Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Claude Gellée, called Le Lorrain, Mill on the Tiber, ca. 1650, and Landscape with a Piping Shepherd, 1667,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.206.5407.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Claude Gellée, called Le Lorrain, Mill on the Tiber, ca. 1650, and Landscape with a Piping Shepherd, 1667,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.206.5407.

He made his first copy of Landscape with a Piping Shepherd (Fig. 2) around 1815 in England, working directly from the original painting that hung on the walls of his home. Every detail of the composition, including the shepherd in classical dress playing his pipe, follows the precedent set in the Nelson-Atkins painting. Both Glover and, before him, the painter Richard Wilson (1714–82) were nicknamed the “English Claude”—a sign that emulation of Claude was the ideal among English landscape artists.11Hansen, John Glover and the Colonial Picturesque, 40, 74. Glover filled hundreds of sketchbooks with copies after after Claude and other Old Masters he saw at picture galleries or English country estates.12He brought these notebooks to Tasmania, and the State Library of New South Wales has digitized them: https://collection.sl.nsw.gov.au/record/nZNvqE8n Like Claude, Glover also composed picturesque landscapes after careful observation of his surroundings. Ian McLean has argued that to criticize Glover for not finding “empirical truth” in painting, for rendering both English and Australian landscapes alike in a Claudian image, is to dismiss nineteenth-century England’s demand for idyllic landscapes amid the tumult of industrialization and the destruction of the British countryside.13McLean, “The Australianness of the English Claude,” 132. Glover earned good money in RegencyRegency: Part of the Georgian era in England, King George III’s son ruled as his proxy, dating from approximately 1811 until 1820. England, and his fellow artists regarded him highly, although his application for membership in the Royal AcademyRoyal Academy of the Arts: A London-based gallery and art school founded in 1768 by a group of artists and architects. was rejected.14Glover did exhibit at the Royal Academy multiple times, however. Hansen, John Glover and the Colonial Picturesque, 18, 70. After embarking on an ambitious program of solo exhibitions on Pall Mall in the 1820s, Glover may have judged the British art market too crowded for him to earn what he wanted, prompting him to sell his art collection in preparation for a move to Oceania.15Hansen suggests that one reason for Glover’s move, despite weathering multiple economic recessions, was the competitive British art market of the 1820s. By that time, London was flush with galleries and independent art exhibitions outside of the Academy. Hansen, John Glover and the Colonial Picturesque, 72.

Fig. 3. John Glover, after Claude Gellée (Claude Lorrain), Landscape with a Piping Shepherd, 1833, oil on canvas, 28 1/2 x 43 7/8 in. (72.5 x 111.5 cm), National Gallery of Australia, Canberra. Purchased with the assistance of Henry Dalrymple 2012, 2011.1273

Fig. 3. John Glover, after Claude Gellée (Claude Lorrain), Landscape with a Piping Shepherd, 1833, oil on canvas, 28 1/2 x 43 7/8 in. (72.5 x 111.5 cm), National Gallery of Australia, Canberra. Purchased with the assistance of Henry Dalrymple 2012, 2011.1273

Fig. 4. John Glover, Moulting Lagoon and Great Oyster Bay, from Pine Hill, ca. 1838, oil on canvas, 29 3/4 x 44 1/2 in. (75.6 × 113 cm), National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Purchased with assistance of an anonymous donor and the M. G. Chapman Bequest, 2011, 2011.11. Photo: National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Fig. 4. John Glover, Moulting Lagoon and Great Oyster Bay, from Pine Hill, ca. 1838, oil on canvas, 29 3/4 x 44 1/2 in. (75.6 × 113 cm), National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Purchased with assistance of an anonymous donor and the M. G. Chapman Bequest, 2011, 2011.11. Photo: National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

The reasons behind John Glover’s choice to set sail for Australia at the age of sixty-three after a successful career in England, undertaking a five-month sea journey with his family, are unclear. Glover lived in a free-settler colony that was diminutive compared to the number of convicts sent to Van Diemen’s Land.19Seventy-two thousand convicts were sent to Van Diemen’s land in the first half of the nineteenth century to do hard labor. James Boyce, “Return to Eden: Van Diemen’s Land and the Early British Settlement of Australia,” Environment and History 14, no. 2 (May 2008): 289. In the census of 1835, Hobart Town had 13,826 inhabitants. See Charles Darwin, Journal of Researches into the Natural History and Geology of the Countries Visited during the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle Round the World, 2nd ed. (London: John Murray, 1845), 356. At times, Glover’s art nods to the use of the convicts’ forced labor in the ranching endeavors of British settlers, as in his Moulting Lagoon and Great Oyster Bay, from Pine Hill (Fig. 4), where the Claudian shepherd’s red coat identifies him as a convict.20His contemporaries noted Glover’s use of convict labor on his Tasmanian farm. In his memoir of a six-year visit to Tasmania, an Englishman named James Backhouse wrote, ldquo;We visited John Glover, a celebrated painter, who came to this country when advanced in life, to depict the novel scenery: his aged wife has been so tried with the convict female servants, that she has herself undertaken the house-work. We generally find that females prefer England to Tasmania, on account of this annoyance.” Excerpt from “A Narrative of a Visit to the Australian Colonies,” Launceston Examiner 3, no. 169 (February 3, 1844): 78. In another deviation from Claude’s Eden-like landscapes, Glover’s paintings bear signs of modern agricultural development. The land jutting out into the lake with a distant small town is present in both the Nelson-Atkins Landscape with a Piping Shepherd and the Glover copy, but Glover’s town is the logical extension of farmland, excised of trees, whereas Claude’s town is nestled within lush greenery.

Fig. 5. John Glover, Mount Wellington and Hobart Town from Kangaroo Point, 1834, oil on canvas, 30 x 60 in. (76.2 x 152.4 cm), Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery and National Gallery of Australia, Canberra. Nerissa Johnson Bequest Fund 2001, 2001.207

Fig. 5. John Glover, Mount Wellington and Hobart Town from Kangaroo Point, 1834, oil on canvas, 30 x 60 in. (76.2 x 152.4 cm), Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery and National Gallery of Australia, Canberra. Nerissa Johnson Bequest Fund 2001, 2001.207

Fig. 6. John Glover, after Claude Gellée (Claude Lorrain), Mill on the Tiber, ca. 1840, oil on canvas, 30 x 45 in. (76 x 114 cm), private collection

Fig. 6. John Glover, after Claude Gellée (Claude Lorrain), Mill on the Tiber, ca. 1840, oil on canvas, 30 x 45 in. (76 x 114 cm), private collection

In his 1835 exhibition, John Glover’s Australian pictures were exhibited alongside the Claude originals he left behind. He helped shaped the English people’s view of their vast empire, enticing viewers to compare and contrast his Australian surroundings with his landscapes of Italy and Britain, and to compare them all with Claude’s originals.24A Catalogue of Pictures. It is impossible to divide the European, Claude-inspired Glover from the Anglo-Australian settler he became later in life. In 1840, ten years after leaving his homeland and his Claudes, Glover made a copy from memory of the Nelson-Atkins Mill on the Tiber (Fig. 6), unknown until it was sold from a private collection in Sydney in 2006. The sales catalogue notes that the canvas is similar in size to Glover’s other Tasmanian canvases.25Glover used canvases that are roughly 30 by 45 inches while he was in Tasmania. See Australian, International and Aboriginal art (Double Bay, Australia: Bonhams and Goodman, December 5 and 11, 2006), unpaginated, as The Mill on the Tiber. The mill seems newer than in Claude’s antique vision, and Glover does away with the classical figures altogether, filling the foreground with oversized cattle. Claude’s mossy mountains in the backdrop become bare and sunbaked in the Tasmanian sun, but ultimately Glover creates a relatively faithful copy, shaped by the Claudean ideal and its nineteenth-century implications of a perceived European cultural supremacy and imperial domination. Painted just a year before Glover’s last recorded oils, Glover’s copy of Mill on the Tiber speaks to Claude’s lasting impact on the paintings of the British empire.

Notes

-

See Claire Pace, “‘Paise antique:’ Claude Lorrain and Seventeenth-Century Responses to Antique Landscape Painting,” Artibus et Historiae 36, no. 72 (2015): 305–39; Katalin Bartha-Kovács, “Réminiscences nostalgiques: la lumière et le Rien dans les marines de Claude Lorrain,” Svět literatury 30 (March 1, 2020): 15–28; Franz R. Kempf, Poetry, Painting, Park: Goethe and Claude Lorrain (Oxford: Legenda, 2020), 2.

-

See Tassi’s drawing The Goddess Diana with Her Hounds Standing in a Landscape, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, for evidence of elements familiar to Claude’s paintings. He also worked with Goffredo Wals (German, ca. 1605–38) briefly. See Patrizia Cavazzini, “Claude’s Apprenticeship in Rome: The Market for Copies and the Invention of the Liber Veritatis,” Konsthistorisk tidskrift 73, no. 3 (2004): 133–46; and Marcel Rœthlisberger, “From Goffredo Wals to the Beginnings of Claude Lorrain,” Artibus et Historiae 16, no. 32 (1995): 9–37.

-

Patricia Cavazzini, “Agostino Tassi and the Organization of His Workshop: Filippo Franchini, Angelo Caroselli, Claude Lorrain, and the Others,” Storia dell’arte 91 (1997): 401.

-

Elizabeth Wheeler Manwaring, Italian Landscape in Eighteenth Century England: A Study Chiefly of the Influence of Claude Lorrain and Salvator Rosa on English Taste 1700–1800 (1925; repr. London: Frank Cass, 1965); Pietro Piana, Charles Watkins, and Ross Balzaretti, “‘Saved from the sordid axe’: Representation and Understanding of Pine Trees by English Visitors to Italy in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century,” Landscape History 37, no. 2 (2016): 32–56.

-

Dark mirrors made of obsidian and jet were used as early as the sixteenth century, but they became invaluable tools in experiencing nature in the late eighteenth century. For references to British artists using “Claude glasses,” see Claire Pace, “Claude the Enchanted: Interpretations of Claude in England in the Earlier Nineteenth-Century,” Burlington Magazine 111, no. 801 (December 1969): 733; Jeffrey Auerbach, “The Picturesque and the Homogenisation of Empire,” British Art Journal 5, no. 1 (Spring–Summer 2004): 48; and Stephen R. Wilk, Sandbows and Black Lights: Reflections on Black Lights (Oxford: Oxford Scholarship, 2021), 170–81. The educational materials for David Hansen’s 2003–2004 John Glover exhibition (John Glover and the Colonial Picturesque, Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, Hobart) make clear that Glover used a Claude glass, as well as a camera lucida, to reframe the landscape. His glass is in the collection of the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, Hobart. The definitive text on this device is Arnaud Maillet, The Claude Glass: Use and Meaning of the Black Mirror in Western Art, trans. Jeff Fort (Brooklyn, NY: Urzone, 2004). Thank you to David Hansen for suggesting it to me.

-

Henry Clay Trumbull, Seeing and Being: Or, Perception and Character (Philadelphia: John D. Wattles, 1889), 133.

-

Auerbach, “Picturesque and the Homogenisation of Empire,” 50.

-

David Hansen says that it is “feasible” that Glover purchased both Mill on the Tiber and Landscape with a Piping Shepherd from Kinnaird in late 1812. The English landscape painter Joseph Farington (1747–1821) notes in his diary entry for January 1, 1813, that Glover “had lately given 1700 guineas for two pictures painted by Claude”; see David Hansen, John Glover and the Colonial Picturesque, exh. cat. (Hobart, Tasmania: Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, 2003), 135.

-

Beginning in 1820, after the Royal Academy denied him admission, Glover began hosting exhibitions of his own at 16 Old Bond Street in London. There are no catalogues for these exhibitions.

-

Glover put the Nelson-Atkins Claudes up for sale in 1830 to help fund his emigration; they were not purchased until 1836. John Glover’s admiration for Claude, a sign of his Englishness, is a core facet of research on the artist. See John McPhee, John Glover, exh. cat. (Launceston, Tasmania: Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery, 1977); Hansen, John Glover and the Colonial Picturesque; Ian W. McLean, “The Australianness of the English Claude: Nation and Empire in the Art of John Glover,” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art 7, no. 1 (2006): 125–42; and Jim Berryman, “Nationalism, Britishness and the ‘Souring’ of Australian National Art,” Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 44, no. 4 (2016): 573–91.

-

Hansen, John Glover and the Colonial Picturesque, 40, 74.

-

He brought these notebooks to Tasmania, and the State Library of New South Wales has digitized them: https://collection.sl.nsw.gov.au/record/nZNvqE8n.

-

McLean, “The Australianness of the English Claude,” 132.

-

Glover did exhibit at the Royal Academy multiple times, however. Hansen, John Glover and the Colonial Picturesque, 18, 70.

-

Hansen suggests that one reason for Glover’s move, despite weathering multiple economic recessions, was the competitive British art market of the 1820s. By that time, London was flush with galleries and independent art exhibitions outside of the Academy. Hansen, John Glover and the Colonial Picturesque, 72.

-

Auerbach, “Picturesque and the Homogenisation of Empire,” 48.

-

Hansen, John Glover and the Colonial Picturesque, 208.

-

Auerbach, “Picturesque and the Homogenisation of Empire,” 50.

-

Seventy-two thousand convicts were sent to Van Diemen’s land in the first half of the nineteenth century to do hard labor. James Boyce, “Return to Eden: Van Diemen’s Land and the Early British Settlement of Australia,” Environment and History 14, no. 2 (May 2008): 289. In the census of 1835, Hobart Town had 13,826 inhabitants. See Charles Darwin, Journal of Researches into the Natural History and Geology of the Countries Visited during the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle Round the World, 2nd ed. (London: John Murray, 1845), 356.

-

His contemporaries noted Glover’s use of convict labor on his Tasmanian farm. In his memoir of a six-year visit to Tasmania, an Englishman named James Backhouse wrote, “We visited John Glover, a celebrated painter, who came to this country when advanced in life, to depict the novel scenery: his aged wife has been so tried with the convict female servants, that she has herself undertaken the house-work. We generally find that females prefer England to Tasmania, on account of this annoyance.” Excerpt from “A Narrative of a Visit to the Australian Colonies,” Launceston Examiner 3, no. 169 (February 3, 1844): 78.

-

The Palawa are the Aboriginal people native to Tasmania.

-

See David Hansen, “The Picturesque and the Palawa: John Glover’s Mount Wellington, and Hobart Town from Kangaroo Point,” in Art and the British Empire, eds. Tim Barringer, Geoff Quilley and Douglas Fordham (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2007), 38–52; Jeff Malpas, ed., The Place of Landscape: Concepts, Contexts, Studies (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011), 3–4; Hansen, John Glover and the Colonial Picturesque, 210–11; Julia Lum, “Fire-Stick Picturesque: Landscape Art and Early Colonial Tasmania,” British Art Studies (2018): https://sdoi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-10/jlum/001.

-

A Catalogue of Pictures; Descriptive of the Scenery, and Customs of the Inhabitants of Van Dieman’s Land, Together with Views in England, Italy, etc. Painted by John Glover, Esq.; To Which are Added Two Genuine, and Highly Finished Landscapes, by the Celebrated Claude Lorraine [sic], exh. cat. (1835; repr. London: J. Rogers, 1868), 3.

-

A Catalogue of Pictures.

-

Glover used canvases that are roughly 30 by 45 inches while he was in Tasmania. See Australian, International and Aboriginal art (Double Bay, Australia: Bonhams and Goodman, December 5 and 11, 2006), unpaginated, as The Mill on the Tiber.

Claude Gellée, called Le Lorrain, Mill on the Tiber, ca. 1650

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Diana M. Jaskierny and John Twilley, “Claude Gellée, called Le Lorrain, Mill on the Tiber, ca. 1650,” technical entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.206.2088.

MLA:

Jaskierny, Diana M., and John Twilley. “Claude Gellée, called Le Lorrain, Mill on the Tiber, ca. 1650,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.206.2088.

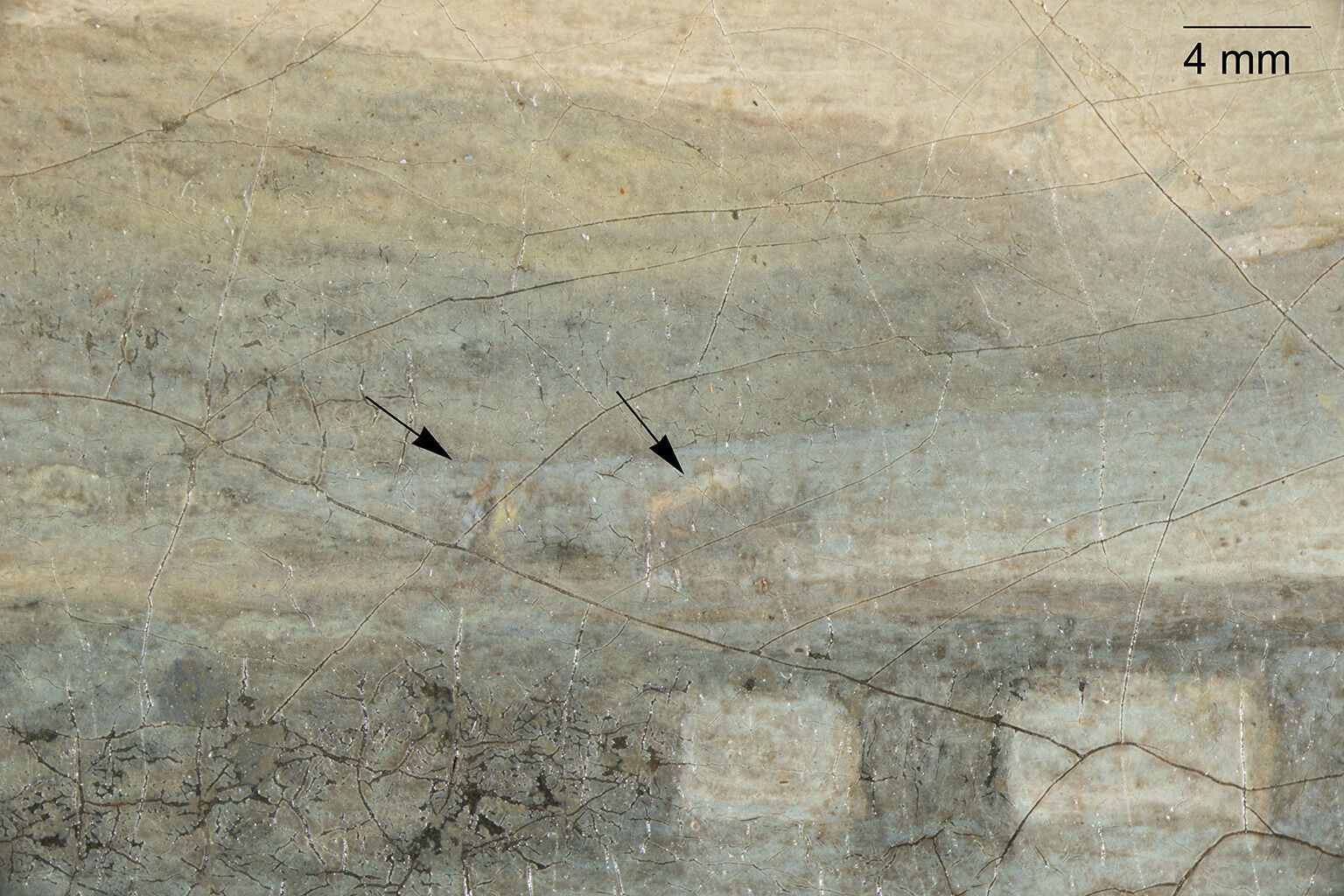

Claude Gellée, otherwise known as Claude Lorrain or Le Lorrain (1604–82), completed Mill on the Tiber around 1650 on a twill-weavetwill weave: A canvas weave in which one weft thread passes over one or more warp threads before passing under two or more warp threads, creating a pronounced diagonal pattern. canvas.1Evidence of the twill weave is visible in x-radiography and in raking light. Little more can be inferred from the canvas, as the painting’s tacking marginstacking margins: The outer edges of canvas that wrap around and are attached to the stretcher or strainer with tacks or staples. See also tacking edge. were removed, possibly during a lininglining: A procedure used to reinforce a weakened canvas that involves adhering a second fabric support using adhesive, most often a glue-paste mixture, wax, or synthetic adhesive. at an early date in its history. The painting was resized to enlarge the picture planepicture plane: The two-dimensional surface where the artist applies paint., likely before 1837, with additions of approximately 1 to 1.5 centimeters around all four sides.2Marcel Rothlisberger notes that the dimensions of the painting were altered sometime before 1837, which is when the current dimensions were first mentioned. Marcel Rothlisberger, Claude Lorrain: The Paintings (New York: Hacker Art Books, 1979), 303. While the original dimensions for this painting are unknown, stretcher-bar cracksstretcher cracks: Linear cracks or deformations in the painting’s surface that correspond to the inner edges of the underlying stretcher or strainer members. indicate that the current width may be slightly reduced from the original size, despite the prior extension at the edges.

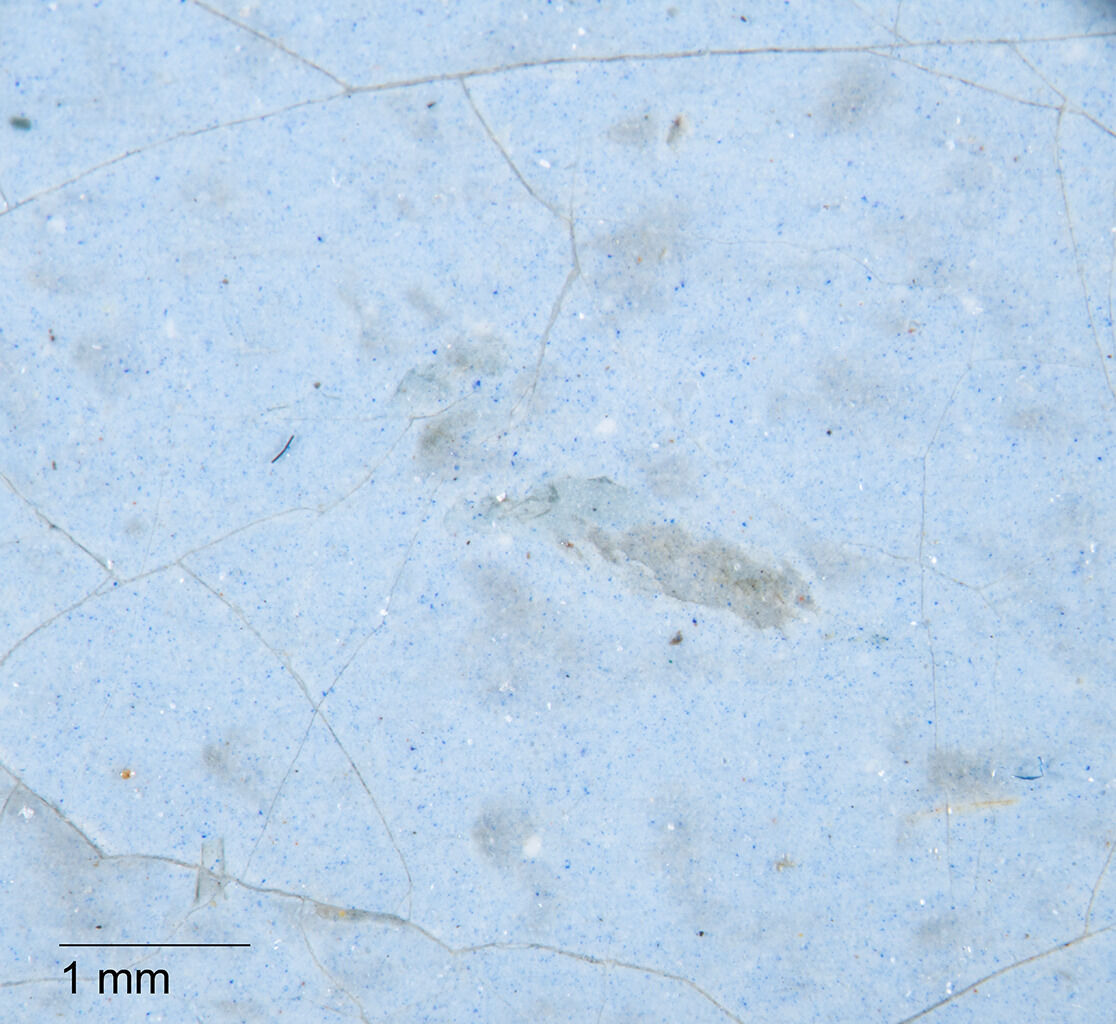

Fig. 8. Photomicrograph of the water, illustrating textured brushwork and the dark preparatory layer, Mill on the Tiber (ca. 1650)

Fig. 8. Photomicrograph of the water, illustrating textured brushwork and the dark preparatory layer, Mill on the Tiber (ca. 1650)

Fig. 9. Photomicrograph of incised horizon line, Mill on the Tiber (ca. 1650)

Fig. 9. Photomicrograph of incised horizon line, Mill on the Tiber (ca. 1650)

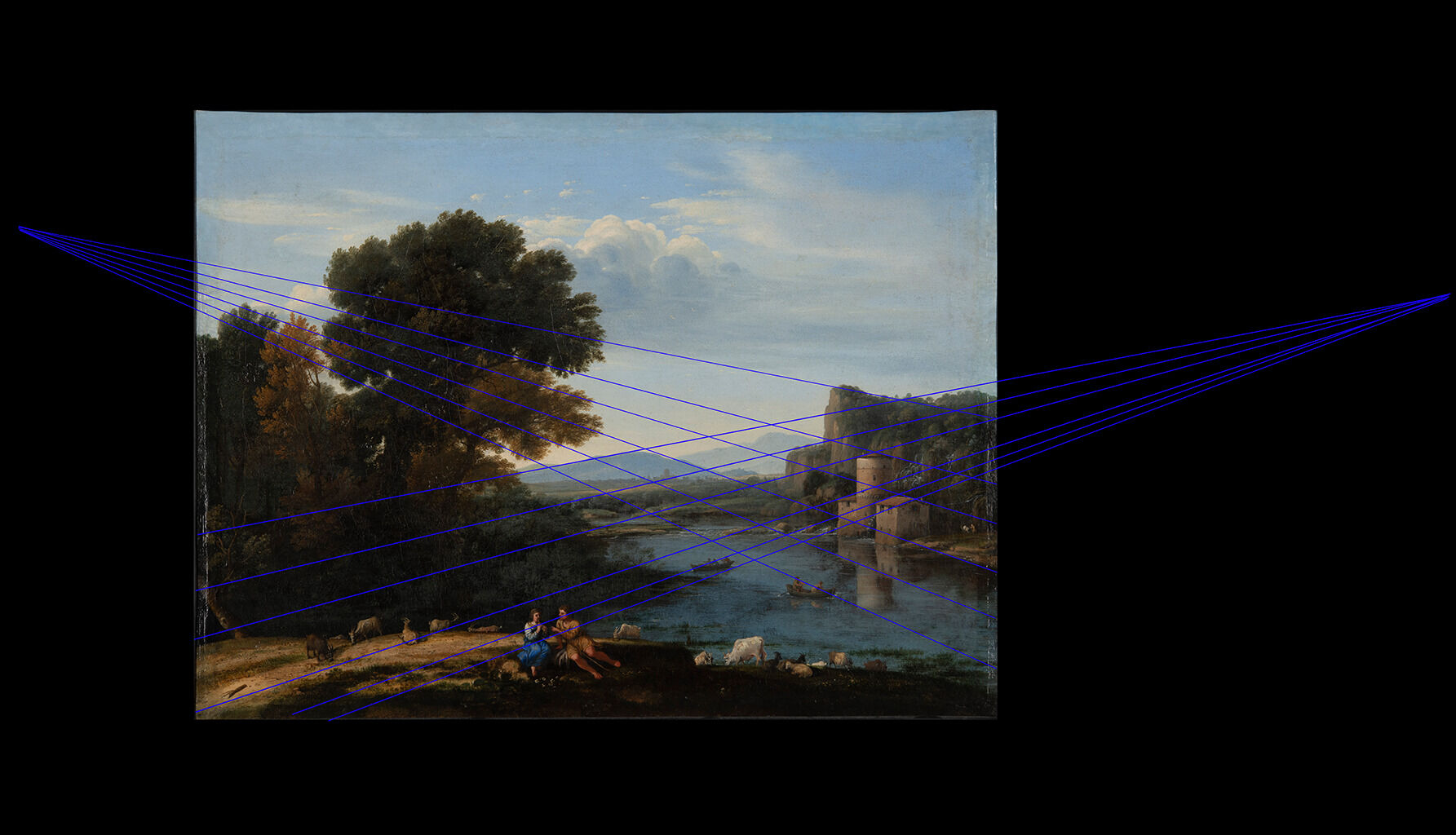

Fig. 10. Perspective diagram illustrating vanishing points that extend past the picture plane of Mill on the Tiber (ca. 1650)

Fig. 10. Perspective diagram illustrating vanishing points that extend past the picture plane of Mill on the Tiber (ca. 1650)

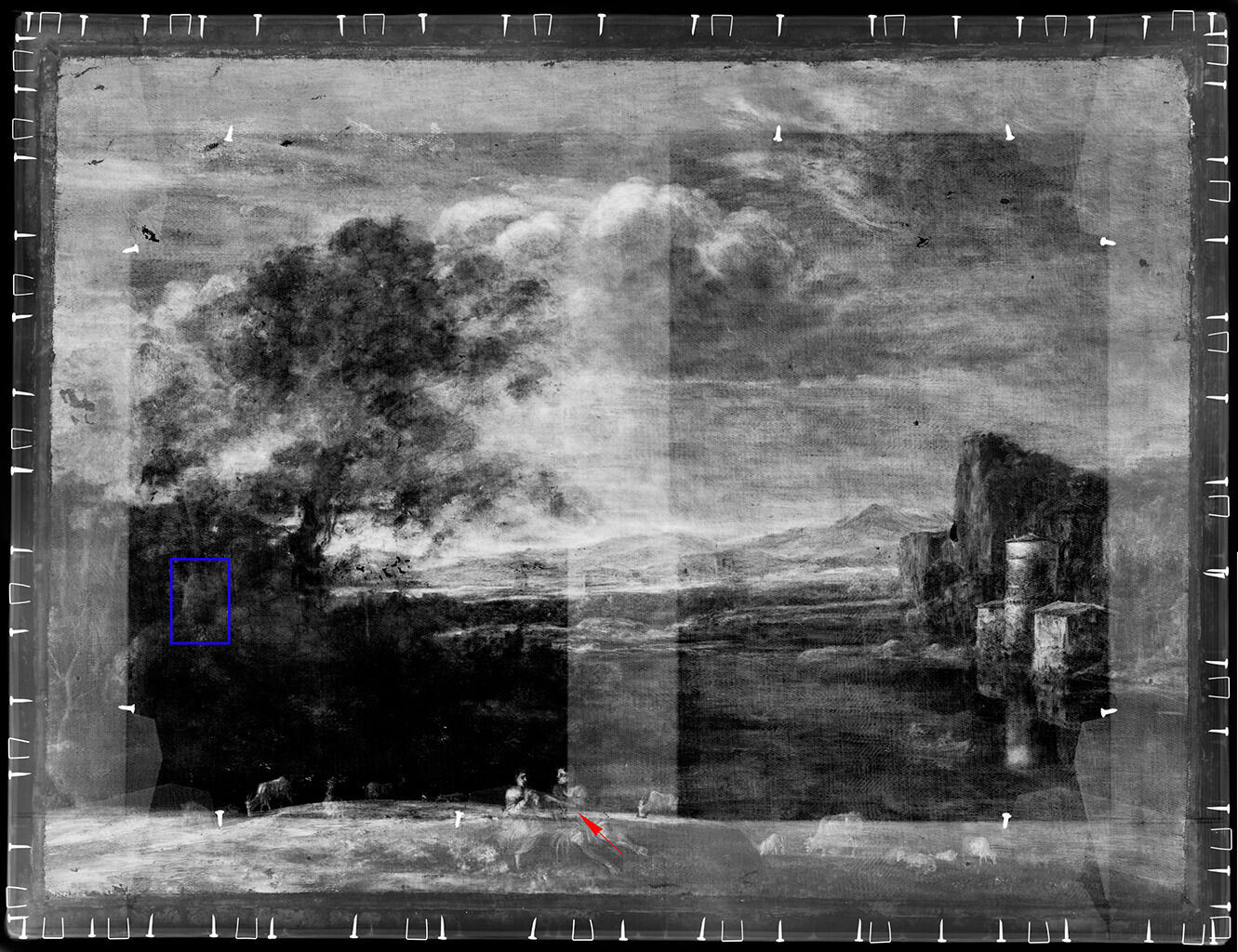

Fig. 11. X-radiograph of Mill on the Tiber (ca. 1650), with a blue box around a possible artist change of a tree trunk and a red arrow indicating the landscape application beneath the figures

Fig. 11. X-radiograph of Mill on the Tiber (ca. 1650), with a blue box around a possible artist change of a tree trunk and a red arrow indicating the landscape application beneath the figures

Fig. 13. Detail of a figure in a window, Mill on the Tiber (ca. 1650)

Fig. 13. Detail of a figure in a window, Mill on the Tiber (ca. 1650)

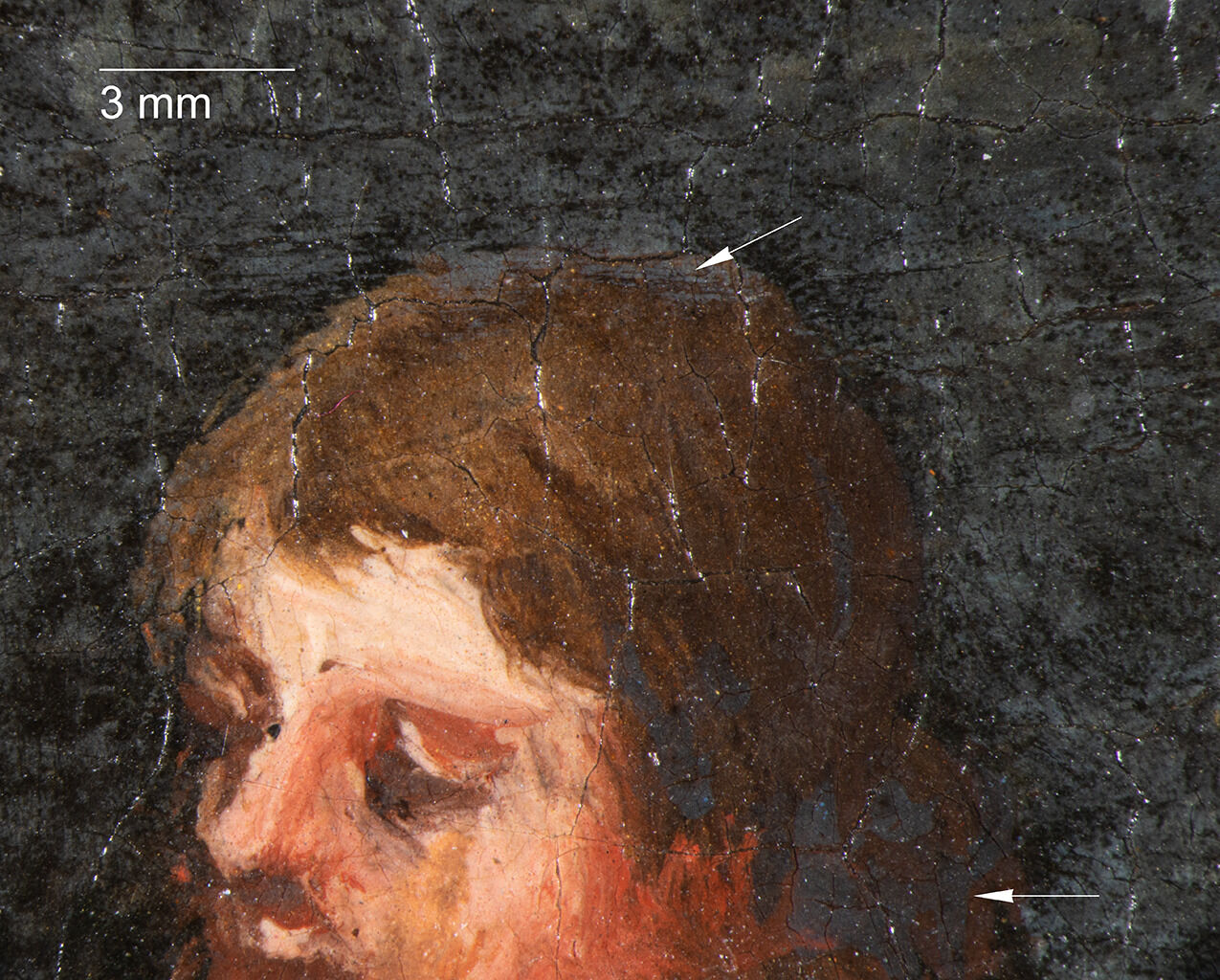

Fig. 14. Photomicrograph of blanching crossing the hair of the main male figure, Mill on the Tiber (ca. 1650)

Fig. 14. Photomicrograph of blanching crossing the hair of the main male figure, Mill on the Tiber (ca. 1650)

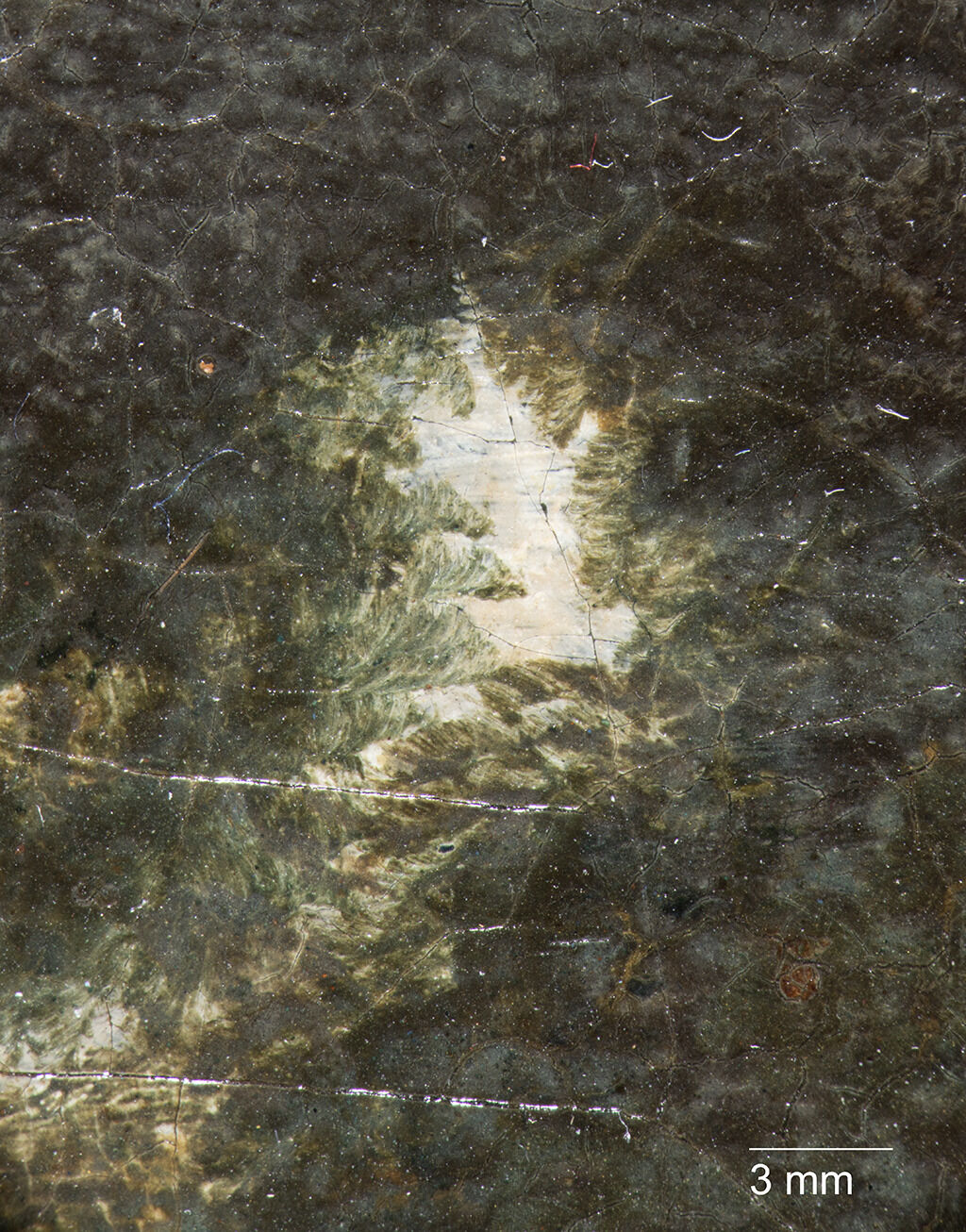

Both Claude paintings in the Nelson-Atkins collection were studied to determine possible causes of this blanching. Comparative samples were taken in blanched and non-blanched regions of various colors, and cross sections were prepared to study the alteration. Their various strata were examined with the optical microscope. Elemental compositions were obtained in the scanning electron microscope (SEM)scanning electron microscopy (SEM): Performed on a microsample of paint, the SEM provides a means of studying particle shapes beyond the magnification limits of the light microscope. This becomes increasingly important with the painting materials introduced in the early modern era, which are finer and more diverse than traditional artists’ materials. The SEM is routinely used in conjunction with an X-ray spectrometer, so that elemental identifications can be made selectively on the same minute scale as the electron beam producing the images. SEM methods are particularly valuable in studying unstable pigments, adverse interactions between incompatible pigments, and interactions between pigments and surrounding paint medium, all of which can have profound effects on the appearance of a painting., paying particular attention to the alteration of pigments and the formation of deterioration products atop the layers. In addition, regions of Mill on the Tiber were scanned with X-ray fluorescence elemental mapping (MA-XRF)X-ray fluorescence spectrometry elemental mapping (MA-XRF) or XRF elemental mapping: A non-destructive technique that entails collecting thousands of X-ray fluorescence spectra at regular intervals across a painting to build an alternate set of images depicting the locations and amounts of different elements. Although the information is fundamentally the same as measurements gathered from a single-point XRF, the graphical nature of the result is often a more powerful technique for understanding trends in an artist’s use of materials. The high number of spectra allows statistical manipulations of the elemental information to locate correlations between different pigments that would not be possible from a small number of tests. For example, the consistent occurrence of mercury along with chromium, and iron along with copper, could show that vermilion was used to mute the chrome green and red ocher was similarly employed in a mixture that includes emerald green. The resulting correlation maps then serve to show where the two cases occur in the composition. MA-XRF can also reveal preliminary paint applications that became covered as the composition was completed, thereby disclosing aspects of the painter’s method.. The combined results of elemental analyses in the SEM localized in individual layers, elemental distributions mapped over the painting surface, and optical microscopy of paint samples allowed a partial palette to be identified.10John Twilley, “Blanching Phenomena, Pigment Analyses, and XRF Elemental Mapping Results for Claude Gellée’s Mill on the Tiber, ca. 1650, #32-78,” unpublished scientific report, NAMA conservation file, January 7, 2024.

The majority of pigment particles throughout the painting are small in size, sometimes causing complications in the identification of pigments. While metal soaps were not abundant on this painting or Landscape with a Piping Shepherd, reaction products of lead with chloride and sulfate were often found atop the paint layer. The combination of fine particles with high surface area and lead mobilization to form these reaction products on the surface may have been the cause of blanching. In addition, the use of pre-industrial cleaning products, such as alkaline soaps, during historical restorations may have supplied some of the reactants contributing to the whitish appearance. In the case of Mill on the Tiber, additional uneven cleaning techniques may have resulted in the localized removal of blanching or localized formation of blanching (Fig. 15).

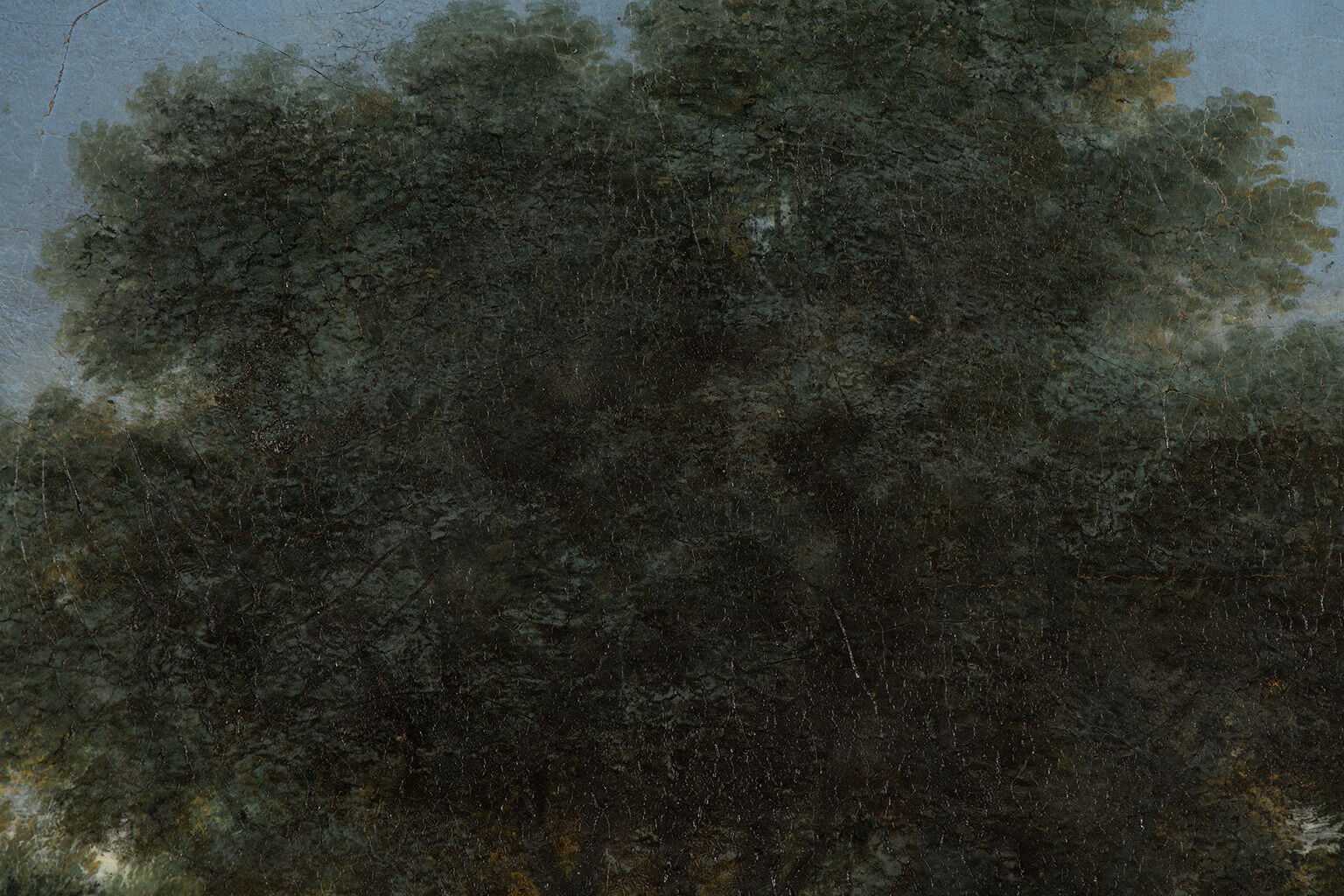

The painting has an elaborate restoration and conservation history, making it unclear precisely how it appeared when it was first completed. The earliest documented conservation treatment dates to 1942/1943, when the painting was cleaned and relined with wax by James Roth.12James Roth, September 11, 1943, treatment report, NAMA conservation file, 32-78.,13A document in the NAMA curatorial file also mentions a 1933 treatment of a Claude Lorraine [sic] painting, which was cleaned by M. J. Rougeron, a paintings restorer based in New York. However, it is not specified by title which Claude Lorrain painting was treated, Mill on the Tiber (32-78) or Landscape with a Piping Shepherd (31-57). The painting was subsequently cleaned from 1980 to 1982 by Forrest Bailey.14Forrest R. Bailey, September 11, 1980, and September 2, 1982, treatment reports, NAMA conservation file, 32-78. Photographs captured during Bailey’s treatment document that original paint had been overpaintedoverpaint: Restoration paint that covers original paint that may or may not be damaged. Historically, overpaint has often been applied too broadly, altering the intended aesthetic of the painting and sometimes introducing conceptions foreign to the original artist, thereby altering our understanding of the work and the era to which it belongs. along the edges and was revealed during his cleaning. This original paint, however, appeared to be severely fragmented and was subsequently covered again during the 1982 treatment. Retouchingretouching: Paint application by a conservator or restorer to cover losses and unify the original composition. Retouching is an aspect of conservation treatment that is aesthetic in nature and that differs from more limited procedures undertaken solely to stabilize original material. Sometimes referred to as inpainting or retouch. and overpaint dating from this treatment do not match the milky or hazy appearance found within the adjacent foliage of the composition today, suggesting that the change in surface appearance has progressed over the forty-plus years since 1982. During that conservation campaign, a synthetic varnish was applied and appears to have darkened slightly.

Notes

-

Evidence of the twill weave is visible in x-radiography and in raking light.

-

Marcel Rothlisberger notes that the dimensions of the painting were altered sometime before 1837, which is when the current dimensions were first mentioned. Marcel Rothlisberger, Claude Lorrain: The Paintings (New York: Hacker Art Books, 1979), 303.

-

Beneath this incised line is perhaps a second, less prominent incised line.

-

Sheila McTighe, “Poussin’s Practice: A New Plea for Poussin as a Painter,” Kermes 27, nos. 94–95 (April–September 2014): 14.

-

For more information on Claude’s use of perspective, see Hubert Damisch, “Claude: A Problem in Perspective,” Studies in the History of Art 14 (1984): 29–44.

-

This component is not present in the final drawing in Liber Veritatis, a compilation of drawings the artist created to record his completed paintings. However, as that series of drawings was used to chronicle completed work, Claude would not have included changed elements of the original composition.

-

There are few cracks in this area; however, it appears there is a dark layer present below the paint for the sky in this clearing.

-

Humphrey Wine, Claude: The Poetic Landscape (London: National Gallery, 1994), 12–13.

-

The signature is found in the landscape to the right of the male figure and reads “Claudio 1650” in stylized lettering appearing as “CLꜶDIO.”

-

John Twilley, “Blanching Phenomena, Pigment Analyses, and XRF Elemental Mapping Results for Claude Gellée’s Mill on the Tiber, ca. 1650, #32-78,” unpublished scientific report, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, January 7, 2024.

-

Karin Groen, “Scanning Electron-Microscopy as an Aid in the Study of Blanching,” in The Hamilton Kerr Institute Bulletin Number 1: The First Ten Years; The Examination and Conservation of Paintings 1977 to 1987, ed. Ian McClure (Cambridge: Hamilton Kerr Institute of the Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge, 1988), 49.

-

James Roth, September 11, 1943, treatment report, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, 32-78.

-

A document in the Nelson-Atkins curatorial file also mentions a 1933 treatment of a Claude Lorraine [sic] painting, which was cleaned by M. J. Rougeron, a paintings restorer based in New York. However, it is not specified by title which Claude Lorrain painting was treated, Mill on the Tiber (32-78) or Landscape with a Piping Shepherd (31-57).

-

Forrest R. Bailey, September 11, 1980, and September 2, 1982, treatment reports, NAMA conservation file, 32-78.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson and Brigid M. Boyle, “Claude Gellée, called Le Lorrain, Mill on the Tiber, ca. 1650,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.206.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier, and Brigid M. Boyle. “Claude Gellée, called Le Lorrain, Mill on the Tiber, ca. 1650,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.206.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson and Brigid M. Boyle, “Claude Gellée, called Le Lorrain, Mill on the Tiber, ca. 1650,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.206.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier, and Brigid M. Boyle. “Claude Gellée, called Le Lorrain, Mill on the Tiber, ca. 1650,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.206.4033.

Commissioned by Signor Lorette, Italy, ca. 1650 [1];

With Giuseppe de Rosis, Rome, by December 1, 1663;

Purchased from Giuseppe de Rosis, Rome, by Don Antonio Ruffo (1610–78), 1st Principe della Scaletta, Messina, Italy, by December 1, 1663–December 26, 1673 [2];

Given to his son, Don Placido Ruffo (1646–1710), 2nd Principe della Scaletta and 1st Principe della Floresta, Messina, Italy, 1673–May 5, 1710 [3];

Probably by descent to his son, Don Antonio Ruffo e La Rocca (ca. 1680–1739), 3rd Principe della Scaletta and 2nd Principe della Floresta, Messina, Italy, 1710–39;

Probably by descent to his son, Don Calogero Ruffo (ca. 1706–43), 4th Principe della Scaletta and 3rd Principe della Floresta, Messina, Italy, 1739–43;

Probably estate of Don Calogero Ruffo, ca. 1743–50 [4];

Probably by inheritance to his uncle, Don Giovanni Ruffo e La Rocca (ca. 1684–ca. 1755/1756), 5th Principe della Scaletta, Messina, Italy, 1750–1755/1756 [5];

Probably by descent to his son, Don Antonio Ruffo (1707–78), 6th Principe della Scaletta, Messina, Italy, 1755/1756–October 15, 1778;

Probably by descent to his son, Don Giovanni Ruffo (1751–1808), 7th Principe della Scaletta, Messina, Italy, 1778–March 11, 1808 [6];

With Philip Hill, London, by July 3, 1811 [7];

Probably Lord Charles Kinnaird (1780–1826), 8th Lord Kinnaird of Inchture, Scotland, by late 1812 [8];

Probably purchased from Lord Kinnaird by John Glover (1767–1849), London and Patterdale, UK, by January 1, 1813–36 [9];

Jointly purchased from Glover, through John Lord and George Stanley, by John Smith and Robert Hume, London, Smith stock book A 1822–ca. 1850, no. 1071, as Compn Shepherd and Shepherdess Even, by September 6, 1836–38 [10];

Purchased from Smith and Hume by William Hornby (1797–1869), The Hook, Hampshire, UK, April 18, 1838;

Bought back from Hornby by John Smith and Sons, London, stock book A 1822–ca. 1852, no. 1394, by 1839 [11];

Purchased from John Smith and Sons by Sir Thomas Baring (1772–1848), 2nd Baronet, London, May 10, 1839–April 3, 1848 [12];

Purchased by his son, Thomas Baring (1799–1873), London, 1848–November 18, 1873 [13];

By descent to his nephew, Thomas George Baring (1826–1904), 1st Earl of Northbrook, London, 1873–November 15, 1904 [14];

By descent to his son, Francis George Baring (1850–1929), 2nd Earl of Northbrook, London, 1904–at least 1926 [15];

With Durlacher Brothers, London, by September 9, 1930 [16];

Transferred to Durlacher Brothers, New York, by December 9, 1930–December 17, 1931 [17];

Purchased from Durlacher Brothers, through Harold Woodbury Parsons, by The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1931.

Notes

[1] An inscription on the verso of no. 123 in Claude’s Liber Veritatis, the book of drawings he used to record his painting compositions, indicates that Mill on the Tiber was undertaken for a certain “Signor Lorette.” (John Smith erroneously identifies Claude’s patron as “Signor Piretti” in his 1837 catalogue raisonné, a mistake that was repeated by later scholars. Elsewhere the patron is incorrectly referred to as Parette and Torette/i.) Nothing is known about Lorette, though Marcel Rœthlisberger believes he was a minor patron, given the small size of the picture and the one-off nature of the commission; see Marcel Rœthlisberger, Claude Lorrain: The Paintings (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1961), 302.

[2] Extant correspondence between Ruffo and his agents in Rome attests to this purchase. Vincenzo Ruffo, “Galleria Ruffo nel secolo XVII in Messina (con lettere di pittori ed altri documenti inediti),” Bollettino d’Arte 10, nos. 5–6 (May–June 1916): 192, as Paesaggio con due figure ed alcune capre.

[3] Furthermore, these pictures were part of Don Antonio’s propter nuptias (marriage gift) to his son Don Placido, principe of Floresta, which was finalized on December 26, 1673. In Vincenzo Ruffo’s compilation of his family’s inventories, he sets off the paintings given as wedding gifts with asterisks. See Vincenzo Ruffo, “Galleria Ruffo nel secolo XVII in Messina (con lettere di pittori ed altri documenti inediti),” Bollettino d’Arte 10, nos. 9–10 (September–October 1916): 314, 316, in the “Catalogo generale dei 364 quadri della galleria,” where the paintings are number 108*: “Lorenese (Claudio il), Paesaggio con due figure ed alcune capre, 2-1/2 x 3 ; La nascita del Sole, 2 1/2 x 3.”

[4] In 1743, Don Calogero (eldest son of the younger Don Antonio) died childless, causing problems of succession between his sister, Antonia Ruffo, and uncle, Don Giovanni Ruffo e La Rocca (the younger Don Antonio’s brother). Don Giovanni got the title of 5th Principe della Scaletta and the Palazzo Regio Campo in Messina, which included the Claude paintings; Donna Antonia Ruffo got the title of Principessa della Floresta. See Rosanna De Gennaro, “Aggiunta alle notizie sulla collezione di Antonio Ruffo: ‘nota di quadri vincolati in primogeniture’ scampati al terremoto del 5 febbraio 1783,” Napoli nobilissima 2, no. 5/6 (September–December 2001): 211.

[5] See note 4.

[6] See “Note of paintings bound in primogeniture, recovered by Don Giovanni Ruffo, prince della Scaletta from the ruins of the palace which fell in Messina with the horrible earthquake of 5 February 1783,” where two Claude paintings are listed as nos. 85–86 and located in the chapel: “Due paesini, di palmi 2 1/2 e 3, di monsieur Claudio Lorenese, onze 40.” These are probably Mill on the Tiber and Landscape with a Piping Shepherd. See De Gennaro, “Aggiunta alle notizie sulla collezione di Antonio Ruffo,” 213–14.

Edward Dillon, Claude (London: Methuen, 1905), 187, alleges that Mill on the Tiber was purchased from the Colonna Palace in Rome by William Young Ottley, Esq. (1771–1836) in 1798 or 1799, who had it until at least May 16, 1801. Ottley bought Ascanius Shooting at Silvia’s Stag from the Colonna Palace but appears to have purchased a different Mill on the Tiber from the Corsini Palace, also in Rome. See A Catalogue of The Superb, Capital, and Truly Valuable Collection of Celebrated Italian Pictures, Lately Purchased from the Colonna, Borghese, and Corsini Palaces, etc. by William Young Ottley, Esq., Forming an Unrivalled Assemblage of the Genuine and Finest Works of the Italian Schools (London: Christie’s, May 16, 1801), 6, as Landscape, with Pastoral Figures, Afternoon, View on the Tiber, in his finest manner, and in the highest Preservation; a Cabinet Picture, from the Corsini Palace. A copy of the catalogue at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, is annotated as “Goats & Shephds. Fine Tree & Blue Sky” and purchased by a “Lord D.” It is unlikely that this is the Nelson-Atkins painting.

[7] The dealer Philip Hill consigned Mill on the Tiber to a Christie’s sale, but it was bought in for 390 guineas; see A Choice and Highly Valuable Assemblage of Exquisite Cabinet Dutch Pictures, Christie, Manson, and Woods, London, July 3, 1811, lot 105, View on the Banks of the Tiber.

[8] On January 1, 1813, the English landscape painter Joseph Farington (1747–1821) noted in his diary that John Glover “had lately given 1700 guineas for two pictures painted by Claude.” David Hansen proposes that it’s “feasible” that Glover purchased both Mill on the Tiber and Landscape with a Piping Shepherd from Kinnaird in late 1812; see David Hansen, John Glover and the Colonial Picturesque, exh. cat. (Hobart, Tasmania: Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, 2003), 135. It is unclear whether Glover purchased them together or separately. Landscape with a Piping Shepherd was likely owned by Lord Charles Kinnaird (1780–1826) in 1812, but the ownership of Mill on the Tiber is less clear. Either Philip Hill still owned the picture, or he found a private buyer after it failed to sell at auction. Hansen also confirmed that the prices Glover paid for the pictures varied between sources. See email from Dr. David Hansen, Australian National University, to Glynnis Stevenson, NAMA, April 20, 2021, NAMA curatorial files.

[9] See note 8.

On September 4, 1830, John Glover emigrated with his family to Van Diemen’s Land (now Tasmania). Prior to this, Mill on the Tiber was bought in at his emigration sale of May 12, 1830, for 700 guineas; see John Smith, A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch, Flemish, and French Painters (London: Smith and Son, 1837), 8:258. According to the same source, Mill’s pendant Landscape with a Piping Shepherd was also bought in by John Glover in 1830 for 700 guineas. Smith, A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch, Flemish, and French Painters, 8:289. It seems evident that George Stanley, in his capacity as auctioneer, bought in the pictures on John Glover’s behalf, likely before giving them to the artist’s son-in-law and London agent, John Lord (1795–1854). They remained in Lord’s custody until at least July 1835, when the exhibition of Glover’s work (and his two Claudes) closed.

[10] See letter from John Smith, London, to John Mountjoy Smith, Rome, September 6, 1836, in Charles Sebag-Montefiore and Julia I. Armstrong-Totten, A Dynasty of Dealers: John Smith and Successors 1801–1924; A Study of the Art Market in Nineteenth-Century London (London: Roxburghe Club, 2013), 219–21. Smith and Hume paid £1840 for Landscape with a Piping Shepherd and Mill on the Tiber. See also “Records of John Smith and successors, 1812–1892,” daybook 3, part 1, 1837–1847, p. 93, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles.

[11] Sebag-Montefiore and Armstrong-Totten, A Dynasty of Dealers, 220n111.

[12] Baring purchased Mill on the Tiber for £600. See Sebag-Montefiore and Armstrong-Totten, A Dynasty of Dealers, 220n111; and “Records of John Smith and successors, 1812–1892,” daybook 3, part 1, 1837–1847, p. 175, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles.

[13] Sir Thomas Baring’s will stipulated that his collection be sold after his death. Thomas Baring purchased his father’s Italian, Spanish, and French pictures when they were put up for sale; see the introduction to A Descriptive Catalogue of the Collection of Pictures Belonging to the Earl of Northbrook (London: Griffith, Farran, Okeden, and Welsh, 1889), unpaginated.

[14] Thomas George Baring was the eldest son of Thomas Baring’s older brother, Francis Thornhill Baring (1796–1866), 1st Baron Northbrook. He succeeded his father in 1866 as the 2nd Baron Northbrook and became 1st Earl of Northbrook in 1876; see Sebag-Montefiore and Armstrong-Totten, A Dynasty of Dealers, 65.

[15] See Louis Hourticq et al., Le Paysage Français de Poussin à Corot à l’Exposition du Petit Palais, exh. cat. (Paris: Éditions de la Gazette des Beaux-Arts, 1926), 115. The painting likely remained in Francis George Baring’s collection until his death on April 12, 1929.

In the catalogue raisonné, Marcel Rœthlisberger erroneously states that the painting was in the possession of Colnaghi, London, by 1929/1930; see Marcel Rœthlisberger, Claude Lorrain: The Paintings (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1961), 304. However, researchers have not found evidence of the two Nelson-Atkins canvases in the Colnaghi archives. See email from Catherine Taylor, Head of Archives and Records, Waddesdon Manor, to Glynnis Stevenson, NAMA, April 22, 2021, NAMA curatorial files.

[16] See letters from Harold Woodbury Parsons, art advisor for the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, to J. C. Nichols, Trustee for the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, September 9, 1930, and November 22, 1930, NAMA curatorial files.

[17] See letter from Harold Woodbury Parsons to Robert A. Holland, curator of collections, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, December 9, 1930, NAMA curatorial files.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson and Brigid M. Boyle, “Claude Gellée, called Le Lorrain, Mill on the Tiber, ca. 1650,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.206.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier, and Brigid M. Boyle. “Claude Gellée, called Le Lorrain, Mill on the Tiber, ca. 1650,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.206.4033.

Possibly Claude Gellée (Claude Lorrain), The Sea of Galilee with Christ Calling Peter and Andrew, 1665, oil on canvas, possibly 19 11/16 x 25 9/16 in. (50 x 65 cm), now lost; see Claude Gellée (Claude Lorrain), The Sea of Galilee with Christ calling Peter and Andrew (Matthew, IV, 18 and Mark, I, 16f), record of painting (whereabouts unknown) from the Liber Veritatis, 1665, pen and brown ink on paper, 7 5/8 x 10 in. (19.5 x 25.4 cm), Liber Veritatis, no. 165, British Museum, London, 1957,1214.171.

Claude Gellée (Claude Lorrain), Landscape with a Piping Shepherd, 1667, oil on canvas, 20 1/2 x 27 3/8 in. (52.1 x 69.5 cm), The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 31-57.

Preparatory Work

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson and Brigid M. Boyle, “Claude Gellée, called Le Lorrain, Mill on the Tiber, ca. 1650,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.206.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier, and Brigid M. Boyle. “Claude Gellée, called Le Lorrain, Mill on the Tiber, ca. 1650,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.206.4033.

Claude Gellée (Claude Lorrain), Figure study for a pastoral landscape; a woman seated playing a musical instrument, a herdsman beside her, 1650–51, black chalk, brown wash; Verso: The same herdsman, holding a staff, black chalk, 6 1/8 x 9 in (15.5 x 22.9 cm), British Museum, London, Oo,7.141.

Copies

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson and Brigid M. Boyle, “Claude Gellée, called Le Lorrain, Mill on the Tiber, ca. 1650,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.206.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier, and Brigid M. Boyle. “Claude Gellée, called Le Lorrain, Mill on the Tiber, ca. 1650,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.206.4033.

Claude Gellée (Claude Lorrain), Pastoral Landscape, Record of a Painting in Kansas City (Missouri), William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art, from the Liber Veritatis; two figures seated on a rock in the center foreground, goats nearby, two boats on a river with trees on the left bank, buildings and cliffs towards the right, ca. 1650, pen and brown ink, with brown and gray wash on paper, 7 5/8 x 10 in. (19.4 cm x 25.4 cm), Liber Veritatis, no. 123, British Museum, London, 1957,1214.129.

Richard Earlom (English, 1743–1822), after Claude Gellée (Claude Lorrain), The Mill on the Tiber, 1776, etching with mezzotint, plate: 8 1/4 x 10 1/4 in. (20.9 x 26 cm), sheet: 10 1/4 x 16 7/8 in. (26 x 42.8 cm), The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, Purchase: acquired through the Print Duplicate Fund, 68–6/1.

John Glover (English, 1767–1849), after Claude Gellée (Claude Lorrain), Mill on the Tiber, ca. 1840, oil on canvas, 30 x 45 in. (76 x 114 cm), sold at Important Australian and International Art, Menzies, South Yarra, Australia March 27, 2024), lot 39, as Mill on the Tiber (after Claude), http://www.menziesartbrands.com/items/20599.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson and Brigid M. Boyle, “Claude Gellée, called Le Lorrain, Mill on the Tiber, ca. 1650,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.206.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier, and Brigid M. Boyle. “Claude Gellée, called Le Lorrain, Mill on the Tiber, ca. 1650,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.206.4033.

Possibly Mr. Glover’s Exhibition, 16, Old Bond Street, London, opened April 24, 1820, no cat.

Possibly Mr. Glover’s Exhibition, 16, Old Bond Street, London, May–June 1821, no cat.

Possibly Glover’s Exhibition, 16, Old Bond Street, London, 1823, no. 65 or 84, as either One of the most beautiful pictures or Landscape.

Pictures, Descriptive of the Scenery, and Customs of the Inhabitants of Van Dieman’s Land, Together with Views in England, Italy, etc. Painted by John Glover, Esq.; To Which are Added Two Genuine, and Highly Finished Landscapes, by the Celebrated Claude Lorraine [sic], 106 New Bond Street, London, June–July 1835, no. 68 or 69, as Two Landscapes by Claude Lorraine [sic].

Exhibition of Works by the Old Masters and by Deceased Masters of the British School; Including a Special Selection from the Works of Frank Holl, R. A., and a Collection of Water-Colour Drawings by Joseph M. W. Turner, R. A., Winter Exhibition, Royal Academy, London, January 7–March 16, 1889, no. 85, as Shepherd Teaching a Shepherdess to Play on the Pipe.

Exhibition of Works by the Old Masters Including a Special Collection of Paintings and Drawings by Claude, Winter Exhibition, Royal Academy, London, January 6–March 15, 1902, no. 56, as A Shepherd and Shepherdess.

Old Masters: XVII. and XVIII. Century French Art; Contemporary British Painting and Sculpture, Spring Exhibition, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, February 8–April 3, 1907, no. 34, as The Music Lesson.

Exposition du Paysage Français de Poussin à Corot, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Paris, May–June 1925, no. 120, as Moulin sur le Tibre.

Paintings Owned by W. R. Nelson Trust, Kansas City Art Institute, by January 17–May 20, 1932, unnumbered, as The Mill on the Tiber.

Exhibition of French Painting from the Fifteenth Century to the Present Day, California Palace of the Legion of Honor, San Francisco, June 8–July 8, 1934, no. 14, as The Mill on the Tiber.

An Exhibition of Paintings and Drawings of Claude Lorrain, 1600–1682, Durlacher Brothers, New York, January 19–February 12, 1938, no. 2, as The Mill on the Tiber.

Landscapes of the European War Theatre, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, January 1–February 13, 1944, no cat.

Landscape: An Exhibition of Paintings, Brooklyn Museum of Art, NY, November 8, 1945–January 1, 1946, no. 30, as The Mill on the Tiber.

Fiftieth Exhibition of the Art of Europe during the XVIth–XVIIth Centuries, Worcester Art Museum, April 11–May 16, 1948, no. 15, as The Mill on the Tiber.

Twenty Years of Collecting, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, December 11–31, 1953, no cat., as Mill on the Tiber.

Claude Lorrain, 1600–1682: A Tercentenary Exhibition, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, October 17, 1982–January 2, 1983; Galeries nationales du Grand Palais, Paris, February 15–May 16, 1983, no. 40, as The Mill on the Tiber.

John Glover and the Colonial Picturesque, Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, Hobart, Tasmania, Australia, November 28, 2003–February 1, 2004; Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, February 19–April 12, 2004; National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, April 24–July 18, 2004; National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, August 13–October 3, 2004, no. 1, as The Mill on the Tiber.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson and Brigid M. Boyle, “Claude Gellée, called Le Lorrain, Mill on the Tiber, ca. 1650,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.206.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier, and Brigid M. Boyle. “Claude Gellée, called Le Lorrain, Mill on the Tiber, ca. 1650,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.206.4033.

A Catalogue of a Choice and Highly Valuable Assemblage of Exquisite Cabinet Dutch Pictures, Being the Select and Remaining Part of the Collection of a Gentleman of Refined Taste Purchased from nearly all the distinguished Cabinets that have been offered for Sale for many Years past in this Country; and including several Valuable Purchases made on the Continent; Among Them Are Specimens of the First Degree of Merit, By Corregio, Garofalo, Guido, Domenichino, Albano, Poussin, Claude, Teniers, Cuyp, Potter, Berchem, Wouvermans, A. V. de Velde, Ostade, Du Jardin, Hobbema, Brekelcamp, Mignon, Wilson ([London]: Christie, July 3, 1811), 12, as An elegant Landscape, View on the Banks of the Tiber.

Liber veritatis, or, A collection of prints, after the original designs of Claude le Lorrain: in the collection of His Grace the duke of Devonshire; executed by Richard Earlom, in the manner and taste of the drawings; to which is added, a descriptive catalogue of each print; together with the names of those for whom, and the places for which, the original pictures were first painted, taken from the hand-writing of Claude le Lorrain on the back of each drawing, and of the present possessors of many of the original pictures (1819; repr., London: Boydell, [1841?]), 2:4, as A Shepherd teaching a Shepherdess to play on a pipe. The scene exhibits a woody and well watered Landscape, with a Mill and a round Tower at its base.

Possibly “Mr. Glover’s Exhibition,” Literary Chronicle and Weekly Review, no. 106 (May 26, 1821), 334.

Possibly “Mr. Glover’s Exhibition,” Repository of Arts, Literature, Fashions, Manufactures, etc. 11, no. 66 (June 1, 1821): 374.

Probably “Fine Arts: Mr. Glover’s Pictures,” New Monthly Magazine 9 (1823): 397.

“Sales by Auction: Mr. Glover’s Pictures, and Landscapes by Claude,” Times (London), no. 14,209 (April 24, 1830): 4.

“Sales by Auction: Mr. Glover’s Pictures, and Landscapes by Claude,” Times (London), no. 14,213 (April 29, 1830): 4.

A Catalogue of Sixty Pictures Painted by John Glover, Esq., and Two Landscapes by Claude, His Property ([London]: [Stanley], April 29, 1830), 6, as Landscape with a Mill.

A Catalogue of Pictures, Descriptive of the Scenery, and Customs of the Inhabitants of Van Dieman’s Land, Together with Views in England, Italy, etc. Painted by John Glover, Esq.; To Which are Added Two Genuine, and Highly Finished Landscapes, by the Celebrated Claude Lorraine [sic], exh. cat. (1835; repr. London: J. Rogers, 1868), 4, as Two Landscapes.

John Smith, A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch, Flemish, and French Painters, vol. 8, The Life and Works of Nicholas Poussin, Claude Lorraine [sic], and Jean Baptiste Greuze (London: Smith and Son, 1837), 258, 471, as A Shepherd teaching a Shepherdess to play on the Pipe.

Frederick Christian Lewis, Liber Studiorum of Claude Lorrain (London: F. C. Lewis, 1840).

John Smith, Supplement to the Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch, Flemish, and French Painters; In which is included a short Biographical Notice of the Artists, with a Copious Description of Nearly The Whole of Their Pictures; A Statement of The Price At Which Such Pictures Have Been Sold At Public Sales On The Continent And In England; A Reference To The Galleries and Private Collections, In Which A Large Portion Are At Present; And The Names Of The Artists By Whom They Have Been Engraved To Which Is Added, A Brief Notice Of The Scholars And Imitators Of The Great Masters Of The Above Schools, pt. 9 (London: Mssrs. Smith, 1842), 808, as A Shepherd teaching a Shepherdess to play on the Pipe.

John Mitford, ed., “Obituary–Mr. John Glover,” Gentleman’s Magazine (July 1850): 97.

[Gustav Friedrich] Waagen, Treasures of Art in Great Britain: Being an Account of the Chief Collections of Paintings, Drawings, Sculptures, Illuminated Mss., etc. (London: John Murray, 1854), 2:177.

[Emilia Francis Strong Dilke], Claude Lorrain: Sa Vie et ses Œuvres d’après des documents inédits (Paris: J. Rouam, 1884), 217, 233, as Moulin sur le Tibre.

Owen J. Dullea, Claude Gellée le Lorrain (London: S. Low, Marston, Searle, and Rivington, 1887), 112, 125, as Landscape with broad river and water-mill.

Exhibition of Works by the Old Masters and by Deceased Masters of the British School; Including a Special Selection from the Works of Frank Holl, R. A., and a Collection of Water–Colour Drawings by Joseph M. W. Turner, R. A., exh. cat. (London: William Clowes and Sons, 1889), 22, 69–70, as Shepherd Teaching a Shepherdess to Play on the Pipe.

W. J. James Weale and Jean Paul Richter, A Descriptive Catalogue of the Collection of Pictures Belonging to the Earl of Northbrook: The Dutch, Flemish, and French Schools by Mr. W.H. James Weale; The Italian and Spanish Schools By Dr. Jean Paul Richter (London: Griffith, Farran, Okeden, and Welsh, 1889), 188, 192, 216, as A Shepherd Teaching a Shepherdess to play on the Pipe and The Music Lesson.

Exhibition of Works by the Old Masters Including a Special Collection of Paintings and Drawings by Claude, exh. cat. (London: William Clowes and Sons, 1902), 17, as A Shepherd and Shepherdess.

H. C., “Correspondance d’Angleterre: Exposition de maîtres anciens à la Royal Academy (Suite),” La Chronique des arts et de la curiosité: supplément à la Gazette des beaux-arts, no. 11 (March 15, 1902): 85.

Verlags-Katalog von Franz Hanfstængl Kunstverlag München (Munich: Franz Hanfstængl, 1903), 2:56, as Ein Schäfer lehrt eine Schäferin auf einer Pfeife.

Raymond Bouyer, Les grands artistes: Leur vie—leur œuvre; Claude Lorrain (Paris: Henri Laurens, [1905]), 77, 126, (repro.), as Le Moulin sur le Tibre.

Edward Dillon, Claude (London: Methuen, 1905), 187, as Mill by the Tiber.

Masters in Art: A Series of Illustrated Monographs (Boston: Bates and Guild, 1905), 6:377, as Mill on the Tiber.

Spring Exhibition: Section I.—Old Masters: XVII. and XVIII. Century French Art; Section II. Contemporary British Painting and Sculpture, exh. cat. ([London]: Whitechapel Art Gallery, 1907), 7, as The Music Lesson.

The Masterpieces of Claude (1600–1682) (London: Gowans and Gray, 1911), 48, 67, (repro.), as Mill on the Tiber / Moulin sur le Tibre / Mühle am Tiber and Shepherd teaching shepherdess to play the flute (Mill on the Tiber).

Algernon Graves, A Century of Loan Exhibitions, 1813–1912 (New York: Burt Franklin, 1913), 1:179, as Shepherd and Shepherdess.

Probably Vincenzo Ruffo, “Galleria Ruffo nel secolo XVII in Messina (con lettere di pittori ed altri documenti inediti),” Bollettino d’Arte 10, nos. 5–6 (May–June 1916): 167n6, 175n2, 190, 192; nos. 7–8 (July–August 1916): 238; nos. 9–10 (September–October 1916): 316, as Paesaggio con due figure ed alcune capre.

Algernon Graves, Art Sales from Early in the Eighteenth Century to Early in the Twentieth Century: (mostly Old Master and Early English Pictures) (London: Algernon Graves, 1918), 1:110, as Landscape with Mill.

Basil S[omerset] Long, “John Glover: Born 1767, Died 1849,” Walker’s Quarterly, no. 15 (April 1924): 18, 47, as either One of the most beautiful pictures or Landscape.

Arthur M. Hind, The Drawings of Claude Lorrain (London: Halton and T. Smith, 1925), 13.

Henri Lapauze, Camille Gronkowski, and Adrien Fauchier-Magnan, Exposition du Paysage Français de Poussin à Corot, exh. cat. (Paris: Imprimerie Crété, 1925), 17, as Moulin sur le Tibre.

Robert De La Sizeranne, “Au Petit Palais: Le Paysage français de Poussin à Corot,” Revue Des Deux Mondes (1829–1971), Septième Période, 27, no. 3 (June 1, 1925): 670.

Arthur M. Hind, Catalogue of Drawings of Claude Lorrain preserved in the Department Preserved in the Department of Prints and Drawings with special reference to an exhibition including other masters of classical landscape, exh. cat. (London: British Museum, 1926), iv, xv, 21.

Louis Hourticq et al., Le Paysage Français de Poussin à Corot à l’Exposition du Petit Palais (Mai–Juin 1925), exh. cat. (Paris: Éditions de la Gazette des Beaux-Arts, 1926), 115, as Moulin sur le Tibre.

Possibly “Treasure in Lore of Art: ‘Read,’ says Parsons to Those Who Would Appreciate Works,” Kansas City Times 95, no. 10 (January 12, 1932): 2.

“Art News,” Kansas City Journal-Post, no. 224 (January 17, 1932): 2C.

“View New Nelson Art: Purchases for Gallery Inspected by Institute Trustees,” Kansas City Star 52, no. 122 (January 17, 1932): 8A, as Mill on the Tiber.

M[inna] K. P[owell], “In Gallery and Studio,” Kansas City Star 52, no. 128 (January 23, 1932): E, as Mill on the Tiber.

“Nelson Art Treasures Draw Admiring Throng: Thousands Flock to Temporary Exhibition of Paintings at the Kansas City Art Institute Every Day,” Weekly Kansas City Star 42, no. 48 (January 27, 1932): 4.

“Four Old Masters for Collection in Kansas City,” Art News 30, no. 18 (January 30, 1932): 12, as Mill on the Tiber.

“Kansas City Now Possesses Masterpieces by Poussin and Claude,” Art Digest 6, no. 10 (February 15, 1932): 32, (repro.), as The Mill on the Tiber.

“A Strong Home for Art: Father Gerrer, a Connoisseur, Visits the Nelson Gallery; That Kansas City Provides an Enduring Place for Treasures Greatly Satisfies Notre Dame and St. Gregory Director,” Kansas City Times 95, no. 47 (February 24, 1932): 6.

“M. Claudel in Rich Land: A Desire to See Harvest Expressed by Ambassador; The Visitor Goes to View the Kansas City Art Collection and Sees Some Works of His Countrymen,” Kansas City Times 95, no. 70 (March 22, 1932): 11.

“In Gallery and Studio,” Kansas City Star 53, no. 266 (June 10, 1933): 4.

F. A. Gutheim, “Claude Lorrain,” American Magazine of Art 26, no. 10 (October 1933): 460, (repro.), as Shepherd Teaching a Shepherdess the Pipes.

M[inna] K. P[owell], “Art Shows the Layman Something He is Unable to See for Himself; Masterpieces in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art Will Open New Vistas to Those With Unsatisfied Longings—Paintings Must Appeal to the Mind as Well as to the Eye—Curry Painted Courage and Loneliness and Peace Into His Picture of a Stark Little Prairie Farmhouse,” Kansas City Star 54, no. 49 (November 5, 1933): 8D.

Thomas Carr Howe, “Kansas City Has Fine Art Museum: Nelson Gallery Ranks with the Best,” [unknown newspaper] (ca. December 1933), clipping, scrapbook, NAMA Archives, vol. 5, p. 6.

“Nelson Gallery of Art Special Number,” Art Digest 8, no. 5 (December 1, 1933): 13, 21, as The Mill on the Tiber.

“American Art Notes,” Connoisseur 92, no. 388 (December 2, 1933): 419.

“The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art Special Number,” Art News 32, no. 10 (December 9, 1933): 28, 30, as The Mill on the Tiber.

Minna K. Powell, “The First Exhibition of the Great Art Treasures: Paintings and Sculpture, Tapestries and Panels, Period Rooms and Beautiful Galleries are Revealed in the Collections Now Housed in the Nelson-Atkins Museum—Some of the Rare Objects and Pictures Described,” Kansas City Star 54, no. 84 (December 10, 1933): 4C, as The Mill on the Tiber.

Luigi Vaiani, “Art Dream Becomes Reality with Official Gallery Opening at Hand: Critic Views Wide Collection of Beauty as Public Prepares to Pay its First Visit to Museum,” Kansas City Journal-Post, no. 187 (December 11, 1933): 7.

“Praises the Gallery: Dr. Nelson M’Cleary, Noted Artist, a Visitor; In a Visit to Nelson Collection the Former Kansas Citian Gives Warmest Approval to the Exhibits,” Kansas City Star 54, no. 98 (December 24, 1933): 9A.

Roger Fry, Characteristics of French Art (New York: Brentano’s, 1933), unpaginated, (repro), as Landscape.

The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Handbook of the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1933), 40, as The Mill on the Tiber.

Possibly A. J. Philpott, “Kansas City Now in Art Center Class: Nelson Gallery, Just Opened, Contains Remarkable Collection of Paintings, Both Foreign and American,” Boston Sunday Globe 125, no. 14 (January 14, 1934): 16.

M[inna] K. P[owell], “In Gallery and Studio,” Kansas City Star 54, no. 125 (January 20, 1934): 5.

“A Thrill to Art Expert: M. Jamot is Generous in his Praise of Nelson Gallery,” Kansas City Times 97, no. 247 (October 15, 1934): 7, as Mill on the Tiber.

“An Art Expert Praises a Nelson Gallery Acquisition,” Kansas City Star 55, no. 34 (October 21, 1934): 6, (repro.), as Mill on the Tiber.

Exhibition of French Painting from the Fifteenth Century to the Present Day, exh. cat. (San Francisco: California Palace of the Legion of Honor, 1934), 33, as The Mill on the Tiber.

“As Others See Us,” Kansas City Times 98, no. 147 (June 20, 1935): D, as Mill on the Tiber.

An Exhibition of Paintings and Drawings by Claude Lorrain, 1600–1682, exh. cat. (New York: Durlacher Brothers, 1938), unpaginated, as The Mill on the Tiber.

M[inna] K. P[owell], “In Gallery and Studio: News and Views of the Week in Art,” Kansas City Star 58, no. 119 (January 14, 1938): 15.

Edward Alden Jewell, “Notable Claude Lorrain Show,” New York Times 87, no. 29,215 (January 19, 1938): L21.

Edward Alden Jewell, “Gallery Displays Lorraine [sic] Pictures: First Exhibition of Early French Master in America Appears at Durlacher’s; Nine Canvases Are Hung; 14 Drawings Included in Show Offering Major Portion of U.S.-Owned Material,” New York Times 87, no. 29,217 (January 21, 1938): L17, as The Mill on the Tiber.

Jerome Klein, “Landscapes by Claude and Americans Shown: Durlacher Displays Art of Lorrain and Whitney Offers Native Work,” New York Post 137, no. 56 (January 22, 1938): 19, (repro.), as Mill on the Tiber.

Edward Alden Jewell, “A Century of Landscape: Whitney Exhibition Reveals Development in American Painting from 1800 to 1900; Claude Lorraine [sic],” New York Times 87, no. 29,219 (January 23, 1938): 9X, as The Mill on the Tiber.

M[inna] K. P[owell], “In Gallery and Studio: News and Views of the Week in Art,” Kansas City Star 58, no. 133 (January 28, 1938): 22, as The Mill on the Tiber.

Margaret Breuning, “Art in New York,” Parnassus 10, no. 2 (February 1938): 22, (repro.), as The Mill on the Tiber.

The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, The William Rockhill Nelson Collection, 2nd ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1941), 40, 168, as The Mill on the Tiber.

“Temporary Exhibitions: Landscapes of the European War Theatre,” Gallery News (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) 10, no. 5 (January 1944): 2, as Mill on the Tiber.

W. G. Constable, “The Early Work of Claude Lorrain,” Gazette des Beaux-Arts 26 (July-December 1944): 309.

Landscape: An Exhibition of Paintings, exh. cat. (Brooklyn, NY: Brooklyn Museum of Art, 1945), 29–30, as The Mill on the Tiber.

“Masterpiece of the Month,” Gallery News (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) 13, no. 7 (April 1947): unpaginated.

Fiftieth Exhibition of the Art of Europe during the XVIth–XVIIth Centuries, exh. cat. (Worcester: Worcester Art Museum, 1948), 22, as The Mill on the Tiber.

Winifred Shields, “The Twenty Best, a Special Exhibition at Nelson Gallery: Anniversary Will Be Observed by Showing of Paintings. Some Acquired Recently, Others Even Before the Institution Opened Two Decades Ago—Begins Next Friday,” Kansas City Star 74, no. 78 (December 4, 1953): 36, as Mill on the Tiber.

Gallery News (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) (1953).

Ross E. Taggart, ed., Handbook of the Collections in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 4th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1959), 106, (repro.), as The Mill on the Tiber.

“Treasures of Kansas City,” Connoisseur 145, no. 584 (April 1960): 123.

Probably André Chastel, Nicolas Poussin: Paris, 19–21 Septembre 1958 (Paris: Éditions du CNRS, 1960), 48.

Marcel Rœthlisberger, “Les dessins à figures de Claude Lorrain,” Critica d’arte 8, no. 47 (September–October 1961): 21.

Marcel Rœthlisberger, Claude Lorrain: The Paintings (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1961), no. 123; pp. 1:302–04, 391, 402, 405, 541; 2:unpaginated, (repro.), as Pastoral Landscape.

Anthony Blunt et al., Latin American Art, and the Baroque Period in Europe: Studies in Western Art; Acts of the Twentieth International Congress of the History of Art (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1963), 3:107, (repro.), as Pastoral Landscape.

Marcel Rœthlisberger, “Additions to Claude,” Burlington Magazine 110, no. 780 (March 1968): 119.

Marcel Rœthlisberger, Claude Lorrain: The Drawings (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1968), no. 123, p. 1:267; 2:unpaginated, as Pastoral Landscape.

Ralph T. Coe, “The Baroque and Rococo in France and Italy,” Apollo 96, no. 130 (December 1972): 534–35 [repr., in Denys Sutton, ed., William Rockhill Nelson Gallery, Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Kansas City (London: Apollo Magazine, 1972), 66–67], (repro.), as The Mill on the Tiber.

Ross E. Taggart and George L. McKenna, eds., Handbook of the Collections in The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Kansas City, Missouri, vol. 1, Art of the Occident, 5th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1973), 127, (repro.), as The Mill on the Tiber.

Marcel Rœthlisberger and Doretta Cecchi, L’Opera Completá di Claude Lorrain (Milan: Rizzoli, 1975), 111, 127, (repro.), as Paesaggio con Pastori.

Possibly John McPhee, John Glover, exh. cat. (Launceston, Tasmania, Australia: Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery, 1977), 10.

Marcel Rœthlisberger, Tout l’œuvre peint de Claude Lorrain, trans. Claude Lauriol (Paris: Flammarion, 1977), 111, 119, as Paysage avec bergers.

Michael Kitson, Claude Lorrain: Liber Veritatis (London: British Museum Publications, 1978), 129–30, as Pastoral Landscape.

John D. Morse, Old Master Paintings in North America: Over 3000 Masterpieces by 50 Great Artists (New York: Abbeville Press, 1979), 52, as The Mill on the Tiber.

Marcel Rœthlisberger, Claude Lorrain: The Paintings, 2nd ed. (New York: Hacker Art Books, 1979), no. 123; pp. 1:11n17, 196, 302–04, 310, 351, 359n1, 379, 391, 402, 405, 417, 541; 2:unpaginated, (repro.), as Pastoral Landscape.

Possibly John McPhee, The Art of John Glover (South Melbourne: Macmillan Company of Australia, 1980), 16.

Kathleen Spindler-Cruden, “Saving grace: Much of the art at the Nelson bears the touch of Forrest Bailey,” Kansas City Star 102, no. 307 (September 12, 1982): 31, as Mill on the Tiber.

Pierre Rosenberg, France in the Golden Age: Seventeenth-Century French Paintings in American Collections, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1982), 359, 378, (repro.), as Landscape with Shepherds and a Mill.

H[elen] Diane Russell, Claude Lorrain, 1600–1682, exh. cat. (New York: George Braziller, 1982), 166–67, 463, (repro.), as The Mill on the Tiber.

Antoine Terrasse, “Claude Gellée, dit le Lorrain: le chant de la lumière,” L’Œil, no. 334 (May 1983): 26–27, (repro.), as Le Moulin sur le Tibre.

Kathryn Cave, ed, The Diary of Joseph Farington (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983), 12:4276.

Tom L. Freudenheim, ed., American Museum Guides: Fine Arts; A Critical Handbook to the Finest Collections in the United States (New York: Collier, 1983), 112.

Christopher Wright, The French Painters of the Seventeenth Century (Boston: Little, Brown, 1985), 161, as Landscape with Shepherds.

Marcel Rœthlisberger, Tout l’œuvre peint de Claude Lorrain, new ed. (Paris: Flammarion, 1986), no. 191, pp. 111, 119–20, (repro.), as Paysage avec bergers.

Manfred Koch-Hillebrecht, Museen in den USA: Gemälde (Munich: Hirmer Verlag, 1992), 246, (repro.), as Die Mühle am Tiber.

Michael Churchman and Scott Erbes, High Ideals and Aspirations: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1933–1993 (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1993), 76, 80n15.

Roger Ward and Patricia J. Fidler, eds., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collection (New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1993), 166, (repro.), as Mill on the Tiber.

Michael Kelly, ed., Encyclopedia of Aesthetics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), 3:92, (repro.), as Mill on the Tiber.

Probably Jeroen Giltaij, Ruffo En Rembrandt: Over Een Siciliaanse Verzamelaar in de Zeventiende Eeuw Die Drie Schilderijen by Rembrandt Bestelde (Zutphen, The Netherlands: Walburg Pers, 1999), 35, 101, 144, 155–57, as Landschap met twee figuurtjes en veel dieren, Paesaggio con due figurine ed alcune capri, and Landschap met twee figuren en enkele geiten.

Michael Kitson, Studies on Claude and Poussin (London: Pindar Press, 2000), 69, (repro.), as Pastoral Landscape.

Probably Rosanna De Gennaro, “Aggiunta alle notizie sulla collezione di Antonio Ruffo: ‘nota di quadri vincolati in primogeniture’ scampati al terremoto del 5 febbraio 1783,” Napoli nobilissima 2, no. 5/6 (September–December 2001): 214, as “Due paesini, di palmi 2 1/2 e 3, di monsieur Claudio Lorenese, onze 40.”

David Hansen, John Glover and the Colonial Picturesque, exh. cat. (Hobart, Tasmania: Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, 2003), 18, 27, 40, 60, 72, 74, 135–137, 163, 176, 248, 282n73, (repro.), as The Mill on the Tiber.

Michael Rosenthal, “Exhibition Reviews; John Glover: Hobart and Adelaide,” Burlington Magazine 146, no. 1213 (April 2004): 289, as The Mill on the Tiber.

Perrin Stein, French Drawings from the British Museum: Clouet to Seurat, exh. cat. (London: British Museum Press, 2005), 74, 220n3, (repro.), as Pastoral Landscape.

“Decades-long Quest for Work by Thomas Cole Concludes with Major Acquisition,” Member Magazine (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (Spring 2005): 11, (repro.), as Mill on the Tiber.

Australian, International, and Aboriginal art (Double Bay, Australia: Bonhams and Goodman, December 5 and 11, 2006), as The Mill on the Tiber.

Andrew Morris, “The Man in a Blue Jacket. John Glover’s Van Diemen’s Land paintings: a clue, or just coincidence?,” Australiana 29, no. 3 (August 2007): 14.

Deborah Emont Scott, ed., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collection, 7th ed. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2008), 34, 76, (repro.), as Mill on the Tiber.

Probably Domenico Gioffrè, “Antonio Ruffo di Bagnara e la galleria d’arte di Messina nel secolo XVII,” Calabria sconosciuta 35, no. 134–35 (April–September 2012): 37.

Charles Sebag-Montefiore and Julia Armstrong-Totten, A Dynasty of Dealers: John Smith and Successors 1801–1924; A Study of the Art Market in Nineteenth-Century London (London: Roxburghe Club, 2013), 22, 26, 31n52, 70n36, 220, 224, 276, 297n3, as Landscape with a Shepherd and Shepherdess, Compn Shepherd and Shepherdess Even, and Mill on the Tiber.

Possibly Harry Bellet, “Don du ciel pour le Musée Nelson-Atkins: Henry Bloch cède une trentaine de tableaux impressionnistes à l’établissement de Kansas City,” Le Monde (March 13, 2017): http://www.lemonde.fr/arts/article/2017/03/13/don–du–ciel–pour–le–musee–Nelson-Atkins_5093543_1655012.html.

Glynnis Stevenson, “John Glover through the Claude Glass,” Australiana 44, no. 1 (February 2022): 10–15, (repro.), as Mill on the Tiber.

Important Australian and International Art (South Yarra, Australia: Menzies, March 27, 2024), http://www.menziesartbrands.com/items/20599.

Claude Gellée, Landscape with a Piping Shepherd, 1667

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Diana M. Jaskierny and John Twilley, “Claude Gellée, Landscape with a Piping Shepherd, 1667,” technical entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.208.2088.

MLA:

Jaskierny, Diana M., and John Twilley. “Claude Gellée, Landscape with a Piping Shepherd, 1667,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.208.2088.

In 1667, Claude Gellée, also known as Claude Lorrain or Le Lorrain (1604–82), completed the painting Landscape with a Piping Shepherd, a work that demonstrates his skill in capturing atmospheric perspectiveatmospheric perspective: An artistic technique used to create the illusion of depth in a composition in which distant elements are cooler and more diffuse, causing them to recede.. Questions exist regarding the original size of the painting because the tacking marginstacking margins: The outer edges of canvas that wrap around and are attached to the stretcher or strainer with tacks or staples. See also tacking edge. of the twill-weavetwill weave: A canvas weave in which one weft thread passes over one or more warp threads before passing under two or more warp threads, creating a pronounced diagonal pattern. canvas are no longer extant.1Evidence of the twill weave is visible in the film-based x-radiograph, no. X, NAMA conservation file, 31-57. The canvas was resized to enlarge the composition at an unknown date. An attempt was made to recreate the original dimensions during a conservation campaign at the Nelson-Atkins in 1971.

Fig. 18. Claude Lorrain, drawn record of Landscape with Piping Shepherd, 1667, pen and brown ink with gray and gray-brown washes on paper, 7 5/8 x 10 3/16 in. (19.3 x 25.8 cm), British Museum, London, 1957,1214.178

Fig. 18. Claude Lorrain, drawn record of Landscape with Piping Shepherd, 1667, pen and brown ink with gray and gray-brown washes on paper, 7 5/8 x 10 3/16 in. (19.3 x 25.8 cm), British Museum, London, 1957,1214.178

Fig. 19. Photomicrograph of figures and an animal on the bridge, Landscape with a Piping Shepherd (1667)

Fig. 19. Photomicrograph of figures and an animal on the bridge, Landscape with a Piping Shepherd (1667)

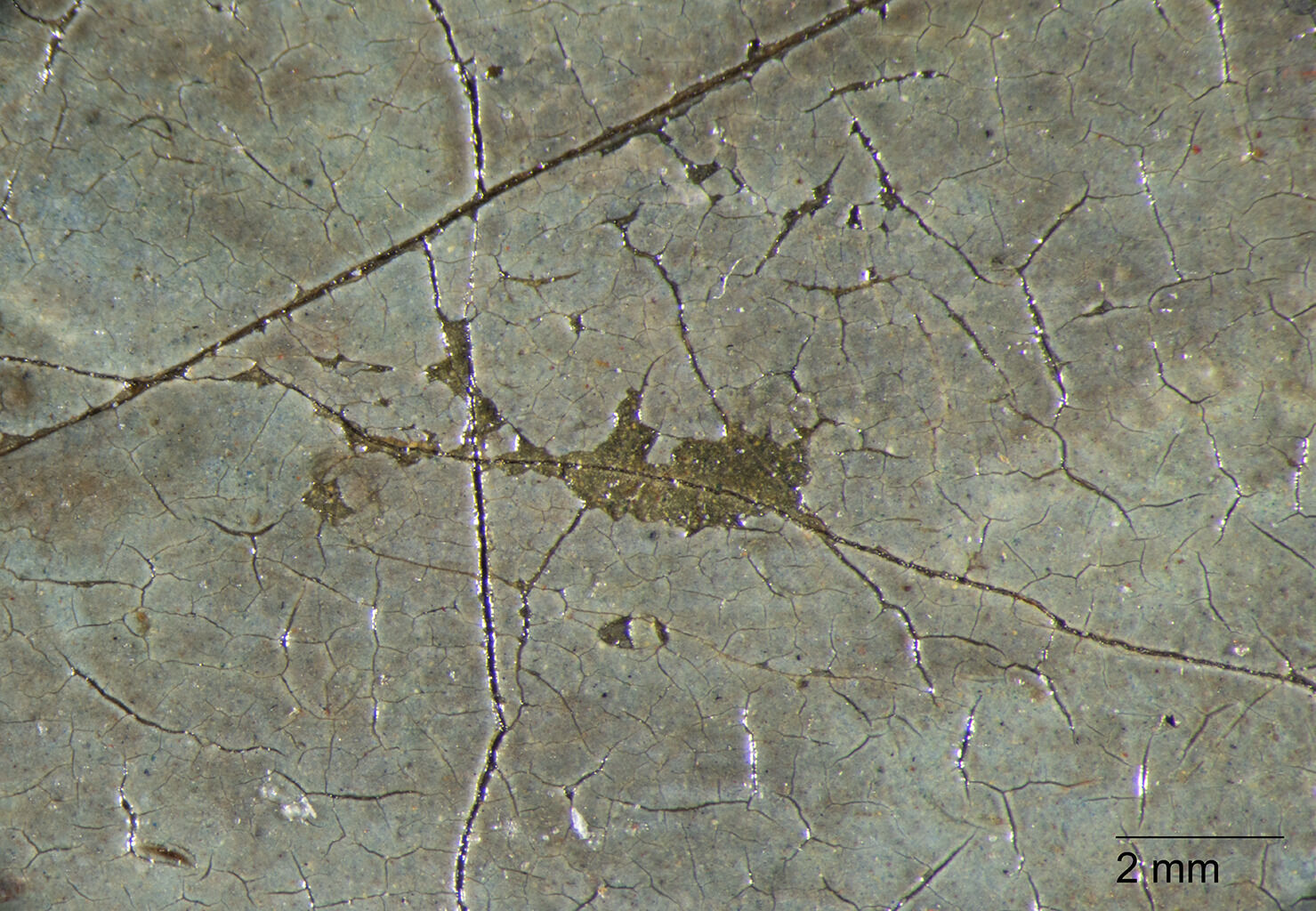

The pigments found in both Nelson-Atkins paintings are consistent with those identified in other Claude paintings as the “typical Claude mixture.”9Groen, “Scanning Electron-Microscopy as an Aid in the Study of Blanching,” 49. The majority of the pigments are finely ground and are utilized in complex admixtures. Throughout the foliage, green earth, smalt, and lead-tin yellow are present, with Naples yellow used within highlights. Ultramarine blue is the primary blue in the sky. Vermilion and bone black were also identified, and lead white is prevalent throughout the painting.