![]()

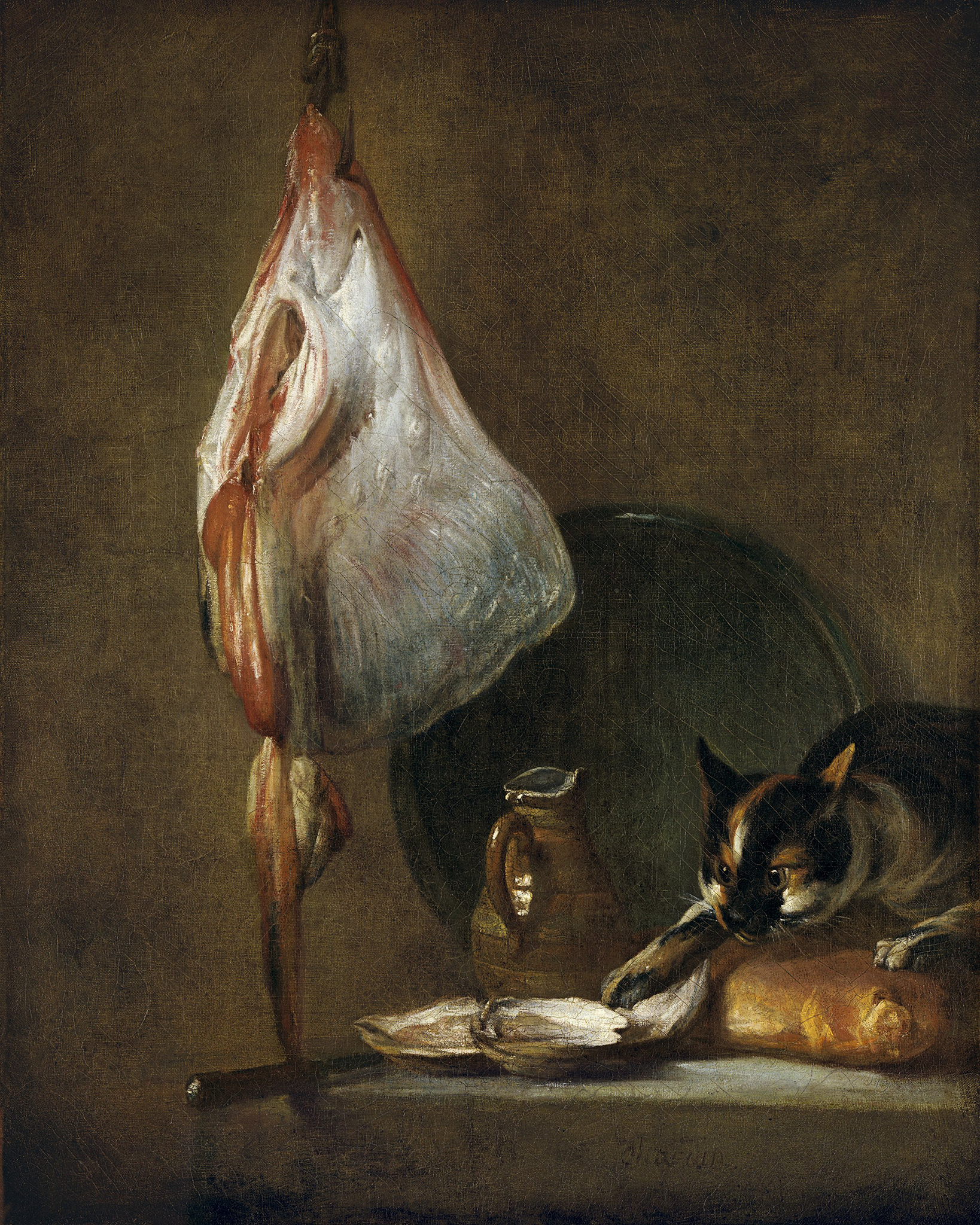

Jean Siméon Chardin, Still Life with Cat and Fish, 1728

| Artist | Jean Siméon Chardin, French, 1699–1779 |

| Title | Still Life with Cat and Fish |

| Object Date | 1728 |

| Alternate and Variant Titles | La Table de Cuisine; L’Office; The Lucky Thief; Le Larron en bonne fortune; Cat with Herrings; Les Harengs avec Chat |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (Unframed) | 31 1/2 x 25 1/4 in. (80 x 64.1 cm) |

| Signature | Signed lower center: Chardin [f ?] |

| Credit Line | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Purchase: acquired through the generosity of an anonymous donor, F79-2 |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Richard Rand, “Jean Siméon Chardin, Still Life with Cat and Fish, 1728,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.310.5407.

MLA:

Rand, Richard. “Jean Siméon Chardin, Still Life with Cat and Fish, 1728,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.310.5407.

Still Life with Cat and Fish exemplifies Jean Siméon Chardin’s early style, when he first emerged as one of the most brilliant painters of his generation. The picture is datable to 1728, the year he was accepted into the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture as a “painter of animals and fruits.” Chardin pursued this humblest of genres, later adding scenes of daily life to his repertoire, and he continued to paint them for the rest of his career. He won the acclaim of collectors and critics for his astonishing technical abilities and keen powers of observation and pictorial mimesis during a time when academic doctrine ranked “history painting” (subjects drawn from biblical and classical literature) as an artist’s highest calling.1Philip Conisbee, Chardin (Oxford, England: Phaidon, 1986), 35–52.

Like many of Chardin’s early still lifes, the Kansas City painting depicts the commonest of everyday objects displayed matter-of-factly along a rough stone shelf before a plain brown wall: a cut of salmon, placed so that its pink flesh faces the viewer, lies atop the ceramic lid of a pot; a scallion hangs tantalizingly over the edge, its bulb seeming to break the foreground plane; three mussels and a piece of fruit rest next to the scallion; while a pair of fish—they can be identified as hake, although they have also been called herring and mackerel—hang from a hook suspended from above.2Specifically, European hake (Merluccius merluccius), rather than mackerel or herring, as some scholars have suggested; see Pierre Rosenberg, Chardin, exh. cat. (Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1999), 131, and see also Pierre Rosenberg, Tout l’œuvre peint de Chardin (Paris: Flammarion, 1983), 75. Chardin animated the composition by introducing a lively calico cat that paws at the salmon and looks intently at something outside the canvas. These mundane objects are brought together by the artist with an exquisite sense of pictorial balance and energy, as the viewer’s eye is led across the composition and in and out of the shallow space. Chardin placed the stone shelf at a slight angle to the horizontal axis of the canvas, introducing a subtle dynamism to the play of forms, colors, and textures. The general composition and the warm tonalities demonstrate the influence that seventeenth-century Dutch still lifes had on Chardin’s art at this time.

Fig. 2. Jean Siméon Chardin, Still Life With Cat and Fish, 1728, oil on canvas, 31 5/16 x 24 3/16 in. (79.5 x 63 cm), Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, inv. no. 119 (1986.3)

Fig. 2. Jean Siméon Chardin, Still Life With Cat and Fish, 1728, oil on canvas, 31 5/16 x 24 3/16 in. (79.5 x 63 cm), Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, inv. no. 119 (1986.3)

Fig. 3. Jean Siméon Chardin, Still Life With Cat and Rayfish, 1728, oil on canvas, 31 5/16 x 24 3/16 in. (79.5 x 63 cm), Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, inv. no. 120 (1986.6)

Fig. 3. Jean Siméon Chardin, Still Life With Cat and Rayfish, 1728, oil on canvas, 31 5/16 x 24 3/16 in. (79.5 x 63 cm), Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, inv. no. 120 (1986.6)

Of the four paintings now in Madrid, Glasgow, and Kansas City, only the Madrid version of Still Life with Cat and Fish is dated (1728).10Wildenstein had read the date on the Thyssen painting (then in the Rothschild collection) as 1758, further confusing matters; but Rosenberg established that the correct reading is 1728. Rosenberg, “A Chardin for Kansas City,” 20–36. Stylistically, the version at the Nelson-Atkins fits easily into this period of Chardin’s production. According to Rosenberg and supported by recent provenance research by Glynnis Stevenson, the earliest known owner of the Kansas City and Glasgow paintings was probably Armand Frédéric Ernest Nogaret (1734–1806), treasurer to the comte d’Artois before the French Revolution, whose collection was auctioned in Paris in 1807. The two Madrid versions, which Rosenberg deems likely to have been painted first, may be associated with those in the collection of M. Rémond, formerly the maître d’hôtel du roi (head of the king’s royal household), whose collection sold in Paris in 1778. The descriptions in the corresponding auction catalogues are vague enough, however, that it is difficult to be certain to which pair they refer.11Rosenberg, “A Chardin for Kansas City,” 27; “[No.] 74. Deux tableaux sur toile, chacun de 30 pouces de haut, sur 20 de large; dans l’un on voit une raye, des huîtres et un chat; dans l’autre un chat, de la raye et deux merlans” in Pierre Rémy, Catalogue de Tableaux Originaux des Grands Maîtres Des Écoles d’Italie, des Pays-Bas, et de France, après décès de M. Rémond, ancien Maître-d’Hôtel du Roi Louis XV (Paris: Musier, July 6, 1778), 26; and “[No.] 5 Chardin. Divers poisons et un chat. [No.] 6 [Chardin]. Autre tableau du même genre faisant pendant au précédant,” in Catalogue des Tableaux, Dessins, Marbres, Bronzes et Autres Objets d’Arts, Provenans [sic] du Cabinet de feu M. Armand-Frédéric-Ernest Nogaret, ancien Trésorier du ci-devant Comte d’Artois, etc. ([Paris: Thierry et Langlier, 1807]), 1. The painting in the Rémond collection was purchased by the dealer Jacques Langlier, who later drew up Nogaret’s posthumous inventory and hosted the sale of his collection in 1807. The dealer is the likely link between the two collectors, meaning that the Nelson-Atkins painting may actually be the one in the 1778 sale.

It has been said that Chardin “can and often does make a story out of the contents of a shopping bag.”12Michael Baxandall, Patterns of Intention: On the Historical Explanation of Pictures, 2nd ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986), 102. At the Beurnonville sale in Paris in 1881, the Madrid version was entitled The Lucky Thief, the cataloguer explaining that “a cat with red-and-tan tortoiseshell fur had slipped into the kitchen pantry.”13“Le Larron en bonne fortune. C’est un chat au pelage moucheté de fauve et de roux qui s’est glissé dans le garde-manger”; quoted in Rosenberg “A Chardin for Kansas City,” 22. Such amusing scenarios aside, one might wonder if Chardin intended any specific meaning in this particular grouping of cat, fish, vegetable, and fruit. The suspended hake—or herring—and the scallion (as well as the mortar and pestle in the Thyssen version) also appear in a still life of 1731 that has traditionally been titled The Fast-Day Meal, a pair to The Meat-Day Meal (both Musée du Louvre, Paris), but these references to the Lenten period in the Catholic calendar may not have been Chardin’s original concept.14Rosenberg, Tout l’œuvre peint de Chardin, nos. 54 and 55. See Conisbee, Masterpiece in Focus, 92–94. It would be difficult to accommodate the fruit (a peach?) in this reading. Cats, fish, and scallions all carried sexual connotations in Chardin’s day, as in earlier European eras.15See, for example, Sheila McTighe, “Foods and the Body in Italian Genre Paintings, about 1580: Campi, Passarotti, Carracci,” Art Bulletin 86, no. 2 (June 2004): 301–23, esp. 317–18. Longstanding superstition has associated cats with witchcraft and other magical powers, as well as with fertility and female sexuality (calico cats are nearly always female).16Robert Darnton, The Great Cat Massacre and Other Episodes in French Cultural History (New York: Basic Books, 1984), 92–96. On the sex of calico cats, see Michael W. Fox, “Domestic cat,” Encyclopædia Britannica (December 06, 2016): https://www.britannica.com/animal/cat; and Le Chevalier de Jaucourt, “Chat,” Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire Raisonné des Sciences, des Arts et des Métiers., ed. Diderot (1753; repr., Stuttgart: Friedrich Frommann Verlag, 1988), 3:235: “On sait que les chats sont de différentes couleurs; [. . . ] même de trois couleurs, noirs, roux, & blancs, que l’on nomme par cette raison tricolors. J’ai oüi dire qu’il n’y avoit aucun chat mâle de trois couleurs.” By including the calico cats so prominently in both the Kansas City and Glasgow paintings (and in the associated versions in Madrid), Chardin may have sought to draw upon such popular notions; he was not averse to depicting animals in allegorical guises (such as his various representations of monkeys as painters, les singes-peintres). He once painted a picture (now lost) that included a monkey, a dog, a cat, and crayfish, a grouping that remains mysterious.17See Rosenberg, Tout l’œuvre peint de Chardin, no. 28; on the singes-peintres, see ibid., nos. 23, 24a, 93, and 94.

That said, the cats in the Nelson-Atkins painting and its related compositions strike a more straightforward, decidedly un-symbolic, pose: brilliantly observed and naturalistically rendered by the artist, these creatures are as much a part of the everyday life of the kitchen as the simple fish, the mundane vegetables and fruits, and the kitchenware. (The glass vinegar pitcher and the faience or porcelain bowl in the Glasgow painting and the mortar and pestle in Thyssen’s picture were common in many households.) They reinforce and vividly evoke the satisfying believability of the still-life composition. In the article on cats written for the Encyclopédie—the great project of the Enlightenment that sought to employ reason and scientific analysis to cut through centuries-old layers of superstition and dogma—the chevalier de Jaucourt avoided any commentary on cat folklore, reserving his discussion to matters of feline life cycle and anatomy, including questions such as why cats hate water or why, when dropped from high places, they land on their feet. Like Chardin’s convincing representations, Jaucourt’s descriptions of cats are based in clear-eyed observation: “Everyone knows that cats chase rats and birds; for they climb trees and jump with the greatest of agility, and they use cunning with notable dexterity. It is said that they are very fond of fish.”18Le Chevalier de Jaucourt, “Chat,” Encyclopédie, 234: “Tout le monde sait que les chats donnent la chasse aux rats & aux oiseaux; car ils grimpent sur les arbres, ils sautent avec une très-grande agilité, & ils rusent avec beaucoup de dextérité. On dit qu’ils aiment beaucoup le poisson.”

Notes

-

Philip Conisbee, Chardin (Oxford, England: Phaidon, 1986), 35–52.

-

Specifically, European hake (Merluccius merluccius), rather than mackerel or herring, as some scholars have suggested; see Pierre Rosenberg,Chardin, exh. cat. (Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1999), 131, and see also Pierre Rosenberg, Tout l’œuvre peint de Chardin (Paris: Flammarion, 1983), 75.

-

Rosenberg, Tout l’œuvre peint de Chardin, no. 30A, p. 75.

-

This was true of his still lifes in particular but also of his genre paintings; see Philip Conisbee, Masterpiece in Focus: “Soap Bubbles” by Jean-Siméon Chardin, exh. cat. (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1990), 7.

-

Rosenberg, Tout l’œuvre peint de Chardin, nos. 29 and 30, p. 75.

-

Georges Wildenstein, Chardin: Biographie et Catalogue Critiques, l’Œuvre Complet de l’Artiste Reproduit en Deux Cent Trente-Huit Héliogravures (Paris: Les Beaux-arts, Édition d’études et de documents, 1933). The Thyssen paintings are nos. 679 and 683, pp. 206–07; the Glasgow and Kansas City paintings are on the same page, nos. 680 and 683 bis. The quoted passage in the original French is “douteux ou faux, ou que nous n’avons pas vus” on page 154, where Wildenstein discusses his cataloguing system: “[catalogue entries] dont les titres sont en simples italiques sont ceux que nous considérons comme douteux ou faux, ou que nous n’avons pas vus et sur lesquels des témoignages indiscutables ne nous ont pas été fournis.”

-

Pierre Rosenberg, “A Chardin for Kansas City,” trans. Ursula Korneitchouk, Bulletin (The Nelson Gallery and Atkins Museum) 5, no. 6 (January 1981): 20–36.

-

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, project assistant at the Nelson-Atkins, observes that another variation of the Glasgow picture was sold from the posthumous Pierre Decourcelle sale on May 29–30, 1911. Wildenstein also assumed this picture to be a forgery, but the slight shift of the silver salver leaning against the back wall and altered dimensions show an artist tweaking himself rather than the work of a forger. Wildenstein, Chardin: Biographie et Catalogue Critiques, no. 681.

-

There are third variants of each composition (the variant corresponding to the Kansas City painting has been cut to a horizontal format) that Rosenberg considers to be old copies; significantly, these are exact copies without any alterations; see Rosenberg, Tout l’œuvre peint de Chardin, p. 75, nos. 29b and 30b.

-

Wildenstein had read the date on the Thyssen painting (then in the Rothschild collection) as 1758, further confusing matters; but Rosenberg established that the correct reading is 1728. Rosenberg, “A Chardin for Kansas City,” 20–36.

-

Rosenberg, “A Chardin for Kansas City,” 27; “[No.] 74. Deux tableaux sur toile, chacun de 30 pouces de haut, sur 20 de large; dans l’un on voit une raye, des huîtres et un chat; dans l’autre un chat, de la raye et deux merlans” in Pierre Rémy, Catalogue de Tableaux Originaux des Grands Maîtres Des Écoles d’Italie, des Pays-Bas, et de France, après décès de M. Rémond, ancien Maître-d’Hôtel du Roi Louis XV (Paris: Musier, July 6, 1778), 26; and “[No.] 5 Chardin. Divers poisons et un chat. [No.] 6 [Chardin]. Autre tableau du même genre faisant pendant au précédant,” in Catalogue des Tableaux, Dessins, Marbres, Bronzes et Autres Objets d’Arts, Provenans [sic] du Cabinet de feu M. Armand-Frédéric-Ernest Nogaret, ancien Trésorier du ci-devant Comte d’Artois, etc. ([Paris: Thierry et Langlier, 1807]), 1. The painting in the Rémond collection was purchased by the dealer Jacques Langlier, who later drew up Nogaret’s posthumous inventory and hosted the sale of his collection in 1807. The dealer is the likely link between the two collectors, meaning that the Nelson-Atkins painting may actually be the one in the 1778 sale.

-

Michael Baxandall, Patterns of Intention: On the Historical Explanation of Pictures, 2nd ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986), 102.

-

“Le Larron en bonne fortune. C’est un chat au pelage moucheté de fauve et de roux qui s’est glissé dans le garde-manger”; quoted in Rosenberg “A Chardin for Kansas City,” 22.

-

Rosenberg, Tout l’œuvre peint de Chardin, nos. 54 and 55. See Conisbee, Masterpiece in Focus, 92–94.

-

See, for example, Sheila McTighe, “Foods and the Body in Italian Genre Paintings, about 1580: Campi, Passarotti, Carracci,” Art Bulletin 86, no. 2 (June 2004): 301–23, esp. 317–18.

-

Robert Darnton, The Great Cat Massacre and Other Episodes in French Cultural History (New York: Basic Books, 1984), 92–96. On the sex of calico cats, see Michael W. Fox, “Domestic cat,” Encyclopædia Britannica (December 06, 2016): https://www.britannica.com/animal/cat; and Le Chevalier de Jaucourt, “Chat,” Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire Raisonné des Sciences, des Arts et des Métiers, ed. Diderot (1753; repr., Stuttgart: Friedrich Frommann Verlag, 1988), 3:235: “On sait que les chats sont de différentes couleurs; [. . . ] même de trois couleurs, noirs, roux, & blancs, que l’on nomme par cette raison tricolors. J’ai oüi dire qu’il n’y avoit aucun chat mâle de trois couleurs.”

-

See Rosenberg, Tout l’œuvre peint de Chardin, no. 28; on the singes-peintres, see ibid., nos. 23, 24a, 93, and 94.

-

Le Chevalier de Jaucourt, “Chat,” Encyclopédie, 234: “Tout le monde sait que les chats donnent la chasse aux rats & aux oiseaux; car ils grimpent sur les arbres, ils sautent avec une très-grande agilité, & ils rusent avec beaucoup de dextérité. On dit qu’ils aiment beaucoup le poisson.”

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Diana M. Jaskierny, “Jean Siméon Chardin, Still Life with Cat and Fish, 1728,” technical entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.310.2088.

MLA:

Jaskierny, Diana M. “Jean Siméon Chardin, Still Life with Cat and Fish, 1728,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.310.2088.

Still Life with Cat and Fish by Jean Siméon Chardin (1699–1779) was completed early in the artist’s career, along with a closely related version in the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid (Fig. 2), painted in the same year. The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art painting was executed on a medium weight canvas with cuspingcusping: A scalloped pattern along the canvas edges that relates to how the canvas was stretched. Primary cusping reveals where tacks secured the canvas to the support while the ground layer was applied. Secondary cusping can form when a pre-primed canvas is re-stretched by the artist prior to painting. present on all four sides.1Although the tacking margins were removed when the painting was lined, cusping is visible along the edges of the picture plane and in x-radiography.

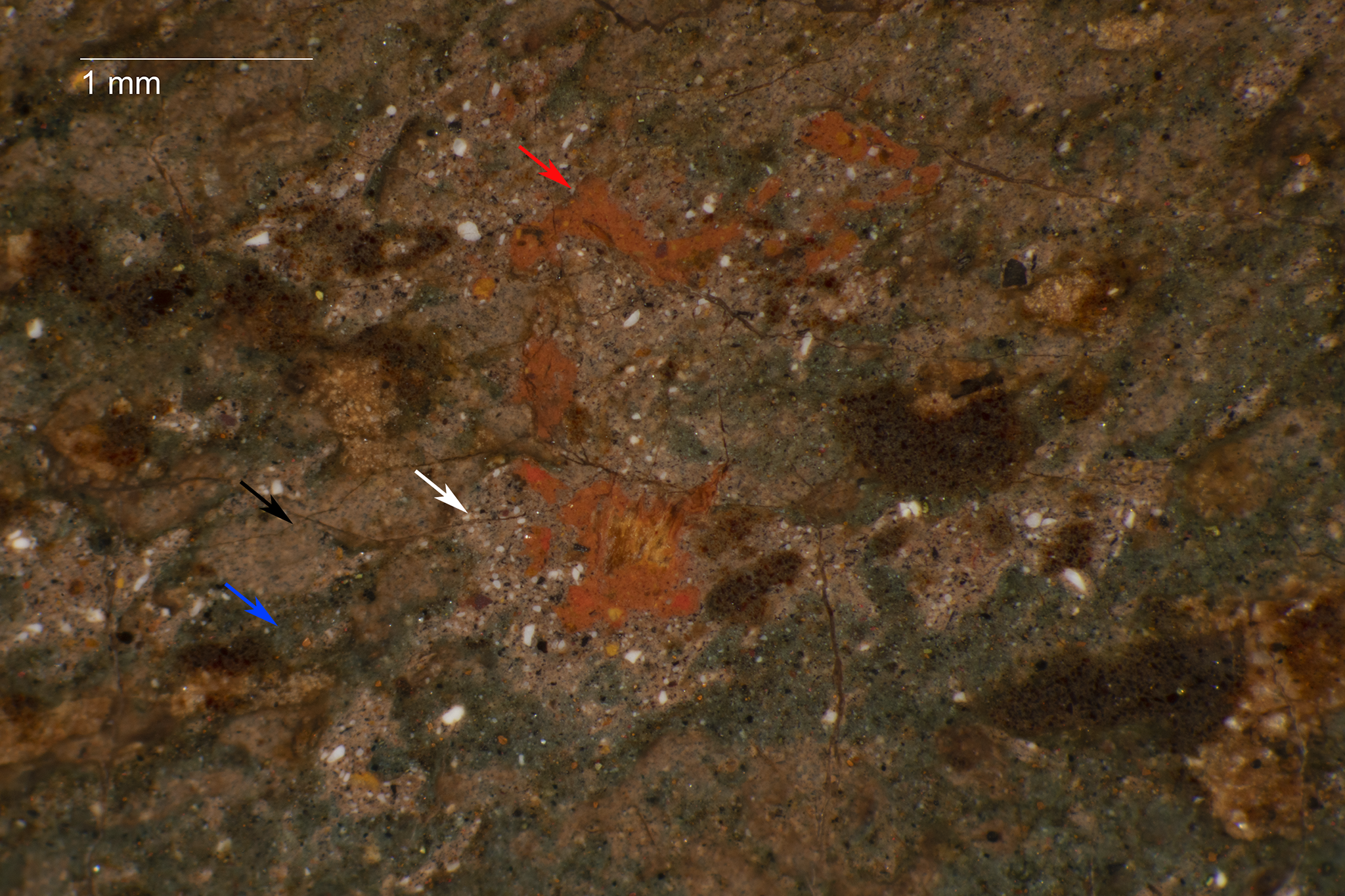

An underpaintingunderpainting: The first applications of paint that begin to block in color and loosely define the compositional elements. Also called ébauche., cool gray in tone, was evenly applied across the upper two-thirds of the painting, appearing to end where the ledge’s top and front meet (Fig. 5). While the red ground layer does not appear to be intentionally visible in any part of the composition, the gray ground layer and gray underpainting emerge between some compositional elements, producing subtle neutral-warm and cool tones where visible.

Fig. 5. Photomicrograph illustrating where the cool gray underpainting (top) ends at the ledge front (bottom), Still Life with Cat and Fish (1728)

Fig. 5. Photomicrograph illustrating where the cool gray underpainting (top) ends at the ledge front (bottom), Still Life with Cat and Fish (1728)

Fig. 6. Rapid zig-zag brushwork in the left background, with the thinly painted upper blue layer revealing the lower gray layer, Still Life with Cat and Fish (1728)

Fig. 6. Rapid zig-zag brushwork in the left background, with the thinly painted upper blue layer revealing the lower gray layer, Still Life with Cat and Fish (1728)

Fig. 7. Detail illustrating how the application of blue background paint relates to the placement of the fish, Still Life with Cat and Fish (1728)

Fig. 7. Detail illustrating how the application of blue background paint relates to the placement of the fish, Still Life with Cat and Fish (1728)

Fig. 8. Detail of the cat’s tail, illustrating Chardin’s use of background paint as the lower layer of the tail, Still Life with Cat and Fish (1728)

Fig. 8. Detail of the cat’s tail, illustrating Chardin’s use of background paint as the lower layer of the tail, Still Life with Cat and Fish (1728)

Fig. 10. Detail of the rapid brushwork in the cat’s fur, Still Life with Cat and Fish (1728)

Fig. 10. Detail of the rapid brushwork in the cat’s fur, Still Life with Cat and Fish (1728)

Fig. 11. Detail of the cat’s face and fur, Still Life with Cat and Fish (1728)

Fig. 11. Detail of the cat’s face and fur, Still Life with Cat and Fish (1728)

The painting is in very good condition overall. The canvas was glue-paste linedlining: A procedure used to reinforce a weakened canvas that involves adhering a second fabric support using adhesive, most often a glue-paste mixture, wax, or synthetic adhesive. prior to its history at the Nelson-Atkins, and the painting has not been treated since entering the collection. There is minimal retouchingretouching: Paint application by a conservator or restorer to cover losses and unify the original composition. Retouching is an aspect of conservation treatment that is aesthetic in nature and that differs from more limited procedures undertaken solely to stabilize original material. Sometimes referred to as inpainting or retouch. visible when examined with ultraviolet (UV) radiationultraviolet (UV) radiation: A segment of the electromagnetic spectrum, just beyond the sensitivity of the human eye, with wavelengths ranging from 100–400 nanometers. For a description of its use in the study of art objects, see ultraviolet (UV) fluorescence or UV-induced visible fluorescence., with the exception of the left and bottom edges and a few isolated locations within the picture plane. Based on the UV-induced fluorescenceultraviolet (UV) fluorescence or UV-induced visible fluorescence: The reflected visible light produced when painting materials interact with ultraviolet (UV) radiation. Not all materials fluoresce, but the color and intensity of the fluorescence is frequently used to differentiate between original and restoration materials, characterize the varnish layers, or reveal the distribution of pigments across the composition., it appears the painting has a natural resin varnish with an overlying synthetic varnish.15The varnish produces an overall yellow-green UV-induced fluorescence that is indicative of natural resin. There is also a coating that fluoresces pale blue, likely indicating an early synthetic varnish, that is unevenly applied over the cat, the left background, and the tabletop.

Notes

-

Although the tacking margins were removed when the painting was lined, cusping is visible along the edges of the picture plane and in x-radiography.

-

The left edge of the picture plane has been retouched, preventing identification of lower layers. However, losses near the left edge confirm the presence of the red ground layer along this side.

-

No samples were taken during this examination; however, technical examinations of other Chardin paintings have found similar stratigraphy and identified a red ochre ground and gray upper preparatory layer. Humphrey Wine, The Eighteenth Century French Paintings (London: National Gallery Company, 2018), 106. See also Sandra Webster-Cook, Kate Helwig, and Lloyd de Witt, “The Research and Conservation Treatment of Jar of Apricots / Le Bocal d’abricots, 1758 by Jean-Siméon Chardon,” AIC Paintings Specialty Group Postprints 26 (2013): 3–4.

-

This depth or “vibrancy” has been noted in other Chardin backgrounds, such as Soap Bubbles (after 1739; Los Angeles County Museum of Art). Joseph Fronek, “The Materials and Techniques of the Los Angeles Soap Bubbles,” in Masterpiece in Focus: Soap Bubbles by Jean-Siméon Chardin (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1990), 23.

-

Philip Conisbee, Painting in Eighteenth-Century France (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1981), 162.

-

Georges Wildenstein, Chardin, trans. Daniel Wildenstein (Oxford: Bruno Cassirer, 1969), 21n1.

-

John Goodman, ed. and trans., Diderot on Art, vol. 1, The Salon of 1765 and Notes on Painting (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 64.

-

Harmony within his compositions was of great interest to Chardin. Studies of his paintings indicate he used a select number of pigments. By doing so, a relationship was formed throughout the composition. In Still Life with Cat and Fish, the same general pigments appear to be used as those found by other institutions. Examination was completed with a stereomicroscope. No pigment analysis was conducted during this examination. F. Schmid, “The Painter’s Implements in Eighteenth-century Art,” Burlington Magazine 108, no. 763 (1966): 519. For more analysis of Chardin’s palette, see also Ross Merrill, “A Step Toward Revising Our Perception of Chardin” in AIC Preprints, American Institute for Conservation, 9th Annual Meeting, Philadelphia (Washington, DC: American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works, 1981), 123–28.

-

Few preparatory drawings exist by Chardin, and it is believed that he preferred to paint directly from observation. Philip Conisbee, Soap Bubbles by Jean-Siméon Chardin (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1990), 6.

-

Philip Conisbee, Chardin (Oxford: Phaidon, 1986), 84–88.

-

Film-based x-radiograph no. 142, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, F79-2.

-

Chardin often created compositions in duplicates, with later versions having few pentimenti as he progressed. It is possible that this composition originated with a now lost sketch or that the Thyssen-Bornemisza painting was the earlier version. Philip Conisbee, Soap Bubbles by Jean-Siméon Chardin, 16.

-

Marianne Roland Michel, Chardin (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1996), 134. See also Ross Merrill, “A Step Toward Revising Our Perception of Chardin,” 123.

-

Sarah Catala, Chardin Still Life with Peaches (Paris: Galerie Éric Coatalem, 2016), 10.

-

The varnish produces an overall yellow-green UV-induced fluorescence that is indicative of natural resin. There is also a coating that fluoresces pale blue, likely indicating an early synthetic varnish, that is unevenly applied over the cat, the left background, and the tabletop.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Jean Siméon Chardin, Still Life with Cat and Fish, 1728,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.310.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Jean Siméon Chardin, Still Life with Cat and Fish, 1728,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.310.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Jean Siméon Chardin, Still Life with Cat and Fish, 1728,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.310.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Jean Siméon Chardin, Still Life with Cat and Fish, 1728,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.310.4033.

Probably Georges Alexis Bertrand Rémond (d. 1778), Saint-Julien-les-Villas, France, by May 3, 1778;

Probably purchased at his posthumous sale, Tableaux Originaux des Grands Maîtres Des Écoles d’Italie, des Pays-Bas, et de France, après décès de M. Rémond, ancien Maître-d’Hôtel du Roi Louis XV, rue Villedot, Paris, July 6, 1778, no. 74, as Deux tableaux sur toile, chacun de 30 pouces de haut, sur 20 de large; dans l’un on voit une raye, des huîtres et un chat; dans l’autre un chat, de la raye et deux merlans, by the dealer Jacques Langlier, Paris, 1778;

Probably Armand Frédéric Ernest Nogaret (1734–1806), by July 21, 1806 [1];

Probably purchased at his posthumous sale, Tableaux, Dessins, Marbres, Bronzes et Autres Objets d’Arts: Provenans du Cabinet de feu M. Armand-Frédéric-Ernest Nogaret, ancien Trésorier du ci-devant Comte d’Artois, etc., chez M. Thierry, chez MM. Jacques et Antoine Langlier, and hôtel de Gesvres, Paris, April 6, 1807, no. 5 or 6, as Divers poissons et un chat or Autre tableau de même genre, faisant pendant du précédent, by an unknown buyer;

Dominique Vincent Ramel-Nogaret (called Ramel de Nogaret, 1760–1829), Montolieu, Aude, Languedoc-Roussillon, France, by 1816 [2];

Transferred to his brother-in-law, Jean Antoine Bories (1763–1848), Montolieu, Aude, Languedoc-Roussillon, France, 1816–July 17, 1848 [3];

By descent to his son, Jacques-Pierre-François Bories (1819–1886), Montolieu, Aude, Languedoc-Roussillon, France, 1848–1865;

Purchased from Jacques-Pierre-François Bories by Charles Philippe Adolphe (1822–1890), baron Lepic, Poitiers and Montolieu, Aude, Languedoc-Roussillon, France, 1865–May 11, 1890 [4];

Possibly inherited by his wife, Claire Lepic (née Dauphole, 1836–1907), 1890–1897;

Purchased at Lepic’s posthumous sale, Beaux Meubles Louis XV et Louis XVI en laque et en marqueterie, enrichis de cuivres ciselés; Consoles et Glaces; Fauteuils en Tapisserie; Pendules et Appliques; Faïences françaises, Porcelaines, Jades et Objets varies; Tenture Chinoise en Soie peinte; et des Tableaux Anciens par Breughel de Velours, Chardin, Desportes, De Troy, Van der Meulen, J.-B. Oudry, Rigaud, et tout provenant de la Collection de Feu M. le Baron Lepic , Galerie Georges Petit, Paris, June 18, 1897, no. 7, as L’Office, by [Armand] Levy [5];

Sigismond Bardac (1856–1919), Paris, by 1908–at least 1911 [6];

Alphonse Kann (1870–1948), Paris, no later than December 6, 1920;

Purchased at his sale, Catalogue des Tableaux–Dessins–Pastels, Principalement du XVIIIe siècle des Écoles Anglaise, Française et Italienne, Sculptures du XVIIIe Siècle En Marbre, Terre-cuite, Plâte, Bronze; Objets d’Art et d’Ameublement; Porcelaines et Matières dure montées en bronze, Orfèvrerie, Bois sculptés, Cadres, Gaînes, Poêle en faïence, Objets divers; Bronzes d’Ameublement, Pendules; Appliques, Baromètres, Cadres, Chenets, Candélabres, Flambeaux, etc.; Sieges et Meubles En Bois sculpté, Bois doré et Marqueterie, la plupart signés des Maîtres-Ebénistes du XVIIIe Siècle, Paravent, Ecrans et Sièges en tapisserie et savonnerie, etc. Composant la Collection de M. A. Kann , Galerie Georges Petit, Paris, December 6–8, 1920, no. 9, as Les harengs, probably by Arthur (1870–1936) and Hedy (1873–1952) Hahnloser–Bühler, Winterthur, Switzerland, 1920–no later than 1952 [7];

By descent to their son, Hans Robert Hahnloser (1899–1974), Bern, Switzerland, by July 7, 1951–no later than 1964 [8];

Purchased from Hahnloser by E. V. Thaw, New York, by 1974 [9];

Purchased from David Carritt, Ltd., London, and E. V. Thaw, New York, by The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1979.

Notes

[1] The Chardin pendants are in Nogaret’s posthumous inventory drawn up by the dealer Jacques Langlier (1732–1814) and the deceased’s heir, Dominique-Vincent Ramel-Nogaret (called Ramel de Nogaret). “Inventaire après décès d’Armand NOGARET, 21 juillet 1806,” Archives nationales, Paris, MC/ET/CXV/1075. The description of the painting is not definitive enough to undisputedly claim it is the Nelson-Atkins painting. However, Langlier was the likely link between the Rémond sale, where the dealer was the buyer, and the Nogaret collection. The provenance of the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza related pendant pair, which claims Rémond and Nogaret as constituents, is based on Georges Wildenstein’s catalogues raisonnés of 1933 and 1969, but Nelson-Atkins research revealed this to be incorrect.

[2] Ramel de Nogaret was the heir of Armand Nogaret, but he did not inherit all of Armand’s art collection. It is likely that Ramel de Nogaret purchased the paintings by Chardin, as well as by Desportes, and Oudry, from the 1807 posthumous Nogaret sale. Later, these still lifes definitively appear in the collection of Baron Lepic, who had purchased the collection once owned by Ramel de Nogaret in 1865. The Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza claims their related pendant pair was in the 1807 posthumous sale based on the Georges Wildenstein catalogues raisonnés of 1933 and 1969, but Nelson-Atkins research revealed this to be incorrect.

[3] In 1816, Ramel de Nogaret and his wife were exiled to Belgium by the restored Bourbon regime for his role in the Directory and his support of the reign of Emperor Napoleon I. He was forced to transfer his property in Montolieu to Bories, his brother-in-law. See M. [Alphonse Jacques] Mahul, Cartulaire et Archives des Communes de l’ancien diocese et de l’arrondissment administrative de Carcassone (Paris: Didron, 1857), 1:153, where Bories is listed as the inheritor of “Petit Versailles” in 1816. Bories’ son was listed as the owner of the property in 1857.

[4] See the preface of the June 18, 1897 sales catalogue. Reproductions in the catalogue show that the paintings in the Lepic sale are unmistakably the Nelson-Atkins and Glasgow pictures. See also Pierre Rosenberg, “A Chardin for Kansas City,” trans. Ursula Korneitchouk, Bulletin (The Nelson Gallery and Atkins Museum) 5, no. 6 (January 1981): 28.

[5] See the handwritten annotation, “Levy”, in the sales catalogue housed at the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris. This is presumably Armand Levy, a Parisian art dealer who was also active on the city’s musical scene.

[6] See Jean Guiffrey, Catalogue raisonné de l’œuvre peint et dessiné de J.-B. Siméon Chardin (1699–1769), Suivi de la liste des gravures exécutées d’après ses ouvrages (Paris: Imprimerie G. Kadar, 1908), 96, which is the earliest text to identify Bardac as the owner of both the Nelson-Atkins and Glasgow pictures. Bardac and Levy are cited together in one account of the provenance of the painting by Circle of Jacques–Louis David, Portrait of a Young Woman in White, ca. 1798, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, thereby hinting that Levy may have sold the Nelson-Atkins painting to Bardac.

[7] According to a photo sheet from the Duits collection at the Getty Research Institute, the painting was purchased at the 1920 sale by “Hambloser.” This is probably a misspelling of Hahnloser, since Arthur and Hedy Hahnloser owned the painting at the time of the 1940 Die Hauptwerke der Sammlung Hahnloser, Winterthur exhibition in Lucerne. See The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, Photo Archive, French, Chardin, Jean Baptiste-Simeon (1699–1779), Paintings, Still Life cont., 76.P.55, Box 231. Dr. Margrit Hahnloser-Ingold does not deny that Hedy Hahnloser-Bühler was the buyer at the 1920 sale; see email from Dr. Margrit Hahnloser-Ingold to Glynnis Napier Stevenson, NAMA, July 23, 2020, NAMA curatorial files.

[8] A verso label for the exhibition De Watteau à Cezanne, Musée d’art et d’histoire, Geneva, July 7–September 30, 1951, lists “Madame H. Hahnloser / Tösstalstrasse 42 / Wintherthour [sic]” as the lender. However, a pen inscription corrects this to list “Hans-Bernhard / Hahnloser / Bern” as the lender.

See emails from Dr. Margrit Hahnloser-Ingold to MacKenzie Mallon, NAMA, March 13, 2014, and to Glynnis Napier Stevenson, NAMA, July 23, 2020, NAMA curatorial files, where she states that Hans Hahnloser gave the painting to a dealer named Burchard and confirms that Burchard came from Egypt. This is probably the Swiss painter and dealer Irmgard Micaela Burchard Simaika (1908–1964). She married the Egyptian mathematician, Jacques Boulos Simaika (1914–1994), in 1952, and moved to Cairo.

According to Pierre Rosenberg, Hans Hahnloser showed the painting to him in Paris in 1969. See Pierre Rosenberg, “A Chardin for Kansas City,” trans. Ursula Korneitchouk, Bulletin (The Nelson Gallery and Atkins Museum) 5, no. 6 (January 1981): 25.

[9] See email from Patricia Tang, E. V. Thaw and Co., to MacKenzie Mallon, NAMA, February 27, 2014, NAMA curatorial files, where she states that Thaw purchased the painting from Hahnloser’s heirs. This is probably a reference to Hans Hahnloser, son and heir of Arthur and Hedy Hahnloser-Bühler.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Jean Siméon Chardin, Still Life with Cat and Fish, 1728,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.310.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Jean Siméon Chardin, Still Life with Cat and Fish, 1728,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.310.4033.

Jean Siméon Chardin, The Ray, ca. 1728, oil on canvas, 32 x 25 1/4 in. (81.2 x 64.1 cm), The Burrell Collection, Glasgow, Scotland, gift from Sir William and Lady Burrell to the City of Glasgow, 1944.

Jean Siméon Chardin, Still–Life with Cat and Fish, 1728, oil on canvas, 31 5/16 x 24 13/16 in. (79.5 x 63 cm), Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, Inv. no. 119 (1986.3).

Jean Siméon Chardin, Still–Life with Cat and Rayfish, 1728, oil on canvas, 31 5/16 x 24 13/16 in. (79.5 x 63 cm), Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, Inv. no. 120 (1986.6).

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Jean Siméon Chardin, Still Life with Cat and Fish, 1728,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.310.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Jean Siméon Chardin, Still Life with Cat and Fish, 1728,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.310.4033.

L’Exposition artistique et archéologique, Poitiers, France, May 14–July 14, 1887, no. 1042, as Chats et Poissons.

Die Hauptwerke der Sammlung Hahnloser, Winterthur, Kunstmuseum, Lucerne, Switzerland, 1940, no. 35, as Le chat et les harengs.

De Watteau à Cezanne, Musée d’art et d’histoire, Geneva, July 7–September 30, 1951, no. 10, as Le Chat et les Harengs.

A Bountiful Decade: Selected Acquisitions, 1977–1987, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, October 14–December 6, 1987, no. 45, as Still Life with Cat and Fish.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Jean Siméon Chardin, Still Life with Cat and Fish, 1728,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.310.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Jean Siméon Chardin, Still Life with Cat and Fish, 1728,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.310.4033.

Possibly Pierre Rémy, Catalogue de Tableaux Originaux des Grands Maîtres Des Écoles d’Italie, des Pays-Bas, et de France, après décès de M. Rémond, ancien Maître-d’Hôtel du Roi Louis XV (Paris: Musier, July 6, 1778), 26, as Deux tableaux sur toile, chacun de 30 pouces de haut, sur 20 de large; dans l’un on voit une raye, des huîtres et un chat; dans l’autre un chat, de la raye et deux merlans.

Possibly Catalogue des Tableaux, Dessins, Marbres, Bronzes et Autres Objets d’Arts, Provenans [sic] du Cabinet de feu M. Armand-Frédéric-Ernest Nogaret, ancien Trésorier du ci-devant Comte d’Artois, etc. ([Paris: Thierry et Langlier, April 6, 1807]), 1, as Divers poissons et un chat or Autre tableau de même genre, faisant pendant du précédent.

Emmanuel Bocher, Les gravures françaises du XVIII siècle, ou, Catalogue raisonné des estampes, eaux-fortes, pièces en couleur, au bistre et au lavis, de 1700 à 1800. Troisième fascicule, Jean-Baptiste Siméon Chardin (Paris: Librairie des Bibliophiles, 1876), 111, as Divers poissons et un chat.

Edmond and Jules de Goncourt, L’art du XVIIIe siècle, series 1, Watteau, Chardin, La Tour, Boucher (Paris: Bibliothèque Charpentier, 1881), 187.

Catalogue de l’exposition artistique et archéologique, exh. cat. (Poitiers, France: Imprimerie Millet, Descoust et Pain, 1887), 73, as Chats et Poissons.

[Albert] Tornézy, “La Peinture Ancienne à l’Exposition Artistique de Poitiers en 1887,” Bulletin de la Société des Antiquaires de l’Ouest, [Poiters] 4 (1889): 363, as Chats et poissons.

“Échos: A [sic] travers Paris,” Le Figaro, no. 166 (June 15, 1897): 1.

“At the Petit Gallery: Exhibition of the Furniture and Pictures of the Late Baron Lepic,” New York Herald, no. 22,213 (June 16, 1897): 2.

Catalogue des Beaux Meubles Louis XV et Louis XVI En laque et en marqueterie, enrichis de cuivres ciselés; Consoles et Glaces; Fauteuils en Tapisserie; Pendules et Appliques; Faiences françaises, Porcelaines, Jades et Objets varies; Tenture Chinoise en Soie peinte; et des Tableaux Anciens par Breughel de Velours, Chardin, Desportes, De Troy, Van der Meulen, J.–B. Oudry, Rigaud, et tout provenant de la Collection de Feu M. le Baron Lepic (Paris: Galerie Georges Petit, June 18, 1897), 9, (repro.), as L’Office.

“Chronique,” La Correspondance historique et archéologique 4 (1897): 183, as L’Office.

“Échos: Vente du baron Lepic,” L’Art pour tous: encyclopédie de l’art industriel et décoratif, no. 138 (June 1897): unpaginated, as L’Office.

“The Lepic Sale: Sensational Prices Made by the Antique Furniture of the Late Baron,” International Herald Tribune, no. 22,216 (June 19, 1897): 2, as L’Office.

“Revue des Ventes,” Gazette de l’Hôtel Drouot, nos. 170–172 (June 19–21, 1897): 1, as L’Office.

“Les On-Dit,” Le Rappel, no. 9963 (June 20, 1897): unpaginated, as L’Office.

“Les On-Dit,” Le XIXe siècle (June 20, 1897): unpaginated.

“Mouvement des arts,” La Chronique des arts et de la curiosité, no. 24 (June 26, 1897): 230, as L’Office.

Hippolyte Mireur, Dictionnaire des Ventes d’Art en France et à l’Étranger pendant les XVIIIe et XIXe Siècles (Paris: Louis Soullié, 1902), 2:150, as L’Office.

Armand Dayot and Jean Guiffrey, J. B. Siméon Chardin, avec une catalogue complet de l’œuvre du mâitre, part 2 (Paris: l’Édition d’Art, H. Piazza, [1907]), 50, as L’Office.

Jean Guiffrey, Catalogue raisonné de l’œuvre peint et dessiné de J.-B. Siméon Chardin (1699–1769), Suivi de la liste des gravures exécutées d’après ses ouvrages (Paris: Imprimerie G. Kadar, 1908), 50, 96, as L’Office and Le Larron en bonne fortune.

Herbert E. A. Furst, Chardin (London: Methuen, 1911), 123, as Le Larron en Bonne Fortune.

Catalogue des Tableaux-Dessins-Pastels, Principalement du XVIIIe siècle des Écoles Anglaise, Française et Italienne, Sculptures du XVIIIe Siècle En Marbre, Terre-cuite, Plâte, Bronze; Objets d’Art et d’Ameublement; Porcelaines et Matières dure montées en bronze, Orfèvrerie, Bois sculptés, Cadres, Gaînes, Poêle en faïence, Objets divers; Bronzes d’Ameublement, Pendules; Appliques, Baromètres, Cadres, Chenets, Candélabres, Flambeaux, etc.; Sieges et Meubles En Bois sculpté, Bois doré et Marqueterie, la plupart signés des Maîtres-Ebénistes du XVIIIe Siècle, Paravent, Ecrans et Sièges en tapisserie et savonnerie, etc. Composant la Collection de M. A. Kann (Paris: Galerie Georges Petit, December 6–8, 1920), 9–11, (repro.), as Les harengs.

“Le Carnet d’un curieux: Vente Alphonse Kann,” La Renaissance de l’art français et des industries de luxe, no. 12 (December 1920): 539, as les Harengs.

“La Collection Alphonse Kann,” Comœdia, no. 2,913 (December 7, 1920): 3, as les Harengs.

“La Curiosité,” Excelsior, no. 3,648 (December 7, 1920): 4.

“La Curiosité,” Journal des débats politiques et littéraires, no. 329 (December 8, 1920), 3, as Les Harengs.

L. Maurice, “Les Ventes,” L’Intransigeant, no. 14,735 (December 8, 1920): 2, as Les Harengs.

H.R., “La Curiosité: La collection Kann,” La Liberté, no. 21,969 (December 8, 1920): 2, as Les Harengs.

La Rivandière, “Notes d’un curieux: Collection Alphonse Kann,” Le Gaulois, no. 45,773 (December 10, 1920): 3, as Les Harengs.

“Recent Paris Art Sales,” American Art News 19, no. 14 (January 15, 1921): 9, as Les harengs.

Georges Wildenstein, Chardin (Paris: Les Beaux-Arts, Édition d’études et de documents, 1933), no. 683 bis, pp. 154, 206–07, as Le Larron en bonne fortune.

Paul Hilber and Hedy Hahnloser-Bühler, Die Hauptwerke der Sammlung Hahnloser, Winterthur, exh. cat. (Basel: Holbein-Verlag, 1940), 8, 16, as Le chat et les harengs.

De Watteau à Cézanne, exh. cat. (Geneva: Musée d’art et d’histoire, 1951), 13, as Le chat et les harengs.

Georges and Daniel Wildenstein, Chardin: Catalogue Raisonné, rev. ed. (Oxford, UK: Bruno Cassirer, 1969), no cat. no., p. 240, as Le larron en bonne fortune.

Marietta Dunn, “Master Paintings Added to Gallery,” Kansas City Star 99, no. 180 (April 15, 1979): [1]E, 8E, (repro.), as Cat with Hake.

Donald Hoffmann, “Gallery Visitors, Revenues Down,”Kansas City Star 99, no. 270 (July 29, 1979): 28A, as Still Life with Cat.

Donald Hoffmann, “Intensity and nuance: the Nelson’s new pastels,” Sunday Star Magazine of the Kansas City Star, supplement, Kansas City Star 100, no. 77 (December 16, 1979): 27.

“Principales acquisitions des musées en 1979,” La Chronique des Arts: supplément à la Gazette des Beaux-Arts 95, no. 1334 (March 1980): 35–36, (repro.), as Nature morte au poisson et au chat.

Pierre Rosenberg, “A Chardin for Kansas City,” trans. Ursula Korneitchouk, Bulletin (The Nelson Gallery and Atkins Museum) 5, no. 6 (January 1981): 20–21, 24–25, 27–33, 34n8, 35, 36n30, (repro.), as Still Life with Cat and Fish.

Donald Hoffmann, “Benefactors’ gifts help keep inflation at bay at the Nelson,” Kansas City Star 101, no. 225 (June 7, 1981): 1F.

Bill Marvel, “How good is the Nelson?” STAR Magazine, supplement, Kansas City Star 103, no. 186 (April 24, 1983): S23, as Still Life with Fish and a Cat.

Donald Hoffmann, “Art journal: This preservation exhibit is better late,” Kansas City Star 103, no. 292 (August 28, 1983): 8E.

Laura Babcock, “The Nelson Art Gallery: A salute to the past,” Kansas City Star 104, no. 19 (October 9, 1983): 2F, as Cat with Hake.

Pierre Rosenberg, L’opera completa di Chardin: presentazione e apparati critici e filologici di Pierre Rosenberg (Milan: Rizzoli, 1983), no. 29A, pp. 66, 75, 123, 128, (repro.), as Gatto con pezzo di salmone due sgombri, tre datteri di mare e frutta.

Pierre Rosenberg, Tout l’œuvre peint de Chardin (Paris: Flammarion, 1983), no. 29A, pp. 66, 75, 123, 128, (repro.), as Chat avec Tranche de Saumon, Deux Maquereaux, Trois Moules et Fruit .

“1986 Annual Report,” Groupe Bruxelles Lamberts s.a. GBL (1986): 14, 62–63, (repro.), as Chat avec tranche de saumon et deux maquereaux.

“Lunch break: Eighteenth-century French painting,” Calendar of Events (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (December 1986): 7, (repro.), as Still Life with Cat and Fish.

Roger Ward, ed., A Bountiful Decade: Selected Acquisitions, 1977–1987, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1987), 110–11, (repro.), as Still Life with Cat and Fish.

René Démoris, Chardin, la chair et l’objet (Paris: Adam Biro, 1991), 50–51, as le Larron en bonne fortune.

Roger Ward and Patricia J. Fidler, eds., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collection (New York: Hudson Hills Press, in association with Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1993), 130, 182, (repro.), as Still Life with Cat and Fish.

Burton B. Frederickson and Benjamin Peronnet, Répertoire des tableaux vendus en France au XIXe siècle (Los Angeles: Provenance Index of the Getty Information Institute, 1998), 1:300, as Divers poissons et un chat.

Pierre Rosenberg and Renaud Temperini, Chardin: suivi du catalogue des œuvres (Paris: Flammarion, 1999), no. 29A, pp. 201, 317, (repro.), as Chat avec tranche de saumon, deux maquereaux, trois moules et fruit.

Pierre Rosenberg, Chardin, trans. Caroline Beamish, exh. cat. (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2000), 131.

Pierre Rosenberg, Chardin, exh. cat. (Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1999), 131.

Deborah Emont Scott, ed., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collection, 7th ed. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2008), XIV, 34, 91, (repro.), as Still Life with Cat and Fish.

Pierre Rosenberg, Chardin: Il pittore del silenzio, exh. cat. (Ferrara: Fondazione Cassa de Risparmio di Ferrara, 2010), 82, (repro.), as Gatto con trancio di salmone, due sgombri, tre cozze e frutta.