Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “Armand Guillaumin, Morning, Rouen, November 1904,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.623.5407.

MLA:

Marcereau DeGalan, Aimee. “Armand Guillaumin, Morning, Rouen, November 1904,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.623.5407.

The French painter and printmaker Armand Guillaumin occupies a pivotal position between Impressionism and the avant-garde movements that followed. While historically associated with the Impressionists,1Guillaumin exhibited in six of the eight Impressionist exhibitions, including the inaugural exhibition in 1874. his career both anticipates and shapes the emergence of FauvismFauve: French for “wild beasts.” A term coined in 1905 by the conservative art critic Louis Vauxcelles (1870–1943) to mock Henri Matisse (1869–1954), André Derain (1880–1954), and other artists who exhibited at the Salon d’Automne that year. Vauxcelles objected to these artists’ bold, non-naturalistic colors, which were sometimes applied onto the canvas straight from the paint tube, and their simplified, unsystematically rendered forms, which gave their paintings an almost abstract appearance. The Fauves’ use of vibrant colors to communicate emotional states inspired artists associated with Expressionism and other twentieth-century avant-garde movements., an art movement named in 1905 after the French word fauve, or “wild beasts,” to describe its bold use of color, expressive brushwork, and simplified forms to convey emotion over realism. Decades earlier, critics like Joris-Karl Huysmans and Félix Fénéon had already recognized some of these tendencies in Guillaumin’s work, praising his “ferocious” yet unexpectedly delicate tonal contrasts and dubbing him a “frenzied colorist”—a striking departure from Impressionism’s focus on rendering the subtleties of natural light.2In 1881, Joris Karl Huysmans wrote, “M. Guillaumin est, lui aussi, un coloriste et, qui plus est, un coloriste féroce; au premier abord, ses toiles sont un margouillis de tons bataillants et de contours frustres, un amas de zébrures et de vermillon et de blue de Prusse; écartez-voux et clignez de l’oeil, le tout se remet en place, le plans s’assurent, le tons hurlants s’apaisent, les couleurs hostiles se concilient et l’on reste étonné de la délicatesse imprévue que prennent certaines parties de ces toiles” (Mr. Guillaumin is also a colorist, and what is more, a ferocious colorist; at first glance, his canvases are a jumble of battling tones and rough contours, a mass of zebra stripes and vermilion and Prussian blue; step aside and blink, everything falls back into place, the planes are assured, the screaming tones calm down, the hostile colors reconcile and one remains astonished by the unexpected delicacy that certain parts of these canvases take on). This and subsequent translations, unless otherwise noted, are by the author. Joris Karl Huysmans, “L’Exposition des Indépendants en 1881,” reprinted in Huysmans, L’Art Moderne, 2nd ed. (Paris: P. V. Stock, 1902), 261. For the Fénéon quote “ce coloriste forcené” (this frenzied colorist), see Félix Fénéon, “Les Impressionnistes,” La Vogue, June 13–20, 1886, 261–75, quoted in Ruth Berson, ed., The New Painting: Impressionism, 1874–1886 (San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1996), 1:443. Guillaumin’s 1904 painting Morning, Rouen exemplifies this evolution, capturing the city’s industrial port with bold, contrasting hues that prefigure the palettes of Fauve artists like Henri Matisse (1869–1954) and Othon Friesz (1879–1949). Through this work, Guillaumin bridges Impressionism’s explorations of light and Fauvism’s expressive celebration of pure color while also engaging with Rouen’s rich artistic legacy. Morning, Rouen underscores Guillaumin’s innovative approach to color and modernity, cementing his role as a key figure in the transition between these movements.

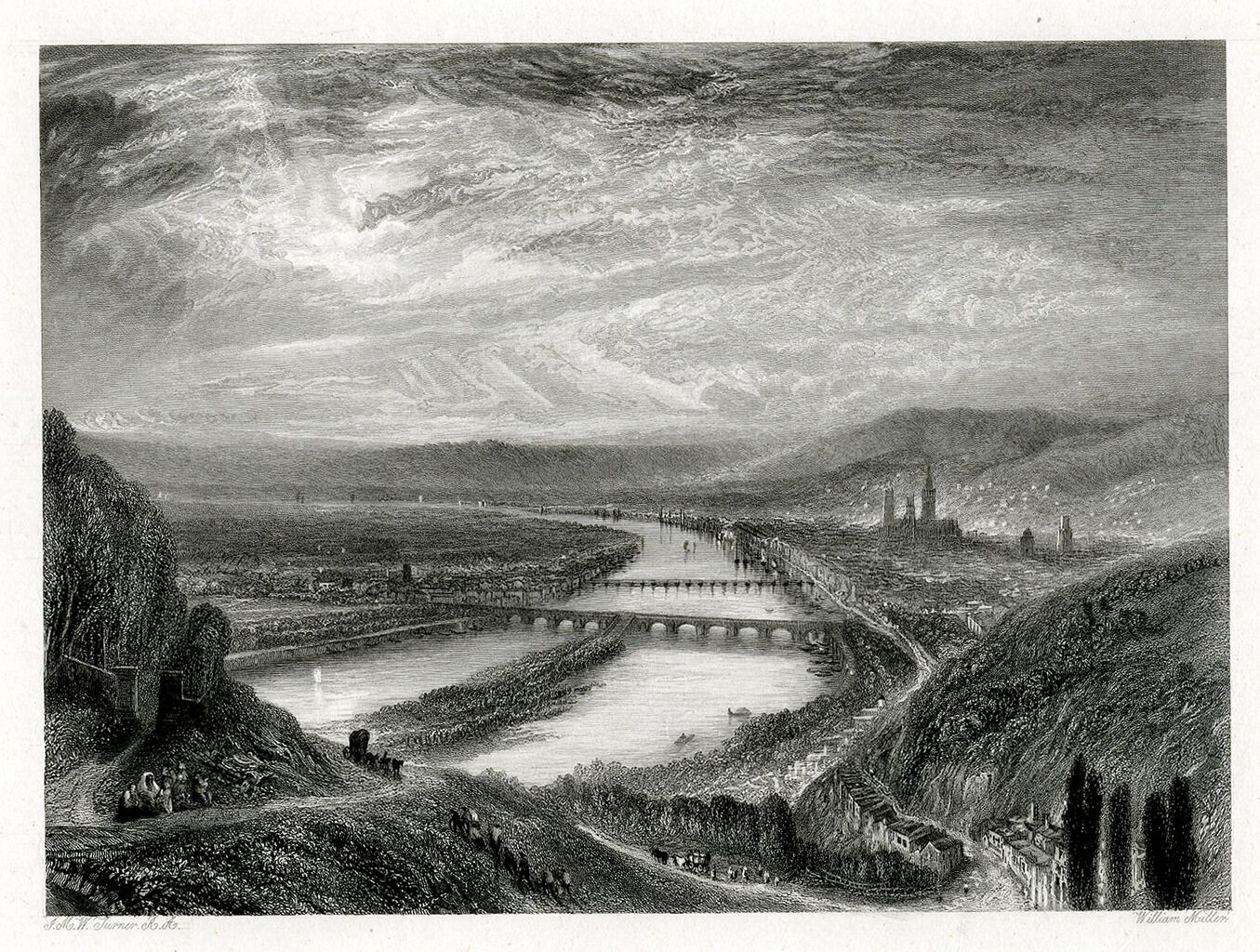

Rouen, located on a bend of the Seine River, about seventy-five miles from the open sea, has long captivated artists.3For an exhibition chronicling Rouen as an artistic site of inspiration during the Impressionist era, see Laurent Salomé, ed., A City for Impressionism: Monet, Pissarro, and Gauguin in Rouen, exh. cat. (Milan: Skira, 2010). Its industrial vibrance, Gothic architecture, and atmospheric light inspired artists like English painter Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851), whose watercolors, sketches,4See several examples at the Tate, including Joseph Mallord William Turner, View of Rouen from the Side of St. Catherine’s Hill, part of the Dieppe, Rouen, and Paris sketchbook, 1821, graphite on paper, 4 5/8 x 4 13/16 in. (11.8 x 12.3 cm), Tate, London, D24509, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/turner-view-of-rouen-from-the-side-of-st-catherines-hill-d24509. and later prints (Fig. 1)5The line engraving appeared in Turner’s Annual Tour, 1834: Wanderings by the Seine, which was part of a larger project titled River Scenery of Europe and engraved under Charles Heath’s supervision. See the catalogue entry on the website for the Tate, London, at https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/turner-rouen-from-st-catherines-hill-t04705 (accessed December 16, 2024). For a further discussion of the later publication of The Rivers of France (1837), in which the view of Rouen also appeared, see the Tate’s extended catalogue entry for Nantes, also from Turner’s Annual Tour, at https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/turner-nantes-t04678 (accessed December 16, 2024). profoundly influenced Impressionist painters Claude Monet (1840–1926) and Camille Pissarro (1830–1903).6Turner’s dynamic interplay of light and weather finds echoes in Claude Monet’s series of Rouen Cathedral paintings (1892–94). See, for example, Monet, Rouen Cathedral: The Portal (Sunlight), 1894, oil on canvas, 39 1/4 x 25 7/8 in. (99.7 x 65.7 cm), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 30.95.250, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/437124. Turner’s elevated view of Rouen also influenced Monet’s General View of Rouen, 25 1/2 x 39 5/16 in. (65 x 100 cm), Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rouen, 995.7.1, https://mbarouen.fr/en/oeuvres/general-view-of-rouen. Both Monet and Pissarro made repeated visits to Rouen from the 1870s to the 1890s, collectively realizing more than fifty compositions of various aspects of the city and its port.7Monet realized more than thirty views of the Rouen Cathedral, in addition to other general views of the city and surrounding countryside, whereas Camille Pissarro created more than twenty compositions in Rouen. See especially the latter’s painting Quai Napoléon, Rouen, 1883, oil on canvas, 21 3/8 x 25 3/8 in. (54.3 x 64.5 cm), Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1978-1-25, https://philamuseum.org/collection/object/72114, which is very similar to the Nelson-Atkins composition. For other Pissarro paintings of Rouen, see Joachim Pissarro and Claire Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Critical Catalogue of Paintings (Paris: Wildenstein Institute Publications, 2005), nos. 1218–1237, 3:761–71. Artists Paul Gauguin (1848–1903), Alfred Sisley (English, born Paris, 1839–99), and Charles Angrand (1854–1926) were also drawn to the city to create works of their own.8See, for example, Paul Gauguin, Street in Rouen, 1884, oil on canvas, 28 3/4 x 36 1/4 in. (73 x 92 cm), Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, inv. no. 552, https://www.museothyssen.org/en/collection/artists/gauguin-paul/street-rouen; and Alfred Sisley, Sahurs Meadows in Morning Sun, 1894, oil on canvas, 28 3/4 x 36 1/4 in. (73 x 92.1 cm), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1991.277.3, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/437683. Collectively, these artists established Rouen as a site for exploring both urban modernity and the fleeting effects of light. Guillaumin, in turn, built on this legacy, expanding beyond their light-focused techniques to explore bold color contrasts, while still considering atmospheric conditions.

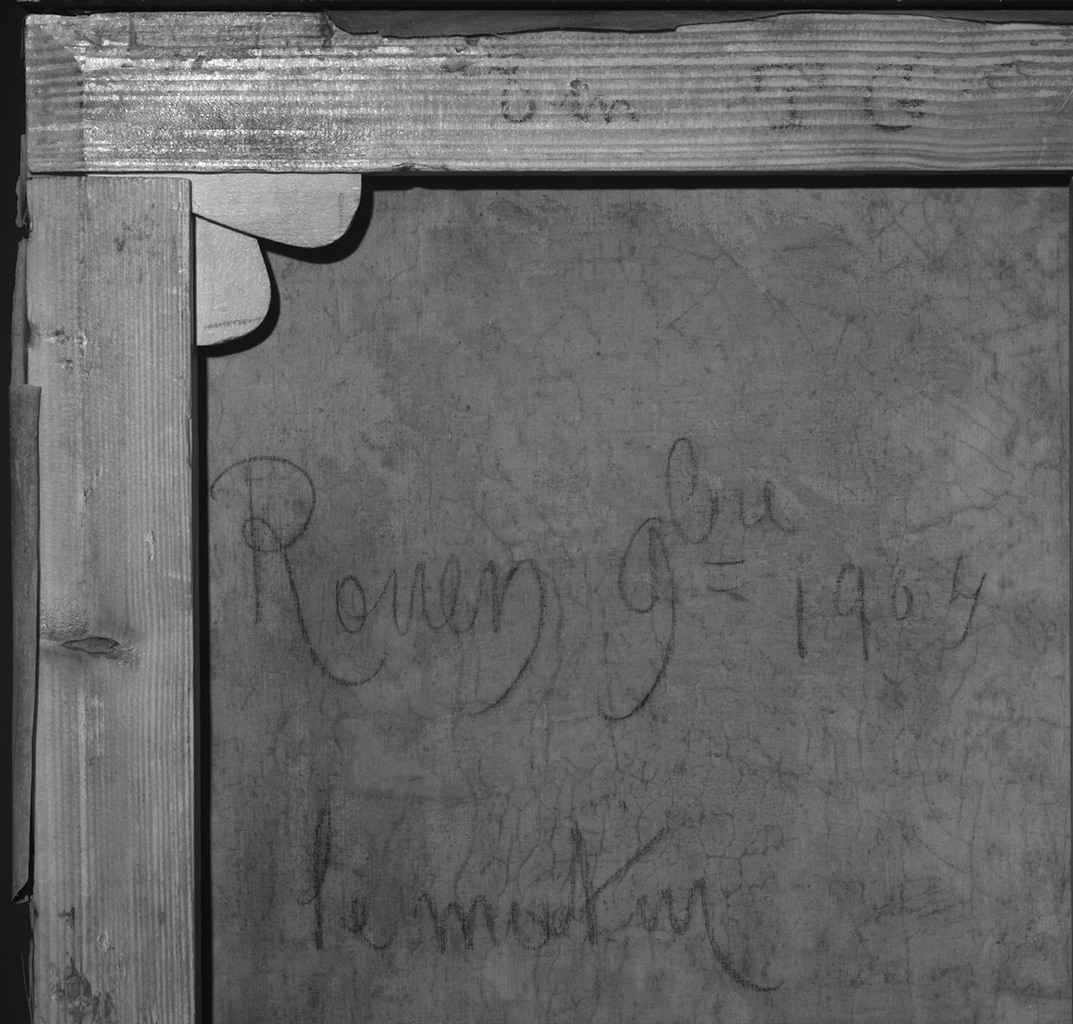

Guillaumin made two visits to Rouen in 1898 and 1904, producing at least ten views of the Seine from its banks.9See Armand Guillaumin, The Seine of Rouen, ca. 1898, oil on canvas, 15 1/8 x 18 1/8 in. (38.5 x 46 cm), sold at Christie’s, London, “Impressionist and Modern Art Day Sale,” June 23, 2016, lot 291, https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-6009060; Armand Guillaumin, The Banks of the Seine of Rouen, ca. 1898, oil on canvas, 18 1/8 x 24 in. (46 x 61 cm), sold at Sotheby’s, New York, “Impressionist and Modern Art Day Sale,” May 17, 2017, lot 193, https://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2017/impressionist-modern-art-day-sale-n09711/lot.193.html; Armand Guillaumin, The Corneille Bridge, ca. 1898, oil on canvas, 18 1/8 x 24 in. (46 x 61 cm), sold at Sotheby’s, Paris, “Art Impressionniste et Moderne Day Sale,” March 30, 2021, lot 251, https://www.sothebys.com/en/buy/auction/2021/art-impressionniste-et-moderne-day-sale/le-pont-de-corneille-a-rouen; Armand Guillaumin, Snow in Rouen: The Barges, ca. 1904, oil on canvas, 19 3/4 x 25 1/2 in. (50 x 65 cm), Musée Bonnat-Helleu, Bayonne, RF 1937 78, https://www.musee-orsay.fr/fr/oeuvres/neige-rouen-les-peniches-75130; Armand Guillaumin, The Barges (Les Péniches), 1904, oil on canvas, 21 7/16 x 25 9/16 in. (54.5 x 65 cm), Musée Bonnat-Helleu, Bayonne, RF 1937 87, https://www.musee-orsay.fr/fr/oeuvres/peniches-75139; Armand Guillaumin, Snow Melting in Rouen, ca. 1904, oil on canvas (no dimensions given), Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lyon, https://art.rmngp.fr/fr/library/artworks/armand-guillaumin_neige-fondant-a-rouen_huile-sur-toile; Armand Guillaumin, The Seine Upstream of Rouen, ca. 1904, oil on canvas, 19 1/4 x 25 5/8 in. (49 x 65.2 cm), sold at Sotheby’s, London, “Impressionist and Modern Art Day Sale,” February 4, 2009, lot 175, https://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2009/impressionist-modern-art-day-sale-l09604/lot.175.html; Armand Guillaumin, Banks of the Seine, near Rouen, 1904, oil on canvas, 21 x 26 in. (54.6 x 66.1 cm), sold at Christie’s, New York, “Impressionist and Post-Impressionist Art (Day Sale),” November 9, 1999, lot 245, https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-1609375; Armand Guillaumin, The Barges of Rouen, 1904, oil on canvas, 21 x 31 1/2 in. (53 x 80 cm), private collection, reproduced in Anne Galloyer, ed., Armand Guillaumin (1841–1927): L’Impressioniste Fauve, exh. cat. (Chatou, France: Musée Fournaise, 2003), 46–47. The inscription on the back of Morning, Rouen, reads “Rouen 9bre 1904/le matin,” dating the canvas to November of that year.10The abbreviation “bre” follows the older Latin-based system of month names, where months from September onward retained their original Roman-numerical roots (Septem = 7, Octo = 8, Novem = 9, and so on) with the addition of “bre” following the number. This inscription is discussed in relation to The Barges (Fig. 2) in the forthcoming technical essay by Kress paintings conservation fellow Sophia Boosalis. Guillaumin had recently been in the Netherlands for nine months, from September 1903 until the end of June 1904, marking his first time away from France. It is unclear when exactly he left for Rouen, but in all likelihood it was late summer into at least early winter, based on the known works cited in Christopher Gray, Armand Guillaumin (Chester, CT: Pequot Press, 1972), 58n12. The painting offers a view looking east toward the Côte Sainte-Catherine, or Sainte-Catherine Hill, but avoids its panoramic vista. Guillaumin instead chose to center the river as a reflective surface for his explosive use of color. A solitary figure traverses the riverbank, evoking both industry and leisure—a dual characteristic of modernity. A second version of the composition (Fig. 2), executed at roughly the same time and under similar atmospheric conditions, tightens the composition at the right and thus eliminates the passage of water that, in the Nelson-Atkins picture, accommodates the reflection of colored smoke. It also omits the solitary figure on the riverbank. The comparison reveals Guillaumin working in a loosely serial mode, adjusting elements from one version to the next, but it is the Nelson-Atkins canvas that most fully exploits the chromatic possibilities of the scene. A contemporary postcard of the same location provides a historical reference, offering a nearly identical perspective of the industrial waterfront (Fig. 3). While the postcard faithfully documents the industrial site, Guillaumin’s transformation of this urban setting into a radiant tableau highlights his prioritization of color and movement over mimetic representation.

Most of Guillaumin’s canvases from Rouen feature some activity on the river related to the industrial nature of the port; the city was a hub for trade, textiles, and porcelain production. In the Nelson-Atkins composition, barges moored to bollards lining the bank appear loaded down with goods, while in other Rouen pictures, larger ships appear in the distance beyond the bridges. In nearly all of his works, he includes factories, which have provided much fodder for scholars interested in these as signposts of the artist’s interest in modernity.11See James Rubin, “Factories and Work Sites,” in Impressionism and Modern Landscape: Productivity, Technology, and Urbanization from Manet to Van Gogh (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008), 132–34, 216n43.

Industrial subject matter was not new to Guillaumin. In fact, some of his earliest compositions feature working waterways lined with factories belching smoke along the banks, as seen in a painting the artist made thirty-one years earlier (Fig. 4). While the colors are bold in that 1873 composition, they are still naturalistic and reflect an artist keenly aware of tonal gradation and atmospheric effects. In contrast, the Nelson-Atkins painting embraces a more audacious palette, prioritizing color’s expressive potential over strict naturalism. Yet a newly discovered inscription on its stretcher, noting the weather as “TG” (temps gris, or gray weather) suggests that Guillaumin remained attentive to the nuances of light and climate in his approach.12Sophia Boosalis discovered this inscription using infrared reflectography and deciphered the artist’s shorthand. For more on this, see her accompanying technical entry.

In Morning, Rouen, Guillaumin pushes his chromatic language further than in the 1873 landscape or his other 1904 Rouen scene, adopting more deliberately heightened and non-naturalistic hues—particularly in the saturated tones of the water and sky. While he made a point to note that he captured the painting at eight in the morning and in gray weather conditions, which recalls his Impressionist origins, the exaggerated hues push beyond naturalism, reflecting his evolving vision. Here, the sky shifts from orange, above the distant hills, to blue, punctuated by billowing clouds of violet and yellow factory smoke. The juxtaposition of complementary colors—purple and yellow, blue and orange—creates a vibrating intensity that energizes the composition. For example, the orange-roofed factories in the left background are adjacent to blue buildings. The solitary figure walking along the green path is enlivened by the interplay of their blue and orange attire. The vibrant green path stands in sharp contrast to the artist’s signature in red at lower left. The reflections in the Seine also reveal Guillaumin’s bold approach to color, with crisscrossed orange and blue strokes from the boat masts mingling with the lilac-pink smoke rising from the factories. These elements mirror the movement of water and sky, yet their heightened hues suggest a vision that transcends observed reality, transforming the industrial port into an expressive tableau of modernity.

While critics had acknowledged the artist’s vivid palette since the mid-1880s, it was not until 1891, with a substantial windfall from a lottery win, that the artist was liberated from the financial burden of having to sell works to sustain himself.13Guillaumin scholar Christopher Gray highlights the transformative impact of the artist’s 100,000-franc lottery win, noting that at a time when the annual wage of a skilled worker rarely exceeded 1,750 francs, the interest alone from this sum provided five thousand francs annually, ensuring unparalleled financial security. This pivotal event occurred when Guillaumin was fifty years old, married, and the father of two young children. Gray references Georges Lecomte, who describes how “la bonne fortune d’un lot important à l’un des tirages du Crédit Foncier lui permit de se libérer totalement” (the good fortune of a large lot in one of the Crédit Foncier draws allowed him to free himself completely). See Georges Lecomte, Guillaumin (Paris: Bernheim Jeune, 1926), 23, cited and trans. in Gray, Armand Guillaumin, 45n24. Freed from financial constraints, Guillaumin devoted himself further to his exploration of chromatic intensity, bridging the naturalism of Impressionism and the abstraction of Fauvism. This strong interest in color attracted many of his near contemporaries, including Vincent van Gogh (1853–90).

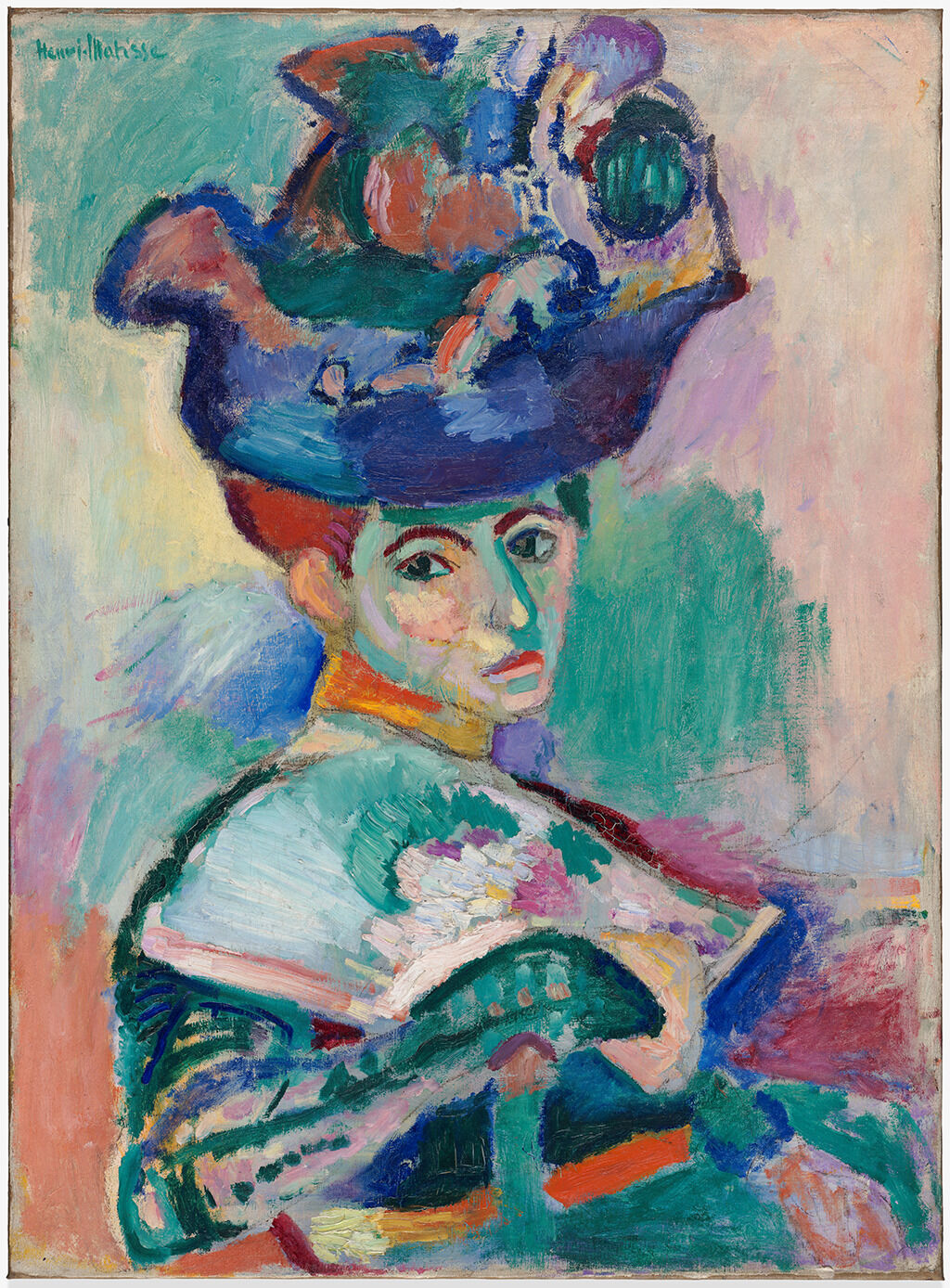

From 1886 to 1888, Guillaumin was the Impressionist with the closest connections to Van Gogh, sharing with him the radical idea of a studio modeled on medieval workshops.14Rainer Budde, ed., Vom Spiel der Farbe: Armand Guillaumin (1841–1927); ein vergessener Impressionist, exh. cat. (Cologne: Wallraf-Richartz-Museum, 1996), 35–36. Van Gogh greatly admired Guillaumin’s use of vibrant, unconventional color, which would influence his own expressive palette.15There are thirty-six letters among the corpus of Van Gogh correspondence that mention Guillaumin; see Leo Jansen, Hans Luijten, and Nienke Bakker, eds., Vincent Van Gogh: The Letters, online edition (Amsterdam and The Hague: Van Gogh Museum and Huygens, 2009), https://vangoghletters.org/vg/search/simple?term=Guillaumin. In a letter to Vincent van Gogh, Theo van Gogh specifically calls out Gullaumin’s use of vigorous color, noting that one finds “the same pink, orange, and violet blue patches, but his touch is vigorous.” See Theo van Gogh, Paris, to Vincent van Gogh, October 22, 1889, published in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 813, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let813/letter.html. All English translations of Van Gogh’s letters are from this publication. See also Vincent’s response to Theo: “What you say about Guillaumin is very true, he has found a true thing and . . . he . . . becomes stronger.” Vincent van Gogh, Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, to Theo van Gogh, October 25, 1889, published in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 815, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let815/letter.html. This admiration also facilitated the Australian artist John Russell (1858–1930)’s acquisition of several Guillaumin works through Theo van Gogh, Vincent’s brother.16See Vincent van Gogh, Arles, to Theo van Gogh, May 1, 1888, published in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 602, http://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let602/letter.html. See also Vincent van Gogh, Arles, to Theo van Gogh, May 4, 1888, published in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 604, http://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let604/letter.html. Guillaumin’s coloristically daring canvases left a lasting impression on Russell, who later became a key influence on Matisse. According to Van Gogh’s correspondence, Russell purchased multiple works by Guillaumin in 1888 and expressed interest in acquiring more, likely sharing them with visitors to his home on Belle-Île, including Matisse during his visit in 1897–98. Matisse’s groundbreaking Woman with a Hat (1905), with its chromatic intensity and roughly applied pigments to the sitter’s face, dress, and background, suggest the influence of Guillaumin (Fig. 5).

Guillaumin’s impact extended beyond Van Gogh and Matisse to the next generation of avant-garde artists. Among them was the young Othon Friesz, who went to work with Guillaumin in the summer of 1901 at Crozant, the picturesque village central to the elder artist’s career. There Friesz encountered Guillaumin’s mastery of pure tones, a revelation that profoundly shaped his approach to color and composition. Friesz later credited Guillaumin with inspiring his shift toward prioritizing bold, unrestrained color over strict naturalism.17See Sophie Monneret, L’impressionnisme et Son Époque: Dictionnaire International Illustré (Paris: Denoël, 1978), 260.

By the time Guillaumin painted Morning, Rouen in 1904, his use of color had reached an intensity that prefigured Fauvism’s radical break with tradition. Guillaumin served as head of the paintings division at the Salon d’Automne in 1905 and 1906, where works by Matisse and other Fauves were displayed. Guillaumin’s vivid industrial landscapes, with their bold hues and modern subjects, embodied the energy and transformation of a world in flux. While rooted in Impressionism, his work foreshadowed Fauvism’s emotional immediacy, positioning him as a pivotal figure in modern art’s evolution. Félix Fénéon’s description of Guillaumin’s paintings as restoring “a robust and placid animality”18“Nous voici devant les Guillaumin. Des ciels immenses: des ciels surchauffés, où se bousculent des nuages dans la bataille des verts, des pourpres, des mauves et des jaunes; d’autres, crépusculaires alors, où de l’horizon se lève l’énorme masse amorphe de nues basses que des vents obliques strient. Sous ces ciels lourdement somptueux, se bossuent, peintes par violents et larges empâtements des campagnes violettes alternant labours et pacages; des arbres se crispent à des pentes fuyant vers des maisons qu’enceignent des potagers, les cours de fermes où se dressent les bras des charrettes. . . . Parmi des arbres et des fleurs, sous des chapeaux de jardin, de mafflées gaillardes lisent, dorment, tassant leurs charnures dans des fauteuils d’osier. Et ce coloriste furieux, ce beau peintre de paysages gorgés de sèves et haletants, a restitué à toutes ses figures humaines une robuste et placide animalité” (Here we are before the Guillaumins. Immense skies: overheated skies, where clouds jostle in the battle of greens, purples, mauves, and yellows; others, then twilight, where from the horizon rises the enormous amorphous mass of low clouds that are streaked by oblique winds. Under these heavily sumptuous skies, violet countrysides are hunched, [their fields] alternate between plowing and pasture, painted in violent and broad impastos; trees cling to slopes leaning toward houses surrounded by vegetable gardens, the farmyards where handcarts stand. . . . Among trees and flowers, under garden hats, lively plump women read [and] sleep, squeezing their flesh into wicker armchairs. And this furious colorist, this beautiful painter of breathtaking, sap-filled landscapes, has restored to all his human figures a robust and placid animality). Original review of the Eighth Impressionist Exhibition by Félix Fénéon, “Les Impressionnistes,” La Vogue, June 13–20, 1886, 261–75, quoted in Berson, The New Painting, 1:443 resonates with the untamed spirit later captured by the term fauve. Though Guillaumin did not fully embrace the avant-garde currents of his time, his innovative approach to color and form bridges the dialogue between naturalism and abstraction, making him an indispensable link between Impressionism and the raw emotional power of Fauvism.

Notes

-

Guillaumin exhibited in six of the eight Impressionist exhibitions, including the inaugural exhibition in 1874.

-

In 1881, Joris Karl Huysmans wrote, “M. Guillaumin est, lui aussi, un coloriste et, qui plus est, un coloriste féroce; au premier abord, ses toiles sont un margouillis de tons bataillants et de contours frustres, un amas de zébrures et de vermillon et de blue de Prusse; écartez-voux et clignez de l’oeil, le tout se remet en place, le plans s’assurent, le tons hurlants s’apaisent, les couleurs hostiles se concilient et l’on reste étonné de la délicatesse imprévue que prennent certaines parties de ces toiles” (Mr. Guillaumin is also a colorist, and what is more, a ferocious colorist; at first glance, his canvases are a jumble of battling tones and rough contours, a mass of zebra stripes and vermilion and Prussian blue; step aside and blink, everything falls back into place, the planes are assured, the screaming tones calm down, the hostile colors reconcile and one remains astonished by the unexpected delicacy that certain parts of these canvases take on). This and subsequent translations, unless otherwise noted, are by the author. Joris Karl Huysmans, “L’Exposition des Indépendants en 1881,” reprinted in Huysmans, L’Art Moderne, 2nd ed. (Paris: P. V. Stock, 1902), 261. For the Fénéon quote “ce coloriste forcené” (this frenzied colorist), see Félix Fénéon, “Les Impressionnistes,” La Vogue, June 13–20, 1886, 261–75, quoted in Ruth Berson, ed., The New Painting: Impressionism, 1874–1886 (San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1996), 1:443.

-

For an exhibition chronicling Rouen as an artistic site of inspiration during the Impressionist era, see Laurent Salomé, ed., A City for Impressionism: Monet, Pissarro, and Gauguin in Rouen, exh. cat. (Milan: Skira, 2010).

-

See several examples at the Tate, including Joseph Mallord William Turner, View of Rouen from the Side of St. Catherine’s Hill, part of the Dieppe, Rouen, and Paris sketchbook, 1821, graphite on paper, 4 5/8 x 4 13/16 in. (11.8 x 12.3 cm), Tate, London, D24509, https://www.tate.org.uk

/art ./artworks /turner -view -of -rouen -from -the -side -of -st -catherines -hill -d24509 -

The line engraving appeared in Turner’s Annual Tour, 1834: Wanderings by the Seine, which was part of a larger project titled River Scenery of Europe and engraved under Charles Heath’s supervision. See the catalogue entry on the website for the Tate, London, at https://www.tate.org.uk

/art (accessed December 16, 2024). For a further discussion of the later publication of The Rivers of France (1837), in which the view of Rouen also appeared, see the Tate’s extended catalogue entry for Nantes, also from Turner’s Annual Tour, at https://www.tate.org.uk/artworks /turner -rouen -from -st -catherines -hill -t04705 /art (accessed December 16, 2024)./artworks /turner -nantes -t04678 -

Turner’s dynamic interplay of light and weather finds echoes in Claude Monet’s series of Rouen Cathedral paintings (1892–94). See, for example, Monet, Rouen Cathedral: The Portal (Sunlight), 1894, oil on canvas, 39 1/4 x 25 7/8 in. (99.7 x 65.7 cm), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 30.95.250, https://www.metmuseum.org

/art . Turner’s elevated view of Rouen also influenced Monet’s General View of Rouen, 25 1/2 x 39 5/16 in. (65 x 100 cm), Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rouen, 995.7.1, https://mbarouen.fr/collection /search /437124 /en ./oeuvres /general -view -of -rouen -

Monet realized more than thirty views of the Rouen Cathedral, in addition to other general views of the city and surrounding countryside, whereas Camille Pissarro created more than twenty compositions in Rouen. See especially the latter’s painting Quai Napoléon, Rouen, 1883, oil on canvas, 21 3/8 x 25 3/8 in. (54.3 x 64.5 cm), Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1978-1-25, https://philamuseum.org

/collection , which is very similar to the Nelson-Atkins composition. For other Pissarro paintings of Rouen, see Joachim Pissarro and Claire Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Critical Catalogue of Paintings (Paris: Wildenstein Institute Publications, 2005), nos. 1218–1237, 3:761–71./object /72114 -

See, for example, Paul Gauguin, Street in Rouen, 1884, oil on canvas, 28 3/4 x 36 1/4 in. (73 x 92 cm), Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, inv. no. 552, https://www.museothyssen.org

/en ; and Alfred Sisley, Sahurs Meadows in Morning Sun, 1894, oil on canvas, 28 3/4 x 36 1/4 in. (73 x 92.1 cm), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1991.277.3, https://www.metmuseum.org/collection /artists /gauguin -paul /street -rouen /art ./collection /search /437683 -

See Armand Guillaumin, The Seine of Rouen, ca. 1898, oil on canvas, 15 1/8 x 18 1/8 in. (38.5 x 46 cm), sold at Christie’s, London, “Impressionist and Modern Art Day Sale,” June 23, 2016, lot 291, https://www.christies.com

/en ; Armand Guillaumin, The Banks of the Seine of Rouen, ca. 1898, oil on canvas, 18 1/8 x 24 in. (46 x 61 cm), sold at Sotheby’s, New York, “Impressionist and Modern Art Day Sale,” May 17, 2017, lot 193, https://www.sothebys.com/lot /lot -6009060 /en ; Armand Guillaumin, The Corneille Bridge, ca. 1898, oil on canvas, 18 1/8 x 24 in. (46 x 61 cm), sold at Sotheby’s, Paris, “Art Impressionniste et Moderne Day Sale,” March 30, 2021, lot 251, https://www.sothebys.com/auctions /ecatalogue /2017 /impressionist -modern -art -day -sale -n09711 /lot.193.html /en ; Armand Guillaumin, Snow in Rouen: The Barges, ca. 1904, oil on canvas, 19 3/4 x 25 1/2 in. (50 x 65 cm), Musée Bonnat-Helleu, Bayonne, RF 1937 78, https://www.musee-orsay.fr/buy /auction /2021 /art -impressionniste -et -moderne -da y-sale /le -pont -de -corneille -a -rouen /fr ; Armand Guillaumin, The Barges (Les Péniches), 1904, oil on canvas, 21 7/16 x 25 9/16 in. (54.5 x 65 cm), Musée Bonnat-Helleu, Bayonne, RF 1937 87, https://www.musee-orsay.fr/oeuvres /neige -rouen -les -peniches -75130 /fr ; Armand Guillaumin, Snow Melting in Rouen, ca. 1904, oil on canvas (no dimensions given), Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lyon, https://art.rmngp.fr/oeuvres /peniches -75139 /fr ; Armand Guillaumin, The Seine Upstream of Rouen, ca. 1904, oil on canvas, 19 1/4 x 25 5/8 in. (49 x 65.2 cm), sold at Sotheby’s, London, “Impressionist and Modern Art Day Sale,” February 4, 2009, lot 175, https://www.sothebys.com/library /artworks /armand -guillaumin _neige -fondant -a -rouen _huile -sur -toile /en ; Armand Guillaumin,/auctions /ecatalogue /2009 /impressionist -modern -art -day -sale -l09604 /lot.175.html Banks of the Seine, near Rouen, 1904, oil on canvas, 21 x 26 in. (54.6 x 66.1 cm), sold at Christie’s, New York, “Impressionist and Post-Impressionist Art (Day Sale),” November 9, 1999, lot 245, https://www.christies.com

/en ; Armand Guillaumin, The Barges of Rouen, 1904, oil on canvas, 21 x 31 1/2 in. (53 x 80 cm), private collection, reproduced in Anne Galloyer, ed., Armand Guillaumin (1841–1927): L’Impressioniste Fauve, exh. cat. (Chatou, France: Musée Fournaise, 2003), 46–47./lot /lot -1609375 -

The abbreviation “bre” follows the older Latin-based system of month names, where months from September onward retained their original Roman-numerical roots (Septem = 7, Octo = 8, Novem = 9, and so on) with the addition of “bre” following the number. This inscription is discussed in relation to The Barges (Fig. 2) in the forthcoming technical essay by Kress paintings conservation fellow Sophia Boosalis. Guillaumin had recently been in the Netherlands for nine months, from September 1903 until the end of June 1904, marking his first time away from France. It is unclear when exactly he left for Rouen, but in all likelihood it was late summer into at least early winter, based on the known works cited in Christopher Gray, Armand Guillaumin (Chester, CT: Pequot Press, 1972), 58n12.

-

See James Rubin, “Factories and Work Sites,” in Impressionism and Modern Landscape: Productivity, Technology, and Urbanization from Manet to Van Gogh (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008), 132–34, 216n43.

-

Sophia Boosalis discovered this inscription using infrared reflectography and deciphered the artist’s shorthand. For more on this, see her accompanying technical entry.

-

Guillaumin scholar Christopher Gray highlights the transformative impact of the artist’s 100,000-franc lottery win, noting that at a time when the annual wage of a skilled worker rarely exceeded 1,750 francs, the interest alone from this sum provided five thousand francs annually, ensuring unparalleled financial security. This pivotal event occurred when Guillaumin was fifty years old, married, and the father of two young children. Gray references Georges Lecomte, who describes how “la bonne fortune d’un lot important à l’un des tirages du Crédit Foncier lui permit de se libérer totalement” (the good fortune of a large lot in one of the Crédit Foncier draws allowed him to free himself completely). See Georges Lecomte, Guillaumin (Paris: Bernheim Jeune, 1926), 23, cited and trans. in Gray, Armand Guillaumin, 45n24.

-

Rainer Budde, ed., Vom Spiel der Farbe: Armand Guillaumin (1841–1927); ein vergessener Impressionist, exh. cat. (Cologne: Wallraf-Richartz-Museum, 1996), 35–36.

-

There are thirty-six letters among the corpus of Van Gogh correspondence that mention Guillaumin; see Leo Jansen, Hans Luijten, and Nienke Bakker, eds., Vincent Van Gogh: The Letters, online edition (Amsterdam and The Hague: Van Gogh Museum and Huygens, 2009), https://vangoghletters.org

/vg . In a letter to Vincent van Gogh, Theo van Gogh specifically calls out Guillaumin’s use of vigorous color, noting that one finds “the same pink, orange, and violet blue patches, but his touch is vigorous.” See Theo van Gogh, Paris, to Vincent van Gogh, October 22, 1889, published in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 813, https://vangoghletters.org/search /simple ?term=Guillaumin /vg . All English translations of Van Gogh’s letters are from this publication. See also Vincent’s response to Theo: “What you say about Guillaumin is very true, he has found a true thing and . . . he . . . becomes stronger.” Vincent van Gogh, Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, to Theo van Gogh, October 25, 1889, published in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 815, https://vangoghletters.org/letters /let813 /letter.html /vg ./letters /let815 /letter.html -

See Vincent van Gogh, Arles, to Theo van Gogh, May 1, 1888, published in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 602, http://vangoghletters.org

/vg . See also Vincent van Gogh, Arles, to Theo van Gogh, May 4, 1888, published in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 604, http://vangoghletters.org/letters /let602 /letter.html /vg ./letters /let604 /letter.html -

See Sophie Monneret, L’impressionnisme et Son Époque: Dictionnaire International Illustré (Paris: Denoël, 1978), 260.

-

“Nous voici devant les Guillaumin. Des ciels immenses: des ciels surchauffés, où se bousculent des nuages dans la bataille des verts, des pourpres, des mauves et des jaunes; d’autres, crépusculaires alors, où de l’horizon se lève l’énorme masse amorphe de nues basses que des vents obliques strient. Sous ces ciels lourdement somptueux, se bossuent, peintes par violents et larges empâtements des campagnes violettes alternant labours et pacages; des arbres se crispent à des pentes fuyant vers des maisons qu’enceignent des potagers, les cours de fermes où se dressent les bras des charrettes. . . . Parmi des arbres et des fleurs, sous des chapeaux de jardin, de mafflées gaillardes lisent, dorment, tassant leurs charnures dans des fauteuils d’osier. Et ce coloriste furieux, ce beau peintre de paysages gorgés de sèves et haletants, a restitué à toutes ses figures humaines une robuste et placide animalité” (Here we are before the Guillaumins. Immense skies: overheated skies, where clouds jostle in the battle of greens, purples, mauves, and yellows; others, then twilight, where from the horizon rises the enormous amorphous mass of low clouds that are streaked by oblique winds. Under these heavily sumptuous skies, violet countrysides are hunched, [their fields] alternate between plowing and pasture, painted in violent and broad impastos; trees cling to slopes leaning toward houses surrounded by vegetable gardens, the farmyards where the handcarts stand. . . . Among trees and flowers, under garden hats, lively plump women read [and] sleep, squeezing their flesh into wicker armchairs. And this furious colorist, this beautiful painter of breathtaking, sap-filled landscapes, has restored to all his human figures a robust and placid animality). Original review of the Eighth Impressionist Exhibition by Félix Fénéon, “Les Impressionnistes,” La Vogue, June 13–20, 1886, 261–75, quoted in Berson, The New Painting, 1:443

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Sophia Boosalis, “Armand Guillaumin, Morning, Rouen, November 1904,” technical entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.623.2088.

MLA:

Boosalis, Sophia. “Armand Guillaumin, Morning, Rouen, November 1904,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.623.2088.

Armand Guillaumin revisited the theme of barge activity along the Seine during his trips to Rouen in 1898 and 1904.1Christopher Gray, Armand Guillaumin (Chester, CT: Pequot Press, 1972), 58. During the latter visit, he painted the same viewpoint along the river twice: Morning, Rouen and The Barges (Les Péniches) (Fig. 2).2See accompanying catalogue essay by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan. Technical study of both landscapes reveals similarities in the canvas support, brushwork, and technique, limiting opportunities to determine more precise execution dates through the artist’s materials.3The author is grateful to Hélène Ferron (curator), Élise Cambreling (curator), and Maïtena Horiot (head of the Research Center) at the Musée Bonnat-Helleu, Bayonne, as well as Dominique Vingtain (director), Maxence Mosseron (head of conservation-restoration department), Nolwenn Giraud (database Pierre Puget administrator), Caroline Martens (photographer) at the Centre Interdisciplinaire de Conservation et de Restauration du Patrimoine (CICRP), for generously sharing their technical images and facilitating the author’s examination of The Barges (1904) on June 23, 2025. Instead, as with many of Guillaumin’s works, the primary means of establishing their chronology lies in the artist’s own inscriptions.4Gray, Armand Guillaumin, 54.

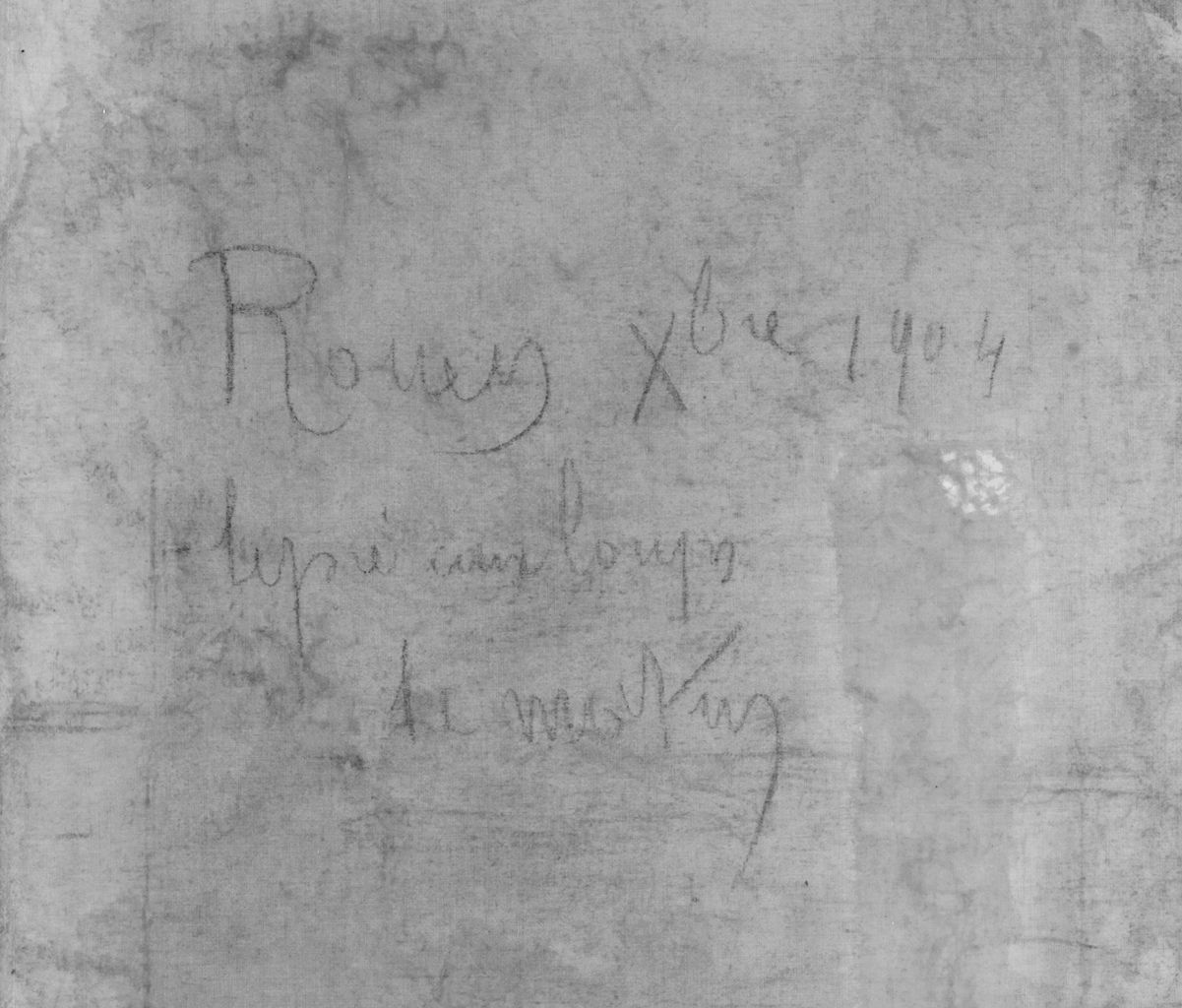

Guillaumin often recorded detailed information on the back of his paintings, noting the date, time, weather, and location to maintain consistent lighting conditions during successive painting sessions.5Jacqueline Derbanne, “Saint-Palais, La Pierrière at Low Tide by Armand Guillaumin,” Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza website, accessed July 13, 2025, https://www.museothyssen.org/en/collection/artists/guillaumin-armand/saint-palais-pierriere-low-tide. On the canvas verso of Morning, Rouen, a cursive inscription in charcoal or chalk confirms that the painting was executed in Rouen in November 1904: “Rouen 9bre 1904 / le matin” (Fig. 6).6See accompanying catalogue entry by Marcereau DeGalan. A secondary notation on the top stretcher, “8hr TG,” indicates that it was painted at 8 a.m. in gray weather, with “TG” serving as shorthand for “temps gris.”7Derbanne, “Saint-Palais, La Pierrière at Low Tide by Armand Guillaumin.” This note reflects Guillaumin’s deliberate efforts to capture the same atmospheric conditions across his early morning sessions. Infrared (IR) photographyinfrared (IR) photography: A form of infrared imaging that employs the part of the spectrum just beyond the red color to which the human eye is sensitive. This wavelength region, typically between 700-1,000 nanometers, is accessible to commonly available digital cameras if they are modified by removal of an IR blocking filter that is required to render images as the eye sees them. The camera is made selective for the infrared by then blocking the visible light. The resulting image is called a reflected infrared digital photograph. Its value as a painting examination tool derives from the tendency for paint to be more transparent at these longer wavelengths, thereby non-invasively revealing pentimenti, inscriptions, underdrawing lines, and early stages in the execution of a work. The technique has been used extensively for more than a half-century and was formerly accomplished with infrared film. of The Barges revealed a similar inscription, previously hidden on its darkened canvas verso: “Rouen Xbre 1904 / le pré aux loups / le matin” (Fig. 7).8The author thanks Meghan Gray, curatorial associate of European paintings and sculpture, for assistance in transcribing and deciphering the middle line of the inscription. This dates the painting to the morning hours of December 1904 and places it at the Quai du Pré aux Loups in Rouen.9Guillaumin employed an older Latin-based system for naming months. This annotation method is discussed in relation to the inscription on Morning, Rouen in the accompanying catalogue entry by Marcereau DeGalan. Guillaumin appears to have completed Morning, Rouen a month before he returned to the same location to paint The Barges.

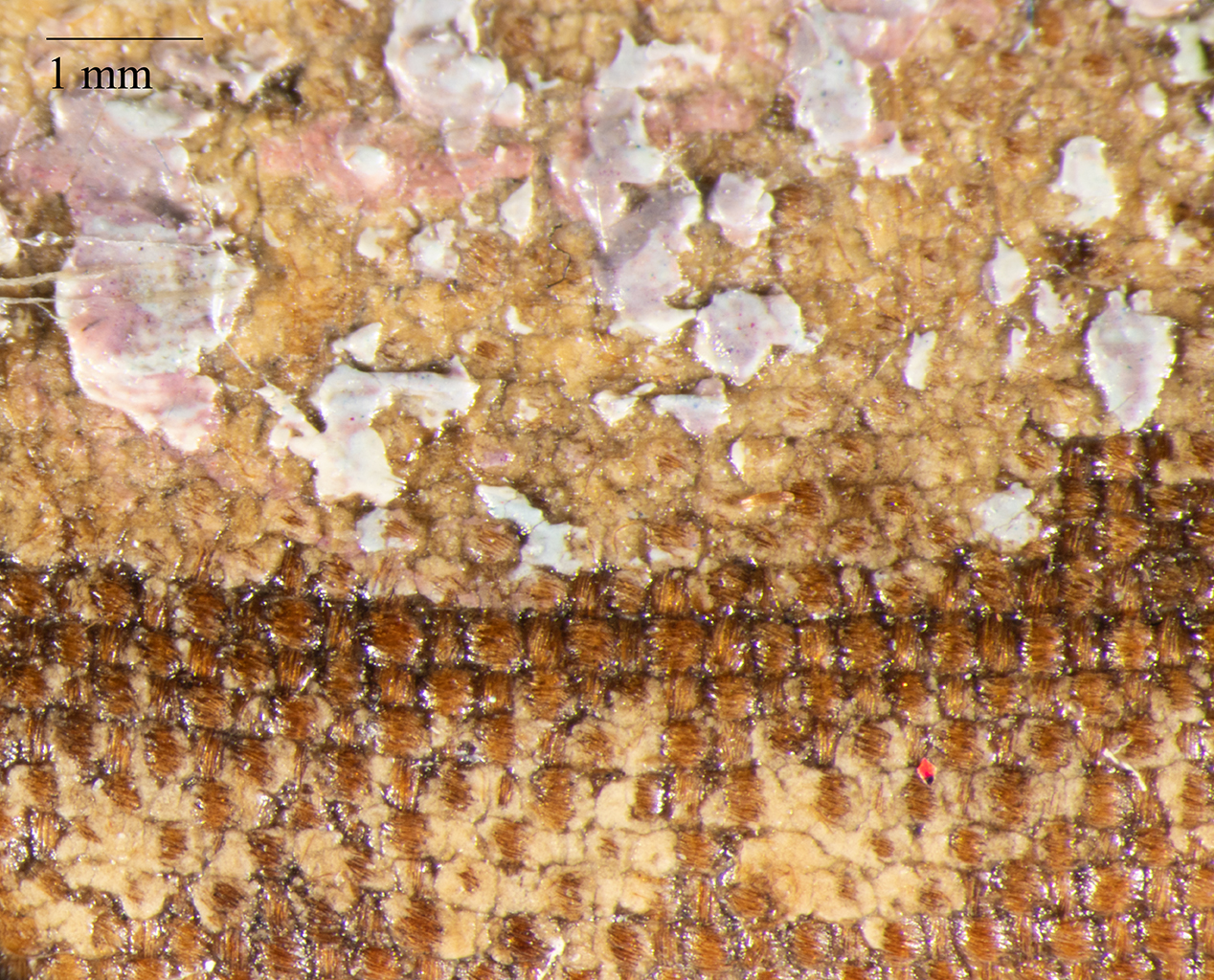

Morning, Rouen was executed on an extremely fine, tightly woven,

plain-weaveplain weave: A basic textile weave in which one weft thread alternates over and under the warp threads. Often this structure consists of one thread in each direction, but threads can be doubled (basket weave) or tripled to create more complex plain weave. Plain weave is sometimes called tabby weave. canvas that is stretched across a five-member stretcherstretcher: A wooden structure to which the painting’s canvas is attached. Unlike strainers, stretchers can be expanded slightly at the joints to improve canvas tension and avoid sagging due to humidity changes or aging. with

a vertical crossbar. Although Guillaumin purchased the stretcher for

The Barges from Tasset et L’Hôte,10There is a stamp on the vertical crossmember of The Barges that reads: “[TASS]ET [&] L’HOTE / 31, Rue Fontaine, PARIS.” A handwritten cursive inscription in pencil along the top stretcher bar, unrelated to the painting, reads: “Août 94. Les dunes de la Couarde Ile de R[?] 8 h matin.” This suggests that Guillaumin had previously brought the stretcher to paint the dunes of La Couarde, Île de Ré, in August 1894. Whether the stretcher is original to The Barges or reused remains unclear; examination of the tacking holes may contribute additional information to its history. However, it is likely that Guillaumin purchased the stretcher from Tasset et L’Hôte sometime between 1887 and 1894. For information about Tasset et L’Hôte, see Pascal Labreuche, “Tasset et Lhote,” Guide Labreuche: Guide historique des fournisseurs de matériel pour artistes à Paris 1790–1960, 2018, https://www.guide-labreuche.com/en/collection/marks-collection/tasset-et-lhote. Guillaumin is known to have used ready-made canvases from this supplier; for instance, The Sea at Saint-Palais (1892; Wallraf-Richartz Museum) and Rock at Baumette Point (1893; Wallraf-Richartz Museum) bear the Bourgeois Ainé stretcher stamp and the Tasset et L’Hôte trademark on the canvas verso. See Caroline von Saint-George and Annegret Volk, “Armand Guillaumin—The Sea at Saint-Palais, Brief Report on Technology and Condition,” in Research Project Painting Techniques of Impressionism and Postimpressionism (Cologne: Wallraf-Richartz-Museum and Fondation Corboud, 2008), https://forschungsprojekt-impressionismus.de/bilder/pdf/7_e.pdf. See also Von Saint-George and Volk, “Armand Guillaumin—Rock at Baumette Point, Brief Report on Technology and Condition,” in Research Project Painting Techniques of Impressionism and Postimpressionism, https://forschungsprojekt

Fig. 8. Photomicrograph of the ground in Morning, Rouen (1904)

Fig. 8. Photomicrograph of the ground in Morning, Rouen (1904)

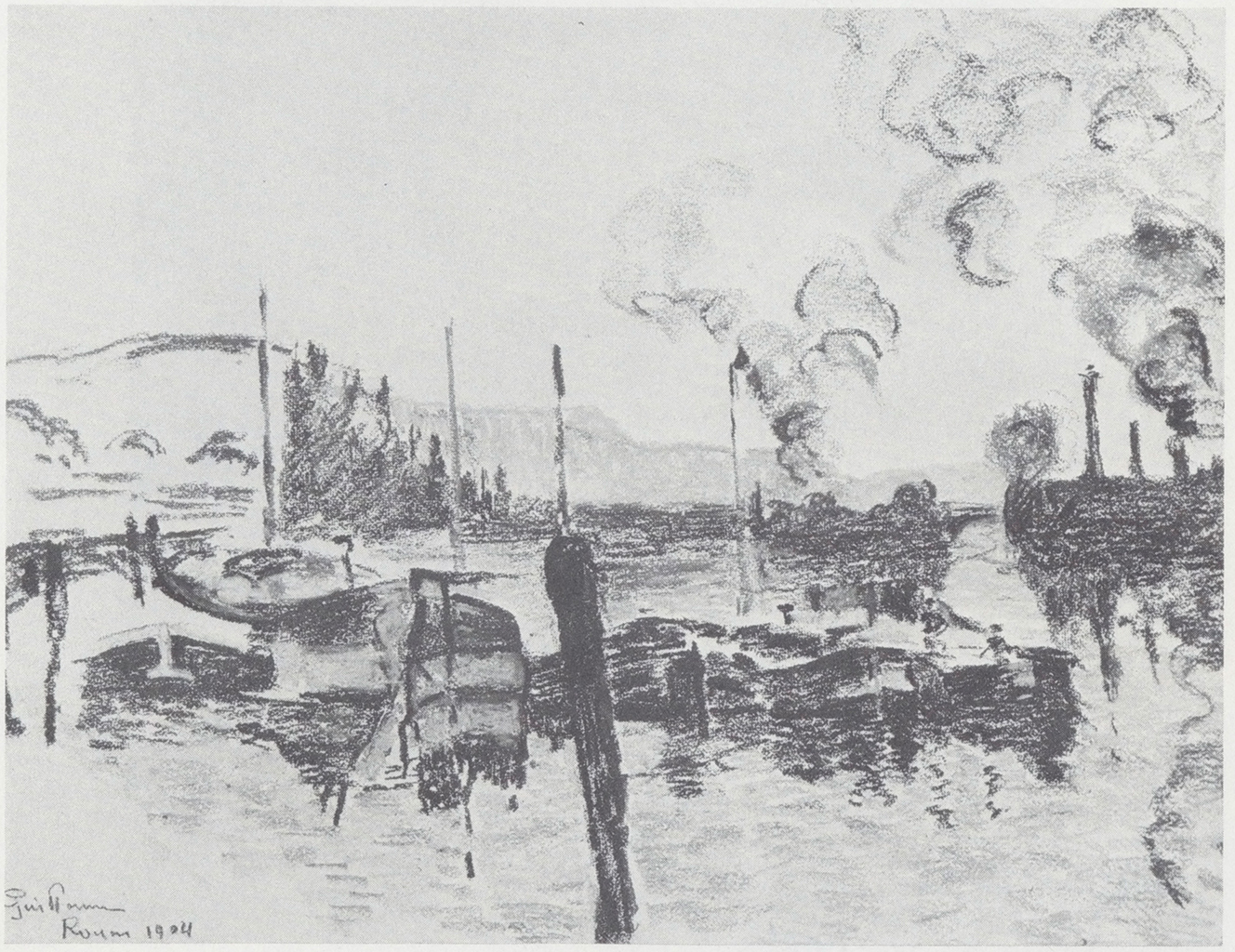

Fig. 9. Armand Guillaumin, Rouen, 1904, pastel on paper, 18 1/8 x 23 13/16 in. (46 x 60.5 cm), unknown location. Photo courtesy of Witt Library, Courtauld Institute of Art, London; Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial (CC-BY-NC).

Fig. 9. Armand Guillaumin, Rouen, 1904, pastel on paper, 18 1/8 x 23 13/16 in. (46 x 60.5 cm), unknown location. Photo courtesy of Witt Library, Courtauld Institute of Art, London; Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial (CC-BY-NC).

Prior to painting en plein airen plein air (adjective: plein-air): French for “outdoors.” The term is used to describe the act of painting quickly outside rather than in a studio., Guillaumin typically worked out his

compositions with preparatory studies in pastel.13The preface of the exhibition catalogue from Guillaumin’s show at Durand-Ruel in 1894 provides information about the artist’s working methods: “Dans les peintures nous retrouverons la même méthode. Elles sont exécutées de la même façon rigoureuse, devant la nature, après les pastels préparatoires” (In his paintings we find the same method. They are executed in the same vigorous manner, before nature, after the preparatory pastels). See Arsène Alexandre, “Preface,” in Exposition de Tableaux et Pastels de Armand Guillaumin (Paris: Galleries Durand-Ruel, January-February 1894), 13: https://archive.org

Extensive wet-over-drywet-over-dry: An oil painting technique that involves layering paint over an already dried layer, resulting in no intermixing of paint or disruption to the lower paint strokes. brushwork confirms that Guillaumin completed Morning, Rouen over multiple painting sessions. Guillaumin appears to have developed some of sky and landscape before focusing on the waterway although he returned to the different areas as the painting progressed. Using a 1/2-inch brush, Guillaumin produced the glowing morning sky with thick paste-like paint and largely diagonal, slightly curving strokes. The resulting surface is lively and full of movement, but this textured brushwork dissipates with the broad strokes of pink paint above the mountains.

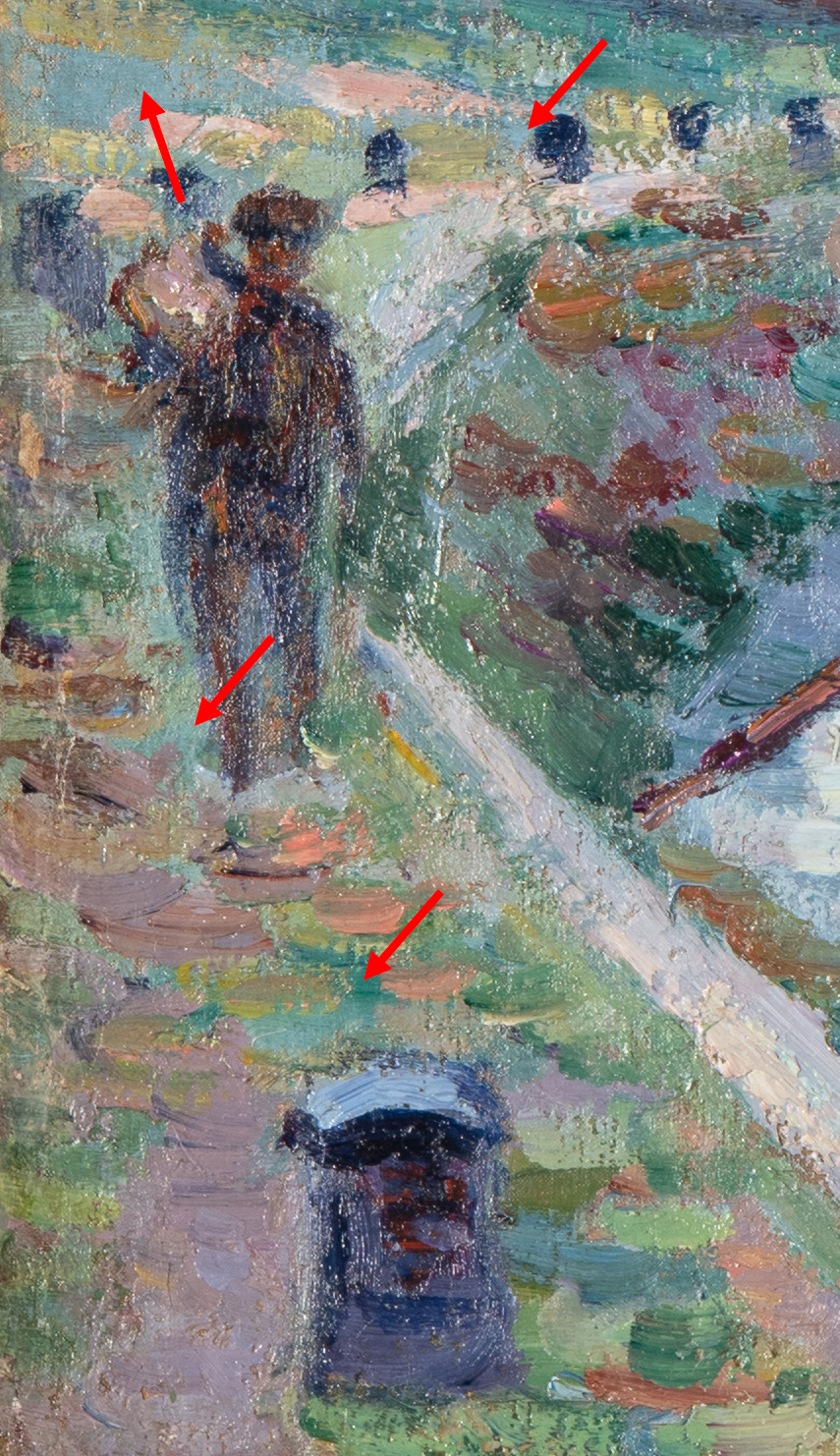

The walkway was underpaintedunderpainting: The first applications of paint that begin to block in color and loosely define the compositional elements. Also called ébauche. with turquoise blue paint that remains visible between the short, horizontal paint strokes of green, purple, and pink applied over multiple sessions (Fig. 10).16The walkway for The Barges was underpainted with pink in the lower half and turquoise blue in the upper half. These subtle variations influenced the sequence in which the green, pink, and purple paint were subsequently applied. A hint of light blue underpainting is also apparent beneath the thicker wet-over-wetwet-over-wet: An oil painting technique which involves drawing a stroke of one color across the wet paint of another color. paint strokes that follow the contours of the mountain range. Guillaumin later returned to the landscape, painting the factories, buildings, and trees over both the mountains and the distant waterway using a combination of wet-over-dry, wet-over-wet, and wet-into-wetwet-into-wet: An oil painting technique which involves blending of colors on the picture surface. techniques (Fig. 11).

Fig. 10. Detail of the shore in Morning, Rouen (1904). Red arrows point to the turquoise blue underpainting below the green and pink dabs of paint.

Fig. 10. Detail of the shore in Morning, Rouen (1904). Red arrows point to the turquoise blue underpainting below the green and pink dabs of paint.

Fig. 11. Photomicrograph of the factories in Morning, Rouen (1904), showing a mixture of wet-into-wet, wet-over-wet, and wet-over-dry paint application

Fig. 11. Photomicrograph of the factories in Morning, Rouen (1904), showing a mixture of wet-into-wet, wet-over-wet, and wet-over-dry paint application

The waterway was developed through successive applications of horizontal brushstrokes of white, blue, and purple, beginning at the rear and progressing toward the foreground.17Morning, Rouen is characterized by horizontal strokes of light blue hues across the foreground of the waterway, whereas The Barges employs vertical strokes of yellow, blue, and seafoam green. Guillaumin left the barges and their shadows in reserve. In the final stage, paint strokes that surround the boats are thick and dryly painted, creating a tactile effect that is markedly different from the smooth paint of the central boats and their reflections.

Fig. 12. Photomicrograph of a boat in Morning, Rouen (1904), showing a mixture of wet-into-wet, wet-over-wet, and partially blended brushstrokes

Fig. 12. Photomicrograph of a boat in Morning, Rouen (1904), showing a mixture of wet-into-wet, wet-over-wet, and partially blended brushstrokes

Fig. 13. Photomicrograph the shadow of the barges in Morning, Rouen (1904)

Fig. 13. Photomicrograph the shadow of the barges in Morning, Rouen (1904)

The boats were initially blocked in with a reddish-brown underpainting,

slightly extending over the surrounding waterway. Thicker paint strokes

were then applied wet-over-wet and wet-into-wet to articulate details,

highlights, and shadows in the boats. While some paint colors

intermingled on the canvas during application, Guillaumin also deposited

partially mixed paint on his brush, incorporating a wide spectrum of

hues within individual strokes in the boats and later in the mooring

posts (Fig. 12).18The same technique has been observed in Armand Guillaumin’s Self-Portrait with Palette (1878; Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam). See Maite van Dijk, Nina Reid, and Sara Tas, “Armand Guillaumin, Self-Portrait with Palette, 1878 and Portrait of a Young Woman, 1886,” catalogue entry in Contemporaries of Van Gogh 1: Works Collected by Theo and Vincent, ed. Joost van der Hoeven (Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum, 2023): https://doi.org

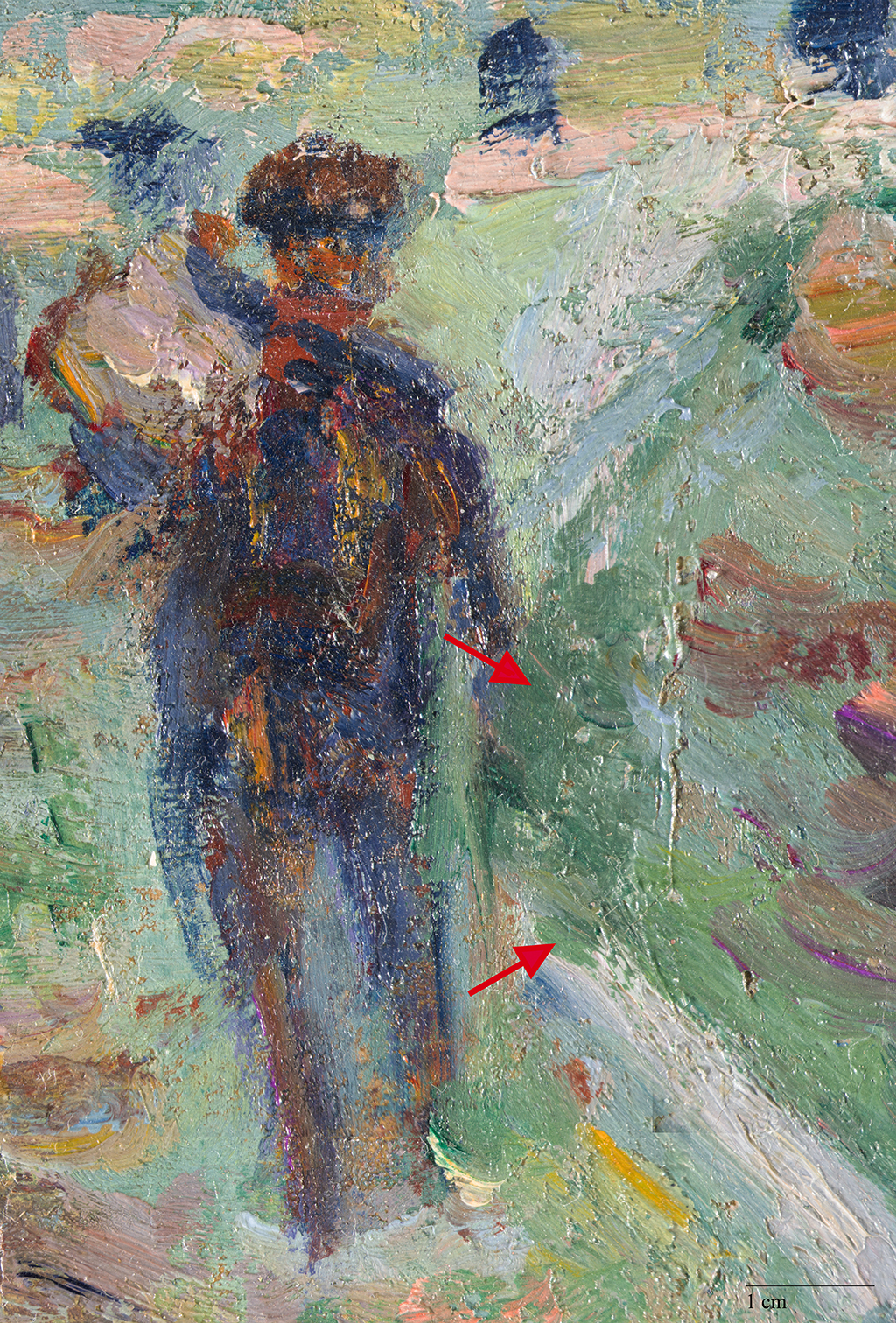

Fig. 14. Photomicrograph of the shore in Morning, Rouen (1904). Red arrows point to the dabs of green paint that cover part of the diagonal shoreline and the standing figure.

Fig. 14. Photomicrograph of the shore in Morning, Rouen (1904). Red arrows point to the dabs of green paint that cover part of the diagonal shoreline and the standing figure.

Fig. 15. Detail of mooring posts on the shore of The Barges (Les Péniches), 1904, Musée Bonnat-Helleu. Red arrows point to the application of green paint around and partially covering the mooring posts. Photo courtesy of Caroline Martens, CICRP.

Fig. 15. Detail of mooring posts on the shore of The Barges (Les Péniches), 1904, Musée Bonnat-Helleu. Red arrows point to the application of green paint around and partially covering the mooring posts. Photo courtesy of Caroline Martens, CICRP.

Technical examination of Morning, Rouen and The Barges revealed subtle differences in their execution. With no apparent reliance on an underdrawingunderdrawing: A drawn or painted sketch beneath the paint layer. The underdrawing can be made from dry materials, such as graphite or charcoal, or wet materials, such as ink or paint., Guillaumin appears to have confidently painted the Nelson-Atkins work with only one compositional change. He made an adjustment to the left walkway, adding dabs of fluid green paint on top of the diagonal shoreline to create a wider angle along its curve (Fig. 14). One month later, Guillaumin appears to have relied on a few painted lines to position the factory and shoreline of The Barges.20Infrared reflectogram (IR) of The Barges taken by Caroline Martens at Centre Interdisciplinaire de Conservation et de Restauration du Patrimoine (CICRP). See copy in the NAMA conservation file, 2021.20. There is an immediacy to the loose brushwork of this painting, which is characterized by extensive wet-over-wet and wet-into-wet blending. Additionally, a number of compositional changes are evident. Guillaumin reduced the width of several mooring posts in the foreground through loosely applying green paint around their edges (Fig. 15). He also broke up the angle of the shadows cast by a group of mooring posts with additions of light blue dabs of paint to reinstate the presence of water (Fig. 16). Drying cracksdrying cracks: Also known as traction cracks, these are formed as the paint dries. They are usually the result of a "lean" paint with a small percentage of oil drying faster than an underlying "fat" paint layer with a higher percentage of oil. The quick drying of the top layer causes the paint layer to shrink and crack. in the far-right boat reveal slivers of light blue and yellow paint, suggesting that Guillaumin added this element at a later stage of painting (Fig. 17). This adjustment may have been a response to the shifting activity on the waterway while painting en plein air. Without the dated inscriptions on the versos, the presence of artist changes in The Barges could have pointed to an alternate sequence of execution between the two paintings.

Fig. 16. Detail of the mooring posts in The Barges (Les Péniches), 1904, Musée Bonnat-Helleu. Red arrows point to dabs of light-blue paint on top of the dark bluish-purple paint layers. Photo courtesy of Caroline Martens, CICRP.

Fig. 16. Detail of the mooring posts in The Barges (Les Péniches), 1904, Musée Bonnat-Helleu. Red arrows point to dabs of light-blue paint on top of the dark bluish-purple paint layers. Photo courtesy of Caroline Martens, CICRP.

Fig. 17. Detail of the far-right boat in The Barges (Les Péniches), 1904, Musée Bonnat-Helleu, showing drying cracks in the upper paint layers. Photo courtesy of Caroline Martens, CICRP.

Fig. 17. Detail of the far-right boat in The Barges (Les Péniches), 1904, Musée Bonnat-Helleu, showing drying cracks in the upper paint layers. Photo courtesy of Caroline Martens, CICRP.

Morning, Rouen underwent at least one conservation treatment prior to

its acquisition by the Nelson-Atkins Museum in 2021. Although a canvas

insert was applied to reinforce a major tear at the top turnover edgeturnover edge: The point at which the canvas begins to wrap around the stretcher, at the junction between the picture plane and tacking margin. See also foldover edge.,

several tears along the turnover edges and tacking marginstacking margins: The outer edges of canvas that wrap around and are attached to the stretcher or strainer with tacks or staples. See also tacking edge. were

unaddressed. The synthetic varnish and yellowed varnish residues within

the interstices of impastoimpasto: A thick application of paint, often creating texture such as peaks and ridges. impart a yellow tonality overall.21Guillaumin’s preference for an unvarnished paint surface was made clear on the verso of Moret sur Loing (1902; private collection) where he wrote “ne pas venir” (do not varnish). See Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “Armand Guillaumin, Moret-sur-Loing, Evening Effect, No. 2, ca. 1902,” catalogue entry in this catalogue, https://doi.org

Notes

-

Christopher Gray, Armand Guillaumin (Chester, CT: Pequot Press, 1972), 58.

-

See accompanying catalogue essay by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan.

-

The author is grateful to Hélène Ferron (curator), Élise Cambreling (curator), and Maïtena Horiot (head of the Research Center) at the Musée Bonnat-Helleu, Bayonne, as well as Dominique Vingtain (director), Maxence Mosseron (head of conservation-restoration department), Nolwenn Giraud (database Pierre Puget administrator), Caroline Martens (photographer) at the Centre Interdisciplinaire de Conservation et de Restauration du Patrimoine (CICRP), for generously sharing their technical images and facilitating the author’s examination of The Barges (1904) on June 23, 2025.

-

Gray, Armand Guillaumin, 54.

-

Jacqueline Derbanne, “Saint-Palais, La Pierrière at Low Tide by Armand Guillaumin,” Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza website, accessed July 13, 2025, https://www.museothyssen.org

/en ./collection /artists /guillaumin -armand /saint -palais -pierriere -low -tide -

See accompanying catalogue entry by Marcereau DeGalan.

-

Derbanne, “Saint-Palais, La Pierrière at Low Tide by Armand Guillaumin.”

-

The author thanks Meghan Gray, curatorial associate of European paintings and sculpture, for assistance in transcribing and deciphering the middle line of the inscription.

-

Guillaumin employed an older Latin-based system for naming months. This annotation method is discussed in relation to the inscription on Morning, Rouen in the accompanying catalogue entry by Marcereau DeGalan.

-

There is a stamp on the vertical crossmember of The Barges that reads: “[TASS]ET [&] L’HOTE / 31, Rue Fontaine, PARIS.” A handwritten cursive inscription in pencil along the top stretcher bar, unrelated to the painting, reads: “Août 94. Les dunes de la Couarde Ile de R[?] 8 h matin.” This suggests that Guillaumin had previously brought the stretcher to paint the dunes of La Couarde, Île de Ré, in August 1894. Whether the stretcher is original to The Barges or reused remains unclear; examination of the tacking holes may contribute additional information to its history. However, it is likely that Guillaumin purchased the stretcher from Tasset et L’Hôte sometime between 1887 and 1894. For information about Tasset et L’Hôte, see Pascal Labreuche, “Tasset et Lhote,” Guide Labreuche: Guide historique des fournisseurs de matériel pour artistes à Paris 1790–1960, 2018, https://www.guide-labreuche.com

/en . Guillaumin is known to have used ready-made canvases from this supplier; for instance, The Sea at Saint-Palais (1892; Wallraf-Richartz Museum) and Rock at Baumette Point (1893; Wallraf-Richartz Museum) bear the Bourgeois Ainé stretcher stamp and the Tasset et L’Hôte trademark on the canvas verso. See Caroline von Saint-George and Annegret Volk, “Armand Guillaumin—The Sea at Saint-Palais, Brief Report on Technology and Condition,” in Research Project Painting Techniques of Impressionism and Postimpressionism, (Cologne: Wallraf-Richartz-Museum and Fondation Corboud, 2008), https://forschungsprojekt/collection /marks-collection /tasset -et -lhote -impressionismus . See also Von Saint-George and Volk, “Armand Guillaumin—Rock at Baumette Point, Brief Report on Technology and Condition,” in Research Project Painting Techniques of Impressionism and Postimpressionism, https://forschungsprojekt.de /bilder /pdf /7 _e .pdf -impressionismus ..de /bilder /pdf /8 _e .pdf -

David Bomford, Jo Kirby, John Leighton, and Ashok Roy, Art in the Making: Impressionism (London: Yale University Press, 1991), 46.

-

The Barges was also executed on a commercially primed, extremely fine, plain-weave canvas with a lean off-white ground.

-

The preface of the exhibition catalogue from Guillaumin’s show at Durand-Ruel in 1894 provides information about the artist’s working methods: “Dans les peintures nous retrouverons la même méthode. Elles sont exécutées de la même façon rigoureuse, devant la nature, après les pastels préparatoires” (In his paintings we find the same method. They are executed in the same vigorous manner, before nature, after the preparatory pastels). See Arsène Alexandre, “Preface,” in Exposition de Tableaux et Pastels de Armand Guillaumin (Paris: Galleries Durand-Ruel, January-February 1894), 13: https://archive.org

/details . Translation from Gray, Armand Guillaumin, 51–52./exposition de tableaux et pastels dearmand guillauminnd 553 .g9a1p1894 -

A search through the Courtauld Institute of Art’s digitized Witt Photographic Collection yielded a black-and-white photograph of Rouen cut from the auction catalogue of the Hôtel Drouot in Paris, dated December 3, 1973; see Importants Tableaux Modernes (Paris: Hôtel Drouot, 1973), no. 46. See also the Witt Library, Courtauld Institute of Art, London, box and folder “Courtauld_034066_Witt_056917 / Guillaumin, J-B Armand / Drawings & Graphic Work Landscapes. Horzional & Subject Not To Top,” https://photocollections.courtauld.ac.uk/sec-menu/search/detail/3dc49972-de02-1b61-c8dd-1c60afde223b/media/65ae94bb-39bf-0a88-1ac8-1ac93cfe2923.

-

No underdrawing was identified beneath Morning, Rouen through infrared photography or stereomicroscopic examination. Minimal underdrawings have been observed in earlier works by Guillaumin; see Diana M. Jaskierny, “Armand Guillaumin, Landscape, Ivry-sur-Seine, ca. 1874,” technical entry in this catalogue, https://doi.org

/10.37764 . However, Guillaumin did not consistently employ underdrawings and sometimes painted directly onto the canvas, as seen in Quay in the Snow (ca. 1873; Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, MA) and Landscape, Île-de-France (ca. 1878; Clark Art Institute). See Von Saint-George and Volk, “Armand Guillaumin—Rock at Baumette Point, Brief Report on Technology and Condition,” and “Armand Guillaumin—The Sea at Saint-Palais, Brief Report on Technology and Condition”; see also Sarah Lees, ed., Nineteenth-Century European Paintings at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute (Williamstown: Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, 2012), 1:394–99./78973 .5 .621 .2088 -

The walkway for The Barges was underpainted with pink in the lower half and turquoise blue in the upper half. These subtle variations influenced the sequence in which the green, pink, and purple paint were subsequently applied.

-

Morning, Rouen is characterized by horizontal strokes of light blue hues across the foreground of the waterway, whereas The Barges employs vertical strokes of yellow, blue, and seafoam green.

-

The same technique has been observed in Armand Guillaumin’s Self-Portrait with Palette (1878; Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam). See Maite van Dijk, Nina Reid, and Sara Tas, “Armand Guillaumin, Self-Portrait with Palette, 1878 and Portrait of a Young Woman, 1886,” catalogue entry in Contemporaries of Van Gogh 1: Works Collected by Theo and Vincent, ed. Joost van der Hoeven (Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum, 2023): https://doi.org

/10.58802 ./YWAB3388 -

Unlike Morning, Rouen, thicker dabs of reddish paint were used to represent the shadow of a single boat mast in The Barges.

-

Infrared reflectogram (IR) of The Barges taken by Caroline Martens at Centre Interdisciplinaire de Conservation et de Restauration du Patrimoine (CICRP). See copy in the NAMA conservation file, 2021.20.

-

Guillaumin’s preference for an unvarnished paint surface was made clear on the verso of Moret sur Loing (1902; private collection) where he wrote “ne pas venir” (do not varnish). See Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “Armand Guillaumin, Moret-sur-Loing, Evening Effect, No. 2, ca. 1902,” catalogue entry in this catalogue, https://doi.org

/10.37764 ./78973.5.622.5407

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Armand Guillaumin, Morning, Rouen, November 1904,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.623.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Armand Guillaumin, Morning, Rouen, November 1904,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.623.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Armand Guillaumin, Morning, Rouen, November 1904,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.623.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Armand Guillaumin, Morning, Rouen, November 1904,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.623.4033.

Possibly with Galerie Bernheim Jeune, Paris, by 1906–possibly 1924 [1];

Acquired by a private collector, France, around 1920 [2];

By descent to his son, at least 2019–20;

With Leighton Fine Art, Marlow, London, by March–August 5, 2021;

Purchased from Leighton Fine Art by the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 2021.

Notes

[1] It is possible that Morning, Rouen was exhibited at the Exposition Guillaumin, held at Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, Paris, April 6–21, 1906, as one of seven options: no. 8, Rouen, 1904; no. 11, Rouen; no. 13, Quai à Rouen; no. 16, Rouen; no. 17, La Seine avant Rouen (fumées); no. 18, Quai de Rouen; or no. 19, Rouen. The catalogue does not reproduce the works nor list sizes, and contemporary criticism has not produced enough details to identify individual canvases.

In 1924, Bernheim-Jeune was listed as an owner of two Guillaumin paintings, both entitled “Vue de Rouen,” with one matching the Nelson-Atkins dimensions: 54 x 65 cm. See Édouard Des Courières, Armand Guillaumin (Paris: Henri Floury, 1924), 165. This painting might also be Banks of the Seine, near Rouen, 1904, oil on canvas, 21 x 26 in. (54.6 x 66.1 cm), sold at Christie’s, New York, “Impressionist and Post-Impressionist Art (Day Sale),” November 9, 1999, lot 245 (see below in Related Works).

[2] The painting appeared for sale twice by this private collector, but went unsold both times: Art Impressionniste et Moderne, Art Contemporain Cornette de Saint Cyr, Maison de Ventes S.A.S., Paris, June 27, 2019, lot 53; and again at Art Impressionniste et Moderne, Cornette de Saint Cyr, Maison de Ventes S.A.S., Paris, July 1, 2020, lot 78, as Rouen le matin, septembre 1904. The provenance in the sales catalogue says, “Acquise vers 1920 par le père du propriétaire actuel. Par descendance” (Acquired around 1920 by the father of the current owner. By descent).

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Armand Guillaumin, Morning, Rouen, November 1904,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.623.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Armand Guillaumin, Morning, Rouen, November 1904,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.623.4033.

Armand Guillaumin, The Seine at Rouen, ca. 1898, oil on canvas, 15 1/8 x 18 1/8 in. (38.5 x 46 cm), sold at Impressionist and Modern Art Day Sale, Christie’s, London, June 23, 2016, lot 291.

Armand Guillaumin, Rouen, 1904, pastel on paper, 18 1/8 x 23 13/16 in. (46 x 60.5 cm), unknown location; reproduced in Importants Tableaux Modernes (Paris: Hôtel Drouot, December 3, 1973), no. 46.

Armand Guillaumin, The Barges (Les Péniches), 1904, oil on canvas, 21 7/16 x 25 9/16 in. (54.5 x 65 cm), Musée Bonnat-Helleu, Bayonne, RF 1937 87.

Armand Guillaumin, Snow in Rouen: The Barges, ca. 1904, oil on canvas, 19 3/4 x 25 1/2 in. (50 x 65 cm), Musée Bonnat-Helleu, Bayonne, RF 1937 78.

Armand Guillaumin, The Barges of Rouen, 1904, oil on canvas, 21 x 31 1/2 in. (53 x 80 cm), private collection; reproduced in Armand Guillaumin (1841–1927): L’Impressioniste Fauve, exh. cat (Chatou, France: Musée Fournaise, 2003), no. 53, pp. 46–47.

Armand Guillaumin, Banks of the Seine, near Rouen, 1904, oil on canvas, 21 x 26 in. (54.6 x 66.1 cm), sold at Impressionist and Post-Impressionist Art (Day Sale), Christie’s, New York, November 9, 1999, lot 245.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Armand Guillaumin, Morning, Rouen, November 1904,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.623.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Armand Guillaumin, Morning, Rouen, November 1904,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.623.4033.

Possibly Exposition Guillaumin, MM. Bernheim-Jeune, Paris, April 6–21, 1906, as one of seven options: no. 8, Rouen, 1904; no. 11, Rouen; no. 13, Quai à Rouen; no. 16, Rouen; no. 17, La Seine avant Rouen (fumées); no. 18, Quai de Rouen; or no. 19. Rouen.

Possibly Ausstellung von werken Französischer Künstler der Gegenwart, Alten Schloss, Strassburg, March 2–April 2, 1907, no. 128, as Ansicht von Rouen.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Armand Guillaumin, Morning, Rouen, November 1904,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.623.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Armand Guillaumin, Morning, Rouen, November 1904,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.623.4033.

Possibly Exposition Guillaumin, exh. cat. (Paris: Bernheim-Jeune, April 6–21, 1906), unpaginated.

Possibly Georges Bal, “Exposition Guillaumin,” New York Herald (April 10, 1906): 5, as Vues de Rouen.

Possibly Katalog der Ausstellung von werken Französischer Künstler der Gegenwart, exh. cat. (Strassburg: Fischbach, 1907), 12, as Ansicht von Rouen.

Possibly Édouard Des Courières, Armand Guillaumin (Paris: Henri Floury, 1924), 165, as Vue de Rouen, and with dimensions of 54 x 65 cm.

Art Impressionniste et Moderne, Art Contemporain (Paris: Cornette de Saint Cyr, June 27, 2019), 20–21, (repro.), as Rouen le Matin.

Art Impressionniste et Moderne (Paris: Cornette de Saint Cyr, July 1, 2020), 74–75, (repro.), as Rouen le Matin, septembre 1904.

“Nelson-Atkins donor gifts enhance European collection,” ArtDaily (December 15, 2021): https://artdaily.cc/news/142058/Nelson-Atkins-donor-gifts-enhance-European-collection-#.YbomdbpMGUk.

“Nelson-Atkins welcomes French Impressionist works,” Live Auctioneers: Auction Central News (December 22, 2021): https://www.liveauctioneers.com/news/top-news/nelson-atkins-welcomes-french-impressionist-works/.

Julián Zugazagoitia, Director’s Highlights: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Celebrating 90 Years, ed. Kaitlyn Bunch (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), 223, 250, (repro.).