![]()

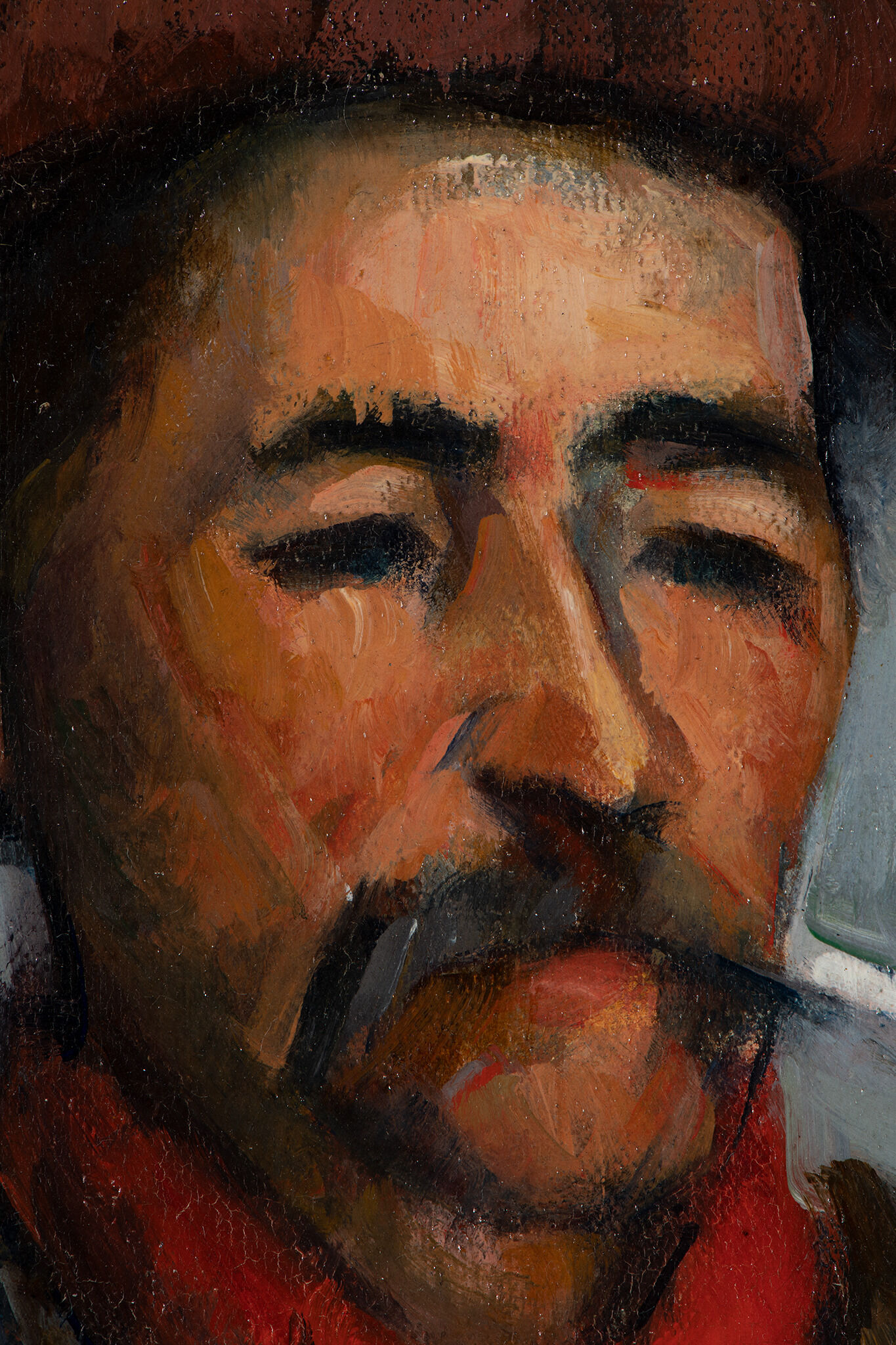

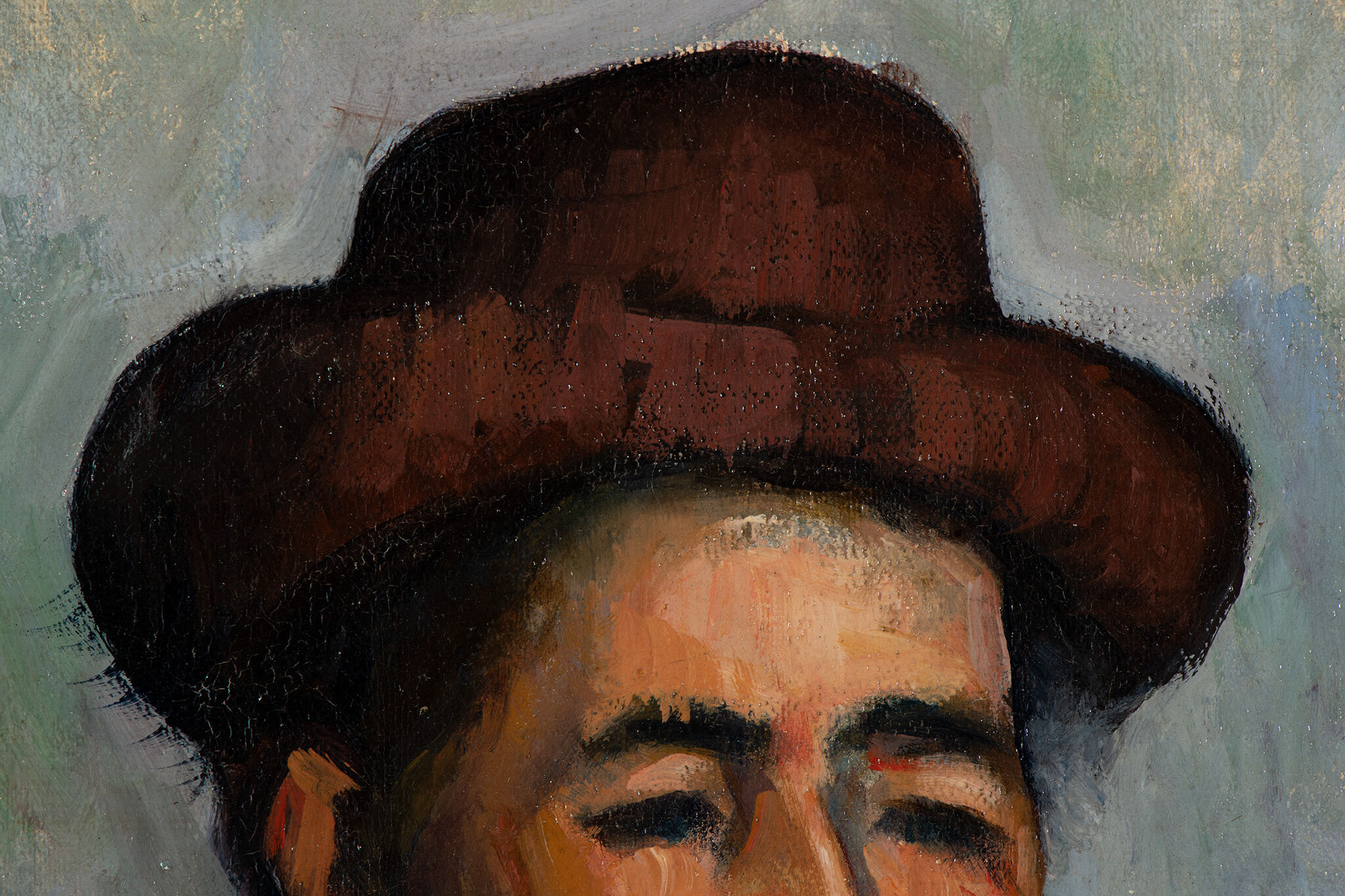

Paul Cezanne, Man with a Pipe, 1890–92

| Artist | Paul Cezanne, French, 1839–1906 |

| Title | Man with a Pipe |

| Object Date | 1890–92 |

| Alternate and Variant Titles | L’homme à la pipe; Étude d’homme debout fumant sa pipe |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (Unframed) | 17 x 13 1/2 in. (43.2 x 34.3 cm) |

| Credit Line | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Gift of Henry W. and Marion H. Bloch, 2015.13.6 |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Paul Cezanne, Man with a Pipe, 1890–92,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.708.5407.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Paul Cezanne, Man with a Pipe, 1890–92,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.708.5407.

When Paul Cezanne’s father, Louis-Auguste Cezanne, purchased the Jas de Bouffan in September 1859, he could not have foreseen that this country estate would serve as the staging ground for many of his son’s most famous paintings, including the Card Players series.1The deed of purchase is preserved in the Archives départementales des Bouches-du-Rhône, Marseille. For a transcription of this document, see Monsieur Paul Cezanne, rentier, artiste peintre: Un créateur au prisme des archives (Marseille: Archives départementales des Bouches-du-Rhône, 2006), 94–107. A thirty-five-acre property on the outskirts of Aix-en-Provence, the Jas de Bouffan boasted an eighteenth-century farmhouse, landscaped gardens, and enviable views of Mont Sainte-Victoire. Cezanne’s strong attachment to this homestead and his anguish at being forced to sell it following his mother’s death in 1897 are well known.2After Cezanne’s father died in 1886, the Jas de Bouffan was jointly owned by Cezanne and his two siblings. When Cezanne’s mother passed away a decade later, his sister and her husband no longer wished to retain their shares, necessitating a sale. See Alex Danchev, Cézanne: A Life (New York: Pantheon Books, 2012), 322. In addition to depicting the grounds and buildings of the Jas de Bouffan from numerous vantage points, Cezanne also painted genre scenes and figure studies there, including Man with a Pipe. This half-length portrait portrays a stoic smoker who appears as an onlooker in two multifigure iterations of The Card Players (Figs. 1, 2).3There are also three two-figure paintings in the Card Players series, in which this spectator does not appear.

Fig. 1. Paul Cezanne, The Card Players, ca. 1890–92, oil on canvas, 25 3/4 x 32 1/4 in. (65.4 x 81.9 cm), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Stephen C. Clark, 1960

Fig. 1. Paul Cezanne, The Card Players, ca. 1890–92, oil on canvas, 25 3/4 x 32 1/4 in. (65.4 x 81.9 cm), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Stephen C. Clark, 1960

Fig. 2. Paul Cezanne, The Card Players, ca. 1890–92, oil on canvas, 53 1/4 x 71 5/8 in. (135.3 x 181.9 cm), Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, BF564

Fig. 2. Paul Cezanne, The Card Players, ca. 1890–92, oil on canvas, 53 1/4 x 71 5/8 in. (135.3 x 181.9 cm), Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, BF564

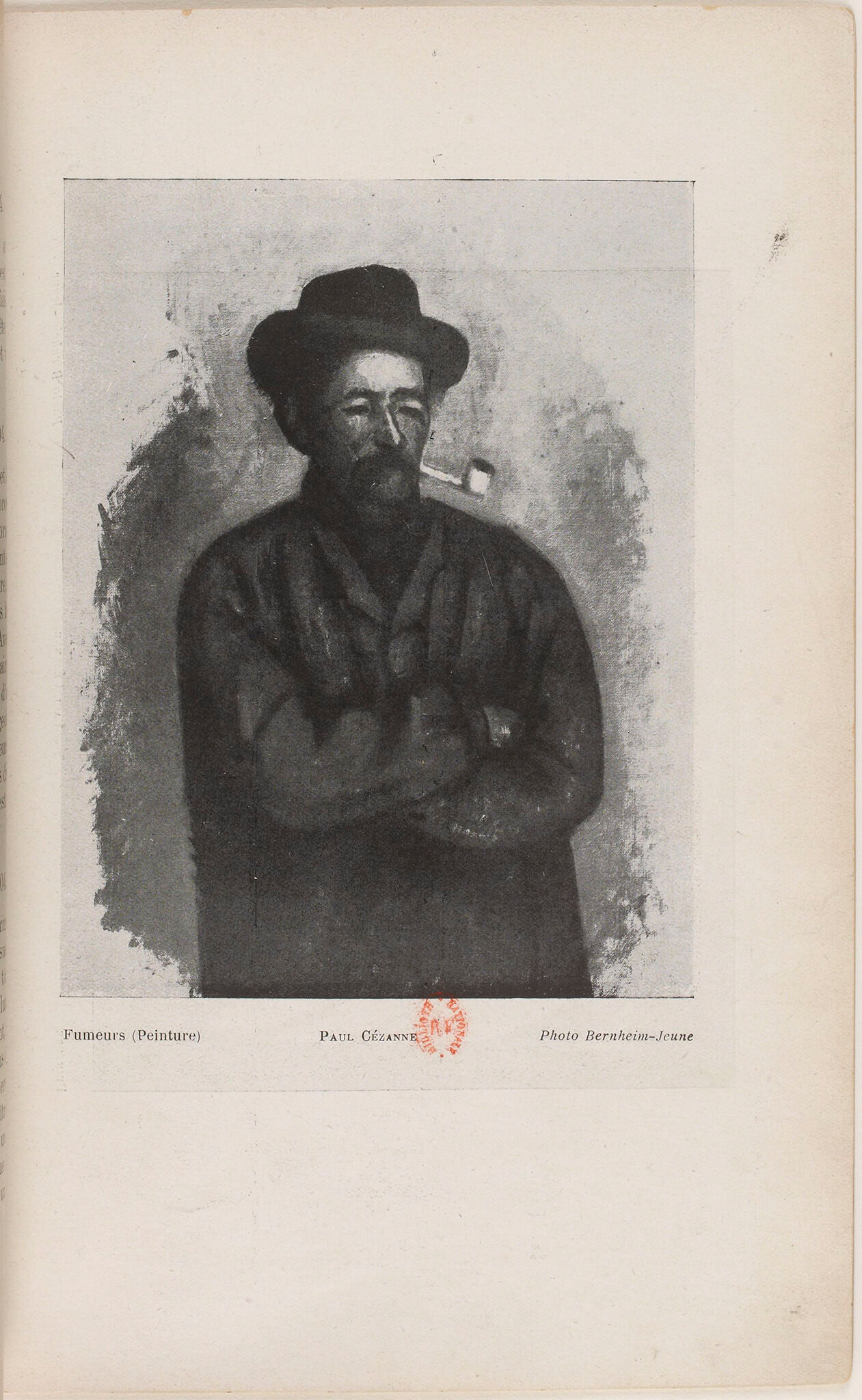

While the absence of color in the Esprit nouveau illustration might be perceived as a shortcoming, the journal’s photomechanical process of reproduction unwittingly called attention to the picture’s titular prop by exaggerating the tonal contrast between Père Alexandre’s coat and his white clay pipe. Smoking was an activity that Cezanne indulged in regularly, especially in the company of his friend, the then-aspiring journalist Émile Zola (1840–1902). In an 1861 letter to their mutual friend Baptistin Baille, Zola described Cezanne’s recent visit to him in Paris: “We went to lunch together, smoked a good many pipes in a good many public gardens, and I left him.”10Émile Zola to Baptistin Baille, April 22, 1861, in Danchev, The Letters of Paul Cézanne, 106. Similarly, when Cezanne vacationed with Zola’s family in Bennecourt during the summer of 1866, he and Zola lounged on hay bales and “smoked pipes while contemplating the moon.”11John Rewald, Paul Cézanne: A Biography, trans. Margaret H. Liebman (1948; repr. New York: Schocken Books, 1968), 60. This shared pastime may have inspired Cezanne to incorporate smoking figures into several early paintings, such as Luncheon on the Grass (ca. 1870; private collection, New York) and Pastorale (1870; Musée d’Orsay, Paris). Mary Louise Krumrine has also identified a sketch of a standing smoker (1864–67; Kunstmuseum Basel) as a self-portrait of Cezanne.12Mary Louise Krumrine, Paul Cézanne: The Bathers, exh. cat. (Basel: Museum of Fine Arts, 1990), 44. The drawing appears as the central vignette on a page of sketches; see p. 43, fig. 21.

In the Nelson-Atkins painting, Père Alexandre is shown smoking not his own pipe, but rather one used as a prop by Cezanne. Preserved to this day at Les Lauves, the pipe appears in three twentieth-century inventories of Cezanne’s atelier as the “pipe en terre blanche de Saint-Quentin” (white clay pipe from Saint-Quentin).13Michel Fraisset, Les vies silencieuses de Cézanne (Aix-en-Provence: Office du Tourisme, 1999), unpaginated. The inventories were conducted in 1954, 1969, and 1998, and the pipe appears as nos. 177, 98, and 172, respectively. Located near the Pont du Gard in southern France, the clay-rich village of Saint-Quentin-la-Poterie has been known for its production of ceramic pottery and pipes since the Middle Ages. This local industry reached its apogee in the nineteenth century, when more than eighty studios were manufacturing utilitarian ceramic wares, so it is unsurprising that Cezanne’s pipe came from this region.14For more on the Saint-Quentin ceramics industry, see the website of the Musée de la poterie Méditerranéenne, https://www.musee-poterie-mediterranee.com/#collections/saintquentin.

Most of the scholarly discussion surrounding the pipes in Cezanne’s multifigure Card Players paintings has focused on their arrangement on the wall, the relationship of the unused pipe on the table to the discarded cards, and the significance of pipe smoking as a practice that either induces reverie or promotes male homosociality. For example, Satish Padiyar has argued that “within a nineteenth-century bourgeois patriarchal regime [tobacco] facilitates an exchange between men that, ultimately, transmogrifies a world without women.”15Satish Padiyar, “Building a World Without Men (or Cézanne with Arendt),” in Satish Padiyar, ed., Modernist Games: Cézanne and His Card Players (London: Courtauld Institute of Art, 2013), 141. Male camaraderie is a moot point, however, in Man with a Pipe. Detached from any narrative context, Père Alexandre is alone with his thoughts. Here, the pipe functions primarily as a marker of class. Whereas cigar smoking was associated with the upper classes during the nineteenth century, pipe smoking was generally considered a working-class habit. This entrenched stereotype survived well into the twentieth century, both within and outside France, as demonstrated by a dialogue in the Netflix historical drama The Crown. Seeking to counter the perception that he is “an academic, a privileged Oxford don,” Prime Minister Harold Wilson, played by English actor Jason Watkins, changes his smoking routine. As he explains to Queen Elizabeth II:

I don’t like pipe smoking. I far prefer cigars. But cigars are a symbol of capitalist privilege. So, I smoke a pipe, on the campaign trail and on television. Makes me more . . . approachable. Likeable. We can’t be everything to everyone and still be true to ourselves.16The Crown, Season 3, Episode 3, “Aberfan,” directed by Benjamin Caron, 55:09, aired November 17, 2019, on Netflix.

Wilson’s efforts to connect with blue-collar voters by foregoing his Cubans in public attests to the strong class connotations of each mode of smoking.17Although the conversation between Wilson and the Queen was surely fictionalized, the substance of their dialogue is historically accurate. Pipes became something of a personal trademark for Wilson, and today his pipes are valued as collectors’ items. For example, the Derbyshire-based auctioneer Hanson sold several of Wilson’s pipes in May 2019; see “Harold Wilson’s Pipes and Cigars Set for Auction,” Belfast Telegraph, May 1, 2019.

Cezanne, who himself oscillated between smoking pipes and cigars, was undoubtedly aware of these affiliations.18In a letter to Zola dated June 20, 1859, Cezanne wrote: “My word, mon vieux [old boy], your cigars are excellent, I’m smoking one as I write; they taste of caramel and barley sugar.” See Danchev, The Letters of Paul Cezanne, 80. Linda Nochlin, in a guest lecture delivered at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln in 1996, argued that “the representation of class is simply inseparable from Cézanne’s phenomenology of appearances.”19Nochlin’s lecture was published as Linda Nochlin, Cézanne’s Portraits (Lincoln: College of Fine and Performing Arts, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, 1996), 24. Through an extended analysis of Cezanne’s Seated Peasant (ca. 1900; Musée d’Orsay, Paris), Nochlin demonstrated that the sitter’s clothing, body type, and facial expression together convey his station in life.20Nochlin, Cézanne’s Portraits, 20–24. The same could be said of Père Alexandre in Man with a Pipe. Not only his pipe but also his heavyweight jacket, broad trunk, and serious countenance suggest a self-reliant ouvrier (worker) who tills the land for a living. Streaks of vermilion on both cheekbones also highlight the sitter’s frequent exposure to the sun.

Cezanne, too, spent much time outdoors painting en plein airen plein air (adjective: plein-air): French for “outdoors.” The term is used to describe the act of painting quickly outside rather than in a studio., but he belonged to a different stratum of society than his models, and his biographers have often overstated his feelings of solidarity with them.21Cezanne’s family belonged to the upper middle class, thanks to his father’s successful banking firm in Aix-en-Provence. When the latter died in 1886, Cezanne received a substantial inheritance. See Danchev, Cézanne: A Life, 48–49, 266. Jack Lindsay, for example, claimed:

In the peasant-labourers of the Cardplayers, above all, he made his most powerful and subtle renderings of people. This was no accident. He could enter into these men—into their bodies and their habitual gestures, their way of standing and sitting, and so, ultimately, into their minds—as into nobody else.22Jack Lindsay, Cézanne: His Life and Art (Greenwich: New York Graphic Society, 1969), 276.

Lindsay’s romanticized language elides the class differences between Cezanne and his sitters and glosses over the transactional nature of their relationship. Cezanne paid Père Alexandre and other farmhands from the Jas de Bouffan five francs per posing session.23This figure reflects the testimony of Léontine Paulet, whose father, a gardener at the Jas de Bouffan, posed for Cezanne’s Card Players series. Paulet herself also sat for Cezanne as a child. See Danchev, Cézanne: A Life, 361. Although the artist depicted his working-class models less sentimentally than did many Salon painters, he ultimately treated them as employees, not closer acquaintances.24For example, Ireson and Wright point out that Cezanne never mentioned his models by name in his letters. See Ireson and Wright, Cézanne’s Card Players, 23.

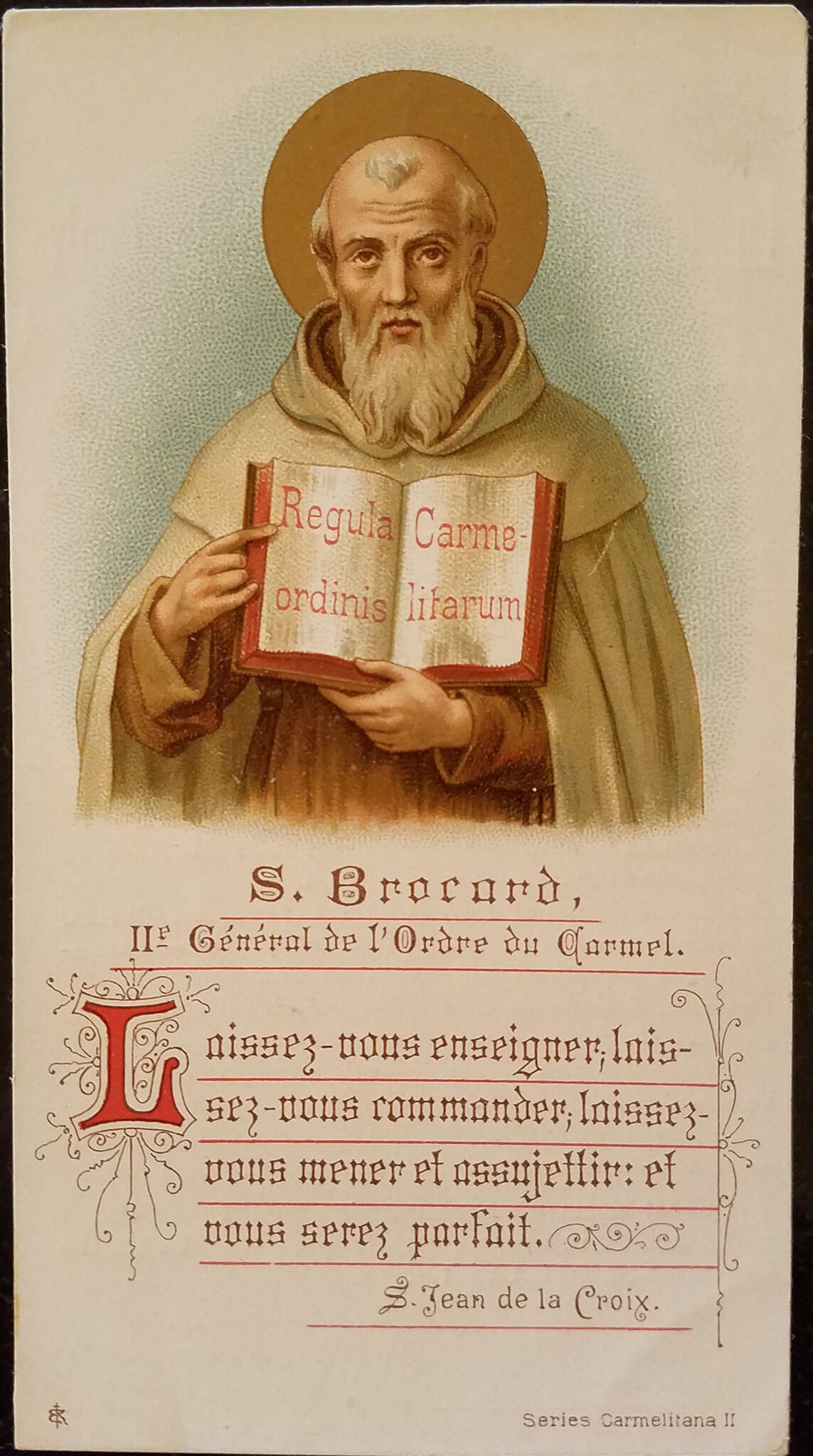

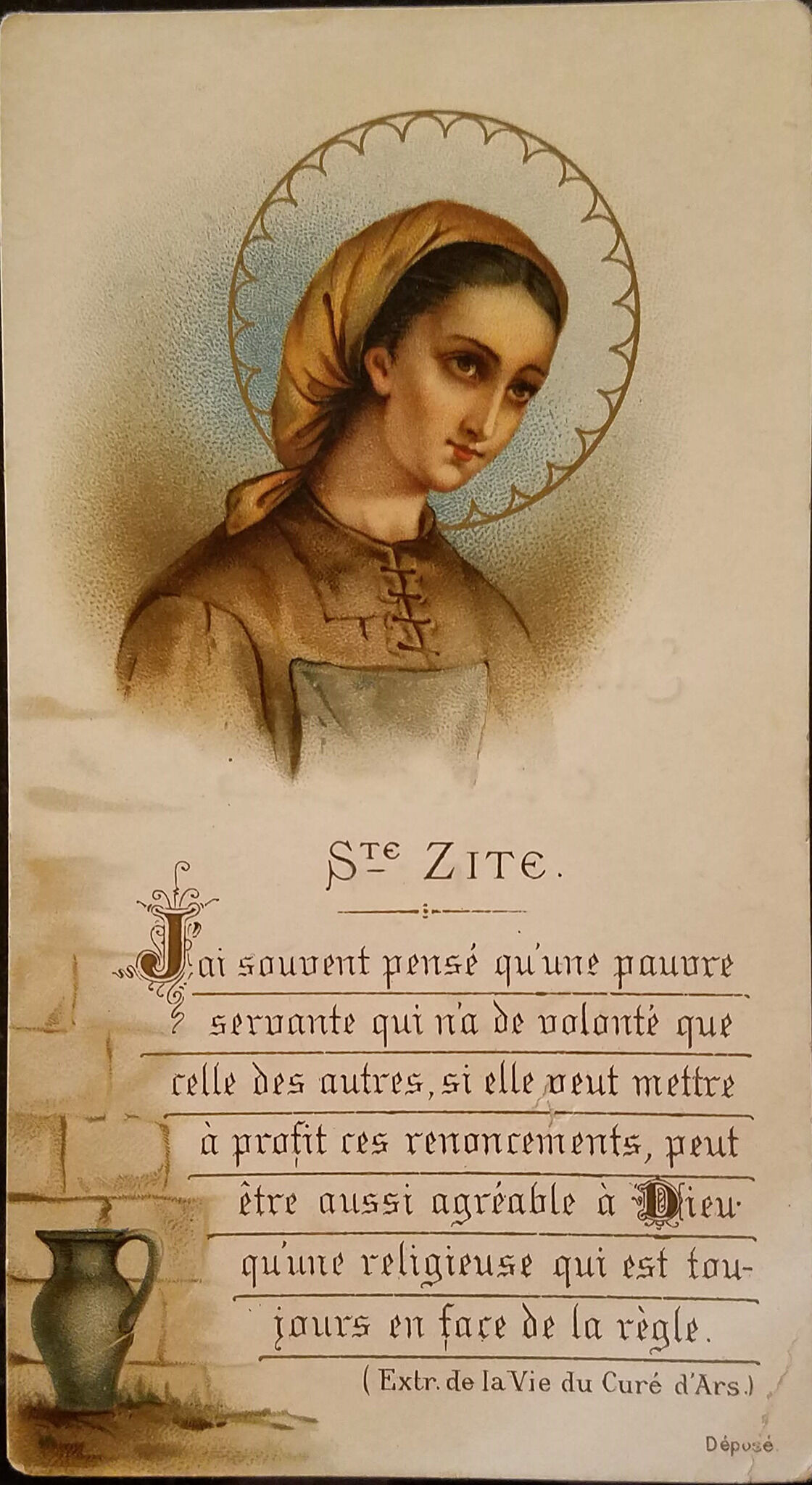

Lindsay’s rhetoric, despite its hyperbole, picks up on the aura of sacramentality suffusing Cezanne’s Card Players series, which many historians have noted but struggled to define. For instance, Theodore Reff described the figures as partaking in “a kind of ceremony or ritual.”25Theodore Reff, “Cézanne’s ‘Cardplayers’ and their Sources,” Arts Magazine 55, no. 3 (November 1980): 105. Man with a Pipe has a pseudo-spiritual ambience as well, perhaps due to its formal resemblance to Catholic holy cards.26My sincere thanks to the Reverend Eugene Carrella for allowing me to peruse his vast collection of holy cards, many of which were on view in Images of Sanctity: Holy Cards of the Catholic Church, 1800 to the Present, an exhibition organized by the Archdiocese of New York. See http://omeka.archnyarchives.org/exhibits/show/holycards/history for more details. While André Dombrowski has compared Cezanne’s standing smoker to a face card, such as a jack, no one has previously proposed these portable, pocket-size devotional cards as a possible source for Cezanne’s representation of Père Alexandre.27André Dombrowski, “The Cut and Shuffle: Card Playing in Cézanne’s Card Players,” in Padiyar, Modernist Games, 49. Cards depicting saints, the Virgin Mary, and other venerated persons were widely and cheaply available across Europe during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Cezanne, as a cradle Catholic who attended mass at the Cathedral of Saint Sauveur in Aix-en-Provence, solemnized his marriage at the Church of Saint Jean-Baptiste near the Jas de Bouffan, and painted religious subject matter, would certainly have been aware of these cards and probably owned some himself.28When Ambroise Vollard visited Cezanne in Aix-en-Provence, the artist gave his dealer a personal tour of the Church of Saint Sauveur—a telling indication of its importance to him. See Ambroise Vollard, Cézanne, trans. Harold L. Van Doren (1937; New York: Dover, 1984), 74.

Fig. 4. Holy card of Saint Brocard produced by Typ. Jos. Majoor fils in Antwerp, Belgium, 1909, color lithograph on cardstock, 5 x 2 11/16 in. (12.7 x 6.8 cm), collection of the Reverend Eugene Carrella, Staten Island; image courtesy of the author

Fig. 4. Holy card of Saint Brocard produced by Typ. Jos. Majoor fils in Antwerp, Belgium, 1909, color lithograph on cardstock, 5 x 2 11/16 in. (12.7 x 6.8 cm), collection of the Reverend Eugene Carrella, Staten Island; image courtesy of the author

Fig. 5. Holy card of Saint Zita produced by the Monastère de la Trappe de Notre Dame d’Aiguebelle in Drôme, France, late nineteenth century, color lithograph on cardstock, 5 1/8 x 2 13/16 in. (13 x 7.1 cm), collection of the Reverend Eugene Carrella, Staten Island; image courtesy of the author

Fig. 5. Holy card of Saint Zita produced by the Monastère de la Trappe de Notre Dame d’Aiguebelle in Drôme, France, late nineteenth century, color lithograph on cardstock, 5 1/8 x 2 13/16 in. (13 x 7.1 cm), collection of the Reverend Eugene Carrella, Staten Island; image courtesy of the author

Notes

-

The deed of purchase is preserved in the Archives départementales des Bouches-du-Rhône, Marseille. For a transcription of this document, see Monsieur Paul Cezanne, rentier, artiste peintre: Un créateur au prisme des archives (Marseille: Archives départementales des Bouches-du-Rhône, 2006), 94–107.

-

After Cezanne’s father died in 1886, the Jas de Bouffan was jointly owned by Cezanne and his two siblings. When Cezanne’s mother passed away a decade later, his sister and her husband no longer wished to retain their shares, necessitating a sale. See Alex Danchev, Cézanne: A Life (New York: Pantheon Books, 2012), 322.

-

There are also three two-figure paintings in the Card Players series, in which this spectator does not appear.

-

See Ireson’s catalogue entry for Man with a Pipe in Nancy Ireson and Barnaby Wright, eds., Cézanne’s Card Players, exh. cat. (London: Courtauld Gallery, 2010), 103.

-

Cezanne to his son, Paul Cezanne, September 8, 1906, in Alex Danchev, ed. and trans., The Letters of Paul Cézanne (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2013), 370–71. Emphasis in the original.

-

Aviva Burnstock, Charlotte Hale, Caroline Campbell, and Gabriella Macaro, “Cézanne’s Development of the Card Players,” in Ireson and Wright, Cézanne’s Card Players, 39. Nothing is known of Père Alexandre’s life apart from his period of employment at the Jas de Bouffan. He later posed for Man in a Blue Smock, ca. 1896–97, oil on canvas, 32 1/16 x 25 1/2 in. (81.5 x 64.8 cm), Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, TX.

-

The exhibition ran January 10–22, 1910. For Apollinaire’s comments, see Guillaume Apollinaire, “Exposition Cézanne (Galerie Bernheim),” Paris-Journal, January 20, 1910, reprinted in Leroy C. Breunig, ed., Apollinaire on Art: Essays and Reviews, 1902–1918 (New York: Viking Press, 1972), 57.

-

In Rewald’s catalogue raisonné, the exhibition history for Man with a Pipe reads: “Salon d’Automne, Grand Palais, Paris, n.n. [no number]?” See John Rewald, The Paintings of Paul Cézanne: A Catalogue Raisonné (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1996), 1:443. Further research has not uncovered any evidence to support this claim. Per Jayne Warman, co-author of the online catalogue raisonné (http://www.cezannecatalogue.com), “The painting was not in the 1907 Grand Palais exhibition as far as I can tell.” See Jayne Warman to Brigid M. Boyle, June 2, 2015, NAMA curatorial files.

-

See H[ans] v[on] Wedderkop, “Paul Cézanne,” Der Cicerone 14, no. 16 (August 24, 1922): 690.

-

Émile Zola to Baptistin Baille, April 22, 1861, in Danchev, The Letters of Paul Cézanne, 106.

-

John Rewald, Paul Cézanne: A Biography, trans. Margaret H. Liebman (1948; repr. New York: Schocken Books, 1968), 60.

-

Mary Louise Krumrine, Paul Cézanne: The Bathers, exh. cat. (Basel: Museum of Fine Arts, 1990), 44. The drawing appears as the central vignette on a page of sketches; see p. 43, fig. 21.

-

Michel Fraisset, Les vies silencieuses de Cézanne (Aix-en-Provence: Office du Tourisme, 1999), unpaginated. The inventories were conducted in 1954, 1969, and 1998, and the pipe appears as nos. 177, 98, and 172, respectively.

-

For more on the Saint-Quentin ceramics industry, see the website of the Musée de la poterie Méditerranéenne, https://www.musee-poterie-mediterranee.com/#collections/saintquentin.

-

Satish Padiyar, “Building a World Without Men (or Cézanne with Arendt),” in Satish Padiyar, ed., Modernist Games: Cézanne and His Card Players (London: Courtauld Institute of Art, 2013), 141.

-

The Crown, Season 3, Episode 3, “Aberfan,” directed by Benjamin Caron, 55:09, aired November 17, 2019, on Netflix.

-

Although the conversation between Wilson and the Queen was surely fictionalized, the substance of their dialogue is historically accurate. Pipes became something of a personal trademark for Wilson, and today his pipes are valued as collectors’ items. For example, the Derbyshire-based auctioneer Hanson sold several of Wilson’s pipes in May 2019; see “Harold Wilson’s Pipes and Cigars Set for Auction,” Belfast Telegraph, May 1, 2019.

-

In a letter to Zola dated June 20, 1859, Cezanne wrote: “My word, mon vieux [old boy], your cigars are excellent, I’m smoking one as I write; they taste of caramel and barley sugar.” See Danchev, The Letters of Paul Cezanne, 80.

-

Nochlin’s lecture was published as Linda Nochlin, Cézanne’s Portraits (Lincoln: College of Fine and Performing Arts, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, 1996), 24.

-

Nochlin, Cézanne’s Portraits, 20–24.

-

Cezanne’s family belonged to the upper middle class, thanks to his father’s successful banking firm in Aix-en-Provence. When the latter died in 1886, Cezanne received a substantial inheritance. See Danchev, Cézanne: A Life, 48–49, 266.

-

Jack Lindsay, Cézanne: His Life and Art (Greenwich: New York Graphic Society, 1969), 276.

-

This figure reflects the testimony of Léontine Paulet, whose father, a gardener at the Jas de Bouffan, posed for Cezanne’s Card Players series. Paulet herself also sat for Cezanne as a child. See Danchev, Cézanne: A Life, 361.

-

For example, Ireson and Wright point out that Cezanne never mentioned his models by name in his letters. See Ireson and Wright, Cézanne’s Card Players, 23.

-

Theodore Reff, “Cézanne’s ‘Cardplayers’ and their Sources,” Arts Magazine 55, no. 3 (November 1980): 105.

-

My sincere thanks to the Reverend Eugene Carrella for allowing me to peruse his vast collection of holy cards, many of which were on view in Images of Sanctity: Holy Cards of the Catholic Church, 1800 to the Present, an exhibition organized by the Archdiocese of New York. See http://omeka.archnyarchives.org/exhibits/ show/holycards/history for more details.

-

André Dombrowski, “The Cut and Shuffle: Card Playing in Cézanne’s Card Players,” in Padiyar, Modernist Games, 49.

-

When Ambroise Vollard visited Cezanne in Aix-en-Provence, the artist gave his dealer a personal tour of the Church of Saint Sauveur—a telling indication of its importance to him. See Ambroise Vollard, Cézanne, trans. Harold L. Van Doren (1937; New York: Dover, 1984), 74.

-

For a representative sampling of these conventions, see Barbara Calamari and Sandra DiPasqua, Holy Cards (New York: Abrams, 2004).

-

Nina M. Athanassoglou-Kallmyer has pointed out that Père Alexandre’s headwear pairs oddly with his coat, since bowler hats were “more appropriate for a formal three-piece suit.” See Nina M. Athanassoglou-Kallmyer, Cézanne and Provence: The Painter in his Culture (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), 28. Perhaps this sartorial disaccord reflects Cezanne’s desire, conscious or not, to approximate a halo.

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Diana M. Jaskierny, “Paul Cezanne, Man with a Pipe, 1890–92,” technical entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.708.2088.

MLA:

Jaskierny, Diana M. “Paul Cezanne, Man with a Pipe, 1890–92,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.708.2088.

Man with a Pipe was painted as part of a series of studies in preparation for Paul Cezanne’s Card Players paintings (Figs. 1, 2). Executed on plain-weaveplain weave: A basic textile weave in which one weft thread alternates over and under the warp threads. Often this structure consists of one thread in each direction, but threads can be doubled (basket weave) or tripled to create more complex plain weave. Plain weave is sometimes called tabby weave. canvas, the original dimensions of the painting are unknown, as the tacking marginstacking margins: The outer edges of canvas that wrap around and are attached to the stretcher or strainer with tacks or staples. See also tacking edge. were removed, and the painting was resized during a lininglining: A procedure used to reinforce a weakened canvas that involves adhering a second fabric support using adhesive, most often a glue-paste mixture, wax, or synthetic adhesive. process predating its history at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Early publications erroneously list this painting as being 39 by 30 centimeters (15 3/8 by 11 13/16 inches), although these dimensions would have noticeably cropped the image.1The erroneous dimensions were first published in Lionello Venturi, Cézanne: Son art, son œuvre (Paris: Paul Rosenberg, 1936), no. 563, pp. 1:186–87. Additionally, there are no cracks or creases that would verify this size.

Instead, it appears that the original size likely corresponded with a no. 6 figure standard-format canvasstandard-format supports: Commercially prepared supports available through art suppliers, which gained popularity in the nineteenth century during the industrialization of art materials. Available in three formats figure (portrait), paysage (landscape), and marine (marine), these were numbered 1 through 120 to indicate their size. For each numbered size, marine and paysage had two options available: a larger format (haute) and smaller (basse) format.. Along the left edge of the picture planepicture plane: The two-dimensional surface where the artist applies paint., regularly spaced losses, now filled and inpainted, are presumably the original tack holes. Approximately six millimeters from the left edge, a near continuous vertical hairline crack is visible through microscope examination. Based on its proximity to the potential tack holes, this probably relates to the original turnover edgeturnover edge: The point at which the canvas begins to wrap around the stretcher, at the junction between the picture plane and tacking margin. See also foldover edge.. A similar horizontal crack is found near the top edge, just above where the blue background stops.2In addition to this horizontal hairline crack, it is safe to assume the horizontal end to the blue background relates to the original turnover edge. From the horizontal crack to the original bottom edge, and from the vertical crack to the right edge, the dimensions measure 41 by 33 centimeters,3Possible tacking holes are found only on the left side. Possible turnover cracks are found only on the top and left sides. Collectively, these features indicate that the painting may have been cut down at the turnover edges along the right and bottom sides. a no. 6 figure according to the Bourgeois Ainé catalogue from 1888.4David Bomford, Jo Kirby, John Leighton, and Ashok Roy, Art in the Making: Impressionism (London: Yale University Press, 1990), 46. Due to the lining, no supplier stamps are visible; however, Cezanne frequently purchased materials, including standard-format canvases, from a variety of artist suppliersartist supplier(s): Also called colormen and color merchants. Artist suppliers prepared materials for artists. This tradition dates back to the Medieval period, but the industrialization of the nineteenth century increased their commerce. It was during this time that ready-made paints in tubes, commercially prepared canvases, and standard-format supports were available to artists for sale through these suppliers. It is sometimes possible to identify the supplier from stamps or labels found on the reverse of the artwork. See also canvas stamp, supplier mark, and *color merchant..5Elisabeth Reissner, “Ways of Making: Practice and Innovation in Cézanne’s Paintings in the National Gallery,” National Gallery Technical Bulletin 25 (2008): 6–8.

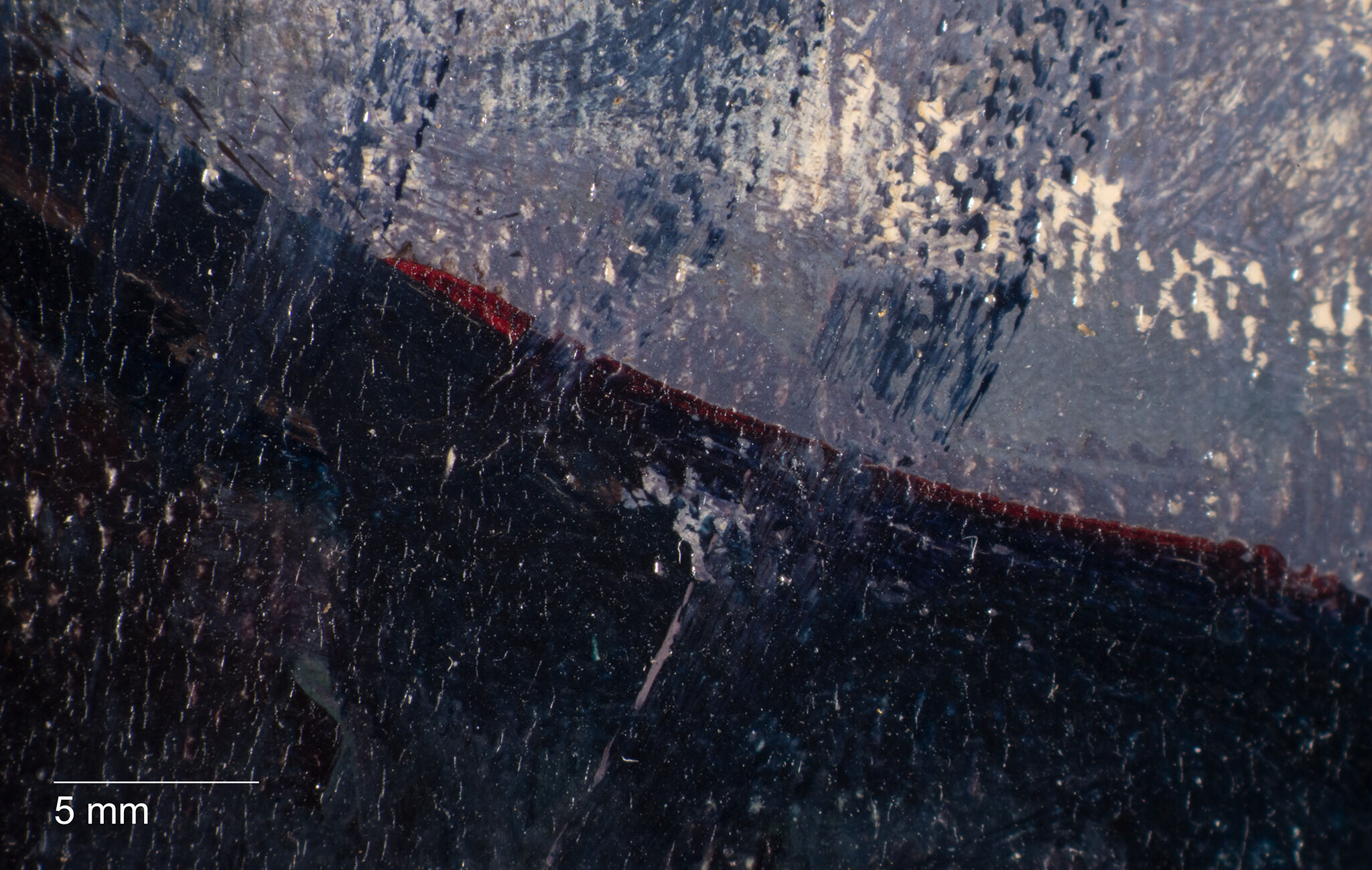

Fig. 6. Photomicrograph with white arrows pointing to a possible dilute blue painted underdrawing, visible beneath an upper dark blue stroke, Man with a Pipe (1890–92)

Fig. 6. Photomicrograph with white arrows pointing to a possible dilute blue painted underdrawing, visible beneath an upper dark blue stroke, Man with a Pipe (1890–92)

Fig. 7. Detail of the lapel with arrows pointing to a possible underdrawing beneath the coat, Man with a Pipe (1890–92)

Fig. 7. Detail of the lapel with arrows pointing to a possible underdrawing beneath the coat, Man with a Pipe (1890–92)

When examining the painting with infrared reflectographyinfrared reflectography (IRR): A form of infrared imaging that exploits the behavior of painting materials at wavelengths beyond those accessible to infrared photography. These advantages sometimes include a continuing increase in the transparency of pigments beyond wavelengths accessible to infrared photography (i.e, beyond 1,000 nanometers), rendering underdrawing more clearly. The resulting image is called an infrared reflectogram. Devices that came into common use in the 1980s such as the infrared vidicon effectively revealed these features but suffered from lack of sharpness and uneven response. Vidicons continue to be used out to 2,200 nanometers but several newer pixelated detectors including indium gallium arsenide and indium antimonide array detectors offer improvements. All of these devices are optimally used with filters constraining their response to those parts of the infrared spectrum that reveal the most within the constraints of the palette used for a given painting. They can be used for transmitted light imaging as well as in reflection. for the presence of an underdrawingunderdrawing: A drawn or painted sketch beneath the paint layer. The underdrawing can be made from dry materials, such as graphite or charcoal, or wet materials, such as ink or paint., none was found. This, however, only indicates that any underdrawing present is not carbon-based. Through examination with a stereomicroscope, a possible painted underdrawing was identified. Within the brown shirt, in two skips of paint, a thin, dilute, blue line is visible, extending under the surrounding paint (Fig. 6). Assuming this is a portion of the underdrawing, the extent of this drawing is uncertain, as there are few skips in paint along the edges of the figure where one would expect to find a drawing, and no other conclusive examples were found. Within the shirt lapel, a thin, straight line is also visible where the lapel would be present beneath the blue coat; however, it is unclear if this is composed of the same dilute paint (Fig. 7).7Technical examinations of the Cezannes at the National Gallery, London, revealed that regardless of whether a dry drawing medium is present, his paintings frequently include a painted drawing using a dilute blue paint. Reissner, “Ways of Making: Practice and Innovation in Cézanne’s Paintings in the National Gallery,” 14–15.

Fig. 8. Detail of the figure’s proper left side where the ground layer is most visible through the thinly applied paint layer, Man with a Pipe (1890–92)

Fig. 8. Detail of the figure’s proper left side where the ground layer is most visible through the thinly applied paint layer, Man with a Pipe (1890–92)

Fig. 9. Detail of colors and brushwork in the left side background, Man with a Pipe (1890–92)

Fig. 9. Detail of colors and brushwork in the left side background, Man with a Pipe (1890–92)

Fig. 11. Detail of the face with directional brushstrokes forming the volume of the head, Man with a Pipe (1890–92)

Fig. 11. Detail of the face with directional brushstrokes forming the volume of the head, Man with a Pipe (1890–92)

Fig. 12. Detail of the hat with vertical brushstrokes, Man with a Pipe (1890–92)

Fig. 12. Detail of the hat with vertical brushstrokes, Man with a Pipe (1890–92)

The painting is in overall good condition. The current glue-paste lining was completed prior to the painting’s acquisition at the Nelson-Atkins. In 1993, the painting was cleaned, and inpainting was completed.11Scott Heffley, February 12, 1993, treatment report, NAMA conservation file, 2015.13.6. Based on examination with ultraviolet (UV) radiationultraviolet (UV) radiation: A segment of the electromagnetic spectrum, just beyond the sensitivity of the human eye, with wavelengths ranging from 100–400 nanometers. For a description of its use in the study of art objects, see ultraviolet (UV) fluorescence or UV-induced visible fluorescence., a moderate amount of retouchingretouching: Paint application by a conservator or restorer to cover losses and unify the original composition. Retouching is an aspect of conservation treatment that is aesthetic in nature and that differs from more limited procedures undertaken solely to stabilize original material. Sometimes referred to as inpainting or retouch. is present on the cream ground layer. Extensive retouching is present at a few millimeters along the top and bottom edges; however, these are extensions to the picture plane related to the lining process.

Notes

-

The erroneous dimensions were first published in Lionello Venturi, Cézanne: Son art, son œuvre (Paris: Paul Rosenberg, 1936), no. 563, pp. 1:186–87. Additionally, there are no cracks or creases that would verify this size.

-

In addition to this horizontal hairline crack, it is safe to assume the horizontal end to the blue background relates to the original turnover edge.

-

Possible tacking holes are found only on the left side. Possible turnover cracks are found only on the top and left sides. Collectively, these features indicate that the painting may have been cut down at the turnover edges along the right and bottom sides.

-

David Bomford, Jo Kirby, John Leighton, and Ashok Roy, Art in the Making: Impressionism (London: Yale University Press, 1990), 46.

-

Elisabeth Reissner, “Ways of Making: Practice and Innovation in Cézanne’s Paintings in the National Gallery,” National Gallery Technical Bulletin 25 (2008): 6–8.

-

Nancy Ireson and Barnaby Wright, eds., Cézanne’s Card Players, exh. cat. (London: Courtauld Gallery, 2010), 104–07.

-

Technical examinations of the Cezannes at the National Gallery, London, revealed that regardless of whether a dry drawing medium is present, his paintings frequently include a painted drawing using a dilute blue paint. Reissner, “Ways of Making: Practice and Innovation in Cézanne’s Paintings in the National Gallery,” 14–15.

-

Within the figures of Large Bathers (1898–1905; National Gallery, London), variations of opaque and thin scumbles revealing the luminous ground layer can be found. Anthea Callen, Techniques of the Impressionists (London: Tiger Books International, 1990), 172.

-

Cezanne frequently used a dark blue paint to outline his compositional elements; however, other colors, namely reds, greens, and purples, have also been identified in his outlines. Elisabeth Reissner, “Transparency of Means: ‘Drawing’ and Colour in Cézanne’s Watercolours and Oil Paintings in The Courtauld Gallery,” in The Courtauld Cézannes, ed. Stephanie Buck, John House, Ernst Vegelin van Claerbergen, and Barnaby Wright, exh. cat. (London: Courtauld Gallery, 2008), 54.

-

Erle Loran, Cézanne’s Composition: Analysis of His Form with Diagrams and Photographs of His Motifs (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006), 10.

-

Scott Heffley, February 12, 1993, treatment report, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, 2015.13.6.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Paul Cezanne, Man with a Pipe, 1890–92,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.708.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Paul Cezanne, Man with a Pipe, 1890–92,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.708.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Paul Cezanne, Man with a Pipe, 1890–92,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.708.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Paul Cezanne, Man with a Pipe, 1890–92,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.708.4033.

Paul Cezanne (1839–1906), Aix-en-Provence, 1890/1892–no later than December 1899;

Purchased from Cezanne by Ambroise Vollard, Paris, stock book A, no. 3526, as Étude d’homme debout fumant sa pipe, and stock book B, no. 4215, as Homme fumant une pipe, by December 1899–September 21, 1905 [1];

Purchased from Vollard by the Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, Paris, no. 15116, as Le petit fumeur, 1905–March 8, 1907 [2];

Purchased from the Galerie Bernheim-Jeune by Louis Bernard (1886–1916), probably France, 1907–September 17, 1916 [3];

Bernard’s estate, September 17–29, 1916;

Purchased from Bernard’s estate by the Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, Paris, no. 20632, as Le fumeur, September 29–October 7, 1916 [4];

Purchased from the Galerie Bernheim-Jeune by the Galerie Georges Bernheim, Paris, October 7, 1916–no later than 1917;

Bought back from the Galerie Georges Bernheim by the Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, Paris, by December 31, 1917;

Transferred from the Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, Paris, to the Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, Lausanne, December 31, 1917 [5];

Probably purchased from the Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, Lausanne, by Auguste Pellerin (1852–1929), Paris, by 1923–October 18, 1929 [6];

By descent to his daughter, Juliette Lecomte (née Pellerin, 1893–1987), Paris, 1929–March 20, 1987 [7];

By descent to Lecomte’s heirs, Paris, 1987–November 30, 1992;

Purchased from the latter at Impressionist and Modern Paintings and Watercolours: Including Seven Cézanne Paintings from the Auguste Pellerin Collection, Christie’s, London, November 30, 1992, lot 16, as L’Homme à la Pipe, by Marion (née Helzberg, 1931–2013) and Henry (1922–2019) Bloch, Shawnee Mission, KS, 1992–June 15, 2015;

Their gift to The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 2015.

Notes

[1] A Vollard label preserved on the stretcher says “4215.” Few of the entries in Vollard stock book A are dated, but three entries preceding no. 3526 (that is, nos. 3310, 3505, and 3506) bear dates ranging from July to October 1899. Following no. 3526, the first dates to appear in the stock book are December 1899 and February 1900 (for nos. 3551 and 3553, respectively). Thus, Man with a Pipe was likely purchased between October and December of 1899. See email from Jayne Warman, independent art historian, to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, June 4, 2015, NAMA curatorial files.

For the sale date of September 21, 1905 to the Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, see letter from Guy-Patrice Dauberville, Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, to Caitlin Robinson, NAMA, July 21, 2004, NAMA curatorial files.

[2] A Galerie Bernheim-Jeune label preserved on the backing board reads: “Nº 15116 / Cézanne / Portrait d’ouvrier.” A second Bernheim-Jeune label, also preserved on the backing board, reads: “Nº 15116 / Cézanne / Petit fumeur.” The same stock number appears as a handwritten inscription on the stretcher.

For the sale date of March 8, 1907 to Louis Bernard, see letter from Guy-Patrice Dauberville, Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, to Caitlin Robinson, NAMA, July 21, 2004, NAMA curatorial files.

[3] Bernard passed away on September 17, 1916.

[4] A Galerie Bernheim-Jeune label preserved on the backing board reads: “Nº 20632 / Cézanne / Le Fumeur.” The same stock number appears as a handwritten inscription on the stretcher. For the purchase date of September 29, 1916, see letter from Guy-Patrice Dauberville, Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, to Caitlin Robinson, NAMA, July 21, 2004, NAMA curatorial files. For the sale date of October 7, 1916 to the Galerie Georges Bernheim, see emails from Jayne Warman, independent art historian, to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, June 4, 2015 and August 21, 2020, NAMA curatorial files.

[5] For the transfer date of December 31, 1917, see letter from Guy-Patrice Dauberville, Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, to Caitlin Robinson, NAMA, July 21, 2004, NAMA curatorial files. According to Jayne Warman, the Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, Paris, transferred many paintings to its Lausanne branch during World War I. See email from Jayne Warman, independent art historian, to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, June 4, 2015, NAMA curatorial files.

[6] The first publication to cite Pellerin as the owner is Georges Rivière, Le maître Paul Cézanne (Paris: H. Floury, 1923), 217. Inscriptions preserved on the canvas and stretcher say “Escalier” (staircase). Auguste Pellerin hung the painting in a stairwell in his mansion; see email from Jayne Warman, independent art historian, to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, June 2, 2015, NAMA curatorial files. Pellerin passed away on October 18, 1929.

[7] Pellerin bequeathed his collection of ninety-two paintings to his children. His son, Jean-Victor Pellerin, received forty-five, and his daughter, Juliette Lecomte (née Pellerin), received forty-seven. See Françoise Cachin et al., Cézanne, exh. cat. (Paris: Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 1995), 573. Lecomte passed away on March 20, 1987.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Paul Cezanne, Man with a Pipe, 1890–92,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.708.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Paul Cezanne, Man with a Pipe, 1890–92,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.708.4033.

Paul Cezanne, The Card Players, ca. 1890–92, oil on canvas, 25 3/4 x 32 1/4 in. (65.4 x 81.9 cm), The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Paul Cezanne, The Card Players, ca. 1890–92, oil on canvas, 53 1/4 x 71 5/8 in. (135.3 x 181.9 cm), The Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Paul Cezanne, Man with a Pipe, 1890–92,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.708.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Paul Cezanne, Man with a Pipe, 1890–92,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.708.4033.

Hommage à Cézanne, Musée National de l’Orangerie des Tuileries, Paris, July 2–October 17, 1954, no. 58, as L’Homme à la pipe.

Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, June 9–September 9, 2007, no. 24, as Man with a Pipe (L’homme à la pipe).

Cézanne’s Card Players, The Courtauld Gallery, London, October 21, 2010–January 16, 2011; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, February 9–May 8, 2011, no. 3, as Man with a Pipe.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Paul Cezanne, Man with a Pipe, 1890–92,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.708.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Paul Cezanne, Man with a Pipe, 1890–92,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.708.4033.

“Lettres de Cézanne,” L’Esprit Nouveau, no. 2 (1920): 135, (repro.), as Fumeurs.

H[ans] v[on] Wedderkop, “Paul Cézanne,” Der Cicerone 14, no. 16 (August 24, 1922): xi, 690, (repro.), as Mann mit Pfeife.

H[ans] von Wedderkop, Paul Cézanne (Leipzig: Verlag von Klinkhardt und Biermann, 1922), (repro.), as Mann mit Pfeife.

Georges Rivière, Le maître Paul Cézanne (Paris: H. Floury, 1923), 217, as L’Homme à la pipe.

Maurice Raynal, Cézanne (Paris: Éditions de Cluny, 1936), 54, 145, (repro.), as L’Homme à la pipe.

Lionello Venturi, Cézanne: Son art, son œuvre (Paris: Paul Rosenberg, 1936), no. 563, pp. 1:186–87, 403; 2:(repro.), as L’Homme à la pipe.

John Rewald, “À propos du catalogue raisonné de l’œuvre de Paul Cézanne et de la chronologie de cette œuvre,” La Renaissance 20, nos. 3–4 (March–April 1937): 54.

Bernard Dorival, Cézanne (Paris: Éditions Pierre Tisné, 1948), 62, as Homme à la pipe.

Liliane Guerry, Cézanne et l’expression de l’espace (Paris: Flammarion, 1950), 104, 196n61, as l’Homme à la pipe.

Robert Rey, “Cézanne,” La Revue des arts 4 no. 2 (June 1954): 76, (repro.), as L’Homme à la pipe.

Hommage à Cézanne, exh. cat. (Paris: Éditions des Musées Nationaux, 1954), 23, as L’Homme à la pipe.

Frank Elgar, “Les Arts: Hommage à Cézanne,” Carrefour, no. 512 (July 7, 1954): 8, as L’Homme à la pipe.

Douglas Cooper, “Two Cézanne Exhibitions: II,” Burlington Magazine 96, no. 621 (December 1954): 380, as L’Homme à la Pipe.

Kurt Badt, The Art of Cézanne, trans. Sheila Ann Ogilvie (1956; Berkeley: University of California Press, 1965), 89, 119, 122, 129n30.

Alfred Neumeyer, Cézanne: Drawings (New York: Thomas Yoseloff, 1958), 47–48.

Adrien Chappuis, Les dessins de Paul Cézanne au Cabinet des Estampes du Musée des Beaux-Arts de Bâle (Olten: Éditions Urs Graf, 1962), 95.

Possibly Richard W. Murphy, The World of Cézanne: 1839–1906 (New York: Time-Life Books, 1968), 119, as Man Smoking a Pipe.

Wayne Andersen, Cézanne’s Portrait Drawings (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1970), 37, 43n2, 230.

Sandra Orienti, L’opera completa di Cézanne (Milan: Rizzoli, 1970), no. 631, pp. 112, 114–15, 125, 127, (repro.), as Uomo con pipa a braccia conserte.

Sandra Orienti, The Complete Paintings of Cézanne (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1972), no. 631, pp. 112, 114–15, 125–26, (repro.), as Man with a Pipe and Folded Arms.

Sandra Orienti, Tout l’œuvre peint de Cézanne (Paris: Flammarion, 1975), no. 631, pp. 112, 115, 125–26, (repro.), as L’Homme à la pipe.

William Rubin, ed., Cézanne: The Late Work, exh. cat. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1977), 21.

Theodore Reff, “Cézanne’s ‘Cardplayers’ and their Sources,” Arts Magazine 55, no. 3 (November 1980): 104, 116n4.

Lionello Venturi, Cézanne: Son art, son oeuvre (San Francisco: Alan Wofsy Fine Arts, 1989), no. 563, pp. 1:186–87, 403; 2:(repro.), as L’homme à la pipe.

Mary Louise Krumrine, Cézanne: The Bathers, exh. cat. (Basel: Museum of Fine Arts, 1990), 260n31, as L’Homme à la pipe.

John Shaw, “Auction houses get Impressionist sales off to fine art,” Times (London), no. 64,445 (September 23, 1992): 16, (repro.), as L’homme à la pipe.

Carol Vogel, “The Art Market,” New York Times 142, no. 49,100 (September 25, 1992): C27, as Man With a Pipe.

Impressionist and Modern Paintings and Watercolours: Including Seven Cézanne Paintings from the Auguste Pellerin Collection (London: Christie, Manson and Woods, 1992), 42–43, (repro.), as L’Homme à la Pipe.

James Roundell, The Auguste Pellerin Collection ([London: Christie, Manson and Woods], 1992), 10, (repro.), as L’Homme à la Pipe.

Seven Cézanne Paintings from the Auguste Pellerin Collection (London: Christie, Manson and Woods, 1992), 46–49, (repro.), as L’Homme à la Pipe.

Georgina Adam, “Buyers crowd £10.78m sale of Cezannes,” Daily Telegraph (London) (December 1, 1992): (repro.), as L’Homme à la Pipe.

Dayla Alberge, “Dealers seize on chance to buy rare works by Cézanne,” Independent (London), no. 1911 (December 1, 1992): 2, (repro.), as The Man Smoking a Pipe.

“Paintings fetch £11m,” Guardian (London and Manchester) (December 1, 1992): 3.

“Cezanne Works Sell for Less Than Expected at Auction,” Wall Street Journal (Europe) (December 2, 1992): 9, as Homme a [sic] la Pipe.

Susan Moore, “Pellerin Cézannes sell well,” Financial Times (London), no. 31,529 (December 2, 1992): 12, as L’Homme à la Pipe.

Carol Vogel, “The Art Market,” New York Times 142, no. 49,170 (December 4, 1992): C6, (repro.), as Man With a Pipe.

Souren Melikian, “A Cautious Revival in Impressionist Market,” International Herald Tribune (December 5–6, 1992): 7, (repro.).

Souren Melikian, “A Born-Again Art Market,” Art and Auction (February 1993): 54, (repro.), as L’homme à la pipe.

Antony Thorncroft, “Report from London: Two Steps Forward,” Art and Auction (February 1993): 66, as L’homme à la pipe.

“Art Notes,” Kansas City Star 113, no. 171 (March 7, 1993): K-8, as Man With a Pipe.

“Gemälde und Zeichnungen,” Kunstpreis Jahrbuch 48, no. 1 (1993): 378, (repro.), as Mann mit Pfeife.

Cézanne: Gemälde; Meisterwerke aus vier Jahrzehnten ([Tübingen, Germany: Kunsthalle Tübingen, 1993]), unpaginated, as Man mitt Pfeife and Homme à la pipe.

Francis Russell, ed., Christie’s Review of the Season (London: Christie, Manson and Woods, 1993), 82–83, (repro.), L’Homme à la Pipe.

Françoise Cachin et al., Cézanne, exh. cat. (1995; New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1996), 341, 345.

John Rewald, The Paintings of Paul Cézanne: A Catalogue Raisonné (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1996), no. 705, pp. 1:10, 409, 443, 561, 563, 570, 573, 576–79; 2:242, (repro.), as L’Homme à la Pipe.

Françoise Cachin, Henri Loyrette, and Stéphane Guégan, eds., Cézanne aujourd’hui: Actes du colloque organisé par le musée d’Orsay, 29 et 30 novembre 1995 (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 1997), 65n2.

Michel Fraisset, Les vies silencieuses de Cézanne (Aix-en-Provence: Office du Tourisme, 1999), (repro.), as L’homme à la pipe.

Rebecca Dimling Cochran and Bobbie Leigh, “100 Top Collectors who have made a difference,” Art and Antiques 28, no. 3 (March 2006): 90, as The Pipe Smoker.

Bobbie Leigh, “Magnificent Obsession,” Art and Antiques 28, no. 6 (June 2006): 62–63, 65, (repro.), as Man with a Pipe.

“Inaugural Exhibitions Celebrate Kansas City,” Member Magazine (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (Fall 2006): 3.

Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 12, 15–16, 128–31, 161, (repro.), as Man with a Pipe (L’homme à la pipe).

Alice Thorson, “First Public Exhibition: Marion and Henry Bloch’s Art Collection,” Kansas City Star (June 3, 2007): E4, as Man With a Pipe.

Steve Paul, “More than meets the eye,” Kansas City Star 127, no. 266 (June 10, 2007): A16, (repro.), as Man With Pipe.

“Lasting Impressions: A Tribute to Marion and Henry Bloch,” Member Magazine (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (Fall 2007): 11, (repro.).

Steve Paul, “Pretty Pictures: Marion and Henry Bloch’s collection of superb Impressionist masters,” Panache 4, no. 3 (Fall 2007): 20, 22, (repro.), as Man with a Pipe.

Stephanie Buck et al., eds., The Courtauld Cézannes, exh. cat. (London: Courtauld Gallery, 2008), 94.

Carol Vogel, “O! Say, You Can Bid on a Johns,” New York Times 159, no. 54,942 (February 5, 2010): C26.

Nancy Ireson and Barnaby Wright, eds., Cézanne’s Card Players, exh. cat. (London: Courtauld Gallery, 2010), 15, 17, 30n9, 41, 102–04, 135–36, (repro.), as Man with a Pipe.

Possibly Karen Rosenberg, “Workers at Rest: Smoking and Playing Cards,” New York Times 160, no. 55,313, (February 11, 2011): C28, as Man With a Pipe.

Thomas M. Bloch, Many Happy Returns: The Story of Henry Bloch, America’s Tax Man (Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons, 2011), 174, as The Pipe Smoker.

Paul Cézanne: Joueur de cartes; Impressionist and Modern Art Evening Sale (New York: Christie’s, April 30, 2012), 6, 20.

Satish Padiyar, ed., Modernist Games: Cézanne and His Card Players (London: Courtauld Institute of Art, 2013), 148n53.

Diane Stafford, “Bloch gift to go for Nelson upgrade,” Kansas City Star 135, no. 203 (April 8, 2015): A8.

“Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art officially accessions Bloch Impressionist masterpieces,” Artdaily.org (July 25, 2015): http://artdaily.com/news/80246/Nelson-Atkins-Museum-of-Art-officially-accessions-Bloch-Impressionist-masterpieces, as Man with a Pipe.

Julie Paulais, “Le Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art reçoit des tableaux impressionnistes en échange de leurs répliques,” Le Journal des arts (July 30, 2015): https://www.lejournaldesarts.fr/patrimoine/le-nelson-atkins-museum-art-recoit-des-tableaux-impressionnistes-en-echange-de-leurs.

Josh Niland, “The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Acquires a Renowned Collection of Impressionist and Postimpressionist Art,” architecturaldigest.com (July 31, 2015): https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/nelson-atkins-museum-accessions-bloch-art-collection, (repro.), as Man with a Pipe.

Nancy Staab, “Van Gogh is a Go!” 435: Kansas City’s Magazine (September 2015): 76, as Man with a Pipe.

“Nelson-Atkins to unveil renovated Bloch Galleries of European Art in winter 2017,” Artdaily.org (July 20, 2016): http://artdaily.com/news/88852/Nelson-Atkins-to-unveil-renovated-Bloch-Galleries-of-European-Art-in-winter-2017-, as Man with a Pipe.

“Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art celebrates generosity of Henry Bloch with new acquisition,” Artdaily.org (October 18, 2016): https://artdaily.cc/news/90923/Nelson-Atkins-Museum-of-Art-celebrates-generosity-of-Henry-Bloch-with-new-acquisition#.XnKATqhKiUk.

Catherine Futter et al., Bloch Galleries: Highlights from the Collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2016), 106–07, (repro.), as Man with a Pipe.

Kelly Crow, “Museum Rewards Donor with Fake Art to Hang at Home,” Wall Street Journal (January 25, 2017): https://www.wsj.com/articles/museum-rewards-donor-with-fake-art-to-hang-at-home-1485370768, (repro.), as Man with a Pipe.

David Frese, “Bloch savors paintings in redone galleries,” Kansas City Star (February 25, 2017): 1A.

Albert Hecht, “Henry Bloch’s Masterpieces Collection to Go On Display at Nelson-Atkins Museum,” Jewish Business News (February 26, 2017): http://jewishbusinessnews.com/2017/02/26/henry-bloch-masterpieces-collection/.

David Frese, “Inside the Bloch Galleries: An interactive experience,” Kansas City Star 137, no. 169 (March 5, 2017): 1D, 5D, (repro.), as Man With a Pipe.

“Editorial: Thank you, Henry and Marion Bloch,” Kansas City Star (March 7, 2017), http://www.kansascity.com/opinion/editorials/article137040948.html [repr. “Thank you, Henry and Marion Bloch,” Kansas City Star 137, no. 172 (March 8, 2017): 16A].

Hampton Stevens, “(Not Actually) 12 Things To Do During the Big 12 Tournament,” Flatland: KCPT’s Digital Magazine (March 9, 2017): http://www.flatlandkc.org/arts-culture/sports/not-actually-12-big-12-tournament/.

Laura Spencer, “The Nelson-Atkins’ Bloch Galleries Feature Old Masterworks and New Technology,” KCUR (March 10, 2017): http://kcur.org/post/nelson-atkins-bloch-galleries-feature-old-masterworks-and-new-technology#stream/0, as Man with a Pipe.

Victoria Stapley-Brown, “Nelson-Atkins Museum’s new European art galleries come with a ‘love story,’” Art Newspaper (March 10, 2017): http://theartnewspaper.com/news/museums/nelson-atkins-museum-s-new-european-art-galleries-come-with-a-love-story/.

Harry Bellet, “Don du ciel pour le Musée Nelson-Atkins,” Le Monde (March 13, 2017): http://www.lemonde.fr/arts/article/2017/03/13/don-du-ciel-pour-le-musee-nelson-atkins_5093543_1655012.html.

Menachem Wecker, “Jewish Philanthropist Establishes Kansas City as Cultural Mecca,” Forward (March 14, 2017): http://forward.com/culture/365264/jewish-philanthropist-establishes-kansas-city-as-cultural-mecca/ [repr. in Menachem Wecker, “Kansas City Collection Is A Chip Off the Old Bloch,” Forward (March 17, 2017): 20-22].

Juliet Helmke, “The Bloch Collection Takes up Residence in Kansas City’s Nelson Atkins Museum,” Blouin ArtInfo International (March 15, 2017): http://www.blouinartinfo.com/news/story/2005267/the-bloch-collection-takes-up-residence-in-kansas-citys.

Louise Nicholson, “How Kansas City got its magnificent museum,” Apollo: The International Art Magazine (April 7, 2017): https://www.apollo-magazine.com/how-kansas-city-got-its-magnificent-museum/, (repro.).

Lilly Wei, “Julián Zugazagoitia: ‘Museums should generate interest and open a door that leads to further learning,’” Studio International (August 21, 2017): http://studiointernational.com/index.php/julian-zugazagoitia-director-nelson-atkins-museum-of-art-kansas-city-interview, (repro.) as Man with a Pipe.

John Elderfield, Cézanne: Portraits, exh. cat. (London: National Portrait Gallery, 2017), 199, 201, 241, 252, (repro.), as Man with Pipe.

Robert D. Hershey Jr., “Henry Bloch, H&R Block’s cofounder, dies at 96,” Boston Globe (April 23, 2019): https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/obituaries/2019/04/23/henry-bloch-block-cofounder/Vj42N3pMidFGni38EUajyO/story.html.

Robert D. Hershey Jr., “Henry W. Bloch, Tax-Preparation Pioneer (and Pitchman), Is Dead at 96,” New York Times (April 23, 2019): https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/23/obituaries/henry-w-bloch-dead.html.

Claire Selvin, “Henry Wollman Bloch, Collector and Prominent Benefactor of Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Is Dead at 96,” ArtNews (April 23, 2019): http://www.artnews.com/2019/04/23/henry-bloch-dead-96/.

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “Henry Bloch, co-founder of H&R Block, dies at 96,” Kansas City Star 139, no. 219 (April 24, 2019): 1A.

“Henry Wollman Bloch (1922–2019),” Artforum (April 24, 2019): https://www.artforum.com/news/henry-wollman-bloch-1922-2019-79547.

Frank Morris, “Henry Bloch, Co-Founder Of H&R Block, Dies At 96,” NPR (April 24, 2019): https://www.npr.org/2019/04/24/716641448/henry-bloch-co-founder-of-h-r-block-dies-at-96.

Ignacio Villarreal, “Nelson-Atkins mourns loss of Henry Bloch,” ArtDaily.org (April 24, 2019): http://artdaily.com/news/113035/Nelson-Atkins-mourns-loss-of-Henry-Bloch#.XMB76qR7laQ, as Man with a Pipe.

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “H&R Block co-founder, philanthropist Bloch dies,” Cass County Democrat Missourian 140, no. 29 (April 26, 2019): 1A.

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “KC businessman and philanthropist Henry Bloch dies,” Lee’s Summit Journal 132, no. 79 (April 26, 2019): 1A.

Luke Nozicka, “Family and friends remember Henry Bloch of H&R Block,” Kansas City Star 139, no. 225 (April 30, 2019): 4A [repr. Luke Nozicka, “Family and friends remember Henry Bloch of H&R Block,” Kansas City Star 139, no. 228 (May 3, 2019): 3A].

Denis Coutagne and François Chédeville, eds., Cézanne, Jas de Bouffan: art et histoire (Lyon: Fage, 2019), 83, 221, 231, (repro.), as L’Homme à la pipe.

Walter Feilchenfeldt, Jayne Warman, and David Nash, “L’Homme à la pipe, 1891–92 (FWN 678),” The Paintings, Watercolors and Drawings of Paul Cezanne: An Online Catalogue Raisonné, https://www.cezannecatalogue.com/ catalogue/entry.php?id=683 (last updated on August 21, 2020, accessed on October 26, 2020), (repro.), as L’Homme à la pipe.

Eric Adler, “Sold for $3.25 million, Bloch’s home in Mission Hills may be torn down,” Kansas City Star 141, no. 90 (December 16, 2020): 2A.

Nancy Ireson, André Dombrowski, and Sylvie Patry, Cézanne in the Barnes Foundation (Philadelphia: Barnes Foundation, 2021).