Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Mia Laufer, “Camille Pissarro, Wooded Landscape at L’Hermitage, Pontoise, 1879,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.644.5407.

MLA:

Laufer, Mia. “Camille Pissarro, Wooded Landscape at L’Hermitage, Pontoise, 1879,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.644.5407.

Camille Pissarro’s Wooded Landscape at L’Hermitage, Pontoise presents us with a tangled web of trees. At times, this mess of foliage verges on abstraction; it almost completely obscures a small figure in the right foreground, who appears to be trudging through the dense brush. Beyond the trees lies the Hermitage, the oldest section of the village of Pontoise, its white houses with red and blue roofs peeking out between the branches. Pissarro often used this “screen of trees” motif during the late 1870s, placing nature as a separation between the figure (and by extension, the viewer) and the markers of civilization beyond.1Christophe Duvivier, “‘L’humble et colossal Pissarro’/‘The humble and colossal Pissarro,’” in Camille Pissarro: Le Premier des Impressionnistes/The First Among the Impressionists, exh. cat. (Paris: Musée Marmottan Monet, 2017), 57. As Richard Brettell has observed, during this moment in his career, Pissarro gave less prominence to architecture and instead “observed civilization from nature.” Richard R. Brettell, Pissarro and Pontoise: A Painter in a Landscape (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990), 192. Trees become a pictorial framework, a veil through which we encounter the rural village society. Pissarro probably developed this visual device from his early mentor Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796–1875). Yet unlike the hazy atmosphere of Corot’s idyllic scenes, such as The Lake (Fig. 1), Pissarro’s picture has a rough-hewn quality. Pissarro created Wooded Landscape with a thick impastoimpasto: A thick application of paint, often creating texture such as peaks and ridges.. He seems to have reveled in the materiality of his medium, using a similar hatch-marked application of paint across the various elements in the composition—sky, houses, trees, grass, and figure. Later in 1879, Pissarro revisited this composition in a series of prints, exploring how the graphic medium could be manipulated to highlight different facets of the painting, including its complex brushwork, its ambiguous sense of depth, and the visibility of the figure.

Despite the camaraderie and support of his fellow artists, Pissarro was going through a particularly difficult period as he painted Wooded Landscape. In the late 1870s, the artist had mounting family obligations, debts to be paid, and few clients to buy his art. He spent much of his time traveling back and forth to Paris in order to meet with dealers and collectors in the hope of finding a market for his work. Overcome with depression, he wrote to his friend and champion Eugène Murer: “Art is a matter of a hungry belly, an empty purse, of a poor wretch.”6“La question d’art . . . c’est une affaire de ventre affamé, de bourse vide, de pauvre hère.” Camille Pissarro to Eugène Murer, 1878, in Janine Bailly-Herzberg, ed., Correspondance de Camille Pissarro (Paris: Presses Universaires de France, 1980), 1:116. At times of extreme financial distress, such as those he faced in the late 1870s, Pissarro turned to a handful of patrons who were early and adamant champions of Impressionist art, including fellow artist Gustave Caillebotte (1848–1894) and collectors Eugène Murer and Georges de Bellio (1828–1894). De Bellio was the first owner of Pissarro’s Wooded Landscape.7De Bellio was born in Bucharest to a wealthy family and maintained a modest life in Paris funded by the income from his estate and allowances sent from his family. He began collecting art in 1864 and assembled an eclectic collection with work by Sandro Botticelli (Florentine, 1444/1445–1510), Frans Hals (Dutch, about 1581–1666), Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732–1806), Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863), and the Barbizon painters. He was also an early supporter of the Impressionists, particularly Claude Monet (1840–1926), although he owned around ten works by Pissarro as well. De Bellio practiced homeopathic medicine and treated many of the Impressionists and their families, including the Pissarros. Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919) later recalled that, “every time one of us was in urgent need of a couple of hundred francs, [that person] would run to the Café Riche at lunchtime with a picture. One was sure to find Monsieur de Bellio there, and he would buy it without even looking at it.” Ambroise Vollard, Renoir: An Intimate Record (New York: Dover Publications, 1990), 31. For a detailed study of Georges de Bellio, see Remus Niculescu, “Georges de Bellio, l’ami des impressionnistes,” Revue roumaine d’histoire de l’art 1, no. 2 (1964): 209–78. For English-language discussions of the collector, see Anne Distel, Impressionism: The First Collectors, trans. Barbara Perroud-Benson (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1989), 109–23, and Marianne Mathieu, “A Painting and a Family: Impression, Sunrise in the De Bellio and Donop de Monchy Collections (1878–1937),” in Monet’s ‘Impression Sunrise:’ The Biography of a Painting (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), 134–63.

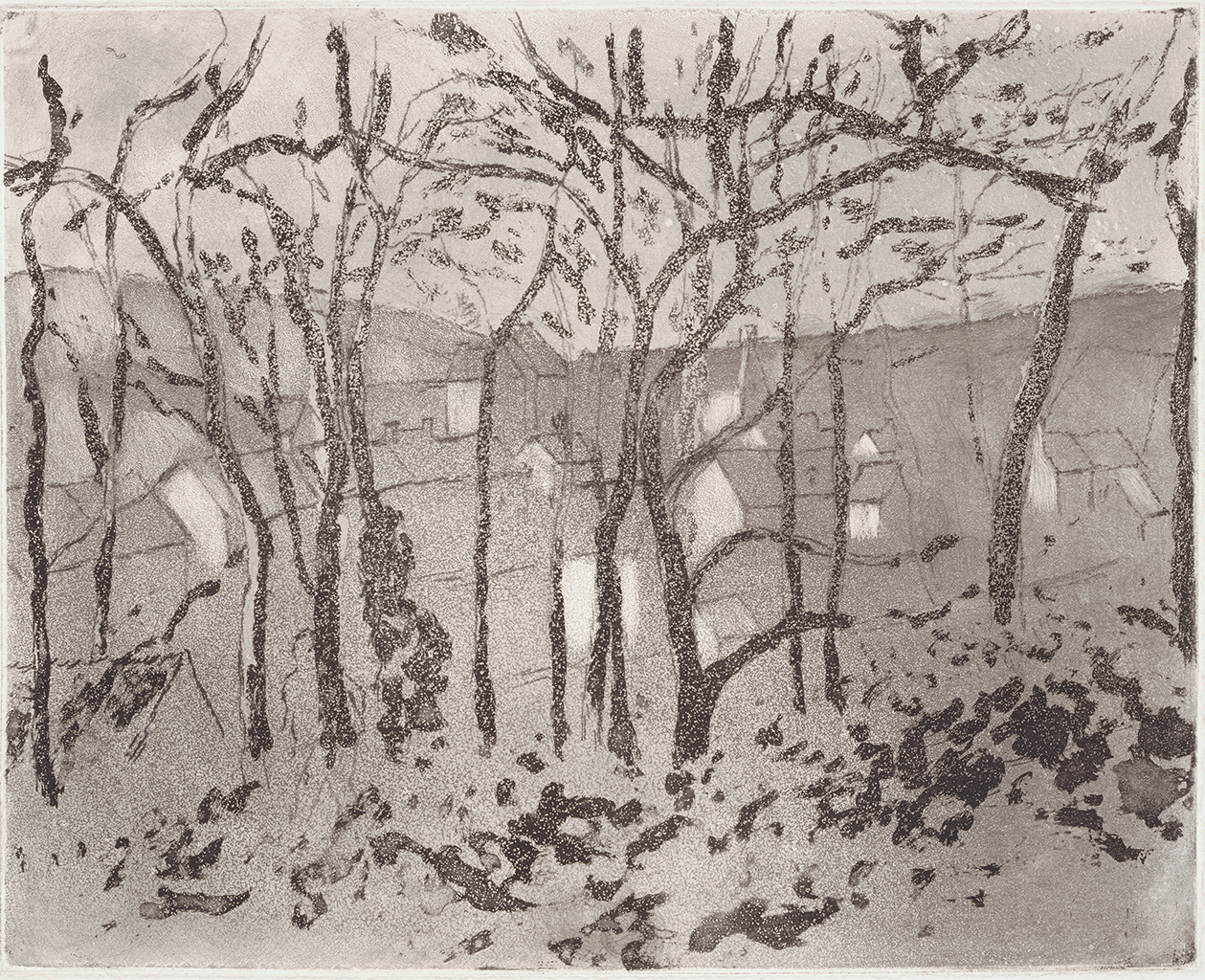

Fig. 3. Camille Pissarro, Wooded Landscape at the Hermitage, 1879, aquatint and soft-ground etching with scraping and polishing, second state, image: 8 1/2 x 10 5/8 in. (21.6 x 27 cm), Minneapolis Institute of Art, Gift of Philip W. Pillsbury, 1959, P.12,795

Fig. 3. Camille Pissarro, Wooded Landscape at the Hermitage, 1879, aquatint and soft-ground etching with scraping and polishing, second state, image: 8 1/2 x 10 5/8 in. (21.6 x 27 cm), Minneapolis Institute of Art, Gift of Philip W. Pillsbury, 1959, P.12,795

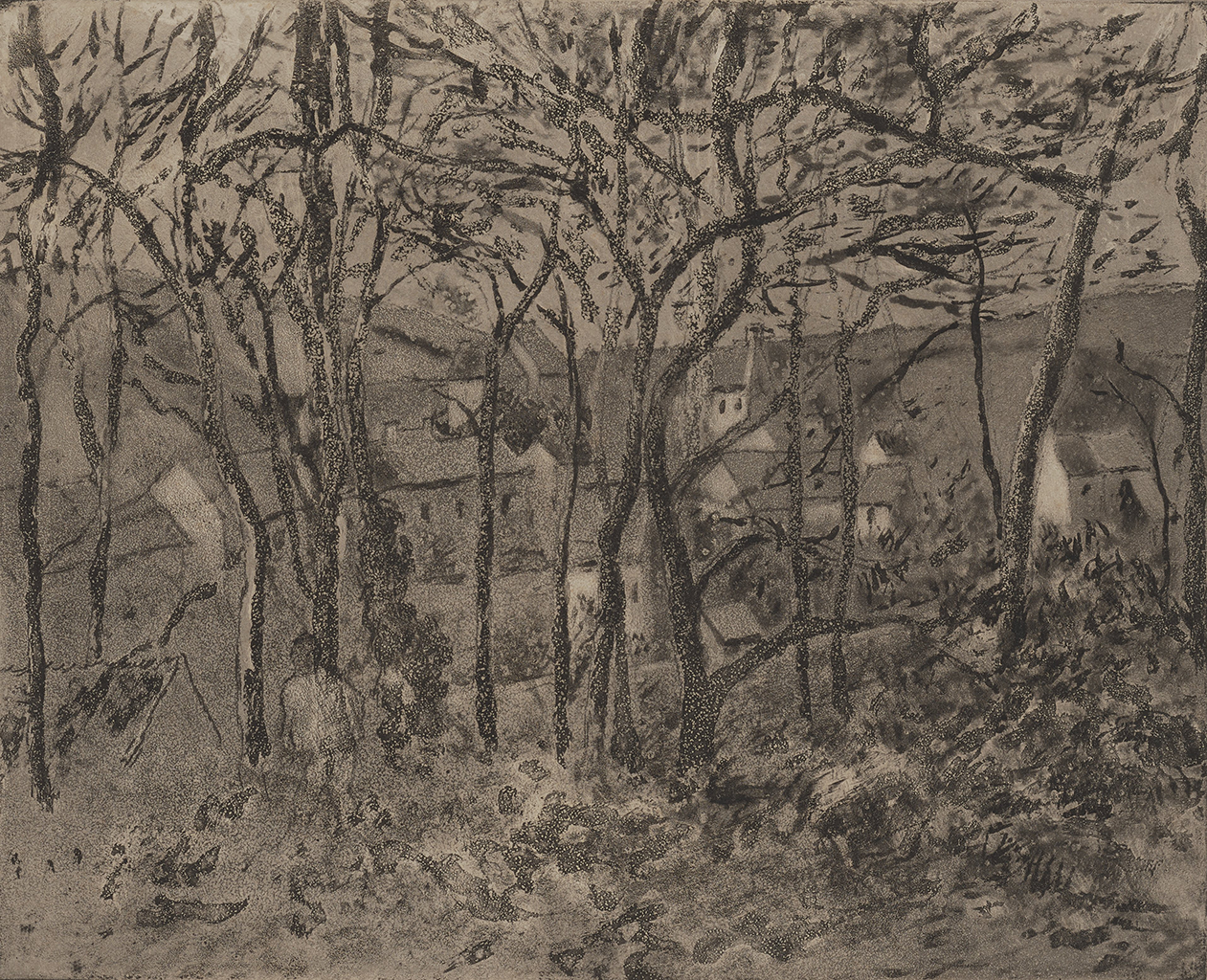

Fig. 4. Camille Pissarro, Wooded Landscape at the Hermitage, Pontoise, 1879, soft-ground etching, aquatint, and drypoint, sixth state, image: 8 1/2 x 10 1/2 in. (21.8 x 26.7 cm); sheet: 14 x 19 in. (35.6 x 48.3 cm), Nelson Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, Purchase: Nelson Gallery Foundation, F83-60

Fig. 4. Camille Pissarro, Wooded Landscape at the Hermitage, Pontoise, 1879, soft-ground etching, aquatint, and drypoint, sixth state, image: 8 1/2 x 10 1/2 in. (21.8 x 26.7 cm); sheet: 14 x 19 in. (35.6 x 48.3 cm), Nelson Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, Purchase: Nelson Gallery Foundation, F83-60

Pissarro often reworked his plates, printing different states of the same composition with considerable differences in tone and feel. Pissarro used a mix of printing tools—needles, pens, aquatint grounds, acids, gums—what Cathy Leahy has called “a smorgasbord of intaglio processes.”18Stephen F. Eisenman, From Corot to Monet: The Ecology of Impressionism, exh. cat. (Milan: Skira, 2010), 302; Leahy, “Impressionist Printmaking,” 179. In each printed version of Wooded Landscape, Pissarro explored how to translate the original painting’s impasto texture, knitted brushwork, and dynamic, layered composition into the print medium.

The paint and print versions of this composition allow viewers a glimpse of village life beyond the trees, positioning us alongside the figure trudging through the forest. While the painting depicts a clear spring day, formal variations in the prints present us with the same scene in a variety of times of the day and year. In his first-state print (Fig. 2), Pissarro detangles foreground and background; the figure is evoked by a few small gestures and all but disappears. The composition is pared down to its most basic elements, and the foliage in the foreground becomes almost fully abstract. The trees are dark and bare, and the midtone used across the lower two-thirds of the composition reads as snow that blankets the landscape. Pissarro’s second-state print (Fig. 3), on the other hand, is a study in midtones, giving the print a hazy quality that bears closer resemblance to Corot’s work (see Fig. 1) than Pissarro’s Wooded Landscape painting. Pissarro’s complex mark-making in the foliage at the top and bottom of the composition echo the intricate brushwork of the painting, but without the original’s bright blue sky, the print seems to capture the same scene at dawn or dusk. Pissarro’s sixth-state print (Fig. 4) is full of contrasts, with dark and light moments placed side by side, evoking bright sunlight and making the figure far more visible than in the original painting. With stark contrasts in place of the painting’s lush green coloring, this print seems to depict a crisp day in early autumn.

Pissarro included four stages of his Wooded Landscape print in the fifth Impressionist exhibition in 1880, all displayed together in a single purple frame.19Leahy, “Impressionist Printmaking,” 179. Showing several of these prints together demonstrated his flexibility, innovation, and skill at printmaking. As several authors have noted, it can also be seen as a precursor to Claude Monet’s series paintings. As in Monet’s haystacks and cathedrals, the prints show the same scene in different moods, seasons, or weather.20See, for example, Leahy, “Impressionist Printmaking,” 179; and Shikes and Harper, Pissarro: His Life and Work, 169. Seen in this light, Pissarro’s Wooded Landscape painting and prints serve as an exceptional case study in the exploration and development of Impressionist aesthetic innovation.

Notes

-

Christophe Duvivier, “‘L’humble et colossal Pissarro’/‘The humble and colossal Pissarro,’” in Camille Pissarro: Le Premier des Impressionnistes/The First Among the Impressionists, exh. cat. (Paris: Musée Marmottan Monet, 2017), 57. As Richard Brettell has observed, during this moment in his career, Pissarro gave less prominence to architecture and instead “observed civilization from nature.” Richard R. Brettell, Pissarro and Pontoise: A Painter in a Landscape (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990), 192.

-

Richard R. Brettell, “Pissarro, Cézanne, and the School of Pontoise,” in Andrea P.A. Belloli, ed., A Day in the Country: Impressionism and the French Landscape, exh. cat. (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1984), 182.

-

Ralph E. Shikes and Paula Harper, Pissarro: His Life and Work (New York: Horizon Press, 1980), 153–54.

-

Brettell, “Pissarro, Cézanne, and the School of Pontoise,” 178.

-

Brettell, “Pissarro, Cézanne, and the School of Pontoise,” 178.

-

“La question d’art . . . c’est une affaire de ventre affamé, de bourse vide, de pauvre hère.” Camille Pissarro to Eugène Murer, 1878, in Janine Bailly-Herzberg, ed., Correspondance de Camille Pissarro (Paris: Presses Universaires de France, 1980), 1:116.

-

De Bellio was born in Bucharest to a wealthy family and maintained a modest life in Paris funded by the income from his estate and allowances sent from his family. He began collecting art in 1864 and assembled an eclectic collection with work by Sandro Botticelli (Florentine, 1444/1445–1510), Frans Hals (Dutch, about 1581–1666), Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732–1806), Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863), and the Barbizon paintersBarbizon School: A group of French artists, who united around 1830 to form the Barbizon School, which was named after a small village thirty miles northwest of Paris, where they lived and painted. Rebelling against the French Academy’s refined, idealized landscapes, these artists infused the immediacy of the sketches they created outdoors into their finished studio paintings.. He was also an early supporter of the Impressionists, particularly Claude Monet (1840–1926), although he owned around ten works by Pissarro as well. De Bellio practiced homeopathic medicine and treated many of the Impressionists and their families, including the Pissarros. Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919) later recalled that, “every time one of us was in urgent need of a couple of hundred francs, [that person] would run to the Café Riche at lunchtime with a picture. One was sure to find Monsieur de Bellio there, and he would buy it without even looking at it.” Ambroise Vollard, Renoir: An Intimate Record (New York: Dover Publications, 1990), 31. For a detailed study of Georges de Bellio, see Remus Niculescu, “Georges de Bellio, l’ami des impressionnistes,” Revue roumaine d’histoire de l’art 1, no. 2 (1964): 209–78. For English-language discussions of the collector, see Anne Distel, Impressionism: The First Collectors, trans. Barbara Perroud-Benson (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1989), 109–23, and Marianne Mathieu, “A Painting and a Family: Impression, Sunrise in the De Bellio and Donop de Monchy Collections (1878–1937),” in Monet’s ‘Impression Sunrise:’ The Biography of a Painting (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), 134–63.

-

The composition was reversed in the etching process. Barbara S. Shapiro, “Four Intaglio Prints by Camille Pissarro,” Boston Museum Bulletin 69, no. 357 (1971): 135.

-

Cathy Leahy, “Impressionist Printmaking: Le Jour et La Nuit,” in French Impressionism from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, exh. cat. (Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 2021), 172.

-

George T. M. Shackelford and Fronia E. Wissman, Impressions of Light: The French Landscape from Corot to Monet, exh. cat. (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 2002), 164.

-

Leahy, “Impressionist Printmaking,” 171.

-

Sarah Lees, Innovative Impressions: Prints by Cassatt, Degas, and Pissarro, exh. cat. (Tulsa, OK: Philbrook Museum of Art, 2018), 26.

-

A few examples of this trend include Pissarro’s early training with Fritz Melbye (Danish, 1826–1896) in the Caribbean in the 1850s, his experience with the School of Pontoise in the 1860s and 1870s, and his exploration of Neo-Impressionism in the late 1880s and 1890s.

-

Leahy, “Impressionist Printmaking,” 172.

-

Leahy, “Impressionist Printmaking,” 172.

-

Distel, Impressionism, 226, 253. Shapiro, “Four Intaglio Prints by Camille Pissarro,” 133.

-

Degas made serious efforts to promote Le Jour et la Nuit, even writing to friends in England for support. Shapiro, “Four Intaglio Prints by Camille Pissarro,” 133.

-

Stephen F. Eisenman, From Corot to Monet: The Ecology of Impressionism, exh. cat. (Milan: Skira, 2010), 302; Leahy, “Impressionist Printmaking,” 179.

-

Leahy, “Impressionist Printmaking,” 179.

-

See, for example, Leahy, “Impressionist Printmaking,” 179; and Shikes and Harper, Pissarro: His Life and Work, 169.

Technical Entry

Technical entry forthcoming.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Camille Pissarro, Wooded Landscape at L’Hermitage, Pontoise, 1879,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023),http:https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.644.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Camille Pissarro, Wooded Landscape at L’Hermitage, Pontoise, 1879,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.644.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Camille Pissarro, Wooded Landscape at L’Hermitage, Pontoise, 1879,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), http:https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.644.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Camille Pissarro, Wooded Landscape at L’Hermitage, Pontoise, 1879,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.644.4033.

Probably purchased from the artist by Dr. Georges de Bellio (né Gheorge Bellu, 1828–1894), Paris, by January 26, 1894 [1];

By descent to his daughter, Victorine (née Victorina Bellu, later de Bellio, 1863–1958), and son-in-law, Eugène “Ernest” (1860–1942) Donop de Monchy, Paris, by January 26, 1894;

Possibly purchased by Ambroise Vollard, Paris, no. 3049, no later than 1899 [2];

Emil (1867–1929) and Alma (née Terlinden, 1883–1970) Staub-Terlinden, Villa Alma, Männedorf, Switzerland, as Village ou à travers les arbres, by October 5, 1917–February 15, 1929 [3];

Inherited by Alma Staub-Terlinden, Männedorf, Switzerland, 1929–1942 [4];

Purchased from Staub-Terlinden by Wildenstein and Company, New York, 1942–probably before October 24, 1945 [5];

Purchased from Wildenstein by Andre Kostelanetz (1901–1980) and Alice Joséphine “Lily” Pons (1898–1976), New York, probably by October 24, 1945–1958 [6];

Andre Kostelanetz and Sarah Gene (née Orcutt, b. 1928) Kostelanetz, New York, 1958–1969 [7];

Andre Kostelanetz, New York, 1969–at least July 8, 1976 [8];

Purchased from Kostelanetz, through John and Paul Herring and Company, New York, by Dr. Nicholas S. (1910–1993) and Mrs. Eva Ann (née McClusky, 1914–2008) Pickard, Shawnee Mission, KS, after July 8, 1976 –December 5, 1984 [9];

Given by Dr. and Mrs. Nicholas S. Pickard to The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1984.

Notes

[1] See circular stamp with faded ink on the painting’s verso that closely resembles the collector’s stamp for Eugène and Victorine Donop de Monchy. The number “106” is handwritten in the center of the stamp. This number corresponds to the painting Le Printemps; maisons vues à travers les branches in the unpublished inventory that was drawn up after de Bellio’s death by his son-in-law, Eugène Donop de Monchy. See “Catalogue des tableaux anciens et modernes, aquarelles, dessins, pastels, miniatures, formant la collection de Mr. E. Donop de Monchy (Ancienne collection Georges de Bellio),” ca. 1894–1897, Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris, Archives. Special thanks to Claire Gooden, Attachée de conservation, Musée Marmottan Monet.

The 1904 exhibition catalogue (Exposition de l’Œuvre de Camille Pissarro, Galeries Durand-Ruel) in which the painting appears as no. 49, specifies “à M. Donop de Monchy”, but the Vollard label on the verso of the painting indicates that the dealer must have owned the painting as late as 1899 (see provenance note 2).

[2] A label preserved on the verso is similar in style to Vollard labels, and it says “3049.” Two other paintings in the collection of the Nelson-Atkins also have Vollard labels: Gauguin F77-32 was stock number “395[8]” and was owned by Vollard by September 1899; Cezanne 2015.13.6 was stock book A, no. 3526 and was owned by Vollard by December 1899. Since the Pissarro stock number 3049 is before 3958 and 3526, it was probably purchased by Vollard no later than 1899.

However, Cezanne scholar Jayne Warman, does not know of any Vollard stockbooks nor any reference in Vollard’s archives to numbers before 3301. See email from Warman to Danielle Hampton Cullen, NAMA, August 2, 2021, NAMA curatorial files.

[3] The Staub-Terlindens began collecting art shortly after their marriage in 1903, but purchased a majority of their collection in 1916–1917 (some of which came from Vollard). They owned the Pissarro at least by 1917, when they lent it to an exhibition in Zurich. The painting is also listed and reproduced in an inventory of the Staub-Terlinden collection; see Carl Montag, “Reproduktionen aus der Sammlung Staub-Terlinden, Männedorf,” ca. 1918, Schweizerisches Institut für Kunstwissenschaft (SIK-ISEA), Zurich, Switzerland.

[4] This painting was probably among several works Alma Staub-Terlinden consigned to Wildenstein sometime after the 1938 exhibition, La Peinture Français de XIXe Siècle en Suisse. According to the catalogue raisonné, Wildenstein purchased the painting in 1942; see Joachim Pissarro and Claire Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Catalogue critique des peintures; Critical Catalogue of Paintings (New York: Wildenstein Institute Publications, 2005), no. 614.

[5] The painting was exhibited at Camille Pissarro: His Place in Art, Wildenstein and Co., New York, October 24–November 24, 1945, but it was lent anonymously. According to the catalogue raisonné, Wildenstein sold the painting to Mr. and Mrs. Kostelanetz in 1945; see Joachim Pissarro and Claire Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Catalogue critique des peintures; Critical Catalogue of Paintings (New York: Wildenstein Institute Publications, 2005), no. 614. Kostelanetz may have been the anonymous lender, purchasing the painting from Wildenstein and Co., New York before the exhibition.

[6] An art collector herself, Lily Pons hung the painting in her music library in her Gracie Square apartment (which she first rented in October 1945); see Rosamund Frost, “Lily Pons, Diva in Art,” Art News 45, no. 6 (August 1946): 37.

[7] Andre Kostelanetz and Lily Pons divorced in 1958. Andre remarried Sara Gene Orcutt in 1960. The painting was lent to the 1965 exhibition C. Pissarro: Loan Exhibition For the benefit of Recording for the Blind, Inc. by “Mr. and Mrs. Andre Kostelanetz.” Andre and Sarah Gene divorced in 1969.

[8] Andre retained the work after his second divorce, and the painting was appraised for him by Harold Diamond, New York, on February 3, 1973; see correspondence from Harold Diamond, New York, to Andre Kostelanetz, February 3, 1973, The Library of Congress, Washington, DC, Andre Kostelanetz Collection, Box 1132, Folder 9 “D” miscellaneous, 1939–1976, February 3, 1973. It does not appear that he married again after 1969. Special thanks to Robert Lipartito, Music Reference Specialist, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

[9] See letter from John D. Herring, John and Paul Herring and Company, New York, to Dr. Nicholas Pickard, July 8, 1976, NAMA curatorial files.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Camille Pissarro, Wooded Landscape at L’Hermitage, Pontoise, 1879,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), http:https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.644.4033

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Camille Pissarro, Wooded Landscape at L’Hermitage, Pontoise, 1879,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.644.4033.

Camille Pissarro, Wooded Landscape at l’Hermitage, pencil, ca. 1878, 8 1/2 x 10 3/4 in. (21.5 x 27 cm), location unknown, cited in Barbizon Impressionist and Modern Drawings, Paintings and Sculpture (New York: Christie, Manson and Woods, July 5, 1968), 17.

Camille Pissarro, Wooded Landscape at the Hermitage, Pontoise, 1879, softground etching and aquatint on cream wove paper, first state, 8 1/2 x 10 1/2 in. (21.6 x 26.7 cm), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1971.267.

Camille Pissarro, Wooded Landscape at the Hermitage, 1879, aquatint and soft-ground etching with scraping and polishing, second state, 8 1/2 x 10 5/8 in. (21.6 x 27 cm), Minneapolis Institute of Art, P.12,795.

Camille Pissarro, Wooded Landscape at the Hermitage, near Pontoise, 1879, soft-ground etching, lift-ground and spit-bite aquatint, and drypoint with scraping and burnishing, third state, plate: 8 1/2 × 10 1/2 in. (21.7 × 26.6 cm); sheet: 11 7/8 x 16 7/8 in. (30.2 x 43 cm), Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1941-8-105.

Camille Pissarro, Wooded Landscape at the Hermitage, Pontoise, 1879, soft ground etching and aquatint on beige laid paper, fourth state, 8 1/2 x 10 1/2 in. (21.6 x 26.6 cm), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1971.268.

Camille Pissarro, In the Woods at the Hermitage at Pontoise, 1879, aquatint, fifth state, 8 1/2 x 10 3/4 in. (21.5 x 27 cm), Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Cambridge, MA, M2157.

Camille Pissarro, Wooded Landscape at L’Hermitage, Pontoise, 1879, soft-ground etching, aquatint, and drypoint, sixth state, image: 8 1/2 x 10 1/2 in. (21.8 x 26.7 cm); sheet: 14 x 19 in. (35.6 x 48.3 cm), The Nelson Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, F83-60.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Camille Pissarro, Wooded Landscape at L’Hermitage, Pontoise, 1879,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), http:https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.644.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Camille Pissarro, Wooded Landscape at L’Hermitage, Pontoise, 1879,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.644.4033.

Exposition de l’Œuvre de Camille Pissarro, Galeries Durand-Ruel, Paris, April 7–30, 1904, no. 49, as Le Val Hermet, près Pontoise.

Französische Kunst des XIX. u. XX. Jahrhunderts, Kunsthaus, Zurich, October 5–November 14, 1917, no. 156, as Village.

La Peinture Français de XIXe Siècle en Suisse, Galerie de la Gazette des Beaux-Arts, Paris, May–June, 1938, no. 75, as Village vu a [sic] travers les arbres.

Camille Pissarro: His Place in Art, Wildenstein, New York, October 24–November 24, 1945, no. 15, as Paysage sous Bois à l’Hermitage.

C. Pissarro: Loan Exhibition For the benefit of Recording for the Blind, Wildenstein, New York, March 25–May 1, 1965, no. 38, as Paysage sous Bois à l’Hermitage, Pontoise.

Camille Pissarro: The Impressionist Printmaker, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, June 14–October 14, 1973, no. 8, as Paysage sous bois à l’Hermitage (Pontoise).

The Crisis of Impressionism, 1878–1882, The University of Michigan Museum of Art, Ann Arbor, November 2, 1979–January 6, 1980, no. 37, as Paysage sous bois à l’Hermitage, Pontoise.

Retrospective Camille Pissarro, Isetan Museum of Art, Tokyo, March 9–April 9, 1984; Fukuoka Art Museum, April 25–May 20, 1984; Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art, May 26–July 1, 1984, no. 30, as Paysage sous bois à l’Hermitage.

A Bountiful Decade: Selected Acquisitions, 1977–1987, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, October 14–December 6, 1987, no. 64, as Wooded Landscape (Paysage sous Bois à l’Hermitage).

Impressionism: Selections From Five American Museums, Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, November 4–December 31, 1989; Minneapolis Institute of Arts, January 27–March 25, 1990; The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, April 21–June 17, 1990; Saint Louis Art Museum, July 14–September 9, 1990; Toledo Museum of Art, OH, September 30–November 25, 1990, no. 63, as Wooded Landscape at l’Hermitage, Pontoise.

Inked in Time: Six Centuries of Printed Masterpieces, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, February 22–May 31, 1998, no cat.

Innovative Impressions: Cassatt, Degas, and Pissarro as Painter-Printmakers, Philbrook Museum of Art, Tulsa, OK, June 3–September 2, 2018, no. 65, as Wooded Landscape at the Hermitage, Pontoise.

Among Friends: Guillaumin, Cezanne, and Pissarro, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, January 28, 2021–January 23, 2022, no cat.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Camille Pissarro, Wooded Landscape at L’Hermitage, Pontoise, 1879,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), http:https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.644.4033

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Camille Pissarro, Wooded Landscape at L’Hermitage, Pontoise, 1879,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.644.4033.

Catalogue de l’Exposition de l’Œuvre de Camille Pissarro, exh. cat. (Paris: Galeries Durand-Ruel, 1904), 15, as Le Val Hermet, près Pontoise.

Jean Denauroy, “Dans Les Exposition: Exposition Camille Pissarro,” Les Temps, no. 51 (April 16–22, 1904): 7.

Französische Kunst des XIX. u. XX. Jahrhunderts, exh. cat. (Zurich: Kunsthaus, 1917), 23, as Village.

René-Jean, “L’Art Français dans une collection Suisse: La Collection de M. Staub-Terlinden,” La Renaissance 6, no. 8 (August 1923): 472.

Pierre Courthion, “L’Art français dans les collections privées en Suisse,” L’Amour de l’Art 7 (February 1926): 42, as Village vu à travers les arbres.

Waldemar George, “The Staub Collection at Männedorf,” Formes, no. 25 (May 25, 1932): 272.

La Peinture Français de XIXe Siècle en Suisse, exh. cat. (Paris: Gazette des Beaux-Arts, 1938), 40, as Village vu a [sic] travers les arbres.

“La Peinture Française en Suisse,” Gazette des Beaux-Arts 19 (April 1938): unpaginated.

Ludovic Rodo Pissarro and Lionello Venturi, Camille Pissarro, Son art, Son Œuvre (Paris: Paul Rosenberg, 1939), no. 444, pp. 1:143; 2:unpaginated, (repro.), as Paysage Sous Bois a L’Hermitage.

Camille Pissarro: His Place in Art, exh. cat. (New York: Wildenstein, 1945), 34, as Paysage sous Bois à l’Hermitage.

Edward Alden Jewell, “Works of Pissarro on Display Tonight: Art of French Impressionist to Be Seen at Wildenstein’s–Show to Last a Month,” New York Times 95, no. 32,050 (October 24, 1945): 19.

Rosamund Frost, “Lily Pons, Diva in Art,” Art News 45, no. 6 (August 1946): 37, (repro.), as Village à travers les arbres.

Remus Niculescu, “Georges de Bellio, l’ami des impressionnistes,” Revue roumaine d’histoire de l’art, no. 2 (1964): 241, 265 [repr., in Remus Niculescu, Georges de Bellio: l’ami des impressionnistes (Paris: Editions de l’Académie de la république populaire roumaine, 1970), 32, 72, 84], as Le Printemps, Maisons Vues à travers les arbres and Paysage Sous-Bois à L’Hermitage.

C. Pissarro: Loan Exhibition For the benefit of Recording for the Blind, Inc., exh. cat. (New York: Wildenstein, 1965), unpaginated, as Paysage sous Bois à l’Hermitage, Pontoise.

Barbizon Impressionist and Modern Drawings, Paintings and Sculpture (New York: Christie, Manson and Woods, July 5, 1968), 17.

Barbara S. Shapiro, “Four Intaglio Prints by Camille Pissarro,” Boston Museum Bulletin 69, no. 357 (1971): 135, (repro.), as Paysage sous Bois à l’Hermitage, Pontoise.

Stephen E. Rubin, “Andre Kostelanetz–Middlebrow Toscanini?,” New York Times 122, no. 42,106 (May 6, 1973): 191.

Barbara S. Shapiro, Camille Pissarro: The Impressionist Printmaker, exh. cat. (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1973), unpaginated, as Paysage sous bois, à l’Hermitage (Pontoise).

Janine Bailly-Herzberg, ed., Correspondance de Camille Pissarro (Paris: Editions du Valhermeil, 1980), 1:161n1, as Le Printemps, maisons vues à travers les arbres.

Joel Isaacson, The Crisis of Impressionism, 1878–1882, exh. cat. (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Museum of Art, 1980), 150–51, 153, as Paysage sous bois à l’Hermitage, Pontoise.

John Rewald et al., Pissarro: Camille Pissarro, 1830–1903, exh. cat. (London: Arts Council of Great Britain, 1980), 110, 112, 115, 202, as Wooded landscape at L’Hermitage.

Ralph E. Shikes and Paula Harper, Pissarro: His Life and Work (New York: Horizon Press, 1980), 170–71.

Christopher Lloyd, Camille Pissarro (Geneva: Skira, 1981), 79, as L’Hermitage.

Richard R. Brettell et al., Retrospective Camille Pissarro, exh. cat. (Tokyo: Isetan Museum of Art, 1984), 54, 132–33, (repro.), as Paysage sous bois à l’Hermitage.

“Pissarro Painting Added to Museum Impressionist Collection,” Calendar of Events (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (May 1985): unpaginated, (repro.) as Paysage sous bois à l’Hermitage, Pontoise.

Donald Hoffmann, “Pissarro gift is impressionist treasure,” Kansas City Star 105, no. 176 (April 14, 1985): 8D, (repro.), as A Landscape Through the Woods at the Hermitage, Pontoise and Paysage sous bois a [sic] l’Hermitage.

Donald Hoffmann, “Important growth at the Nelson Gallery,” Kansas City Star 105, no. 214 (May 29, 1985): 8A, as A Landscape Through the Woods at the Hermitage, Pontoise.

Roger Ward, ed., A Bountiful Decade: Selected Acquisitions, 1977–1987, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1987), 148–49, 236, (repro.), as Wooded Landscape (Paysage sous bois à l’Hermitage).

Colta Ives, “French Prints in the Era of Impressionism and Symbolism,” Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin (Summer 1988): 22, (repro.), as Wooded Landscape at L’Hermitage, Pontoise.

Anne Distel, Impressionism: The First Collectors, trans. Barbara Perroud-Benson (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1989), 121, as l’Hermitage.

Marc S. Gerstein, Impressionism: Selections from Five American Museums, exh. cat. (New York: Hudson Hills, 1989), 12, 148, (repro.), as Wooded Landscape at L’Hermitage, Pontoise.

Toni Wood, “The impressionists broke all the rules: Modern viewers love impressionism,” Kansas City Star 110, no. 184 (April 15, 1990): H-4, as Wooded Landscape at l’Hermitage, Pontoise.

Scott Cantrell, “Keepers of the Light: Working from individual blueprints, impressionists laid colorful bricks in the foundation of modern art,” Kansas City Star 110, no. 191 (April 22, 1990): I-4, as Wooded Landscape at l’Hermitage, Pontoise.

Toni Wood, “Expatriate paintings in Midwest: Works took diverse routes to exhibit,” Kansas City Star 110, no. 233 (June 3, 1990): G1, G5, as Wooded Landscape at l’Hermitage, Pontoise.

Ludovico Rodo Pissarro and Lionello Venturi, Camille Pissarro, Son Art—Son Œuvre, 2nd rev. ed. (San Francisco: Alan Wofsy Fine Arts, 1989), no. 444, pp.1:143; 2:unpaginated, (repro.), as Paysage sous bois a [sic] L’Hermitage.

Richard R. Brettell, Pissarro and Pontoise: The Painter in a Landscape (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990), 59, 192, 209n33, as Paysage sous bois a [sic] l’Hermitage.

Bernard Denvir, The Thames and Hudson Encyclopaedia of Impressionism (London: Thames and Hudson, 1990), 179, as Wooded Landscape at l’Hermitage, Pontoise.

Roger Ward, “Selected Acquisitions of European and American Paintings at The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, 1986–1990,” Burlington Magazine 133, no. 1055 (February 1991): 158.

Joel Isaacson, “Pissarro’s doubt: Plein-air painting and the abiding questions,” Apollo 130, no. 369 (November 1992): 322–24, (repro.), as Wooded Landscape at the Hermitage, Pontoise.

Bernard Denvir, The Chronicle of Impressionism: An Intimate Diary of the Lives and World of the Great Artists (London: Thames and Hudson, 1993), 279.

Roger Ward and Patricia J. Fidler, eds., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collection (New York: Hudson Hills Press, in association with Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1993), 207, (repro.), as Wooded Landscape at L’Hermitage, Pontoise.

Joel Isaacson, “Constable, Duranty, Mallarmé, Impressionism, Plein Air, and Forgetting,” Art Bulletin 76, no. 3 (September 1994): 437n50, 442–43, (repro.), as Wooded Landscape at L’Hermitage, Pontoise.

Jean Leymaire et al., Camille Pissarro, exh. cat. (Ferrara, Italy: Palazzo dei Diamanti, 1998), 131.

Christoph Becker, Camille Pissarro, exh. cat. (Stuttgart, Germany: Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, 1999), 152, 155, (repro.), as Waldlandschaft bei L’Hermitage, Pontoise.

Loys Delteil et al., Camille Pissarro: l’ɶuvre gravé et lithographié (San Francisco, CA: Alan Wofsy Fine Arts, 1999), 27.

Christoph Becker and et al, Camille Pissarro (Ostfildern-Ruit: Hatje Cantz Publishers, 1999), 151–52, (repro.), as Wooded Landscape at L’Hermitage, Pontoise.

George T. M. Shackelford and Fronia E. Wissman, Impressions of Light: The French Landscape from Corot to Monet, exh. cat. (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 2002), 164n2, as Wooded Landscape at the Hermitage.

Marco Goldin and Rochelle Keene, Da Corot a Monet: Opere impressioniste e post-impressioniste dalla Johannesburg Art Gallery, exh. cat. (Conegliano, Italy: Linea d’ombra Libri, 2003), 64, as Sottobosco all’Hermitage.

Terence Maloon, Camille Pissarro, exh. cat. (London: Art Gallery of New South Wales, 2005), 113.

Joachim Pissarro and Claire Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Catalogue critique des peintures; Critical Catalogue of Paintings (New York: Wildenstein Institute Publications, 2005), no. 614, pp. 1:366, 371, 381, 384, 396, 405, 408, 411, 413; 2:413–14, (repro.), as Vue de l’Hermitage à travers les arbres, Pontoise.

Deborah Emont Scott, ed., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collection, 7th ed. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2008), 121, (repro.), as Wooded Landscape at L’Hermitage, Pontoise.

Marilyn Stokstad, Art History, 3rd ed. (New Jersey: Upper Saddle River, 2008), 1032, (repro.), as Wooded Landscape at L’Hermitage, Pontoise.

Stephen Eisenman, ed., From Corot to Monet: The Ecology of Impressionism, exh. cat. (Milan: Skira, 2010), 302.

Markus Müller, Camille Pissarro: Mit den Augen eines Impressionisten (München: Hirmer, 2013), 14, (repro.), as Blick durch die Bäume auf L’Hermitage, Pontoise.

Connie Homburg et al., Van Gogh: Into the Undergrowth, exh. cat. (Cincinnati: Cincinatti Art Museum, 2016), 128.

Catherine Futter et al., Bloch Galleries: Highlights from the Collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2016), 66, (repro.), as Wooded Landscape at L’Hermitage, Pontoise.

Christophe Duvivier, Camille Pissarro: impressions gravées, exh. cat. (Paris: Somogy, 2017), 28, 42, (repro.), as Vue de l’Hermitage, à travers les arbres Pontoise.

Claire Durand-Ruel and Christophe Duvivier, Camille Pissarro: le premier des impressionnistes, exh. cat. (Paris: Éditions Hazan, 2017), 53, 57, (repro.), as Vue de l’Hermitage.

Christophe Duvivier, Christophe Duvivier, Pissarro à Pontoise (Cergy-Pontoise: Val d’Oise, le département, 2017), 19, (repro.), as Vue de l’Hermitage à travers les arbres, Pontoise.

Sarah Lees, Innovative Impressions: Prints by Cassatt, Degas, and Pissarro, exh. cat. (Tulsa, OK: Philbrook Museum of Art, 2018), 33, 55, 111, (repro.), as Wooded Landscape at the Hermitage, Pontoise.

Rupert Nuttle, “Pissarro’s prints: light, atmosphere and ‘plein air’,” National Gallery of Canada Magazine (December 6, 2019): http:https://www.gallery.ca/magazine/your-collection/pissarros-prints-light-atmosphere-and-plein-air, (repro.), as Wooded Landscape at l’Hermitage, Pontoise.

Christophe Duvivier and Joseph Helfenstein, eds., Camille Pissarro: The Studio of Modernism, exh. cat. (Munich: Prestel, 2021), 81, 83n36.