![]()

Edgar Degas, Dancer Making Points, ca. 1874–76

| Artist | Edgar Degas, French, 1834–1917 |

| Title | Dancer Making Points |

| Object Date | ca. 1874–76 |

| Alternate and Variant Titles | Danseuse faisant des pointes; Le Commencement des ‘Pirouettes sur la Pointe en Dedans’ |

| Medium | Pastel and gouache on paper mounted on board |

| Dimensions (Unframed) | 19 1/4 x 14 1/2 in. (48.9 x 36.8 cm) |

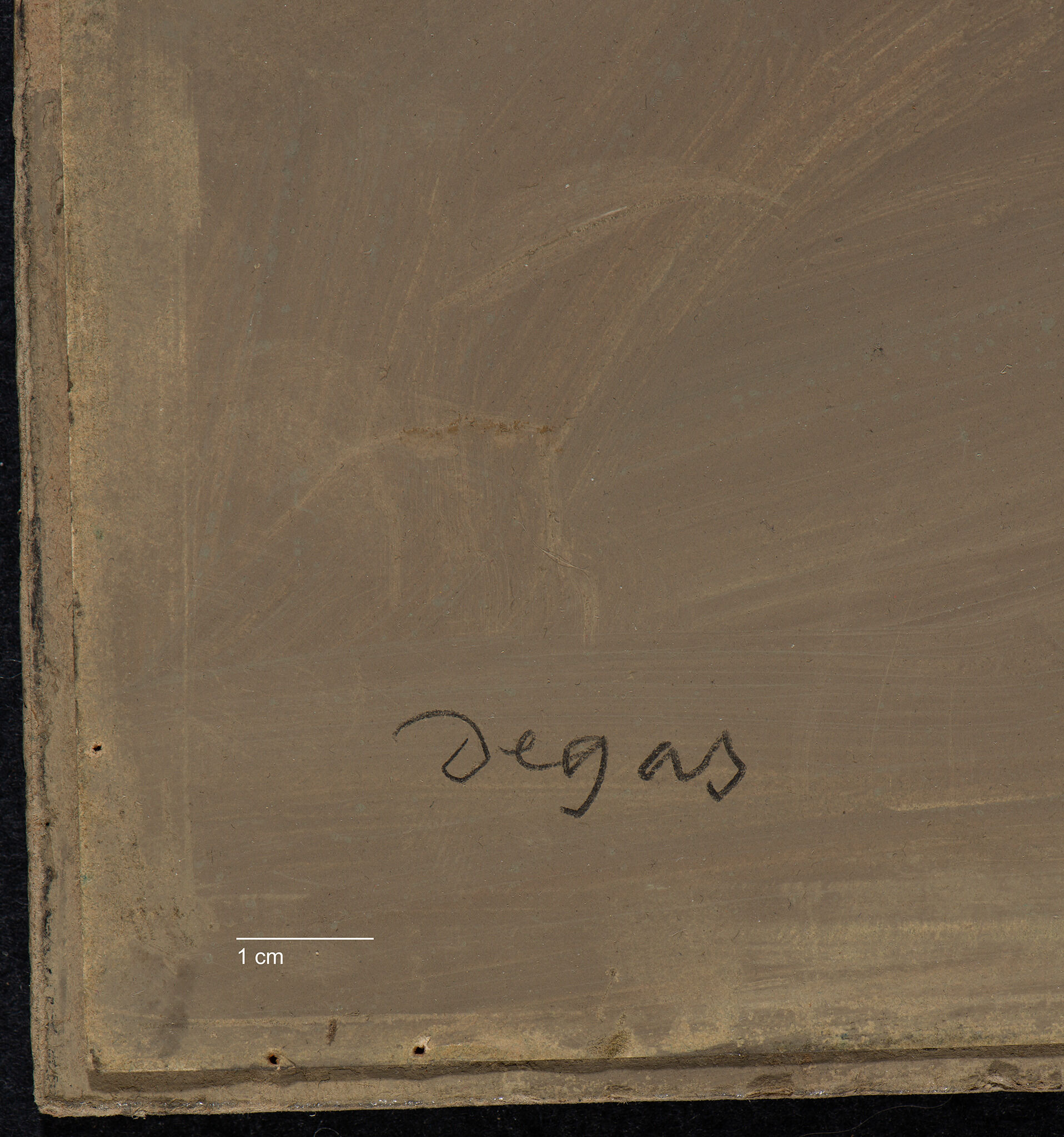

| Signature | Signed lower left: Degas |

| Credit Line | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Gift of Henry W. and Marion H. Bloch, 2008.53 |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Meghan L. Gray, “Edgar Degas, Dancer Making Points, ca. 1874–76,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.616.5407.

MLA:

Gray, Meghan L. “Edgar Degas, Dancer Making Points, ca. 1874–76,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.616.5407.

“Yesterday I spent the whole day in the studio of a strange painter called Degas,” wrote Edmond de Goncourt on February 13, 1874:

After a great many essays and experiments and trial shots in all directions, he has fallen in love with modern life, and out of all the subjects in modern life has chosen washerwomen and ballet-dancers. When you come to think of it, it is not a bad choice. It is a world of pink and white, of female flesh in lawn [a type of cotton fabric] and gauze, the most delightful of pretexts for using pale, soft tints. . . . Among all the artists I have met so far, he is the one who has best been able, in representing modern life, to catch the spirit of that life.1Quoted and translated in Christopher Lloyd, Edgar Degas: Drawings and Pastels (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2014), 117–18.

Edgar Degas’s fascination with ballerinas began in 1871, when he was thirty-seven years old.2Degas was thirty-three when he began his first major ballet painting (Portrait of Mlle Fiocre in the Ballet “La Source,” ca. 1867–68, Brooklyn Museum). Yet that picture is not about the act of dancing, and indeed the viewer’s only clue to the subject is Degas’s inclusion of the ballet slippers tossed onto the stage floor. Dancers in tutus, en pointeen pointe: A term used in ballet to mean “on the tips of the toes.”, warming up in the rehearsal room, or performing for an audience took center stage in his art. The artist remained enamored of the subject for the rest of his life, creating more than six hundred images of ballerinas, encompassing over half of his total oeuvre. Numerous drawings, pastels, and prints in this genre allow us to better understand Degas’s working method and also refine the date for the Nelson-Atkins pastel.

Raised in a musical family, Degas enjoyed attending the opera. In the nineteenth century, the lavish Parisian Opéra, with multiple acts, large choruses, and several soloists, also included a ballet. Between arias, the dance corps took the stage and sometimes stole the show. As Kimberly A. Jones has shown, the real allure for most opera attendees was the ballet.3People watching was another key attraction of the Opéra; see Henri Loyrette et al., Degas at the Opéra, exh. cat. (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2020). While Degas loved all aspects of the opera and was friendly with many of the musicians, dancers, and performers, he was most captivated artistically by the ballet.

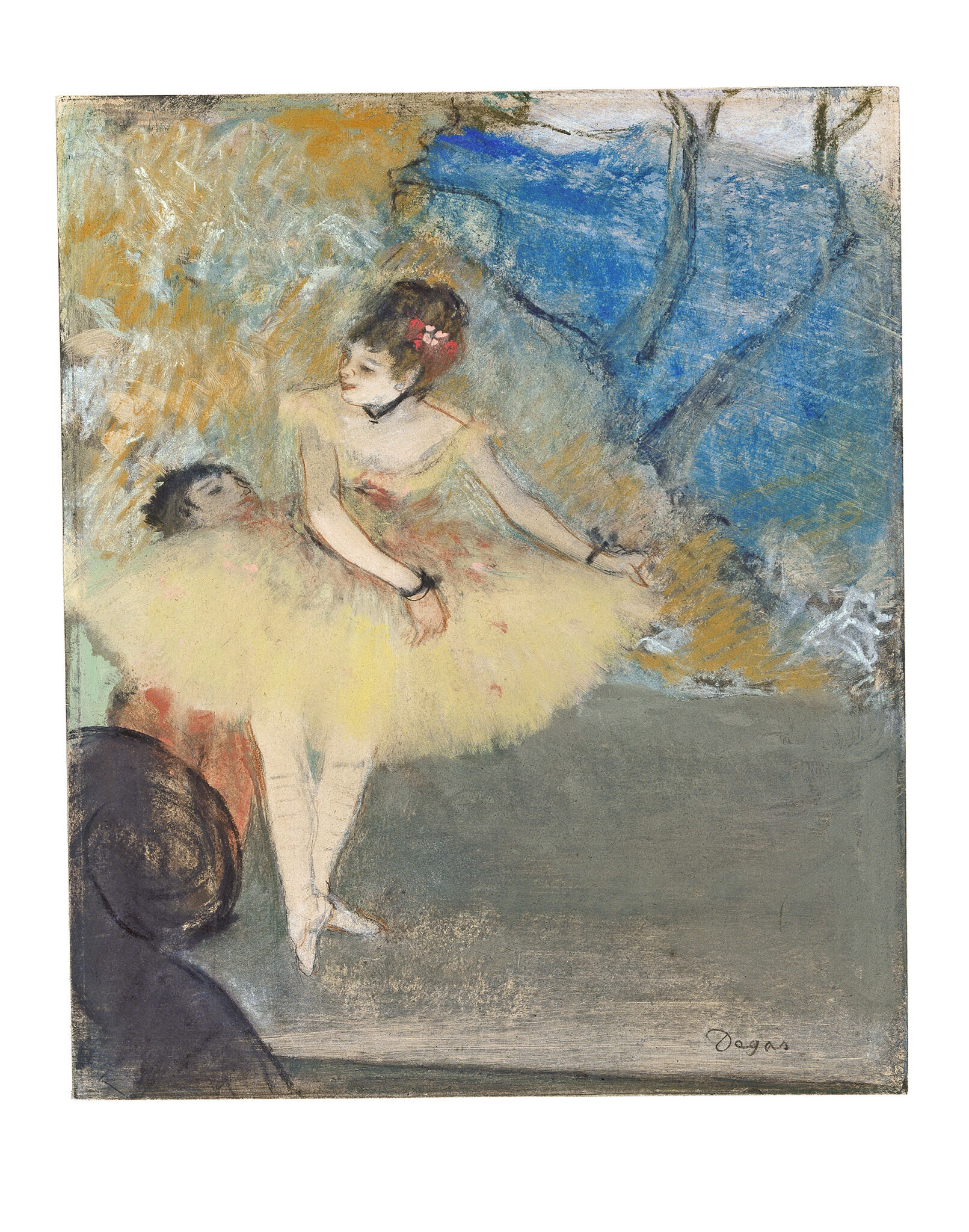

In the Nelson-Atkins pastel, Degas depicts a dancer as if at a dress rehearsal or in the middle of a performance, judging by the colorful costume that is not the traditional white practice tutu.4Jill DeVonyar and Richard Kendall, Degas and Music, exh. cat. (Glen Falls, NY: Hyde Collection, 2009), 95. Attired in a full yellow tutu with bright accents of red silk flowers and ribbons, the ballerina points her left toe, her weight balancing on her right leg. Her left arm reaches across her body, while her right arm stretches to the side. The diaphanous tutu glows in the lights of the stage, while her pink-tinged skin and tights are highlighted with white. Degas drew eye-catching strokes of red pastelpastel: A type of drawing stick made from finely ground pigments or other colorants (dyes), fillers (often ground chalk), and a small amount of a polysaccharide binder (gum arabic or gum tragacanth). While many artists made their own pastels, during the nineteenth century, pastels were sold as sticks, pointed sticks encased in tightly wound paper wrappers, or as wood encased pencils. Pastels can be applied dry, dampened, or wet, and they can be manipulated with a variety of tools including paper stumps, chamois cloth, brushes, or fingers. Pastel can also be ground and applied as a powder, or mixed with water to form a paste. Pastel is a friable media, meaning that it is powdery or crumbles easily. To overcome this difficulty, artists have used a variety of fixatives to prevent image loss. at the back of her head to suggest an elegant decoration in her rich brown hair. The red and yellow in her dress play with the contrasting colors of green and blue in the background, where Degas laid the gouachegouache: A term originating in eighteenth century France, which, historically, refers to an opaque paint consisting of colored pigments or dyes, a white opacifying pigment, and a polysaccharide binder, usually gum arabic. Traditional gouache recipes sometimes include honey as a humectant. Although twentieth century and twenty-first century gouache paints are often visually indistinguishable from historic gouache paints, modern gouache paints include a variety of additives that produce a reliably uniform paint in terms of tint and handling properties. on in painterly patches of dark and light green and dashes of blue. Always experimental, he scribbled blue pastel across the gouache, creating depth and interest in the foliated backdrop. One can imagine a viewer seated in a loge above the stage, looking down at the dancer. From this angle, the wide brown floorboards take up half the picture, their emptiness balancing the busy patterning of the scenery and luminous costume of the dancer.

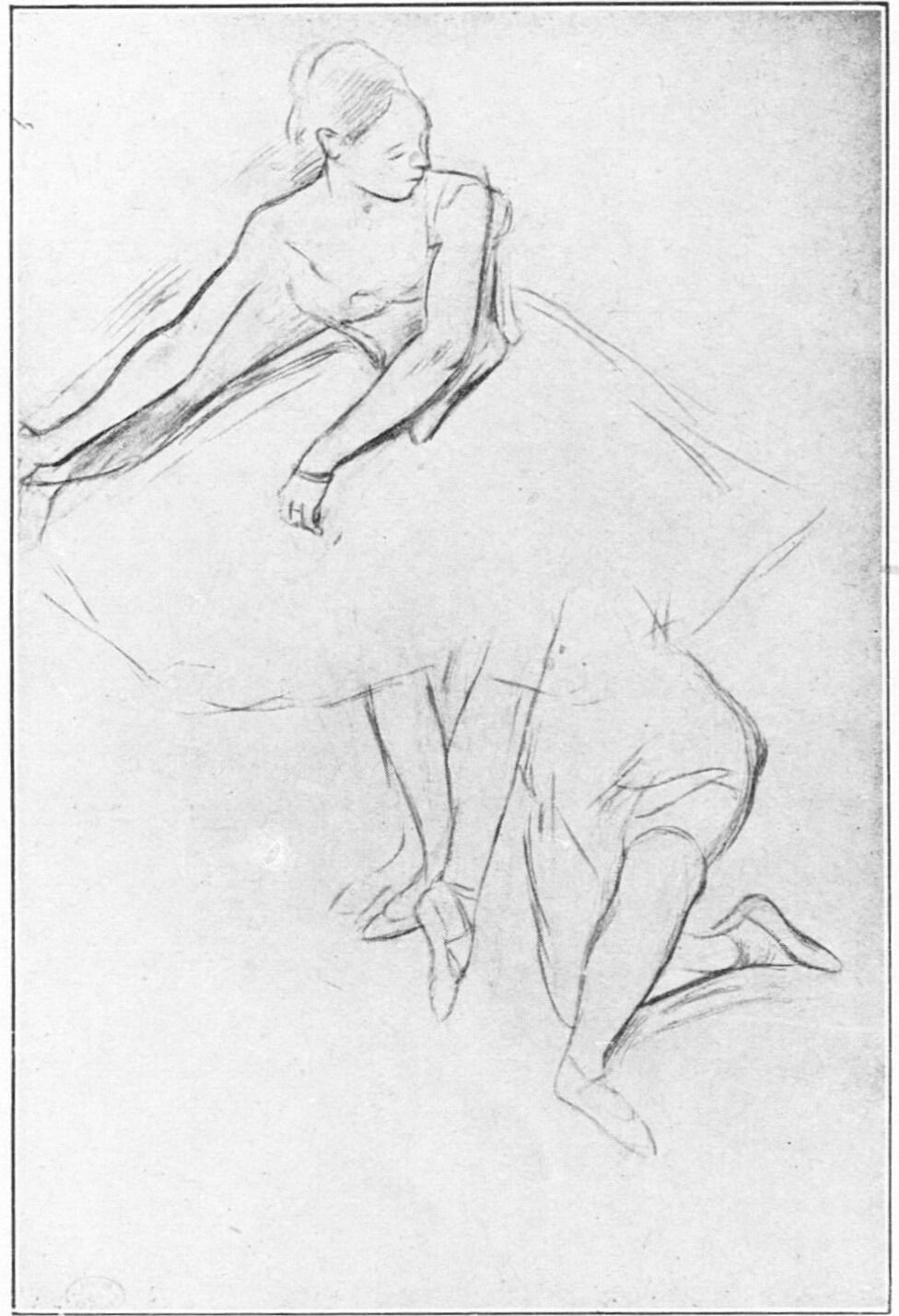

Belying the presumed realism of his images and running counter to the Impressionists’ preference for painting from life, Degas composed most of his ballet images in his studio. He hired ballerinas to pose for him, but instead of creating a finished picture directly from the subject, he relied on drawings sketched from the model. Then he reworked and revised them continuously over many years and in various media.7Richard Kendall and Jill DeVonyar, Degas and the Ballet: Picturing Movement (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2011), 42–43.

The most obvious difference between the two works is the omission of the kneeling figure. With the drawing, one can imagine Degas working quickly to sketch in the bent knees and protruding buttocks of the second figure before running out of room where the first dancer’s legs and skirt begin. By omitting this figure from the pastel, Degas created an elegant soloist in the spotlight, but in later works, the artist included this half-thought, creating those awkward and realistic moments he so loved to depict. Degas repeated this motif in two monotypesmonotype: A type of planographic print where a design is drawn or painted on a non-porous surface, such as a printing plate or glass, and the design is transferred, in reverse, to paper by manual pressure, or pressure from a printing press. The monotype process produces unique prints because the ink is depleted each time paper comes in contact with the matrix. The first print is the strongest in terms of tone and contrast, and the quality decreases with each subsequent print. See also dark-field monotype and cognate., although the composition is reversed due to the printing process. The monotypes are diminutive, measuring less than half the size of the pastel and drawing. In Dancing on Stage (Fig. 3) from 1876 to 1877, now at the Statens Museum for Kunst in Copenhagen, Degas reused the two figures from the drawing, but he raised the kneeling figure up, aligning the two dancers’ feet. In this work, he did not add the upper half of the missing body. However, with its cognatecognate: In monotypes, cognates are multiple prints pulled from an inked image on a plate. The first print is usually the strongest, and the image quality reduces with each subsequent pull. It is usually possible to pull only two or three prints before the image becomes unreadable. See also monotype., a monotype worked over in pastel now at the Kunst Museum Winterthur in Switzerland (Fig. 4), dated around 1876, Degas added a man’s curious face peering over the back of the ballerina’s skirt. His lower body is obscured by the scroll of a bass, which rises out of the orchestra pit in the foreground.

Fig. 3. Edgar Degas, Dancing on Stage, 1876–77, monotype on wove paper, plate: 8 9/16 x 6 15/16 in. (21.7 x 17.7 cm), sheet: 9 3/4 x 8 1/8 in. (24.8 x 20.7 cm), Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen

Fig. 3. Edgar Degas, Dancing on Stage, 1876–77, monotype on wove paper, plate: 8 9/16 x 6 15/16 in. (21.7 x 17.7 cm), sheet: 9 3/4 x 8 1/8 in. (24.8 x 20.7 cm), Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen

Fig. 4. Edgar Degas, Dancer, ca. 1876, pastel and opaque watercolor over monotype on paper, plate: 8 7/16 x 6 7/8 in. (21.5 x 17.5 cm), sheet: 8 7/16 x 6 7/8 in. (21.5 x 17.5 cm), Kunst Museum Winterthur, anonymous gift, 2013 (Inv. No. Z.2013.6). © SIK-ISEA, Zürich (Jean-Pierre Kuhn)

Fig. 4. Edgar Degas, Dancer, ca. 1876, pastel and opaque watercolor over monotype on paper, plate: 8 7/16 x 6 7/8 in. (21.5 x 17.5 cm), sheet: 8 7/16 x 6 7/8 in. (21.5 x 17.5 cm), Kunst Museum Winterthur, anonymous gift, 2013 (Inv. No. Z.2013.6). © SIK-ISEA, Zürich (Jean-Pierre Kuhn)

In the Nelson-Atkins pastel, Degas originally centered the soloist on the empty stage, in a composition similar to the drawing, in which her skirt extends to the lateral edges of the paper. Before finishing the pastel, however, the artist adjoined a two-inch vertical strip of paper to the right edge. With this addition, Degas counterbalanced the figure in motion with the empty space of the floor and backdrop. The larger sheet and the strip are both heavy, slightly textured, tan paper, and thick gouache fills in the gap between the joined pages. Lines of the floorboards also extend across the gap, indicating that Degas was actively revising the composition when he affixed the strip of paper.10See Rachel Freeman’s accompanying technical entry. Degas included this open stage space in the two monotypes as well. While it is possible that he used the Winterthur pastel over monotype as a basis for the Nelson-Atkins pastel, it seems unlikely. If he was closely following the monotype as an example, then he would have incorporated the empty stage space in the Kansas City version from the beginning, rather than adding the paper strip after starting it.

The cropped left hands in the two monotypes seem inexplicable until they are compared with the Nelson-Atkins pastel. In the two monotypes, the hands simply disappear illogically. This is particularly evident in the pastel over monotype, in which Degas outlined the hand and thumb, and the fingers are cut off at the knuckle.11A case could be made that the fingers are folded over the dancer’s skirt, but this seems unlikely given the absence of the yellow tutu in that spot. Comparison with Dancer Making Points explains the omission, because in the pastel prototype, the dancer’s hand extends to the edge of the paper and the fingers fade into the background.12On close inspection, the hand is tipped toward the viewer, with the thumb extending toward the floor and the little finger just visible at the top of the hand.

Degas made his first known monotype with the help of his friend Ludovic-Napoléon Lepic around 1876 (see more about this monotype and its cognate, Rehearsal of the Ballet, which was also built up in pastel, in this catalogue). It is therefore unlikely that the Winterthur and Copenhagen monotypes were created before 1876, and indeed sometimes they are dated later, to 1877.13The Copenhagen monotype is dated to 1877 in the Strange New Beauty exhibition, but on the Copenhagen website it is dated to 1876–77; see Jodi Hauptman, Degas: A Strange New Beauty, exh. cat. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2016), no. 26, p. 228; and ”Edgar Degas: Danser på scenen,“ SMK Open (public collection database for the Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen), accessed May 2020, https://open.smk.dk/en/artwork/image/KKS9158?q=degas&page=1. It was dated to ca. 1878–80 in Eugenia Parry Janis, Degas Monotypes: Essay, Catalogue and Checklist, exh. cat. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University/ Fogg Art Museum, 1968), no. 4, unpaginated. The Winterthur pastel and watercolor over monotype is dated to ca. 1876–77 in the Strange New Beauty exhibition, suggesting its completion anytime within that range; see Hauptman, Degas: A Strange New Beauty, no. 25, p. 228. The Kunst Museum Winterthur dates it to ca. 1876 (see correspondence from Ludmilla Sala, Registrar Sammlung, Kunst Museum Winterthur, to the author, November 17, 2021, NAMA curatorial files), whereas Michel Schulman’s online catalogue raisonné dates it to ca. 1877; see Michel Schulman, “Dancers on Stage,” Online Critical Catalogue of Paintings and Pastels by Edgar Degas (2019), accessed November 18, 2021, https://www.degas-catalogue.com/danseuses-en-scene-2390.html. If the Nelson-Atkins pastel was a basis for the two monotypes, then it cannot be dated later than 1876. Pickvance argued that the pastel could be dated as early as 1874, based on its similarity with the drawing (Fig. 2) but also due to its shared viewpoint and lighting and the similarity of its model to those in Two Dancers on a Stage (Fig. 1).14Pickvance, “Degas’s Dancers: 1872–6,” 264. The Courtauld painting is securely dated to 1874 because it was exhibited by Durand-Ruel that year and then purchased soon thereafter by Captain Henry Hill of Brighton. With the histories of these related works, we are better able to establish the earliest possible date and latest possible date for Dancer Making Points.

The Nelson-Atkins pastel has been known as Dancer Making Points throughout its history,15When it first appeared on the market at the sale of Georges Urion at Galerie Georges Petit in 1927, the pastel was called Danseuse faisant des pointes. See Catalogue de Tableaux Modernes. . . , Pastel par Degas, Sculptures par Carpeaux et Rodin, Commode d’époque Régence, Tapisseries Anciennes d’Aubusson, Bruxelles, Felletin, Flandres et Florence, Composant la Collection de Monsieur G. U. . . . (Paris: Galerie Georges Petit, May 30–31, 1927), 1. but in terms of describing the ballerina’s full motions, this title is limited. “Making points” only refers to the left foot, which seems about to draw forms upon the floor, and while Joachim Pissarro found poetry in that title,16Brettell and Pissarro, Manet to Matisse, 82. it does not explain what the arms or the rest of the body are doing. Lillian Browse, who was an art dealer and art historian who also trained as a ballet dancer, was the first to attempt to explain the full body’s position in this picture. Suggesting an alternate title of The Beginning of “Pirouettes sur la Pointe en Dedans,” Browse determined that the dancer is about to turn in place on her pointed toe.17Browse, Degas Dancers, 384. Browse intentionally discarded some titles given to her so that she could more accurately describe the dancer’s position in modern balletic terms. Although she did not know the owner at the time of the 1949 publication, she received the photo from Durand-Ruel, who had titled the pastel Danseuse faisant des pointes. She also explained that the foot is pointe tendue, meaning that it is stretched into a pointed position.

However, Mary Frances Ivey, an art historian and student of ballet, has posited that the ballerina is making a piqué turn, or a turn from a bent leg to a straight leg.18Email and verbal communication with the author. I am very grateful for Ivey’s generous gift of her time and knowledge as she explained these movements to me. Accordingly, her arms are also preparing for that same turn. The ballerina’s left arm (the one in front of her body) is already in first position, and her right arm, in second position, will meet the left as she steps (or piqués) into her turn. In Ivey’s view, it is unlikely that the dancer is about to pirouette, as per Browse’s opinion, because it is not customary to launch from a pointe tendue. In a piqué turn, dancers always turn en dedans, or over the shoulder. The direction of the model’s head indicates where she is going. She looks over to the empty stage, making Degas’s addition of the strip of paper more significant. The dancer is arrested in the moment just before she spins across the floor. If Browse’s supposition were true, the ballerina would merely go on to pirouette in place.

Dancer Making Points was unknown in the art market until 1927, when it was sold by Georges Urion, a Parisian department store owner who mismanaged his funds, necessitating the liquidation of his art collection.19Catalogue de Tableaux Modernes . . . Pastel par Degas, 1. See also Jean Pierre Petit’s Family tree, notes on Georges Urion, accessed November 18, 2021, https://gw.geneanet.org/pygmalion?n=urion&oc=&p=georges. The pastel caught the attention of buyers and critics, and it obtained the sale’s highest price of two hundred thousand francs, which was paid by Galeries Durand-Ruel.20”L’Art et la Curiosité,“ Le Figaro, no. 151 (May 31, 1927): 4. Two years later, the dealer sold the pastel to Anna Eugenia Clark of New York, the second wife of the late copper baron William Andrews Clark. Possibly at her side when the purchase was made was Anna’s twenty-three-year-old daughter, Huguette Marcelle Clark, an artist in her own right.21Bill Dedman and Paul Clark Newell Jr., Empty Mansions: The Mysterious Life of Huguette Clark and the Spending of a Great American Fortune (New York: Ballantine Books, 2013), 128, 290–91. Clark would eventually inherit the pastel after her mother’s death in 1963, by which time she was debilitatingly reclusive. For the last twenty years of her life, Clark lived permanently in a private room of a hospital, and shortly after she moved there the pastel went missing from her unoccupied New York apartment.22Dedman and Newell, Empty Mansions, 291–93. Neither she nor her representatives reported it missing at that time. Marion and Henry Bloch of Kansas City purchased the pastel in good faith in 1993; however, once they learned of the theft in 2008, they entered into discussions with Clark’s representatives to resolve the pastel’s ownership amicably. As a result, it came to the museum under an agreement between Clark and the Blochs in 2008.

Dancer Making Points, with its gestural line and feeling of immediacy, belies the extensive thought Degas put into the subject, spanning as many as two to three years. The dancer’s motion is suspended, as if a viewer has just entered the theater loge to catch a glimpse of a popular ballet during the Parisian Opéra. With her foot in pointe tendue and her gaze arrested on the empty stage before her, she might spin across the floor at any moment.

Notes

-

Quoted and translated in Christopher Lloyd, Edgar Degas: Drawings and Pastels (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2014), 117–18.

-

Degas was thirty-three when he began his first major ballet painting (Portrait of Mlle Fiocre in the Ballet “La Source,” ca. 1867–68, Brooklyn Museum). Yet that picture is not about the act of dancing, and indeed the viewer’s only clue to the subject is Degas’s inclusion of the ballet slippers tossed onto the stage floor.

-

People-watching was another key attraction of the Opéra; see Henri Loyrette et al., Degas at the Opéra, exh. cat. (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2020).

-

Jill DeVonyar and Richard Kendall, Degas and Music, exh. cat. (Glen Falls, NY: Hyde Collection, 2009), 95.

-

Paul A. Lemoisne, Degas et son œuvre, vol. 2. (Paris: Paul Brame et C. M. De Hauke, 1941), no. 558, pp. 312–13. Following this dating, see Franco Russoli and Fiorella Minervino, L’opera completa di Degas (Milan: Rizzoli Editore, 1970), no. 737, p. 120; and Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 82–85, 158. On the other hand, the famous Impressionist dealership Durand-Ruel dated the pastel later, to 1882, when it entered their inventory in 1927. See emails from Paul-Louis Durand-Ruel and Flavie Durand-Ruel, Durand-Ruel et Cie., Paris, to Nicole Myers, NAMA, January 11, 2016, and to Meghan Gray, NAMA, February 5 and 9, 2016, NAMA curatorial file. Lillian Browse proposed that the pastel was made around 1880–83, although she had not seen Lemoisne’s catalogue raisonné yet; see Lillian Browse, Degas Dancers (Boston: Boston Book and Art Shop, 1949), 384.

-

Ronald Pickvance, “Degas’s Dancers: 1872–6,” Burlington Magazine 105, no. 723 (1963): 264, 264n70.

-

Richard Kendall and Jill DeVonyar, Degas and the Ballet: Picturing Movement (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2011), 42–43.

-

Pickvance, “Degas’s Dancers: 1872–6,” 264.

-

See also the yellow tutus in Yellow Dancers (In the Wings) (1874/1876; Art Institute of Chicago). The green foliated backdrop is similar to that in the Nelson-Atkins example, but the tone of the tutus is tinged with green, and the dancers are decorated with peach-colored flowers rather than red.

-

See Rachel Freeman’s accompanying technical entry.

-

A case could be made that the fingers are folded over the dancer’s skirt, but this seems unlikely given the absence of the yellow tutu in that spot.

-

On close inspection, the hand is tipped toward the viewer, with the thumb extending toward the floor and the little finger just visible at the top of the hand.

-

The Copenhagen monotype is dated to 1877 in the Strange New Beauty exhibition, but on the Copenhagen website it is dated to 1876–77; see Jodi Hauptman, Degas: A Strange New Beauty, exh. cat. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2016), no. 26, p. 228; and “Edgar Degas: Danser på scenen,” SMK Open (public collection database for the Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen), accessed May 2020, https://open.smk.dk/en/artwork/image/KKS9158?q=degas&page=1. It was dated to ca. 1878–80 in Eugenia Parry Janis, Degas Monotypes: Essay, Catalogue and Checklist, exh. cat. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University/ Fogg Art Museum, 1968), no. 4, unpaginated. The Winterthur pastel and watercolor over monotype is dated to ca. 1876–77 in the Strange New Beauty exhibition, suggesting its completion anytime within that range; see Hauptman, Degas: A Strange New Beauty, no. 25, p. 228. The Kunst Museum Winterthur dates it to ca. 1876 (see correspondence from Ludmilla Sala, Registrar Sammlung, Kunst Museum Winterthur, to the author, November 17, 2021, NAMA curatorial files), whereas Michel Schulman’s online catalogue raisonné dates it to ca. 1877; see Michel Schulman, “Dancers on Stage,” Online Critical Catalogue of Paintings and Pastels by Edgar Degas (2019), accessed November 18, 2021, https://www.degas-catalogue.com/danseuses-en-scene-2390.html.

-

Pickvance, “Degas’s Dancers: 1872–6,” 264.

-

When it first appeared on the market at the sale of Georges Urion at Galerie Georges Petit in 1927, the pastel was called Danseuse faisant des pointes. See Catalogue de Tableaux Modernes. . . , Pastel par Degas, Sculptures par Carpeaux et Rodin, Commode d’époque Régence, Tapisseries Anciennes d’Aubusson, Bruxelles, Felletin, Flandres et Florence, Composant la Collection de Monsieur G. U. . . . (Paris: Galerie Georges Petit, May 30–31, 1927), 1.

-

Brettell and Pissarro, Manet to Matisse, 82.

-

Browse, Degas Dancers, 384. Browse intentionally discarded some titles given to her so that she could more accurately describe the dancer’s position in modern balletic terms. Although she did not know the owner at the time of the 1949 publication, she received the photo from Durand-Ruel, who had titled the pastel Danseuse faisant des pointes.

-

Email and verbal communication with the author. I am very grateful for Ivey’s generous gift of her time and knowledge as she explained these movements to me.

-

Catalogue de Tableaux Modernes . . . Pastel par Degas, 1. See also Jean Pierre Petit’s Family tree, notes on Georges Urion, accessed November 18, 2021, https://gw.geneanet.org/pygmalion?n=urion&oc=&p=georges.

-

“L’Art et la Curiosité,” Le Figaro, no. 151 (May 31, 1927): 4.

-

Bill Dedman and Paul Clark Newell Jr., Empty Mansions: The Mysterious Life of Huguette Clark and the Spending of a Great American Fortune (New York: Ballantine Books, 2013), 128, 290–91.

-

Dedman and Newell, Empty Mansions, 291–93.

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Rachel Freeman, “Edgar Degas, Dancer Making Points, ca. 1874–76,” technical entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.616.2088.

MLA:

Freeman, Rachel. “Edgar Degas, Dancer Making Points, ca. 1874–76,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.616.2088.

Although the subject matter is visually similar to Degas’s Rehearsal of the Ballet (F73-30), Dancer Making Points does not have the handling problems (and subsequent condition issues) seen with the former work.

Degas’s media almost obscures the paper. The thinnest areas of media coverage are in the stage floor and the dancer’s skirt. The artist began with an underdrawing in fine pointed black pastel or charcoal (Fig. 5). The focus of the composition, the dancer, was executed first, and then the background and floor were laid in around her. Portions of the dancer were overlapped by the surrounding media, such as the proper left side of the skirt, and Degas corrected these mistakes toward the end of the working process.

Fig. 6. Dancer Making Points, ca. 1874–76, as it appears when exposed to ultraviolet radiation

Fig. 6. Dancer Making Points, ca. 1874–76, as it appears when exposed to ultraviolet radiation

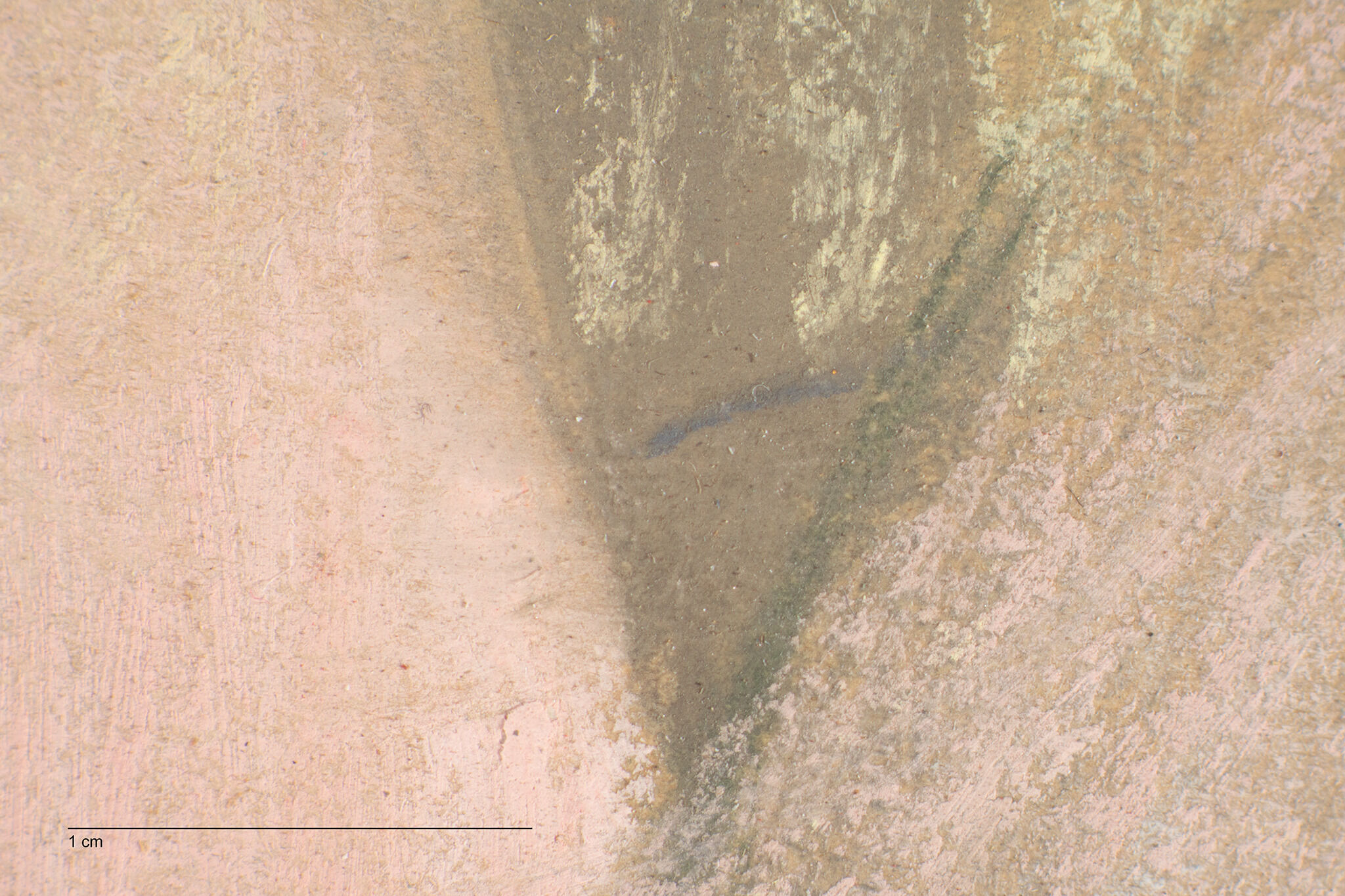

Fig. 7. Photomacrograph of the dancer’s head and sternum, Dancer Making Points, ca. 1874–76. This image shows the differences between the two reds used to depict the trim on the costume as well as the blue media on the dancer’s sternum.

Fig. 7. Photomacrograph of the dancer’s head and sternum, Dancer Making Points, ca. 1874–76. This image shows the differences between the two reds used to depict the trim on the costume as well as the blue media on the dancer’s sternum.

Fig. 8. To depict the floorboards, Degas dragged a brush with gray paint across the still wet paint of the floor, Dancer Making Points, ca. 1874–76

Fig. 8. To depict the floorboards, Degas dragged a brush with gray paint across the still wet paint of the floor, Dancer Making Points, ca. 1874–76

Fig. 9. Photomicrograph of the graphite pencil line that defines the floorboards behind the dancer (and between her knees), Dancer Making Points, ca. 1874–76. The mark was an afterthought and applied to dry paint.

Fig. 9. Photomicrograph of the graphite pencil line that defines the floorboards behind the dancer (and between her knees), Dancer Making Points, ca. 1874–76. The mark was an afterthought and applied to dry paint.

Fig. 10. Photomicrograph of an underlayer of green pastel, applied as a wash (indicated with a red arrow), along the upper edge at right, Dancer Making Points, ca. 1874–76

Fig. 10. Photomicrograph of an underlayer of green pastel, applied as a wash (indicated with a red arrow), along the upper edge at right, Dancer Making Points, ca. 1874–76

Fig. 11. The artist’s signature, Dancer Making Points, ca. 1874–76

Fig. 11. The artist’s signature, Dancer Making Points, ca. 1874–76

Although the degree of media flaking is not as great as seen on Rehearsal for the Ballet, there is some flaking and instability in the paint applications used for the theater flats. This is mostly present in the right half of the image, where the damage makes an inverted “V”-shaped pattern, which might indicate that the artwork was illuminated with a picture lamp at some point during its history. Paper conservator Nancy Heugh successfully treated the artwork in 2016 for lifting of the primary support.

Notes

-

The description of paper thickness and texture follows the standard set forth in Elizabeth Lunning and Roy Perkinson, The Print Council of America Paper Sample Book: A Practical Guide to the Description of Paper (Boston: Print Council of America, 1996), unpaginated.

-

In this case, there is no good match for the paper color in Lunning and Perkinson, The Print Council of America Paper Sample Book.

-

In this entry, paperboard refers to “stiff or thick ‘paper’ which may range from a card of 0.20 mm in thickness to 5 mm or more and vary in composition from pure rag to wood, straw or other substances having little or no affinity with ‘paper’ beyond the method of manufacture.” See E. J. Labarre, A Dictionary of Paper-Making Terms (Amsterdam: N. V. Swets and Zeitlinger, 1937), 208–9.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Edgar Degas, Dancer Making Points, ca. 1874–76,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.616.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Edgar Degas, Dancer Making Points, ca. 1874–76,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.616.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Edgar Degas, Dancer Making Points, ca. 1874–76,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.616.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Edgar Degas, Dancer Making Points, ca. 1874–76,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.616.4033.

Georges Urion (1865–1954), Paris, by May 31, 1927;

Purchased at his sale, Tableaux Modernes par Altmann, Barye, Boggs, Bouche, Boudin, Braquaval, Carrière, Cézanne, Chéret, Corot, Cross, Dufeu, Dufy, Flandrin, Forain, Gauguin, Van Gogh, de Groux, Guillaumin, Hervier, Isabey, Jongkind, Lebourg, Lemordant, Lépine, Luce, Marquet, Monticelli, Pissarro, Raffaelli, Renoir, K.-X. Roussel, Sisley, Tassaert, Ten Cate, Utrillo, Vignon, Vuillard, Willette, etc., Pastel par Degas, Sculptures par Carpeaux et Rodin, Commode d’époque Régence, Tapisseries Anciennes d’Aubusson, Bruxelles, Felletin, Flandres et Florence, Composant la Collection de Monsieur G. U. . . . , Galerie Georges Petit, Paris, May 30–31, 1927, lot 26, as La Danseuse faisant des pointes, by Galerie Durand-Ruel, Paris, deposit no. LD 13176, for the account of Durand-Ruel, New York, stock no. 5019, as Danseuse faisant des pointes, May 31, 1927–November 11, 1929 [1];

Purchased from Durand-Ruel, New York, by Anna Eugenia Clark (née La Chapelle, 1878–1963), New York and Santa Barbara, CA, November 11, 1929–October 11, 1963 [2];

Inherited by her daughter, Huguette Marcelle Clark (1906–2011), New York, 1963–prior to November 1992 [3];

Placed on sale at Peter Findlay Gallery, New York, ca. 1992–93;

Purchased from Peter Findlay Gallery, New York, by Marion (née Helzberg, 1931–2013) and Henry (1922–2019) Bloch, Shawnee Mission, KS, 1993–October 27, 2008 [4];

Returned by the Blochs to Huguette Clark, October 27, 2008 [5];

Simultaneously, Huguette Clark gifted to The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, October 27, 2008.

Notes

[1] The painting was transferred from Durand-Ruel, Paris, to Durand-Ruel, New York, in August 1927. See emails from Paul-Louis Durand-Ruel and Flavie Durand-Ruel, Durand-Ruel et Cie., Paris, to Nicole Myers, NAMA, January 11, 2016, and to Meghan Gray, NAMA, February 5 and 9, 2016, NAMA curatorial file. The catalogue raisonné erroneously cites Georges Lurcy (or Lévy, 1891–1953), as an owner of the pastel, but Durand-Ruel have no indication of a sale to him or to any other person before November 11, 1929 when it was sold to Mrs. W. A. Clark. See Paul A. Lemoisne, Degas et son œuvre, vol. 2 (Paris: Paul Brame et C.M. De Hauke, 1946), no. 558.

[2] See emails from Paul-Louis Durand-Ruel and Flavie Durand-Ruel, Durand-Ruel et Cie., Paris, to Nicole Myers, NAMA, January 11, 2016, and to Meghan Gray, NAMA, February 5 and 9, 2016, NAMA curatorial file. Contrary to Bill Dedman and Paul Clark Newell, Jr., Empty Mansions: The Mysterious Life of Huguette Clark and the Spending of a Great American Fortune (New York: Ballantine Books, 2013), 128, Durand-Ruel does not record Clark’s 23-year-old daughter, Huguette Clark, as a co-purchaser of the pastel. Labels on the verso of the pastel indicate that Mrs. Clark sent the picture to dealer M. Knoedler and Co., New York, probably to have it measured for and installed in a new frame. Label No. 18809 indicates that Knoedler received the work from Mrs. Clark as early as May 20, 1929 and returned to her the following day. See email from Karen Meyer-Roux, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, to Mackenzie Mallon, NAMA, October 10, 2019, NAMA curatorial files.

[3] See email from Bill Dedman to Kathleen Leighton, NAMA, May 22, 2012, NAMA curatorial file. The painting went missing from Huguette Clark’s apartment prior to November 1992. Neither she nor her representatives reported it missing at that time.

[4] See letter from Susan L. Brody to Henry Bloch, November 7, 1994, NAMA curatorial files.

[5] After the pastel was discovered missing from Clark’s apartment in November 1992, a subsequent FBI investigation into its loss was inconclusive. In 2008, Marion and Henry Bloch, who had acquired the pastel in good faith, entered into discussions with Clark’s representatives in an effort to amicably resolve the pastel’s ownership. As a result of these discussions, Clark agreed to gift the pastel to NAMA in October 2008, and she received recognition from NAMA for the gift. Upon acceptance of Clark’s gift, NAMA loaned the pastel to the Blochs so the work could rejoin their collection of promised gifts to the museum. It remained with them until their collection was accessioned on June 15, 2015.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Edgar Degas, Dancer Making Points, ca. 1874–76,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.616.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Edgar Degas, Dancer Making Points, ca. 1874–76,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.616.4033.

Edgar Degas, The Points and Study of a Kneeling Dancer, 1874, 18 1/2 x 12 1/4 in. (47 x 31 cm), lead pencil, location unknown, illustrated in Catalogue des Tableaux, Pastels et Dessins par Edgar Degas et provenant de son atelier, dont la 4e et dernière vente aux enchères publique, après décès de l’artiste (Paris: Galerie Georges Petit, July 2–4, 1919), no. 281b, p. 244.

Edgar Degas, Dancer, ca. 1876, pastel and opaque watercolor over monotype on paper, plate: 8 7/16 x 6 7/8 in. (21.5 x 17.5 cm), sheet: 8 7/16 x 6 7/8 in. (21.5 x 17.5 cm), Kunst Museum Winterthur.

Edgar Degas, Dancers on Stage, 1876–77, monotype on wove paper, plate: 8 9/16 x 6 15/16 in. (21.7 x 17.7 cm), sheet: 9 3/4 x 8 1/8 in. (24.8 x 20.7 cm), Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen.

Edgar Degas, page 10 of Album of forty-five figure studies, ca. 1882–85, black chalk on paper, sheet: 10 9/16 x 8 5/8 in. (26.8 x 21.9 cm), The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Edgar Degas, Dancer Making Points, ca. 1874–76,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.616.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Edgar Degas, Dancer Making Points, ca. 1874–76,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.616.4033.

Exhibition of Paintings by the Master Impressionists, Durand-Ruel, New York, April 8–20, 1929, no. 4, as Danseuse faisant des pointes.

Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, June 9–September 9, 2007, no. 14, as Dancer Making Points (Danseuse faisant des pointes).

Painters and Paper: Bloch Works on Paper, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, February 20, 2017–March 11, 2018, no cat.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Edgar Degas, Dancer Making Points, ca. 1874–76,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.616.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Edgar Degas, Dancer Making Points, ca. 1874–76,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.616.4033.

Catalogue de Tableaux Modernes par. . . , Pastel par Degas, Sculptures par Carpeaux et Rodin, Commode d’époque Régence, Tapisseries Anciennes d’Aubusson, Bruxelles, Felletin, Flandres et Florence, Composant la Collection de Monsieur G. U. . . . (Paris: Galerie Georges Petit, May 30–31, 1927), 11, (repro.), as La Danseuse faisant des pointes.

Hérbert, “Notes d’un Curieux,” Le Gaulois 60, no. 18135 (May 21, 1927): 4, as Danseuse faisant des pointes.

Jacques Reylaine, “Vente prochaine,” Figaro 102, no. 144 (May 24, 1927): 4, as Danseuse faisant des pointes.

La Furetière, “La Curiosité,” Excelsior 18, no. 6,014 (May 31, 1927): 2, as Danseuse.

“L’Art et la Curiosité,” Le Figaro, no. 151 (May 31, 1927): 4, as La Danseuse faisant des pointes.

Le Vieux Collectionneur, “Les Ventes,” La Revue de L’Art 52, no. 279 (June 1927): 244, as La Danseuse faisant des pointes.

“À la Galerie Georges Petit,” Le Petit Journal 8 (June 1, 1927): 4, as Danseuse faisant des pointes.

“Art et Curiosité,” Le Journal, no. 12645 (June 1, 1927): 2, as Danseuse faisant des pointes.

La Furetière, “La Curiosité,” Excelsior 18. No. 6,015 (June 1, 1927): 2, as Danseuse faisant des pointes.

Le Rapin, “Beaux-Arts,” Comɶdia 21, no. 5264 (June 1, 1927): 2, as La Danseuse faisant des pointes.

H. R., “La Curiosité,” Comɶdia 21, no. 5265 (June 2, 1927): 3, as La Danseuse faisant des pointes.

Paul Gille, “La Curiosité,” L’Action Française 20, no. 154 (June 3, 1927): 4, as La Danseuse faisant des pointes.

Curiosa, “Revue des Ventes de Mai et Juin,” Le Gaulois artistique no. 11 (July 9, 1927): 191–92, (repro.), as La Danseuse faisant des pointes.

Exhibition of Paintings by the Master Impressionists, exh. cat. (New York: Durand-Ruel, 1929), unpaginated, (repro.), as Danseuse faisant des pointes.

“Impressionists Shown at Durand-Ruel’s,” Art News 27, no. 28 (April 13, 1929): 1, 3, (repro.), as Danseuse Faisant des Pointes.

André Fage, Le Collectionneur de Peintures Modernes (Paris: Éditions Pittoresques, 1930), 61, 154, 209, as La Danseuse faisant des pointes.

Camille Mauclair, Degas (London: William Heinemann, 1941), 141, (repro.), as Dancing Girl, Pirouetting.

Paul A. Lemoisne, Degas et son œuvre (Paris: Paul Brame et C. M. De Hauke, 1946), no. 558, pp. 2:312–13, (repro.), as Danseuses faisant des pointes.

Lillian Browse, Degas Dancers (Boston: Boston Book and Art Shop, 1949), 384, (repro.) as Le Commencement des ‘Pirouettes sur la Pointe en Dedans’.

Ronald Pickvance, “Degas’s Dancers: 1872-6,” Burlington Magazine 105, no. 723 (1963): 264, as Danseuse faisant des Pointes.

Franco Russoli and Fiorella Minervino, L’opera completa di Degas (Milan: Rizzoli Editore, 1970), no. 737, p. 120, (repro.), as Ballerina su una Punta.

Howard G. Lay, “Degas at Durand-Ruel, 1892: The Landscape Monotypes,” Print Collector’s Newsletter 9, no. 5 (1978): 147n21.

“Inaugural Exhibitions Celebrate Kansas City,” Member Magazine (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (Fall 2006): 3.

“Lasting Impressions: A Tribute to Marion and Henry Bloch,” Member Magazine (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (Fall 2007): 11, (repro.).

Steve Paul, “Pretty Pictures: Marion and Henry Bloch’s Collection of Superb Impressionist Masters,” Panache 4, no. 3 (Fall 2007): 20, 24, (repro.), as Dancer Making Points.

Alice Thorson, “A final countdown: A rare showing of impressionist paintings from the private collection of Henry and Marion Bloch is one of the inaugural exhibition the 165,000 square-foot glass-and-steel structure,” Kansas City Star (June 29, 2006): http://iw.newsbank.com.proxy.mcpl.lib.mo.us/ resources/doc/nb/news/112A442167B09948?p=WORLDNEWS.

Alice Thorson, “First Public Exhibition: Marion and Henry Bloch’s Art Collection,” Kansas City Star (June 3, 2007): http://iw.newsbank.com.proxy.mcpl.lib.mo.us/ resources/doc/nb/news/1198B96860A04798?p=WORLDNEWS, as Dancer Making Points.

Alice Thorson, “A Tiny Renoir Began Impressive Obsession,” Kansas City Star (June 3, 2007): E4, E5, Dancer Making Points.

Alice Thorson, “Marion and Henry Bloch’s Art Collection: A tiny Renoir began impressive obsession Bloch collection gets its first public exhibition—After one misstep, Blochs focused, successfully, on French paintings,” Kansas City Star (June 10, 2007): http://iw.newsbank.com.proxy.mcpl.lib.mo.us/resources/doc/nb/news/1198B96860A04798?p=WORLDNEWS.

Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 11, 15, 82–85, 158, (repro.), as Dancer Making Points (Danseuse faisant des pointes).

Alice Thorson, “Museum to get 29 impressionist works from Bloch collection,” Kansas City Star (February 5, 2010): http://iw.newsbank.com.proxy.mcpl.lib.mo.us/resources/doc/nb/news/12DAFE94152200F0?p=WORLDNEWS.

Alice Thorson, “Henry and Marion Bloch donate impressionist collection to the Nelson,” Kansas City Star (February 7, 2010): http://iw.newsbank.com.proxy.mcpl.lib.mo.us/resources/doc/nb/news/12DBA75220AC5588?p=WORLDNEWS.

Bill Dedman, “The $10 million Degas ballerina, heiress Huguette Clark and the tax man,” msnbc.com (March 15, 2012): http://openchannel.msnbc.msn.com/_news/2012/03/15/10693680-the-10-million-degas-ballerina-heiress-huguette-clark-and-the-tax-man, as Dancer Making Points or Danseuse Faisant des Pointes.

David Frese, “A collection of stories: How Henry Bloch acquired the paintings in the Nelson Gallery,” Kanas City Star (March 5, 2017), https://www.kansascity.com/entertainment/visual-arts/article136036913.html.

Alice Thorson, “Painting’s story touches Blochs, FBI and the Nelson,” Kansas City Star (March 15, 2012): http://iw.newsbank.com.proxy.mcpl.lib.mo.us/resources/doc/nb/news/13D8C3D2F1061C20?p=WORLDNEWS, as Dancer Making Points (Danseuse faisant des pointes).

Alice Thorson, “Story of ‘Dancer’ Revealed: Artwork’s Story Touches Blochs, FBI, Nelson,” Kansas City Star 132, no. 181 (March 16, 2012): A1, A4, A5, (repro.), as Dancer Making Points (Danseuse faisant des pointes).

Alice Thorson, “Lawsuits aren’t the only answer when an artwork’s origin is questionable,” Kansas City Star (May 11, 2012): http://iw.newsbank.com.proxy.mcpl.lib.mo.us/ resources/doc/nb/news/13EB5870459F83A0?p=WORLDNEWS, as Dancer Making Points.

Alice Thorson, “Lawsuits aren’t the only answer,” Kansas City Star (May 13, 2012): 58, as Dancer Making Points.

Alice Thorson, “Kansas City Art in 2012: Sights to Remember,” Kansas City Star (December 26, 2012): http://iw.newsbank.com.proxy.mcpl.lib.mo.us/ resources/doc/nb/news/1436CB47C19AC828?p=WORLDNEWS.

Bill Dedman and Paul Clark Newell, Jr., Empty Mansions: The Mysterious Life of Huguette Clark and the Spending of a Great American Fortune (New York: Ballantine Books, 2013), 128, 218-19, 291-93, 353, 356, 410n291, 434, (repro.), as Dancer Making Points.

“World-Class Bloch Art Collection Will Be on Permanent View in Renovated Galleries at the Nelson-Atkins,” Artdaily.org (April 9, 2015): http://artdaily.com/news/77729/World-class-Bloch-Art-Collection-will-be-on-permanent-view-in-renovated-galleries-at-the-Nelson-Atkins#.VSayTFI5C9I.

Diane Stafford, “Bloch gift to go for Nelson upgrade,” Kansas City Star, 135, no. 203 (April 8, 2015): A1, A8.

advertisement, Town and Country (June 2015).

“Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art officially accessions Bloch Impressionist masterpieces,” Artdaily.org (July 25, 2015): https://artdaily.cc/news/80246/Nelson-Atkins-Museum-of-Art-officially-accessions-Bloch-Impressionist-masterpieces#.XjnhJyN7laQ, as Dancer Making Points.

Julie Paulais, “Le Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art reçoit des tableaux impressionnistes en échange de leurs répliques,” Le Journal des arts (July 30, 2015): https://www.lejournaldesarts.fr/patrimoine/le-nelson-atkins-museum-art-recoit-des-tableaux-impressionnistes-en-echange-de-leurs.

Nancy Staab, “Van Gogh is a Go!” 435: Kansas City’s Magazine (September 2015): 76, as Dancer Making Points.

Meryl Gordon, The Phantom of Fifth Avenue: The Mysterious Life and Scandalous Death of Heiress Huguette Clark (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2015), 238, 300–01.

“Nelson-Atkins to unveil renovated Bloch Galleries of European Art in winter 2017,” Artdaily.org (July 20, 2016): https://artdaily.cc/news/88852/Nelson-Atkins-to-unveil-renovated-Bloch-Galleries-of-European-Art-in-winter-2017-#.XjniOiN7laQ.

advertisement, Art in America’s Annual Guide 104, no. 7 (August 2016): (repro.), 127, (repro.), Dancer Making Points.

“Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art celebrates generosity of Henry Bloch with new acquisition,” Artdaily.org (October 18, 2016): https://artdaily.cc/news/90923/Nelson-Atkins-Museum-of-Art-celebrates-generosity-of-Henry-Bloch-with-new-acquisition#.XjniUiN7laQ.

“70 events in arts and culture,” Kansas City Star (December 29, 2016): http://iw.newsbank.com.proxy.mcpl.lib.mo.us/resources/doc/nb/news/16195AD6DB90E668?p=WORLDNEWS.

Catherine Futter et al., Bloch Galleries: Highlights from the Collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2016), 95, (repro.).

advertisement, KCPT Member Guide (February 2017).

advertisement, Architectural Digest (March 2017).

advertisement, CN Traveler (March 2017).

advertisement, New Yorker (March 2017).

advertisement, Vanity Fair (March 2017).

advertisement, Dos Mundos (March 3, 2017).

Albert Hect, “Henry Bloch’s Masterpieces Collection to Go on Display at Nelson-Atkins Museum,” Jewish Business News (February 26, 2017): http://jewishbusinessnews.com/2017/02/26/henry-bloch-masterpieces-collection/.

“Presenting the Bloch Galleries,” Kansas City Star 137, no. 165 (March 1, 2017): 27KC, as Dancer Making Points.

“The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: Presenting the Bloch Galleries,” New York Times (March 5, 2017).

David Frese, “Inside the Bloch Galleries: An interactive experience,” Kansas City Star 137, no. 169 (March 5, 2017): 1D, 4D, 6D, (repro.), as Dancer Making Points.

“A collection of stories: How Henry Bloch acquired the paintings in new Nelson galleries,” Kansas City Star (March 5, 2017): http://iw.newsbank.com.proxy.mcpl.lib.mo.us/ resources/doc/nb/news/162F110C47001D40?p=WORLDNEWS.

“Editorial: Thank you, Henry and Marion Bloch,” Kansas City Star (March 7, 2017): http://www.kansascity.com/opinion/editorials/ article137040948.html.

Hampton Stevens, “(Not Actually) 12 Things To Do During The Big 12 Tournament,” Flatland: KCPT’s Digital Magazine (March 9, 2017): http://www.flatlandkc.org/arts-culture/sports/not-actually-12-big-12-tournament/.

Laura Spencer, “The Nelson-Atkins’ Bloch Galleries feature Old Masterworks and New Technology,” KCUR (March 10, 2017): http://kcur.org/post/nelson-atkins-bloch-galleries-feature-old-masterworks-and-new-technology#stream/0.

Victoria Stapley-Brown, “Nelson-Atkins Museum’s new European art galleries come with a ‘love story’,” Art Newspaper (March 10, 2017): http://theartnewspaper.com/news/museums/nelson-atkins-museum-s-new-european-art-galleries-come-with-a-love-story/.

Harry Bellet, “Don du ciel pour le Musée Nelson-Atkins,” Le Monde (March 13, 2017): http://www.lemonde.fr/arts/article/2017/03/13/don-du-ciel-pour-le-musee-nelson-atkins_5093543_1655012.html.

Menachem Wecker, “Jewish Philanthropist Establishes Kansas City as Cultural Mecca,” Forward (March 14, 2017): http://forward.com/culture/365264/jewish-philanthropist-establishes-kansas-city-as-cultural-mecca/.

Juliet Helmke, “The Bloch Collection Takes Up Residence in Kansas City’s Nelson Atkins Museum,” BlouinArtInfo International, (March 15, 2017): http://www.blouinartinfo.com/news/story/2005267/the-bloch-collection-takes-up-residence-in-kansas-citys.

Erich Hatala Matthes, “Digital replicas are not soulless—they help us engage with art,” Apollo: The International Art Magazine (March 23, 2017): https://www.apollo-magazine.com/digital-replicas-3d-printing-original-artworks/.

Louise Nicholson, “How Kansas City got its magnificent museum,” Apollo (April 7, 2017): https://www.apollo-magazine.com/how-kansas-city-got-its-magnificent-museum.

Lilly Wei, “Julián Zugazagoitia: ‘Museums should generate interest and open a door that leads to further learning’,” Studio International (August 21, 2017): http://studiointernational.com/index.php/julian-zugazagoitia-director-nelson-atkins-museum-of-art-kansas-city-interview.

Robert D. Hershey Jr., “Henry Bloch, H&R Block’s cofounder, dies at 96,” Boston Globe (April 23, 2019): https://www3.bostonglobe.com/metro/obituaries/2019/04/23/henry-bloch-block-cofounder/?arc404=true.

Robert D. Hershey Jr., “Henry W. Bloch, Tax-Preparation Pioneer (and Pitchman), Is Dead at 96,” New York Times (April 23, 2019): https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/23/obituaries/henry-w-bloch-dead.html.

Claire Selvin, “Henry Wollman Bloch, Collector and Prominent Benefactor of Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Is Dead at 96,” ArtNews (April 23, 2019): http://www.artnews.com/2019/04/23/henry-bloch-dead-96/.

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “Henry Bloch, co-founder of H&R Block, dies at 96,” Kansas City Star 139, no. 219 (April 24, 2019): 1A.

“Henry Wollman Bloch (1922–2019),” Art Forum (April 24, 2019): https://www.artforum.com/news/henry-wollman-bloch-1922-2019-79547.

Frank Morris, “Henry Bloch, Co-Founder Of H&R Block, Dies At 96,” npr.org (April 24, 2019): https://www.npr.org/2019/04/24/716641448/henry-bloch-co-founder-of-h-r-block-dies-at-96.

Ignacio Villarreal, “Nelson-Atkins mourns loss of Henry Bloch,” ArtDaily.org (April 24, 2019): http://artdaily.com/news/113035/Nelson-Atkins-mourns-loss-of-Henry-Bloch#.XMB76qR7laQ.

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “H&R Block co-founder, philanthropist Bloch dies,” Cass County Democrat Missourian 140, no. 29 (April 26, 2019): 1A.

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “KC businessman and philanthropist Henry Bloch dies,” Lee’s Summit Journal 132, no. 79 (April 26, 2019): 1A.

Luke Nozicka, “Family and friends remember Henry Bloch of H&R Block,” The Kansas City Star 139, no. 225 (April 30, 2019): 4A [repr. Luke Nozicka, “Family and friends remember Henry Bloch of H&R Block,” Kansas City Star 139, no. 228 (May 3, 2019): 3A].

Eric Adler, “Sold for $3.25 million, Bloch’s home in Mission Hills may be torn down,” Kansas City Star 141, no. 90 (December 16, 2020): 2A.