Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Thomas Couture, The Illness of Pierrot, 1867–1868,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.508.5407.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Thomas Couture, The Illness of Pierrot, 1867–1868,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.508.5407.

In the summer of 1859, French painter and teacher Thomas Couture was newly married and becoming increasingly disenchanted with life in Paris. He closed his successful atelier, which had launched the careers of such artists as Edouard Manet (1832–1883) and William Morris Hunt (American, 1824–1879), and moved with his wife to Senlis, some thirty miles north of the capital. This change in residence coincided with a shift in Couture’s primary clientele and subject matter. Instead of prioritizing large imperial commissions, he began producing more modestly sized easel paintings that would appeal to private collectors, including landscapes, genre scenes, and satirical allegories.

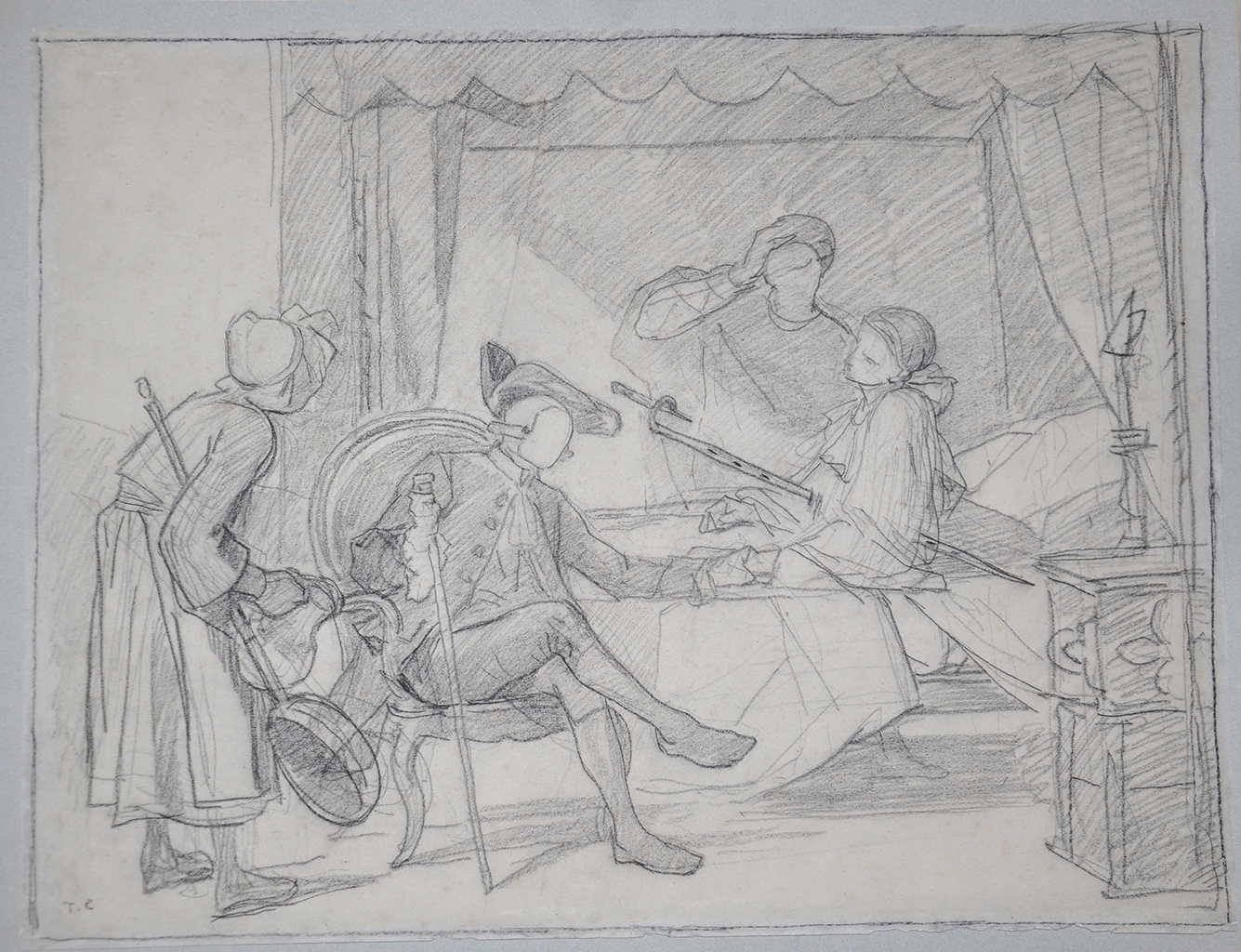

The Illness of Pierrot belongs to the latter category. Completed around 1868, it is one of seven harlequinades, or pictures incorporating Harlequin and other stock characters from the commedia dell’artecommedia dell’arte: Italian for “comedy of professional artists.” A theatrical form involving improvisation and a cast of stock characters that emerged in northern Italy in 1545 and rapidly gained popularity throughout Europe. Its heyday was the sixteenth through eighteenth centuries., that Couture undertook between 1855 and 1870.1Only two of the seven pictures are inscribed with dates. The Illness of Pierrot bears Couture’s initials but no year of creation. Albert Boime dated it to circa 1859–1860 or 1860–1863 in his monograph on Couture, favoring the former date range in his image caption and the latter in his text; see Albert Boime, Thomas Couture and the Eclectic Vision (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1980), 321, 324–26. Most scholars have followed Boime’s lead, but new evidence supports a later date of creation. In a letter to Couture dated June 1, 1868, French painter Edouard Armand-Dumaresq (1826–1895) asked on behalf of American collector William Tilden Blodgett (1823–1875) when he expected to finish The Illness of Pierrot. Blodgett already owned several of Couture’s harlequinades and sought to acquire another one for his collection. Couture’s reply has been lost, but it is likely that he completed The Illness of Pierrot sometime that year. See Armand-Dumaresq to Couture, June 1, 1868, Archives Couture, Musée national du château de Compiègne. The scene openly pokes fun at the medical profession. Seated at the center is a tricorntricorn: A cocked hat with the brim turned up on three sides.-wearing doctor who takes the pulse of a bedridden patient and attempts to diagnose what ails him. The man slumped against the pillows is Pierrot, a “comically inept male servant” given to laziness and excessive eating.2I borrow this description from Judy Sund, “Why So Sad? Watteau’s Pierrots,” Art Bulletin 98, no. 3 (September 2016): 323. Although not one of the original commedia dell’arte characters, Pierrot gained popularity in Paris during the 1680s when the Comédie-ItalienneComédie-Italienne: The French term for Italian commedia dell’arte companies who performed in France. Coined in 1680, it was intended to distinguish Italian plays from native French plays. The Comédie-Italianne was expelled from Paris in 1697 but permitted to return in 1716. See commedia dell’arte. added him to their roster of social types.3Sund, “Why So Sad?” 323. Here, Pierrot is clearly struggling with indigestion and a hangover: telltale scraps of food and bottles of alcohol litter the foreground. Pierrot’s sometime-nemesis Harlequin, dressed in his trademark lozengedlozenged: Ornamented with diamond shapes of alternate colors. costume, feigns anguish over his condition, even though he and the maid know precisely what caused it. Only the physician remains puzzled by Pierrot’s symptoms, blinded by his supposed erudition. A French inscription at the upper left reads: “Science makes the doctor see what is not and prevents him from seeing what is obvious to everyone.”

Couture derived particular inspiration from two of Molière’s late-career comedies: Le médecin malgré lui (1666; The Physician in Spite of Himself) and Le Malade imaginaire (1673; The Imaginary Invalid). In the former, an alcoholic woodcutter named Sganarelle is forced to masquerade as a doctor due to the machinations of his wife, Martine. Called on to diagnose a woman named Lucinde, who has stopped speaking in order to forestall an arranged marriage, he attributes her mysterious silence to “peccant humours” and suggests bed rest and wine-soaked bread as remedies.13Molière [Jean-Baptiste Poquelin], The Dramatic Works of Molière, trans. Henri Van Laun (Philadelphia: Gebbie and Barrie, 1878), 2:278–80. By the third act, Sganarelle has grown so confident in this scam that he boasts to Lucinde’s lover, Léandre: “In our business we may spoil a man without its costing us a farthing. The blunders are never put down to us, and it is always the fault of the fellow who dies.”14Molière, The Dramatic Works of Molière, 2:284. In Le Malade imaginaire, similar drollery ensues. A hypochondriac named Argan is so convinced of his imminent demise that he permits his physician, Mr. Purgon, to prescribe countless enemas and other equally ineffective “cures.” He also betroths his daughter, Angélique, to Purgon’s hapless nephew, Thomas Diafoirus (a doctor-in-training), so as to have multiple members of the medical establishment at his disposal. Even when Purgon and Diafoirus provide contradictory accounts of Argan’s nonexistent illness—with one blaming his liver and the other his spleen—Argan’s faith in physicians never wavers.

Both plays contain one or more characters who recognize the doctors as bumbling frauds. In Le médecin malgré lui, nurse Jacqueline warns Lucinde’s father that “all these physicians do her no good; . . . your daughter wants something else than rhubarb and senna.”15Molière, The Dramatic Works of Molière, 2:271–72. In Le Malade imaginaire, Argan’s servant Toinette discerns that Purgon and his apothecary are milking her employer for money, and his brother Béralde likewise sees through their pedantry (“the whole excellence of their art consists in a pompous gibberish”).16Molière, The Dramatic Works of Molière, 3:548. These characters are reincarnated in the Nelson-Atkins composition as the charwoman, who stares incredulously at the physician. She carries a water pitcher and bed warmer, knowing that fluids and sleep are all Pierrot needs. Her sensible ministrations stand in contrast to the doctor’s foolish fixation on Pierrot’s pulse.17This preoccupation with Pierrot’s pulse is another nod to Molière. In Le médecin malgré lui, Sganarelle touches Lucinde’s wrist and then declares, “The pulse tells me that your daughter is dumb”—even though her muteness had already been established. See Molière, The Dramatic Works of Molière, 2:277. In Le Malade imaginaire, Diafoirus deems Argan’s pulse to be “a little irregular . . . which is a sign of intemperature in the splenetic parenchyma, which means the milt.” His use of medical jargon impresses Argan but signals to audience members that Diafoirus is a quack. See Molière, The Dramatic Works of Molière, 3:538. Like Molière, Couture enjoyed juxtaposing an astute servant and obtuse doctor.

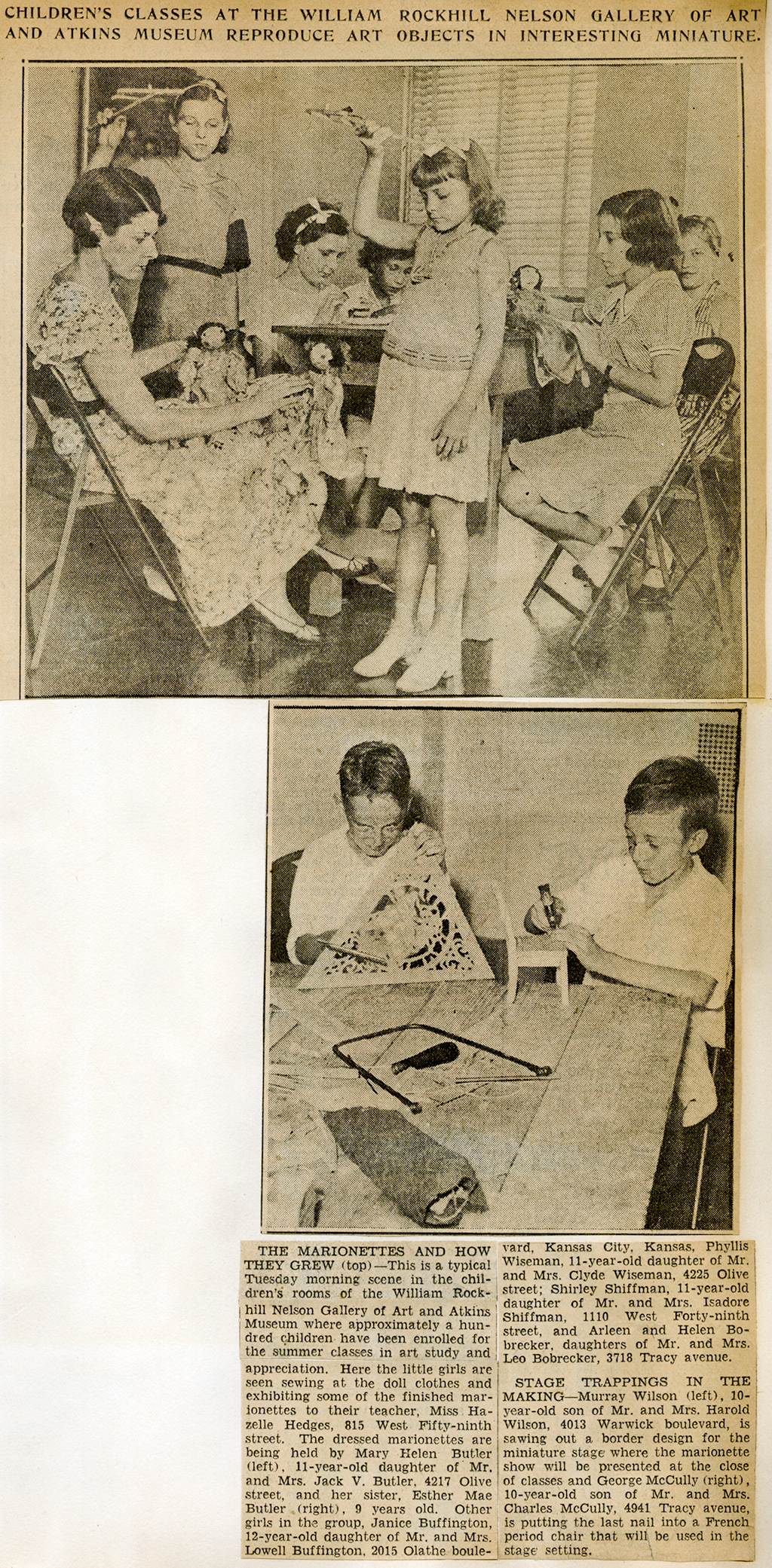

Couture’s interest in theater is clear on a purely formal level, too. The bed hangings evoke stage curtains, and the figures’ exaggerated gestures and facial expressions were hallmarks of Molière’s plays and the commedia dell’arte.18Compare, for example, Pierrot’s mournful look in Couture’s painting to the pained expression of French mime Jean-Charles Deburau (1829–1873) in Nadar and Adrien Tournachon, Pierrot in Pain, ca. 1854–1855, albumen silver print from glass negative, 10 1/16 x 8 1/16 in. (25.6 x 20.4 cm), Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005.100.255, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/285851. Deburau performed as Pierrot at the Théâtre des Funambules in Paris between 1847 and 1855; during this period, he posed for several “têtes d’expression de Pierrot” to help boost the Tournachon brothers’ struggling business. Indeed, the entire scene appears ready-made for the stage—which may be why the Nelson-Atkins produced a theatrical adaptation of The Illness of Pierrot in the summer of 1934, only a few months after the museum’s inauguration.19For the story of this theatrical adaptation, see “Little Hands in Art,” Kansas City Star, August 14, 1934, 9; “Marionette Shows Thursday,” Kansas City Star, August 28, 1934, 2; M[inna] K. P[owell], “Gallery’s First Anniversary To Be Celebrated Next Week,” Kansas City Star, December 6, 1934, 10; and Jeanne Turner Baldwin, “History of Marionettes and Puppets at the Nelson-Atkins Museum,” in Historical Marionettes and Puppets: From the Collection of Betty Nichol, Jeanne Baldwin, and James Seldelman, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1996), unpaginated. Additional information can be found in the Lindsay Hughes Cooper Oral History Interviews, December 8, 1993, and May 5, 1994, NAMA Archives, Ephemera Collection, Record Group 70. As the story goes, staff members were surprised by the tremendous response to a newspaper advertisement promoting a free class in art appreciation for children. Scrambling to devise an engaging curriculum for more than 125 youths, they decided to write and perform a play based on a work in the collection. Ruth Lindsay Hughes, an assistant to director Paul Gardner, authored the script, which she titled “Food, Not Thought,” and assigned her colleagues the various roles. The show was a triumph, despite the novice actors having only one day to rehearse. So enthusiastic were the children that Hughes’s coworker, Hazelle Hedges (1910–1984)—an expert puppet-maker and puppeteer—proposed restaging the play with marionettes.20Both Hughes and Hedges had trailblazing careers. Hughes became acting curator of Asian art at the Nelson-Atkins during World War II and later worked for Asian art dealer C. T. Loo. Hedges founded her own puppet business in 1935 and became the largest exclusive manufacturer of marionettes and puppets in the world. For more on these pioneering women, see “Lindsay Hughes Cooper,” Kansas City Star, November 18, 1997, B-4; “Generations: Women in the Early History of the Nelson-Atkins,” Google Arts and Culture, accessed February 2, 2023, https://artsandculture.google.com/story/tAVhYuavsnNtKw; “Puppet Manufacturer Hazelle Rollins Dies,” Kansas City Times, March 26, 1984, B-6; and Mike Joly, Hazelle and Her Marionettes: Creating the World’s Largest Puppet Company (Independence, MO: Puppetry Arts Institute, 2005).

Among the first French paintings acquired by the Nelson-Atkins, The Illness of Pierrot remains the museum’s only satirical allegory in oil by a French artist. Part homage to Molière, part diatribe against doctors, it offers insight into Couture’s state of mind as he retreated from the competitive artistic milieu of Paris and approached the final decade of his career.

Notes

-

Only two of the seven pictures are inscribed with dates. The Illness of Pierrot bears Couture’s initials but no year of creation. Albert Boime dated it to circa 1859–1860 or 1860–1863 in his monograph on Couture, favoring the former date range in his image caption and the latter in his text; see Albert Boime, Thomas Couture and the Eclectic Vision (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1980), 321, 324–26. Most scholars have followed Boime’s lead, but new evidence supports a later date of creation. In a letter to Couture dated June 1, 1868, French painter Edouard Armand-Dumaresq (1826–1895) asked on behalf of American collector William Tilden Blodgett (1823–1875) when he expected to finish The Illness of Pierrot. Blodgett already owned several of Couture’s harlequinades and sought to acquire another one for his collection. Couture’s reply has been lost, but it is likely that he completed The Illness of Pierrot sometime that year. See Armand-Dumaresq to Couture, June 1, 1868, Archives Couture, Musée national du château de Compiègne.

-

I borrow this description from Judy Sund, “Why So Sad? Watteau’s Pierrots,” Art Bulletin 98, no. 3 (September 2016): 323.

-

Sund, “Why So Sad?” 323.

-

Thomas Couture, Méthode et entretiens d’atelier (Paris: Typ. de L. Guérin, 1867), 133. Harlequin ran “avec la grâce d’un jeune chat.” Translations are by Brigid M. Boyle unless otherwise noted.

-

Couture, Méthode et entretiens d’atelier, 134. Harlequin watched Couture “en gazouillant comme une véritable hirondelle.”

-

For example, Alain de Leiris, “Thomas Couture, The Painter,” in Thomas Couture: Paintings and Drawings in American Collections, exh. cat. (College Park, MD: University of Maryland, 1970), 20; Boime, Thomas Couture and the Eclectic Vision, 293; and Jennifer Forrest, Decadent Aesthetics and the Acrobat in French Fin de Siècle (New York: Routledge, 2020), 43.

-

A larger version of The Duel after the Masked Ball remains in private hands. See Tableaux Anciens: Tableaux et dessins du XIXe siècle (Monte Carlo, Monaco: Sotheby’s, June 20, 1987), lot 448, as Le Duel de Pierrot.

-

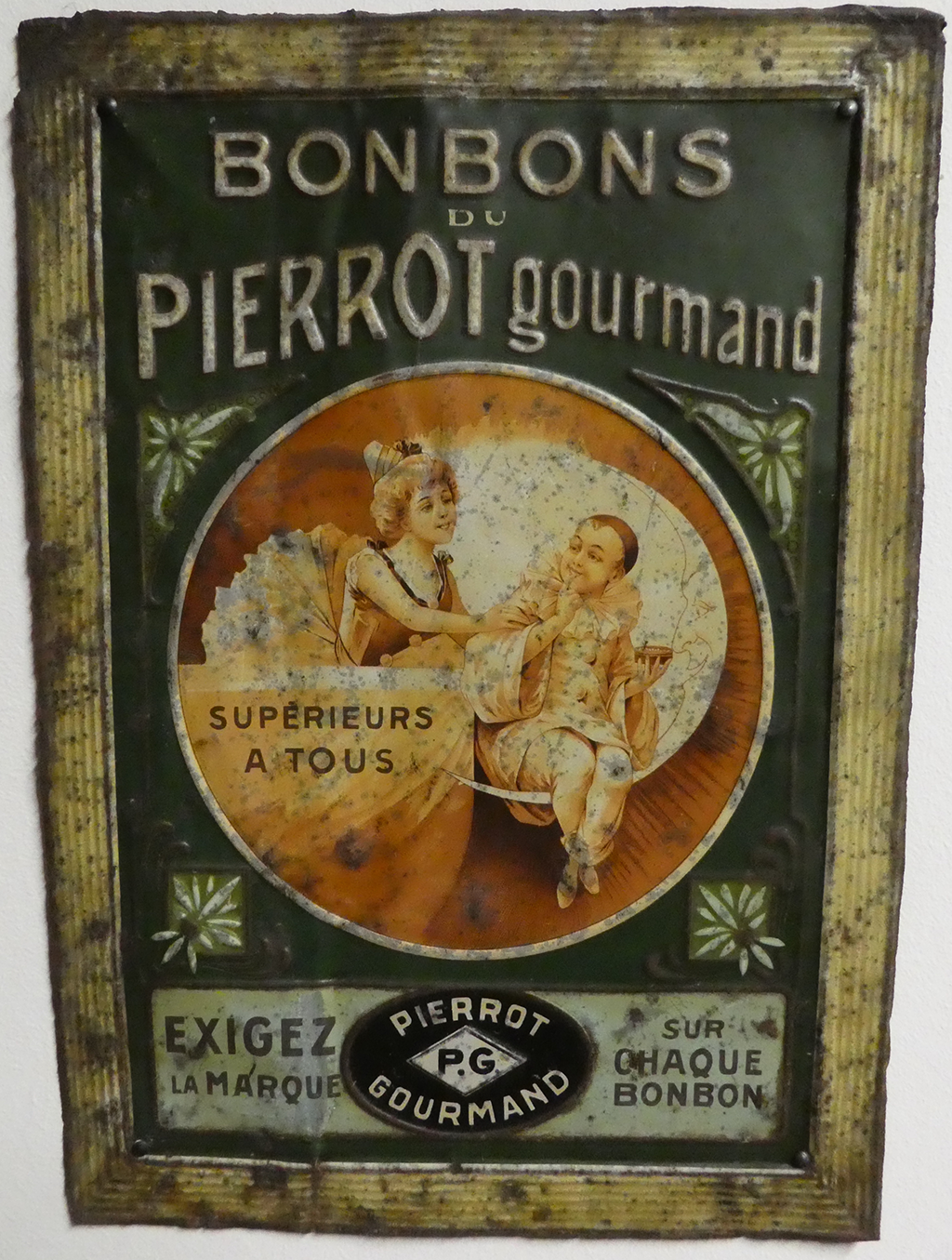

The company name was subsequently shortened to “Pierrot Gourmand.” See “The Pierrot Gourmand Adventure,” Pierrot Gourmand, accessed January 30, 2023, https://en.pierrot-gourmand.com/our-history. To this day, customers can still purchase ceramic lollipop-holders featuring Pierrot’s bust; see https://www.pierrot-gourmand.com/coffret-gourmandise-buste-sucettes.html.

-

George P[eter] A[lexander] Healy, Reminiscences of a Portrait Painter (Chicago: A. C. McClurg, 1894), 98. Couture and Healy met in the studio of Antoine-Jean Gros (1771–1835).

-

Boime, Thomas Couture and the Eclectic Vision, 326; Healy, Reminiscences of a Portrait Painter, 105. Couture’s student Ernest Wadsworth Longfellow (1845–1921) described him as “a short, stout man” with “a rather heavy and puffy face.” See Ernest W[adsworth] Longfellow, “Reminiscences of Thomas Couture,” Atlantic Monthly 52, no. 310 (August 1883): 236–37.

-

According to Healy, “He was so violent in his animosity that, when he fell ill, he refused all medical aid.” See Healy, Reminiscences of a Portrait Painter, 105.

-

Translated in Boime, Thomas Couture and the Eclectic Vision, 323.

-

Molière [Jean-Baptiste Poquelin], The Dramatic Works of Molière, trans. Henri Van Laun (Philadelphia: Gebbie and Barrie, 1878), 2:278–80.

-

Molière, The Dramatic Works of Molière, 2:284.

-

Molière, The Dramatic Works of Molière, 2:271–72.

-

Molière, The Dramatic Works of Molière, 3:548.

-

This preoccupation with Pierrot’s pulse is another nod to Molière. In Le médecin malgré lui, Sganarelle touches Lucinde’s wrist and then declares, “The pulse tells me that your daughter is dumb”—even though her muteness had already been established. See Molière, The Dramatic Works of Molière, 2:277. In Le Malade imaginaire, Diafoirus deems Argan’s pulse to be “a little irregular . . . which is a sign of intemperature in the splenetic parenchyma, which means the milt.” His use of medical jargon impresses Argan but signals to audience members that Diafoirus is a quack. See Molière, The Dramatic Works of Molière, 3:538.

-

Compare, for example, Pierrot’s mournful look in Couture’s painting to the pained expression of French mime Jean-Charles Deburau (1829–1873) in Nadar and Adrien Tournachon, Pierrot in Pain, ca. 1854–1855, albumen silver print from glass negative, 10 1/16 x 8 1/16 in. (25.6 x 20.4 cm), Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005.100.255, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/285851. Deburau performed as Pierrot at the Théâtre des Funambules in Paris between 1847 and 1855; during this period, he posed for several “têtes d’expressiontête d’expression: French term for a study of the face intended to evoke a particular emotion or state of mind. de Pierrot” to help boost the Tournachon brothers’ struggling business.

-

For the story of this theatrical adaptation, see “Little Hands in Art,” Kansas City Star, August 14, 1934, 9; “Marionette Shows Thursday,” Kansas City Star, August 28, 1934, 2; M[inna] K. P[owell], “Gallery’s First Anniversary To Be Celebrated Next Week,” Kansas City Star, December 6, 1934, 10; and Jeanne Turner Baldwin, “History of Marionettes and Puppets at the Nelson-Atkins Museum,” in Historical Marionettes and Puppets: From the Collection of Betty Nichol, Jeanne Baldwin, and James Seldelman, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1996), unpaginated. Additional information can be found in the Lindsay Hughes Cooper Oral History Interviews, December 8, 1993, and May 5, 1994, NAMA Archives, Ephemera Collection, Record Group 70.

-

Both Hughes and Hedges had trailblazing careers. Hughes became acting curator of Asian art at the Nelson-Atkins during World War II and later worked for Asian art dealer C. T. Loo. Hedges founded her own puppet business in 1935 and became the largest exclusive manufacturer of marionettes and puppets in the world. For more on these pioneering women, see “Lindsay Hughes Cooper,” Kansas City Star, November 18, 1997, B-4; “Generations: Women in the Early History of the Nelson-Atkins,” Google Arts and Culture, accessed February 2, 2023, https://artsandculture.google.com/story/tAVhYuavsnNtKw; “Puppet Manufacturer Hazelle Rollins Dies,” Kansas City Times, March 26, 1984, B-6; and Mike Joly, Hazelle and Her Marionettes: Creating the World’s Largest Puppet Company (Independence, MO: Puppetry Arts Institute, 2005).

-

“Little Hands in Art,” 9.

-

“Children’s Classes at the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Atkins Museum Reproduce Art Objects in Interesting Miniature,” Kansas City Star, August 14, 1934, 9.

-

I borrow this description of Pierrot’s situation from M[inna] K. P[owell], “Art: Mr. Parsons Will Be Heard Thursday Night on ‘The Italian Renaissance,’” Kansas City Times, April 12, 1932, 10.

Technical Entry

Technical entry forthcoming.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Thomas Couture, The Illness of Pierrot, 1867–1868,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.508.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Thomas Couture, The Illness of Pierrot, 1867–1868,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.508.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Thomas Couture, The Illness of Pierrot, 1867–1868,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.508.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Thomas Couture, The Illness of Pierrot, 1867–1868,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.508.4033.

Purchased from the artist by William Tilden Blodgett (1823–1875), New York, after June 1, 1868 [1];

Vincent-Claude Laurent-Richard (1811–1886), Neuilly-sur-Seine, France, by May 23, 1878–at least September 1880 [2];

Possibly by descent to his daughter, Augustine-Victoire Charcot (née Laurent-Richard, 1834–1899), and his son-in-law, Jean-Martin Charcot (1825–1893), Paris, by February 22, 1886 [3];

Probably Jason “Jay” Gould (1836–1892), New York, before December 2, 1892 [4];

William “Vincent” Astor (1891–1959), New York, before April 20, 1926;

Purchased at his sale, Paintings, furnishings and architectural fittings of the Astor residence, 840 Fifth Avenue, New York: paintings of the XIX century French school, furniture, tapestries and objects of art, carved wood wall paneling, painted insets and ceilings, bronzes and ironwork, American Art Association, New York, April 20, 1926, lot 410, as Pierrot Malade, 1926;

Marcel Jules Rougeron (1875–1954), New York, by 1932 [5];

With J. M. Hardy, Van Diest Gallery, New York, by April 5, 1932 [6];

Purchased from Van Diest, through Harold Woodbury Parsons, by the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1932.

Notes

[1] See letter from Edouard Armand-Dumaresq (1826–1895) to Thomas Couture, June 1, 1868, Archives Couture, Musée national du château de Compiègne, in which he relays a message from Blodgett, communicated to him via American painter Edward Harrison May (1824–1887). Blodgett wanted to know when Couture expected to finish The Illness of Pierrot and said his banker in Paris would transfer payment to the artist as soon as it was ready. We thank Jean-François Delmas, Conservateur général du Patrimoine, Musée national du château de Compiègne, for sharing this piece of correspondence.

[2] Laurent-Richard was a tailor and art collector. He offered the painting for sale at Tableaux Modernes et de Tableaux Anciens Composant la Collection Laurent-Richard, Hôtel Drouot, Paris, May 23–25, 1878, no. 8, as Pierrot malade, but according to an annotated sales catalogue owned by Durand-Ruel et Cie, it was bought in by Laurent-Richard. See email from Paul-Louis Durand-Ruel and Flavie Durand-Ruel, Durand-Ruel et Cie., Paris, to Nicole Myers, Nelson-Atkins, January 11, 2016, NAMA curatorial files. Other annotated catalogues from the Internet Archive and Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, list a purchase price of 8000 francs. Couture scholar Albert Boime suggested that “Gillet” was the buyer. This may actually refer to Charles Joseph Pillet, who was the auctioneer at the 1878 sale. See Boime (Albert) Papers, UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, Los Angeles, “Pierrot,” LSC.1834, Series 3, box 14, folder 9, p. 193. Special thanks to Maxwell Zupke and Neil M. Hodge, Public Services, UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library.

In any case, Laurent-Richard owned the painting as of 1880, when he lent it to the Palais de l’industrie, Paris, in September; see Rager Ballu, Catalogue des œuvres de Th. Couture exposées au Palais de l’industrie, exh. cat. (Paris: A. Quantin, 1880), 51.

[3] Although it is unclear if the painting was still in Laurent-Richard’s collection at his death, his daughter Augustine-Victorine inherited the rest of his art collection. She and her husband Jean-Martin were art collectors, and Jean-Martin was a renowned Professor of Neurology. Considering the subject matter, it is possible that the Charcots kept the work after Laurent-Richard’s death in 1886.

[4] See Georges Bertauts-Couture, Thomas Couture (1815–1879): sa vie, son œuvre, son caractère, ses idées, sa méthode (Paris: Le Garrec, 1932), 100. No further record of this painting in Gould’s collection has been found. While it is possible that Gould’s eldest daughter Helen Miller Gould (1868–1938) inherited the painting along with his mansion, Lyndhurst, she did not sell many of her father’s paintings. If this painting belonged to Gould, it is likely that he deaccessioned it himself before his death in 1892. See letter from Henry J. Duffy, curator at Saint-Gaudens National Historical Park, New York, to Danielle Hampton Cullen, the Nelson-Atkins, December 22, 2021, NAMA curatorial files.

[5] Marcel Jules Rougeron (1875–1954) was a paintings restorer, art dealer, and collector in New York. See stenciled label on verso of painting lower left corner, in shape of palette: PICTURE RESTORATION / ROUGERON / NEW YORK / 94 PARK AVENUE.

The Couture painting, Pierrot in Criminal Court, now in the Cleveland Museum of Art, shares some of the same provenance: Jay Gould, the 1926 Astor sale, and Rougeron.

[6] The museum considered purchasing the painting as early as March 1, 1932, although it is unclear if, at this time, the painting was part of the Van Diest Gallery’s stock, or part of Rougeron’s collection with J.M. Hardy acting as an intermediary in this transaction. If the latter, Van Diest had the painting for a very short time, since it was purchased by the Nelson-Atkins on April 5; see letter from Harold Woodbury Parsons to J. C. Nichols, March 1, 1932, NAMA curatorial files.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Thomas Couture, The Illness of Pierrot, 1867–1868,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.508.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Thomas Couture, The Illness of Pierrot, 1867–1868,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.508.4033.

Thomas Couture, The Illness of Pierrot, date unknown, black, white, and red chalk on blue paper, 18 3/8 x 24 1/8 in. (46.7 x 61.3 cm), Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, MA, 1943.793.

Thomas Couture, The Duel after the Masked Ball, date unknown, 28 1/8 x 35 5/8 in. (71.5 x 90.5 cm), private collection, Houston, Texas.

Thomas Couture, Supper at the Maison d’Or, 1855, oil on canvas, 47 1/4 x 89 3/4 in. (120 x 228 cm), Vancouver Art Gallery, British Columbia, VAG 31.101.

Thomas Couture, Pierrot the Politician, 1857, oil on canvas, 44 1/2 x 57 1/2 in. (113 x 146.1 cm), Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, 71.2064.

Thomas Couture, Harlequin and Pierrot, ca. 1857, oil on canvas, 4 5/8 x 6 1/8 in. (11.9 x 15.5 cm), The Wallace Collection, London, P288.

Thomas Couture, The Duel after the Masked Ball, 1857, oil on canvas, 9 9/16 x 12 3/4 in. (24.3 x 32.5 cm), The Wallace Collection, London, P370.

Thomas Couture, The Marriage of Harlequin, about 1860, oil on canvas, 38 3/8 x 51 1/8 in. (97.5 x 130 cm), Musée d’Orsay, Paris, sans n° d’inventaire-43.

Thomas Couture, Sponsorship, ca. 1860–1869, oil on canvas, 29 x 36 3/8 in. (73.5 x 92.5 cm), Musée d’Art et d’Archéologie de Senlis, France, A.2002.5.1.

Thomas Couture, Pierrot in Criminal Court, ca. 1864–1870, oil on wood panel, 12 11/16 x 15 7/16 in. (32.2 x 39.2 cm), The Cleveland Museum of Art, 1980.250.

Reproductions

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Thomas Couture, The Illness of Pierrot, 1867–1868,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.508.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Thomas Couture, The Illness of Pierrot, 1867–1868,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.508.4033.

Eugène André Champollion (1848–1901), after Thomas Couture, Sick Pierrot, ca. 1878, etching, 5 1/2 x 6 1/8 in. (14 x 15.6 cm), illustrated in Catalogue de tableaux modernes et de tableaux anciens composant la collection Laurent-Richard (Paris: Hôtel Drouot, May 23–25, 1878), 10.

Preparatory Works

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Thomas Couture, The Illness of Pierrot, 1867–1868,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.508.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Thomas Couture, The Illness of Pierrot, 1867–1868,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.508.4033.

Thomas Couture, Study of a Man’s Head, date unknown, black and white chalks on blue paper, 19 1/4 x 12 3/4 in. (48.9 x 32.23 cm), illustrated in Importants dessins et tableaux anciens (Monte Carlo, Monaco: Sotheby’s, December 5 –6, 1991), unpaginated, (repro.).

Thomas Couture, Study for Pierrot Malade, date unknown, black chalk on paper, 8 1/2 x 11 3/8 in. (21.5 x 29 cm), illustrated in Tableaux et dessins des XVIIIe et XXe siècles (Paris: Hôtel Drouot, November 23, 1970), unpaginated.

Thomas Couture, Pierrot Ill, between 1857 and 1860, graphite on paper, 18 1/4 x 23 7/8 in. (46.5 x 60.5 cm), Musée d’Art et d’Archéologie de Senlis, France, A.00.5.699.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Thomas Couture, The Illness of Pierrot, 1867–1868,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.508.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Thomas Couture, The Illness of Pierrot, 1867–1868,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.508.4033.

Œuvres de Th. Couture, Palais de l’industrie, Paris, September 1880, no. 280, as Pierrot malade.

Great Stories in Art, Denver Art Museum, February 13–March 27, 1966, hors cat.

Couture: Paintings and Drawings in American Collections, University of Maryland Art Gallery, College Park, February 5–March 15, 1970, no. 24, as The Illness of Pierrot.

Reality, Fantasy, and Flesh: Tradition in Nineteenth Century Art, University of Kentucky Art Gallery, Lexington, October 28–November 18, 1973, no. 21, as The Illness of Pierrot.

Paris—New York: A Continuing Romance; Wildenstein Centenary Exhibition, for the Benefit of the New York Public Library, Wildenstein and Co., New York, November 3–December 17, 1977, no. 61, as The Illness of Pierrot.

Genre, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, April 5–May 15, 1983, no. 35, as The Illness of Pierrot.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Thomas Couture, The Illness of Pierrot, 1867–1868,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.508.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Thomas Couture, The Illness of Pierrot, 1867–1868,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.508.4033.

advertisement, La Chronique des arts et de la curiosité, no. 13 (March 30, 1878): 101.

advertisement, La Chronique des arts et de la curiosité, no. 16 (April 20, 1878): 127.

Alfred de Lostalot, “La Collection Laurent Richard,” Gazette des Beaux-Arts: Courrier Européen de l’Art et de la Curiosité 17, no. 251 (May 1, 1878): 471, as Pierrot malade.

advertisement, La Chronique des arts et de la curiosité, no. 18 (May 4, 1878): 143.

advertisement, La Chronique des arts et de la curiosité, no. 19 (May 11, 1878): 150

advertisement, La Chronique des arts et de la curiosité, no. 20 (May 18, 1878): 160.

Possibly Paul Lefort, “La collection de M. Laurent-Richard,” L’Evénement (May 21, 1878).

“Nouvelles Diverses,” Journal des débats politiques et littéraires (May 26, 1878): unpaginated, as Pierrot malade.

“Vente de la collection Laurent Richard,” La Liberté (May 26, 1878): unpaginated, as Pierrot Malade.

Un passant, “Les on-dit,” Le Rappel, no. 2999 (May 27, 1878): 2, as Pierrot malade.

“Informations et faits,” Journal officiel de la République française, no. 145 (May 27, 1878): 5848, as Pierrot malade.

“Mouvement des Arts,” La Chronique des arts et de la curiosité, no. 22 (June 1, 1878): 171, as Pierrot malade.

Lucy H. Hooper, “The Gallery of M. Laurent-Richard,” Art Journal 4 (1878): 188, as The Sick Pierrot.

J[oseph] Brunard, Le Recueil de l’art et de la Curiosité (Paris: Delamotte Fils et Cie, Libraires-Éditeurs, 1878), 194, as Pierrot malade.

Catalogue de tableaux modernes et de tableaux anciens composant la collection Laurent-Richard (Paris: Hôtel Drouot, May 23, 1878), xviii, 10, (repro.), as Pierrot malade.

A. de L., “Nécrologie,” La Chronique des arts et de la curiosité, no. 14 (April 5, 1879): 112, as Pierrot malade.

J[oseph] Brunard, Le guide des commissaires-priseurs et autres officiers vendeurs de meubles (Paris: Loones, Librarie, Successeur de J. Renouard, 1879), 179, as Pierrot malade.

Victor Champier, L’Année Artistique (Paris: A. Quantin, 1879), 336, as Pierrot malade.

Marcello, “L’Exposition de Thomas Couture,” Le Télégraphe (September 5, 1880), as Pierrot malade.

Lucy H. Hooper, “The Couture Exhibition,” Art Journal 6 (1880): 347.

Rager Ballu, Catalogue des œuvres de Th. Couture exposées au Palais de l’industrie, exh. cat. (Paris: A. Quantin, 1880), 51, as Pierrot malade.

Duranty, “Thomas Couture,” La Chronique des arts et de la curiosité, no. 29 (September 4, 1880): 234, as Pierrot malade.

Paul de Charry, “Beaux-Arts: Thomas Couture,” Le Pays, no. 264 (September 20, 1880): unpaginated, as Pierrot malade.

“Dernières Acquisitions: Les Beaux-Arts Illustrés,” Feuilleton du Journal Général de l’Imprimerie et de la Librairie, no. 40 (October 2, 1880): 1740, as Pierrot Malade.

Earl Shinn, The Art Treasures of America being the Choicest Works of Art in the Public and Private Collections of North America (Paris: G. Barrie, 1881), II:114.

Hippolyte Mireur, Dictionnaire des Ventes d’Art en France et à l’Étranger pendant les XVIIIe et XIXe Siècles (Paris: Maisons d’Éditions d’Œuvres Artistiques, 1902), 1:208, as Pierrot malade.

Armand Dayot, Exposition des œuvres de Thomas Couture, exh. cat. (Paris: Galerie Levesque, 1913), 9, as Pierrot Malade.

Paintings, furnishings and architectural fittings of the Astor residence, 840 Fifth Avenue, New York: paintings of the XIX century French school, furniture, tapestries and objects of art, carved wood wall paneling, painted insets and ceilings, bronzes and ironwork (New York: American Art Association, April 20, 1926), 111, as Pierrot Malade.

M[inna] K. P[owell], “A New Nelson Group: Paintings and Drawings Are Added to Gallery,” Kansas City Star 52, no. 206 (April 10, 1932): 11A.

M[inna] K. P[owell], “Art: Mr. Parsons Will Be Heard Thursday Night on ‘The Italian Renaissance;’ What Is to Be Seen in the Group of Recently Acquired Paintings for the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art Was Told the Hospitality Committee Yesterday by Him,” Kansas City Times 95, no. 88 (April 12, 1932): 10.

Georges Bertauts-Couture, Thomas Couture (1815–1879): Sa vie, son œuvre, son caractère, ses idées, sa méthode (Paris: Le Garrec, 1932), 40, 84, 100, (repro.), as Pierrot malade.

Eugené Bouvy, “Au Lendemain de L’exposition Manet: Thomas Couture,” L’Amateur d’estampes, no. 5 (October 1932): 159, as Pierrot malade.

The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Handbook of the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1933), 49, (repro.), as The Illness of Pierrot.

Thomas Carr Howe, “Kansas City Has Fine Art Museum: Nelson Gallery Ranks with the Best,” [unknown newspaper] (ca. December 1933), clipping, scrapbook, NAMA Archives, vol. 5, p. 6.

“Nelson Gallery of Art Special Number,” Art Digest 8, no. 5 (December 1, 1933): 21, as The Illness of Pierrot.

“The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art, Kansas City Special Number,” Art News 32, no. 10 (December 9, 1933): 30.

A. J. Philpott, “Kansas City Now in Art Center Class: Nelson Gallery, Just Opened, Contains Remarkable Collection of Paintings, Both Foreign and American,” Boston Sunday Globe 125, no. 14 (January 14, 1934): 16.

M[inna] K. P[owell], “Gallery’s First Anniversary To Be Celebrated Next Week,” Kansas City Star 55, no. 80 (December 6, 1934): 10, as The Illness of Pierrot.

“Little Hands in Art,” Kansas City Star 54, no. 331 (August 14, 1934): 9, as The Illness of Pierrot.

“Marionette Shows Thursday,” Kansas City Star 54, no. 345 (August 28, 1934): 2, as The Illness of Pierrot.

“Portrait by Manet Chosen as Week’s Nelson Gallery Masterpiece,” Kansas City Journal-Post 82, no. 126 (January 26, 1936): 2-B, as Illness of Pierrot.

“One of the most important purchases,” Musical Bulletin (March 1936): 78, as The Death of Pierrot.

The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, The William Rockhill Nelson Collection, 2nd ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1941), 168, as The Illness of Pierrot.

Aimée Crane, ed., A Gallery of Great Paintings (New York: Crown, 1944), 32, (repro.), as The Illness of Pierrot.

Georges Bertauts-Couture, “Thomas Couture: sa technique et son influence sur la peinture françáise de la seconde moitié du XIXe siècle,” Etudes d’art, Musée National des Beaux-Arts d’Alger, nos. 11–12 (1955–1956): 204, Pierrot malade.

Ross E. Taggart, ed., Handbook of the Collections in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 4th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1959), 260, as Illness of Pierrot.

Albert Boime, “À La Mode and Haute Couture,” Burlington Magazine 112, no. 810 (September 1970): 646–47, (repro.), as The Illness of Pierrot.

Jane van Nimmen, Thomas Couture: Paintings and Drawings in American Collections (College Park, MD: University of Maryland, 1970), 57, (repro.), as The Illness of Pierrot.

Albert Boime, “Newman, Ryder, Couture and Hero-Worship in Art History,” American Art Journal 3, no. 2 (Autumn 1971): 20n44, as The Illness of Pierrot.

Albert Boime et al., Thomas Couture, 1815–79: Drawings and Some Oil Sketches, exh. cat. (New York: Shepherd Gallery, 1971), unpaginated, erroneously as The Illness of Harlequin.

Reality, Fantasy and Flesh: Traditions in Nineteenth Century Art, exh. cat. (Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky Art Gallery, 1973), 13, 17, (repro.), as The Illness of Pierrot.

Sarah Lansdell, “Review of Exhibition Reality, Fantasy, and Flesh,” Courier-Journal and Times 237, no. 127 (November 4, 1973): 19, (repro.), as The Illness of Pierrot.

Ross E. Taggart and George L. McKenna, eds., Handbook of the Collections in The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Kansas City, Missouri, vol. 1, Art of the Occident, 5th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1973), 257, as The Illness of Pierrot.

Paris—New York: A Continuing Romance; Wildenstein Centenary Exhibition, for the Benefit of the New York Public Library, exh. cat. (New York: Wildenstein, 1977), 56, (repro.), as The Illness of Pierrot.

Pierre Vaisse, “Couture et le Second Empire,” Revue de l’art, no. 37 (1977): 4748, 53, 64n53, (repro.), as Pierrot malade.

Robert Henning et al., Enrollment of the Volunteers: Thomas Couture and the Painting of History, exh. cat. (Springfield, MA: Museum of Fine Arts, 1980), 78, as Pierrot Sick.

Albert Boime, Thomas Couture and the Eclectic Vision (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1980), 301, 318, 321, 323–26, 459, (repro.), as The Illness of Pierrot.

Ross E. Taggart and Laurence Sickman, Genre, exh. cat. (Kansas City: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1983), 15, 26, (repro.), as The Illness of Pierrot.

Helen O. Borowitz, “Painted Smiles: Sad Clowns in French Art and Literature,” Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 71, no. 1 (January 1984): 23, 31.

Tableaux anciens, tableaux et dessins du XIXe siècle (Monte Carlo, Monaco: Sotheby’s, June 20, 1987), unpaginated.

Dessins anciens et du XIXe siècle (Monte Carlo, Monaco: Sotheby’s, December 2, 1988), 59.

Possibly Marie-Jeanne Grosset-Clergeau, Catalogue raisonné des peintures de Thomas Couture demeurées dans les collections publiques en France (Lille: Atelier national de reproduction des thèses, 1988).

L’Enrôlement des volontaires de 1792, Thomas Couture (1815–1879): Les artistes au service de la patrie en danger (Beauvais: Musee departemental de l’Oise, 1989), 94, as Pierrot malade.

Peintures, Aquarelles, Dessins: 1755–1891, exh. cat. (Paris: Jean François and Phillippe Heim, 1990), 54, as Pierrot malade.

Loretta S. Loftus, “The Cover,” Journal of American Medical Association 266, no. 9 (September 4, 1991): 1174, (repro.), as The Illness of Pierrot.

“This and That,” Kansas City Star 111, no. 363 (September 15, 1991): K8, as The Illness of Pierrot.

French Drawings, 1770–1880, exh. cat. (New York: W. M. Brady, 1992), unpaginated, as La Maladie de Pierrot.

Thomas Couture: Dessins (1859–1869), exh. cat. (Senlis: Musée d’art, 1993), 15, as Pierrot malade.

Roger Ward and Patricia J. Fidler, eds., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collection (New York: Hudson Hills Press, in association with Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1993), 204, (repro.), as The Illness of Pierrot.

Christine Debrie et al., Dessins français du XIXe siècle dans les musées de Picardie, exh. cat. (Abbeville: Musée Boucher de Perthes, 1994), 74–75, 80-81, as Pierrot malade.

Éric Deschodt and Jacques Boulay, D’un musée l’autre en Picardie (Paris: Éditions du Regard, 1996), 169.

Jules Defossé, Thomas Couture: Souper à la Maison d’Or, exh. cat. (Senlis: Musée de l’Hôtel de Vermandois 1998), 45.

Louise d’Argencourt, European Paintings of the 19th Century (Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art, 1999), 1:173, 176n3, as Sick Pierrot.

Amal Asfour, Champfleury: Meaning in the Popular Arts in Nineteenth-Century France (Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2001), 148, 158n109, 219, (repro.), as The Illness of Pierrot.

Le XIXe siècle, exh. cat. (Paris: Talabardon et Gautier, 2001), unpaginated, as Pierrot malade.

Bénédicte Pradié-Ottinger, “Pour une redécouverte de l’oeuvre de Thomas Couture portraitiste: à propos de la récente acquisition du portrait de ‘La baronne d’Astier de la Vigerie’ par le Musée d’Art et d’Archéologie de Senlis,” Revue Du Louvre (April 2, 2001): 66.

Alan E. H. Emery and Marcia L. H. Emery, Medicine and Art (London: Royal Society of Medicine Press, 2003), 54–55, (repro.), as The Illness of Pierrot.

Bénédicte Ottinger, “Thomas Couture et l’Amérique,” 48/14: La Revue du Musée d’Orsay, no. 26 (Spring 2008): 32, 38n2, 39n30, as Pierrot malade.

Deborah Emont Scott, ed., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collection, 7th ed. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2008), 115, (repro.), as The Illness of Pierrot.

Bénédicte Ottinger, Les œuvres d’un peintre senlisien aux États-Unis: Thomas Couture, 1815–1879 (Senlis: Société d’histoire et d’archéologie de Senlis, 2008), 129, 134, 140, as Pierrot malade.

Bénédicte Ottinger and Caroline Joubert, Damoclès: Thomas Couture (Caen: Musée des beaux-arts de Caen, 2009), 9, as Pierrot malade.

Olivia Voisin and Thierry Cazaux, Thomas Couture: Romantique malgré lui, exh. cat. (Paris: Gourcuff-Gradenigo, 2015), 13, 60, 123, 129, as La Maladie de Pierrot.

Catherine Futter et al., Bloch Galleries: Highlights from the Collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2016), 38, (repro.), as The Illness of Pierrot.

Jennifer Forrest, Decadent Aesthetics and the Acrobat in French Fin de Siècle (New York: Routledge, 2020), 44, 64n2, 66n12, Pierrot Malade.

Lisa Hecht, Aubrey Beardsleys Rezeption des 18. Jahrhunderts als Ausdruck von Selbstinszenierung und (Selbst)-Parodie (Köln: Böhlau Verlag, 2020), 179–81, 334, as Pierrot malade.