![]()

Berthe Morisot, Under the Orange Tree, 1889

| Artist | Berthe Morisot, French, 1841–1895 |

| Title | Under the Orange Tree |

| Object Date | 1889 |

| Alternate and Variant Titles | Sous l’oranger |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (Unframed) | 21 1/2 x 25 7/8 in. (54.6 x 65.7 cm) |

| Signature | Signed lower right: Berthe Morisot |

| Credit Line | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Gift of Henry W. and Marion H. Bloch, 2015.13.15 |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Berthe Morisot, Under the Orange Tree, 1889,” catalogue entry in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.636.5407.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Berthe Morisot, Under the Orange Tree, 1889,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/10.37764/78973.5.636.5407.

Berthe Morisot’s paintings of women and children outdoors in the 1880s and early 1890s are central to her body of work and are often considered some of the most radical examples of portraiture in the second half of the nineteenth century. Like her fellow Impressionist Mary Cassatt (American, 1844–1926), Morisot was born into a society that often minimized the contributions of women to the professional art world. Moreover, their choice in subject matter—women and children in their daily activities—was considered a minor, particularly feminine genre.1The private sphere of the female is discussed in the literature of Griselda Pollock and Linda Nochlin. See Linda Nochlin, “Morisot’s Wet Nurse: The Construction of Work and Leisure in Impressionist Painting,” in Perspectives on Morisot (New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1990), 231–43; and Griselda Pollock, “Modernity and the Spaces of Femininity,” in Vision and Difference: Femininity, Feminism, and Histories of Art (London: Routledge, 1988), 50–90. For recent scholarship on Morisot’s “modern femininity,” see Sylvie Patry, “Berthe Morisot: Simulating Ambiguities,” in Cindy Kang et al., Berthe Morisot: Woman Impressionist, exh. cat. (New York: Rizzoli Electa, 2018), 15–51. Indeed, as critic Théodore Duret wrote, Morisot “constantly found that her status as a woman overshadowed her artistry. . . . She knew she was the equal of any painter and quietly suffered from being treated as an amateur.”2“Elle voyait constamment sa position de femme du monde voiler sa qualite d’artiste. . . . elle se savait l’egale de n’importe quel autre et souffrait secretement d’etre traitee en amateur.” Théodore Duret, Histoire des peintres impressionnistes: Pissarro, Claude Monet, Sisley, Renoir, Berthe Morisot, Guillaumin (Paris: Floury, 1906), 165. Morisot herself wrote, “I do not think any man would ever treat a woman as his equal, and it is all I ask because I know my own worth.”3Notebook of Berthe Morisot, 1890, Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris, p. 34. Cited and translated in Alain Clairet, Delphine Montalant, and Yves Rouart, Berthe Morisot, 1841–1895: Catalogue raisonné de l’œuvre peint (Paris: CÉRA-nrs éditions, 1997), 50.

Beginning in the 1880s, Morisot began to spend more time in the French countryside with her husband, Eugène Manet (the brother of artist Edouard Manet, 1832–1883), and their daughter, Julie. This change in environment led to her bourgeoning interest in depicting figures in nature. Increasingly, she presented women and children in the outdoors rather than in domestic interiors.4While images of women and children outdoors appeared in her oeuvre as early as the 1860s, these figures, placed on balconies or verandas, often expressed the limitations of women in the public sphere. See, for example, On the Balcony, 1871/1872, Art Institute of Chicago. For more on the limitations of women in the public sphere, see Pollock, “Modernity and the Spaces of Femininity.” For Morisot, the outdoor setting provided a reprieve from the artistic prejudices placed upon her sex; she used it to appropriate and ultimately update images of women and children, synthesizing the traditional motifs and bold techniques of her Impressionist colleagues Claude Monet (1840–1926), Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919), and Edgar Degas (1834–1917).5Morisot exhibited alongside her colleagues at seven of the eight Impressionist exhibitions from 1874 to 1886. For more information on her entries in these exhibitions, see Anne Higonnet, Berthe Morisot: A Biography (New York: Harper & Row, 1990). Despite the perceived “feminine” limitations of her artistic practice, she became renowned by her contemporaries for the masterful way she rendered her subjects in paint on canvas.6Morisot’s critical reception during her lifetime has been the subject of much scholarship. For more information on the implications surrounding her reception, see Hugues Wilhelm, “La Fortune critique de Berthe Morisot: Des Impressionistes a l’exposition posthume,” in Sylvie Patry et al., Berthe Morisot, 1841–1895, exh. cat. (Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 2002), 63–87; and Jean-Dominque Rey, “Writers in Morisot’s Circle,” in Jean-Dominique Rey and Sylvie Patry, Berthe Morisot (Paris: Flammarion, 2010), 175–91. Despite the limitations imposed on Morisot as a female artist, her male contemporaries greatly admired her. Her work was collected by Manet, Degas, Monet, and Camille Pissarro, and by several noted Impressionist collectors, including Georges de Bellio, Paul Gallimard, and Auguste Pellerin. For more on this subject, see Hugues Wilhelm, “Berthe Morisot in the Collections of her Impressionist Friends,” in Berthe Morisot: Regards Pluriels, Plural Vision, exh. cat. (Milan: Mazzotta, 2006), 69–117. “No one represents Impressionism with more refined talent or with more authority than Berthe Morisot,” wrote French critic Gustave Geffroy in his review of the Impressionist exhibition of 1881.7Gustave Geffroy, “L’Exposition des artistes indépendants,” La Justice (April 19, 1881). Cited and translated in Ruth Berson, The New Painting: Impressionism, 1874–1886: Documentation, Exhibited Works, new ed. (San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1996), 1:343. Works such as Under the Orange Tree, painted in 1889, highlight perfectly her ability to integrate the “feminine” into modern art.

Under the Orange Tree depicts the artist’s favorite subject, her

daughter, Julie Manet (1878–1966), posed in the garden of their country

villa in Cimiez.8Julie’s likeness appears in a large number of Morisot’s paintings. For more information on her artistic production at this time, see Higonnet, Berthe Morisot, 159–60, 189–91. “We are a little in the mountains, on the site of

the Old Roman city . . . it is very Italian, very rural, and in my

opinion delightful,” Morisot wrote to her sister, Edma, upon their

arrival in Cimiez in the fall of 1888. “We have a large garden, more

precisely an orchard, with many orange trees; their fruit will be yellow

next month.”9Denis Rouart, ed., The Correspondence of Berthe Morisot with Her Family and Her Friends, trans. Betty W. Hubbard (New York: E. Weyhem, 1957), 143. Perhaps prompted by Frédéric Bazille’s (1841–1870)

“figures en plein air,” women and children outdoors became a prominent

part of Morisot’s artistic oeuvre in the late 1880s and early

1890s.10Morisot was also made aware of plein-air painting through her early lessons with French landscape artist Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796–1875). Indeed, Morisot’s Under the Orange Tree brings to mind

Bazille’s View of the Village (Fig. 1), a work she had openly admired

almost a decade before. She described it in a letter to Edma dated May

5, 1896: “The tall Bazille has painted something that I find very good.

It is a little girl in a light dress seated in the shade of the tree,

with a glimpse of the village in the background. There is much light and

sun in it. He has tried to do what we have so often attempted—a figure

in the outdoor light—and this time he seems to have been

successful.”11Rouart, The Correspondence of Berthe Morisot, 32. Bazille’s sitter is dressed in a simple white dress,

sitting upright in the foreground, her hands placed delicately in her

lap, surrounded by rich vegetation.

While Morisot’s sitter is reminiscent of Bazille’s young woman, Morisot’s way of capturing the spirit of her young model sets the artist apart from her male colleague. Morisot’s frenzied background and Julie’s casual pose were daring departures from the more formal mode of plein-airen plein air (adjective: plein-air): French for “outdoors.” The term is used to describe the act of painting quickly outside rather than in a studio. portraiture demonstrated by Bazille, illustrating the aesthetic for which she is best known. Morisot’s increasingly sketchy handling reflects her interest in deconstructing an otherwise traditional subject and promotes her interest in dissolving the distinction between the sitter and her natural surroundings. Indeed, her focus on brushwork in paintings such as this seemed to renew the subject, especially when seen in comparison with Bazille’s more traditional View of the Village. Art critic Georges Rivière noted Morisot’s tendency to deconstruct her subject in his 1877 review of the third Impressionist exhibition: “Her watercolors, her pastels, her paintings all show . . . a light touch and unpretentious allure. . . . Mademoiselle Berthe Morisot succeeds in capturing fleeting notes on her canvases with a delicacy, spirit, and skill that ensure her a prominent place at the center of the Impressionist Group.”12Georges Rivière, “Les Intransigeants et les impressionnistes: Souvenirs du salon de 1877,” L’Artiste 2, no. 49 (November 1, 1877): 300. Cited and translated in Jean-Dominique Rey, Berthe Morisot, 71.

While Morisot’s and Bazille’s canvases share the similar subject of a young girl posed in an outdoor setting, their approaches are completely different. Morisot did not concern herself with the competing view of the countryside, but rather with the intimate, particularly feminine space of the garden. She placed Julie amid tall grasses in an overgrown corner of their private enclosure. Morisot’s use of her daughter and family acquaintances in her paintings at this time also denotes the level of intimacy with which she approached this new avenue of her production; works including Under the Orange Tree are among her most endearing. As Paul Girard noted in 1896, she gave “particularly to children and young women, a grace to which she alone knows the secret.”13Paul Girard, “Chronique du jour,” Le Charivari 65 (March 13, 1896): unpaginated. Cited and translated in Kang et al., Berthe Morisot, 97.

Captivated by the Cimiez villa’s orchard, Morisot began to introduce

fruit-bearing trees into her outdoor paintings. “I am doing aloes,

orange trees, olive trees; in short, a whole exotic vegetation that is

quite difficult to draw,” she wrote to her sister in 1889.14Rouart, The Correspondence of Berthe Morisot, 146. “I

should like to capture some of the charming effect of the surrounding

vegetation. I am working myself to death trying to give the effect of

the orange trees. I want it to be as delicate as it is in the Botticelli

I saw in Florence.” She completed a series of women picking oranges in

1889, including Picking Oranges (Fig. 2). As in the

Nelson-Atkins Under the Orange Tree, Morisot placed her figure in the

midst of yellow-green trees with shining, golden-orange fruit.

Fruit picking, a motif favored by many of her contemporaries, was also the subject of her Cherry Tree series, painted in 1891, although she never endowed the activity with overtly symbolic meaning, as had Mary Cassatt and Camille Pissarro.15For example: Mary Cassatt, Young Woman Picking the Fruits of Knowledge, the central panel of a mural for the Woman’s Building in Chicago in 1893 (current location unknown); and Camille Pissarro, Apple Picking, 1881–1886 (Ohara Museum of Art, Japan). As noted, the subject of women picking fruit would be taken up again by the artist in 1891 when she completed a series of images of women at cherry trees. For more information on this series, see Patry et. al., Berthe Morisot, 1841–1895, 384–88. The trope of women and fruit is a longstanding one in the history of art, as, for example, in Sandro Botticelli’s La Primavera (1482; Uffizi Gallery, Florence), a work Morisot greatly admired during her stay in Florence in 1881 and later wrote about to her sister in 1889.16Rouart, The Correspondence of Berthe Morisot, 146. Yet, while her images of women and fruit bear a certain likeness to this defining Renaissance painting, Morisot does little to construct an allegorical relationship between figure and nature. Her work is far more concerned with her own modern sensibilities, her brushwork, and the relationship between the sitter and her environment.

Praised for her delicate handling, Morisot is often associated with

eighteenth-century French Rococo artists and styles.17For a recent assessment of Morisot’s Rococo revival, see Nicole R. Myers, “Extreme Novelty or Things of the Past: Morisot and the Modern Woman,” in Kang et al., Berthe Morisot, 77–113. Commenting on

the Fifth Impressionist Exhibition in 1880, contemporary critic Philippe

Burty wrote: “Morisot handles her brush and palette with a truly

astonishing delicacy. Not since the eighteenth century, not since

Fragonard, have we seen comparable intellectual audacity and clarity of

tone.”18Phillippe Burty, “Exposition des ɶuvres des artistes indépendants,” La République française (April 10, 1880): 2, cited and translated in Berson, The New Painting: Impressionism, 1:269. Morisot claimed to be the great-grandniece of the artist

Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732–1806), and perhaps partly for that reason

she had a great appreciation for eighteenth-century French artists,

including François Boucher (1703–1770), whose works she copied on more

than one occasion.19For example, Morisot, Apollo Revealing His Divinity before the Shepherdess Iseé, 1892 (private collection, France) and Morisot, Venus at the Forge of Vulcan, 1884 (private collection, France). Clairet, Montalant, and Rouart, Berthe Morisot, no. 145, p. 185; no. 324, p. 272. Morisot’s Under the Orange Tree is reminiscent

of the frivolity of Fragonard’s fêtes galantesfêtes galantes: French for “gallant parties.” Paintings that feature elite groups of upper-class men and women shown in conversation, role playing, dancing, or flirting outdoors. and recalls the

vivacious color of Boucher’s Jupiter in the Guise of Diana and the

Nymph Calisto (Fig. 3), among other works. Around the time that Morisot

demonstrated this kinship with eighteenth-century art, she was also in

frequent contact with Renoir,

who visited her on several occasions at Cimiez and shared her love of

the French Rococo. Under the Orange Tree bears some similarity to

works such as Renoir’s Girls Picking Flowers in a Meadow (Fig. 4),

composed of the same soft, iridescent colors that Morisot admired in the

work of eighteenth-century French masters. Nonetheless, Morisot’s

unique, sketch-like style added something entirely new to their shared

source of inspiration.

Fig. 3. François Boucher, Jupiter in the Guise of Diana and the Nymph Calisto, 1759, oil on canvas, 22 3/4 x 27 1/2 in. (57.79 x 69.85 cm), The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 32-29

Fig. 3. François Boucher, Jupiter in the Guise of Diana and the Nymph Calisto, 1759, oil on canvas, 22 3/4 x 27 1/2 in. (57.79 x 69.85 cm), The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 32-29

Fig. 4. Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Girls Picking Flowers in a Meadow, 1890, oil on canvas, 25 5/8 x 31 7/8 in. (65.1 x 81 cm), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Juliana Cheney Edwards Collection, 39.675

Fig. 4. Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Girls Picking Flowers in a Meadow, 1890, oil on canvas, 25 5/8 x 31 7/8 in. (65.1 x 81 cm), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Juliana Cheney Edwards Collection, 39.675

Under the Orange Tree was completed during the final years of Morisot’s life, when she was working primarily with pastel and watercolor. The influence of this media is evident in the wet-over-wet and wet-over-dry paint application, which mimics the effect of pastels and suggests the fleeting movement of the figure. Morisot brought particular care to the lush foliage of the garden in the background. The blended palette, dominated by greens, yellows, and pinks applied in varying widths and strokes, is often scratched and scraped along the surface of the canvas, strengthening its impression of fluidity.

This is one of the many paintings that Morisot left to her daughter following her death in 1895. Julie was quite fond of the painting, recalling it in a 1963 interview with Life magazine: “We were always together, Mother and I. She painted me at home during the day . . . she took along notebooks to sketch me. . . . At times we took house in the county. . . . I used to sit under the orange trees.”20“The Great Ones All Painted Us: Renoir, Degas, Manet and Mother; A French Lady’s Engaging Recollections,” Life 54, no. 19 (May 10, 1963): 53. The picture would remain in Julie’s collection until at least 1936, after which it went to her grandson Yves Rouart (b. 1940). By the time the painting entered the collection of Henry and Marion Bloch in 1990, a renewed interest in the artist, particularly informed by feminist scholarship in the 1980s and 1990s, provided a timely reevaluation of her artistic accomplishments.21For more information on 1980s and 1990s feminist scholarship on Morisot, see Pollock, “Modernity and the Spaces of Femininity,” 50–90; and Nochlin, “Morisot’s Wet Nurse,” 231–43. Indeed, tracing the path of this work and others into renowned Impressionist collections in the latter half of the twentieth century helps to confirm Morisot’s artistic equality with her male colleagues, removing her from the ranks of the “amateur artist” to which she has so often been consigned.

Notes

-

The private sphere of the female is discussed in the literature of Griselda Pollock and Linda Nochlin. See Linda Nochlin, “Morisot’s Wet Nurse: The Construction of Work and Leisure in Impressionist Painting,” in Perspectives on Morisot (New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1990), 231–43; and Griselda Pollock, “Modernity and the Spaces of Femininity,” in Vision and Difference: Femininity, Feminism, and Histories of Art (London: Routledge, 1988), 50–90. For recent scholarship on Morisot’s “modern femininity,” see Sylvie Patry, “Berthe Morisot: Simulating Ambiguities,” in Cindy Kang et al., Berthe Morisot: Woman Impressionist, exh. cat. (New York: Rizzoli Electa, 2018), 15–51.

-

“Elle voyait constamment sa position de femme du monde voiler sa qualite d’artiste. . . . elle se savait l’egale de n’importe quel autre et souffrait secretement d’etre traitee en amateur.” Théodore Duret, Histoire des peintres impressionnistes: Pissarro, Claude Monet, Sisley, Renoir, Berthe Morisot, Guillaumin (Paris: Floury, 1906), 165.

-

Notebook of Berthe Morisot, 1890, Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris, p. 34.

Cited and translated in Alain Clairet, Delphine Montalant, and Yves Rouart, Berthe Morisot, 1841–1895: Catalogue raisonné de l’œuvre peint (Paris: CÉRA-nrs éditions, 1997), 50. -

While images of women and children outdoors appeared in her oeuvre as early as the 1860s, these figures, placed on balconies or verandas, often expressed the limitations of women in the public sphere. See, for example, On the Balcony, 1871/1872, Art Institute of Chicago. For more on the limitations of women in the public sphere, see Pollock, “Modernity and the Spaces of Femininity.”

-

Morisot exhibited alongside her colleagues at seven of the eight Impressionist exhibitions from 1874 to 1886. For more information on her entries in these exhibitions, see Anne Higonnet, Berthe Morisot: A Biography (New York: Harper & Row, 1990).

-

Morisot’s critical reception during her lifetime has been the subject of much scholarship. For more information on the implications surrounding her reception, see Hugues Wilhelm, “La Fortune critique de Berthe Morisot: Des Impressionistes a l’exposition posthume,” in Sylvie Patry et al., Berthe Morisot, 1841–1895, exh. cat. (Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 2002), 63–87; and Jean-Dominque Rey, “Writers in Morisot’s Circle,” in Jean-Dominique Rey and Sylvie Patry, Berthe Morisot (Paris: Flammarion, 2010), 175–91. Despite the limitations imposed on Morisot as a female artist, her male contemporaries greatly admired her. Her work was collected by Manet, Degas, Monet, and Camille Pissarro, and by several noted Impressionist collectors, including Georges de Bellio, Paul Gallimard, and Auguste Pellerin. For more on this subject, see Hugues Wilhelm, “Berthe Morisot in the Collections of her Impressionist Friends,” in Berthe Morisot: Regards Pluriels, Plural Vision, exh. cat. (Milan: Mazzotta, 2006), 69–117.

-

Gustave Geffroy, “L’Exposition des artistes indépendants,” La Justice (April 19, 1881). Cited and translated in Ruth Berson, The New Painting: Impressionism, 1874–1886: Documentation, Exhibited Works, new ed. (San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1996), 1:343.

-

Julie’s likeness appears in a large number of Morisot’s paintings. For more information on her artistic production at this time, see Higonnet, Berthe Morisot, 159–60, 189–91.

-

Denis Rouart, ed., The Correspondence of Berthe Morisot with Her Family and Her Friends, trans. Betty W. Hubbard (New York: E. Weyhem, 1957), 143.

-

Morisot was also made aware of plein-air painting through her early lessons with French landscape artist Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796–1875).

-

Rouart, The Correspondence of Berthe Morisot, 32.

-

Georges Rivière, “Les Intransigeants et les impressionnistes: Souvenirs du salon de 1877,” L’Artiste 2, no. 49 (November 1, 1877): 300. Cited and translated in Jean-Dominique Rey, Berthe Morisot, 71.

-

Paul Girard, “Chronique du jour,” Le Charivari 65 (March 13, 1896): unpaginated. Cited and translated in Kang et al., Berthe Morisot, 97.

-

Rouart, The Correspondence of Berthe Morisot, 146.

-

For example: Mary Cassatt, Young Woman Picking the Fruits of Knowledge, the central panel of a mural for the Woman’s Building in Chicago in 1893 (current location unknown); and Camille Pissarro, Apple Picking, 1881–1886 (Ohara Museum of Art, Japan). As noted, the subject of women picking fruit would be taken up again by the artist in 1891 when she completed a series of images of women at cherry trees. For more information on this series, see Patry et. al., Berthe Morisot, 1841–1895, 384–88.

-

Rouart, The Correspondence of Berthe Morisot, 146.

-

For a recent assessment of Morisot’s Rococo revival, see Nicole R. Myers, “Extreme Novelty or Things of the Past: Morisot and the Modern Woman,” in Kang et al., Berthe Morisot, 77–113.

-

Phillippe Burty, “Exposition des ɶuvres des artistes indépendants,” La République française (April 10, 1880): 2, cited and translated in Berson, The New Painting: Impressionism, 1:269.

-

For example, Morisot, Apollo Revealing His Divinity before the Shepherdess Iseé, 1892 (private collection, France) and Morisot, Venus at the Forge of Vulcan, 1884 (private collection, France). Clairet, Montalant, and Rouart, Berthe Morisot, no. 145, p. 185; no. 324, p. 272.

-

“The Great Ones All Painted Us: Renoir, Degas, Manet and Mother; A French Lady’s Engaging Recollections,” Life 54, no. 19 (May 10, 1963): 53.

-

For more information on 1980s and 1990s feminist scholarship on Morisot, see Pollock, “Modernity and the Spaces of Femininity,” 50–90; and Nochlin, “Morisot’s Wet Nurse,” 231–43.

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Mary Schafer, “Berthe Morisot, Under the Orange Tree, 1889,” technical entry in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/10.37764/78973.5.636.2088.

MLA:

Schafer, Mary. “Berthe Morisot, Under the Orange Tree, 1889,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.636.2088.

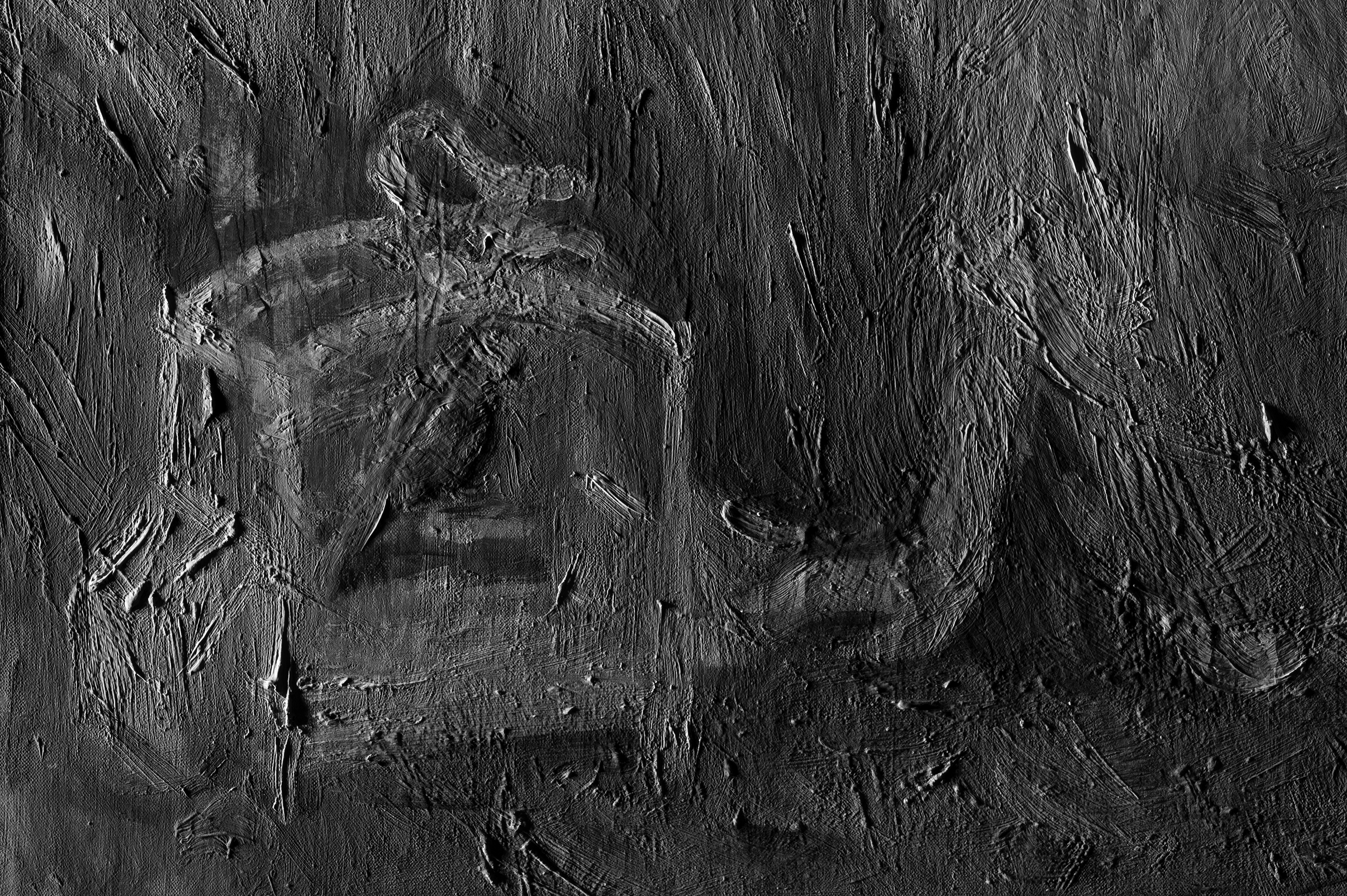

Berthe Morisot (1841–1895) executed Under the Orange Tree with lively

brushwork and a palette of green, yellow, pink, and peach tones. The

off-white, commercially-applied ground layerground layer: An opaque preparatory layer applied to the support, either commercially or by the artist, to prevent absorption of the paint into the canvas or panel. See also priming layer. remains visible in thinly

painted passages, particularly in the upper left quadrant. No underdrawingunderdrawing: A drawn or painted sketch beneath the paint layer. The underdrawing can be made from dry materials, such as graphite or charcoal, or wet materials, such as ink or paint. was detected with infrared reflectographyinfrared reflectography (IRR): A form of infrared imaging that exploits the behavior of painting materials at wavelengths beyond those accessible to infrared photography. These advantages sometimes include a continuing increase in the transparency of pigments beyond wavelengths accessible to infrared photography (i.e, beyond 1,000 nanometers), rendering underdrawing more clearly. The resulting image is called an infrared reflectogram. Devices that came into common use in the 1980s such as the infrared vidicon effectively revealed these features but suffered from lack of sharpness and uneven response. Vidicons continue to be used out to 2,200 nanometers but several newer pixelated detectors including indium gallium arsenide and indium antimonide array detectors offer improvements. All of these devices are optimally used with filters constraining their response to those parts of the infrared spectrum that reveal the most within the constraints of the palette used for a given painting. They can be used for transmitted light imaging as well as in reflection. or microscopic

examination.1The painting was examined using a Hamamatsu vidicon camera. With the exception of a few strokes of violet paint

that loosely outline the left tree, no other preparatory layers are

apparent.

Fig. 5. Photomicrograph of zigzagging brushwork, Under the Orange Tree (1889)

Fig. 5. Photomicrograph of zigzagging brushwork, Under the Orange Tree (1889)

Fig. 6. Photomicrograph of thin, streaky paint applications, Under the Orange Tree (1889)

Fig. 6. Photomicrograph of thin, streaky paint applications, Under the Orange Tree (1889)

Fig. 7. Detail of fine paint strokes suggesting a tree, Under the Orange Tree (1889)

Fig. 7. Detail of fine paint strokes suggesting a tree, Under the Orange Tree (1889)

Fig. 8. Ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescence photograph of Under the Orange Tree (1889)

Fig. 8. Ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescence photograph of Under the Orange Tree (1889)

Fig. 9. Raking light detail of Under the Orange Tree (1889) showing incised lines on the figure

Fig. 9. Raking light detail of Under the Orange Tree (1889) showing incised lines on the figure

Fig. 10. Raking light detail of Under the Orange Tree (1889) showing scraped and incised paint on the birdcage

Fig. 10. Raking light detail of Under the Orange Tree (1889) showing scraped and incised paint on the birdcage

The lightweight, plain weaveplain weave: A basic textile weave in which one weft thread alternates over and under the warp threads. Often this structure consists of one thread in each direction, but threads can be doubled (basket weave) or tripled to create more complex plain weave. Plain weave is sometimes called tabby weave. canvas is unlinedlining: A procedure used to reinforce a weakened canvas that involves adhering a second fabric support using adhesive, most often a glue-paste mixture, wax, or synthetic adhesive. with preserved tacking marginstacking margins: The outer edges of canvas that wrap around and are attached to the stretcher or strainer with tacks or staples. See also tacking edge.. The canvas is supported by a five-member stretcherstretcher: A wooden structure to which the painting’s canvas is attached. Unlike strainers, stretchers can be expanded slightly at the joints to improve canvas tension and avoid sagging due to humidity changes or aging. with one

vertical crossbar, and the painting dimensions do not correspond to a standard-formatstandard-format supports: Commercially prepared supports available through art suppliers, which gained popularity in the nineteenth century during the industrialization of art materials. Available in three formats figure (portrait), paysage (landscape), and marine (marine), these were numbered 1 through 120 to indicate their size. For each numbered size, marine and paysage had two options available: a larger format (haute) and smaller (basse) format. size. The painted composition continues onto the top,

left, and right tacking margins, indicating that Morisot was initially

working on a larger canvas of unknown size (Fig. 11). A faint line of red

paint marks the current top edge. Whereas Morisot cropped the three

sides, she expanded the bottom edge of the painting approximately two

centimeters, and in doing so, shifted the bottom tacking margin to the picture planepicture plane: The two-dimensional surface where the artist applies paint.. A diagonal canvas crease on the lower left corner (now

covered by retouchingretouching: Paint application by a conservator or restorer to cover losses and unify the original composition. Retouching is an aspect of conservation treatment that is aesthetic in nature and that differs from more limited procedures undertaken solely to stabilize original material. Sometimes referred to as inpainting or retouch.), vacant tack holes on the picture plane (Fig. 12),

and exposed ground on the left tacking margin (Fig. 11) correspond to

this former tacking edgetacking edge: The outer edges of canvas that wrap around and are attached to the stretcher or strainer with tacks or staples. See also tacking margin.. Morisot then covered the ground layer along

the bottom edge with a thin, bright green paint, laying in the color

with loose up and down strokes.

Fig. 11. Detail of the left tacking margin of Under the Orange Tree (1889)

Fig. 11. Detail of the left tacking margin of Under the Orange Tree (1889)

Fig. 12. Photomicrograph of a tack hole on the bottom edge of the picture plane, Under the Orange Tree (1889)

Fig. 12. Photomicrograph of a tack hole on the bottom edge of the picture plane, Under the Orange Tree (1889)

Morisot’s subsequent additions of paint were concentrated at the lower

center of the painting, leaving a light-colored, horizontal band visible

on the right and left edges as well as noticeable tack holes across the

bottom (Figs. 9, 13). Notably, Villa with Orange Trees, Nice (1882;

private collection) also appears to have evenly spaced, exposed tack

holes along the bottom edge of the picture plane.2See photograph of Villa with Orange Trees, Nice (1882; private collection) in Jean-Dominique Rey, Berthe Morisot (Paris: Flammarion, S.A., 2010), 151. Although tack

holes and pinholes are present at the outermost edges of other Morisot

paintings (Fig. 14), unlike the Nelson-Atkins painting, it is less clear

whether these features relate directly to the artist’s process (i.e.

format changes, re-stretching, or perhaps pinning of the canvas to a

rigid support prior to painting) or result from a later intervention by

a framer or restorer.3There are several tack holes and pinholes on the outermost edges of Woman and Child in the Garden at Bougival (1882; Amgueddfa Cymru - National Museum Wales). An earlier abandoned composition is present on the canvas reverse, but it is unclear if these holes relate to pinning of the canvas onto a rigid support for painting, artist re-stretching, or perhaps poor framing that occurred at a later date. Adam Webster, chief conservator, Amgueddfa Cymru - National Museum Wales, Cardiff, email message with the author, December 17, 2019. The Pink Dress (ca. 1870) and Young Woman Seated on a Sofa (ca. 1879), both in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, were also reformatted, although it is unclear whether these were changes made by the artist. Tack holes near the fold-over edges of Young Woman Seated on a Sofa indicate that the painting was once stretched in a slightly smaller format. Charlotte Hale, painting conservator, Metropolitan Museum of Art, email message with the author, September 25, 2020. Hale also observed that The Pink Dress, an unlined painting on its original stretcher, was reduced in size by cutting the width of the left and right stretcher members by half. Morisot may have made this format change herself, as the painting was extensively reworked, but it is also feasible that the smaller format was undertaken at a later date, to fit a smaller frame for example. See Colin B. Bailey, The Annenberg Collection: Masterpieces of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009), 101n11.

Fig. 13. Detail of the bottom left edge of Under the Orange Tree (1889)

Fig. 13. Detail of the bottom left edge of Under the Orange Tree (1889)

Fig. 14. Detail of tack holes on the upper right of Woman and Child in the Garden at Bougival (1882). Courtesy of the conservation department, Amgueddfa Cymru - National Museum Wales.

Fig. 14. Detail of tack holes on the upper right of Woman and Child in the Garden at Bougival (1882). Courtesy of the conservation department, Amgueddfa Cymru - National Museum Wales.

Prior to the 2018 treatment of Under the Orange Tree, retouching and fill materialfill material: A material added to a loss of paint and/or ground to create an area level with the surrounding original paint. covered the exposed ground on the left side of the bottom edge as well as the tack holes.4Mary Schafer, March 24, 2018, examination report, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, no. 2015.13.15. These additions were likely an attempt to resolve what was considered an unfinished edge, a common practice applied to Impressionist works that were viewed as incomplete.5Iris Schaefer, Caroline von Saint-George, and Katja Lewerentz, Painting Light: The Hidden Techniques of the Impressionists (Milan: Skira Editore, 2008), 166. Critics disapproved of the unpainted edges on Summer’s Day (about 1879; National Gallery of Art, London), shown at the 1880 Impressionist exhibition: “Why with her talent, does she not take the trouble to finish?”6David Bomford, Jo Kirby, John Leighton, and Ashok Roy, Art in the Making: Impressionism (London: Yale University Press, 1991), 181. In 1882 another critic described Morisot’s technique and lack of finish with a colorful analogy: “Mlle. Morisot is always the same: rapid sketches, delicate, even charming in tone, but alas!—there is no solidity, no full-bodied complete work. She always serves fluffy beaten egg whites on vanilla cream at her dinner parties of painting.”7J.-K. Huysmans, “Appendice (1882),” L’Art moderne (Paris, 1908): 288, as cited and translated in Gerd Muehsam, ed., French Painters and Paintings from the Fourteenth Century to Post-Impressionism (New York: Frederick Ungar, 1970), 523.

The unlined canvas of Under the Orange Tree is somewhat weak and brittle due to age. A few canvas undulations are noticeable along the bottom edge, and splits have formed on the present-day tacking margin. Stretcher cracksstretcher cracks: Linear cracks or deformations in the painting’s surface that correspond to the inner edges of the underlying stretcher or strainer members. have formed near the right edge and sitter’s face. During the 2018 treatment, a discolored synthetic varnish, overpaintoverpaint: Restoration paint that covers original paint that may or may not be damaged. Historically, overpaint has often been applied too broadly, altering the intended aesthetic of the painting and sometimes introducing conceptions foreign to the original artist, thereby altering our understanding of the work and the era to which it belongs., and wax fills were removed. A small amount of paint loss and abrasion were addressed with retouching, and the healthy paint surface was left unvarnished.

Notes

-

The painting was examined using a Hamamatsu vidicon camera.

-

See photograph of Villa with Orange Trees, Nice (1882; private collection) in Jean-Dominique Rey, Berthe Morisot (Paris: Flammarion, S.A., 2010), 151.

-

There are several tack holes and pinholes on the outermost edges of Woman and Child in the Garden at Bougival (1882; Amgueddfa Cymru - National Museum Wales). An earlier abandoned composition is present on the canvas reverse, but it is unclear if these holes relate to pinning of the canvas onto a rigid support for painting, artist re-stretching, or perhaps poor framing that occurred at a later date. Adam Webster, chief conservator, Amgueddfa Cymru - National Museum Wales, Cardiff, email message with the author, December 17, 2019. The Pink Dress (ca. 1870) and Young Woman Seated on a Sofa (ca. 1879), both in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, were also reformatted, although it is unclear whether these were changes made by the artist. Tack holes near the fold-over edges of Young Woman Seated on a Sofa indicate that the painting was once stretched in a slightly smaller format. Charlotte Hale, painting conservator, Metropolitan Museum of Art, email message with the author, September 25, 2020. Hale also observed that The Pink Dress, an unlined painting on its original stretcher, was reduced in size by cutting the width of the left and right stretcher members by half. Morisot may have made this format change herself, as the painting was extensively reworked, but it is also feasible that the smaller format was undertaken at a later date, to fit a smaller frame for example. See Colin B. Bailey, The Annenberg Collection: Masterpieces of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009), 101n11.

-

Mary Schafer, March 24, 2018, examination report, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, no. 2015.13.15.

-

Iris Schaefer, Caroline von Saint-George, and Katja Lewerentz, Painting Light: The Hidden Techniques of the Impressionists (Milan: Skira Editore, 2008), 166.

-

David Bomford, Jo Kirby, John Leighton, and Ashok Roy, Art in the Making: Impressionism (London: Yale University Press, 1991), 181.

-

J.-K. Huysmans, “Appendice (1882),” L’Art moderne (Paris, 1908): 288, as cited and translated in Gerd Muehsam, ed., French Painters and Paintings from the Fourteenth Century to Post-Impressionism (New York: Frederick Ungar, 1970), 523.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Berthe Morisot, Under the Orange Tree, 1889,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/10.37764/78973.5.636.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Berthe Morisot, Under the Orange Tree, 1889,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.636.4033

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Berthe Morisot, Under the Orange Tree, 1889,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/10.37764/78973.5.636.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Berthe Morisot, Under the Orange Tree, 1889,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.636.4033.

Berthe Morisot (1841–1895), Paris, 1889–March 2, 1895;

By descent to her daughter, Julie Rouart (née Manet, 1878–1966), Paris, 1895–at least 1936;

To her grandson, Yves Rouart (b. 1940), Paris, by 1958–at least 1983 [1];

Purchased from Yves Rouart by the Galerie Hopkins-Thomas, Paris, between 1983 and 1986–by 1987 [2];

Purchased from the Galerie Hopkins-Thomas by a private collector, New York, by 1987 [3];

Private collection, Texas, by 1989 [4];

Purchased through Susan L. Brody Associates, New York, by Marion (née Helzberg, 1931–2013) and Henry (1922–2019) Bloch, Shawnee Mission, KS, November 26, 1990–June 15, 2015;

Their gift to The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 2015.

Notes

[1] An inscription preserved on the stretcher says “à Yves.” It was previously thought that Françoise Rouart (b. 1941), granddaughter of Julie Rouart, inherited Under the Orange Tree after Julie’s death. However, correspondence with the Galerie Hopkins-Thomas confirmed that Françoise Rouart never owned the picture. See letter from Marie-Caroline van Herpen, Galerie Hopkins-Thomas, to Brigid Boyle, NAMA, April 30, 2015, NAMA curatorial files.

[2] According to a label preserved on the backing board, “Galerie Hopkins and Thomas” lent Under the Orange Tree to the exhibition Berthe Morisot: Impressionist (National Gallery of Art, September 6–November 29, 1987). However, the exhibition catalogue specifies that the painting was lent from a private collection, “courtesy of Galerie Hopkins-Thomas.” In Alain Clairet et al., Berthe Morisot, 1841–1895: Catalogue raisonné de l’œuvre peint (Paris: CÉRA-nrs, 1997), the authors mistakenly suggest that Under the Orange Tree (no. 241) passed through the Galerie Hopkins-Thomas twice, when in fact it only did so once. See letter from Marie-Caroline van Herpen, Galerie Hopkins-Thomas, to Brigid Boyle, NAMA, April 30, 2015, NAMA curatorial files. Galerie Hopkins-Thomas purchased the painting directly from the Rouart family between 1982 and 1986. See correspondence from Christine Fournié, Galerie Hopkins-Thomas, to Danielle Hampton, NAMA, September 27, 2018, NAMA curatorial files.

[3] See letter from Marie-Caroline van Herpen, Galerie Hopkins-Thomas, to Brigid Boyle, NAMA, April 29, 2016, NAMA curatorial files.

[4] See Inaugural Exhibition of French Impressionist Paintings and Drawings, exh. cat. (New York: Eastlake Gallery, 1989), unpaginated.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Berthe Morisot, Under the Orange Tree, 1889,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/10.37764/78973.5.636.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Berthe Morisot, Under the Orange Tree, 1889,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.636.4033.

Berthe Morisot, Orange Tree Branches, 1889, oil on canvas, 12 19/32 x 20 15/32 in. (32 x 52 cm), Musée Marmottan, Paris.

Berthe Morisot, Parakeet in a Cage, 1889, colored pencil on paper, 7 1/2 x 8 1/4 in. (19 x 21 cm), published in Berthe Morisot (1841–1895), exh. cat. (London: JPL Fine Arts, 1990), 46–47.

Berthe Morisot, Little Girl Hanging a Cage in a Tree, 1890, oil on canvas, 19 1/4 x 2 5/8 in. (49 x 65 cm), Westmont Ridley-Tree Museum of Art, Montecito, CA.

Preparatory Work

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Berthe Morisot, Under the Orange Tree, 1889,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/10.37764/78973.5.636.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Berthe Morisot, Under the Orange Tree, 1889,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.636.4033.

Berthe Morisot, Little Girl Sitting in the Grass, 1889, pastel on paper, 15 5/8 x 19 1/2 in. (39.7 x 49.6 cm), illustrated in Impressionist and Modern Works on Paper (New York: Christie’s, November 5, 2003), 10, (repro.).

Berthe Morisot, Under the Orange Tree, 1889, watercolor, 7 7/8 x 11 27/64 in. (20 x 29 cm), illustrated in Marie-Louise Bataille and Georges Wildenstein, Berthe Morisot: Catalogue des Peintures, Pastels et Aquarelles (Paris: Les Beaux-Arts, 1961), no. 774, pp. 69, (repro.).

Berthe Morisot, Portrait of Julie, 1889, chalk on paper, 10 5/8 x 4 21/64 in. (15 x 11 cm), private collection.

Berthe Morisot, Girl Sitting in a Garden, 1889, pencil on paper, 7 1/2 x 10 1/4 in. (19.1 x 26 cm), illustrated in Modern and Contemporary Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture (New York: Sotheby’s, February 20, 1997), unpaginated, (repro.).

Berthe Morisot, Little Girl and a Cage, 1890, crayon on paper, 8 17/64 x 10 5/8 in. (21 x 27 cm), see reproduction in Box: “Monticelli Adolphe Joseph Thomas; Morisot, Berthe,” Durand-Ruel Photo Archives, National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Berthe Morisot, Under the Orange Tree, 1889,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/10.37764/78973.5.636.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Berthe Morisot, Under the Orange Tree, 1889,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.636.4033.

Berthe Morisot (Madame Eugène Manet), 1841–1896, Galerie Durand-Ruel, Paris, March 5–21, 1896, no. 95, as Sous l’oranger.

Exposition Berthe Morisot, Galerie Durand-Ruel, Paris, April 23–May 10, 1902, no. 15, as Sous l’Oranger.

Salon d’Automne, 5ème Exposition: Ouvrages de Peinture, Sculpture, Dessin, Gravure, Architecture et Art décoratif; Exposition Rétrospective d’Œuvres de Berthe Morisot, Grand Palais, Paris, October 1–22, 1907, no. 32, as Sous l’oranger.

Berthe Morisot (Madame Eugène Manet), 1841–1895, Knoedler and Co., London, May–June 1936, no. 20, as Sous l’oranger.

Berthe Morisot (1841–1895), Musée de l’Orangerie, Paris, Summer 1941, no. 81, as Sous l’oranger.

Exposition Berthe Morisot, 1841–1895, Galerie Motte, Geneva, June 12–30, 1951, no. 11, as Fille sous les orangers.

Hommage à Berthe Morisot et à Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Musée Municipal, Limoges, France, July 19–October 10, 1952, no. 10, as Sous l’oranger.

Plaisirs de la Campagne, Galerie Charpentier, Paris, 1954, hors cat.

Exposition Berthe Morisot, Château-Musée de Dieppe, France, July 5–September 30, 1957, no. 42, as Sous l’oranger (Nice).

Exposition Berthe Morisot (1841–1895): Peintures, Aquarelles, Dessins, Musée Toulouse-Lautrec, Albi, France, July 1–September 15, 1958, no. 47, as Sous l’oranger.

Berthe Morisot, Musée Jenisch Vevey, Vevey, Switzerland, June 24–September 3, 1961, no. 237, as Sous l’Oranger.

Berthe Morisot, Musée Jacquemart-André, Paris, 1961, no. 66, as Sous l’Oranger.

Berthe Morisot, Galerie Lucien Blanc, Aix-en-Provence, July 6–28, 1962, no. 19, as Sous l’oranger.

Six Femmes-Peintres: Berthe Morisot, Eva Gonzalès, Mary Cassatt, Suzanne Valadon, Marie Laurencin, Nathalia Gontcharova, Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art, Nagoya, Japan, March 29–April 14, 1983; Tochigi Prefectural Museum of Fine Arts, Utsunomiya, Japan, June 5–July 3, 1983; Kumamoto Prefectural Museum of Art, Kumamoto, Japan, July 14–August 14, 1983, no. 6, as Sous l’Oranger.

Berthe Morisot: Impressionist, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, September 6–November 29, 1987; Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, TX, December 12, 1987–February 21, 1988; Mount Holyoke College Art Museum, South Hadley, MA, March 14–May 9, 1988, no. 80, as Under the Orange Tree.

Inaugural Exhibition of French Impressionist Paintings and Drawings, Eastlake Gallery, New York, October 20, 1989, unnumbered, as Sous l’Oranger (Portrait de Julie Manet).

Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, June 9–September 9, 2007, no. 18, as Under the Orange Tree (Sous l’oranger).

Berthe Morisot, Woman Impressionist, Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec, June 21–September 23, 2018; The Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, October 21, 2018–January 14, 2019; Dallas Museum of Art, February 24–May 26, 2019; Musée d’Orsay, Paris, June 18–September 22, 2019, no. 74, as Under the Orange Tree (Québec only).

References

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Berthe Morisot, Under the Orange Tree, 1889,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/10.37764/78973.5.636.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Berthe Morisot, Under the Orange Tree, 1889,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.636.4033.

Berthe Morisot (Madame Eugène Manet): exposition de son œuvre, exh. cat., 2nd ed. (Paris: Durand-Ruel, 1896), 23, as Sous l’oranger.

Exposition Berthe Morisot, exh. cat. (Paris: Durand-Ruel, 1902), unpaginated, as Sous l’Oranger.

Salon d’Automne, 5ème Exposition: Catalogue des Ouvrages de Peinture, Sculpture, Dessin, Gravure, Architecture et Art décoratif; Exposition Rétrospective d’Œuvres de Berthe Morisot, exh. cat. (Paris: Compagnie Française des Papiers-Monnaie, 1907), 256, as Sous l’oranger.

Louis Rouart, “Berthe Morisot (Mme Eugène Manet), 1841–1895,” Art et Décoration: Revue Mensuelle d’art Moderne, no. 5 (May 1908): 173, (repro.), as Sous l’Oranger.

Berthe Morisot (Madame Eugène Manet), 1841–1895, exh. cat. (London: M. Knoedler, 1936), unpaginated, as Sous l’oranger.

Berthe Morisot, 1841–1895, exh. cat. (Paris: Musée de l’Orangerie, 1941), 19, 30, as Sous l’oranger.

Exposition Berthe Morisot, 1841–1895, exh. cat. (Geneva: Galerie Motte, 1951), unpaginated, as Fille sous les orangers.

Hommage à Berthe Morisot et à Pierre-Auguste Renoir: catalogue de l’exposition, exh. cat. (Limoges, France: Musée Municipal, 1952), 32, as Sous l’oranger.

Exposition Berthe Morisot, exh. cat. (Dieppe, France: Château-Musée de Dieppe, 1957), 5, as Sous l’oranger (Nice).

Denis Rouart, ed., The Correspondence of Berthe Morisot with her family and her friends, trans. Betty W. Hubbard (New York: E. Weyhem 1957), 146.

Exposition Berthe Morisot (1841–1895): peintures, aquarelles, dessins, exh. cat. (Albi, France: Musée Toulouse-Lautrec, 1958), 32, as Sous l’oranger.

Possibly Rosamond Bernier, “Dans la lumiere impressioniste,” L’Oeil, no. 53 (May 1959): 39, (repro.).

Georges Reyer, “Le déchirant amour de Berthe Morisot,” Match, no. 627 (April 15, 1961): 91, (repro.).

Marie-Louise Bataille and Georges Wildenstein, Berthe Morisot: Catalogue des Peintures, Pastels et Aquarelles (Paris: Les Beaux-Arts, 1961), no. 237, pp. 38, 58, 69, (repro.), as Sous l’Oranger.

Berthe Morisot, exh. cat. (Paris: Musée Jacquemart André, 1961), unpaginated, as Sous l’Oranger.

Berthe Morisot, exh. cat. (Vevey, Switzerland: Musée Jenisch Vevey, 1961), 10, as Sous l’Oranger.

Berthe Morisot, 1841–1895, exh. cat. (Aix-en-Provence: Galerie Lucien Blanc, 1962), unpaginated, as Sous L’oranger.

“The Great Ones All Painted Us: Renoir, Degas, Manet and Mother; A French Lady’s Engaging Recollections,” Life 54, no. 19 (May 10, 1963): 53–55, (repro.).

Jean Dominique Rey, Berthe Morisot (Paris: Flammarion, 1982), 63, 82, (repro.), as Sous l’Oranger.

Six Femmes-Peintres: Berthe Morisot, Eva Gonzalès, Mary Cassatt, Suzanne Valadon, Marie Laurencin, Nathalia Gontcharova, exh. cat. (Tokyo: Asahi Shimbun, 1983), 26, 160, (repro.), as Sous l’Oranger.

Charles F. Stuckey and William P. Scott, Berthe Morisot: Impressionist, exh. cat. (New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1987), 138, 140, 142, 221, (repro.), as Under the Orange Tree.

Inaugural Exhibition of French Impressionist Paintings and Drawings, exh. cat. (New York: Eastlake Gallery, 1989), unpaginated, as Sous l’Oranger (Portrait de Julie Manet).

Berthe Morisot (1841–1895), exh. cat. (London: JPL Fine Arts, 1990), 47, as Sous l’oranger.

Alain Clairet, Delphine Montalant and Yves Rouart, Berthe Morisot, 1841–1895: Catalogue raisonné de l’œuvre peint (Paris: CÉRA-nrs éditions, 1997), no. 241, pp. 232, 335, (repro.), as Sous l’Oranger.

Margaret Shennan, Berthe Morisot: The First Lady of Impressionism (Gloucestershire, England: Sutton, 2000), 245, 285, as Under the Orange Tree.

Jean-Dominique Rey, Berthe Morisot: La Belle Peintre (Paris: Flammarion, 2002), 81, as Sous l’oranger.

Denise Brahimi, La peinture au féminin: Berthe Morisot et Mary Cassatt (Paris: Jean-Paul Rocher, 2003), 104–05, as Sous l’oranger.

Bobbie Leigh, “Magnificent Obsession,” Art and Antiques 29, no. 6 (June 2006): 62, as Under the Orange Tree.

Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 11, 15, 98, 100–03, 159, (repro.), as Under the Orange Tree (Sous l’oranger).

“A tiny Renoir began impressive obsession Bloch collection gets its first public exhibition,” Kansas City Star (June 2, 2007): https://www.kansascity.com/latest-news/article294930/A-tiny-Renoir-began-impressive-obsession-Bloch-collection-gets-its-first-public-exhibition.html.

Alice Thorson, “First Public Exhibition: Marion and Henry Bloch’s art collection,” Kansas City Star (June 3, 2007): E4, as Sous l’Oranger.

Carol Vogel, “Inside Art: Kansas City Riches,” New York Times 159, no. 54,942 (February 5, 2010): C26.

Jean-Dominique Rey and Sylivie Patry, Berthe Morisot (Paris: Flammarion, 2010), 109, as Sous l’oranger (Under the Orange Tree).

Diane Stafford, “Bloch Gift to Go for Nelson Upgrade,” Kansas City Star 135, no. 203 (April 8, 2015): A8.

“Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Officially Accessions Bloch Impressionist Masterpieces,” Artdaily.org (July 25, 2015): http://artdaily.com/news/80246/Nelson-Atkins-Museum-of-Art-officially-accessions-Bloch-Impressionist-masterpieces#.V6oGwlKFO9.

Julie Paulais, “Le Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art reçoit des tableaux impressionnistes en échange de leurs répliques,” Le Journal des arts (July 30, 2015): http://www.lejournaldesarts.fr/site/archives/docs_article/129801/le-nelson-atkins-museum-of-art-recoit-des-tableaux-impressionnistes-en-echange-de-leurs-repliques.php.

Nancy Staab, “Van Gogh is a Go!” 435: Kansas City’s Magazine (September 2015): 76.

Robin de Clercq, “How Google will Preserve Art, One Gigapixel at a Time,” Resource (June 7, 2016): http://resourcemagonline.com/2016/06/how-google-will-preserve-art-one-gigapixel-at-a-time/67304/.

“Nelson-Atkins to unveil renovated Bloch Galleries of European Art in winter 2017,” Artdaily.org (July 20, 2016): http://artdaily.com/news/88852/Nelson-Atkins-to-unveil-renovated-Bloch-Galleries-of-European-Art-in-winter-2017-#.W-nfbpNKi70.

Catherine Futter et al., Bloch Galleries: Highlights from the Collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2016), 87, (repro.).

Albert Hect, “Henry Bloch’s Masterpieces Collection to Go on Display at Nelson-Atkins Museum,” Jewish Business News (February 26, 2017): http://jewishbusinessnews.com/2017/02/26/henry-bloch-masterpieces-collection/.

David Frese, “Inside the Bloch Galleries: An interactive experience,” Kansas City Star 137, no. 169 (March 5, 2017): 1D, 5D, (repro.), as Under the Orange Tree.

“Editorial: Thank you, Henry and Marion Bloch,” Kansas City Star (March 7, 2017): http://www.kansascity.com/opinion/editorials/article137040948.html.

“The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: Presenting the Bloch Galleries,” New York Times (March 5, 2017).

Hampton Stevens, “(Not Actually) 12 Things To Do During The Big 12 Tournament,” Flatland: KCPT’s Digital Magazine (March 9, 2017): http://www.flatlandkc.org/arts-culture/sports/not-actually-12-big-12-tournament/.

Laura Spencer, “The Nelson-Atkins’ Bloch Galleries feature Old Masterworks and New Technology,” KCUR (March 10, 2017): http://kcur.org/post/nelson-atkins-bloch-galleries-feature-old-masterworks-and-new-technology#stream/0.

Victoria Stapley-Brown, “Nelson-Atkins Museum’s new European art galleries come with a ‘love story’,” Art Newspaper (March 10, 2017): http://theartnewspaper.com/news/museums/nelson-atkins-museum-s-new-european-art-galleries-come-with-a-love-story/.

Harry Bellet, “Don du ciel pour le Musée Nelson-Atkins,” Le Monde (March 13, 2017): http://www.lemonde.fr/arts/article/2017/03/13/don-du-ciel-pour-le-musee-nelson-atkins_5093543_1655012.html.

Menachem Wecker, “Jewish Philanthropist Establishes Kansas City as Cultural Mecca,” Forward (March 14, 2017): http://forward.com/culture/365264/jewish-philanthropist-establishes-kansas-city-as-cultural-mecca/.

Juliet Helmke, “The Bloch Collection Takes up Residence in Kansas City’s Nelson Atkins Museum,” BoulinArtInfo International (March 15, 2017): http://www.blouinartinfo.com/news/story/2005267/the-bloch-collection-takes-up-residence-in-kansas-citys.

Erich Hatala Matthes, “Digital replicas are not soulless – they help us engage with art,” Apollo: The International Art Magazine (March 23, 2017): https://www.apollo-magazine.com/digital-replicas-3d-printing-original-artworks/.

Louise Nicholson, “How Kansas City got its magnificent museum,” Apollo (April 7, 2017): https://www.apollo-magazine.com/how-kansas-city-got-its-magnificent-museum/.

Cindy Kang et al., Berthe Morisot: Woman Impressionist, exh. cat. (New York: Rizzoli Electa, 2018), 208, (repro.), as Under the Orange Tree.

Robert D. Hershey Jr., “Henry W. Bloch, Tax-Preparation Pioneer (and Pitchman), Is Dead at 96,” New York Times (April 23, 2019): https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/23/obituaries/henry-w-bloch-dead.html.

Claire Selvin, “Henry Wollman Bloch, Collector and Prominent Benefactor of Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Is Dead at 96,” ArtNews (April 23, 2019): http://www.artnews.com/2019/04/23/henry-bloch-dead-96/.

Frank Morris, “Henry Bloch, Co-Founder Of H&R Block, Dies At 96,” npr.org (April 24, 2019): https://www.npr.org/2019/04/24/716641448/henry-bloch-co-founder-of-h-r-block-dies-at-96.

“Henry Wollman Bloch (1922–2019),” Art Forum (April 24, 2019): https://www.artforum.com/news/henry-wollman-bloch-1922-2019-79547.

Ignacio Villarreal, “Nelson-Atkins mourns loss of Henry Bloch,” ArtDaily.org (April 24, 2019): http://artdaily.com/news/113035/Nelson-Atkins-mourns-loss-of-Henry-Bloch#.XMB76qR7laQ.

Eric Adler, “Sold for $3.25 million, Bloch’s home in Mission Hills may be torn down,” Kansas City Star 141, no. 90 (December 16, 2020): 2A.