![]()

Nicolas Poussin, The Triumph of Bacchus, 1635–36

| Artist | Nicolas Poussin, French, 1594–1665, active in Italy |

| Title | The Triumph of Bacchus |

| Object Date | 1635–36 |

| Alternate and Variant Titles | Le Triomphe de Bacchus |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (Unframed) | 50 3/8 x 59 3/4 in. (128 x 151.8 cm) |

| Credit Line | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 31-94 |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Ian Kennedy and Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “Nicolas Poussin, The Triumph of Bacchus, 1635–36,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.210.5407.

MLA:

Kennedy, Ian and Aimee Marcereau DeGalan. “Nicolas Poussin, The Triumph of Bacchus, 1635–36,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.210.5407.

Richelieu was no stranger to utilizing art in this capacity. In 1622, he had commissioned an allegorical cycle of paintings by Peter Paul Rubens (Flemish, 1622–25) celebrating the return of Queen Marie de Médicis to France following forced exile by Louis XIII, her young son.4The Rubens’s cycle was conceived not long after the queen mother’s return from exile with the expectation of asserting her influence in French policy. The cycle glorifies and vindicates her reign; see Goldfarb, Richelieu, 6. See also Ronald E. Miller and Robert E. Wolf, Heroic Deeds and Mystic Figures: A New Reading of Rubens’s Life of Maria de’Medici (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989). See also discussion of Poussin’s Galerie de Hommes Illustres in the Palais Cardinal by Sylvain Laveissière, “Counsel and Courage: The Galerie des Hommes Illustres in the Palais Cardinal, A Self-Portrait of Richelieu,” in Goldfarb, Richelieu, 64–71. She had become regent of France when the nearly nine-year-old Louis ascended the throne following the assassination of his father, Henry IV, in 1614. Mismanagement of the kingdom and endless political intrigues led young King Louis to take power in 1617 by exiling his mother (and her superintendent, Richelieu) and executing her followers.5Charles Tilly, “War making and state making as organized crime,” in Bringing the State Back In, ed. Peter B. Evans, Dietrich Rueschemeyer, and Theda Skocpol (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985). 174. Following their return in 1621, Richelieu became essential to Louis XIII as mediator between mother and son, and he rose to power quickly, becoming cardinal in 1622 and chief minister to Louis XIII in 1624, a position he retained until his death in 1642. The two mainstays of Richelieu’s role as chief minister were consolidating power in France and keeping the Hapsburg Dynasty, which ruled in Austria and Spain, in check.6Peter Zagorin, Rebels and Rulers: 1500–1660, vol. 2, Provincial Rebellion: Revolutionary Civil Wars, 1560–1660 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 9; and C. V. Wedgwood, The Thirty Years’ War (London: Methuen, 1981), 188. Richelieu was cunning and formidably intelligent. He deployed art to convey the glory of the state and the virtue of loyal service to the crown, relying on allegoric symbolism and historical parallels, either biblical or antique, to communicate these themes.7Goldfarb, Richelieu, 7. It is through this lens that one must consider the Bacchanal series Richelieu commissioned from Poussin for his Château de Richelieu in 1635–36.

The Triumph of Bacchus and The Triumph of Pan remained in the Richelieu family presumably until the second quarter of the 1700s, at which point they were sold and replaced with copies, now at the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Tours. When the originals appeared in Samuel Paris’s sale in London in 1741, they made an impression on English antiquarian George Vertue, who recorded in his notebook that year: “Brought over from Paris lately, 4 several [sic] pictures of Nicolas Poussin, of large historical subjects—two I think bought by Sir Robert Bouverie and two others I have seen with great pleasure—one The Triumph of Bacchus—many figures finely designed—men and women satyrssatyr: In Greek mythology, a woodland god depicted as a man with a goat’s ears, tail, legs, and horns., centaurscentaur: In Greek mythology, a race of half-human, half-horse creatures., etc, and all so well preserved, clear and strong in his best studied manner.”14George Vertue, “Vertue’s Note Book, B. 4,” in “Vertue Note Books: Volume III,” special issue, Walpole Society 22 (1933–1934): 105. Many commentators saw and praised the two paintings while they were in England, singling out in particular The Triumph of Bacchus as “among the finest work of Poussin.”15John Smith, A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch, Flemish, and French Painters, vol. 8, The Life and Works of Nicholas Poussin, Claude Lorraine, and Jean Baptist Greuze (London: Smith and Son, 1837), 110–11. Gustav Friedrich Waagen, who saw the Bacchus in the 1857 Manchester Art Treasures exhibition, when it belonged to the Earl of Carlisle, called it “the most important picture here by the greatest master of the French School, going on to describe it as “rich in composition, of graceful motives, characteristic in the forms, clear in the color, and carefully finished.”16[Gustav Friedrich] Waagen, The Manchester Exhibition; What to Observe: A Walk through the Art-Treasures Exhibition under the Guidance of Dr. Waagen: A Companion to the Official Catalogue (London: John Murray and W.H. Smith and Sons, 1857), 23.

Despite these accolades, the attribution to Poussin has wavered. Anthony Blunt was the first to query the attribution to Poussin in 1966, believing The Triumph of Bacchus to be cold and mechanical in handling, with none of the delicacy and sensitiveness of The Triumph of Pan, then in the Morrison collection.17Anthony Blunt, The Paintings of Nicolas Poussin: A Critical Catalogue (London: Phaidon, 1966), no. 137, pp. 95–98, 162. In support of this assessment, he cites doubts expressed by scholars in the French landscape exhibition of 1925 at the Petit Palais. Blunt believed the original to be lost, and that a copy was substituted when the pictures were sold from the Richelieu collection in the eighteenth century. Later, after seeing the Bacchus side by side with the National Gallery’s Pan in a 1981 exhibition at the National Gallery of Scotland in Edinburgh, Blunt accepted the Bacchus as the work of Poussin but suggested the presence of studio assistance in both paintings.18Anthony Blunt, “French Seventeenth-Century Painting: The Literature of the Last Ten Years,” The Burlington Magazine 124, no. 956 (November 1982): 706–07. The painting was, however, only attributed to Poussin by Wild (1980) and rejected by Mérot (1990). See Doris Wild, Nicolas Poussin (Zurich: Orell Füssli, 1980), 1:23, 62–63, 63n4, 64, 89, 183, 198, 200, 211, 215; 2:66–69, 208, 243, 262, 264, 317; and Alain Mérot, Nicolas Poussin (New York: Abbeville, 1990), 84, 87–88, 92, 275, 305, 319. While not doubting their autograph status, Pierre Rosenberg said the pair have often been respected rather than admired.19“Mais nous ne pensons pas que leur sensualité figée, alliée au plus parfait scrupule archéologique soit aujourd’hui parfaitement comprise (pour tout dire nous les admirons plus que nous les aimons)” (But we don’t think that their frozen sensuality, allied to the most perfect archaeological scrulple is perfectly understood today [to be honest, we admire them more than we love them]). Translation by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan. See Pierre Rosenberg, France in the Golden Age: Seventeenth-Century French Paintings in American Collections, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1982), 31–32, 308–09, 369, 378. However, other Poussin scholars, notably Jacques Thuillier, were not convinced; he maintained that the Nelson-Atkins Bacchus was “a good old copy” and that “only radiography and a comparative study of the fabric support would make it possible to remove the doubts.”20“Bonne copie ancienne,” “Seules la radiographie et l’étude comparative de la toile de support permettraient de lever les doutes.” Translation in text by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan. Thuillier, Nicolas Poussin, 254. Possibly on these grounds, both the Bacchus and the Pan were omitted from a 1994 Poussin exhibition in Paris in the belief that they did not serve the artist’s reputation.21See Pierre Rosenberg and Louis-Antoine Prat, Nicolas Poussin, 1594–1665, exh. cat. (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 1994).

Hilliard Goldfarb, in the catalogue for a 2002 exhibition on Richelieu in Montreal, expresses a more sympathetic view: “The Edinburgh catalogue (Poussin, Sacraments and Bacchanals, 1981) asserts that the painting has been harshly cleaned at some time in its history and contends that the drier and colder tonalities of certain areas may reflect this. In reality the composition’s palette is carefully orchestrated and enlivened by repeated highlights of red, lime green, honey yellow, coral and salmon pink. Most of the figures, especially the centaurs, the warm atmosphere, sky and landscape, and the handling of the vegetation argue forcefully for its autograph status. Awkward passages in the figures of the puttiputto (plural: putti): A representation of a naked child, especially a cherub or a cupid in Renaissance art. in the lower left, the musculature of the back of the river god do not appear to be of the standard of the others, but they have suffered from wear and losses.”22Hilliard T. Goldfarb, ed., Richelieu: Art and Power, exh. cat. (Montreal: Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, 2002), 2, 244–45, 292–95, 298. Although favorable, this verdict misses the fact that the picture is overall in very good condition (see the accompanying technical entry) and the quality of the execution consistent throughout. The handling is drier than in The Triumph of Pan, and the colors more muted, but this is in conformity with Poussin’s theory of “modes.” In a famous 1647 letter to his friend and patron Paul Fréart de Chantelou, Poussin outlines his idea to treat individual subjects differently, not only through a variety of expressions but also through different styles of painting: some subjects would be rendered more delicately, and others with more strength.23Poussin to Chantelou, March 24, 1647, in Charles Jouanny, ed., Correspondance de Nicolas Poussin (Paris: Jean Schemit, 1911), 350–52. Poussin’s handling in the Nelson-Atkins composition may be a function of the painting’s fidelity to archaeological sources, perhaps intended to be compatible with the works of Mantegna, with which it was destined to hang.24Poussin to Chantelou, March 24, 1647. For an excellent summary on Poussin’s theories of modes, see Helen Glanville, “Aspect and Prospect—Poussin’s Trumph of Silenus,” Artibus et Historiae 37, no. 74 (December 2016): 241–54. Compared to the more dynamic Triumph of Pan, the frieze-like composition may perhaps be said to approach the pedantic, but the painting is redeemed from academicism by the delicacy of the colors and the contained energy of the figures as they appear in procession parallel to the picture plane.

The archaeological precedent for The Triumph of Bacchus comes from ancient sarcophagi that depict Dionysius, the Greek equivalent to Bacchus. The centaurs and maenads (female followers of Bacchus) are common motifs in such reliefs, including, on occasion, the kind of dancing female figure in the background to the far right.25For example, Friedrich Matz, Die Dionysischen Sarkophage (Berlin: Mann, 1968), vol. 2, no. 117, pl. 53 (del Pozzo copy in the British Museum of a sarcophagus now in the Museo delle Terme, Rome). See also Matz, Die Dionysischen Sarkophage, vol. 1, no. 9, pl. 13 (sarcophagus in the Farnesina, Rome in 1556). The cupid holding the reins of the two centaurs, which in antiquity is usually positioned on the rump of a satyr, has been transposed in Poussin’s painting to the front of the triumphal car. His pose derives from a print by the Master of the Die (Italian, active ca. 1530–ca. 1560), after a drawing by Raphael (Italian, 1483–1520).26Adam von Bartsch and Suzanne Boorsch, The Illustrated Bartsch: Italian Masters of the Sixteenth Centuries, ed. Walter L. Strauss and Veronika Birke (New York: Abaris Books, 1982), 29:187. See a print owned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art here https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/396189. Many of the figures are crowned with ivy or vine leaves, both sacred to Bacchus: ivy since it is evergreen and a symbol of eternal life; the vine since Bacchus was the god of wine. This, too, is a motif evidenced in a multiplicity of sources, including another sixteenth-century print by the Master of the Die after Raphael, entitled Sacrifice to Priapus.27An example of this print featuring a statue of Priapus and decorated with garlands by Bacchantes and goat-footed maenads, also attended by satyrs, Bacchus, and a baby goat, can be found at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1985.1.436, <https://art.famsf.org/master-die/sacrifice-priapus-after-raphael-or-giulio-romano-19851436>. The putti in the foreground and on the chariot are crowed with laurel, a symbol of victory since the ancient games at Delphi.28The ancient Greeks first introduced the laurel crown as an honorary reward for victors in athletic, military, poetic, and musical contests. The winners of the Greek Pythian Games held in Delphi every four years in honor of Apollo received a wreath of bay laurel. See Statue of Hercules, [ᴄᴇ 100–199, Roman, marble with polychromy, 46 in. high, at the J. Paul Getty Museum, 73.AA.43.1, http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/objects/124355/unknown-maker-statue-of-hercules-roman-ad-100-200/?dz=0.5253,0.2649,1.57.

In the left background, the wreath on the spear is inscribed with the Bacchic cry, “Evoe, evoe,” while the adjacent Pan holds his shepherd’s crook and plays the pipes that he is said to have invented.29Many of the classical sources for Bacchus, including Pan and his pipes, can be found in a second-century Roman marble sarcophagus of the Marriage Procession of Bacchus and Ariadne, at the British Museum, 1805,0703.130, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/G_1805-0703-130. Hercules, carrying his club, holds in his other arm the tripod30A sheet of studies of antiquities by Poussin (today at the Getty Museum) includes a sketch of a Roman tripod acquired by Nicolas Claude Fabri de Pieresc in 1629. See David Jaffé, “Two Bronzes in Poussin’s ‘Studies of Antiquities,’” J. Paul Getty Museum Journal 17 (1989): 42–45. In the Pieresc tripod, the legs support a bowl; in the tripod in the Kansas City painting, the legs support a circular rim into which an urn is inserted. he stole from Apollo, who is in turn depicted driving his chariot in the sky.31The motif of Apollo riding in his chariot across the sky can be found in many ancient sources as well as near-contemporaneous print sources, including the Master of the Die (after Raphael), Apollo in His Horse-Drawn Chariot, 1530–60, engraving, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 49.97.327, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/396037. The leopard skin of the female rider of the rearmost centaur refers to Bacchus’s conquest of India, in which his chariot was drawn by leopards—a motif traditionally ascribed to a literary source, Lucian’s Dionysus.32See Lucian, of Samosata, ed. and trans. A. M. Harmon, K. Kilburn, and M. D. Macleod (New York: The Macmillan Co., 1913). See also Anthony Blunt, Nicolas Poussin: The A. W. Mellon Lectures in the Fine Arts, 1958, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.: Text (London: Phaidon, 1967), 1:137. To the far right, the maenad’s thyrsus (staff), common in Bacchic rites, is decorated with a pine cone and a serpent, both fertility symbols associated with Bacchus.33A thyrsus is a wand or staff of giant fennel covered with ivy vines and leaves, often topped with a pine cone, and carried during Hellenic festivals and religious ceremonies. See the ancient Greek sculpture of the Braschi Antinous, 138 ᴄᴇ, marble, Vatican Museums, Rome. The thyrsus is typically associated with the Greek god Dionysus or his Roman counterpart, Bacchus. See William Smith, William Wayte, and G. E. Marindin, eds., Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (London, J. Murray, 1890), s.v. “thrysus,” http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.04.0063:entry=thyrsus-cn&highlight=thyrsus, accessed September 13, 2021. The river god in the foreground, representing the river Indus, is another reference to Bacchus’s Indian expedition, and the palm, another triumphal symbol. The overturned jar once contained wine.

The pose of Bacchus himself also has an antique source; it is taken from an ancient painting (now lost) copied in a drawing for Cassiano dal Pozzo’s Paper Museum, possibly by Pietro Santi Bartoli (Italian, 1615–1700).34Blunt, Nicolas Poussin: The A. W. Mellon Lectures in the Fine Arts, 1958, 1:232; Francesco Solinas, Arte e Scienza nella Roma Barocca: Le collezione di Cassiano dal Pozzo, exh. cat. (Rome: Palazzo Barberini, 2000). The painting is now lost, but according to Bellori was discovered near the Theater of Marcellus. Giovanni Pietro Bellori engraved it in his Fragmenta Vestigii Veteris Romae, ex lapidibus Farnesianis, published in 1673. See Giovanni Pietro Bellori, Fragmenta Vestigii Veteris Romae, ex lapidibus Farnesianis (Rome: Ioannis Iacobi de Rubeis, 1673), 1. The subject of the lost painting is a triumph, possibly of the Goddess Roma, who is seated in the same pose as Poussin’s Bacchus, although she is clad in drapery and wearing a helmet. Other motifs in The Triumph of Bacchus lack an antique precedent: the serpentine trumpet behind the satyrs is more closely related to an instrument invented around 1600. Likewise, the triumphal carriage of Bacchus is unlike the chariots in ancient reliefs and closer to a Renaissance pattern like the “floats” in the illustrations to Onofrio Panvinio, Fastorum Libri V (Five Books on the Fasti), published in Venice in 1558.35Onofrio Panvinio, Fastorum Libri V a Romulo Rege usque ad Imp. Caesarem Carolum V . . . Eiusdem in Fastorum Libros Commentarii (Venice, 1558), 453–62. See Mary Beard, The Roman Triumph (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2007). The wheels resemble those in a Poussin drawing in a private collection made after a print by Antonio Fantuzzi (Italian, active 1537–50), after a battle scene by Giulio Romano (Italian, probably 1499–1546).36Pierre Rosenberg and Louis-Antoine Prat, Nicolas Poussin: 1594–1665; Catalogue raisonné des dessins (Milan: Leonardo, 1994), no. 185, 1:352. Similar wheels appear in a print by the Master of the Die after Giulio Romano, Cybele on Her Chariot (Bartsch, The Illustrated Bartsch, nos. 18-II, p. 29:175. A study of a chariot similar to that in the Poussin by Jacques Louis David was publishe in Pierre Rosenberg and B. Peronnet, “Un album inédit de David,” Revue de L’Art 142, no. 4 (2003): 45–83. Since the chariot is not of antique design, it is likely that the drawing, which dates from the late 1770s, was made either after the original painting, which was then in England, or after a copy available in France.

Robin’s topical and political explanation is perhaps the most convincing so far, given the character, status, and ambition of Richelieu himself. However, it still does not quite explain why Bacchus in particular should have been chosen as the triumphal protagonist, unless Richelieu merely wanted to follow the celebrated precedent of the Ferrara bacchanals by Titian (Venetian, ca. 1488–1576) then in Rome.49The paintings, which were made for Alfonso I d’Este, Duke of Ferrara, are: Titian, Bacchus and Ariadne, 1522–23, oil on canvas (applied onto conservation board 1968), 69.5 x 75 in (176.5 x 191 cm), National Gallery, London; The Bacchanal of the Andrians, 1523–26, oil on canvas, 69 x 76 in (175 x 193 cm), Museo del Prado, Madrid; The Worship of Venus, 1518–19, oil on canvas, 68 x 69 in (172 x 175 cm), Museo del Prado, Madrid. Be that as it may, any such interpretive meaning seems to have been overlooked by the time Vignier published his account of the château in 1676.50Wine, The Seventeenth Century French Paintings, 361. By then, the primacy of the Bacchus theme had been reinforced by statues of the god all over the grounds, including one in a courtyard placed above a bust of Marcus Tullius Cicero. In relation to The Triumph of Pan, Vignier suggested a moralizing dialectic of the effects of drunkenness, not unexpected in view of the moral subject matter of some of the Mantuan pictures, including Mantegna’s Minerva Expelling the Vices from the Garden of Virtue and Perugino’s Combat of Love and Chastity.51Vignier, Le Chateau de Richelieu ou l’histoire des dieux et des herros de l’antiquité avec des réfléxions morales par M. Vignier (Saumur, France: Isaac et Henry Desbordes, 1676), 162–63.

Since the completion of the bulk of this essay, new (and forthcoming) scholarship and technical study have combined knowledge of the ideas behind Poussin’s paintings, many of which are rooted in an understanding of classical texts and contemporary mythologies, and a more nuanced awareness of his technical process.52Chief among these scholars are Helen Glanville, whose forthcoming exploration of the syncretic/religious interpretation of Bacchus, grounded by a solid technical understanding of the artist’s process, promises to forge new ground. Glanville has contributed many recent studies on Poussin’s bacchanales that illuminate the course of her study to merge these two disciplines. See especially Glanville, “Aspect and Prospect—Poussin’s Triumph of Silenus,” Artibus et Historiae 37, no. 74 (2016): 241–54. A new publication and exhibition at the National Gallery, London, and the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, are also being realized around the idea of how Poussin’s understanding of ancient sculptures and Renaissance paintings of figures engaged in dance, which he encountered in Rome, helped him confront the problem of the body’s expressive potential in his paintings. See Emily A. Beeny and Francesca Whitlum-Cooper, Poussin and the Dance, exh. cat. (London: National Gallery Company, 2021). Much of this new scholarship merges the idea of Poussin as a painter-philosopher—whom his many biographers portray as someone who would lay down his brushes to walk on the Pincio while expounding his ideas about art and philosophy to a group of followers—with those of an exacting practitioner who altered his approach to compositions, “even the texture and consistency of his pigments . . . into elements that not only create the illusion of representing the world, but also communicated ideas and values in their own right.”53As discussed by Sheila McTighe in her article, “Poussin’s Practice: A New Plea for Poussin as a Painter,” Kermes 27, nos. 94–95 (April–September 2014): 11. For a particularly acute version of the painter-philosopher aspect of Poussin, see James Elmes, The Arts and Artists; or, Anecdotes and Relics of the Schools of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture (London: John Knight and Henry Lacey, 1825), 2:44–45. The thread-count studies of Poussin’s three bacchanals (see accompanying technical essay) carried out in 2014 by the Nelson-Atkins team and academic researchers Robert Erdmann and C. Richard Johnson of the Thread Count Automation Project, has also shed fundamental new light on the technical foundation of these paintings.54See Twilley, Myers, and Schafer, “Poussin’s Materials and Techniques,” 71–83. See also Robert G. Erdmann et al., “Reuniting Poussin’s Bacchanals Painted for Cardinal Richelieu through Quantitative Canvas Weave Analysis,” AIC Paintings Specialty Group: Postprints 26; Papers Presented at the 41st Annual Meeting, Indianapolis (Washington, DC: American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works, 2013), 155–72. Historically, there has been a level of skepticism or wholesale dismissal of technical studies on the grounds that they, in Pierre Rosenberg’s words, propose to “supplant the art historian whose major attribute . . . is his ‘eye’” with a study that aims to assert what is true through science.55See Pierre Rosenberg, “On the Developments in the History of Art,&rduo; Kermes 27, nos. 94–95 (April–September 2014): 7. However, after much consideration, Rosenberg concludes, these studies, performed in concert with curators, conservators, and scientists, provide a number of answers to questions that have long been issues of debate. It is on these collective grounds that Kansas City’s Triumph of Bacchus by Nicolas Poussin firmly stands.

Notes

-

“Hò pregato Monsige il Vescovo d’Albis di portare a Vra Emza due quadri dè Baccanali, che il Poesino Pittore hà già forniti conforme al desiderio, et intentione di lei. Quà sono stati veduti con molto applauso e se saranno approvati dal giuditio anche di essa, io ascriverò a mia singolar fortuna havere impiegata non inutilmte la mia assistenza, come mi glorierò sempre di qual si voglia altra occasione haverò di poterla servire.” Quoted by René Pintard, “Rencontres avec Poussin,” Poussin Colloque 1958 (Paris 1960), 1:33n7. De Daillon, son of the Count (later Duke) du Lude, left Rome for his diocese at the end of May (Pintard, “Rencontres avec Poussin,” 32).

-

“Monseigneur/Après avoir pris congé de V. E. dans Amiens, je m’en alloy au Lude, ou iay esté dans le lit six sepmaines, tourmanté de la plus grande incommodité de genouil qu’homme eut jamais, aussi tot que ma santé ma permis de me mettre en chemin pour Alby, ie lay faict, et pour satisfaire au Commandement que V. E. me fit d’apporter icy les deux tableaux du poussin, iy suis venu passer, ie les ay veus avec ceux de Monsieur de Mantoue, lesquels quoy que bons n’approchent point de la beauté, et de la perfection des deux que iay apportés. Cela n’empeschera pas qu’ensemble ils ne rendent le Cabinet de la Chambre du Roy parfaictement beau.” [“Monsignor / After taking leave of V.E. in Amiens, I went to Le Lude, where I was in bed for six weeks, tormented by the greatest discomfort in the knee that a man had ever had, as soon as my health allowed me to set out for Alby, I did, and to satisfy the Command that V.E. gave me to bring here the two pictures of Poussin, I came to pass there, I have seen them with those of Monsieur de Mantua, which are good [but] do not approach the beauty, and the perfection of the two which I have brought. This will not prevent them from making the Cabinet of the King’s Chamber perfectly beautiful. ” Translated by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan.] Archives des Affaires Etrangères, Paris, fonds français, 826 84, fol. 88, as cited in Jacques Thuillier, Nicolas Poussin (Paris: Flammarion, 1994), 155.

-

This is the premise upon which the exhibition by Hilliard T. Goldfarb is based. See Goldfarb, ed., Richelieu: Art and Power, exh. cat. (Montreal: Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, 2002).

-

The Rubens’s cycle was conceived not long after the queen mother’s return from exile with the expectation of asserting her influence in French policy. The cycle glorifies and vindicates her reign; see Goldfarb, Richelieu, 6. See also Ronald E. Miller and Robert E. Wolf, Heroic Deeds and Mystic Figures: A New Reading of Rubens’s Life of Maria de’Medici (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989). See also discussion of Poussin’s Galerie de Hommes Illustres in the Palais Cardinal by Sylvain Laveissière, “Counsel and Courage: The Galerie des Hommes Illustres in the Palais Cardinal, A Self-Portrait of Richelieu,” in Goldfarb, Richelieu, 64–71.

-

Charles Tilly, “War making and state making as organized crime,” in Bringing the State Back In, ed. Peter B. Evans, Dietrich Rueschemeyer, and Theda Skocpol (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985). 174.

-

Peter Zagorin, Rebels and Rulers: 1500–1660, vol. 2, Provincial Rebellion: Revolutionary Civil Wars, 1560–1660 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 9; and C. V. Wedgwood, The Thirty Years’ War (London: Methuen, 1981), 188.

-

Goldfarb, Richelieu, 7.

-

Benjamin Vignier, Le Château de Richelieu ou l’histoire des dieux et des herros de l’antiquité avec des réfléxions morales par M. Vignier (Saumur, France: Isaac et Henry Desbordes, 1676), 162–63.

-

For an in-depth treatment of the paintings in Richelieu’s Cabinet, see D. Bastet, “Études iconographique des ‘Bacchanales Richelieu’ de Nicolas Poussin,” in Studiolo: Revue d’histoire de l’art de l’Académie de France à Rome 4 (2006), 167–86.

-

A rough sketch plan by Léon Dufourny of 1800, published by John Schloder, shows how each of the paintings was sited at the time of Vignier’s description. See Humphrey Wine, The Seventeenth Century French Paintings (London: National Gallery, 2001), 360.

-

For an overview of the National Gallery, Silenus’s detractors, and those who accepted the painting, as well as recent analysis that led to its acceptance, see Francesca Whitlum-Cooper, “Poussin’s ‘Triumph of Silenus’ Rediscovered,” Burlington Magazine 163, no. 1418 (May 2021): 408–15. For the technical thread-count study that laid the groundwork for such a reassessment of Silenus, see Mary Schafer and John Twilley’s accompanying technical entry.

-

As former National Gallery, London, curator Humphrey Wine points out, the Cabinet du Roi may not originally have been intended to look exactly like this. See Wine, The Seventeenth Century French Paintings, 360.

-

Pierre Rosenberg, “Les Bacchanales Richelieu: ce que l’on sait et ce que l’on ne sait pas (encore),” in Richelieu à Richelieu: Architecture et Décors d’un Château Disparu, ed. Stijn Alsteens et al., exh. cat. (Milan: Silvana, 2011), 129–35.

-

George Vertue, “Vertue’s Note Book, B. 4,” in “Vertue Note Books: Volume III,” special issue, Walpole Society 22 (1933–1934): 105.

-

John Smith, A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch, Flemish, and French Painters, vol. 8, The Life and Works of Nicholas Poussin, Claude Lorraine, and Jean Baptist Greuze (London: Smith and Son, 1837), 110–11.

-

[Gustav Friedrich] Waagen, The Manchester Exhibition; What to Observe: A Walk through the Art-Treasures Exhibition under the Guidance of Dr. Waagen: A Companion to the Official Catalogue (London: John Murray and W.H. Smith and Sons, 1857), 23.

-

Anthony Blunt, The Paintings of Nicolas Poussin: A Critical Catalogue (London: Phaidon, 1966), no. 137, pp. 95–98, 162.

-

Anthony Blunt, “French Seventeenth-Century Painting: The Literature of the Last Ten Years,” Burlington Magazine 124, no. 956 (November 1982): 706–07. The painting was, however, only attributed to Poussin by Wild (1980) and rejected by Mérot (1990). See Doris Wild, Nicolas Poussin (Zurich: Orell Füssli, 1980), 1:23, 62–63, 63n4, 64, 89, 183, 198, 200, 211, 215; 2:66–69, 208, 243, 262, 264, 317; and Alain Mérot, Nicolas Poussin (New York: Abbeville, 1990), 84, 87–88, 92, 275, 305, 319.

-

“Mais nous ne pensons pas que leur sensualité figée, alliée au plus parfait scrupule archéologique soit aujourd’hui parfaitement comprise (pour tout dire nous les admirons plus que nous les aimons)” (But we don’t think that their frozen sensuality, allied to the most perfect archaeological scrulple is perfectly understood today [to be honest, we admire them more than we love them]). Translation by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan. See Pierre Rosenberg, France in the Golden Age: Seventeenth-Century French Paintings in American Collections, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1982), 31–32, 308–09, 369, 378.

-

“Bonne copie ancienne,” “Seules la radiographie et l’étude comparative de la toile de support permettraient de lever les doutes.” Translation in text by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan. Thuillier, Nicolas Poussin, 254.

-

See Pierre Rosenberg and Louis-Antoine Prat, Nicolas Poussin, 1594–1665, exh. cat. (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 1994).

-

Hilliard T. Goldfarb, ed., Richelieu: Art and Power, exh. cat. (Montreal: Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, 2002), 2, 244–45, 292–95, 298.

-

Poussin to Chantelou, March 24, 1647, in Charles Jouanny, ed., Correspondance de Nicolas Poussin (Paris: Jean Schemit, 1911), 350–52.

-

Poussin to Chantelou, March 24, 1647. For an excellent summary on Poussin’s theories of modes, see Helen Glanville, “Aspect and Prospect—Poussin’s Trumph of Silenus,” Artibus et Historiae 37, no. 74 (December 2016): 241–54.

-

For example, Friedrich Matz, Die Dionysischen Sarkophage (Berlin: Mann, 1968), vol. 2, no. 117, pl. 53 (del Pozzo copy in the British Museum of a sarcophagus now in the Museo delle Terme, Rome). See also Matz, Die Dionysischen Sarkophage, vol. 1, no. 9, pl. 13 (sarcophagus in the Farnesina, Rome in 1556).

-

Adam von Bartsch and Suzanne Boorsch, The Illustrated Bartsch: Italian Masters of the Sixteenth Centuries, ed. Walter L. Strauss and Veronika Birke (New York: Abaris Books, 1982), 29:187. See a print owned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art here https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/ search/396189.

-

An example of this print featuring a statue of Priapus and decorated with garlands by Bacchantes and goat-footed maenads, also attended by satyrs, Bacchus, and a baby goat, can be found at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1985.1.436, https://art.famsf.org/master-die/sacrifice-priapus-after-raphael-or-giulio-romano-19851436.

-

The ancient Greeks first introduced the laurel crown as an honorary reward for victors in athletic, military, poetic, and musical contests. The winners of the Greek Pythian Games held in Delphi every four years in honor of Apollo received a wreath of bay laurel. See Statue of Hercules, ᴄᴇ 100–199, Roman, marble with polychromy, 46 in. high, at the J. Paul Getty Museum, 73.AA.43.1, http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/objects/124355/unknown-maker-statue-of-hercules-roman-ad-100-200/?dz=0.5253,0.2649,1.57.

-

Many of the classical sources for Bacchus, including Pan and his pipes, can be found in a second-century Roman marble sarcophagus of the Marriage Procession of Bacchus and Ariadne, at the British Museum, 1805,0703.130, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/G_1805-0703-130.

-

A sheet of studies of antiquities by Poussin (today at the Getty Museum) includes a sketch of a Roman tripod acquired by Nicolas Claude Fabri de Pieresc in 1629. See David Jaffé, “Two Bronzes in Poussin’s ‘Studies of Antiquities,’” J. Paul Getty Museum Journal 17 (1989): 42–45. In the Pieresc tripod, the legs support a bowl; in the tripod in the Kansas City painting, the legs support a circular rim into which an urn is inserted.

-

The motif of Apollo riding in his chariot across the sky can be found in many ancient sources as well as near-contemporaneous print sources, including the Master of the Die (after Raphael), Apollo in His Horse-Drawn Chariot, 1530–60, engraving, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 49.97.327, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/396037.

-

See Lucian, of Samosata, ed. and trans. A. M. Harmon, K. Kilburn, and M. D. Macleod (New York: The Macmillan Co., 1913). See also Anthony Blunt, Nicolas Poussin: The A. W. Mellon Lectures in the Fine Arts, 1958, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC: Text (London: Phaidon, 1967), 1:137.

-

A thyrsus is a wand or staff of giant fennel covered with ivy vines and leaves, often topped with a pine cone, and carried during Hellenic festivals and religious ceremonies. See the ancient Greek sculpture of the Braschi Antinous, 138 ᴄᴇ, marble, Vatican Museums, Rome. The thyrsus is typically associated with the Greek god Dionysus or his Roman counterpart, Bacchus. See William Smith, William Wayte, and G. E. Marindin, eds., Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (London, J. Murray, 1890), s.v. “thrysus,” http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.04.0063:entry=thyrsus-cn&highlight=thyrsus, accessed September 13, 2021.

-

Blunt, Nicolas Poussin: The A. W. Mellon Lectures in the Fine Arts, 1958, 1:232; Francesco Solinas, Arte e Scienza nella Roma Barocca: Le collezione di Cassiano dal Pozzo, exh. cat. (Rome: Palazzo Barberini, 2000). The painting is now lost, but according to Bellori was discovered near the Theater of Marcellus. Giovanni Pietro Bellori engraved it in his Fragmenta Vestigii Veteris Romae, ex lapidibus Farnesianis, published in 1673. See Giovanni Pietro Bellori, Fragmenta Vestigii Veteris Romae, ex lapidibus Farnesianis (Rome: Ioannis Iacobi de Rubeis, 1673), 1.

-

Onofrio Panvinio, Fastorum Libri V a Romulo Rege usque ad Imp. Caesarem Carolum V . . . Eiusdem in Fastorum Libros Commentarii (Venice, 1558), 453–62. See Mary Beard, The Roman Triumph (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2007).

-

Pierre Rosenberg and Louis-Antoine Prat, Nicolas Poussin: 1594–1665; Catalogue raisonné des dessins (Milan: Leonardo, 1994), no. 185, 1:352. Similar wheels appear in a print by the Master of the Die after Giulio Romano, Cybele in Her Chariot (Bartsch, The Illustrated Bartsch, no. 18-II, p. 29:175. A study of a chariot similar to that in the Poussin by Jacques Louis David was published in Pierre Rosenberg and B. Peronnet, “Un album inédit de David,” Revue de L’Art 142, no. 4 (2003): 45–83. Since the chariot is not of antique design, it is likely that the drawing, which dates from the late 1770s, was made either after the original painting, which was then in England, or after a copy available in France.

-

Rosenberg and Prat, Nicolas Poussin: 1594–1665, no. 83, pp. 1:148–51.

-

The verso of a drawing in the Uffizi related to the Triumph of Pan features studies of centaurs, one rearing up as in the painting but holding a banner, the other on its knees with a cupid on its back, following antique precedents. See Rosenberg and Prat, Nicolas Poussin: 1594–1665, 1:156–57, no. 86.

-

The chariot is again more authentically antique. As in the painting, it is drawn by cavorting satyrs, the one nearest the chariot carrying a female figure. The elephants and camels, later suppressed, survive in the background. A satyr and maenad, also eliminated from the paintings, appear to the rear of the chariot. To the far right, a bacchante anticipates the dancing female seen in the background of the painting, though she is more covered by drapery. In the foreground the river god, instead of in profile and with his back to us as later, faces outward. Otherwise the foreground is relatively bare, lacking the overturned jar and putto climbing out of the water.

-

A sheet of studies in the Hermitage again addresses the two satyrs, in this case near their final form. See Rosenberg and Prat, Nicolas Poussin: 1594–1665, no. 89, pp. 1:162–63. A related drawing in Bayonne shows maenads with a thyrsus and a satyr abducting a nymph, though the pose of the maenad differs from the picture. See Rosenberg and Prat, Nicolas Poussin: 1594–1665, no. 90, pp. 1:162–63. A fragment of a drawing in The Los Angeles County Museum of Art, joined to another fragment of a Holy Family, again shows a female figure riding a satyr. See Rosenberg and Prat, Nicolas Poussin: 1594–1665, no. 91, pp. 1:164–65.

-

It is not clear whether Poussin ever saw the Mantegnas from the studio of Isabella d’Este before they were sent from Mantua to France in 1624–29, but he would have been familiar enough with Mantegna’s style from prints by or after Mantegna. A pen and wash copy by Poussin after Mantegna’s Triumph of Caesar exists in a private collection in Paris; see Rosenberg and Prat, Nicolas Poussin: 1594–1665, no. 206, 1:402.

-

Wine, The Seventeenth Century French Paintings, 360–61.

-

Paola Santucci, Poussin: Tradizione Ermetica e Classicismo Gesuita (Salerno: Cooperativa, 1985), 27–30, 32, 132. See also Blaise de Vigénère, Les images, ou Tableaux de platte peinture de Philostrate Lemnien (Paris: Abel Langelier, 1597).

-

Charles Dempsey, “Poussin’s ‘Marine Venus’ at Philadelphia: A Re-Identification Accepted,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 28 (1965): 341.

-

Charles Dempsey, “The Classical Perception of Nature in Poussin’s Earlier Work,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 29 (1966): 243.

-

Malcolm Bull, “Poussin’s Bacchanals for Cardinal Richelieu,” Burlington Magazine 137, no. 1102 (January 1995): 5–6, 9–11.

-

Wine, The Seventeenth Century French Paintings, 361.

-

Delphine Robin, Étude iconographique des Bacchanales Richelieu de Nicolas Poussin (PhD diss., Université Paris-Sorbonne, Paris IV, 1998).

-

The paintings, which were made for Alfonso I d’Este, Duke of Ferrara, are: Titian, Bacchus and Ariadne, 1522–23, oil on canvas (applied onto conservation board 1968), 69.5 x 75 in (176.5 x 191 cm), National Gallery, London; The Bacchanal of the Andrians, 1523–26, oil on canvas, 69 x 76 in (175 x 193 cm), Museo del Prado, Madrid; The Worship of Venus, 1518–19, oil on canvas, 68 x 69 in (172 x 175 cm), Museo del Prado, Madrid.

-

Wine, The Seventeenth Century French Paintings, 361.

-

Vignier, Le Chateau de Richelieu ou l’histoire des dieux et des herros de l’antiquité avec des réfléxions morales par M. Vignier (Saumur, France: Isaac et Henry Desbordes, 1676), 162–63.

-

Chief among these scholars are Helen Glanville, whose forthcoming exploration of the syncretic/religious interpretation of Bacchus, grounded by a solid technical understanding of the artist’s process, promises to forge new ground. Glanville has contributed many recent studies on Poussin’s bacchanales that illuminate the course of her study to merge these two disciplines. See especially Glanville, “Aspect and Prospect—Poussin’s Triumph of Silenus,” Artibus et Historiae 37, no. 74 (2016): 241–54. A new publication and exhibition at the National Gallery, London, and the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, are also being realized around the idea of how Poussin’s understanding of ancient sculptures and Renaissance paintings of figures engaged in dance, which he encountered in Rome, helped him confront the problem of the body’s expressive potential in his paintings. See Emily A. Beeny and Francesca Whitlum-Cooper, Poussin and the Dance, exh. cat. (London: National Gallery Company, 2021).

-

As discussed by Sheila McTighe in her article, “Poussin’s Practice: A New Plea for Poussin as a Painter,” Kermes 27, nos. 94–95 (April–September 2014): 11. For a particularly acute version of the painter-philosopher aspect of Poussin, see James Elmes, The Arts and Artists; or, Anecdotes and Relics of the Schools of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture (London: John Knight and Henry Lacey, 1825), 2:44–45.

-

See Twilley, Myers, and Schafer, “Poussin’s Materials and Techniques,” 71–83. See also Robert G. Erdmann et al., “Reuniting Poussin’s Bacchanals Painted for Cardinal Richelieu through Quantitative Canvas Weave Analysis,” AIC Paintings Specialty Group: Postprints 26; Papers Presented at the 41st Annual Meeting, Indianapolis (Washington, DC: American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works, 2013): 155–72.

-

See Pierre Rosenberg, “On the Developments in the History of Art,” Kermes 27, nos. 94–95 (April–September 2014): 7.

-

Ian Kennedy, former Louis L. and Adelaide C. Ward Senior Curator of European Art, drafted the bulk of this essay during his tenure (2007–13) at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Research was updated and edited, with additional text and translations, by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan in 2021 in preparation for this catalogue. This essay is included with Kennedy’s permission.

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Mary Schafer and John Twilley, “Nicolas Poussin, The Triumph of Bacchus, 1635–36,” technical entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.210.2088.

MLA:

Schafer, Mary and John Twilley. “Nicolas Poussin, The Triumph of Bacchus, 1635–36,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.210.2088.

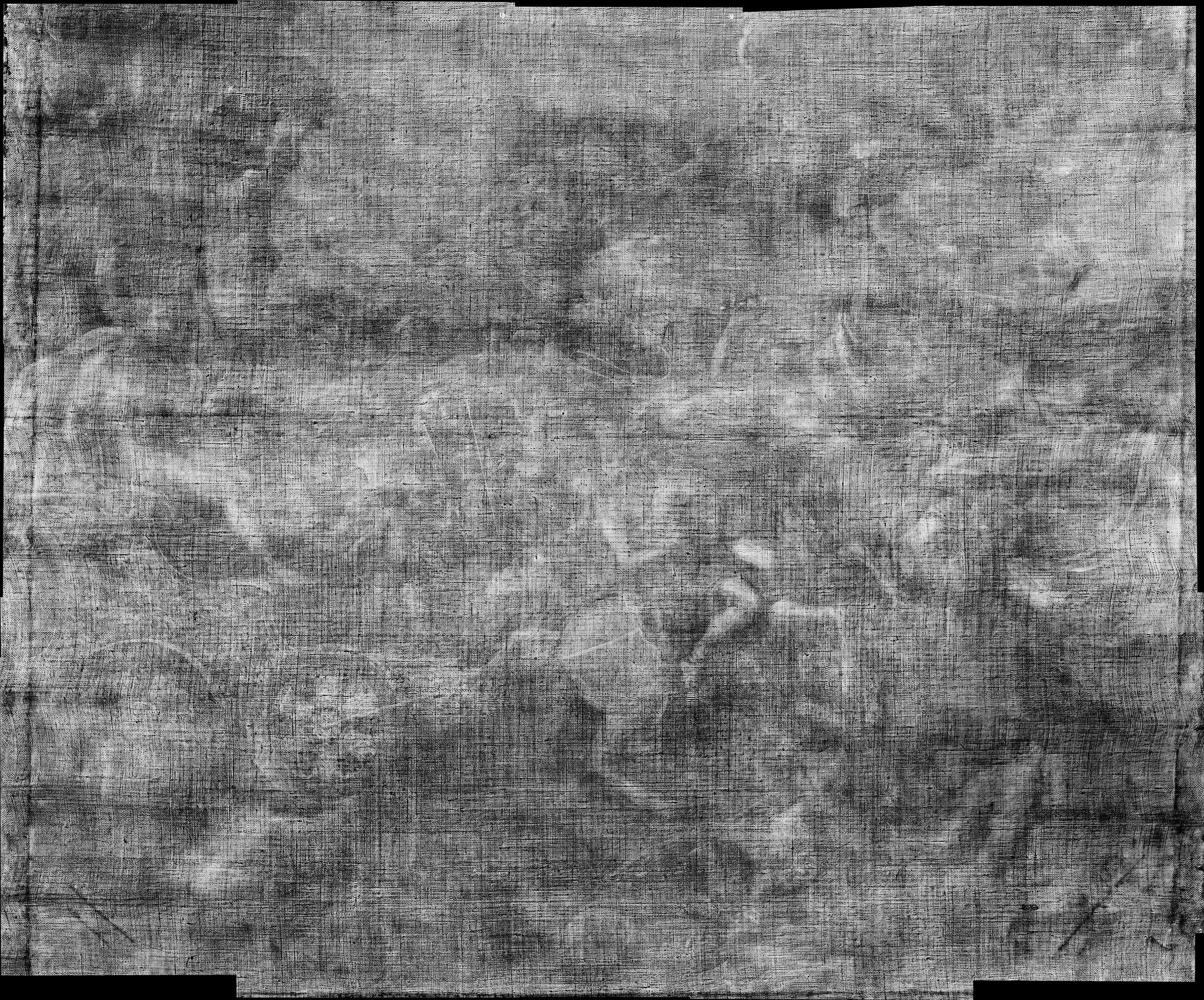

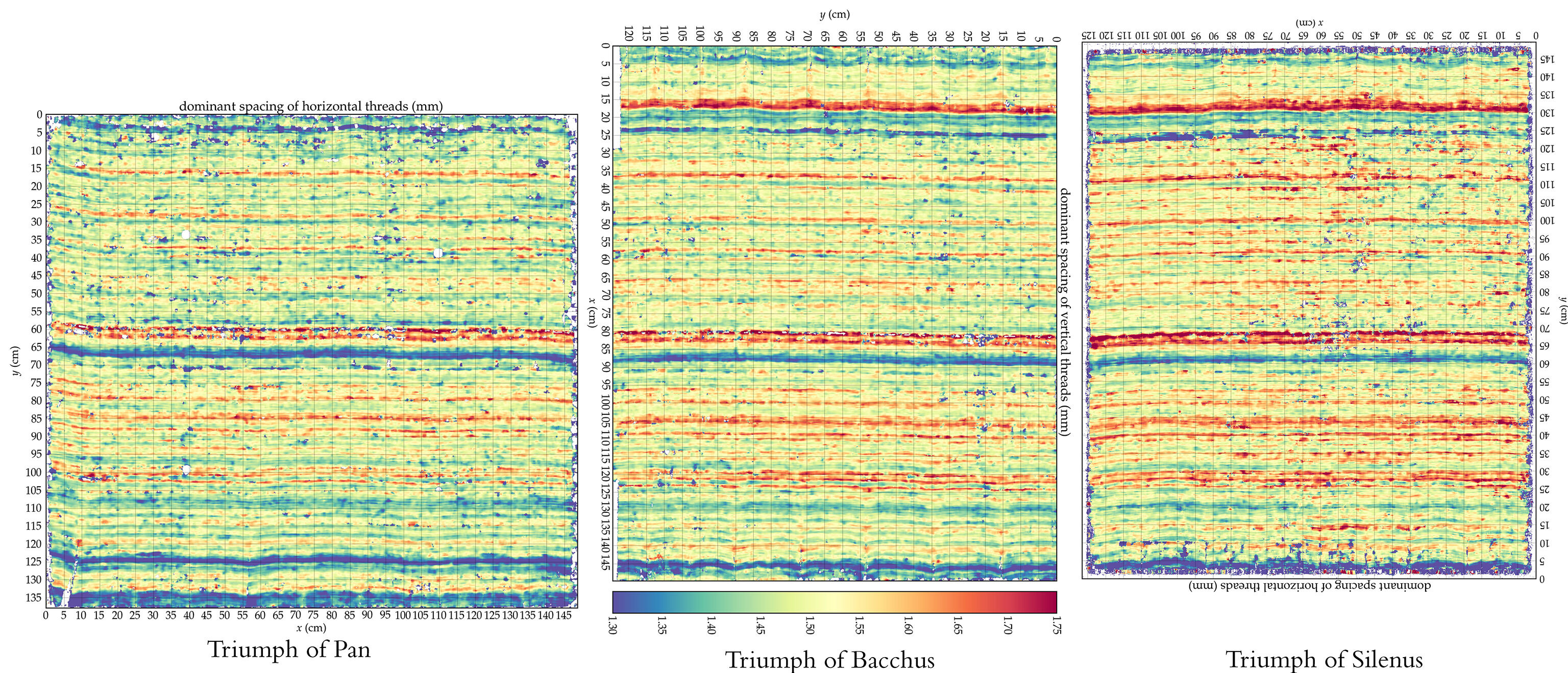

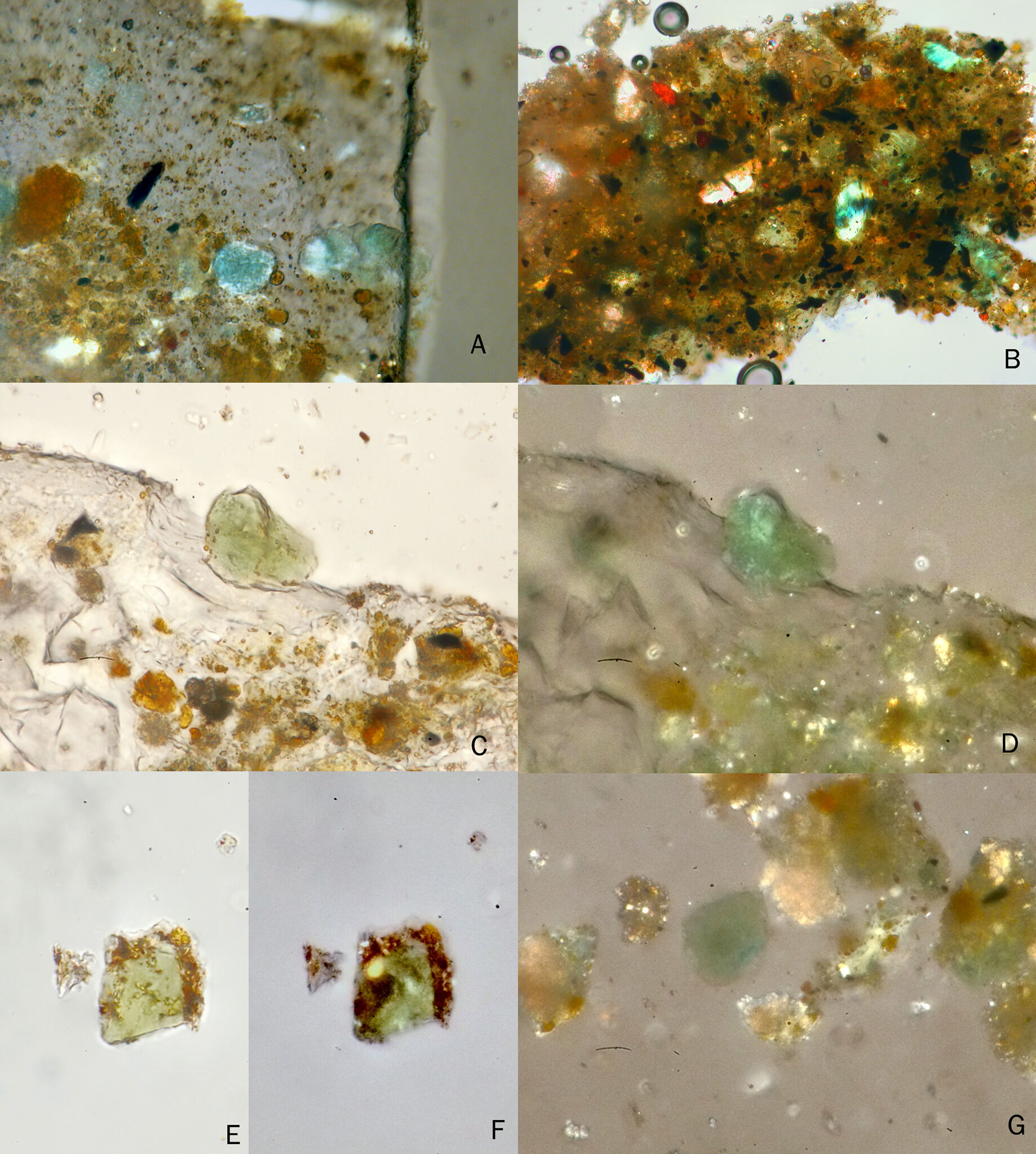

Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665) executed The Triumph of Bacchus between 1635–36 as part of a bacchanal-themed commission for Armand Jean du Plessis, Cardinal de Richelieu, that included The Triumph of Pan (1636) and The Triumph of Silenus (ca. 1637), both of which are in the collection of the National Gallery of Art, London (Figs. 1, 2). Following the success of the series, a number of high-quality contemporary copies were produced—at least seven painted copies of Bacchus are known—and, as with other Poussin paintings, the existence of copies led to a prolonged period of questioned authenticity. Uncertainty about the Nelson-Atkins painting was first raised by Paul Jamot in 1925: “It’s the execution here that fails. It is exact, correct, but of a sort of cold and dead perfection.”1Paul Jamot, “Sur quelques tableaux de Poussin à propos de l’exposition du paysage français,” Bulletin de la Société de l’histoire de l’art français (1925): 103. Translated from French by Nicole R. Myers, former associate curator, European paintings and sculpture, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Although the provenance history of Bacchus matches that of Pan until 1850, and the Nelson-Atkins painting was largely accepted as the original when the Richelieu series was reunited in 1981, some lingering doubts persisted in the literature. In 1994, Jacques Thuillier described Bacchus as a copy that “found defenders” and called for a scientific study to compare the series: “There is little chance that for these four works, painted over a short period of time and with the same destination, Poussin would have changed the type of canvas and preparation, or that his handling would have evolved much.“2Jacques Thuillier, “Poussin et la laboratoire,” Techné, no. 1 (1994): 18. Translation provided by Nicole R. Myers, former associate curator, European paintings and sculpture, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. The fourth painting to which Thuillier refers is Poussin’s Birth of Venus, sometimes titled Triumph of Neptune (1635 or 1634; Philadelphia Museum of Art, E1932-1-1). The thread count of its canvas is markedly different than that of the other three, so that higher-level comparison was not undertaken. Mark Tucker, Aronson Senior Conservator of Paintings and Vice Chair of Conservation, Philadelphia Museum of Art, email message with the author, 2015. The authors thank Tucker for providing his manual thread counts that established this difference. To answer many of the questions that Thuillier posed, a technical study of the Nelson-Atkins painting and a comparison of the Richelieu canvas supports were conducted in 2011.3The authors are indebted to Nicole R. Myers, former associate curator, European paintings and sculpture, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, for her curatorial contributions to the study.,4The scientific study of The Triumph of Bacchus was supported by an endowment from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation for conservation science at The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.,5Results from the technical study were disseminated in two prior publications. See John Twilley, Nicole Myers, and Mary Schafer, “Poussin’s Materials and Techniques for The Triumph of Bacchus at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art,” Kermes 27, nos. 94–95 (April/September 2014): 71–83. Robert Erdmann, C. Richard Johnson, Mary Schafer, John Twilley, Nicole Myers, and Travis Sawyer, “Reuniting Poussin’s Bacchanals Painted for Cardinal Richelieu through Quantitative Canvas Weave Analysis,” AIC Paintings Specialty Group: Postprints 26; Papers Presented at the 41st Annual Meeting, Indianapolis (Washington, DC: American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works, 2013): 155–72.

Examination has shown that Bacchus is well-preserved with no structural instability, but its appearance could be significantly improved with removal of deteriorated varnish residues, which are now over forty years old. A scientific study of the Bacchus palette was undertaken in anticipation of a conservation treatment that would require more information on the original materials and their alteration over time. The success of the canvas weave match in linking all three paintings provided the basis for the palette study and may contribute to solving an art historical mystery: Do variations in the artist’s pigment use and the subsequent alteration of pigments influence the perceptions that sharply divided art historical opinion about whether the three paintings shared a common origin?

Canvas Weave Comparisons of the Richelieu Bacchanals

Historically, canvas weaves have been compared either by manually counting the average number of threads per centimeter in the warp and weft directions with the aid of magnification and a ruler, or counting them from radiographsX-ray radiography (also referred to as x-radiography or radiography): Radiography is an examination tool analogous to the use of X-rays in medicine whereby denser components of a painted composition can be recorded as an inverted shadow image cast on film or a digital X-ray imaging plate from a source such as an X-ray tube. The method has been used for more than a century and is most effective with dense pigments incorporating metallic elements such as lead or zinc. It can reveal artist changes, underlying compositions, and information concerning the artwork’s construction and condition. The resulting image is called an x-radiograph or radiograph. It differs from the uses of X-ray spectrometry in being dependent on the density of the paint to absorb X-rays before they reach the film or image plate and being non-specific as to which elements are responsible for the resulting shadow image. in which the canvas weave is visible. The process was error-prone, somewhat subjective, and often too coarse for statistical measures of the quality of a “match” to have real meaning. More recently, automated methods applied to radiographs of paintings have greatly improved the accuracy of thread counts and led to new forms of comparison derived from distortions of the weave that are imposed during stretching the canvas or subsequent modifications in its mounting or format.

The need for a rigorous comparison of the canvases and the need to quantify the certainty of an outcome that proved surprising to some, by demonstrating that all three bacchanals of the Richelieu commission were derived from the same bolt of cloth and that the third original painting of the group was one that had long been regarded as a copy, led to important refinements for comparing their weaves and in the methods available to the field of art history for the study of other paintings.

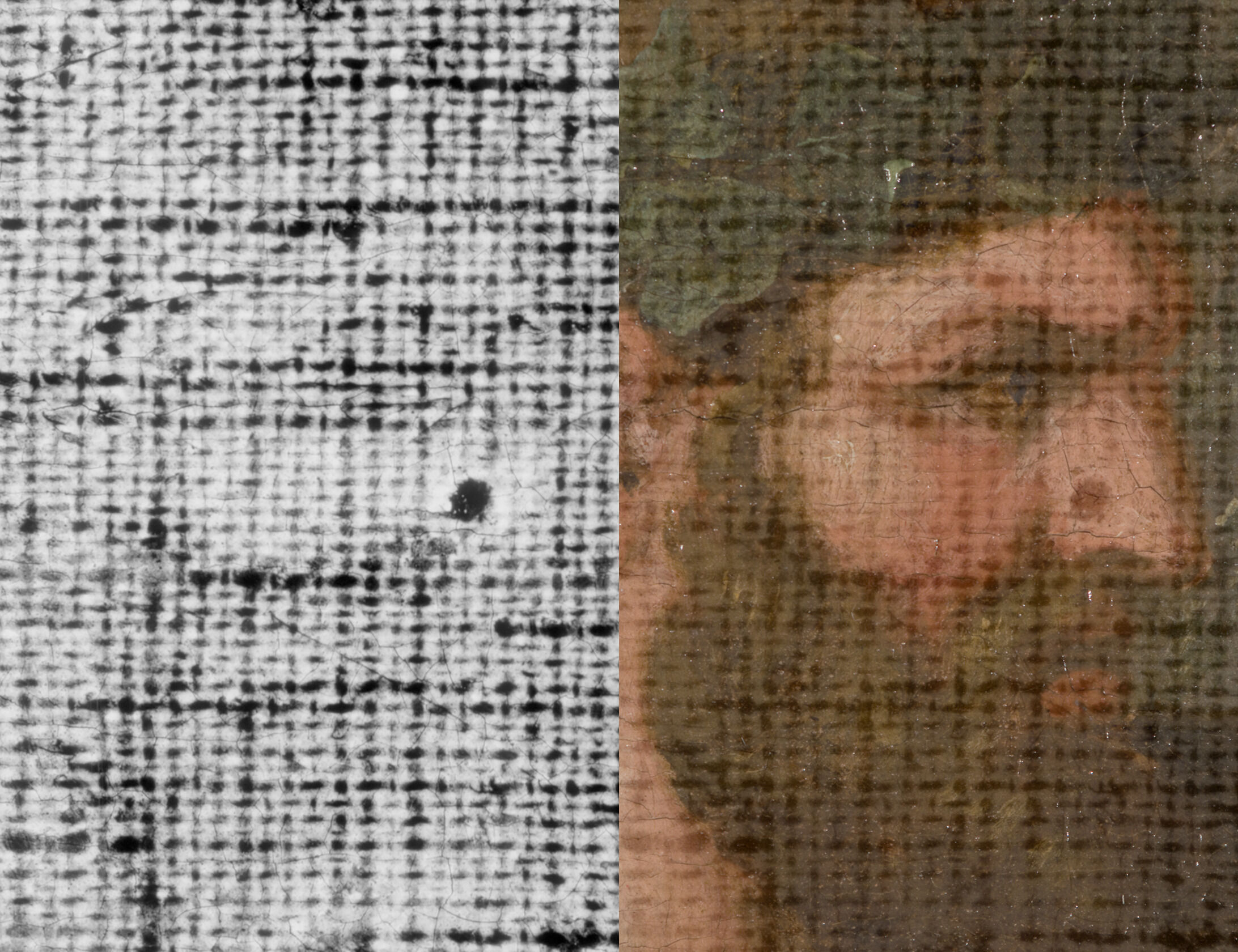

Strong cuspingcusping: A scalloped pattern along the canvas edges that relates to how the canvas was stretched. Primary cusping reveals where tacks secured the canvas to the support while the ground layer was applied. Secondary cusping can form when a pre-primed canvas is re-stretched by the artist prior to painting. along the right and left canvas edges of Bacchus and Pan, as revealed through the initial process, established a particularly close connection between these two paintings. However, the method required heavy intervention by the operator and was unable to deal with radiographic features that often interfered with the weave, including obscuring paint textures. It stopped short of being a thread-by-thread comparison and it lacked a means for human manual verification.

The development of an improved method, based on autocorrelation analysis and pattern-recognition algorithms, was prompted by the need to substantiate an outcome that ran counter to the widely-held opinion that Silenus was not the original version by Poussin. The result of doing this along five guide threads for the three paintings of the Richelieu commission demonstrated a single abrupt increase in the quality of the match at one, unique juxtaposition of the canvases.10To demonstrate that a comparable outcome could be obtained from a guided traverse along a single thread, the innovation of using a “guide thread” visible in the radiograph, along which the spacing of every crossing thread could be manually entered, was introduced. The resulting set of spacing measurements could then be shifted, thread by thread, away from the apparent best match in both directions, and the quality of match in the resulting trial alignments plotted. See Erdmann et al., “Reuniting Poussin’s Bacchanals Painted for Cardinal Richelieu through Quantitative Canvas Weave Analysis,” 155–72.

The challenge of making a full thread-by-thread demonstration of the match computationally feasible was subsequently taken up by Laurens van der Maaten under the direction of Robert Erdmann.11Van der Maaten employed a machine learning approach that made a full comparison of the canvases in both directions possible at the level of individual thread spacings. The twelve-thousand, manually-extracted, thread-crossing measurements along the guide threads used in validation of the previous match were used in training of the new algorithm. Incorporated into van der Maaten’s solution was a means for projecting the re-emergence points of individual threads that become locally obscured in the radiograph by heavy overlapping paint strokes, increasing the proportion of the canvas that could be included in difficult comparisons. This method eliminated reliance upon local averages of thread spacings and made full thread-by-thread comparisons possible. See L.J.P. van der Maaten and R.G. Erdmann, “Automatic thread-level canvas analysis,” IEEE Signal Processing Magazine 32, no. 4 (2015): 38–45. The results of this thrice-repeated match with increasingly sophisticated methods not only bolstered the case for a common origin of the three Poussin bacchanals, but also led to improvements in the methodology for other works.

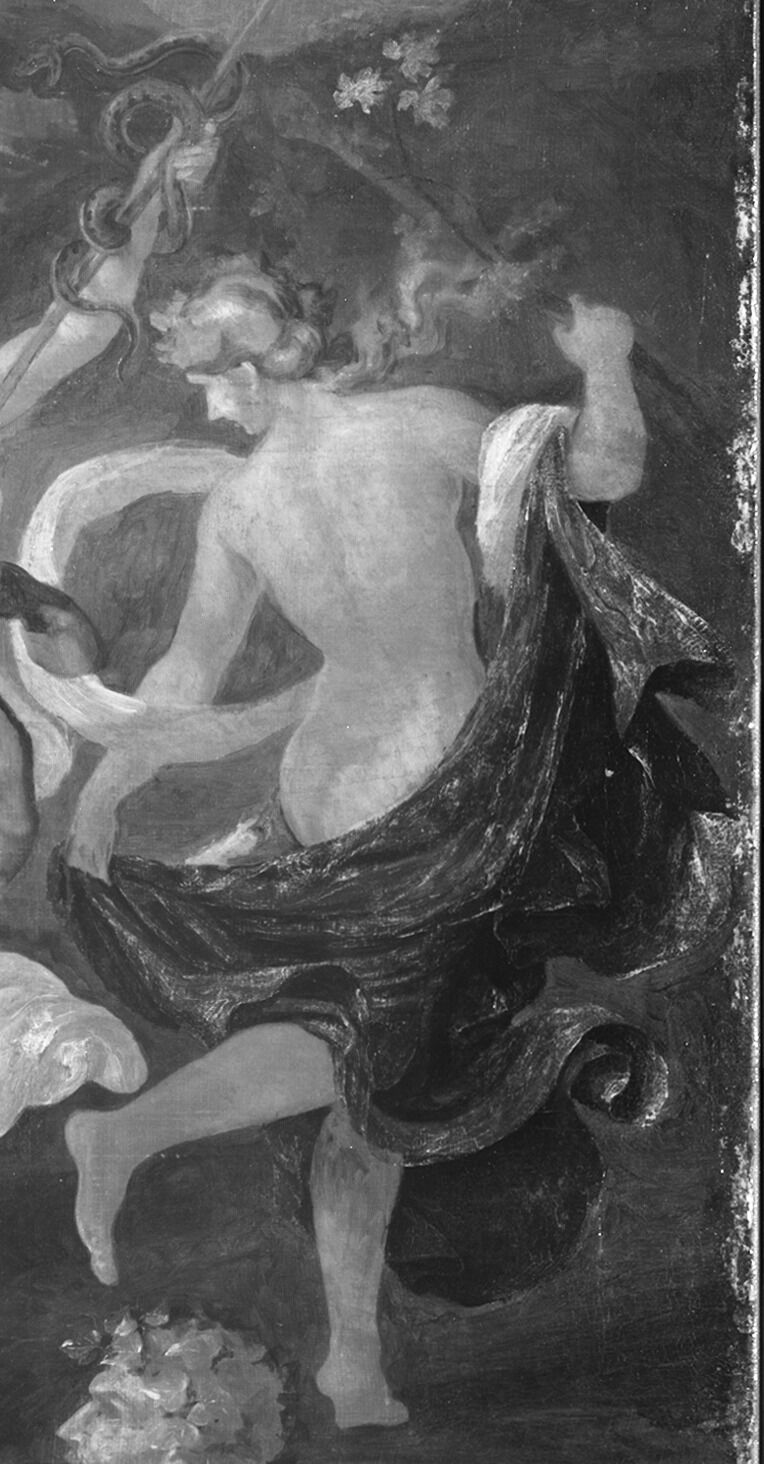

Overview of the Painting Construction of Bacchus

Poussin’s working method, as described by his biographers, was a painstaking process that involved a number of steps before paint was applied to canvas: quick sketches to develop the initial compositional concept; studies of illuminated wax models, often with additions of wet paper or fabric to simulate drapery; further sketching of live models; and pen and ink drawings.16See Anthony Blunt, Nicolas Poussin: The Andrew W. Mellon Lectures in Fine Arts, 1958 (London: Phaidon Press Ltd, 1967), 1:242–44. See also Diane DeGrazia and Marcia Steele, “The ‘Grande Machine,’” Cleveland Studies in the History of Art 4 (1999): 64–67. For the artist’s most complicated figural arrangements, like that of Bacchus, Antoine Le Blond de la Tour (1635–1706) described the artist’s use of a partially-enclosed box with a small aperture at the front that allowed Poussin to view the wax models on a gridded board in perspective scale, to explore the effects of light and shade, and to assess the overall composition.17DeGrazia and Steele, Cleveland Studies, 65–66.,18According to Joachim von Sandrart (1606–88), Poussin began using this method of placing the wax figures on a gridded board around 1630. Konrad Oberhuber et al., Poussin, the Early Years in Rome: The Origins of French Classicism, exh. cat. (New York: Hudson Hills, 1988), 208.

Fig. 9. On the left, radiograph detail of Triumph of Bacchus (1635–36); on the right, an overlay of the radiograph and normal illumination (desaturated) details, showing the position of the vanishing point at Hercules’ nose

Fig. 9. On the left, radiograph detail of Triumph of Bacchus (1635–36); on the right, an overlay of the radiograph and normal illumination (desaturated) details, showing the position of the vanishing point at Hercules’ nose

Fig. 10. Diagram of Triumph of Bacchus (1635–36), showing key orthogonals passing through the vanishing point

Fig. 10. Diagram of Triumph of Bacchus (1635–36), showing key orthogonals passing through the vanishing point

Fig. 14. Detail of Triumph of Bacchus (1635–36), showing finely painted brown lines near Cupid’s leg

Fig. 14. Detail of Triumph of Bacchus (1635–36), showing finely painted brown lines near Cupid’s leg

Fig. 15. Detail of the central trumpeter, Triumph of Bacchus (1635–36)

Fig. 15. Detail of the central trumpeter, Triumph of Bacchus (1635–36)

Fig. 16. Detail of the river god’s forearm, Triumph of Bacchus (1635–36). Finely painted strokes of pink highlight and define the musculature.

Fig. 16. Detail of the river god’s forearm, Triumph of Bacchus (1635–36). Finely painted strokes of pink highlight and define the musculature.

Fig. 17. Details of the leftmost bacchante’s face and upraised hand, Triumph of Bacchus (1635–36)

Fig. 17. Details of the leftmost bacchante’s face and upraised hand, Triumph of Bacchus (1635–36)

Fig. 18. Photomicrograph of green highlights on Hercules’ fingernails, Triumph of Bacchus (1635–36)

Fig. 18. Photomicrograph of green highlights on Hercules’ fingernails, Triumph of Bacchus (1635–36)

Fig. 19. Detail of the wet-into-wet paint strokes of the spotted animal pelt, Triumph of Bacchus (1635–36)

Fig. 19. Detail of the wet-into-wet paint strokes of the spotted animal pelt, Triumph of Bacchus (1635–36)

Fig. 20. Detail of the dryly painted, wet-over-dry brushwork of the centaur’s beard, Triumph of Bacchus (1635–36)

Fig. 20. Detail of the dryly painted, wet-over-dry brushwork of the centaur’s beard, Triumph of Bacchus (1635–36)

Fig. 21. Infrared reflectogram captured between 1.5-1.7 microns, of the rightmost bacchante showing the textures and opacity of the charcoal underlayer beneath the ultramarine blue robe. Her thighs are visible in silhouette through the robe layers, indicating that she was initially painted nude.

Fig. 21. Infrared reflectogram captured between 1.5-1.7 microns, of the rightmost bacchante showing the textures and opacity of the charcoal underlayer beneath the ultramarine blue robe. Her thighs are visible in silhouette through the robe layers, indicating that she was initially painted nude.

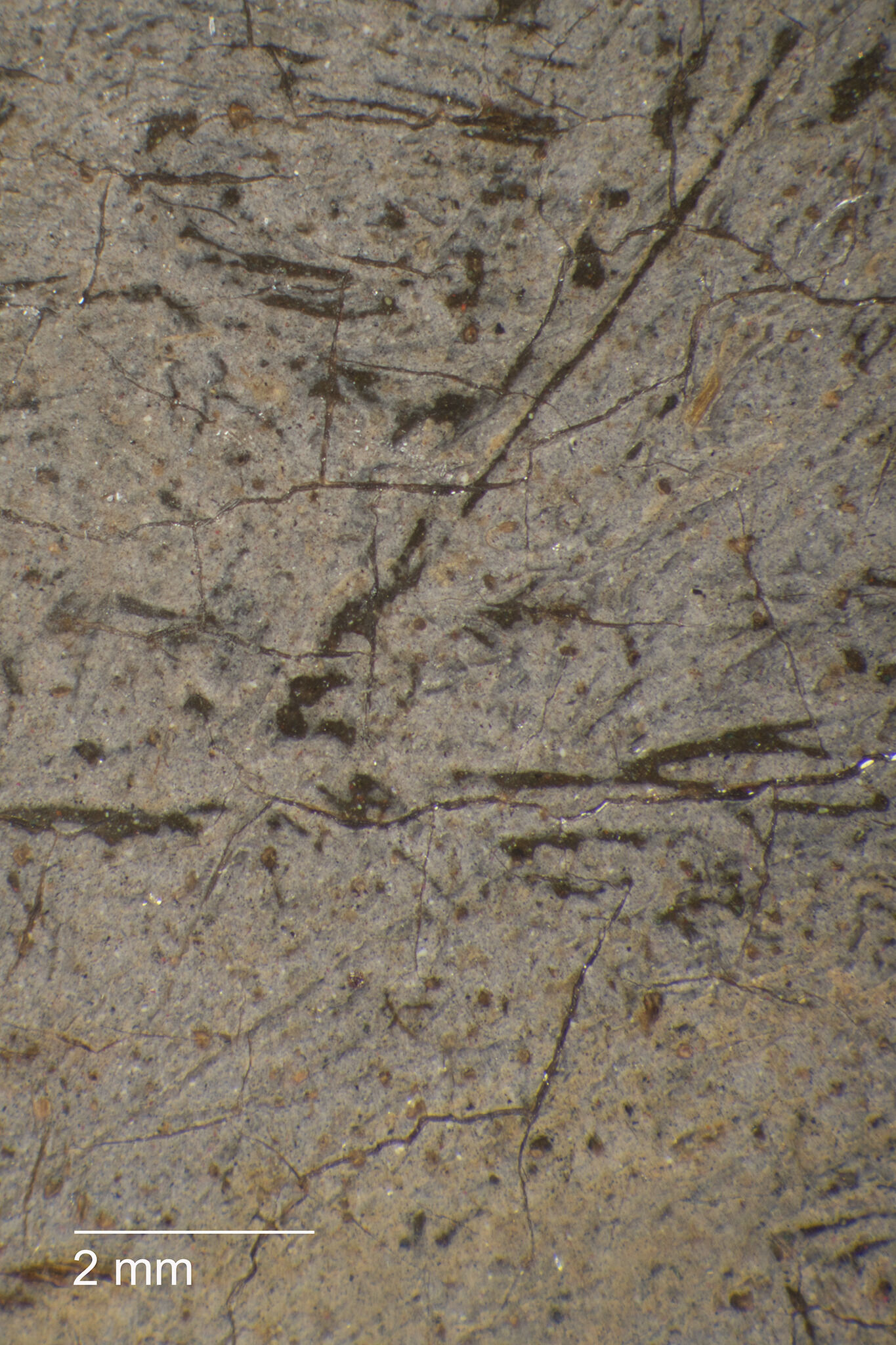

Fig. 22. Photomicrograph of two tiny holes on the chariot wheel, partially filled with wax from the lining process, Triumph of Bacchus (1635–36)

Fig. 22. Photomicrograph of two tiny holes on the chariot wheel, partially filled with wax from the lining process, Triumph of Bacchus (1635–36)

Fig. 23. Photomicrograph, green paint beneath the right sky of Triumph of Bacchus (1635–36)

Fig. 23. Photomicrograph, green paint beneath the right sky of Triumph of Bacchus (1635–36)

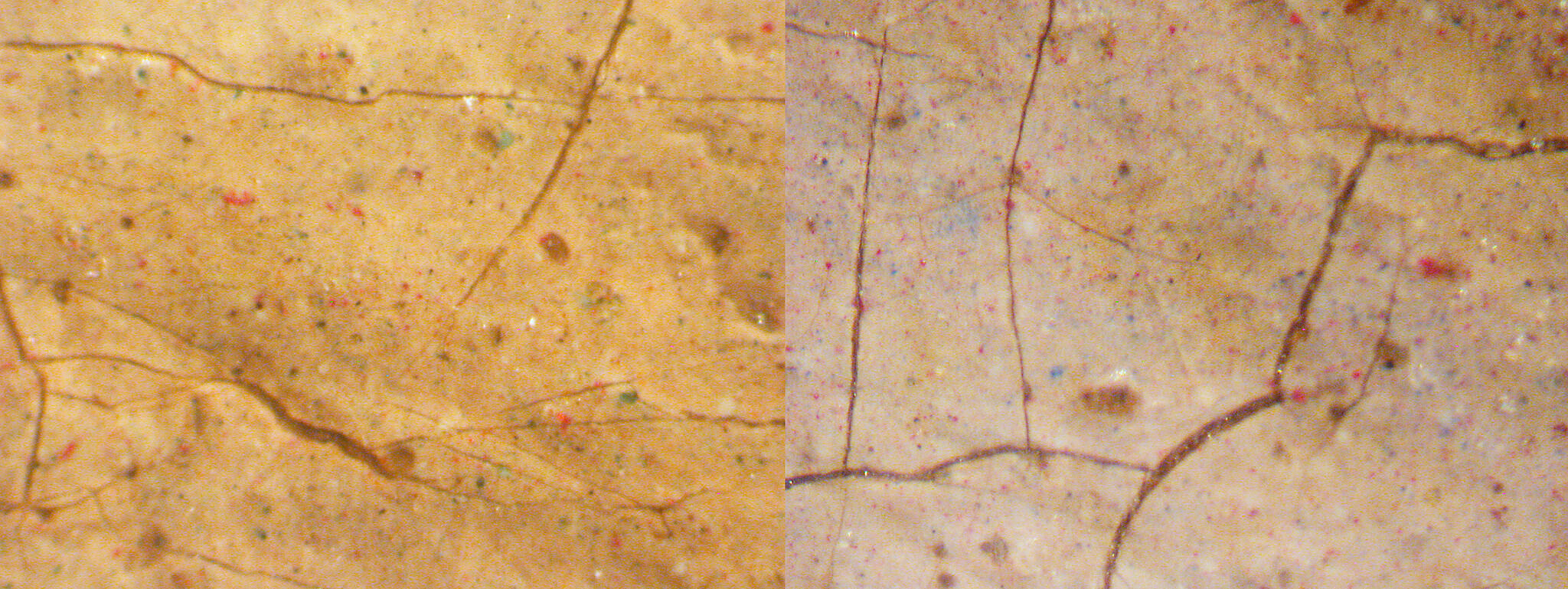

Despite Poussin’s thorough preparatory process, a number of significant artist changes can be identified on Bacchus.24The presence of these significant compositional changes further validates the authenticity of Bacchus, since it would be highly unusual for a copyist to take liberties with primary components of Poussin’s composition. Green paint beneath the upper right sky corresponds to an early placement of trees that initially balanced those on the left (Fig. 23). The dark shape of this tree grouping is faintly visible in the reflected infrared digital photographreflected infrared digital photograph: An infrared image produced in the 700–1000 nanometer range, typically captured using an infrared-modified digital camera. See infrared photography. of Figure 24, extending 37 centimeters toward the center of the painting. Poussin’s shift away from a symmetrical border of trees is significant when compared to Pan and Silenus, for as Christopher Wright observed, “all three [Richelieu] compositions are set against a tree-filled landscape where the trunks form elaborate patterns except in The Triumph of Bacchus where they only occupy the left hand part of the background.”25Christopher Wright, Poussin Paintings: A Catalogue Raisonné (London: Harlequin Books, 1985), 53. Infrared imaging also reveals that a highly reflective garment once draped across the trumpeter’s body, and his shoulder and arm were repositioned three times. In one adjustment, his raised arm suspended red drapery above his proper left shoulder (Fig. 25). The garment can be inferred to have been painted with vermilion, based on this infrared behavior and the red hue that has emerged as aging of the overlying paint has increased its transparency. Additionally, this figure’s dramatic serpent horn was initially a much simpler instrument with a flared end, similar to the trumpet depicted on the left side of Pan, with a strap or ribbon hanging below it. Infrared imaging also reveals that the rightmost female once held a staff with an oval-shaped tip, perhaps a second thyrsus, that was modified to become a branch (Fig. 26).

Fig. 24. Reflected infrared digital photograph captured between 850-1000nm, detail of the upper right sky, Triumph of Bacchus (1635–36)

Fig. 24. Reflected infrared digital photograph captured between 850-1000nm, detail of the upper right sky, Triumph of Bacchus (1635–36)

Fig. 25. Infrared reflectogram captured between 1.5-1.7 microns, detail of changes made to the trumpeter’s shoulder and his musical instrument, Triumph of Bacchus (1635–36)

Fig. 25. Infrared reflectogram captured between 1.5-1.7 microns, detail of changes made to the trumpeter’s shoulder and his musical instrument, Triumph of Bacchus (1635–36)

Fig. 26. Infrared reflectogram of the rightmost bacchante, captured between 1.5-1.7 microns, Triumph of Bacchus (1635–36). A pinecone-tipped thyrsus initially depicted in her right hand was replaced in the final composition with a vine branch.

Fig. 26. Infrared reflectogram of the rightmost bacchante, captured between 1.5-1.7 microns, Triumph of Bacchus (1635–36). A pinecone-tipped thyrsus initially depicted in her right hand was replaced in the final composition with a vine branch.

Fig. 27. Reflected infrared digital photograph captured between 850-1000nm, detail showing the original placement of Cupid’s quiver, Triumph of Bacchus (1635–36)

Fig. 27. Reflected infrared digital photograph captured between 850-1000nm, detail showing the original placement of Cupid’s quiver, Triumph of Bacchus (1635–36)

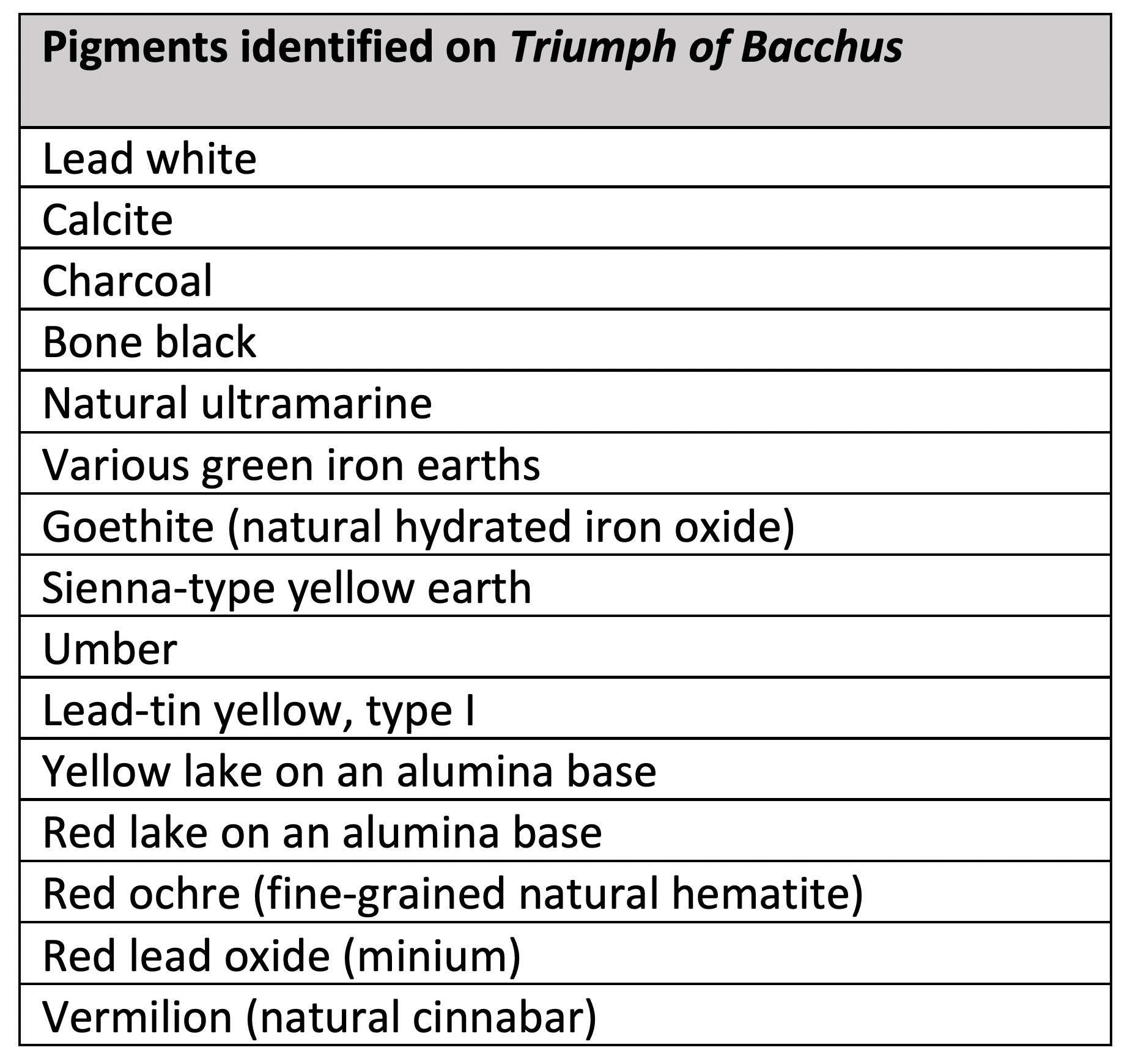

Poussin’s Choice of Pigments

At the first level of scrutiny, the palette study entailed identifying which pigments were used and which were excluded from among those available to Poussin in the early seventeenth century. At a deeper level, we wished to know the roles played by the pigments in their different combinations and to learn, where possible, how those roles have changed due to aging effects, altering the painting’s appearance. As shown below, iron earth pigments (naturally-occurring mineral mixtures in which iron plays a critical role in the color) are used in abundance throughout all of the paints. In addition, the iron earths used by Poussin in Bacchus are extremely diverse in both color and mineral type. When these complex mixtures are blended with each other, and diluted by lead whitelead white: The most widely used white pigment from Roman times until well into the industrial period, it consists of cerussite and/or hydrocerussite, mineral names for neutral lead carbonate and basic lead carbonate, respectively. Plumbonacrite, another basic lead carbonate with proportionately less carbonate than hydrocerussite, can sometimes be found, as well. The whitest forms used in painting were historically produced by inducing lead metal to corrode in the presence of vinegar fumes., their identification and understanding the roles they play in the appearance of the painting become extremely challenging.

There is an additional challenging aspect to the study of Poussin’s palette created by his deeply philosophical approach to painting.28An approach that was not always attuned to his patron’s expectations; see Helen Glanville, “Aspect and Prospect—Poussin’s Triumph of Silenus,” Artibus et Historiae 37 (74) (2016): 241–54. In keeping with the debates of his peers and early modern attempts to create a framework of thought uniting perspective, atmospheric/optical effects, and material properties with humankind’s relationship to nature and the cosmos, he is thought to have incorporated small amounts of certain pigments for reasons unconnected with their practical performance in the paint.29H. Glanville, H. Rousselière, L. De Viguerie, and Ph. Walter, “Mens Agitat Molem: New Insights into Nicolas Poussin’s Painting Technique by X-ray Diffraction and Fluorescence Analyses,” in Science and Art: The Painted Surface, ed. Antonio Sgamellotti, Brunetto Giovanni Brunetti, and Costanza Miliani (London: The Royal Society of Chemistry, 2014), 314–35. In short, we do not know in some cases whether small additions of material with a limited influence on appearance were purposeful or not. Poussin may have included small amounts of certain pigments because they “belonged” there, in his worldview, whether they had a practical impact or not.

The distinctive traits of Poussin’s work lie in the idiosyncrasies of his use of otherwise common materials. In some cases, these may reflect an underlying procedural philosophy unique to Poussin. It is in the identification of variants among similar materials available in his day, combinations used for his specific effects, and changes wrought on those materials by his preparation procedures, that one could expect to discover new characteristics of the artist’s use of materials.

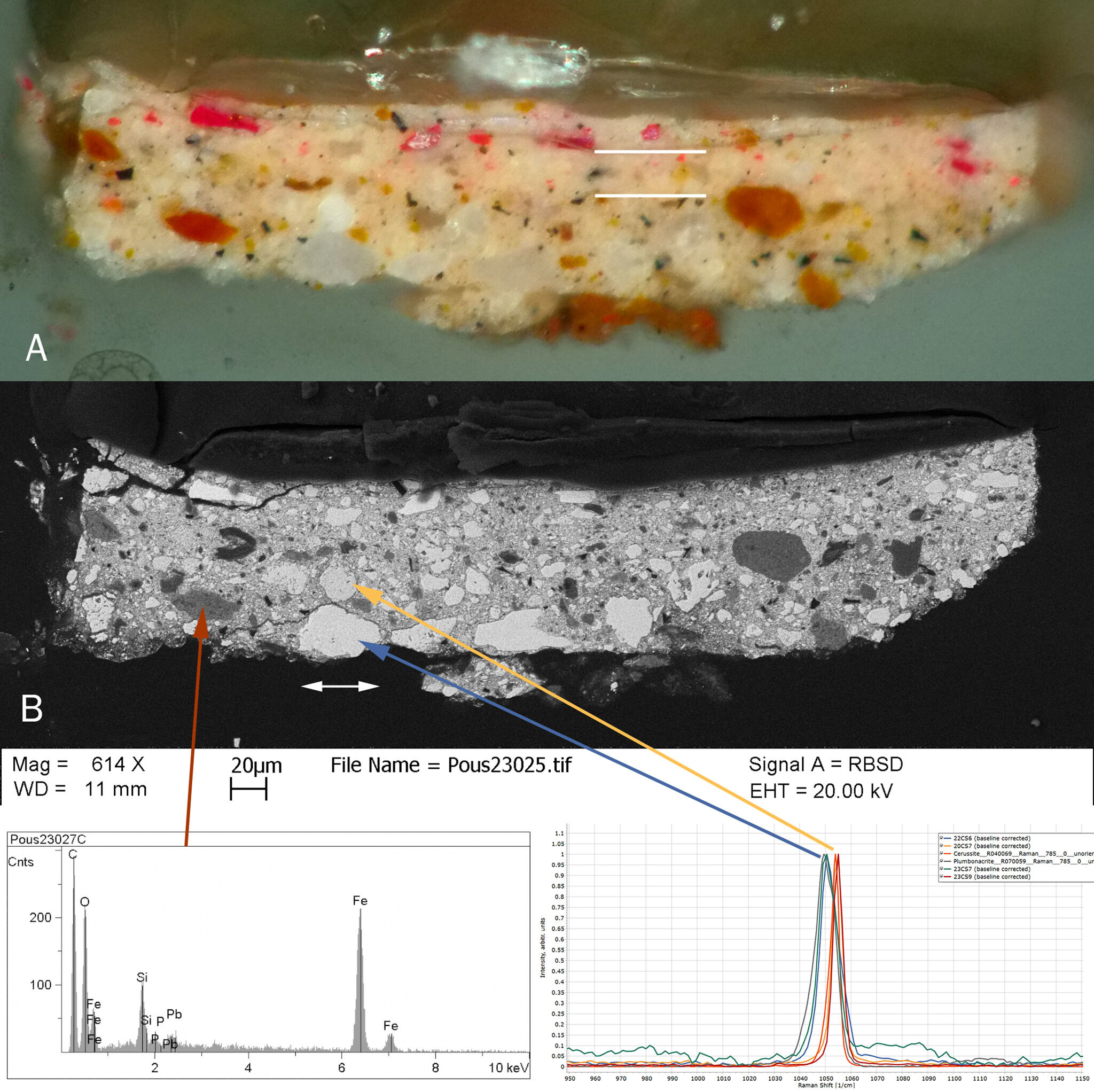

To obtain the most concise information possible about highly dispersed

individual pigment grains, a heavy reliance has been placed upon

elemental analysis of individual pigment particles using electron beam-excited x-ray spectrometryelectron-beam-excited X-ray spectrometry (sometimes referred to as XES for “X-ray energy spectrometry” or EDX for “energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometry”): An analytical technique used for the identification of elements without regard to their state of combination. The underlying principle of X-ray spectrometry is the same as that of X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF): individual elements can be induced to emit unique identifying X-rays. When used during examination of a sample in the scanning electron microscope (SEM), it offers several profound advantages over in-situ analysis with the handheld unit or XRF elemental mapping spectrometer. Electron beam excitation in the SEM favors the response of light elements including even carbon and oxygen. Also, the extreme localization of the electron beam exciting the response allows individual pigment particles to be analyzed in complicated mixtures while simultaneously revealing particle shapes. For example, the presence of both lead and chromium in a single rod-like particle differentiates it as chrome yellow from the case of viridian merely mixed with lead white, where chromium (oxide) and lead (carbonate) occur in separate particles. in the scanning electron microscope (SEM)scanning electron microscopy (SEM): Performed on a microsample of paint, the SEM provides a means of studying particle shapes beyond the magnification limits of the light microscope. This becomes increasingly important with the painting materials introduced in the early modern era, which are finer and more diverse than traditional artists’ materials. The SEM is routinely used in conjunction with an X-ray spectrometer, so that elemental identifications can be made selectively on the same minute scale as the electron beam producing the images. SEM methods are particularly valuable in studying unstable pigments, adverse interactions between incompatible pigments, and interactions between pigments and surrounding paint medium, all of which can have profound effects on the appearance of a painting., and the correlation of these results to optical properties and

RamanRaman spectroscopy: A microanalytical technique applicable primarily to pigments and minerals, differentiating them based on both chemical bonding and crystal structure, often with extremely high sensitivity for individual particles. For example, traditional indigo and synthetic phthalocyanine blue are both carbon compounds not well differentiated by other methods utilized here, especially when used dilutely. However, they give unique Raman spectra. Calcium carbonates derived from chalk or pulverized oyster shell of identical chemical compositions can be differentiated based on their crystal structures (calcite and aragonite, respectively). spectra.30Samples were prepared in two ways: as embedded cross sections and as fracture sections presented to the instrument without further preparation, apart from a conductive coating of evaporated carbon. Cross-comparisons have been made with optical microscopy and UV fluorescence microscopy, with a few confirmatory identifications carried out by Raman spectroscopy. Polarized light microscopy (PLM) has then been used to correlate differences in color and optical properties with individual pigment species. PLM has been especially important in disclosing differences among the green iron earths which share overlapping elemental compositions. The formal cross sections often provide a clearer view of the sequence of paint applications, while the fracture fragments often reveal pigment alteration and texture features more clearly. As others have noted, the dry, fresco-like appearance favored by Poussin often entailed using paints with a slight deficit of oil medium, resulting in samples that can be brittle and difficult to prepare for analysis. Pigments identified in the ground and paint layers

are shown in Table 1.

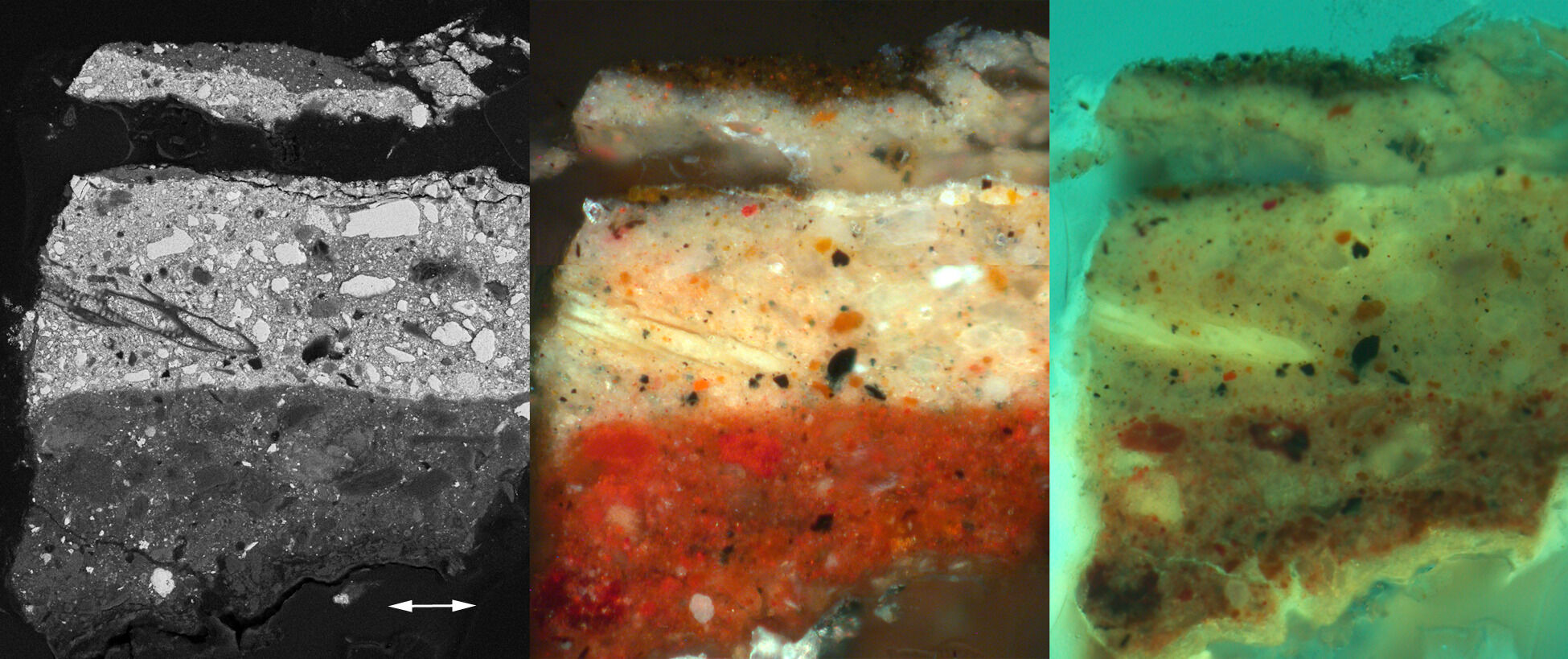

Construction and Materials of the Double Ground

The colored ground plays an important visual role in the painting by

influencing the tonality of overlying paints, some of which were never

entirely opaque and which have become less so as a result of aging. The

visible role of the ground is especially notable in setting the base

color in the shadows of the river god’s green drapery (Fig. 29). Aging

effects in the ground strata, therefore, have an impact on ways in which

the present-day appearance of the painting differs from when it left the

studio. Knowing that the ground played a visual role under certain

colors, and that this role might have needed to be suppressed or

modified under others, we sought to locate intermediate paint

applications such as washes or underpainting layers. Several cross

sections contain the ground layers while others were taken exclusively

to characterize the overlying paint.

Prior investigators studying numbers of works by Poussin have taken an approach distinct from ours by quantifying the average major element concentrations in their grounds using electron-beam-excited X-ray spectrometry performed in the scanning electron microscope. Alain Duval included nine works by Poussin that he presented in this context of broader seventeenth- and eighteenth-century painting practice.31A. Duval, “Les préparations colorées des tableaux de l’École Française des dix-septième et dix-huitième siècles,” Studies in Conservation 37 (1992): 239–58. By working from cross sections, he bypassed complicating factors that are inherent to non-sampling methods for the analysis of superimposed layers, methodology that, in any case, was in its infancy at that time. However, a series of assumptions about how to allocate the responses for individual elements are required in his approach. For example, lead can exist in particulate form as lead white or red lead pigments and simultaneously as lead dissolved in the medium where it functions as a drier, or siccative, for oil.32Duval commented upon the difficulty of distinguishing fine-grained red lead when its color cannot be distinguished from other reds in a colored ground mixture. Our own tests have confirmed the use of fine red lead as a minor component of the grounds in Bacchus and the attendant difficulty of locating it.

In a subsequent paper, Duval presented the results of this experimental protocol for the grounds of 26 works by Poussin.33A. Duval, “Les enduits de préparation des tableaux de Nicolas Poussin,” Techné 1 (1994): 35–41. He classified the ground layers into three types based on color and dominant elemental composition. He defined these classes as ferrugineous soils, ochres, and iron oxides, based upon their proportions of alumina, silica, and iron. With a single painting and no direct access to that body of data, our approach has been descriptive, rather than classifying, and focused on the individual constituents of the ground. In addition, we have observed that some constituents of the ground also play important roles in the upper paint layers. It should be borne in mind that a dark ground layer may contain the sediment collected from washing brushes whose color is overwhelmed by the dark earth minerals. In that case, minor amounts of costly or specialized pigments may not be indicative of purposeful additions to the ground.

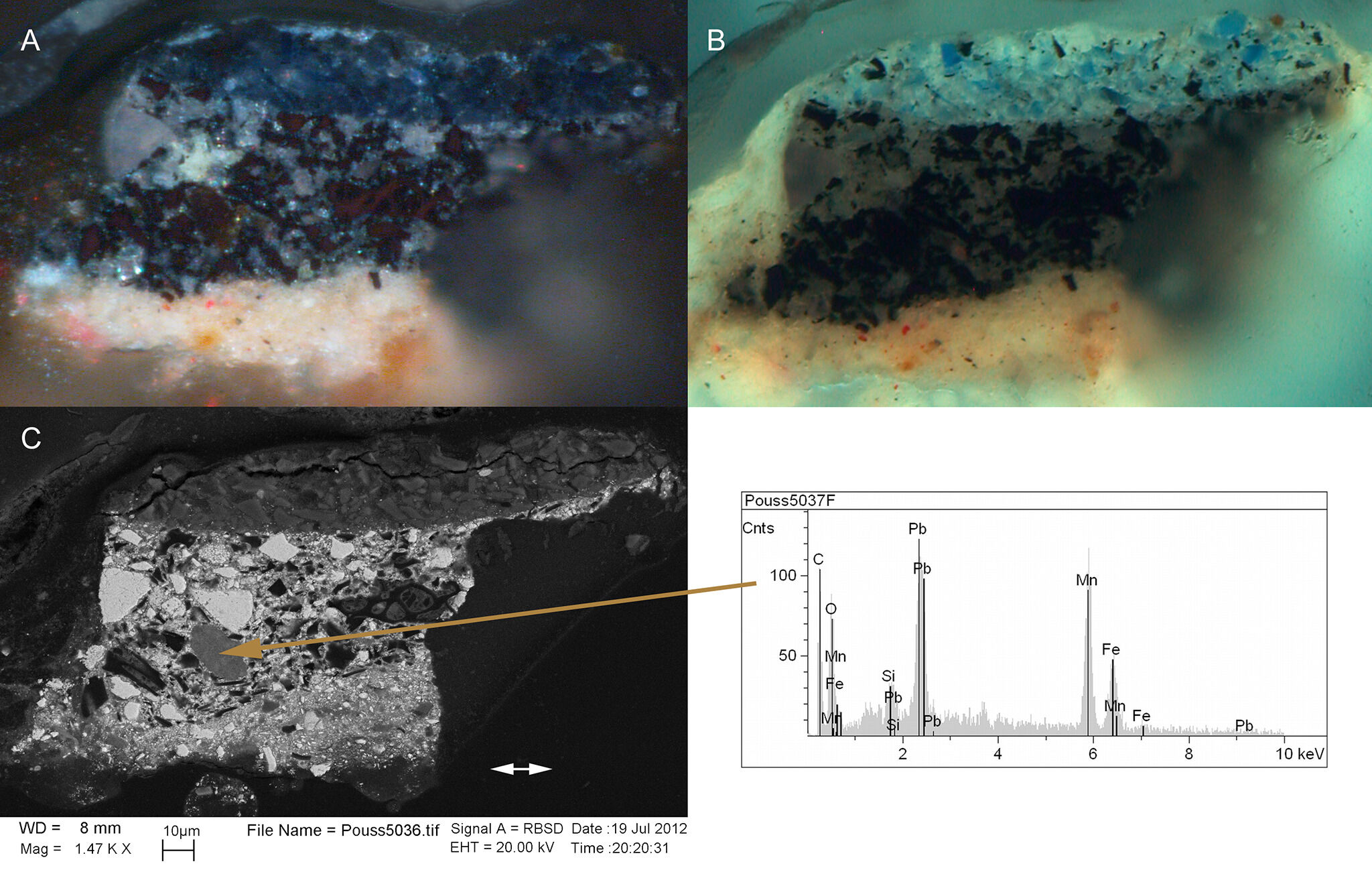

The lower, ruddy ground in Bacchus is comprised mostly of earth pigments with a low content of lead white (Fig. 8).34Pigment species confirmed in the lower, dark ground include quartz, sodium feldspar, fine hematite (red ochre) and goethite (yellow ochre), ferrous silica, light green iron earth with undulose optical extinction, iron-magnesium aluminosilicates (green earth), and discolored medium with minor cinnabar, red lead, calcium carbonate, lead white, lead soap alteration products, potassium clay or mica, red lake on alumina, gypsum, bone black, and chromite traces. One example of a large red agglomerate containing calcium-potassium sulfate along with iron oxides points to a possible origin for the iron earth in a jarosite (potassium iron sulfate) formation. The upper beige ground consists of lead white tinted by yellow, orange, red, and black pigments, including several forms of hydrated iron oxides, and traces of vermilion, red lead, and charcoal.35Pigment species confirmed in the upper beige ground through SEM elemental analysis include lead white, quartz (some of it splintered and unworn), potassium feldspar, sodium feldspar, sodium-potassium feldspar, coarse hydrated iron oxide, ferrous silica grains, lead soap alteration products, calcite, very fine goethite (yellow ochre), and minor amounts of coarse red lake, clay, cinnabar, charcoal, and more rarely, ultramarine, gypsum, and potassium-calcium sulfate. Lead white pigment particles in the beige ground vary markedly in shape, size, and crystal forms. Their size variation is extreme, ranging from less than one micron to over 50 microns in diameter. Among the coarse lead white grains there are both agglomerates of fine crystals and coarse, splintery fragments of individual crystals intermingled with finely-ground and highly-dispersed ones. Recent research has shown that lead white in these differing size ranges has often been refined by differing procedures, with the finest grades resulting from washing and levigation, leading to different proportions of its two main compounds: cerussite and hydrocerussite.36V. Gonzalez, G. Wallez, T. Calligaro, M. Cotte, W. De Nolf, and M. Eveno, “Synchrotron-based high angle resolution and high lateral resolution X-ray diffraction: Revealing lead white pigment qualities in old masters paintings,” Analytical Chemistry 89 no. 24 (2017): 13203–11.

Construction and Materials of the Blue Robe

Brightly colored garments needed to be free of influence from the color of the beige upper ground and usually employ an intermediate layer. For the blue robe of the rightmost bacchante, this entailed the use of charcoal to create a more neutral base for this semi-transparent color. Five cross sections near the right side of the painting demonstrate that the blue-draped bacchante was left in reserve when the brown background was painted. The blue is underlain by a layer consisting mostly of coarse charcoal in lead white, whose thickness varies in response to the depth of blue color required at that point. The charcoal underlayer dominates the appearance of the robe in the infrared reflectogram, showing variations in its application (Fig. 21). The wide distribution in size of lead white grains seen in the upper ground is also characteristic of lead white in the black underlayer paint.

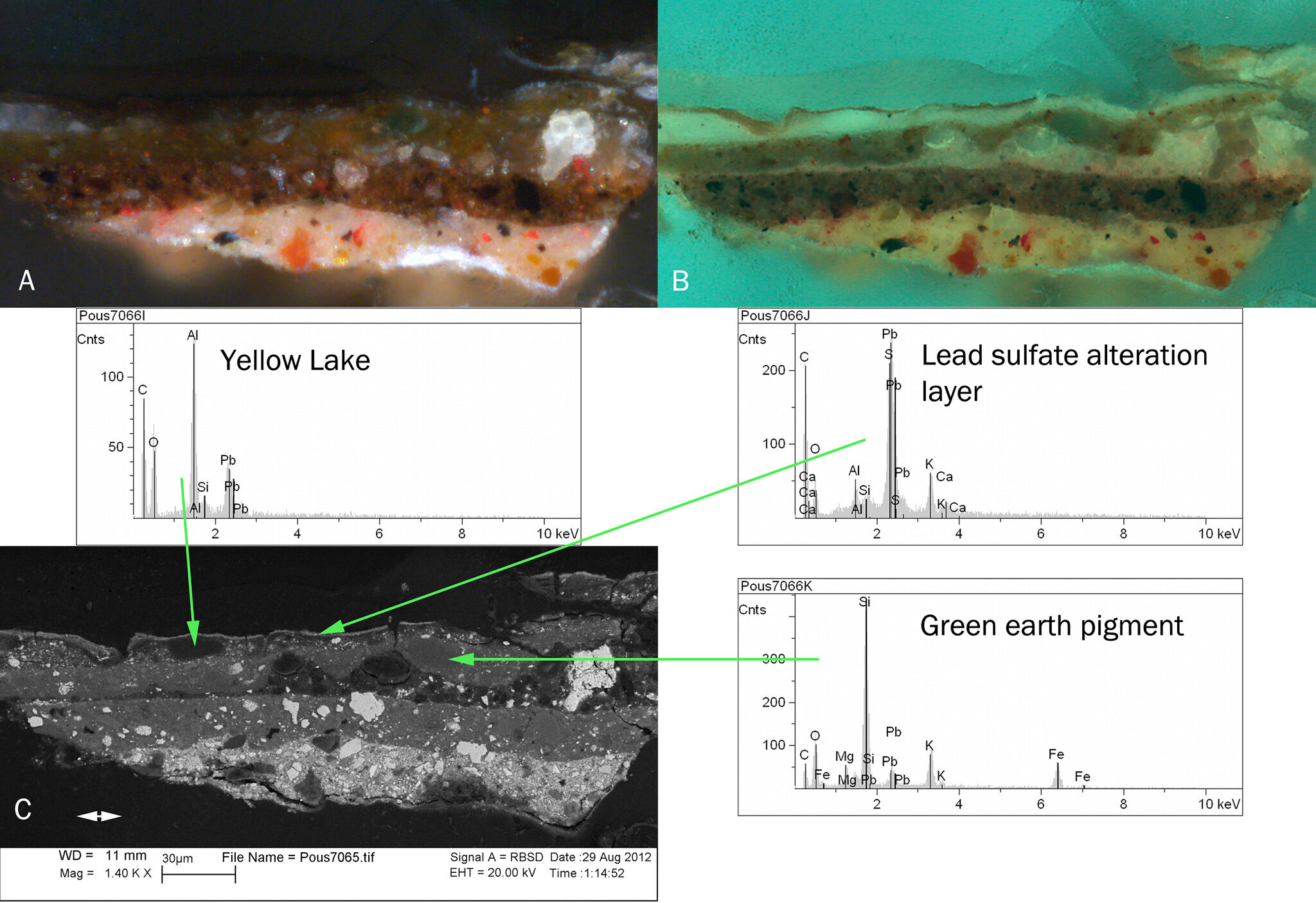

Construction and Materials of the Peach Scarf

Bright glazes are evident in the shadows of the drapery and important for the peach-colored scarf swirling around the left arm of the rightmost bacchante. Unlike the blue garment, the scarf was painted over the brown background rather than left in reserve. It owes its color primarily to a yellow lake pigment prepared on a base of alumina and contains a high proportion of non-particulate lead in the medium, with few, and widely-dispersed, fine grains of lead white. The construction of the scarf near the shoulder entailed a yellow-brown underlayer of lead-tin yellow particles whose lead and tin proportions vary greatly, containing lead soap and lead chloride alteration products, cinnabar, lead white, alumina lake, and iron oxides. Uppermost is a yellow-brown layer containing yellow lake on alumina with a thin alteration layer of lead sulfate and lead potassium sulfate. The scarf has been thinned by abrasionabrasion: A loss of surface material due to rubbing, scraping, frequent touching, or inexpert solvent cleaning. and prior cleanings so that these alteration products, typically consisting of anglesite and palmierite, can be inferred to have developed subsequent to some prior cleaning. These species are widely encountered on painted surfaces, formed from the interaction of lead, sulfate, and potassium ions.38A. van Loon, P. Noble, and J. J. Boon, “White hazes and surface crusts in Rembrandt’s Homer and related paintings,” ICOM-CC Lisbon 2011: Preprints 16th triennial conference Lisbon, 19–23 September 2011, 1–10.,39Stephen W. T. Price, Annelies Van Loon, Katrien Keune, Aaron D. Parsons, Claire Murray, Andrew M. Beale, and J. Fred W. Mosselmans, “Unravelling the spatial dependency of the complex solid-state chemistry of Pb in a paint micro-sample from Rembrandt’s Homer using XRD-CT,” Chemical Communications 55 (2019): 1931–34.,40Steven De Meyer, Frederik Vanmeert, Rani Vertongen, Annelies van Loon, Victor Gonzalez, Geert van der Snickt, Abbie Vandivere, and Koen Janssens, “Imaging secondary reaction products at the surface of Vermeer’s Girl with the Pearl Earring by means of macroscopic X‑ray powder diffraction scanning,” Heritage Science 7, no. 1 (2019): 1–11.

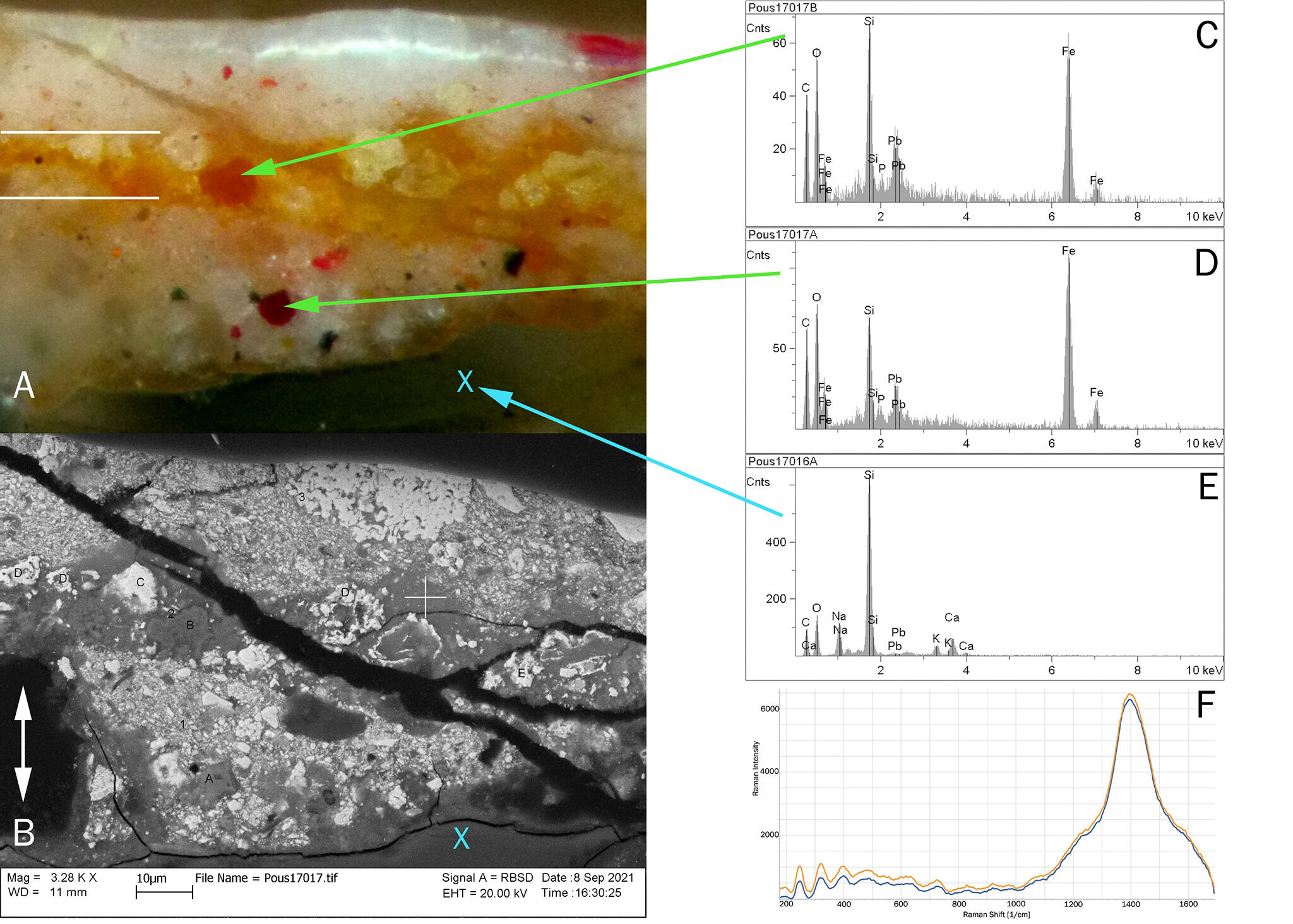

Construction and Materials of the Yellow-Orange Robe

The bright yellow-orange robe of the bacchante bearing the serpent on a

staff was studied in two locations. The shoulder highlight was tested

alone, and a sample of the flesh paint from below the raised hem that