![]()

Camille Pissarro, The Garden of Les Mathurins at Pontoise, 1876

| Artist | Camille Pissarro, French, 1830–1903 |

| Title | The Garden of Les Mathurins at Pontoise |

| Object Date | 1876 |

| Alternate and Variant Titles | Jardin des Mathurins, à Pontoise |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (Unframed) | 44 5/8 x 65 1/8 in. (113.4 x 165.4 cm) |

| Signature | Signed and dated lower right: C. Pissarro. 1876 |

| Credit Line | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 60-38 |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

André Dombrowski, “Camille Pissarro, The Garden of Les Mathurins at Pontoise, 1876,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.642.5407.

MLA:

Dombrowski, André. “Camille Pissarro, The Garden of Les Mathurins at Pontoise, 1876,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.642.5407.

Fig. 2. Camille Pissarro, The Garden of Les Mathurins at Pontoise, 1876, detail of the left side

Fig. 2. Camille Pissarro, The Garden of Les Mathurins at Pontoise, 1876, detail of the left side

Fig. 3. Camille Pissarro, The Garden at Les Mathurins, Pontoise, detail of a page in the artist’s sketchbook, ca. 1877, ink and pencil on paper, Wildenstein Plattner Institute, Inc., New York

Fig. 3. Camille Pissarro, The Garden at Les Mathurins, Pontoise, detail of a page in the artist’s sketchbook, ca. 1877, ink and pencil on paper, Wildenstein Plattner Institute, Inc., New York

The resulting painting, however, is far from a simple paean to bourgeois culture and SalonSalon, the: Exhibitions organized by the French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture (Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture) and its successor the Academy of Fine Arts (Académie des Beaux Arts), which took place in Paris from 1667 onward.-style formats. An Impressionist through and through, Pissarro calibrated format, composition, and content carefully; light filters dramatically throughout the garden, and the bright coloration is surprising, even jarring at times. For all the beauty of the Mathurins garden, it was also publicly known to be a profoundly activist space, a fact that Pissarro emphasized when putting the site’s name as the painting’s title in the catalogue for the 1877 Impressionist exhibition: Jardin des Mathurins, à Pontoise. The garden was the meeting place, and spatial extension, of Deraismes’s own political ideas and ideals. Specifically, it was a stage for several feminist gatherings at the time, when they had been banned by the early Third Republic’sThird Republic: The republic established in France in 1870, after the fall of Napoleon III, lasting until the German occupation of France in World War II. rather conservative government. The painting allowed Pissarro to devise an artifact that spoke to the kind of clientele he sought to attract, all the while keeping his commitment to sociopolitical content alive.

Painted and exhibited, in part, to open new audiences for Pissarro’s work, The Garden of Les Mathurins at Pontoise reflected a series of strategies Pissarro devised to sell more pictures.11For a slightly later instance within Pissarro’s oeuvre, the making of Two Young Peasant Women of 1891–92, T. J. Clark has spoken of a similar “moment of abandonment of previous avant-garde commitments, and rueful accommodation to the market.” T. J. Clark, “Time and Work-Discipline in Pissarro,” in Work and the Image I: Work, Craft, and Labour—Visual Representations in Changing Histories, ed. Valerie Mainz and Griselda Pollock (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2000), 109. In 1877, Pissarro was particularly strapped for cash and often unable to pay his rent, to an extent that his creditors threatened the confiscation of his paintings until Caillebotte helped by buying a group of them. Later that same year, the Impressionists, including Pissarro, offered their work for sale at the Drouot auction house with little success, and they also organized a raffle in November, in which some of Pissarro’s paintings could be had for the price of a lottery ticket.12See Alexia de Buffévent, “A Painter and His Age: Biography and Critical Reception,” in Pissarro and Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Critical Catalogue of Paintings, 1:155–56. The ambition of the Mathurins garden scenes comes into clearer view given these circumstances. Perhaps Pissarro hoped that Deraismes herself might find the painting to her liking, but there is no trace of it in her collection in the late 1870s. It is not certain how long the painting stayed in Pissarro’s possession after the Impressionist exhibition closed at the end of April 1877, but by 1883, the painting was recorded in the collection of Georges de Bellio, a physician and early collector of Impressionism, who probably bought the picture directly from the artist and whose daughter owned it after his death in 1894 until about 1920.13Marianne Delafond, ed., À l’apogée de l’impressionnisme: La Collection Georges de Bellio, exh. cat. (Lausanne: La Bibliothèque des arts in association with Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris, 2007), 30–31, 70.

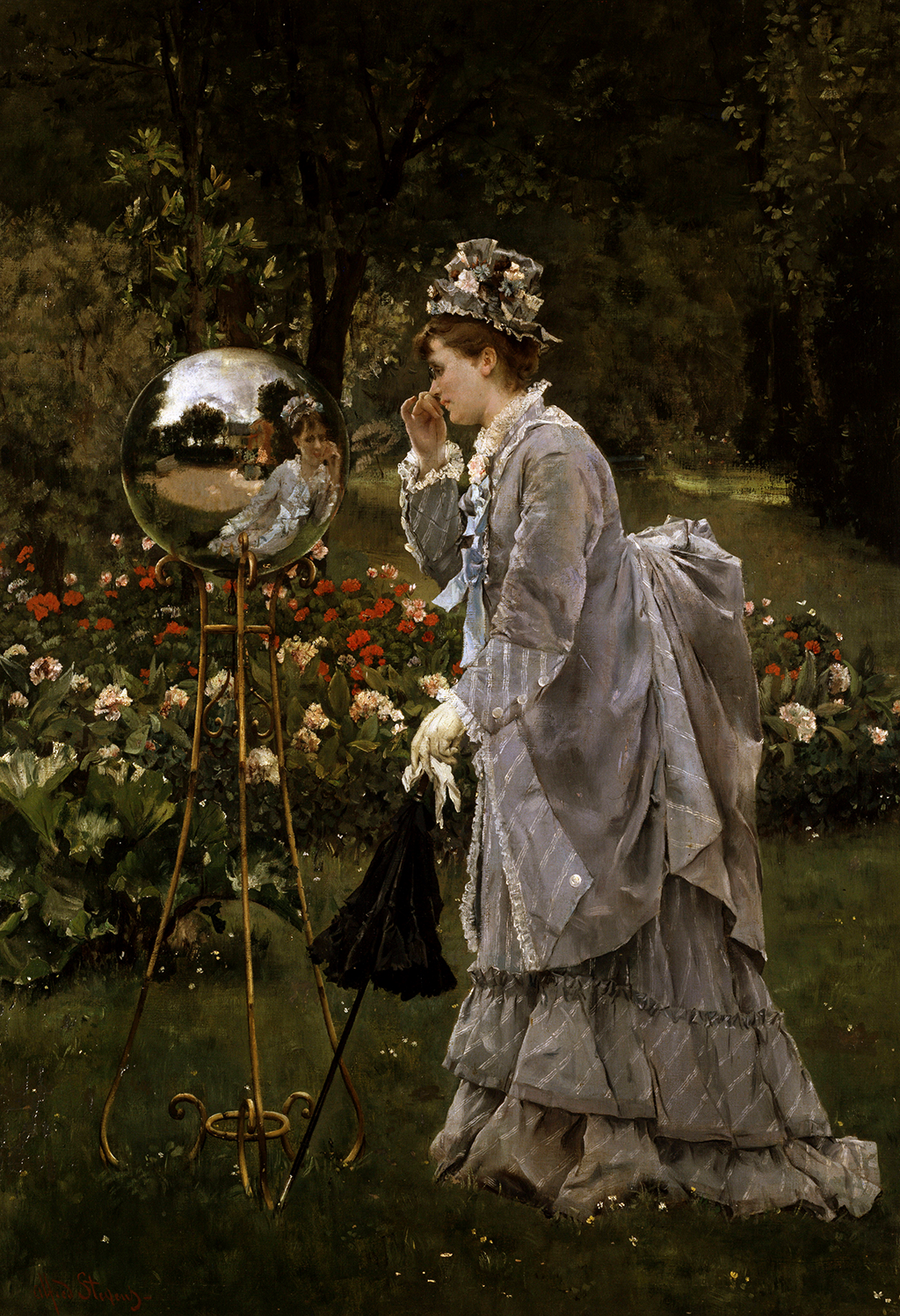

Pissarro painted roughly eight total paintings in or near the gardens of Le Mathurins and exhibited three in 1877, all surely intended to highlight both the site and its owner. The vertical canvas of a similar size to the Nelson-Atkins painting shows the house on the left, hidden behind the tall shrubs and dense garden foliage (Fig. 5). A young woman with a parasol, most likely one of the Deraismes sisters, sits on a bench accompanied by a young child playing.14Two other closely related canvases have survived as well; see Pissarro and Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Critical Catalogue of Paintings, cat. nos. 404 and 504, 2: 299, 356. The third Mathurins painting displayed in 1877 is unidentified today, but it seems it was closer to those versions showing the estate from a distance, of which Pissarro made about four or five (see, for example, Fig. 6).15Such as Pissarro and Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Critical Catalogue of Paintings, cat. nos. 293, 399, 408, and 507, 2: 231, 297, 302, 357. All paintings of the site taken together declare the garden as a feminine space, and themes from the two largest paintings—one woman standing near a gazing globe while reading; another tending to a child—resonated with Deraismes’s intellectual pursuits, centrally focused on the education and societal representation of women.

Throughout her many essays and speeches, Deraismes repeatedly tackled such subjects as “woman in society,” “woman in the novel,” and “woman such as she is,” and her most influential collection of essays bears the title Eve dans l’humanité (Eve in humanity). However, her ideological program is perhaps nowhere better expressed than in the name she gave the feminist organization she founded in April 1870, the Société pour l’amélioration du sort de la femme (Society for the Amelioration of the Female Condition).18Maria Deraismes, Ève dans l’humanité, ed. Laurence Klejman (1868; Paris: Côté-femmes, 1990). Deraismes’s entire oeuvre is collected in Maria Deraismes, Oeuvres complètes de Maria Deraismes, 4 vols. (Paris: Felix Alcan, 1895–98). Deraismes frequently called the “woman ideal” a “political ideal,” making the qualities of women (as she saw them and as her class dictated them to her) the qualities of the modern nation state itself: “She will bring to public life her own beautiful qualities: sagacity, perseverance, abnegation,” she said.19“Elle apportera à la vie publique ses belles qualitées: sagacité, persévérance, abnégation.” Maria Deraismes, “La Femme dans la société nouvelle: Conférence faite à Troyes en 1883,” in Ève dans l’humanité, 194. All translations by the author unless otherwise noted. No republic could survive, she argued, unless women played within it the fullest possible role, even if they did not vote. The arts shaped this “woman ideal” dramatically through images of women they created and placed within the public sphere. Deraismes thus often sparred with the leading artists and writers of her day, exposing the misogyny of playwrights like Victorien Sardou and Alexandre Dumas fils, who claimed emphatically that women were “naturally” inferior to men.20Maris Deraismes, Le Théâtre de M. Sardou: Conférence faite le 21 janvier 1875, à la Salle des Capucines (Paris: E. Dentu, 1875).

Deraismes’s and Pissarro’s artistic and ideological concerns can thus be seen as allied. Her writings highlighted, over and above the demand for explicit political rights, an improvement in women’s image and “representation,” in all social domains, including the theater and the arts.21Maria Deraismes, Ce que veulent les femmes: Articles et conférences de 1869 à 1891, ed. Odile Karkovitch (Paris: Syros, 1980). Knowing well the power of the visual to change the social, she fought her battle in and over the images of women. It is no surprise, then, that Deraismes is present within Pissarro’s painting of her garden—even mirrored within it—in a self-reflexive acknowledgment of the powers of representation. Pissarro found the most literal form of her feminist demands—a woman doubly represented as self and image in the fleeting yet meditative mirror-world of the gazing globe—perfectly in sync with the Impressionist program favoring all things that signaled depth beneath the surface.

The choice of site is an indication of Pissarro’s willingness to associate his art with Deraismes’s reputation. Les Mathurins was indeed synonymous with Deraismes; the letterhead she used in Pontoise named her estate directly, and she even signed several of her publications written in Pontoise with “Maria Deraismes, aux Mathurins à Pontoise, et 52, Avenue de Clichy à Paris.”22Maria Deraismes to Marie Rattazzi, September 28, 1890; and Maria Deraismes to an unknown recipient, July 8, 1879, copies at Bibliothèque Marguerite Durand, Ville de Paris, dossier “Deraismes, Maria,” letters 1 and 2. I thank Brigitte Scarron at the library for her assistance. For Deraismes’s Pontoise/Paris addresses, see listings in her early 1880s journal, Le Républicain de Seine-et-Oise. In 1887, when Paul Alexis catalogued the collection of Eugène Murer, an early supporter and collector of Impressionism, he listed Murer’s Mathurins landscape by Pissarro as “9. Les Mathurins, propriété de Mlle Deraismes, à Pontoise.”23Trublot [Paul Alexis], “La Collection Murer,” Le Cri du peuple, October 21, 1887, 4. When Pissarro placed Les Mathurins in the title of his paintings, he knew what kind of associations he would invite, at the very least from his immediate cohort and Pontoise circle.

As noted above, in the middle years of the 1870s, Deraismes’s estate functioned as a semiofficial meeting-place of the feminist movement. Such political meetings were banned in the Paris of “moral order,” a right-leaning form of republicanism during the first few years of the Third Republic. Between 1873 and 1877, the newly organized French feminist movement had battled the conservative political order more than in previous years, and the advances made under the late Second Empire seemed nearly erased by 1875. Interior Minister Louis Buffet had outlawed all feminist gatherings, as well as those of other political groups, so the garden in Pontoise surreptitiously became a meeting place for the movement.24As Patrick Kay Bidelman explains in his study on the early feminist movement in France: “Faced with monarchist Premier de Broglie’s prohibition of public assembly, Deraismes had turned her beautiful Pontoise property of Mathurins into a campaign headquarters. There, recorded one of her colleagues, . . . ‘often several hundred came; during those days, the salon was too small and they trampled on the prohibition of M. de Broglie and on the flowers in the garden.’” Bidelman, Pariahs Stand Up!, 83. Suggesting the semipublic character of the garden, Deraismes holds a sheet of paper in her hand and reads to herself in front of the globe, as if preparing public remarks. Two empty garden chairs have been pulled up to a table partly blocking the metal stand of the globe, alluding to a future audience—if a small one.

In The Garden of Les Mathurins at Pontoise, Pissarro made visible the manifold pressures that the changing fortunes of women’s rights placed on representations of women, whom Impressionism had tended to depict as more universal and unchanging than they were in actuality.30In 1890, Pissarro continued his pictorial investigation into the condition of women in his series of drawings entitled Turpitudes sociales; see John Hutton, “Camille Pissarro’s Turpitudes Sociales and late Nineteenth-Century French Anarchist Anti-Feminism,” History Workshop Journal 24 (Autumn 1987): 32–61. In these investigations, including the Mathurins garden paintings, Pissarro stands in marked contrast to his contemporaries. Paul Cezanne (1839–1906), for instance, wrote to Émile Zola with typical period misogyny: “Mais il paraîtrait que Mlle de Reismes [sic] de Pontoise ou d’alentour, t’a fort maltraité. Pons, celui de Sainte-Beuve, dirait qu’elle ferait bien de tricoter des bas” (But it appears that Mademoiselle Deraismes, from Pontoise or somewhere around there, maltreated you grossly. Pons, the one out of Sainte-Beuve, would say that she would do well to knit stockings). Paul Cezanne to Émile Zola, February 25, 1880, in Paul Cézanne: Letters, ed. John Rewald (New York: Da Capo, 1995), 186. Despite the bourgeois veneer of the carefully kept gardenscape it depicts, the painting is an artistic exploration, akin to Deraismes’s intellectual concerns, of the vexed, unstable, and evolving nature of modern gendered representation. Such contradictions between form and content are a feature of Impressionism, which so often tied its deconstruction of traditional notions of painting to the more pleasant and comforting aspects of middle-class and leisure life. In making this painting, Pissarro partly reversed this general tendency, and herein lies its import: an elaborate exhibition picture and apparently conciliatory in its formal features, it broaches a quietly radical subject instead.

Notes

-

I thank Aimee Marcereau DeGalan and Meghan L. Gray for sharing their research findings on the painting, and Jonathan D. Katz for his thoughtful suggestions.

On Pissarro in Pontoise, see, among others, Richard R. Brettell, Pissarro and Pontoise: The Painter in a Landscape (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1990), 41–42, where the painting is briefly discussed. Brettell points out that Pissarro avoided painting the city’s larger châteaux throughout his time there and that his depictions of the smaller estate of Les Mathurins are exceptional in this regard.

-

For a discussion of Pissarro’s depictions of roads and paths, see André Dombrowski, “Pissarro’s Roads,” in Camille Pissarro: The Studio of Modernism, ed. Christophe Duvivier and Josef Helfenstein, exh. cat. (Munich: Prestel in association with Kunstmuseum, Basel, 2021), 48–61.

-

On the complex compositional layout of the painting, see Ralph T. Coe, “Camille Pissarro’s Jardin des Mathurins: An Inquiry into Impressionist Composition,” Bulletin (The Nelson Gallery and Atkins Museum) 4, no. 4 (Spring 1963): 1–20, esp. 11–13.

-

Coe, “Camille Pissarro’s Jardin des Mathurins,” 12.

-

Joachim Pissarro, “Camille Pissarro’s Vision of History and Art,” in Joachim Pissarro and Claire Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Critical Catalogue of Paintings, trans. Mark Hutchinson and Michael Taylor (Paris: Wildenstein Institute Publications, 2005), 1:61. See also Brettell, Pissarro and Pontoise, 176.

-

T. J. Clark, “Pissarro’s Humility,” in Duvivier and Helfenstein, Camille Pissarro: The Studio of Modernism, 62–73; and Linda Nochlin, “Camille Pissarro: The Unassuming Eye,” in Studies on Camille Pissarro, ed. Christopher Lloyd (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1986), 1.

-

See Richard R. Brettell, ed., A Day in the Country: Impressionism and the French Landscape, exh. cat. (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1984), 228.

-

It seems as if only one letter between them, from Deraismes to Pissarro, has survived: Maria Deraismes to Camille Pissarro, April 10, 1876, listed in sale Archives de Camille Pissarro, Hôtel Drouot, November 21, 1975, no. 138. See also Simon Kelly and April M. Watson, eds., Impressionist France: Visions of Nation from Le Gray to Monet, exh. cat. (Saint Louis, MO: Saint Louis Art Museum, 2013), 208–10.

-

Richard R. Brettell, “The Third Exhibition 1877: The ‘First’ Exhibition of Impressionist Painters,” in The New Painting: Impressionism, 1874–1886, ed. Charles S. Moffett, exh. cat. (San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1986), 231.

-

See “Exposition des impressionnistes: 6, rue Le Peletier,” La Petite République française 363 (April 10, 1877): 2, reprinted in Ruth Berson, ed., The New Painting: Impressionism 1874–1886, Documentation (San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1996), 1:175–76.

-

For a slightly later instance within Pissarro’s oeuvre, the making of Two Young Peasant Women of 1891–92, T. J. Clark has spoken of a similar “moment of abandonment of previous avant-garde commitments, and rueful accommodation to the market.” T. J. Clark, “Time and Work-Discipline in Pissarro,” in Work and the Image I: Work, Craft, and Labour—Visual Representations in Changing Histories, ed. Valerie Mainz and Griselda Pollock (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2000), 109.

-

See Alexia de Buffévent, “A Painter and His Age: Biography and Critical Reception,” in Pissarro and Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Critical Catalogue of Paintings, 1:155–56.

-

Marianne Delafond, ed., À l’apogée de l’impressionnisme: La Collection Georges de Bellio, exh. cat. (Lausanne: La Bibliothèque des arts in association with Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris, 2007), 30–31, 70.

-

Two other closely related canvases have survived as well; see Pissarro and Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Critical Catalogue of Paintings, cat. nos. 404 and 504, 2:299, 356.

-

Such as Pissarro and Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Critical Catalogue of Paintings, cat. nos. 293, 399, 408, and 507, 2:231, 297, 302, 357.

-

The literature on Deraismes is extensive. Helpful introductions include Patrick Kay Bidelman, Pariahs Stand Up! The Founding of the Liberal Feminist Movement in France, 1858–1889 (Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1982), 75–91; Joyce Dixon-Fyle, Female Writers’ Struggle for Rights and Education for Women in France (1848–1871) (New York: Peter Lang, 2006); and Karen Offen, Debating the Woman Question in the French Third Republic, 1870–1920 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018). The most recent biography is Fabienne Leloup, Maria Deraismes: Riche, féministe, franc-maçonne (Paris: L’Oeil du sphinx, 2022).

-

Norma Broude, “Edgar Degas and French Feminism, ca. 1880: ‘The Young Spartans,’ the Brothel Monotypes, and the Bathers Revisited,” Art Bulletin 70, no. 4 (December 1988): 643–45.

-

Maria Deraismes, Ève dans l’humanité, ed. Laurence Klejman (1868; Paris: Côté-femmes, 1990). Deraismes’s entire oeuvre is collected in Maria Deraismes, Oeuvres complètes de Maria Deraismes, 4 vols. (Paris: Felix Alcan, 1895–98).

-

“Elle apportera à la vie publique ses belles qualitées: sagacité, persévérance, abnégation.” Maria Deraismes, “La Femme dans la société nouvelle: Conférence faite à Troyes en 1883,” in Ève dans l’humanité, 194. All translations by the author unless otherwise noted.

-

Maris Deraismes, Le Théâtre de M. Sardou: Conférence faite le 21 janvier 1875, à la Salle des Capucines (Paris: E. Dentu, 1875).

-

Maria Deraismes, Ce que veulent les femmes: Articles et conférences de 1869 à 1891, ed. Odile Karkovitch (Paris: Syros, 1980).

-

Maria Deraismes to Marie Rattazzi, September 28, 1890; and Maria Deraismes to an unknown recipient, July 8, 1879, copies at Bibliothèque Marguerite Durand, Ville de Paris, dossier “Deraismes, Maria,” letters 1 and 2. I thank Brigitte Scarron at the library for her assistance. For Deraismes’s Pontoise/Paris addresses, see listings in her early 1880s journal, Le Républicain de Seine-et-Oise.

-

Trublot [Paul Alexis], “La Collection Murer,” Le Cri du peuple, October 21, 1887, 4.

-

As Patrick Kay Bidelman explains in his study on the early feminist movement in France: “Faced with monarchist Premier de Broglie’s prohibition of public assembly, Deraismes had turned her beautiful Pontoise property of Mathurins into a campaign headquarters. There, recorded one of her colleagues, . . . ‘often several hundred came; during those days, the salon was too small and they trampled on the prohibition of M. de Broglie and on the flowers in the garden.’” Bidelman, Pariahs Stand Up!, 83.

-

E. D. Lilley has suggested a connection between Pissarro’s depiction of the globe and a scene in Émile Zola’s novel L’Oeuvre that includes a garden with a similar object. E. D. Lilley, “Zola and Pissarro: A Coincidence,” Burlington Magazine 129, no. 1006 (January 1987): 24–25.

-

Saskia de Bodt et al., Alfred Stevens, Brussels 1823–Paris 1906, exh. cat. (Brussels: Mercatorfonds and Royal Museum of Fine Arts of Belgium, 2009), 101; and Jéan Béraud, La Boule de verre (1875; private collection), illustrated in The Spirit of Impressionism, sales cat. (London: Richard Green Galleries, 2006), cat. no. 4.

-

The German industrialist and politician Walther Rathenau, for instance, wrote in 1917: “Die Dinge des Tages vergleichen sich dem Spiegelbild auf einer Glaskugel: im engen Bezirk, dem Auge zunächst, scheinen die Gegenstände deutlich und wirklich; im Umkreis löst sich das Bild in verschwimmende Flächen.” (Daily occurrences can be compared with the mirror image on a glass globe: in the closer area, near the eye, the objects appear clear and real; along the periphery, the image dissolves into blurry expanses.) Walther Rathenau, Zur Mechanik des Geistes (Berlin: S. Fischer, 1917), 11.

-

Maria Deraismes, “L’Art dans la démocratie: Conférence faite le 9 février 1878, au boulevard des Capucines,” L’Avenir des femmes 10, no. 161 (April 7, 1878): 55–58; and 10, no. 162 (May 5, 1878): 70–74.

-

Maria Deraismes, “Les Femmes au Salon,” L’Avenir des femmes 8, no. 140 (July 2, 1876): 101–03; 8, no. 141 (August 6, 1876): 115–17; and 8, no. 142 (September 3, 1876): 132–35. See Broude, “Edgar Degas and French Feminism, ca. 1880,” 643–44; and Albert Boime, “Maria Deraismes and Eva Gonzalès: A Feminist Critique of ‘Une Loge aux Théâtre des Italiens,’” Woman’s Art Journal 15, no. 2 (1994–95): 31–37. See also Anne Higonnet, Berthe Morisot’s Images of Women (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1992); and Sylvie Patry, Nicole R. Myers, et al., Berthe Morisot: Woman Impressionist (New York: Rizzoli Electa, 2018). Broadly speaking, the literature on Impressionism has been more focused on women Impressionist painters than the relationship of the Impressionists to French feminist tradition and thought.

-

In 1890, Pissarro continued his pictorial investigation into the condition of women in his series of drawings entitled Turpitudes sociales; see John Hutton, “Camille Pissarro’s Turpitudes Sociales and late Nineteenth-Century French Anarchist Anti-Feminism,” History Workshop Journal 24 (Autumn 1987): 32–61. In these investigations, including the Mathurins garden paintings, Pissarro stands in marked contrast to his contemporaries. Paul Cezanne (1839–1906), for instance, wrote to Émile Zola with typical period misogyny: “Mais il paraîtrait que Mlle de Reismes [sic] de Pontoise ou d’alentour, t’a fort maltraité. Pons, celui de Sainte-Beuve, dirait qu’elle ferait bien de tricoter des bas” (But it appears that Mademoiselle Deraismes, from Pontoise or somewhere around there, maltreated you grossly. Pons, the one out of Sainte-Beuve, would say that she would do well to knit stockings). Paul Cezanne to Émile Zola, February 25, 1880, in Paul Cézanne: Letters, ed. John Rewald (New York: Da Capo, 1995), 186.

Technical Entry

Technical entry forthcoming.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Camille Pissarro, The Garden of Les Mathurins at Pontoise, 1876,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.642.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Camille Pissarro, The Garden of Les Mathurins at Pontoise, 1876,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.642.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Camille Pissarro, The Garden of Les Mathurins at Pontoise, 1876,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.642.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Camille Pissarro, The Garden of Les Mathurins at Pontoise, 1876,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.642.4033.

Probably purchased from the artist by Dr. Georges de Bellio (né Gheorge Bellu, 1828–1894), Paris, by May 1, 1883–January 26, 1894 [1];

By descent to his daughter, Victorine (née Victorina Bellu, later de Bellio, 1863–1958) and son-in-law, Eugène “Ernest” (1860–1942) Donop de Monchy, Paris, January 26, 1894–possibly at least March 27, 1920 [2];

Paul Henri Ziegler (1874–1968), Paris, by February 1930–at least March 10, 1957 [3];

With André Weil, Geneva, on joint account with Rosenberg and Stiebel, Inc., New York, stock no. 3796, April 27, 1959–May 6, 1960 [4];

Purchased from Weil and Rosenberg and Stiebel by The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1960.

Notes

[1] This painting is referenced in the inventory that was drawn up after de Bellio’s death by his son-in-law, Eugène Donop de Monchy. See “Catalogue des tableaux anciens et modernes, aquarelles, dessins, pastels, miniatures, formant la collection de Mr. E. Donop de Monchy (Ancienne collection Georges de Bellio),” ca. 1894–1897, Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris, Archives, inventory no. 102. For inventory number, see Marianne Delafond, A l’apogées de l’impressionnisme: la collection Georges de Bellio, exh. cat. (Paris: Musée Marmottan Monet, 2007), 70.

[2] Possibly cited in “Expertise des tableaux de la Collection Donop de Monchy,” March 27, 1920, Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris, Archives.

[3] Ziegler lent this painting to the Centenaire de la naissance de Camille Pissarro exhibition at the Musée de L’Orangerie, Paris, February–March 1930. It was on was on exhibition at Camille Pissarro, 1830–1903, Kunstmuseum Bern, from January 19 to March 10, 1957, and, according to the exhibition catalogue, it was lent by the Automobile-Club de France, Paris. Emmanuel Piat, Head of History and Historical Heritage of the Automobile-Club de France (ACF), is unable to confirm the presence of this work in their collection. However, Paul H. Ziegler was an ACF committee member and in the late 1950s often lent artwork to adorn the offices and salons of the ACF. Therefore, it is possible that the Pissarro painting was still owned by Ziegler and was kept in the ACF lounges until January 1957, when it was sent to the Bern Exhibition. See correspondence from Emmanuel Piat, Responsable Histoire et Patrimoine Historique de l’Automobile—Club de France, to Danielle Hampton Cullen, NAMA, July 2, 2021, NAMA curatorial files.

[4] Frick Art Reference Library, New York, MS.065 Rosenberg and Stiebel Archive, Sales and Inventory Records, Card Files, no. 3796; copy in NAMA curatorial files. The painting was sent on approval to the museum on April 7, 1960. See letter from Coe to Rosenberg and Stiebel, April 7, 1960, NAMA curatorial files. It was placed on view in the Impressionist Gallery at The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art pending its purchase. See “Minutes of April 15, 1960,” April 15, 1960, NAMA Archives, Board of Trustee Minutes 1926–present. The painting was not purchased by the museum until May 6, 1960.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Camille Pissarro, The Garden of Les Mathurins at Pontoise, 1876,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.642.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Camille Pissarro, The Garden of Les Mathurins at Pontoise, 1876,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.642.4033.

Camille Pissarro, Child with a Mechanical Hobby Horse, 1875, oil on canvas, 21 5/8 x 18 1/8 in. (55 x 46 cm), private collection, illustrated in Joachim Pissarro and Claire Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Catalogue critique des peintures; Critical Catalogue of Paintings (New York: Wildenstein Institute Publications, 2005), no. 404, p. 2:299.

Camille Pissarro, A Corner of the Garden at Les Mathurins, 1877, oil on canvas, 21 5/8 x 18 1/8 in. (55 x 46 cm), Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

Camille Pissarro, In the Garden at Les Mathurins, Pontoise, 1877, oil on canvas, 65 x 49 1/4 in. (165 x 125 cm), private collection, illustrated in Nils Büttner and Dorian Astor, Jardins en peinture (Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 2008), 146.

Preparatory Work

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Camille Pissarro, The Garden of Les Mathurins at Pontoise, 1876,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.642.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Camille Pissarro, The Garden of Les Mathurins at Pontoise, 1876,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.642.4033.

Camille Pissarro, The Garden of Mathurins, ca. 1877, ink and pencil on paper, dimensions unknown, Wildenstein Archives, Paris.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Camille Pissarro, The Garden of Les Mathurins at Pontoise, 1876,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.642.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Camille Pissarro, The Garden of Les Mathurins at Pontoise, 1876,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.642.4033.

Troisième Exposition des Peintres Impressionnistes, Rue Le Peletier, Paris, April 1877, no. 166, as Jardin des Mathurins, à Pontoise.

Œuvres de C. Pissarro, Galerie Durand-Ruel, Paris, May 1–25, 1883, no. 20.

Centenaire de la naissance de Camille Pissarro, Musée de L’Orangerie, Paris, February–March 1930, no. 119, as Jardin avec une femme.

Exposition Pissarro, Galerie André Weil, Paris, June 1–27, 1950, no. 12, as Le Jardin des Mathurins, Pontoise.

Exposition Camille Pissarro, Galeries Durand-Ruel, Paris, June 26–September 14, 1956, no. 29, as Le Jardin des Mathurins, Pontoise.

Camille Pissarro, 1830–1903, Kunstmuseum Bern, January 19–March 10, 1957, no. 43, as Le jardin des Mathurins, Pontoise.

C. Pissarro: Loan Exhibition For the Benefit of Recording for the Blind, Wildenstein, New York, March 25–May 1, 1965, no. 33, as Le Jardin des Mathurins, Pontoise.

Pissarro: Camille Pissarro, 1830–1903, Hayward Gallery, London, October 30, 1980–January 11, 1981; Grand Palais, Paris, January 30–April 27, 1981; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, May 19–August 9, 1981, no. 44, as Le jardin des Mathurins, Pontoise, propriété des Dames Desraimes.

The New Painting: Impressionism, 1874–1886, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, January 17–April, 6, 1986; The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, April 19–July 6, 1986, no. 58, as Jardin des Mathurins.

Impressionism: Selections from Five American Museums, The Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, November 4–December 31, 1989; The Minneapolis Institute of Arts, January 27–March 25, 1990; The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, March 21–June 17, 1990; The Saint Louis Art Museum, July 14–September 9, 1990; The Toledo Museum of Art, September 30–November 25, 1990, no. 62, as Garden of Les Mathurins at Pontoise.

À l’Apogée de l’Impressionnisme: la Collection Georges de Bellio, Musée Marmottan-Monet, Paris, October 10, 2007–February 3, 2008, no. 27, as Le Jardin des Mathurins.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Camille Pissarro, The Garden of Les Mathurins at Pontoise, 1876,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.642.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Camille Pissarro, The Garden of Les Mathurins at Pontoise, 1876,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.642.4033.

Catalogue de la 3e exposition de peinture, exh. cat. (Paris: Rue Le Peletier, 1877), unpaginated [repr., in Theodore Reff, ed., Modern Art in Paris: Two-Hundred Catalogues of the Major Exhibitions Reproduced in Facsimile in Forty-Seven Volumes, vol. 23, Impressionist Group Exhibitions (New York: Garland, 1981), unpaginated], as Jardin des Mathurins, à Pontoise.

Possibly “L’Exposition des Impressionnistes,” L’Événement (April 6, 1877): 2.

Possibly (Ch.) Flor O’Squarr, “Les Impressionnistes,” Courrier de France (April 6, 1877): 2.

Georges Rivière, “L’Exposition des Impressionnistes,” L’Impressionniste Journal d’art, no. 1 (April 6, 1877): 2.

Alexandre Pothey, “Beaux–Arts,” Le Petit Parisien, no. 173 (April 7, 1877): unpaginated.

Possibly Georges Lafenestre, “Le Jour et la nuit,” Le Moniteur universel, no. 96 (April 8, 1877): 486, as Le Jardin des Mathurins.

Possibly Bertall, “Exposition des Impressionnistes,” Paris–Journal (April 9, 1877): I-2.

Léon de Lora, “L’Exposition des Impressionnistes,” Le Gaulois, no. 3094 (April 10, 1877): 2.

“Exposition des Impressionnistes,” La Petite République Française, no. 363 (April 10, 1877): 2, as Jardin des Mathurins à Pontoise.

Possibly R. Ballu, “L’Exposition des Peintres Impressionnistes,” Les Beaux-Arts Illustrés (April 23, 1877): 392.

Jacques Mauny, “Thousands of Paintings on View in Paris,” New York Times 70, no. 26,363 (March 30, 1930): 13.

Centenaire de la naissance de Camille Pissarro, exh. cat. (Paris: Musée de L’Orangerie, 1930), unpaginated, as Jardin avec une femme.

Ludovic Rodo Pissarro and Lionello Venturi, Camille Pissarro: Son Art, Son Œuvre (Paris: Paul Rosenberg, 1939), no. 349, pp. 1:130, 2: unpaginated, (repro.), as Le Jardin des Mathurins, Pontoise.

Lionello Venturi, Les Archives de L’Impressionnisme (Paris: Durand-Ruel, 1939), 261, Jardin des Mathurins, à Pontoise.

Exposition Pissarro, exh. cat. (Paris: Galerie André Weil, 1950), unpaginated, as Le jardin des Mathurins, Pontoise, propriété des Desraimes.

Paul Gachet, Deux amis des impressionnistes: le docteur Gachet et Murer (Paris: Musées Nationaux, 1956), 171, as Les Mathurins.

Exposition Camille Pissarro, exh. cat. (Paris: Durand-Ruel Galleries, 1956), unpaginated, as Le jardin des Mathurins, Pontoise, propriété des Dames Desraimes.

Camille Pissarro, 1830–1903, exh. cat. (Bern: Kunstmuseum, 1957), 13, as Le jardin des Mathurin, Pontoise, propriété des Dames Desraimes.

“Calendar, November, 1960: Recent Accession,” Gallery Events (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (November 1960): unpaginated, as Le Jardin des Mathurins, Pontoise.

“Nelson Gallery Benefits from Donors’ Generosity,” *Kansas City Star *80, no. 234 (May 8, 1960): 3A.

“Accessions of American and Canadian Museums,” Art Quarterly, no. 23 (July–September 1960): 400, 415, (repro.), as Le Jardin des Mathurins.

Jan Dickerson, “Impressionist Art Purchase Shown at Gallery,” Kansas City Star 81, no. 50 (November 6, 1960): 1F, (repro.), as Les Jardin des Mathurins.

Bill Graves, “Pissarro: Dean of Impressionist Painters,” Kansas City Times 123, no. 294 (December 8, 1960): 10D, as Le Jardin des Mathurins, Pontoise and Les Jardin des Mathurins.

Ralph T. Coe, “Camille Pissarro’s Jardin des Mathurins: An Inquiry into Impressionist Composition,” Bulletin (The Nelson Gallery and Atkins Museum) 4, no. 4 (Spring 1963): 1–22, (repro.), as Jardin des Mathurins.

Remus Niculescu, “Georges de Bellio, l’ami des impressionnistes,” Revue roumaine d’histoire de l’art, no. 2 (1964): 241, 265, [repr., in Remus Niculescu, Georges de Bellio: l’Ami des impressionnistes (Paris: Editions de l’Académie de la république populaire roumaine, 1970), 17, 71–72], as Jardin des Mathurins.

Ralph T. Coe, “A Curator tells the ‘Why’ of Gallery Purchases,” Kansas City Star 85, no. 318 (August 1, 1965): 1D, (repro.), as Le Jardin des Mathurins.

C. Pissarro: Loan Exhibition For the Benefit of Recording for the Blind, Inc., exh. cat. (New York: Wildenstein, 1965), unpaginated, as Le Jardin des Mathurins, Pontoise.

Jarrold Lanes, “Current and Forthcoming Exhibitions,” Burlington Magazine 107, no. 746 (May 1965): 275–76, (repro.), as Le Jardins des Mathurins, Pontoise.

Rosalind K. Ellingworth, “Art and Ages Reborn for Students on Tours at Gallery,” Kansas City Times 101, no. 208 (May 8, 1969): 3B, (repro.).

Ellen Goheen, “From Romanticism to Pop,” Apollo, no. 130 (December 1972): 543, (repro.), [repr., in Denys Sutton, ed., William Rockhill Nelson Gallery, Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Kansas City (London: Apollo Magazine, 1972), 75], as Le Jardin des Mathurins.

Ross E. Taggart and George L. McKenna, eds., Handbook of the Collections in The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Kansas City, Missouri, vol. 1, Art of the Occident, 5th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1973), 163, 258, (repro.), as Le Jardin des Mathurins, Pontoise.

Janine Bailly-Herzberg ed., Correspondance de Camille Pissarro (Paris: Editions du Valhermeil, 1980), 1:323, as Jardin des Mathurins.

John Rewald et al., Pissarro: Camille Pissarro, 1830–1903, exh. cat. (London: Arts Council of Great Britain, 1980), 28, 30, 108–09, (repro.), as Le jardin des Mathurins, Pontoise, propriété des Dames Desraimes.

John Russell Taylor, “Pissarro reveals versatility as well as consistency,” Times (London), no. 60,767 (November 4, 1980): 8, as The Garden of the Mathurins.

Christopher Lloyd, Camille Pissarro (Geneva: Skira, 1981), 103, 146, (repro.), as The Garden of the Mathurins, Pontoise.

Sophie Monneret, L’Impressionnisme et son Époque (Paris: Éditions Denoël, 1981), 1:68, 3:151, as Jardin des Mathurins, à Pontoise.

Andrea P. A. Belloli, ed., A Day in the Country: Impressionism and the French Landscape, exh. cat. (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1984), 228, as Garden of the Mathurins, Pontoise.

“Education Insights: Lunch Break. The Impressionist Landscape,” Calendar of Events (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (June 1985): unpaginated, as Le Jardin des Mathurins, Pontoise.

Charles S. Moffett, The New Painting: Impressionism 1874–1886, exh. cat. (Geneva: Richard Burton SA, 1986), 206, 231, (repro.), as Jardin des Mathurins.

Laura Rollins Hockaday, “Snow, Art on Exhibit in Capitol,” Kansas City Star 106, no. 127 (February 16, 1986): 8F, as Garden of Les Mathurins at Pontoise.

Donald Hoffmann, “Excitement in the Revolution Again: ‘New Painting’ is a fresh breath of impressionism,” Kansas City Star 106, no. 133 (February 23, 1986): 6D, (repro.), as Garden of Les Mathurins at Pontoise.

Mark M. Johnson, “The New Painting: ‘Impressionism 1874–1886,’” Arts and Activities 99, no. 2 (March 1986): 29, (repro.), as Jardin des Mathurins.

Bruce Bernard, ed., The Impressionist Revolution (London: Orbis, 1986), 104–05, 269, (repro.), as The Garden of Les Mathurins.

Christopher Lloyd, ed., Studies on Camille Pissarro (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1986), 18, as Le Jardin des Mathurins.

E. D. Lilley, “Zola and Pissarro: a Coincidence,” Burlington Magazine 129, no. 1006 (January 1987): 24–25, as Jardin des Mathurins, à Pontoise.

Ellen R. Goheen, The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1988), 102–03, as Le Jardin de Mathurins.

Janine Bailly-Herzberg, ed., Correspondance de Camille Pissarro (Paris: Editions du Valhermeil, 1988), 3:323, Jardin de Mlle Deraismes.

Marc S. Gerstein, Impressionism: Selections from Five American Museums, exh. cat. (New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1989), 12, 146–47, (repro), as The Garden of Les Mathurins at Pontoise.

David Lewis, “Museum Impressions,” Carnegie Magazine 59, no. 12 (November–December 1989): 46, as The Garden of Les Mathurins at Pontoise.

Toni Wood, “The Impressionists broke all the rules: Modern viewers love impressionism,” Kansas City Star 110, no. 184 (April 15, 1990): H4, as Gardens of Les Mathurins at Pontoise.

Toni Wood, “Expatriate paintings in Midwest: Works took diverse routes to exhibit,” Kansas City Star 110, no. 233 (June 3, 1990): G5, as The Garden of the Les Mathurins.

Ludovico Rodo Pissarro and Lionello Venturi, Camille Pissarro, Son Art—Son Œuvre, 2nd rev. ed. (San Francisco: Alan Wofsy Fine Arts, 1989), no. 349, pp. 1:130; 2: unpaginated, (repro.), as Le Jardin des Mathurins, Pontoise.

Judith Bumpus, Impressionist Gardens (Oxford: Phaidon Press Limited, 1990), unpaginated. (repro.), as Garden of Les Mathurins, Pontoise.

Richard R. Brettell, Pissarro and Pontoise: The Painter in a Landscape (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990), 41–42, 173–76, (repro.), as Les Jardin des Mathurins, Pontoise.

Anne Distel, Impressionism: The First Collectors, trans. Barbara Perroud-Benson (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1990), 121, as Garden of Les Mathurins at Pontoise.

Michael Howard, The Impressionists by Themselves, exh. cat. (London: Conran Octopus, 1991), unpaginated, as Garden of Les Mathurins at Pontoise.

Stuart Wreke and William Howard Adams, eds., Denatured Visions: Landscape and Culture in the Twentieth Century, exh. cat. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1991), 29, (repro.), as Garden of Les Mathurins at Pontoise.

John Dixon Hunt, Gardens and the Picturesque: Studies in the History of Landscape Architecture (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1992), 256, 258, (repro.), as The Garden Les Mathurins at Pontoise.

Manfred Koch-Hillebrecht, Museen in den USA: Gemälde (Munich: Hirmer Verlag GmbH, 1992), 244, as Garten der Mathurins, Pontoise.

Bernard Denvir, The Chronicle of Impressionism: An Intimate Diary of the Lives and World of the Great Artists (London: Thames and Hudson, 1993), 279.

Roger Ward and Patricia J. Fidler, eds., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collection (New York: Hudson Hills Press, in association with Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1993), 207, (repro.), as The Garden of Les Mathurins at Pontoise.

Manuel Jover, “Cezanne and Pissarro: Painting in the Open Air,” in “The Painters at Auvers,” special issue, Beaux Arts (1994): unpaginated, (repro.), as Garden of the Mathurins at Pontoise.

Lauren S. Seifert, “On the Use of Concept Formation Tasks to Educate Naive Observers About the Visual Arts,” Visual Arts Research 22, no. 1 (Spring 1996): 18, as The Garden of Les Mathurins at Pontoise.

Ruth Berson, The New Painting, Impressionism, 1874–1886 (San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1996), no. III-166, pp. 1:120, 132, 169, 176; 2:80, 99, (repro.), as Jardin des Mathurins.

Michael Howard, Impressionism (London: Carlton Books, 1997), 158, (repro.), as Garden at Les Mathurins at Pontoise.

Richard L. Mallonee, “Applying Multiple Intelligence Theory in the Music Classroom,” Choral Journal 38, no. 8 (March 1998): 39, 41n11, as The Garden at Les Mathurins at Pontoise.

Richard R. Brettell, “John G. Hutton, ‘Neo-Impressionism and the Search for Solid Ground: Art, Science, and Anarchism in Fin-de-siècle France;’ Martha Ward, ‘Pissarro, Neo-Impressionism, and the Spaces of the Avant-Garde,’” Art Bulletin, no. 1 (March 1, 1999): 169, 175, as La jardin des Mathurins.

Impressionism (New York: Todtri, 2001), 216, as Garden of the Mathurins at Pontoise.

“Vincent Van Gogh: Honor Anniversary of Modern Master’s Life and Art with a Visit to the Nelson-Akins,” Newsletter (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (March 2003): unpaginated, (repro.), as The Garden of Les Mathurins.

Norio Shimada, The History of Impressionism, exh. cat. (Tokyo: Shōgakukan, 2004), 150, (repro.).

Clare Willsdon, In the Gardens of Impressionism (New York: Vendome Press, 2004), 140–41, 147, (repro.), as The Garden of the Mathurins, Pontoise.

Richard R. Brettell and Anne-Birgitte Fonsmark, Gauguin and Impressionism, exh. cat. (Fort Worth, TX: Kimbell Art Museum, 2005), 212, (repro.), as The Garden of Les Mathurins at Pontoise.

Joachim Pissarro and Claire Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Catalogue critique des peintures; Critical Catalogue of Paintings (New York: Wildenstein Institute Publications, 2005), no. 448, pp. 1:362, 376, 387, 390–91, 396, 406, 409, 413; 2:324–25, (repro.), as Le Jardin des Mathurins.

Stephane Guegan, “Cézanne, Pissarro, 1865–1885,” Beaux-Arts Magazine (2006): 52–54, (repro.), as Le Jardin des Mathurins.

Marianne Delafond, À l’apogée de l’impressionnisme: la Collection Georges de Bellio, exh. cat. (Paris: Musée Marmottan Monet, 2007), 27, 30–31, 70, (repro.), as Le Jardin des Mathurins, Pontoise.

Deborah Emont Scott, ed., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collection, 7th ed. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2008), 119, (repro.), as The Garden of Les Mathurins at Pontoise.

“‘The Garden of les Mathurins at Pontoise’ by Camille Pissarro,” Kansas City Star (July 9, 2010): MG5.

Suzanne P. Cole, “Eye Level: A Garden Sojourn with a Woman of Distinction,” Kansas City Star Magazine, supplement, Kansas City Star 130, no. 304 (July 18, 2010): S5, (repro.), as The Garden of les Mathurins at Pontoise.

Clare Willsdon, Impressionist Gardens, exh. cat. (Edinburgh: National Galleries of Scotland, 2010), 162n3, as Le Jardin des Mathurins, Pontoise, propriété des dames Deraismes.

Claire Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: patriarche des impressionnistes (Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 2012), 40, (repro.), Le Jardin des Mathurins.

Simon R. Kelly and April M. Watson, Impressionist France: Visions of Nation from Le Gray to Monet, exh. cat. (St. Louis: Saint Louis Art Museum, 2013), 208, 210, (repro.), as The Garden of Les Mathurins at Pontoise.

Philippe Cros, Pissarro: l’anima dell’impressionismo, exh. cat. (Roma: Rubbettino, 2014), 24, as Il giardino dei Mathurins, a Pontoise.

Marianne Mathieu et al., Impression, soleil levant: l’histoire vraie du chef-d’œuvre de Claude Monet, exh. cat. (Paris: Hazan, 2014), 136, as Le jardin des Mathurins, Pontoise.

Garrett Stewart, “Visualizing Books, Virtualizing Readers,” Yearbook of English Studies 45 (2015): 266–67, as The Garden of Les Mathurins.

Catherine Futter et al., Bloch Galleries: Highlights from the Collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2016), 63, (repro.), as The Garden of Les Mathurins.

Claire Durand-Ruel Snollaerts and Christophe Duvivier, Camille Pissarro: le premier des impressionnistes, exh. cat. (Paris: Éditions Hazan, 2017), 68, 70–71, (repro.), as Garden of Les Mathurins at Pontoise.

Christophe Duvivier, Christophe Duvivier, Pissarro à Pontoise (Cergy-Pontoise, France: Val d’Oise, le département, 2017), 18, (repro.), as Jardin des Mathurins, Pontoise, propriété des dames Deraismes.

advertisement, INK (magazine from The Kansas City Star) (May 3, 2017): (repro.).

Mathias Chivot et al., Côté Jardin, de Monet à Bonnard, exh. cat. (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 2021), 88, (repro.), as Le Jardin des Mathurins, Pontoise, propriété des dames Deraismes.

Christophe Duvivier and Joseph Helfenstein, eds., Camille Pissarro: The Studio of Modernism, exh. cat. (Munich: Prestel, 2021), 189, 317, (repro.), as The Garden at Les Mathurins, Pontoise, Belonging to the Deraismes Sisters.