Conservation Introductory Essay

- Mary Schafer

- Rachel Freeman

- John Twilley

The conservation department at The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art was established in the 1930s and has a long history of research and scholarship. As is common for most institutions, then and now, treatment often takes priority over research. While many of the works in the French collection have undergone treatment to address structural or aesthetic concerns, their creation in terms of the art-making process has been explored to a lesser degree. Under the auspices of the French catalogue project, therefore, we were given an opportunity to study each work carefully from a technical art history perspective, uncovering new details gleaned directly from the artworks and often revealing what lies beneath the paint and pastel layers. Did the artist rely on an underdrawing or other preparatory layers? What techniques were employed to achieve certain effects? Were any modifications made to the composition? How has the passage of time affected the appearance of the artwork today? This technical knowledge enriches our understanding of the artist’s process and the artwork’s materiality.

For the conservation research, it was important to balance the ambitious nature of a catalogue project and the unlimited opportunities of online publishing, with a measured approach that aligned with our staff and resources. Each technical entry provides a description of the support, evidence of any preparatory process, sequence and description of media application, potential artist changes, and a brief overview of the treatment history and current condition. Our small staff size required a targeted approach to examining all 110 works in terms of scientific analysis, photography, and radiography. Each painting and pastel was unframed and carefully studied using a stereomicroscope, ultraviolet illumination, raking illumination, specular illumination, and infrared reflectography. Radiography was limited to those paintings with underlying paint textures or other intriguing questions that might be resolved using this examination tool. Significant questions that could only be explored through scientific means were pursued on a case-by-case basis.

The Nelson-Atkins is well suited to tackle scientific questions related to its collection. Recognizing the breadth of the museum’s holdings and its commitment to scholarly research, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation established an endowment for scientific research in 2009. The unique structure of this program circumvents the need for a fully equipped laboratory and staff scientist by providing access to a science advisor on contract who participates in the development of research questions, conducts scientific analysis, and engages colleagues from other disciplines to apply their expertise toward Nelson-Atkins projects. Each scientific project follows the successful model of the “three-legged stool,” a holistic approach to the study of an artwork that involves close collaboration among the scientist, conservator, and curator.

The catalogue contains several expanded technical entries co-authored by conservator and scientist. One of the first scientific projects undertaken for the catalogue was the study of The Triumph of Bacchus (1635–1636), one of three bacchanal-themed paintings executed by Nicolas Poussin for Armand Jean du Plessis, Cardinal de Richelieu (Fig. 1). By comparing the Richelieu series using statistical measures and pattern-matching for the thread spacings and intersection angles in the canvases, the project sought to settle a lingering question present in the literature: was the Nelson-Atkins painting merely a high-quality, contemporaneous copy by another artist? The exciting outcome bolsters the prevailing view that the Nelson-Atkins painting is indeed by the hand of Poussin. Following up on this extreme similarity in canvases, a subsequent study of the artist’s materials and working methods has now added to the body of research concerning this artist. The interdisciplinary nature of the Poussin study and the significance of these results for the entire series are precisely the type of impactful research that the Mellon Foundation envisioned for the endowment.

The catalogue’s first launch includes Rehearsal of the Ballet by Edgar Degas, one of the most studied pastels in the collection at the Nelson-Atkins (Fig. 2). A highly experimental work, this piece represents both Degas’s early adoption of the monotype as underdrawing as well as the artist’s innovative use of gouache and pastel. A recent conservation campaign included infrared imaging, which provides a detailed look at the relationship between the paint layers and the underlying monotype.

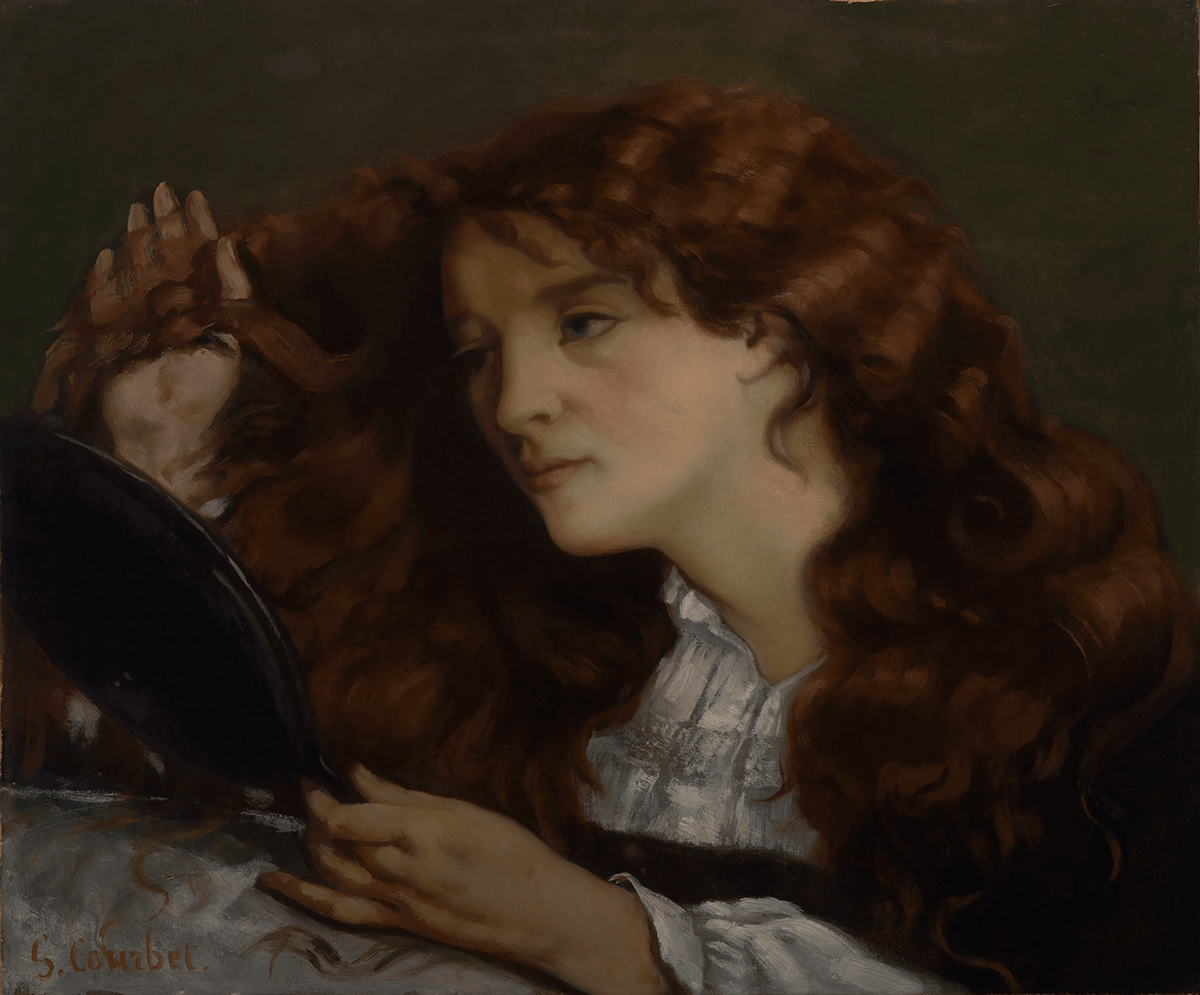

Noteworthy treatments were also undertaken in anticipation of the collection

catalogue. Following the identification of several artist changes and removal of

discolored varnish and retouching during treatment, Head of a Girl (ca. 1770 or later),

formerly regarded as a copy, was reinstated as an autograph work by Jean-Baptiste

Greuze (Fig. 3). Similarly, Gustave Courbet’s Jo, the Irish Woman (ca. 1866–1868)

was also prioritized for treatment (Fig. 4). The degree of discolored overpaint and

retouching covering the painting was considered so disfiguring that, in his 1978

catalogue raisonné, Robert Fernier chose to publish a photograph from the

posthumous Courbet exhibition of 1882 rather than show an image of the artwork in

its current state.1Robert Fernier, La Vie et l’œuvre de Gustave Courbet: Catalogue Raisonné 2 (Lausanne: Bibliothèque des arts, 1978), 12. The painting was cleaned in 2012,

at which time extensive damages were carefully addressed in a manner that reveals,

as much as possible, the artist’s intentions.

Fig. 3. Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Head of a Girl, ca. 1770 or later, oil on canvas, 17 1/2 x 14 1/2 in. (44.5 x 36.8 cm), Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 31-55

Fig. 3. Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Head of a Girl, ca. 1770 or later, oil on canvas, 17 1/2 x 14 1/2 in. (44.5 x 36.8 cm), Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 31-55

Fig. 4. Gustave Courbet, Jo, the Irish Woman, ca. 1866–1868, oil on canvas, 21 3/8 x 25 in. (54.3 x 63.5 cm), Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 32-30

Fig. 4. Gustave Courbet, Jo, the Irish Woman, ca. 1866–1868, oil on canvas, 21 3/8 x 25 in. (54.3 x 63.5 cm), Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 32-30

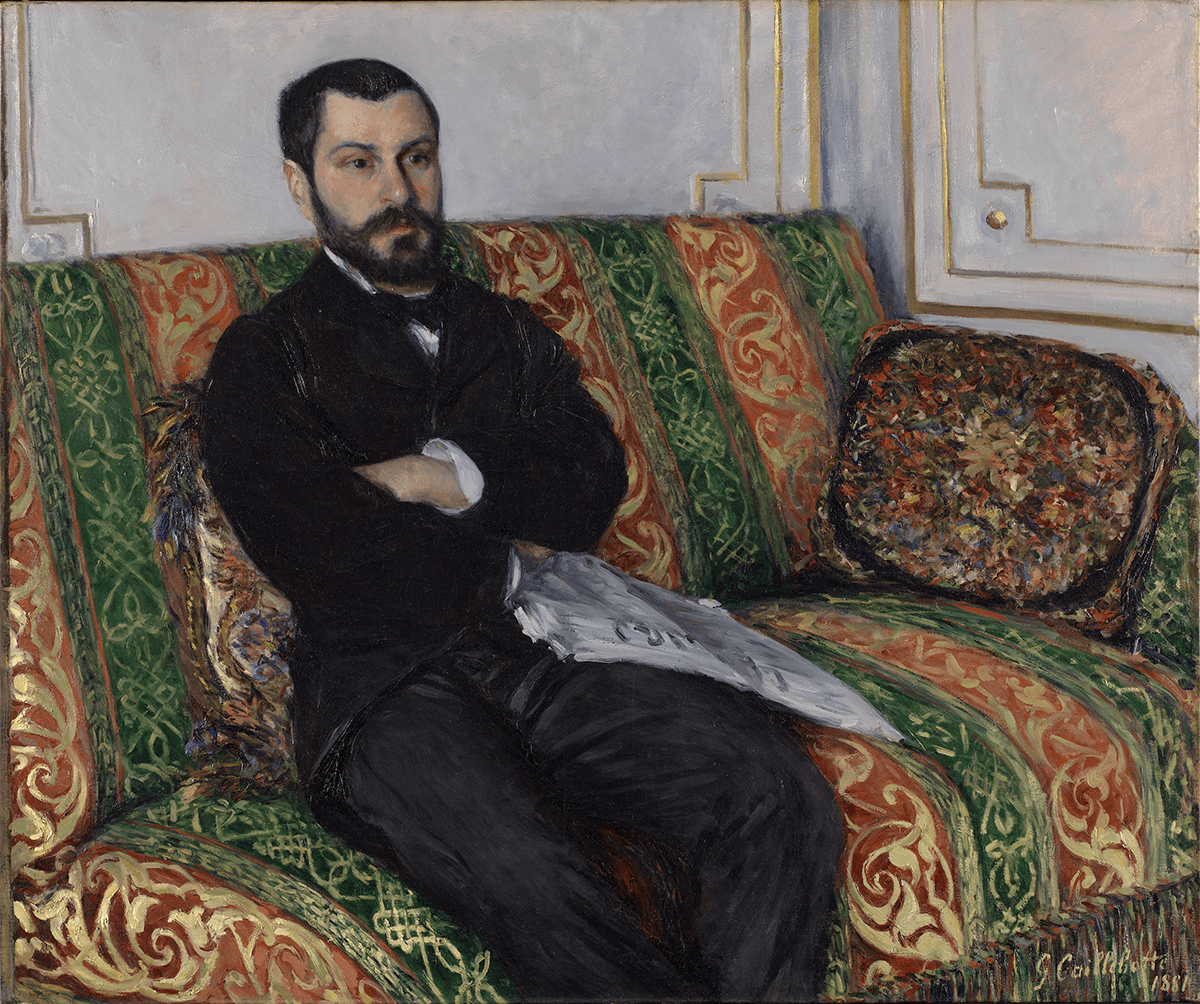

Our research was truly an interdisciplinary effort, with contributions from across

the conservation department. Kate Garland, senior objects conservator, treated the

original frame that accompanies Gustave Caillebotte’s Portrait of Richard Gallo (1881)

(Fig. 5). Joe Rogers, conservation associate, assisted in the radiography of

numerous paintings, and Saori Lewis, associate photography conservator, facilitated

early examinations of the pastel collection. With her knowledge of the museum’s

pastel collection, paper conservator and former staff member Nancy Heugh was an

invaluable resource, and many of the technical entries are based on her examination

reports. R. Bruce North, museum volunteer, offered his time and expertise in the

macrophotogrammetrymacrophotogrammetry: A process of recording measurements through multiple, overlapping photographs captured from different angles of an artwork. The photographs are mathematically combined to create a three-dimensional model of the object or its surface. of Van Gogh’s Olive Trees (1889)

(Fig. 6).

Fig. 5. Gustave Caillebotte, Portrait of Richard Gallo, 1881, oil on canvas, 38 1/4 x 45 7/8 in. (97.2 x 116.5 cm), Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 89-35

Fig. 5. Gustave Caillebotte, Portrait of Richard Gallo, 1881, oil on canvas, 38 1/4 x 45 7/8 in. (97.2 x 116.5 cm), Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 89-35

Fig. 6. Vincent van Gogh, Olive Trees, June/September 1889, oil on canvas, 28 3/4 x 36 1/4 in. (73 x 92.1 cm), Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 32-2

Fig. 6. Vincent van Gogh, Olive Trees, June/September 1889, oil on canvas, 28 3/4 x 36 1/4 in. (73 x 92.1 cm), Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 32-2

We also wish to extend our thanks to the curatorial team, led by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Louis L. and Adelaide C. Ward Senior Curator of European Arts, for their collaborative work in the study of this remarkable collection. We are grateful to former curators Simon Kelly and Nicole R. Myers, who guided the early stages of the project. For her expert editing skills, we also thank Wendy Partridge. We are also deeply indebted to those conservation and curatorial colleagues in other institutions who graciously shared technical information and imagery in support of our research.

Collectively, this research represents an ongoing commitment to stewardship and study of the museum’s diverse collection. It is our hope that the conservation research will offer new insights into the working methods of the artists represented, provide a valuable reference to colleagues within the field, and expand upon the enjoyment of these artworks for the general reader.

Notes

- Robert Fernier, La Vie et l’œuvre de Gustave Courbet: Catalogue Raisonné 2 (Lausanne: Bibliothèque des arts, 1978), 12.↩