![]()

Vincent van Gogh, Head of a Man, mid- to late March 1885

| Artist | Vincent van Gogh, Dutch, 1853–1890 |

| Title | Head of a Man |

| Object Date | mid- to late March 1885 |

| Alternate and Variant Titles | Portrait of Gijsbertus de Groot; Study of a Peasant’s Head |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (Unframed) | 16 9/16 x 12 9/16 in. (42.1 x 31.9 cm) |

| Credit Line | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 37-1 |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “Vincent van Gogh, Head of a Man, 1885,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.735.5407.

MLA:

Marcereau DeGalan, Aimee. “Vincent van Gogh, Head of a Man, 1885,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.735.5407.

In the fall of 1883, after living for two years in the relatively

cosmopolitan Dutch city of The Hague,1Van Gogh spent two periods living in The Hague, from July 30, 1869, until May 10, 1873, and from November 27, 1881, to September 11, 1883. In between these sojourns, he spent time in France, England, Belgium, and elsewhere in the Netherlands. Vincent van Gogh wanted

“nothing other than to live deep in the country and to paint peasant

life.”2Vincent van Gogh, Neunen, to Theo van Gogh, Monday, April 6, 1885, published in Leo Jansen, Hans Luijten, and Nienke Bakker, eds., Vincent Van Gogh: The Letters, online edition (Amsterdam and The Hague: Van Gogh Museum and Huygens, 2009), no. 490, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let490/letter.html. All English translations of Van Gogh’s letters are from this publication On December 5, 1883, he boarded a train to the rural town of

Nuenen in the east of the North Brabant province of the Netherlands,3Van Gogh left The Hague on September 11, 1883, and spent nearly three months in Drenthe, a province in the northeastern part of the Netherlands, before taking a train to Nuenen, where his parents lived. For more on this moment in Van Gogh’s career, see J. Dijk Wout and Meent W. van der Sluis, De Drentse Tijd Van Vincent Van Gogh: Een Onderbelichte Periode Nader Onderzocht, 1883 (Groningen: Boon Uitg, 2001).

and over the next two years he embarked on a significant artistic

journey to create a series of studies of peasants’ heads. These studies,

of which the Nelson-Atkins painting is one example, had a pivotal role in shaping

his artistic development. They ultimately culminated in his most

substantial figural composition, The Potato Eaters, a dimly lit

interior scene of five rural farmworkers enjoying a modest meal by

lamplight (Fig. 1).

Peasant themes in general, and shared meals in particular, were popular

subjects among many of Van Gogh’s near contemporaries, including French

Barbizon painters like Jean-François Millet (1814–1875); their Dutch

counterparts in the Hague School, such as Jozef Israëls (1824–1911);4Many scholars have made this observation, including Bregje Gerritse in The Potato Eaters: Van Gogh’s First Masterpiece, exh. cat. (Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum, 2022), 31–32. Van Gogh mentions a painting by Israëls, presumed to be Peasant Family at the Table (1882; Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam), in a letter to Theo, Saturday, March 11, 1882, in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 211, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let211/letter.html.

and nineteenth-century English and Continental wood engravers like

Hubert von Herkomer (Dutch, 1849–1914), among others.5For additional insight on this topic, see Martin Bailey and Debora Silverman, Van Gogh in England: Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (London: Barbican Art Gallery, 1992), cited in George Keyes, “The Dutch Roots of Vincent van Gogh,” in Roland Dorn et al., Van Gogh Face to Face: The Portraits, exh. cat. (Detroit: Detroit Institute of Arts, 2000), 24n17. For a more recent publication about Van Gogh’s nineteenth-century sources, see Eik Kahng, Through Vincent’s Eyes: Van Gogh and His Sources (Santa Barbara, CA: Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 2021). The theme,

which also had religious undertones, resonated deeply with Van Gogh. In

particular, he drew inspiration from Rembrandt van Rijn’s (Dutch,

1606–1669) Supper at Emmaus, which Van Gogh encountered in Paris at

the Louvre in 1875 (Fig. 2).6See Vincent van Gogh, Paris, to Theo van Gogh, May 31, 1875, in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 34, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let034/letter.html. The painting depicts the moment in Luke

24:13–35 when the resurrected Christ reveals his identity through

breaking bread and offering a blessing to two disciples he encounters on

a journey. Van Gogh’s fascination with this work underscores the

artist’s exploration of the spiritual in the everyday.7The idea of finding the spiritual in the everyday, particularly among the working classes, aligned with the practice of Van Gogh’s father during his ministry of the Dutch Reformed Church in the rural farming community of Zundert in the southern Netherlands region of Brabant. For more on the region and this branch of religion, see Deborah Silverman, Van Gogh and Gauguin: The Search for Sacred Art (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2000), 143–51. Van Gogh makes the subjects of the Potato Eaters Catholic, however, through his inclusion of the devotional print of the Crucifixion with the Virgin Mary and St. John; see Louis van Tilborgh and Marije Vellekoop, Vincent Van Gogh: Paintings, vol. 1, Dutch Period, 1881–1885, Van Gogh Museum (London: Lund Humphries, 1999), 138–39. Following the

scriptural account, Van Gogh saw something holy in the simple act of

sharing a humble meal.

Van Gogh explored peasant life in a series of works he titled “Heads of the People,” building on a project he initiated in The Hague.8During Van Gogh’s second sojourn in The Hague, he embarked on his “Series of the People” drawn from life. His aim was to create lithographs that could be commercially available at a small cost. Van Gogh conceived of another series, entitled “Heads of the People,” inspired by images of laborers in Hubert von Herkomer’s series of the same title, featured in The Graphic from 1875 to 1885. See Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, Saturday, June 3, 1882, in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 235, n37, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let235/letter.html. He began the series in Nuenen at the end of October 1884 and completed thirty studies by the end of February.9See Vincent van Gogh, Neunen, to Theo van Gogh, between about February 5 and 26, 1885, in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 483, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let483/letter.html. Also cited in Tilborgh and Vellekoop, Vincent Van Gogh: Paintings, 1:84n2–4. A few months later, he expanded his vision to encompass fifty works.10See Vincent van Gogh, Neunen, to Theo van Gogh, November 2, 1884, no. 468, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let468/letter.html; November 17, 1884, no. 470, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let470/letter.html; and on or about December 14, 1884, no. 475, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let475/letter.html, all in Jansen et al., Letters (also cited in Tilborgh and Vellekoop, Vincent Van Gogh: Paintings, 1:84n3). A total of forty-seven paintings from this series have survived, with the last known work created in May 1885.11Tilborgh and Vellekoop state that the last time Van Gogh discussed the heads was in June 1885. See Vincent van Gogh, Neunen, to Theo van Gogh, on or about June 2, 1885, in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 506, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let506/letter.html, cited in Tilborgh and Vellekoop, Vincent Van Gogh: Paintings, 1:84n2–4. Throughout this period, Van Gogh actively experimented with contrasting and complementary color combinations, explorations of tone, representations of light sources, and themes honoring rural life. Van Gogh’s interest in this subject matter was also informed by his deep respect for the workers themselves. He connected their humility, dignity, and the grace of a shared meal—procured through the arduous labor of their own hands—to a profound sense of spirituality.12Van Gogh’s reading of John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress (1678) in or around 1876 reinforced this belief. See Vincent van Gogh, Isleworth, to Theo van Gogh, November 3, 1876, no. 96, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let096/letter.html, and Vincent van Gogh, Isleworth, to Theo van Gogh, November 25, 1876, no. 99, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let099/letter.html, both in Jansen et al., Letters. Bunyan argued that God’s grace favored those who were modest, selfless, and detached from worldly wealth, qualities that Van Gogh associated with workers and the poor. See also Deborah Silverman, “Pilgrim’s Progress and Vincent van Gogh’s Metier,” in Bailey and Silverman, Van Gogh in England, 100.

Van Gogh was the son of a Dutch Reformed minister, and his spiritual foundation was deep-rooted. His journey began with theological studies in 1877 and evolved through his role as an evangelical lay preacher among coal miners in the Borinage region of Belgium in 1879.13Van Gogh had been practicing as a minister to the coal mining families in the Borinage for approximately six months, and the local evangelical committee decided he was not well suited to the profession. See Vincent van Gogh, Brussels, to Theo van Gogh, Tuesday, August 5, 1879, in Jansen et al., Letters, no.153, n8, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let153/letter.html# Although he was dismissed from this position, his connection to Biblical study and tenets of Christianity endured, channeled through his new vocation as an artist. On this new path, Van Gogh sought to reconcile his faith with the modern world, finding the divine in everyday life. He viewed laborers as genuine servants of God, believing that their earthly contributions and inherent worth transcended those of someone like himself: a self-taught artist who wrestled with both internal and external pressures for validation.14Deborah Silverman makes this point in Van Gogh and Gauguin, 109. While his perception of these people was undeniably idealized and influenced by his own relative class privilege, there is no question that he held genuine sympathy for the impoverished.15Nienke Bakker makes this point in “On Rustics and Labourers: Van Gogh and ‘the People,’” in Chris Stolwijk and Nienke Bakker, Van Gogh’s Imaginary Museum: Exploring the Artist’s Inner World (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2003), 87. It was through this self-scrutinizing lens that Van Gogh undertook his study of heads, including the Nelson-Atkins composition.

Van Gogh approached his studies of peasants’ heads not as individual portraits but as embodiments of authentic types. His intent was to encapsulate the very essence of rural life, selecting subjects with rough, weathered faces and elevating those with unconventional appearances.16Van Gogh’s concept of specific character types draws from the pseudoscience of physiognomy, which attributed a person’s personality and character to their physical appearance. He was familiar with Johann Caspar Lavater and Franz Joseph Gall’s book Physiognomie et phrénologie rendues intelligibles pour tout le monde (1862), which he read in 1880. See Vincent van Gogh, Brussels, to Theo van Gogh, Monday, November 1, 1880, in Jansen et al., Letters, no.160, n8, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let160/letter.html. Writing to his brother Theo in July 1884, he explained what he looked for in his subjects: “Coarse, flat faces with low foreheads and thick lips, not that sharp look, but full and Millet-like and with those very clothes.”17Vincent van Gogh, Nuenen, to Theo van Gogh, on or about Wednesday, July 2, 1884, in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 451, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let451/letter.html. Indeed, this distinct physicality is reflected in the figure in the Nelson-Atkins portrait.

The head-and-shoulder study of a young man, whose skin is bronzed as a result of toiling in the sun and who appears in a dark blue-green smock and matching cap, is oriented in a nearly full-frontal perspective. This compositional approach, which Van Gogh utilized in many other works from this series, facilitates a direct and engaging interaction between viewer and subject, providing insight into the character of these hardy people. Van Gogh’s somber palette takes inspiration from Rembrandt’s Supper at Emmaus, which as previously noted, he saw in Paris and avidly read about in Les maîtres d’autrefois (The Masters of Past Times), a treatise by French painter and critic Eugène Fromentin (1820–1876).18See Vincent van Gogh, Nuenen, to Theo van Gogh, mid-June 1884, in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 450, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let450/letter.html. Fromentin noted Rembrandt’s use of a “palette [that] affects a sobriety suited to the circumstances” of the subject matter.19Eugène Fromentin, The Masters of a Past Time, or Criticism on the Old Flemish and Dutch Paintings (London: J. M. Dent and Sons, 1913), 273, originally published as Maitres d’Autresfois: Belgique, Hollande (Paris: E. Plon, 1876), 367. Van Gogh was also acutely aware of Millet’s palette, which he liked to describe as depicting peasants in the very hue of the soil they cultivated.20In his letters, Van Gogh often spoke of how Millet’s palette derived from the soil, which the former had read about in Alfred Sensier, La Vie et l’Oeuvre de J. F. Millet (Paris: A. Quantin, 1881), 127: “Il y a du grandiose et du style dans cette figure au geste violent, à la tournure fièrement délabrée, et qui semble peinte avec la terre qu’il ensemence” (There is something imposing and stylish about this figure [The Sower, 1850; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston] with its violent gesture, and proudly run-down bearing, which seems to be painted with the very soil which he sows). See also Vincent van Gogh, Nuenen, to Theo van Gogh, April 21, 1885, in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 495, n9, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let495/letter.html. Similarly, Van Gogh opted for an earth-toned palette to capture both his subjects and their surroundings. His goal was to convey the essence of “a dusty potato, unpeeled.”21Vincent van Gogh, Nuenen, to Theo van Gogh, on or about Saturday, May 2, 1885, in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 499, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let499/letter.html: “I had finished all the heads and even finished them with great care—but I quickly repainted them without mercy, and the color they’re painted now is something like the color of a really dusty potato, unpeeled of course. While I was doing it I thought again about what has so rightly been said of Millet’s peasants—‘His peasants seem to have been painted with the soil they sow.’” Emphasis original. In the Nelson-Atkins painting, Van Gogh loaded his brush with red and yellow ochers and chrome orange,22For a more thorough analysis of pigments Van Gogh utilized in this composition, see the accompanying technical essay by Mary Schafer and John Twilley. Incidentally, as advanced by Schafer and Twilley, Van Gogh’s use of chrome orange helps to secure the new proposed date of March 1885. among other pigments, and skillfully laid in the features of the sitter’s ruddy complexion (a complementary color pairing with his blue-tinged jacket) and large, penetrating dark eyes rimmed in flickering semicircles of gold. This brilliant highlight, painted quickly wet-into-wetwet-into-wet: An oil painting technique which involves blending of colors on the picture surface., appears again down the bridge of the sitter’s flat nose and helps define his chin and plump lips.23Louis van Tilborgh indicates that the majority of the heads were painted swiftly, with the exception of the woman with the red cap, who seems to have been realized in more than one sitting. See van Tilborgh and Vellekoop, Vincent Van Gogh: Paintings, 1:87. The bravura brushwork, and the speed at which it appears to have been executed, recalls the work of earlier Dutch Masters like Frans Hals (1582–1666) and Rembrandt, to whom Van Gogh saw himself as a modern successor.24Van Gogh wrote to Theo about the Dutch proclivity for painting quickly; see Vincent van Gogh, Nuenen, to Theo van Gogh, on or about Tuesday, October 13, 1885, in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 535, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let535/letter.html. For a focused study on this topic, see Griselda Pollock, “Vincent Van Gogh and Dutch Art: A Study of the Development of Van Gogh’s Notion of Modern Art with Special Reference to the Critical and Artistic Revival of Seventeenth-Century Dutch Art in Holland and France in the Nineteenth Century” (PhD diss., Courtauld Institute of Art, London University, 1980), cited in Dorn et al., Van Gogh Face to Face: The Portraits, 43n47. Pollock suggests that Van Gogh’s interest in Rembrandt’s Supper at Emmaus was probably heightened by Fromentin’s review. Brigid M. Boyle has connected Paul Cezanne’s painting of a laborer, Man with a Pipe and its halo affect, to Catholic holy cards. Read more in this catalogue, Boyle, “Paul Cezanne, Man with a Pipe, 1890–1892,” catalogue entry.

Van Gogh continued to grapple with the challenge of expressing light through opposition with dark, a technical puzzle he had been wrestling with since at least mid-June 1884. He corresponded with Theo about a specific passage in Fromentin’s Les Maîtres d’autrefois, which he interpreted as “starting in a low register and making colors that are still relatively dark appear light.”32Vincent van Gogh, Nuenen, to Theo van Gogh, mid-June 1884, in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 450, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let450/letter.html. This strategy of light is vividly demonstrated in the Nelson-Atkins painting and thoughtfully elucidated by paintings conservator Mary Schafer and Mellon Conservation Science Advisor John Twilley in their accompanying technical essay. Beyond its technical aspects, working from dark to light carried a profound symbolic significance during this phase of Van Gogh’s artistic production.

Van Gogh regarded the labor-worn people whom he depicted in such dark earthy tones as the most deserving recipients of eternal light and life. In the Nelson-Atkins composition, he conveyed this sentiment in part by situating the light source, akin to a halo, directly behind the figure’s head. While some of the artist’s compositions employ a light source coming from one side, the halo effect is a relative rarity within this series. Through this approach, he effectively illuminated the inherent sanctity of his subject. Years later he wrote to Theo: “I’d like to paint men or women with that je ne sais quoi of the eternal, of which the halo used to be the symbol, and which we try to achieve through the radiance itself, through the vibrancy of our colorations.”33Vincent van Gogh, Arles, to Theo van Gogh, September 1888, in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 673, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let673/letter.html. He began to explore conveying the eternal in his series of peasants’ heads and then extended that approach with The Potato Eaters (see Fig. 1), where an enveloping plume of steam rises from the plate of potatoes and surrounds the central figure. This connection symbolically links the Nelson-Atkins Head of a Man to Van Gogh’s most ambitious figural composition.

Van Gogh’s art, particularly his peasant series, transcended mere representation. It served as a conduit for him to express reverence for the ordinary, the humble, and the divine in everyday life. This spiritual dimension, often intertwined with his exploration of light and its symbolic significance, underscores the importance of the Nelson-Atkins painting. Ultimately, Van Gogh’s Head of a Man, like many of his Nuenen works, beckons us to contemplate the interplay between the finite and the infinite, the material and the spiritual. It serves as a testament to his unwavering commitment to capturing the essence of rural life, revealing the profound spirituality he found in the mundane.

Notes

-

Van Gogh spent two periods living in The Hague, from July 30, 1869, until May 10, 1873, and from November 27, 1881, to September 11, 1883. In between these sojourns, he spent time in France, England, Belgium, and elsewhere in the Netherlands.

-

Vincent van Gogh, Nuenen, to Theo van Gogh, Monday, April 6, 1885, published in Leo Jansen, Hans Luijten, and Nienke Bakker, eds., Vincent Van Gogh: The Letters, online edition (Amsterdam and The Hague: Van Gogh Museum and Huygens, 2009), no. 490, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let490/letter.html. All English translations of Van Gogh’s letters are from this publication

-

Van Gogh left The Hague on September 11, 1883, and spent nearly three months in Drenthe, a province in the northeastern part of the Netherlands, before taking a train to Nuenen, where his parents lived. For more on this moment in Van Gogh’s career, see J. Dijk Wout and Meent W. van der Sluis, De Drentse Tijd Van Vincent Van Gogh: Een Onderbelichte Periode Nader Onderzocht, 1883 (Groningen: Boon Uitg, 2001).

-

Many scholars have made this observation, including Bregje Gerritse in The Potato Eaters: Van Gogh’s First Masterpiece, exh. cat. (Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum, 2022), 31–32. Van Gogh mentions a painting by Israëls, presumed to be Peasant Family at the Table (1882; Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam), in a letter to Theo, Saturday, March 11, 1882, in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 211, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let211/letter.html.

-

For additional insight on this topic, see Martin Bailey and Debora Silverman, Van Gogh in England: Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (London: Barbican Art Gallery, 1992), cited in George Keyes, “The Dutch Roots of Vincent van Gogh,” in Roland Dorn et al., Van Gogh Face to Face: The Portraits, exh. cat. (Detroit: Detroit Institute of Arts, 2000), 24n17. For a more recent publication about Van Gogh’s nineteenth-century sources, see Eik Kahng, Through Vincent’s Eyes: Van Gogh and His Sources (Santa Barbara, CA: Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 2021).

-

See Vincent van Gogh, Paris, to Theo van Gogh, May 31, 1875, in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 34, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let034/letter.html.

-

The idea of finding the spiritual in the everyday, particularly among the working classes, aligned with the practice of Van Gogh’s father during his ministry of the Dutch Reformed Church in the rural farming community of Zundert in the southern Netherlands region of Brabant. For more on the region and this branch of religion, see Deborah Silverman, Van Gogh and Gauguin: The Search for Sacred Art (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2000), 143–51. Van Gogh makes the subjects of the Potato Eaters Catholic, however, through his inclusion of the devotional print of the Crucifixion with the Virgin Mary and St. John; see Louis van Tilborgh and Marije Vellekoop, Vincent Van Gogh: Paintings, vol. 1, Dutch Period, 1881–1885, Van Gogh Museum (London: Lund Humphries, 1999), 138–39.

-

During Van Gogh’s second sojourn in The Hague, he embarked on his “Series of the People” drawn from life. His aim was to create lithographs that could be commercially available at a small cost. Van Gogh conceived of another series, entitled “Heads of the People,” inspired by images of laborers in Hubert von Herkomer’s series of the same title, featured in The Graphic from 1875 to 1885. See Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, Saturday, June 3, 1882, in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 235, n37, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let235/letter.html.

-

See Vincent van Gogh, Nuenen, to Theo van Gogh, between about February 5 and 26, 1885, in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 483, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let483/letter.html. Also cited in Tilborgh and Vellekoop, Vincent Van Gogh: Paintings, 1:84n2–4.

-

See Vincent van Gogh, Nuenen, to Theo van Gogh, November 2, 1884, no. 468, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let468/letter.html; November 17, 1884, no. 470, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let470/letter.html; and on or about December 14, 1884, no. 475, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let475/letter.html, all in Jansen et al., Letters (also cited in Tilborgh and Vellekoop, Vincent Van Gogh: Paintings, 1:84n3).

-

Tilborgh and Vellekoop state that the last time Van Gogh discussed the heads was in June 1885. See Vincent van Gogh, Nuenen, to Theo van Gogh, on or about June 2, 1885, in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 506, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let506/letter.html, cited in Tilborgh and Vellekoop, Vincent Van Gogh: Paintings, 1:84n2–4.

-

Van Gogh’s reading of John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress (1678) in or around 1876 reinforced this belief. See Vincent van Gogh, Isleworth, to Theo van Gogh, November 3, 1876, no. 96, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let096/letter.html, and Vincent van Gogh, Isleworth, to Theo van Gogh, November 25, 1876, no. 99, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let099/letter.html, both in Jansen et al., Letters. Bunyan argued that God’s grace favored those who were modest, selfless, and detached from worldly wealth, qualities that Van Gogh associated with workers and the poor. See also Deborah Silverman, “Pilgrim’s Progress and Vincent van Gogh’s Metier,” in Bailey and Silverman, Van Gogh in England, 100.

-

Van Gogh had been practicing as a minister to the coal mining families in the Borinage for approximately six months, and the local evangelical committee decided he was not well suited to the profession. See Vincent van Gogh, Brussels, to Theo van Gogh, Tuesday, August 5, 1879, in Jansen et al., Letters, no.153, n8, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let153/letter.html

-

Deborah Silverman makes this point in Van Gogh and Gauguin, 109.

-

Nienke Bakker makes this point in “On Rustics and Labourers: Van Gogh and ‘the People,’” in Chris Stolwijk and Nienke Bakker, Van Gogh’s Imaginary Museum: Exploring the Artist’s Inner World (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2003), 87.

-

Van Gogh’s concept of specific character types draws from the pseudoscience of physiognomy, which attributed a person’s personality and character to their physical appearance. He was familiar with Johann Caspar Lavater and Franz Joseph Gall’s book Physiognomie et phrénologie rendues intelligibles pour tout le monde (1862), which he read in 1880. See Vincent van Gogh, Brussels, to Theo van Gogh, Monday, November 1, 1880, in Jansen et al., Letters, no.160, n8, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let160/letter.html.

-

Vincent van Gogh, Nuenen, to Theo van Gogh, on or about Wednesday, July 2, 1884, in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 451, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let451/letter.html.

-

See Vincent van Gogh, Nuenen, to Theo van Gogh, mid-June 1884, in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 450, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let450/letter.html.

-

Eugène Fromentin, The Masters of a Past Time, or Criticism on the Old Flemish and Dutch Paintings (London: J. M. Dent and Sons, 1913), 273, originally published as Maitres d’Autresfois: Belgique, Hollande (Paris: E. Plon, 1876), 367.

-

In his letters, Van Gogh often spoke of how Millet’s palette derived from the soil, which the former had read about in Alfred Sensier, La Vie et l’Oeuvre de J. F. Millet (Paris: A. Quantin, 1881), 127: “Il y a du grandiose et du style dans cette figure au geste violent, à la tournure fièrement délabrée, et qui semble peinte avec la terre qu’il ensemence” (There is something imposing and stylish about this figure [The Sower, 1850; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston] with its violent gesture, and proudly run-down bearing, which seems to be painted with the very soil which he sows). See also Vincent van Gogh, Nuenen, to Theo van Gogh, April 21, 1885, in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 495, n9, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let495/letter.html.

-

Vincent van Gogh, Nuenen, to Theo van Gogh, on or about Saturday, May 2, 1885, in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 499, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let499/letter.html: “I had finished all the heads and even finished them with great care—but I quickly repainted them without mercy, and the color they’re painted now is something like the color of a really dusty potato, unpeeled of course. While I was doing it I thought again about what has so rightly been said of Millet’s peasants—‘His peasants seem to have been painted with the soil they sow.’” Emphasis original.

-

For a more thorough analysis of pigments Van Gogh utilized in this composition, see the accompanying technical essay by Mary Schafer and John Twilley. Incidentally, as advanced by Schafer and Twilley, Van Gogh’s use of chrome orange helps to secure the new proposed date of March 1885.

-

Louis van Tilborgh indicates that the majority of the heads were painted swiftly, with the exception of the woman with the red cap, who seems to have been realized in more than one sitting. See van Tilborgh and Vellekoop, Vincent Van Gogh: Paintings, 1:87.

-

Van Gogh wrote to Theo about the Dutch proclivity for painting quickly; see Vincent van Gogh, Nuenen, to Theo van Gogh, on or about Tuesday, October 13, 1885, in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 535, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let535/letter.html. For a focused study on this topic, see Griselda Pollock, “Vincent Van Gogh and Dutch Art: A Study of the Development of Van Gogh’s Notion of Modern Art with Special Reference to the Critical and Artistic Revival of Seventeenth-Century Dutch Art in Holland and France in the Nineteenth Century” (PhD diss., Courtauld Institute of Art, London University, 1980), cited in Dorn et al., Van Gogh Face to Face: The Portraits, 43n47. Pollock suggests that Van Gogh’s interest in Rembrandt’s Supper at Emmaus was probably heightened by Fromentin’s review.

Brigid M. Boyle has connected Paul Cezanne’s painting of a laborer, Man with a Pipe and its halo affect, to Catholic holy cards. Read more in this catalogue, Boyle, “Paul Cezanne, Man with a Pipe, 1890–1892,” catalogue entry.

-

The halo effect around the Nelson-Atkins head is different from what Van Gogh would later incorporate into some of his self-portraits. See his Self Portrait, September–October 1887, oil on cotton, 17 1/2 x 14 5/8 in. (44.5 x 37.2 cm) Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, https://www.vangoghmuseum.nl/en/collection/s0016V1962.

-

See Vincent van Gogh, Nuenen, to Theo van Gogh, on or about Monday, March 2, 1885, in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 484, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let484/letter.html.

-

This was not the first time that Van Gogh positioned figures against windows. He had also done so in Etten and The Hague. However, his concern there was not on the light effects, as it is here. Louis van Tilborgh makes this point in Tilborgh and Vellekoop, Vincent Van Gogh: Paintings, 1:118.

-

See Vincent van Gogh, Nuenen, to Theo van Gogh, between about Monday, March 9, and about Monday, March 23, 1885, in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 485, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let485/letter.html.

-

The six paintings identified from sketches in Van Gogh’s letters include the following: Woman Sewing (March–April 1885; Van Gogh Museum, F71/JH719), Head of a Woman (March 1885; Van Gogh Museum, F70a/JH716), Woman at Table (March–April 1885; Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, F72/JH718), Peasant Woman, Seen Against the Window (March 1885; Asahi Beer Oyamazaki Villa Museum of Art, Japan, F70/ JH715), Peasant Woman, Peeling Potatoes, Seen against the Window (March 1885; private collection, F73/JH717), and Interior with Peasant Woman Sewing (March 1885; location unknown, F157/JH712). See Louis van Tilborgh and Marije Vellekoop, Vincent van Gogh: Paintings, 1:118–20. See also the accompanying technical essay by Mary Schafer and John Twilley, n9. Van Gogh’s works are referenced by F numbers or JH numbers from the catalogues raisonnés: J.-B. de la Faille, The Works of Vincent van Gogh: His Paintings and Drawings, rev. ed. (Amsterdam: Meulenhoff International, 1970); and Jan Hulsker, The New Complete Van Gogh: Paintings, Drawings, Sketches; Revised and Enlarged Edition of the Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of Vincent Van Gogh, rev. ed. (Amsterdam: J. M. Meulenhoff, 1996).

-

Louis van Tilborgh makes this point in Tilborgh and Vellekoop, Vincent Van Gogh: Paintings, 1:95.

-

See accompanying technical essay by Schafer and Twilley, specifically Fig. 10.

-

Vincent van Gogh, Nuenen, to Theo van Gogh, mid-June 1884, in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 450, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let450/letter.html.

-

Vincent van Gogh, Arles, to Theo van Gogh, September 1888, in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 673, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let673/letter.html.

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Mary Schafer and John Twilley, “Vincent van Gogh, Head of a Man, 1885,” technical entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.735.2088.

MLA:

Schafer, Mary, and John Twilley. “Vincent van Gogh, Head of a Man, 1885,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.735.2088.

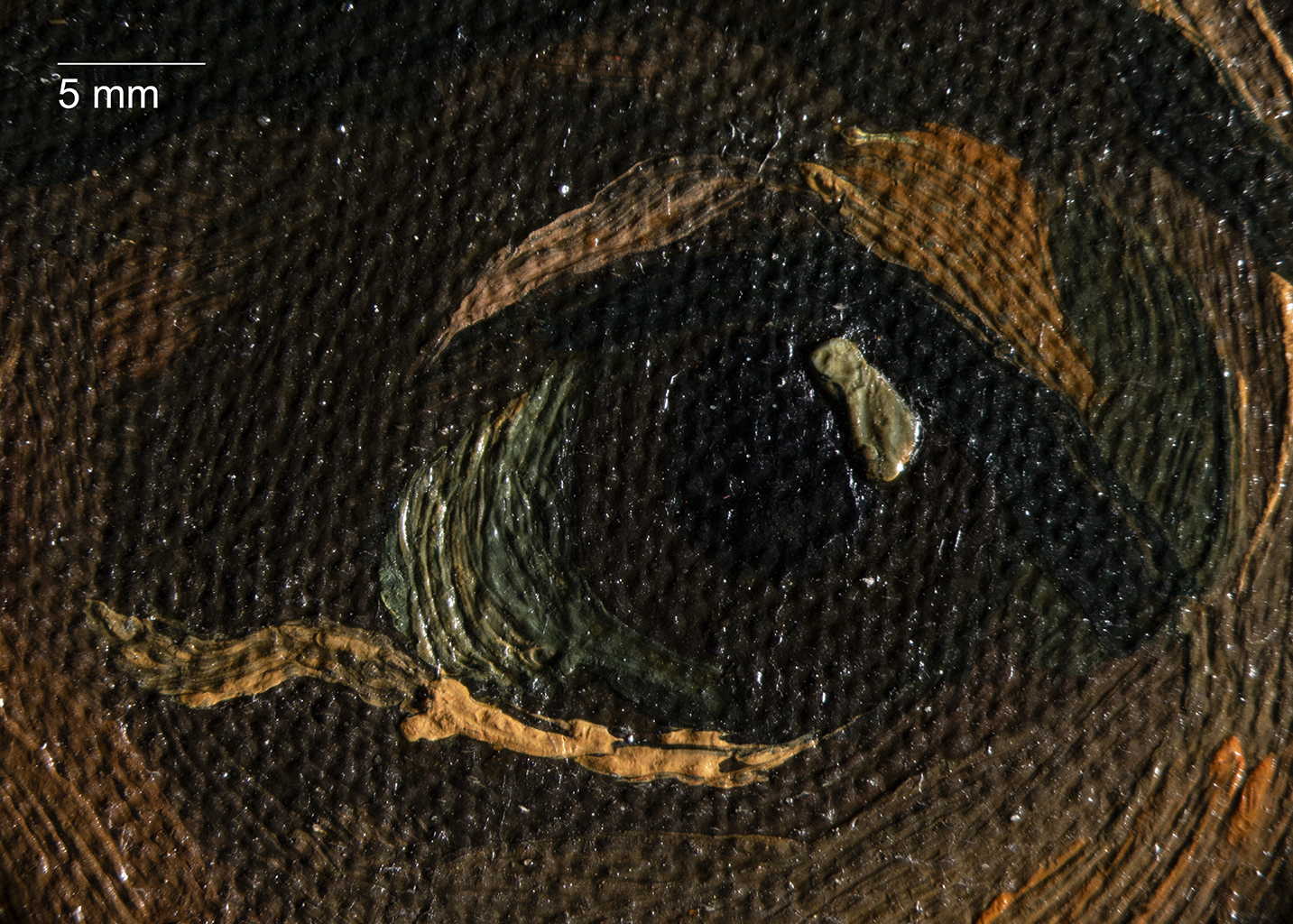

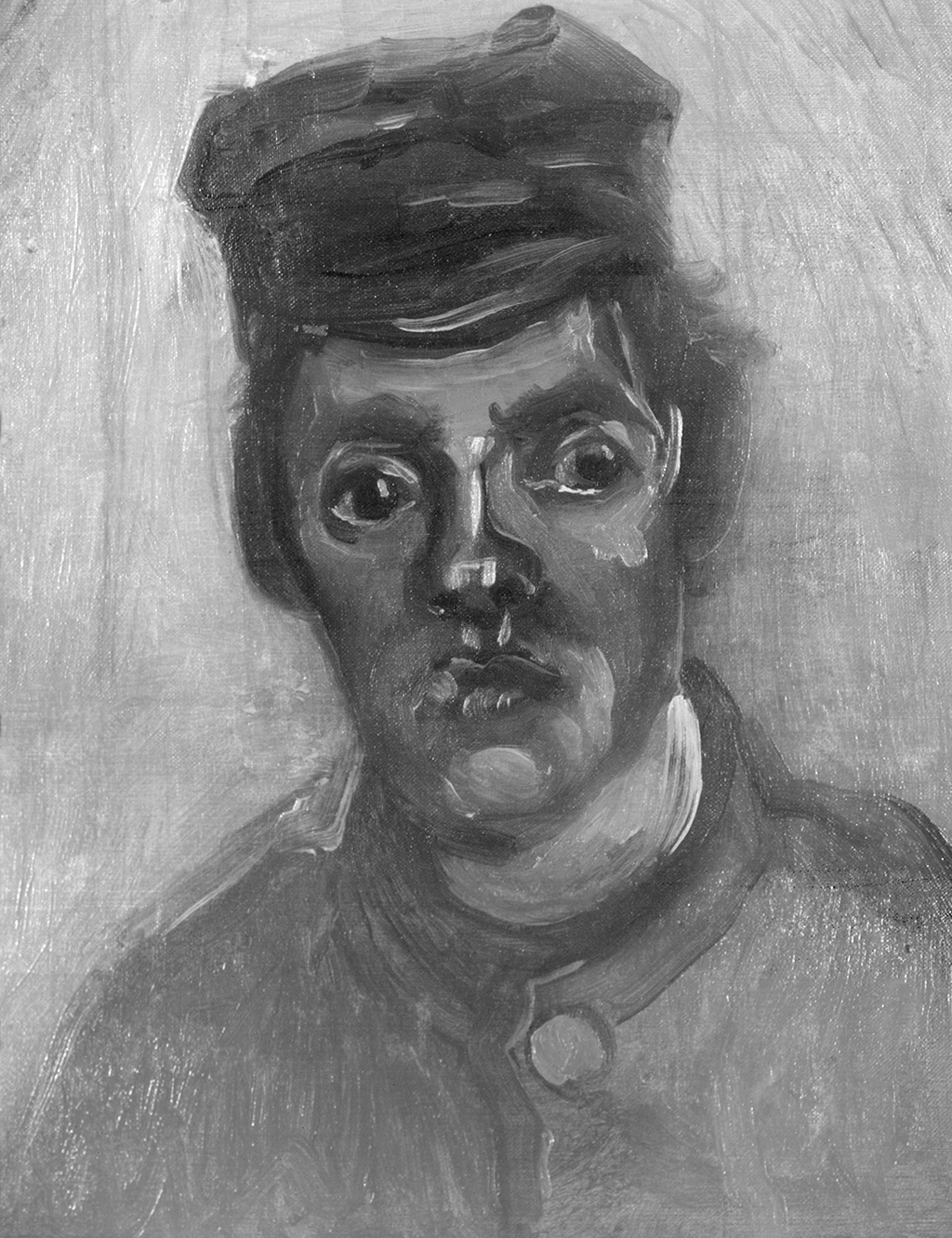

Rendered in the somber tones of his Dutch palette, Vincent van Gogh’s Head of a Man explores light and color with loose, bold brushwork. The prevalence of wet-over-wetwet-over-wet: An oil painting technique which involves drawing a stroke of one color across the wet paint of another color. painting suggests that the study was completed quickly, perhaps in a single session, and overlapping paint strokes confirm that Van Gogh worked over the entire canvas all at once. Blue-brown paint of the man’s hat overlaps the light background, and a stroke of beige paint from the background covers the figure’s proper right ear (Fig. 6). In the lower left, the paint colors of the background and jacket intermix (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6. Photomicrograph of the proper right ear, Head of a Man (1885)

Fig. 6. Photomicrograph of the proper right ear, Head of a Man (1885)

Fig. 7. Detail of the jacket and background at lower left, Head of a Man (1885)

Fig. 7. Detail of the jacket and background at lower left, Head of a Man (1885)

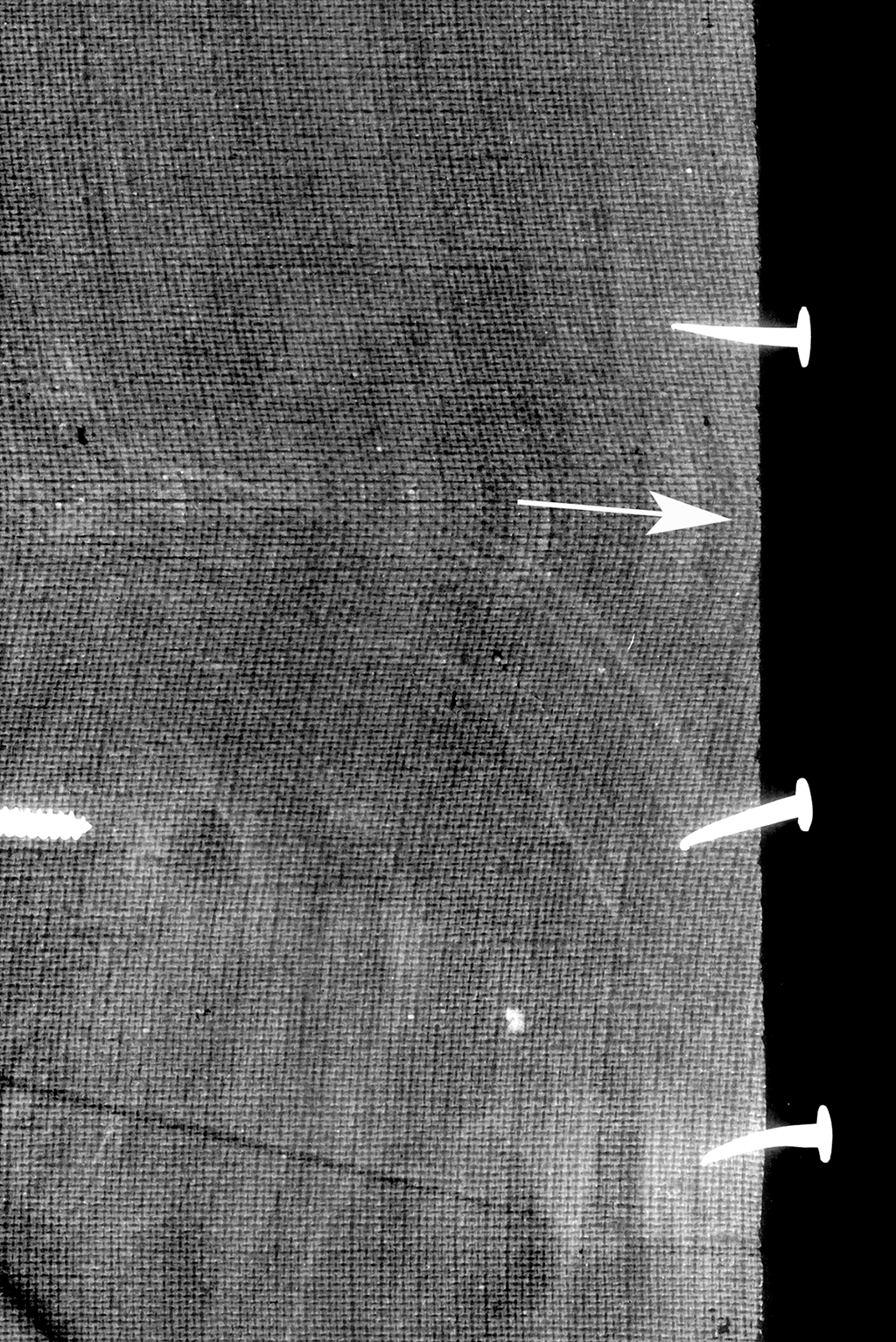

Fig. 8. Detail of radiograph, Head of a Man (1885), showing the cusping of the canvas on the lower right

Fig. 8. Detail of radiograph, Head of a Man (1885), showing the cusping of the canvas on the lower right

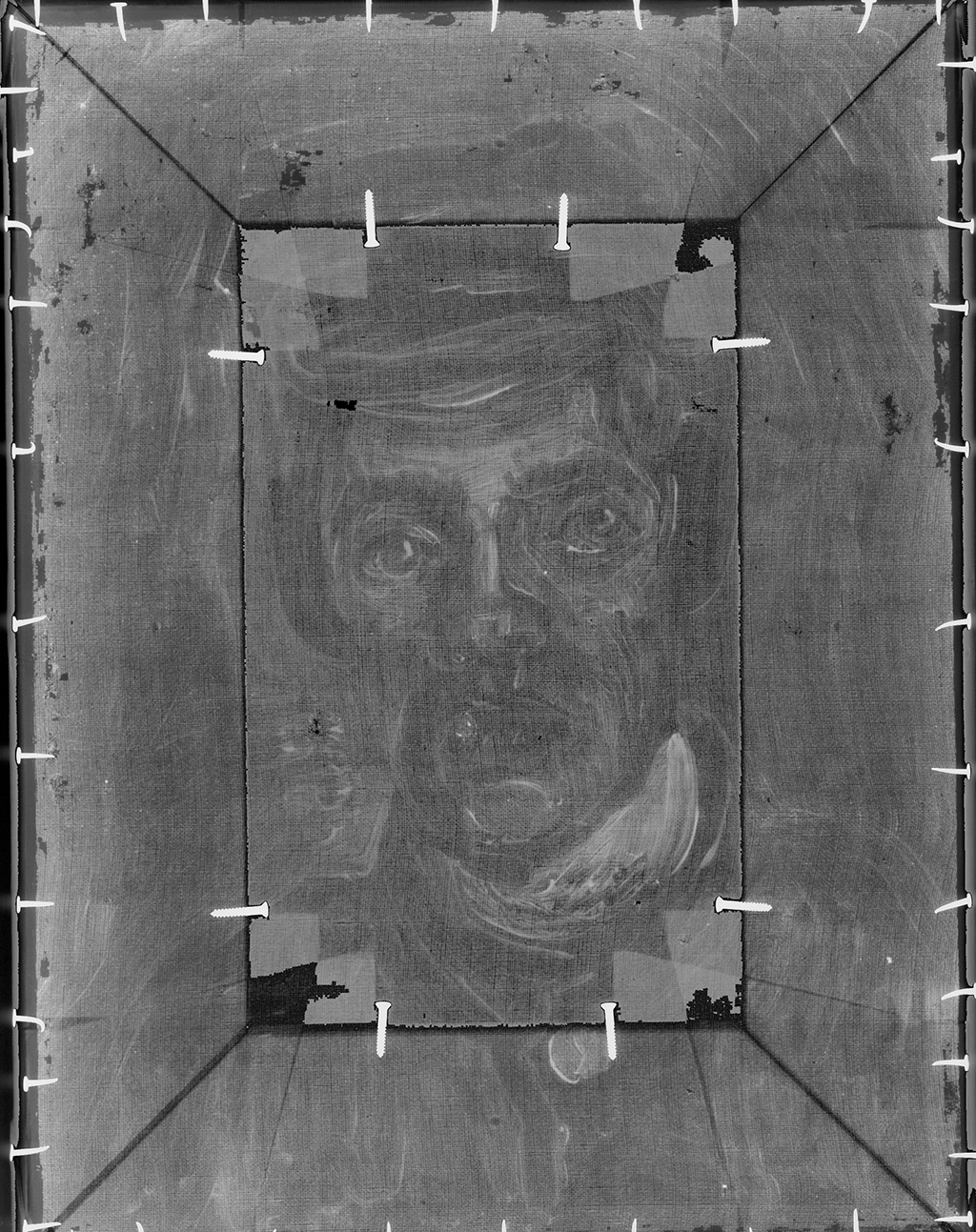

Fig. 9. Radiograph of Head of a Man (1885), a composite of two radiographs captured at different exposures in order to minimize the thick, underlying stretcher members

Fig. 9. Radiograph of Head of a Man (1885), a composite of two radiographs captured at different exposures in order to minimize the thick, underlying stretcher members

Like he did with other head studies from this period, Van Gogh blocked in the principal forms with thin, fluid paint: blue-green paint forms the basis of the jacket; shades of dark brown lie beneath the face; and a beige tone covers the background. The composition was further developed with subsequent paint strokes, working from dark to light colors. In fact, the brightest highlights on the eyes, nose, and neck consist of a medium-toned yellow-orange paint that appears lighter when juxtaposed against shades of brown. In his letters, Van Gogh described a similar approach by Dutch artist Jozef Israëls (1824–1911): “I read Les Maîtres d’Autrefois by Fromentin with great pleasure. And in different places in that book I again found the same questions dealt with that have preoccupied me very much recently, and about which I actually think continually, specifically since, at the end of my time in The Hague, I indirectly heard things that Israëls had said about starting in a low register and making colors that are still relatively dark appear light. In short, expressing light through opposition with dark.”7Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, mid-June 1884, in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 450, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let450/letter.html. In reference to The Potato Eaters (April–May 1885; Van Gogh Museum), Van Gogh described the low key of the dark scene and that the lighter colors “appear as lights on the canvas because of the strong forces that are opposed to them.” See Vincent van Gogh to Anthon van Rappard, on or about August 18, 1885, in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 528, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let528/letter.html

Overall the study is thinly painted, though there are limited areas of

low impastoimpasto: A thick application of paint, often creating texture such as peaks and ridges., like the thicker paint strokes around the eyes (Fig.

11). With round brushes up to 5/8-inch wide, Van Gogh surrounded

the figure with numerous wet-into-wetwet-into-wet: An oil painting technique which involves blending of colors on the picture surface., curving strokes that transition

from pale green at the center to medium green at the outer edges. The

fluidity of the pale green allows the warm beige underpaintingunderpainting: The first applications of paint that begin to block in color and loosely define the compositional elements. Also called ébauche. to be

apparent in areas, and the underlying canvas weave texture is prominent.

While the pale green adjacent to the figure produces a backlighting

effect, highlights on the neck and face suggest a second source of

light, directed at the sitter from the lower right.

Lead is present throughout the figure, and the antimony map confirms the

presence of Naples yellow, a compound of lead and antimony (Fig. 13), often in combination with

chrome yellow and orange and located throughout the background, facial

highlights, and neck. Chrome orange, a pigment that Van Gogh introduced

onto his palette in March of 1885,11Geldof and Megens, “Van Gogh’s Dutch Palette,” Van Gogh’s Studio Practice, 236. was found in abundance and

identified by Raman spectroscopy.

Although Van Gogh is said to have withdrawn red lake from his palette while in Nuenen, organic red and red-brown pigments were identified in the flesh tones of Portrait of a Peasant (April 1885; Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, F163; Fig. 3) and the background of a slightly later work completed in Antwerp, Head of an Old Woman (December 1885; Van Gogh Museum, F174), respectively.13Defeyt et al., “Survey on Van Gogh’s Early Painting Technique,” 4–5., 14Maarten van Bommel, Muriel Geldorf, and Ella Hendriks, “An Investigation of Organic Red Pigments used in Paintings by Vincent van Gogh (November 1885 to February 1888),” Art Matters: Netherlands Technical Studies in Art 3 (2005): 116, 129, 134. For the Nelson-Atkins study, fine red particles resembling lake pigments were observed across the paint surface (proper right nostril, darkest blue of the hat and jacket, brown passages on the face, and the stroke of orange on the neck), although no lake pigments were identifiable with SEM-based elemental analyses.

Only minor adjustments were made to the figure’s shoulders and proper left ear. However, a more substantial artist change is evident in the background, where the vertical and horizontal sketch lines seem to roughly mark a window that was never developed further. In a letter dated March of 1885, Van Gogh described his exploration of subjects placed in front of a window:

Should I get a clear idea of how to achieve the effects that I have in mind . . . Namely figures against the light from a window. I have studies of heads for it, both against the light and facing the light, and I’ve already worked on the whole figure several times, seamstress winding yarn, or peeling potatoes. Full face and in profile. I don’t know whether I’ll get it finished, though, because it’s a difficult effect. Still, I think I’ve learned a few things from it.15Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, March 23, 1885, in Jansen et al, The Letters, no. 485, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let485/letter.html. The English translation is from this publication.

The window sketch combined with the presence of chrome orange suggests that the Nelson-Atkins study was completed closer to the spring of 1885, a period when Van Gogh explored this type of lighting effect and sketched several window studies in his letters.16Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, April 4, 1885, in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 489, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let489/letter.html. Six paintings have been identified from these sketches,17The six paintings identified from sketches in Van Gogh’s letters include the following: Woman Sewing (March–April 1885; Van Gogh Museum, F71/JH719), Head of a Woman (March 1885; Van Gogh Museum, F70a/JH716), Woman at Table (March–April 1885; Kröller-Müller, Otterlo, F72/JH718), Peasant Woman, Seen Against the Window (March 1885; Asahi Beer Oyamazaki Villa Museum of Art, Japan, F70/ JH715), Peasant Woman, Peeling Potatoes, Seen against the Window (March 1885; private collection, F73/JH717), Interior with Peasant Woman Sewing (March 1885; location unknown, F157/JH712). See Tilborgh and Vellekoop, Vincent van Gogh Paintings, 1:118–20. including Head of a Woman (Fig. 4), a painting of a woman silhouetted by a windowpane backdrop. In terms of construction and technique, several parallels can be drawn between this study and the Nelson-Atkins painting. For Head of a Woman, Van Gogh drew the windowpanes with horizontal and vertical sketch lines, underpainted passages with thin paint colors, and used fluid, pale green paint to render light and to allow the beige underpainting to show through, all of which is comparable to the Nelson-Atkins painting.18Tilborgh and Vellekoop, Vincent Van Gogh Paintings, 1:119–22, fig. 22c. “Head of a Woman (cat. 22) is smoothly painted. In some places—for example, in the window—the paint layer is so thin that the cream-coloured primer shows through. Infrared reflectography revealed traces of underdrawing on this ground layer. Lines clearly related to the painted image appeared in various parts of the woman’s cap and throat, where they run parallel to her shawl, indicating that it was originally located slightly higher. There are also several horizontal and vertical lines; these seem to represent the window panes. This preparatory sketch was followed by a division of the canvas into monochrome passages, which in turn were worked up into areas of light and shade. The base tone for the woman’s face is brown, for the window a light grey-green, and for the cap a greenish blue.”

The tacking edges of Head of a Man have been removed, and it is unclear whether the dimensions have been altered. Early documentation of the painting, written shortly after its 1937 acquisition, refers to the wooden panel as a “later mounting”19James Roth, handwritten on an envelope that contained labels removed from the panel reverse (now encapsulated), Nelson-Atkins conservation file, 37-1. attached with “strong furniture glue.”20James Roth, April 1940, treatment report, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, 37-1. Few characteristic features remain on the painting that could indicate what type of auxiliary support was first used (i.e. canvas tacked to the wall, canvas mounted to cardboard, or canvas on stretcherstretcher: A wooden structure to which the painting’s canvas is attached. Unlike strainers, stretchers can be expanded slightly at the joints to improve canvas tension and avoid sagging due to humidity changes or aging.). For instance, there is no evidence of pinholes at the outer edges or four corners, like those on Woman Sewing (March–April 1885; Van Gogh Museum, F71/JH719)21Tilborgh and Vellekoop, Vincent van Gogh Paintings, 1:122. to indicate that Van Gogh tacked the canvas to a rigid surface prior to painting. Sharp folds or cracks at the painting corners, often signaling the weak corners of a cardboard support, are also absent.22Tilborgh and Vellekoop, Vincent van Gogh Paintings, 1:21–22, 36n.

Fig. 15. Detail of the Kunsthandel Oldenzeel label that was removed from the former panel and encapsulated, Head of a Man (1885)

Fig. 15. Detail of the Kunsthandel Oldenzeel label that was removed from the former panel and encapsulated, Head of a Man (1885)

Fig. 16. Photomicrograph of the outer edge of Head of a Man (1885), showing remnants of red-brown paper

Fig. 16. Photomicrograph of the outer edge of Head of a Man (1885), showing remnants of red-brown paper

Fig. 17. Photograph captured during the 1940 treatment, showing Head of a Man (1885) with raking illumination

Fig. 17. Photograph captured during the 1940 treatment, showing Head of a Man (1885) with raking illumination

Fig. 18. Photograph captured during the 1940 treatment, Head of a Man (1885)

Fig. 18. Photograph captured during the 1940 treatment, Head of a Man (1885)

Notes

-

Film-based x-radiograph, no. 503, April 16, 2015, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, 37-1.

-

C. Richard Johnson Jr., Don H. Johnson, and William A. Sethares, “Study of a Peasant’s Head, Vincent van Gogh, 1885 (F165 / 37-1), from the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art,” unpublished thread count report, June 2023, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, 37-1.

-

For an overview of automated thread counting and Van Gogh’s canvases, see Ella Hendriks, C. Richard Johnson Jr., Don H. Johnson, and Muriel Geldof, “Automated Thread Counting and the Studio Practice Project,” Van Gogh’s Studio Practice, ed. Marije Vellekoop, Muriel Geldof, Ella Hendriks, Leo Jansen, and Alberto de Tagle (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), 156–81.

-

Ella Hendriks and Muriel Geldof, “Van Gogh’s Antwerp and Paris Picture Supports (1885–1888): Reconstructing Choices,” Art Matters: Netherlands Technical Studies in Art 2 (2002): 45.

-

Consisting of a wooden or cardboard frame, often with “lines” of thread or wire that form an inner grid or cross, this tool provided the artist with a focused view of the subject. The segments of the grid could serve as reference points to aid in transferring the subject or design to the support. Van Gogh’s use of a perspective frame to overcome his early struggles with perspective and proportion is discussed in Teio Meedendorp, “The Perspective Frame,” in Van Gogh’s Studio Practice, 133–41.

-

Louis van Tilborgh and Marije Vellekoop, Vincent van Gogh Paintings, vol. 1, Dutch Period 1881–1885, Van Gogh Museum (London: Lund Humphries Publishers, 1999), 87. See also Vincent van Gogh to Anton Kerssemakers, on or about Thursday, July 16, 1885, in Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, no. b880 V/1962; published in Leo Jansen, Hans Luijten, and Nienke Bakker, eds., Vincent van Gogh: The Letters (Amsterdam and the Hague: Van Gogh Museum and Huygens, 2009), no. 518, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let518/letter.html.

-

Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, mid-June 1884, in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 450, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let450/letter.html. In reference to The Potato Eaters (April–May 1885; Van Gogh Museum), Van Gogh described the low key of the dark scene and that the lighter colors “appear as lights on the canvas because of the strong forces that are opposed to them.” See Vincent van Gogh to Anthon van Rappard, on or about August 18, 1885, in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 528, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let528/letter.html.

-

X-ray fluorescence spectrometry elemental mapping was carried out on October 26, 2022. This equipment was constructed as part of a collaboration with the Laboratory of Molecular and Structural Archaeology, directed by Philippe Walter (CNRS/Pierre and Marie Curie University, Paris), by which their instrument design and operational software was provided to the authors.

-

The assignment of individual elements detected by MA-XRF, such as lead, to specific pigments, is limited by the presence of the same element in multiple pigments of the same palette. In this case, lead is known from the MA-XRF work to occur in Naples yellow, for which lead and tin responses are obligatory and demonstrated, and chrome yellow, based upon SEM-based individual particle analyses. In the presence of these two pigments, the simultaneous presence of lead white cannot be ruled out by MA-XRF alone.

-

Zinc white was used in a similar, limited capacity to accent the figure of Head of Peasant (April 1885; Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, F163). See Catherine Defeyt, Dominique Marechal, Francisca Vandepitte, and David Strivay, “Survey on Van Gogh’s Early Painting Technique Through the Non-invasive and Multi-analytical Study of Head of Peasant,” Heritage Science 8 (2020): 4–5. At this time Van Gogh relied on zinc white more than lead white, although it is unclear why. He may have selected zinc white based on its brighter tone, rheological properties, and ability to form a more transparent paint. See Muriel Geldof and Luc Megens, “Van Gogh’s Dutch Palette,” in Van Gogh’s Studio Practice, 237.

-

Geldof and Megens, “Van Gogh’s Dutch Palette,” Van Gogh’s Studio Practice, 236.

-

The authors are grateful to Marco Leona, head of the research lab of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, who carried out a small number of additional Raman spectroscopy analyses.

-

Defeyt et al., “Survey on Van Gogh’s Early Painting Technique,” 4–5.

-

Maarten van Bommel, Muriel Geldorf, and Ella Hendriks, “An Investigation of Organic Red Pigments used in Paintings by Vincent van Gogh (November 1885 to February 1888),” Art Matters: Netherlands Technical Studies in Art 3 (2005): 116, 129, 134.

-

Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, March 23, 1885, in Jansen et al, The Letters, no. 485, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let485/letter.html. The English translation is from this publication.

-

Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, April 4, 1885, in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 489, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let518/letter.html.

-

The six paintings identified from sketches in Van Gogh’s letters include the following: Woman Sewing (March–April 1885; Van Gogh Museum, F71/JH719), Head of a Woman (March 1885; Van Gogh Museum, F70a/JH716), Woman at Table (March–April 1885; Kröller-Müller, Otterlo, F72/JH718), Peasant Woman, Seen Against the Window (March 1885; Asahi Beer Oyamazaki Villa Museum of Art, Japan, F70/ JH715), Peasant Woman, Peeling Potatoes, Seen against the Window (March 1885; private collection, F73/JH717), Interior with Peasant Woman Sewing (March 1885; location unknown, F157/JH712). See Tilborgh and Vellekoop, Vincent van Gogh Paintings, 1:118–20.

-

Tilborgh and Vellekoop, Vincent Van Gogh Paintings, 1:119–22, fig. 22c. “Head of a Woman (cat. 22) is smoothly painted. In some places—for example, in the window—the paint layer is so thin that the cream-coloured primer shows through. Infrared reflectography revealed traces of underdrawing on this ground layer. Lines clearly related to the painted image appeared in various parts of the woman’s cap and throat, where they run parallel to her shawl, indicating that it was originally located slightly higher. There are also several horizontal and vertical lines; these seem to represent the window panes. This preparatory sketch was followed by a division of the canvas into monochrome passages, which in turn were worked up into areas of light and shade. The base tone for the woman’s face is brown, for the window a light grey-green, and for the cap a greenish blue.”

-

James Roth, handwritten on an envelope that contained labels removed from the panel reverse (now encapsulated), Nelson-Atkins conservation file, 37-1.

-

James Roth, April 1940, treatment report, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, 37-1.

-

Tilborgh and Vellekoop, Vincent van Gogh Paintings, 1:122.

-

Tilborgh and Vellekoop, Vincent van Gogh Paintings, 1:21–22, 36n.

-

The Oldenzeel label, now encapsulated and located on the back of the painting, was preserved in an envelope with a notation by conservator James Roth: “Labels removed from the back of the panel upon which painting was mounted.”

-

Tilborgh and Vellekoop, Vincent van Gogh Paintings, 1:42, 108.

-

Ribbius Peletier family archive (1813–1993), Brievenboek (1901–1903), letter 367, February 14, 1903, no. 411: “Jammer dat het hout waarop de schilderstukken bevestigd zijn, oogenschijnlijk erg versch is. De stukken trekken zeer krom en ’t zal wenslijk zijn dit gebrek afdoende te verbeteren,” cited in Louis van Tilborgh and Marije Vellekoop, “Van Gogh in Utrecht: the collection of Gerlach Ribbius Peletier (1856–1930),” Van Gogh Museum Journal (1997–1998): 31, https://www.dbnl.org/tekst/_van012199701_01/_van012199701_01_0004.php.

-

James Roth to George Stout, Director of Technical Research, Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, February 29, 1940, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, 37-1.

-

Scott Heffley, April 2, 2007, treatment report, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, 37-1.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago: Meghan L. Gray, “Vincent van Gogh, Head of a Man, 1885,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.735.4033.

MLA:

Gray, Meghan L. “Vincent van Gogh, Head of a Man, 1885,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.735.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Meghan L. Gray, “Vincent van Gogh, Head of a Man, 1885,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.735.4033.

MLA:

Gray, Meghan L. “Vincent van Gogh, Head of a Man, 1885,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.735.4033.

With Kunsthandel Wed. Oldenzeel, Rotterdam, Netherlands, by September 15, 1908, no. 75 [1];

Anna Müller-Abeken (1868–1922), Scheveningen, The Hague, by May 19, 1920 [2];

Her sale, Tableaux et Aquarelles Modernes Provenant de I. Collection G. W. van N . . . à Amsterdam, II. Collection d’un amateur à B . . . , III. Collection W. P. van Ingenegeren à Utrecht, IV. Collection Mme A. Müller-Abeken à Schéveningue, V. Collection M. H. Souget à Bussum, VI. Liquidation de la Société Fierens, De Maeght et Cie á Bruxelles, VII. Diverses Provenances, Frederik Muller et Cie, Amsterdam, May 19, 1920, no. 87, as Portrait d’homme;

With Kunsthandel Huinck und Scherjon, Utrecht, Netherlands, by 1928 [3];

Mlle E. Snellen, Utrecht, Netherlands, by December 10, 1935 [4];

Purchased at her sale, Tableaux Anciens et Modernes Antiquités: Collections et Successions: M.lle.–E. Snellen, Utrecht; M.-H. Klein Van Gogh, Amsterdam; M.-Ruys de Perez, Amsterdam; M.-L. J. Brantjes, Driebergen; Diverses Provenances, Frederik Muller et Cie, Amsterdam, December 10–11, 1935, no. 103, as Portrait d’homme, by Bernheim-Jeune et Cie., Paris, stock no. 26801, as Portrait d’homme, December 13, 1935–February 25, 1936 [5];

Purchased from Bernheim-Jeune et Cie, Paris, probably through Henri-Pierre Roché, Paris, by Theodore Schempp, Brodhead, WI, February 25, 1936–January 18, 1937 [6];

Purchased from Schempp by The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1937.

Notes

[1] See decorative rectangular paper label now attached to the painting’s backing board, middle right side, with green Art Nouveau woman holding a paintbrush, in printed text: Kunsthandel / Wed. Oldenzeel / Rotterdam / 20, Gedempte / Glashaven. / [at left corner of label] Dagelijks / geopend / van / 10-4 [uur.] / [on right side of label] Permanente / Tentoonstelling / van Schilderijen / en Aquarellen / [handwritten in pen] Vincent van Gogh. / No 75 / 15 September 1908. It is not clear if the painting was lent for exhibition or was owned by Oldenzeel. According to Martha Op de Coul, “In search of Van Gogh’s Nuenen Studio: the Oldenzeel Exhibitions of 1903,” Van Gogh Museum Journal (2002): 106, no archives of the Oldenzeel firm appear to have survived.

[2] Anna Müller-Abeken was married to Gustav Harry Müller (1865–1913). His sister was Helene Kröller-Müller (1869–1939), who was an avid Van Gogh collector and later donated her collection to the Dutch government (now the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo). In 1908, Helene Kröller-Müller began hosting lectures in her home by the noted van Gogh enthusiast, H. P. Bremmer (1871–1956), to which she also invited her brother and sister-in-law. According to Teio Meedendorp, Drawings and prints by Vincent van Gogh in the collection of the Kröller-Müller Museum (Delft, The Netherlands: Thieme GrafiMedia Groep, 2007), 274, Mrs. Kröller-Müller passed on the opportunity to buy the painting now in the collection of the Nelson-Atkins.

[3] According to the RKD (Nederlands Instituut voor Kunstgeschiedenis, Netherlands Institute for Art History), the archive for Huinck and Scherjon was destroyed. The painting was in the collection of this dealer when it was published in Jacob-Baart de la Faille, L’Œuvre de Vincent Van Gogh: Catalogue Raisonné (Paris: éditions G. Van Oest, 1928), no. 165.

[4] This is possibly Emma Snellen (1872–1940). Her sister was Kate Dusser de Barenne-Snellen (1883–1931), a small-scale art collector who attended art classes in the 1920s by H. P. Bremmer. According to Hildelies Balk, Kate attended the classes with one of her six sisters, another art collector. Unfortunately, this sister is not identified by name. See Hildelies Balk, “De freule, de professor, de koppman en zijn vrouw, het publiek van H. P. Bremmer,” Jong Holland 2 (1993): 13.

A provenance is listed on a label found on the painting’s backing board, bottom center side, on piece of ledger paper, handwritten in ink: Hauteur HH. Largeur 32. / Peint à Nuenen entre 1883.1885 / Collection Mme : A Muller. Abeken, Schiveningue 1920 / " [ditto marks indicating “Collection”] Melle E Snellen, Utrecht. / " [ditto marks indicating “Collection”] Israël / Reproduit dans : J. B. de la Faille, l’Œuvre de Vincent Van Gogh / catalogue raisonné no: 165.

It is unknown who “Israël” might be. Snellen’s sales catalogue was published by “Atelier Isaac Israels” in 1935. The Dutch artist, Isaac Israël (1865–1934), died almost a year before Snellen’s sale, making it difficult to rectify his ownership in this provenance narrative.

[5] Bernheim-Jeune purchased the painting from the “Hôtel des ventes

d’Amsterdam” on December 13, probably meaning they bought it directly

from Snellen’s sale. See letter from Guy-Patrice Dauberville,

Bernheim-Jeune et Cie, Paris, to Meghan L. Gray, NAMA, September 1, 2011,

NAMA curatorial file. See also small, rectangular label on the

painting’s backing board, middle left side, typewritten: 1936 / No

[handwritten in pen:] 26801 / Van Gogh / Paysan / L.Z. E. Z. It is

unclear to what “L.Z.” might refer.

[6] According to Bernheim-Jeune’s stock books, they sold the painting to “Roche.” See letter from Guy-Patrice Dauberville, Bernheim-Jeune et Cie, Paris, to Meghan L. Gray, NAMA, September 1, 2011, NAMA curatorial file. This was probably Henri-Pierre Roché (1879–1959), a French journalist, author, art collector, advisor, and dealer. By 1919, he was working in Paris as an agent and dealer with many contacts. According to a letter from dealer Theodore Schempp to Paul Gardner, NAMA, January 18, 1937, Schempp purchased the painting from Bernheim-Jeune on July 21, 1936.

For more on these two dealers, see Sean O’Hanlan, “Henri-Pierre Roché,” and Maria Castro, “Theodore Schempp,” in The Modern Art Index Project (August 2018), Leonard A. Lauder Research Center for Modern Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://doi.org/10.57011/NHLY4635 and https://doi.org/10.57011/ACVY8386.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Meghan L. Gray, “Vincent van Gogh, Head of a Man, 1885,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.735.4033.

MLA:

Gray, Meghan L. “Vincent van Gogh, Head of a Man, 1885,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.735.4033.

Vincent van Gogh, Head of a Man, Nuenen, December 1884–January 1885, pencil, pen, brush and ink on paper, 5 5/8 x 3 1/8 in. (14.2 x 8.0 cm), Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation), d0275V1969.

Vincent van Gogh, Head of a Young Man, Nuenen, December 1884–May 1885, pencil on paper, 13 11/16 x 8 1/2 in. (34.7 x 21.6 cm) Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation), d0368V1962.

Vincent van Gogh, Head of a Young Man, Nuenen, December 1884–May 1885, pencil on paper, 13 5/8 x 8 7/16 in. (34.6 x 21.5 cm) Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation), d0424V1962.

Vincent van Gogh, Head of a Young Man with a Pipe, Nuenen, December 1884–May 1885, pencil on paper, 13 1/8 x 8 1/8 in. (33.3 x 20.7 cm) Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation), d0089V1962.

Vincent van Gogh, Head of a Young Man, Nuenen, December 1884–May 1885, chalk on paper, 13 5/8 x 8 5/16 in. (34.6 x 21.1 cm), Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation), d0094V1962v.

Vincent van Gogh, Portrait of a Peasant, Nuenen, March–April 1885, oil on canvas, 15 3/8 x 12 in. (39 x 30.5 cm), Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, Brussels. Acquired through Mr. Jacob Baart de la Faille (1886–1959), inv. 4910.

Vincent van Gogh, Man Seated at a Table, March–April 1885, oil on canvas, 17 7/16 x 12 7/8 in. (44.3 x 32.5 cm), Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, The Netherlands, inv. no. 105.938.

Vincent van Gogh, The Potato Eaters, April–May 1885, oil on canvas, 32 1/4 x 44 7/8 in. (82 x 114 cm), Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation), s0005V1962.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Meghan L. Gray, “Vincent van Gogh, Head of a Man, 1885,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.735.4033.

MLA:

Gray, Meghan L. “Vincent van Gogh, Head of a Man, 1885,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.735.4033.

Kunsthandel Wed. Oldenzeel, Rotterdam, Netherlands, September 15, 1908, no. 75, no cat.

Five Years of Collecting, The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Kansas City, MO, December 4–11, 1938, no cat.

Work by Vincent Van Gogh, Cleveland Museum of Art, November 3–December 12, 1948, no. 2, as Head of Peasant (Portrait de Paysan).

Two Sides of the Medal: French Painting from Gérôme to Gauguin, Detroit Institute of Arts, September 16–October 6, 1954, no. 120, as Head of a Peasant.

Possibly Impressionism: Selections from Five American Museums, The Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, November 4–December 31, 1989, The Minneapolis Institute of Arts, January 27–March 25, 1990, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, March 21–June 17, 1990, The Saint Louis Art Museum, July 14–September 9, 1990, The Toledo Museum of Art, September 30–November 25, 1990, hors cat., as Head of a Peasant.

From Farm to Table: Impressionist and Post-Impressionist Masterworks on Paper, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, August 12, 2017–January 21, 2018, no cat.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Meghan L. Gray, “Vincent van Gogh, Head of a Man, 1885,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.735.4033.

MLA:

Gray, Meghan L. “Vincent van Gogh, Head of a Man, 1885,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.735.4033.

Tableaux et Aquarelles Modernes Provenant de I. Collection G. W. van N . . . à Amsterdam, II. Collection d’un amateur à B . . . , III. Collection W. P. van Ingenegeren à Utrecht, IV. Collection Mme A. Müller-Abeken à Schéveningue, V. Collection M. H. Souget à Bussum, VI. Liquidation de la Société Fierens, De Maeght et Cie á Bruxelles, VII. Diverses Provenances (Amsterdam: Frederik Muller, May 19, 1920), 22, as Portrait d’homme.

Jacob-Baart de la Faille, L’Œuvre de Vincent Van Gogh: Catalogue Raisonné (Paris: éditions G. Van Oest, 1928), no. F165, pp. 1:52, 2pt1:pl. XLIV, (repro.), as Portrait de paysan.

Mensing et Fils, Tableaux Anciens et Modernes Antiquités: Collections et Successionions: M.lle.–E. Snellen, Utrecht; M.-H. Klein Van Gogh, Amsterdam; M.-Ruys de Perez, Amsterdam; M.-L. J. Brantjes, Driebergen; Diverses Provenances (Amsterdam: Atelier Isaac Israels, December 10–11, 1935), 8, as Portrait d’homme.

Gertrude R. Benson, “Exploding the van Gogh Myth,” American Magazine of Art 29, no. 1 (January 1936): 10–11.

Louis Piérard, Van Gogh (Paris: Les Editions Braun et Cie, 1936), (repro.), as Portrait de Paysan.

“Art Throughout America: Kansas City: Van Gogh,” Art News 35, no. 22 (February 27, 1937): 19–20, (repro.), as Portrait of a Peasant.

“Masterpiece of the Month,” News Flashes (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) 3, no. 7 (March 1, 1937): 1–2, as Portrait of a Peasant.

“Head of a Toiler,” Art Digest 11, no. 11 (March 1, 1937): 20, (repro.), as Portrait of a Peasant.

Walther Vanbeselaere, De Hollandsche Periode (1880–1885) in het werk van Vincent Van Gogh (1853–1890) (Antwerp: De Sikkel, 1937), 290, 342, as Boerenkop (de face).

“On Exhibition This Month,” Shoppers’ Guide (March 1937), clipping, Scrapbooks, NAMA archives, (repro.).

The Independent: Kansas City’s Weekly Journal of Society (July 10, 1937), (repro.).

“Local Museums, Art Associations, Other Organizations,” American Art Annual 34 (1937–1938): 282, as Head of a Peasant.

“Museum Directors Have to Play Detective Now and Then,” Kansas City Star 58, no. 210 (April 15, 1938): 14.

“‘Visit Your Gallery Week’ Designated December 4–11,” Kansas City Journal-Post 85, no. 68 (November 27, 1938): 36, as Head of a Peasant.

“Five Years of Collecting,” News Flashes (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) 5, no. 9 (December 1, 1938): 1, Head of a Peasant.

Paul Gardner, “Kansas City: Jubilee and an Acquisition,” Art News 37, no. 10 (December 3, 1938): 19, as Head of a Peasant.

“Kansas City’s Nelson Gallery Celebrates its Fifth Anniversary,” Art Digest 13, no. 6 (December 15, 1938): 7, as Head of a Peasant.

J. D. W., “A Happier View of Van Gogh as Artist Absorbed in Work,” Kansas City Star 59, no. 191 (March 27, 1939): D[16], (repro.), as a peasant head, probably a study for ‘The Potato Eaters.’

J.-B. de la Faille, Vincent van Gogh, trans. Prudence Montagu-Pollock (New York: French and European Publications, 1939), no. 185, p. 153, (repro.), as Portrait of a Peasant.

R. H. Wilenski, Modern French Painters (New York: Reynal and Hitchcock, [1940]), 73, 86, (repro.), as Paysan hollandaise.

The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, The William Rockhill Nelson Collection, 2nd ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1941), 41, 52, 168, (repro.), as Head of a Peasant.

“Masterpiece Room,” Gallery News (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) 8, no. 6 (March 1942): 3, as Portrait of a Peasant Boy.

Rosamund Frost, Contemporary Art: The March of Art from Cézanne until Now (New York: Crown, 1942), vi, 40, (repro.), as Head of a Peasant.

“Gallery Changes: Gallery 19,” Gallery News (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts Museum) 10, no. 3 (November 1943): 5.

Ethlyne Jackson, “Museum Record: Kansas City’s Tenth Birthday,” Art News 42, no. 15, (December 15–31, 1943): 15–16, (repro.), as Head of a Peasant.

Marco Valsecchi, Disegni di Vincent Van Gogh, 2nd ed. (Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1944), 19.

André Leclerc, Van Gogh (New York: Hyperion Press, 1948), 16, (repro.), as Portrait of a Peasant.

Work by Vincent Van Gogh, exh. cat. (Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art, 1948), 12, 15, (repro.), as Head of Peasant (Portrait de Paysan).

Dorothy Adlow, “Art in Kansas City—Music and Theaters—Exhibitions in San Francisco: Masterpieces of Many Schools to Be Seen in Nelson Gallery,” Christian Science Monitor 40, no. 197 (July 17, 1948): 12, as Head of a Peasant.

Jack Levine, “Homage to Vincent,” Art News 47, no. 8 (December 1948): 26, 59, (repro.), as Head of a Peasant.

The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, The William Rockhill Nelson Collection, 3rd ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1949), 66, (repro.), as Head of a Peasant.

“Special Sunday Lecture,” Gallery News (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) 18, no. 10 (November 1951): unpaginated, as Head of Peasant.

The Two Sides of the Medal: French Painting from Gérôme to Gauguin, exh. cat. (Detroit: Detroit Institute of Arts, 1954), 55, 57, as Head of a Peasant.

Ross E. Taggart, “Kansas City Art,” Library Journal 82, no. 12 (June 15, 1957): 1596.

Paul Mahlberg, Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890): Leben und Schaffen, exh. cat. (Essen, Germany: Villa Hügel, 1957), unpaginated.

Ross E. Taggart, ed., Handbook of the Collections in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 4th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1959), 125, (repro.), as Head of a Peasant.

Paolo Lecaldano, L’opera pittorica completa di Van Gogh e i suoi nessi grafici, new series (1966, 1971; repr., Milan: Rizzoli Editore, 1977), no. 106, p. 1:99, (repro.), as Busto di Contadino (con berretto, di fronte).

Jean Leymarie, Who Was Van Gogh?, trans. James Emmons (Geneva: Editions d’Art Albert Skira, 1968), 52.

J.-B. de la Faille, The Works of Vincent van Gogh: His Paintings and Drawings, rev. ed. (Amsterdam: Meulenhoff International, 1970), no. F165 [H185], pp. 96–97, 617, 677, 688, (repro.), as Portrait of a Peasant.

Ross E. Taggart and George L. McKenna, eds., Handbook of the Collections in The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Kansas City, Missouri, vol. 1, Art of the Occident, 5th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1973), 164, (repro.), as Head of a Peasant.

Jacques Lassaigne, Les impressionnistes (Milan: Fratelli Fabbri Editori, 1974), 1:95.

National Catholic Reporter 12, no. 14 (January 30, 1976): 13, (repro.), as Head of a Peasant.

Jan Hulsker, Van Gogh en zijn weg: Al zijn tekeningen en schilderijen in hun samenhang en ontwikkeling, 1st ed. (Amsterdam: Meulenhoff International bv, 1977), no. JH688, p. 152, (repro.), as Boer, kop.

Robert H. Terte, “The Phenomenal Nelson Gallery,” Antiques World 1, no. 3 (January 1979): 46.

Paul Aletrino, Tout Van Gogh 1888–1890, trans. Sylvie Desmaison (Paris: Flammarion, 1980), 32, 40, (repro.), as Tète de paysan.

Jan Hulsker, The Complete Van Gogh: Paintings, Drawings, Sketches, 2nd ed. (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1980), no. JH688, p. 152, (repro.), as Peasant, Head.

Vincent van Gogh Exhibition, exh. cat. (Tokyo: Tokyo Shimbun, 1985), 63–64.

Cathy Johnson, “Young at Art: Learning from the Masters,” Artist’s Magazine 3, no. 11 (November 1986): 86, as Head of a Peasant.

Peter C. Sutton, A Guide to Dutch Art in America (Washington, DC: Netherlands-American Amity Trust; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1986), 122, 127.

“Museums to Sports, KC Has It All,” American Water Works Association Journal 79, no. 4 (April 1987): 133.

Marc S. Gerstein, Impressionism: Selections from Five American Museums, exh. cat. (New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1989), 20.

Jan Hulsker, Van Gogh en zijn weg: Het complete werk, 6th ed., rev. and expanded (Amsterdam: Meulenhoff Nederland bv, 1989), no. JH688, p. 152, (repro.), as Boer, kop.

Geoffrey J. Warner, A Submission of Observations on Vincent van Gogh: His Paintings and His Drawings, a new perspective (Salisbury, Wiltshire, England: Geoffrey J. Warner, 1989–1990), 1:51–52, 2:unpaginated, 3:446, as Portrait of a Peasant.

Giovanni Testori and Luisa Arrigoni, Van Gogh: catalogo completo dei dipinti (Firenze: Cantini, 1990), 58, (repro.), as Contadion, busto, con berretto, visto di fronte.

Teio Meedendorp, Drawings and prints by Vincent van Gogh in the collection of the Kröller-Müller Museum (Delft, The Netherlands: Thieme GrafiMedia Groep, 2007), 274, as Head of a man.

Ingo F. Walther and Rainer Metzger, Vincent van Gogh: The Complete Paintings, part 1 (1990; repr., Cologne: Taschen GmbH, 2012), 89, (repro.), as Head of Young Peasant in a Peaked Cap.

Alice Thorson, “The Nelson Celebrates its 60th: Museum built its reputation, collection virtually ‘from scratch,’” Kansas City Star 113, no. 304 (July 18, 1993): J4.

Michael Churchman and Scott Erbes, High Ideals and Aspirations: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1933–1993 (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1993), 53, as Portrait of Gysbertus [sic] de Groot.

Bernard Denvir, The Chronicle of Impressionism: An Intimate Diary of the Lives and World of the Great Artists (London: Thames and Hudson, 1993), 279.

Jan Hulsker, Vincent Van Gogh: A Guide to His Work and Letters (Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum, 1993), 74.

Possibly Louis van Tilborgh, The Potato Eaters by Vincent Van Gogh, exh. cat., Cahier Vincent 5 (Zwolle, The Netherlands: Waanders, 1993), 103.

“Music Teachers National Association National Convention, March 23–27, 1996, Kansas City, Missouri,” American Music Teacher 45, no. 4 (February–March 1996): 23.

Jan Hulsker, The New Complete Van Gogh: Paintings, Drawings, Sketches; Revised and Enlarged Edition of the Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of Vincent Van Gogh, rev. ed. (Amsterdam: J. M. Meulenhoff, 1996), no. JH688, pp. 152, 154, 156, (repro.), as Peasant, Head.

Marije Vellekoop and Sjraar van Heugten, Vincent van Gogh Drawings, trans. Michael Hoyle (Amsterdam: van Gogh Museum, 2001), 3:60n8.

“Vincent Van Gogh: Honor Anniversary of Modern Master’s Life and Art with a Visit to the Nelson-Akins,” Newsletter (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (March 2003): 8, as Portrait of Gysbertus [sic] de Groot.

Judit Geskó, ed., Van Gogh in Budapest, exh. cat. (Budapest: Museum of Fine Arts, 2006), 277.

Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 15-16, as Portrait of Gysbertus [sic] de Groot.

Deborah Emont Scott, ed., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collection, 7th ed. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2008), 124, (repro.), as Portrait of Gysbertus [sic] de Groot.