![]()

Claude Monet, Boulevard des Capucines, 1873–1874

| Artist | Claude Monet, French, 1840–1926 |

| Title | Boulevard des Capucines |

| Object Date | 1873–1874 |

| Alternate and Variant Titles | Les Grands Boulevards |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (Unframed) | 31 5/8 x 23 3/4 in. (80.3 x 60.3 cm) |

| Signature | Signed lower right: Claude Monet |

| Credit Line | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Purchase: The Kenneth A. and Helen F. Spencer Foundation Acquisition Fund, F72-35 |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “Claude Monet, Boulevard des Capucines, 1873—1874,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.626.5407

MLA:

Marcereau DeGalan, Aimee. “Claude Monet, Boulevard des Capucines, 1873—1874,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.626.5407.

High above his native city of Paris in late 1873/early 1874, Claude Monet perched with his paints, palette, brushes, and canvases on the upper-level balconies of 35 boulevard des Capucines. The building was emblazoned with ten-foot-high red neon letters spelling the nickname of its owner, famed photographer Gaspard-Félix Tournachon (1820–1889), better known as Nadar. Looking northeast, toward the Place de l’Opéra, Monet painted two canvases of nearly identical proportions, but in different formats—a vertical composition, now at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, and a horizontal canvas, now in the Pushkin Museum collection (Fig. 1), the latter of which Monet exhibited in the inaugural Impressionist exhibition in 1874 in Nadar’s former studio.1While many of the contemporary reviews of the 1874 exhibition could conceivably apply to both pictures, hence the long debate over which canvas was exhibited, an English review by Frederick Wedmore noted that “Claude Monet sends the ‘Boulevard des Capucines’ a rough oil sketch some four feet long.” This measurement must refer to a framed dimension and could only relate to the width of the horizontal Pushkin canvas, as the framed height of the Nelson-Atkins Boulevard is 43 3/8 in. See Frederick Wedmore, “Pictures in Paris: The Exhibition of ‘Les Impressionistes’,” The Examiner (June 13, 1874): 633–34, as cited in Ed Lilley, “A Rediscovered English Review of the 1874 Impressionist Exhibition,” Burlington Magazine 154, no. 1317 (2012): 845.

In the Nelson-Atkins composition, Monet captures the hustle-bustle of the boulevard on a cool, wintry day. Some women with parasols stroll, and possibly shop, alongside men in top hats and families with children, including a girl in a pink-and-white dress who ambles away from a balloon vendor holding a bunch of pink balloons. Others may be guests of the Grand Hôtel, seen at the center left amid the mansard-style hip roofs of the stylish new multistory apartment buildings. A single burgundy-and-yellow Morris advertising column stands sentinel near the row of snow-covered hansom cabs that cuts a sharp diagonal into the picture plane. Those with occupants, including an omnibus, whiz down the boulevard in a blur. Appearing at center right, hovering over the street from the balcony next to Nadar’s studio, two onlookers in top hats survey the frenetic activity below. Above them is the Place de l’Opéra, home to architect Charles Garnier’s new opera house. Monet’s figures are loose, mere suggestions, some hastily laid down on the canvas in dry brushy strokes over areas of exposed groundground layer: An opaque preparatory layer applied to the support, either commercially or by the artist, to prevent absorption of the paint into the canvas or panel. See also priming layer.. While he left reservesreserve: An area of the composition left unpainted with the intention of inserting a feature at a later stage in the painting process. for the foreground figures and the tops of the trees, in other areas there is evidence he painted on top of a wet ground, adding and developing as he went in order to realize his vision.3See the accompanying technical essay by Diana M. Jaskierny. This suggests he may have viewed the work as a sketch, an idea supported by an entry in Monet’s account books in the spring of 1875 noting a sale of “3 esquisses” (three sketches) to the painter and photographer Charles Vaillant de Meixmoron de Dombasle (1839–1912) for 300 francs.4As per a notation in the curatorial files, Charles de Meixmoron de Dombasle bought ten works from Monet in 1873. He acquired an additional three sketches in 1875. Although these are not individually enumerated, it is likely that the Nelson-Atkins Boulevard des Capucines was in the 1875 transaction. I am grateful to Simon Kelly, curator of modern and contemporary art, St. Louis Art Museum, for sharing information and his thoughts about the 1875 sale. See Monet’s entry under May 4, 1875, “M. de Dombasle / [illegible] / 3 esquisses 300 [francs]” (Monet’s livre de comptes, ventes janvier–juillet 1875, Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris. A photocopy of this page is in the curatorial object file, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art).

The Pushkin Boulevard presents the same view, but in contrast to the evenly diffuse blue-violet wintry haze in the Nelson-Atkins composition, it is bathed in a golden glow on the left half of the composition, while the right half falls into deep shadow. The two canvases are essentially effetseffets: French for “effects.” An artist’s emphasis on the atmospheric effects of time and weather on the subject matter., painted in different light, probably at different times of day. The horizontal format of the Pushkin picture clips the tops of the buildings along the left edge but allows for a wider expanse of crowd; the figures, although still loosely painted, are rendered with more clarity than those of the Nelson-Atkins composition, in paticular, the two men in top-hats who survey the street below, suggesting the Pushkin picture came second.5In the spring of 1874, following the first Impressionist exhibition, Jean-Baptiste Faure bought four works by Monet for 4,000 francs, including the Pushkin Boulevard des Capucines. The pricing structure of 1,000 francs per picture, suggests Monet considered this a finished work. For the notation of Monet’s account books, see Anne Distel, Impressionism: The First Collectors, trans. Barbara Perround-Benson (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1990), 84. What remains murky, however, are the precise dating of these two canvases and further evidence to support the order of their execution.

Most scholars, including Daniel Wildenstein, accept the 1873 inscription on the Pushkin picture, suggesting Monet painted it in the fall of 1873, and that the Nelson-Atkins canvas followed closely thereafter in the winter of 1873/1874 to account for the snow.6Daniel Wildenstein, Monet: Catalogue Raisonné; Werkverzeichnis, trans. Josephine Bacon (Cologne: Benedikt Taschen Verlag GmbH, 1996), 2:124–25. The acceptance of the 1873 date is predicated not only on the inscription of the Pushkin picture but also early reviews of the Pushkin picture written during Monet’s lifetime by his friend, Gustave Geffroy. See Gustave Geffroy, “Chronique—Claude Monet,” La Justice (March 15, 1883): 2, and Gustave Geffroy, Claude Monet: Sa vie, son œuvre (Paris: G. Crès, 1922), 263. There was no snow in Paris in the fall of 1873, but there were several days of thick hoarfrost and frost, in November and December 1873, which could account for the white covering on the hansom cabs and ground in the Nelson-Atkins picture. It did not snow until February 9, 1874. See the Observatoire de la marine et du bureau des longitudes, Paris et Observatoire de Montsouris, Bulletin mensuel de l’Observatoire Physique Central de Monsouris (Paris: Gauthier-Villars, 1873/1874), https://bibnum.obspm.fr/ark:/11287/2BfGK and https://bibnum.obspm.fr/ark:/11287/VPTcP. However, the execution of the canvases as noted above, in tandem with Monet selling the Nelson-Atkins Boulevard des Capucines to Dombasle as a sketch, suggests a reversal of order. Monet was in Paris often that fall/early winter of 1873/1874 as part of developing conversations around organizing the first Impressionist exhibition. Presumably discussions were underway about using Nadar’s former studio as a venue, so it is likely Monet started both canvases that fall with the idea of presenting one of them from the very room in which he painted it. It was a calculated move. Recently, however, Joel Isaacson challenged the Pushkin date, arguing instead for an early 1874 completion for both the Pushkin and the Nelson-Atkins pictures, a period during which many other scholars believe Monet was in Amsterdam.7See Joel Isaacson, “Monet: Le Boulevard des Capucines en Carnival,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 20, no. 1 (Spring 2021): https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2021.20.1.3. Daniel Wildenstein believes Monet traveled to Amsterdam in the spring of 1874. See Daniel Wildenstein, Monet, or The Triumph of Impressionism (Cologne: Benedikt Taschen Verlag GmbH, 1996), 1:108–09. Isaacson reconnected the paintings to carnival, a month-long celebration that occurs annually between Epiphany (January 6) and Lent. Carnival brought grand processions down the boulevard des Capucines during the last three days of celebration known as the jours de gras, or “fat days,” which in 1874 fell on February 15–17,8Isaacson, “Monet: Le Boulevard des Capucines en Carnival.” Gustave Geffroy first made this connection to carnival in an 1883 review of the Pushkin picture at Durand-Ruel, a position he maintained along with the painting’s 1873 date in his 1922 biography, authored nearly twenty-five years into his friendship with Monet. See Geffroy, “Chronique—Claude Monet,” 2, and Geffroy, Claude Monet, 263, where he titled the Pushkin painting Le Boulevard des Capucines en Carnival. the precise period Isaacson places the Pushkin picture, when crowds and masked processions were at their peak. However, rather than starting the canvases from scratch in mid-February, a mere two months before the exhibition, in a move that feels haphazard rather than contemplated, it makes more sense that Monet at least roughed both canvases out in the late fall, starting first with the Nelson-Atkins picture. Having worked through some of the major compositional issues in the Nelson-Atkins painting, his approach in the Pushkin picture is more resolved. Notwithstanding the rain that fell all three days of the jours de gras in 1874, there is precedent for Monet choosing a moment to capitalize on the crowds as part of a marketing strategy for his pictures.9For the weather in February 1873, see the Observatoire de la marine et du bureau des longitudes, Paris et Observatoire de Montsouris, (1873), 2:75, https://bibnum.obspm.fr/ark:/11287/2BfGK. In his 1867 paintings realized from the balcony of the Louvre (Quai du Louvre and Garden of the Princess; see fig. 4), Monet capitalized on the crowds who were in town that summer for the International Exposition. He planned for this again in 1878, when he obtained permission to paint from two different balconies in an effort to capture the national holiday in celebration of France’s recovery from the war with Prussia. The paintings are The Rue Montorgeuil, 30th of June 1878 (1878; Musée d’Orsay, Paris) and The Rue Saint-Denis 30th of June 1878 (1878; Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rouen). And what a stroke of marketing genius to show them from the very vantage point of his forthcoming exhibition venue!

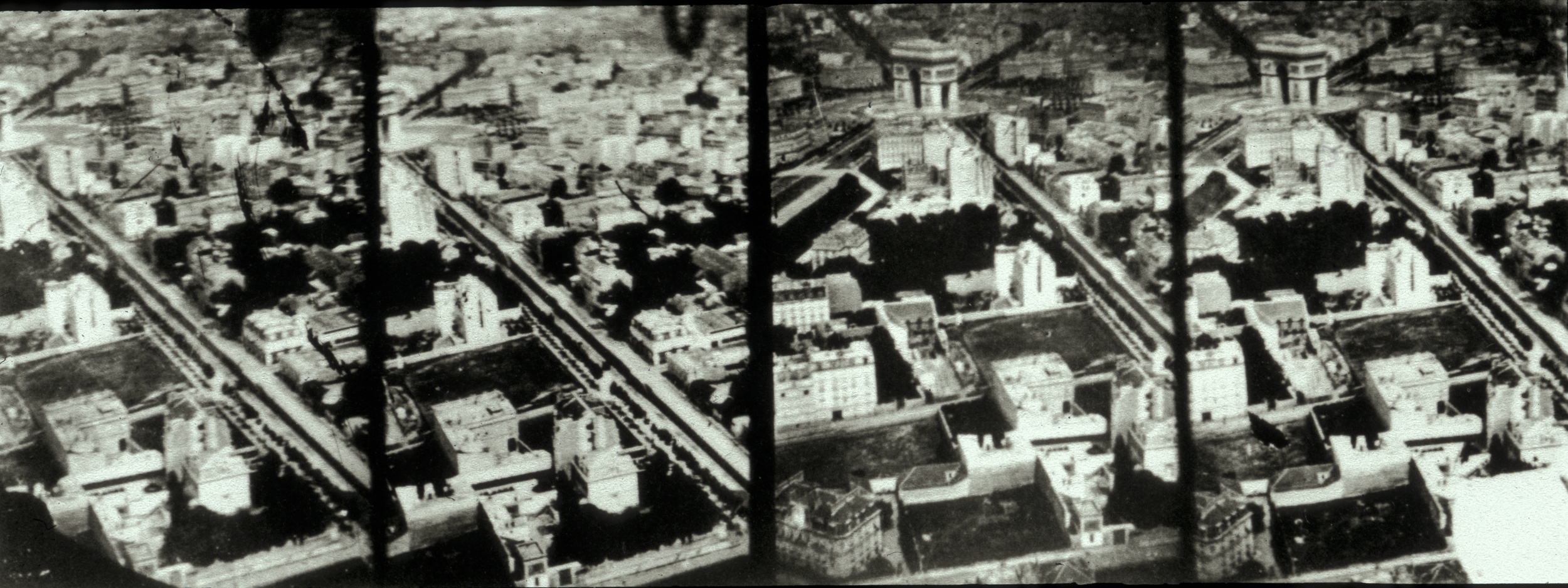

Fig. 2. Félix Nadar, Aerial View of the Arc de Triomphe, 1868, wet collodion print, in Walter Benjamin, “Paris: Capital of the 19th Century,” Arcades Project, Brown Digital Repository. Brown University Library

Fig. 2. Félix Nadar, Aerial View of the Arc de Triomphe, 1868, wet collodion print, in Walter Benjamin, “Paris: Capital of the 19th Century,” Arcades Project, Brown Digital Repository. Brown University Library

Possibly Hippolyte Jouvin, Boulevard des Capucines, Paris, early/mid-1860s, double frame albumen silver print from a stereoscopic photograph, 21 1/2 x 10 15/16 in. (54.6 x 27.7 cm). Photo: Artokoloro/Alamy Stock Photo

Possibly Hippolyte Jouvin, Boulevard des Capucines, Paris, early/mid-1860s, double frame albumen silver print from a stereoscopic photograph, 21 1/2 x 10 15/16 in. (54.6 x 27.7 cm). Photo: Artokoloro/Alamy Stock Photo

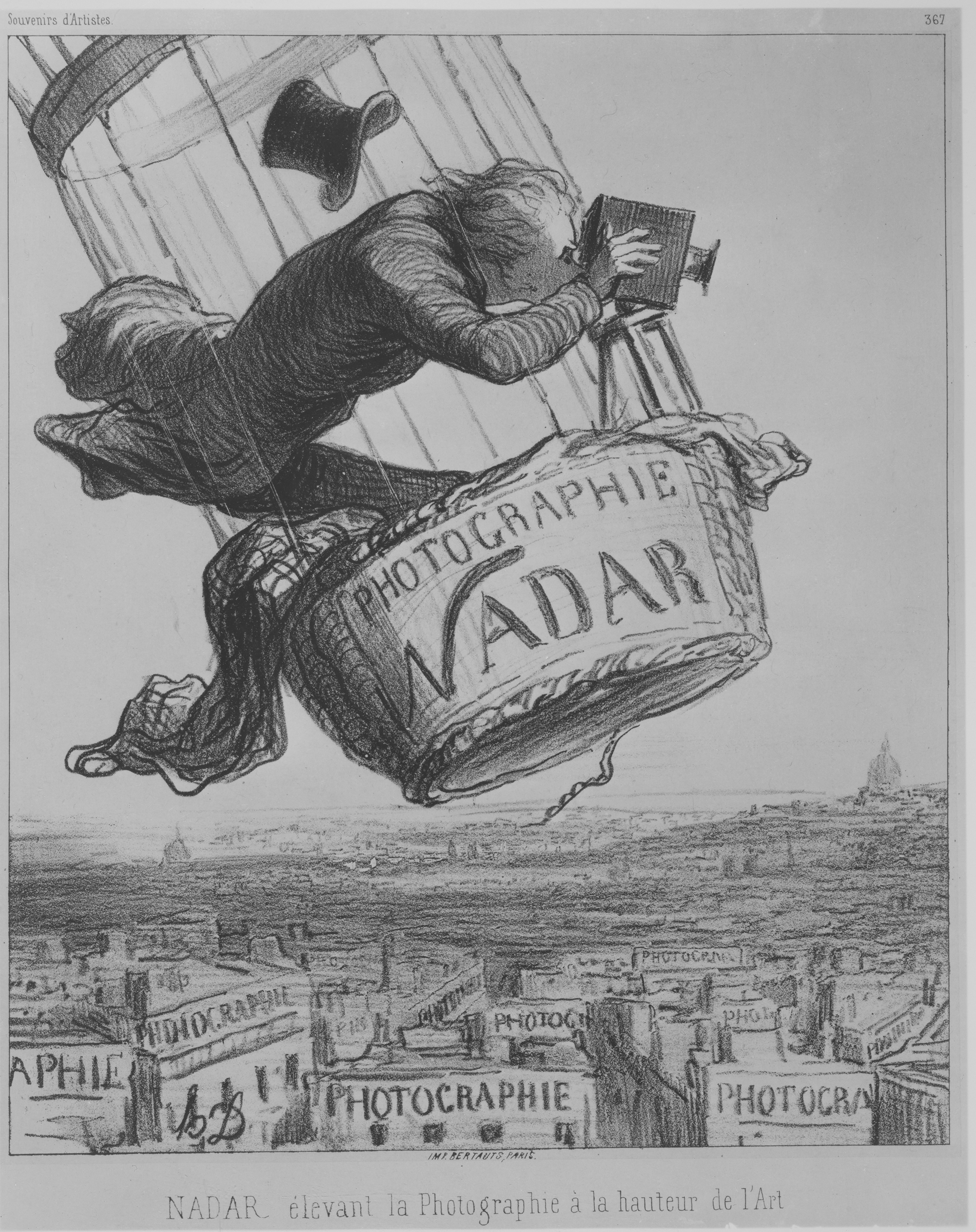

After nine years of struggling to gain acceptance into the SalonSalon, the: Exhibitions organized by the French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture (Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture) and its successor the Academy of Fine Arts (Académie des Beaux Arts), which took place in Paris from 1667 onward. as fine art rather than being relegated to exhibitions of industrial products, photography as a medium was officially accepted into the Salon in 1859, and it was both commercially and artistically successful.21For more on the history of photography and its relationship to Impressionism, see Alarcó, The Impressionists and Photography, 19–28. Many of the young Impressionists, including Monet, were in a similar position of wanting and needing acceptance into the Salon, both as a stamp of official approval and as a place to show their work. Yet by the early 1870s Monet was not having much success on either of these fronts; in fact, he was regressing.22In 1865, Monet submitted two works to the Salon and gained one acceptance. He continued to submit to the Salons of 1867, 1868, 1869, and 1870, with only one painting accepted, in 1868. As has been shown by Virginia Spate, Monet had some success selling a number of pictures to Paul Durand-Ruel and a few other collectors in 1872–73; however, these were generally more conservative paintings, not the type of subject matter or approach to figure and form as seen in Monet’s Boulevards paintings. See Virginia Spate, Claude Monet: The Color of Time (London: Thames and Hudson, 1992), 89. By the mid-1870s, he was struggling to sell fully developed and finished paintings to dealers, so he adopted a different strategy by selling sketches, likely including the Nelson-Atkins Boulevard des Capucines.23As Simon Kelly has shown, it is possible that Monet was making a “thoughtful attempt to tap into an established market for landscape etudes and esquisses dating back several decades at least until the start of the century.” I am extremely grateful to Kelly, who shared his insight on this aspect of Monet’s marketing strategy, as discussed in his unpublished paper, “Monet and Commercial Strategy” (presented at the Musée d’Orsay, 2009). Similarly, Nadar deftly pivoted from one strategy to another to garner attention for his works, including installing ten-foot-high red neon letters spelling out his name on his building, not only to attract attention but to signal he was a pioneer in his use of electric light. Monet thought of the perennial publicist when developing a strategy to counteract his own plight. He recalled: “For some time, my friends and I had been systematically rejected by the abovementioned jury. What were we to do? It’s not just about painting, you’ve got to sell, you’ve got to live. The dealers didn’t want anything to do with us. We needed to show our work, but where? Nadar, the great Nadar, who is so kind, lent us his place.”24Émile Taboureaux, “Claude Monet,” La Vie Moderne (June 12, 1880): 380–82, quoted in Lionel Venturi, Les Archives de l’Impressionnisme. Lettres de Renoir, Monet, Pissarro, Sisley et autres. Mémoirs de Paul Durand-Ruel (New York: Burt Franklin, 1968), 2:340.

Notes

-

While many of the contemporary reviews of the 1874 exhibition could conceivably apply to both pictures, hence the long debate over which canvas was exhibited, an English review by Frederick Wedmore noted that “Claude Monet sends the ‘Boulevard des Capucines’ a rough oil sketch some four feet long.” This measurement must refer to a framed dimension and could only relate to the width of the horizontal Pushkin canvas, as the framed height of the Nelson-Atkins Boulevard is 43 3/8 in. See Frederick Wedmore, “Pictures in Paris: The Exhibition of ‘Les Impressionistes’,” The Examiner (June 13, 1874): 633–34, as cited in Ed Lilley, “A Rediscovered English Review of the 1874 Impressionist Exhibition,” Burlington Magazine 154, no. 1317 (2012): 845.

-

See Patrice de Moncan, Les grandes boulevards de Paris: De la Bastille à la Madeleine (Paris: Les Éditions de Mécène, 1997), 348–63, cited in Simon Kelly and April M. Watson, Impressionist France: Visons of Nation from Le Gray to Monet, exh. cat. (St. Louis, MO: St. Louis Art Museum, 2013), 104. See also James H. Rubin, Impressionism and the Modern Landscape: Productivity, Technology, and Urbanization from Manet to Van Gogh (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008), 5–6, 10, 30–32, 36, 46–47, 160, 203n36, 235.

-

See the accompanying technical essay by Diana M. Jaskierny.

-

As per a note in the curatorial files, Charles de Meixmoron de Dombasle bought ten works from Monet in 1873. He acquired an additional three sketches in 1875. Although these are not individually enumerated, it is likely that the Nelson-Atkins Boulevard des Capucines was in the 1875 transaction. I am grateful to Simon Kelly, curator of modern and contemporary art, St. Louis Art Museum, for sharing information and his thoughts about the 1875 sale. See Monet’s entry under May 4, 1875, “M. de Dombasle / [illegible] / 3 esquisses 300 [francs]” (Monet’s livre de comptes, ventes janvier–juillet 1875, Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris. A photocopy of this page is in the curatorial object file, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art).

-

In the spring of 1874, following the first Impressionist exhibition, Jean- Baptiste Faure bought four works by Monet for 4,000 francs, including the Pushkin Boulevard des Capucines. The pricing structure of 1,000 francs per picture, suggests Monet considered this a finished work. For the notation of Monet’s account books, see Anne Distel, Impressionism: The First Collectors, trans. Barbara Perround-Benson (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1990), 84.

-

Daniel Wildenstein, Monet: Catalogue Raisonné; Werkverzeichnis, trans. Josephine Bacon (Cologne: Wildenstein Institute and Taschen, 1996), 2:124–25. The acceptance of the 1873 date is predicated not only on the inscription of the Pushkin picture but also early reviews of the Pushkin picture written during Monet’s lifetime by his friend, Gustave Geffroy. See Gustave Geffroy, “Chronique—Claude Monet,” La Justice (March 15, 1883): 2, and Gustave Geffroy, Claude Monet: Sa vie, son œuvre (Paris: G. Crès, 1922), 263. There was no snow in Paris in the fall of 1873, but there were several days of thick hoarfrost and frost, in November and December 1873, which could account for the white covering on the hansom cabs and ground in the Nelson-Atkins picture. It did not snow until February 9, 1874. See the Observatoire de la marine et du bureau des longitudes, Paris et Observatoire de Montsouris, Bulletin mensuel de l’Observatoire Physique Central de Monsouris (Paris: Gauthier-Villars, 1873/1874), https://bibnum.obspm.fr/ark:/11287/2BfGK and https://bibnum.obspm.fr/ark:/11287/VPTcP.

-

See Joel Isaacson, “Monet: Le Boulevard des Capucines en Carnival,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 20, no. 1 (Spring 2021): https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2021.20.1.3. Daniel Wildenstein believes Monet traveled to Amsterdam in the spring of 1874. See Daniel Wildenstein, Monet, or The Triumph of Impressionism (Cologne: Benedikt Taschen Verlag GmbH, 1996), 1:108–09.

-

Isaacson, “Monet: Le Boulevard des Capucines en Carnival.” Gustave Geffroy first made this connection to carnival in an 1883 review of the Pushkin picture at Durand-Ruel, a position he maintained along with the painting’s 1873 date in his 1922 biography, authored nearly twenty-five years into his friendship with Monet. See Geffroy, “Chronique—Claude Monet,” 2, and Geffroy, Claude Monet, 263, where he titled the Pushkin painting Le Boulevard des Capucines en Carnival.

-

For the weather in February 1873, see the Observatoire de la marine et du bureau des longitudes, Paris et Observatoire de Montsouris, (1873), 2:75, https://bibnum.obspm.fr/ark:/11287/2BfGK. In his 1867 paintings realized from the balcony of the Louvre (Quai du Louvre and Garden of the Princess; see fig. 4), Monet capitalized on the crowds who were in town that summer for the International Exposition. He planned for this again in 1878, when he obtained permission to paint from two different balconies in an effort to capture the national holiday in celebration of France’s recovery from the war with Prussia. The paintings are The Rue Montorgeuil, 30th of June 1878 (1878; Musée d’Orsay, Paris) and The Rue Saint-Denis 30th of June 1878 (1878; Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rouen).

-

For more on this effect, see Kermit S. Champa, Studies in Early Impressionism (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1973), 13, cited in Charles F. Stuckey, Claude Monet, 1840–1926, exh. cat. (New York: Thames and Hudson, 1995), 140.

-

Several of these formal characteristics, including the use of an elevated bird’s eye view, were also related to his familiarity with Japanese ukiyo-e prints by Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858) and Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849). However, the prints do not present the figures in a sketch-like manner as Monet did, nor as early contemporary photography did.

-

For more information about Nadar, see Maria Morris Hambourg, Françoise Heilbrun, and Paul Néagu, Nadar (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1995). See also Sharon Larson, “Rethinking Historical Authenticity: Photography, Nadar and Haussmann’s Paris,” Equinoxes: A Graduate Journal of French and Francophone Studies, no. 5 (spring/summer 2005), https://www.brown.edu/Research/Equinoxes/journal/Issue%205/eqx5_larson.htm; and Helene Bocard, Nadar (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009).

-

Paloma Alarcó, The Impressionists and Photography, exh. cat. (Madrid: Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, 2019), 159.

-

Cited in Watson’s catalogue entry for Hippolyte Jouvin. See Kelly and Watson, Impressionist France, nos. 19–20, p. 110.

-

Monet first adopted an elevated vantage point in his painting Garden at Saint-Adresse, 1867, oil on canvas, 38 5/8 x 51 1/8 in. (98.1 x 129.9 cm), Metropolitan Museum of Art, as noted in Charles S. Moffett, Impressionism: A Centenary Exhibition, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1974), 159.

-

Richard Thompson, Monet and Architecture, exh. cat. (London: National Gallery, 2018), 92.

-

For an example of a work produced by Le Gray from this vantage point, see Gustave Le Gray, Panorama de Paris, vers le Pont Neuf, about 1859, albumen collodion print on glass, 15 3/4 x 20 1/8 in. (40 x 51 cm), Musée d’Orsay, Paris, 1985.129, cited in Thompson, Monet and Architecture, 92.

-

George T. M. Shackelford, “Painter of Modern Life: Monet and the City,” in Claude Monet: The Truth of Nature, exh. cat. Denver Art Museum (New York: Prestel, 2019), 52.

-

Shackelford, “Painter of Modern Life,” 52.

-

Shackelford, “Painter of Modern Life,” 52–53.

-

For more on the history of photography and its relationship to Impressionism, see Alarcó, The Impressionists and Photography, 19–28.

-

In 1865, Monet submitted two works to the Salon and gained one acceptance. He continued to submit to the Salons of 1867, 1868, 1869, and 1870, with only one painting accepted, in 1868. As has been shown by Virginia Spate, Monet had some success selling a number of pictures to Paul Durand-Ruel and a few other collectors in 1872–73; however, these were generally more conservative paintings, not the type of subject matter or approach to figure and form as seen in Monet’s Boulevards paintings. See Virginia Spate, Claude Monet: The Color of Time (London: Thames and Hudson, 1992), 89.

-

As Simon Kelly has shown, it is possible that Monet was making a “thoughtful attempt to tap into an established market for landscape etudes and esquisses dating back several decades at least until the start of the century.” I am extremely grateful to Kelly, who shared his insight on this aspect of Monet’s marketing strategy, as discussed in his unpublished paper, “Monet and Commercial Strategy” (presented at the Musée d’Orsay, 2009).

-

Émile Taboureaux, “Claude Monet,” La Vie Moderne (June 12, 1880): 380–82, quoted in Lionel Venturi, Les Archives de l’Impressionnisme. Lettres de Renoir, Monet, Pissarro, Sisley et autres. Mémoirs de Paul Durand-Ruel (New York: Burt Franklin, 1968), 2:340.

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Diana M. Jaskierny, “Claude Monet, Boulevard des Capucines, 1873—1874,” technical entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.626.2088

MLA:

Jaskierny, Diana M. “Claude Monet, Boulevard des Capucines, 1873—1874,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.626.2088.

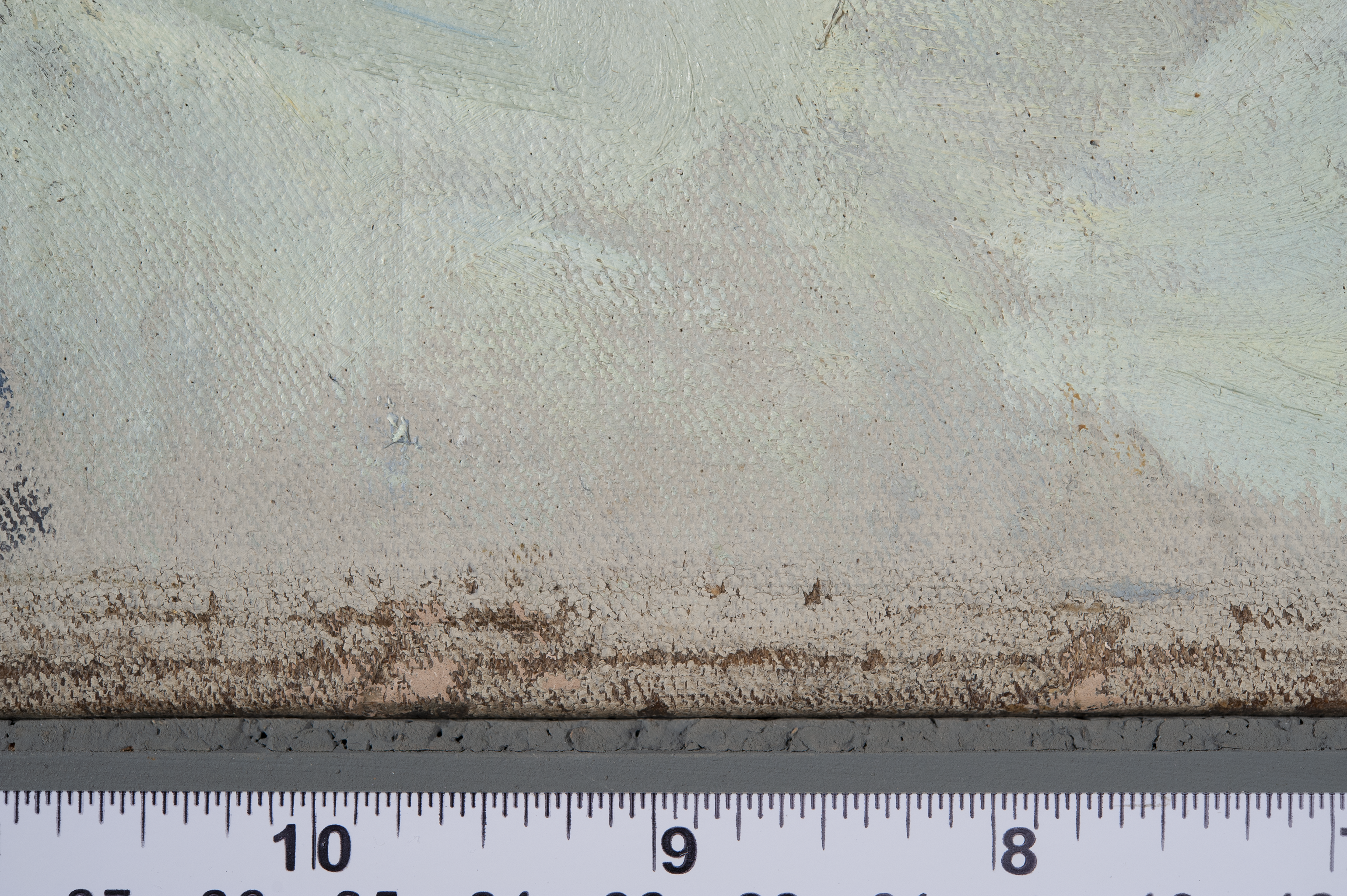

Throughout the paint layer, a variety of applications are found, ranging from thin and dry brushwork to more heavily applied “dabs” within figures and highlights. Overall, there is limited low impastoimpasto: A thick application of paint, often creating texture such as peaks and ridges., and each compositional element’s handling varies from the next, creating depth and a sense of atmospheric perspectiveatmospheric perspective: An artistic technique used to create the illusion of depth in a composition in which distant elements are cooler and more diffuse, causing them to recede.. There is no apparent underdrawingunderdrawing: A drawn or painted sketch beneath the paint layer. The underdrawing can be made from dry materials, such as graphite or charcoal, or wet materials, such as ink or paint. or underpaintingunderpainting: The first applications of paint that begin to block in color and loosely define the compositional elements. Also called ébauche. visible in standard viewing light, nor is one detected in infrared reflectographyinfrared reflectography (IRR): A form of infrared imaging that exploits the behavior of painting materials at wavelengths beyond those accessible to infrared photography. These advantages sometimes include a continuing increase in the transparency of pigments beyond wavelengths accessible to infrared photography (i.e, beyond 1,000 nanometers), rendering underdrawing more clearly. The resulting image is called an infrared reflectogram. Devices that came into common use in the 1980s such as the infrared vidicon effectively revealed these features but suffered from lack of sharpness and uneven response. Vidicons continue to be used out to 2,200 nanometers but several newer pixelated detectors including indium gallium arsenide and indium antimonide array detectors offer improvements. All of these devices are optimally used with filters constraining their response to those parts of the infrared spectrum that reveal the most within the constraints of the palette used for a given painting. They can be used for transmitted light imaging as well as in reflection..7The painting was examined with a Hamamatsu infrared vidicon camera. The order in which the compositional elements were painted is difficult to determine, as it appears Monet revisited sections numerous times. The center of the composition is especially sketchy and dry-brushed. The sky and pale foreground seem to have been thinly laid-in first, with reservereserve: An area of the composition left unpainted with the intention of inserting a feature at a later stage in the painting process. areas for the trees silhouetted against the sky and select figures in the foreground. In these instances, some boundaries of the sky and foreground are slightly overpainted with trees and figures, respectively, while generous amounts of exposed ground remain. Monet returned to add paint in the sky, occasionally pulling the brush over tree elements and chimneys in a scumblescumble: A thin layer of opaque or semi-opaque paint that partially covers and modifies the underlying paint. (Fig. 9).

Fig. 10. Detail of wet-over-wet technique between the figures and foreground in the lower right of the central group, Boulevard des Capucines (1873-1874), indicated with a purple arrow. The green outline indicates reserve area and exposed ground around figures.

Fig. 10. Detail of wet-over-wet technique between the figures and foreground in the lower right of the central group, Boulevard des Capucines (1873-1874), indicated with a purple arrow. The green outline indicates reserve area and exposed ground around figures.

Fig. 11. Detail of figures painted over the foreground without reserves, Boulevard des Capucines (1873-1874)

Fig. 11. Detail of figures painted over the foreground without reserves, Boulevard des Capucines (1873-1874)

The foreground was partially wet when figures were placed in their reserves, as can be seen in the lower right section of Figure 10. Here deep blue of the figures has been pulled through the adjacent cool-toned foreground, while the warm ground layer peeks through both the figures and the foreground. Additionally, although there were reserves left for some figures, many were painted on top of the then dried foreground, with no reserve or surrounding exposed ground (Fig. 11). This indicates that while some figures were clearly anticipated in the early stages of painting, others were added by Monet later in the painting process as he finalized the composition. In both instances, and throughout the painting, many compositional elements were painted with a light touch, allowing the paint to only skim the canvas weave tops and skip the twill interstices, revealing a variety of layers beneath (Fig. 10). Anthea Callen described this as giving “shimmering effects that evoke both the wintery atmosphere and the sensation of distance from a high viewpoint [. . . ].”8Callen, The Art of Impressionism: Painting Technique and the Making of Modernity, 41. Highlights, such as on the carriages, were among the last painted, with a thicker application and with some strokes blending wet-over-wetwet-over-wet: An oil painting technique which involves drawing a stroke of one color across the wet paint of another color. with surrounding paint that had not quite dried (Fig. 12).

Fig. 12. Detail of carriages, Boulevard des Capucines (1873-1874)

Fig. 12. Detail of carriages, Boulevard des Capucines (1873-1874)

Fig. 13. Detail in raking light, illustrating canvas weave interference, Boulevard des Capucines (1873-1874)

Fig. 13. Detail in raking light, illustrating canvas weave interference, Boulevard des Capucines (1873-1874)

The painting has undergone at least three conservation treatments. It originally entered the collection with a glue-based lining that was removed and replaced in 1972 with a wax-based lining.9Roth, treatment report, 1972. While the original canvas is twill weave, a secondary vertical weave pattern is visible, likely weave interferenceweave interference: A distortion that can occur when excess heat or pressure is applied to a painting, usually during the lining process. As a result, the original canvas weave texture becomes more pronounced or the weave texture of the lining material becomes visible on the painting surface. Also called weave emphasis or weave accentuation. caused by an early lining fabric (Fig. 13).10The current lining material does not display this vertical texture. Labeled samples of the lining material removed in 1972 were retained in the object file, but also do not have a pronounced weave pattern that might have caused the vertical pattern. As neither the lining material removed in 1972 nor the current lining material added that same year have this pronounced pattern, it is likely that the treatment history of the painting included an even earlier lining. Areas of low impasto were slightly flattened during one of the lining processes. In 2006, the painting was cleaned, and a low-concentration synthetic varnish was applied in order to maintain a relatively “unvarnished” appearance while suitably saturating the paint layer.11Scott Heffley, September 29, 2006, treatment report, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, no. F72-35.

Losses to the ground layer and subsequently paint layer are present throughout the painting, often forming horizontal cracks, and may relate to the painting’s lining or lining reversal history. In the 1972 condition report prior to treatment, the paint was noted as being friablefriable: When paint is no longer sufficiently bound. Friable paint often appears powdery or crumbles easily. and flaking, indicating that some loss pre-dates that lining reversal. The ground and paint layers are now stable, with no new flaking or delaminationdelamination: The separation of layers in a painting. Examples include separation of the original canvas from the lining canvas, or separation of the paint layer from the ground layer. visible. Overall there is minimal retouchingretouching: Paint application by a conservator or restorer to cover losses and unify the original composition. Retouching is an aspect of conservation treatment that is aesthetic in nature and that differs from more limited procedures undertaken solely to stabilize original material. Sometimes referred to as inpainting or retouch., with the majority found in the lower half and along the edges. There are areas that appear to be abrasionsabrasion: A loss of surface material due to rubbing, scraping, frequent touching, or inexpert solvent cleaning., but because of the dry-brush application, it is often difficult to differentiate between possible abrasion and Monet’s technique.

Notes

-

David Bomford, Jo Kirby, John Leighton, and Ashok Roy, Art in the Making: Impressionism (London: Yale University Press, 1991), 144–45. See also Anthea Callen, The Art of Impressionism: Painting Technique and the Making of Modernity (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 104–05.

-

James Roth, December 14, 1972, treatment report, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, no. F72-35.

-

Roth, treatment report, 1972.

-

Monet was known for using colored or tinted grounds during the 1870s, some of which may have been applied by Ottoz, others by the artist himself. Without sampling, it is unclear on this painting if there is one tinted ground or two thinly applied grounds with the upper layer being tinted. Callen, The Art of Impressionism: Painting Technique and the Making of Modernity, 70–73. See also Bomford et al., Art in the Making: Impressionism, 145.

-

Bomford et al., Art in the Making: Impressionism, 88. For a larger discussion on Monet’s use of color and simultaneous contrast see pages 87–89.

-

While Monet often used simultaneous contrast within the paint layer, his use of the ground layer to amplify colors, as seen here in Boulevard des Capucines, can also be found in The Beach at Trouville (1870; National Gallery, London) and The Petit Bras of the Seine at Argenteuil (1872; National Gallery, London). See Bomford et al., Art in the Making: Impressionism, 129–30, 144–45.

-

The painting was examined with a Hamamatsu infrared vidicon camera.

-

Callen, The Art of Impressionism: Painting Technique and the Making of Modernity, 41.

-

Roth, treatment report, 1972.

-

The current lining material does not display this vertical texture. Labeled samples of the lining material removed in 1972 were retained in the object file, but also do not have a pronounced weave pattern that might have caused the vertical pattern. As neither the lining material removed in 1972 nor the current lining material added that same year have this pronounced pattern, it is likely that the treatment history of the painting included an even earlier lining.

-

Scott Heffley, September 29, 2006, treatment report, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, no. F72-35.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Claude Monet, Boulevard des Capucines, 1873—1874,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.626.4033

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Claude Monet, Boulevard des Capucines, 1873—1874,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.626.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Claude Monet, Boulevard des Capucines, 1873—1874,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.626.4033

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Claude Monet, Boulevard des Capucines, 1873—1874,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.626.4033.

Purchased from the artist by Charles Vaillant de Meixmoron de Dombasle (1839–1912), Diénay, France, 1875–1912 [1];

Inherited by his widow, Mme. de Meixmoron de Dombasle (née Lucie Marie Emma de Maillart de Landreville, 1848–1932), Diénay, France, 1912–1919;

Purchased from Mme. de Meixmoron de Dombasle by Bernheim-Jeune et Cie, Paris, stock no. 21631, June 22, 1919–November 15, 1919 [2];

Purchased from Bernheim-Jeune et Cie by Alex Reid, Glasgow, November 15, 1919–January 2, 1920;

Purchased from Reid by Mr. Robert Alfred and Mrs. Elizabeth Russe (née Allan, 1874–ca. 1937) Workman, Esq., London, January 2, 1920 [3];

Returned by the Workmans to Alex Reid, Glasgow;

Purchased from Reid by Knoedler and Company, London, Stock Book, No. 7206, January 3, 1924;

Transferred from Knoedler, London, to Knoedler, New York, Stock Book 7, No. 15819, November 21, 1924–January 23, 1925;

Purchased from Knoedler by James Horace Harding (1863–1929), New York, January 23, 1925;

Inherited by his widow, Dorothea Harding (née Barney, 1871–1935), Rumson, NJ, by 1929 [4];

With Knoedler and Company, New York, March 7–October 15, 1935 [5];

Transferred from Knoedler to Carroll Carstairs Gallery, New York, October 15, 1935–by April 11, 1945 at the latest [6];

Purchased from the Estate of Dorothea Harding, through Carroll Carstairs Gallery, New York, by “a private collector in America,” by April 11, 1945 [7];

Marshall Field III (1893–1956), Lloyd’s Neck, NY, and Chicago, by April 11, 1945–November 8, 1956 [8];

Inherited by his widow, Mrs. Marshall Field III (née Ruth Pruyn Phipps, 1908–1994), Lloyd’s Neck, NY, and New York City, 1956–December 4, 1972 [9];

Purchased from Mrs. Marshall Field III, through E. V. Thaw and Co., Inc, New York, by The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri, 1972.

Notes

[1] According to Impressionnisme en Lorraine, exh. cat. (Nancy: Musée des Beaux-Arts, 1975), the painting was bought by Meixmoron de Dombasle in 1875 from Claude Monet and was in Meixmoron’s collection until his death in 1912.

[2] See letter from Bernheim-Jeune et Cie to Glynnis Napier Stevenson, NAMA, October 17, 2017, NAMA curatorial files. Durand-Ruel, Paris, purchased a half share of the painting from Bernheim-Jeune on June 23, 1919, and then sold their share back to Bernheim-Jeune on January 7, 1920. Durand-Ruel stock number was 11519. See email from Paul-Louis Durand-Ruel and Flavie Durand-Ruel, Durand-Ruel et Cie, Paris, to Nicole Myers, NAMA, curatorial file.

[3] Tate Britain, London, Alex Reid and Lefèvre archives, “1913–1920 Daybook,” TGA 2002/11/279.

[4] The painting was not sold in James Horace Harding’s estate sales of 1941. According to the Frick Collection, where James Horace Harding was on the Board of Trustees, there’s nothing in his correspondence related to the Nelson-Atkins picture. The Frick suspects that the painting was inherited by his widow, who inherited her husband’s estate, and then sold after her death in 1935. See email from Eugenie Fortier, Frick Art Reference Library Archives, New York, to Glynnis Napier Stevenson, NAMA, April 3, 2017, NAMA curatorial files.

[5] See Knoedler label numbered 24721 on verso. The Estate of Mrs. Dorothea Horace Harding had the painting delivered to Knoedler on March 7, 1935. Upon receipt, Knoedler decided to retain the picture on commission rather than purchase it from the estate. See email Karen Mayer-Roux, Archivist, Special Collections, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, to Glynnis Napier Stevenson, NAMA, October 11, 2019, NAMA curatorial files.

[6] Knoedler transferred the picture to Carroll Carstairs, New York. Knoedler Commission Book 3, Folio 69, CA 802, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles. See also M. Knoedler and Co. records, approximately 1848–1971. Series IV. Inventory cards, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles.

[7] According to The Frick Art Reference Library, New York, Photo Archives, artist file for Claude Monet (1840–1926), “Boulevard des Capucines”: “…after ownership by J. Horace Harding, the painting was sold by Carroll Carstairs Gallery, New York, to a private collector in America, then acquired by Mr. and Mrs. Marshall Field III, circa 1945.” See email from Eugenie Fortier, Frick Art Reference Library Archives, New York, to Glynnis Napier Stevenson, NAMA, April 3, 2017, NAMA curatorial files.

[8] Boulevard des Capucines hung in the living room at the Fields’ Caumsett Estate in Lloyd Harbor, Long Island. See Matthew Bessell, Caumsett: The home of Marshall Field III in Lloyd Harbor, New York (Huntington, NY: Huntington Town Board, 1991), 51n48.

[9] Following the death of her husband in 1956, Field moved to an apartment in New York City. The Caumsett Estate was purchased by New York State on February 3, 1961 and converted into a state park. Though she sold off much of the art she inherited, Boulevard des Capucines was in her New York apartment when she sold the painting to The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art through E.V. Thaw, New York in 1972. See letter from E.V. Thaw and Co., Inc. to Mr. Ralph T. Coe, NAMA, November 21, 1974, NAMA curatorial files. Previous scholars confused Mrs. Marshall Field III and Mrs. Marshall Field IV. According to Matthew Bessell, Caumsett: The home of Marshall Field III in Lloyd Harbor, New York, Boulevard des Capucines was among the pictures inherited by Ruth Field after her husband’s death (p. 25). Ralph T. Coe states that the painting was owned by Ruth Field before being bought by NAMA; see Ralph T. Coe, “Claude Monet’s ‘Boulevard des Capucines’: After a Century,” Bulletin (The Nelson Gallery and Atkins Museum) 5, no. 3 (February 1976). Eugene Victor Thaw confirmed that the painting was purchased directly from Mrs. Marshall Field III not Mrs. Marshall Field IV; see letter from E.V. Thaw and Co. to Meghan Gray, NAMA, July 14, 2011, NAMA curatorial files.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Claude Monet, Boulevard des Capucines, 1873—1874," documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.626.4033

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Claude Monet, Boulevard des Capucines, 1873—1874,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.626.4033.

Claude Monet, Boulevard des Capucines, 1873, oil on canvas, 24 x 31 1/2 in. (61 x 80 cm), Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow.

Copies

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Claude Monet, Boulevard des Capucines, 1873—1874,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.626.4033

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Claude Monet, Boulevard des Capucines, 1873—1874,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.626.4033.

Charles de Meixmoron de Dombasle, after Claude Monet, Boulevard des Capucines, ca. 1875–1912, oil on cardboard, 127 3/16 x 88 9/16 in. (323 x 225 cm), private collection, France.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Claude Monet, Boulevard des Capucines, 1873—1874,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.626.4033

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Claude Monet, Boulevard des Capucines, 1873—1874,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.626.4033.

Exposition des Peintres de l’École française du XIXe Siècle, Knoedler and Company, Paris, opened May 12, 1924, no. 42, as Les Grands Boulevards.

The 1870s in France, Carroll Carstairs Gallery, New York, December 1938, no cat., as Les Grands Boulevards.

A Loan Exhibition of Paintings by Claude Monet for the Benefit of the Children of Giverny, Wildenstein, New York, April 11–May 12, 1945, no. 17, as Les Grands Boulevards.

“What they said”: Postscript to Art Criticism For the benefit of the Museum of Modern Art on its 20th Anniversary, Durand-Ruel Galleries, New York, November 28–December 17, 1949, no. 4, as Boulevard des Capucines.

Great French Paintings: An Exhibition in Memory of Chauncey McCormick, Art Institute of Chicago, January 20–February 20, 1955, no. 26, as Les Grands Boulevards.

Masterpieces of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist Painting, National Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, April 25–May 24, 1959, unnumbered, as Boulevard des Capucines.

Olympia’s Progeny; French Impressionist and Post-Impressionist Paintings (1865–1905), Wildenstein, New York, October 28–November 27, 1965, no. 12, as Boulevard des Capucines.

Four Masters of Impressionism: For the Benefit of The Lenox Hill Hospital New York, Acquavella Galleries, New York, October 24–November 30, 1968, no. 10, as Boulevard des Capucines, Paris.

“One Hundred Years of Impressionism:” A Tribute to Durand-Ruel: A Loan Exhibition for the Benefit of the New York University Art Collection, Wildenstein, New York, April 2–May 9, 1970, no. 18, as Boulevard des Capucines.

Centenaire de l’Impressionnisme, Grand Palais, Paris, September 21–November 24, 1974; Impressionism: A Centenary Exhibition, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, December 12, 1974–February 10, 1975, no. 30, as Boulevard des Capucines, Paris.

Paintings by Monet, The Art Institute of Chicago, March 15–May 11, 1975, no. 36, as Boulevard des Capucines.

City Views, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, May 31–July 10, 1983, no. 38A, as Paris. Boulevard des Capucines.

The New Painting: Impressionism 1874–1886, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, January 17–April 6, 1986; The Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, M. H. de Young Memorial Museum, April 19–July 6, 1986, no. 7, as Boulevard des Capucines.

Impressionism: Selections from Five American Museums, The Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, November 4–December 31, 1989; The Minneapolis Institute of Arts, January 27–March 25, 1990; The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, April 21–June 17, 1990; Saint Louis Art Museum, July 14–September 9, 1990; The Toledo Museum of Art, September 30–November 25, 1990, no. 49, as Boulevard des Capucines.

Monet: A Retrospective, Bridgestone Museum of Art, Tokyo, February 11–April 7, 1994; Nagoya City Art Museum, April 16–June 12, 1994; Hiroshima Museum of Art, June 18–July 31, 1994, no. 19, as Le boulevard des Capucines.

Claude Monet: 1840–1926, The Art Institute of Chicago, July 22–November 26, 1995, no. 39, as Boulevard des Capucines.

Impressionists in Winter: Effets de Neige, The Phillips Collection, Washington, D. C., September 19, 1998–January 3, 1999; Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco, January 30–May 2, 1999, no. 8, as Boulevard des Capucines.

Tempus Fugit: Time Flies, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, October 15–December 31, 2000, no. II.7, as Boulevard des Capucines.

Monet and Japan, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, March 9–June 11, 2001; Art Gallery of Western Australia, Perth, July 7–September 16, 2001, no. 7, as Boulevard des Capucines.

Becoming Edvard Munch: Influence, Anxiety, and Myth, The Art Institute of Chicago, February 14–April 26, 2009, no. 127, as The Boulevard des Capucines.

Impressionist France: Visions of Nation from Le Gray to Monet, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, October 19, 2013–February 9, 2014; Saint Louis Art Museum, March 16–July 6, 2014, no. 15, as Boulevard des Capucines.

Impression, soleil levant: l’histoire vraie du chef-d’oeuvre de Claude Monet, Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris, September 18, 2014–January 18, 2015, no. 47, as Le Boulevard des Capucines.

Monet and the Birth of Impressionism, Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main, March 11–June 21, 2015, no. 61, as The Boulevard des Capucines / Le Boulevard des Capucines.

Unfinished: Thoughts Left Visible, The Met Breuer, New York, March 1–September 4, 2016, no. 109, as Boulevard des Capucines.

Claude Monet: The Truth of Nature, Denver Art Museum, October 21, 2019–February 2, 2020; Museum Barberini, Potsdam, February 1–May 30, 2020, no. 18 (Denver only), as The Boulevard des Capucines.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Claude Monet, Boulevard des Capucines, 1873—1874,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.626.4033

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Claude Monet, Boulevard des Capucines, 1873—1874,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.626.4033.

E[rnest] Renart, Dictionnaire Biographique International des Collectionneurs (Paris: Imprimerie de l’Armorial Français, 1895), 22.

Emile Maton, Dictionnaire Biographique International des Artistes (Paris: Imprimerie de l’Armorial Français, 1901), 32.

Marc Elder, A [sic] Giverny, chez Claude Monet (Paris: Bernheim-Jeune, 1924), 85, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

Camille Mauclair, Claude Monet, 2nd ed. (1924; Paris: Les Éditions Rieder, 1927), 40, (repro.), as Le Boulevard, The boulevard, Der Boulevard, Il corso, and El “Boulevard”.

Exposition des Peintres de l’École française du XIXe Siècle, exh. cat. (Paris: Knoedler, 1924), 13, as Les Grands Boulevards.

Raymond Régamey, “La Formation de Claude Monet,” Gazette des Beaux-Arts (February 1927): 82, as Boulevard des Capucines.

Xenia [de Tunzelman Bootle-Wilbraham] Lathom, Claude Monet (London: Phillip Allan, 1931), 64, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines and Le Boulevard.

Alfred M. Frankfurter, “Panorama of a Great Decade: ‘The 1870s’,” Art News 37, no. 10 (December 3, 1938): 10, 12, (repro.), as Les Grands Boulevards.

Maurice Malingue, Claude Monet (Monaco: Les Documents d’Art, 1943), 61, 146, (repro.), as Le Boulevard.

Possibly Camille Mauclair, Claude Monet et l’impressionnisme (Paris: J. Renard, 1943), 45, as Boulevards.

A Loan Exhibition of Paintings by Claude Monet for the Benefit of the Children of Giverny, exh. cat. (New York: Wildenstein, 1944), 28, 31, (repro.), as Les Grands Boulevards.

John Rewald, The History of Impressionism, rev. 4th ed. (1946; New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1973), 320–22, 324, 326, 340n30, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines, Paris.

Oscar Reuterswärd, Monet: En konstnärshistorik (Stockholm: Albert Bonniers Förlag, 1948), 70–72, 76, 81, 281, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines i snö.

“What they said”: Postscript to Art Criticism For the benefit of the Museum of Modern Art on its 20th Anniversary, exh. cat. (New York: Durand-Ruel, 1949), unpaginated, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

Great French Paintings: An Exhibition in Memory of Chauncey McCormick, exh. cat. (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 1955), unpaginated, (repro.), as Les Grands Boulevards.

Jean Leymarie, Impressionism: Biographical and Critical Study, vol. 2, trans. James Emmons (Lausanne, Switzerland: Skira, 1955), 60–61, 64, 132, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines, Paris.

Isabel Stevenson Monro and Kate M. Monro, Index to Reproductions of European Paintings: A guide to pictures in more than three hundred books (New York: H. W. Wilson, 1956), 425.

Claude Monet: An exhibition of paintings arranged by the Arts Council of Great Britain in association with the Edinburgh Festival Society, exh. cat. (London: Tate Gallery, 1957), 11, 22, as Boulevard des Capucines.

Denis Rouart, Claude Monet, trans. James Emmons (Geneva: Éditions d’Art Albert Skira, 1958), 52–53.

Masterpieces of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist Painting, exh. cat. (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1959), 36, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

Ralph T. Coe, “Impressionist and Post-Impressionist Paintings in Washington,” Burlington Magazine 101, no. 675 (June 1959): 245, as Boulevard des Capucines.

William C[hapin] Seitz, Claude Monet (New York: Harry N. Abrams, [1960]), 92, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

Aaron Scharf, “Painting, Photography, and the Image of Movement,” Burlington Magazine 104, no. 710 (May 1962): 188, 190, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

Jean Leymarie, French Painting: The Nineteenth Century, trans. James Emmons (Geneva: Éditions d’Art Albert Skira, 1962), 158, 189, 229, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines, Paris.

Denis Rouart and Thérèse Charpentier, Charles de Meixmoron: 1839–1912, exh. cat. (Nancy: Musée des Beaux Arts, 1962), unpaginated.

Henry A. La Farge, “Independence through Interdependence,” Art News 64, no. 7 (November 1965): 50–51, 66, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

Olympia’s Progeny: French Impressionist and Post-Impressionist Paintings (1865–1905), exh. cat. (New York: Wildenstein, 1965), unpaginated, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

John Rewald, Die Geschichte des Impressionismus: Schicksal und Werk der Maler einer grossen Epoche der Kunst (Cologne: Verlag M. DuMont Schauberg, 1965), 138–39, 196, 198, 399, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines, Paris.

S[amuel] C. Burchell, Age of Progress, vol. 11 (New York: Time, 1966), 62, (repro.).

Charles Merrill Mount, Monet (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1966), 233–34, 430, as Boulevard des Capucines.

Margaretta M. Salinger, Claude Monet (1840–1926) (New York: Harry N. Abrams, [1966]), unpaginated, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

H[jorvardur] H[arvard] Arnason and Peter Kalb, History of Modern Art: Painting, Sculpture, Architecture, Photography, 5th ed. (1968; Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2004), 31–32, 36, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines, Paris (Les Grands Boulevards).

Marie Berhaut, Caillebotte: The Impressionist, trans. Dana Imber (Lausanne: International Art Book, 1968), 30, 34, as Boulevard des Capucines.

Four Masters of Impressionism: For the Benefit of the Lenox Hill Hospital New York, exh. cat. (New York: Acquavella Galleries, 1968), unpaginated, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines, Paris.

Richard W. Murphy, The World of Cézanne: 1839–1906 (1968; New York: Time-Life Books, 1971), 58, 64–65, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

Aaron Scharf, Art and Photography, rev. ed. (1968; Harmondsworth, United Kingdom: Penguin, 1974), 170–72, 352, 383, 394, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

“One Hundred Years of Impressionism”: A Tribute to Durand-Ruel; A Loan Exhibition for the Benefit of the New York University Art Collection, exh. cat. (New York: Wildenstein, 1970), (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

Phoebe Pool, Impressionism (London: Thames and Hudson, 1970), 16–17, 117, 272, 284, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

“Departmental Accessions,” Annual Report of the Trustees of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, no. 102 (July 1, 1971–June 30, 1972): 41, as Boulevard des Capucines.

Ellen Wilson, American Painter in Paris: A Life of Mary Cassatt (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1971), 59–61, 203, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

Luigina Rossi Bortolatto, L’opera completa di Claude Monet, 1870–1889, new series (1972; Milan: Rizzoli, 1978), no. 74, pp. 73–74, 113, 115, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines a Parigi.

Kunio Tsuji, Yoshiaki Inui, and Shuji Takashina, Monet et l’Impressionnisme (Tokyo: Chuokoron-Sha, 1972), 119, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

Joy Newton, “Emile Zola and the French Impressionist Novel,” L’Esprit Créateur 13, no. 4 (Winter 1973): 322, 325, as Boulevard des Capucines.

John Rewald, “The Impressionist Brush,” Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 32, no. 3 (1973–1974): 24, 27–28, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines, Paris.

Donald Hoffmann, “A Beautiful Monet is Acquired by Nelson Gallery,” Star: Sunday Magazine of Kansas City Star 93, no. 126 (January 21, 1973): S10–13, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

“Monet’s Snowy Boulevard,” Kansas City Star 93, no. 129 (January 24, 1973): unpaginated, as Boulevard des Capucines.

“Try this Quick Quiz,” Kansas City Star 93, no. 133 (January 28, 1973): 4B, as Boulevard des Capucines.

Douglas Davis, “Picture Puzzle at the Met,” Newsweek (January 29, 1973): 77, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

“Major Accession,” Gallery Events (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) (February 1973): unpaginated, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines, Paris.

B. Drummond Ayres Jr., “Kansas City Says Its Time Is Here,” Special to New York Times 122, no. 42,062 (March 23, 1973): 78, as Boulevard des Capucines.

Mrs. R.E. Weavering, “A Joy Forever: Nelson Gallery visitors cluster around the new acquisition, Monet’s “Boulevard des Capucines.” The impressionist work will give pleasure to many for many years to come, says one reader,” Kansas City Star (March 26, 1973): (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

“Gifts to Nelson Art Gallery Result in Record Purchases,” Kansas City Star 93, no. 210 (April 15, 1973): 10A, as Boulevard des Capucines.

Donald Hoffmann, “Gifts to the Gallery,” Kansas City Star 93, no. 294 (July 8, 1973): E[1], as Boulevard des Capucines.

“Recent Accessions of American and Canadian Museums: October–December 1972,” Art Quarterly 36, no. 3 (Autumn 1973): 268, 283, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

Elsye W. Allison, “Jeans Party Provides Last Fling for BOTARs: On the Scene,” Kansas City Star (October 29, 1973): 12C, as Boulevard des Capucines, Paris.

Donald Hoffmann, “Gifts Grace Gallery’s 40th Year,” Kansas City Times 106, no. 82 (December 12, 1973): 1, as Boulevard des Capucines.

“Kansas City Woman Gives Nelson Gallery A $1-Million Degas,” Special to New York Times 123, no. 42,326 (December 12, 1973): 62, as Boulevard des Capucines.

Ross E. Taggart and George L. McKenna, eds., Handbook of the Collections in The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Kansas City, Missouri, vol. 1, Art of the Occident, 5th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1973), 150, 258, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines, Paris.

Donald Hoffmann, “Nelson Gallery Construction To Start on the Second Floor,” Kansas City Times 106, no. 265 (July 13, 1974): 3A, as Boulevard des Capucines.

Carl R. Baldwin, The Impressionist Epoch, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1974), 2, 15–16, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines, Paris.

M. A. Bessonova, ed., Zhivopis’ impressionistov. stoletnemu jubileju pervoj vystavki francuzkih hudoznikov-impressionistov (1874–1974), exh. cat. (USSR: Ministry of Culture, 1974), unpaginated.

Anne Dayez, Michel Hoog, and Charles S. Moffett, Impressionism: A Centenary Exhibition, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1974), 46, 59, 159–64, 171, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines, Paris.

Hélène Adhémar, “Centenaire de l’Impressionnisme,” Le petit Journal des grandes Expositions (1974): unpaginated, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

Jean Haley, “Million-Dollar Monet Goes Home,” Kansas City Times 106, no. 312 (September 6, 1974): [1], (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

“Le Centenaire de l’Impressionisme,” Jours de France 51, no. 1031 (September 16–22, 1974): 75, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

Edith Hoffmann, “Impressionists at the Grand Palais,” Burlington Magazine 116, no. 860 (November 1974): 699, as Boulevard des Capucines.

Marcel Wallenstein, “Impressionists Back Home in Paris,” Kansas City Times 107, no. 48 (November 2, 1974): 18C, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

John House, Impressionism: Its Masters, Its Precursors, and Its Influence in Britain, exh. cat. (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 1974), 40.

Daniel Wildenstein, Claude Monet: Biographie et catalogue raisonné, vol. 1, 1840–1881: Peintures (Lausanne: La Bibliothèque des Arts, 1974), no. 293, pp. 65, 240–41, (repro.), as Le Boulevard des Capucines.

“Editorial: The Centenary of Impressionism,” Apollo 101, no. 155 (January 1975): 5–7, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

Elyse W. Allison, “Chinese Exhibition Social Organizer Knows Her Art,” Kansas City Star 95, no. 201 (April 6, 1975): 4C, as Boulevard des Capucines, Paris.

Linda Dalrymple Henderson, “Alfred Sisley’s ‘The Flood on the Road to Saint-Germain’,” Bulletin: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston 6, nos. 2–4 (Summer 1975–Winter 1976): 25–26, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

Joel Isaacson, “Monet in Chicago,” Burlington Magazine 117, no. 867 (June 1975): 429, as Boulevard des Capucines.

Steven Z. Levine, “Monet’s Pairs,” Arts Magazine 49, no. 10 (June 1975): 74, as Boulevard des Capucines.

Der Einzelne und die Masse: Kunstwerke des 19. Und 20. Jahrhunderts, exh. cat. (Recklinghausen, Germany: Städtische Kunsthalle Recklinghausen, 1975), unpaginated, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

Impressionnisme en Lorraine, exh. cat. (Nancy: Musée des Beaux-Arts, 1975), unpaginated, as Boulevard des Capucines.

André Masson, Grace Seiberling, and J. Patrice Marandel, Paintings by Monet, exh. cat. (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 1975), 26–27, 30, 34, 90–91, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

Ralph T. Coe, “Claude Monet’s ‘Boulevard des Capucines’: After a Century,” Bulletin (The Nelson Gallery and Atkins Museum) 5, no. 3 (February 1976): 5–10, 12–15, 16n9, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

Kirk Varnedoe, “Gustave Caillebotte in Context,” Arts Magazine 50, no. 9 (May 1976): 95, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

Denys Sutton, “Book Reviews: Le Dossier Monet,” Apollo 103, no. 172 (June 1976): 530.

Alice Bellony-Rewald, The Lost World of the Impressionists (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1976), 180, 183, 186, 283, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines, Paris.

Maria and Godfrey Blunden, Impressionists and Impressionism, trans. James Emmons (New York: Rizzoli, 1976), 136, 237, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

Sam Hunter, John Jacobus, and Daniel Wheeler, Modern Art: Painting, Sculpture, Architecture, Photography, 3rd rev. ed. (1976; Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2004), 10, 19–20, 93, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines, Paris.

J. Kirk T. Varnedoe and Thomas P. Lee, Gustave Caillebotte: A Retrospective Exhibition, exh. cat. (Houston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1976), 111, 147–48, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

Patricia Pate Havlice, World Painting Index (Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, 1977), 1:809; 2:1320, as Boulevard des Capucines.

Ralph T. Coe, The Kenneth and Helen Spencer Art Reference Library: Given to Complement the Nelson Gallery Collections 1962 (Independence, MO: Graham Graphics, 1978), unpaginated, as Boulevard des Capucines.

Michel Hoog, Monet (London: Eyre Methuen, 1978), unpaginated, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

Joel Isaacson, Claude Monet: Observation and Reflection (Oxford: Phaidon, 1978), 8, 16, 205.

Barbara Ehrlich White, ed., Impressionism in Perspective (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1978), 47, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines, Paris (Les Grands Boulevards).

Robert H. Terte, “The Phenomenal Nelson Gallery,” Antiques World 1, no. 3 (January 1979): 46.

Steven Z. Levine, “The Window Metaphor and Monet’s Windows,” Arts Magazine 54, no. 3 (November 1979): 101, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

Brian Petrie, Claude Monet: The First of the Impressionists (Oxford: Phaidon, 1979), 5, 9–10, 40, 42, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

William C. Seitz, Claude Monet (Cologne: Verlag M. DuMont Schauberg, 1979), 92, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

Kirk Varnedoe, “The Artifice of Candor: Impressionism and Photography Reconsidered,” Art in America 68, no. 1 (January 1980): 71, 73, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

“Director,” Kansas City Star 100, no. 107 (May 4, 1980): 4G, as Boulevard des Capucines.

Erika Billeter, “Malerei und Photographie: Begegnung zweier Medien,” Du: Die Kunstzeitschrift, no. 476 (October 1980): 40, 42, 47, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

Diane Kelder, The Great Book of French Impressionism, 2nd ed. (1980; New York: Artabras, 1997), 7, 109, 122–23, 179, 388, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

Betty Beale, “Party scene still is burning bright,” Kansas City Star 101, no. 189 (April 25, 1981): 3C.

Donald Hoffmann, “The fine art of contributing to the gallery: Benefactors’ gifts help keep inflation at bay at the Nelson,” Kansas City Star 101, no. 225 (June 7, 1981): 1F, as Boulevard des Capucines.

Luigina Rossi Bortolatto, Tout l’œuvre peint de Monet: 1870–1889, ed. Janine Bailly-Herzberg, trans. Simone Darses (Paris: Flammarion, 1981), no. 90, pp. 94–95, (repro.), as Le Boulevard des Capucines.

Jacques Dufwa, Winds from the East: A Study in the Art of Manet, Degas, Monet and Whistler, 1856–86 (Stockholm: Almqvist and Wiksell International, 1981), 148–49, 190, (repro.), as Le Boulevard des Capucines.

Diane Kelder, Die großen Impressionisten (Munich: Hirmer Verlag, 1981), 13, 123, 137, 196, 440, 444, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

Yala H. Korwin, Index to Two-Dimensional Art Works (Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, 1981), 1:552; 2:1028, as Boulevard des Capucines.

Sophie Monneret, L’Impressionnisme et son Époque, vol. 4 (Paris: Éditions Denoël, 1981), 24, as Le Boulevard des Capucines.

Mark Fraser and E.A. Torriero, “Nelson Gallery hopes changes will paint a new portrait,” Kansas City Times (January 30, 1982): A10, as Boulevard Des Capucines.

Patricia Pate Havlice, World Painting Index: First Supplement, 1973–1980 (Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, 1982), 1:445; 2:736, as Boulevard des Capucines.

Paul Hayes Tucker, Monet at Argenteuil (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1982), xii, 163, 172, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines (Le Boulevard des Capucines).

Helen O. Borowitz, “The Rembrandt and Monet of Marcel Proust,” Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 70, no. 2 (February 1983): 90, as Boulevard of Capucines.

George L. McKenna, “My favorite things: What do the curators like?,” Kansas City Star 103, no. 186 (April 24, 1983): 13, as Boulevard des Capucines.

Laura Babcock, “The Nelson Art Gallery: a salute to the past,” Kansas City Star 104, no. 19 (October 9, 1983): 2F, as Boulevard des Capucines.

Patricia Failing, Best-Loved Art from American Museums (New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1983), 58–59, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

Robert Gordon and Andrew Forge, Monet (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1983), 72, 290, (repro.), as Le Boulevard des Capucines (The Boulevard des Capucines).

Ross E. Taggart and Roger B. Ward, City Views, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1983), 7, 14, 33, (repro.), as Paris. Boulevard des Capucines.

Michael Wilson, The Impressionists (Oxford, UK: Phaidon, 1983), 124, 126, 186, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

Paul [Hayes] Tucker, “The first Impressionist exhibition and Monet’s Impression, Sunrise: a tale of times, commerce and patriotism,” Art History 7, no. 4 (December 1984): 475n1, as Boulevard des Capucines.

Andrea P. A. Belloli, ed., A Day in the Country: Impressionism and the French Landscape, exh. cat. (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1984), 355.

T. J. Clark, The Painting of Modern Life: Paris in the Art of Manet and his Followers, rev. ed. (1984; Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999), xi, 70–71, (repro.), as Le Boulevard des Capucines.

Nina Kalitina, Anna Barskaya, and Eugenia Georgievskaya, Claude Monet: Paintings in Soviet Museums, trans. Hugh Aplin and Ruslan Smirnov (Leningrad: Aurora Art, 1984), 127, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

John Rewald and Frances Weitzenhoffer, eds., Aspects of Monet: A Symposium on the Artist’s Life and Times (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1984), 94, 109, 119n10, (repro.), as Le Boulevard des Capucines.

Robert Rosenblum and H. W. Janson, 19th-Century Art: Painting, Sculpture, rev. ed. (1984; Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2005), 350–52, 373, (repro.) as Boulevard des Capucines, Paris.

“Education Insights,” Calendar of Events (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (June 1985): unpaginated, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines, Paris.

Marina Bessonova, Impressionist and Post-Impressionist Paintings in Soviet Museums, trans. Yuri Pamfilov (Leningrad: Aurora Art, 1985), 335.

Horst Keller, Claude Monet (Munich: Verlag F. Bruckmann KG, 1985), 60–61, 72, 166, (repro.), as Der Boulevard des Capucines.

Arlene Doran Kirkpatrick, ed., Masterworks of Impressionism (Winston-Salem, NC: Masterworks Art Publications, 1985), unpaginated, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines, Paris.

John Rewald, Studies in Impressionism, eds. Irene Gordon and Frances Weitzenhoffer (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1985), V, 229, 231, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines, Paris.

The Great Artists, Their Lives, Works and Inspiration, Part 3: Monet (London: Marshall Cavendish, 1985), 78, 80, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

Bruce Bernard, ed., The Impressionist Revolution (London: Orbis, 1986), 27, 268, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

John House, Monet: Nature into Art (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1986), 238n13, as The Boulevard des Capucines.

Eunice Lipton, Looking Into Degas: Uneasy Images of Women and Modern Life (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1986), 94, as Boulevard des Capucines.

Charles S. Moffett, The New Painting: Impressionism 1874–1886, exh. cat. (Geneva: Richard Burton SA, 1986), 23, 108, 114n3, 117n92, 121, 130, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

“The New Painting: Impressionism 1874–1886,” Western Art Digest 13, no. 1 (January–February 1986): 76, 78, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines, Paris.

Donald Hoffmann, “Excitement in the revolution again: ‘New Painting’ is a fresh breath of impressionism,” Kansas City Star 106, no. 133 (February 23, 1986): 1D, 6D, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

Mark M. Johnson, “The New Painting: ‘Impressionism 1874–1886’,” Arts and Activities 99, no. 2 (March 1986): 30, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

Gabriel P. Weisberg, “The Real Impressionist Crisis: ‘The New Painting’ Exhibition,” Arts Magazine 60, no. 7 (March 1986): 72, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

Denys Sutton, “Impressionism and Revisionism,” Apollo 123, no. 292 (June 1986): 404, 413n1, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

“Museums to Sports, KC Has It All,” American Water Works Association Journal 79, no. 4 (April 1987): 133.

Lorenz Eitner, An Outline of 19th Century European Painting: From David Through Cézanne (New York: Harper and Row, 1987), 1:355, 413, as View of the Boulevard des Capucines.

Eberhard Roters and Bernhard Schulz, eds., Ich und die Stadt: Mensch und Großstadt in der deutschen Kunst des 20. Jahrhunderts, exh. cat. (Berlin: Nicolaische Verlagsbuchhandlung Beuermann GmbH, 1987), 42–43, 43n7, as Le Boulevard des Capucines.

Kirk Varnadoe, Gustave Caillebotte, exh. cat. (1987; repr. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 88, 114, 140, 156, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

Roger Ward, ed., A Bountiful Decade: Selected Acquisitions, 1977–1987, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1987), 13, as Boulevard des Capucines.

Bradley Collins, Jr., “Reviews Work(s): Looking into Degas: Uneasy Images of Women and Modern Life by Eunice Lipton,” Woman’s Art Journal 9, no. 1 (Spring–Summer 1988): 39.

Ellen R. Goheen, The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1988), 14, 16, 100–01, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines, Paris.

S. Hollis Clayson, “The Family and the Father: ‘The Grande Jatte’ and Its Absences,” Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 14, no. 2 (1989): 242n14, as Boulevard des Capucines.

“Nelson Gallery, institute form solid base for art landscape,” Kansas City Star 109, no. 135 (February 22, 1989): 26, as Boulevard des Capucines.

R. R. Bernier, “Monet’s ‘Language of the Sketch’,” Art History 12, no. 3 (September 1989): 319n4, as Boulevard des Capucines.

Marc S. Gerstein, Impressionism: Selections from Five American Museums, exh. cat. (New York: Hudson Hills, 1989), 12, 20, 120–22, 140, 144, 148, 158, 164, 168, 178, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

Toni Wood, “The impressionists broke all the rules: Modern viewers love impressionism,” Kansas City Star 110, no. 184 (April 15, 1990): H-4, as Boulevard des Capucines.

Scott Cantrell, “Keepers of the Light: Working from individual blueprints, impressionists laid colorful bricks in the foundation of modern art,” Kansas City Star 110, no. 191 (April 22, 1990): I-4, as Boulevard des Capucines.

Toni Wood, “Expatriate paintings in Midwest: Works took diverse routes to exhibit,” Kansas City Star 110, no. 233 (June 3, 1990): G-5, as Boulevard des Capucines.

Colta Ives, Helen Giambruni, and Sasha M. Newman, Pierre Bonnard: The Graphic Art, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1989), 124, 127, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

Kenneth McConkey, British Impressionism (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1989), 41, 160, as Boulevard des Capucines.

Joel Isaacson, “Reviewed Work(s): Impressionism: Art, Leisure, and Parisian Society by Robert L. Herbert,” Art Journal 49, no. 1 (Spring 1990): 63.

Henry Adams, “Winslow Homer’s ‘Impressionism’ and Its Relation to His Trip to France,” Studies in the History of Art 26 (1990): 84n1, as Boulevard des Capucines.

Janet Braide and Nancy Parke-Taylor, Caroline and Frank Armington: Canadian Painter-Etchers in Paris ([Brampton, Canada]: Art Gallery of Peel, 1990), 44, 78n99, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

Clive Gregory and Sue Lyon, eds., Great Artists of the Western World, vol. 7, Impressionism: Edouard Manet, Edgar Degas, Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir (London: Marshall Cavendish, 1990), 90, 142–43, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

Horst Keller, Claude Monet: Der Impressionist (Serie Piper), vol. 1188 (Munich: R. Piper GmbH, 1990), 9, 56, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

Katsumi Miyazaki, The Great History of Art (Kyoto, Japan: Dōhōsha Shuppan, 1990), 67, 142, 144, (repro.).

Karin Sagner-Düchting, Claude Monet, 1840–1926: Ein Fest für die Augen (Cologne: Benedikt Taschen Verlag GmbH, 1990), 56–57, 60–61, 74, 97, (repro.), as Der Boulevard des Capucines, Le Boulevard des Capucines, and Le Boulevard des Capucines.

Lester M. Sdorow, Psychology, 3rd ed. (1990; Madison, WI: Brown and Benchmark, 1995), 606, C-3, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

Roger Ward, “Selected Acquisitions of European and American Paintings at The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, 1986–1990,” Burlington Magazine 133, no. 1055 (February 1991): 150, as Boulevard des Capucines.

Matthew Bessell, Caumsett: The Home of Marshall Field III in Lloyd Harbor, New York (Huntington, NY: Huntington Town Board, 1991), 25, 51n48, as Boulevard.

Michael Howard, ed., The Impressionists by Themselves: A selection of their paintings, drawings, and sketches with extracts from their writings (London: Conran Octopus, 1991), 72, 317, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

Martha Kapos, ed., The Impressionists: A Retrospective (New York: Hugh Lauter Levin Associates, 1991), 83, 86–87, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.

Sylvie Patin, Monet: “un œil… mais, bon dieu, quel œil!” (Paris: Gallimard, 1991), 56–57, 65, 170, (repro.), as Le Boulevard des Capucines.

Charles F. Stuckey, French Painting (New York: Hugh Lauter Levin Associates, 1991), 150–51, 316, 319, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines, Paris.

Daniel Wheeler, Art since Mid-Century: 1945 to the Present (New York: Vendome, 1991), 12–13, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines, Paris.

Daniel Wildenstein, Claude Monet: Catalogue raisonné, vol. 5, Supplément aux peintures, dessins, pastels, index (Lausanne: Wildenstein Institute, 1991), no. 293, pp. 293, 303, 308, 315, 317, 328, 331, 333, 335, 337, 340.

Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, The Impressionist and the City: Pissarro’s Series Paintings, exh. cat. (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 1992), xv–xvi, (repro.), as Boulevard des Capucines.