Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Meghan L. Gray, “Edgar Degas, Junior Milliners, 1882,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.618.5407.

MLA:

Gray, Meghan L. “Edgar Degas, Junior Milliners, 1882,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.618.5407.

A hat is quite a poem; it’s a symphony, it’s a melody, it’s always a masterpiece to create.1Maurice Praslières, “Un Grande Modiste au XXe Siècle,” Les Modes, no. 46 (October 1904): 20. “Mais c’est tout un poème qu’un chapeau; c’est une symphonie, c’est une mélodie, c’est toujours un chef-d’oeuvre à créer.” All translations by Meghan L. Gray, unless otherwise noted. Written to advertise the modiste Alphonsine’s new headquarters, the article emphasizes all her best qualities, including her ability to speak six languages and her extensive travels, and pays particular attention to her appreciation of great eighteenth-century artists like Jean Marc Nattier (1685–1766), François Boucher (1703–70), and Antoine Watteau (1684–1721). The author likens Alphonsine’s expertise to the highest echelons of the artistic hierarchy.

In Junior Milliners, Degas shows his affinity for the milliners of Paris, the hat-making capital of the world.2Of nearly one thousand millinery shops in Paris in 1870, about 86 percent were women-owned businesses. Francoise Tétart-Vittu, “The Milliners of Paris, 1870–1910,” in Simon Kelly and Esther Bell, Degas, Impressionism, and the Paris Millinery Trade, exh. cat. (San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 2017), 52. Two women are absorbed in their work, putting the finishing touches on exquisite chapeaus. With her eyes cast down and to the left, the woman in navy blue studies the placement of a frilly blue ostrich feather, perhaps sewing it into place. Her colleague, dressed in olive green, watches her progress. Degas depicts the interiority of the women as they elevate plain orbs of beige straw—like the one perched on a slender hat stand in the middle of the table—to confections of blue and yellow silk and feathers. Degas equates the milliners’ craft to that of an artist; the women stand statuesque, absorbed in creating beautiful objects for consumption.

Degas composes a harmonious arrangement of negative and positive space, repeating the shapes of the almost-hovering hats over a green-striped wallpaper background and the dark columns of the women’s bodies. The picture is divided in half vertically, with the hat on the champignon (hat stand) sitting just to the right of center. Horizontally, the top half of the pastel is the most active. In the uppermost register, roughly the top 25 percent of the composition, the crowns of the women’s heads touch the very edge of the paper. In the next register down are the hats. Seen together, the hats and heads of the two assistants lead the viewer’s eye from left to right in a zigzag pattern. Especially when the pastel is viewed in its frame, the women seem squeezed within this creative world. Degas may have designed the passepartout frame, with its fluted top edge and wide frieze painted in cream-colored gesso. He probably intended the frieze to continue the visual line of the picture planepicture plane: The two-dimensional surface where the artist applies paint., allowing the composition more room to breathe; the gilded spacers may have been added later.3For more on the frame, see the technical entry by Rachel Freeman accompanying this present essay. A photograph of a room of Loan Exhibition of Masterpieces by Old and Modern Painters, M. Knoedler and Co., New York, in 1915, seems to show the pastel framed without the spacers; reproduced in Frances Weitzenhoffer, The Havemeyers: Impressionism Comes to America (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1986), 224.

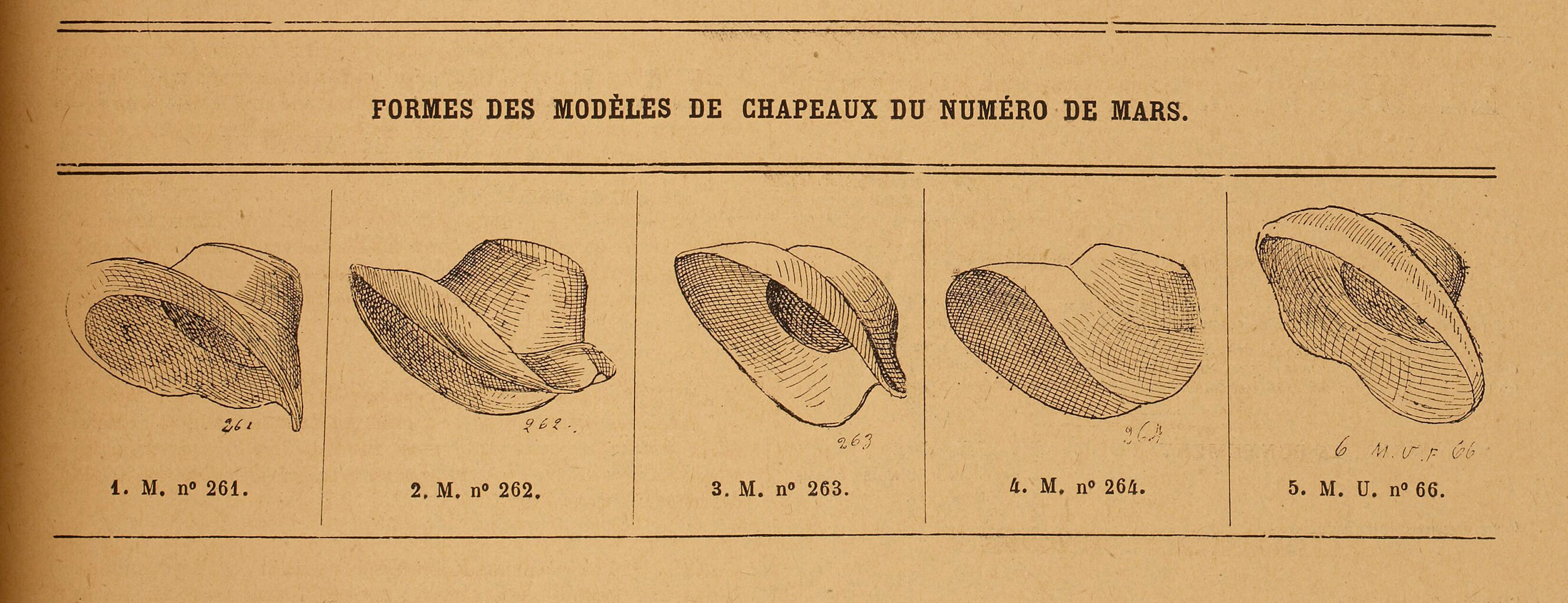

Fig. 1. “Formes des Modèles de Chapeaux du Numéro de Mars” by Madame Heitz-Boyer, from La Modiste Universelle, March 1882, lithograph on paper, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, département Réserve des livres rares, FOL-V-832

Fig. 1. “Formes des Modèles de Chapeaux du Numéro de Mars” by Madame Heitz-Boyer, from La Modiste Universelle, March 1882, lithograph on paper, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, département Réserve des livres rares, FOL-V-832

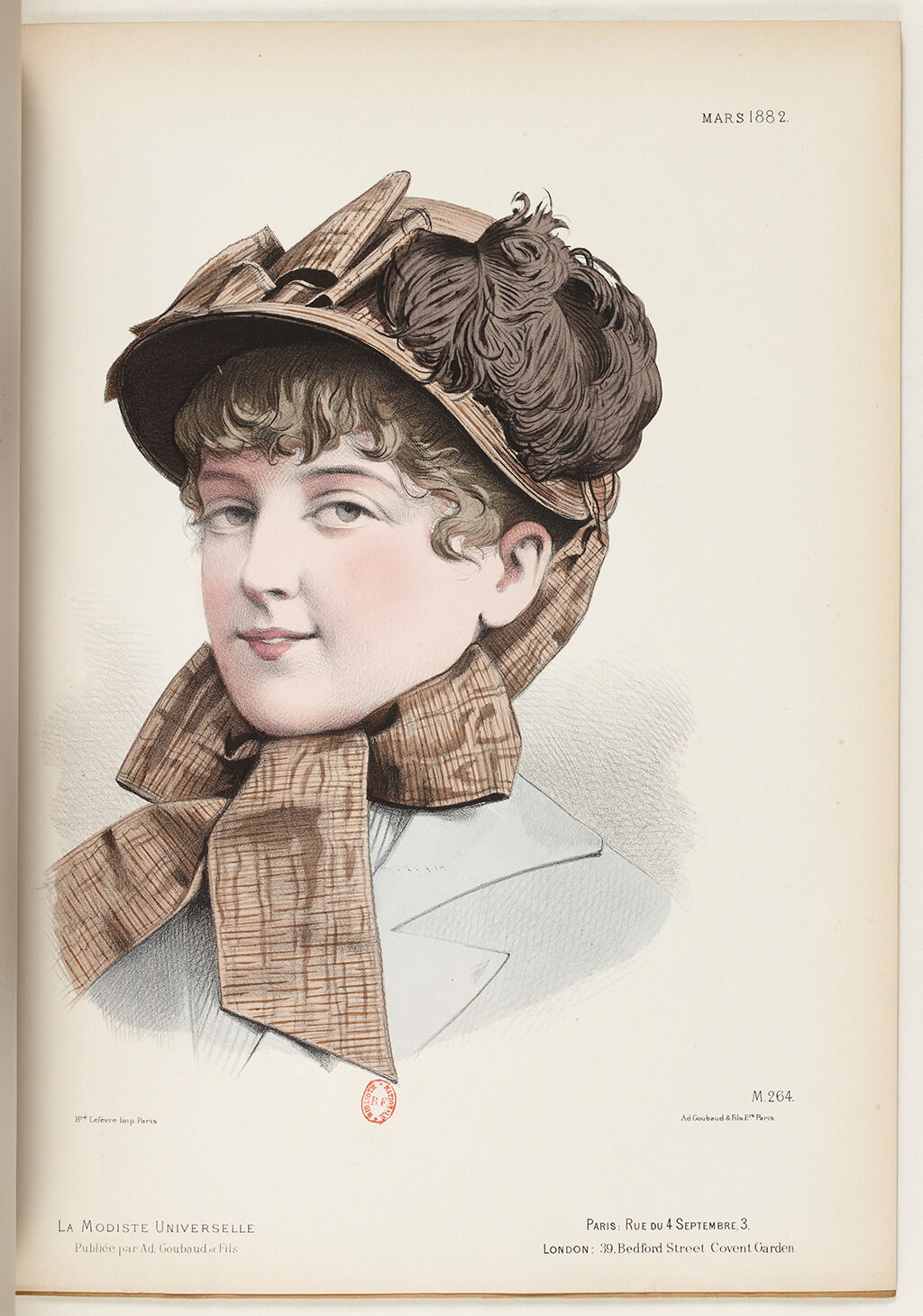

Fig. 2. “Bonnet fermière” by Madame Heitz-Boyer, from La Modiste Universelle, March 1882, lithograph on paper, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, département Réserve des livres rares, FOL-V-832

Fig. 2. “Bonnet fermière” by Madame Heitz-Boyer, from La Modiste Universelle, March 1882, lithograph on paper, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, département Réserve des livres rares, FOL-V-832

Millinery subjects especially appealed to the artist, given the opportunity to represent women in a realistic moment and capture a slice of modern life.10Degas and his colleagues were influenced by the writings of Charles Baudelaire, whose essay “Le Peintre de la vie moderne” (The Painter of Modern Life; published in Le Figaro in 1863) encouraged artists to blend in as observers (flâneurs) of modern life and to depict the common scenes of the city and its people in a spontaneous and seemingly unstudied manner. His colleagues Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919) and Edouard Manet (1832–1883) shared Degas’s fascination with hats, fabrics, trimmings, and their creators.11Despite his fascination, Manet seems to have only treated the subject formally in one painting, At the Milliners (1881; Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco) and two watercolors (both 1880; Musée des Beaux-Arts, Dijon). Renoir mostly shied away from portraying the hatmakers themselves, with the notable exceptions of At the Milliners (1878; Harvard Art Museums) and The Milliners (ca. 1879; Metropolitan Museum of Art). Usually, Renoir depicted young women or girls trying on or trimming their own hats (see, for example, Pinning the Hat, 1890 or 1893). Degas, on the other hand, focused intently on the subject of milliners in the early 1880s (with one earlier work from 1876).12He exhibited a pastel entitled Modiste at the second Impressionist exhibition in 1876, but it has not been identified. Degas’s earliest recorded sale of a millinery subject is a pastel, At the Milliners (1881; Metropolitan Museum of Art). Durand-Ruel bought it from the artist in October 1881, and it is therefore dated to that year. See Kelly, “Silk and Feathers,” 42n5. By the end of his life, Degas had created a total of twenty-seven works on the theme of milliners: five paintings (four of which were in his studio at his death), nineteen pastels, two drawings, and the unidentified 1876 Modiste.13Kelly, “Silk and Feathers,” 18.

Junior Milliners is one of Degas’s first dated works of a millinery subject. The artist signed and dated it “1882” in the upper left corner, probably just before he sold it to his dealer, Paul Durand-Ruel, in June of that year. Just over a year later, Durand-Ruel sold it to Alexis Rouart (1839–1911), the brother of the artist Henri Rouart (1833–1912), whom Degas had convinced to exhibit with the Impressionists.14Henri exhibited in all but one of the eight Impressionist exhibitions. From Alexis, Degas borrowed Junior Milliners for the eighth Impressionist exhibition in 1886.15See Edgar Degas to Alexis Rouart, early May 1886, in Theodore Reff, ed., The Letters of Edgar Degas (New York: The Wildenstein Plattner Institute, 2020), 1:400–401 (original French), 3:100 (English translation), as Petites modistes. Of the ten works Degas showed, two were “modistes,” or milliners. At the Milliner’s (Fig. 4), also dated 1882, depicts a fashionably dressed woman (actually Degas’s friend, the artist Mary Cassatt, 1844–1926) trying on hats. A sales assistant stands to her left. The assistant’s face and half of her body are obscured by a large freestanding mirror, and she holds two colorful chapeaus as alternate options.

However, the critics also noted a contrast of social classes.17For an excellent overview of the criticism of the millinery pair, see Martha Ward, “The Eighth Exhibition 1886: The Rhetoric of Independence and Innovation,” in Charles S. Moffett, ed., The New Painting: Impressionism, 1874–1886, exh. cat. (Geneva: Richard Burton SA, 1986), 430–39. Some readings are more inscrutable for modern viewers, but one easily observable difference is between the simple costumes of the three shopgirls versus the more sumptuous olive-brown street dress and lace- or fur-trimmed cape of the customer. The anarchist critic Jean Ajalbert18Jean Ajalbert was a French poet, journalist, art critic, and lawyer. For Ajalbert’s friendship with Paul Signac, see Brigid M. Boyle, “Paul Signac, Portrieux, The Bathing Cabins, Opus 185 (Beach of the Countess), 1888,” in this catalogue, https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.730.5407. See also “Jean Ajalbert,” Angkor Database: A Social Responsibility Project by Templation Angkor Resort, Siem, accessed November 10, 2023, https://angkordatabase.asia/authors/jean-ajalbert. imagined an entire story for At the Milliner’s, where the customer had either eyed the hat in the shop window for a long time, or her jealousy of another behatted woman overtook her, and in either case she hurried to the milliner’s in her wrinkly clothes.19Jean Ajalbert, “Le Salon des Impressionnistes,” La Revue Moderne: Littéraire, Politique et Artistique 3, no. 30 (June 20, 1886): 386. “A cette série, nous préférons les deux pastels de modistes. Une femme essaie un chapeau devant la psyché qui nous dérobe obliquement la modiste. Ce chapeau, elle l’a guetté longtemps à la devanture, ou l’a jalousé à une autre femme: elle s’oublie à scruter sa nouvelle tête; elle imagine des changements, un ruban, une épingle. . . . Quelle pose naturelle, quelle vérité dans cette demi toilette hâtée pour courir chez la modiste“ (Of this series, we prefer the two pastels of milliners. A woman tries on a hat in front of the psyche mirror [a tall, adjustable dressing room mirror], which obliquely reveals the milliner. She watched for this hat for a long time in the window, or was jealous of another woman: she forgets herself scrutinizing her new head; she imagines some changes, a ribbon, a pin. . . . What a natural pose, what truth in this half-dress, as she hurried to run to the milliner). Ajalbert praised the women’s creations in Junior Milliners—“Under their fingers, the hats [are] fabulous, garnished with flowers and birds, becoming gardens or aviaries”—while reminding his readers that the women earn only two francs per day.20Ajalbert, “Le Salon des Impressionnistes,” 386. “Un autre pastel montre l’atelier ou deux ouvrières travaillent; sous leurs doigts les chapeaux fabuleux, se garnissent de fleurs, d’oiseux, vont devenir jardins ou volières, et les chlorotiques modistes, enserrées dans leurs corsets, minces et la figure chiffonnée, et les cheveux frisés à la chien, sont bien de celles qui gagnent deux francs par jour, et édifient des chapeaux a vingt louis, en attendant de les porter” (Another pastel shows the workshop, where two workers are working; under their fingers the fabulous hats, adorned with flowers and birds, will become gardens or aviaries, and the anemic milliners, squeezed in their corsets, thin and with rumpled faces, and hair curled à la chien [French for “as the dog”], are indeed among those who earn two francs a day, and make hats for twenty louis, while waiting to wear them). As such, he deems the women too skinny, with rumpled faces and anemic complexions as a result of their straitened circumstances. Gustave Geffroy took a less sympathetic view, describing the movements of the junior milliners as “simian” or “monkey-like,” whereas he praised the client in At the Milliner’s as “an astonishing silhouette” and a “dream of a frescoed profile against a gold ground.”21Gustave Geffroy, “Salon de 1886: VIII, Hors du Salon. Les Impressionnistes,” La Justice 7, no. 2324 (May 26, 1886): 2, as Petites Modistes. “—des Petites Modistes, sèches, noires, acides, qui touchent à des chapeaux avec la grâce faubourienne de leurs mouvements simiesques ; —une Femme essayant un chapeau chez sa modiste, vêtue de couleurs d’une richesse sourde, levant les deux bras du même geste simplifie, étonnante silhouette qui fait songer à un personnage de fresque profile sur fond d’or” (—Little Milliners, dry, black, acidic, who touch hats with the Faubourian [or suburban] grace of their simian movements; —a Woman trying on a hat at her milliner’s, dressed in muted rich colors, raising both arms in the same simplified gesture, an astonishing silhouette reminiscent of a frescoed profile against a gold background). For an analysis of his commentary, see Anthea Callen, The Spectacular Body: Science, Method and Meaning in the Work of Degas (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 31–35. The comparison to apes is particularly unjust and reveals the racism and classism endemic to nineteenth-century France, and particularly to Geffroy.22For example, Italian criminologist Cesare Lombroso published a famous treatise L’Uomo delinquente (The Criminal Man; 1876) on “biological criminality,” which claimed that the physiognomy of people indicated their likelihood of breaking the law. The popular French science periodical La Nature reviewed his findings in January 1879. See Callen, The Spectacular Body, 1. Callen uses Geffroy’s lens for her reading of Junior Milliners to perpetuate the long-held misconception of Degas as misogynist and classist; she described the rightmost woman in Junior Milliners as having a “protruding lower face and large ears” and a “seemingly dull-witted face.” Callen, The Spectacular Body, 33.

Perhaps one can see the purported anemic complexion in the worker on the left in Junior Milliners, but formally, her blue and yellow tinge probably has more to do with the light reflected from the blue-green wallpaper and the yellow straw hat beside her. Indeed, Degas likely intended a naturalistic effect of her blue veins showing through her translucent skin. Her companion has a ruddier complexion, not unlike the customer in At the Milliners. The hand of the leftmost woman in Junior Milliners is finely rendered with pink and white highlights and sharp black lines, perhaps indicating a thread for sewing on a trim or feather. The other woman, in olive green, holds a straw hat aloft in a movement that seems somewhat physically impossible. Is she flattening the crown of the hat between her thumb and fingertips? Both women arch their little fingers, lending an air of delicate grace to their movements. Degas might have agreed with contemporary French writer Marie-Louise Alquié de Rieupeyrous, known as Louise d’Alq, when she said, “Is there anything more graceful than a girl trimming her hats with her dainty fingers?”23“Est-il rien de plus gracieux qu’une jeune fille chiffonnant ses chapeaux de ses doigts mignons?” Louise d’Alq, La Lingère et la modiste en famille (Paris: Bureaux des Causeries Familières, 1883), 81–82, trans. in Esther Bell, “Edouard Manet, At The Milliner’s,” in Kelly and Bell, Degas, Impressionism, and the Paris Millinery Trade, 138.

The interpretation of these paintings is complicated by the cultural understanding of milliners within the class hierarchy of nineteenth-century Paris.24In the 1880s, authors found fertile ground in newly developed department stores, milliners, and social classes. For example, Émile Zola’s novel on the department store, Au bonheur des Dames (The Ladies’ Paradise, 1883), tells the story of the recently orphaned Denise, who is sent to work at a department store rivaling her uncle’s draper shop, and the women who become obsessed with shopping to the detriment of their families’ livelihoods. Although the novel was published a year after Degas’s pastel was made, Iskin proposed that the artist may have heard of the novel beforehand, since he knew Zola’s publisher. See Ruth E. Iskin, Modern Women and Parisian Consumer Culture in Impressionist Painting (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 79. Another author, Guy de Maupassant, describes the character Mme de Guilleroy enjoying the shops of the dressmaker, the milliner, or corset-maker in his novel Fort comme la mort (Strong as Death, 1889). And Pierre Giffard writes about the department store in Les Grands Bazars: Paris sous la Troisième République (Paris: V. Havard, 1882). Maria d’Anspach’s 1841 essay describes a day in the life of a milliner’s shopgirl: “La Modiste,” in Francais peints par Eux-mêmes (Paris: L. Curmer, 1841), 3:105–12. It was well known that the bottom ranks of millinery staff earned very low wages. Junior trimmers like those in the pastel generally made less than a fifth of what the premières made in a month. Indeed, premières were among the highest paid workers in the garment industry.25Charles Benoist, Les Ouvrières de l’Aiguille à Paris: Notes pour l’Étude de la Question Sociale (Paris: L. Chailley, 1895), 87–88; Kelly, “Silk and Feathers,” 23. According to Benoist, junior trimmers might make between fifty and one hundred francs per month, while premières could make up to five hundred francs per month, or at a large establishment, sometimes as much as seven hundred francs per month. Nevertheless, their compensation paled in comparison to that of a successful artist. Degas earned more than sixteen thousand francs for work sold to Durand-Ruel in 1882,26Rebecca A. Rabinow, Cezanne to Picasso: Ambroise Vollard, Patron of the Avant-Garde, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2006), 161. selling Junior Milliners for 2,500 francs in June27Jean Sutherland Boggs et al., Degas, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1988), 376. and At the Milliner’s the following month for the same price. He made four times as much as the premières and twenty times as much as the junior trimmers.

With such low wages, junior staff sometimes resorted to sex work to supplement their income, a fact that Gustave Coquiot did not miss in his 1924 book on Degas, in which he rhapsodizes about modistes as coquettes and prostitutes.28Gustave Coquiot, Degas (Paris: Librairie Ollendorff, 1924), 130–36. Later art historians like Hollis Clayson and Eunice Lipton have also read Degas’s works as a representation of clandestine prostitution.29Hollis Clayson, Painted Love: Prostitution in French Art of the Impressionist Era (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1991), 113–32; and Eunice Lipton, Looking into Degas: Uneasy Images of Women and Modern Life (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986), 151–86. However, a detail in Junior Milliners makes it doubtful that Degas intended the women to be seen in this context: there on the fourth finger of the leftmost woman’s raised left hand is a gold ring. It could be a wedding ring, indicating that the woman may have had a spouse’s income, lessening her need for supplementing her livelihood.

Nevertheless, Degas was accused of misogyny for the first time at the 1886 Impressionist exhibition.30Boggs et al., Degas, 385. The criticism was primarily focused on his series of nude bathers (in works similar to the Nelson-Atkins After the Bath), but commentary like Geffroy’s about the “simian movements” of the junior milliners is blatantly contemptuous and seems to detect a misogyny in Degas that may not have existed.31Norma Broude first rebutted the idea of Degas’s contempt for women in Broude, “Degas’s ‘Misogyny,’” Art Bulletin 59, no. 1 (March 1977): 95–107. Kelly uses the series of millinery pictures to further Broude’s argument for a more nuanced and positive reading of Degas’s portrayal of women; see Kelly, “Silk and Feathers,” 17–41. A comparison between Degas’s quiet, statuesque artisans in Junior Milliners and the contemporaneous criticism makes it evident that while Degas’s depictions were not particularly classist or anti-feminist, the critics certainly were. As Martha Ward has argued, “in images like Petites Modistes [Junior Milliners], Degas exposed or exploited society’s own seemingly ‘unwillful’ debasement of women: the sort of bias that permeated culture through its colloquial representations and insidiously appropriated the ranks of ‘natural affinities’ for social orders.”32Ward, “The Eighth Exhibition 1886,” 433.

Junior Milliners is not visually anti-feminist. However, its historic title, Petites Modistes, under which it was exhibited in 1886, has confused the issue. Translated literally as “Little Milliners,” it seems to give a pejorative meaning to the workers, especially since the women do not seem particularly young or small. Indeed, they are probably adults in their twenties, and one of them appears to be married. The millinery profession encompassed many roles, and businesses were rarely one-woman operations (although some smaller shops did function that way). Larger establishments had many employees. For example, a photograph of the salon of the modiste Alphonsine shows at least nine women huddled together in a back room, with hats and flowers on their laps (Fig. 5). The millinery staff usually included, from the lowest ranks, the apprentice, sometimes also called the trottin (or runner), who, beginning at the age of thirteen, would deliver packages and run errands; the formière (or former), a girl of about sixteen who created the framework for the hat; the apprêteuse (or preparer), a girl ranging in age from sixteen to twenty-two who draped fabric over the hat frames and would eventually learn to sew straw and fabrics into shape; the garnisseuse (or trimmer), a woman of about twenty-two who was responsible for decorating the hat; the sèconde, who supervised her colleagues; and finally the première, who was the creative lead of the shop, responsible for designing new styles, assisting clients in trying on the merchandise, and overseeing all the other assistants.33Arsène Alexandre, Les Reines de l’Aiguille: Modistes et Couturières (Étude Parisienne) (Paris: T. Belin, 1902), 143–44; Benoist, Les Ouvrières de l’Aiguille à Paris, 87–88; Kelly, “Silk and Feathers,” 22–23; and Tétart-Vittu, “The Milliners of Paris,” 53. In larger establishments, there were several premières, who supervised various subdepartments, and several preparers and trimmers, including the petite (or junior) and the bonne (or accomplished) apprêteuses and garnisseuses. Therefore, the women in Degas’s pastel who are placing ribbons, feathers, and flowers on straw hats are doing the work of the trimmers, and they are not “little” per se but instead fulfilling the specific job rank of “junior.”34Kelly first made this point in “Silk and Feathers,” 22–23.

Notes

-

Maurice Praslières, “Un Grande Modiste au XXe Siècle,” Les Modes, no. 46 (October 1904): 20. “Mais c’est tout un poème qu’un chapeau; c’est une symphonie, c’est une mélodie, c’est toujours un chef-d’oeuvre à créer.” All translations by Meghan L. Gray, unless otherwise noted. Written to advertise the modiste Alphonsine’s new headquarters, the article emphasizes all her best qualities, including her ability to speak six languages and her extensive travels, and pays particular attention to her appreciation of great eighteenth-century artists like Jean Marc Nattier (1685–1766), François Boucher (1703–70), and Antoine Watteau (1684–1721). The author likens Alphonsine’s expertise to the highest echelons of the artistic hierarchy.

-

Of nearly one thousand millinery shops in Paris in 1870, about 86 percent were women-owned businesses. Francoise Tétart-Vittu, “The Milliners of Paris, 1870–1910,” in Simon Kelly and Esther Bell, Degas, Impressionism, and the Paris Millinery Trade, exh. cat. (San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 2017), 52.

-

For more on the frame, see the technical entry by Rachel Freeman accompanying this essay. A photograph of a room of Loan Exhibition of Masterpieces by Old and Modern Painters, M. Knoedler and Co., New York, in 1915 seems to show the pastel framed without the spacers; reproduced in Frances Weitzenhoffer, The Havemeyers: Impressionism Comes to America (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1986), 224.

-

“Description des Chapeaux,” Modiste Universelle 6, no. 6 (March 1882): 2, under no. 4, model no. 264. The publication was offered in five languages, including English.

-

“Confections en Gros pour Dames et Enfants: Cyprienne,” La Mode Actuelle: Journal professionnel des couturières et des modistes (April 1, 1882): 9. “Chapeau de paille noire garni de fleurs et plumes.”

-

The pastel is dated to 1882 and must have been made before June, when Degas sold it to his dealer Paul Durand-Ruel, meaning that he worked on it between January and June of that year.

-

Kelly, “‘Silk and Feathers, Satin and Straw’: Degas, Women, and the Paris Millinery Trade,” in Kelly and Bell, Degas, Impressionism, and the Paris Millinery Trade, 20.

-

Michelle Foa, “In Transit: Edgar Degas and the Matter of Cotton, between New World and Old,” Art Bulletin 102, no. 3 (September 2020): 54–76. Degas’s family owned and made money from enslaved people.

-

Foa, “In Transit,” esp. 64–67.

-

Degas and his colleagues were influenced by the writings of Charles Baudelaire, whose essay “Le Peintre de la vie moderne” (The Painter of Modern Life; published in Le Figaro in 1863) encouraged artists to blend in as observers (flâneurs) of modern life and to depict the common scenes of the city and its people in a spontaneous and seemingly unstudied manner.

-

Despite his fascination, Manet seems to have only treated the subject formally in one painting, At the Milliners (1881; Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco) and two watercolors (both 1880; Musée des Beaux-Arts, Dijon).

-

He exhibited a pastel entitled Modiste at the second Impressionist exhibition in 1876, but it has not been identified. Degas’s earliest recorded sale of a millinery subject is a pastel, At the Milliners (1881; Metropolitan Museum of Art). Durand-Ruel bought it from the artist in October 1881, and it is therefore dated to that year. See Kelly, “Silk and Feathers,” 42n5.

-

Kelly, “Silk and Feathers,” 18.

-

Henri exhibited in all but one of the eight Impressionist exhibitions.

-

See Edgar Degas to Alexis Rouart, early May 1886, in Theodore Reff, ed., The Letters of Edgar Degas (New York: The Wildenstein Plattner Institute, 2020), 1:400–401 (original French), 3:100 (English translation), as Petites modistes.

-

Kelly also makes this connection between the two pastels; Kelly, “Silk and Feathers,” 37.

-

For an excellent overview of the criticism of the millinery pair, see Martha Ward, “The Eighth Exhibition 1886: The Rhetoric of Independence and Innovation,” in Charles S. Moffett, ed., The New Painting: Impressionism, 1874–1886, exh. cat. (Geneva: Richard Burton SA, 1986), 430–39.

-

Jean Ajalbert was a French poet, journalist, art critic, and lawyer. For Ajalbert’s friendship with Paul Signac, see Brigid M. Boyle, “Paul Signac, Portrieux, The Bathing Cabins, Opus 185 (Beach of the Countess), 1888,” in this catalogue. See also “Jean Ajalbert,” Angkor Database: A Social Responsibility Project by Templation Angkor Resort, Siem, accessed November 10, 2023, https://angkordatabase.asia/authors/jean-ajalbert.

-

Jean Ajalbert, “Le Salon des Impressionnistes,” La Revue Moderne: Littéraire, Politique et Artistique 3, no. 30 (June 20, 1886): 386. “A cette série, nous préférons les deux pastels de modistes. Une femme essaie un chapeau devant la psyché qui nous dérobe obliquement la modiste. Ce chapeau, elle l’a guetté longtemps à la devanture, ou l’a jalousé à une autre femme: elle s’oublie à scruter sa nouvelle tête; elle imagine des changements, un ruban, une épingle. . . . Quelle pose naturelle, quelle vérité dans cette demi toilette hâtée pour courir chez la modiste” (Of this series, we prefer the two pastels of milliners. A woman tries on a hat in front of the psyche mirror [a tall, adjustable dressing room mirror], which obliquely reveals the milliner. She watched for this hat for a long time in the window, or was jealous of another woman: she forgets herself scrutinizing her new head; she imagines some changes, a ribbon, a pin. . . . What a natural pose, what truth in this half-dress, as she hurried to run to the milliner).

-

Ajalbert, “Le Salon des Impressionnistes,” 386. “Un autre pastel montre l’atelier ou deux ouvrières travaillent; sous leurs doigts les chapeaux fabuleux, se garnissent de fleurs, d’oiseux, vont devenir jardins ou volières, et les chlorotiques modistes, enserrées dans leurs corsets, minces et la figure chiffonnée, et les cheveux frisés à la chien, sont bien de celles qui gagnent deux francs par jour, et édifient des chapeaux a vingt louis, en attendant de les porter” (Another pastel shows the workshop, where two workers are working; under their fingers the fabulous hats, adorned with flowers and birds, will become gardens or aviaries, and the anemic milliners, squeezed in their corsets, thin and with rumpled faces, and hair curled à la chien [French for “as the dog”], are indeed among those who earn two francs a day, and make hats for twenty louis, while waiting to wear them).

-

Gustave Geffroy, “Salon de 1886: VIII, Hors du Salon. Les Impressionnistes,” La Justice 7, no. 2324 (May 26, 1886): 2, as Petites Modistes. “—des Petites Modistes, sèches, noires, acides, qui touchent à des chapeaux avec la grâce faubourienne de leurs mouvements simiesques ; —une Femme essayant un chapeau chez sa modiste, vêtue de couleurs d’une richesse sourde, levant les deux bras du même geste simplifie, étonnante silhouette qui fait songer à un personnage de fresque profile sur fond d’or” (—Little Milliners, dry, black, acidic, who touch hats with the Faubourian [or suburban] grace of their simian movements; —a Woman trying on a hat at her milliner’s, dressed in muted rich colors, raising both arms in the same simplified gesture, an astonishing silhouette reminiscent of a frescoed profile against a gold background). For an analysis of his commentary, see Anthea Callen, The Spectacular Body: Science, Method and Meaning in the Work of Degas (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 31–35.

-

For example, Italian criminologist Cesare Lombroso published a famous treatise L’Uomo delinquente (The Criminal Man; 1876) on “biological criminality,” which claimed that the physiognomy of people indicated their likelihood of breaking the law. The popular French science periodical La Nature reviewed his findings in January 1879. See Callen, The Spectacular Body, 1. Callen uses Geffroy’s lens for her reading of Junior Milliners to perpetuate the long-held misconception of Degas as misogynist and classist; she described the rightmost woman in Junior Milliners as having a “protruding lower face and large ears” and a “seemingly dull-witted face.” Callen, The Spectacular Body, 33.

-

“Est-il rien de plus gracieux qu’une jeune fille chiffonnant ses chapeaux de ses doigts mignons?” Louise d’Alq, La Lingère et la modiste en famille (Paris: Bureaux des Causeries Familières, 1883), 81–82, trans. in Esther Bell, “Edouard Manet, At The Milliner’s,” in Kelly and Bell, Degas, Impressionism, and the Paris Millinery Trade, 138.

-

In the 1880s, authors found fertile ground in newly developed department stores, milliners, and social classes. For example, Émile Zola’s novel on the department store, Au bonheur des Dames (The Ladies’ Paradise, 1883), tells the story of the recently orphaned Denise, who is sent to work at a department store rivaling her uncle’s draper shop, and the women who become obsessed with shopping to the detriment of their families’ livelihoods. Although the novel was published a year after Degas’s pastel was made, Iskin proposed that the artist may have heard of the novel beforehand, since he knew Zola’s publisher. See Ruth E. Iskin, Modern Women and Parisian Consumer Culture in Impressionist Painting (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 79. Another author, Guy de Maupassant, describes the character Mme de Guilleroy enjoying the shops of the dressmaker, the milliner, or corset-maker in his novel Fort comme la mort (Strong as Death, 1889). And Pierre Giffard writes about the department store in Les Grands Bazars: Paris sous la Troisième République (Paris: V. Havard, 1882). Maria d’Anspach’s 1841 essay describes a day in the life of a milliner’s shopgirl: “La Modiste,” in Francais peints par Eux-mêmes (Paris: L. Curmer, 1841), 3:105–12.

-

Charles Benoist, Les Ouvrières de l’Aiguille à Paris: Notes pour l’Étude de la Question Sociale (Paris: L. Chailley, 1895), 87–88; Kelly, “Silk and Feathers,” 23. According to Benoist, junior trimmers might make between fifty and one hundred francs per month, while premières could make up to five hundred francs per month, or at a large establishment, sometimes as much as seven hundred francs per month.

-

Rebecca A. Rabinow, Cezanne to Picasso: Ambroise Vollard, Patron of the Avant-Garde, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2006), 161.

-

Jean Sutherland Boggs et al., Degas, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1988), 376.

-

Gustave Coquiot, Degas (Paris: Librairie Ollendorff, 1924), 130–36.

-

Hollis Clayson, Painted Love: Prostitution in French Art of the Impressionist Era (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1991), 113–32; and Eunice Lipton, Looking into Degas: Uneasy Images of Women and Modern Life (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986), 151–86.

-

Boggs et al., Degas, 385.

-

Norma Broude first rebutted the idea of Degas’s contempt for women in Broude, “Degas’s ‘Misogyny,’” Art Bulletin 59, no. 1 (March 1977): 95–107. Kelly uses the series of millinery pictures to further Broude’s argument for a more nuanced and positive reading of Degas’s portrayal of women; see Kelly, “Silk and Feathers,” 17–41.

-

Ward, “The Eighth Exhibition 1886,” 433.

-

Arsène Alexandre, Les Reines de l’Aiguille: Modistes et Couturières (Étude Parisienne) (Paris: T. Belin, 1902), 143–44; Benoist, Les Ouvrières de l’Aiguille à Paris, 87–88; Kelly, “Silk and Feathers,” 22–23; and Tétart-Vittu, “The Milliners of Paris,” 53.

-

Kelly first made this point in “Silk and Feathers,” 22–23.

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Rachel Freeman, “Edgar Degas, Junior Milliners, 1882,” technical entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.618.2088.

MLA:

Freeman, Rachel. “Edgar Degas, Junior Milliners, 1882,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.618.2088.

Junior Milliners was completed during a period when Edgar Degas depicted both the Parisian well-to-do and the working classes in both canvas and pastelpastel: A type of drawing stick made from finely ground pigments or other colorants (dyes), fillers (often ground chalk), and a small amount of a polysaccharide binder (gum arabic or gum tragacanth). While many artists made their own pastels, during the nineteenth century, pastels were sold as sticks, pointed sticks encased in tightly wound paper wrappers, or as wood encased pencils. Pastels can be applied dry, dampened, or wet, and they can be manipulated with a variety of tools including paper stumps, chamois cloth, brushes, or fingers. Pastel can also be ground and applied as a powder, or mixed with water to form a paste. Pastel is a friable media, meaning that it is powdery or crumbles easily. To overcome this difficulty, artists have used a variety of fixatives to prevent image loss. paintings. Junior Milliners focuses on two young female shop assistants as they decorate fashionable hats. In addition to the pastel painting materials and technique, this entry focuses on the frame, which is original to the artwork and appears to have been designed by Degas.

At 48.9 x 71.8 centimeters, the primary support is within range of the Marine 20 size standard-format supportstandard-format supports: Commercially prepared supports available through art suppliers, which gained popularity in the nineteenth century during the industrialization of art materials. Available in three formats figure (portrait), paysage (landscape), and marine (marine), these were numbered 1 through 120 to indicate their size. For each numbered size, marine and paysage had two options available: a larger format (haute) and smaller (basse) format..1David Bomford, Jo Kirby, John Leighton, and Ashok Roy, Art in the Making: Impressionism (London: Yale University Press, 1991), 46. The primary support is a gray-toned, medium thickness, wove paperwove paper: One of the two types of paper. Wove papers may be either machine or handmade, and are produced from molds that have a woven wire mesh. The weave of the mesh can be so tight that it produces no visible pattern within the paper sheet, and often wove papers have a smoother surface than laid papers. Wove papers were developed during the mid-eighteenth century, but did not come into widespread use until later. The other type of paper is laid paper.. Prior to media application, the corners were trimmed, and the edges are turned over a paperboard2Paperboard refers to ”stiff and thick ‘paper’ which may range from a ‘card’ of 0.20 mm or 1/125th of an inch or more and vary in composition from pure rag to wood, straw, and other substances having little or no affinity with ‘paper’ beyond the method of manufacture.“ See E. J. Labarre, A Dictionary of Paper and Paper-Making Terms (Amsterdam: N. V. Swets and Zeitlinger, 1937), 208–09. The board may also be a panel. Panels or panel boards are stiff and tough multi-ply boards composed of leather and/or waste papers. They were saturated with oils and hardened with heat. E. J. Labarre, Dictionary, 182. and attached, at the edges only, to the verso, with a 3.5 to 4.5 cm overlap. Chromatically, the paper reads as beige to brown;3The description of paper color, texture, and thickness follows the standard set forth in Elizabeth Lunning and Roy Perkinson, The Print Council of America Paper Sample Book: A Practical Guide to the Description of Paper (Boston: Print Council of America, 1996), unpaginated. In this case, there is no good color match for the paper: it is between the darkest beige and the brown. however, close inspection reveals that it was manufactured from a mixed furnishfurnish: in paper making, furnish refers to the fibers that compose the paper as well as to the mixture of fibers and water that eventually form the paper sheet. with longer and shorter fibers in both light and dark blue as well as black and brown fibers scattered throughout.4“Mottled” papers were composed of mixed furnish taken from various sources such as dyed linen, cotton, Union (fabric made from a linen, wool, or cotton warp and a wool weft), and wool rags or fibers, as well as jute fibers, and dyed or bleached sulphite wood pulps. See Julius Erfurt, The Dying of Paper Pulp (London: Scott, Greenwood and Co., 1901), 141–52. The rough paper texture suggests that it was produced specifically for charcoal, chalk, or pastel. There is no watermarkwatermark: An identifying mark in a paper sheet which is created by tying wires to the papermaking mold. Watermarks are most easily viewed with transmitted light; however, some can be read with raking light. or other indication of either a mill or colorman’s shopartist supplier(s): Also called colormen and color merchants. Artist suppliers prepared materials for artists. This tradition dates back to the Medieval period, but the industrialization of the nineteenth century increased their commerce. It was during this time that ready-made paints in tubes, commercially prepared canvases, and standard-format supports were available to artists for sale through these suppliers. It is sometimes possible to identify the supplier from stamps or labels found on the reverse of the artwork (see canvas stamp and supplier mark). where the drawing paper was attached to the paperboard. The paperboard is gray in tone, and the back of the board was sealed with a blue-gray paint prior to application of the drawing paper (Fig. 6).5Nineteenth-century Parisian colormen’s catalogues list “Panneaux et Cartons d’Etudes” (Panels and Boards for Studies), fabricated specifically for pastel. See *Fabrique de Couleurs et Vernis, Toiles à Peindre, Carmin, Laques, Jaunes de Chrome de Spooner, Couleurs en Tablettes et en Pastilles, Pastels, et Généralment Tout Ce Qui Concerne la Peinture et les Arts, Encres Noires et de Couleurs Pour la Typograpie et la Lithographie, Fabrique à Grenelle (Paris: Le Franc, 1862), 40. The advertised sizes do not correspond to the artwork’s dimensions. However, it is difficult to dismiss the possibility that the artist modified a panel to fit his qualifications.

There is no evidence of fixativefixative: An adhesive or varnish that is applied to the surface of powdery media (pastel, chalk, charcoal, or graphite pencil) to prevent smudging or smearing. Fixatives may be applied during the composition process, so that new layers of media can be added without disturbing the underlayers, or after the artwork is complete. Historic fixatives include natural resins, vegetable gums or starches, animal or fish glues, casein, egg white, and a variety of other materials. In the nineteenth century, cellulose nitrate and other early synthetic polymers were available, and in the twentieth century, acrylics and polyvinyl co-polymers were included in fixative solutions. Until the early twentieth century, when methods for containing pressurized gasses were developed and disposable spray cans became common, the fixative could be spattered over the paper with a brush or applied with an atomizer (also called a blow-pipe or mouth sprayer)., and, possibly in a complement to the colors of the wallpaper, the artist signed and dated the drawing at upper left with the tip of a blue pastel: “1882 Degas” (Fig. 9).

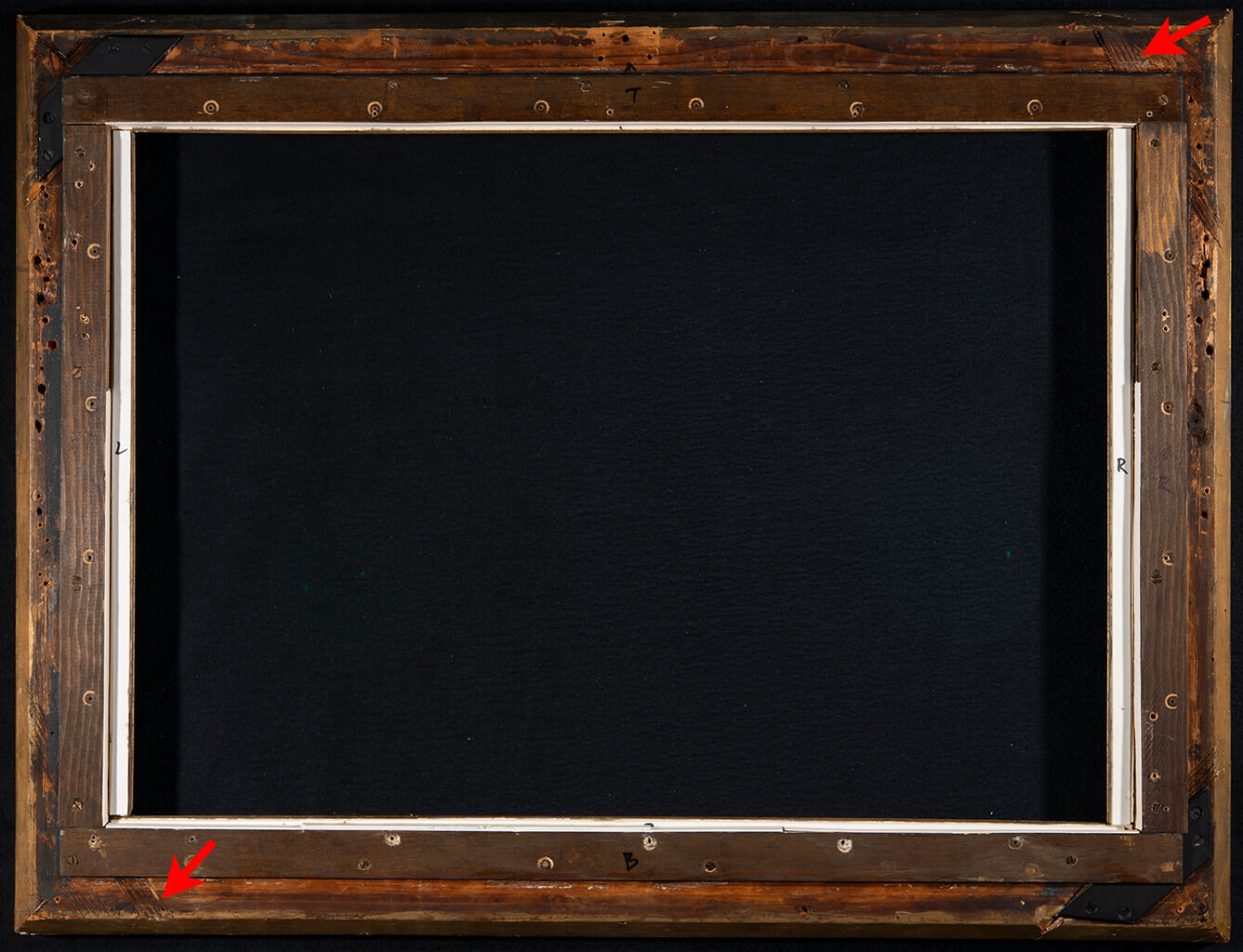

Fig. 11. The back of the frame with the spline at at lower left and upper right indicated with arrows. The large metal pieces on the lower corners and at upper left and lower right are old metal repairs to the miters. The conservation department at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art built out the back of the frame with beveled wooden strips to accommodate a modern framing package and lined the rebate to better protect the artwork, Junior Milliners (1882).

Fig. 11. The back of the frame with the spline at at lower left and upper right indicated with arrows. The large metal pieces on the lower corners and at upper left and lower right are old metal repairs to the miters. The conservation department at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art built out the back of the frame with beveled wooden strips to accommodate a modern framing package and lined the rebate to better protect the artwork, Junior Milliners (1882).

Fig. 12. Photomicrograph of the area at right, Junior Milliners (1882). The white is the collar of the milliner at right. The photomicrograph shows randomly scattered, short, and very fine cuts in the surface of the paper. This is a damage pattern caused by glass shards when glazing shatters.

Fig. 12. Photomicrograph of the area at right, Junior Milliners (1882). The white is the collar of the milliner at right. The photomicrograph shows randomly scattered, short, and very fine cuts in the surface of the paper. This is a damage pattern caused by glass shards when glazing shatters.

Notes

-

David Bomford, Jo Kirby, John Leighton, and Ashok Roy, Art in the Making: Impressionism (London: Yale University Press, 1991), 46.

-

Paperboard refers to “stiff and thick ‘paper’ which may range from a ‘card’ of 0.20 mm or 1/125th of an inch or more and vary in composition from pure rag to wood, straw, and other substances having little or no affinity with ‘paper’ beyond the method of manufacture.” See E. J. Labarre, A Dictionary of Paper and Paper-Making Terms (Amsterdam: N. V. Swets and Zeitlinger, 1937), 208–09. The board may also be a panel. Panels or panel boards are stiff and tough multi-ply boards composed of leather and/or waste papers. They were saturated with oils and hardened with heat. E. J. Labarre, Dictionary, 182.

-

The description of paper color, texture, and thickness follows the standard set forth in Elizabeth Lunning and Roy Perkinson, The Print Council of America Paper Sample Book: A Practical Guide to the Description of Paper (Boston: Print Council of America, 1996), unpaginated. In this case, there is no good color match for the paper: it is between the darkest beige and the brown.

-

“Mottled” papers were composed of mixed furnish taken from various sources such as dyed linen, cotton, Union (fabric made from a linen, wool, or cotton warp and a wool weft), and wool rags or fibers as well as jute fibers and dyed or bleached sulphite wood pulps. See Julius Erfurt, The Dying of Paper Pulp (London: Scott, Greenwood and Co., 1901), 141–52.

-

Nineteenth-century Parisian colormen’s catalogues list “Panneaux et Cartons d’Etudes” (Panels and Boards for Studies), fabricated specifically for pastel. See Fabrique de Couleurs et Vernis, Toiles à Peindre, Carmin, Laques, Jaunes de Chrome de Spooner, Couleurs en Tablettes et en Pastilles, Pastels, et Généralment Tout Ce Qui Concerne la Peinture et les Arts, Encres Noires et de Couleurs Pour la Typograpie et la Lithographie, Fabrique à Grenelle (Paris: Le Franc, 1862), 40. The advertised sizes do not correspond to the artwork’s dimensions. However, it is difficult to dismiss the possibility that the artist modified a panel to fit his qualifications.

-

The photograph is published in Frances Weitzenhoffer, The Havemeyers: Impressionism Comes to America (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1986), 224.

-

Elizabeth Easton and Jared Bark, “‘Pictures Properly Framed’: Degas and Innovation in Impressionist Frames,” Burlington Magazine, no. 1266 (September 2008): 603–11.

-

Edgar Degas, The Collector of Prints, 1866, oil on canvas, 20 7/8 x 15 3/4 in. (53 x 40 cm), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Bequest of Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer, 1929, 29.100.44, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/ search/436122.

-

See provenance information. Havemeyer also owned Rehearsal of the Ballet, and her autobiography includes detailed accounts of Degas’s frames and the meaning he attached to them. Louisine W. Havemeyer, Sixteen to Sixty: Memoirs of a Collector, ed. Susan Alyson Stein, 2nd ed. (New York: Ursus Press, 1993), 250.

-

Easton and Bark, “‘Pictures Properly Framed,’” 607.

-

The author has documented wooden spacers, attached with brads, to other Impressionist pastels. Rachel Freeman, “Manet, Cat. 21, The Man with the Dog: Technical Report,” in Manet Paintings and Works on Paper at the Art Institute of Chicago (Art Institute of Chicago, 2017), para 25, https://publications.artic.edu/manet/reader/manetart/section/140052. In the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art collection, Daydreaming by Berthe Mosisot (F79-47) has similar brad holes and wear. See Rachel Freeman, “Berthe Morisot, Daydreaming, 1877,” technical entry, in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022).

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Edgar Degas, Junior Milliners, 1882,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.618.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Edgar Degas, Junior Milliners, 1882,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.618.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Edgar Degas, Junior Milliners, 1882,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.618.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Edgar Degas, Junior Milliners, 1882,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.618.4033.

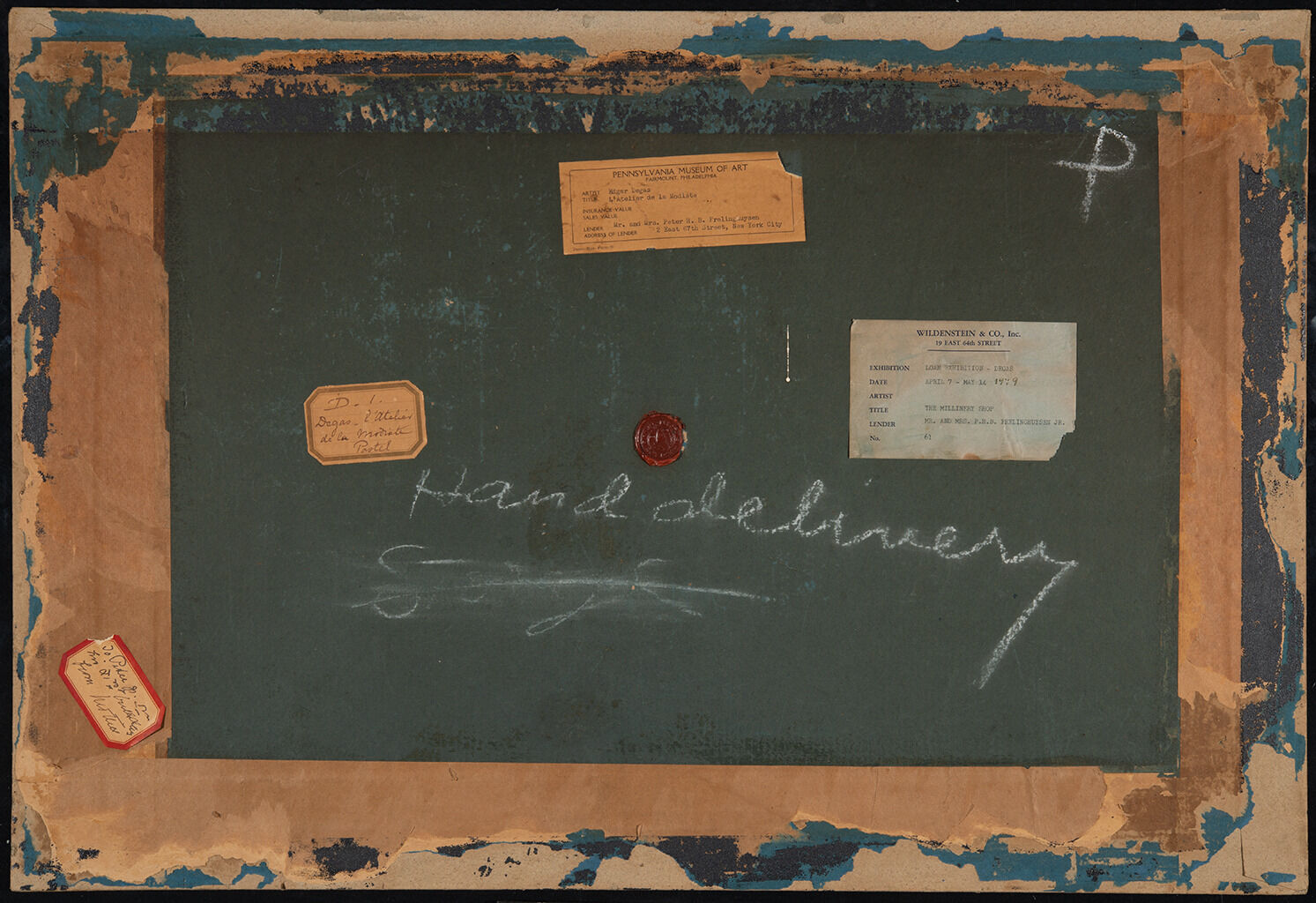

Purchased from the artist by Galerie Durand-Ruel, Paris, stock no. 2421, as Les Modistes, June 5, 1882–July 10, 1883 [1];

Purchased from Durand-Ruel by Alexis Rouart (1839–1911), Paris, 1883–January 2, 1911 [2];

Purchased at his posthumous sale, Tableaux par Baron (H.), Bonvin (F.), Boudin (E.), Cabat (L.), Cals (A. -F.), Chintreuil, Ciceri (E.), Colin (G.), Corot (C.), Couture (T.), Daumier (H.), Dehondencq, Devéria (E.), Dreux (A. de), Drolling (M.), Dufeu (e.), Fantin-Latour, Forain (J.-L.), Gavarni, Granet, Heim (F.-J.), Helleu, Jongkind, Johannot, Lepaulle (F.-G.), Lépine (S.), Noel (J.), Pissaro [sic] (C.), Roqueplan (C.), Rousseau (T.-H.), Tassaert (O.), (Vernet H.), etc., Aquarelles, Pastels, Dessins, Miniatures par Cassatt (Mary), Daumier (H.), Forain (J.-L.), Gavarni, Guérin (P.), Hervier, Millet (J.-F.), Monnier (H.), Raffet. Œuvres Importantes d’Eugène Lami, Pastels et Gouache, par Degas, Composant la Collection de Feu M. Alexis Rouart, Hôtel Drouot, Paris, lot 214, as L’Atelier de la modiste, by Durand-Ruel, Paris, for Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer (née Louisine Elder, 1855–1929), New York, May 9, 1911–no later than January 6, 1929;

To her daughter, Mrs. Peter Hood Ballantine Frelinghuysen (née Adaline Havemeyer, 1884–1963), Morristown, NJ, and Palm Beach, FL, by April 10, 1930–January 17, 1937 [3];

Her gift to her son, Peter Hood Ballantine Frelinghuysen, Jr. (1916–2011), Morristown, NJ, 1937–September 24, 1979 [4];

Purchased from Frelinghuysen by The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1979.

Notes

-

See email from Paul-Louis Durand-Ruel and Flavie Durand-Ruel, Durand-Ruel et Cie., Paris, to Nicole Myers, NAMA, January 11, 2016; and email from Paul-Louis Durand-Ruel and Flavie Durand-Ruel, Durand-Ruel et Cie., Paris, to Meghan Gray, NAMA, February 5, 2016, NAMA curatorial file.

-

Ibid.

-

It is possible that Mrs. Havemeyer gave the pastel to her daughter when she married on February 7, 1907; see Louisine Havemeyer, “Notes to My Children,” undated, Box 3, Folder 23, Havemeyer Family Papers relating to Art Collecting, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives, New York. Mrs. Frelinghuysen must have had the pastel by the time Havemeyer’s art collection was sold on April 10, 1930.

-

See paper label on the pastel’s verso, which is inscribed: “To Peter Jr. on / his 21st birthday / from Mother.”

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Edgar Degas, Junior Milliners, 1882,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.618.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Edgar Degas, Junior Milliners, 1882,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.618.4033.

Edgar Degas, At the Milliner’s (Femme essayant un chapeau chez sa modiste), 1882, pastel on pale gray wove paper, laid down on silk bolting, 30 x 34 in. (76.2 x 86.4 cm), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. H. O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer, 1929, 29.100.38.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Edgar Degas, Junior Milliners, 1882,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.618.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Edgar Degas, Junior Milliners, 1882,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.618.4033.

8me Exposition de Peinture [8th Impressionist Exhibition], 1, rue Laffitte, Paris, May 15–June 15, 1886, no. 15, as Petites Modistes.

Loan Exhibition of Masterpieces by Old and Modern Painters, M. Knoedler and Co., New York, April 6–24, 1915, no. 36, as The Milliners.

Possibly Exhibition of Paintings by the Master Impressionists, Durand-Ruel, New York, April 8–20, 1929, no. 3, as L’atelier de la modiste.

Degas, 1834–1917, The Pennsylvania Museum of Art, Fairmont, PA, 1936, no. 37, as The Millinery Shop, L’Atelier de la modiste, Petites modistes.

A loan exhibition of Degas for the benefit of the New York Infirmary, Wildenstein and Co., Inc., New York, April 7–May 14, 1949, no. 61, as The Millinery Shop.

Degas: Loan Exhibition for the Benefit of The Citizens’ Committee for the Children of New York, Inc., Wildenstein and Co., New York, April 7–May 7, 1960, no. 34, as Petites Modistes.

“One Hundred Years of Impressionism:” A Tribute to Durand-Ruel; A Loan Exhibition For the Benefit of the New York University Art Collection, Wildenstein, New York, April 2–May 9, 1970, no. 55, as Petites Modistes.

European and American Art from Princeton Alumni Collections, The Art Museum, Princeton University, May 7–June 11, 1972, no. 71, as L’Atelier de la modiste.

Genre, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, April 5–May 15, 1983, no. 36B, as The Shop of the Modiste.

A Bountiful Decade: Selected Acquisitions 1977–1987, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, October 14–December 6, 1987, no. 48, as The Milliners (L’Atelier de la modiste).

Impressionism: Selections from Five American Museums, The Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, November 4–December 31, 1989; The Minneapolis Institute of Arts, January 27–March 25, 1990; The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, April 21–June 17, 1990; The Saint Louis Art Museum, July 14–September 9, 1990; The Toledo Museum of Art, September 30–November 25, 1990, no. 19 (Kansas City only), as Little Milliners.

Crowning Glory: Millinery in Paris, 1880–1905, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, December 10, 2022–December 3, 2023, no cat.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Edgar Degas, Junior Milliners, 1882,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.618.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Edgar Degas, Junior Milliners, 1882,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.618.4033.

1886: Catalogue de la 8me Exposition de Peinture par Marie Bracquemond, Mary Cassatt, Degas, Forain, Gauguin, Guillaumin, Berthe Morisot, C. Pissarro, Lucien Pissarro, Odilon Redon, Rouart, Schuffenecker, Seurat, Signac, Tillot, Vignon, Zandomeneghi, exh. cat. (Paris: Morris père et fils, 1886), 6, as Petites modistes.

Rodolphe Darzens, La Pleiade (May 1886): 91.

Henry Fèvre, La Revue de Demain (May–June 1886): 154.

F., “Exposition de Peinture: 1, rue Laffitte,” Le Gaulois 20, no. 1358 (May 16, 1886): 2, as Chez la modiste.

Le Masque de Fer, “Echos de Paris,” Le Figaro 32, no. 136 (May 16, 1886): 2, les Petites Modistes.

Marcel Fouquier, “Les Impressionnistes,” Le XIXe siècle, no. 5241 (May 16, 1886): 16.

Henry Havard, “La Peinture Indépendante: Huitième Exposition des Impressionnistes,” Le Siècle 51, no. 18,406 (May 17, 1886): unpaginated.

Labruyère, “Les Impressionnistes,” Le Cri du Peuple 3, no. 931 (May 17, 1886): 2.

Roger Marx, “Les Impressionnistes,” Le Voltaire (May 17, 1886): unpaginated, as Modistes.

“L’Exposition des Indépendants,” Le Moniteur des Arts 29, no. 1653 (May 21, 1886): 174.

Octave Mirbeau, “Exposition de peinture (1, rue Laffitte),” La France (May 21, 1886): unpaginated, as deux intérieurs de modistes.

Gustave Geoffroy, “Salon de 1886: VIII, Hors du Salon. Les Impressionnistes,” La Justice 7, no. 2324 (May 26, 1886): 2, as Petites Modistes.

Maurice Hermel, “L’exposition de peinture de la rue Laffitte,” La France Libre (May 27, 1886): 2.

Jules Vidal, “Les impressionnistes,” Lutèce 5, no. 239 (May 29–June 5, 1886; repr., Geneva: Slatkine Reprints, 1973): unpaginated.

Alfred Paulet, “Les Impressionnistes,” Paris (June 5, 1886).

Possibly H. [pseud.], “Les Impressionnistes,” Journal des Arts 5, no. 24 (June 11, 1886).

Jules Christophe, “Chronique: Rue Laffitte, No. 1,” Journal des Artistes 5, no. 24 (June 13, 1886): 193.

Félix Fénéon, “Les Impressionnistes,” La Vogue, no. 8 (June 13–20, 1886): 264.

Edmond Jacques, “Le Salon,” L’Intransigeant 94, no. 2165 (June 18, 1886): 2.

Jean Ajalbert, “Le Salon des Impressionnistes,” La Revue Moderne: Littéraire, Politique et Artistique 3, no. 30 (June 20, 1886): 386.

[Octave Maus], “Les Vingtistes Parisiens,” L’Art Moderne (Brussels) 6, no. 26 (June 27, 1886): 202.

Félix Fénéon, Les Impressionnistes en 1886, rev. ed. (1886; Paris: La Vogue, 1886), 11.

Paul A. Lemoisne, “La Collection de M. Alexis Rouart,” Les Arts, no. 75 (March 1908): 31, (repro.), as Les Modistes.

Catalogue des Tableaux par Baron (H.), Bonvin (F.), Boudin (E.), Cabat (L.), Cals (A. -F.), Chintreuil, Ciceri (E.), Colin (G.), Corot (C.), Couture (T.), Daumier (H.), Dehondencq, Devéria (E.), Dreux (A. de), Drolling (M.), Dufeu (e.), Fantin-Latour, Forain (J.-L.), Gavarni, Granet, Heim (F.-J.), Helleu, Jongkind, Johannot, Lepaulle (F.-G.), Lépine (S.), Noel (J.), Pissaro [sic] (C.), Roqueplan (C.), Rousseau (T.-H.), Tassaert (O.), (Vernet H.), etc., Aquarelles, Pastels, Dessins, Miniatures par Cassatt (Mary), Daumier (H.), Forain (J.-L.), Gavarni, Guérin (P.), Hervier, Millet (J.-F.), Monnier (H.), Raffet. Œuvres Importantes d’Eugène Lami, Pastels et Gouache, par Degas, Composant la Collection de Feu M. Alexis Rouart (Paris: Hôtel Drouot, May 9, 1911), 51, (repro.), as L’Atelier de la modiste.

“À Travers Paris,” Le Figaro 57, no. 126 (May 6, 1911): 1.

“Art et Curiosité,” Le Journal, no. 6800 (May 10, 1911): 2, as L’Atelier de la Modiste.

“La Curiosité,” Excelsior, no. 176 (May 10, 1911): 4, as L’Atelier de la Modisté.

“Les Grandes Ventes,” Le Figaro 57, no. 130 (May 10, 1911): 5, as L’Atelier de la Modiste.

L. P., “À Travers la Curiosité,” Le Gil Blas 33, no. 12506 (May 11, 1911): 2, as L’Atelier de la Modiste.

“Revue des Ventes: Collection Alexis Rouart; 4e Vente faite salle 6, les 8, 9, 10 mai, par M. Baudoin et MM. Chaine et Simonson et Durand-Ruel,” Gazette de l’Hôtel Drouot 20, no. 54 (May 11, 1911): unpaginated, as L’Atelier de la modiste.

“Mouvement des arts,” La Chronique des arts et de la curiosité, no. 20 (May 20, 1911): 157, as L’Atelier de la Modiste.

Paul A. Lemoisne, Degas (Paris: Librairie Centrale Des Beaux-Arts, [1911?]), 98, 114, (repro.), as Les Modistes.

“16,400 For Degas Pastel: Another by the Same Master Brings $10,020 at the Rouart Sale,” New York Times 62, no. 20,051 (December 17, 1912): 4, as At the Milliners.

Max Goth, “Edgar Degas,” Les Hommes du jour 5, no. 257 (December 21, 1912): unpaginated.

Loan Exhibition of Masterpieces by Old and Modern Painters, exh. cat. (New York: Knoedler, 1915), 20, as The Milliners.

“Exhibition for Suffrage Cause,” New York Times 64, no. 20,899 (April 4, 1915): 14, as The Milliners.

“Loan Exhibition in Aid of Suffrage,” The Sun (New York) 82, no. 218 (April 6, 1915): 7.

“Mrs. Havemeyer Praises Woman’s Art at Exhibit for Suffragist Fund,” The Sun (New York) 82, no. 219 (April 7, 1915): 11, as The Milliner’s.

“Mrs. Havemeyer Talks of Artists,” New York Tribune 74, no. 24,979 (April 7, 1915): 11.

Paul Lafond, Degas (Paris: H. Floury, 1918), 1:11, 2:46, (repro.), as Les modistes.

Julius Meier-Graefe, Degas, trans. J[ohn] Holroyd-Reece (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1923), (repro.), as L’Atelier des Modistes.

Ambroise Vollard, Degas (1834–1917) (Paris: Les Éditions G. Crés et Cie, 1924), unpaginated, (repro.), as L’atelier de la modiste.

Louisine W. Havemeyer, “Mary Cassatt,” Pennsylvania Museum Bulletin 22, no. 113 (1927): 378.

Douglas Cooper, Pastels by Edgar Degas (New York: Macmillan, 1928), unpaginated, (repro.), as The Hat-Makers.

Arsène Alexandre, “La Collection Havemeyer, 2me Étude: Edgar Degas,” La Renaissance 12 (October 1929): 484–85, (repro.), as L’Atelier de la Modiste.

Possibly Exhibition of Paintings by the Master Impressionists, exh. cat. (New York: Durand-Ruel, 1929), unpaginated, as L’atelier de la modiste.

Important Paintings from the Havemeyer Estate, Part I: Oil Paintings (New York: American Art Association, Anderson Galleries, April 10, 1930).

H. O. Havemeyer Collection: Catalogue of Paintings, Prints, Sculpture and Objects of Art (Portland, ME: Southworth Press, 1931), 362–63, (repro.), as L’Atelier de la Modiste.

Degas, 1834–1917, exh. cat. (Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Museum of Art, 1936), 31, 89, (repro.), as The Millinery Shop.

Ambroise Vollard, Degas: An Intimate Portrait, trans. Randolph T. Weaver (New York: Crown Publishers, 1937), (repro.), as The Millinery Shop.

Camille Mauclair, Degas (New York: Hyperion Press, 1941), 116, 167, (repro.), as A Milliner’s Work-Room.

Paul A. Lemoisne, Degas et son œuvre (Paris: Arts et Métiers Graphiques, 1946), no. 681, pp. 1:123, 148; 2:382–83, (repro.); 4:37, 97, 123, 149, as Petites Modistes (L’Atelier de la Modiste).

John Rewald, The History of Impressionism (1946; repr., New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1973), 524.

A Loan Exhibition of Degas for the Benefit of the New York Infirmary, exh. cat. (New York: Wildenstein, 1949), 44, 59, (repro.), as The Millinery Shop.

Judith Kaye Reed, “Degas shown for Charity,” Arts Digest 23, no. 14 (April 15, 1949): 15, (repro.) as The Millinery Shop.

Degas: Loan Exhibition for the Benefit of The Citizens’ Committee for the Children of New York, Inc., exh. cat. (New York: Wildenstein, 1960), (repro.), as Petites Modistes.

John Canaday, “World of Degas,” New York Times 109, no. 37,325 (April 3, 1960): 38, as The Millinery Shop.

Louisine W. Havemeyer, Sixteen to Sixty: Memoirs of a Collector, ed. Susan Alyson Stein, 2nd ed. (1961; repr., New York: Ursus Press, 1993), 258, 338n382.

Jean Bouret, Degas (London: Thames and Hudson, 1965), 176, 178, (repro.), as Petites Modistes.

Franco Russoli and Fiorella Minervino, L’opera completa di Degas (Milan: Rizzoli Editore, 1970), no. 587, pp. 114, (repro.), as Due Modiste.

“One Hundred Years of Impressionism:” A Tribute to Durand-Ruel; A Loan Exhibition For the Benefit of the New York University Art Collection, exh. cat. (New York: Wildenstein, 1970), (repro.).

Hedy B. Landman, ed., European and American Art from Princeton Alumni Collections, exh. cat. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1972), 77, 89, (repro.), as L’Atelier de la modiste.

Theodore Reff, Degas: The Artist’s Mind (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1976), 322n92.

Donald Hoffman, “Intensity and Nuance: The Nelson’s new pastels,” Kansas City Star 100, no. 77 (December 16, 1979): 24–26, (repro.), as Little Milliners.

Donald Hoffman, “San Francisco Work of Art,” Kansas City Star 100, no. 89 (December 30, 1979): 2D.

Ronald Pickvance, Degas 1879: Paintings, Pastels, Drawings, Prints, and Sculpture from Around 100 Years Ago in the Context of His Earlier and Later Works, exh. cat. (Edinburgh: National Galleries of Scotland, 1979), 63.

Rosalind C. Truitt, “What’s new? To find out, take a break and visit the Nelson Gallery,” Kansas City Times 112, no. 267 (July 15, 1980): A-6, as L’Atelier de la Modiste.

Donald Hoffmann, “The Nelson gets first prize for new artworks,” Kansas City Star (July 20, 1980): 4E.

Ross E. Taggart and Laurence Sickman, Genre, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1983), 15, 27, (repro.), as The Shop of the Modiste.

Richard R. Brettell and Suzanne Folds McCullagh, Degas in The Art Institute of Chicago, exh. cat. (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 1984), 133.

Nancy Mowll Mathews, “Beauty, Truth, and the Artist’s Mirror: A Drypoint by Mary Cassatt,” Source: Notes in the History of Art 4, no. 2/3 (Winter/Spring 1985): 79n9.

Götz Adriani, Degas: Pastels, Oil Sketches, Drawings, trans. Alexander Lieven (New York: Abbeville Press, 1985), 377.

Jean Sutherland Boggs, “Degas at the Museum: Works in the Philadelphia Museum of Art and John G. Johnson Collection,” Philadelphia Museum of Art Bulletin 81, no. 346/347 (1985): 12, 41n24.

Richard Thomson, “Degas’s Nudes at the 1886 Impressionist Exhibition,” Gazette des Beaux-Arts 108, no. 128 (November 1986): 190, as Petites Modistes.

Charles S. Moffett, The New Painting: Impressionism 1874–1886, exh. cat. (Geneva: Richard Burton SA, 1986), 430–33, 437, 439, 443–44, (repro.), as Petites Modistes.

Frances Weitzenhoffer, The Havemeyers: Impressionism Comes to America (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1986), 224, (repro.).

Denys Sutton, “XI: A Continuing Romance,” Apollo 125, no. 300 (February 1987): 127, 131, as Petites Modistes.

“Museums to Sports, KC Has It All,” American Water Works Association Journal 79, no. 4 (April 1987): 133.

Donald Hoffmann, “Dressed for Success,” Kansas City Star 108, no. 26 (October 18, 1987): 1D, (repro.), as The Milliners.

Roger Ward, A Bountiful Decade: Selected Acquisitions 1977–1987, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1987), 116–17, (repro.), as The Milliners (L’Atelier de la Modiste).

Richard Kendall, Degas by Himself: Drawings, Prints, Paintings, Writings (London: Macdonald Orbis, 1987), 168, 323, (repro.), as The Hat Shop.

Eunice Lipton, “The Sadness of Artists: Degas by Himself,” New York Times 137, no. 47,569 (July 17, 1988): BR27, as The Hat Shop.

Michael Pantazzi, “Lettres De Degas à Thérèse Morbilli Conservées Au Musée Des Beaux-arts Du Canada,” RACAR: Revue D’art Canadienne / Canadian Art Review 15, no. 2 (1988): 132n94, as petites modistes.

Jean Sutherland Boggs et al., Degas, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1988), 259, 375–76, 385, 395–96, 397n1, 606, (repro.), as The Little Milliners and Les modistes.

Robert Gordon and Andrew Forge, Degas (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1988), 132, 275, (repro.), as Petites Modistes, L’Atelier de la Modiste (Milliner’s).

Eunice Lipton, Looking into Degas: Uneasy Images of Women and Modern Life (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988), 150, 153–54, 164, (repro.), as The Milliner’s Shop.

Marc S. Gerstein, Impressionism: Selections from Five American Museums, exh. cat. (New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1989), 21, 60–61, 150, (repro.), as Little Milliners.

Degas inédit: actes du colloque Degas, École du Louvre, Musée d’Orsay, 18–21 avril 1988 (Paris: La Documentation française, 1989), 344–45, 533, as Petites Modistes.

Christopher Gray, “Show and Sell: Early Art Dealers Built Themselves Picture Palaces,” Avenue 14, no. 7 (February 1990): 104, (repro.).

Toni Wood, “Modern viewers love impressionism,” Kansas City Star 110, no. 184 (April 15, 1990): H-4, as Little Milliners.

“At the Nelson,” Kanas City Star 110, no. 189 (April 20, 1990): C10.

Anne Distel, Impressionism: The First Collectors, trans. Barbara Perroud-Benson (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1990), 189–90, 271, (repro.), as The Little Milliners (Petites Modistes).

John Russell Taylor, Impressionist Dreams: The Artists and the World They Painted (Boston: Bulfinch Press, 1990), 131, 187, (repro.), as The Milliners.

Roger Ward, “Selected Acquisitions of European and American Paintings at The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, 1986–1990,” Burlington Magazine 133, no. 1055 (February 1991): 158.

Hollis Clayson, Painted Love: Prostitution in French Art of the Impressionist Era (1991; repr., Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2003), 129–31, (repro.), as The Millinery Shop.

Jean Sutherland Boggs and Anne Maheux, Degas Pastels (New York: George Braziller, 1992), 12, 98, 100–01, 156, 164, 182, (repro.), as The Little Milliners.

Alice Thorson, “The Nelson Celebrates its 60th: Museum built its reputation, collection virtually ‘from scratch’,” Kansas City Star 113, no. 304 (July 18, 1993): J5.

Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen et al., Splendid Legacy: The Havemeyer Collection, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1993), 47, 93, 95, 257, 333, 335, (repro.), as Little Milliners.

Roger Ward and Patricia J. Fidler, eds., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collection (New York: Hudson Hills Press, in association with Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1993), 14, 209, (repro.), as Little Milliners.

Roger Ward, “New at the Nelson: Degas Masterwork on Loan to Nelson-Atkins,” Newsletter (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (Summer 1995): 2, as Little Milliners.

Anthea Callen, The Spectacular Body: Science, Method and Meaning in the Work of Degas (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 33–34, (repro.), as Petites modistes.

“Music Teachers National Association National Convention, March 23–27, 1996, Kansas City, Missouri,” American Music Teacher 45, no. 4 (February–March 1996): 23.

Ruth Berson, The New Painting: Impressionism, 1874–1886: Documentation (San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1996), no. VIII-15, pp. 2:240, 258, (repro.), as Petites Modistes.

George T. M. Shackelford, Edgar Degas (New York: Abbeville Press, 1996), 82, 116, (repro.), as The Little Milliners.

Sylvie Patin and Gary Tinterow, La Collection Havemeyer: Quand l’Amérique découvrait l’Impressionnisme, exh. cat. (Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1997), 21, 71, 78n133, as Petites Modistes (l’atelier de la modiste).

Michael Howard, Encyclopedia of Impressionism (San Diego: Thunder Bay Press, 1997), 104, 252, 254, (repro.), as The Two Milliners.

Michael Howard, Impressionism (London: Carlton, 1997), 104, (repro.), as The Two Milliners.

Johann Georg Prinz von Hohenzollern and Peter-Klaus Schuster, eds., Manet bis Van Gogh: Hugo von Tschudi und der Kampf um die Moderne (Berlin: Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen, 1997), 120.

Newsletter (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (September 1998): 5, (repro.).

Griselda Pollock, Differencing the Canon: Feminist Desire and the Writing of Art’s Histories (London: Routledge, 1999), 222–23, 236, (repro.), as Little Milliners.

Ann Dumas and David A. Brenneman, Degas and America: The Early Collectors, exh. cat (Atlanta: High Museum of Art, 2000), 35.

Gabriele Crepaldi and Étienne Schelstraete, Les impressionnistes: Gustave Caillebotte, Mary Cassatt, Paul Cézanne, Edgar Degas (Paris: Gründ, 2001), 280, as Les Petites Modistes.

The Impressionists (London: Harper Collins, 2002), unpaginated, (repro.), as Milliners.

Linda Bolton, Degas (Edison: Chartwell books, 2003), 11, (repro.), as At the Milliners.

Gabriele Crepaldi and Tatjana Pauli, The Impressionists (London: Collins, 2003), 280, (repro.), as Les Petites Modistes.

Norio Shimada, The History of Impressionism / Inshōha bijutsukan (Tokyo: Shōgakukan, 2004), 225, (repro.).

Robyn Roslak, “Artisans, Consumers, and Corporeality in Signac’s Parisian Interiors,” Art History 29, no. 5 (November 2006): 865–66, (repro.), as Little Milliners.

Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 96–97, (repro.), as Little Milliners.

Werner Hofmann, Degas: A Dialogue of Difference (London: Thames and Hudson, 2007), 149–50, 154–56, 318, (repro.), as Two Milliners and At the Milliner’s.

Ruth E. Iskin, Modern Women and Parisian Consumer Culture in Impressionism Painting (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), x, 60, 70–72, 77, 82, 96–97, 106–07, 110–11, 237n40–41, 238n51, (repro.), as The Little Milliners.

Eik Kahng, ed., The Repeating Image: Multiples in French Painting from David to Matisse, exh. cat. (Baltimore: Walters Art Museum, 2007), 114, (repro.), as Little Milliners.

Pamela Todd, The Impressionists at Leisure (New York: Thames and Hudson, 2007), 121.

Deborah Emont Scott, ed., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collection, 7th ed. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2008), XIV, 122, (repro.), as Little Milliners.

Debra N. Mancoff, “Women’s Work,” Art Quarterly (Autumn 2011), 48–49, (repro.), as Little Milliners.

Charles Werner Haxthausen, The Two Art Histories: The Museum and the University (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2011), 123, 125.

Louis-Antoine Prat, Le dessin français au XIXe siècle (Paris: Louvre Editions, 2011), 534, as Les Petites Modistes.

Natalia Brodskai︠a, Edgar Degas (New York: Parkstone International, 2012), 116–17, (repro.), as The Little Milliners.

Gloria Groom, ed., Impressionism, Fashion, and Modernity, exh. cat. (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2012), 222, 225, (repro.), as Little Milliners.

Debra Mancoff, Fashion in Impressionist Paris (London: Merrell, 2012), 118, (repro.), as Little Milliners.

Xavier Rey, Degas: Capolavori dal Musée d’Orsay, exh. cat. (Milano: Skira, 2012), 39, as Picole modiste.

Christopher Lloyd, Edgar Degas: Drawings and Pastels (Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2014), 187, 204, (repro.), as The Milliner’s Shop.

Mary Morton and George T. M. Shackelford, Gustave Caillebotte: The Painter’s Eye, exh. cat. (Washington: National Gallery of Art, 2015), 254n27, as The Little Milliners.

Laura Anne Kalba, Color in the Age of Impressionism: Commerce, Technology, and Art (College Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2017), xi, 96–97, (repro.), as Little Milliners.

Simon Kelly and Esther Bell, Degas, Impressionism, and The Paris Millinery Trade, exh. cat. (San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 2017), 16, 23–24, 37, 275–76, 290, 295, (repro.), as Little Milliners (Petites modistes).

Theodore Reff, ed., The Letters of Edgar Degas (New York: The Wildenstein Plattner Institute, 2020), 1:400–01, 3:100, 352, as Petties modistes.

“Calendar,” KC Studio (Holiday 2022): 41, (repro.), as Junior Milliners (Petites Modistes).