![]()

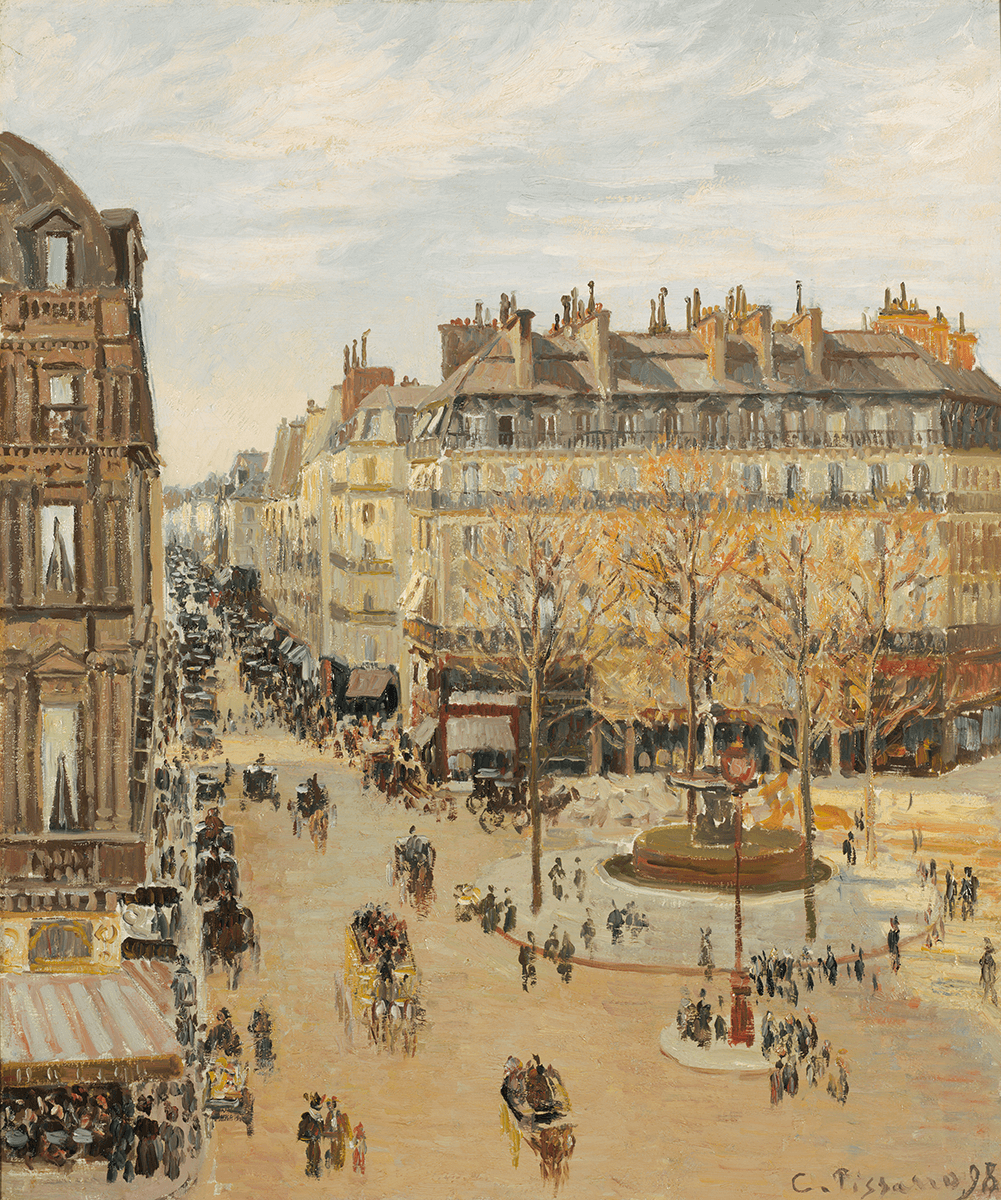

Camille Pissarro, Paris, Rue Saint-Honoré, Sun Effect, Afternoon, 1898

| Artist | Camille Pissarro, French, 1830–1903 |

| Title | Paris, Rue Saint-Honoré, Sun Effect, Afternoon |

| Object Date | 1898 |

| Alternate and Variant Titles | Paris, rue Saint-Honoré, effet de soleil, matin; La Rue Saint-Honoré, après-midi, effet de soleil; Paris, la rue Saint-Honoré, Soleil |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (Unframed) | 25 3/4 x 21 1/2 in. (65.4 x 54.6 cm) |

| Signature | Signed and dated lower right: C. Pissarro. 98 |

| Credit Line | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Gift of Henry W. and Marion H. Bloch, 2015.13.18 |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Camille Pissarro, Paris, Rue Saint-Honoré, Sun Effect, Afternoon, 1898,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.650.5407.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Camille Pissarro, Paris, Rue Saint-Honoré, Sun Effect, Afternoon, 1898,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.650.5407.

Of the seven paintings by Camille Pissarro (1830–1903) in the collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Paris, Rue Saint-Honoré, Sun Effect, Afternoon is the only cityscape; the other six depict life in the Parisian suburbs. This imbalance reflects the artist’s strong preference for the countryside. For most of his five-decade career, rural motifs in the environs of Louveciennes, Éragny, and Pontoise were his chief source of inspiration. Beginning in 1893, however, Pissarro embarked on a series of urban campaigns in Paris, Rouen, Dieppe, and Le Havre at the urging of his longtime dealer Paul Durand-Ruel.1Pissarro had visited Rouen once previously in 1883, but this isolated trip was suggested by his friend Claude Monet (1840–1926) rather than Durand-Ruel. See Claire Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, “Les vues urbaines de Pissarro / Pissarro’s Urban Views,” in Camille Pissarro: Le premier des impressionnistes / The First among the Impressionists, exh. cat. (Paris: Musée Marmottan Monet, 2017), 138, 144. Instead of painting en plein airen plein air (adjective: plein-air): French for “outdoors.” The term is used to describe the act of painting quickly outside rather than in a studio., as was his custom, he stationed his easel at upper-story hotel windows and recorded bird’s-eye views of city streets and quays. These shifts in his working method and subject matter stemmed from physical and financial circumstances. Pissarro suffered from a chronic eye infection, which required that he minimize his exposure to dust and wind.2Pissarro’s doctor prescribed silver nitrate eye drops to mitigate his inflammation and pus. See Camille Pissarro to Dr. Parenteau, February 13, 1897, and Camille Pissarro to Lucien Pissarro, November 22, 1897, in Janine Bailly-Herzberg, ed., Correspondance de Camille Pissarro (Paris: Valhermeil, 1989), 4:327, 409–10, letter nos. 1370, 1477. He also depended on Durand-Ruel for his livelihood and was keen to satisfy his principal backer.3Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, “Les vues urbaines de Pissarro,” 165, 170. Thus, when Durand-Ruel advised him in November 1897 to select a new Parisian quartierquartier: The city of Paris is divided into twenty arrondissements, or districts, each of which comprises four quartiers. to paint, the artist obligingly scouted several prospective locations on the right bank.4See Camille Pissarro to Lucien Pissarro, November 9, 1897, in Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 4:396, no. 1462.

Thanks to the artist’s regular correspondence with his children, a general timeline of his Place du Théâtre Français series can be reconstructed. After spending the Christmas holiday in Éragny, Pissarro returned to Paris on January 5, 1898, and commenced work on two size-30standard-format supports: Commercially prepared supports available through art suppliers, which gained popularity in the nineteenth century during the industrialization of art materials. Available in three formats figure (portrait), paysage (landscape), and marine (marine), these were numbered 1 through 120 to indicate their size. For each numbered size, marine and paysage had two options available: a larger format (haute) and smaller (basse) format. canvases the following day.14Camille Pissarro to Lucien Pissarro, January 6, 1898, in Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 4:425–26, no. 1493. He made steady progress over the next several weeks, reporting on February 22 that he had finished six pictures and begun four others—despite frequent visits from family members and colleagues and the charged political atmosphere surrounding French author Émile Zola’s trial for libel.15Camille Pissarro to Lucien Pissarro, February 22, 1898, in Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 4:453–54, no. 1518. Pissarro’s visitors during those first six weeks included his wife, Julie (January 10–13 and February 6–9), his son Georges (third week of February), and the painter Hippolyte Petitjean (1854–1929) (January 24). He followed Zola’s trial (February 7–23) closely and often discussed the Dreyfus affair in his correspondence. In March, eye complications and bouts of bad weather hampered Pissarro, but by April 11 he had completed all fifteen paintings in the series, three of which took the Rue Saint-Honoré as their primary subject.16See Camille Pissarro to Julie Pissarro, March 5, 1898; Camille Pissarro to Lucien Pissarro, March 7, 1898; and Camille Pissarro to Lucien Pissarro, April 11, 1898, in Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 4:456–59, 469–70, nos. 1521, 1523, 1534. Pissarro had initially intended to offload the entire group onto Durand-Ruel but ultimately reserved three cityscapes for himself. The Nelson-Atkins picture was among the dozen that he shipped to the dealer on April 26 and officially sold to him on May 2, just in time for his June retrospective.17See Camille Pissarro to Paul Durand-Ruel, April 25, 1898; and Camille Pissarro to Lucien Pissarro, April 26, 1898, in Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 4:475–77, nos. 1539–1540. Pissarro’s retrospective was on view from June 1 to 18, 1898, at the Galeries Durand-Ruel.

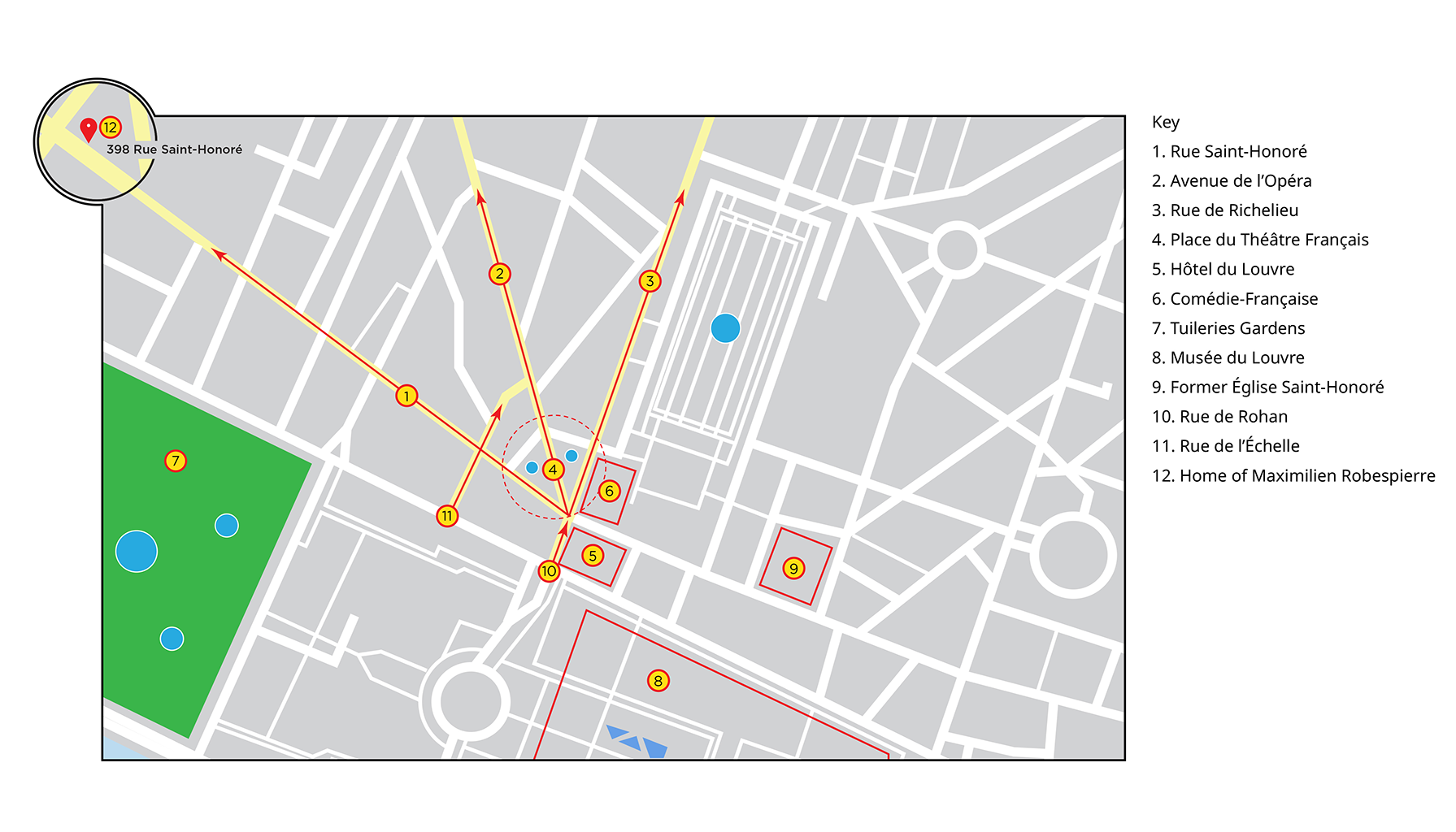

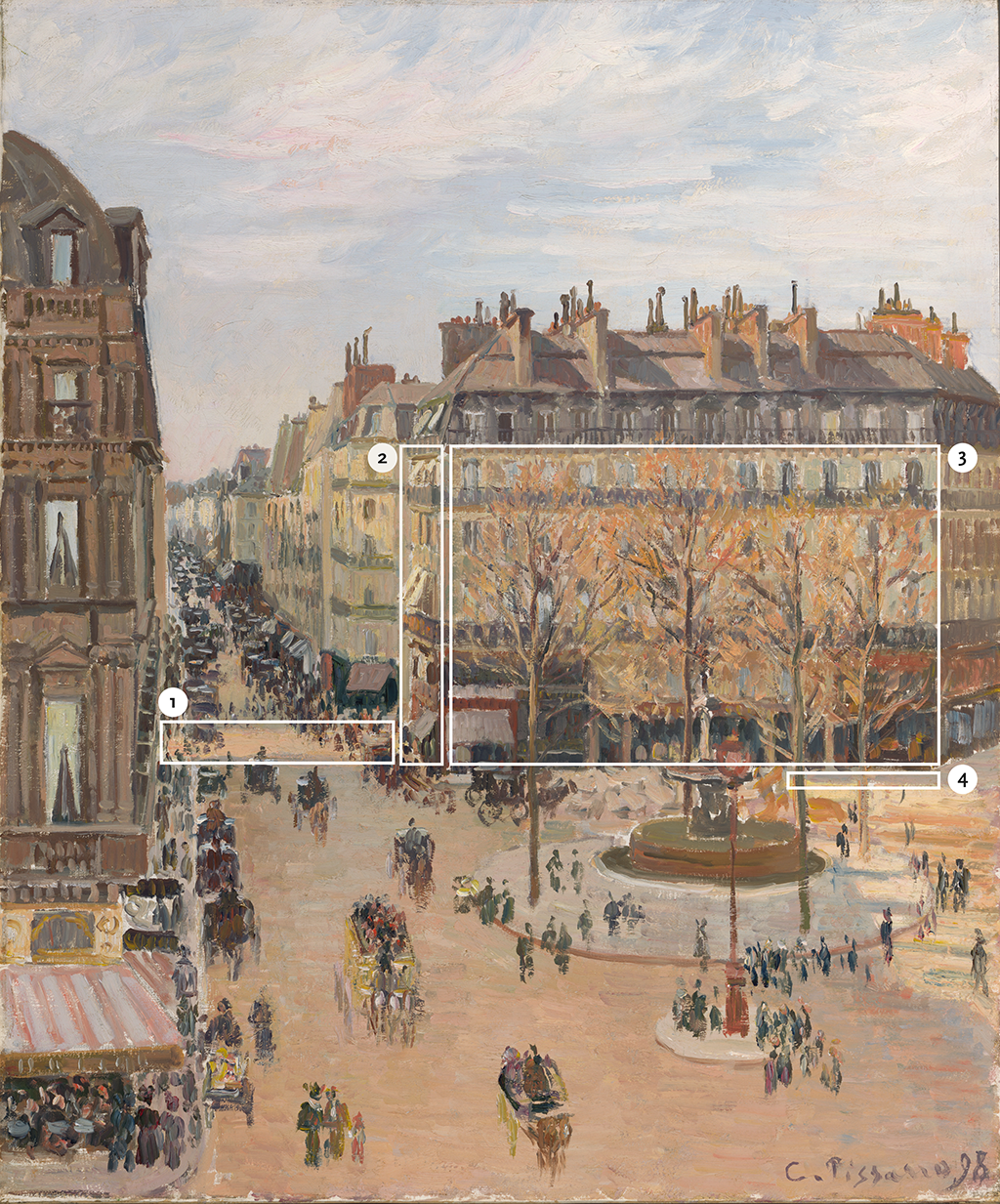

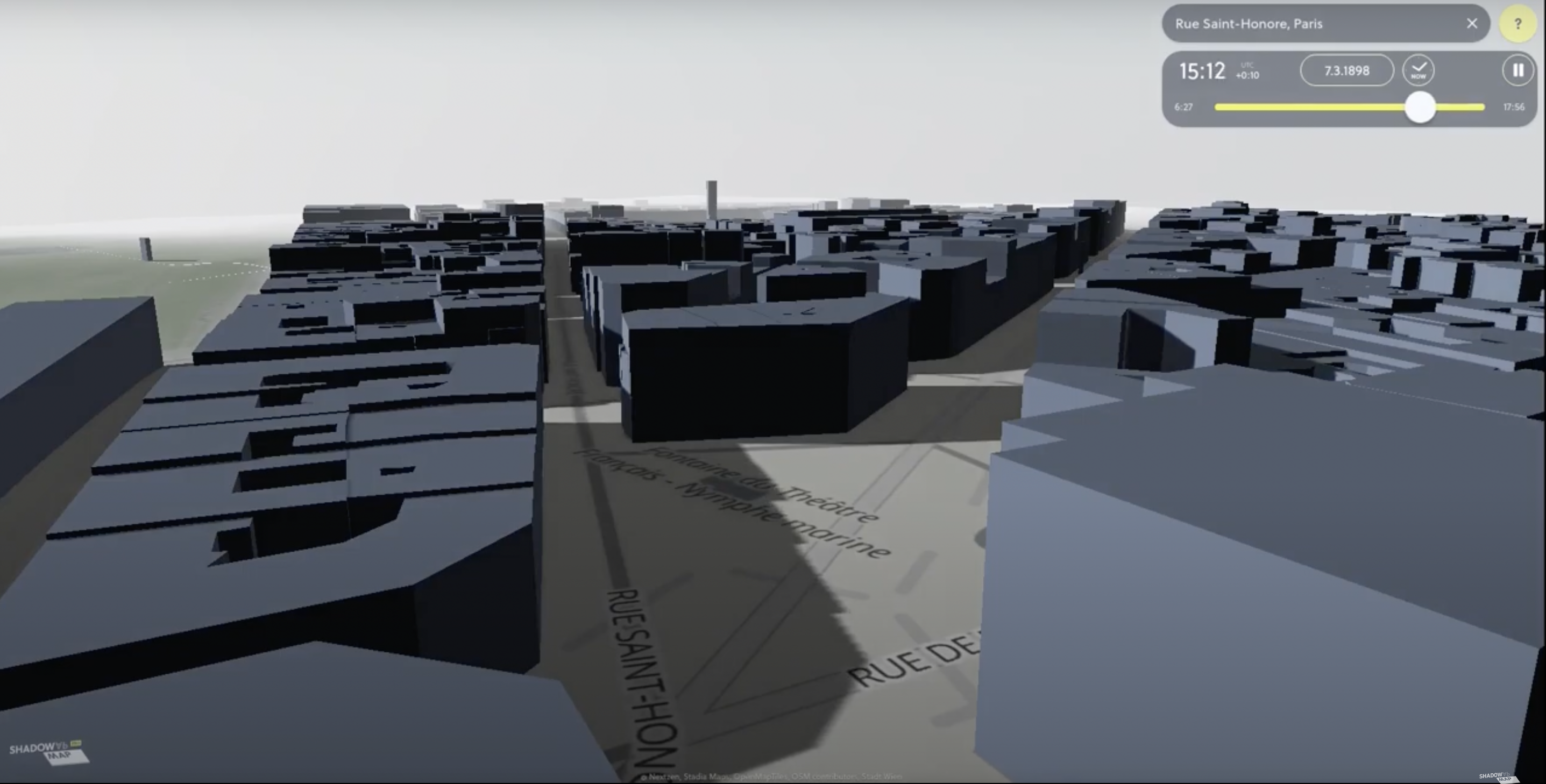

Although the precise order in which Pissarro executed his Place du Théâtre Français series remains speculative, a start date of early March 1898 for the Kansas City painting is supported by both meteorological observations in the artist’s extant letters and solar-mapping tools developed by Shadowmap Technologies GmbH, as discussed below. On March 7, 1898, Pissarro wrote contentedly to his son: “My work is visibly progressing, this pleases me a great deal, the lighting is so splendid, it’s a feast for the eyes!”18Camille Pissarro to Lucien Pissarro, March 7, 1898, in Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 4:457, no. 1523. “Mon travail avance à vue d’œil, cela m’amuse énormément, les lumières sont si splendides, c’est une fête des yeux!” Emphasis added. His delight with the weather was short-lived, however, because two weeks later, on March 21, Pissarro mentioned to Durand-Ruel that the sun had emerged for the first time in days. Taking advantage of its return, he worked late into the afternoon on his “effect of the setting sun” picture, which Janine Bailly-Herzberg has identified as either the Nelson-Atkins scene or a privately owned painting of the Avenue de l’Opéra.19Camille Pissarro to Paul Durand-Ruel, March 21, 1898, in Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 4:461, no. 1526. Pissarro stated: “Je comptais passer rue Lafitte, mais je suis retenu par mon ‘effet de soleil couchant’ assez tard” (“I had intended to stop by the rue Lafitte, but my ‘effect of the setting sun’ kept me [at the hotel] quite late”). On March 26, winter reared its head again, and Paris was blanketed with snow. Pissarro informed his wife: “I was able to finish my two snow effects. I only have three sun effects that drag on.”20Camille Pissarro to Julie Pissarro, March 26, 1898, in Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 4:463, no. 1528. “J’ai pu finir mes deux effets de neige. Je n’ai plus que trois effets de soleil qui traînent en longueur.” The artist was still fretting about the lack of sunshine and his incomplete works on April 1, suggesting that he began Paris, Rue Saint-Honoré in early March 1898 and added the finishing touches in early April.21Camille Pissarro to Lucien Pissarro, April 1, 1898, in Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 4:467, no. 1531.

Fig. 3. Annotated image of Paris, Rue Saint-Honoré, Sun Effect, Afternoon showing: (1) the cross-street Rue de l’Échelle, (2) the southern façade of the central building, (3) the eastern façade of the central building, and (4) the sliver of ground shadow along the eastern façade

Fig. 3. Annotated image of Paris, Rue Saint-Honoré, Sun Effect, Afternoon showing: (1) the cross-street Rue de l’Échelle, (2) the southern façade of the central building, (3) the eastern façade of the central building, and (4) the sliver of ground shadow along the eastern façade

Fig. 5. Detail of the omnibus in Paris, Rue Saint-Honoré, Sun Effect, Afternoon

Fig. 5. Detail of the omnibus in Paris, Rue Saint-Honoré, Sun Effect, Afternoon

Fig. 6. Agence Rol, Horse-Drawn Omnibus: Belleville-Louvre, 1912, photographic negative on glass, 5 1/8 x 7 1/16 in. (13 x 18 cm), Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, EI-13 (144)

Fig. 6. Agence Rol, Horse-Drawn Omnibus: Belleville-Louvre, 1912, photographic negative on glass, 5 1/8 x 7 1/16 in. (13 x 18 cm), Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, EI-13 (144)

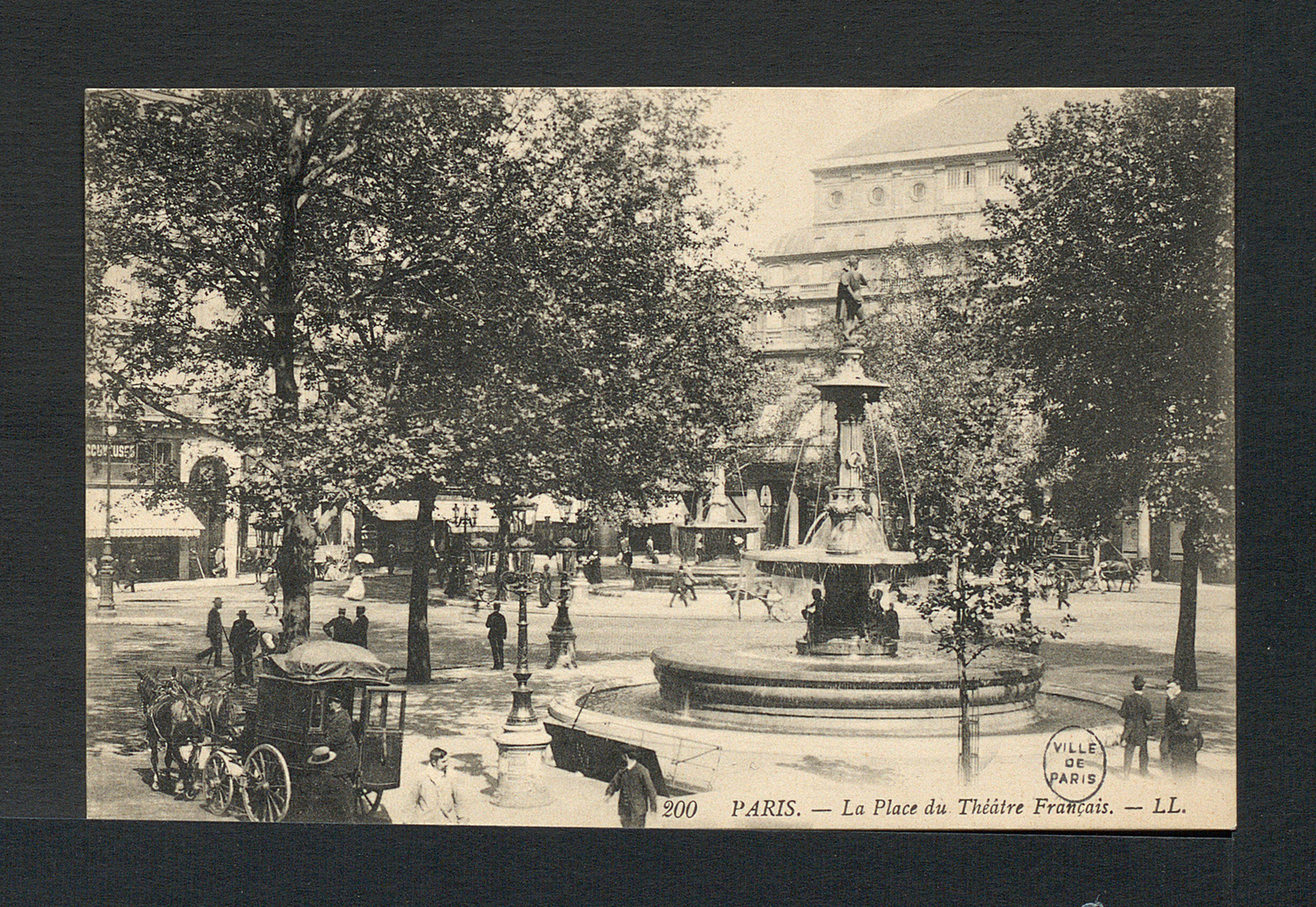

The pedestrian island in the Nelson-Atkins picture was an even more recent development. Engineer and landscape architect Jean Charles Adolphe Alphand (1817–1891), head of the new Service des Promenades et Plantations (parks department) under Napoléon III, superintended the design, construction, and maintenance of Paris’s increasing number of parks, squares, and tree-lined streets, including the Place du Théâtre Français.29For Alphand’s life and career, see Gideon Fink Shapiro, “The Promenades of Paris: Alphand and the Urbanization of Garden Art, 1852–1871” (PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania, 2015). Alphand expounded his approach to urban landscape design in Jean Charles Adolphe Alphand, Les Promenades de Paris: Bois de Boulogne, Bois de Vincennes, parcs, squares, boulevards (Paris: J. Rothschild, 1867–1873). Alphand’s collaborators included fellow landscape architect Jean Pierre Barillet (1824–1875), who sourced the trees seen in the Nelson-Atkins work from municipal nurseries near the Bois de Vincennes and Bois de Boulogne; and Davioud, who designed the fountain that those trees encircle.30The trees were carefully pruned so that their leaves did not obstruct the streetlamps. Alphand’s guidelines specified that all foliage be 3.5 meters or higher above the ground. Alphand further required that all tree roots be covered by iron grilles, though Pissarro opted to omit these grates from the Nelson-Atkins picture. See Shapiro, “The Promenades of Paris,” 60–61, 213–15. The fountain is one of a pair: its sister monument flanks the east side of the Avenue de l’Opéra and appears in other paintings by Pissarro.31See Joachim Pissarro and Claire Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Catalogue critique des peintures / Critical Catalogue of Paintings, trans. Mark Hutchinson and Michael Taylor (Paris: Wildenstein Institute, 2005), nos. 1195, 1197–98, 1201–08, pp. 3:749–55. Davioud submitted a proposal for both fountains in 1867, but the Franco-Prussian WarFranco-Prussian War: The war of 1870–1871 between France (under Napoleon III) and Prussia, in which Prussian troops advanced into France and decisively defeated the French at Sedan. The defeat marked the end of the French Second Empire. For Prussia, the proclamation of the new German Empire at Versailles was the climax of Bismarck’s ambitions to unite Germany. put the project on hold, so they were not realized until 1874.32Gabriel Davioud, architecte (1824–1881), exh. cat. (Alençon, France: Firmin-Didot, 1981), 49. Each one comprises a stone base, marble piedouchepiedouche: Small pedestal that serves as a support for a bust, vase, or statue., and bronze effigy. A sea nymph statue by Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse (1824–1887) crowns the fountain seen in the Nelson-Atkins painting, while a river nymph sculpture by Mathurin Moreau (1822–1912) caps its twin.33For Carrier-Belleuse’s involvement in the sculptural program, see June Ellen Hargrove, “The Life and Work of Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse” (PhD diss., Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, 1976), 165–66. These details are somewhat obscured in Paris, Rue Saint-Honoré by the surrounding foliage and lamppost, but they are discernible in a period postcard of the square (Fig. 7).34The lamppost is also Davioud’s handiwork: he designed this candélabre ordinaire (single, branchless streetlamp) and several other models. See Alphand, Les Promenades de Paris, unnumbered and unpaginated plate titled “Voie publique candélabres.” Here, as in the Kansas City picture, the pedestrian islands facilitate a range of social encounters: people pause to enjoy the shade, chat with other passersby, and hail fiacresfiacre: A small four-wheeled carriage for public hire named after the Hôtel de St. Fiacre in Paris, where such vehicles were first hired out.. Haussmann’s Paris offered many opportunities to casually meet old acquaintances and make new ones, and this aspect of modernity assumes prominence in Pissarro’s Place du Théâtre Français campaign.

Fig. 7. L. L., Paris. La Place du Théâtre Français, early 20th century, postcard, 3 9/16 x 5 1/2 in. (9 x 14 cm), Ville de Paris / Bibliothèque historique

Fig. 7. L. L., Paris. La Place du Théâtre Français, early 20th century, postcard, 3 9/16 x 5 1/2 in. (9 x 14 cm), Ville de Paris / Bibliothèque historique

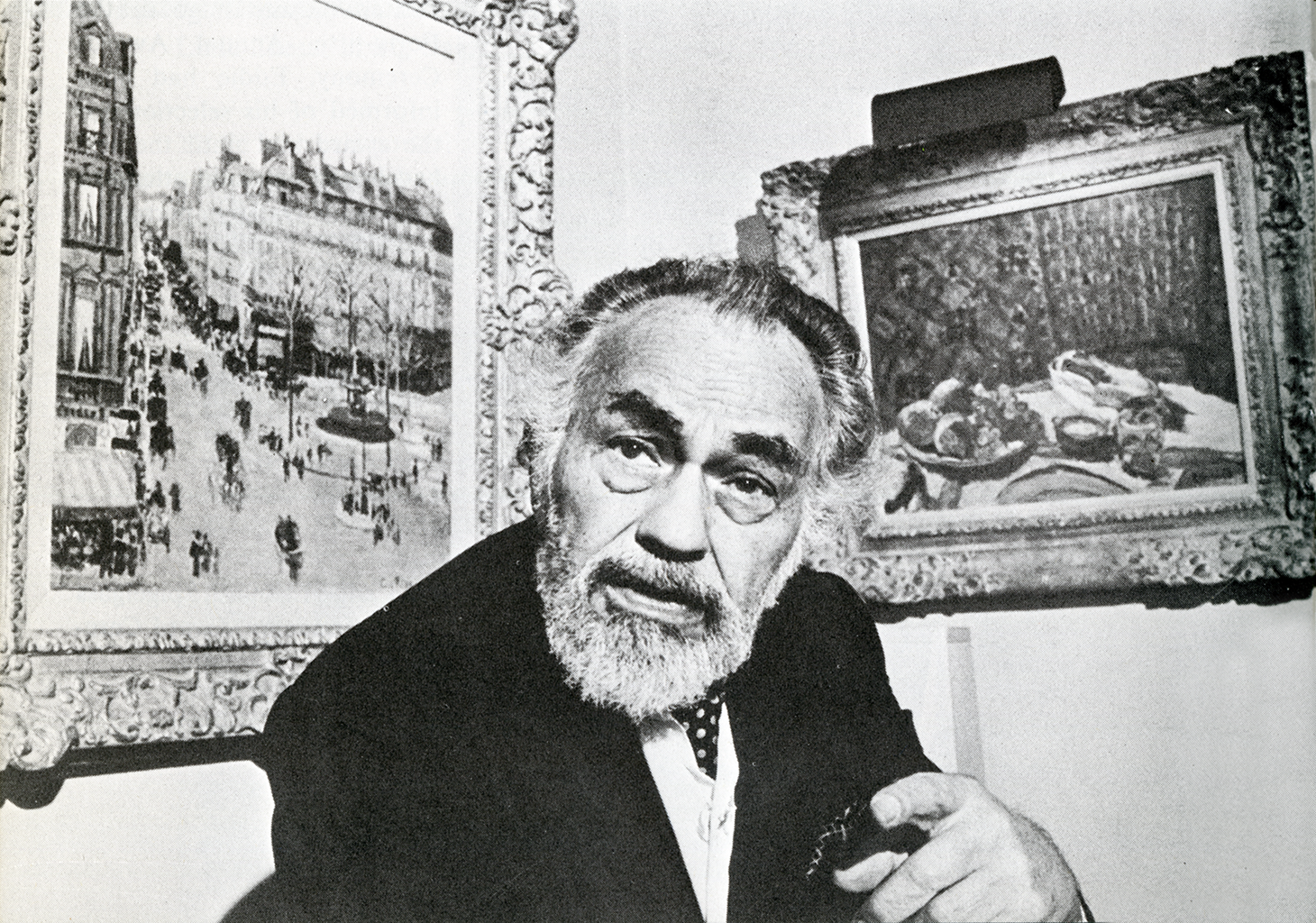

Fig. 8. Publicity photograph of actor Edward G. Robinson for his final film, Soylent Green (1973), reproduced in Edward G. Robinson and Leonard Spigelgass, All My Yesterdays: An Autobiography (New York: Hawthorn Books, 1973), unpaginated plate. © Estate of Edward G. Robinson and Leonard Spigelgass

Fig. 8. Publicity photograph of actor Edward G. Robinson for his final film, Soylent Green (1973), reproduced in Edward G. Robinson and Leonard Spigelgass, All My Yesterdays: An Autobiography (New York: Hawthorn Books, 1973), unpaginated plate. © Estate of Edward G. Robinson and Leonard Spigelgass

Notes

-

Pissarro had visited Rouen once previously in 1883, but this isolated trip was suggested by his friend Claude Monet (1840–1926) rather than Durand-Ruel. See Claire Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, “Les vues urbaines de Pissarro / Pissarro’s Urban Views,” in Camille Pissarro: Le premier des impressionnistes / The First among the Impressionists, exh. cat. (Paris: Musée Marmottan Monet, 2017), 138, 144.

-

Pissarro’s doctor prescribed silver nitrate eye drops to mitigate his inflammation and pus. See Camille Pissarro to Dr. Parenteau, February 13, 1897, and Camille Pissarro to Lucien Pissarro, November 22, 1897, in Janine Bailly-Herzberg, ed., Correspondance de Camille Pissarro (Paris: Valhermeil, 1989), 4:327, 409–10, letter nos. 1370, 1477.

-

Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, “Les vues urbaines de Pissarro,” 165, 170.

-

See Camille Pissarro to Lucien Pissarro, November 9, 1897, in Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 4:396, no. 1462.

-

Pissarro’s previous Parisian campaigns had centered on the Gare Saint-Lazare in the eighth arrondissement (1893 and 1897) and Montmartre in the eighteenth arrondissement (1897).

-

This thirteenth-century church was nationalized in 1789 and largely demolished in 1792; the surviving remnants were destroyed in 1854. See Robert Hénard, La Rue Saint-Honoré de la Révolution à nos jours (Paris: Émile-Paul, 1909), 463. Today, the Ministère de la Culture building occupies the church’s former site.

-

Hénard, La Rue Saint-Honoré, 141–42, 147–49.

-

Hénard, La Rue Saint-Honoré, 415. The corner café with the red-and-white striped awning in the Nelson-Atkins work marks this intersection. For a period illustration of one such barricade, see Richard, 28 Juillet 1830. Première barricade, Rue Saint Honoré, lithograph, 8 1/8 x 11 13/16 in. (20.6 x 30 cm), Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b540007880.

-

Hénard, La Rue Saint-Honoré, 503. The Comédie-Française is not visible in the Nelson-Atkins picture but appears in several other works from the same series, such as Camille Pissarro, Place du Théâtre Français, 1898, oil on canvas, 29 x 36 in. (73.7 x 91.4 cm), Minneapolis Institute of Art, 18.19.

-

The hotel switched from gas to electric lighting prior to 1894. See Henri Maréchal, L’Éclairage à Paris: Étude technique des divers modes d’éclairage employés à Paris (Paris: Librairie polytechnique Baudry et Cie, 1894), 366–67.

-

This sign has since been removed from the building. Only the smaller Hôtel du Louvre sign remains today.

-

Paris en huit jours: Guide offert par le Grand Hôtel Terminus de la Gare Saint-Lazare (Paris: P. Mouillot, [1901]), 36. For Pissarro’s rate, see Camille Pissarro to Lucien Pissarro, January 8, 1898, in Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 4:427, no. 1494.

-

See Camille Pissarro to Lucien Pissarro, December 15 and 21, 1897, in Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 4:417–20, nos. 1489–90. In the latter, Pissarro states: “Je vais avoir des frais considérables, mais Durand a l’air de m’y encourager” (“My costs will be substantial, but Durand seems like he will help me”).

-

Camille Pissarro to Lucien Pissarro, January 6, 1898, in Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 4:425–26, no. 1493.

-

Camille Pissarro to Lucien Pissarro, February 22, 1898, in Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 4:453–54, no. 1518. Pissarro’s visitors during those first six weeks included his wife, Julie (January 10–13 and February 6–9), his son Georges (third week of February), and the painter Hippolyte Petitjean (1854–1929) (January 24). He followed Zola’s trial (February 7–23) closely and often discussed the Dreyfus affair in his correspondence.

-

See Camille Pissarro to Julie Pissarro, March 5, 1898; Camille Pissarro to Lucien Pissarro, March 7, 1898; and Camille Pissarro to Lucien Pissarro, April 11, 1898, in Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 4:456–59, 469–70, nos. 1521, 1523, 1534.

-

See Camille Pissarro to Paul Durand-Ruel, April 25, 1898; and Camille Pissarro to Lucien Pissarro, April 26, 1898, in Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 4:475–77, nos. 1539–1540. Pissarro’s retrospective was on view from June 1 to 18, 1898, at the Galeries Durand-Ruel.

-

Camille Pissarro to Lucien Pissarro, March 7, 1898, in Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 4:457, no. 1523. “Mon travail avance à vue d’œil, cela m’amuse énormément, les lumières sont si splendides, c’est une fête des yeux!” Emphasis added.

-

Camille Pissarro to Paul Durand-Ruel, March 21, 1898, in Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 4:461, no. 1526. Pissarro stated: “Je comptais passer rue Lafitte, mais je suis retenu par mon ‘effet de soleil couchant’ assez tard” (“I had intended to stop by the rue Lafitte, but my ‘effect of the setting sun’ kept me [at the hotel] quite late”).

-

Camille Pissarro to Julie Pissarro, March 26, 1898, in Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 4:463, no. 1528. “J’ai pu finir mes deux effets de neige. Je n’ai plus que trois effets de soleil qui traînent en longueur.”

-

Camille Pissarro to Lucien Pissarro, April 1, 1898, in Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 4:467, no. 1531.

-

Shadowmap combines data from OpenStreetMap (OSM) and SunCalc to create maps with realistic buildings and solar shadows. Buildings are plotted as blocks, meaning the application does not account for sloped roofs when projecting shadows. See https://shadowmap.org for further details. I thank Simon Mulser, cofounder of Shadowmap, for his kind assistance with this project.

-

According to descendants of Pissarro’s dealer, the Nelson-Atkins picture is listed as Paris, rue Saint-Honoré, effet de soleil, matin (Paris, Rue Saint-Honoré, Sun Effect, Morning) in Durand-Ruel’s stockbooks. See Paul-Louis Durand-Ruel and Flavie Durand-Ruel to Nicole Myers, NAMA, January 11, 2016, NAMA curatorial files. It seems that Durand-Ruel confused the Kansas City picture with another painting of the Rue Saint-Honoré in the collection of Ordrupgaard in Charlottenlund, Denmark, which depicts a morning scene.

-

Scientists at the Montsouris Observatory in Paris recorded a sunrise of 6:32 a.m. and a sunset of 5:51 p.m. on March 7, 1898. See Annuaire de l’Observatoire municipal de Montsouris pour l’année 1898 (Paris: Gauthier-Villars et fils, 1898), 7. Paris operates on Central European Time (CET) today, but in 1898 the city still privileged the Paris meridian over the Greenwich meridian, which meant that their time zone was 9 minutes and 21 seconds behind Greenwich Mean Time (GMT). See Vanessa Ogle, The Global Transformation of Time, 1870–1950 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015), 38–41. The Shadowmap video accounts for this historical zone and reflects local time in Paris.

-

For Davioud’s original sketch of the îlot, see Gabriel Jean Antoine Davioud, “Rue Saint-Honoré 255–257,” in “Expropriations de 1852–1854 pour le prolongement de la rue de Rivoli [Recueil de dessins],” vol. 2, fol. 38, Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris, CP 3369.

-

Masha Belenky, Engine of Modernity: The Omnibus and Urban Culture in Nineteenth-Century Paris (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2019), 15–18. A deck seat cost fifteen centimes, whereas an enclosed seat cost thirty centimes.

-

Belenky, Engine of Modernity, 20–22.

-

By 1878, the demand for public transport was such that La Compagnie générale des omnibus added a forty-passenger vehicle to its fleet. Nevertheless, overcrowding remained a problem, which Pissarro experienced firsthand. As he related in one letter: “Je voulais aller aujourd’hui dimanche à la recherche de motifs à Passy et Trocadéro, mais il y a un tel monde aux omnibus à cause du beau soleil que j’y renonce.” See Camille Pissarro to Georges Pissarro, November 14, 1897, in Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 4:403, no. 1468.

-

For Alphand’s life and career, see Gideon Fink Shapiro, “The Promenades of Paris: Alphand and the Urbanization of Garden Art, 1852–1871” (PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania, 2015). Alphand expounded his approach to urban landscape design in Jean Charles Adolphe Alphand, Les Promenades de Paris: Bois de Boulogne, Bois de Vincennes, parcs, squares, boulevards (Paris: J. Rothschild, 1867–1873).

-

The trees were carefully pruned so that their leaves did not obstruct the streetlamps. Alphand’s guidelines specified that all foliage be 3.5 meters or higher above the ground. Alphand further required that all tree roots be covered by iron grilles, though Pissarro opted to omit these grates from the Nelson-Atkins picture. See Shapiro, “The Promenades of Paris,” 60–61, 213–15.

-

See Joachim Pissarro and Claire Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Catalogue critique des peintures / Critical Catalogue of Paintings, trans. Mark Hutchinson and Michael Taylor (Paris: Wildenstein Institute, 2005), nos. 1195, 1197–98, 1201–08, pp. 3:749–55.

-

Gabriel Davioud, architecte (1824–1881), exh. cat. (Alençon, France: Firmin-Didot, 1981), 49.

-

For Carrier-Belleuse’s involvement in the sculptural program, see June Ellen Hargrove, “The Life and Work of Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse” (PhD diss., Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, 1976), 165–66.

-

The lamppost is also Davioud’s handiwork: he designed this candélabre ordinaire (single, branchless streetlamp) and several other models. See Alphand, Les Promenades de Paris, unnumbered and unpaginated plate titled “Voie publique candélabres.”

-

Stransky, a conductor for the New York Philharmonic, purchased Paris, Rue Saint-Honoré from Durand-Ruel on February 20, 1917, and returned it on April 20, 1917.

-

Robinson’s first silent film was The Bright Shawl (1923), and his first talkie was The Hole in the Wall (1929). Michael Frank, “Edward G. Robinson: Sterling Collection for the Star of Little Caesar and Double Indemnity,” Architectural Digest 47, no. 4 (April 1990): 181.

-

See The Gladys Lloyd Robinson and Edward G. Robinson Collection, exh. cat. (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum, 1956), nos. 39–43.

-

Robinson once remarked of his collection: “Sometimes late at night, when the house is quiet, and the last guest has gone, I go into my living room and sit down among these quiet friends, and we study each other very gravely, and I hope with mutual pleasure.” Jane Robinson, Edward G. Robinson’s World of Art (New York: Harper and Row, 1971), 116.

-

Robinson paid his ex-wife one-half the insurance value of those fourteen artworks. See Roland Balaÿ to Edward G. Robinson, January 18, 1957, M. Knoedler and Co. Records, approximately 1848–1971, The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, 2012.M.54, Series VI, Box 985, Folder 5.

-

I am grateful to Danielle Hampton Cullen, project assistant, NAMA, for this discovery.

-

Edward G. Robinson and Leonard Spigelgass, All My Yesterdays: An Autobiography (New York: Hawthorn Books, 1973), 15.

Technical Entry

Technical entry forthcoming.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Camille Pissarro, Paris, Rue Saint-Honoré, Sun Effect, Afternoon, 1898,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.650.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Camille Pissarro, Paris, Rue Saint-Honoré, Sun Effect, Afternoon, 1898,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.650.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Camille Pissarro, Paris, Rue Saint-Honoré, Sun Effect, Afternoon, 1898,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.650.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Camille Pissarro, Paris, Rue Saint-Honoré, Sun Effect, Afternoon, 1898,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.650.4033.

Purchased from the artist by Durand-Ruel, Paris, stock no. L4635, as Paris, rue Saint-Honoré, effet de soleil, matin [sic], May 2, 1898–February 20, 1917 [1];

Purchased from Durand-Ruel, New York, stock no. 3800, by Josef Stransky (1872–1936), New York, February 20–April 20, 1917 [2];

Purchased from Stransky by Durand-Ruel, New York, stock no. 4078, April 20, 1917–September 23, 1920 [3];

Purchased from Durand-Ruel by Henry Douglas Hughes (1869–1928), Philadelphia, September 23, 1920;

With Marie Sterner Gallery, New York, by May 16, 1930–at least June 8, 1934 [4];

Purchased from Marie Sterner Gallery, probably through Sam Salz, by Gladys Lloyd (née Cassell, 1895–1971) and Edward G. (1893–1973) Robinson, Beverly Hills, after July 8, 1934–1956 [5];

Edward G. Robinson (1893–1973), Beverly Hills, 1956–January 26, 1973 [6];

Inherited by his wife, Jane Robinson (née Bodenheimer, 1919–1991), January 26–April 3, 1973 [7];

Purchased from Jane Robinson by Armand Hammer, through Knoedler and Co., New York, on joint account with Acquavella Galleries, New York, April 3, 1973 [8]

Purchased from Acquavella Galleries by Alex Reid and Lefèvre Ltd., London, stock no. 46/73, by November 1, 1973–December 1976 [9];

Purchased from Reid and Lefèvre by Cynthia Wood (d. 1993), Santa Barbara, CA, December 1976–December 30, 1982;

Purchased from Wood, through John and Paul Herring and Co., New York, by Marion (née Helzberg, 1931–2013) and Henry (1922–2019) Bloch, Shawnee Mission, KS, December 30, 1982–June 15, 2015;

Their gift to the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 2015.

Notes

[1] Durand-Ruel purchased the painting from Pissarro under the title Paris, rue Saint-Honoré, effet de soleil, matin, not “après-midi”; see email from Paul-Louis Durand-Ruel and Flavie Durand-Ruel, Durand-Ruel et Cie., Paris, to Nicole Myers, NAMA, January 11, 2016, NAMA curatorial file. The painting was exhibited at Durand-Ruel, Paris, in April 1904, as belonging to “M. Lebeau,” a name sometimes used by Paul Durand-Ruel when he lent paintings from his personal collection. However, the painting was entered as stock into Durand-Ruel, Paris, from May 2, 1898 to February 20, 1917. The painting was transferred from Durand-Ruel, Paris, to Durand-Ruel, New York, in 1914. Durand-Ruel, New York, stock no. 3800. See email from Paul-Louis Durand-Ruel and Flavie Durand-Ruel, Durand-Ruel et Cie, Paris, to Nicole Myers, NAMA, January 11, 2016, NAMA curatorial files.

[2] See email from Paul-Louis Durand-Ruel and Flavie Durand-Ruel, Durand-Ruel et Cie, Paris, to Nicole Myers, NAMA, January 11, 2016, NAMA curatorial files.

[3] See email from Paul-Louis Durand-Ruel and Flavie Durand-Ruel, Durand-Ruel et Cie, Paris, to Nicole Myers, NAMA, January 11, 2016, NAMA curatorial files.

[4] See letter from Marie Sterner to Louis Earle Rowe, Rhode Island School of Design, May 16, 1930, proposing the purchase of the painting by the museum. According to the letter, Sterner was acting as an agent for another owner. This may have been Hannah Curnuck Hughes (b. ca. 1885), widow of Henry D. Hughes, who often consigned paintings to Sterner. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D. C., Clayton-Liberatore Gallery records and papers, 1899-1977, Marie Sterner Gallery subset, folder “Sterner, M. Rhode Is. School of Design.” See also https://www.nga.gov/collection/provenance-info.20330.html.

[5] See the publicity photo of Edward G. Robinson taken in 1934 featuring the painting. Along the bottom of the photo it reads: copyright 1934 Vitagraph Inc. Property of Vintagraph Inc. Photograph, gift of Harold Sterner, 41919, Frick Art Reference Library, New York (FARL) negative. Robinson purchased the painting shortly after Marie Sterner lent it to the California Palace of the Legion of Honor, San Francisco, from June 8 to July 8, 1934.

[6] Gladys and Edward G. Robinson divorced in 1956. In the divorce proceedings, the couple sold most of their art collection, with the exception of fourteen paintings (including the Nelson-Atkins canvas) which were retained by Edward. See letter from Knoedler and Co., New York, to Edward G. Robinson, January 18, 1957, copy in NAMA curatorial files. See also M. Knoedler and Co. records, approximately 1848–1971. Series VI. Correspondence, box 985, Folder 5, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles. In 1958, Robinson married his second wife, Jane Bodenheimer.

[7] A publicity photo of Robinson taken in 1973 for his upcoming film Soylent Green features the Nelson-Atkins painting. This was Robinson’s final film appearance as he died on January 26, twelve days after the completion of filming; see photograph in Edward G. Robinson and Leonard Spigelgass, All My Yesterdays: An Autobiography (New York: Hawthorn Books, 1973), unpaginated, (repro.), as La Rue St. Honoré.

[8] In his will, Robinson left his wife Jane his entire art collection, including the Pissarro, The Dead Tree. The entire collection was purchased by oil tycoon Armand Hammer, through his firm Knoedler and Co., New York, on April 3, 1973; see “Knoedler Pays 5-Million For Robinson Collection,” New York Times (April 4, 1973): 36, and Alan L. Gansberg, Little Caesar: A Biography of Edward G. Robinson (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2004), 257. Acquavella Gallery, New York, also purchased the collection in conjunction with Armand Hammer; see Peter Aspden, “Lunch with the FT: William Acquavella,” Financial Times (September 30, 2011).

[9] See the Alex Reid and Lefèvre Ltd label on the painting’s backing board, lower middle, encapsulated white rectangular with blue border, handwritten in black marker: 64/73. This information was confirmed via a similar label found on the verso of a painting at the Art Institute of Chicago; see Gloria Groom et al., Pissarro: Paintings and Works on Paper at the Art Institute of Chicago (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2015), no. 2, https://publications.artic.edu/pissarro/sites/publications. artic.edu.pissarro/files/ file_assets/Cat.2VRSstr26351_PDF.pdf.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Camille Pissarro, Paris, Rue Saint-Honoré, Sun Effect, Afternoon, 1898,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.650.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Camille Pissarro, Paris, Rue Saint-Honoré, Sun Effect, Afternoon, 1898,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.650.4033.

Camille Pissarro, Rue Saint-Honoré, Afternoon, Effect of Rain, 1897, oil on canvas, 31 7/8 x 25 5/8 in. (81 x 65 cm), Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid.

Camille Pissarro, Rue Saint-Honoré, Morning, Effect of Sunlight, 1898, oil on canvas, 25 3/4 x 21 1/4 in. (65.5 x 54 cm), Ordrupgaard, Charlottenlund.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Camille Pissarro, Paris, Rue Saint-Honoré, Sun Effect, Afternoon, 1898,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.650.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Camille Pissarro, Paris, Rue Saint-Honoré, Sun Effect, Afternoon, 1898,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.650.4033.

Œuvres récentes de Camille Pissarro, Galerie Durand-Ruel, Paris, June 1–18, 1898, no. 22, as Rue Saint-Honoré. Après-midi, effet de soleil.

Exposition de l’Œuvre de Camille Pissarro, Galeries Durand-Ruel, Paris, April 7–30, 1904, no. 110, as La Rue Saint-Honoré.

Pissarro, Galerie Durand-Ruel, Paris, March 1908, no. 7, no cat.

Paintings by French Impressionists, Detroit Museum of Art, Detroit, November 1915, no. 38, as Rue St. Honore [sic], Paris.

Exhibition of paintings lent by Durand-Ruel, Brooks Reed Gallery, Boston, December 1916–January 1917, no cat.

Paintings by Pissarro, Durand-Ruel Galleries, New York, February 3–17, 1917, no. 5, no cat.

Exhibition of paintings lent by Durand-Ruel, Mattatuck Historical Society, Waterbury, CT, October–November, 1919, no cat.

A Group of French Paintings from Courbet down to and including the Contemporary Moderns, Albright Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY, November 16–December 14, 1930, no. 56, as Rue St. Honore [sic].

Exhibition of French Painting from the Fifteenth Century to the Present Day, California Palace of the Legion of Honor, San Francisco, June 8–July 8, 1934, no. 132, as Rue Saint Honoré.

The Gladys Lloyd Robinson and Edward G. Robinson Collection, Los Angeles County Museum, September 11–November 11, 1956; California Palace of the Legion of Honor, San Francisco, November 30, 1956–January 13, 1957, no. 42, as Rue St. Honoré.

Important XIX and XX Century Paintings, Lefevre Gallery, London, November 1–December 22, 1973, no. 13, as La Rue Saint-Honoré, Effet de Soleil, Après-Midi.

Le Centenaire de l’Impressionnisme, Ginza Matsuzakaya, Tokyo, July 25–August 11, 1974; Sapporo Matsuzakaya, Sapporo, Japan, August 17–28, 1974; Osaka Matsuzakaya, Osaka, Japan, September 5–17, 1974; Le Musée Préfectoral de Yamaguchi, Yamaguchi, Japan, September 20–30, 1974; Nagoya Matsuzakaya, Nagoya, Japan, October 3–15, 1974; Shizuoka Matsuzakaya, Shizuoka, Japan, October 17–29, 1974; Ueno Matsuzakaya, Ueno, Japan, October 31–November 12, 1974, no. 43, as La rue Saint-Honoré, Effet de Soleil, Après-midi.

The Bloch Collection, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, June–August 1982, no cat.

Paris Cafés: Their Role in the Birth of Modern Art, Wildenstein, New York, November 13–December 20, 1985, unnumbered, as The Rue Saint-Honoré in Afternoon Sunlight.

Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, June 9–September 9, 2007, no. 8, as Rue Saint-Honoré, Sun Effect, Afternoon (La rue Saint-Honoré, effet de soleil, après-midi).

References

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Camille Pissarro, Paris, Rue Saint-Honoré, Sun Effect, Afternoon, 1898,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.650.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Camille Pissarro, Paris, Rue Saint-Honoré, Sun Effect, Afternoon, 1898,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.650.4033.

Exposition d’œuvres récentes de Camille Pissarro, exh. cat. (Paris: A. Marty et H. Floury, 1898), unpaginated, as Rue Saint-Honoré.–Matin, effet de soleil.

Arsène Alexandre, “Vues de Paris de M. Pissarro,” Le Figaro, no. 154 (June 3, 1898): 4.

Possibly Georges Lecomte, “Camille Pissarro,” Les Droits de l’homme (June 4, 1898).

Eugene Hoffman, “Les Petits salons, Camille Pissarro,” Le Journal des Artistes (June 5, 1898): 2311.

Possibly “Ausstellungen,” Frankfurter Zeitung (June 14, 1898).

Possibly F. Jourdain, “Les Hommes du Jour, Camille Pissarro,” L’éclair (June 18, 1898).

Georges Lecomte, “Camille Pissarro,” Revue Populaire des Beaux-Arts 22, no. 35 (June 18, 1898): 43.

Gustave Geffroy, “Camille Pissarro,” Le Journal Quotidien, Littéraire, Artistique et Politique 7, no. 2007 (June 25, 1898): 2 [repr., in Gustave Geffroy, La Vie Artistique, vol. 6, Eau-forte de Camille Pissarro (Paris: H. Floury, 1900), 183–85].

Possibly Ch. Snabilie, “De Impressionisten, III, Camille Pissarro,” De Amsterdammer Week-blad voor Nederland (August 21, 1898).

“Art Moderne,” Mercure de France 27, no. 103 (July 1898): 280.

Possibly F.-A. Bridgmann, “L’Anarchie dans l’art impressionnisme-symbolisme,” L’anarchie dans l’art (1898).

Catalogue de l’Exposition de l’Œuvre de Camille Pissarro, exh. cat. (Paris: Trève, 1904), 19, as La Rue Saint-Honoré.

Pissarro (Paris: Galerie Durand-Ruel, 1908).

Catalogue of an Exhibition of Paintings by French Impressionists, exh. cat. (Detroit: Detroit Museum of Art, 1915), unpaginated, as Rue St. Honore [sic], Paris.

Paintings by Pissarro (New York: Durand-Ruel Galleries, 1917).

Catalog of Exhibitions Commemorating the Twenty-Fifth Anniversary of the Opening of Albright Art Gallery (New York: The Buffalo Fine Arts Academy, 1930), 15, as Rue St. Honore [sic].

Exhibition of French Painting from the Fifteenth Century to the Present Day, exh. cat. (San Francisco: California Palace of the Legion of Honor, 1934), 57, (repro.), as Rue Saint Honoré.

Ludovic Rodo Pissarro and Lionello Venturi, Camille Pissarro, Son Art—Son Œuvre (Paris: Paul Rosenberg, 1939), no. 1021, pp. 1:223, 2:204, (repro.), as La Rue Saint-Honoré, Effet de Soleil, Après-Midi.

John Rewald, “Pissarro’s Paris and His France,” Art News 42, no. 2 (March 1–14, 1943): 16, (repro.), as Rue St. Honore [sic].

John Rewald and Lucien Pissarro, ed., Camille Pissarro, Letters to His Son Lucien (1943; repr., Boston: MFA Publications, 2002), 9, 317, (repro.), as La rue Saint-Honoré, Paris.

The Gladys Lloyd Robinson and Edward G. Robinson Collection, exh. cat. (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum, 1956), unpaginated, (repro.), and Rue St. Honoré.

John Rewald, Camille Pissarro, 1st ed. (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1963), 150.

Jane Robinson, Edward G. Robinson’s World of Art (New York: Harper and Row, 1971), 20–21, 99, (repro.), as La Rue Saint-Honore [sic], Effet de Soleil, Apres-Midi [sic] (The Rue Saint-Honore [sic] in the Afternoon Sunlight).

“Knoedler Pays 5-Million For Robinson Collection,” New York Times 122, no. 42,074 (April 4, 1973): 36.

Edward G. Robinson, All My Yesterdays: An Autobiography (New York: New American Library, 1973), unpaginated, (repro.), as La Rue St. Honoré.

Important XIX and XX Century Paintings, exh. cat. (London: Lefevre Gallery, 1973), 28–29, (repro.), as La Rue Saint-Honoré, effet de Soleil, après-midi.

Diana Hildreth, “XIX and XX Century Paintings,” Arts Review 25, no. 23 (November 3, 1973): 786, (repro.), as La Rue Saint-Honoré, effet de Soleil, après-midi.

William Allan, “Art and Antiques in London: The Summer Scene,” Connoisseur, no. 748 (June 1974): 135, (repro.), as La Rue Saint-Honoré, effet de Soleil Après-midi.

François Daulte, Le Centenaire de l’Impressionnisme, exh. cat. (Tokyo: Ginza Matsuzakaya, 1974), unpaginated, (repro.), as La rue Saint-Honoré. Effet de Soleil, Après-midi.

Alex Reid and Lefevre, 1926–1976 (London: Lefevre Gallery, 1976), 31, 106–07, (repro), as La Rue Saint-Honoré, effet de soleil, après-midi.

Janine Bailly-Herzberg ed., Correspondence de Camille Pissarro (Paris: Editions du Valhermeil, 1980), 1:49.

“The Bloch Collection,” Gallery Events (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) (June–August 1982): unpaginated.

Georges Bernier, Paris Cafés: Their role in the birth of Modern Art, exh. cat. (New York: Wildenstein, 1985), 74, 96, 120, (repro.), as La Rue Saint-Honoré – Effet de Soleil and The Rue Saint-Honoré in Afternoon Sunlight.

Christopher Lloyd, ed., Studies on Camille Pissarro (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1986), 113n1.

Janine Bailly-Herzberg, ed., Correspondence de Camille Pissarro (Paris: Editions du Valhermeil, 1989), 4:476, Rue Saint-Honoré, effet de soleil après-midi.

Ludovico Rodo Pissarro and Lionello Venturi, Camille Pissarro, Son Art—Son Œuvre, 2nd rev. ed (San Francisco: Alan Wofsy Fine Arts, 1989), no. 1021, pp. 1:223, 2:unpaginated, (repro.), as La Rue Saint-Honoré, Effet de Soleil, Après-Midi.

Richard Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, The Impressionist and the City: Pissarro’s Series Paintings, ed. MaryAnne Stevens, exh. cat. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1992), 81–82, 87, (repro.), as Rue Saint-Honoré: Sun Effect, Afternoon and Rue Saint-Honoré, effet de soleil, après-midi.

Mikael Wivel, Ordrupgaard Selected Works (Copenhagen: Ordrupgaard, 1993), unpaginated.

Christofer Conrad, Renoir, Gauguin, Degas: Schätze der Sammlung Ordrupgaard, Kopenhagen, exh. cat. (Stuttgart: Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, 2003), 80–81, 103n51.

Alan L. Gansberg, Little Caesar: A Biography of Edward G. Robinson (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2004), 357.

Eva-Maria Preiswerk-Lösel, ed., A House for the Impressionists: The Langmatt Museum (Ostfildern-Ruit: Hatje Cantz, 2005), 144.

Joachim Pissarro and Claire Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Catalogue critique des peintures; Critical Catalogue of Paintings (New York: Wildenstein Institute Publications, 2005), no. 1199, pp. 1:364, 366–67, 370–71, 379, 391, 401–02, 409, 3:749, 751, (repro.), as La Rue Saint-Honoré, après-midi, effet de soleil.

Rebecca Dimling Cochran and Bobbie Leigh, “100 Top Collectors who have made a difference,” Art and Antiques (March 2006): 90.

Bobbie Leigh, “Magnificent Obsession,” Art and Antiques 29, no. 6 (June 2006): 61, (repro.), as Rue Saint-Honoré: Sun Effect, Afternoon.

Alice Thorson, “A final countdown—A rare showing of Impressionist paintings from the private collection of Henry and Marion Bloch is one of the inaugural exhibitions at the 165,000-square-foot glass-and-steel structure,” Kansas City Star (June 29, 2006): B1.

“Inaugural Exhibitions Celebrate Kansas City,” Member Magazine (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (Fall 2006): 3.

Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 10, 13, 56-59, 156–57, (repro), as Rue Saint-Honoré, Sun Effect, Afternoon (La rue Saint-Honoré, effet de soleil, après-midi).

Alice Thorson, “A Tiny Renoir Began an Impressive Obsession,” Kansas City Star (June 3, 2007): E4, (repro,), as Rue Saint-Honoré, Sun Effect, Afternoon.

“Lasting Impressions: A Tribute to Marion and Henry Bloch,” Member Magazine (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (Fall 2007): 11-12.

Steve Paul, “Pretty Pictures: Marion and Henry Bloch’s Collection of Superb Impressionist Masters,” Panache 4, no. 3 (Fall 2007): 20, as Rue Saint-Honoré.

Alice Thorson, “Museum to Get 29 Impressionist Works from the Bloch Collection,” Kansas City Star (February 5, 2010): A1.

Carol Vogel, “Inside Art: Kansas City Riches,” New York Times 159, no. 54, 942 (February 5, 2010): C26.

Melissa Muller, Lost Lives, Lost Art: Jewish Collectors, Nazi Art Theft, and the Quest for Justice (New York: Vendome Press, 2010), 11.

Thomas M. Bloch, Many Happy Returns: The Story of Henry Bloch, America’s Tax Man (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, 2011), 175.

Markus Müller, Camille Pissarro: Mit den Augen eines Impressionisten (München: Hirmer, 2013), 47.

Diane Stafford, “Bloch Gift to Go for Nelson Upgrade,” Kansas City Star 135, no. 203 (April 8, 2015): A8.

“Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Officially Accessions Bloch Impressionist Masterpieces,” Artdaily.org (July 25, 2015): http://artdaily.com/news/80246/Nelson-Atkins-Museum-of-Art-officially-accessions-Bloch-Impressionist-masterpieces#.V6oGwlKFO9I.

Julie Paulais, “Le Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art reçoit des tableaux impressionnistes en échange de leurs répliques,” Le Journal des arts (July 30, 2015): http://www.lejournaldesarts.fr/site/archives/ docs_article/129801/le-nelson-atkins-museum-of-art-recoit-des-tableaux-impressionnistes-en-echange-de-leurs-repliques.php.

Josh Niland, “The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Acquires a Renowned Collection of Impressionist and Postimpressionist Art,” architecturaldigest.com (August 6, 2015): https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/nelson-atkins-museum-accessions-bloch-art-collection.

Nina Siegal, “Upon Closer Review, Credit Goes to Bosch,” New York Times 165, no. 57130 (February 2, 2016): C5.

“Nelson-Atkins to unveil renovated Bloch Galleries of European Art in winter 2017,” Artdaily.org (July 20, 2016): http://artdaily.com/news/88852/Nelson-Atkins-to-unveil-renovated-Bloch-Galleries-of-European-Art-in-winter-2017-#.W-NDepNKhaQ.

“Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art celebrates generosity of Henry Bloch with new acquisition,” Artdaily.org (October 18, 2016): http://artdaily.com/news/90923/Nelson-Atkins-Museum-of-Art-celebrates-generosity-of-Henry-Bloch-with-new-acquisition#.W-NDv5NKhaQ.

Catherine Futter et al., Bloch Galleries: Highlights from the Collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2016), 74-75, (repro.), as Rue Saint-Honoré, Sun Effect, Afternoon.

Kelly Crow, “Museum Rewards Donor with Fake Art to Hang at Home,” Wall Street Journal (January 25, 2017): https://www.wsj.com/articles/museum-rewards-donor-with-fake-art-to-hang-at-home-1485370768.

David Frese, “Bloch savors paintings in redone galleries,” Kansas City Star (February 25, 2017): 1A.

Albert Hect, “Henry Bloch’s Masterpieces Collection to Go on Display at Nelson-Atkins Museum,” Jewish Business News (February 26, 2017): http://jewishbusinessnews.com/2017/02/26/henry-bloch-masterpieces-collection/.

David Frese, “Inside the Bloch Galleries: An interactive experience,” Kansas City Star 137, no. 169 (March 5, 2017): 1D, 4D.

“Editorial: Thank you, Henry and Marion Bloch,” Kansas City Star (March 7, 2017): http://www.kansascity.com/opinion/editorials/ article137040948.html. [repr., “Thank you, Henry and Marion Bloch,” Kansas City Star 137, no. 172 (March 8, 2017): 16A].

Hampton Stevens, “(Not Actually) 12 Things To Do During The Big 12 Tournament,” Flatland: KCPT’s Digital Magazine (March 9, 2017): http://www.flatlandkc.org/arts-culture/sports/not-actually-12-big-12-tournament/.

Laura Spencer, “The Nelson-Atkins’ Bloch Galleries feature Old Masterworks and New Technology,” KCUR (March 10, 2017): http://kcur.org/post/nelson-atkins-bloch-galleries-feature-old-masterworks-and-new-technology#stream/0.

Victoria Stapley-Brown, “Nelson-Atkins Museum’s new European art galleries come with a ‘love story,’” Art Newspaper (March 10, 2017): http://theartnewspaper.com/news/museums/nelson-atkins-museum-s-new-european-art-galleries-come-with-a-love-story/.

Harry Bellet, “Don du ciel pour le Musée Nelson-Atkins,” Le Monde (March 13, 2017): http://www.lemonde.fr/arts/article/2017/03/13/don-du-ciel-pour-le-musee-nelson-atkins_5093543_1655012.html.

Menachem Wecker, “Jewish Philanthropist Establishes Kansas City as Cultural Mecca,” Forward (March 14, 2017): http://forward.com/culture/365264/jewish-philanthropist-establishes-kansas-city-as-cultural-mecca/ repr., in Menachem Wecker, “Kansas City Collection Is A Chip Off the Old Bloch,” Forward (March 17, 2017): 20-22], as Rue Saint-Honoré, Sun Effect, Afternoon.

Juliet Helmke, “The Bloch Collection Takes up Residence in Kansas City’s Nelson Atkins Museum,” BoulinArtInfo International (March 15, 2017): http://www.blouinartinfo.com/news/story/ 2005267/the-bloch-collection-takes-up-residence-in-kansas-citys.

Erich Hatala Matthes, “Digital replicas are not soulless—they help us engage with art,” Apollo (March 23, 2017): https://www.apollo-magazine.com/digital-replicas-3d-printing-original-artworks/.

Louise Nicholson, “How Kansas City got its magnificent museum,” Apollo (April 7, 2017): https://www.apollo-magazine.com/how-kansas-city-got-its-magnificent-museum/.

Lilly Wei, “Julián Zugazagoitia: ‘Museums should generate interest and open a door that leads to further learning,’” Studio International (August 21, 2017): http://studiointernational.com/index.php/julian-zugazagoitia-director-nelson-atkins-museum-of-art-kansas-city-interview.

Anne-Birgitte Fonsmark and et al., Gauguin e gli impressionisti: capolavori dalla Collezione Ordrupgaard (Venezia: Marsilio, 2018), 148n4, as La Rue Saint-Honoré, Effet de Soleil, Après-Midi.

Robert D. Hershey Jr., “Henry Bloch, H&R Block’s cofounder, dies at 96,” Boston Globe (April 23, 2019): https://www3.bostonglobe.com/metro/ obituaries/2019/04/23/henry-bloch-block-cofounder/?arc404=true.

Robert D. Hershey, Jr., “Henry W. Bloch, Tax-Preparation Pioneer (and Pitchman), Is Dead at 96,” New York Times (April 23, 2019): https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/23/ obituaries/henry-w-bloch-dead.html.

Claire Selvin, “Henry Wollman Bloch, Collector and Prominent Benefactor of Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Is Dead at 96,” ArtNews (April 23, 2019): http://www.artnews.com/2019/04/23/henry-bloch-dead-96/.

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “Henry Bloch, co-founder of H&R Block, dies at 96,” Kansas City Star 139, no. 219 (April 24, 2019): 1A.

“Henry Wollman Bloch (1922-2019),” Art Forum (April 24, 2019): https://www.artforum.com/news/henry-wollman-bloch-1922-2019-79547.

Frank Morris, “Henry Bloch, Co-Founder Of H&R Block, Dies At 96,” npr.org (April 24, 2019): https://www.npr.org/2019/04/24/716641448/henry-bloch-co-founder-of-h-r-block-dies-at-96.

Ignacio Villarreal, “Nelson-Atkins mourns loss of Henry Bloch,” ArtDaily.org (April 24, 2019): http://artdaily.com/news/113035/Nelson-Atkins-mourns-loss-of-Henry-Bloch#.XMB76qR7laQ.

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “H&R Bloch co-founder, philanthropist Bloch dies,” Cass County Democrat Missourian 140, no. 29 (April 26, 2019): 1A.

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “KC businessman and philanthropist Henry Bloch dies,” Lee’s Summit Journal 132, no. 79 (April 26, 2019): 3A, (repro.).

Luke Nozicka, “Family and friends remember Henry Bloch of H&R Block,” Kansas City Star 139, no. 225 (April 30, 2019): 4A [repr., Luke Nozicka, “Family and friends remember Henry Bloch of H&R Block,” Kansas City Star 139, no. 228 (May 3, 2019): 3A].

Eric Adler, “Sold for $3.25 million, Bloch’s home in Mission Hills may be torn down,” Kansas City Star 141, no. 90 ( December 16, 2020): 2A.