Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Megan Seiler, “Gustave Caillebotte, Portrait of Richard Gallo, 1881,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.610.5407.

MLA:

Seiler, Megan. “Gustave Caillebotte, Portrait of Richard Gallo, 1881,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.610.5407.

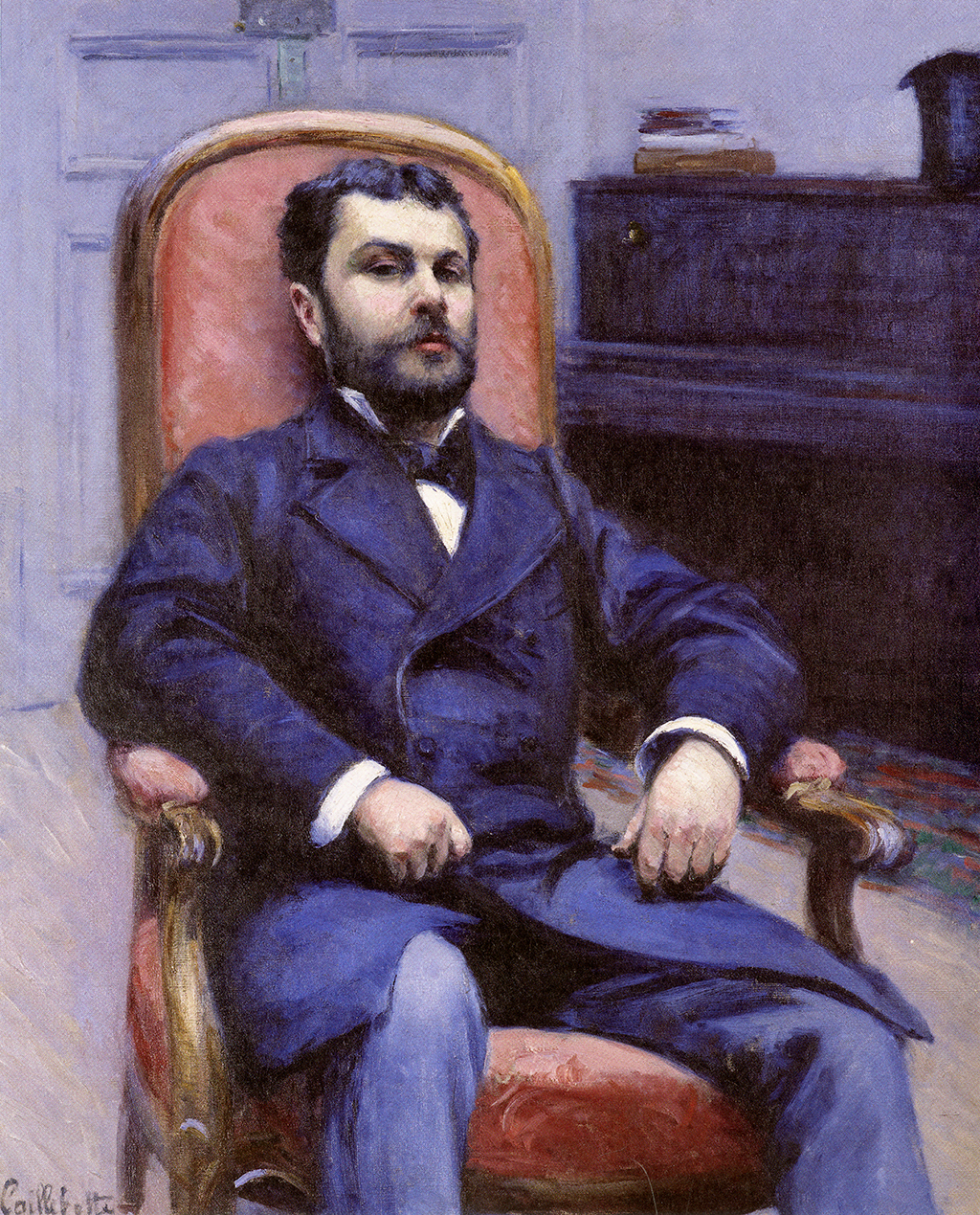

Gustave Caillebotte’s Portrait of Richard Gallo is a puzzling composition. The subject sits slightly left of center, arms crossed, on a boldly patterned sofa that appears to defy perspectival logic. The way in which Caillebotte curves the left end of the sofa—with a bold black line where the backrest and bottom cushion meet—is subtle yet unsettling. The right end of the backrest recedes in size, creating a distortion between the viewer’s world and the one Caillebotte creates. This kind of ocular manipulation appears frequently in Caillebotte’s work, but the decorative elements of this painting set it apart. The rich gold, green, and red pattern of the sofa alongside the highly pigmented pillow, created with more thickly applied paint, compete with the figure for the viewer’s attention and almost overshadow him. Caillebotte challenges traditional concepts of portraiture by utilizing such decorative elements in innovative and psychologically impactful ways. In Portrait of Richard Gallo, Caillebotte carefully selected every component of the composition, creating a complex painting that explores modern life in late nineteenth-century Paris.

Richard Gallo (1849–1936), a lifelong friend of the artist, frequently sat for Caillebotte and appeared in at least seven paintings.1Marie Berhaut, Gustave Caillebotte: Catalogue raisonne des peintures et pastels (Paris: Wildenstein, 1994), 113, 124, 127, 144, 231. Caillebotte painted him in seven paintings: Portrait of Richard Gallo (1878; private collection, Paris), Self Portrait at the Easel (1879; private collection, Paris), The Bezique Game (1880; private collection, Paris), Interior, Woman at the Window (1880; private collection, Paris), Interior: Woman Reading (1880; private collection, Paris), Portrait of Richard Gallo (1881; Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art), and Richard Gallo Walking His Dog Dick (1884; private collection, Paris). The son of a French banker, Gallo attended school with Caillebotte in Paris2Roldophe Rapetti, “Portrait of M. Richard Gallo, Also Known as Richard Gallo and His Dog Dick, at Petit Gennevilliers,” in Anne Distel et al., Gustave Caillebotte: Urban Impressionist, exh. cat. (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 1995), 280. Rapetti cites the Gallo descendants as providing this information. and later became the editor of Le Constitutionnel, a liberal Parisian newspaper.3Berhaut, Gustave Caillebotte, 144. Caillebotte cleverly alludes to Gallo’s profession by including the rival conservative newspaper Le Figaro, seen resting across his lap. In this tightly cropped view of the room, the audacious patterning of the sofa demands the viewer’s attention and occupies a majority of the canvas. Gallo is engulfed in the sea of color and, with his rigid posture and folded arms, appears uncomfortable. The red and green stripes, overlaid with a gold arabesque pattern, are in stark contrast to the room’s muted color and minimal décor. In choosing a piece of furniture as the focal point of the portrait, Caillebotte explores new ideas around the role of interior design and the psychology of space.

Contemporary art critic and novelist Edmund Duranty argued in his essay “La Nouvelle Peinture,” published in 1876, that the interior space of a portrait should reflect a sitter’s identity:

What we need are the special characteristics of the modern individual—in his clothing, in social situations, at home. . . . Surrounding him and behind him are the furniture, fireplaces, curtains, and walls that indicate his financial position, class, and profession.4Edmond Duranty, La Nouvelle Peinture: Á propos du Groupe d’Artistes qui expose dans les Galeries Durand-Ruel (Paris: E. Dentu, 1876), 24, 27–28; English translation from “The New Painting,” in The New Painting: Impressionism 1874–1886, ed. Charles S. Moffett, exh. cat. (San Francisco: Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, 1986), 43–44. For more on Duranty and his ideas of the interior as a reflection of the man, see Pamela J. Warner, Interior Portraiture and Masculine Identity in France, 1789–1914 (Surrey: Ashgate, 2011), esp. 160.

In Portrait of Richard Gallo, however, few trappings of bourgeoishaute bourgeoisie: French for ”the upper middle class“ life are visible. Instead, Caillebotte uses minimal5I use this term to refer to how many items are in the painting; it is not to be confused with the design style of “minimalism,” which was not developed until post-World War II. decorative elements for maximum impact, and each element deserves close examination.

First there is the sofa on which Gallo sits. Caillebotte often featured the same pieces of furniture in his paintings, most frequently a taupe divan embossed with small florals and narrow stripes.6Although the Oxford English Dictionary defines sofa as “a long, stuffed seat with a back and ends or end,” and divan as “a low bed or couch with no back or ends,” period descriptions classify a divan as a type of sofa, and I am using the terms interchangeably here. Berhaut, Gustave Caillebotte, 124, 127, 144, 150. The paintings Nude on a Couch, Bezique Game, Self-Portrait, and Woman Reading include this divan. In Nude on a Couch (Fig. 1), Caillebotte provides a nearly full view of the divan and its versatility, as the woman in the painting uses a large support pillow under her head, while the other two cushions lean against the wall. In nineteenth-century France, furniture became mass-produced and lower in cost, and items became lighter and more mobile within the home.7Elizabeth Benjamin, “The Unhomely Home: Caillebotte’s Interior Paris” (PhD diss., Northwestern University, 2016), 106–7. With its bed-like base and loose back pillows, Caillebotte’s divan could easily be shifted around a room, creating specific vignettes for the artist.

A deliberate choice by Caillebotte either way, the green and gold material alongside the pillow adds to the visual noise and unsettling composition for the viewer. A photograph from inside the home of Caillebotte’s brother Martial, once the shared home of the two brothers (Fig. 2), features curtains whose patterns and stripes bear a resemblance to the divan in Portrait of Richard Gallo.9Although this photograph dates from 1895–96, after Gustave Caillebotte’s death, it documents the shared apartment they moved into in 1878–1879. Unfortunately, Caillebotte’s brother and the piano obstruct the view of the bottom of the curtain. It is therefore impossible to know if the curtains themselves had fringe, which would align with the style of the time, or if Caillebotte might have added a painted fringe as a visual element to guide the linear perspective and ground the sofa within the composition.

While women’s fashion in the 1880s saw the introduction of a wide range of clothing styles and colors, promoted by haute couture houses and fashion publications, the bourgeois male subscribed to uniformity and muted tones in the form of a suit.10Debra Mancoff, Fashion in Impressionist Paris (London: Merrell, 2012), 50. The style of suit and coat appear repeatedly in Caillebotte’s paintings. The suit’s rise in popularity began after the Industrial Revolution, when the processes of making both fabric and clothing became mechanized, democratizing fashion and making it accessible to people of varied economic classes.11Michael Zakim, “Customizing the Industrial Revolution: The Reinvention of Tailoring in the Nineteenth Century,” Winterthur Portfolio 33, no. 1 (Spring 1998): 42. The suit’s muted color palette appealed to the Parisian flâneurflâneur: French for “stroller”, “lounger”, “saunterer”, or “loafer.” A term popularized by writer Charles Baudelaire to describe a kind of urban male observer. because its uniformity offered anonymity, and its universality rejected aristocratic aesthetics. For politically progressive individuals such as Gallo and Caillebotte, visually aligning with the middle and working classes by wearing a suit became a mechanism for renouncing the old, aristocratic culture of France. Consider here another portrait of Richard Gallo (Fig. 4) from 1878, in which he sports similar bourgeois attire. The long black overcoat and gray pants, with his top hat resting atop the piano by the door, are the signature outerwear of the flâneur. Again, Caillebotte creates tension between Gallo and his interior with his uncomfortable pose and overpowering red Voltaire chairVoltaire chair: An armchair with a low seat and high back.. Instead of filling the room with objects to explore the sitter’s identity, Caillebotte engages key furnishings that create a discussion around contemporary life and interior spaces.

The trappings of bourgeois comfort, albeit minimal, are disquieting in juxtaposition with the restrained sitter. Gallo’s folded arms, rigid posture, distant gaze, and slanted pose demonstrate Gallo’s discomfort but also transfer that discomfort to the viewer, who oscillates between being drawn into the space and rejected by it.14Hollis Clayson makes a similar statement about two of Caillebotte’s other images in her essay, “Threshold Space: Parisian Modernism Betwixt and Between (1869 to 1891),” in Janet McLean, ed., Impressionist Interiors (Dublin: Colorman, 2009), 20–22. The viewer feels forced into the space, and yet Gallo’s position leaves little room for receiving a second individual. His gaze, just to the right of the viewer, provides no hint of personal acknowledgment. With these elements, Caillebotte creates a peek into the anxieties of everyday interior life, a defining feature of a genre scene.

Although Portrait of Richard Gallo does not mirror Duranty’s directive to populate interiors with an array of decorative items that remind one of the sitter’s station, Caillebotte’s own sense of interior decorating did. Photographs show that he filled his home with artwork and other possessions that reflected his interests. One scholar suggests that Portrait of Richard Gallo, with its minimal décor, is an example of Caillebotte “thumbing his nose” at the decorative trends of the time, but this theory neglects Caillebotte’s own maximalist decorative taste and, in a way, dismisses the artist’s clever and deliberate use of the ornamental in his œuvre.15Elizabeth Benjamin, “The Modern Interior Stripped Bare: Gustave Caillebotte’s Interieur Demeuble,” in Anca I. Lasc, ed., Visualizing the Nineteenth-Century Home: Modern Art and the Decorative Impulse (London: Routledge, 2016), 131. Rather than seeing Caillebotte’s sparse room as a commentary on decorating taste, it seems more prudent to interpret what was included and how those elements impact the viewer.

Caillebotte debuted Portrait of Richard Gallo at the seventh Impressionist Exhibition in 188216Catalogue de la 7me Exposition des Artistes Indépendants, exh. cat. (Paris: Morris père et fils, 1882), unpaginated [repr. in, Theodore Reff, ed., Modern Art in Paris: Two-Hundred Catalogues of the Major Exhibitions Reproduced in Facsimile in Forty-Seven Volumes, vol. 23, Impressionist Group Exhibitions (New York: Garland, 1981), unpaginated], as Portrait de M. G. and later gave the painting to Gallo.17Berhaut, Gustave Caillebotte, 144. In 1907, Gallo moved to Alexandria, Egypt, and gave the painting to his niece, Marthe Rolland.18Berhaut (Gustave Caillebotte, 138) names a Maurice Rolland as the original inheritor of the painting, but my research shows a marriage certificate between Paul Antione Marius Rolland and Marthe Grandguillot on August 8, 1898, and a death announcement on August 11, 1965, for Marthe Grandguillot, where Maurice Rolland is listed first, indicating that Maurice Rolland was her son. See NAMA curatorial files provenance records for both the marriage certificate and death announcement. It remained in the Rolland family until 1988, when they sold it to Paul and Ellen Josefowitz.19Henri Malcor, “Richard Gallo,” unpublished manuscript, May 20, 1988, copy in the NAMA curatorial files. In the fall of 1989, Roger Ward, then the curator of European art at the Nelson-Atkins, proposed the acquisition, citing the artist’s rarity in most museum collections of the day.20See Acquisition Proposal, December 15, 1989, and Board Meeting Minutes, Fall 1989, the NAMA curatorial files. Ward noted that while other museums had great examples by Caillebotte, none were portraits, noting, “The picture under consideration would . . . be unique in the United States.”21See Acquisition Proposal, December 15, 1989, and Board Meeting Minutes, Fall 1989, the NAMA curatorial files, under “Works in Other U.S. Collections.” Ward’s foresight in acquiring Caillebotte’s portrait provided the Nelson-Atkins with an important piece of the artist’s legacy that complicates the discussion around the interior spaces of nineteenth-century Paris.

Notes

-

Marie Berhaut, Gustave Caillebotte: Catalogue raisonné des peintures et pastels (Paris: Wildenstein, 1994), 113, 124, 127, 144, 231. Caillebotte painted him in seven paintings: Portrait of Richard Gallo (1878; private collection, Paris), Self Portrait at the Easel (1879; private collection, Paris), The Bezique Game (1880; private collection, Paris), Interior, Woman at the Window (1880; private collection, Paris), Interior: Woman Reading (1880; private collection, Paris), Portrait of Richard Gallo (1881; Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art), and Richard Gallo Walking His Dog Dick (1884; private collection, Paris).

-

Roldophe Rapetti, “Portrait of M. Richard Gallo, Also Known as Richard Gallo and His Dog Dick, at Petit Gennevilliers,” in Anne Distel et al., Gustave Caillebotte: Urban Impressionist, exh. cat. (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 1995), 280. Rapetti cites the Gallo descendants as providing this information.

-

Berhaut, Gustave Caillebotte, 144.

-

Edmond Duranty, La Nouvelle Peinture: Á propos du Groupe d’Artistes qui expose dans les Galeries Durand-Ruel (Paris: E. Dentu, 1876), 24, 27–28; English translation from “The New Painting,” in The New Painting: Impressionism 1874–1886, ed. Charles S. Moffett, exh. cat. (San Francisco: Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, 1986), 43–44. For more on Duranty and his ideas of the interior as a reflection of the man, see Pamela J. Warner, Interior Portraiture and Masculine Identity in France, 1789–1914 (Surrey: Ashgate, 2011), esp. 160.

-

I use this term to refer to how many items are in the painting; it is not to be confused with the design style of “minimalism,” which was not developed until post-World War II.

-

Although the Oxford English Dictionary defines sofa as “a long, stuffed seat with a back and ends or end,” and divan as “a low bed or couch with no back or ends,” period descriptions classify a divan as a type of sofa, and I am using the terms interchangeably here. Berhaut, Gustave Caillebotte, 124, 127, 144, 150. The paintings Nude on a Couch, Bezique Game, Self-Portrait, and Woman Reading include this divan.

-

Elizabeth Benjamin, “The Unhomely Home: Caillebotte’s Interior Paris” (PhD diss., Northwestern University, 2016), 106–7.

-

Elizabeth Benjamin, “All the Discomforts of Home,” in Gustave Caillebotte: The Painter’s Eye, exh. cat. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015), 94, 261n41.

-

Although this photograph dates from 1895–96, after Gustave Caillebotte’s death, it documents the shared apartment they moved into in 1878–1879.

-

Debra Mancoff, Fashion in Impressionist Paris (London: Merrell, 2012), 50. The style of suit and coat appear repeatedly in Caillebotte’s paintings.

-

Michael Zakim, “Customizing the Industrial Revolution: The Reinvention of Tailoring in the Nineteenth Century,” Winterthur Portfolio 33, no. 1 (Spring 1998): 42.

-

D. G. Karraker, Looking at European Frames: A Guide to Terms, Styles, and Techniques (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2014), 5–6. Edgar Degas (1834–1917) also created his own frames; for example, see Degas’s Junior Milliners, Fig. 10, in this catalogue.

-

See conservation record of treatment by Kate Garland, June 7, 2016, NAMA curatorial files.

-

Hollis Clayson makes a similar statement about two of Caillebotte’s other images in her essay, “Threshold Space: Parisian Modernism Betwixt and Between (1869 to 1891),” in Janet McLean, ed., Impressionist Interiors (Dublin: Colorman, 2009), 20–22.

-

Elizabeth Benjamin, “The Modern Interior Stripped Bare: Gustave Caillebotte’s Interieur Demeuble,” in Anca I. Lasc, ed., Visualizing the Nineteenth-Century Home: Modern Art and the Decorative Impulse (London: Routledge, 2016), 131.

-

Catalogue de la 7me Exposition des Artistes Indépendants, exh. cat. (Paris: Morris père et fils, 1882), unpaginated [repr. in, Theodore Reff, ed., Modern Art in Paris: Two-Hundred Catalogues of the Major Exhibitions Reproduced in Facsimile in Forty-Seven Volumes, vol. 23, Impressionist Group Exhibitions (New York: Garland, 1981), unpaginated], as Portrait de M. G.

-

Berhaut, Gustave Caillebotte, 144.

-

Berhaut (Gustave Caillebotte, 138) names a Maurice Rolland as the original inheritor of the painting, but my research shows a marriage certificate between Paul Antione Marius Rolland and Marthe Grandguillot on August 8, 1898, and a death announcement on August 11, 1965, for Marthe Grandguillot, where Maurice Rolland is listed first, indicating that Maurice Rolland was her son. See NAMA curatorial files provenance records for both the marriage certificate and death announcement.

-

Henri Malcor, “Richard Gallo,” unpublished manuscript, May 20, 1988, copy in the NAMA curatorial files.

-

See Acquisition Proposal, December 15, 1989, and Board Meeting Minutes, Fall 1989, the NAMA curatorial files.

-

See Acquisition Proposal, December 15, 1989, and Board Meeting Minutes, Fall 1989, the NAMA curatorial files, under “Works in Other U.S. Collections.”

Technical Entry

Technical entry forthcoming.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Megan Seiler, “Gustave Caillebotte, Portrait of Richard Gallo, 1881,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.610.4403.

MLA:

Seiler, Megan. “Gustave Caillebotte, Portrait of Richard Gallo, 1881,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.610.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Megan Seiler, “Gustave Caillebotte, Portrait of Richard Gallo, 1881,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.610.4403.

MLA:

Seiler, Megan. “Gustave Caillebotte, Portrait of Richard Gallo, 1881,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.610.4033.

Given by the artist to the sitter, Richard Gallo (1849‒1936), Paris, probably 1881‒1907 [1];

His gift to his niece, Marthe Rolland (née Grandguillot, 1877‒1965), Paris, 1907‒1965 [2];

By descent to her son, Maurice Rolland (1904‒1988), Paris, 1965‒1988;

By inheritance to his sister, Jeanne Janette Malcor (née Rolland, 1901‒1995), Paris, 1988 [3];

Purchased from Malcor by Paul (1950‒2013) and Ellen Melas Kyriazi Josefowitz, London and Lausanne, August 25‒November 26, 1988 [4];

Purchased from Paul and Ellen Josefowitz by the dealer David Ramus, Atlanta and New York, on joint account with Hirschl and Adler, New York, stock no. 6852/2, November 26, 1988‒1989 [5];

Purchased from David Ramus and Hirschl and Adler by The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1989.

Notes

[1] In a statement on the painting’s history, dated May 20, 1988, Richard Gallo’s grand-nephew-in-law, Henri Malcor, wrote that Gallo collected a number of paintings from Impressionist artists, to whom he was introduced by his friend Gustave Caillebotte. Ultimately, Gallo only kept the five paintings Caillebotte gave to him, three of which represented Gallo. See “Richard Gallo” by Henri Malcor, May 20, 1988, copy in NAMA curatorial files.

[2] The Caillebotte catalogue raisonné indicates that the painting passed to Gallo’s nephew, Maurice Rolland, at the time of Gallo’s death in 1936. However, Maurice Rolland was actually Gallo’s grand-nephew, and according to Henri Malcor’s statement on Richard Gallo (see note 1), Gallo gave the painting to his niece Marthe in 1907, when Gallo moved to Alexandria, Egypt. The painting then passed to Marthe’s son Maurice Rolland. See Marie Berhaut, Gustave Caillebotte: catalogue raisonné des peintures et pastels (Paris: Wildenstein Institute, 1994), no. 182, p. 144, and “Richard Gallo” by Henri Malcor, May 20, 1988, copy in NAMA curatorial files.

[3] Carole Bonzon-Vachette, Jeanne Malcor’s great-granddaughter, confirmed the family’s sale of the painting following Maurice Rolland’s death in correspondence with Megan Seiler, NAMA, May 27, 2020, NAMA curatorial files.

[4] According to Ellen Josefowitz, in an email to MacKenzie Mallon, NAMA, June 8, 2020, NAMA curatorial files.

[5] See email from Gregory Hedberg, Hirschl and Adler, New York, to Nicole Myers, NAMA, May 11, 2015, and email from Ellen Josefowitz to MacKenzie Mallon, NAMA, June 8, 2020, NAMA curatorial files.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Megan Seiler, “Gustave Caillebotte, Portrait of Richard Gallo, 1881,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.610.4403.

MLA:

Seiler, Megan. “Gustave Caillebotte, Portrait of Richard Gallo, 1881,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.610.4033.

Gustave Caillebotte, Portrait of Richard Gallo, 1878, oil on canvas, 31 1/2 x 25 3/5 in. (80 x 65 cm), private collection, France.

Gustave Caillebotte, Self Portrait in Front of the Easel, 1879, oil on canvas, 35 3/7 x 45 2/7in. (90 x 115 cm), private collection, Paris.

Gustave Caillebotte, Game of Bezique, 1880, oil on canvas, 47 5/8 x 63 2/5 in. (121 x 161 cm), private collection, Paris.

Gustave Caillebotte, Interior, Reading Woman, 1880, oil on canvas, 25 3/5 x 31 1/2 in. (65 x 80 cm), private collection, Paris.

Gustave Caillebotte, Interior, Woman at the Window, 1880, oil on canvas, 45 2/3 x 35 in. (116 x 89 cm), private collection, Paris.

Gustave Caillebotte, Richard Gallo and his Dog at Petit Gennevilliers, 1884, oil on canvas, 35 x 45 2/3 in. (89 x 116 cm), private collection, Paris.

Gustave Caillebotte, Paul the Dog, ca. 1886, oil on canvas, 25 3/4 x 21 3/4 in. (65.4 x 54.2 cm), sold at Masterpieces from the Collection of Sam Josefowitz: A Lifetime of Discovery and Scholarship, Christie’s, London, lot 3, as Le chien “Paul”.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Megan Seiler, “Gustave Caillebotte, Portrait of Richard Gallo, 1881,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.610.4403.

MLA:

Seiler, Megan. “Gustave Caillebotte, Portrait of Richard Gallo, 1881,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.610.4033.

7me Exposition des Artistes Indépendants [7th Impressionist Exhibition], 251 rue Saint-Honoré, Paris, March 1‒31, 1882, no. 5, as Portrait de M. G.

Exposition Rétrospective d’Œuvres de G. Caillebotte, Galerie Durand-Ruel, Paris, June 4‒16, 1894, no. 81, as Portrait de M. R. G.

Gustave Caillebotte: The Unknown Impressionist, Royal Academy of Arts, London, March 28‒June 23, 1996, no. 26, as Portrait of Richard Gallo.

Gustave Caillebotte: The Painter’s Eye, The National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, June 28‒October 4, 2015; Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, TX, November 8, 2015‒February 14, 2016, no. 25, as Portrait of Richard Gallo.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Megan Seiler, “Gustave Caillebotte, Portrait of Richard Gallo, 1881,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.610.4403.

MLA:

Seiler, Megan. “Gustave Caillebotte, Portrait of Richard Gallo, 1881,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.610.4033.

Catalogue de la 7me Exposition des Artistes Indépendants, exh. cat. (Paris: Morris père et fils, 1882), unpaginated [repr. in, Theodore Reff, ed., Modern Art in Paris: Two-Hundred Catalogues of the Major Exhibitions Reproduced in Facsimile in Forty-Seven Volumes, vol. 23, Impressionist Group Exhibitions (New York: Garland, 1981), unpaginated], as Portrait de M. G.

Gaston d’Alq., “Art et bibelots: L’Exposition des Peintres indépendants,” La Liberté (March 2, 1882): 3.

Possibly Fichtre, “L’Actualité: L’Exposition des peintres indépendants,” Le Réveil (March 2, 1882): 1.

Possibly La Fare, “Exposition des Impressionnistes,” Le Gaulois 15, no. 901 (March 2, 1882): 2.

“Les Peintres indépendants,” L’Intransigeant (March 2, 1882): 3.

Jacques Durand, “Échos du jour: Paris,” La Presse 47, no. 61 (March 3, 1882): 1.

Charles Flor, “Deux Expositions,” Le National 14, no. 4735 (March 3, 1882): 2.

Possibly A. Hustin, “L’Exposition des Peintres Indépendants,” L’Estafette (March 3, 1882): 3.

Possibly A. Hustin, “L’Exposition des impressionnistes,” Moniteur des Arts 25, no. 1402 (March 10, 1882): 1.

Henri Rivière, “Aux indépendants,” Le chat noir (April 8, 1882): 4.

Exposition Rétrospective d’Œuvres de G. Caillebotte, exh. cat. (Paris: Galeries Durand-Ruel, 1894), 6, as Portrait de M. R. G.

Marie Berhaut, Gustave Caillebotte, 1848‒1894: Catalogue des peintures et pastels (Paris: Wildenstein, 1951), no. 127, unpaginated, as Portrait de M. G. . . .

Marie Berhaut, Caillebotte, Sa Vie et Son Œuvre: Catalogue Raisonné des Peintures et Pastels (Paris: Fondation Wildenstein, 1978), no. 167, pp. 110, 125, 138, 179, 249, (repro.), as Portrait de Richard Gallo.

Charles S. Moffett, ed., The New Painting, Impressionism, 1874–1886, exh. cat. (Geneva, Switzerland: Richard Burton SA, Publishers, 1986), 379, 394, as Portrait de M. G.

Kirk Varnedoe, Gustave Caillebotte (1987; repr., New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000), 196.

Victor Volland, “Traveling Impressionist Exhibit,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch (May 21, 1989): 2D.

Janet Majure, “How Art Galleries Stay Competitive: Museums’ Practice of Buying, Selling Under Intense Scrutiny in Today’s Market,” Kansas City Star 110, no. 240 (June 10, 1990): I10.

Laura Caruso, “Caillebotte Joins Ranks at Nelson: Museum Pays its Highest Price Ever for Portrait by Impressionist,” Kansas City Star 111, no. 6 (September 23, 1990): J[1], J4, (repro.), as Portrait of M. Richard Gallo.

“New at the Nelson: Impressionist Masterpiece,” Newsletter (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (October 1990): 2‒3, (repro.), as Portrait of Richard Gallo.

Roger Ward, “Selected Acquisitions of European and American Paintings at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, 1986‒1990,” Burlington Magazine, 133, no. 1055 (February 1991): 153, 156, (repro.).

Alice Thorson, “The Nelson Celebrates its 60th: Museum built its reputation, collection virtually ‘from scratch’,” Kansas City Star 113, no. 304 (July 18, 1993): J5.

Roger Ward and Patricia Fidler, eds., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: Handbook of the Collection (New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1993), 45, 130, 210, (repro.), as Portrait of Richard Gallo.

Marie Berhaut, Gustave Caillebotte: catalogue raisonné des peintures et pastels (Paris: Wildenstein Institute, 1994), no. 182, p. 144, (repro.) as Portrait de Richard Gallo.

Gustave Caillebotte: 1848‒1894, exh. cat. (Paris: Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 1994), 220‒21, 237, 240, 242, 292, 358, 373, 375, (repro.), as Portrait de Richard Gallo [repr., Gustave Caillebotte: The Unknown Impressionist, exh. cat. (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 1996), 105‒06, 123, 128‒29, 137, 212, (repro.), as Portrait of Richard Gallo].

Ruth Berson, The New Painting: Impressionism 1874–1886; Documentation (San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1996), no. VII-5, pp. 1:377, 379, 386‒87, 389, 395, 398, 401, 409; 2:201, 215, (repro.), as Portrait de M. G.

Gustave Caillebotte, 1848–1894: Dessins, Pastels et Peintures, exh. cat. (Paris: Brame et Lorenceau, 1998), 19, as Portrait de M. G.

Patrick Shaw Cable, “Questions of Work, Class, Gender, and Style in the Art and Life of Gustave Caillebotte” (Ph.D. diss., Case Western Reserve University, 2000), vii, 48, 179‒80, 180n312, 259, (repro.), as Portrait of M. G.

Impressionist and Modern Art Evening Sale (London: Christie’s, February 6, 2001), 34, as Portrait de Richard Gallo.

Alice Thorson, “Nelson curator of European art heading to Florida,” Kansas City Star (August 19, 2001): I4.

Impressionist and Modern Art Day Sale (London: Christie’s, February 5, 2002), 34.

Caillebotte: Au cœur de l’impressionnisme, exh. cat. (Lausanne: Bibliothèque des Arts, 2005), 177, as Portrait de M. G.

Alice Thorson, “Nelson Makeover: Euro Edition,” Kansas City Star 126, no. 281 (June 25, 2006): G7, as Portrait of Richard Gallo.

Anne-Birgitte Fonsmark, Dorothee Hansen, and Gry Hedin, Gustave Caillebotte, exh. cat. (Ostfildern, Germany: Hatje Cantz, 2008), 87n6.

Deborah Emont Scott, ed., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collection, 7th ed. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2008), 35, 122, (repro.), as Portrait of Richard Gallo.

Karin Sagner, Gustave Caillebotte: Neue Perspektiven des Impressionismus (Munich: Hirmer Verlag, 2009), 10, 73, 102, 142, 176, (repro.), as Porträt Richard Gallo.

Shimbata Yasuhide, Gustave Caillebotte: Impressionist in Modern Paris, exh. cat. (Tokyo: Bridgestone Museum of Art, 2013), 76, 258.

Mary Morton and George T. M. Shackelford, Gustave Caillebotte: The Painter’s Eye, exh. cat. (Washington: National Gallery of Art, 2015), 16, 36, 40‒41, 53, 154, 164‒65, 174‒75, 277, (repro.), as Portrait of Richard Gallo.

Sylvain Amic and Diederik Bakhuÿs, Scènes de la vie impressionniste: Manet, Renoir, Monet, Morisot, exh. cat. (Rouen: Musée des Beaux-Arts, 2016), 76, 93, as Portrait de Richard Gallo.

Catherine Futter et al., Bloch Galleries: Highlights from the Collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2016), 65, (repro.).

Michael Marrinan, Gustave Caillebotte: Painting the Paris of Naturalism, 1872‒1887 (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2016), 265, 266, 281n55, (repro.), as Portrait of Richard Gallo.

Lexie Sharabianlou, “Why audio tours still work: storytelling that immerses, excites, and inspires listeners,” Blooloop.com (August 13, 2019): http://blooloop.com/guru-audio-tours-still-work/., (repro.), as Portrait of Richard Gallo.

Impressionist and Modern Art Evening Sale (New York: Sotheby’s, November 12, 2019), (repro.) as Portrait of Richard Gallo.