![]()

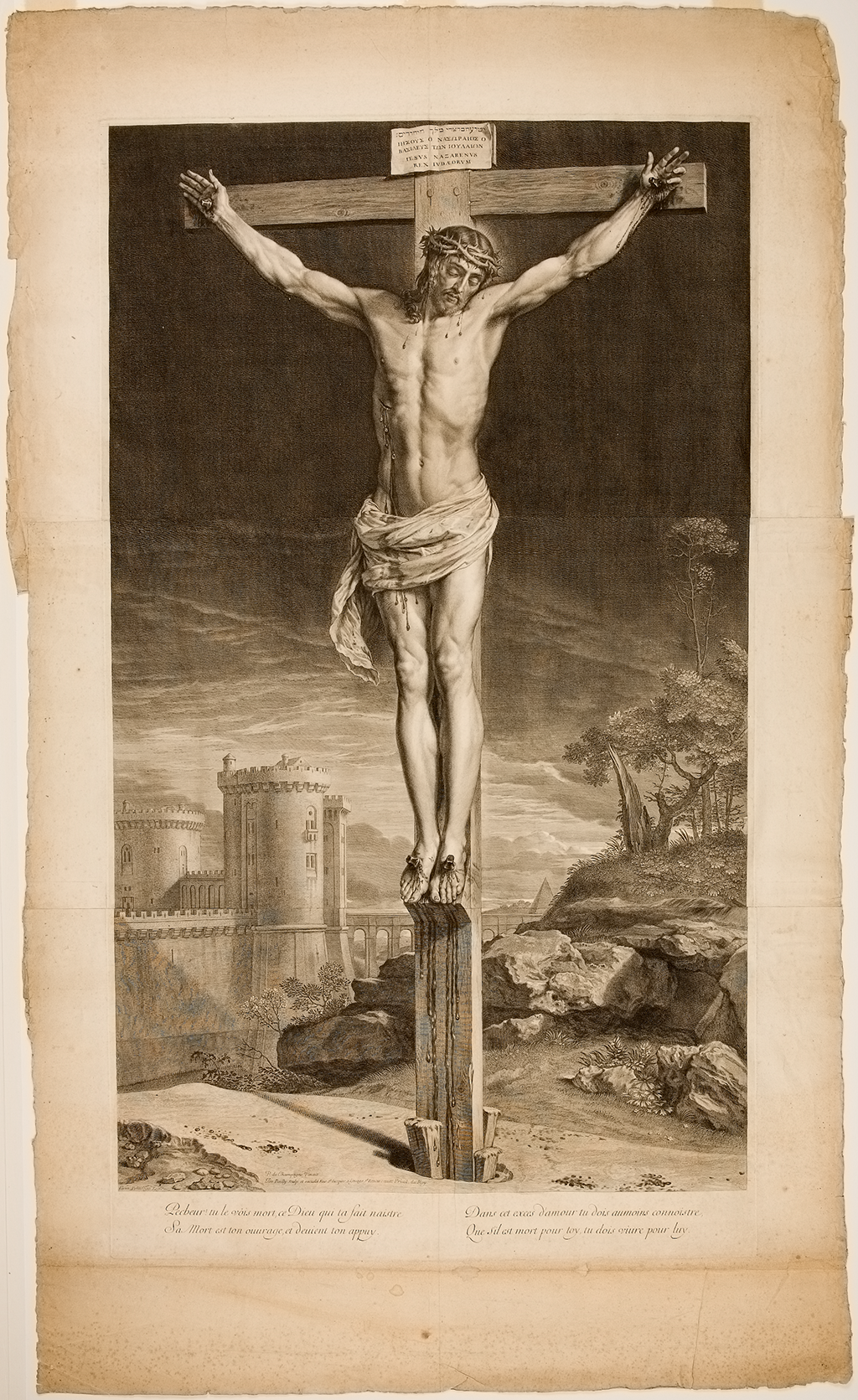

Philippe de Champaigne, Christ on the Cross, ca. 1655

| Artist | Philippe de Champaigne, French, 1602–1674 |

| Title | Christ on the Cross |

| Object Date | ca. 1655 |

| Alternate and Variant Titles | Le Christ sur la croix; Crucifixion; Le Christ mort en croix |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (Unframed) | 35 5/8 × 22 1/16 in. (90.5 × 56 cm) |

| Inscription | Inscribed verso (no longer visible due to relining): Voor myne beminde suster / Marie de Champaigne-Religieuse / Brussel[s?] |

| Credit Line | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 70-1 |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Rima M. Girnius, “Philippe de Champaigne, Christ on the Cross, ca. 1655,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.204.5407.

MLA:

Girnius, Rima M. “Philippe de Champaigne, Christ on the Cross, ca. 1655,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.204.5407.

In this deeply poignant painting, Philippe de Champaigne gives visual and persuasive form to one of the central mysteries of the Christian faith: the willingness of Jesus Christ, the Son of God, to suffer death for the sins of humanity. Champaigne depicts the crucified Christ alone on a rocky outcropping lined with dense vegetation, overlooking a panoramic view of the ancient city of Jerusalem. Dark, foreboding clouds crown the landscape, forming an almost impenetrable background that throws Christ’s torso into strong relief. Shown moments after his death, Christ’s figure appears upright, his bruised body presented for contemplation. Blood streams from the wounds on his side, hands, and feet, cascading down the crisp folds of his loincloth and the base of the cross to soak the ground beneath him. A network of fine lines on his chest—marks of the brutal flogging he received before his crucifixion—draw further attention to the physical torment he endured on behalf of humankind. Notwithstanding these visible signs of his agony, Christ remains an idealized figure. A beam of light bathes his body in a silvery radiance, illuminating not only his injuries but also the elegant proportions and musculature of his meticulously modeled body. His calm facial expression—head cast down, eyes closed—imparts a sense of dignity to the scene and, along with the faintly glowing halo, reveals his divine status as the Son of God.

Sober in its treatment yet deeply emotional in its impact, the painting exhibits a narrative clarity and pictorial restraint that has often been attributed to Champaigne’s close relationship with Jansenism. A controversial reform movement within the Catholic Church, Jansenism emphasized humankind’s inability to attain salvation without divine aid and insisted on pursuing a life devoid of worldly distractions.1For an overview on Jansenism and its role in seventeenth-century French cultural and political life, see Henry Phillips, Church and Culture in Seventeenth-Century France (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 16; and F. Ellen Weaver-Laporte, “Jansenism,” in Grove Art Online, 2003, accessed August 6, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T043395. Much has been written about the artist’s connections with this movement and whether his work reveals a specific “Jansenist” aesthetic. As early as 1837, literary critic Charles Augustin Saint-Beuve linked Champaigne’s “calm, sober, dense, and serious” paintings with Jansenist spirituality and piety.2“Sa peinture calme, sobre, serrée, sérieuse.” Charles-Augustin Sainte-Beuve, Port Royal, 4th ed. (Paris: Librairie Hachette, 1876), 1:26; quoted in Anne Bertrand, Art and Politics in Counter-Reformation Paris: The Case of Philippe de Champaigne and his Patrons (1621–1674) (PhD diss., University of Pittsburgh, 2001), 79. The artist had close ties with the most important Jansenist center in France, the Cistercian abbey of Port-Royal-des-Champs. His two daughters entered the abbey’s school in 1648, and he earned numerous commissions to paint works for the Port Royal community.3Bernard Dorival, Philippe de Champaigne, 1602–1676: La vie, l’œuvre, et le catalogue raisonné de l’œuvre (Paris: Léonce Laget Libraire, 1976), 1:160. Indeed, one of the most well-known stories about Champaigne is that his daughter Catherine de Sainte Suzanne was miraculously healed from a paralysis that had lasted for two years when, in 1662, the Abbess at Port-Royal prayed for Catherine’s healing. Champaigne was inspired to commemorate this event by painting Mère Catherine Agnes Arnauld and Soeur Catherine de Sainte Suzanne (1662; Musée du Louvre, Paris). Leading scholars caution against interpreting Champaigne solely through the lens of his Jansenist affiliation, but they acknowledge that his work can be understood within the larger context of Catholic beliefs and practices as defined by the Council of TrentCouncil of Trent: A council of the Roman Catholic Church, held in in the city of Trent, Italy, in three parts from 1545 to 1563, that responded to the doctrinal challenges of the Protestants. It played a key part in the Counter-Reformation and played a vital role in revitalizing the Roman Catholic Church in many parts of Europe. See also Counter-Reformation..4Dorival, Philippe de Champaigne, 1:161; Lorenzo Pericolo, Philippe de Champaigne: “Philippe, homme sage et vertueux”: Essai sur l’art et l’œuvre de Philippe de Champaigne (1602–1674) (Tournai: La Renaissance du Livre, 2002), 228; Alain Tapié, “L’art de l’âme,” in Alain Tapié and Pierre-Nicolas Sainte-Fare-Garnot, eds., Philippe de Champaigne (1602–1674): Entre politique et dévotion, exh. cat. (Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 2007), 37–47. As Marianne Cojannot-Le Blanc observes, Champaigne cannot be regarded simply as a Jansenist painter, since Jansenism did not exist as a homogenous movement, nor did it break away from Catholicism.5Marianne Cojannot-Le Blanc, “Le jansénisme et les arts” in Cojannot-Le Blanc, ed., Philippe de Champaigne ou la figure du peintre janséniste: Lecture critique des rapports entre Port-Royal et les arts (Paris: Nolin, 2011), 9.

Such an approach is appropriate for Champaigne’s depiction of the crucified Christ in the collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. The unflinching focus on the figure of Christ and his physical suffering was in line with traditional Catholic ideas, affected by the Reformation and the Council of Trent, regarding the use of images as aids to religious instruction and devotion. Spiritual manuals by mystics such as François de Sales espoused a method of prayer that encouraged imaginative participation in the events of Christ’s life, meant to lead to a deeper understanding of the self and of the divine.6Richard Viladesau, The Pathos of the Cross: The Passion of Christ in Theology and the Arts—The Baroque Era (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 20, 24–25, 36–39. External images played a significant role within these meditative practices by activating the senses and stirring the hearts and minds of the faithful.7Wietse de Boer and Christine Göttler, “Introduction: The Sacred and the Senses in an Age of Reform,” in Boer and Göttler, eds., Religion and the Senses in Early Modern Europe (Leiden: Brill,2015), 1–13; Jeffrey Chipps Smith, Sensuous Worship: Jesuits and the Art of the Early Catholic Reformation in Germany (Princeton,NJ: Princeton University Press, 2002). Key figures of the Counter-ReformationCounter-Reformation: A period lasting about one hundred years from about 1545 (the opening of the Council of Trent) to 1648 (the end of the Thirty Years’ War), when the Roman Catholic church responded to doctrinal challenges from the Protestant Reformation and revitalized its own spirituality and morality. See also Council of Trent., most notably Johannes Molanus and Gabriele Paleotti, published treatises that provided specific direction on how sacred images could fulfill this important function. They insisted that, for the benefit of the faithful, religious works of art should be simple, readily intelligible, and easy to grasp, with no superfluous details. To that end, they privileged scriptural accuracy and promoted naturalism as a means of opening a pathway toward spiritual contemplation.8The body of research on the Council of Trent’s decrees on art and their interpretation by Paleotti and Molanus is vast. Christian Hecht provides a good overview in Katholische Bildertheologie im Zeitalter von Gegenreformation und Barock: Studien zu Traktaten von Johannes Molanus, Gabriele Paleotti und Anderen Autoren (Berlin: Mann, 1997). See also the English edition of Gabrielle Paleotti’s text, which features an introduction by Paoli Prodi: Gabrielle Paleotti, Discourse on Sacred and Profane Images, trans. William McCuaig (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2012). On Molanus, see David Freedberg, “Johannes Molanus on Provocative Paintings,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 34 (1971): 115–50.

Without sufficient documentary evidence, attempts to clarify the nature of Marie de Champaigne’s religious devotions are speculative at best. Recent studies of beguinages in the Low Countries, however, reveal general trends in their use of religious imagery that might provide some insight. Beguinages were semi-monastic communities where women took temporary vows of chastity and obedience but maintained financial independence and were able to retain property. A study of the art that adorned the homes of Beguines in Antwerp’s Beguinage of St. Catherine discloses a substantial number of scenes from Christ’s PassionPassion of Christ: The sequence of events encompassing Jesus Christ’s triumphal entry into Jerusalem, his suffering, death, and ultimately his resurrection., including several Crucifixions.24Sarah Moran, “Bringing the Counter-Reformation Home: The Domestic Use of Artworks at the Antwerp Beguinage in the Seventeenth Century,” Simiolus 38, no. 3 (2015–2016): 148–51. These range in material from two-dimensional crucifixes to works on paper and a painting by Flemish artist Jan Boeckhorst (ca. 1604–1668). As Sarah Moran points out, the abundance of Passion imagery was not unusual and was wholly in keeping with the beliefs and devotional practices promoted by the Counter-Reformation.25Moran, “Bringing the Counter-Reformation Home,” 151–52. Moran is questioning the argument made by other scholars that Beguines showed a marked preference for works of art and devotional texts that linger on the physical details of Christ’s suffering as a human being. See Xander van Eck, “Between Restraint and Excess: The Decoration of the Church of the Great Beguinage at Mechelen in the Seventeenth Century,” Simiolus 28 (2000–2001): 129–62; Hans Geybels, Vulgaritiner Beghinae: Eight Centuries of Beguine History in the Low Countries (Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 2004), 82–85, 125–27.

Notes

-

For an overview on Jansenism and its role in seventeenth-century French cultural and political life, see Henry Phillips, Church and Culture in Seventeenth-Century France (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 16; and F. Ellen Weaver-Laporte, “Jansenism,” in Grove Art Online, 2003, accessed August 6, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article. T043395.

-

“Sa peinture calme, sobre, serrée, sérieuse.” Charles-Augustin Sainte-Beuve, Port Royal, 4th ed. (Paris: Librairie Hachette, 1876), 1:26; quoted in Anne Bertrand, Art and Politics in Counter-Reformation Paris: The Case of Philippe de Champaigne and his Patrons (1621–1674) (PhD diss., University of Pittsburgh, 2001), 79.

-

Bernard Dorival, Philippe de Champaigne, 1602–1676: La vie, l’œuvre, et le catalogue raisonné de l’œuvre (Paris: Léonce Laget Libraire, 1976), 1:160. Indeed, one of the most well-known stories about Champaigne is that his daughter Catherine de Sainte Suzanne was miraculously healed from a paralysis that had lasted for two years when, in 1662, the Abbess at Port-Royal prayed for Catherine’s healing. Champaigne was inspired to commemorate this event by painting Mère Catherine Agnes Arnauld and Soeur Catherine de Sainte Suzanne (1662; Musée du Louvre, Paris).

-

Dorival, Philippe de Champaigne, 1:161; Lorenzo Pericolo, Philippe de Champaigne: “Philippe, homme sage et vertueux”: Essai sur l’art et l’œuvre de Philippe de Champaigne (1602–1674) (Tournai: La Renaissance du Livre, 2002), 228; Alain Tapié, “L’art de l’âme,” in Alain Tapié and Pierre-Nicolas Sainte-Fare-Garnot, eds., Philippe de Champaigne (1602–1674): Entre politique et dévotion, exh. cat. (Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 2007), 37–47.

-

Marianne Cojannot-Le Blanc, “Le jansénisme et les arts” in Cojannot-Le Blanc, ed., Philippe de Champaigne ou la figure du peintre janséniste: Lecture critique des rapports entre Port-Royal et les arts (Paris: Nolin, 2011), 9.

-

Richard Viladesau, The Pathos of the Cross: The Passion of Christ in Theology and the Arts—The Baroque Era (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 20, 24–25, 36–39.

-

Wietse de Boer and Christine Göttler, “Introduction: The Sacred and the Senses in an Age of Reform,” in Boer and Göttler, eds., Religion and the Senses in Early Modern Europe (Leiden: Brill, 2015), 1–13; Jeffrey Chipps Smith, Sensuous Worship: Jesuits and the Art of the Early Catholic Reformation in Germany (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2002).

-

The body of research on the Council of Trent’s decrees on art and their interpretation by Paleotti and Molanus is vast. Christian Hecht provides a good overview in Katholische Bildertheologie im Zeitalter von Gegenreformation und Barock: Studien zu Traktaten von Johannes Molanus, Gabriele Paleotti und Anderen Autoren (Berlin: Mann, 1997). See also the English edition of Gabrielle Paleotti’s text, which features an introduction by Paoli Prodi: Gabrielle Paleotti, Discourse on Sacred and Profane Images, trans. William McCuaig (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2012). On Molanus, see David Freedberg, “Johannes Molanus on Provocative Paintings,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 34 (1971): 115–50.

-

Dorival, Philippe de Champaigne, 1:80–81. For a more extended analysis, see Bernard Dorival, “La bibliothèque de Philippe et de Jean-Baptiste de Champaigne,” Chroniques de Port-Royal 19 (1971): 26, 34. In their reviews of Dorival’s 1976 catalogue raisonné, Ann Sutherland Harris and Anthony Blunt question the plausibility of some of Dorival’s arguments regarding Champaigne’s use of literary sources. Ann Sutherland Harris, review of Philippe de Champaigne, 1602–1676: La vie, l’œuvre, et le catalogue raisonné de l’œuvre, by Bernard Dorival, Art Bulletin 61, no. 2 (June 1979): 320; Anthony Blunt, “A New Book on Philippe de Champaigne,” review of Philippe de Champaigne, 1602–1676: La vie, l’œuvre, et le catalogue raisonné de l’œuvre, by Bernard Dorival,” Burlington Magazine 119, no. 893 (August 1977): 575.

-

Olan A. Rand, “Philippe de Champaigne and the Concept of Archeological Accuracy in Painting,” in Actas del XXIII Congreso Internacional de Historia del Arte (Granada: University of Granada, 1978), 3:213–21.

-

Dorival, Philippe de Champaigne, 1:76–78

-

Dorival, Philippe de Champaigne, 1:74.

-

Pericolo, Philippe de Champaigne, 265–66.

-

Pierre Rosenberg, France in the Golden Age: Seventeenth-Century French Paintings in American Collections, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1982), 236.

-

Dorival, Philippe de Champaigne, 2:385–86; Alain Tapié and Nicolas Sainte Fare Garno, Entre politique et dévotion, 244–45.

-

Pericolo, Philippe de Champaigne, 311n20; Gilles Chomer, Peintures françaises avant 1815: La collection du Musée de Grenoble (Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 2000), 64.

-

According to Émile Mâle, it was common to see three and four nails in Crucifixion scenes. Émile Mâle, L’Art religieux après le Concile de Trente: étude iconographique de la fin du XVIe siècle, du XVIIe, du XVIIIe; Italie, France, Espagne, Flandres (Paris: A. Colin, 1932), 270–71.

-

Alfred Cohen and Ronald Cohen, Trafalgar Galleries XII (London: Trafalgar Fine Art Publications, 1993), 34.

-

The inscription was discovered on June 5, 1969, when the original canvas was relined by Francis Moro, a painting restorer employed by the dealer Frederick Mont, who at the time was in possession of the painting. Although no photograph of the original inscription was found, the conservator transcribed the dedication, which is in both Flemish and French and reads: “Voor myne beminde suster / Marie de Champaigne–Religieuse / Brussel[s?]” (For my beloved sister / Marie de Champaigne–Nun / Brussels).

-

The date of Philippe de Champaigne’s visit is contested. According to his contemporary André Félibien, the Brussels visit took place in 1654. See André Félibien, Entretiens sur les vies et sur les ouvrages des plus excellents peintres anciens et modernes (Paris, 1685), 5:175–76. Pericolo, however, argues that Félibien may have mistaken the date and it should be 1655; see Pericolo, Philippe de Champaigne, 273.

-

“Marie/a Jampaine.” List of Beguines, 1628–1798, no. 21806, church archives of Brabant, Royal Archives, Brussels.

-

The birth and death dates are provided by Anne-Marie Bonenfant-Feytmans, “Un tableau inconnu de Philippe de Champaigne: Proposition d’identification,” Bulletin (Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts, Brussels) 34–37, nos. 1–3 (1985–1988): 147.

-

Aquarelles et Tableaux Modernes; Dessins et Tableaux Anciens; Objets d’Art et d’Ameublement Principalement du XVIIIe Siècle; Sièges et Meubles des époques Régence—Louis XV–Louis XVI; Tapisseries Anciennes (Paris: Palais Galliera, 1968), unpaginated, as attributed to Philippe de Champaigne, Le Christ sur la croix.

-

Sarah Moran, “Bringing the Counter-Reformation Home: The Domestic Use of Artworks at the Antwerp Beguinage in the Seventeenth Century,” Simiolus 38, no. 3 (2015–2016): 148–51. These range in material from two-dimensional crucifixes to works on paper and a painting by Flemish artist Jan Boeckhorst (ca. 1604–1668).

-

Moran, “Bringing the Counter-Reformation Home,” 151–52. Moran is questioning the argument made by other scholars that Beguines showed a marked preference for works of art and devotional texts that linger on the physical details of Christ’s suffering as a human being. See Xander van Eck, “Between Restraint and Excess: The Decoration of the Church of the Great Beguinage at Mechelen in the Seventeenth Century,” Simiolus 28 (2000–2001): 129–62; Hans Geybels, Vulgaritiner Beghinae: Eight Centuries of Beguine History in the Low Countries (Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 2004), 82–85, 125–27.

-

See treatment report by Mary Schafer, Nelson-Atkins paintings conservator, November 12, 2012, Nelson-Atkins conservation files. Schafer removed the modern fingerprints from the varnish layer of the composition.

Technical Entry

Technical entry forthcoming.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Meghan L. Gray, “Philippe de Champaigne, Christ on the Cross, ca. 1655,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.204.4033.

MLA:

Gray, Meghan L. “Philippe de Champaigne, Christ on the Cross, ca. 1655,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.204.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Meghan L. Gray, “Philippe de Champaigne, Christ on the Cross, ca. 1655,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.204.4033.

MLA:

Gray, Meghan L. “Philippe de Champaigne, Christ on the Cross, ca. 1655,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.204.4033.

Given by the artist to his sister, Marie de Champaigne (1606–1665), Brussels, by December 11, 1665 [1];

Sale, Aquarelles et Tableaux Modernes, Dessins et Tableaux Anciens, Objets d’Art et d’Ameublement Principalement du XVIIIe Siècle, Sièges et Meubles des époques Régence—Louis XV—Louis XVI, Tapisseries Anciennes, Palais Galliera, Paris, October 22, 1968, lot 42, as attributed to Philippe de Champaigne, Le Christ sur la croix;

With Frederick Mont, Inc., New York, by May 15, 1969–1970 [2];

Purchased from Mont by The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1970.

Notes

[1] According to an inscription on the verso of the original canvas, which was subsequently covered by relining, the artist gave the painting to his sister, Marie de Champaigne, a Beguine nun in Brussels. The inscription, which reads, “Voor myne beminde suster / Marie de Champaigne–Religieuse / Brussels,” was transcribed by Francis Moro, a painting restorer employed by Frederick Mont, Inc., at the time he lined the painting on June 5, 1969. See Nelson-Atkins curatorial files.

[2] Letter from Frederick Mont, Inc., to the Nelson-Atkins on December 11, 1969, states the painting was purchased in Paris by “Fritz” (per Nancy Yeide, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., this was probably Frederick Mont, né Adolf Fritz Mondschein, Vienna, 1894–1994; letter to Meghan Gray, The Nelson-Atkins, December 3, 2012). A restoration record from Paul Moro, Inc., New York, indicates that the painting was owned by Mont when the painting was brought to Moro for restoration on May 15, 1969. See Nelson-Atkins curatorial files.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Meghan L. Gray, “Philippe de Champaigne, Christ on the Cross, ca. 1655,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.204.4033.

MLA:

Gray, Meghan L. “Philippe de Champaigne, Christ on the Cross, ca. 1655,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.204.4033.

Variants with Christ looking down or dead

Philippe de Champaigne, Le Christ mort sur la croix (Christ Dead on the Cross), 17th century, oil on panel, 66 15/16 x 36 5/8 in. (170 x 93 cm), private collection, Toulouse.

Philippe de Champaigne, Christ en croix (Christ on the Cross), 1635–1638, oil on canvas, 32 x 22 1/4 in. (81.3 x 56.5 cm), private collection, São Paulo, Brazil.

Philippe de Champaigne, Le Christ mort sur la Croix (Christ Dead on the Cross), ca. 1654, oil on canvas, 37 x 27 1/2 in. (94 x 70 cm), Trafalgar Galleries, London.

Philippe de Champaigne, Le Christ mort sur la croix (Christ Dead on the Cross), 1655, oil on canvas, 89 3/8 x 79 1/2 in. (227 x 202 cm), Musée de Grenoble.

Philippe de Champaigne, Christ on the Cross, ca. 1655–1660, oil on canvas, 33 3/16 x 24 15/16 in. (84.3 x 63.3 cm), National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa.

Variants with Christ looking up

Philippe de Champaigne, Le Christ en croix implorant Le Père (Christ on the Cross Imploring the Father), ca. 1674, oil on canvas, 196 7/8 x 118 1/8 in. (500 x 300 cm), Eglise Saint Pierre, Chaumes-en-Brie (Seine-et-Marne), France.

Philippe de Champaigne, Le Christ en Croix (Christ on the Cross), 1674, oil on canvas, 89 3/4 x 60 1/4 in. (228 x 153 cm), Musée du Louvre, Paris.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Meghan L. Gray, “Philippe de Champaigne, Christ on the Cross, ca. 1655,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.204.4033.

MLA:

Gray, Meghan L. “Philippe de Champaigne, Christ on the Cross, ca. 1655,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.204.4033.

France in the Golden Age: Seventeenth-Century French Paintings in American Collections, Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais, Paris, January 29–April 26, 1982; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, May 26-August 22, 1982; The Art Institute of Chicago, September 18–November 28, 1982, no. 17, as Christ on the Cross.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Meghan L. Gray, “Philippe de Champaigne, Christ on the Cross, ca. 1655,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.204.4033.

MLA:

Gray, Meghan L. “Philippe de Champaigne, Christ on the Cross, ca. 1655,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.204.4033.

Aquarelles et Tableaux Modernes; Dessins et Tableaux Anciens; Objets d’Art et d’Ameublement Principalement du XVIIIe Siècle; Sièges et Meubles des époques Régence—Louis XV—Louis XVI; Tapisseries Anciennes (Paris: Palais Galliera, 1968), unpaginated, (repro.), as attributed to Philippe de Champaigne, Le Christ sur la croix.

“La Chronique des Arts (Supplément à la “Gazette des Beaux-Arts”),” Gazette des Beaux-Arts, 77, no. 1225 (February 1971): 73, (repro.), as Crucifixion.

“Recent Accessions of American and Canadian Museums: July–September 1970,” Art Quarterly 34, no. 1 (Spring 1971): 126, 131, (repro.), as Crucifixion.

Bernard Dorival, “Recherches sur les sujets sacrés et allégoriques gravés au XVIIe et au XVIIIe siècle d’après Philippe de Champaigne,” Gazette des Beaux-Arts 80, nos. 1242–43 (July–August 1972): 33.

Ralph T. Coe, “The Baroque and Rococo in France and Italy,” Apollo, 96, no. 130 (December 1972): 530–531, 533–534, (repro.) [repr., in Denys Sutton, ed., William Rockhill Nelson Gallery, Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Kansas City (London: Apollo Magazine, 1972), 62–63, 65–66, (repro.)], as Crucifixion.

Ross E. Taggart and George L. McKenna, eds., Handbook of the Collections in The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Kansas City, Missouri, vol. 1, Art of the Occident, 5th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1973), 108, 128, (repro.), as Crucifixion.

Bernard Dorival, Philippe de Champaigne, 1602–1676: La vie, l’œuvre, et le catalogue raisonné de l’œuvre (Paris: Léonce Laget Libraire, 1976), no. 2044, pp. 1:25n15 (erroneously as no. 2043), 74, 77, 79, 81, 117, 137 (erroneously as no. 90), 138, 141–42, 150 (erroneously as no. 2043), 159 (erroneously as no. 2043), 171; 2:46 (erroneously as no. 2043), 385–86, 516, (repro.), as Le Christ Mort en Croix.

Pierre Rosenberg, France in the Golden Age: Seventeenth-Century French Paintings in American Collections, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1982), 159, 235–36, 349, 378, (repro.), as Christ on the Cross.

Claudette Hould, “Lettre de Paris: La peinture française du 17e siècle dans les collections américaines,” Vie des Arts 27, no. 107 (Summer 1982): 15, (repro.), as Le Christ en croix.

Tom L. Freudenheim, ed., American Museum Guides: Fine Arts; A Critical Handbook to the Finest Collections in the United States (New York: Collier, 1983), 112, as Crucifixion.

Anne-Marie Bonenfant-Feytmans, “Un tableau inconnu de Philippe de Champaigne. Proposition d’identification,” Bulletin (Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, Brussels) 34–37, no. 1–3 (1985–1988): 147, as Christ en croix.

Christopher Wright, The French Painters of the Seventeenth Century (Boston: Little, Brown, 1985), 154, as Christ on the Cross.

Myron Laskin, Jr. and Michael Pantazzi, eds., European and American Painting, Sculpture, and Decorative Arts, vol. 1, 1300–1800/Text (Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada, 1987), 69–70, 355.

Bernard Dorival, Jean-Baptiste de Champaigne (1631–1681): La vie, l’homme et l’art (Paris: Bernard Dorival, 1992), 9, as Christ en croix.

Christopher Wright, The World’s Master Paintings: From the Early Renaissance to the Present Day (London: Routledge, 1992), 1:233, as Crucifixion, and 2:122.

Alfred Cohen, Ronald Cohen, and W. J. Van der Watering, Trafalgar Galleries XII (London: Trafalgar Fine Art Publications, [1993]), 34, 35n1, (repro.).

Roger Ward and Patricia J. Fidler, eds., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collection (New York: Hudson Hills Press, in association with Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1993), 170, (repro.), as Christ on the Cross.

Ronald Cohen and Alfred Cohen, Trafalgar Galleries at Maastricht, exh. cat. (London: Trafalgar Fine Art Publications, 1999), 22–23, (repro.).

J. Bradley Chance and Milton P. Horne, Rereading the Bible: An Introduction to the Biblical Story (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2000), 323, (repro.), as Christ on the Cross.

Gilles Chomer, Peintures françaises avant 1815: La collection du Musée de Grenoble (Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 2000), 64, as Christ mort sur la croix.

Emmanuel Coquery and Anne Piéjus, eds., Figures de la Passion, exh. cat. (Paris: musée de la musique, 2001), 131n6.

Lorenzo Pericolo, Philippe de Champaigne: “Philippe, homme sage et vertueux:” Essai sur l’art et l’œuvre de Philippe de Champaigne (1602–1674) (Tournai, Belgium: La Renaissance du Livre, 2002), 311n20, as Christ en croix.

Lorenzo Pericolo, “Une ‘Crucifixion’ inédite de Philippe de Champaigne,” Paragone 56, no. 59 (January 2005): 77n4.

Alain Tapié and Nicolas Sainte Fare Garnot, Philippe de Champaigne (1602–1674): Entre politique et dévotion, exh. cat. (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 2007), 244–45, (repro.), as Le Christ mort sur la Croix.

Deborah Emont Scott, ed., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collection, 7th ed. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2008), 78, (repro.), as Christ on the Cross.