![]()

Attributed to Sébastien Bourdon, The Adoration of the Magi, ca. 1639

| Artist | Attributed to Sébastien Bourdon, French, 1616–71 |

| Title | The Adoration of the Magi |

| Object Date | ca. 1639 |

| Alternate and Variant Titles | L’Adoration des Rois; L’Adoration des Mages |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (Unframed) | 25 1/8 x 36 7/8 in. (63.8 x 93.7 cm) |

| Credit Line | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Robert L. Bloch in honor of Geraldine E. Fowle, F85-20 |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Attributed to Sébastien Bourdon, The Adoration of the Magi, ca. 1639,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.202.5407.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Attributed to Sébastien Bourdon, The Adoration of the Magi, ca. 1639,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.202.5407.

For Protestant painters in seventeenth-century France, the question of whether to accept commissions from the Catholic Church was a thorny one. While the Church’s patronage could provide a significant source of income, its persecution of the Huguenots during the French Wars of Religion (1562–98) was difficult for many Protestants to overlook. Differences in religious doctrine and practice likewise deterred Protestant artists from seeking Catholic benefactors. Often, Protestant painters skirted these issues by limiting their production to still lifes, portraits, genre scenes, landscapes, and mythological or allegorical subjects.1Jacques Thuillier, Sébastien Bourdon 1616–1671: Catalogue critique et chronologique de l’œuvre complet, exh. cat. (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 2000), 39. Such was not the case, however, with Sébastien Bourdon. Born in 1616 to a Protestant family in Montpellier, a well-known Protestant stronghold, Bourdon was married in the Protestant church and appointed painter to the Protestant court of Queen Christina of Sweden. Yet from a young age, he produced many biblical scenes and Catholic devotional images, exemplified by his “May painting” of 1643 for the Cathedral of Notre Dame, The Crucifixion of Saint Peter. Bourdon was twenty-seven years old when he completed this important commission, one in a series of paintings by different artists that were donated annually to the cathedral on May 1.2Between 1630 and 1707, the Confraternity of Saint Anne-Saint Marcel commissioned a monumental painting for the Cathedral of Notre Dame as an offering to the Virgin Mary. See Pierre-Marie Auzas, “Les Grands ‘Mays’ de Notre Dame de Paris,” Gazette des Beaux-Arts 36 (July–December 1949): 177–200; and Robert W. Berger, Public Access to Art in Paris: A Documentary History from the Middles Ages to 1800 (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1999), 53–59.

Fig. 1. Paolo Veronese, The Adoration of the Kings, 1573, oil on canvas, 140 x 126 in. (355.6 x 320 cm), National Gallery, London, NG268. Photo Credit: © National Gallery, London / Art Resource, NY

Fig. 1. Paolo Veronese, The Adoration of the Kings, 1573, oil on canvas, 140 x 126 in. (355.6 x 320 cm), National Gallery, London, NG268. Photo Credit: © National Gallery, London / Art Resource, NY

Fig. 2. Sébastien Bourdon, The Adoration of the Magi, ca. 1636–42, pen and brown ink, brown wash over black chalk on paper, 7 5/8 x 15 1/16 in. (19.4 x 38.2 cm), Musée du Louvre, Paris, inv. 24998-recto. Photo: Michèle Bellot. © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY

Fig. 2. Sébastien Bourdon, The Adoration of the Magi, ca. 1636–42, pen and brown ink, brown wash over black chalk on paper, 7 5/8 x 15 1/16 in. (19.4 x 38.2 cm), Musée du Louvre, Paris, inv. 24998-recto. Photo: Michèle Bellot. © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY

Fig. 3. Sébastien Bourdon, The Crucifixion of St. Peter, ca. 1644–45, oil on canvas, 32 1/16 x 24 9/16 in. (81.4 x 62.4 cm), Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, 1984.0027

Fig. 3. Sébastien Bourdon, The Crucifixion of St. Peter, ca. 1644–45, oil on canvas, 32 1/16 x 24 9/16 in. (81.4 x 62.4 cm), Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, 1984.0027

Fig. 4. Sébastien Bourdon, Jacob Burying Laban’s Images, ca. 1636–42, oil on canvas, 37 3/8 x 50 13/16 in. (95 x 129 cm), The State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, ГЭ-3682 7481

Fig. 4. Sébastien Bourdon, Jacob Burying Laban’s Images, ca. 1636–42, oil on canvas, 37 3/8 x 50 13/16 in. (95 x 129 cm), The State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, ГЭ-3682 7481

Although the Nelson-Atkins picture contains a selection of Bourdon’s signature motifs, a small number of scholars have cast doubt on the painting’s authenticity. When American dealer Germain Seligman (1893–1978) purchased The Adoration of the Magi from André de Haspe, a minor Parisian dealer, in 1961, he solicited the opinion of Jacques Thuillier, who judged it to be an early autograph work dating to 1637–40.8Fowle, “The Biblical Paintings of Sébastien Bourdon,” 2:89, 2:92n5. Seligman was born in Paris but became an American citizen in 1943. Thuillier probably based his assessment on a photograph of the painting. However, when the painting was sold at auction nearly twenty years later, the sale catalogue listed it as “attributed to Sébastien Bourdon.”9Important Paintings by Old Masters, Christie’s, New York, June 5, 1980, lot 29. The next owner, Robert L. Bloch, took an active interest in the painting’s attribution and contacted several scholars and connoisseurs, seeking their opinion. Charles Sterling, Denis Mahon, Jean-Patrice Marandel, Martin J. Zimet, Richard L. Feigen, and Anthony Blunt all assured Bloch that it was genuine.10Sterling wrote: “Judging by the photograph, there is little doubt in my mind that you bought an original by Sébastien Bourdon.” Mahon concurred: “I do indeed agree, from the photos, that your painting must be the work of Bourdon.” Marandel responded: “It is a fine work by Bourdon and I don’t see any reason to doubt its authenticity.” Zimet stated definitively: “This painting, measuring 26 x 37 1/2 inches (66 x 95.2 cm) is an early work by the artist, dating circa 1638–9. The condition is excellent.” Feigen was less definitive but still supported the attribution to Bourdon: “I congratulate you on your acquisition of what appears to be a fine early Bourdon.” Blunt echoed Sterling and Mahon’s remarks: “From the photograph your painting looks like a very fine Bourdon.” See Charles Sterling to Robert L. Bloch, September 28, 1980; Denis Mahon to Robert L. Bloch, September 29, 1980; Jean-Patrice Marandel to Robert L. Bloch, October 27, 1980; Martin J. Zimet to Robert L. Bloch, February 27, 1981; Richard L. Feigen to Robert L. Bloch, April 17, 1981; and Anthony Blunt to Robert L. Bloch, undated, NAMA curatorial files. Around the same time, Geraldine Fowle delivered a presentation on Bourdon at the Eighth Annual Midwest Art History Society conference, in which she acknowledged The Adoration of the Magi’s somewhat uneven quality but interpreted it as “the sign—not of a copyist—but of a youthful mind and talent still searching to establish itself.”11See Geraldine E. Fowle, “Sébastien Bourdon’s ‘Adoration of the Magi’: A Problem in Juvenilia,” paper presented at the Eighth Annual Meeting of the Midwest Art History Society, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN, March 27, 1981, transcript in NAMA curatorial files. As Fowle observes, the arch is “lamentably askew,” and the recession of space in the left background is not altogether convincing.

More recently, Lorenzo Pericolo, a specialist in early modern religious art, examined The Adoration of the Magi during a visit to the Nelson-Atkins in 2015. He praised the quality and finish of the kneeling magus and his young page, particularly in comparison to the Enschede version, and suggested that Bourdon had left certain passages of both versions deliberately sketchy in order to focus attention on the Virgin and Christ child.15Pericolo did not have an opportunity to see the Enschede version in person prior to visiting the Nelson-Atkins, but he did have access to a high-resolution color photograph of the Rijksmuseum Twenthe painting, which was unavailable to Thuillier when he was preparing the catalogue raisonné. In Pericolo’s estimation, the Enschede version was executed with “a looser hand.” See notes from discussion with Lorenzo Pericolo, Associate Professor, History of Art, University of Warwick, May 27, 2015, NAMA curatorial files. Pericolo dismissed the idea that the Nelson-Atkins Adoration was done by an assistant or copyist, expressing confidence that it was, rather, “a variant by Bourdon.”16See Pericolo discussion, NAMA curatorial files. Little is known about Bourdon’s studio practice, but scholars generally agree that he did not employ assistants until at least 1643, the year he completed his May painting.17Thuillier, Sébastien Bourdon, 64–70. His assistants may have included Nicolas Loyr (b. 1624), Antoine Paillet (1626–1701), Théodore van der Schur (b. 1628), Pierre Monier (1641–1703), Jacques Prou (b. ca. 1640), and Jacques Friquet (1638–1716). Loyr seems to have apprenticed with Vouet before joining Bourdon’s studio, while Monier and Prou were probably students of Bourdon at the Académie Royale. Records indicate that Friquet assisted Bourdon with the decoration of the Hôtel Bretonvilliers, a very important commission. It seems doubtful that Bourdon would have hired any assistants before this watershed commission, as he himself was still an up-and-coming artist in his early twenties.

The possibility of autograph copies has never been raised in the literature on Bourdon, although several of his early works (pre-1643) are known to have replicas, and some of these could conceivably be by his hand.18See, for instance, King Solomon Making Sacrifices to the Idols (nos. 3-I and 3-II), Lamentation over the Dead Christ (nos. 5-I, 5-II, and 5-III), and Presentation in the Temple (nos. 73-I and 73-II). All numbers refer to the catalogue raisonné. In the case of The Adoration of the Magi, the patchy historical record further complicates this question. Nothing is known about the circumstances under which either version was painted. It was not until the second half of the eighteenth century that the Nelson-Atkins painting (or its replica) surfaced in a series of public auctions, beginning with the sale of Pierre-Charles, Marquis du Plessis-Villette (1700–65), in 1765. At this sale, an Adoration des Rois canvas measuring 24 x 34 1/2 pouces (a French pre-revolutionary measurement approximately equivalent to an inch) was offered as the work of Bourdon. A year later, an Adoration des Rois painting of nearly identical dimensions was featured in the sale of an anonymous collector at the Hôtel des Américains. After a brief interval in private hands, it reemerged at the sales of Le Doux in 1775; Joseph Hyacinthe François de Paule de Rigaud, Comte de Vaudreuil (1740–1817), in 1787; Laurent Grimod de la Reynière (1734–93) in 1793; and finally an anonymous collector in 1797.

A detailed description of the painting from the Comte de Vaudreuil sale19Catalogue d’une Très-Belle Collection de Tableaux, d’Italie de Flandres, de Hollande, et de France; . . . Provenans du Cabinet de M. (Paris: Le Brun, 1787), 31. leaves little doubt that the Comte owned either the Nelson-Atkins picture or the Rijksmuseum Twenthe painting. Determining which one is difficult, however, because the compositional differences between them are so slight. The architecture behind the Virgin, for instance, is more clearly delineated in the Kansas City picture, and a small patch of blue sky, absent in the Enschede version, is visible above her head. The most noticeable discrepancy today lies in the treatment of the sky, which is brighter and less ominous in the Nelson-Atkins painting—but this color scheme is due largely to retouching from a past restoration.20Schafer technical notes, NAMA conservation files. Prior to restoration, the sky in the Nelson-Atkins picture was a more muted gray-blue.

During the nineteenth century, both pictures once again disappeared from the historical record. The Rijksmuseum Twenthe Adoration of the Magi resurfaced at the J. F. Austen sale in London in 1921, while the Nelson-Atkins version passed into the collection of a certain Madame Laurens, about whom nothing is known.21Until recently, the Adoration of the Magi at the J. F. Austen sale was mistaken for the Nelson-Atkins picture. However, correspondence with Christie’s and the Rijksmuseum Twenthe confirms that lot 25 was purchased by the dealer W. E. Duits and sold shortly thereafter to Jan Bernard van Heek, who donated it to the Rijksmuseum Twenthe in 1922. See Anna Covatta to Brigid M. Boyle, November 15, 2013; and Quirine van der Meer to Brigid M. Boyle, June 4, 2014, NAMA curatorial files. Archival documentation places the Nelson-Atkins painting in the stock of André de Haspe by 1961. However, the lengthy gap between these transactions and the abovementioned sales is such that neither painting can be tied to the eighteenth-century auctions with any degree of certainty. It could be that two separate paintings, both considered autograph works by Bourdon, were on the market in the same decades, but without further information we can only speculate.

When the Nelson-Atkins picture was examined, no changes were detected that would unambiguously denote Bourdon’s hand.22Schafer technical notes, NAMA conservation files. The Rijksmuseum Twenthe Adoration of the Magi has not undergone an equivalent technical examination, nor have the two paintings ever been studied side by side. Both pictures would certainly benefit from such a comparison, which—even if it could not settle questions of authenticity—might establish which version was made first.

While a majority of scholars recognize the Nelson-Atkins Adoration of the Magi as an authentic work by Bourdon, the few dissenting opinions, the incomplete provenance narrative, and the lack of information about the role of autograph copies in Bourdon’s artistic practice all support the designation of “attributed to Bourdon.” Even so, the Nelson-Atkins painting offers valuable insight into an early biblical composition by Bourdon, a Protestant painter who secured important religious commissions in a Catholic-majority state. Maligned by Félibien and other contemporary critics as a touché-à-tout (jack of all trades, master of none), Bourdon nevertheless developed a versatile iconography befitting an artist who sought to excel in multiple genres.

Notes

-

Jacques Thuillier, Sébastien Bourdon 1616–1671: Catalogue critique et chronologique de l’œuvre complet, exh. cat. (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 2000), 39.

-

Between 1630 and 1707, the Confraternity of Saint Anne-Saint Marcel commissioned a monumental painting for the Cathedral of Notre Dame as an offering to the Virgin Mary. See Pierre-Marie Auzas, “Les Grands ‘Mays’ de Notre Dame de Paris,” Gazette des Beaux-Arts 36 (July–December 1949): 177–200; and Robert W. Berger, Public Access to Art in Paris: A Documentary History from the Middles Ages to 1800 (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1999), 53–59.

-

Bourdon so rarely signed or dated his work that Thuillier found suspect the presence of a date in the upper left quadrant of Bourdon’s The Card Players (Staatliche Museen, Kassel, Germany); see Thuillier, Sébastien Bourdon, 148.

-

G[eraldine] E[lizabeth] Fowle, “The Biblical Paintings of Sébastien Bourdon” (PhD diss., University of Michigan, 1970), 1:82–83. Fowle points out that Bourdon could have known the composition either from the original, which he may have seen in situ in 1636, or from Simon Vouet’s (1590–1649) painting for the Hôtel Séguier, which was closely inspired by the same work.

-

“Tantost il cherchoit à suivre le coloris de Titien; tantost la disposition et les ordonnances du Poussin, comme il avoit fait celle de Benedette, sans faire choix d’un goust particulier.” André Félibien, Entretiens sur les Vies et sur les Ouvrages des plus Excellens Peintres Anciens et Modernes, 2nd ed. (Paris: Sébastien Mabre-Cramoisy, 1688), 2:510–11, cited in Thuillier, Sébastien Bourdon, 134. All translations are by Brigid M. Boyle.

-

Thuillier, Sébastien Bourdon, 200.

-

Originally thought to be a modello for Bourdon’s May painting, the Spencer’s picture is now considered an independent, finished work produced at a slightly later date; see https://spencerartapps.ku.edu/collection-search#/Object/15193.

-

Fowle, “The Biblical Paintings of Sébastien Bourdon,” 2:89, 2:92n5. Seligman was born in Paris but became an American citizen in 1943. Thuillier probably based his assessment on a photograph of the painting.

-

Important Paintings by Old Masters, Christie’s, New York, June 5, 1980, lot 29.

-

Sterling wrote: “Judging by the photograph, there is little doubt in my mind that you bought an original by Sébastien Bourdon.” Mahon concurred: “I do indeed agree, from the photos, that your painting must be the work of Bourdon.” Marandel responded: “It is a fine work by Bourdon and I don’t see any reason to doubt its authenticity.” Zimet stated definitively: “This painting, measuring 26 x 37 1/2 inches (66 x 95.2 cm) is an early work by the artist, dating circa 1638–9. The condition is excellent.” Feigen was less definitive but still supported the attribution to Bourdon: “I congratulate you on your acquisition of what appears to be a fine early Bourdon.” Blunt echoed Sterling and Mahon’s remarks: “From the photograph your painting looks like a very fine Bourdon.” See Charles Sterling to Robert L. Bloch, September 28, 1980; Denis Mahon to Robert L. Bloch, September 29, 1980; Jean-Patrice Marandel to Robert L. Bloch, October 27, 1980; Martin J. Zimet to Robert L. Bloch, February 27, 1981; Richard L. Feigen to Robert L. Bloch, April 17, 1981; and Anthony Blunt to Robert L. Bloch, undated, NAMA curatorial files.

-

See Geraldine E. Fowle, “Sébastien Bourdon’s ‘Adoration of the Magi’: A Problem in Juvenilia,” paper presented at the Eighth Annual Meeting of the Midwest Art History Society, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN, March 27, 1981, transcript in NAMA curatorial files. As Fowle observes, the arch is “lamentably askew,” and the recession of space in the left background is not altogether convincing.

-

Thuillier, Sébastien Bourdon, 207. “Nous n’avons pu examiner le tableau, actuellement conservé aux États-Unis, mais la photographie donne de grands doutes quant à sa qualité d’original.”

-

Marandel to Bloch, October 27, 1980, NAMA curatorial files.

-

For the correct dimensions, see Quirine Van der Meer to Brigid M. Boyle, June 4, 2014, NAMA curatorial files. In Thuillier’s catalogue raisonné, the dimensions of the Rijksmuseum Twenthe painting are erroneously given as 90 x 110 cm (35 7/16 x 43 5/16 in.).

-

Pericolo did not have an opportunity to see the Enschede version in person prior to visiting the Nelson-Atkins, but he did have access to a high-resolution color photograph of the Rijksmuseum Twenthe painting, which was unavailable to Thuillier when he was preparing the catalogue raisonné. In Pericolo’s estimation, the Enschede version was executed with “a looser hand.” See notes from discussion with Lorenzo Pericolo, Associate Professor, History of Art, University of Warwick, May 27, 2015, NAMA curatorial files.

-

See Pericolo discussion, NAMA curatorial files.

-

Thuillier, Sébastien Bourdon, 64–70. His assistants may have included Nicolas Loyr (b. 1624), Antoine Paillet (1626–1701), Théodore van der Schur (b. 1628), Pierre Monier (1641–1703), Jacques Prou (b. ca. 1640), and Jacques Friquet (1638–1716). Loyr seems to have apprenticed with Vouet before joining Bourdon’s studio, while Monier and Prou were probably students of Bourdon at the Académie Royale. Records indicate that Friquet assisted Bourdon with the decoration of the Hôtel Bretonvilliers, a very important commission.

-

See, for instance, King Solomon Making Sacrifices to the Idols (nos. 3-I and 3-II), Lamentation over the Dead Christ (nos. 5-I, 5-II, and 5-III), and Presentation in the Temple (nos. 73-I and 73-II). All numbers refer to the catalogue raisonné.

-

Catalogue d’une Très-Belle Collection de Tableaux, d’Italie de Flandres, de Hollande, et de France; . . . Provenans du Cabinet de M. (Paris: Le Brun, 1787), 31.

-

Schafer technical notes, NAMA conservation files. Prior to restoration, the sky in the Nelson-Atkins picture was a more muted gray-blue.

-

Until recently, the Adoration of the Magi at the J. F. Austen sale was mistaken for the Nelson-Atkins picture. However, correspondence with Christie’s and the Rijksmuseum Twenthe confirms that lot 25 was purchased by the dealer W. E. Duits and sold shortly thereafter to Jan Bernard van Heek, who donated it to the Rijksmuseum Twenthe in 1922. See Anna Covatta to Brigid M. Boyle, November 15, 2013; and Quirine van der Meer to Brigid M. Boyle, June 4, 2014, NAMA curatorial files.

-

Schafer technical notes, NAMA conservation files.

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Diana M. Jaskierny, “Attributed to Sébastien Bourdon, The Adoration of the Magi, ca. 1639,” technical entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.202.5407.

MLA:

Jaskierny, Diana M. “Attributed to Sébastien Bourdon, The Adoration of the Magi, ca. 1639,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.202.5407.

The Adoration of the Magi was executed on a medium weight, plain-weaveplain weave: A basic textile weave in which one weft thread alternates over and under the warp threads. Often this structure consists of one thread in each direction, but threads can be doubled (basket weave) or tripled to create more complex plain weave. Plain weave is sometimes called tabby weave. canvas. The majority of its tacking marginstacking margins: The outer edges of canvas that wrap around and are attached to the stretcher or strainer with tacks or staples. See also tacking edge. are no longer extant and were likely removed in preparation for an early lininglining: A procedure used to reinforce a weakened canvas that involves adhering a second fabric support using adhesive, most often a glue-paste mixture, wax, or synthetic adhesive., creating uncertainty as to the original dimensions of the painting. However, along the top and bottom edges, remnants of the original turnover edgeturnover edge: The point at which the canvas begins to wrap around the stretcher, at the junction between the picture plane and tacking margin. See also foldover edge. and tacking margins are visible in a few locations, revealing that the vertical dimensions are unchanged. No similar remnants remain on the right and left tacking edges, and approximately three millimeters of the picture planepicture plane: The two-dimensional surface where the artist applies paint. was folded onto the right tacking margin. However, when the size of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art painting (63.8 x 93.7 centimeters) is compared to another, near-identical version, also attributed to Bourdon, located at the Rijksmuseum Twenthe (65.2 x 95 centimeters), the width of the Nelson-Atkins painting does not appear to have been significantly altered.1While the Nelson-Atkins painting might have been cropped, it is unlikely that either one was significantly altered, as both compositions contain the same elements. The pronounced cuspingcusping: A scalloped pattern along the canvas edges that relates to how the canvas was stretched. Primary cusping reveals where tacks secured the canvas to the support while the ground layer was applied. Secondary cusping can form when a pre-primed canvas is re-stretched by the artist prior to painting. along the top edge and a slightly coarser canvas weave may relate to the selvedgeselvedge: The original woven edge of fabric formed by the weft threads looping over the warp during the loom weaving process. The selvedge runs the length of the fabric bolt, parallel to the warp threads, and forms a finished edge. edge from a larger canvas production, before it was cut for this painting. Slight cusping on the bottom, left, and right is equidistant and is likely secondary cusping.

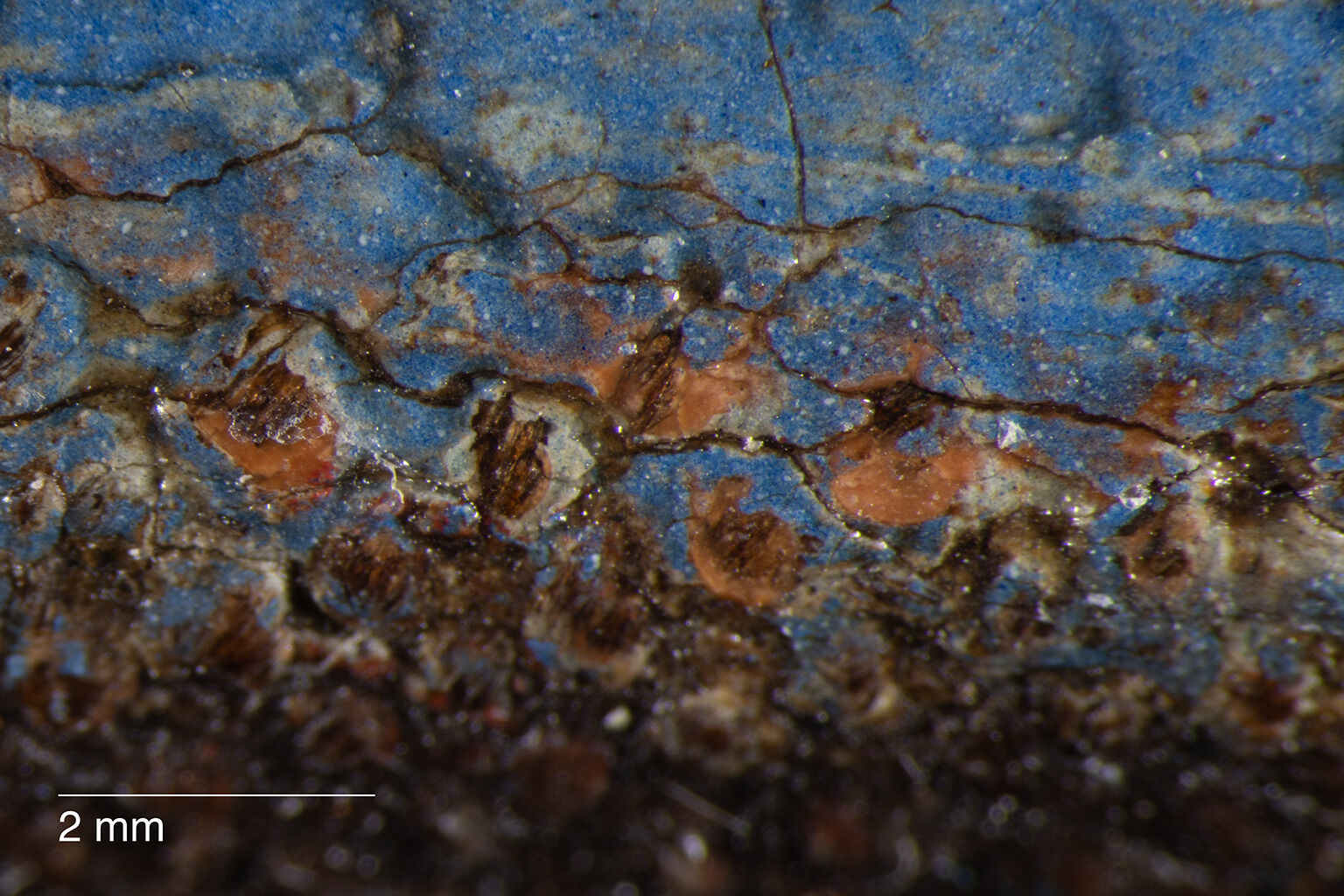

The canvas was prepared with a double groundground layer: An opaque preparatory layer applied to the support, either commercially or by the artist, to prevent absorption of the paint into the canvas or panel. See also priming layer., consisting of a lower layer colored red-brown and an upper layer that is light gray.2The use of double grounds was common among many seventeenth-century French artists, including Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665), an artist admired by Bourdon who later lectured on his technique. G[eraldine] E[lizabeth] Fowle, The Biblical Paintings of Sébastien Bourdon (PhD diss., University of Michigan, 1970), 1:7. For more information on Poussin’s technique, see Mary Schafer and John Twilley, “Nicolas Poussin, The Triumph of Bacchus, 1635-1636,” technical entry in this catalogue, https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.210.2088. The warm lower ground layer is visible in only a few small losses along the top turnover edge (Fig. 6) but is otherwise covered by the upper ground layer. The gray layer, treated as an imprimaturaimprimatura: A thin layer of paint applied over the ground layer to establish an overall tonality., covers the entire picture plane and is utilized within the composition as a midtone. This is especially noticeable within some faces, where the cool gray tone provides contrast to the warmer peach tones. For example, within Mary’s face, strokes of light peach form the highlights along the nose, forehead, and brow, while the gray tone provides a transition between the highlights and shadows (Fig. 7). Here, juxtaposing the cool ground with the warm peach skin tones provides the illusion of form.

Fig. 6. Photomicrograph of the lower red-brown and upper gray ground layers on the top turnover edge, Adoration of the Magi (ca. 1639)

Fig. 6. Photomicrograph of the lower red-brown and upper gray ground layers on the top turnover edge, Adoration of the Magi (ca. 1639)

Fig. 7. Detail of Mary’s face with the exposed gray upper ground layer, Adoration of the Magi (ca. 1639)

Fig. 7. Detail of Mary’s face with the exposed gray upper ground layer, Adoration of the Magi (ca. 1639)

Fig. 8. Detail of the back central figure with brown washes throughout the face and torso, Adoration of the Magi (ca. 1639)

Fig. 8. Detail of the back central figure with brown washes throughout the face and torso, Adoration of the Magi (ca. 1639)

Fig. 9. Detail of the kneeling young page with washes compared to opaque rendering, Adoration of the Magi (ca. 1639)

Fig. 9. Detail of the kneeling young page with washes compared to opaque rendering, Adoration of the Magi (ca. 1639)

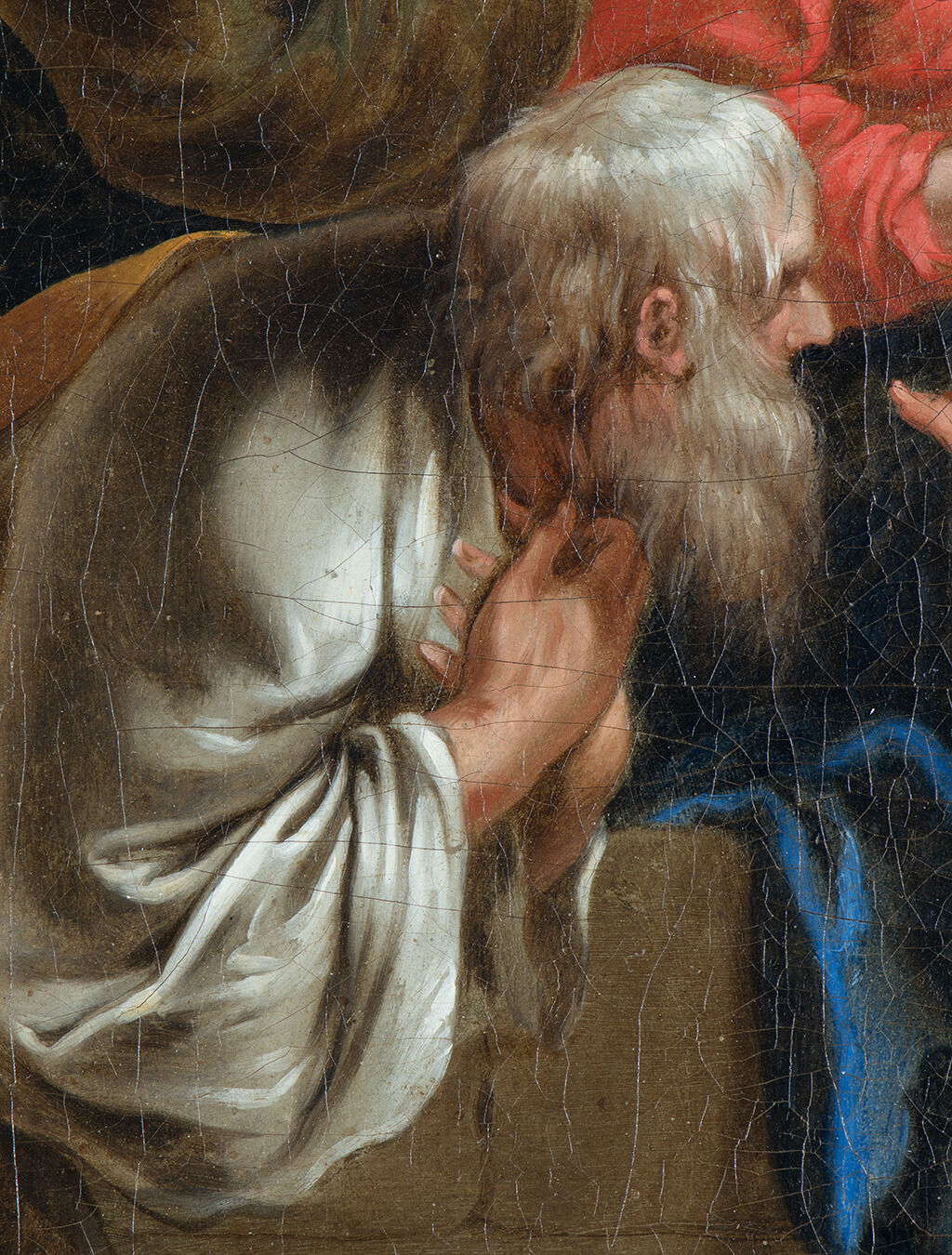

Fig. 10. Detail of the kneeling magus, illustrating the fine brushwork in the hair and beard, Adoration of the Magi (ca. 1639)

Fig. 10. Detail of the kneeling magus, illustrating the fine brushwork in the hair and beard, Adoration of the Magi (ca. 1639)

Fig. 11. Detail of the painterly brushwork in the magus’s turban, Adoration of the Magi (ca. 1639)

Fig. 11. Detail of the painterly brushwork in the magus’s turban, Adoration of the Magi (ca. 1639)

Notes

-

While the Nelson-Atkins painting might have been cropped, it is unlikely that either one was significantly altered, as both compositions contain the same elements.

-

The use of double grounds was common among many seventeenth-century French artists, including Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665), an artist admired by Bourdon who later lectured on his technique. G[eraldine] E[lizabeth] Fowle, The Biblical Paintings of Sébastien Bourdon (PhD diss., University of Michigan, 1970), 1:7. For more information on Poussin’s technique, see Mary Schafer and John Twilley, “Nicolas Poussin, The Triumph of Bacchus, 1635–1636,” technical entry in this catalogue.

-

Through infrared reflectography, it was determined that the architecture does not pass beneath the figures. This indicates that the placement of the figures was established before the architecture was completed.

-

The same general pattern of finish is found in the Rijksmuseum Twenthe version.

-

Forrest R. Bailey, March 10, 1981, treatment report, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, F85-20. The painting was treated in Forrest Bailey’s private practice prior to entering the Nelson-Atkins collection in 1985.

-

Forrest R. Bailey, December 3, 1980, examination report, NAMA conservation file, F85-20.

-

When examining the painting with ultraviolet radiation, no differentiation between these highlights and the surrounding paint could be detected. While this indicates that the highlights do not relate to a recent restoration, it does not determine whether they are original or an early restoration.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Attributed to Sébastien Bourdon, The Adoration of the Magi, ca. 1639,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.202.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Attributed to Sébastien Bourdon, The Adoration of the Magi, ca. 1639,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.202.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Attributed to Sébastien Bourdon, The Adoration of the Magi, ca. 1639,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.202.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Attributed to Sébastien Bourdon, The Adoration of the Magi, ca. 1639,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.202.4033.

Possibly Pierre-Charles, marquis du Plessis-Villette (1700–65), Paris, by April 8, 1765;

Possibly purchased at his sale, Tableaux, de Différens Bons Maîtres des Trois Écoles, De Figures de Bronze, de Bustes de Marbre, d’Estampes montées sous verre, et d’Estampes en Feuilles, après le Décès de M. le Marquis de Villette, Pere [sic], l’Hôtel d’Elbeuf, rue de Vaugirard, Paris, April 8, 1765, lot 30, as Sébastien Bourdon, Une Adoration des Rois, by Jean-Baptiste-Pierre Le Brun (1748–1813), Paris, 1765 [1];

Possibly purchased at the sale of M. ***, Tableaux du Cabinet de Monsieur ***: Sçavoir, Tableaux, Desseins, Estampes, Bronzes, Bustes de marbre, Gaînes de marbre et de bois, Porcelaines différentes, montées et non montées, Meubles, Pendules, Feux, Bras de cheminées, Secrétaires, etc., Hôtel des Américains, rue Saint Honoré, Paris, December 15, 1766, lot 16, as Sébastien Bourdon, l’Adoration des Rois, by Pierre-François Basan (1723–97), Paris, 1766 [2];

Possibly le Doux Collection, by April 24, 1775 [3];

Possibly purchased at his sale, Une Précieuse Collection de Tableaux, Bronzes, Marbres, Porcelaines, Lacques, Pierres gravées et autres Pierres précieuses, Meubles et objets de curiosité, Provenans du Cabinet de M. le Doux, Maison de Saint Louis, rue Saint Antoine, Paris, April 24, 1775, lot 46, as Sébastien Bourdon, L’adoration des Rois, by Feullet, Paris, 1775 [4];

Possibly Joseph-Hyacinthe-François de Paule de Rigaud, Comte de Vaudreuil (1740–1817), Paris, by November 26, 1787;

Possibly purchased at his sale, Une Très-Belle Collection de Tableaux, d’Italie de Flandres, de Hollande, et de France . . . Provenans du Cabinet de M. ***., grande Salle, 96 rue de Cléry, Paris, November 26, 1787, lot 42, as Sébastien Bourdon, L’Adoration des Rois, by Jean-Baptiste-Pierre Le Brun, for Laurent Grimod de La Reynière (1734–93), 1787–April 3, 1793 [5];

Possibly purchased at his sale, Tableaux Formant le Cabinet de M. de Lareynière; Composé en partie des Tableaux des plus grands Maîtres de l’Ecole Française: on y distingue, par-dessus tout, les chef-d’œuvres de l’immortel Lemoyne, les seuls, pour ainsi dire, qui soient connus, Salle de Vente, 96 rue de Cléry, Paris, April 3, 1793, lot 8, as Sébastien Bourdon, L’adoration des Rois, by Defer, 1793 [6];

Possibly purchased at the sale of M. ***, Une Belle Collection de Tableaux des Trois Écoles, Et autres Objets curieux; du Cabinet de M. ***, ancien hôtel Notre-Dame, rue du Bouloy, Paris, June 16, 1797, lot 6, as Sébastien Bourdon, l’Adoration des Mages, by Trudaine, 1797 [7];

Laurens Collection, Montpellier [8];

With André de Haspe, Paris, by May 15–June 2, 1961 [9];

Purchased from de Haspe by Germain Seligman (1893–1978), New York, June 2, 1961–March 27, 1978 [10];

Possibly inherited by his wife, Ethlyne Jackson Seligman (1906–93), New York, 1978 [11];

Purchased at Important Paintings by Old Masters, Christie’s, New York, June 5, 1980, lot 29, as attributed to Sébastien Bourdon, The Adoration of the Magi, by Robert L. Bloch, Shawnee Mission, KS, 1980–85;

Given by Mr. and Mrs. Robert L. Bloch to The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1985.

Notes

[1] Annotated sales catalogue at the Bibliothèque Publique et Universitaire, Geneva, records “LeBrun” as the buyer. It is unclear whether the painting in this sale was the Nelson-Atkins picture or the version attributed to Bourdon in the collection of the Rijksmuseum Twenthe, Enschede.

[2] Annotated sales catalogue at the Bibliothèque Publique et Universitaire, Geneva, records “Basan” as the buyer. It is unclear whether the painting in the sale was the Nelson-Atkins or the version attributed to Bourdon in the collection of the Rijksmuseum Twenthe, Enschede.

[3] M. le Doux may have been Paul-Guillaume Ledoux (d. 1781), a painter at the Académie de Saint-Luc who was active as a dealer from the early-1750s through the mid-1770s.

[4] Annotated sales catalogue at the Bibliothèque municipale de Versailles records “Feullet” (believed to be a misspelling of “Feuillet”) as the buyer. Between 1768 and 1784, a buyer named “Feuillet” bid on 249 works of art in 49 different sales. This may have been Jean-Baptiste Feuillet (d. 1806), a director of the Académie de Saint-Luc and well-known dealer. It is unclear whether the painting in this sale was the Nelson-Atkins or the version attributed to Bourdon in the collection of the Rijksmuseum Twenthe, Enschede.

[5] Annotated sales catalogues at the Bibliothèque d’Art et d’Archéologie, Paris; the Bibliothèque Municipale, Orléans; and the British Museum, London, record “LeBrun” as the buyer. Lebrun acted as an agent for Grimod de La Reynière. It is unclear whether the painting in the sale was the Nelson-Atkins or the version attributed to Bourdon in the collection of the Rijksmuseum Twenthe, Enschede. The version featured in this sale was subsequently sold in the Grimod de La Reynière sale; see description for lot 8.

[6] Annotated sales catalogue at the Bibliothèque d’Art et d’Archéologie, Paris, records “Defer” as the buyer of lots 8 and 14. Lot 14 was later resold at Radix de Sainte-Foy’s sale on January 16, 1811 (lot 33), and an annotated sales catalogue at the Bibliothèque d’Art et d’Archéologie, Paris, records “de Fer de Lanoray” in the provenance of lot 33. “De Fer de Lanoray” may thus be the full name of the buyer that purchased lot 8 at the Grimod de La Reynière sale.

[7] Annotated sales catalogue at the Bibliothèque Publique et Universitaire, Geneva, records the buyer as “Trudaine.” It is unclear whether the painting in the sale was the Nelson-Atkins or the version attributed to Bourdon in the collection of the Rijksmuseum Twenthe, Enschede.

[8] Per Jacques Seligmann & Co. records, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C., Series 12.2 “Private Art Collection,” Box 426, Folder 13. This collector is usually described as “Madame Laurens” in the literature.

[9] See letter from André de Haspe to Germain Seligman, May 15, 1961, Jacques Seligmann & Co. records, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C., Series 1.3, General Correspondence (1913–1978), Box 29, Folder 21.

[10] Per Jacques Seligmann & Co. records, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C., Series 7.11.2 “Sales Ledgers, 1931–1973,” Box 331, Folder 5, no. 8637. Although the painting was assigned a stock number (no. 8637), Seligman purchased it for his private collection, not his gallery.

[11] Although most of Germain Seligman’s private collection was purchased by Artemis S. A. and E. V. Thaw and Co. and published in John Richardson, The Collection of Germain Seligman: Paintings, Drawings, and Works of Art (New York: E. V. Thaw, 1979), this painting may have been one of the few personal bequests Seligman made to his wife.

Interestingly, Jackson Seligman was the Nelson-Atkins secretary to the museum’s first director, Paul Gardner, from 1933 until 1946. During World War II when Gardner was drafted (1942–45), Jackson Seligman served as Interim Director: the museum’s first and only woman to serve as director. For more on Jackson Seligman, see https://missouriartists.org/person/morem234/.

Preparatory Works

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Attributed to Sébastien Bourdon, The Adoration of the Magi, ca. 1639,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.202.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Attributed to Sébastien Bourdon, The Adoration of the Magi, ca. 1639,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.202.4033.

Sébastien Bourdon, L’Adoration des Mages, ca. 1639, pen, brown ink, brown wash, with traces of black chalk, 7 5/8 x 15 1/16 in (19.4 x 38.2 cm), Musée du Louvre, Paris, inv. 24998.

Known Copies

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Attributed to Sébastien Bourdon, The Adoration of the Magi, ca. 1639,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.202.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Attributed to Sébastien Bourdon, The Adoration of the Magi, ca. 1639,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.202.4033.

Attributed to Sébastien Bourdon, L’Adoration des mages, 17th century, oil on canvas, 25 11/16 x 37 3/8 in (65.2 x 95 cm), Rijksmuseum Twenthe, Enschede, The Netherlands, 0547.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Attributed to Sébastien Bourdon, The Adoration of the Magi, ca. 1639,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.202.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Attributed to Sébastien Bourdon, The Adoration of the Magi, ca. 1639,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.202.4033.

Vouet to Rigaud: French Masters of the Seventeenth Century, Finch College Museum of Art, New York, April 20–June 18, 1967, no. 38.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Attributed to Sébastien Bourdon, The Adoration of the Magi, ca. 1639,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.202.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Attributed to Sébastien Bourdon, The Adoration of the Magi, ca. 1639,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.202.4033.

Possibly Pierre Remy, Catalogue de Tableaux, de Différens Bons Maîtres des Trois Écoles, de Figures de Bronze, de Bustes de Marbre, d’Estampes montées sous verre, et d’Estampes en Feuilles, après le Décès de M. le Marquis de Villette, Pere [sic] (Paris: Didot, 1765), 10, as Une Adoration des Rois.

Possibly Catalogue des Tableaux du Cabinet de Monsieur ***: Sçavoir, Tableaux, Desseins, Estampes, Bronzes, Bustes de marbre, Gaînes de marbre et de bois, Porcelaines différentes, montées et non montées, Meubles, Pendules, Feux, Bras de cheminées, Secrétaires, etc. ([Paris]: Lebrun, 1766), 3, as l’Adoration des Rois.

Possibly F[rançois]-C[harles] Joullain, Catalogue d’une Précieuse Collection de Tableaux, Bronzes, Marbres, Porcelaines, Lacques, Pierres gravées et autres Pierres précieuses, Meubles et objets de curiosité, Provenans du Cabinet de M. le Doux. (Paris: Joullain, 1775), 26, as L’adoration des Rois.

Possibly C[harles]-F[rançois] Joullain, Réflexions sur la Peinture et la Gravure, accompagnées d’une Courte Dissertation sur le Commerce de la Curiosité, et les Ventes en Général; Ouvrage Utile aux Amateurs, aux Artistes et aux Marchands (Metz: Claude Lamort, 1786), 178, as Adoration des Rois.

Possibly Catalogue d’une Très-Belle Collection de Tableaux, d’Italie de Flandres, de Hollande, et de France; . . . Provenans du Cabinet de M. *** (Paris: Le Brun, 1787), 31-32, as L’Adoration des Rois.

Possibly J[ean-] B[aptiste-] P[ierre] Lebrun, Catalogue des Tableaux Formant le Cabinet de M. de Lareynière; Composé en partie des Tableaux des plus grands Maîtres de l’Ecole Française: on y distingue, par-dessus tout, les chef-d’œuvres de l’immortel Lemoyne, les seuls, pour ainsi dire, qui soient connus (Paris: Lebrun, 1792), 6, as L’adoration des Rois.

Possibly Catalogue d’une Belle Collection de Tableaux des Trois Écoles, Et autres Objets curieux; du Cabinet de M. *** (Paris: Paillet and Lejeune, 1797), 8-9, as l’Adoration des Mages.

Possibly Charles Blanc [and Adolphe Narcisse Thibaudeau], Le Trésor de la Curiosité: Tiré des Catalogues de Vente de Tableaux, Dessins, Estampes, Livres, Marbres, Bronzes, Ivoires, Terres Cuites, Vitraux, Médailles, Armes, Porcelaines, Meubles, Émaux, Laques et autres Objets d’Art (Paris: Jules Renouard, 1857), 1:305, as L’Adoration des Rois.

Possibly Théodore Lejeune, Guide Théorique et Pratique de l’Amateur de Tableaux: Études sur les Imitateurs et les Copistes des Maîtres de Toutes les Écoles dont les Œuvres Forment la Base Ordinaire des Galeries (Paris: Gide, 1863), 1:171, as L’Adoration des Rois.

Possibly Adolphe Siret, Dictionnaire Historique et Raisonné des Peintres de Toutes les Écoles depuis l’Origine de la Peinture jusqu’à nos Jours, 3rd ed. (Brussels: Principaux Libraires, 1883), 1:133, as Adoration des mages.

Possibly Charles Ponsonailhe, Sébastien Bourdon: Sa Vie et son Œuvre d’après des Documents Inédits Tirés des Archives de Montpellier (Paris: Jules Rouam, 1886), 312, as L’adoration des rois.

Possibly H[ippolyte] Mireur, Dictionnaire des Ventes d’Art faites en France et à l’Étranger pendant les XVIIIme et XIXme Siècles (Paris: Maison d’Éditions d’Œuvres Artistiques, 1911), 1:423–24, as L’adoration des rois.

“Notable Works of Art now on the Market,” Burlington Magazine 103, no. 705 (December 1961): (repro.), as Adoration of the Magi.

Vouet to Rigaud: French Masters of the Seventeenth Century, exh. cat. (New York: Finch College Museum of Art, 1967), (repro.), as The Adoration of the Magi.

G[eraldine] E[lizabeth] Fowle, The Biblical Paintings of Sébastien Bourdon (PhD diss., University of Michigan, 1970), 1:80–83, 190, (repro.); 2:iv, 88–90, 90n1, 91n2, 91n3, 92n4, 92n5, as Adoration of the Magi.

Important Paintings by Old Masters (New York: Christie, Manson and Woods, June 5, 1980), 22–23, (repro.), as attributed to Sebastian Bourdon, The Adoration of the Magi.

Musée du Louvre, Dessins français du XVIIe siècle: 83e exposition du Cabinet des Dessins, exh. cat. (Paris: Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 1984), 101, as Adoration des Mages.

Colin B. Bailey, “Aspects of the Patronage and the Collecting of French Painting in France at the End of the Ancien Régime” (PhD diss., University of Oxford, 1985), 1:373, 394n66; 2: (repro.), as L’Adoration des rois and Adoration of the Magi.

Donald Hoffmann, “Three New Works Grace Nelson Gallery,” Kansas City Star 106, no. 97 (January 12, 1986): 6K, (repro.), as The Adoration of the Magi.

“Seventeenth Century French Painting Given to Museum,” Calendar of Events (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (February 1986): 3–4, (repro.), as The Adoration of the Magi.

Hilliard T. Goldfarb, From Fontainebleau to the Louvre: French Drawing from the Seventeenth Century, exh. cat. (Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art, 1989), 183, 184n1, as The Adoration of the Magi.

Peter Tomory and Robert Gaston, European Paintings before 1800 in Australian and New Zealand Public Collections (Sydney: Beagle Press, 1989), 59, as Adoration of the Magi.

Ursula Hoff, European Paintings before 1800 in the National Gallery of Victoria, 4th ed. (Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 1995), 25n3, as Adoration of the Magi.

Heinz Widauer, “Sébastien Bourdon (1616–1671): die künstlerische Entwicklung seines Œuvres mit besonderer Berücksichtigung der Zeichnungen und Radierungen” (PhD diss., University of Vienna, 1999), 1:42; 2: (repro.), as Die Anbetung der Könige.

Jacques Thuillier, Sébastien Bourdon 1616–1671: Catalogue critique et chronologique de l’œuvre complet (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 2000), no. 68–II, p. 207, (repro.), as L’Adoration des mages.

Colin B. Bailey, Patriotic Taste: Collecting Modern Art in Pre-Revolutionary Paris (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002), 225, 307n112, as Adoration of the Magi.

Nicolas Sainte Fare Garnot, ed., Dessins Français aux XVIIe et XVIIIe Siècles: Actes du colloque, École du Louvre, 24 et 25 juin 1999 (Paris: École du Louvre, 2003), 152, 166n16, as L’Adoration des mages.

Album de Cartes Postales, Autographes et Manuscrits, Dessins et Tableaux des XVIème, XVIIème, XVIIIème et XIXème Siècle, Argenterie, Céramique, Mobilier et Objets d’Art, Tapis et Tapisseries (Paris: Cornette de Saint Cyr, June 22, 2011), 15.

Dessins, Tableaux anciens et du XIXème siècle, Argenterie, Art d’Asie, Malles Louis Vuitton, Mobilier et Objets d’Art, Tapis et Tapisserie (Paris: Cornette de Saint Cyr, December 14, 2011), 13.