![]()

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne, ca. 1810–1811

| Artist | Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, French, 1780–1867 |

| Title | Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne |

| Object Date | ca. 1810–1811 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (Unframed) | 18 9/16 x 14 3/8 in. (47.2 x 36.5 cm) |

| Credit Line | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 32-54 |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Kathryn Calley Galitz, “Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne, ca. 1810–1811,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.414.5407.

MLA:

Galitz, Kathryn Calley. “Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne, ca. 1810–1811,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.414.5407.

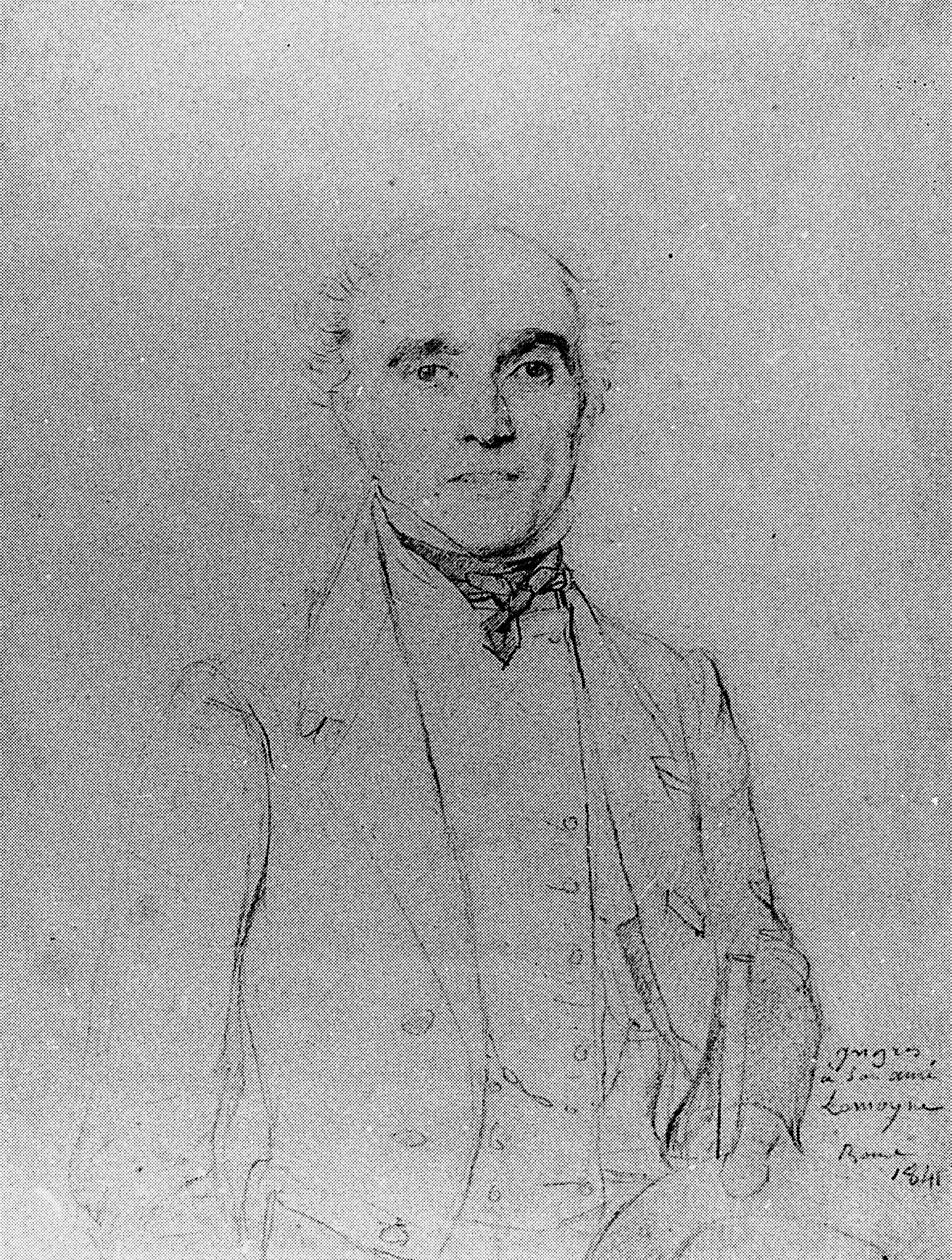

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres painted this startlingly direct portrait of French sculptor Paul Lemoyne (1784–1873) in Rome around 1810, not long after the latter’s arrival in the Italian capital, then a hub for European artists.1On Lemoyne, see Antoinette Le Normand, “Paul Lemoyne, un sculpteur français à Rome au XIXe siècle,” Revue de l’Art, no. 36 (1977): 27–41. Le Normand established the date of Lemoyne’s arrival in Rome, which serves as the basis for the present dating of Ingres’s portrait. See also Hans Naef, Die Bildniszeichnungen von J.-A.-D. Ingres (Bern: Benteli, 1979), 3:301–11. Their paths probably crossed at the Villa Medici, the seat of the French Academy in Rome, which was home to a lively community of artists, writers, and intellectuals. Ingres, who was awarded the prestigious Prix de Rome in history painting in 1801 but deferred his departure from Paris for some five years, arrived in October 1806.

Fig. 2. Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, Portrait of a Man with an Earring, 1804, oil on wood, 17 x 14 in. (43.5 x 35.7 cm), Musée Ingres, Montauban, 74-4-1. Signed and dated, lower left: Moi / Ingres pinxit 1804

Fig. 2. Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, Portrait of a Man with an Earring, 1804, oil on wood, 17 x 14 in. (43.5 x 35.7 cm), Musée Ingres, Montauban, 74-4-1. Signed and dated, lower left: Moi / Ingres pinxit 1804

Fig. 3. Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, Jean Baptiste Desdéban, ca. 1810, oil on canvas, 24 3/4 x 19 1/4 in. (63 x 49 cm), Musée des Beaux-Arts et d’Archéologie, Besançon, 896.1.166

Fig. 3. Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, Jean Baptiste Desdéban, ca. 1810, oil on canvas, 24 3/4 x 19 1/4 in. (63 x 49 cm), Musée des Beaux-Arts et d’Archéologie, Besançon, 896.1.166

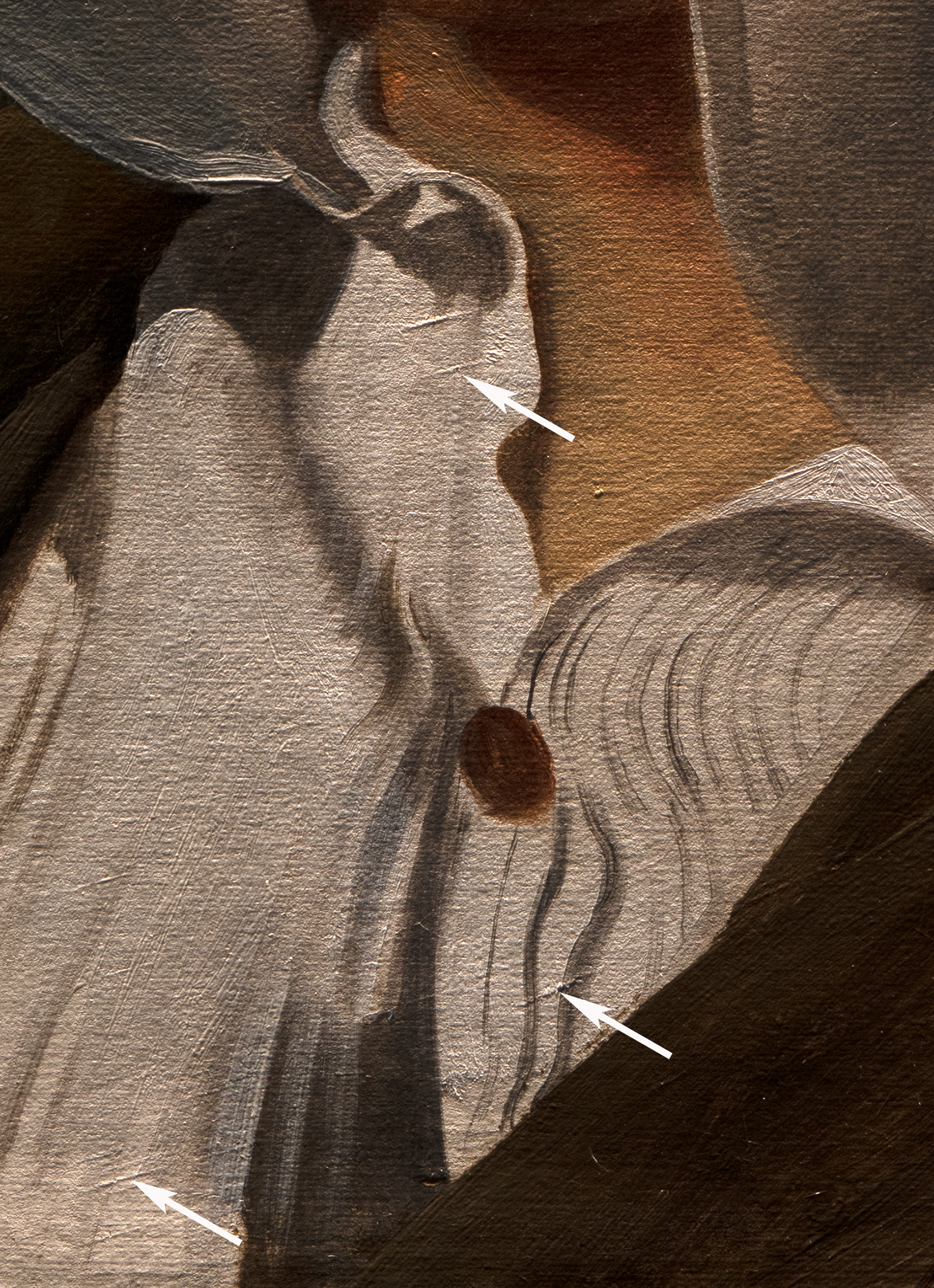

The portrait of Lemoyne is also loosely painted, suggesting that Ingres executed it around the same time as that of Desdéban.7Until recently, this work had been dated to ca. 1817–1819. However, Philip Conisbee convincingly dates it to ca. 1810–1811 in his catalogue entry in Tinterow and Conisbee, Portraits by Ingres, 130–33. In fact, the two paintings appear in consecutive order in a list that Ingres made of his works later in his career.8Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, “Notes de mes ouvrages,” ca. 1847–1850, in Cahiers d’Ingres, cahier 10, folio 23 (private collection, New York). Ingres’s close focus on Lemoyne and the directness of the sitter’s gaze evoke the subject’s psyche in a way that his profile portrait of Desdéban does not. Lemoyne’s heavily shadowed eyes convey an air of brooding intensity that would not be out of place in Romantic portraiture. The presentation of the sitter—his shirt collar carelessly unbuttoned beneath a loosely worn overcoat—and the freely applied paint capture the immediacy of the moment in which it was painted. The scumbledscumble: A thin layer of opaque or semi-opaque paint that partially covers and modifies the underlying paint. handling of the background, a characteristic of David’s portraits from the 1790s, and the seemingly random, unblended brushstrokes on the lapel of his overcoat suggest that the portrait was rapidly executed, directly from life and likely in a single session. Several visible pentimentipentimento (pl: pentimenti): A change to the composition made by the artist that is visible on the paint surface. Often with time, pentimenti become more visible as the upper layers of paint become more transparent with age. Italian for "repentance" or "a change of mind." and the absence of any underdrawingunderdrawing: A drawn or painted sketch beneath the paint layer. The underdrawing can be made from dry materials, such as graphite or charcoal, or wet materials, such as ink or paint. further attest to the spontaneity with which the portrait was rendered. Notably, Ingres enlarged the left collar, as the paint visible beneath its outer edges reveals. He also raised the placement of the sitter’s chin; traces of flesh-colored paint are visible just below his jawline. Ingres left unpainted areas of the opaque white groundground layer: An opaque preparatory layer applied to the support, either commercially or by the artist, to prevent absorption of the paint into the canvas or panel. See also priming layer., particularly evident in the lower portion of his shirt. The black paint used to delineate its pleats was fluidly applied wet-into-wetwet-into-wet: An oil painting technique which involves blending of colors on the picture surface., a technique that Ingres also used to render the highlights and shadows of his neck.9I am indebted to Mary R. Schafer, NAMA paintings conservator, for her technical notes of January 11, 2010, which form the basis of my discussion of Ingres’s technique. As in the portrait of Desdéban, however, the sitter’s face is more carefully painted, with greater attention to modeling and surface finish. These works, both in their informality and their freedom of handling, depart from the detail and polished finish characteristic of Ingres’s commissioned portraits.

Lemoyne, after three failed bids to win the Prix de Rome in sculpture, funded his own trip to Italy in late 1810 and became a regular at the Villa Medici. Along with a number of its pensioners, he was invited to participate in the decoration of the French church of Santissima Trinità dei Monti in Rome; before the project was abandoned in 1822, Lemoyne executed a plaster model of the Virgin and Child (before 1817), and Ingres painted Christ Giving the Keys to Saint Peter as an altarpiece (1820; Musée Ingres, Montauban).

Ingres’s portrait of Lemoyne attests to their friendship during their time in Rome, and the painter presented him with the work sometime before moving to Florence in 1819. Although it is possible that the two exchanged artworks, as was often the practice among the artists in David’s studio, there is no evidence of a gift from Lemoyne to Ingres. Ingres apparently also gave Lemoyne his portrait of their mutual friend, Desdéban. Subsequently, their friendship cooled, which Lemoyne blamed on Ingres’s wife, Madeleine Ingres, as he confided to a fellow artist in 1822: “I’ve definitely broken with him, or rather with his wife. . . . As for Ingres, I admire his talent, but I’d doff my hat more readily to his works than to the man himself.”10Tinterow and Consibee, Portraits by Ingres, 132.

Both the present work as well as Ingres’s portrait of Desdéban figured in the art collection that Lemoyne assembled over the course of some five decades as an expatriate French artist in Rome. At an auction in Paris in 1865, Lemoyne sold his collection, which included four works by Ingres; Lemoyne’s portrait was acquired by another artist, Jean Gigoux (1806–1894). Lemoyne died eight years later, at the age of ninety. In his memoirs, Gigoux later recalled the angry outcry of the eighty-five-year-old Ingres upon hearing that Lemoyne had sold his portrait, which had been his gift to Lemoyne: “The poor man has sold himself!”12“Le malheureux s’est vendu lui-même!”; Jean Gigoux, Causeries sur les artistes de mon temps, 3rd ed. (Paris: Calmann Lévy, 1885), 85.

Notes

-

On Lemoyne, see Antoinette Le Normand, “Paul Lemoyne, un sculpteur français à Rome au XIXe siècle,” Revue de l’Art, no. 36 (1977): 27–41. Le Normand established the date of Lemoyne’s arrival in Rome, which serves as the basis for the present dating of Ingres’s portrait. See also Hans Naef, Die Bildniszeichnungen von J.-A.-D. Ingres (Bern: Benteli, 1979), 3:301–11.

-

“. . . copier une tête, pour laquelle chaque élève était tenu par les règlements de poser lui-même, ou de fournir un modèle mercenaire à ses frais”; E. J. Delécluze, Louis David, Son école et son temps (Paris: Didier, 1855), 53.

-

On this work, see Gary Tinterow and Philip Conisbee, eds., Portraits by Ingres: Image of an Epoch, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1999), no. 1, pp. 44–46.

-

See Vincent Pomarède et al., Ingres, 1780–1867 (Paris: Gallimard, 2006), 131.

-

“Quant à messieurs mes camarades, excepté Granger et Odevaere, qui est doux à vivre, à part ses pretensions, le reste m’est de la dernière indifference.” Pomarède et al., Ingres, 1780–1867, 150.

-

“. . . toujours presque plus forte que la peinture.” Pomarède et al., Ingres, 1780–1867, 150.

-

Until recently, this work had been dated to ca. 1817–1819. However, Philip Conisbee convincingly dates it to ca. 1810–1811 in his catalogue entry in Tinterow and Conisbee, Portraits by Ingres, 130–33.

-

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, “Notes de mes ouvrages,” ca. 1847–1850, in Cahiers d’Ingres, cahier 10, folio 23 (private collection, New York).

-

I am indebted to Mary R. Schafer, NAMA paintings conservator, for her technical notes of January 11, 2010, which form the basis of my discussion of Ingres’s technique.

-

Tinterow and Consibee, Portraits by Ingres, 132.

-

For a discussion of Ingres’s “portraits intimes,” see Uwe Fleckner, Abbild und Abstraktion: Die Kunst des Porträts im Werk von Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (Mainz: Philipp von Zabern, 1995), 113–23, and Christopher Riopelle’s entry in Tinterow and Conisbee, Portraits by Ingres, 327–28.

-

“Le malheureux s’est vendu lui-même!”; Jean Gigoux, Causeries sur les artistes de mon temps, 3rd ed. (Paris: Calmann Lévy, 1885), 85.

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Mary Schafer, “Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne, ca. 1810–1811,” technical entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.414.2088.

MLA:

Schafer, Mary. “Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne, ca. 1810–1811,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.414.2088.

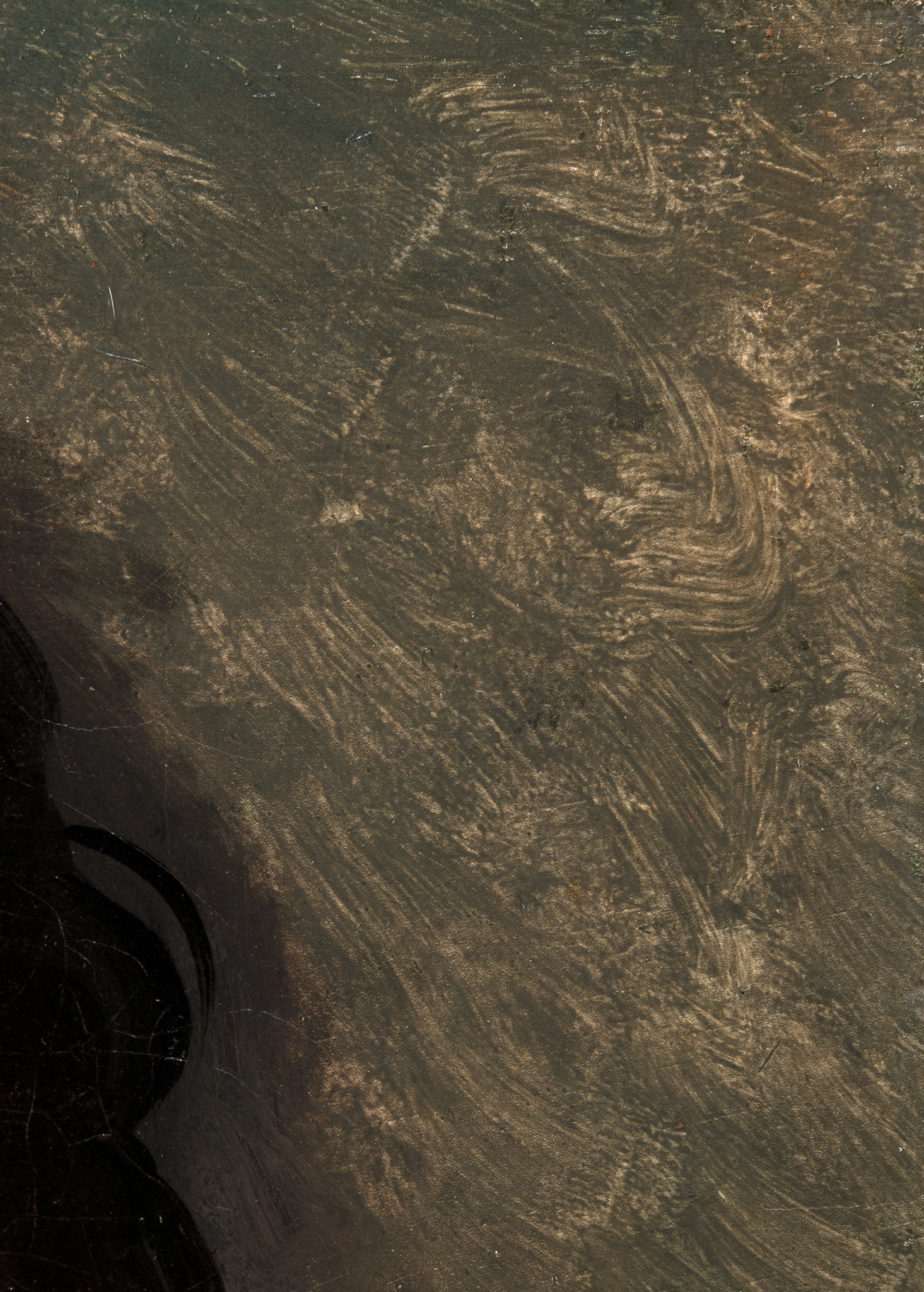

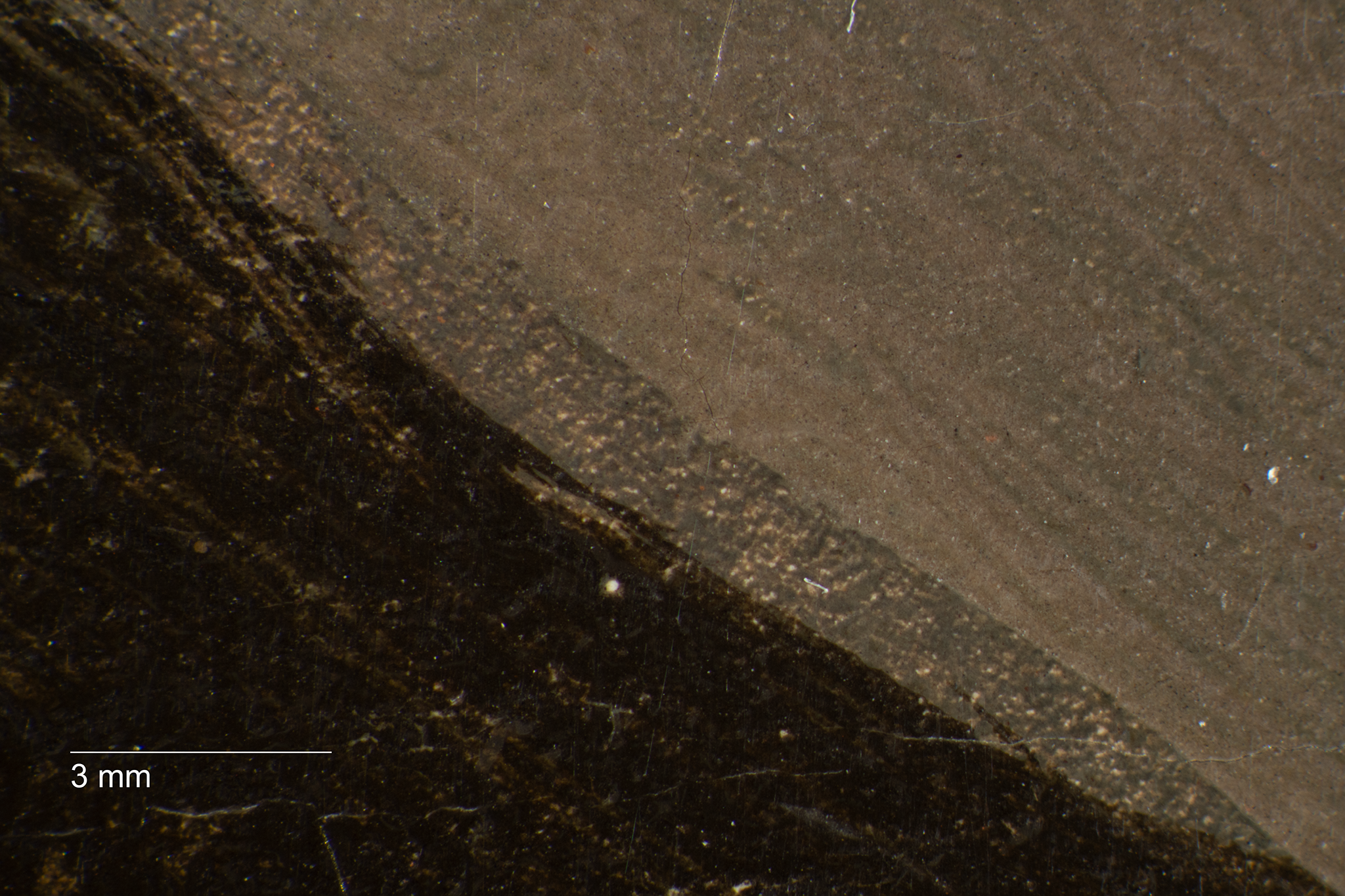

With confident, lively brushwork, Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (1780–1867) executed Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne quickly and likely over the course of a single painting session. Although the painting is glue-linedlining: A procedure used to reinforce a weakened canvas that involves adhering a second fabric support using adhesive, most often a glue-paste mixture, wax, or synthetic adhesive. and its outermost edges are covered by brown paper, x-radiographyX-ray radiography (also referred to as x-radiography or radiography): Radiography is an examination tool analogous to the use of X-rays in medicine whereby denser components of a painted composition can be recorded as an inverted shadow image cast on film or a digital X-ray imaging plate from a source such as an X-ray tube. The method has been used for more than a century and is most effective with dense pigments incorporating metallic elements such as lead or zinc. It can reveal artist changes, underlying compositions, and information concerning the artwork’s construction and condition. The resulting image is called an x-radiograph or radiograph. It differs from the uses of X-ray spectrometry in being dependent on the density of the paint to absorb X-rays before they reach the film or image plate and being non-specific as to which elements are responsible for the resulting shadow image. confirms that the original support is a plain-weaveplain weave: A basic textile weave in which one weft thread alternates over and under the warp threads. Often this structure consists of one thread in each direction, but threads can be doubled (basket weave) or tripled to create more complex plain weave. Plain weave is sometimes called tabby weave. canvas containing numerous slubs and weave irregularities.1See film-based radiograph, no. 46, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, 32-54. The canvas was prepared with an even, off-white groundground layer: An opaque preparatory layer applied to the support, either commercially or by the artist, to prevent absorption of the paint into the canvas or panel. See also priming layer. that exhibits a rough, grainy texture made more pronounced by the artist’s subsequent washeswash: An application of thin paint that has been diluted with solvent. of paint (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Photomicrograph of the white shirt, Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne (ca. 1810–1811), revealing the grainy texture of the ground layer beneath an overlying gray wash

Fig. 5. Photomicrograph of the white shirt, Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne (ca. 1810–1811), revealing the grainy texture of the ground layer beneath an overlying gray wash

Fig. 6. Detail of Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne (ca. 1810–1811) with raking illumination, showing several thick, underlying paint strokes that may have been used to position the figure in the early stages of painting

Fig. 6. Detail of Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne (ca. 1810–1811) with raking illumination, showing several thick, underlying paint strokes that may have been used to position the figure in the early stages of painting

Ingres initially developed the composition with washes of paint in varying warm tonalities, and his sketch-like handling of the portrait allows many of these first applications to be visible and play an integral role in the final painting (Fig. 7). Above these preliminary layers, Ingres further developed the face with thin paint, lightly crisscrossed brushwork, and some wet-over-wetwet-over-wet: An oil painting technique which involves drawing a stroke of one color across the wet paint of another color. blending of colors. While the brushwork of these uppermost layers is noticeable on close examination, the overall effect at a distance is one of subtle transitions and diffuse boundaries.

Fig. 7. Detail of Lemoyne’s face, Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne (ca. 1810–1811), showing numerous washes in the nose, lips, and cheek associated with the initial lay-in of the sitter’s face

Fig. 7. Detail of Lemoyne’s face, Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne (ca. 1810–1811), showing numerous washes in the nose, lips, and cheek associated with the initial lay-in of the sitter’s face

Fig. 8. Detail of Lemoyne’s neck, Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne (ca. 1810–1811)

Fig. 8. Detail of Lemoyne’s neck, Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne (ca. 1810–1811)

Fig. 9. Detail of the upper right background of Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne (ca. 1810–1811), slightly overexposed to show the energetic brushwork associated with the initial lay-in of the background

Fig. 9. Detail of the upper right background of Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne (ca. 1810–1811), slightly overexposed to show the energetic brushwork associated with the initial lay-in of the background

Fig. 10. Detail of the coat lapel, Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne (ca. 1810–1811)

Fig. 10. Detail of the coat lapel, Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne (ca. 1810–1811)

Fig. 11. Photomicrograph of Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne (ca. 1810–1811), showing the dilute strokes that make up the gray pleats of the shirt

Fig. 11. Photomicrograph of Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne (ca. 1810–1811), showing the dilute strokes that make up the gray pleats of the shirt

Fig. 12. Detail of the white shirt in Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne (ca. 1810–1811), showing the large section of exposed ground at the lower left (roughly annotated with dotted lines) and the varied construction of the shirt pleats

Fig. 12. Detail of the white shirt in Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne (ca. 1810–1811), showing the large section of exposed ground at the lower left (roughly annotated with dotted lines) and the varied construction of the shirt pleats

Fig. 13. Photomicrograph of Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne (ca. 1810–1811), revealing three layers: the green wash of the background, the upper gray-green scumble, and the dark brown contour of the sitter’s overcoat

Fig. 13. Photomicrograph of Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne (ca. 1810–1811), revealing three layers: the green wash of the background, the upper gray-green scumble, and the dark brown contour of the sitter’s overcoat

Fig. 14. Photomicrograph of Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne (ca. 1810–1811), showing the finely incised marks drawn through the wet paint to form the curls of the sitter’s sideburns

Fig. 14. Photomicrograph of Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne (ca. 1810–1811), showing the finely incised marks drawn through the wet paint to form the curls of the sitter’s sideburns

Fig. 15. Detail of Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne (ca. 1810–1811), showing the earlier, upright position of the proper right collar

Fig. 15. Detail of Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne (ca. 1810–1811), showing the earlier, upright position of the proper right collar

Fig. 16. Reflected infrared digital photograph of Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne (ca. 1810–1811), showing slight adjustments to the chin, ear, and proper right pupil

Fig. 16. Reflected infrared digital photograph of Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne (ca. 1810–1811), showing slight adjustments to the chin, ear, and proper right pupil

Notes

-

See film-based radiograph, no. 46, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, 32-54.

-

The backgrounds of Torse d’homme (1800; École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, Paris) and Étude d’homme (1808; Musée Granet, Aix-en-Provence) are similarly constructed, and the brushwork of the overcoat lapel on the Nelson-Atkins portrait is comparable to the brushwork found throughout the clothing of Jean-François Gilibert (1804–1805; Musée Ingres, Montauban).

-

Ingres may have used a similar technique in three other portraits. He appears to have scraped into the wet paint to define the jacket of Jean-Baptiste Desdéban (Fig. 3), the floral pattern on the lower right of Jean-Pierre-François Gilbert (1804–1805; Musée Ingres, Montauban), and a few curls of hair on Tête de Boileau (1827; Musée Ingres, Montauban).

-

Scott Heffley, January 5, 1998, treatment report, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, 32-54.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne, ca. 1810–1811,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.414.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne, ca. 1810–1811,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.414.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne, ca. 1810–1811,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.414.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne, ca. 1810–1811,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.414.4033.

Given by the artist to Paul Lemoyne (1783–1873), Rome, before 1819–1865;

Purchased at his sale, Collection de tableaux, esquisses et dessins, composée pour la plus grande partie de souvenirs des grands prix de Rome offerts à M. P. L., résidant à Rome depuis longtemps, Hôtel Drouot, Paris, April 3, 1865, lot 32, as Portrait d’homme P.L., by Jean Gigoux (1806–1894), Paris, April 3, 1865–at least 1888 [1];

Paul-Arthur Chéramy (1840–1912), Paris, by May 5, 1908 [2];

Purchased at his sale, Tableaux anciens et modernes, aquarelles, pastels, dessins, œuvres remarquables de Boltraffio, Chardin, Corot, Courbet, David, Degas, Foppa, Géricault, Goya, Greco, Ingres, Millet (J.-F.), Puvis de Chavannes, Reynolds, Prud’hon, Tassaert, Vinci (atelier de Léonard de), etc.; très importante collection d’œuvres de Constable et d’Eugène Delacroix, primitifs italiens composant le collection P. A. Cheramy, Galerie Georges Petit, Paris, May 5–7, 1908, lot 212, as Portrait du sculpteur Paul Lemoyne (1784–1873), by Henri Haro (1855–1911), Paris, 1908–May 7, 1911;

Purchased at his posthumous sale, Tableaux anciens des écoles primitives et de la Renaissance et des écoles flamande, française, hollandaise et italienne des XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles; œuvres de Backhuisen, B. de Bruyn, Ch. Coypel, Cranach, B. Cuyp, Danloux, Elias, J.-B. Greuze, Baron Gros, Heda, J.-B. Huet, J. Jouvenet, Mme Vigée-Lebrun, Lenain, Leprince, van der Meulen, le Pontormo, P.-P. Prudhon, H. Rigaud, Hubert Robert, Roslin, Santerre, J. Steen, G. Terburg, Tournières, F. de Troy, W. van den Velde, Joseph Vernet, C. de Vos, etc.; tableaux modernes par Cabat, Carolus Duran, Chaplin, E. Delacroix, E. Deveria, Ingres, H. Regnault, Th. Ribot, Roybet, Sisley, F. Thaulow, Verboeckhoven, Horace Vernet, Ziem, etc.; composant la collection de M. Henri Haro, Hôtel Drouot, Paris, December 12–13, 1911, lot 217, as Portrait du sculpteur Paul Lemoyne, by Adrien Fauchier-Magnan (1873–1965), Paris, 1911;

Henry Lapauze (1867–1925), Paris, by May 1914–1925;

Purchased at Lapauze’s posthumous sale, Tableaux et dessins par J.-A.-D. Ingres, composant la collection de Monsieur Henry Lapauze, Hôtel Drouot, Paris, June 29, 1929, lot 54, as Portrait du sculpteur Paul Lemoyne, through Ferdinand Lair-Dubreuil, Paris, by Knoedler and Company, New York, stock number A856, 1929–March 1932 [3];

Purchased from Knoedler by The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1932.

Notes

[1] The latest citation for this portrait being in Gigoux’s possession is: Henry Jouin, Musée de portraits d’artistes, peintres, sculpteurs, architectes, graveurs, musiciens, artistes dramatiques, amateurs, et., nés en France ou y ayant vécu. État de 3000 portraits; Peints, dessinés ou sculptés avec l’indication des collections publiques ou privées qui les renferment (Paris: H. Laurens, 1888), 115. Gigoux bequeathed his collection of paintings to the Musée de Besançon, but an inventory of his collection drawn up by his student and heir Paul Lapret reveals that Gigoux no longer owned Ingres’s Portrait of Paul Lemoyne at the time of his death in 1894. “Musée de Besançon. Dons et legs, ordre chronologique—Legs Jean Gigoux: testament, extraits de délibérations du conseil municipal, catalogue des peintures de la collection Jean Gigoux, inventaire, correspondance (1896–1928),” 2R52, 2R-Sciences, Lettres, et Arts, Archives municipales, Musées et Beaux-arts, Ville de Besançon, France.

[2] This constituent’s surname also appears as “Cheramy” in various publications.

[3] See the inscription, “Lair-Dubreuil, Paris, June 21, 1929/ Henry Lapauze Sale,” in “M. Knoedler and Co. Records, circa 1848–1971,” Knoedler painting stock book 8, A1-A2680, January 1928–November 1943, p. 93, and Series II, Sales book 13, 1927 January–1936 December, p. 229, The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles.

See also letter from Edye Weissler, Librarian and Archivist, Knoedler and Company, to Simon Kelly and Meghan Gray, Nelson-Atkins, May 7, 2010, NAMA curatorial files.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne, ca. 1810–1811,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.414.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne, ca. 1810–1811,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.414.4033.

Tableaux, études peintes, dessins et croquis de J.-A.-D. Ingres, Palais de l’École impériale des beaux-arts, Paris, April 10–May 31, 1867, no. 439, as Lemoyne (M.).

Ingres: exposition organisée au profit du Musée Ingres, Galeries Georges Petit, Paris, April 26–May 14, 1911, no. 24, as Portrait de Paul Lemoyne, sculpteur.

Exposition d’art français du XIXe siècle, Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen, May 15–June 30, 1914, no. 118, as Le Sculpteur Lemoyne.

Cent Ans de Peinture Française: Exposition au Profit de Musée des Beaux-Arts de Strasbourg, Hôtel de la Chambre syndicale de la curiosité et des beaux-arts, Paris, March 15–April 20, 1922, no. 92, as Portrait du sculpteur Lemoyne.

Exhibition of Paintings by Old Masters, Department of Fine Art, Carnegie Institute, Pittsburgh, April 10–30, 1930, no. 23, as Portrait of the Sculptor, Paul Lemoyne.

October Exhibitions: Paintings Lent by M. Knoedler and Company, Chicago; Paintings by Guy Maccoy and Grace Petit; and an Exhibition of Sculpture and Drawings by George Hilbert, The Kansas City Art Institute, MO, October 4–27, 1930, no cat., no. 27, as Port. du Sculpteur, Paul Lemoigne [sic].

Loan Exhibition of French Painting, 1800–1880, City Museum of St. Louis, MO, January 1931, no cat., no. 15, as Portrait of the Sculptor, Paul Lemoyne.

Exhibition of French Painting from the Fifteenth Century to the Present Day, California Palace of the Legion of Honor, San Francisco, June 8–July 8, 1934, no. 114, as Portrait of the Sculptor, Paul Lemoyne.

Forty-Seventh Annual Exhibition of Paintings, Nebraska Art Association, Lincoln, NE, February 28–March 28, 1937, no. 43, as Portrait of Paul Lemoyne.

David and Ingres: Paintings and Drawings, Springfield Museum of Fine Arts, MA, November 20–December 17, 1939; Knoedler and Company, New York, January 8–27, 1940; Cincinnati Art Museum, February 7–March 3, 1940; Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester, NY, March–April 1, 1940, no. 24, as Portrait of the Sculptor, Paul Lemoyne (Springfield and New York only).

Temporary Exhibition, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, December 1941–January 1942, no cat., as Portrait of LeMoyne.

Fashion of the Greeco-Roman [sic] Taste of the Continent and the New Republic, Taft Museum, Cincinnati, OH, October 15–November 30, 1947, unnumbered, as Portrait of the Sculptor, Paul Lemoyne.

French Pre-Impressionist Painters of the Nineteenth Century: Paintings, Watercolors, Drawings, Graphics, Winnipeg Art Gallery, Canada, April 10–May 9, 1954, no. 9, as Portrait of the Sculptor, Paul Lemoyne.

Three Exhibitions: Notable Paintings from Midwestern Collections, Notable Collections at Joslyn Art Museum, Anniversary Purchase Exhibition, Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, NE, November 30, 1956–January 2, 1957, unnumbered, as Portrait of the Sculptor, Paul Lemoyne.

Collectors’ Firsts: A Loan Exhibition Chosen by Art Museum Directors and Owners of Collections in the Atlanta Art Association Galleries, Atlanta Art Association Galleries, February 18–March 1, 1959, no. 26, as Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne.

Ingres in American Collections: Loan Exhibition for the Benefit of the Lighthouse, New York Association for the Blind, Paul Rosenberg and Co., New York, April 7–May 6, 1961, no. 26, as The Sculptor Paul Lemoyne.

Ingres Centennial Exhibition: Drawings, Watercolors, and Oil Sketches from American Collections, Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, February 12–April 9, 1967, no. 48, as Portrait of Paul Lemoyne, Sculptor.

French Nineteenth Century Oil Sketches: David to Degas, William Hayes Ackland Memorial Art Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, March 5–April 18, 1978, no. 43, as Portrait of the Sculptor, Paul Lemoyne.

Ingres, In Pursuit of Perfection: The Art of J. A. D. Ingres, J. B. Speed Art Museum, Louisville, KY, December 6, 1983–January 29, 1984; Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, TX, March 3–May 6, 1984, no. 59, as The Sculptor Paul Lemoyne (Fort Worth only).

Portraits by Ingres: Image of an Epoch, National Gallery, London, January 27–April 25, 1999; National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, May 23–August 22, 1999; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, September 28, 1999–January 2, 2000, no. 29, as Paul Lemoyne.

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres: e la vita artistica al tempo di Napoleone, Palazzo Reale, Milan, March 12–June 23, 2019, no. 62, as Ritratto dello scultore Paul Lemoyne.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne, ca. 1810–1811,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.414.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne, ca. 1810–1811,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.414.4033.

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, “Notes de mes ouvrages,” ca. 1847–1850, private collection, New York, Cahiers d’Ingres, cahier X, folio 23, unpaginated, as Lemoyne.

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, “Liste des tableaux que j’ai peint à Rome,” ca. 1851, Musée Ingres, Montauban, France, Cahiers d’Ingres, cahier IX, folio 124, p. 128, as Lemoyne.

E. Saglio, “Un Nouveau tableau de M. Ingres: Liste complète de ses œuvres,” Le Correspondance littéraire, no. 4 (February 5, 1857): 77.

Catalogue d’une intéressante collection de tableaux, esquisses et dessins, composée pour la plus grande partie de souvenirs des grands prix de Rome offerts à M. P. L., résidant à Rome depuis longtemps (Paris: Hôtel Drouot, April 3, 1865), 4, as Portrait d’homme. P.L..

Supplément au catalogue des tableaux, études peintes, dessins et croquis de J.-A.-D. Ingres, exh. cat. (Paris: Ad. Lainé et J. Havard, 1867), 74, as Lemoyne (M.).

Charles Blanc, Ingres: sa vie et ses ouvrages (Paris: Veuve Jules Renouard, 1870), 234, as Portrait de M. Lemoyne.

Henri Delaborde, Ingres: sa vie, ses travaux, sa doctrine d’après les notes manuscrites et les lettres du maitre [sic] (Paris: Henri Plon, 1870), no. 136, p. 254, as Lemoyne.

Jean Gigoux, Causeries sur les artistes de mon temps, 3rd ed. (Paris: Calmann Lévy, 1885), 84–85.

Le Chevalier du Guet, “M. Jean Gigoux et ses ‘Souvenirs’,” Le Figaro, no. 3 (January 3, 1885): 2.

Sutter Laumann, “Revue littéraire: Causeries sur les artistes de mon temps, par M. Jean Gigoux, orné d’un portrait de l’auteur (Calmann-Lévy, éditeur.),” La Justice, no. 1895 (March 23, 1885): 2.

Henry Jouin, Musée de portraits d’artistes, peintres, sculpteurs, architectes, graveurs, musiciens, artistes dramatiques, amateurs, et., nés en France ou y ayant vécu. État de 3000 portraits; Peints, dessinés ou sculptés avec l’indication des collections publiques ou privées qui les renferment (Paris: H. Laurens, 1888), 115.

“Ingres: Portrait de Dédébau [sic],” La Revue des musées: musée d’art scolaire, no. 52 (December 1889): 2–3.

Henry Lapauze, Les dessins de J.-A.-D. Ingres du Musée de Montauban (Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1901), 235, 248, as Bustes: – de Lemoyne.

J[ules] Momméja, Les Grands artistes: leur vie–leur œuvre; Ingres: Biographie critique (Paris: Henri Laurens, 1904), 69, as Lemoyne.

Octave Uzanne, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres: Painter, trans. Helen Chisholm (London: George Newnes, 1906), xiii, as M. Paul Lemoine [sic] the sculptor.

François Ponsard, “Notes et souvenirs: Autour de Jean Gigoux,” Le Temps, no. 16,950 (November 20, 1907): unpaginated.

R.A. M[eyer], “Die Sammlung Cheramy,” Monatshefte Für Kunstwissenschaft 1, no. 4 (1908): 359.

Catalogue des tableaux anciens et modernes, aquarelles, pastels, dessins; œuvres remarquables de Boltraffio, Chardin, Corot, Courbet, David, Degas, Foppa, Géricault, Goya, Greco, Ingres, Millet (J.-F.), Puvis de Chavannes, Reynolds, Prud’hon, Tassaert, Vinci (atelier de Léonard de), etc.; très importante collection d’œuvres de Constable et de Eugène Delacroix; primitifs italiens; composant la collection P. A. Cheramy (Paris: Galerie Georges Petit, May 5–7, 1908), 86, as Portrait du sculpteur Paul Lemoyne.

R. A. Meyer, “Die Vente Cheramy. II. Die Resultate,” Monatshefte Für Kunstwissenschaft 1, no. 5 (1908): 490, as Porträt des Bildhauers Lemoyne.

J[ulius] Meier-Graefe and E[rich] Klossowski, La collection Cheramy: catalogue raisonné précédé d’études sur les maîtres principaux de la collection (Munich: R. Piper, 1908), 73, as Portrait du sculpteur Lemoyne.

Henry Lapauze, “Ingres à Rome (1811–1820),” La Revue de Paris 2 (March 1911): 609.

Exposition Ingres, 26 Avril–14 Mai: organisée au profit du Musée Ingres, exh. cat. (Paris: Georges Petit, 1911), 21, as Portrait de Paul Lemoyne, sculpteur.

“A [sic] la Gloire d’Ingres,” La Dépêche, no. 15,619 (April 27, 1911): 3, as le sculpteur Paul Lemoyne.

Étienne Charles, “L’Exposition Ingres,” La Liberté, no. 16,399 (April 27, 1911): 2, as le Sculpteur Paul Lemoyne.

Tout-Paris, “Bloc-Notes Parisien: L’Exposition Ingres,” Le Gaulois, no. 12,248 (April 27, 1911): 1.

Charles Saunier, “Exposition Ingres,” Les Arts, no. 115 (July 1911): 16, (repro.), as Paul Lemoyne, sculpteur.

“Expositions: Exposition Ingres,” Les Arts, supplement to no. 121 la Revue Les Arts (December 1911): S9, S11, as Paul Lemoyone, sculpteur.

“Table des matières: Collection de M. H. Haro,” Les Arts: Revue Mensuelle des Musées, Collections, Expositions, supplement to no. 121 (December 1911): S6, as Paul Lemoyne, sculpteur.

“La Curiosité: La collection Haro,” Gil Blas, no. 12,718 (December 11, 1911): 4.

Catalogue des tableaux anciens des écoles primitives et de la Renaissance et des écoles flamande, française, hollandaise et italienne des XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles; œuvres de Backhuisen, B. de Bruyn, Ch. Coypel, Cranach, B. Cuyp, Danloux, Elias, J.-B. Greuze, Baron Gros, Heda, J.-B. Huet, J. Jovenet, Mme Vigée-Lebrun, Lenain, Leprince, van der Meulen, le Pontormo, P.-P. Prudhon, H. Rigaud, Hubert Robert, Roslin, Santerre, J. Steen, G. Terburg, Tournières, F. de Troy, W. van den Velde, Joseph Vernet, C. de Vos, etc.; tableaux modernes par Cabat, Carolus Duran, Chaplin, E. Delacroix, E. Deveria, Ingres, H. Regnault, Th. Ribot, Roybet, Sisley, F. Thaulow, Verboeckhoven, Horace Vernet, Ziem, etc.; composant la collection de M. Henri Haro et dont la vente, par suite de son décès, aura lieu a Paris (Paris: Hôtel Drouot, December 12–13, 1911), 121, as Portrait du sculpteur Paul Lemoyne.

Valemont, “Vente de la Collection Henri Haro,” Le Figaro, no. 348 (December 14, 1911): 7, as Portrait du sculpteur Lemoine [sic].

“Art et curiosité: La collection Haro,” Le Temps, no. 18,428 (December 15, 1911): unpaginated, as Portrait du sculpteur Paul Lemoyne.

“Mouvement des arts: Collection Henri Haro,” La Chronique des arts et de la curiosité, no. 38 (December 23, 1911): 302, as Portrait du sculpteur Paul Lemoyne.

Henry Lapauze, Ingres, sa vie et son œuvre (1780–1867): D’après des documents inédits (Paris: Imprimerie Georges Petit, 1911), 163–64, 179, (repro.), as Portrait du sculpteur Lemoyne.

The Masterpieces of Ingres (1780–1867): sixty reproductions of photographs from the original paintings affording examples of the different characteristics of the Artist’s work (London: Gowans and Gray, 1914), 25, (repro.), as Paul Lemoyne the Sculptor, Le sculpteur Paul Lemoyne, and Der Bildhauer Paul Lemoyne.

Exposition d’art français du XIXe siècle, exh. cat. (Copenhagen: Dansk Kunstmuseums Forening, 1914), 33, as Billedhuggeren Lemoyne, Le Sculpteur Lemoyne.

Baron Desazars de Montgailhard, “La Contribution des artistes-toulousains,” Mémoires de l’Académie des sciences, inscriptions et belles-lettres de Toulouse 8 (1920): 181, as Lemoyne.

Isabella Errera, Répertoire des peintures datées (Brussels: G. Van Oesta, 1920–1921), 2:532, as Lemoyne, Paul.

Jacqueline Henri-Bouchot, “Jean Gigoux (1806–1894),” Gazette des beaux-arts 3 (March 1921): 190.

Cent Ans de Peinture Française: Exposition au Profit du Musée des Beaux-Arts de Strasbourg, exh. cat. (Paris: Hôtel de la Chambre syndicale de la curiosité et des beaux-arts, 1922), unpaginated, (repro.), as Portrait du sculpteur Lemoyne.

“L’Actualité: Cent Ans de Peinture Française,” L’Art et les artistes 5, no. 25 (March 1922): 282.

“Cent ans de peinture française,” Paris-midi, no. 3,611 (March 22, 1922): 3, as Lemoyne.

Pierre Borel, “Le ‘Rubens’ de Bonnat,” Le Figaro, no. 204 (March 3, 1923): 2.

Louis Hourticq, Ingres: L’œuvre du maître (Paris: Librairie Hachette, 1928), IV, as portrait du sculpteur Lemoyne.

A. C. R. Carter, “Forthcoming Sales. Votes and Bids: Busy June in Prospect,” Burlington Magazine 54, no. 315 (June 1929): lix, as Paul Lemoyne.

La Comoedia, no. 5,982 (June 3, 1929): 1, (repro.), as Portrait du sculpteur Lemoyne.

“La Curiosité,” Excelsior, no, 6,762 (June 17, 1929): 2, as le Sculpteur Paul Lemoyne.

Catalogue des tableaux et dessins par J.-A.-D. Ingres, composant la Collection de Monsieur Henry Lapauze et dont la vente aux enchères publiques, après décès, aura lieu (Paris: Imprimerie Lahure, June 21, 1929), 36–37, (repro.), as Portrait du sculpteur Paul Lemoyne.

“Coup de brosse: La vente Lapauze,” L’Œil de Paris (1929): 9, as Portrait de Lemoyne.

“715,000 francs une toile d’Ingres,” Le Petit parisien (June 22, 1929): 2, as Portrait du sculpteur Paul Lemoyne.

L.-Maurice Lang, “La première vacation des œuvres d’Ingres à l’hôtel Drouot a produit 3.091.710 francs,” Le Journal, no. 13,397 (June 22, 1929): 4, as Portrait du sculpteur Paul Lemoyne.

“La vente des Ingres de M. Henry Lapauze,” Le Matin, no. 16,530 (June 22, 1929): unpaginated, as Un portrait du sculpteur Paul Lemoyne.

F. R., “La collection Henry Lapauze a été vendue trois millions,”La Comoedia, no. 6,001 (June 22, 1929): 1, as Portrait du sculpteur l’ami Lemoyne.

“Un success pour la peinture classique: Tableaux et dessins d’Ingres se vendent cher,” Le Petit journal (June 22, 1929): 2, as Portrait du Sculpteur Lemoyne.

“On a vendu jeudi pour près de 4 millions d’œuvres d’Ingres,” L’Ouest-Éclair, no. 10,100 (June 23, 1929): 2, as Portrait du sculpteur Paul Lemoyne.

Le Wattman, “Nos Échos: On dit que . . . ,” L’Intransigeant, no. 18,143 (June 23, 1929): 2.

“Ingres Collection Sold for £31,000,” Times (London), no. 45,237 (June 24, 1929): 13.

Pierre Imbourg, “Curiosités: Un coup d’œil à l‘Hôtel Drouot,”Paris-soir, no. 2,091 (June 27, 1929): unpaginated, as Portrait du sculpteur Paul Lemoyne.

Miguel Zamacoïs, “Un flâneur à l’Hôtel des Ventes,” Candide, no. 276 (June 27, 1929): 6, as Portrait du sculpteur Lemoyne.

G., “Auktionsnachrichten,” Künst und Künstler 10 (July 1929): 408, (repro.), as Der Bilderhauer P. Lemoyne.

Curiosa, “Revue des ventes: Les grands ventes du printemps; Collection Henry Lapauze,” Le Gaulois artistique, no. 36 (July 25, 1929): 387, (repro.), as Portrait du sculpteur P. Lemoyne.

The Social Calendar (February 24, 1930): (repro.).

“Knoedler advertisement,” Bulletin (Museum of French Art, French Institute in the United States), no. 6 (April 1930): 21, (repro.), as Du Sculpteur Lemoigne [sic].

M[inna] K. P[owell], “Art: Crowds Filled Art Institute Gallery Yesterday for the First of Season’s Exhibitions – Paintings for Nelson Gallery Attract Most Attention,” Kansas City Times 93, no. 239 (October 6, 1930): 10, as portrait of Paul Lemoigne [sic], the sculptor.

Exhibition of Paintings by Old Masters, exh. cat. (Pittsburgh: Carnegie Institute, 1930), unpaginated, as Portrait of the Sculptor, Paul Lemoyne.

October Exhibitions: Paintings Lent by M. Knoedler and Company, Chicago; Paintings by Guy Maccoy and Grace Pettit; and an Exhibition of Sculpture and Drawings by George Hilbert, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Kansas City Art Institute, 1930), unpaginated, as Port. du Sculpteur, Paul Lemoigne [sic].

M. R. R., “Loan Exhibition of French Painting, 1800–1880,” Bulletin of the City Art Museum of St. Louis 16, no. 1 (January 1931): unpaginated, as Portrait of the Sculptor, Paul Lemoyne.

Les Arts 17 (March 1931).

Carlyle Burrows, “Letter from New York,” Apollo 13, no. 76 (April 1931): 237–38, (repro.), as Portrait of the Sculptor Lemoyne.

Apollo 15 (January–June 1932): 106.

“A Warning in Art Talk: Hearers Detect a Reminder in a Remark by Parsons,” Kansas City Times 95, no. 16 (January 19, 1932): 3.

“M. Claudel in Rich Land: A Desire to See Harvest Expressed by Ambassador,” Kansas City Times 95, no. 70 (March 22, 1932): 11.

M[inna] K. P[owell], “In Gallery and Studio,” Kansas City Star 52, no. 212 (April 16, 1932): E.

“Art News,” Kansas City Journal-Post, no. 315 (April 17, 1932): 2C, (repro.).

“Kansas City Adds Important Works to its Holdings: Works Recently Bought for the William Rockhill Nelson Trust All Secured from Leading New York Dealers,” Art News 30, no. 30 (April 23, 1932): 5, 8, as The Portrait of the Sculptor, Paul Lemoyne.

“Added to the Nelson Gallery Collection,” Kansas City Star 52, no. 220 (April 24, 1932): 3, (repro.), as Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne.

Art News 30, no. 31 (April 30, 1932): 6, (repro.), as Portrait of the Sculptor, Paul Lemoyne.

“Kansas City Art Museum Adds Important Pictures to Collection,” Art Digest 6, no. 15 (May 1, 1932): 3, (repro.), as The Sculptor, Paul Lemoyne.

The Art Index: January 1929 to September 1932 (New York: H. W. Wilson, 1932), 737, 837, as Portrait of the sculptor Paul Lemoyne.

M[inna] K. P[owell], “Books That Will Give Kansas Citians True Appreciation of Nelson Gallery,” Kansas City Star 53, no. 330 (August 13, 1933): 8D.

Pierre Domène, “Le nouveau musée de Kansas City,” Beaux-Arts 72, no. 48 (December 1, 1933): 2.

“Nelson Gallery of Art Special Number,” Art Digest 8, no. 5 (December 1, 1933): 13, 20–21, (repro.), as Portrait of Paul Lemoyne.

“American Art Notes,” Connoisseur 92, no. 388 (December 2, 1933): 419.

“Complete Catalogue of Paintings and Drawings,” and Alfred M. Frankfurter, “Paintings in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art,” in “The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art, Kansas City Special Number,” Art News 32, no. 10 (December 9, 1933): 28, 30, 45, (repro.), as Portrait of Paul Lemoyne and Portrait of the Sculptor Lemoyne.

Minna K. Powell, “The First Exhibition of the Great Art Treasures: Paintings and Sculpture, Tapestries and Panels, Period Rooms and Beautiful Galleries Are Revealed in the Collections Now Housed in the Nelson-Atkins Museum—Some of the Rare Objects and Pictures Described,”Kansas City Star 54, no. 84 (December 10, 1933): 4C, as Portrait of Le Moyne [sic].

“$15,000,000 Nelson Art Gallery Opens: Gift of Kansas City Star Publisher—Museum Has Many Innovations,” Boston Evening Transcript, no. 288 (December 11, 1933): 11.

Luigi Vaiani, “Art Dream Becomes Reality with Official Gallery Opening at Hand: Critic Views Wide Collection of Beauty as Public Prepares to Pay its First Visit to Museum,” Kansas City Journal-Post, no. 187 (December 11, 1933): 7.

“Art Critics View Nelson Gallery: Preview of Edifice, Costing $15,000,000 with Contents, Held at Kansas City,” New York Times 83, no. 27,715 (December 11, 1933): 24L.

“Nelson Gallery of Art Opened at Kansas City: $14,000,000 Gift of ‘Star’ Publisher and His Heirs Already Fully Furnished; Has Many Innovations; Oriental, Roman, Colonial Objects World Famous,” New York Herald Tribune 93, no. 31,802 (December 11, 1933): 12.

“Nelson Gallery of Art Opens,” Editor and Publisher 66, no. 31 (December 16, 1933): 10.

“Praises the Gallery: Dr. Nelson M’Cleary, Noted Artist, a Visitor, In a Visit to Nelson Collection the Former Kansas Citian Gives Warmest Approval to the Exhibits,” Kansas City Star 54, no. 98 (December 24, 1933): 9A.

The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Handbook of the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Art, 1933), 41, 47, (repro.), as Portrait of Paul Lemoyne.

“Museums, Art Associations and Other Organizations,” American Art Annual 30, Special Issue For the Year 1933 (1934): 175, as Portrait of Paul Lemoyne.

A. J. Philpott, “Kansas City Now in Art Center Class: Nelson Gallery, Just Opened, Contains Remarkable Collection of Paintings, Both Foreign and American,” Boston Sunday Globe 125, no. 14 (January 14, 1934): 16.

Exhibition of French Painting, from the Fifteenth Century to the Present Day, exh. cat. (San Francisco: California Palace of the Legion of Honor, 1934), 18, 53, as Portrait of the Sculptor, Paul Lemoyne.

Laura Lapham Lindow, Chronological Art Chart of 2,250 Painters (Milwaukee: Broadway Press, 1936), 14, as Paul Lemoyne.

Arts Magazine 12 (1937): 49, as Portrait de Lemoyne.

Forty-Seventh Annual Exhibition of Paintings, exh. cat. (Lincoln, NE: Nebraska Art Association, 1937), unpaginated, (repro.), as Portrait of Paul Lemoyne.

“Annual Nebraska Art Association Exhibit Officially Opens February 28,” Nebraska State Journal (February 21, 1937): 3CD, (repro.), as Portrait of Paul Lemoyne.

Forty-Seventh Annual Exhibition of Paintings, exh. cat. (Lincoln, NE: Nebraska Art Association, 1937), unpaginated, (repro.), as Portrait of Paul Lemoyne.

John Lee Clarke, David and Ingres: Paintings and Drawings, exh. cat. (Springfield, MA: Springfield Museum of Fine Arts, 1939), unpaginated, (repro.), as Portrait of the Sculptor, Paul Lemoyne.

Ella S. Siple, “Exhibitions of French Art in New York and Springfield,” Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 75, no. 441 (December 1939): 249, as Lemoyne.

“Temporary Exhibitions,” Gallery News (William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) 8, no. 3 (December 1941): unpaginated, as Portrait of LeMoyne [sic].

The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, The William Rockhill Nelson Collection, 2nd ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1941), 41, 49, 168, (repro.), as Portrait of Paul Lemoyne.

The Taft Museum Presents an Exhibition: The Fashion for the Greeco [sic] -Roman Taste of the Continent and the New Republic, 1795–1830, exh. cat. (Cincinnati, OH: Taft Museum, 1947).

“Loans,” Gallery News (William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) 13, no. 10 (October 1947): unpaginated, as Portrait of Lemoyne.

“French Art Is Topic: Sixth in Gallery Lecture Series to be Given Tomorrow; Rare Brocades and Silks Will Be Discussed by Paul Gardner in Session on Wednesday,” Kansas City Star 68, no. 61 (November 17, 1947): 16.

Mary Alexander, “Week in Art Circles,” Cincinnati Enquirer (November 30, 1947), (repro.), clipping, Scrapbook, NAMA Archives, as Portrait of the Sculptor, Paul Lemoyne.

Dorothy Adlow, “Art in Kansas City—Music and Theaters—Exhibitions in San Francisco: Masterpieces of Many Schools To Be Seen in Nelson Gallery,” Christian Science Monitor 40, no. 197 (July 17, 1948): 12.

Alain [Émile-Auguste Chartier], Ingres (Paris: Éditions du Dimanche, 1949), unpaginated.

The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, The William Rockhill Nelson Collection: Housed in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 3rd ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1949), 63, (repro.), as Portrait of Paul LeMoyne [sic].

Georges Wildenstein, Ingres (London: Phaidon, 1954), no. 130, pp. 190–91, 235 (repro.), as Paul Lemoyne, known as Lemoyne Saint Paul, a sculptor.

French Pre-Impressionist Painters of the Nineteenth Century: Paintings, Watercolors, Drawings, Graphics, exh. cat. (Winnipeg: Winnipeg Art Gallery, 1954), 11, (repro.), as Portrait of the Sculptor, Paul Lemoyne.

Three Exhibitions: Notable Paintings from Midwestern Collections, Notable Collections at Joslyn Art Museum, Anniversary Purchase Exhibition, exh. cat. (Omaha, NE: Joslyn Art Museum, 1956), unpaginated, as Portrait of the Sculptor, Paul Lemoyne.

Georges Wildenstein, Ingres, 2nd ed. (London: Phaidon, 1956), no. 130, pp. 190–91, (repro.), as Paul Lemoyne, known as Lemoyne Saint Paul, a sculptor.

Hans Naef, “Notes on Ingres Drawings, Part II,” Art Quarterly 20, no. 3 (Autumn 1957): 299–301.

Collectors’ Firsts: A Loan Exhibition Chosen by Art Museum Directors and Owners of Collections in the Atlanta Art Association Galleries, exh. cat. (Atlanta: Atlanta Art Association Galleries, 1959), unpaginated, as Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne.

The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Handbook of the Collections in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Kansas City, Missouri, 4th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1959), 119, (repro.), as Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne and The Sculptor, Paul Lemoyne.

“Treasures of Kansas City,” Connoisseur 145, no. 584 (April 1960): 123.

Maurice Grosser, “Art,” Nation 191 (July 9, 1960): 38 [repr., Maurice Grosser, Critic’s Eye (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1962), 180].

Ingres in American Collections: Loan Exhibition for the Benefit of the Lighthouse, New York Association for the Blind, exh. cat. (New York: Paul Rosenberg, 1961), 34, 62, (repro.), as The Sculptor Paul Lemoyne.

John Canaday, “Ingres: A Romantic Classicist: Works Displayed in New York Show His Creativity,” New York Times 110, no. 37,694 (April 7, 1961): L26, (repro.), as The Sculptor Paul Lemoyne.

John Canaday, “The Benefit Exhibitions: Two Current Examples Demonstrate the Range and The Public Service Offered by These Shows,” New York Times 110, no. 37,696 (April 9, 1961): X20, (repro.), as The Sculptor Paul Lemoyne.

Maurice Grosser, The Painter’s Eye (New York: New American Library, 1961).

Robert K. Sanford, “Two Books—Photos and Criticism,” Kansas City Star 82, no. 273 (June 17, 1962): 10E.

Adeline Cacan, Maurice Sérullaz, and Pierre Rosenberg, Ingres, exh. cat. (Paris: Ministère d’État affaires culturelles, 1967), 68.

Ingres Centennial Exhibition, 1867–1967: Drawings, Watercolors and Oil Sketches from American Collections, exh. cat. (Cambridge, MA: Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, 1967), unpaginated, (repro.), as Portrait of Paul Lemoyne, Sculptor.

Ingres in Italia (1806–1824; 1835–1841), exh. cat. (Rome: De Luca Editore, 1968), 30.

Emilio Radius and Ettore Camesasca, L’opera completa di Ingres (Milan: Rizzoli Editore, 1968), no. 100, pp. 100, 119, (repro.), as Paul Lemoyne.

Hans Naef, “L’Ingrisme dans le monde,” Bulletin du Musée Ingres, no. 27 (July 1970): 36, as Paul Lemoyne.

Patricia Pate Havlice, Art in Time (Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow, 1970), 151, as Paul Lemoyne.

Daniel Ternois and Ettore Camesasca, Tout l’œuvre peint d’Ingres, trans. Simone Darses (Paris: Flammarion, 1971), no. 101, pp. 100, 119, (repro.), as Paul Lemoyne.

Ross E.Taggart and George L. McKenna, eds., Handbook of the Collections in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Kansas City, Missouri, vol. 1, Art of the Occident, 5th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1973), 150, 153, (repro.), as Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne.

Antoinette Le Normand, “Paul Lemoyne, un sculpteur français à Rome au XIXe siècle,” Revue de l’art, no. 36 (1977): 32, 36.

John Minor Wisdom, French Nineteenth Century Oil Sketches: David to Degas, exh. cat. (Chapel Hill, NC: William Hayes Ackland Memorial Art Center, 1978), 6–7, 91–92, (repro.), as Portrait of the Sculptor, Paul Lemoyne.

Hans Naef, Die Bildniszeichnungen von J.-A.-D. Ingres (Bern: Benteli Verlag, 1979), 3:301–02, 308, 310–11, (repro.), as Paul Lemoyne.

Daniel Ternois, Ingres (Paris: Fernand Nathan, 1980), 47, 179, (repro.), as Paul Lemoyne.

Patricia Condon, Marjorie B. Cohn, and Agnes Mongan, Ingres, In Pursuit of Perfection: The Art of J.-A.-D. Ingres, ed. Debra Edelstein, exh. cat. (Louisville, KY: J. B. Speed Art Museum, 1983), 140, 210, (repro.), as The Sculptor Paul Lemoyne.

Tom L. Freudenheim, ed., American Museum Guides: Fine Arts; A Critical Handbook to the Finest Collections in the United States (New York: Collier, 1983), 112.

Donald A. Rosenthal, “The Portrait of Pierre-Francois Bernier by Ingres,” Porticus: The Journal of the Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester 7 (1984): 26, 29n7, (repro.), as Portrait of Paul Lemoyne.

Phil I. Stine, “From the Editor,” Kansas City Star 108, no. 113 (January 31, 1988): 3.

Memorial Art Gallery: An Introduction to the Collection (Rochester, NY: University of Rochester, Memorial Art Gallery, 1988), 113, as Portrait of Paul Lemoyne.

Richard L. Anderson, Calliope’s Sisters: A Comparative Study of Philosophies of Art (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1990), xii, 212–13, (repro.), as Portrait of the Sculptor, Paul Lemoyne.

Annalisa Zanni, Ingres: catalogo completo dei dipinti (Florence: Cantini, 1990), no. 65, p. 85, (repro.), as Paul Lemoyne.

Matthieu Pinette and Françoise Soulier-François, De [from] Bellini à [to] Bonnard: Chefs-d’œuvre de la peinture du musées des beaux-arts et d’archéologie de Besançon, trans. Elizabeth Wiles-Portier, exh. cat. (Paris: Pierre Zech, 1992), 160.

Hearne Christopher Jr., “Highbrow crawlers, here’s fun for you,” Kansas City Star 113, no. 338 (August 21, 1993): E3, (repro.).

Roger Ward and Patricia J. Fidler, eds., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collections (New York: Hudson Hills Press, in association with Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art 1993), 130, 199, (repro.), as Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne.

Uwe Fleckner, Abbild und Abstraktion: Die Kunst des Porträts im Werk von Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (Mainz, Germany: Verlag Philipp von Zabern, 1995), 83–87, (repro.), as Porträt Paul Lemoyne.

Georges Vigne, Ingres (Paris: Citadelles et Mazenod, 1995), 144, 325, 327, 332, as Lemoyne.

Matthias Vogel, Regine Helbling, and Marianne Baltensperger, eds., “Gepudert und geputzt:” Johann Melchior Wyrsch, 1732–1798, Porträtist und Kirchenmaler, exh. cat. (Basel: Schwabe, 1998), 183, (repro.), as Der Bilderhauer Paul Lemoyne.

Gary Tinterow and Philip Conisbee, eds., Portraits by Ingres: Image of an Epoch, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1999), 129–33, 154, (repro.), as Paul Lemoyne.

Gary Tinterow, Charlotte Hale, and Eric Bertin, “‘Portraits by Ingres: Image of an Epoch’: Reflections, Technical Observations, Addenda, and Corrigenda,” Metropolitan Museum Journal 35 (2000): 194, 211, as Paul Lemoyne.

John Loughery, “The Portraits of Ingres,” Hudson Review 52, no. 4 (Winter 2000): 641.

Anita Brookner, Romanticism and Its Discontents (London: Viking, 2000), 103–04, (repro.), as Portrait of Paul Lemoyne.

Uwe Fleckner, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres: 1780–1867 (Cologne: Könemann Verlagsgeselleschaft mbH, 2000), 46–48, (repro.), as Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne.

Sigrid Hofer, “Das Porträt Im Frühwerk Adolph Von Menzels,” Zeitschrift Für Kunstgeschichte 64, no. 1 (2001): 88, 91, (repro.), as Paul Lemoyne.

Olivier Bonfait, Maestà di Roma: da Napoleone all’unità d’Italia: da Ingres a Degas, artisti francesi a Roma, exh. cat. (Milan: Electa, 2003), 205, 495n2, (repro.), as Le sculpteur Paul Lemoyne.

Halina Goldberg, The Age of Chopin: Interdisciplinary Inquiries (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2004), 30, as Paul Lemoyne.

Emmanuel Bénézit, Dictionary of Artists (Paris: Gründ, 2006), 7:558–59.

Éric Bertin, Biochronologie Ingres (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2006), unpaginated, as Portrait d’homme (P.L.).

Karin H. Grimme, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, 1780–1867 (Cologne: Taschen, 2006), 47, 50, (repro.), as Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne.

Deborah Emont Scott, ed., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collection, 7th ed. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2008), 35, 110, (repro.), as Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne.

Catherine Futter et al., Bloch Galleries: Highlights from the Collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2016), 19, (repro.), as Portrait of the Sculptor Paul Lemoyne.

Guillaume Kazerouni and Yohan Rimaud, eds., De David à Courbet: chefs-d’œuvre du Musée des beaux-arts et d’archéologie de Besançon, exh. cat. (Ghent, Belgium: Snoeck, 2016), 162.

Julien Cosnuau, Guide des collections du musée des beaux-arts et d’archéologie de Besançon (Cinisello Balsamo, Italy: Silvana Editoriale, 2018), 239, as Portrait de Paul Lemoyne.

Stéphane Guégan and Florence Viguier-Dutheuil, Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres: e la vita artistica al tempo di Napoleone, exh. cat. (Venice: Marsilio, 2019), 170–71, 239, (repro.), as Ritratto dello scultore Paul Lemoyne.