![]()

Edgar Degas, Rehearsal of the Ballet, ca. 1876

| Artist | Edgar Degas, French, 1834–1917 |

| Title | Rehearsal of the Ballet |

| Object Date | ca. 1876 |

| Alternate and Variant Titles | Répétition de ballet; A Ballet; Ballet Rehearsal |

| Medium | Gouache and pastel over monotype on cream laid paper |

| Dimensions (Unframed) | Plate: 22 1/4 x 27 1/2 in. (56.5 x 70 cm) Sheet (irregular): 23 13/16 x 29 3/16 in. (60.5 x 74.2 cm), |

| Signature | Signed upper right in black pastel: Degas Signed upper right, partially obscured, in yellow pastel: Degas |

| Credit Line | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Purchase: The Kenneth A. and Helen F. Spencer Foundation Acquisition Fund, F73-30 |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “Edgar Degas, Rehearsal of the Ballet, ca. 1876,” catalogue entry in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.614.5407

MLA:

Marcereau DeGalan, Aimee. “Edgar Degas, Rehearsal of the Ballet, ca. 1876,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.614.5407.

Edgar Degas’s (1834–1917) unusual mixed-media composition shows a rehearsal for a ballet in an interior stage setting. At the left, three dancers wait in the wings near the celebrated dance master Jules Perrot (1810–1892) while two others rehearse onstage. An abonnéabonné: A season ticket subscriber, in this case at the ballet or opera. stands at the far right, almost completely obscuring one of the dancers, whose disembodied leg emerges from behind him. With the exception of the central dancer en pointeen pointe: A term used in ballet to mean “on the tips of the toes.”, nearly all the figures’ legs and some of their bodies are truncated. One dancer at the far left adjusts her costume while another, with her back toward the viewer, bends over to tie her ballet slipper. The overall effect of the composition is as if Degas has captured a moment in time; yet, as his friend Paul Valéry once noted, Degas’s work “was the result of a limitless number of sketches—and of a whole series of operations.”1Paul Valéry, Degas, Manet, Morisot, trans. David Paul (Pantheon Books, New York, 1960), 50. Emphasis original. Indeed, the Nelson-Atkins painting is no exception.

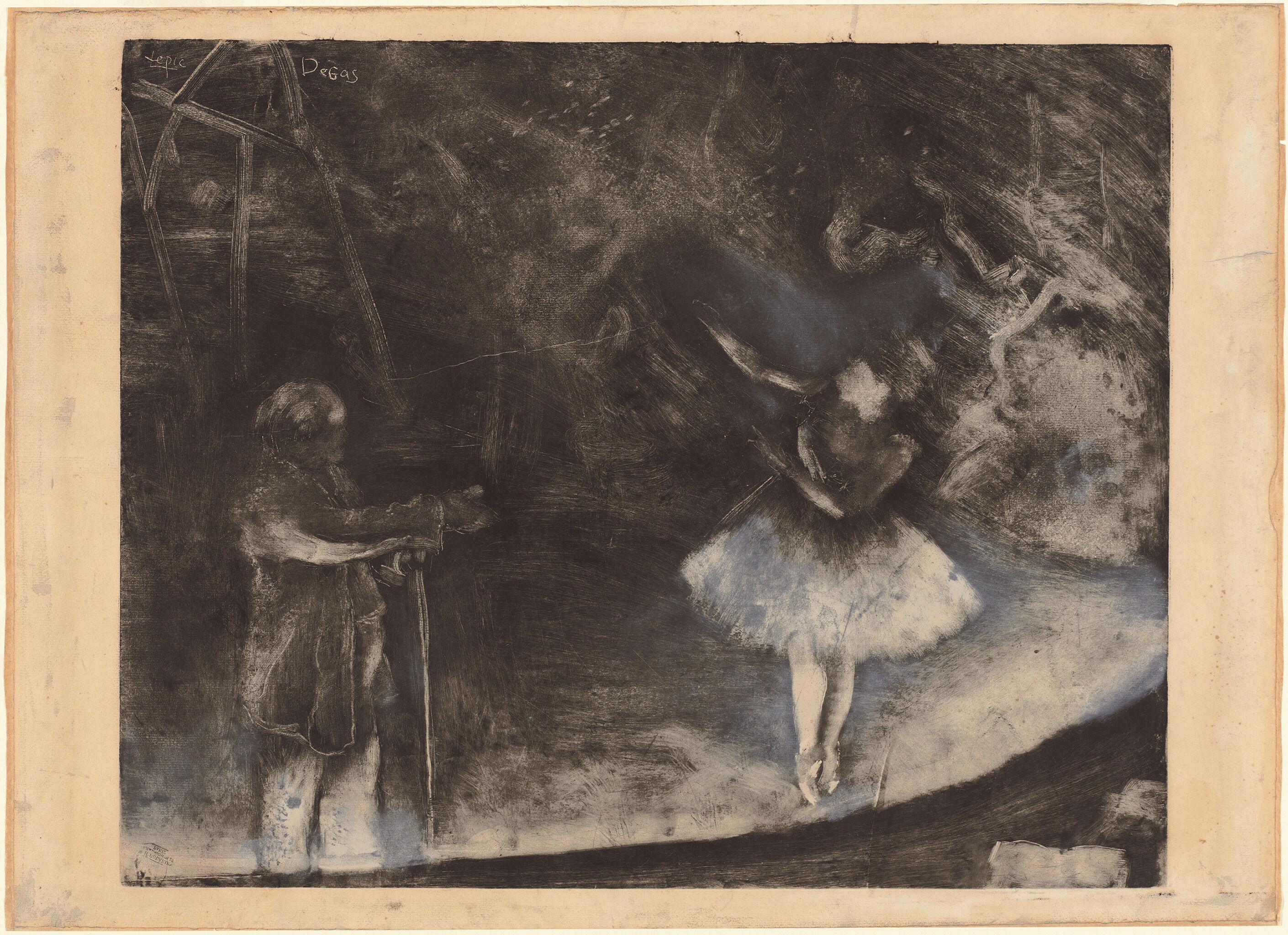

The ballerina en pointe and Perrot appear together (in reverse) for the first time in the National Gallery’s The Ballet Master, a dark-field monotypedark-field monotype: A subtractive image creation process where the printing matrix (the nonporous surface onto which the ink is applied) is entirely covered with ink, and the design is created by removing the ink. See also monotype. (Fig. 2). This was probably Degas’s first and largest monotype, executed with the help of the artist’s friend and mentor, Ludovic-Napoléon Lepic (1839–1889). The Nelson-Atkins work began as a second impression, or cognatecognate: In monotypes, cognates are multiple prints pulled from an inked image on a plate. The first print is usually the strongest, and the image quality reduces with each subsequent pull. It is usually possible to pull only two or three prints before the image becomes unreadable. See also monotype., which Degas alone completely worked over in brilliant strokes of pastel and colored gouache, using the monotype print as a point of departure.2Although there has been considerable debate over the order of the National Gallery (NGA) and Nelson-Atkins compositions, this author follows the early opinion (1968) of Eugenia Parry Janis, who argued that Degas would often work up the second, less inkier pull of a monotype in pastel and gouache. See her pioneering study, Degas Monotypes: Essay, Catalogue and Checklist, exh. cat. (Cambridge, MA: Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, 1968), xviii and cat. no. 1 (unpaginated). This opinion has been substantiated further through recent conservation examinations of both the NGA Ballet Master and the Nelson-Atkins Rehearsal of the Ballet, done in preparation for this publication. I am extremely grateful to NGA paper conservators Kimberly Schenck and Michelle Facini and to Nelson-Atkins paper conservator Rachel Freeman for sharing their learned insight on our respective pictures, resulting in a mutual agreement on this point. For alternative opinions, see Richard Kendall, “Degas and Difficulty,” in “Degas,” special issue, Facture: Conservation, Science, Art History 3 (2017): 14; and Jane R. Becker, “Catalogue Entry,” The Rehearsal of the Ballet Onstage, Metropolitan Museum of Art website, 2016, accessed October 19, 2020, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/436155. (As argued in the accompanying technical essay, there may be additional media present.) This hybrid technique, as scholars have argued, had no precedent in the artist’s oeuvre, and became central to his creative activity at this early moment in his career.3See Richard Kendall, “An Anarchist in Art: Degas and the Monotype,” in Jodi Hauptman, Degas: A Strange New Beauty, exh. cat. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2016), 24. Lepic, an experimental printmaker, introduced Degas to the monotype process. A master at inking his own plates, Lepic probably performed the same role for Degas, inking the examples at the National Gallery and the Nelson-Atkins; the artists’ dual signatures on the monotype plate serve as evidence of this important partnership.4Janis, Degas Monotypes, xviii. Lepic may also have let Degas use one of his own plates for the Nelson-Atkins and National Gallery monotypes, since Lepic often worked on a larger scale than Degas did in this medium.5I am grateful to Kimberly Schenck for suggesting the possibility that this plate could be one of Lepic’s, based on its size. Lepic often worked on large plates to create his etchings and monotypes. One example is The Mill Fire from the series Views from the Banks of the Scheldt (ca. 1870–1876, etching with variable inking on paper, plate: 13 1/2 ×29 5/16 in. [34.3 × 74.4 cm]; sheet: 17 11/16 × 31 7/8 in. [45 × 81 cm], The Baltimore Museum of Art, Garrett Collection). The Nelson-Atkins/NGA monotype is Degas’s largest monotype, although The Fireside (ca. 1876–1877, monotype in black ink on white heavy laid paper, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), is nearly as large, at a plate size of 16 3/4 x 23 1/16 in.

Rehearsal of the Ballet is much more ambitious in scope than its monotype starting point, The Ballet Master.6For additional changes between the NGA monotype and its Kansas City cognate, see the accompanying technical essay by Rachel Freeman. As Eugenia Parry Janis first argued, monotype gave Degas the opportunity to experiment with compositional elements he previously realized through preparatory drawings alone.7See Janis, Degas Monotypes, xviii and cat. 1. See also Richard Kendall, “An Anarchist in Art: Degas and the Monotype,” in Jodi Hauptman, Degas: A Strange New Beauty, exh. cat. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2016), 24. In the Kansas City picture, the view is slightly more elevated, and Degas adds in three additional ballerinas around the figure of Perrot at left, and two additional figures—an abonné and another dancer—to the right of the dancer en pointe. These elements, in particular the relationship between the central figure en pointe and her two male onlookers, arguably add a psychological dimension to a painting, which is already charged with an element of portraiture with the inclusion of Perrot.8George T. M. Shackelford uses this logic in his argument about Perrot’s figure in Degas’s The Dance Class (between 1873 and 1876, oil on canvas, 85 x 75 cm, Musée d’Orsay) in Degas: The Dancers, exh. cat. (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1984), 52.

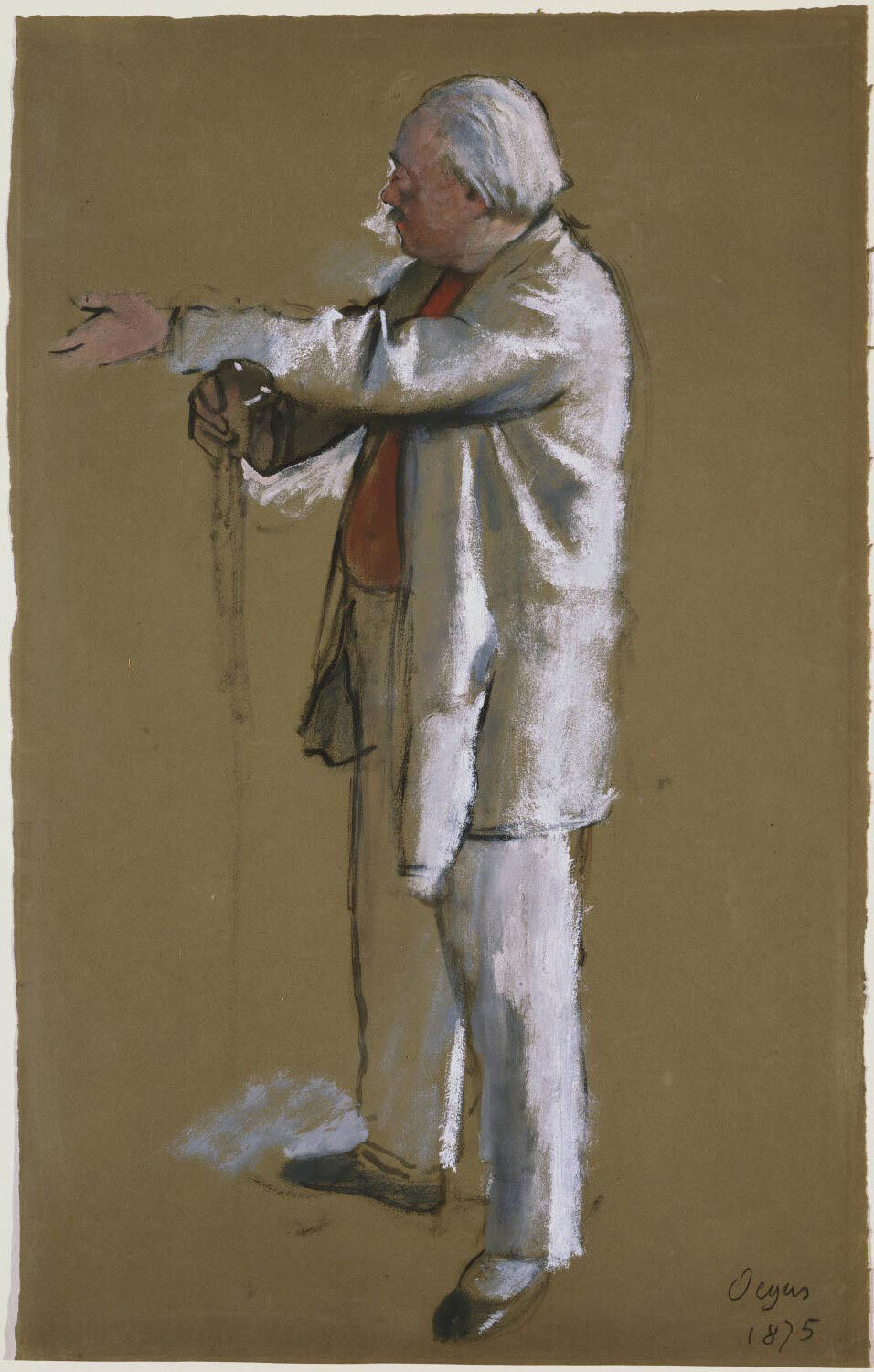

Jules Perrot was an acclaimed dancer, choreographer, and ballet partner to Marie Taglioni, whose method of dancing en pointe became the standard all ballerinas strived to emulate.9“Filippo Taglioni,” Encyclopædia Britannica, published February 7, 2020, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Filippo-Taglioni. Degas met Perrot possibly around 1873, long after the latter retired, but it is clear, based on the number of images Degas made of the aging star, that he admired him greatly.10Their meeting is based on the proposed date of the Musée d’Orsay composition The Dance Class (between 1873 and 1876, oil on canvas, 33 7/16 x 29 1/2 in. [85 x 75 cm]) and Portrait of the Dancer Jules Perrot (Fig. 1). While Degas probably intended to base Perrot’s figure in Rehearsal of the Ballet directly on his earlier drawings (see Fig. 1), it was only in the course of working on the National Gallery monoprint that what was going to be a replica became a variant. Perhaps most significantly, Degas shifted the direction of Perrot’s gaze from profil perduprofil perdu: French for "lost profile." The artist shows their subject without the profile of the head being visible. A profile of a human head that is not seen directly from the side, but more from the back of the head., or “lost profile,” to full profile, focusing the ballet master’s attention more squarely on the dancer at center stage, who assumes the position his former dance partner Taglioni made famous.11The Philadelphia drawing, dated 1875, shows Perrot’s head turned slightly more in profile than the Fitzwilliam drawing and could represent an evolution in Degas’s thinking, ultimately shifting it to full profile in the Nelson-Atkins composition. Degas made several other subtle changes to Perrot’s figure in the Nelson-Atkins composition, notably in the cut of the dance master’s coat, which in the Nelson-Atkins composition, rounds down from his lapels hiding more of the aging dance master’s midriff, as opposed to falling straight down as seen in the NGA monotype. For an image of these changes, see Rachel Freeman’s accompanying technical essay.

The abonné focuses his attention acutely on the dancer en pointe. Abonnés, or male subscribers to the ballet, were members of high society who enjoyed privileged access to the backstage spaces of the theater and to the dancers who occupied those spaces. Caricatured by Honoré Daumier (1806–1879) and many others during the period, abonnés frequently appear as tall, dark, and slender figures who lurk backstage to engage with the young ballerinas on a variety of levels.19See, for example, Honoré Daumier, The Singer’s Mother, 1856, lithograph, 8 x 9 1/2 in. (20.5 x 23.5 cm), private collection. Degas heightens the stock characteristics of the abonné even further in the Nelson-Atkins composition, showing him towering over the other figures. Abonnés found in other Degas compositions from the period appear more realistically scaled, making the physical disparity of the mustachioed gentleman in the Nelson-Atkins composition seem all the more noteworthy.20See Edgar Degas, Dancers Backstage, 1876/1883, oil on canvas, 9 1/2 x 7 3/8 in. (24.2 x 18.8 cm) National Gallery, Washington, DC, https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.52169.html.

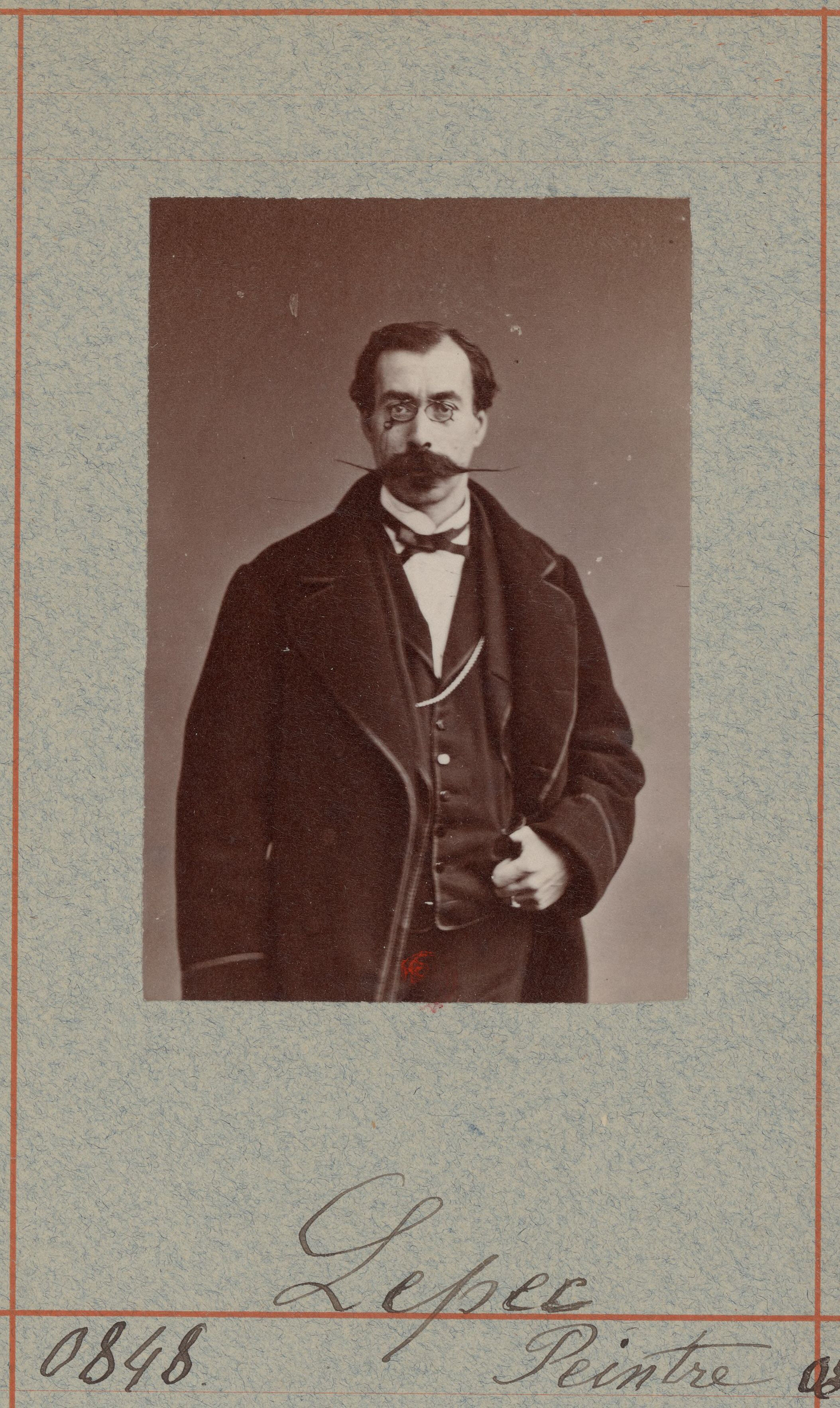

Around 1876, when Degas collaborated with Lepic on the National Gallery monotype,

Lepic was also busy on several other projects related to the Opéra, one of which

included Sanlaville. In 1876, a small book entitled L’Opéra: Eaux-Fortes et

Quatrains, par un Abonné was dedicated by its anonymous author to Lepic.23L’Opéra: Eaux-Fortes et Quatrains, par un Abonné (Paris: Librairie des bibliophiles, 1876).

It includes a portrait of Sanlaville, among other figures from the stage, and a

pair of frontispiece etchings by Lepic entitled Chant and Danse.24The anonymous author was most likely Henry de Fleurigny (pseudonym of Henri Micaud [1846–1916]), as cited in Buchanan, “Edgar Degas and Ludovic Lepic,” 91, 118n227. For another image of Sanlaville, see Artistes de l’Opéra: Recueil de portraits, ca. 1876, Bibliothèque nationale de France, https://images.bnf.fr/#/detail/344436/48.

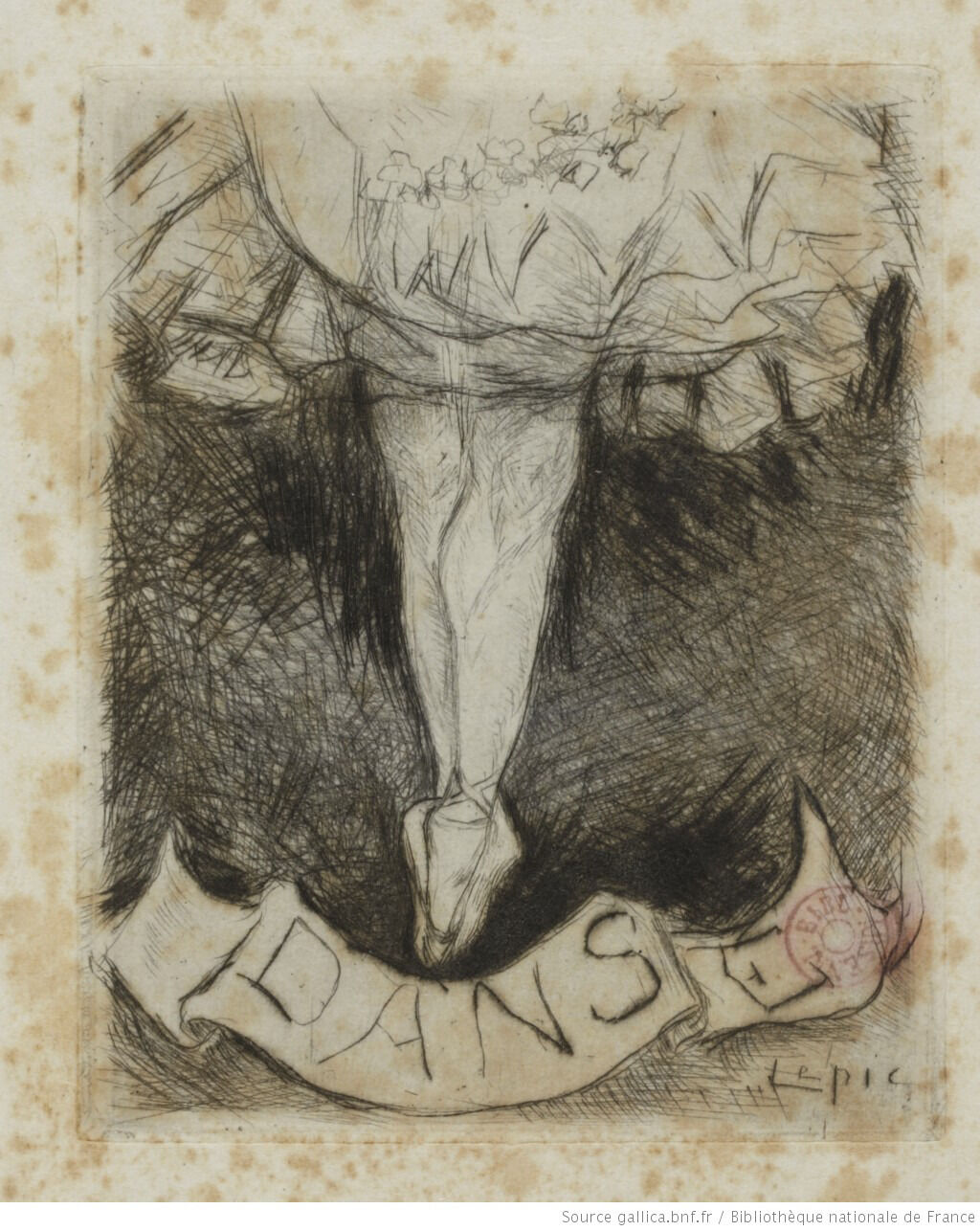

With the exception of the National Gallery monotype on which Lepic and Degas

collaborated, the etching Danse (Fig. 6) represents Lepic’s only other dance

subject.25Buchanan, “Edgar Degas and Ludovic Lepic,” 92. It shows a pair of dancer’s legs en

pointe, from just below the waist, in a multilayered and ruffled tutu not unlike

the one in which Sanlaville appears in the aforementioned carte de visite. Was

Lepic offering a nod to Degas and Sanlaville by replicating in his print the en

pointe pose of the dancer in Degas’s monoprint?

Whether or not Lepic and Sanlaville are portrayed in the Nelson-Atkins composition, their association with Degas was close. Lepic appears in at least eleven works by Degas between 1859 and his death in 1889, making him the only individual except members of Degas’s immediate family to be portrayed so frequently.26Buchanan, “Edgar Degas and Ludovic Lepic,” 32. Sanlaville, for her part, appears in at least three compositions by Degas.27Degas represented Sanlaville as Zail, standing behind the title figure in Mlle Fiocre in the Ballet “La Source” (1867–1868, oil on canvas, 51 1/2 x 57 1/8 in. [130.8 x 145.1 cm], Brooklyn Museum of Art, 21.111). Sanlaville also participated in a sketching session in Degas’s studio in the early 1880s, and later she figured in at least one portrait: Mlle Sanlaville (or Mlle S., Première Danseuse à l’Opéra), ca. 1886, pastel on paper, 15 3/8 x 10 5/8 in. (39 x 27 cm), private collection. There are no known records of Degas having identified his models during his lifetime, so one is left to ponder whether the Nelson-Atkins composition could count as additional representations of these two individuals—intimates of Degas, and of each other.

Due in part to the elusive identity of Degas’s subjects, it can be difficult to assign specific dates to his dancer compositions completed between 1872 and 1876. There are no dated oils from this time period, and only a handful of his pictures in other media include a date.28See Ronald Pickvance, “Degas’s Dancers: 1872–1876,” Burlington Magazine 105, no. 723 (June 1963): 256–67, esp. 264n71, for his proposed dating of the Nelson-Atkins composition to 1875 on the basis of a presumed acquisition date by Louisine Elder. Scholars like Theodore Reff have also shown that Degas inadvertently misdated drawings on occasion. See Theodore Reff, “New Light on Degas’s Copies,” Burlington Magazine 106, no. 735 (June 1964): 250–59. Historically, the dating of the Nelson-Atkins composition has ranged from 1874 to 1877. While many of the studies from which its composition derives stylistically date to 1873, it was most likely completed after the three Rehearsal pictures (the camaïeu painting at the Musée d’Orsay and the pastel and oil at The Metropolitan Museum) that are dated circa 1874. The Nelson-Atkins picture shows an increased freedom in handling, a bolder approach to the poses of the dancers, and a more dramatically composed composition, with a greater use of foreshortening in the shallow space of the stage. Degas also uses the bold framing device of the dark-suited abonné along the right edge of the composition, an element he employs in at least three later compositions dated from 1876 to 1883; this further supports a slightly later date for the Nelson-Atkins composition.29See Edgar Degas, Pauline and Virginie Conversing with Admirers, ca. 1876–80, illustration for La famille Cardinal, monotype on paper, sheet: 11 3/8 x 7 1/2 in. (28.7 x 19.1 cm), Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University; and Edgar Degas, Dancers Backstage (see n. 19). The circa 1877 date of the Getty study of Perrot, however, acts as a terminus ante quem (“no later than”) for the Nelson-Atkins composition. The Getty drawing was almost certainly done after the Kansas City picture, considering that it replicates not only Perrot’s right-facing orientation but also his closed stance and his head in full profile. This, then, argues for a date of about 1876 for both the National Gallery monotype and the Nelson-Atkins composition.

There is much debate about precisely where and when Louisine Elder (later Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer) acquired the painting. Some scholars suggest she bought it from a color shop in 1875 on the advice of her friend Mary Cassatt (1844–1926), during Elder’s first trip to Paris, while many others, including Jean Sutherland Boggs, believe it was purchased in 1877 during a subsequent trip to Paris.30The specific color shop is also debated. Frances Weitzenhoffer says Elder purchased the pastel in 1875, probably from Père Tanguy’s; see Weitzenhoffer, The Havemeyers: Impressionism Comes to America (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1986), 21. Susan Alyson Stein says Elder purchased the pastel in 1877, probably from Père Tanguy’s shop; see Louisine W. Havemeyer, Sixteen to Sixty: Memoirs of a Collector, ed. Susan Alyson Stein, 2nd ed. (New York: Ursus Press, 1993), 331n291. Jean Sutherland Boggs says Elder probably purchased the painting in 1877; see Boggs et al., Degas, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1988), 258. I am grateful for the exhaustive provenance and backmatter research for this painting conducted by Danielle Hampton Cullen. We know for certain that Elder owned the painting before February 1878, when she lent it to the Eleventh Annual Exhibition of the American Water Color Society exhibition in New York, making it the first Degas ever exhibited in America.31The painting belonged to Louisine Elder; however, in the exhibition catalogue, the lender is listed as G. W. Elder. These initials belonged to both Louisine’s deceased father (d. 1873), and her younger brother, George (1860–1916). See Illustrated Catalogue of the Eleventh Annual Exhibition of the American Water Color Society Held at the Galleries of the National Academy of Design, exh. cat. (New York, 1878), 14.

Notes

-

Paul Valéry, Degas, Manet, Morisot, trans. David Paul (Pantheon Books, New York, 1960), 50. Emphasis original.

-

Although there has been considerable debate over the order of the National Gallery (NGA) and Nelson-Atkins compositions, this author follows the early opinion (1968) of Eugenia Parry Janis, who argued that Degas would often work up the second, less inkier pull of a monotype in pastel and gouache. See her pioneering study, Degas Monotypes: Essay, Catalogue and Checklist, exh. cat. (Cambridge, MA: Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, 1968), xviii and cat. no. 1 (unpaginated). This opinion has been substantiated further through recent conservation examinations of both the NGA Ballet Master and the Nelson-Atkins Rehearsal of the Ballet, done in preparation for this publication. I am extremely grateful to NGA paper conservators Kimberly Schenck and Michelle Facini and to Nelson-Atkins paper conservator Rachel Freeman for sharing their learned insight on our respective pictures, resulting in a mutual agreement on this point. For alternative opinions, see Richard Kendall, “Degas and Difficulty,” in “Degas,” special issue, Facture: Conservation, Science, Art History 3 (2017): 14; and Jane R. Becker, “Catalogue Entry,” The Rehearsal of the Ballet Onstage, Metropolitan Museum of Art website, 2016, accessed October 19, 2020, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/ 436155.

-

See Richard Kendall, “An Anarchist in Art: Degas and the Monotype,” in Jodi Hauptman, Degas: A Strange New Beauty, exh. cat. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2016), 24.

-

Janis, Degas Monotypes, xviii.

-

I am grateful to Kimberly Schenck for suggesting the possibility that this plate could be one of Lepic’s, based on its size. Lepic often worked on large plates to create his etchings and monotypes. One example is The Mill Fire from the series Views from the Banks of the Scheldt (ca. 1870–1876, etching with variable inking on paper, plate: 13 1/2 × 29 5/16 in. [34.3 × 74.4 cm]; sheet: 17 11/16 × 31 7/8 in. [45 × 81 cm], The Baltimore Museum of Art, Garrett Collection). The Nelson-Atkins/NGA monotype is Degas’s largest monotype, although The Fireside (ca. 1876–1877, monotype in black ink on white heavy laid paper, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), is nearly as large, at a plate size of 16 3/4 x 23 1/16 in.

-

For additional changes between the NGA monotype and its Kansas City cognate, see the accompanying technical essay by Rachel Freeman.

-

See Janis, Degas Monotypes, xviii and cat. 1. See also Richard Kendall, “An Anarchist in Art: Degas and the Monotype,” in Jodi Hauptman, Degas: A Strange New Beauty, exh. cat. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2016), 24.

-

George T. M. Shackelford uses this logic in his argument about Perrot’s figure in Degas’s The Dance Class (between 1873 and 1876, oil on canvas, 85 x 75 cm, Musée d’Orsay) in Degas: The Dancers, exh. cat. (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1984), 52.

-

“Filippo Taglioni,” Encyclopædia Britannica, published February 7, 2020, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Filippo-Taglioni.

-

Their meeting is based on the proposed date of the Musée d’Orsay composition The Dance Class (between 1873 and 1876, oil on canvas, 33 7/16 x 29 1/2 in. [85 x 75 cm]) and Portrait of the Dancer Jules Perrot (Fig. 1).

-

The Philadelphia drawing, dated 1875, shows Perrot’s head turned slightly more in profile than the Fitzwilliam drawing and could represent an evolution in Degas’s thinking, ultimately shifting it to full profile in the Nelson-Atkins composition. Degas made several other subtle changes to Perrot’s figure in the Nelson-Atkins composition, notably in the cut of the dance master’s coat, which in the Nelson-Atkins composition, rounds down from his lapels hiding more of the aging dance master’s midriff, as opposed to falling straight down as seen in the NGA monotype. For an image of these changes, see Rachel Freeman’s accompanying technical essay.

-

For a list of all the related works in which Perrot appears, see the “Related Works” section listed below this entry, researched by Nelson-Atkins Museum project assistant Danielle Hampton Cullen.

-

As in the two color versions of Degas’s Rehearsal pictures at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Nelson-Atkins dancers appear in white practice tutus with pink and blue sashes, and black velvet ribbons worn around their throats. Lillian Browse stated that Degas took artistic license with the latter two sartorial elements. Browse interviewed former dancer Suzanne Mante and M. Jacques Rouché, former director of the Opéra. See Lillian Browse, Degas Dancers (New York: Studio Publications, 1949), 67.

-

See Jill DeVonyar and Richard Kendall, Degas and the Dance, exh. cat. (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2002), 158–59.

-

DeVonyar and Kendall, Degas and the Dance, 158. Based on engravings, Lillian Browse first suggested that the three 1874 Rehearsal pictures (Metropolitan and Orsay) are of the stage in the Salle de la rue Le Peletier, the site of the Paris Opéra until it burned down on October 28, 1873. Although the ballet rehearsed after that point in a different location—first, temporarily, at the Salle Ventadour and then, from 1875 on, in Garnier’s new opera house—Browse suggests that Degas chose to present this scene as he first observed it, at the rue Le Peletier. See Browse, Degas Dancers, 67. While it is tempting to suggest that the Nelson-Atkins composition also represents the stage at the rue Le Peletier, as so many of its other elements are shared with the Rehearsal works, because of the tight cropping of NAMA image, it is difficult to tell with any certainty.

-

Browse, Degas Dancers, 67; see also Richard Kendall and Jill DeVonyar, “Degas’ ‘Two Dancers on Stage’: The Mozart Connection,” British Art Journal 2, no. 2 (2000): 78–80.

-

I am grateful to Kansas City classical ballet student Anne Bowser for identifying the position as “B-plus.” This term did not come into ballet parlance until the late 1940s. Historically, this position also went by names including Attitude à Terre, Pointe Derrière Croisé, and even Sur le Coup de Pied, according to Michael Langlois, former dancer with American Ballet Theatre and writer for Ballet Review. See Michael Langlois, “Origins of the term ‘B Plus,’” Ballet Talk for Dancers, January 19, 2019, https://dancers.invisionzone.com/topic/65782-origins-of-the-term-b-plus.

-

Even this elevated arm position was difficult to hold in a photograph; note the string holding Sanlaville’s left arm aloft.

-

See, for example, Honoré Daumier, The Singer’s Mother, 1856, lithograph, 8 x 9 1/2 in. (20.5 x 23.5 cm), private collection.

-

See Edgar Degas, Dancers Backstage, 1876/1883, oil on canvas, 9 1/2 x 7 3/8 in. (24.2 x 18.8 cm) National Gallery, Washington, DC, https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.52169.html.

-

See Henri Loyrette, “Degas à l’Opéra,” in Degas Inédit: Actes du Colloque Degas, Musée d’Orsay (Paris: Documentation française, 1989), 48–50; Loyrette also discusses Degas’s access backstage. See also DeVonyar and Kendall, Degas and the Dance, 79.

-

Lepic probably met Sanlaville backstage around 1867 at the Salle Le Peletier, which was the home of the Paris Opéra from 1821 until it was destroyed by fire in 1873. They were a familiar couple in Paris until Lepic’s death in 1889. For this and more biographical information on Lepic and Sanlaville, see Harvey Buchanan, “Edgar Degas and Ludovic Lepic: An Impressionist Friendship,” Cleveland Studies in the History of Art 2 (1997): 32–121.

-

L’Opéra: Eaux-Fortes et Quatrains, par un Abonné (Paris: Librairie des bibliophiles, 1876).

-

The anonymous author was most likely Henry de Fleurigny (pseudonym of Henri Micaud [1846–1916]), as cited in Buchanan, “Edgar Degas and Ludovic Lepic,” 91, 118n227. For another image of Sanlaville, see Artistes de l’Opéra: Recueil de portraits, ca. 1876, Bibliothèque nationale de France, https://images.bnf.fr/#/detail/344436/48.

-

Buchanan, “Edgar Degas and Ludovic Lepic,” 92.

-

Buchanan, “Edgar Degas and Ludovic Lepic,” 32.

-

Degas represented Sanlaville as Zail, standing behind the title figure in Mlle Fiocre in the Ballet “La Source” (1867–1868, oil on canvas, 51 1/2 x 57 1/8 in. [130.8 x 145.1 cm], Brooklyn Museum of Art, 21.111). Sanlaville also participated in a sketching session in Degas’s studio in the early 1880s, and later she figured in at least one portrait: Mlle Sanlaville (or Mlle S., Première Danseuse à l’Opéra), ca. 1886, pastel on paper, 15 3/8 x 10 5/8 in. (39 x 27 cm), private collection.

-

See Ronald Pickvance, “Degas’s Dancers: 1872–1876,” Burlington Magazine 105, no. 723 (June 1963): 256–67, esp. 264n71, for his proposed dating of the Nelson-Atkins composition to 1875 on the basis of a presumed acquisition date by Louisine Elder. Scholars like Theodore Reff have also shown that Degas inadvertently misdated drawings on occasion. See Theodore Reff, “New Light on Degas’s Copies,” Burlington Magazine 106, no. 735 (June 1964): 250–59.

-

See Edgar Degas, Pauline and Virginie Conversing with Admirers, ca. 1876–80, illustration for La famille Cardinal, monotype on paper, sheet: 11 3/8 x 7 1/2 in. (28.7 x 19.1 cm), Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University; and Edgar Degas, Dancers Backstage (see n. 19).

-

The specific color shop is also debated. Frances Weitzenhoffer says Elder purchased the pastel in 1875, probably from Père Tanguy’s; see Weitzenhoffer, The Havemeyers: Impressionism Comes to America (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1986), 21. Susan Alyson Stein says Elder purchased the pastel in 1877, probably from Père Tanguy’s shop; see Louisine W. Havemeyer, Sixteen to Sixty: Memoirs of a Collector, ed. Susan Alyson Stein, 2nd ed. (New York: Ursus Press, 1993), 331n291. Jean Sutherland Boggs says Elder probably purchased the painting in 1877; see Boggs et al., Degas, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1988), 258. I am grateful for the exhaustive provenance and backmatter research for this painting conducted by Danielle Hampton Cullen.

-

The painting belonged to Louisine Elder; however, in the exhibition catalogue, the lender is listed as G. W. Elder. These initials belonged to both Louisine’s deceased father (d. 1873), and her younger brother, George (1860–1916). See Illustrated Catalogue of the Eleventh Annual Exhibition of the American Water Color Society Held at the Galleries of the National Academy of Design, exh. cat. (New York, 1878), 14.

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Rachel Freeman, “Edgar Degas, Rehearsal of the Ballet, ca. 1876,” technical entry in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.614.2088

MLA:

Freeman, Rachel. “Edgar Degas, Rehearsal of the Ballet, ca. 1876,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.614.2088.

Rehearsal of the Ballet juxtaposes a muted background palette of green and gray gouachegouache: A term originating in eighteenth century France, which, historically, refers to an opaque paint consisting of colored pigments or dyes, a white opacifying pigment, and a polysaccharide binder, usually gum arabic. Traditional gouache recipes sometimes include honey as a humectant. Although twentieth century and twenty-first century gouache paints are often visually indistinguishable from historic gouache paints, modern gouache paints include a variety of additives that produce a reliably uniform paint in terms of tint and handling properties. and pastelpastel: A type of drawing stick made from finely ground pigments or other colorants (dyes), fillers (often ground chalk), and a small amount of a polysaccharide binder (gum arabic or gum tragacanth). While many artists made their own pastels, during the nineteenth century, pastels were sold as sticks, pointed sticks encased in tightly wound paper wrappers, or as wood encased pencils. Pastels can be applied dry, dampened, or wet, and they can be manipulated with a variety of tools including paper stumps, chamois cloth, brushes, or fingers. Pastel can also be ground and applied as a powder, or mixed with water to form a paste. Pastel is a friable media, meaning that it is powdery or crumbles easily. To overcome this difficulty, artists have used a variety of fixatives to prevent image loss., applied dry and as a paste, with luminous foreground figures executed predominately in dry pastel. The gouache and pastel are liberally applied so that they cover an underlying monotypemonotype: A type of planographic print where a design is drawn or painted on a non-porous surface, such as a printing plate or glass, and the design is transferred, in reverse, to paper by manual pressure, or pressure from a printing press. The monotype process produces unique prints because the ink is depleted each time paper comes in contact with the matrix. The first print is the strongest in terms of tone and contrast, and the quality decreases with each subsequent print. See also dark-field monotype and cognate. print. Both pastel and gouache are inherently unstable media, and thus the artwork has been through several conservation campaigns.

The artwork support is a cream colored, lightly textured, laid paperlaid paper: One of the two types of paper. Laid papers are machine or handmade papers, formed on a screen with parallel and tightly spaced wires that form "laid lines" which are visible on the sheet. The laid wires are held together by more widely spaced wires called "chain" lines. In handmade papermaking, the chain wires also secured the screen to the ribs of a wooden frame (the frame and wire assembly is referred to as a mold) that was dipped into a vat of paper-making fibers. In the late eighteenth century, there were widespread changes in the laid mold structure, and papers produced prior to this time are distinguishable by an accumulation of fibers along the chain lines. The other type of paper is wove paper..1The description of paper color/texture/thickness follows the standard set forth in Elizabeth Lunning and Roy Perkinson, The Print Council of America Paper Sample Book: A Practical Guide to the Description of Paper (Boston: Print Council of America, 1996), unpaginated. Technical reports by Anne Maheux2Ann Meheux, September 27, 1984, Special Report for Répétition de Ballet, NAMA conservation file, no. F73-30. On page 2 of the report, Meheux identifies the support as laid paper, and on page 3 she identifies the support as wove. and Nancy Heugh3Nancy Heugh, 29 March 2013/25 May 2014, French Painting Catalogue Project Technical Examination and Condition Report, NAMA conservation file, no. F73-30. have differed on the paper mold type, with Maheux noting that the paper is wovewove paper: One of the two types of paper. Wove papers may be either machine or handmade, and are produced from molds that have a woven wire mesh. The weave of the mesh can be so tight that it produces no visible pattern within the paper sheet, and often wove papers have a smoother surface than laid papers. Wove papers were developed during the mid-eighteenth century, but did not come into widespread use until later. The other type of paper is laid paper. and suggesting the presence of a watermarkwatermark: An identifying mark in a paper sheet which is created by tying wires to the papermaking mold. Watermarks are most easily viewed with transmitted light; however, some can be read with raking light. at upper left, while Heugh identifies the paper type as laid. During a 2020 examination for treatment, infrared (IR) photographyinfrared (IR) photography: A form of infrared imaging that employs the part of the spectrum just beyond the red color to which the human eye is sensitive. This wavelength region, typically between 700-1,000 nanometers, is accessible to commonly available digital cameras if they are modified by removal of an IR blocking filter that is required to render images as the eye sees them. The camera is made selective for the infrared by then blocking the visible light. The resulting image is called a reflected infrared digital photograph. Its value as a painting examination tool derives from the tendency for paint to be more transparent at these longer wavelengths, thereby non-invasively revealing pentimenti, inscriptions, underdrawing lines, and early stages in the execution of a work. The technique has been used extensively for more than a half-century and was formerly accomplished with infrared film. documented the presence of laid and chain lines, however a watermark was not observed. The edges of the paper are unevenly trimmed to within approximately two centimeters of the monotype’s platemarkplatemark: A depression in a sheet of paper caused by the edge of a printing plate. The platemark is the product of the pressure exerted by the printing press onto both the plate and the paper..

The composition began with a monotype print. Nineteenth century monotypes were made by applying viscous oil-based ink or paint to a rigid, non-porous surface (Degas used intaglio plates in copper and zinc, daguerreotype plates, and celluloid films).4Karl Buchberg and Laura Neufeld, “Indelible Ink: Degas’s Methods and Materials” in Degas: A Strange New Beauty, ed. Jodi Hauptman (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2016), 47. Pressure from an intaglio press transferred the image to paper. Only a few prints could be produced from each inked surface, because the ink film was depleted with each subsequent pull. The underlying monotype for Rehearsal of the Ballet (Fig. 2) is a cognatecognate: In monotypes, cognates are multiple prints pulled from an inked image on a plate. The first print is usually the strongest, and the image quality reduces with each subsequent pull. It is usually possible to pull only two or three prints before the image becomes unreadable. See also monotype. pair5For a discussion of cognate pairs, see Buchberg and Neufeld in Degas: A Strange New Beauty, 48. with The Ballet Master (ca. 1876; National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC).6Edgar Degas and Vicomte Ludovic Lepic, The Ballet Master, ca. 1876, monotype (black ink) heightened and corrected with white chalk or wash on laid paper, the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., Rosenwald Collection, 1964.8.1782. The pair are dark-field monotypesdark-field monotype: A subtractive image creation process where the printing matrix (the nonporous surface onto which the ink is applied) is entirely covered with ink, and the design is created by removing the ink. See also monotype. where the ink was applied to the plate and then removed with brushes, rags, and fingers to create the image. It is likely that The Ballet Master was printed first, because fine details, like the whorls of Degas’s fingerprints, are visible.7Personal communication from Kimberly Schenck, head of paper conservation, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., to the author, June 2020, NAMA conservation file, no. F73-30.

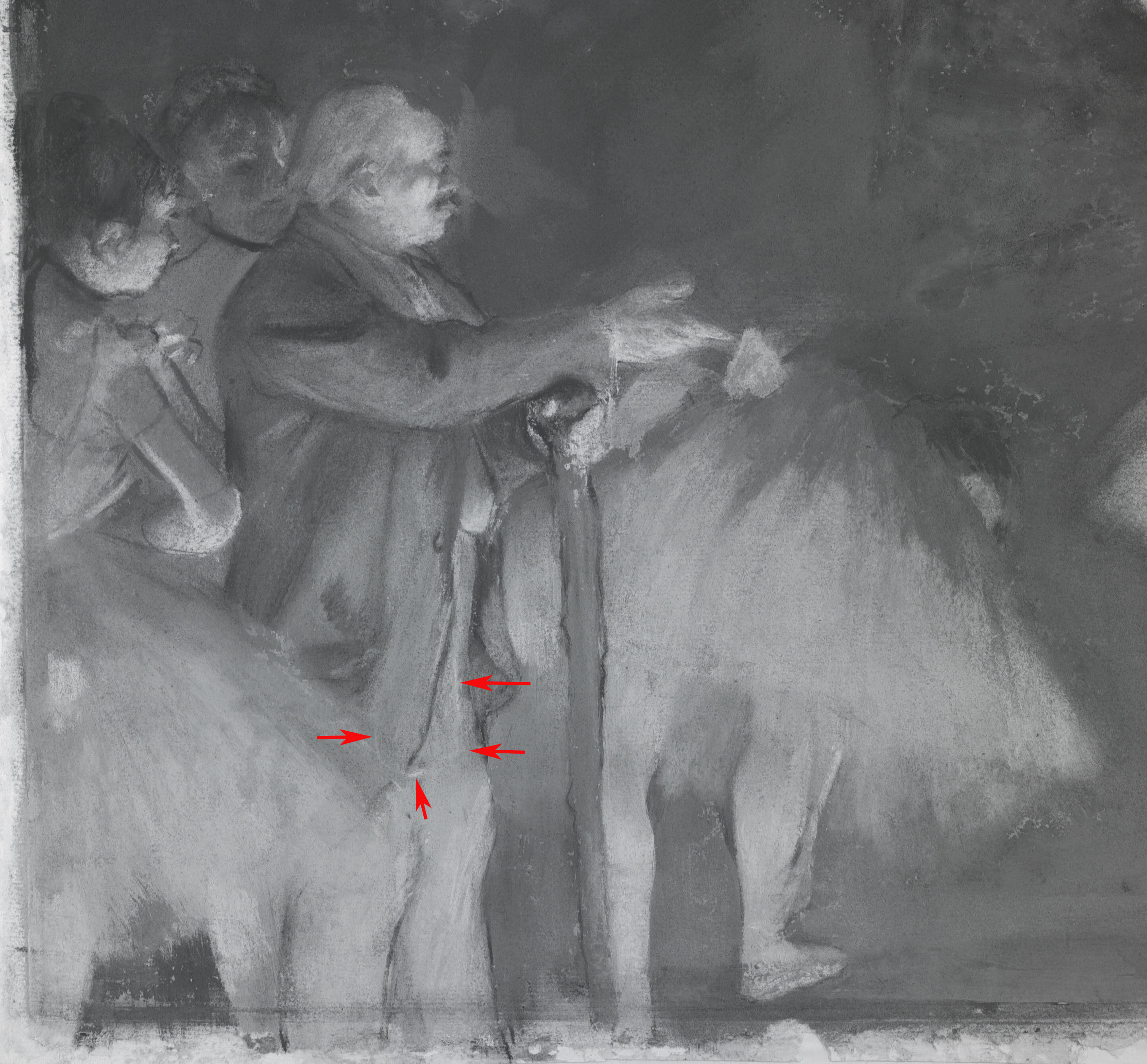

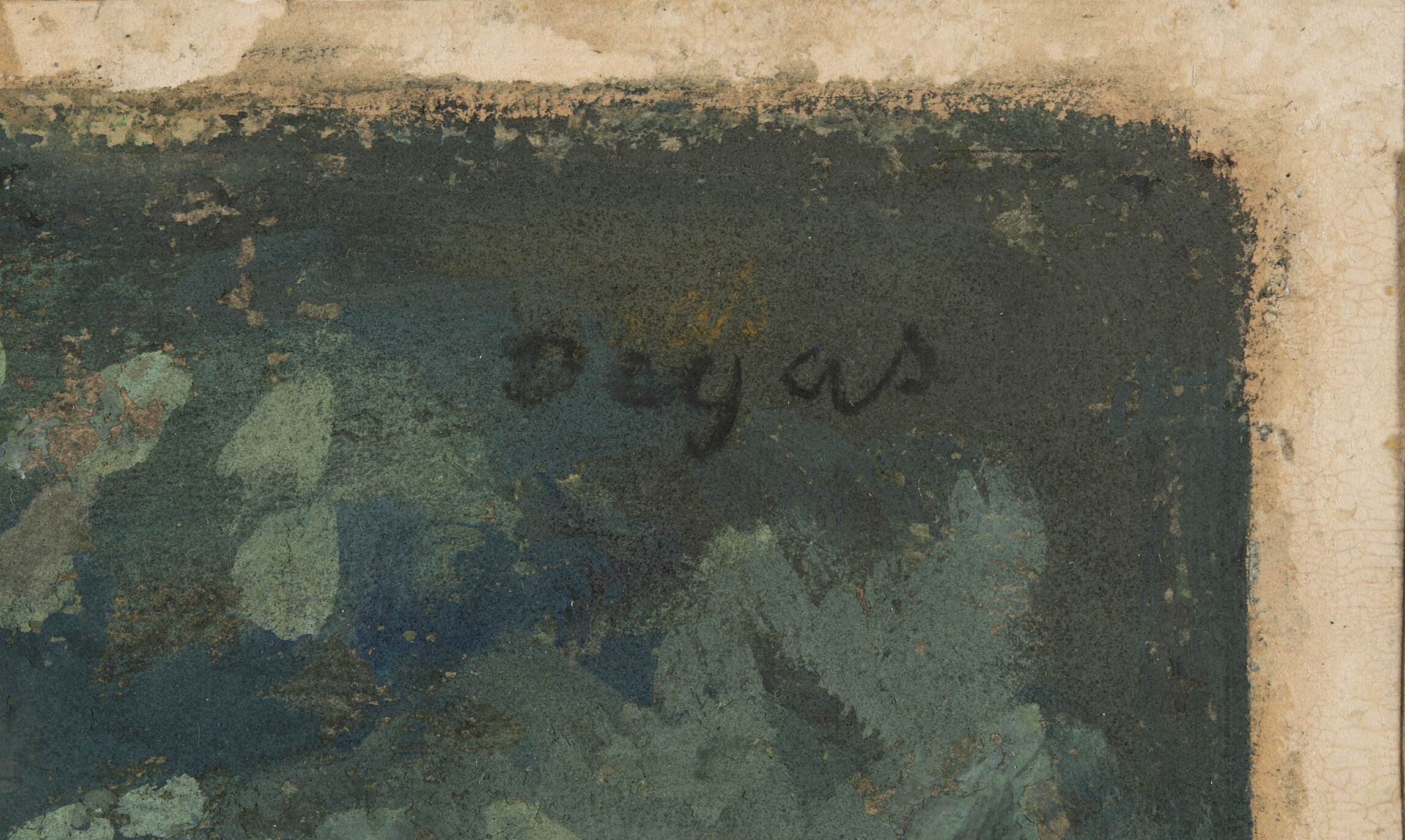

Rehearsal of the Ballet and The Ballet Master are among Degas’s earliest monotypes and are thought to be created with technical advice from Vicomte Ludovic Lepic, who countersigned the work at upper right. On both works there are distinct similarities in the marks left by the plate. For example, the dimensions (56.5 x 70 cm) of the platemarks are identical, and both images bear a mild, burnished indentation at lower right from a flaw in the plate (Fig. 7). With infrared photography of Rehearsal of the Ballet (Fig. 8), it is possible to see a few elements of the monotype: the rounded edge of the stage along the lower edge of the print, the original outlines of the dance master’s coat (Fig. 9), and Lepic’s signature (Fig. 10).

Fig. 7. Detail, in raking light, of the plate flaw along the lower edge of the image at right. The flaw is illuminated from the right for better readability. Rehearsal of the Ballet (ca. 1876)

Fig. 7. Detail, in raking light, of the plate flaw along the lower edge of the image at right. The flaw is illuminated from the right for better readability. Rehearsal of the Ballet (ca. 1876)

Fig. 8. Reflected infrared digital photograph of the entire work. The dark band curving along the lower edge of the image is the back of the orchestra pit. Rehearsal of the Ballet (ca. 1876)

Fig. 8. Reflected infrared digital photograph of the entire work. The dark band curving along the lower edge of the image is the back of the orchestra pit. Rehearsal of the Ballet (ca. 1876)

Fig. 9. Annotated reflected infrared digital photograph of Jules Perrot and dancers at lower left. The lines that describe the original outlines of the dance master’s coat are indicated with arrows. Rehearsal of the Ballet (ca. 1876)

Fig. 9. Annotated reflected infrared digital photograph of Jules Perrot and dancers at lower left. The lines that describe the original outlines of the dance master’s coat are indicated with arrows. Rehearsal of the Ballet (ca. 1876)

Fig. 10. Reflected infrared digital photograph of Vicomte Ludovic Lepic’s signature, reading “Lepic.” Without the aid of IR, only the “p” and “i” are visible. Rehearsal of the Ballet (ca. 1876)

Fig. 10. Reflected infrared digital photograph of Vicomte Ludovic Lepic’s signature, reading “Lepic.” Without the aid of IR, only the “p” and “i” are visible. Rehearsal of the Ballet (ca. 1876)

Fig. 11. In this image a tracing of the major forms in the National Gallery of Art’s monotype are superimposed over a reflected infrared digital photograph of Rehearsal of the Ballet (ca. 1876), illustrating the enlargement of the dancer.

Fig. 11. In this image a tracing of the major forms in the National Gallery of Art’s monotype are superimposed over a reflected infrared digital photograph of Rehearsal of the Ballet (ca. 1876), illustrating the enlargement of the dancer.

Fig. 12. Reflected infrared digital photograph of the dancer, at left, and a comparative image in normal illumination at right. In the final composition, Degas moved the dancer to a lower position on the page so that the back of the orchestra pit becomes her shadow. Rehearsal of the Ballet (ca. 1876)

Fig. 12. Reflected infrared digital photograph of the dancer, at left, and a comparative image in normal illumination at right. In the final composition, Degas moved the dancer to a lower position on the page so that the back of the orchestra pit becomes her shadow. Rehearsal of the Ballet (ca. 1876)

Fig. 13. Detail image of the dance master and dancers at lower left. The black pastel marks around the dancers indicate that Degas did a quick free hand drawing before applying color. The ankles of the group extend past the platemark, making the figures larger and bringing them into the foreground. Rehearsal of the Ballet (ca. 1876)

Fig. 13. Detail image of the dance master and dancers at lower left. The black pastel marks around the dancers indicate that Degas did a quick free hand drawing before applying color. The ankles of the group extend past the platemark, making the figures larger and bringing them into the foreground. Rehearsal of the Ballet (ca. 1876)

Fig. 14. Detail image of the Degas signatures at upper right, with the yellow signature, in pastel, partially covered by media. Rehearsal of the Ballet (ca. 1876)

Fig. 14. Detail image of the Degas signatures at upper right, with the yellow signature, in pastel, partially covered by media. Rehearsal of the Ballet (ca. 1876)

While the gouache and pastel are the most evident in Rehearsal of the Ballet, there is a thin, flexible, matte, brown paint film along the left, upper edge of the image. The texture contrasts with the powdery appearance of pastel, and it shows none of the flaking and paint loss present throughout the remainder of the artwork. This area may be an intermediate layer of de-oiled paint. Identified by Maheux in Degas Pastels as peinture à l’essencepeinture à l’essence: De-oiled paint. Peinture à l’essence was produced by the artist by leaching much of the linseed oil out of commercial paints and mixing the resulting thickened paint with turpentine. The resulting paint could be applied as a wash and dried more quickly than unmodified paint., Degas produced this medium by placing wet oil paint on blotting paper or another absorbent material until the linseed and other oils wicked out. He then mixed the resulting pigment slurry with turpentine.9Jean Sutherland Boggs and Anne Maheux, Degas Pastels (New York: George Braziller, 1992), 92. Degas may not have been pleased with the brown paint as it is not visible anywhere else in the composition.

Pastel is inherently friable, and pastel pastes and gouache form brittle paint films that powder, and crack, and flake away from the monotype as the paper support flexes or undulates. Media loss probably began soon after the composition was completed. Early in the lifetime of the artwork, casein was used as a fixative, forming a pattern of fine brown spatter marks across the entire image. The piece was subjected to multiple and substantial restoration campaigns prior to acquisition by The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. These include removal from a backing, which is described as “blue cardboard in the nineteenth century [French] manner.”10Forrest Bailey, Conservator, to Ralph T. Coe, Assistant Director and Curator of Western Art, both Nelson-Atkins, November 30, 1973, Subject line: A telephone call from Ben Johnson at 4:45pm, 11/30/73, NAMA conservation file, no. F73-30. This was likely a stiff paperboard, and the edges of the paper folded around this backing and were adhered into place. There is visual evidence that the paint layers were consolidated with a polyvinyl acetatepolyvinyl acetate: A thermoplastic resin created by polymerizing vinyl acetate. White in color and tacky when wet, it dries to form a clear, tough film. Polyvinyl acetate is used widely in emulsions for paints and adhesives. Also noted as PVAc, PVAC, or (less inaccurately) as PVA., losses were inpainted with gouache, and the original frame, designed by Degas, was disposed of.11Elizabeth Easton and Jared Bark, “‘Pictures Properly Framed’ Degas and Innovation in Impressionist Frames,” Burlington Magazine, no. 1266 (September 2008): 10–11. A description of the original frame first appeared in Louisine Havemeyer, Sixteen to Sixty: Memoirs of a Collector (New York: Ursus Press, 1943). At the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Heugh pursued consolidation with a cellulose ether in the early 1980s, and in 1987 Christine Young undertook an extensive and successful treatment to release the paper from intermediate and tertiary supports, “rag paper” and “kraft paper” respectively, consolidate the paint layers, and flatten undulations.12Christine Young, June 24, 1987, treatment report, NAMA conservation file, no. F73-30. A part of this conservation treatment campaign included a modified strip liningstrip lining: A conservation technique used to strengthen/repair tacking margins that have weakened or failed. New fabric is adhered to the painting’s damaged tacking margins to allow the stretcher to exert its normal tensioning on the original canvas. technique, utilizing a Japanese paper to attach the work to a thick matboard. The treatment also included fabrication of a framing package sealed with a rubber gasket. During recent preparation for future display, pastel and gouache particles were noted along the silk wrapped mat, and the work was unframed for further examination and consolidation treatment.

Notes

-

The description of paper color/texture/thickness follows the standard set forth in Elizabeth Lunning and Roy Perkinson, The Print Council of America Paper Sample Book: A Practical Guide to the Description of Paper (Boston: Print Council of America, 1996), unpaginated.

-

Ann Meheux, September 27, 1984, Special Report for Répétition de Ballet, NAMA conservation file, no. F73-30. On page 2 of the report, Meheux identifies the support as laid paper, and on page 3 she identifies the support as wove.

-

Nancy Heugh, 29 March 2013/25 May 2014, French Painting Catalogue Project Technical Examination and Condition Report, NAMA conservation file, no. F73-30.

-

Karl Buchberg and Laura Neufeld, “Indelible Ink: Degas’s Methods and Materials” in Degas: A Strange New Beauty, ed. Jodi Hauptman (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2016), 47.

-

For a discussion of cognate pairs, see Buchberg and Neufeld in Degas: A Strange New Beauty, 48.

-

Edgar Degas and Vicomte Ludovic Lepic, The Ballet Master, ca. 1876, monotype (black ink) heightened and corrected with white chalk or wash on laid paper, the National Gallery of Art, Washington DC, Rosenwald Collection, 1964.8.1782.

-

Personal communication from Kimberly Schenck, head of paper conservation, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, to the author, June 2020, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, F73-30.

-

See the accompanying catalogue essay by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan.

-

Jean Sutherland Boggs and Anne Maheux, Degas Pastels (New York: George Braziller, 1992), 92.

-

Forrest Bailey, Conservator, to Ralph T. Coe, Assistant Director and Curator of Western Art, both Nelson-Atkins, November 30, 1973, Subject line: A telephone call from Ben Johnson at 4:45pm, 11/30/73, NAMA conservation file, no. F73-30.

-

Elizabeth Easton and Jared Bark, “‘Pictures Properly Framed’ Degas and Innovation in Impressionist Frames,” Burlington Magazine, no. 1266 (September 2008): 10–11. A description of the original frame first appeared in Louisine Havemeyer, Sixteen to Sixty: Memoirs of a Collector (New York: Ursus Press, 1943).

-

Christine Young, June 24, 1987, treatment report, NAMA conservation file, no. F73-30.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Edgar Degas, Rehearsal of the Ballet, ca. 1876,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.614.4033

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Edgar Degas, Rehearsal of the Ballet, ca. 1876,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.614.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Edgar Degas, Rehearsal of the Ballet, ca. 1876,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.614.4033

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Edgar Degas, Rehearsal of the Ballet, ca. 1876,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.614.4033.

Purchased by Louisine Waldron Elder (later Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer, 1855–1929), New York, by 1877–no later than January 6, 1929 [1];

By descent to her daughter, Mrs. Peter Hood Ballantine Frelinghuysen (née Adaline Havemeyer, 1884–1963), Morristown, NJ, and Palm Beach, FL, by April 10, 1930–July 25, 1932 [2];

Given to her son, George Griswold Frelinghuysen (1911–2004), Beverly Hills, CA, 1932–April 14, 1965 [3];

Purchased at his sale, Impressionist and Modern Paintings, Sculptures, Drawings: “La Glace Haute” and “Ma Maison à Vernon” by Bonnard; “La Barque à St. Jean” and “La Madone du Village” by Chagall; “Répétition de Ballet” by Degas; “La Baignade devant le Port de Pont-Aven” by Gauguin; “Femme à l’Ombrelle Verte” by Matisse; “Les Peupliers” and “Nymphéas” by Monet; “Volume de Choses” by Staël; “Les Déchargeurs” by Van Gogh; “Portrait de la Comtesse de Noailles” by Vuillard, Sotheby’s, New York, April 14, 1965, lot 49, as Répétition de ballet, through Stephen Hahn, New York, by Norton Simon (1907–1993), Beverly Hills, CA, 1965–May 2, 1973;

Purchased at his sale, Ten Important Paintings and Drawings from the Private Collection of Norton Simon, Sotheby’s, New York, May 2, 1973, lot 7, as Repetition [sic] de ballet, by Marlborough Gallery, Vaduz, Liechtenstein, May 2–November 16, 1973;

Purchased from Marlborough Gallery by The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1973.

Notes

[1] Elder wrote in her memoirs that she purchased the pastel at an unnamed color shop. Scholars have not been able to definitively identify which one, but Portier, Latouche and Père Tanguy have all been proposed. Tanguy’s shop is cited by Susan Alyson Stein in Elder’s memoirs. See Frances Weitzenhoffer, The Havemeyers: Impressionism Comes to America (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1986), 21, and Louisine W. Havemeyer, Sixteen to Sixty: Memoirs of a Collector, ed. Susan Alyson Stein, 2nd ed. (New York: Ursus Press, 1993), 331n291.

The date of Elder’s purchase of the work is not certain, but it was one of Elder’s first purchases, bought on the advice of her friend, artist Mary Cassatt (American, 1844–1926). Most scholars agree that Elder bought the pastel by 1877; see Havemeyer, Sixteen to Sixty, 331n291. Elder definitely owned the pastel before February 1878, when she lent it to the Eleventh Annual Exhibition of the American Water Color Society.

[2] Louisine Havemeyer may have given the pastel to her daughter when she married on February 7, 1907. Havemeyer writes, “As each of you acquired a home of your own I gave to you works of art to beautify it, believing it would be the wish of Father to have me do so. These objects are yours and the disposition you finally make of them, your responsibility.” Havemeyer also noted, “Degas: I have given Adaline…the one I bought when a girl.” This was probably in reference to the Nelson-Atkins’ pastel, which Havemeyer fondly recalled her in memoires as her first Degas purchase when she was still a teenager. See Louisine Waldron Elder Havemeyer, “Notes to My Children” regarding disposition of Havemeyer art collection, Series II. Miscellaneous, box 3, folder 23, pp. 1, 7, The Havemeyer Family Papers relating to Art Collecting, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives, New York. In any case, the pastel was not in Havemeyer’s will listing artworks to be donated to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and it was also not among the artworks donated by Havemeyer’s three children in 1929. It was published in the 1931 H. O. Havemeyer Collection catalogue as being in Frelinghuysen’s collection.

[3] Paper label on the pastel’s verso inscribed: “To George on his / 21st birthday / from Mother”.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Edgar Degas, Rehearsal of the Ballet, ca. 1876,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.614.4033

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Edgar Degas, Rehearsal of the Ballet, ca. 1876,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.614.4033.

Edgar Degas, The Ballet Class, between 1871 and 1875, oil on canvas, 33 7/16 x 29 1/2 in. (85 x 75 cm), Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

Edgar Degas, executed in collaboration with Ludovic-Napoléon Lepic, The Ballet Master (Le maître de ballet), ca. 1874, monotype heightened and corrected with white chalk or wash, sheet: 24 7/16 x 33 7/16 in. (62 x 85 cm), plate: 22 1/4 x 27 9/16 in. (56.5 x 70 cm), National Gallery of Art, Washington, D. C.

Edgar Degas, Two Dancers on a Stage, ca. 1874, oil on canvas, 24 1/8 x 18 1/16 in. (61.5 x 46 cm), The Courtauld Gallery, London.

Edgar Degas, The Rehearsal Onstage, ca. 1874, pastel on paper, 21 x 28 1/2 in. (53.3 x 72.4 cm), The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Edgar Degas, The Rehearsal of the Ballet Onstage, ca. 1874, oil colors freely mixed with turpentine, with traces of watercolor and pastel over pen-and-ink drawing on cream-colored wove paper, laid down on bristol board and mounted on canvas, 21 3/8 x 28 3/4 in. (54.3 x 73 cm), The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Edgar Degas, The Dance Class, 1874, oil on canvas, 32 7/8 x 30 3/8 in. (83.5 x 77.2 cm), The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Edgar Degas, Répétition d’un ballet sur la scène, 1874, oil on canvas, 25 9/16 x 32 1/16 in. (65 x 81.5 cm), Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

Preparatory Works

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Edgar Degas, Rehearsal of the Ballet, ca. 1876,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.614.4033

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Edgar Degas, Rehearsal of the Ballet, ca. 1876,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.614.4033.

Edgar Degas, Two Dancers (Deux danseuses), 1873, dark brown wash and white gouache on bright pink commercially coated wove paper, now faded to pale pink, 24 1/8 x 15 1/2 in. (61.3 x 39.4 cm), The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Edgar Degas, Portrait of the Dancer Jules Perrot, 1875, black chalk, conté crayon, charcoal highlighted with white on paper, 18 1/2 x 12 3/16 in. (47.0 x 31.2 cm), The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

Edgar Degas, The Ballet Master, Jules Perrot, 1875, oil sketch on brown wove paper, 18 7/8 x 11 3/4 in. (47.9 x 29.8 cm), Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Edgar Degas, Danseuse vue de dos, ca. 1877, oil on paper, 11 x 12 5/8 in. (28 x 32 cm), Private Collection, Paris.

Edgar Degas, Sketches of a ballet master from an album of pencil sketches, ca. 1877, pencil on paper, 9 3/4 x 13 in. (24.8 x 33 cm), The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

Edgar Degas, Danseuse de trois-quarts a droite, nineteenth century, pencil on paper, 12 3/4 x 6 3/4 in. (32.5 x 17.5 cm), location unknown, illustrated in Impressionist and Modern Watercolors and Drawings and Contemporary Art (London: Christies, March 29, 1988), 16–17.

Edgar Degas, Study of a Ballet Dancer, nineteenth century, pencil on paper, 12 7/8 x 9 1/16 in. (32.7 x 23 cm), location unknown, illustrated in Christopher Lloyd, “Nineteenth Century French Drawings in the Bryson Bequest to the Ashmolean Museum,” Master Drawings 16, no. 3 (1978): unpaginated.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Edgar Degas, Rehearsal of the Ballet, ca. 1876,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.614.4033

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Edgar Degas, Rehearsal of the Ballet, ca. 1876,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.614.4033.

Possibly Catalogue de la 3e Exposition de Peinture par MM. Caillebotte, Cals, Cézanne, Cordey, Degas, Guillaumin, Jacques-François, Lamy, Levert, Maureau, C. Monet, B. Morisot, Piette, Pissarro, Renoir, Rouart, Sisley, Tillot, 6 rue Le Peletier, Paris, April 1877, no. 61, as Répétition de ballet.

Eleventh Annual Exhibition of the American Water Color Society, The National Academy of Design, New York, February 3–March 3, 1878, no. 133, as A Ballet.

Possibly Works in Oil and Pastel by the Impressionists of Paris, 1886: Special Exhibition, American Art Galleries, New York, April 10, 1886; National Academy of Design, New York, May 25, 1886, hors cat.

Loan Exhibition of Masterpieces by Old and Modern Painters, M. Knoedler and Company, New York, April 6–24, 1915, no. 33, as The Rehearsal with the Dancing Master.

Masterpieces of Art, World’s Fair, New York, April 30–October 1939, hors cat.

Masterpieces of Art, World’s Fair, New York, May–October 27, 1940, no. 274, as Répétition de Ballet (Ballet Rehearsal).

Répétition de Ballet, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA, July 7–October 21, 1965, no cat., as Répétition de Ballet.

Degas Monotypes, Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge, MA, April 25–June 14, 1968, no. 2, as Répétition de Ballet.

Exhibition of Works from the Collection of the Norton Simon Foundation and the Norton Simon Incorporated Museum of Art, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, June 15, 1972-June 15, 1974 (shown from January 24–February 12, 1973), no cat., as Rehearsal of the Ballet.

Fortieth anniversary exhibition, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, December 11, 1973–January 6, 1974, no cat., as Ballet Rehearsal.

The Impressionist Epoch, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, December 12, 1974–February 10, 1975, no cat.

Genre, The Nelson–Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, April 5-May 15, 1983, no. 36A, as Ballet Rehearsal.

Impressionism: Selections from Five American Museums, The Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, November 4–December 31, 1989; The Minneapolis Institute of Arts, January 27–March 25, 1990; The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, April 21–June 17, 1990; The Saint Louis Art Museum, July 14–September 9, 1990; The Toledo Museum of Art, September 30-November 25, 1990, no. 18 (Kansas City only), as Ballet Rehearsal.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Edgar Degas, Rehearsal of the Ballet, ca. 1876,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.614.4033

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Edgar Degas, Rehearsal of the Ballet, ca. 1876,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.614.4033.

Possibly Catalogue de la 3e Exposition de Peinture par MM. Caillebotte, Cals, Cézanne, Cordey, Degas, Guillaumin, Jacques-François, Lamy, Levert, Maureau, C. Monet, B. Morisot, Piette, Pissarro, Renoir, Rouart, Sisley, Tillot, exh. cat. (Paris: Imprimerie E. Capiomont et V. Renault, 1877), 6, as Répétition de ballet [repr. in Theodore Reff, ed., Modern Art in Paris: Two-Hundred Catalogues of the Major Exhibitions Reproduced in Facsimile in Forty-Seven Volumes, vol. 23, Impressionist Group Exhibitions (New York: Garland, 1981), unpaginated].

Possibly Paul Sebillot, “Exposition des impressionnistes,” Le Bien public (April 7, 1877): 2.

Possibly Léon de Lora, “L’Exposition de impressionnistes,” Le Gaulois (April 10, 1877): 2.

Possibly Ph. M., “Arts: Les Impressionnistes,” Revue des idées nouvelles, no. 11 (May 1, 1877): 167.

Illustrated Catalogue of the Eleventh Annual Exhibition of the American Water Color Society Held at the Galleries of the National Academy of Design, exh. cat. ([New York], 1878), 14, as A Ballet.

“American Water-Color Society: Eleventh Annual Exhibition; Reception to Artists and the Press; American and Foreign Exhibitors,” New York Times 27, no. 8235 (February 2, 1878): 5, as Ballet.

“The Old Cabinet,” Scribner’s Monthly 15, no. 6 (April 1878): 888–89, as A Ballet.

John Moran, “The American Water-Colour Society’s Exhibition,” The Art Journal 4 (1878): 92, as The Ballet.

“Les Impressionnistes,” L’Art Moderne 5, no. 1 (January 4, 1885): 107, as Répétition de Ballet.

“Les Impressionnistes,” L’Art Moderne (March 15, 1885): unpaginated, as Répétition de Ballet.

Loan Exhibition of Masterpieces by Old and Modern Painters, exh. cat. (New York: M. Knoedler, 1915), 20, as The Rehearsal with the Dancing Master.

“Art Show for Suffrage,” New York Times 64, no. 20,869 (March, 15, 1915): 10.

“Art Exhibit for Suffrage,” New York Times 64, no. 20,891 (April 6, 1915): 10.

“Loan Exhibition in Aid of Suffrage,” The Sun 82, no. 218 (April 6, 1915): 7.

“‘Art and Artists’, by Mrs. Havemeyer,” New York Times 64, no. 20,892 (April, 7, 1915), 7.

“Mrs. Havemeyer Praises Woman’s Art at Exhibit for Suffragist Fund,” The Sun 82, no. 219 (April 7, 1915): 3.

“Mrs. Havemeyer Talks of Artists,” New York Tribune 74, no. 24,979 (April 7, 1915): 11.

“Art of To-day and Yesterday,” Vogue 45, no. 10 (May 15, 1915): 61.

Possibly Julius Meier-Graefe, Degas, trans. J[ohn] Holroyd-Reece (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1923), 60, as Répétition de Ballet.

Dorothy Grafly, “In Retrospect—Mary Cassatt,” American Magazine of Art 18, no. 6 (1927): 308.

Louisine W. Havemeyer, “Mary Cassatt.” Bulletin of the Pennsylvania Museum 22, no. 113 (1927): 377.

Edith de Terey, “Mrs. Havemeyer’s Vivid Interest in Art,” New York Times 78, no. 25,943 (February 3, 1929): 117.

“Obituaries,” American Art Annual 26 (1929): 389.

“Mrs. Havemeyer’s Vivid Interest in Art,” New York Times 78, no. 25,943 (February 3, 1929): 117.

“Mrs. Havemeyer, Art Patron, Dies,” New York Times 78, no. 25,916 (January 7, 1929): 25.

“Mrs. Havemeyer,” New York Times 78, no. 25,929 (January 20, 1929): 13.

Probably Louisine Waldron Elder Havemeyer, “Notes to My Children” regarding disposition of Havemeyer art collection, by 1929, Series II. Miscellaneous, box 3, folder 23, The Havemeyer Family Papers relating to Art Collecting, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives, New York.

“Havemeyer Art Gift Valued at $3,489,461,” New York Times 80, no. 26,722 (March 24, 1931): 18.

H. O. Havemeyer Collection: Catalogue of Paintings, Prints, Sculpture and Objects of Art (Portland, ME: Southworth Press, 1931), 364–65, (repro.), as Répétition de Ballet.

Louise Burroughs, “Degas in the Havemeyer Collection,” Bulletin of The Metropolitan Museum of Art 27, no. 5 (May 1932): 141.

Forbes Watson, Mary Cassatt (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1932), 17.

Tristan Florisoone, “La Danse et les artistes du xvii siècle à nos jours,” L’Art et les Artistes 27, no. 140 (October 1933): 29, as La Répétition de Ballet.

Georges Rivière, Mr. Degas, Bourgeois De Paris (Paris: Floury, 1938), 87, as Répétition de Ballet.

Mary Cassatt, 1845–1926, exh. cat. (Haverford, PA: Haverford College Art Committee, 1939), unpaginated.

Walter Pach and Christopher Lazare, Catalogue of European and American Paintings, 1500–1900 ([New York]: Art Aid Corporation, 1940), 188–89, (repro.), as Répétition de Ballet (Ballet Rehearsal).

Hans Huth, “Impressionism comes to America,” Gazette des Beaux-Arts 29 (April 1946): 239, Dance Rehearsal.

P[aul] A[ndré] Lemoisne, Degas et son œuvre (Paris: Paul Brame et C. M. de Hauke, 1946–1949), no. 365, pp. 2:194–95, (repro.); 4:41, 97, 121, 139–40, 142, 153, as Répétition de Ballet.

Frederick A. Sweet, “America’s greatest woman painter: Mary Cassatt,” Vogue 123, no. 3 (February 15, 1954): 123, as La Répétition de Ballet.

François Fosca, Degas: Étude Biographique et Critique (Geneva: Éditions d’Art Albert Skira, 1954), 52–53, (repro.), as Répétition de Ballet.

Aline B[ernstein] Saarinen, “The Proud Possessors: The Henry O. Havemeyers, an adventurous pair who gave 1,972 objects of art to the Metropolitan Museum of Art,” Vogue 132, no. 6 (October 1, 1958): 148.

René Brimo, L’évolution du goût aux Etats-Unis, d’après l’histoire des collections (Paris: J. Fortune, 1958), 89.

Pierre Cabanne, Edgar Degas (Paris: Pierre Tisne, 1958), 41–42, 77, as Ballet Rehearsal.

Aline B[ernstein] Saarinen, The Proud Possessors: The Lives, Times and Tastes of Some Adventurous American Art Collectors (New York: Random House, 1958), 149.

Mary Cassatt, peintre et graveur, 1844–1926, exh. cat. (Paris: Centre culturel américain, 1959), unpaginated.

Louisine W. Havemeyer, Sixteen to Sixty: Memoirs of a Collector (New York, 1961), 249–51, as Répétition de Ballet [repr. in, Louisine W. Havemeyer, Sixteen to Sixty: Memoirs of a Collector, ed. Susan Alyson Stein, 2nd ed. (New York: Ursus Press, 1993), 204, 206–07, 249–51, 307n1, 331n291, 332n295, 336n364, 336n366, (repro.)].

Ronald Pickvance, “Degas’s Dancers: 1872–6,” Burlington Magazine 105, no. 723 (June 1963): 264, as la Répétition de Ballet.

W. G. Constable, Art Collecting in the United States of America: An Outline of a History (London: Thomas Nelson, 1964), 77, as Répétition de Ballet.

Advertisement, Burlington Magazine 107, no. 744 (March 1965): xlviii, liv, as Répétition de Ballet.

Sanka Knox, “A Degas is Bought for $410,000 Here,” New York Times 114, no. 39,163 (April 15, 1965): 30, as Répétition de Ballet.

Advertisement, International Art Market 5, no. 4/5 (June–July 1965): 112, (repro.), as Répétition de Ballet.

Denys Sutton, “The Discerning Eye of Louisine Havemeyer,” Apollo 82, no. 43 (September 1965), 231, as Répétition de Ballet.

“Department of Paintings,” and “Publications, Exhibitions, and Lecturers,” The Museum Year: Annual Report of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 90 (1965): 73, 91, as Répétition de Ballet.

Art-Price Annual, 1964–1965, vol. 20 (Paris: Editions Art and Technique, 1965), 366, as Répétition de Ballet.

Impressionist and Modern Paintings, Sculptures, Drawings: “La Glace Haute” and “Ma Maison à Vernon” by Bonnard; “La Barque à St. Jean” and “La Madone du Village” by Chagall; “Répétition de Ballet” by Degas; “La Baignade devant le Port de Pont-Aven” by Gauguin; “Femme à l’Ombrelle Verte” by Matisse; “Les Peupliers” and “Nymphéas” by Monet; “Volume de Choses” by Staël; “Les Déchargeurs” by Van Gogh; “Portrait de la Comtesse de Noailles” by Vuillard (New York: Parke-Bernet Galleries, April 14, 1965), 13, as Répétition de Ballet.

Michael Strauss, ed., Ivory Hammer 3: The Year at Sotheby’s and Parke-Bernet; The Two Hundred and Twenty First Season, 1964–65 (New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1965), 48, (repro.), as La Répétition de Ballet.

Frederick A. Sweet, Mary Cassatt, 1844–1926: A Retrospective Exhibition, exh. cat. (Chicago: International Galleries, 1965), unpaginated.

Art Prices Current: A Record of Sale Prices at the Principal London and Other Auction Rooms, vol. 42 (London: Art Trade Press, 1966), A131, as Répétition de Ballet.

Julia Carson, Cassatt (New York: David McKay, 1966), 109, as Répétition de Ballet.

Frederick A. Sweet, Miss Mary Cassatt: Impressionist from Pennsylvania (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1966), 29–30, 62, as La Répétition de Ballet.

Eugenia Parry Janis, “The Role of the Monotype in the Working Method of Degas: I,” Burlington Magazine 109, no. 766 (January 1967): 21, 22n13, 23, (repro.), as Répétition de Ballet.

Eugenia Parry Janis, “The Role of the Monotype in the Working Method of Degas: II,” Burlington Magazine 109, no. 767 (February 1967): 72, as Répétition de Ballet.

Raymond Cogniat, Degas (Lugano: Uffici Press, 1968), 18, (repro.), as Ballet Rehearsal.

Eugenia Parry Janis, Degas Monotypes, Essay, Catalogue and Checklist, exh. cat. ([Cambridge, MA]: Fogg Art Museum, 1968), xviii, unpaginated, (repro.), as Répétition de Ballet.

Pierre Schneider, The World of Manet, 1832–1883 (New York: Time-Life Books, 1968), 138, 158, (repro.), as Ballet Rehearsal.

Geraldine Keen, “Dealers raise prices after record US art sale,” Times (London), no. 57,693 (October 17, 1969): 20, as Répétition de Ballet.

L. B. Gillies, “European Drawings in the Havemeyer Collection,” Connoisseur 172, no. 693 (November 1969), 149, 153, as Répétition de Ballet.

Adelyn D. Breeskin, Mary Cassatt: A Catalogue Raisonné of the Oils, Pastels, Watercolors, and Drawings (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1970), 9.

Franco Russoli and Fiorella Minervino, L’opera completa di Degas (Milan: Rizzoli Editore, 1970), no. 485, pp. 109, (repro.), as Prova di Balletto in Scena, con Maestro.

Wesley Towner, The Elegant Auctioneers (New York: Hill and Wang, 1970), 120.

Ellen Wilson, American Painter in Paris: A Life of Mary Cassatt (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1971), 51–53, 55, 203, (repro.), as The Ballet Rehearsal.

John E. Bullard, Mary Cassatt: Oils and Pastels (New York: Watson-Guptill, 1972), 13, 18, 20.

Robin McKown, The World of Mary Cassatt (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Co, 1972), 48, 75, as Repetition de Ballet.

Geraldine Norman, “Big prices likely at Norton Simon sale,” Times (London), no. 58,744 (March 29, 1973): 4, (repro.), as Repetition de Ballet.

Advertisement, Burlington Magazine 115, no. 841 (April 1973): xxii, xxv, (repro.), as Répétition de Ballet.

Sanka Knox, “Norton Simon Art, with 2 Cézanne’s, will be sold here,” New York Times 122, no. 42,071 (April 1, 1973): 77.

“Highest Prices for Priceless Art,” Kansas City Star 93, no. 228 (May 3, 1973): 5, as Répétition de Ballet.

Sanka Knox, “Norton Simon Art Sold for 6.7 Million,” New York Times 122, no. 42103 (May 3, 1973): 89, as Répétition de Ballet.

Lode Seghers, “Mercado de las arte en el Extranjero,” Goya 115, no. 63 (July 1973): 63, (repro.), as Repetición de ballet.

Advertisement, Pantheon 31, no. 3 (July–August 1973): 348, (repro.), as Répétition de Ballet.

Donald Hoffmann, “Gifts Grace Gallery’s 40th Year,” Kansas City Times 106, no. 82 (December 12, 1973): 1, 12, (repro.), as Ballet Rehearsal.

“Kansas City Woman Gives Nelson Gallery A $1-Million Degas,” supplement, New York Times 123, no. 42.326 (December 12, 1973): 62, as Repetition [sic] de Ballet.

Kathleen Patterson, “Gallery Champagne, Glitter,” Kansas City Times 106, no. 82 (December 12, 1973): 13, as Ballet Rehearsal.

“The Supreme Birthday Present,” Independent (December 12, 1973): unpaginated, as Ballet Rehearsal.

“Over my Shoulder,” Independent (December 15, 1973): unpaginated, as Ballet Rehearsal.

“On the Rise,” Kansas City Star 94, no, 104 (December 30, 1973): unpaginated, (repro.), as Ballet Rehearsal.

Franz Park, “Care to see my Etchings? They Proved the Best Investment of 1973,” Barron’s National Business and Financial Weekly 52, no. 63 (December 31, 1973): 11, as Répétition de Ballet.

Moussa M. Domit, American Impressionist Painting, ext. cat. (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1973), 47n29.

Annamaria Edelstein, ed., Art at Auction: The Year at Sotheby Parke-Bernet, Two hundred and thirty-ninth season, 1972–73 (New York: The Viking Press, 1973), 123, as Répétition de Ballet.

John Rewald, The History of Impressionism (1946; repr. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1973), 310.

Ten Important Paintings and Drawings from the Private Collection of Norton Simon (New York: Sotheby Parke Bernet, May 2, 1973), unpaginated, (repro.), as Repetition [sic] de Ballet.

Hertha Wellensiek and Robert Keyszelitz, Art-Price Annual, 1972–1973, vol. 28 (Paris: Editions Art and Technique, 1973), 389, as Répétition de Ballet.

“Major Accession,” Gallery Events (The Nelson Gallery and Atkins Museum) (January 1974): unpaginated, (repro.), as Ballet Rehearsal.

Donald Hoffmann, “Visual Arts Here Keep Pace with Fast Moving Times,” Kansas City Star 94, no. 125 (January 20, 1974): unpaginated, (repro.), as Ballet Rehearsal.

Donald Hoffmann, “Nelson Gallery Construction To Start on the Second Floor,” Kansas City Times 104, no. 265 (July 13, 1974): 3A, as Ballet Rehearsal.

Jean Adhémar and Françoise Cachin, Degas: The Complete Etchings, Lithographs, and Monotypes (New York: Viking Press, 1974), 269, 281, as Ballet Rehearsal (Répétition de Ballet).

Richard J. Boyle, American Impressionism (Boston, MA: New York Graphic Society, 1974), 54, 112.

Barbara Stern Shapiro, Edgar Degas, the Reluctant Impressionist, exh. cat. (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1974), unpaginated, as Répétition de Ballet.

“Spencer Gift for K.U. Gallery,” Kansas City Times 13, no. 174 (March 29, 1975): 2A, as Ballet Rehearsal.

Nancy Hale, The Life of Mary Cassatt (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1975), 54, as Répétition de Ballet.

Karen M. Jones, “Museum Accessions,” Antiques 109, no. 1 (January 1976): 66, (repro.), as Ballet Rehearsal.

Laurence Sickman, “The Gallery in the Bicentennial Year,” and “Recent Acquisitions,” Bulletin (The Nelson Gallery and Atkins Museum) 5, no. 3 (February 1976): 4, 38, (repro.), as Ballet Rehearsal.

Donald Hoffman, “Other Gifts,” Kansas City Star 96, no. 151 (February 15, 1976): 2D, as Ballet Rehearsal.

Art Prices Current: A Record of Sale Prices at the Principal London and Other Auction Rooms, vol. 50 (London: Dawson and Sons, 1976), A74, as Répétition de Ballet.

Theodore Reff, ed., The Notebooks of Edgar Degas: A Catalogue of the Thirty-Eight Notebooks in the Bibliothèque Nationale and Other Collections (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1976), 1:164, as Répétition de Ballet.

Charles S. Moffett and Elizabeth Streicher, “Mr. and Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer as collectors of Degas,” The Nineteenth Century Philadelphia 3, no. 1 (1977): 23, 25, (repro.), as Répétition de Ballet.

Katherine Schwarz, “Monotypes: Where are they?” The Print Collector’s Newsletter 9, no. 5 (1978): 156.

Ian Dunlop, Degas (London: Thames and Hudson, 1979), 7, 113, 121, (repro.), as Ballet Lesson on Stage.

“$5.2 million for Van Gogh sets impressionist record,” Kansas City Star 106, no.286 (May 14, 1980): 6A, as Répétition de Ballet.

William H. Gerdts, American Impressionism, exh. cat. (Seattle: Henry Art Gallery, 1980), 26, 28, 46, (repro.), as Ballet Rehearsal (A Ballet).

Richard H. Love, Cassatt, the Independent (Chicago: R. H. Love, 1980), 12, 49, as La Répétition de Ballet.

Ann Havemeyer, “Cassatt: The Shy American,” Horizon 24, no. 24 (March 1981): 59, 62.

Donald Hoffman, “Benefactors’ gifts help keep inflation at bay at the Nelson,” Kansas City Star 101, no. 225 (June 7, 1981): 1F, as Ballet Rehearsal.

Adelyn Dohme Breeskin, Mary Cassatt: A Catalogue Raisonné of the Graphic Work (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1981), 13.

Frank Herrmann, Sotheby’s, Portrait of an Auction House (New York: Norton, 1981), 400–01.

Sophie Monneret, L’Impressionnisme et son Époque (Paris: Éditions Denoël, 1981), 1: 269; 3: 150; 4: 105, as Répétition de Ballet.

Alicia Faxon, “Painter and Patron: Collaboration of Mary Cassatt and Louisine Havemeyer,” Woman’s Art Journal 3, no. 2 (1982): 15, as Répétition de Ballet.

Mark Fraser, “Helen F. Spencer’s death ends career of a philanthropist,” Kansas City Times 114, no. 139 (February 16, 1982): A4, as Ballet Rehearsal.

Antonia Lant, “Purpose and Practice in French Avant-Garde Print-Making of the 1880s,” Oxford Art Journal 6, no. 1 (1983): 24.

Ross E. Taggart and Laurence Sickman, Genre, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1983), 8, 15, 27, (repro.), as Ballet Rehearsal.

Laura Babcock, “The Nelson Art Gallery: a salute to the past,” Kansas City Star 104, no. 19 (October 9, 1983): 2F, as Ballet Rehearsal.

“Remember when?,” Kansas City Times 116, no. 82 (December 12, 1983): A13, as Ballet Rehearsal.

Richard Brettell and Suzanne Folds McCullagh, Degas in the Art Institute of Chicago, exh. cat. (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 1984), 73.

William H. Gerdts, American Impressionism (New York: Abbeville Press, 1984), 35, 49, 53, (repro.), as A Ballet and Ballet Rehearsal.

Nancy Mowll Mathews, Cassatt and her Circle: Selected Letters (New York: Abbeville Press, 1984), 278.

Sue Welsh Reed and Barbara Stern Shapiro, Edgar Degas: The Painter as Printmaker (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1984), liin21, as La Répétition de Ballet.

John Rewald and Frances Weitzenhoffer, Aspects of Monet: A Symposium on the Artist’s Life and Times (New York: Abrams, 1984), 78, 90n19, as Ballet Rehearsal.

George T. M. Shackelford, Degas: The Dancers, exh. cat. (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1984), 58–59, (repro.), as The Ballet Rehearsal.

Natalie Spassky, Mary Cassatt (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1984), 27.

Jean Sutherland Boggs, “Degas at the Museum: Works in the Philadelphia Museum of Art and John G. Johnson Collection,” Philadelphia Museum of Art Bulletin (Spring 1985): 7.