![]()

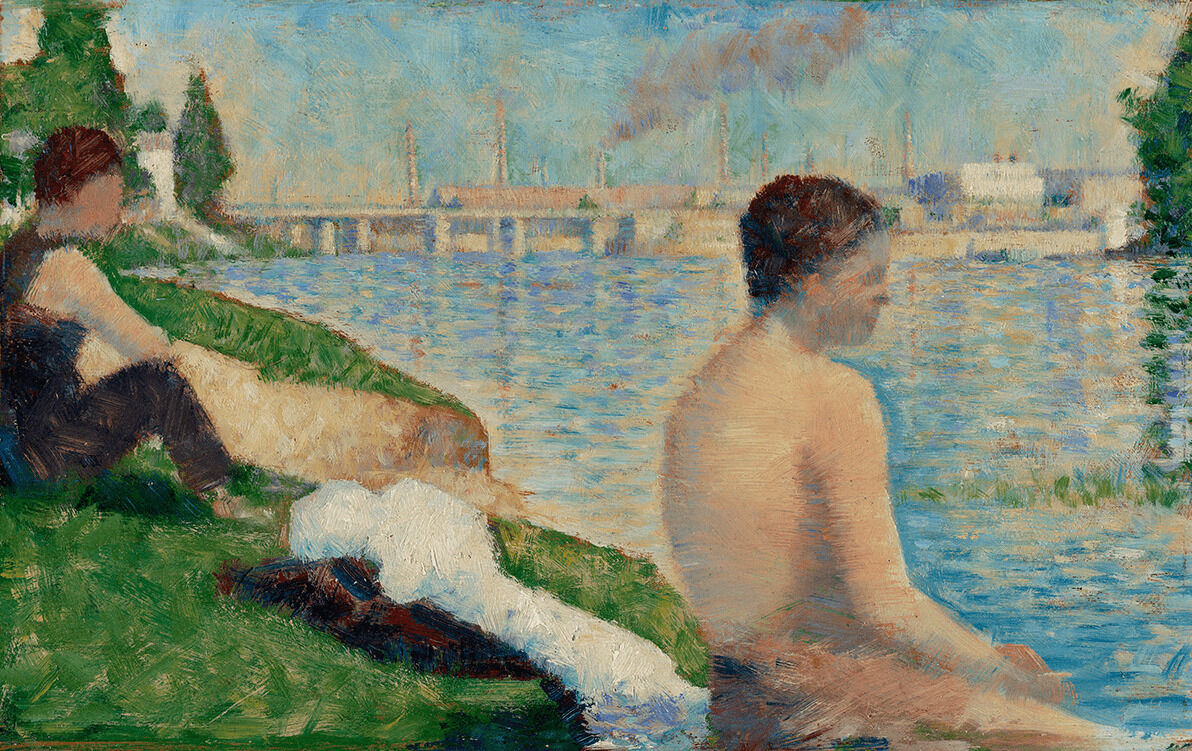

Georges Seurat, Study for “Bathers at Asnières,” 1883

| Artist | Georges Seurat, French, 1859–91 |

| Title | Study for “Bathers at Asnières” |

| Object Date | 1883 |

| Alternate and Variant Titles | Study for “A Bathing Place, Asnières”; Study for “La Baignade”; Une Baignade, Asnières |

| Medium | Oil on panel |

| Dimensions (Unframed) | 6 7/8 x 10 3/8 in. (17.5 x 26.4 cm) |

| Credit Line | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 33-15/3 |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Ellen W. Lee, “Georges Seurat, Study for “Bathers at Asnières,” 1883,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.724.5407.

MLA:

Lee, Ellen W. “Georges Seurat, Study for “Bathers at Asnières,” 1883,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.724.5407.

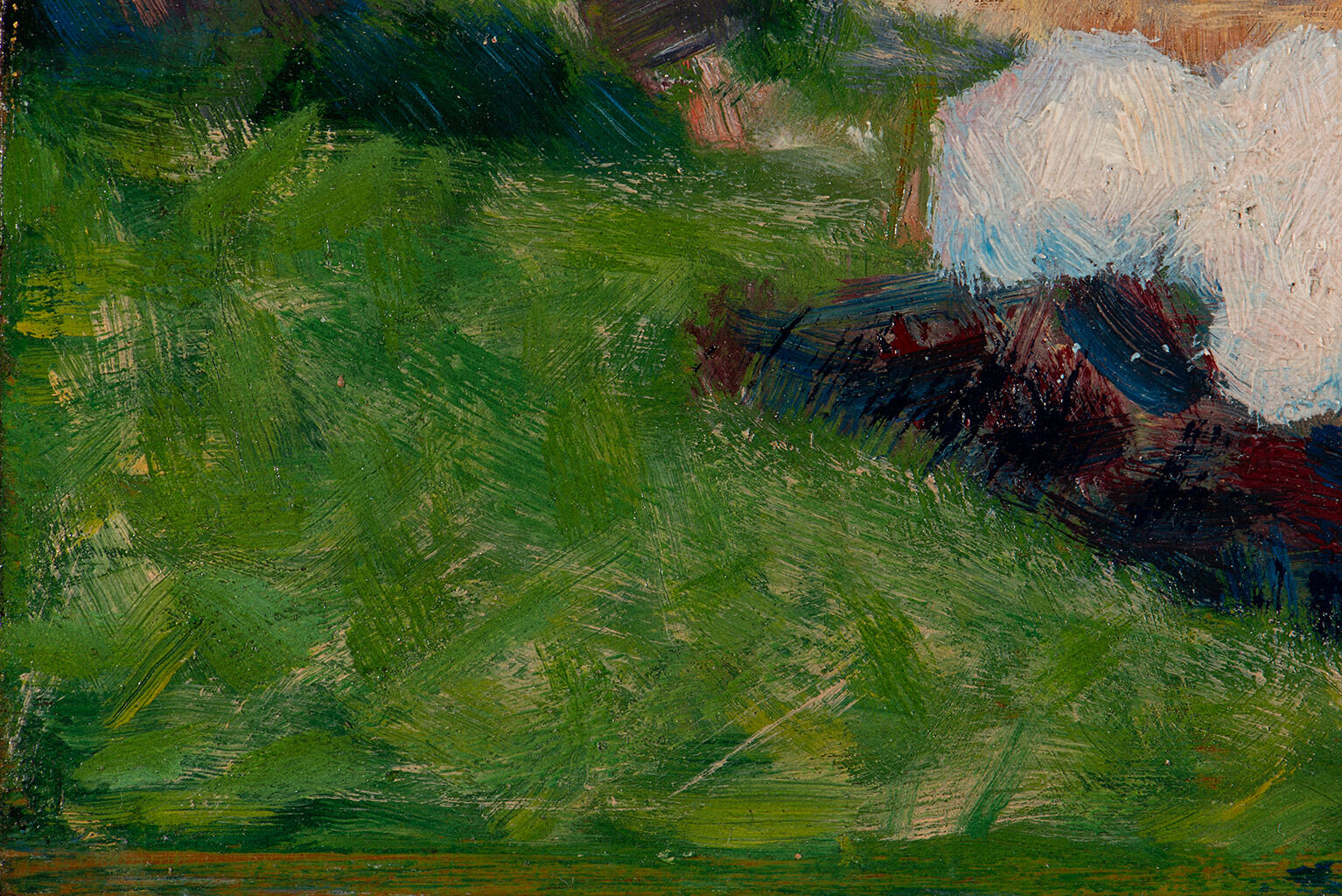

This small waterside scene carries an impact totally at odds with its modest size. Within its six-by-ten-inch surface is evidence of the issues and methods pursued by the young Georges Seurat at the debut of his career. The Nelson-Atkins sketch is one of thirteen oil panels and ten Conté crayon drawings made in preparation for the artist’s first major work, Bathers at Asnières (Fig. 1), a monumental canvas that he hoped to exhibit at the 1884 SalonSalon, the: Exhibitions organized by the French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture (Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture) and its successor the Academy of Fine Arts (Académie des Beaux Arts), which took place in Paris from 1667 onward. in Paris. It reflects the artist’s background and points to the remarkable and enigmatic path that lay ahead.

While some of the preparatory works were executed in Seurat’s Paris studio,1The ten preparatory drawings for this composition were likely made from models in the studio and certainly interconnect with the oil sketches but are not addressed in this essay. others were created more spontaneously sur le motifsur le motif: French for “in front of the object.” A term used for sketching or painting from life., or directly in front of the subject. That motif, Asnières, was a suburb on the northwestern outskirts of Paris, bordering the Seine River. In 1883, Asnières was a growing industrial area populated by an intriguing mix of the petits bourgeois (often shopkeepers and clerks), artisans, and members of the working class. Seurat’s choice of locale links him to a new generation of painters drawn to the signs of industry and technology that marked their modern era. Similarly, Seurat’s characters were not saints and superheroes, or the bourgeoisie depicted by most Impressionists, but working-class men and boys relaxing on the riverbank, at a less-than-fashionable spot on the Seine. A view recorded by an unknown photographer shows a similar scene of men and boys splashing along the shore at Ivry, the port at Anglais (Fig. 2). Other progressive painters who would join Seurat in the remarkable artistic energy of the later 1880s—Post-Impressionists such as Paul Signac (1863–1935), Émile Bernard (1868–1941), and Vincent van Gogh (Dutch, 1853–90)—also painted in this diverse, bustling suburb.2For this and so many of the wide-ranging observations about this body of work, I am indebted to the publication produced by the National Gallery, London: John Leighton and Richard Thomson, Seurat and the Bathers, exh. cat. (London: National Gallery Publications, 1997).

Apparent even in the sketch is the balance that prevails in the clearly delineated composition and the solidity of its figures. This sense of order and balance suggests the fundamental equilibrium of the classical tradition at the heart of Seurat’s training. The intense young artist seems to have had an instinct for steadiness and gravitas—even when depicting a casual vignette of leisure.

The figures, setting, and brushwork of the Nelson-Atkins picture indicate that it is one of the later preparatory sketches, and most of its facets were retained in the final work.4Leighton and Thomson, Seurat and the Bathers, 61. The seated boy who dominates the finished painting is more defined here than elsewhere, and the still-life of discarded clothing has taken shape. Seurat also added detail to the frieze of smokestacks, factories, and railway bridge supports that close the vista.

The sketch teems with the vigorous brushwork that Seurat explored in the early 1880s, not only in the Asnières panels but also in small agrarian scenes inspired by the Barbizon SchoolBarbizon School: A group of French artists, who united around 1830 to form the Barbizon School, which was named after a small village thirty miles northwest of Paris, where they lived and painted. Rebelling against the French Academy’s refined, idealized landscapes, these artists infused the immediacy of the sketches they created outdoors into their finished studio paintings.. He applied a variety of broken, hashed strokes at different angles but had not yet devised the dotted, pointillist facturefacture: The artist’s characteristic handling of paint. of his later works. Treatment of the larger bather demonstrates the range of Seurat’s strokes: fine blue striations shade the face, while broad strokes cross his clothing, chasing the reflections of the brightly lit scene.

Seurat was fully aware of the bright colors used by his Impressionist elders, but more influential for the young artist were the writings on color relationships by aesthetician Charles Blanc (1813–82), which Seurat read as a student, and chemist Michel Eugène Chevreul (1786–1889).5Michel Chevreul, De la Loi du Contraste Simultané des Couleurs et de l’Assortiment des Objets Colorés (Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, Librairie Gauthier-Villars et Fils, 1839); and Charles Blanc, Grammaire des Arts du Dessin, Architecture, Sculpture, Peinture (Paris: Librairie Renouard, 1867). Seurat also admired the example of Romantic painter Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863) and took notes on how he often separated large areas of complementary color, such as red and green, to make his compositions more vibrant. Demonstrating his growing interest in color perception, Seurat studied how the separation of colors affects their interactions, creating more brilliant effects.6For what remains the most lucid explanation of the precepts of color behavior and divided brushwork, see Robert L. Herbert, Neo-Impressionism, exh. cat. (New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum of Art, 1968).

In the Nelson-Atkins study, short, juxtaposed ribbons of blue and rose create the glistening water of the river. The mass of white clothing on the riverbank mirrors Seurat’s attention to color behavior: blue strokes indicate the presence of shadows, while flecks of rose are the reflections cast by the attire of the adjacent bather. Seurat defines the form of the boy’s right arm by clustering blue hues of the water along the warm edge of his skin (Fig. 3), demonstrating his understanding of the law of irradiation, which holds that when two adjacent areas of unequal tones are juxtaposed, the differences will appear the most pronounced at the edge where they meet. This is one of several principles regarding contrasting color and tone that Seurat went on to develop fully in his mature work.

A few months after making the Nelson-Atkins sketch, Seurat submitted the finished work, Bathers at Asnières, to the jury of the 1884 Paris Salon. Inextricably linked to the government-sponsored École des Beaux-Arts, the Salon was still largely loyal to more traditional painting. While a few commercial galleries and alternative exhibition opportunities had begun to appear in Paris, the Salon remained the preeminent exhibition venue, critical to future sales and commissions, and strategic to unknown artists seeking a reputation.

The jury for the Salon of 1884 rejected Seurat’s submission. There are any number of plausible reasons why this beautiful, inscrutable, light-filled canvas was refused, but the large number of spurned works that year led to the creation of an alternative exhibition, organized independently by the artists with the support of Paris’s Republican government. Seurat sent his picture to this juryless venture, called the Groupe des Artistes Indépendants (later the Société des Artistes Indépendants)Société des Artistes Indépendants: A group founded in 1884 in Paris by Odilon Redon, Albert Dubois-Pillet, Georges Seurat, and Paul Signac that created the Salon des Indépendants as an alternative to exhibiting at the Salon organized and juried by the French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture (Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture). The Salon des Indépendants has no selection committee; instead, artists can exhibit on payment of a fee. The exhibitions became the main venue for many artists, particularly the Post-Impressionists in the late nineteenth century. The Salon des Indépendants is still in existence today. See also Salon, the., where he met several of the painters who became his colleagues in the late nineteenth century’s emergence of the avant-garde.7Artists participating in this spontaneous exhibition soon reorganized to create the highly important Société des Artistes Indépendants, which Seurat supported throughout the rest of his life.

After 1884, the Nelson-Atkins panel was not relegated to Seurat’s studio. In 1886, it was one of several works exhibited in New York by Impressionist dealer Paul Durand-Ruel (1831–1922).9Durand-Ruel, the Parisian dealer who was the first to support the Impressionists, organized an exhibition for the New York market, including the Nelson-Atkins sketch, entitled Works in Oil and Pastel by the Impressionists of Paris, The American Art Galleries, New York, April 10–28, 1886; National Academy of Design, New York, opened May 25, 1886, no. 133, p. 25. This exhibition was not the first time that Seurat had allowed his studies to be displayed. Landscape, Island of La Grande Jatte (1884; private collection), an oil version of the site without any figures, though admittedly far more finished than the Asnières sketch, was shown at the Société des Artistes Indépendants in December 1884, no. 241 (no catalogue has been located). The exhibition, titled Works in Oil and Pastel by the Impressionists of Paris, included the piece as one of twelve small sketches assembled in one frame.10It is possible that the narrow wood strips (fillets) currently on each side of the Nelson-Atkins sketch come from its mounting in the twelve-piece ensemble. That Seurat regarded the study as worthy of exhibition is a ringing endorsement of its significance. The following spring he showed the panel at the annual Société des Artistes Indépendants exhibition in Paris.11Société des Artistes Indépendants: 3e exposition, Pavillon de la Ville de Paris, Paris, March 26–May 3, 1887, no. 447, p. 23. In 1892, it was included in another important venue for Seurat’s work, the annual exhibition in Brussels of the progressive artists’ group, Les XX (The Twenty)—this time as part of a posthumous presentation in his memory.12Neuvième exposition annuelle des XX, Musée d’Art Moderne, Brussels, February 6–March 6, 1892, no. 1, unpaginated. The dramatic change in the nature of that brief exhibition history underscores the shock of the young artist’s sudden death in March 1891, at the age of thirty-one.13After assisting with the installation of the annual exhibition of the Société des Artistes Indépendants, Seurat fell ill on March 26, 1891. The malady, probably a form of infectious diphtheria, worsened quickly, and the artist died at his mother’s home on March 29, 1891.

Seurat’s small panel changed hands numerous times between the Les XX exhibition in Brussels and its acquisition by the Nelson-Atkins. It was included in a 1918 exhibition that was among the first to showcase French modernism in Norway,14Den franske utstilling I Kunstnerforbundet, Kunstnerforbundet, Kristiania (Oslo), January 19–February 18, 1918, no. 87. where it was purchased by Norwegian shipping magnate Jørgen Breder Stang (1874–1950), who also owned Paul Gauguin’s (1848–1903) Where Do We Come From? Who Are We? Where Are We Going? (1897–98; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston). When Stang started selling his collection in the late 1920s due to an economic downturn, there was no shortage of European dealers eager to acquire his paintings. The study was ultimately purchased by dealer César Mange de Hauke (1900–65) and Alex Reid & Lefèvre. In a letter to a colleague, De Hauke wrote glowingly of this sketch and another by Seurat, saying: “There are no finer panels than these; they come from an excellent collection.”15De Hauke to James St. Laurence O’Toole, January 23, 1929, Jacques Seligmann & Co. Records, 1904–1978, bulk 1913–1974, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC; series 9: De Hauke & Co., Inc., Records, 1925–1949, undated; Series 9.1.5: Inter-Office Correspondence, 1926–1930; box 403, folder 1, Paris–New York, New York–Paris, 1929 January–September.

The Nelson-Atkins study, a shrewd acquisition by the newly opened museum in 1933, is a telling work in its own right and a vital contributor to Seurat’s first major undertaking. The Asnières ensemble introduces us to Seurat’s dedication to artistic virtuosity and close observation, classical precedent and modern public life. At the upper right edge of the Nelson-Atkins panel is a passage of green strokes casting their reflection in the river. It is in fact the wooded tip of La Grande Jatte, a popular island destination in the Seine and a harbinger of the young artist’s next challenge.16Shortly after the completion of the Asnières canvas, Seurat embarked on the ambitious process of developing his next major work, A Sunday on La Grande Jatte (1884–86; Art Institute of Chicago).

Notes

-

The ten preparatory drawings for this composition were likely made from models in the studio and certainly interconnect with the oil sketches but are not addressed in this essay.

-

For this and so many of the wide-ranging observations about this body of work, I am indebted to the publication produced by the National Gallery, London: John Leighton and Richard Thomson, Seurat and the Bathers, exh. cat. (London: National Gallery Publications, 1997).

-

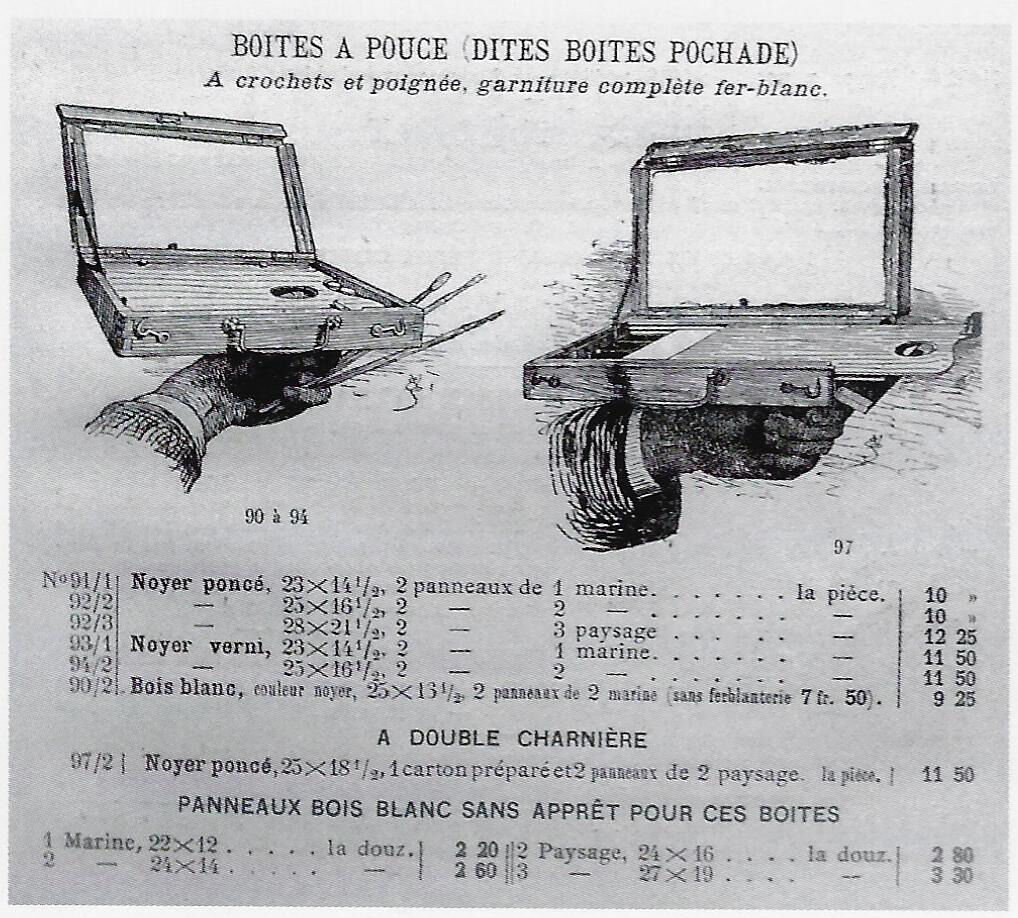

The long-held belief that Seurat made his sketches on discarded cigar box lids has been thoroughly discounted. In Leighton and Thomson, Seurat and the Bathers, 29–30, the authors indicate that Seurat’s mahogany or walnut panels are heavier than the cedar used for cigar boxes, and that it is unlikely the artist would have toyed with removing paper labels when he consistently purchased high- quality materials. Small panels were readily available through artists’ suppliers. See also the accompanying technical entry by Diana M. Jaskierny.

-

Leighton and Thomson, Seurat and the Bathers, 61.

-

Michel Chevreul, De la Loi du Contraste Simultané des Couleurs et de l’Assortiment des Objets Colorés (Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, Librairie Gauthier-Villars et Fils, 1839); and Charles Blanc, Grammaire des Arts du Dessin, Architecture, Sculpture, Peinture (Paris: Librairie Renouard, 1867).

-

For what remains the most lucid explanation of the precepts of color behavior and divided brushwork, see Robert L. Herbert, Neo-Impressionism, exh. cat. (New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum of Art, 1968).

-

Artists participating in this spontaneous exhibition soon reorganized to create the highly important Société des Artistes Indépendants, which Seurat supported throughout the rest of his life.

-

For a thorough exploration of the critical responses to Bathers at Asnières, see “1884: Rejection and Response,” in Leighton and Thompson, Seurat and the Bathers, 122–25.

-

Durand-Ruel, the Parisian dealer who was the first to support the Impressionists, organized an exhibition for the New York market, including the Nelson-Atkins sketch, entitled Works in Oil and Pastel by the Impressionists of Paris, The American Art Galleries, New York, April 10–28, 1886; National Academy of Design, New York, opened May 25, 1886, no. 133, p. 25. This exhibition was not the first time that Seurat had allowed his studies to be displayed. Landscape, Island of La Grande Jatte (1884; private collection), an oil version of the site without any figures, though admittedly far more finished than the Asnières sketch, was shown at the Société des Artistes Indépendants in December 1884, no. 241 (no catalogue has been located).

-

It is possible that the narrow wood strips (fillets) currently on each side of the Nelson-Atkins sketch come from its mounting in the twelve-piece ensemble.

-

Société des Artistes Indépendants: 3e exposition, Pavillon de la Ville de Paris, Paris, March 26–May 3, 1887, no. 447, p. 23.

-

Neuvième exposition annuelle des XX, Musée d’Art Moderne, Brussels, February 6–March 6, 1892, no. 1, unpaginated.

-

After assisting with the installation of the annual exhibition of the Société des Artistes Indépendants, Seurat fell ill on March 26, 1891. The malady, probably a form of infectious diphtheria, worsened quickly, and the artist died at his mother’s home on March 29, 1891.

-

Den franske utstilling I Kunstnerforbundet, Kunstnerforbundet, Kristiania (Oslo), January 19–February 18, 1918, no. 87.

-

De Hauke to James St. Laurence O’Toole, January 23, 1929, Jacques Seligmann & Co. Records, 1904–1978, bulk 1913–1974, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC; series 9: De Hauke & Co., Inc., Records, 1925–1949, undated; series 9.1.5: Inter-Office Correspondence, 1926–1930; box 403, folder 1, Paris–New York, New York–Paris, 1929 January–September.

-

Shortly after the completion of the Asnières canvas, Seurat embarked on the ambitious process of developing his next major work, A Sunday on La Grande Jatte (1884–86; Art Institute of Chicago).

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Diana M. Jaskierny, “Georges Seurat, Study for “Bathers at Asnières,” 1883,” technical entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.724.2088.

MLA:

Jaskierny, Diana M. “Georges Seurat, Study for “Bathers at Asnières,” 1883,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.724.2088.

Executed on a small wooden panel, Study for “Bathers at Asnières” was quickly painted with varied and animated brushwork. The measurements of the single panel, 15.7 x 24.9 centimeters, are consistent with those of other Seurat panels, including the other numerous studies for Bathers at Asnières.1John Leighton and Richard Thomson, with David Bomford, Jo Kirby, and Ashok Roy, Seurat and The Bathers, exh. cat. (London: National Gallery Publications, 1997), 52–63. Although his panel sizes varied slightly,2Variations in size were usually within a few millimeters. Study for “Bathers at Asnières” is close in size to the standard-size panel format no. 2 paysage. Jo Kirby, Kate Stoner, Ashok Roy, Aviva Burnstock, Rachel Grout, and Raymond White, “Seurat’s Painting Practice: Theory, Development and Technology,” National Gallery Technical Bulletin 24 (2003): 18. Seurat frequently used this common size for painting studies throughout his career, indicating that he may have purchased a series of boards from an artist supplierartist supplier(s): Also called colormen and color merchants. Artist suppliers prepared materials for artists. This tradition dates back to the Medieval period, but the industrialization of the nineteenth century increased their commerce. It was during this time that ready-made paints in tubes, commercially prepared canvases, and standard-format supports were available to artists for sale through these suppliers. It is sometimes possible to identify the supplier from stamps or labels found on the reverse of the artwork. See also canvas stamp, supplier mark, and *color merchant..3In a survey of Seurat’s techniques, the National Gallery of London and the Courtauld Institute of Art published an analysis of fifteen of the artist’s study paintings, all of which have approximately the same dimensions as the Nelson-Atkins painting. Kirby et al., “Seurat’s Painting Practice: Theory, Development and Technology,” 5.,4No supplier stamps are visible on the reverse of Study for “Bathers at Asnières,” so it cannot be established through whom they were purchased.

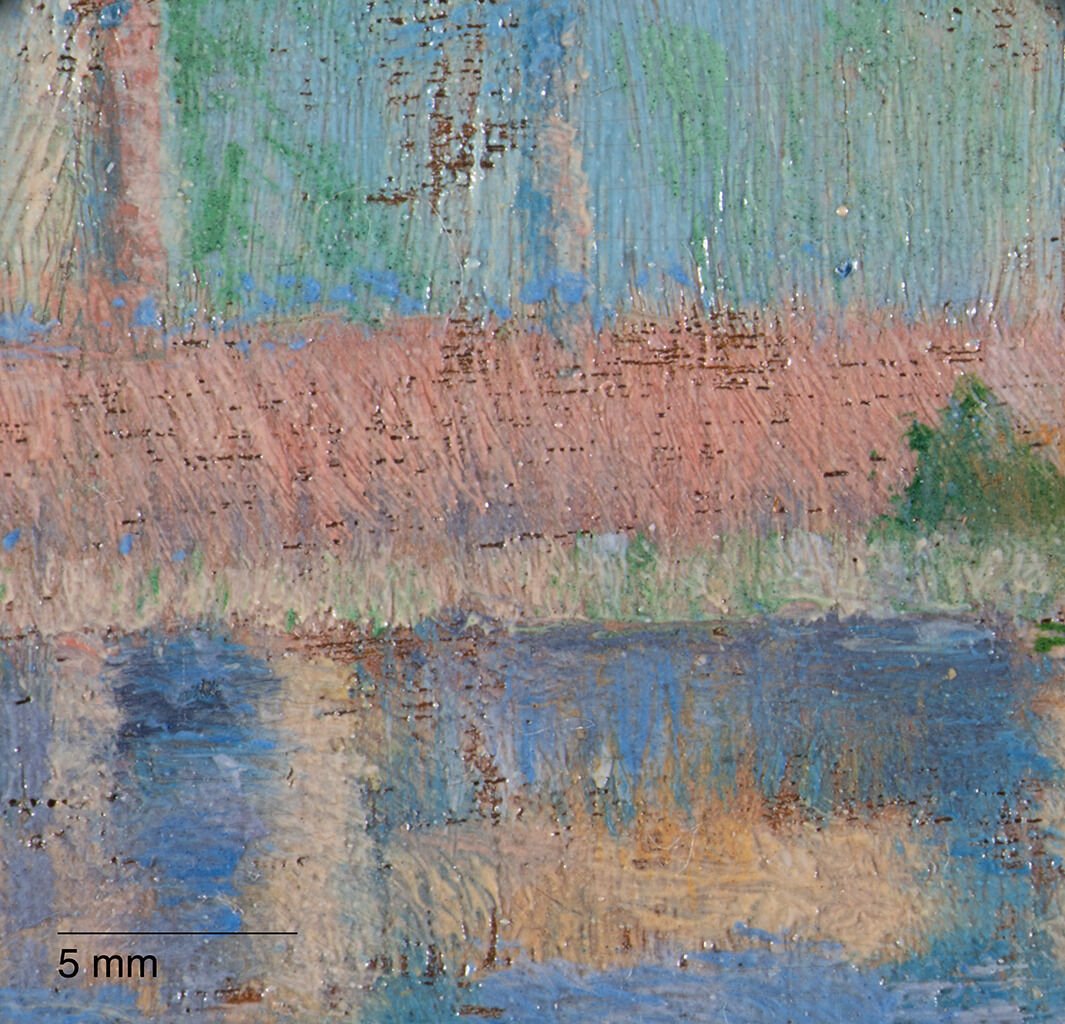

Fig. 6. Photomicrograph with raking light of an indention in the paint on the right edge of Study for “Bathers at Asnières” (1883), possibly from use of a boîte à pouce, or thumbnail paint box

Fig. 6. Photomicrograph with raking light of an indention in the paint on the right edge of Study for “Bathers at Asnières” (1883), possibly from use of a boîte à pouce, or thumbnail paint box

Fig. 7. Photomicrograph of Study for “Bathers at Asnières” (1883), illustrating the warm brown exposed panel wood

Fig. 7. Photomicrograph of Study for “Bathers at Asnières” (1883), illustrating the warm brown exposed panel wood

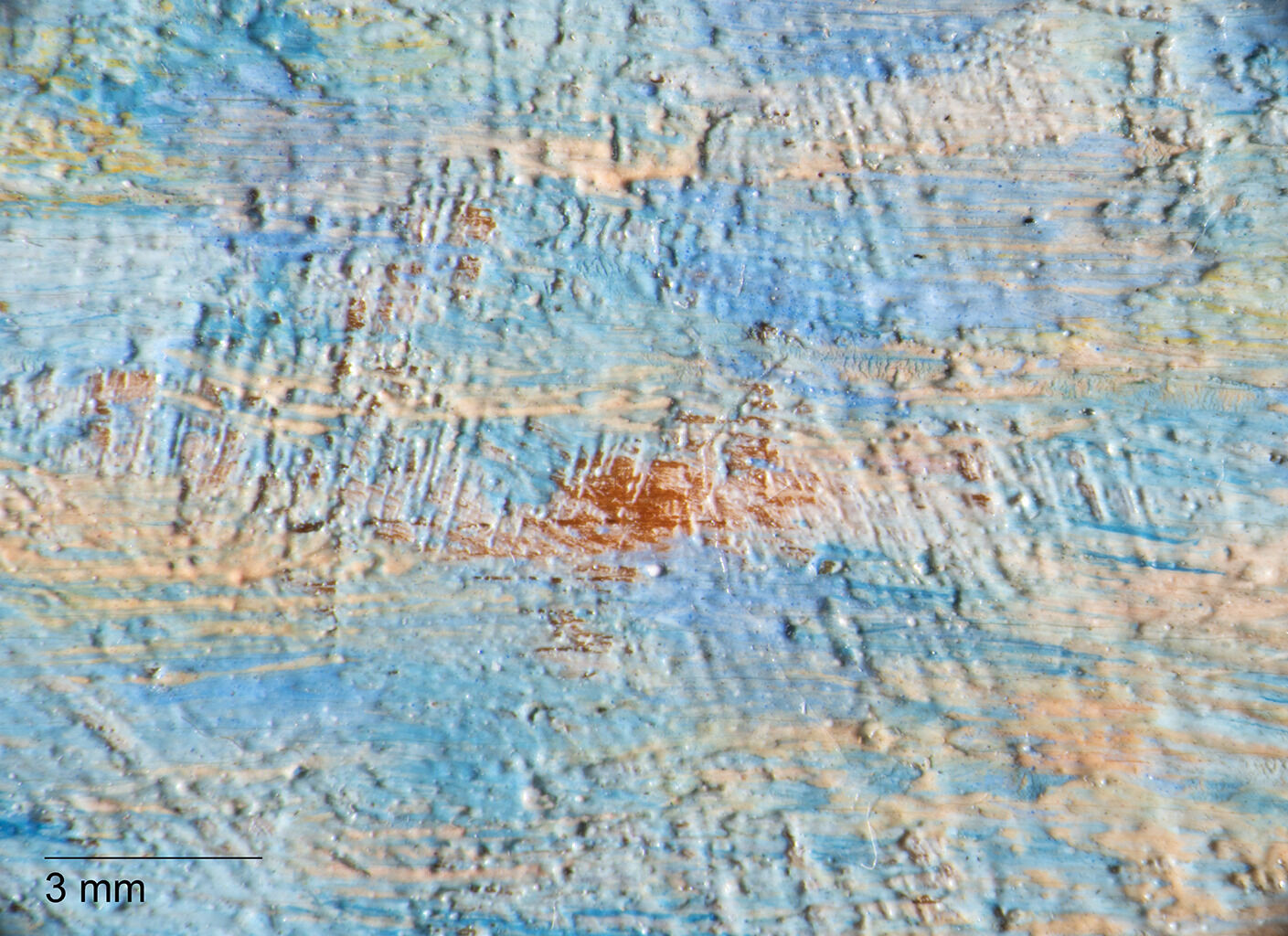

Fig. 9. Photomicrograph in raking light of underlying paint textures within the water of Study for “Bathers at Asnières” (1883)

Fig. 9. Photomicrograph in raking light of underlying paint textures within the water of Study for “Bathers at Asnières” (1883)

Fig. 10. Detail of a pale pink lower paint layer on the right side of the figure and dark pink lower layer on the left side, Study for “Bathers at Asnières” (1883)

Fig. 10. Detail of a pale pink lower paint layer on the right side of the figure and dark pink lower layer on the left side, Study for “Bathers at Asnières” (1883)

Fig. 11. Detail of balayé brushwork in the foreground of Study for “Bathers at Asnières” (1883)

Fig. 11. Detail of balayé brushwork in the foreground of Study for “Bathers at Asnières” (1883)

Fig. 12. Photomicrograph of dashed brushwork of the water in Study for “Bathers at Asnières” (1883)

Fig. 12. Photomicrograph of dashed brushwork of the water in Study for “Bathers at Asnières” (1883)

Fig. 13. Detail of the right-side figure, illustrating the irradiation painting technique on both left and right, Study for “Bathers at Asnières” (1883)

Fig. 13. Detail of the right-side figure, illustrating the irradiation painting technique on both left and right, Study for “Bathers at Asnières” (1883)

Fig. 14. Detail of Seurat’s use of the irradiation painting technique where the water’s edge meets the riverbank, Study for “Bathers at Asnières” (1883)

Fig. 14. Detail of Seurat’s use of the irradiation painting technique where the water’s edge meets the riverbank, Study for “Bathers at Asnières” (1883)

Notes

-

John Leighton and Richard Thomson, with David Bomford, Jo Kirby, and Ashok Roy, Seurat and The Bathers, exh. cat. (London: National Gallery Publications, 1997), 52–63.

-

Variations in size were usually within a few millimeters. Study for “Bathers at Asnières” is close in size to the standard-sizestandard-format supports: Commercially prepared supports available through art suppliers, which gained popularity in the nineteenth century during the industrialization of art materials. Available in three formats figure (portrait), paysage (landscape), and marine (marine), these were numbered 1 through 120 to indicate their size. For each numbered size, marine and paysage had two options available: a larger format (haute) and smaller (basse) format. panel format no. 2 paysage. Jo Kirby, Kate Stoner, Ashok Roy, Aviva Burnstock, Rachel Grout, and Raymond White, “Seurat’s Painting Practice: Theory, Development and Technology,” National Gallery Technical Bulletin 24 (2003): 18.

-

In a survey of Seurat’s techniques, the National Gallery of London and the Courtauld Institute of Art published an analysis of fifteen of the artist’s study paintings, all of which have approximately the same dimensions as the Nelson-Atkins painting. Kirby et al., “Seurat’s Painting Practice: Theory, Development and Technology,” 5.

-

No supplier stamps are visible on the reverse of Study for “Bathers at Asnières,” so it cannot be established through whom they were purchased.

-

Anthea Callen, The Work of Art: Plein-Air Painting and Artistic Identity in Nineteenth-Century France (London: Reaktion Books, 2015), 252–54.

-

Similar marks of displaced paint were identified on Seurat’s Figure in a Landscape at Barbizon (ca. 1882; Wallraf-Richartz Museum, Cologne). Katja Lewerentz, “Georges Seurat—Figure in a Landscape at Barbizon, Brief Report on Technology and Condition,” in Research Project: Painting Techniques of Impressionism and Postimpressionism, Wallraf-Richartz-Museum and Fondation Corboud, Cologne, 2008, https://forschungsprojekt-impressionismus.de/bilder/pdf/45_e.pdf.

-

Kirby et al., “Seurat’s Painting Practice: Theory, Development and Technology,” 5.

-

Priming in which the texture of the panels’ grain is filled is referred to as rebouchés. Kirby et al., “Seurat’s Painting Practice: Theory, Development and Technology,” 18.

-

While other large-scale paintings and accompanying studies by Seurat were found to have a grid underdrawing to assist in transferring compositions, no such system was found on Bathers at Asnières (1884; National Gallery, London) or in the Nelson-Atkins study. Kirby et al., “Seurat’s Painting Practice: Theory, Development and Technology,” 19.

-

Similar blocking-in has been observed in other Seurat paintings, including the final version of Bathers at Asnières (1884; National Gallery, London). Kirby et al., “Seurat’s Painting Practice: Theory, Development and Technology,” 20–21.

-

It is difficult to determine if there is an underlayer in the sky, but a cream-colored layer appears to be present, similar to what is found beneath the water.

-

Both these regions appear lean, and it is unclear if they extend beneath the entirety of each figure.

-

The term balayé is a derivative of the French word balayeur, or “road sweeper.” Anthea Callen, The Work of Art: Plein-Air Painting and Artistic Identity in Nineteenth-Century France, 250.

-

Hermann von Helmholtz, “L’optique et la peinture,” in Principes scientifiques des beaux-arts, ed. Ernst von Brücke (Paris: Librarie Germer Baillière et Cie., 1878), 207–9. See also Kirby et al., “Seurat’s Painting Practice: Theory, Development and Technology,” 13–14.

-

Forrest R. Bailey, treatment report, September 3, 1988, NAMA conservation file, 33-15/3.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Georges Seurat, Study for “Bathers at Asnières,” 1883,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.724.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Georges Seurat, Study for “Bathers at Asnières,” 1883,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.724.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Georges Seurat, Study for “Bathers at Asnières,” 1883,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.724.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Georges Seurat, Study for “Bathers at Asnières,” 1883,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.724.4033.

With the artist, Paris, 1883–March 29, 1891 [1];

Inherited by the artist’s common-law wife, Madeleine Knoblock (ca. 1868–1903), Paris, 1891–March 6, 1892 [2];

Purchased from Knoblock by Jean-Baptiste Degreef (1852–94), Auderghem, Belgium, 1892–no later than December 19, 1894 [3];

Possibly with Bernheim-Jeune, Paris [4];

With Walther Halvorsen, Paris, by January 19, 1918 [5];

Purchased from Halvorsen by Jørgen Breder Stang (1874–1950), Kristiania (Oslo), Norway, 1918–December 18, 1928 [6];

Purchased from Stang through Dr. Alfred Gold, Berlin, by de Hauke and Co., Inc., Paris and New York, stock no. 3353, on joint account with Alex Reid and Lefèvre, Ltd., Glasgow and London, stock nos. 283 and 348/28, 1928–March 6, 1929, as Study for La Baignade [7];

Purchased from de Hauke and Co., Inc., and Alex Reid and Lefèvre, Ltd., by M. Knoedler and Co., New York, stock no. A565, as Study for La Baignade, March 6–20, 1929 [8];

Purchased from M. Knoedler and Co. by Stephen Carlton Clark, Sr. (1882–1960), New York, 1929–August 31, 1931 [9];

Bought back from Clark by M. Knoedler and Co., New York, stock no. A1379, as Study for La Baignade, 1931–January 28, 1933 [10];

Purchased from M. Knoedler and Co. by The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1933.

Notes

[1] On May 3, 1891, one month after Seurat’s sudden death, Madeleine Knoblock, Émile Seurat, Paul Signac, Maximilien Luce, and Félix Fénéon gathered to inventory the contents of the artist’s atelier. They annotated the verso of each artwork with a number and the initials P. S., L., or F. F. However, Study for “Bathers at Asnières” was one of twelve panels displayed in a single frame, so it did not receive initials or an individual number. See C[ésar] M[ange] de Hauke, Seurat et son œuvre (Paris: Gründ, 1961), 1:XXX.

[2] Per Madeleine Knoblock’s handwritten list from May 3, 1891, she received the “panneaux encadrés” (framed panels) as part of her inheritance. See C[ésar] M[ange] de Hauke, Seurat et son œuvre (Paris: Gründ, 1961), 1:XXVIII.

[3] Knoblock loaned the twelve framed panels to the Neuvième exposition annuelle des XX, Musée d’Art Moderne, Brussels, February 6–March 6, 1892; see Robert L. Herbert, Georges Seurat, 1859–1891, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1991), 127–28. Degreef purchased all twelve sketches during the course of the exhibition; see “Clôture du Salon des XX,” L’Art moderne 12, no. 11 (March 13, 1892): 83. He died two years later, on December 19, 1894.

[4] Bernheim-Jeune appears in the provenance of Study for “Bathers at Asnières” in the Dorra-Rewald catalogue raisonné but not the de Hauke catalogue raisonné. See Henri Dorra and John Rewald, Seurat: L’Œuvre peint; Biographie et catalogue critique (Paris: Les Beaux-Arts, 1959), no. 96, p. 95; and C[ésar] M[ange] de Hauke, Seurat et son œuvre (Paris: Gründ, 1961), no. 91, p. 52. A consortium of Paris dealers, including Bernheim-Jeune, lent works to Den franske utstilling i Kunstnerforbundet, Kristiania (Oslo), January 19–February 18, 1918, in which Study for “Bathers at Asnières” was included (see endnote 5). It is possible that Bernheim-Jeune lent the Nelson-Atkins painting to this show.

[5] Walther Halvorsen (1887–1972) was a marchand en chambre (dealer without a gallery) in Paris who helped introduce French Impressionism and Post-Impressionism to Scandinavia. Study for “Bathers at Asnières” was in his possession by January 19, 1918, when an exhibition he co-organized with Norwegian museum director Jens Thiis opened in Kristiania (Oslo); see Den franske utstilling i Kunstnerforbundet, exh. cat. (Kristiania [Oslo]: Centraltrykkeriet, 1918), p. 29, cat. 87. It is unclear whether Halvorsen owned the Nelson-Atkins painting outright or was acting as a broker for a Parisian dealer (see endnote 4). Halvorsen’s business records do not survive; according to his first wife, Greta Prozor (1886–1978), he destroyed them himself; see Christel H. Force, ed., Pioneers of the Global Art Market: Paris-Based Dealer Networks, 1850–1950 (London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2020), 152n42.

[6] Stang purchased Study for “Bathers at Asnières” during the Kunstnerforbundet exhibition; see Nils Messel, Den Stangske Samling: Jørgen Breder Stangs franske bilder (Oslo: Messel Forlag, 2020), 24. The painting remained in his collection until December 18, 1928, when he consigned it and one other panel painting by Seurat to the dealer Dr. Alfred Gold (1874–1958) in Berlin; see letter from Gold to César M. de Hauke, December 18, 1928, Jacques Seligmann and Co. Records, 1904–1978, bulk 1913–1974, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, Series 9.1.3, Box 394, Folder 18 (hereafter cited as Jacques Seligmann and Co. Records).

[7] The Nelson-Atkins painting was previously misidentified as de Hauke and Co. stock no. 3352; see Robert L. Herbert, Georges Seurat, 1859–1891, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1991), 159. However, stock no. 3352 is actually Seurat’s The Seine with Clothing on the Bank, 1883–1884, oil on panel, 6 3/4 × 10 3/8 in. (17.1 × 26.4 cm), National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, 2014.18.56.

When Stang consigned his two Seurat paintings to Gold on December 18, 1928, the dealer had already negotiated the sale of both pictures, as attested by correspondence with César M. de Hauke from earlier in December and an invoice to de Hauke and Co. dated December 18, 1928; see letters exchanged between Gold and de Hauke, December 4, 1928 and December 6, 1928, Jacques Seligmann and Co. Records, Series 9.1.3, Box 394, Folder 18; and invoice from Gold, December 18, 1928, Jacques Seligmann and Co. Records, Series 9.7.2, Box 412, Folder 8.

De Hauke and Co. purchased the two Seurat paintings on joint account with Alex Reid and Lefèvre; see letter from A. J. McNeill Reid to César M. de Hauke requesting an invoice for Alex Reid and Lefèvre’s half-share in the pictures, which the French dealer Étienne Bignou had secured in their name, December 27, 1928, Jacques Seligmann and Co. Records, Series 9.3.1, Box 406, Folder 1. De Hauke and Co. billed Alex Reid and Lefèvre for their half-share on January 8, 1929; see invoice dated January 8, 1929, Jacques Seligmann and Co. Records, Series 9.3.2, Box 406, Folder 4. The invoice stipulates that de Hauke and Co. and Alex Reid and Lefèvre would share the profits fifty-fifty after de Hauke and Co. had deducted their 10% seller’s commission.

Bignou had no ownership share in Study for “Bathers at Asnières”. In a memorandum to James Saint Laurence O’Toole, gallery manager of the New York branch of de Hauke and Co., César M. de Hauke states that “Bignou is not entitled to anything in these pictures, because he did not buy them”; see memorandum from de Hauke to O’Toole, February 25, 1929, Jacques Seligmann and Co. Records, Series 9.2, Box 405, Folder 10. However, Bignou likely received a finder’s commission; see email from Christel H. Force, independent art historian, to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, September 7, 2021, NAMA curatorial files. The Nelson-Atkins painting appears in two Bignou photo albums with the stock number 1285; see Musée d’Orsay, Albums Bignou, ODO1996-29, Bobine N°23, Boîte 27, Seurat, Clichés 444 à 559; and Wildenstein Plattner Institute, Galerie Étienne Bignou Photo Archive (ca. 1909–1950), Georges Seurat.

In mid-February 1929, de Hauke and Co. transferred Study for “Bathers at Asnières” and Stang’s other Seurat panel from Paris to their New York office. The paintings arrived in New York by March 2, 1929; see letter from de Hauke to Lee Simonson, March 2, 1929, Jacques Seligmann and Co. Records, Series 9.1.7, Box 405, Folder 4. Four days later, M. Knoedler and Co. purchased Study for “Bathers at Asnières” and two other works by Seurat (not including the second picture from Stang); see invoice dated March 6, 1929, Jacques Seligmann and Co. Records, Series 9.7.2, Box 411, Folder 1. Once M. Knoedler and Co. had paid their balance, de Hauke and Co. compensated Alex Reid and Lefèvre for their share in the profits; see debit dated May 14, 1929 on page 153 of de Hauke and Co.’s cashbook for 1926–1930, Jacques Seligmann and Co. Records, Series 9.7.1, Box 408, Folder 3.

For the first Alex Reid and Lefèvre stock number, see Pictures Sold, 1926–1934, sheet no.177, Alex Reid and Lefèvre records (TGA 200211), Tate Library and Archive, London; and email from Darragh O’Donoghue, Tate Library and Archive, to Glynnis Napier Stevenson, NAMA, October 30, 2018, NAMA curatorial files. For the second Alex Reid and Lefèvre stock number, see email from Alexander M. D. Corcoran, Lefèvre Fine Art Ltd., to MacKenzie Mallon, NAMA, March 18, 2019, NAMA curatorial files.

[8] For the purchase date of March 6, 1929, see M. Knoedler and Co. Records, approximately 1848–1971, The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, accession no. 2012.M.54, Series I.A, Box 8, Painting stock book 8, page 71 (hereafter cited as M. Knoedler and Co. Records). For the sale date of March 20, 1929, see M. Knoedler and Co. Records, Series II, Box 75, Sales book 15, page 65. The stock number A565 appears twice on the verso of Study for “Bathers at Asnières,” both as a paper label and a handwritten inscription.

[9] For the return date of August 31, 1931, see M. Knoedler and Co. Records, Series II, Box 73, Sales book 13, page 219. In other documents, the return date is listed as September 1931; see M. Knoedler and Co. Records, Series IV, Box 163, inventory card for A1379. We have defaulted to the earlier date. At the time of return, Study for “Bathers at Asnières” was assigned a second stock number, A1379, which appears twice on the painting’s verso, both as a paper label and a handwritten inscription.

[10] For the purchase date of January 28, 1933, see M. Knoedler and Co. Records, Series II, Box 75, Sales book 15, page 159.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Georges Seurat, Study for “Bathers at Asnières,” 1883,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.724.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Georges Seurat, Study for “Bathers at Asnières,” 1883,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.724.4033.

Georges Seurat, The Riverbank, Study for “Bathers at Asnières”, ca. 1882–83, oil on panel, 6 5/16 x 9 13/16 in. (16 x 25 cm), Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, Glasgow, 2422.

Georges Seurat, Bathers, Study for “Bathers at Asnières”, 1883–84, oil on panel, 6 1/4 x 9 7/8 in. (15.9 x 25.1 cm), National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, 2014.18.54.

Georges Seurat, Horse and Boats, Study for “A Bathing Place, Asnières”, 1883–84, oil on panel, 6 1/4 x 9 7/8 in. (15.9 x 25.1 cm), National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, 2014.18.55.

Georges Seurat, Horses in the Water, Study for “A Bathing Place, Asnières”, 1883–84, oil on panel, 6 x 9 3/4 in. (15.2 x 24.8 cm), private collection, on long-term loan to The Courtauld, London.

Georges Seurat, Clothes on the Grass, Study for “A Bathing Place, Asnières”, 1883, oil on panel, 6 3/8 x 9 3/4 in. (16.2 x 24.8 cm), Tate, London, on loan to the National Gallery, London, N04203.

Georges Seurat, The Seine with Clothing on the Bank, Study for “A Bathing Place, Asnières”, 1883–84, oil on panel, 6 3/4 x 10 3/8 in. (17.2 × 26.4 cm), National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, 2014.18.56.

Georges Seurat, Study for “Bathers at Asnières”, 1883, oil on panel, 6 1/8 x 9 13/16 in. (15.5 x 25 cm), Musée d’Orsay, Paris, RF 1965 13.

Georges Seurat, The Rainbow, Study for “Bathers at Asnières”, 1883, oil on panel, 6 1/8 x 9 5/8 in. (15.5 x 24.5 cm), the National Gallery, London, NG6555.

Georges Seurat, Study for “Bathers at Asnières”, ca. 1883–84, oil on panel, 6 3/16 x 9 13/16 in. (15.7 x 24.9 cm), Cleveland Museum of Art, 1958.51.

Georges Seurat, Study for “Bathers at Asnières”, 1883–84, oil on wood, 6 x 9 13/16 in. (15.2 x 25 cm), the National Gallery, London, NG6561.

Georges Seurat, Study for “Bathers at Asnières”, ca. 1883, oil on panel, 6 1/4 x 9 7/8 in. (15.9 x 25 cm), National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh, NG 2222.

Georges Seurat, Final Study for “Bathers at Asnières”, 1883, oil on panel, 6 1/4 × 9 7/8 in. (15.8 × 25.1 cm), Art Institute of Chicago, 1962.578.

Georges Seurat, Echo, Study for “Bathers at Asnières”, 1883–84, Conté crayon on Michallet paper, 12 15/16 x 9 7/16 in. (31.2 × 24 cm), Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT, 1966.80.11.

Georges Seurat, Seated Nude, Study for “Bathers at Asnières”, 1883, Conté crayon on cream paper, 12 1/2 x 9 3/4 in. (31.7 x 24.7 cm), National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh, D 5110.

Georges Seurat, Boy Seen from Behind, Study for “A Bathing Place, Asnières”, 1883–84, Conté crayon on paper, 12 1/2 x 9 1/2 in. (31.8 x 24.1 cm), private collection, cited in John Leighton and Richard Thomson, Seurat and The Bathers, exh. cat. (London: National Gallery Publications, 1997), 65.

Georges Seurat, A Pair of Legs, Study for “Bathers at Asnières”, 1883–84, Conté crayon on paper, 9 7/16 x 12 in. (24 x 30.5 cm), Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, NMH 50/2014.

Georges Seurat, Hat, Shoes, and Undergarments, Study for “A Bathing Place, Asnières”, 1883–84, black chalk on off-white modern laid paper, 9 5/16 x 12 3/16 in. (23.6 x 30.9 cm), Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Cambridge, MA, 1993.231.

Georges Seurat, Bust of a Sleeping Man, Study for “A Bathing Place, Asnières”, 1883–84, Conté crayon on Chamois paper, 9 7/16 x 11 13/16 in. (24 x 30 cm), Berggruen collection.

Georges Seurat, The Sleeper, Study for “Bathers at Asnières”, 1883–84, Conté crayon on paper, 9 3/8 x 12 3/16 in. (23.8 x 31 cm), Musée du Louvre, Paris, RF 29539, Recto.

Georges Seurat, Reclining Man, Study for “Bathers at Asnières”, 1883–84, Conté crayon on Michallet paper, 9 5/8 x 12 3/8 in. (24.5 x 31.5 cm), Fondation Beyeler, Basel, Inv.50.1.

Georges Seurat, Seated Boy with Straw Hat, Study for “A Bathing Place, Asnières”, 1883–84, Conté crayon on Michallet paper, 9 1/2 × 12 1/4 in. (24.1 × 31.1 cm), Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT, 1960.9.1.

Georges Seurat, Study for “Bathers at Asnières”, 1883–84, Conté crayon on paper, 12 3/4 x 9 1/2 in. (32.4 x 24.1 cm), location unknown, cited in Impressionist and Modern Art Evening Sale (London: Sotheby’s, February 3, 2015), 80–81.

Georges Seurat, Bathers at Asnières, 1884, oil on canvas, 79 1/8 x 118 1/8 in. (201 x 300 cm), the National Gallery, London, NG3908.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Georges Seurat, Study for “Bathers at Asnières,” 1883,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.724.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Georges Seurat, Study for “Bathers at Asnières,” 1883,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.724.4033.

Works in Oil and Pastel by the Impressionists of Paris, The American Art Galleries, New York, April 10–28, 1886; National Academy of Design, New York, opened May 25, 1886, no. 133.

Société des Artistes Indépendants: 3e exposition, Pavillon de la Ville de Paris, Paris, March 26–May 3, 1887, no. 447.

Neuvième exposition annuelle des XX, Musée d’Art Moderne, Brussels, February 6–March 6, 1892, no. 1.

Den franske utstilling i Kunstnerforbundet, Kunstnerforbundet, Kristiania (Oslo), January 19–February 18, 1918, no. 87, as La Seine à Courbevoie.

First Loan Exhibition: Cézanne, Gauguin, Seurat, Van Gogh, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, November 7–December 7, 1929, no. 62, as The Bank of the Seine.

Since Cézanne, Valentine Gallery, New York, December 28, 1931–January 16, 1932, unnumbered, as Étude pour la Baignade.

24 Paintings and Drawings by Georges-Pierre Seurat, The Renaissance Society of the University of Chicago, February 5–25, 1935, no. 4, as Study for “The Bathers”.

One Hundred Years: French Painting, 1820–1920, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, March 31–April 28, 1935, no. 52, as Study for “La Baignade”.

From Paris to the Sea Down the River Seine: An Exhibition for the Benefit of l’École Libre des Hautes Études, Wildenstein, New York, January 28–February 27, 1943, no. 25, as Study for La Baignade.

Seurat, 1859–1891: Paintings and Drawings; Loan Exhibition for the Benefit of the Home for the Destitute Blind, Knoedler Galleries, New York, April 19–May 7, 1949, no. 3, as Etude pour La Baignade.

An Exhibition of French Painting: David to Cézanne, The Norton Gallery and School of Art, West Palm Beach, FL, February 4–March 1, 1953; The Lowe Gallery, University of Miami, Coral Gables, FL, March 11–31, 1953, no. 20, as La Baignade.

A Loan Exhibition of Seurat and His Friends: For the Benefit of the Scholarship Fund of L’Alliance Française de New York, Wildenstein, New York, November 18–December 26, 1953, no. 3, as Study for “Une Baignade”.

Three Centuries of French Painting, Wichita Art Museum, Wichita, KS, May 9–23, 1954, no. 21, as Study for “La Baignade”.

Painting: School of France, Atlanta Art Association Galleries, September 20–October 4, 1955; The Birmingham Museum of Art, October 16–November 5, 1955, no. 26, as La Baignade.

Seurat: Paintings and Drawings, The Art Institute of Chicago, January 16–March 7, 1958; The Museum of Modern Art, New York, March 24–May 11, 1958, no. 58, as Sketch of “The Bathers”.

Landscape into Art: A Loan Exhibition of Paintings from the XV Century to Our Day Under the Auspices of the Atlanta Art Association and of its Women’s Committee and Browse, Borrow, and Buy Gallery, Atlanta Art Association Galleries, February 6–25, 1962, no. 54, as Study for La Baignade.

Impressionism: Selections from Five American Museums, The Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, November 4–December 31, 1989; The Minneapolis Institute of Arts, January 27–March 25, 1990; The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, April 21–June 17, 1990; The Saint Louis Art Museum, July 14–September 9, 1990; The Toledo Museum of Art, September 30–November 25, 1990, no. 75, as Study of A Bathing Place, Asnières.

Seurat, Galeries nationales du Grand Palais, Paris, April 9–August 12, 1991, no. 108, as Baigneur nu.

Georges Seurat, 1859–1891, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, September 24, 1991–January 12, 1992, no. 109, as Baigneur nu.

Seurat and The Bathers, The National Gallery, London, July 2–September 28, 1997, no. 12, as Two Seated Figures: Study for “Bathers at Asnières”.

Seurat and the Making of “La Grande Jatte”, The Art Institute of Chicago, June 16–September 19, 2004, no. 19, as Two Seated Figures (study for “Bathing Place, Asnières”).

The Clark Brothers Collect: Impressionist and Early Modern Paintings, Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, MA, June 4–September 4, 2006; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, May 22–August 19, 2007, unnumbered, as Study for “Bathers at Asnières”.

Un été au bord de l’eau: Loisirs et impressionnisme, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Caen, April 27–September 29, 2013, no. 55, as Baigneur nu (étude pour “Une baignade, Asnières”).

References

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Georges Seurat, Study for “Bathers at Asnières,” 1883,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.724.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Georges Seurat, Study for “Bathers at Asnières,” 1883,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.724.4033.

Works in Oil and Pastel by the Impressionists of Paris, exh. cat. (New York: American Art Galleries, 1886), 25.

Société des Artistes Indépendants: Catalogue des œuvres exposées; 3e exposition, exh. cat. (Paris: Société des Artistes Indépendants, 1887), 23 [repr., in Salons of the “Indépendants,” 1884–1891 (New York: Garland, 1981), unpaginated].

Les XX: Catalogue de la neuvième exposition annuelle, exh. cat. (Brussels: Imp. Vve Monnom, 1892), unpaginated.

“Clôture du Salon des XX,” L’Art moderne 12, no. 11 (March 13, 1892): 83.

Den franske utstilling i Kunstnerforbundet, exh. cat. (Kristiania [Oslo]: Centraltrykkeriet, 1918), 29, as La Seine à Courbevoie.

Johan H. Langaard, “Georges Seurat,” Kunst og Kultur 9 (January 1921): 38, (repro.), as Badescene.

[Adolphe] Tabarant, “Les Peintres à la campagne,” Le Bulletin de la vie artistique 2, no. 17 (September 1, 1921): 463, (repro.), as Bords de Seine (étude).

Gustave Coquiot, Georges Seurat (Paris: Albin Michel, 1924), 200.

Paul Jamot, “L’Art français en Norvège: Galerie nationale d’Oslo et collections particulières,” La Renaissance de l’art 12, no. 2 (February 1929): 100, (repro.), as Étude pour La Baignade.

First Loan Exhibition: Cézanne, Gauguin, Seurat, Van Gogh, exh. cat. (1929; repr., New York: Arno, 1972), 24, 44, (repro.), as The Bank of the Seine.

Kasper Niehaus, “Georges Seurat,” Elsevier’s Geїllustreerd Maandschrift 40, no. 79 (January–June 1930): (repro.), as La Baignade.

Robert Rey, La Renaissance du sentiment classique dans la peinture française à la fin du XIXe siècle (Paris: Éditions G. Van Oest, 1931), 122, 142, 144, 146.

Since Cézanne, exh. cat. (New York: Valentine Gallery, 1931), unpaginated, as Étude pour la Baignade.

Malcolm Vaughn, “Survey of French Painting: Since Cezanne Now on View,” New York American, no. 17,700 (January 3, 1932): M5.

“In Gallery and Studio,” Kansas City Star 53, no. 266 (June 10, 1933): 4.

Mrs. Henry Field, “‘The social whirl’,” Chicago Herald and Examiner 53, no. 173 (November 30, 1933): 25.

“Nelson Gallery of Art Special Number,” Art Digest 8, no. 5 (December 1, 1933): 14, 22, as Study for The Bathers.

“The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art, Kansas City Special Number,” Art News 32, no. 10 (December 9, 1933): 28, 30, 44, (repro.), as Study for the Bathers and Study for La Baigneuse.

Minna K. Powell, “The First Exhibition of the Great Art Treasures,” Kansas City Star 54, no. 84 (December 10, 1933): 4C.

“Nelson Gallery of Art Opened at Kansas City,” New York Herald Tribune 93, no. 31,802 (December 11, 1933): 12.

Luigi Vaiani, “Art Dream Becomes Reality with Official Gallery Opening at Hand,” Kansas City Journal-Post 80, no. 187 (December 11, 1933): 7, as The Bathers.

Paul V. Beckley, “Art News,” Kansas City Journal-Post 80, no. 193 (December 17, 1933): 2C, as Study for La Baignade.

The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Handbook of the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1933), 41, 55, 138, (repro.), as Study for the Bathers.

A. J. Philpott, “Kansas City Now in Art Center Class,” Boston Sunday Globe 125, no. 14 (January 14, 1934): 16.

M[inna] K. P[owell], “Cezanne and the Patches of Color by Which He Transformed Modern Art,” Kansas City Star 54, no. 120 (January 15, 1934): [16]D, as Study for “The Bathers”.

“A Thrill to Art Expert: M. Jamot is Generous in his Praise of Nelson Gallery,” Kansas City Times 97, no. 247 (October 15, 1934): 7, as Study for “The Bathers”.

“In Gallery and Studio: News and Views of the Week in Art,” Kansas City Star 55, no. 32 (October 19, 1934): 18.

“Women’s Club Calendar,” Kansas City Star 55, no. 111 (January 6, 1935): 11C, as Study for the Bathers.

M[inna] K. P[owell], “In Gallery and Studio: News and Views of the Week in Art,” Kansas City Star 55, no. 186 (March 22, 1935): [D2].

24 Paintings and Drawings by Georges-Pierre Seurat, exh. cat. (Chicago: Renaissance Society of the University of Chicago, 1935), unpaginated, (repro.), as Study for “The Bathers”.

One Hundred Years: French Painting, 1820–1920, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1935), unpaginated, as Study for “La Baignade”.

P[aul] V. B[eckley], “Art News,” Kansas City Journal-Post 81, no. 197 (April 7, 1935): 8-B.

“Wilmington Sees Old Masters’ Art,” New York Times 84, no. 28,202 (April 12, 1935): 21.

C[larence] J[oseph] Bulliet, The Significant Moderns and their Pictures (New York: Halcyon House, 1936), unpaginated, (repro.), as The Bathers (Study).

“Museum Directors Have to Play Detective Now and Then,” Kansas City Star 58, no. 210 (April 15, 1938): 14.

Robert J. Goldwater, “Some Aspects of the Development of Seurat’s Style,” Art Bulletin 23, no. 2 (June 1941): 121, 126n27.

Benedict Nicolson, “Seurat’s La Baignade,” Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 79, no. 464 (November 1941): 140–41, 145, (repro.), as Etude pour “La Baignade”.

The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, The William Rockhill Nelson Collection, 2nd ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1941), 41, 52, 168, (repro.), as Study for “The Bathers”.

“Loans from the Phillips Memorial Gallery,” Gallery News (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) 8, no. 6 (March 1942): 6.

“Swedes Visit Gallery,” Kansas City Times 105, no. 196 (August 17, 1942): 3.

John Rewald, Georges Seurat, trans. Lionel Abel (New York: Wittenborn, 1943), xiii, 10, 12, 18, 78n117, 87, (repro.), as The Bank of the Seine, Study for “Une Baignade”.

From Paris to the Sea Down the River Seine: An Exhibition for the Benefit of l’École Libre des Hautes Études, exh. cat. (New York: Wildenstein, 1943), unpaginated, as Study for La Baignade.

Edward Alden Jewell, “Paris to the Sea Exhibition Theme: Loan Display of Paintings by 19th Century Artists Opens Today at Wildenstein’s,” New York Times 92, no. 31,049 (January 27, 1943): 26.

Douglas Cooper, Georges Seurat: Une Baignade, Asnières, in the Tate Gallery, London (London: Percy Lund Humphries, [1946]), 8, 12–14, 24, (repro.), Study for “Une Baignade”.

Germain Seligman, The Drawings of Georges Seurat (1946; repr., New York: Curt Valentin, 1947), 38.

The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, The William Rockhill Nelson Collection, 3rd ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1949), 66, (repro.), as Study for “The Bathers”.

Seurat, 1859–1891: Paintings and Drawings; Loan Exhibition for the Benefit of the Home for the Destitute Blind (New York: Knoedler Galleries, 1949), unpaginated, (repro.), as Etude Pour La Baignade.

Howard Devree, “Seurat Art Show Will Assist Blind: Paintings and Drawings by Post-Impressionist Artist to Be on View at Knoedler’s,” New York Times 98, no. 33,323 (April 19, 1949): 23.

Jacques de Laprade, Seurat (Paris: Éditions Aimery Somogy, 1951), 14, 22, 81, 89, 93, (repro.), as Étude pour “Une Baignade”.

A Loan Exhibition of Seurat and His Friends: For the Benefit of the Scholarship Fund of L’Alliance Française de New York, exh. cat. (New York: Wildenstein, 1953), 8, 21, (repro.), as Study for “Une Baignade”.

An Exhibition of French Painting: David to Cézanne, exh. cat. ([West Palm Beach, FL]: [Norton Gallery and School of Art], [1953]), unpaginated, as La Baignade.

Raymond Cogniat, Seurat, trans. Lucy Norton (New York: Hyperion Press, [1953]), 35, (repro.), as Study for The Bathers.

Three Centuries of French Painting, exh. cat. (Wichita: Wichita Art Museum, 1954), unpaginated, as Study for “La Baignade”.

Painting: School of France, exh. cat. (Chamblee, GA: Colonial Press, 1955), unpaginated, as La Baignade.

Daniel Catton Rich, ed., Seurat: Paintings and Drawings, exh. cat. (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 1958), 9, 13, 29, 54, (repro.), as Sketch for “The Bathers”.

Robert L. Herbert, “Seurat in Chicago and New York,” Burlington Magazine 100, no. 662 (May 1958): 150.

Ronald Alley, The Foreign Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture (London: Tate Gallery, 1959), 243.

Henri Dorra and John Rewald, Seurat: L’Œuvre peint; Biographie et catalogue critique (Paris: Les Beaux-Arts, 1959), no. 96, pp. XLV, LIX, LXXV, LXXVIn59, CXV, 88, 95, 97–98, 302, 307–10, (repro.), as Baigneur assis, étude pour “Une Baignade”.

Ross E. Taggart, ed., Handbook of the Collections in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 4th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1959), 124, 261, (repro.), as Study for “La Baignade”.

Michael Ayrton, “Une Baignade, Asnières,” Painting of the Month (April 1960): unpaginated, (repro.), as Study of two bathers.

Michael Ayrton, “Painting of the Month: Seurat’s ‘Une Baignade, Asnières,’” The Listener and B.B.C. Television Review 63, no. 1620 (April 14, 1960): 662.

Kenneth Clark, Looking at Pictures (New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1960), 136–37.

Ole Mæhle, Streiftog og glimt: Fra Kunstnerforbundets første 50 år (Oslo: Gyldendal Norsk Forlag, 1960), 59.

C[ésar] M[ange] de Hauke, Seurat et son œuvre (Paris: Gründ, 1961), no. 91, pp. 1:XXV, XXVIII, XXX, 52–53, 197–98, 217, 221, 229, 273, 293, (repro.); 2:309, 311–12, 314, 316, 318, 323–26, 330, as La Seine et Baigneur Nu Assis Sur La Berge.

Robert L. Herbert, Seurat’s Drawings (New York: Shorewood, 1962), 101, 104.

Landscape into Art: A Loan Exhibition of Paintings from the XV Century to Our Day Under the Auspices of the Atlanta Art Association and of its Women’s Committee and Browse, Borrow and Buy Gallery, exh. cat. (Atlanta: Atlanta Art Association, 1962), unpaginated, as Study for La Baignade.

William Innes Homer, Seurat and the Science of Painting (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1964), 55, 60, 62, 65–66, 77, 88–89, 91, 96, 99–100, 103.

David Sylvester, Ten Modern Artists: An Introduction to Twentieth-Century Painting and Sculpture (London: British Broadcasting Corporation, 1964), unpaginated, (repro.), as Study for “Bathing at Asnières”.

John Russell, Seurat (New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1965), 9, 12, 115, 131, 279, (repro.), as La Seine et Baigneur Nu assis sur la Berge.

Seurat (London: Phaidon, 1965), 38, 79, 87, (repro.), as Study for “Bathing at Asnières” and Bather Seated.

Henri Perruchot, La vie de Seurat (Paris: Hachette, 1966), 33–34.

Phoebe Pool, Impressionism (1967; repr., London: Thames and Hudson, 1970), 218, 220, 279, 286, (repro.), as Study for Une Baignade.

Jean Sutter, Les Néo-impressionnistes (Neuchâtel, Switzerland: Editions Ides et Calendes, 1970), 14, 19, 28.

André Chastel and Fiorella Minervino, L’opera completa di Seurat (Milan: Rizzoli Editore, 1972), no. 96, pp. 16, 27, 84–85, 88, 96–98, 116–19, (repro.), as Bagnante seduto in riva alla Senna.

André Chastel and Fiorella Minervino, Tout l’œuvre peint de Seurat, trans. Simone Darses (Paris: Flammarion 1973), no. 96, pp. 16, 27, 84–85, 88, 96–99, 116–19, (repro.), as Baigneur assis. Étude pour “Une Baignade”.

Mitsuhiko Kuroe, ピサロ/シスレー/スーレ = Pissarro/Sisley/Seurat ([Tokyo]: Shueisha, 1973), 139, (repro.), as Baigneur assis, étude pour “Une Baignade”.

Russell Lynes, Good Old Modern: An Intimate Portrait of The Museum of Modern Art (New York: Atheneum, 1973), 60.

Ross E. Taggart and George L. McKenna, eds., Handbook of the Collections in The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Kansas City, Missouri, vol. 1, Art of the Occident, 5th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1973), 166, 259, (repro.), as Study for “La Baignade”.

René Huyghe, La Relève du réel: la peinture française au XIXe siècle; impressionnisme, symbolisme (Paris: Flammarion, 1974), 254, 464, (repro.), as Baigneur assis. Étude pour “Une baignade, Asnières”.

Norma Broude, ed., Seurat in Perspective (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1978), 85, 127–28.

Seurat: Paintings and Drawings, exh. cat. (London: David Carritt Limited, 1978), 39, 41–42.

Sophie Monneret, L’Impressionnisme et son époque: Dictionnaire international illustré (Paris: Éditions Denoël, 1979), 2:242, as Baigneur assis.

[Sarane] Alexandrian, Seurat, trans. Alice Sachs (New York: Crown, 1980), 22, 31, 33, 95–96, (repro.), as Study for “Une Baignade”.

Bogomila Welsh-Ovcharov, Vincent van Gogh and the Birth of Cloisonism, exh. cat. (Toronto: Art Gallery of Ontario, 1981), 287n8.

Charles F. Stuckey, Seurat (Mount Vernon, NY: Artist’s Limited Edition, 1984), 11.

The Great Artists: Their Lives, Works and Inspiration, pt. 9, Seurat (1985): 268.

Richard Thomson, Seurat (Oxford: Phaidon, 1985), 56, 64, 79, 82–84, 97, 157, as Seated Bather.

Richard R. Brettell, French Impressionists (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 1987), 87, 89.

Peter J. Flagg, “The Neo-Impressionist Landscape” (PhD diss., Princeton University, 1988), 58–60.

Marc S. Gerstein, Impressionism: Selections from Five American Museums, exh. cat. (New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1989), 12, 20, 90, 152, 172–74, 180, 186, 202, (repro.), as Study for A Bathing Place, Asnières.

David Lewis, “Museum Impressions,” Carnegie Magazine 59, no. 12 (November–December 1989): 46.

Toni Wood, “Impressionists broke all the rules,” Kansas City Star 110, no. 184 (April 15, 1990): H-4.

“At the Nelson,” Kansas City Star 110, no. 189 (April 20, 1990): C-10.

Catherine Grenier, Seurat: Catalogo completo dei dipinti (Florence: Cantini Editore, 1990), no. 97, pp. 7, 60–61, 63, 152–53, 155, (repro.), as Bagnante seduto, studio per “Une baignade”.

Alain Madeleine-Perdrillat, Seurat (New York: Rizzoli, 1990), 48, 53, 56.

John Rewald, Seurat: A Biography (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1990), 51, 67, 70, 214n2, 219n3, 224, (repro.), as Seated Bather (study for “Bathers, Asnières”).

Françoise Cachin and Robert L. Herbert, Seurat, exh. cat. (Paris: Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 1991), 34, 37, 142, 164, 176, 184–85, 187, 190, 194–96, 198, 218, 346, 428, 466, (repro.), as Baigneur nu.

Robert Fohr, “Une Baignade, Asnières, 1883–1884,” Le Dossier de l’art, no. 1 (April–May 1991): 10, 12, 15, (repro.), as “Baigneur assis” (étude pour “Une Baignade Asnières”).

R[obert] F[ohr], “Seurat en quelques points,” L’Objet d’Art, no. 247 (May 1991): 6.

Anne Distel, Seurat ([Paris]: Chêne, 1991), 10–11, 65, 160, (repro.), as Baigneur assis, étude pour “Une Baignade, Asnières”.

Catherine Grenier, Seurat: Catalogue complet des peintures (Paris: Bordas, 1991), no. 97, pp. 7, 60–61, 63, 152–53, 155, (repro.), as Baigneur assis, étude pour Une baignade, Asnières.

Robert L. Herbert, Georges Seurat, 1859–1891, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1991), ix, 104, 127–28, 139, 141, 149–51, 154, 159, 161, 163, 181, 302, 380, 403, 406, 413–414, 416–19, 433, 446, (repro.), as Baigneur nu / Seated Bather.

Michael Kimmelman, “Seurat: The Enigma Behind the Luster,” New York Times 141, no. 48,731 (September 22, 1991): H35.

Hélène Seyrès, Seurat: Correspondances, témoignages, notes inédites, critiques (Paris: Acropole, 1991), 92–93, 137, 288.

Richard Tilston, Seurat (1991; repr., New York: Smithmark, 1992), 11.

Michael F. Zimmermann, Seurat and the Art Theory of his Time (Antwerp: Fonds Mercator, 1991), 70, 94, 138, 149, 154, 158, 160, 171, 279, 458n89, (repro.), as Study for “Une Baignade”.

Sarah Carr-Gomm, Seurat (London: Studio Editions, 1993), 15–16, 24, 64, 68–69, 72, 143, (repro.), as Study for “Une Baignade, Asnières”.

Bernard Denvir, The Chronicle of Impressionism: A Timeline History of Impressionist Art (Boston: Little, Brown, 1993), 279.

Ingo F. Walther, ed., Impressionism 1860–1920, trans. Michael Hulse, pt. 1, Impressionism in France (1993; repr., Cologne: Benedikt Taschen Verlag, 2013), 254, 258, 281, 696, (repro.), as Bather (Study for “Bathing at Asnières”).

Roger Ward and Patricia J. Fidler, eds., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collection (New York: Hudson Hills Press, in association with Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1993), 131, 210, (repro.), as Study for “A Bathing Place, Asnières”.

Kristie C. Wolferman, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: Culture Comes to Kansas City (Columbia, MO: Columbia University of Missouri Press, 1993), 139, as Study for the Bathers.

Alice Thorson, “Art Notes,” Kansas City Star 117, no. 166 (March 2, 1997): K-5, (repro.).

John Leighton and Richard Thomson, Seurat and The Bathers, exh. cat. (London: National Gallery Publications, 1997), 7, 9, 11, 23, 28, 44, 51–53, 61–64, 68–69, 79, 82, 83n2, 154–55, (repro.), as Two Seated Figures: Study for “Bathers at Asnières”.

Simon Tait, “Draw of modern masters,” Times (London), no. 65,869 (April 21, 1997): 7, (repro.).

John Russell, “Glimmerings of Insight Into the Inscrutable Seurat,” New York Times 146, no. 50,894 (August 24, 1997): H35.

Carol McKay, “Presence and Absence: Seurat and the Bathers, National Gallery, London, 2nd July 28th–September 1997,” History Workshop Journal, no. 45 (Spring 1998): 243.

Aimée Brown Price, “How the Bathers Emerged,” Art in America 85, no. 12 (December 1997): 57, 60, 63, (repro.), as Two Seated Figures: Study for “Bathers at Asnières”.

Hajo Düchting, Georges Seurat, 1858–1891: Master of Pointillism (Cologne: Benedikt Taschen Verlag, 1999), 22.

Peter Paquet, Helldunkel, Raum und Form: Georges Seurat als Zeichner: Mit einem Anhang, Seurats schriftliche Selbstzeugnisse und annotierter Bibliographie (Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 2000), 118, 120, 149, 154, and 193.

Torsten Gunnarsson et al., Impressionism and the North: Late 19th Century French Avant-Garde Art and the Art in the Nordic Countries 1870–1920, exh. cat. (Stockholm: Nationalmuseum, 2002), 238, 300n10.

Vivien Hamilton, Millet to Matisse: Nineteenth- and Twentieth-Century French Painting from Kelvingrove Art Gallery, Glasgow, exh. cat. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002), 3, 152.

Mike Venezia, Georges Seurat (New York: Children’s Press, 2002), 22–23, (repro.), as Study for Une Baignade, Asnières.

Robert L. Herbert, Seurat and the Making of “La Grande Jatte”, exh. cat. (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2004), 42, 44–45, 68, 75, 118, 131n2, 272, 281, 287, (repro.), as Two Seated Figures (study for “Bathing Place, Asnières”).

Le néo-impressionnisme de Seurat à Paul Klee, exh. cat. (Paris: Réunion de musées nationaux, 2005), 108, 390.

Michael Conforti et al., The Clark Brothers Collect: Impressionist and Early Modern Paintings (Williamstown, MA: Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, 2006), 146–47, 153, 306, 344, (repro.), as Study for “Bathers at Asnières”.

Michael Frensch, Seurat’s Bridge: From Impressionism to Modern Art, trans. Matthew Barton, rev. ed. (2006; Schaffhausen, Switzerland: Novalis Media, 2007), 40, 43, (repro.), as Baigneur nu [Naked Bather].

Marina Ferretti Bocquillon, Georges Seurat, Paul Signac e i neoimpressionisti, exh. cat. (Milan: Skira, 2008), 246.

Deborah Emont Scott, ed., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collection, 7th ed. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2008), 123, (repro.), as Study for “Bathers at Asnières”.

Christoph Becker and Julia Burckhardt Bild, George Seurat: Figure in Space, exh. cat. (Zurich: Kunsthaus Zürich, 2009), 37.

Michael Clarke, Poussin to Seurat: French Drawings from the National Gallery of Scotland, exh. cat. (Edinburgh: National Galleries of Scotland, 2010), 122, 122n2.

Peter H. Feist, Impressionism 1860–1920, Part I, Impressionism in France, ed. Ingo F. Walther (Cologne: Taschen, 2013), 254, 258, 281, 696, (repro.), as Bather (Study for “Bathing at Asnières”) / Baigneur assis.

Patrick Ramade, Un été au bord de l’eau: Loisirs et impressionnisme, exh. cat. (Paris: Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux-Grand Palais, 2013), 116–17, 140, (repro.), as Baigneur nu (étude pour “Une baignade, Asnières”).

Marieke Jooren, Suzanne Veldink, and Helewise Berger, Seurat, exh. cat. (Otterlo: Kröller-Müller Museum, 2014), 74, 122–23, 126, 138n2, (repro.).

Catherine Futter et al., Bloch Galleries: Highlights from the Collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2016), 103, (repro.), as Study for “Bathers at Asnières”.

Nils Messel, The Impressionist Trail: The What, Whence and Whither of French masterpieces in Norway, trans. Arlyne Moi (2016; Oslo: Messel Forlag, 2019), 150, 288n306, as Baigneur assis. Étude pour “Une Baignade”.

Heinz Widauer, ed., Seurat, Signac, Van Gogh: Ways of Pointillism, exh. cat. (Vienna: Albertina, 2016), 38, 42, 166.

Richard Thomson, Seurat’s Circus Sideshow, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2017), 108–09, 125n16.

Kelly Grovier, A New Way of Seeing: The History of Art in 57 Works (London: Thames and Hudson, 2019), 170.

Christel H. Force, ed., Pioneers of the Global Art Market: Paris-Based Dealer Networks, 1850–1950 (London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2020), 143, 153n49, 153n52, 154n74, as Etude pour La Baignade.

Nils Messel, Den Stangske Samling: Jørgen Breder Stangs franske bilder (Oslo: Messel Forlag, 2020), 13, 24–25, 55–56, 58, 146, (repro.), as Studie til Badende, Asnières / Baigneur assis, étude pour Une Baignade, Asnières.