![]()

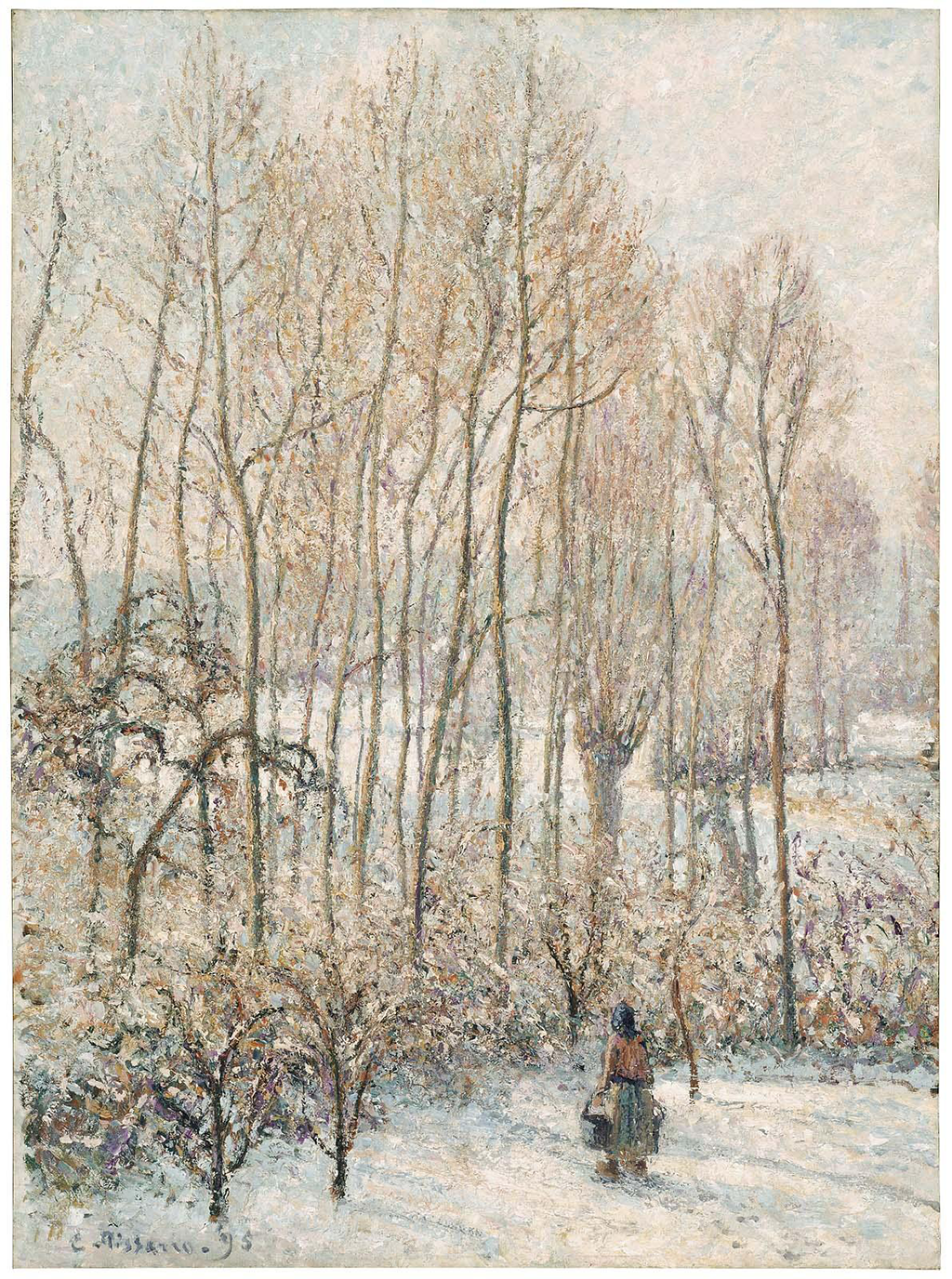

Camille Pissarro, Poplars, Sunset at Éragny, 1894

| Artist | Camille Pissarro, French, 1830–1903 |

| Title | Poplars, Sunset at Éragny |

| Object Date | 1894 |

| Alternate and Variant Titles | Peupliers à Eragny, soleil couchant; Poplar Trees at Eragny, Sunset |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (Unframed) | 28 15/16 x 23 7/8 in. (73.5 x 60.6 cm) |

| Signature | Signed and dated lower right: C. Pissarro. 94. |

| Credit Line | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Gift of the Laura Nelson Kirkwood Residuary Trust, 44-41/2 |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “Camille Pissarro, Poplars, Sunset at Eragny, 1894,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.646.5407.

MLA:

Marcereau DeGalan, Aimee. “Camille Pissarro, Poplars, Sunset at Eragny, 1894,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.646.5407.

In the spring of 1884, Camille Pissarro embarked on a significant artistic journey by renting a house in Éragny, a serene village nestled along the banks of the river Epte, just northwest of Paris.1Pissarro was exuberant about this move, writing to his son, Lucien, “Oui, nous avons choisi Éragny-sur-Epte ; la maison est superbe et bon marché : mille francs, avec jardin et prés. C’est à deux heures de Paris, j’ai trouvé le pays plus beau que Compiègne” (Yes, we have decided on Éragny-sur-Epte; the house is superb and inexpensive: a thousand francs, with garden and meadows. It’s two hours from Paris, I found the country more beautiful than Compiègne). Camille Pissarro, Paris, to Lucien Pissarro, March 1, 1884, in Janine Bailly-Herzberg, ed., Correspondance de Camille Pissarro (Paris: Editions du Valhermeil, 2003), 1:291. All translations by the author unless otherwise noted. The allure of this location proved irresistible, prompting Pissarro to acquire the house in 1892 and solidify his connection to the place that would inspire him for the last two decades of his life.2Pissarro rented the house for eight years from one Monsieur Dallemagne. While Pissarro was in London, his wife learned the property would be sold and asked their family friend Claude Monet for a loan of 15,000 francs to secure it. The house still stands at what is now 29 rue Camille-Pissarro. See Joachim Pissarro and Claire Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Critical Catalogue of Paintings, trans. Mark Hutchinson and Michael Taylor (Paris: Wildenstein Institute Publications, 2005), 3:499. Pissarro was captivated by Éragny’s scenic fields and meadows, and his artistic vision underwent a transformative shift there, when the Impressionist painter came under the spell of Neo-Impressionism’sNeo-Impressionism: A term coined in 1886 by French art critic Félix Fénéon to describe a style of painting pioneered by Georges Seurat. He and his followers espoused a scientific approach to color and a painting technique known as pointillism. systematic application of dots of pure color from 1886 to 1891. He returned to his Impressionist roots thereafter but with greater emphasis on capturing weather and light variations. As if to confirm those interests, he wrote to his son Lucien in 1891, “The weather has been very good these days—dry cold, white frost, and radiant sun—so I started a series of studies [out] of my window. . . . I feared that it was a bit the same motif, but the effects are so varied that they do completely different things.”3See Camille Pissarro, Éragny, to Lucien Pissarro, December 26, 1891, in Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 3:174. Indeed, the artist created numerous paintings focused on the seasonal evolution of the landscape as well as changes in color and light at different times of the day.

The year 1894 began strongly enough for Pissarro; as a sign of the growing American interest in Impressionism, the L. Crist Delmonico gallery in New York mounted an exhibition with works by Monet, Alfred Sisley (1839–1899), Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919), and Pissarro.5Frances Weitzenhoffer, The Havemeyers: Impressionism Comes to America (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1986), 94. In Paris, Pissarro had a monographic exhibition at Galerie Durand-Ruel from March 3 to 21, which featured thirty paintings, many grouped together in what Richard Brettell has called “series within series.”6See Richard R. Brettell’s catalogue entry for Haymaking at Éragny, in Pissarro Paintings and Works on Paper at the Art Institute of Chicago (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2015), para 3, https://publications.artic.edu/pissarro/reader/paintingsandpaper/section/24/24_anchor/p-24-3. Pissarro was involved in the selection of works with Durand-Ruel; see Camille Pissarro, Éragny, to Lucien Pissarro, February 16, 1894, in John Rewald and Lucien Pissarro, eds., Camille Pissarro: Letters to His Son Lucien, trans. Lionel Abel (Boston: MFA Publications, 2002), 253. Camille Pissarro—Tableaux, aquarelles, pastels, gouaches, held at Galerie Durand-Ruel, Paris, March 3–21, 1894, also included twenty watercolors, four gouaches, and fourteen pastels, for a total of sixty-eight works. See Exposition d’œuvres récentes de Camille Pissarro (Paris: Galerie Durand-Ruel, 1894). Pissarro had monographic exhibitions of fifty-two paintings in 1892 and forty-six paintings in 1893; see Pissarro and Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Critical Catalogue of Paintings, 1:363–64. Although the Nelson-Atkins painting was not among the works on view, the format of the exhibition, and Durand-Ruel’s acquisition of pictures in preparation for it, provide insight into the nature of his relationship with Pissarro, the market for the artist’s work, and the structure of the late nineteenth-century commercial art world in France. Unlike the traditional French SalonSalon, the: Exhibitions organized by the French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture (Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture) and its successor the Academy of Fine Arts (Académie des Beaux Arts), which took place in Paris from 1667 onward. model, which favored monumental paintings with single subjects, dealers’ exhibitions in Europe often featured works produced in series, which according to scholar Scott Allen “allowed the individual picture to accrue value through its association with an impressive larger whole.”7Scott Allen makes this point in his essay on Monet’s Rouen Cathedral; Scott Allen, “The Portal of Rouen Cathedral in Morning Light,” in Scholarly Essays: Deeper Dives into Objects from the J. Paul Getty Museum Collection (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Trust, 2019), https://museum-essays.getty.edu/paintings/sallan-monet-rouen. Allen cites scholars Harrison C. White and Cynthia A. White, whose pioneering publication Canvases and Careers: Institutional Change in the French Painting World (New York: Wiley, 1965), discusses what they term “the dealer-critic” system. Pissarro was aware of the commercial success of Monet’s grain stack series, exhibited by Durand-Ruel in 1891. While he admired the paintings’ beauty, he lamented in a letter to his son, dated April 9, that as a result, collectors seemed solely interested in haystacks.8See Camille Pissarro, Paris, to Lucien Pissaro, April 9, 1891, in Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 3:60. For a letter that reveals how Pissarro was taken aback by the beauty of Monet’s grain stacks, see Camille Pissarro, Paris, to Lucien Pissarro, May 5, 1891, in Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 3:72. Although the two artists’ approaches to painting series differed significantly, Pissarro may have been influenced by the marketing strategy behind Monet’s success, evident in Pissarro’s deliberate grouping of paintings with similar subjects in his exhibitions.9Brettell makes this observation in his catalogue entry for Haymaking at Éragny, n. 6.

Durand-Ruel had a strategy of his own. A few days before the opening of Pissarro’s exhibition, the dealer purchased four paintings from the artist for a total of 1,700 francs, a price significantly lower than Pissarro’s own prices. It was a shrewd move that frustrated the artist; his prices for an individual canvas in 1894 ranged from one thousand francs, for a canvas measuring 21 x 28 inches, to 2,500 francs, for a canvas measuring 36 x 28 inches.10For Pissarro’s prices in 1894, see Camille Pissarro, Paris, to Lucien Pissarro, November 22, 1894, in Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 3:511. Pissarro thought he might sell his canvases for more directly to a collector rather than through his dealer, but he also did not want to upset Durand-Ruel.11Pissarro grew increasingly frustrated with Durand-Ruel and tried to market his paintings elsewhere in London and Brussels in an effort to end his dependence on the dealer. See Alexia de Buffévent, “A Painter and His Age: Biography and Critical Reception,” in Pissarro and Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Critical Catalogue of Paintings, 1:255. Pissarro was in regular contact with fellow artist Mary Cassatt (American, 1844–1926), who was keen to connect a growing body of American collectors with French artists, but as yet nothing had materialized.12Notwithstanding any price differential between what Durand-Ruel paid Pissarro and what Pissarro may have received had he sold directly to the clients himself, Durand-Ruel’s purchases provided Pissarro with guaranteed sales. See Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, “A Painter and His Dealer: Camille Pissarro and Paul Durand-Ruel,” in Pissarro and Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Critical Catalogue of Paintings, 1:34–35. Pissarro held out hope that there would be additional sales or that, at the very least, Durand-Ruel would buy the remaining pictures, as he had with Pissarro’s previous two exhibitions in 1892 and 1893. However, Durand-Ruel only bought one additional painting from the show and re-acquired one he had sold to a collector the year before for the same amount.13For the specific pictures Durand-Ruel acquired in this sale and the prices he paid for them, see Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, “A Painter and His Dealer,” 1:35. There were other sales and auctions that included Pissarro’s works that year, most of which fetched extremely low prices. See De Buffévent, “A Painter and His Age,” 1:246–55. In the end, it was not a lucrative exhibition, and Pissarro’s financial situation grew more dire. He would have to be patient.

During this period of insecurity and introspection, Pissarro sought counsel from his longtime friend and fellow painter Armand Guillaumin (1841–1927). Pissarro recognized that something essential was missing in his work,17“Je commence à me dire, par suite de la froideur des amateurs, qu’il ya a en mon art quelque idée, quelque chose d’essential qui manque!” (I am beginning to tell myself, as a result of the coldness of amateur painters, that there is some idea in my art, something essential which is missing!). Camille Pissarro, Éragny, to Lucien Pissarro, October 25, 1894, in Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 3:498. and Guillaumin’s candid assessment of Pissarro’s Knokke paintings as banal resonated with Pissarro’s own feelings of artistic emptiness. His friend offered some advice: “We don’t like naive and simple motifs in France, we need something romantic.”18“Il [Guillaumin] trouvé mes toits rouges et mes motifs de Knokke absolutement banals, décidément, on n’aime pas en France les motifs naïfs et simples, il faut du romantique” (He [Guillaumin] found my red roofs and my Knokke motifs absolutely banal, honestly, we don’t like naive and simple motifs in France, we need something romantic). Camille Pissarro, Paris, to Georges Pissarro, November 20, 1894, in Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 3:508–9. Reflecting on (and defending) his approach to his Knokke paintings, Pissarro explained: “Naturally when I go for the first time to a country with a distinct character, I am forced to analyze more closely, I cannot embroider, I cannot indulge in fantasy, as in a country where I have constantly practiced.”19“Naturellement quand je vais pour la première fois dans un pays à caractère tranché, je suis forcé d’analyser de plus près, je ne puis broder, je ne puis me livrer à la fantaisie, comme dans un pays que je pratique sans cesse.” Camille Pissarro, Éragny, to Lucien Pissarro, November 4, 1894, in Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 3:502. In other words, he painted what he saw without amplifying or making up elements to suit his or others’ interests. Clearly, this approach was not working, at least not in terms of sales. Pissarro needed to change course, heed his dealer’s and his friend’s advice, return to a landscape he knew, and paint it with romantic feeling. Nothing could be more romantic than a sunset, particularly a sunset with a brooding sky and a moody palette, in a landscape he knew intimately.

In the Nelson-Atkins painting, Pissarro takes a particularly vibrant turn, rendering light and shadow through the use of a dark and somewhat strident palette of paired complementary colors. Purple/yellow and blue/orange tones dominate the foreground and sky, while green with small sporadic dots of red occupy the midground. These dark and rather ferocious colors call to mind Guillaumin’s palette, further evidence of his influence. Guillaumin had a large exhibition at the beginning of 1894, featuring at least one work with a setting sun and thirteen views of the village of Damiette, outside of Paris.20See Arsène Alexandre and Durand-Ruel et fils, Exposition Armand Guillaumin: Galeries Durand-Ruel, Paris, Janvier–Février 1894, exh. cat. (Paris: Impr. de l’art E. Moreau, 1894), lot 27, as Soleil couchant. The works on view in the exhibition ranged in date from 1883 to 1886. One of these Damiette pictures could have been his magisterial painting now in the Thyssen-Bornemisza collection, with its brilliant sunset sky of orange and purple clouds (Fig. 3). Pissarro saw and commented on this exhibition in January, remarking to Lucien that “it is astonishing how his work gains,” indicating how much the works had grown on him.21“Guillaumin a une très belle exposition chez Durand, vue dans son ensemble, c’est étonnant ce que cela gagne” (Guillaumin has a very beautiful exhibition at Durand, seen as a whole, it’s astonishing what it gains). Camille Pissarro, Paris, to Lucien Pissarro, January 21, 1894, in Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 3:419. Eleven months later, in the fall of 1894, while he was likely working on the Nelson-Atkins composition, Pissarro confided to his son Georges that he had been “haunted for some time by Guillaumin’s motifs.”22“Hanté depuis quelque-temps par les motifs de Guillaumin.” Camille Pissarro, Paris, to Georges Pissarro, November 20, 1894, in Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 3:509. Although Pissarro specifically meant Guillaumin’s varied motifs of rustic bridges and castles on crests of the hills, could he also have also been thinking about the artist’s bold and romantic use of color?23It is worth noting that in his Rouen Cathedral series, which Pissarro saw and admired, Monet employed vibrant colors veering toward expressive colorism, which also may have been on Pissarro’s mind in exploring a bold palette of his own.

Pissarro painted Poplars, Sunset at Éragny on a size 20 canvasstandard-format supports: Commercially prepared supports available through art suppliers, which gained popularity in the nineteenth century during the industrialization of art materials. Available in three formats figure (portrait), paysage (landscape), and marine (marine), these were numbered 1 through 120 to indicate their size. For each numbered size, marine and paysage had two options available: a larger format (haute) and smaller (basse) format.. Its rugged and varied surface, with the addition of a poplar tree at the far-right edge of the composition, was realized in at least two, possibly three, campaigns, with ample drying time in between. In the first campaign, it appears Pissarro created the background landscape, and then during a second phase of painting he scumbledscumble: A thin layer of opaque or semi-opaque paint that partially covers and modifies the underlying paint. in the poplar trees, whose tall, wispy, vertical trunks are made up of diverse strokes of purple, blue, brown, black, and umber, which highlight the glint of the setting sun on their surfaces. Sometime later, Pissarro went back in and added significant amounts of lush plum-colored paint to the foreground of the composition. The discovery by senior paintings conservator Mary Schafer of a small paper label in the left foreground, with considerable wet-into-wetwet-into-wet: An oil painting technique which involves blending of colors on the picture surface. paint on top, further substantiates a later campaign of paint.27Technical notes by Mary Schafer, NAMA paintings conservator, January 17, 2012, NAMA conservation files. Pissarro was known to rework compositions in order to strengthen light effects, enrich shadows, and build up his surfaces. In some cases, he would rework pictures a decade or more after completion of the original composition.28Joachim Pissarro notes at least two paintings Pissarro created in Éragny that he retouched thirteen years later. Girl Tending Cattle on the Banks of the Epte Bazincourt, 1888–1901 (cat. no. 861), is listed under two numbers in Ludovic-Rodo Pissarro’s catalogue raisonné, initially as a distinctly pointillist composition realized in 1888 (PV 718) and again entirely reworked in 1901 as PV 1205. See Ludovico Rodo Pissarro and Lionello Venturi, Camille Pissarro: Son art, Son œuvre (Paris: Pierre Rosenberg, 1939). As Joachim Pissarro notes, the fact that the artist repainted and re-dated it thirteen years after its initial execution suggests that it was returned to him at some point after it was acquired and before it was given a new date. Joachim Pissarro acknowledges that Camille Pissarro reworked his oils, but only when they remained in his studio. Girl Tending Cattle on the Banks of the Epte Bazincourt is the only instance he was aware of where the painting was “touched up” after leaving the artist’s possession. He also retouched Peasant Woman Chatting in a Farmyard, Éragny, 1889–1902 (cat. no. 868), thirteen years later. While the latter is dated 1895–1902 by the artist, Joachim Pissarro notes that correspondence with Theo van Gogh indicates it was ready to be sold as early as 1889. Landscape with a Flock of Sheep (cat. no. 873) is double-dated 1889 and 1902; a signature in the bottom right corner (done in 1889) has largely been covered over with a later campaign of paint from 1902. See Pissarro and Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Critical Catalogue of Paintings, 3:564, 568–69, and 573. Because the Nelson-Atkins painting was not included in the spring 1894 exhibition, and Pissarro spent most of the summer into fall of 1894 in Brussels, where he painted the Knokke series, it is likely he began this composition after his return to Éragny later that fall. He would have had until April 10, 1895, to work and rework the painting, since it was then acquired by Durand-Ruel.29Paul-Louis Durand-Ruel and Flavie Durand-Ruel, Durand-Ruel et Cie, Paris, to Nicole Myers, NAMA, January 11, 2016, NAMA curatorial file. While we do not know the price Durand-Ruel paid to secure the Nelson-Atkins painting, one can imagine the range based on what he offered the artist for his larger poplars picture on November 22, 1895. The dealer paid the artist 1,250 francs for Poplars, Éragny (1895; Metropolitan Museum of Art). This painting also appeared in the 1896 Durand-Ruel exhibition.

Fig. 5. Camille Pissarro, Poplars, Overcast Sky, Éragny, 1895, oil on canvas, 24 x 29 5/16 in. (61 x 74.4 cm), Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, 49/20. Photo: Art Gallery of Ontario / Bequest of Frederic William Gerald Fitzgerald, 1949 / Bridgeman Images

Fig. 5. Camille Pissarro, Poplars, Overcast Sky, Éragny, 1895, oil on canvas, 24 x 29 5/16 in. (61 x 74.4 cm), Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, 49/20. Photo: Art Gallery of Ontario / Bequest of Frederic William Gerald Fitzgerald, 1949 / Bridgeman Images

Fig. 6. Camille Pissarro, Sun Setting at Éragny, 1894, oil on canvas, 24 x 32 1/2 in. (61 x 82.6 cm), private collection

Fig. 6. Camille Pissarro, Sun Setting at Éragny, 1894, oil on canvas, 24 x 32 1/2 in. (61 x 82.6 cm), private collection

Camille Pissarro’s time in Éragny was marked not only by artistic experimentation but also by strategic decisions born from his financial circumstances and his relationship with Paul Durand-Ruel. Despite financial hardships and setbacks in the art market, Pissarro remained resilient, adapting his approach and seeking innovative ways to promote his work. His collaboration with Durand-Ruel, while at times contentious, played a crucial role in shaping his artistic output and securing his place in the art world. While this relationship was mutually beneficial to some extent, the power imbalance and Pissarro’s lack of alternatives highlight the complexities and challenges of their interactions. As exemplified by Poplars, Sunset at Éragny, Pissarro’s ability to adjust his style and strategy in response to market demands underscores his significance as both a master painter and a keen observer of the art market’s dynamics.

Notes

-

Pissarro was exuberant about this move, writing to his son, Lucien, “Oui, nous avons choisi Éragny-sur-Epte ; la maison est superbe et bon marché : mille francs, avec jardin et prés. C’est à deux heures de Paris, j’ai trouvé le pays plus beau que Compiègne” (Yes, we have decided on Éragny-sur-Epte; the house is superb and inexpensive: a thousand francs, with garden and meadows. It’s two hours from Paris, I found the country more beautiful than Compiègne). Camille Pissarro, Paris, to Lucien Pissarro, March 1, 1884, in Janine Bailly-Herzberg, ed., Correspondance de Camille Pissarro (Paris: Editions du Valhermeil, 2003), 1:291. All translations by the author unless otherwise noted.

-

Pissarro rented the house for eight years from one Monsieur Dallemagne. While Pissarro was in London, his wife learned the property would be sold and asked their family friend Claude Monet for a loan of 15,000 francs to secure it. The house still stands at what is now 29 rue Camille-Pissarro. See Joachim Pissarro and Claire Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Critical Catalogue of Paintings, trans. Mark Hutchinson and Michael Taylor (Paris: Wildenstein Institute Publications, 2005), 3:499.

-

See Camille Pissarro, Éragny, to Lucien Pissarro, December 26, 1891, in Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 3:174.

-

Renovations, including the addition of a north-facing window in Pissarro’s studio, took from June to late October 1893. In letters to his son, Pissarro outlines the orientation of the windows toward distinct cardinal points. See Camille Pissarro, Éragny, to Lucien Pissarro, August 27, 1893, in Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 3:359.

-

Frances Weitzenhoffer, The Havemeyers: Impressionism Comes to America (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1986), 94.

-

See Richard R. Brettell’s catalogue entry for Haymaking at Éragny, in Pissarro Paintings and Works on Paper at the Art Institute of Chicago (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2015), para 3, https://publications.artic.edu/pissarro/reader/paintingsandpaper/section/24/24_anchor/p-24-3. Pissarro was involved in the selection of works with Durand-Ruel; see Camille Pissarro, Éragny, to Lucien Pissarro, February 16, 1894, in John Rewald and Lucien Pissarro, eds., Camille Pissarro: Letters to His Son Lucien, trans. Lionel Abel (Boston: MFA Publications, 2002), 253. Camille Pissarro—Tableaux, aquarelles, pastels, gouaches, held at Galerie Durand-Ruel, Paris, March 3–21, 1894, also included twenty watercolors, four gouaches, and fourteen pastels, for a total of sixty-eight works. See Exposition d’œuvres récentes de Camille Pissarro (Paris: Galerie Durand-Ruel, 1894). Pissarro had monographic exhibitions of fifty-two paintings in 1892 and forty-six paintings in 1893; see Pissarro and Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Critical Catalogue of Paintings, 1:363–64.

-

Scott Allen makes this point in his essay on Monet’s Rouen Cathedral; Scott Allen, “The Portal of Rouen Cathedral in Morning Light,” in Scholarly Essays: Deeper Dives into Objects from the J. Paul Getty Museum Collection (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Trust, 2019), https://museum-essays.getty.edu/paintings/sallan-monet-rouen. Allen cites scholars Harrison C. White and Cynthia A. White, whose pioneering publication Canvases and Careers: Institutional Change in the French Painting World (New York: Wiley, 1965), discusses what they term “the dealer-critic” system.

-

See Camille Pissarro, Paris, to Lucien Pissaro, April 9, 1891, in Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 3:60. For a letter that reveals how Pissarro was taken aback by the beauty of Monet’s grain stacks, see Camille Pissarro, Paris, to Lucien Pissarro, May 5, 1891, in Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 3:72.

-

Brettell makes this observation in his catalogue entry for Haymaking at Éragny, n. 6.

-

For Pissarro’s prices in 1894, see Camille Pissarro, Paris, to Lucien Pissarro, November 22, 1894, in Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 3:511.

-

Pissarro grew increasingly frustrated with Durand-Ruel and tried to market his paintings elsewhere in London and Brussels in an effort to end his dependence on the dealer. See Alexia de Buffévent, “A Painter and His Age: Biography and Critical Reception,” in Pissarro and Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Critical Catalogue of Paintings, 1:255.

-

Notwithstanding any price differential between what Durand-Ruel paid Pissarro and what Pissarro may have received had he sold directly to the clients himself, Durand-Ruel’s purchases provided Pissarro with guaranteed sales. See Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, “A Painter and His Dealer: Camille Pissarro and Paul Durand-Ruel,” in Pissarro and Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Critical Catalogue of Paintings, 1:34–35.

-

For the specific pictures Durand-Ruel acquired in this sale and the prices he paid for them, see Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, “A Painter and His Dealer,” 1:35. There were other sales and auctions that included Pissarro’s works that year, most of which fetched extremely low prices. See De Buffévent, “A Painter and His Age,” 1:246–55.

-

Pissarro had been planning to send his son Félix to Belgium, where he knew no one, in an effort to diminish his boyish pranks. Pissarro was not fond of the idea, since he would have to accompany him. As it turned out, they landed in Brussels on June 25, a day after the assassination of President Sadi Carnot in Lyon by an Italian anarchist, Sante Caserio. Due to his own political affiliations with the anarchist party, Pissarro sheltered in place out of fear of being arrested. They returned to France on October 8. See Pissarro and Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Critical Catalogue of Paintings, 3:664.

-

Durand-Ruel quoted in Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, “A Painter and his Dealer: Camille Pissarro and Paul Durand-Ruel,” 1:36.

-

Camille Pissarro, Éragny, to Lucien Pissarro, October 25, 1894, in Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 3:498. “Monet demande des prix fous, pour sa peinture, on achète. . . . il est vrai que c’est un maître, mais c’est donc faux que je le sois, pour que l’on me dédaigne” (Monet asks crazy prices, for his painting, we buy . . . it is true that he is a master, but it is therefore false that I am, so that people disdain me). Monet was successful in securing 15,000 francs from some collectors, including Isaac Commando (for example, Rouen Cathedral, 1892; Musée d’Orsay). Pissarro wrote to Monet on October 21, 1894, requesting a date to visit him in his studio to see his “Cathedrales” with M. Viau, an interested collector. Camille Pissarro to Claude Monet, October 21, 1894, in Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 3:496.

-

“Je commence à me dire, par suite de la froideur des amateurs, qu’il ya a en mon art quelque idée, quelque chose d’essential qui manque!” (I am beginning to tell myself, as a result of the coldness of amateur painters, that there is some idea in my art, something essential which is missing!). Camille Pissarro, Éragny, to Lucien Pissarro, October 25, 1894, in Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 3:498.

-

“Il [Guillaumin] trouvé mes toits rouges et mes motifs de Knokke absolutement banals, décidément, on n’aime pas en France les motifs naïfs et simples, il faut du romantique” (He [Guillaumin] found my red roofs and my Knokke motifs absolutely banal, honestly, we don’t like naive and simple motifs in France, we need something romantic). Camille Pissarro, Paris, to Georges Pissarro, November 20, 1894, in Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 3:508–9.

-

“Naturellement quand je vais pour la première fois dans un pays à caractère tranché, je suis forcé d’analyser de plus près, je ne puis broder, je ne puis me livrer à la fantaisie, comme dans un pays que je pratique sans cesse.” Camille Pissarro, Éragny, to Lucien Pissarro, November 4, 1894, in Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 3:502.

-

See Arsène Alexandre and Durand-Ruel et fils, Exposition Armand Guillaumin: Galeries Durand-Ruel, Paris, Janvier–Février 1894, exh. cat. (Paris: Impr. de l’art E. Moreau, 1894), lot 27, as Soleil couchant. The works on view in the exhibition ranged in date from 1883 to 1886.

-

“Guillaumin a une très belle exposition chez Durand, vue dans son ensemble, c’est étonnant ce que cela gagne” (Guillaumin has a very beautiful exhibition at Durand, seen as a whole, it’s astonishing what it gains). Camille Pissarro, Paris, to Lucien Pissarro, January 21, 1894, in Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 3:419.

-

“Hanté depuis quelque-temps par les motifs de Guillaumin.” Camille Pissarro, Paris, to Georges Pissarro, November 20, 1894, in Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 3:509.

-

It is worth noting that in his Rouen Cathedral series, which Pissarro saw and admired, Monet employed vibrant colors veering toward expressive colorism, which also may have been on Pissarro’s mind in exploring a bold palette of his own.

-

All of the quotes about color in this paragraph are from the same letter: Camille Pissarro, Paris, to Lucien Pissarro, December 28, 1893, in Rewald and Pissarro, Camille Pissarro: Letters to His Son Lucien, 225.

-

Including to Antonin Personnaz, who lent six pictures to the exhibition. Pissarro likely introduced Personnaz to Guillaumin; see Rainer Budde, Vom Spiel Der Farbe: Armand Guillaumin (1841–1927) Ein Vergessener Impressionist, exh. cat. (Cologne: Wallraf-Richartz-Museum, 1996), 59.

-

See Catalogue Des Œuvres Importantes De Camille Pissarro Et De Tableaux, Pastels, Aquarelles, Dessins, Gouaches Par Mary Cassatt, Cézanne, Dufeu, Delacroix, Guillaumin, Blanche Hoschedé, Jongkind, Le Bail, Luce, Manet, Claude Monet, Piette, Seurat, Signac, Sisley, van Rysselberghe, etc.: Composant La Collection Camille Pissarro (Paris: Galerie Georges Petit, December 3, 1928), lots 65–66, 77–81.

-

Technical notes by Mary Schafer, NAMA paintings conservator, January 17, 2012, NAMA conservation files.

-

Joachim Pissarro notes at least two paintings Pissarro created in Éragny that he retouched thirteen years later. Girl Tending Cattle on the Banks of the Epte Bazincourt, 1888–1901 (cat. no. 861), is listed under two numbers in Ludovic-Rodo Pissarro’s catalogue raisonné, initially as a distinctly pointillist composition realized in 1888 (PV 718) and again as entirely reworked in 1901 (PV 1205). See Ludovico Rodo Pissarro and Lionello Venturi, Camille Pissarro: Son art, Son œuvre (Paris: Pierre Rosenberg, 1939). As Joachim Pissarro notes, the fact that the artist repainted and re-dated it thirteen years after its initial execution suggests that it was returned to him at some point after it was acquired and before it was given a new date. Joachim Pissarro acknowledges that Camille Pissarro reworked his oils, but only when they remained in his studio. Girl Tending Cattle on the Banks of the Epte Bazincourt is the only instance he was aware of where the painting was “touched up” after leaving the artist’s possession. He also retouched Peasant Woman Chatting in a Farmyard, Éragny, 1889–1902 (cat. no. 868), thirteen years later. While the latter is dated 1895–1902 by the artist, Joachim Pissarro notes that correspondence with Theo van Gogh indicates that it was ready to be sold as early as 1889. Landscape with a Flock of Sheep (cat. no. 873) is double-dated 1889 and 1902; a signature in the bottom right corner (done in 1889) has largely been covered over with a later campaign of paint from 1902. See Pissarro and Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Critical Catalogue of Paintings, 3:564, 568–69, and 573.

-

Paul-Louis Durand-Ruel and Flavie Durand-Ruel, Durand-Ruel et Cie, Paris, to Nicole Myers, NAMA, January 11, 2016, NAMA curatorial file. While we do not know the price Durand-Ruel paid to secure the Nelson-Atkins painting, one can imagine the range based on what he offered the artist for his larger poplars picture on November 22, 1895. The dealer paid the artist 1,250 francs for Poplars, Éragny (1895; Metropolitan Museum of Art). This painting also appeared in the 1896 Durand-Ruel exhibition.

-

Joining the three pictures Durand-Ruel bought in April were two additional Éragny pictures he acquired in November. See Autumn, Poplar Trees, Éragny (1894; Denver Art Museum), and The Poplar Trees, Éragny, Sunlight (1895; Metropolitan Museum of Art); Pissarro and Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Critical Catalogue of Paintings, cat. nos. 1051 and 1082, 3:673, 687.

-

“Jamais ce peintre de la lumière ne fut plus heureux, jamais sa vision plus pénétrante et jamais il n’interpréta avec plus de tendresse les scintillements de la neige aux lueurs du matin ou la matité et la majesté du clocher de village dressant sa silhouette violette dans l’or du couchant” (Never has this painter of light been so felicitous, never has his gaze been so keen, and never has he rendered with such tenderness the sparkle of snow in the glow of early morning, or the muted hue and majesty of the village steeple thrusting its purple silhouette into the gold of the setting sun). L’Art Français, March 10, 1894, cited and translated in Pissarro and Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Critical Catalogue of Paintings, 3:632.

-

See n. 29. Durand-Ruel likely bought the painting for a very low amount due to Pissarro’s weak position from which to negotiate prices.

-

Incidentally, Nelson also acquired Monet’s Snow Effect at Argenteuil (44-1/2) on May 21, 1895, from Durand-Ruel on the same trip.

-

Nelson included a proviso in the museum’s founding documents that trustees could acquire art no fewer than thirty years after an artist’s death, in an effort to prove its lasting value. Michael Churchman and Scott Erbes, High Ideals and Aspirations: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1933–1993 (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1993), 11.

-

While Poplars, Sunset at Éragny caught Nelson’s attention, it did not come to the museum until 1944 as part of his daughter’s residual trust.

Technical Entry

Technical entry forthcoming.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Camille Pissarro, Poplars, Sunset at Eragny, 1894,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.646.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Camille Pissarro, Poplars, Sunset at Eragny, 1894,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.646.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Camille Pissarro, Poplars, Sunset at Eragny, 1894,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.646.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Camille Pissarro, Poplars, Sunset at Eragny, 1894,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.646.4033.

Purchased from the artist by Galerie Durand-Ruel, Paris, stock no. 3222, as Peupliers, soleil couchant, April 10, 1895–May 5, 1896 [1];

Purchased from Durand-Ruel by William Rockhill Nelson (1841–1915), Kansas City, MO, May 5, 1896–April 13, 1915;

To his wife, Ida Nelson (née Houston, 1853–1921), Kansas City, MO, 1915–October 6, 1921;

By descent to her daughter, Laura Kirkwood (née Nelson, 1883–1926), Kansas City, MO, 1921–February 27, 1926;

Inherited by her husband, Irwin Kirkwood (1878–1927), Kansas City, MO, 1926–August 29, 1927;

Laura Nelson Kirkwood Residuary Trust, Kansas City, MO, 1927–June 27, 1944 [2];

Gift of the Laura Nelson Kirkwood Residuary Trust to The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1944.

Notes

[1] See email from Paul-Louis Durand-Ruel and Flavie Durand-Ruel, Durand-Ruel et Cie, Paris, to Nicole Myers, NAMA, January 11, 2016, NAMA curatorial file.

[2] As early as 1927, art advisor to the NAMA trustees, R. A. Holland, noted the painting in the contents of Oak Hall, Nelson’s mansion, as one to keep for the budding museum’s collection; see letter from Fred C. Vincent, Laura Nelson Kirkwood Trustee, to Herbert V. Jones, NAMA Trustee, December 28, 1927, NAMA curatorial files. However, the painting was not given to the museum until Laura Nelson Kirkwood’s household goods and personal effects were finally dispersed in 1944; see letter from Fred C. Vincent, Laura Nelson Kirkwood Trustee, to Ethlyne Jackson, NAMA acting director, June 20, 199, NAMA curatorial files. Just prior to that, the painting was withdrawn from the sale, Catalogue: Laura Nelson Kirkwood Trust of Paintings, Etchings, Antique Furniture, Oriental Rugs, Silverware, Antique War Weapons, and Old Ornaments, Kansas City, 1944, no. 1, as Woodland scene.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Camille Pissarro, Poplars, Sunset at Eragny, 1894,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.646.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Camille Pissarro, Poplars, Sunset at Eragny, 1894,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.646.4033.

Camille Pissarro, Morning Sunlight on the Snow, Éragny-sur-Epte, 1895, oil on canvas, 32 3/8 x 24 1/4 in. (82.3 x 61.6 cm), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; The John Pickering Lyman Collection—Gift of Miss Theodora Lyman, 19.1321.

Camille Pissarro, Poplars, Grey Weather, Éragny, 1895, oil on canvas, 24 x 29 1/4 in. (61 x 74.4 cm), Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto; Bequest of Frederic William Gerald Fitzgerald, 1949, 49/20.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Camille Pissarro, Poplars, Sunset at Eragny, 1894,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.646.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Camille Pissarro, Poplars, Sunset at Eragny, 1894,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.646.4033.

Exposition d’œuvres récentes de Camille Pissarro, Galeries Durand-Ruel, Paris, April 15–May 9, 1896, no. 25, as Peupliers; soleil couchant.

Oak Hall Exhibition, Oak Hall, Kansas City, MO, October 5–9, 1927, no cat.

Memorial Exhibition of the Paintings from the Laura Nelson Kirkwood Collection, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Arts, Kansas City, MO, opened November 18, 1934, no cat.

Exhibition, Winfield, KS, Public Schools, 1942, no cat.

Impressionism: Selections from Five American Museums, The Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, November 4–December 31, 1989; The Minneapolis Institute of Arts, January 27–March 25, 1990; The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, March 21–June 17, 1990; The Saint Louis Art Museum, July 14–September 9, 1990; The Toledo Museum of Art, September 30–November 25, 1990 (Kansas City only), hors cat., as Poplars, Sunset at Ergany.

Among Friends: Guillaumin, Cezanne, and Pissarro, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, January 28, 2021–January 23, 2022, no cat.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Camille Pissarro, Poplars, Sunset at Eragny, 1894,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.646.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Camille Pissarro, Poplars, Sunset at Eragny, 1894,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.646.4033.

Exposition d’œuvres récentes de Camille Pissarro, exh. cat. (Paris: Galeries Durand-Ruel, 1896), 17, as Peupliers; soleil couchant.

“Laura Nelson-Kirkwood,” Kansas City Star 46, no. 164 (February 28, 1926): 1A.

“Oak Hall Open Wednesday,” Kansas City Star 48, no. 15 (October 2, 1927): 2A.

Possibly Paul V. Beckley, “Art News,” Kansas City Journal-Post, no. 193 (December 17, 1933): 2C.

“Art,” Kansas City Star 55, no. 62 (November 18, 1934): 12A.

“Special Lecture Announcement,” News Flashes 1, no. 3 (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) (November 18–December 1, 1934): 1.

M[inna] K. P[owell], “Art: Paintings from Oak Hall Viewed by Public for First Time—A Large Ribera, Several Interesting Dutch Canvases, Portraits of the English School and a Few French Moderns Are Shown,” Kansas City Times 97, no. 277 (November 19, 1934): 8.

Catalogue: Laura Nelson Kirkwood Trust of Paintings, Etchings, Antique Furniture, Oriental Rugs, Silverware, Antique War Weapons, and Old Ornaments (Kansas City: Trustees of the Laura Nelson Kirkwood Trust, 1944), 5, as Woodland scene.

Ross E. Taggart, ed., Handbook of the Collections in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 4th ed. (Kansas City: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1959), 261, as Landscape.

Henry C. Haskell, “Scanning the Arts,” Kansas City Star 85, no. 157 (February 21, 1965): 1D.

Ross E. Taggart and George L. McKenna, eds., Handbook of the Collections in The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Kansas City, Missouri, vol. 1, Art of the Occident, 5th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1973), 258, as Landscape.

Donald Hoffmann, “Out of the Dark and Into the Light: Pissarro Landscape ‘Found’ at Nelson,” Kansas City Star 109, no. 7 (September 25, 1988): 1D, (repro.), as Poplars, Sunset at Eragny.

“New at the Nelson: Museum ‘Discovers’ Pissarro Painting,” Calendar of Events (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (October 1988): 1–3, (repro.), as Poplars, Sunset at Eragny.

Michael Churchman and Scott Erbes, High Ideals and Aspirations: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1933–1993 (Kansas City: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1993), 34, as Poplars, Sunset at Eragny.

Bernard Denvir, Chronicle of Impressionism: An Intimate Diary of the Lives and World of the Great Artists (London: Thames and Hudson, 1993), 279.

Roger Ward and Patricia J. Fidler, eds., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collections (New York: Hudson Hills Press, in association with Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1993), 12, 212, (repro.), as Poplars, Sunset at Eragny.

Kristie C. Wolferman, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: Culture Comes to Kansas City (Columbia, MO: Columbia University of Missouri Press, 1993), 186–88, (repro.), as Morning, Sunlight on the Snow, Eragny.

“Know your Museum Tour ‘Let the Sun Shine In!,’” Newsletter (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (Winter 2003): 10, (repro.), as Poplars, Sunset at Eragny.

Joachim Pissarro and Claire Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Catalogue critique des peintures; Critical Catalogue of Paintings (Paris: Wildenstein Institute Publications, 2005), no. 1056, pp. 1:364, 3:675, (repro.), as Peupliers à Eragny, soleil couchant.

Deborah Emont Scott, ed., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collection, 7th ed. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2008), 125, (repro.), as Poplars, Sunset at Eragny.

Possibly Cornelia Homburg et al., Vincent Van Gogh: Timeless Country, Modern City, exh cat. (Milano: Skira, 2010).

Claire Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Camille Pissarro, Rouen: Peindre la ville (Rouen: Éditions point de vues, 2013), 133, as Peupliers, soleil couchant.

Catherine Futter et al., Bloch Galleries: Highlights from the Collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2016), 97, (repro.), as Poplars, Sunset at Eragny.

David Scott Kastan, On Color (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018), 142, (repro.), as Poplars, Sunset at Eragny.