of light in the Loing river. Both Moret, The Morning, or The Old Samois (Fig. 3) and the Nelson-Atkins composition were included in the Henri Vian sale at the Galerie Georges Petit in 1919 as lots 13 and 14 respectively.4See Catalogue de tableaux modernes, aquarelles, pastels, dessins . . . Composant la Collection de M. Henri Vian . . . Par suite du décès de Mme Vian (Paris: Galerie Georges Petit, 1919), lots 13 and 14. The collector and metalsmith Henri Séraphin Louis Vian (1858–1904) and his wife, Louise Vian (née Brousse, 1866–1914), most likely acquired the canvases directly from the artist, considering the short window between their date of execution in 1902 and Henri’s death in 1904.5Theo van Gogh was Guillaumin’s dealer until Theo’s death in 1891. Thereafter, Guillaumin was known to sell through Galerie Durand-Ruel. The author checked with the Durand-Ruel archives; however, there is no record of this painting having been handled by that firm. See correspondence from Flavie Durand-Ruel to Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, April 3, 2021; copy in NAMA curatorial file. Given the verso inscription on the Nelson-Atkins canvas—“Soir, no. 2” (Evening, no. 2)—and the fact that it is the same canvas size as the morning scene, it is almost certain that Guillaumin considered them pendantspendant: One of two paintings conceived as a pair and intended to be displayed togther., suggesting a pairing intended to capture the contrasting moods of morning and evening.

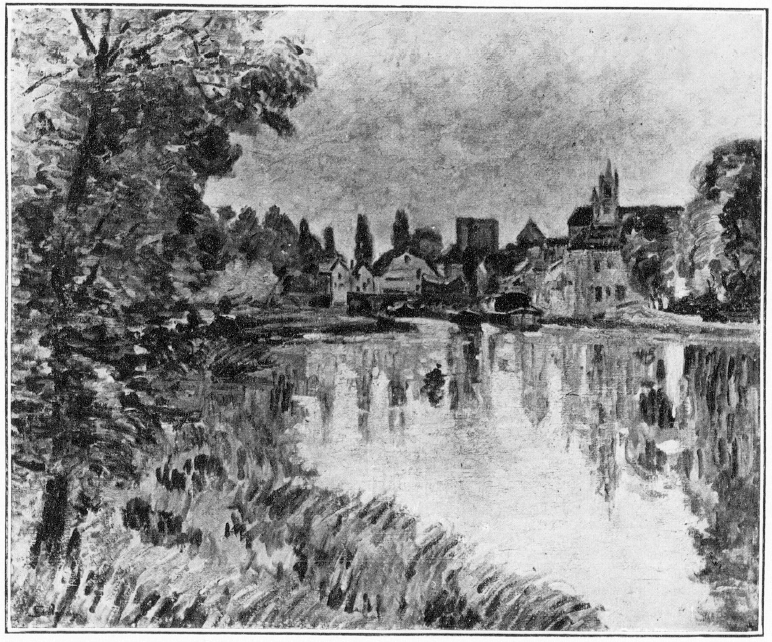

Fig. 3. Armand Guillaumin, Moret, The Morning, or The Old Samois, ca. 1902, oil on canvas, 21 1/4 x 25 5/8 in. (54 x 65 cm), repro. in Catalogue de tableaux modernes, aquarelles, pastels, dessins (Paris: Galerie Georges Petit, November 27, 1919), lot 13

Fig. 3. Armand Guillaumin, Moret, The Morning, or The Old Samois, ca. 1902, oil on canvas, 21 1/4 x 25 5/8 in. (54 x 65 cm), repro. in Catalogue de tableaux modernes, aquarelles, pastels, dessins (Paris: Galerie Georges Petit, November 27, 1919), lot 13

Fig. 4. Armand Guillaumin, The Old Samois, ca. 1902, oil on canvas, 19 3/4 x 24 in. (50 x 61 cm), illustrated in Georges Serret and Dominique Fabiani, Armand Guillaumin, 1841–1927; Catalogue Raisonné de l’Œuvre Peint (Paris: Mayer, 1971), no. 503

Fig. 4. Armand Guillaumin, The Old Samois, ca. 1902, oil on canvas, 19 3/4 x 24 in. (50 x 61 cm), illustrated in Georges Serret and Dominique Fabiani, Armand Guillaumin, 1841–1927; Catalogue Raisonné de l’Œuvre Peint (Paris: Mayer, 1971), no. 503

Fig. 5. Armand Guillaumin, Moret-sur-Loing, 1902, oil on canvas, 23 5/8 x 28 3/4 in. (60 x 73 cm), Tate, London, N04824

Fig. 5. Armand Guillaumin, Moret-sur-Loing, 1902, oil on canvas, 23 5/8 x 28 3/4 in. (60 x 73 cm), Tate, London, N04824

Although we only have a black-and-white image of the morning scene, distinct variations in palette across other versions highlight Guillaumin’s exploration of changing light and atmospheric conditions. While it remains uncertain which time of day Guillaumin realized The Old Samois (Fig. 4), given the soft pinks and greens he uses to evoke the diffused light rising from the east, on the left side of the canvas, it is likely a morning scene, while the evening view (the Nelson-Atkins Moret-sur-Loing composition), is suffused with deeper shadows along the far bank, and cooler, more crisp tones evocative of the onset of night. In Moret-sur-Loing, Guillaumin divides the picture plane into distinct zones: a diagonal walkway spans the foreground, separating it from the middle ground, while the distant shoreline, with its horizontal row of poplars, bridge, and attendant buildings, marks the boundary between midground and background sky. As in many of his works, including Morning, Rouen—realized in 1904, two years after Moret-sur-Loing—Guillaumin employs a series of diagonal recessional lines that lead the eye from the foreground to the background. These compositional elements help structure the space and create depth. He also utilizes distinct brushwork in each of these registers to identify mood and subject matter. For example, in Moret-sur-Loing, he uses thin, wispy strokes of relatively dry, chalky pigment to convey an atmospheric sky, and a thicker application of oil-laden pigment in the water to capture its glistening surface. While today a thin, later application of synthetic varnish deepens the tones of these incredibly rich areas, it is likely that Guillaumin’s original intent was to leave the surface unvarnished, as Monet and other Impressionists also preferred.6Guillaumin included a handwritten inscription, “ne pas vernir” (do not varnish), on the verso of another Moret painting from 1902. See Armand Guillaumin, Moret sur Loing, 1902, oil on canvas, 21 7/8 x 26 in. (55.5 x 66 cm), sold at Bonham’s, Paris, “Impressionist and Modern Art Online,” April 22–May 2, 2024, lot 1, https://www.bonhams.com/auction/29891/lot/1/armand-guillaumin-1841-1927-moret-sur-loing. Guillaumin and many fellow Impressionists, including his lifelong friend Camille Pissarro, preferred to leave their canvases unvarnished. Pissarro included a similar verso note not to varnish his 1880 painting Landscape at Chaponval (1880; Musée d’Orsay, Paris). See David Bomford et al., Art in the Making: Impressionism (London: Yale University Press, 1991), 101. For more on this preference by impressionist artists to leave their pictures unvarnished, see also Michael Swicklick, “French Painting and the Use of Varnish, 1750–1900,” Conservation Research: Studies in the History of Art 41, no. 2 (1993): 168–69; Anthea Callen, “The Unvarnished Truth: Mattness, ‘Primitivism,’ and Modernity in French Painting, c. 1870–1907,” Burlington Magazine 136, no. 1100 (November 1994): 738. Complementary color pairings appear in the juxtaposition of the evergreens’ vertical red tree trunks surrounded by deep green foliage at right and in the blue-and-orange-banded deciduous tree trunks in the left foreground. This color pairing appears again in short horizontal strokes in the water in the immediate foreground. The surface of the water contains nearly every color in the composition in directional strokes of varying thickness, with the long, thick, vertical strokes of orange (as reflections of tree trunks) scumbledscumble: A thin layer of opaque or semi-opaque paint that partially covers and modifies the underlying paint. across earlier strokes of deep purple and blue along the right edge of the painting.

Guillaumin’s biographers and scholars have made various attempts to date the canvases, offering a range of possibilities from 1895 to 1902. However, given the compositional similarities among this subgroup of six canvases, Guillaumin probably painted all of them during a single visit to Moret-sur-Loing. A firmly inscribed date on one Moret canvas outside of this subgroup places him there in May 1902, offering crucial evidence for the chronology of his paintings.7The painting cited in n. 6 (which sold at Bonham’s, Paris, “Impressionist and Modern Art Online,” April 22–May 2, 2024, lot 1) is also inscribed on a verso stretcher, “Moret, Mai 1902, matin.” Furthermore, an article authored in 1914 (during the artist’s lifetime) includes a reproduction of The Old Samois (Fig. 4) and dates it 1902.8See Charles Louis Borgmeyer, “Armand Guillaumin (Chapter X: ‘The Master Impressionists’),” Fine Arts Journal 30, no. 2 (February 1914): 57. Additionally, a letter from the artist’s daughter, Marguerite, in 1954 recalls her presence in Moret in 1902, during a period of convalescence, noting that her father joined her there to keep her company.9Guillaumin’s widow and their daughter Marguerite, who was born in 1893 and would have been nine years old in 1902, were certain Guillaumin was in Moret in 1902. In an unidentified letter, Marguerite wrote that “as child, I was there convalescing, and my father, who was an excellent father, installed himself there at the time not to leave me on my own.” See Marguerite Guillaumin to unspecified recipient, December 12, 1954, quoted and translated in Ronald Alley, Catalogue of the Tate Gallery’s Collection of Modern Art Other than Works by British Artists (London: Tate Gallery and Sotheby Parke-Bernet, 1981), 345.

While Guillaumin’s mastery of color and composition demonstrate his aesthetic preoccupations, these works also reveal deeper thematic interests. In particular, his depictions of Moret-sur-Loing reflect an enduring concern with labor and industry, elements that are subtly integrated in the Nelson-Atkins composition.10For more on this broader theme of urbanization and industrialization in Impressionist painting, see James H. Rubin, Impressionism and the Modern Landscape: Productivity, Technology, and Urbanization from Manet to Van Gogh (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008), 70. The Provencher mill, which once harnessed the Loing’s current, and the washhouse where women laundered clothes (the orange barge with blue roof seen in the water at distant back right) reflect the working river’s historical significance. Unlike the riverscapes of Monet11Admittedly, Monet, who came from a seaport town, understood working ports and included many in his paintings (as well as other examples of industry); however, Rubin argues that Guillaumin “was instrumental in introducing the theme [of industrial waterways] to Impressionist painting.” Rubin, Impressionism and the Modern Landscape, 70. and Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919), where leisure dominates, Guillaumin’s focus on different elements underscores his commitment to a working-class narrative, a perspective shaped by his socialist convictions and longstanding friendship with Pissarro. Many of these same motifs of work and industry appear in the group of paintings Pissarro produced while in Moret in 1901 and 1902.12See Joachim Pissarro and Claire Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Critical Catalogue of Paintings, trans. Mark Hutchinson and Michael Taylor (Paris: Wildenstein Institute Publications, 2005), nos. 1367–1369, 1431–1435, pp. 3:840–41, 874–76. In fact, some of their vantage points are so close, it suggests that Pissarro and Guillaumin may have been painting together, as they had done in the 1870s in Pontoise and Auvers.13Camille Pissarro, Banks of the Loing, Moret, ca. 1902, oil on canvas, 25 5/8 x 31 7/8 in. (65 x 81 cm), private collection; see Pissarro and Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Critical Catalogue of Paintings, no. 1435, p. 3:876. See also Armand Guillaumin, Moret sur Loing, cited in n. 6.

At the time of his 1902 visit to Moret, Guillaumin was sixty-one years old, while Pissarro was seventy-two. The two artists shared a deep friendship, having met in the 1860s at the Académie Suisse, where they were joined by other key figures of the emerging Impressionist group, including Paul Cezanne (1839–1906).14Paul Cezanne painted with Pissarro and Guillaumin in Pointoise and Auvers in the 1870s. See John Rewald, “Cézanne and Guillaumin,” in Études d’art français offertes à Charles Sterling, ed. Charles Sterling, Albert Châtelet, and Nicole Reynaud (Paris: Presses universitaires de France, 1975), 343–53. While Pissarro started out as a mentor to the junior Guillaumin, their relationship evolved over the years, and he came to solicit Guillaumin’s opinion of his works.15See Aimee Marcereau DeGalan’s entry for Camille Pissarro’s Poplars, Sunset at Eragny in this volume, https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.646.5407. Pissarro had visited Moret several times, particularly in 1899, 1901, and—most importantly for the present essay—May of 1902, to visit his son Georges, who moved there in 1899. Given their longstanding bond, Guillaumin’s decision to paint in Moret was likely motivated, at least in part, by the opportunity to reconnect with his old friend. Indeed, Pissarro’s eldest son, Lucien, recognized how special it was to spend time with fellow artists, imploring his father to “tell Georges I’m terribly jealous—Oh well, it’s damn tempting to spend some time together between painters!!”16“Georges est rudiment veinard de t’avoir pour lui tout seul–dis lui que je suis attrocement jaloux—C’est égal, c’est bougrement tentant de passer quelque temps ensemble entre peintres!!” (author’s own translation). Lucien Pissarro to Camille Pissarro, June 27, 1901, cited in Anne Thorold, ed., The Letters of Lucien to Camille Pissarro, 1883–1903 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 695–96. Lucien’s comment highlights the camaraderie and inspiration shared among these painters, a dynamic that may have drawn Guillaumin to Moret in search of both artistic renewal and companionship. Pissarro died the following year, making this an especially poignant reunion—one of the last moments the two could share their artistic dialogue in person. In this light, Moret-sur-Loing and its pendant take on a deeper resonance, not only as vibrant explorations of color and atmosphere but also as quiet testaments to friendship, memory, and the enduring creative bonds that shaped Guillaumin’s career.

Notes

-

The mill was reduced to its foundation and waterwheel following World War II; see Sylvie Patin’s catalogue entry for “The Provencher Watermill at Moret,” in Alfred Sisley, ed. MaryAnne Stevens (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 1992), 204, no. 55.

-

See Georges Serret and Dominique Fabiani, Armand Guillaumin, 1841–1927: Catalogue raisonné de l’œuvre peint (Paris: Mayer, 1971), nos. 502, 503. Although the Nelson-Atkins painting is not included in the first volume of Guillaumin’s catalogue raisonné, it will be featured in a forthcoming supplement.

-

See, for example, Alfred Sisley, The Matrat Boatyard, Moret-sur-Loing, Rainy Weather, 1892, oil on canvas, 23 7/8 x 29 1/8 in. (60.7 x 74 cm), Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT, 1983.53.7, https://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/26800.

-

See Catalogue de tableaux modernes, aquarelles, pastels, dessins . . . Composant la Collection de M. Henri Vian . . . Par suite du décès de Mme Vian (Paris: Galerie Georges Petit, 1919), lots 13 and 14.

-

Theo van Gogh was Guillaumin’s dealer until Theo’s death in 1891. Thereafter, Guillaumin was known to sell through Galerie Durand-Ruel. The author checked with the Durand-Ruel archives; however, there is no record of this painting having been handled by that firm. See correspondence from Flavie Durand-Ruel to Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, April 3, 2021; copy in NAMA curatorial file.

-

Guillaumin included a handwritten inscription, “ne pas vernir” (do not varnish), on the verso of another Moret painting from 1902. See Armand Guillaumin, Moret sur Loing, 1902, oil on canvas, 21 7/8 x 26 in. (55.5 x 66 cm), sold at Bonham’s, Paris, “Impressionist and Modern Art Online,” April 22–May 2, 2024, lot 1, https://www.bonhams.com/auction/29891/lot/1/armand-guillaumin-1841-1927-moret-sur-loing. Guillaumin and many fellow Impressionists, including his lifelong friend Camille Pissarro, preferred to leave their canvases unvarnished. Pissarro included a similar verso note not to varnish his 1880 painting Landscape at Chaponval (1880; Musée d’Orsay, Paris). See David Bomford et al., Art in the Making: Impressionism (London: Yale University Press, 1991), 101. For more on this preference by impressionist artists to leave their pictures unvarnished, see also Michael Swicklick, “French Painting and the Use of Varnish, 1750–1900,” Conservation Research: Studies in the History of Art 41, no. 2 (1993): 168–69; Anthea Callen, “The Unvarnished Truth: Mattness, ‘Primitivism,’ and Modernity in French Painting, c. 1870–1907,” Burlington Magazine 136, no. 1100 (November 1994): 738.

-

The painting cited in n. 6 (which sold at Bonham’s, Paris, “Impressionist and Modern Art Online,” April 22–May 2, 2024, lot 1) is also inscribed on a verso stretcher, “Moret, Mai 1902, matin.”

-

See Charles Louis Borgmeyer, “Armand Guillaumin (Chapter X: ‘The Master Impressionists’),” Fine Arts Journal 30, no. 2 (February 1914): 57.

-

Guillaumin’s widow and their daughter Marguerite, who was born in 1893 and would have been nine years old in 1902, were certain Guillaumin was in Moret in 1902. In an unidentified letter, Marguerite wrote that “as child, I was there convalescing, and my father, who was an excellent father, installed himself there at the time not to leave me on my own.” See Marguerite Guillaumin to unspecified recipient, December 12, 1954, quoted and translated in Ronald Alley, Catalogue of the Tate Gallery’s Collection of Modern Art Other than Works by British Artists (London: Tate Gallery and Sotheby Parke-Bernet, 1981), 345.

-

For more on this broader theme of urbanization and industrialization in Impressionist painting, see James H. Rubin, Impressionism and the Modern Landscape: Productivity, Technology, and Urbanization from Manet to Van Gogh (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008), 70.

-

Admittedly, Monet, who came from a seaport town, understood working ports and included many in his paintings (as well as other examples of industry); however, Rubin argues that Guillaumin “was instrumental in introducing the theme [of industrial waterways] to Impressionist painting.” Rubin, Impressionism and the Modern Landscape, 70.

-

See Joachim Pissarro and Claire Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Critical Catalogue of Paintings, trans. Mark Hutchinson and Michael Taylor (Paris: Wildenstein Institute Publications, 2005), nos. 1367–1369, 1431–1435, pp. 3:840–41, 874–76.

-

Camille Pissarro, Banks of the Loing, Moret, ca. 1902, oil on canvas, 25 5/8 x 31 7/8 in. (65 x 81 cm), private collection; see Pissarro and Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Critical Catalogue of Paintings, no. 1435, p. 3:876. See also Armand Guillaumin, Moret sur Loing, cited in n. 6.

-

Paul Cezanne painted with Pissarro and Guillaumin in Pointoise and Auvers in the 1870s. See John Rewald, “Cézanne and Guillaumin,” in Études d’art français offertes à Charles Sterling, ed. Charles Sterling, Albert Châtelet, and Nicole Reynaud (Paris: Presses universitaires de France, 1975), 343–53.

-

See Aimee Marcereau DeGalan’s entry for Camille Pissarro’s Poplars, Sunset at Eragny in this volume.

-

“Georges est rudiment veinard de t’avoir pour lui tout seul–dis lui que je suis attrocement jaloux—C’est égal, c’est bougrement tentant de passer quelque temps ensemble entre peintres!!” (author’s own translation). Lucien Pissarro to Camille Pissarro, June 27, 1901, cited in Anne Thorold, ed., The Letters of Lucien to Camille Pissarro, 1883–1903 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 695–96.

Technical Entry

Technical entry forthcoming.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Armand Guillaumin, Moret-sur-Loing, Evening Effect, No. 2, ca. 1902,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.622.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Armand Guillaumin, Moret-sur-Loing, Evening Effect, No. 2, ca. 1902,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.622.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Armand Guillaumin, Moret-sur-Loing, Evening Effect, No. 2, ca. 1902,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.622.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Armand Guillaumin, Moret-sur-Loing, Evening Effect, No. 2, ca. 1902,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.622.4033.

Henri Séraphin Louis Vian (1858–1904), Paris, by 1904 [1];

Inherited by his wife, Louise Vian (née Brousse, 1866–1914), Paris and Noisy-le-Grand, 1904–1914 [2];

Purchased at her posthumous sale, Tableaux modernes, aquarelles, pastels, dessins par Cecil Aldin, A. Guillaumin, H. Harpignies, H. Lebasque, N. Maufra, E. Méret, G. Ogier, C. Pissarro, Seyssaud, etc., 27 oeuvres importantes par Albert Lebourg, 6 tableaux par Fantin-Latour, Composant la Collection de M. Henri Vian . . . Par suite du décès de Mme Vian, Galerie Georges Petit, Paris, November 27, 1919, lot 14, as Moret; effect du soir, by unknown buyer, 1919;

Sold, Gravures, Dessins, Sculptures, Peintures XIXe–XXe, Rossini S.A., Paris, June 25, 2002, lot 60, as Le Vieux-Samois;

Private collection, France [3];

With Hammer Galleries, New York, stock no. S27166-01, by 2003–October 6, 2006;

Purchased from Hammer Galleries, New York, by Min-Hwan (b. 1949) and Yu-Fan (b. 1951) Kao, Leawood, Kansas, October 6, 2006–June 11, 2021;

Their gift to the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 2021.

Notes

[1] Henri Vian was a collector and bronze maker, who owned an atelier

and showroom in the Hôtel Salé (also called the Hôtel de Juigné), at 5 rue de Thorigny (today the Musée Picasso Paris). He was

the son of Séraphin and Léonie Adélaïde (née Laplaine) Vian, both bronze makers.

According to Vian’s certificate of decease, he died at his residence on

rue de Thorigny; it is possible the Vians lived in the grand Parisian mansion

where the atelier and showrooms were. See Paris archives, décès, 1904, 07, 7D124, under no. 1468.

[2] Louise Vian and her family were living in Noisy-le-Grand, outside of Paris, by 1911, and Louise listed her profession as bronze dealer. See census, 1911, Noisy-le-grand, 93/100/15. The Vians had three children, who may have inherited the painting after their parents’ deaths: Henriette Marie Lucie Vian (1886–1917); Henri Louis Edmond Vian (1892–1943); and Paul Vian (1897–1944).

[3] For constituent, see 19th and 20th Century European Collection, exh. cat. (New York: Hammer Galleries, 2006), 16–17, (repro.), as Moret sur Loing.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Armand Guillaumin, Moret-sur-Loing, Evening Effect, No. 2, ca. 1902,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.622.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Armand Guillaumin, Moret-sur-Loing, Evening Effect, No. 2, ca. 1902,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.622.4033.

Armand Guillaumin, The Jetty, ca. 1902, oil on canvas, 20 1/2 x 25 in. (52.5 63.5 cm), National Trust for Scotland, Brodie Castle, 73.555.

Armand Guillaumin, The Old Samois, ca. 1902, oil on canvas, 19 3/4 x 24 in. (50 x 61 cm), illustrated in Georges Serret and Dominique Fabiani, Armand Guillaumin, 1841–1927: Catalogue raisonné de l’œuvre peint (Paris: Mayer, 1971), no. 503, as Le Vieux Samois.

Armand Guillaumin, Moret, The Morning, ca. 1902, oil on canvas, 21 1/4 x 25 5/8 in. (54 x 65 cm), illustrated in Catalogue de tableaux modernes, aquarelles, pastels, dessins (Paris: Galerie Georges Petit, November 27, 1919), lot 13, as Moret; le matin.

Armand Guillaumin, Moret-sur-Loing, 1902, oil on canvas, 23 5/8 x 28 3/4 in. (60 x 73 cm), Tate Gallery, London, N04824.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Armand Guillaumin, Moret-sur-Loing, Evening Effect, No. 2, ca. 1902,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.622.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Armand Guillaumin, Moret-sur-Loing, Evening Effect, No. 2, ca. 1902,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.622.4033.

19th and 20th Century European Collection, Hammer Galleries, New York, 2003, unnumbered, as Moret sur Loing.

19th and 20th Century European Collection, Hammer Galleries, New York, June 1–August 1, 2006, unnumbered, as Moret sur Loing.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Armand Guillaumin, Moret-sur-Loing, Evening Effect, No. 2, ca. 1902,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.622.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Armand Guillaumin, Moret-sur-Loing, Evening Effect, No. 2, ca. 1902,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.622.4033.

Raymond Bouyer, “Collection de M. Henri Vian,” La Chronique des Arts (October–November 1919): 246, as Moret.

“Collection de M. Henri Vian,” La Chronique des Arts (December 1919): 16, as Moret; effect du soir.

Tableaux modernes, aquarelles, pastels, dessins par Cecil Aldin, A. Guillaumin, H. Harpignies, H. Lebasque, N. Maufra, E. Méret, G. Ogier, C. Pissarro, Seyssaud, etc., 27 oeuvres importantes par Albert Lebourg, 6 tableaux par Fantin-Latour, Composant la Collection de M. Henri Vian . . . Par suite du décès de Mme Vian (Paris: Galerie Georges Petit, 1919), 13, (repro.), as Moret; effect du soir.

Gravures, Dessins, Sculptures, Peintures XIXe–XXe (Paris: Rossini, 2002), 17, (repro.), as Le Vieux Samois.

19th and 20th Century European Collection, exh. cat. (New York: Hammer Galleries, 2003), 25, (repro.), as Moret sur Loing.

19th and 20th Century European Collection, exh. cat. (New York: Hammer Galleries, 2006), 17–16, (repro.), as Moret sur Loing.

“Nelson-Atkins donor gifts enhance European collection,” ArtDaily (December 15, 2021): https://artdaily.cc/news/142058/Nelson-Atkins-donor-gifts-enhance-European-collection-#.YbomdbpMGUk.

“Nelson-Atkins welcomes French Impressionist works,” Live Auctioneers: Auction Central News (December 22, 2021): https://www.liveauctioneers.com/news/top-news/nelson-atkins-welcomes-french-impressionist-works/.