![]()

Georges Seurat, Study for "The Channel of Gravelines, Petit Fort Philippe,” 1890

| Artist | Georges Seurat, French, 1859–1891 |

| Title | Study for “The Channel of Gravelines, Petit Fort Philippe” |

| Object Date | 1890 |

| Alternate and Variant Titles | Étude: Gravelines; Étude pour “Gravelines, Petit Fort-Philippe”; Le Chenal de Gravelines: Petit Fort Philippe (Port) |

| Medium | Oil on panel |

| Dimensions (Unframed) | 6 1/4 x 9 7/8 in. (15.9 x 25.1 cm) |

| Credit Line | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Gift of Henry W. and Marion H. Bloch, 2015.13.22 |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Ellen W. Lee, “Georges Seurat, Study for “The Channel of Gravelines, Petit Fort Philippe,” 1890,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.726.5407.

MLA:

Lee, Ellen W. “Georges Seurat, Study for “The Channel of Gravelines, Petit Fort Philippe,” 1890,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.726.5407.

Perhaps it is the dominance of A Sunday on La Grande Jatte (1884–1886; Art Institute of Chicago) in the popular awareness of Georges Seurat’s work that has made it more difficult to take stock of the important role that seascapes play in his art. From 1885 through 1890, Seurat completed more than twenty luminous coastal views—products of his solitary trips to the French seaside. These quiet vistas, devoid of human presence, coexist with Seurat’s ambitious scenes of Parisian public life.

In the few years he had to establish it (before his untimely death at age thirty-one), Seurat formed a pattern of intense activity devoted to creating major works in his Paris studio during the autumn, winter, and spring. Summer was reserved for excursions to the French coast of the English Channel.1In his monograph devoted to Seurat, Richard Thomson provides a thoughtful analysis of the overall role of marine paintings within his oeuvre. Richard Thomson, Seurat (Oxford: Phaidon, 1985), 157–84. From 1885 through 1890, Seurat visited five locales: Grandcamp, Honfleur, Port-en-Bessin, Le Crotoy, and Gravelines. Honfleur is the only destination that could be considered at all fashionable or popular with his colleagues. His escapes from Paris had nothing to do with holidays or camaraderie. Indeed, Seurat’s summer destinations were noteworthy for their isolation. Poet Emile Verhaeren (Belgian, 1855–1916), a friend of Seurat and arguably his most insightful critic, reminisced about how Seurat spent his summer sojourns:

Then, in summer, to wash his eyes of the days in the studio and to translate as exactly as possible the vivid sunlight, with all its nuances. An existence divided in two, by art itself.2Émile Verhaeren, “Georges Seurat,” La Société Nouvelle 7 (April 1891): 433, reprinted (with slight variations, as noted by Robert Herbert) in Verhaeren, Sensations (Paris: Bibliothèque Dionysienne, Les Éditions G. Crès et Cie, 1927), 199. (“Puis, l’été, se laver l’œil des jours d’atelier et traduire le plus exactement la vive claret, avec toutes ses nuances. Une existence divisée en deux, par l’art lui-même.&rdqou;) For another translation of the full article, see Norma Broude, ed., Seurat in Perspective (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1978).

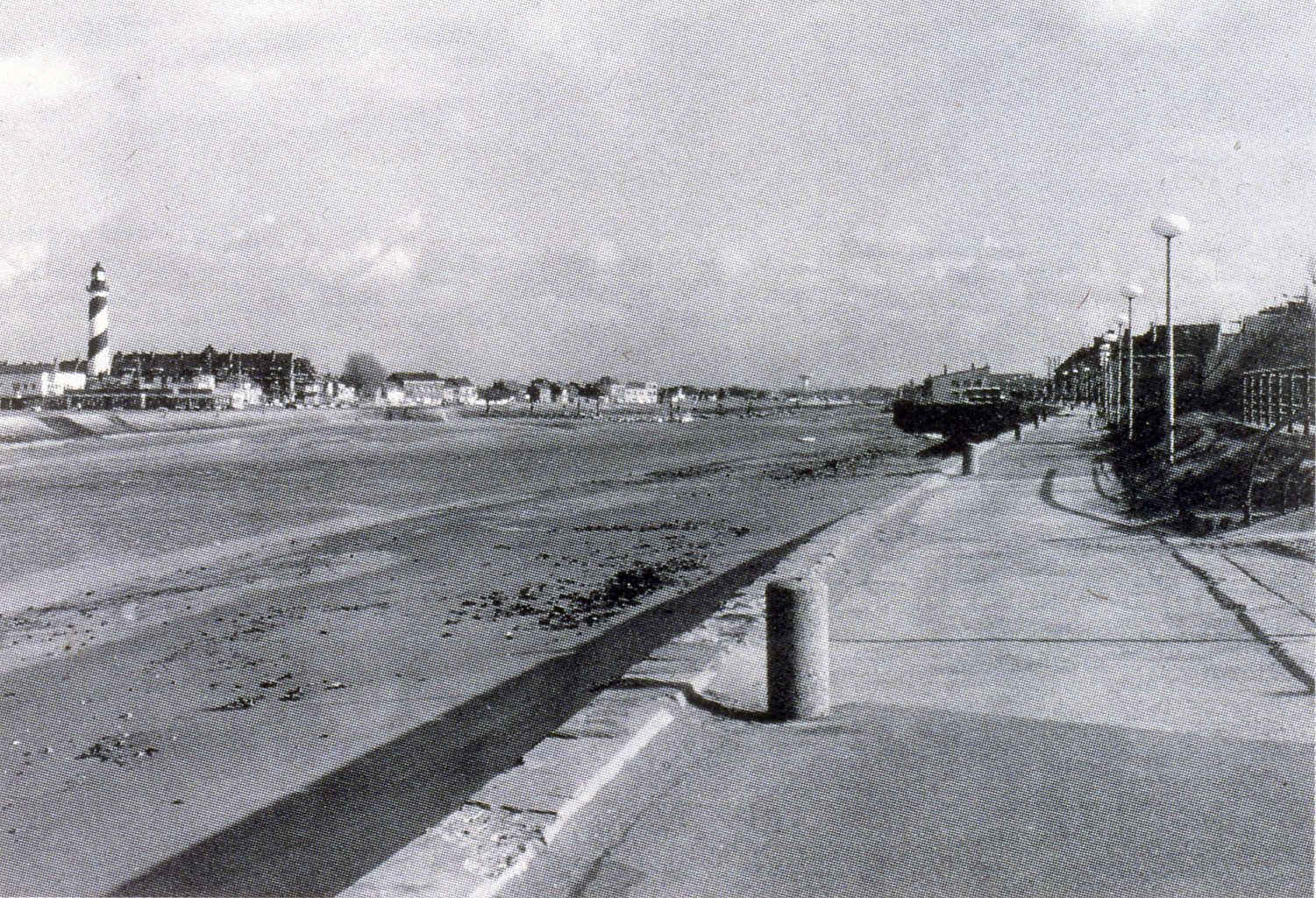

Seurat’s correspondence suggests that he arrived in Gravelines in late June 1890.3Seurat’s correspondence is slight, but on June 24, 1890, he wrote to critic Félix Fénéon: “I am going to the North around Calais?” (“Je vais dans le Nord environs de Calais?”) For a facsimile of letter, see C[ésar] M[ange] de Hauke, Seurat et son œuvre (Paris: Gründ, 1961), 1:XXIII. In this small seaport, he painted the Nelson-Atkins sketch in preparation for what became his last series of seaside pictures. As such, this panel is the ideal complement to the museum’s other Seurat sketch, the study for his first monumental figure painting, Bathers at Asnières. The palette, brushwork, and composition of the Gravelines work offer valuable insights into the conception of Seurat’s final seascapes.

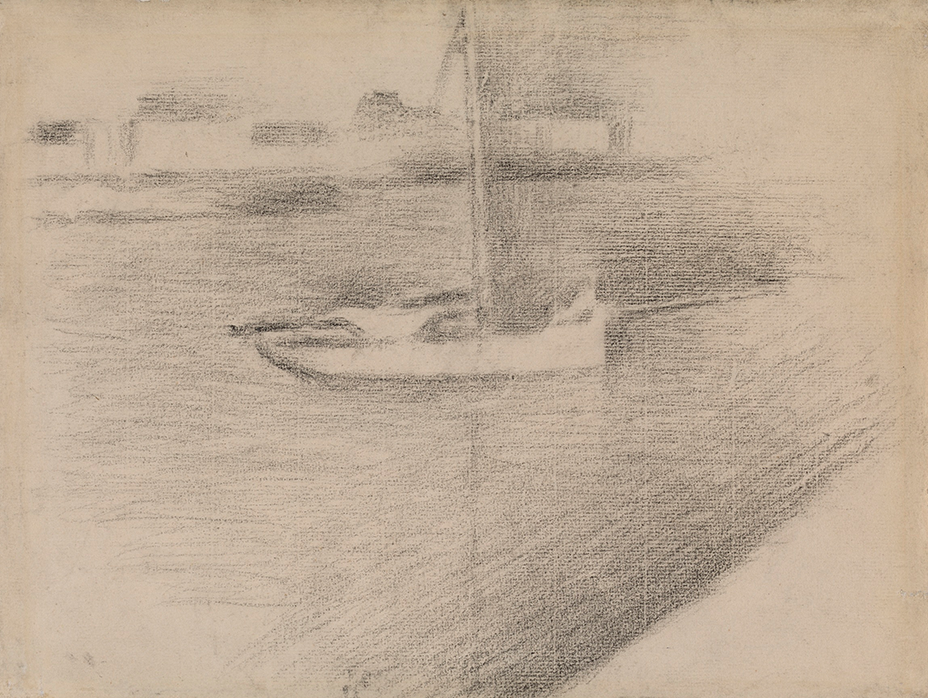

Seurat experimented with the placement of elements in the channel harbor, reminiscent of his trial-and-error process with some facets of the Asnières project. The two-masted boat at the promenade, so prominent in the sketch, is absent in the final version.8The boat removed from the final Indianapolis composition, however, does resemble the sole vessel present in another member of the Gravelines quartet, The Channel of Gravelines: Grand Fort Philippe (1890; National Gallery, London). It is replaced by a sturdy bollard that anchors the foreground, checking the diagonal motion of the promenade and keeping the lower portion free of any narrative distraction. Above and to the right of the boat in the Nelson-Atkins piece is also a cluster of deep blue dots, extending from the channel upward into the sky. This vague nautical suggestion coalesces in the completed work as a listing vessel, moored under the lighthouse.

Unmistakable in the Nelson-Atkins study is the energy of its staccato brushwork. It has the freshness and impetuosity of a sketch rendered on the spot. Even a casual glance reveals that Seurat’s famous facturefacture: The artist’s characteristic handling of paint., called pointillismpointillism: A technique of painting using tiny dots of pure colors, which when seen from a distance are blended by the viewer’s eye. It was developed by French Neo-Impressionist painters in the mid-1880s as a means of producing luminous effects., is actually quite varied here, with dots of pigment of different size, shape, and direction. Rooted in his broken brushwork of the early 1880s, Seurat’s pointillist technique emerged in the Grandcamp works of 1885, made during his first seaside excursion. The points of pigment enabled the artist to create both nuance and brilliance. While pointillism has become emblematic of Seurat’s signature style, the dots are just one factor in the artist’s pioneering application of color theory.

Working in the heady years following the Impressionist heyday, Seurat was one of several progressive painters pursuing new approaches. The Impressionists’ brighter color schemes and rapid execution attracted his attention, but the methodical Seurat wanted to replace their spontaneous practice with stable compositions and a less intuitive treatment of color. Seeking a rational basis for his color choices, Seurat turned to practices grounded in science. The effort to “reform” Impressionist practice led the fascinating critic of the avant-garde, Félix Fénéon (1861–1944),9Félix Fénéon, “Correspondance particulière de ‘L’Art moderne:’ L’Impressionnisme aux Tuileries,” L’Art Moderne 6, no. 38 (September 19, 1886): 302. to name Seurat’s style Neo-Impressionism, or new Impressionism, in 1886. This term has endured to describe Seurat’s fully conceived approach and that of his followers in the closing years of the nineteenth century. Given his choice, Seurat would have preferred chromoluminarism, a word that emphasized the color and light at the core of his agenda.

The later nineteenth century was a heyday of scientific exploration, and studies of optics and perception were no exception. Interpreting treatises by aestheticians and scientists,10Chief among Seurat’s sources are Michel Chevreul, Loi du Contraste Simultané des Couleurs et de l’Assortiment des Objets Colorés (Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, Librairie Gauthier-Villars et Fils, 1839); and Charles Blanc, Grammaire des Arts du Dessin, Architecture, Sculpture, Peinture (Paris: Librairie Renouard, 1867). Columbia University physicist Ogden Rood placed Seurat’s reasoning on an even firmer scientific basis by publishing his findings on color perception based on laboratory experiments: Rood, Modern Chromatics, with Applications to Art and Industry (New York: D. Appleton, 1879). Seurat built his approach to color using principles of contrast and optical mixture (mélange optique). Both principles are cited in a rare statement of theory Seurat sent to a critic in August 1890.11A photograph of this letter first appeared in Robert Rey, La Renaissance du sentiment Classique dans la Peinture française à la fin du XIXe siècle (Paris: Éditions G. Van Oest, 1931). Full documentation of all the versions of this letter can be found in Françoise Cachin and Robert Herbert, Seurat, exh. cat. (Paris: Éditions de la Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1991), 422–23, 429–31. There he specified his theories on the roles of complementary colors (opposites on the color wheel) and optical mixture as it occurs in the viewer’s eye. According to optical mixture, the dots of pigment on a canvas reflect colored light that blends in the eye to produce the viewer’s color perception. This method of creating color was found to be capable of producing more vibrant effects than the traditional practice of mixing pigments on the palette before applying them to the canvas. (An inelegant, simple demonstration of this distinction can be found by mixing all the colors in the standard watercolor box to discover the resultant muddied brown color. However, scientific experiments of Seurat’s era indicated that mixing the whole spectrum of colored light produces a clear, clean white.) Thus Seurat considered his dotted strokes the vehicles for generating the brighter effects of optical mixture.

In its excellent, unvarnished state, the Nelson-Atkins panel also speaks to the brilliant contrasts central to Seurat’s agenda. Fundamental to Neo-Impressionist color schemes were the contrasts of hues, especially complementary colors. Invoking the law of simultaneous contrast, Seurat and his followers held that applying two colors side by side heightens their differences, and if they are complementary colors the effect will be even brighter. A subtle but critical hint of that practice lies in the thin dotted border that surrounds the Nelson-Atkins sketch. While blue is its dominant color, the artist added tiny touches of pigment that vary in hue according to the color of the adjacent passage. Juxtaposed with the rose tones of the lower promenade, for example, are points of a complementary green. Merely suggested in the panel, the treatment is more fully executed in the finished painting, where red complements the green elements of the water on the left before changing to orange when the border meets the blue sky.

The border is also a clear reference to the evolution of Seurat’s treatment of frames, another highly original aspect of his pioneering work. The narrow border was conceived as a transitional element, intended to connect to a flat, painted wood frame dominated by the same ultramarine blue. In this way Seurat stimulated another means of contrast, as the delicate tones that shimmer across each of the finished works are enhanced by the dark outer color, emphasizing their gentle luminosity. Unfortunately, none of the dramatic frames for the Gravelines series have survived,12The frame for Le Crotoy, Looking Downstream (1889; Detroit Institute of Arts), is one of the few originals not discarded over the years in favor of traditional gilded moldings. but Verhaeren left us this impression of their effect: “It is air and light, even and tranquil, fixed in frames.”13Émile Verhaeren, “Chronique Artistique, Les XX,” La Société Nouvelle 7 (February 1891): 249.

The Gravelines sketch yields yet another insight into Seurat’s use of contrast. Along the right side of the white lighthouse, the artist has applied a vertical series of blue dots, using irradiation to emphasize the contour and suggest its volume. According to this principle, the differences between two adjacent areas of unequal lightness will be most pronounced at their common edge. Seurat’s blue strokes implement this effect.

The evolution from panel sketch to finished painting shows how Seurat fine-tuned these works by manipulating the variable elements. For the final composition, he formed a gentle pacing of boats across the channel, reinforcing the horizontal of the shore and contributing to the restrained structure of the composition. All the boats, save one in the background, have dropped sail, exposing their masts and repeating the verticals of the lighthouse and bollard. This kind of delicate equilibrium makes the Gravelines works paragons of harmony and suggests the artist’s commitment to their underlying geometry.

The Nelson-Atkins sketch is a rarity among the Gravelines corpus of works. Only one of the other three paintings in the series, The Channel of Gravelines, Evening (1890; Museum of Modern Art, New York), has a preparatory oil, and for the other two canvases, no studies on panel or paper are known to exist. The Nelson-Atkins panel was given by Seurat’s family to his colleague Maximilien Luce (1858–1941), who first allowed the work to be publicly exhibited in 1905 and subsequently lent it to at least four other exhibitions between 1906 and 1934.

As for the four completed compositions from his 1890 Gravelines sojourn, Seurat submitted them to the annual exhibition of the progressive Brussels group, Les XX (The Twenty), where he had just been elected a member. The exhibition took place in February and March of 1891. Ever loyal to the Société des Artistes IndépendantsSociété des Artistes Indépendants: A group founded in 1884 in Paris by Odilon Redon, Albert Dubois-Pillet, Georges Seurat, and Paul Signac that created the Salon des Indépendants as an alternative to exhibiting at the Salon organized and juried by the French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture (Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture). The Salon des Indépendants has no selection committee; instead, artists can exhibit on payment of a fee. The exhibitions became the main venue for many artists, particularly the Post-Impressionists in the late 19th century. The Salon des Indépendants is still in existence today. See also Salon, the., he next presented them in Paris, where he assisted with the hanging of the show, which opened on March 20, 1891. They were hanging there, along with his latest studio work, Circus (1890–1891; Musée d’Orsay, Paris) when, nine days later, Seurat died in the grip of a sudden infection. His colleague Paul Signac wrote to a fellow painter: “Terrible news: our poor Seurat died yesterday morning after a two-day sickness. . . . I am too desolate to write further.”14“Mon Théo, Une horrible nouvelle: notre pauvre Seurat est mort hier matin après deux jours de maladie. Une angine infectieuse, dit-on. Il laisse une pauvre femme, et ce que nous ne savions pas, un beau bébé de 13 mois qu’il a reconnu. La malheureuse est encore enceinte. Quel épouvantable malheur . . . Je suis trop malheureux pour vous écrire plus longuement” (My Théo, Terrible news: our poor Seurat died yesterday morning after a two-day sickness. An infectious angina, they say. He leaves a poor wife, and what we didn’t know, a beautiful 13-month-old baby whom he recognized. The unfortunate woman is pregnant again. What a terrible misfortune . . . I am too desolate to write further). Paul Signac to Théo van Rysselberghe, March 30, 1891. A copy of the letter exists in the Archives Signac, Paris. The entire letter is transcribed in Guy Pogu, Théo van Rysselberghe: Sa Vie (Paris: Premiers Éléments, 1963), 10–11.

The works inspired by Seurat’s last summer sojourn carry the legacy of the artist’s intricate methods, but their analysis cannot fully explain the essence of their expressive effect. In the Gravelines series, perhaps the most wistful of the marine pictures, intellectual rigor and disciplined handling, softened by gentle light and atmosphere, leave the viewer sensing the poetry of Seurat’s vision. Their firm structure, bearing the lightest of chromatic burdens, breathes a gentleness of spirit and an indelible sense of Seurat’s attachment to the sea.

Notes

-

In his monograph devoted to Seurat, Richard Thomson provides a thoughtful analysis of the overall role of marine paintings within his oeuvre. Richard Thomson, Seurat (Oxford: Phaidon, 1985), 157–84.

-

Emile Verhaeren, “Georges Seurat,” La Société Nouvelle 7 (April 1891): 433, reprinted (with slight variations, as noted by Robert Herbert) in Verhaeren, Sensations (Paris: Bibliothèque Dionysienne, Les Éditions G. Crès et Cie, 1927), 199. (“Puis, l’été, se laver l’œil des jours d’atelier et traduire le plus exactement la vive claret, avec toutes ses nuances. Une existence divisée en deux, par l’art lui-même.”) For another translation of the full article, see Norma Broude, ed., Seurat in Perspective (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1978).

-

Seurat’s correspondence is slight, but on June 24, 1890, he wrote to critic Félix Fénéon: “I am going to the North around Calais?” (“Je vais dans le Nord environs de Calais?”) For a facsimile of letter, see C[ésar] M[ange] de Hauke, Seurat et son œuvre (Paris: Gründ, 1961), 1:XXIII.

-

Karl Baedeker, Northern France from Belgium and the English Channel to the Loire, Excluding Paris and Its Environs: Handbook for Travellers (Leipzig: Karl Baedeker, 1894), 5.

-

Many details of the history and geography of Gravelines are available through a publication of the Ministry of Culture, Gravelines et son patrimoine (Dunkirk, 1983).

-

On my visit to Gravelines in 1990, Raymond Delahaye, a historian affiliated with the community, generously provided me with this reproduction of the map.

-

The other three works are The Channel of Gravelines, Grand Fort Philippe (1890; National Gallery, London), The Channel of Gravelines, Toward the Sea (1890; Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo), and The Channel of Gravelines, Evening (1890; Museum of Modern Art, New York). For a more thorough discussion of the entire Gravelines series, see Ellen Wardwell Lee, Seurat at Gravelines: The Last Landscapes, exh. cat. (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art in cooperation with Indiana University Press, 1990).

-

The boat removed from the final Indianapolis composition, however, does resemble the sole vessel present in another member of the Gravelines quartet, The Channel of Gravelines: Grand Fort Philippe (1890; National Gallery, London).

-

Félix Fénéon, “Correspondance particulière de ‘L’Art moderne:’ L’Impressionnisme aux Tuileries,” L’Art Moderne 6, no. 38 (September 19, 1886): 302.

-

Chief among Seurat’s sources are Michel Chevreul, Loi du Contraste Simultané des Couleurs et de l’Assortiment des Objets Colorés (Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, Librairie Gauthier-Villars et Fils, 1839); and Charles Blanc, Grammaire des Arts du Dessin, Architecture, Sculpture, Peinture (Paris: Librairie Renouard, 1867). Columbia University physicist Ogden Rood placed Seurat’s reasoning on an even firmer scientific basis by publishing his findings on color perception based on laboratory experiments: Rood, Modern Chromatics, with Applications to Art and Industry (New York: D. Appleton, 1879).

-

A photograph of this letter first appeared in Robert Rey, La Renaissance du sentiment Classique dans la Peinture française à la fin du XIXe siècle (Paris: Éditions G. Van Oest, 1931). Full documentation of all the versions of this letter can be found in Françoise Cachin and Robert Herbert, Seurat, exh. cat. (Paris: Éditions de la Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1991), 422–23, 429–31.

-

The frame for Le Crotoy, Looking Downstream (1889; Detroit Institute of Arts), is one of the few originals not discarded over the years in favor of traditional gilded moldings.

-

Emile Verhaeren, “Chronique Artistique, Les XX,” La Société Nouvelle 7 (February 1891): 249.

-

“Mon Théo, Une horrible nouvelle: notre pauvre Seurat est mort hier matin après deux jours de maladie. Une angine infectieuse, dit-on. Il laisse une pauvre femme, et ce que nous ne savions pas, un beau bébé de 13 mois qu’il a reconnu. La malheureuse est encore enceinte. Quel épouvantable malheur . . . Je suis trop malheureux pour vous écrire plus longuement” (My Théo, Terrible news: our poor Seurat died yesterday morning after a two-day sickness. An infectious angina, they say. He leaves a poor wife, and what we didn’t know, a beautiful 13-month-old baby whom he recognized. The unfortunate woman is pregnant again. What a terrible misfortune . . . I am too desolate to write further). Paul Signac to Théo van Rysselberghe, March 30, 1891. A copy of the letter exists in the Archives Signac, Paris. The entire letter is transcribed in Guy Pogu, Théo van Rysselberghe: Sa Vie (Paris: Premiers Éléments, 1963), 10–11.

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Diana M. Jaskierny, “Georges Seurat, Study for “The Channel of Gravelines, Petit Fort Philippe,” 1890,” technical entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.726.2088.

MLA:

Jaskierny, Diana M. “Georges Seurat, Study for “The Channel of Gravelines, Petit Fort Philippe,” 1890,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.726.2088.

Throughout the composition, the paint strokes are often directional, emphasizing the scene’s receding perspective to the right. In the foreground and middle ground, short, diagonal brushwork moves toward the top right corner, leading the viewer’s eye parallel to the direction of the walkway. In comparison, in the left and central portions of the sky, the brushwork alternates between horizontal and vertical short strokes (Fig. 10), while the marks in the right section of the sky are predominantly horizontal. The most haphazard brushwork is found in the water near the boat, imitating the rippling near the hull.

Notes

-

The panel measures 15.9 x 25.1 centimeters.

-

For more information on boîtes à pouce, see the technical entry by Diana M. Jaskierny for “Georges Seurat, Study for ‘Bathers at Asnières’” in this catalogue, https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.724.

-

Sand particles were also found in Seurat’s Beach at Gravelines (1890; The Courtauld Institute of Art). Impressionist and Post-Impressionist Masterpieces: The Courtauld Collection (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987), cat. 37.

-

In a survey of Seurat’s techniques, the National Gallery (London) and the Courtauld Institute of Art published an analysis of fifteen of the artist’s study paintings, including dimensions and preparation layers. Jo Kirby, Kate Stoner, Ashok Roy, Aviva Burnstock, Rachel Grout, and Raymond White, “Seurat’s Painting Practice: Theory, Development and Technology,” National Gallery Technical Bulletin 24 (2003): 5.

-

No organic or elemental analysis was conducted on Study for “The Channel of Gravelines, Petit Fort Philippe.”

-

In comparison, the figure or figures slightly closer to the center were added to the landscape at a later stage in the painting process, after the walkway was completed. The paint of the walkway extends beneath these added elements.

-

Øystein Sjåstad, A Theory of the Tache in Nineteenth-Century Painting (Farnham, UK: Ashgate, 2014), 105, 112.

-

No conservation treatment has been conducted at the Nelson-Atkins; however, the abrasions in the dark blue paint could indicate a cleaning where an early varnish was removed prior to entering the museum collection.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Georges Seurat, Study for “The Channel of Gravelines, Petit Fort Philippe,” 1890,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.726.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Georges Seurat, Study for “The Channel of Gravelines, Petit Fort Philippe,” 1890,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.726.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Georges Seurat, Study for “The Channel of Gravelines, Petit Fort Philippe,” 1890,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.726.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Georges Seurat, Study for “The Channel of Gravelines, Petit Fort Philippe,” 1890,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.726.4033.

With the artist, Paris, 1890–March 29, 1891 [1];

Probably inherited by the artist’s mother, Ernestine Seurat (née Faivre, 1828–1899), or common-law wife, Madeleine Knoblock (ca. 1868–1903), 1891 [2];

Given by Seurat or Knoblock to Maximilien Luce (1858–1941), Paris, 1891–at least January 1934 [3];

Probably by descent to his nephew, Édouard Alexandre Bouin (1897–1988), Paris and La Celle-Saint-Cloud, France, by February 6, 1941–no later than December 6, 1978;

By descent to his son, Jean Bouin-Luce (1920–1999), Paris and Mantes-la-Jolie, France, by December 6, 1978 [4];

Purchased at his sale, Important Impressionist and Modern Paintings and Sculpture, Sotheby Parke Bernet, London, December 6, 1978, no. 216, as Le Chenal de Gravelines; Petit Fort Philippe (Port), by Fujii Gallery, Tokyo, 1978–at least November 25, 1990 [5];

Purchased in a private sale from Sotheby’s, New York, through Richard L. Feigen and Co., New York, by Marion (née Helzberg, 1931–2013) and Henry (1922–2019) Bloch, Shawnee Mission, KS, July 10, 1996–June 15, 2015 [6];

Their gift to The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 2015.

Notes

[1] On May 3, 1891, one month after Seurat’s sudden death, Madeleine Knoblock, Émile Seurat, Paul Signac, Maximilien Luce, and Félix Fénéon gathered to inventory the contents of the artist’s atelier. They annotated the verso of each artwork with a number and the initials P. S., L., or F. F. Study for “The Channel of Gravelines, Petit Fort Philippe” bears the verso inscription “P S 138”.

[2] See email from Denise Bazetoux, independent art historian, to Meghan Gray, NAMA, May 18, 2015, NAMA curatorial files.

[3] Luce loaned Study for “The Channel of Gravelines, Petit Fort Philippe” to a series of exhibitions, including the Société des Artistes Indépendants: 21me exposition (Paris, March 24–April 30, 1905); the Ausstellung Franzoesischer Kuenstler (Munich, Frankfurt, and Dresden, November 1906–January 1907); the Exposition Georges Seurat (1859–1891) (Paris, December 14, 1908–January 9, 1909); Le Néo-Impressionnisme (Paris, February 25–March 17, 1932); and Seurat et ses amis: La suite de l’impressionnisme (Paris, December 1933–January 1934). Luce did not leave behind a final will and testament, and his surviving papers were destroyed by a flood sometime after 1986, so it is unclear whether the painting remained in Luce’s possession at the time of his death or whether it had already passed to an heir. See email from Denise Bazetoux, independent art historian, to Meghan Gray, NAMA, May 18, 2015, NAMA curatorial files.

[4] See email from Denise Bazetoux, independent art historian, to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, August 27, 2021, NAMA curatorial files.

[5] For the purchaser, see email from Lucy Economakis, Sotheby’s, to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, August 26, 2021, NAMA curatorial files. The seller of record in Sotheby’s archives is Denise Bazetoux; however, by her own account she never owned Study for “The Channel of Gravelines, Petit Fort Philippe” but did advise Jean Bouin-Luce to sell it via Sotheby’s if he wished to part with it. See email from Denise Bazetoux, independent art historian, to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, August 27, 2021, NAMA curatorial files.

[6] Study for “The Channel of Gravelines, Petit Fort Philippe” was offered for sale at Impressionist and Modern Art, Part I, Sotheby’s, New York, May 1, 1996, no. 34, as Le Chenal de Gravelines: Petit Port Philippe, but the highest bidder could not pay for the purchase. As the underbidder, Henry Bloch was offered the painting by Sotheby’s. See email from Emelia Scheidt, Richard L. Feigen and Co., to Meghan Gray, NAMA, April 13, 2015, NAMA curatorial files; and notes from telephone conversation between Henry Bloch and Nicole Myers, NAMA, June 4, 2015, NAMA curatorial files.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Georges Seurat, Study for “The Channel of Gravelines, Petit Fort Philippe,” 1890,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.726.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Georges Seurat, Study for “The Channel of Gravelines, Petit Fort Philippe,” 1890,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.726.4033.

Georges Seurat, The Channel of Gravelines, Petit Fort Philippe, 1890, oil on canvas, 28 7/8 x 36 1/4 in. (73.3 x 92.1 cm), Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, 45.195.

Georges Seurat, The Clipper, 1890, Conté crayon on Michallet paper, 9 1/4 x 12 3/8 in. (23.5 x 31.5 cm), Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 37.718.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Georges Seurat, Study for “The Channel of Gravelines, Petit Fort Philippe,” 1890,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.726.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Georges Seurat, Study for “The Channel of Gravelines, Petit Fort Philippe,” 1890,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.726.4033.

Société des Artistes Indépendants: 21me exposition, Grandes Serres de la Ville de Paris, Cours-La-Reine, Serre B, March 24–April 30, 1905, no. 43, as Étude: Gravelines.

Ausstellung Franzoesischer Kuenstler, Kunstverein München, Munich, September 1906; Frankfurter Kunstverein, Frankfurt, October 1906; Galerie Ernst Arnold, Dresden, November 1906; Badischer Kunstverein, Karlsruhe, December 1906; Württembergischer Kunstverein, Stuttgart, January 1907, no. 101, as Studie: Kanal in Gravelines.

Exposition Georges Seurat (1859–1891), Galerie Bernheim Jeune, Paris, December 14, 1908–January 9, 1909, no. 78, as Étude à Gravelines.

Le Néo-Impressionnisme, Galerie d’Art Braun, Paris, February 25–March 17, 1932, no. 22, as Étude pour “Gravelines”.

Seurat et ses amis: La suite de l’impressionnisme, Galerie des Beaux-Arts, Paris, December 1933–January 1934, no. 64, as Port.

点描の画家たち = Tembyō no gakatachi = Exposition du pointillisme, National Museum of Western Art, Tokyo, April 6–May 26, 1985; Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art, June 4–July 14, 1985, no. 20, as Étude pour “Gravelines, Petit-Fort-Philippe”.

親子で楽しむ西洋美術の名作展 = Exhibition for the Family, Tokyo Metropolitan Teien Art Museum, July 31–September 4, 1988, no. 7.

Seurat at Gravelines: The Last Landscapes, Indianapolis Museum of Art, October 14–November 25, 1990, no. 5, as Study for “The Channel of Gravelines, Petit Fort Philippe”.

Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, June 9–September 9, 2007, no. 19, as The Channel at Gravelines, Petit-Fort-Philippe (Le chenal de Gravelines, Petit-Fort-Philippe).

Magnificent Gifts for the 75th, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, February 13–April 4, 2010, no cat.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Georges Seurat, Study for “The Channel of Gravelines, Petit Fort Philippe,” 1890,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.726.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Georges Seurat, Study for “The Channel of Gravelines, Petit Fort Philippe,” 1890,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.726.4033.

Catalogue de la 21me Exposition, exh. cat. (Paris: Société des Artistes indépendants, 1905), 129, as Étude: Gravelines.

Rudolf Adelbert Meyer, Katalog der Ausstellung Franzoesischer Kuenstler, exh. cat. (Paris: E. Druets Kunstsalon, 1906), 7, 10, 15, as Studie: Kanal in Gravelines.

Exposition Georges Seurat (1859–1891), exh. cat. (Paris: Bernheim Jeune et Cie, 1908), 2, 15, as Etude à Gravelines.

Gustave Coquiot, Les Indépendants, 1884–1920 (Paris: Librairie Ollendorff, [1921]), 23, as Étude: Gravelines.

Gustave Coquiot, Georges Seurat (Paris: Albin Michel, 1924), 120.

Le Néo-Impressionnisme, exh. cat. (Paris: Galerie d’Art Braun et Cie, 1932), 13, as Étude pour “Gravelines”.

Seurat et ses amis: La suite de l’impressionnisme, exh. cat. (Paris, 1933), unpaginated, as Port.

Paul Fierens, “Deux expositions,” Les Nouvelles littéraires, artistiques et scientifiques, no. 585 (December 30, 1933): 9.

Jacques de Laprade, Georges Seurat (Monaco: Les Documents d’Art, 1945), 59, 96, (repro.), as Étude pour le Chenal de Gravelines.

Germain Seligman, The Drawings of Georges Seurat (1946; repr., New York: Curt Valentin, 1947), 40, as Étude: Gravelines.

Hermann Jedding, Seurat (Milan: Uffici Press, [1950]), 2, 20–21, (repro.), as The Canal at Gravelines.

Jacques de Laprade, Seurat (Paris: Éditions Aimery Somogy, 1951), 18, 38, 81, 90, 93, (repro.), as Étude pour le Chenal de Gravelines.

Henri Dorra and John Rewald, Seurat: L’Œuvre peint; Biographie et catalogue critique (Paris: Les Beaux-Arts, 1959), no. 204, pp. 266, 303–04, 309, (repro.), as Étude pour “Gravelines, Petit Fort-Philippe”.

C[ésar] M[ange] de Hauke, Seurat et son œuvre (Paris: Gründ, 1961), no. 207, pp. 1:XXX, 186–87, 235, 239, (repro.); 2:313, 323–25, 331, as Le Chenal de Gravelines: Petit Fort Philippe (Port).

John Russell, Seurat (New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1965), 249, 251, 254.

Henri Perruchot, La vie de Seurat (Paris: Hachette, 1966), 156.

Pierre Courthion, Georges Seurat, trans. Norbert Guterman (New York: Harry N. Abrams, [1968]), 154.

Niels Luning Prak, “Seurat’s Surface Pattern and Subject Matter,” Art Bulletin 53, no. 3 (September 1971): 372.

André Chastel and Fiorella Minervino, L’opera completa di Seurat (Milan: Rizzoli Editore, 1972), no. 208, pp. 110, 116–19, (repro.), as Il Petit Fort Philippe à Gravelines.

André Chastel and Fiorella Minervino, Tout l’œuvre peint de Seurat (Paris: Flammarion 1973), no. 208, pp. 110, 116–19, (repro.), as Étude pour “Gravelines, Petit Fort-Philippe”.

Donald E. Gordon, Modern Art Exhibitions, 1900–1916: Selected Catalogue Documentation (Munich: Prestel, 1974), 2:127, 292, as Étude: Gravelines and Étude à Gravelines.

Catalogue of Important Impressionist and Modern Paintings and Sculpture (London: Sotheby Parke Bernet, December 6, 1978), unpaginated, (repro.), as Le Chenal de Gravelines; Petit Fort Philippe (Port).

Rita Reif, “Auctions: New Records in Antiquities,” New York Times 128, no. 44,067 (December 15, 1978): C27, as The Canal at Gravelines.

Art at Auction: The Year at Sotheby Parke Bernet 1978–79; Two hundred and forty-fifth season (London: Sotheby Parke Bernet, 1979), 94, as Le chenal de Gravelines; Petit Fort Philippe.

Art Price Annual 34 (1979): 634, as Le Chenal de Gravelines: Petit Fort Philippe (Port).

Ellen Wardwell Lee, The Aura of Neo-Impressionism: The W. J. Holliday Collection (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1983), 62, 64.

点描の画家たち = Tembyō no gakatachi = Exposition du pointillisme, exh. cat. (Tokyo: Asahi Shimbun, 1985), 42, (repro.), as Étude pour “Gravelines, Petit-Fort-Philippe”.

Richard Thomson, Seurat (Oxford: Phaidon, 1985), 171, 190, 232n23, (repro.), as Study for “The Gravelines Canal, Petit Fort-Philippe”.

親子で楽しむ西洋美術の名作展 = Exhibition for the Family, exh. cat. (Tokyo: Tokyo Metropolitan Teien Art Museum, 1988), 15, 58, (repro.).

Herbert Wotte, Georges Seurat: Wesen, Werk, Wirkung (Dresden: VEB Verlag der Kunst, 1988), 70.

Catherine Grenier, Seurat: Catalogo completo dei dipinti (Firenze: Cantini Editore, 1990), no. 208, pp. 145, 157, as Studio per Gravelines, piccolo Fort-Philippe.

Ellen Wardwell Lee, Seurat at Gravelines: The Last Landscapes, exh. cat. (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1990), 7, 9, 27, 33–34, 40, 74, (repro.), as Study for “The Channel of Gravelines, Petit Fort Philippe”.

John Russell, “Small Exhibits: Like Jefferson Dining Alone,” New York Times 140, no. 48,444 (December 9, 1990): H36.

Hilton Kramer, “Seurat’s Last Landscapes,” Art and Antiques 8, no. 1 (January 1991): 84.

Alain Madeleine-Perdrillat, Seurat (New York: Rizzoli, 1990), 179, 182.

Françoise Cachin and Robert L. Herbert, Seurat, exh. cat. (Paris: Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 1991), 398, 400.

Anne Distel, Seurat ([Paris]: Chêne, 1991), 23, 136, 155, (repro.), as Étude pour Gravelines, Petit Fort-Philippe.

Catherine Grenier, Seurat: Catalogue complet des peintures (Paris: Bordas, 1991), no. 212, pp. 145, 157, as Étude pour Gravelines, Petit-Fort-Philippe.

Robert L. Herbert, Georges Seurat, 1859–1891, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1991), 349–50, 415, 417, 421.

Possibly Hélène Seyrès, Seurat: Correspondances, témoignages, notes inédites, critiques (Paris: Acropole, 1991), 288.

Michael F. Zimmermann, Seurat and the Art Theory of His Time (Antwerp: Fonds Mercator, 1991), 431–32, (repro.), as Study for “Le Chenal de Gravelines, Petit-Fort-Philippe”.

Sarah Carr-Gomm, Seurat (London: Studio Editions, 1993), 132.

Ellen W. Lee, “Beyond the Blockbuster: Good Exhibitions in Small Packages,” Curator: The Museum Journal 37, no. 3 (September 1994): 176, 178, 183.

Impressionist and Modern Art, Part I (New York: Sotheby’s, May 1, 1996), unpaginated, (repro.), as Le Chenal de Gravelines: Petit Port Philippe.

Kunstpreis Jahrbuch 1996: Deutsche und Internationale Auktionsergebnisse (Munich: Weltkunst Verlag, 1996), 2:357, (repro.), as Le Chenal de Gravelines, Petit Fort Philippe.

Sotheby’s Art at Auction (1996): 79, (repro.), as Le Chenal de Gravelines; Petit Port Philippe.

Rebecca Dimling Cochran and Bobbie Leigh, “100 Top Collectors who have made a difference,” Art and Antiques 28, no. 3 (March 2006): 90.

Bobbie Leigh, “Magnificent Obsession,” Art and Antiques 28, no. 6 (June 2006): 61.

Alice Thorson, “A Tiny Renoir Began Impressive Obsession,” Kansas City Star 127, no. 269 (June 3, 2007): E4.

“Lasting Impressions: A Tribute to Marion and Henry Bloch,” Member Magazine (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (Fall 2007): 11–12.

Steve Paul, “Pretty Pictures: Marion and Henry Bloch’s collection of superb Impressionist masters,” Panache 4, no. 3 (Fall 2007): 20.

Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro. Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 11–12, 16, 104–07, 159, (repro.), as The Channel at Gravelines, Petit-Fort-Philippe (Le chenal de Gravelines, Petit-Fort-Philippe).

“A 75th Anniversary Celebrated with Gifts of 400 Works of Art,” Art Tattler International (February 2010): http://arttattl.ipower.com/archivemagnificentgifts.html, (repro.), as The Channel at Gravelines, Petit Fort-Philippe.

Alice Thorson, “Blochs add to Nelson treasures,” Kansas City Star 130, no. 141 (February 5, 2010): A1, A8, (repro.), as Channel at Gravelines, Petit-Fort-Philippe.

Carol Vogel, “O! Say, You Can Bid on a Johns,” New York Times 159, no. 54,942 (February 5, 2010): C26.

Alice Thorson, “Gift will leave lasting impression,” Kansas City Star 130, no. 143 (February 7, 2010): G1–G2, as Channel at Gravelines.

Thomas M. Bloch, Many Happy Returns: The Story of Henry Bloch, America’s Tax Man (Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons, 2011), 174–75.

Diane Stafford, “Bloch Gift to Go for Nelson Upgrade,” Kansas City Star 135, no. 203 (April 8, 2015): A8.

“Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art officially accessions Bloch Impressionist masterpieces,” Artdaily.org (July 25, 2015): http://artdaily.com/news/80246/Nelson-Atkins-Museum-of-Art-officially-accessions-Bloch-Impressionist-masterpieces.

Julie Paulais, “Le Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art reçoit des tableaux impressionnistes en échange de leurs répliques,” Le Journal des arts (July 30, 2015): https://www.lejournaldesarts.fr/patrimoine/le-nelson-atkins-museum-art-recoit-des-tableaux-impressionnistes-en-echange-de-leurs.

Josh Niland, “The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Acquires a Renowned Collection of Impressionist and Postimpressionist Art,” architecturaldigest.com (July 31, 2015): https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/nelson-atkins-museum-accessions-bloch-art-collection.

Nancy Staab, “Van Gogh is a Go!” 435: Kansas City’s Magazine (September 2015): 76.

Seurat, Van Gogh, Mondrian: Il post-impressionismo in Europa, exh. cat. (Milan: 24 ORE Cultura, 2015), 30.

“Nelson-Atkins to unveil renovated Bloch Galleries of European Art in winter 2017,” Artdaily.org (July 20, 2016): http://artdaily.com/news/88852/Nelson-Atkins-to-unveil-renovated-Bloch-Galleries-of-European-Art-in-winter-2017.

“Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art celebrates generosity of Henry Bloch with new acquisition,” Artdaily.org (October 18, 2016): https://artdaily.cc/news/90923/Nelson-Atkins-Museum-of-Art-celebrates-generosity-of-Henry-Bloch-with-new-acquisition#.XnKATqhKiUk.

Catherine Futter et al., Bloch Galleries: Highlights from the Collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2016), 98, (repro.), as The Channel at Gravelines, Petit-Fort-Philippe.

Kelly Crow, “Museum Rewards Donor with Fake Art to Hang at Home,” Wall Street Journal (January 25, 2017): https://www.wsj.com/articles/museum-rewards-donor-with-fake-art-to-hang-at-home-1485370768.

David Frese, “Bloch savors paintings in redone galleries,” Kansas City Star 137, no. 161 (February 25, 2017): 1A.

Albert Hecht, “Henry Bloch’s Masterpieces Collection to Go On Display at Nelson-Atkins Museum,” Jewish Business News (February 26, 2017): http://jewishbusinessnews.com/2017/02/26/henry-bloch-masterpieces-collection/.

David Frese, “Inside the Bloch Galleries: An interactive experience,” Kansas City Star 137, no. 169 (March 5, 2017): 4D, (repro.), as The Channel at Gravelines, Petit-Fort-Philippe.

“Editorial: Thank you, Henry and Marion Bloch,” Kansas City Star (March 7, 2017), http://www.kansascity.com/opinion/editorials/article137040948.html [repr., in “Thank you, Henry and Marion Bloch,” Kansas City Star 137, no. 172 (March 8, 2017): 16A].

Hampton Stevens, “(Not Actually) 12 Things To Do During The Big 12 Tournament,” Flatland: KCPT’s Digital Magazine (March 9, 2017): http://www.flatlandkc.org/arts-culture/sports/not-actually-12-big-12-tournament/.

Laura Spencer, “The Nelson-Atkins’ Bloch Galleries Feature Old Masterworks and New Technology,” KCUR (March 10, 2017): http://kcur.org/post/nelson-atkins-bloch-galleries-feature-old-masterworks-and-new-technology#stream/0.

Victoria Stapley-Brown, “Nelson-Atkins Museum’s new European art galleries come with a ‘love story,’” Art Newspaper (March 10, 2017): http://theartnewspaper.com/news/museums/nelson-atkins-museum-s-new-european-art-galleries-come-with-a-love-story/.

Harry Bellet, “Don du ciel pour le Musée Nelson-Atkins,” Le Monde (March 13, 2017): http://www.lemonde.fr/arts/article/2017/03/13/don-du-ciel-pour-le-musee-nelson-atkins_5093543_1655012.html/.

Menachem Wecker, “Jewish Philanthropist Establishes Kansas City as Cultural Mecca,” Forward (March 14, 2017): http://forward.com/culture/365264/jewish-philanthropist-establishes-kansas-city-as-cultural-mecca/. [repr., in Menachem Wecker, “Kansas City Collection Is A Chip Off the Old Bloch,” Forward (March 17, 2017): 20–22].

Juliet Helmke, “The Bloch Collection Takes up Residence in Kansas City’s Nelson Atkins Museum,” Blouin ArtInfo International (March 15, 2017): http://www.blouinartinfo.com/news/story/2005267/the-bloch-collection-takes-up-residence-in-kansas-citys.

Louise Nicholson, “How Kansas City got its magnificent museum,” Apollo: The International Art Magazine (April 7, 2017): https://www.apollo-magazine.com/how-kansas-city-got-its-magnificent-museum/.

Lilly Wei, “Julián Zugazagoitia: ‘Museums should generate interest and open a door that leads to further learning,’” Studio International (August 21, 2017): http://studiointernational.com/index.php/julian-zugazagoitia-director-nelson-atkins-museum-of-art-kansas-city-interview.

Robert D. Hershey Jr., “Henry Bloch, H&R Block’s cofounder, dies at 96,” Boston Globe (April 23, 2019): https://www3.bostonglobe.com/metro/obituaries/ 2019/04/23/henry-bloch-block-cofounder/?arc404=true.

Robert D. Hershey Jr., “Henry W. Bloch, Tax-Preparation Pioneer (and Pitchman), Is Dead at 96,” New York Times (April 23, 2019): https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/23/obituaries/henry-w-bloch-dead.html.

Megan McDonough, “Henry Bloch, whose H&R Block became world’s largest tax-services provider, dies at 96,” Washington Post (April 23, 2019): https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/obituaries/henry-bloch-whose-handr-block-became-worlds-largest-tax-services-provider-dies-at-96/2019/04/23/19e95a90-65f8-11e9-a1b6-b29b90efa879_story.html.

Claire Selvin, “Henry Wollman Bloch, Collector and Prominent Benefactor of Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Is Dead at 96,” ArtNews (April 23, 2019): http://www.artnews.com/2019/04/23/henry-bloch-dead-96/.

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “Henry Bloch, co-founder of H&R Block, dies at 96,” Kansas City Star 139, no. 219 (April 24, 2019): 1A.

“Henry Wollman Bloch (1922–2019),” Artforum (April 24, 2019): https://www.artforum.com/news/henry-wollman-bloch-1922-2019-79547.

Frank Morris, “Henry Bloch, Co-Founder Of H&R Block, Dies At 96,” NPR (April 24, 2019): https://www.npr.org/2019/04/24/716641448/henry-bloch-co-founder-of-h-r-block-dies-at-96.

Ignacio Villarreal, “Nelson-Atkins mourns loss of Henry Bloch,” ArtDaily.org (April 24, 2019): http://artdaily.com/news/113035/Nelson-Atkins-mourns-loss-of-Henry-Bloch#.XMB76qR7laQ.

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “H&R Block co-founder, philanthropist Bloch dies,” Cass County Democrat Missourian 140, no. 29 (April 26, 2019): 1A.

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “KC businessman and philanthropist Henry Bloch dies,” Lee’s Summit Journal 132, no. 79 (April 26, 2019): 1A.

Luke Nozicka, “Family and friends remember Henry Bloch of H&R Block,” Kansas City Star 139, no. 225 (April 30, 2019): 4A [repr., in Luke Nozicka, “Family and friends remember Henry Bloch of H&R Block,” Kansas City Star 139, no. 228 (May 3, 2019): 3A].

Eric Adler, “Sold for $3.25 million, Bloch’s home in Mission Hills may be torn down,” Kansas City Star 141, no. 90 (December 16, 2020): 2A.

Kristie C. Wolferman, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A History (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2020), 345.