![]()

Edouard Vuillard, The Large Fisherwoman at Low Tide, 1909

| Artist | Edouard Vuillard, French, 1868–1940 |

| Title | The Large Fisherwoman at Low Tide |

| Object Date | 1909 |

| Alternate and Variant Titles | Coast of Normandy; La Grosse Pêcheuse à marée basse |

| Medium | Pastel and charcoal on blue-gray, wove paper |

| Dimensions (Unframed) | 19 1/4 x 25 5/8 in. (48.9 x 65.1 cm) |

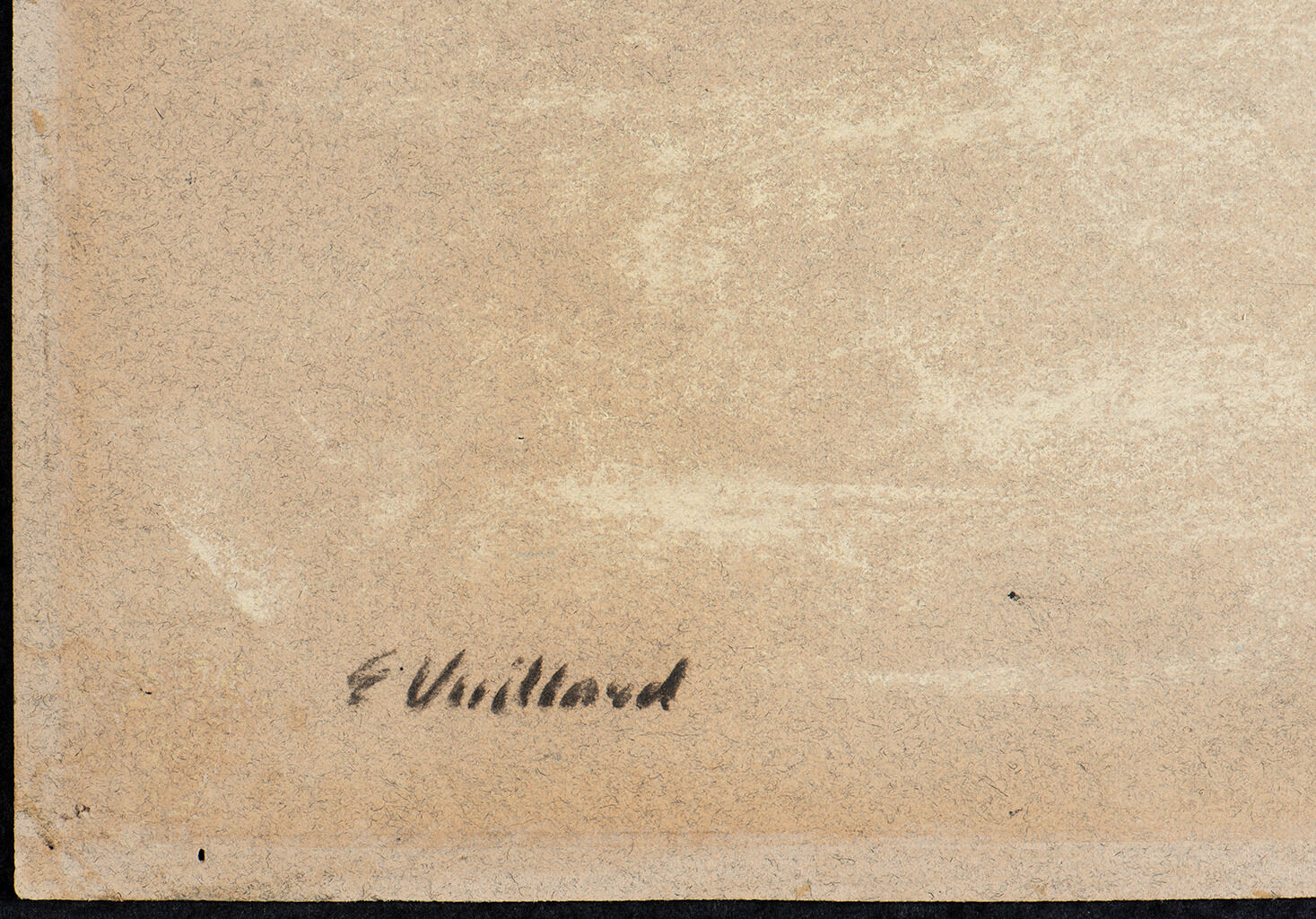

| Signature | Signed lower left: E Vuillard |

| Credit Line | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Gift of William Inge, 60-91 |

| Copyright | © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Kenneth Brummel, “Edouard Vuillard, The Large Fisherwoman at Low Tide, 1909,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.742.5407.

MLA:

Brummel, Kenneth. “Edouard Vuillard, The Large Fisherwoman at Low Tide, 1909,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.742.5407.

Conceived while Edouard Vuillard was wandering the tidal sand flats in the northern Breton town of Saint-Jacut-de-la-Mer, The Large Fisherwoman at Low Tide straddles the gap between the avant-garde movements of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century France. Greeting the viewer at lower left is a rectangle of sun-drenched sand described with broad, horizontal sweeps of pale-yellow pastelpastel: A type of drawing stick made from finely ground pigments or other colorants (dyes), fillers (often ground chalk), and a small amount of a polysaccharide binder (gum arabic or gum tragacanth). While many artists made their own pastels, during the nineteenth century, pastels were sold as sticks, pointed sticks encased in tightly wound paper wrappers, or as wood encased pencils. Pastels can be applied dry, dampened, or wet, and they can be manipulated with a variety of tools including paper stumps, chamois cloth, brushes, or fingers. Pastel can also be ground and applied as a powder, or mixed with water to form a paste. Pastel is a friable media, meaning that it is powdery or crumbles easily. To overcome this difficulty, artists have used a variety of fixatives to prevent image loss.. Just beyond, the viewer encounters a section of beach, shaped loosely into a trapezoid, that contains passages of rust highlighted with more gestural touches and flourishes, also in pale yellow. Framing this area is a C-shaped, multicolored band that includes a tidepool at left, a sloping, grassy dune at upper center, and a piece of mossy bedrock that crops the exposed legs of a woman harvesting oysters at center right. Before Vuillard added color and dimension to these naturalistically rendered forms, he drew their outlines in charcoal and matte black pastel. The houses on the high horizon line, for example, were first indicated with short black dashes before the artist laid in their slate-gray roofs and accented their exteriors with dabs of light blue, burnt umber, and canary yellow. Treating the sky in a far less linear fashion, Vuillard mostly blocked it in with long, horizontal strokes made with the side of a light-blue pastel stick, creating a large, shimmering triangle that recedes into pictorial space but also lies flat on the paper’s material surface.

Vuillard likely exhibited The Large Fisherwoman at Low Tide with forty-four other works he produced in Saint-Jacut-de-la-Mer at Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, Paris, in November 1909.1It may have been the picture listed as no. 20, La grosse pêcheuse, in Exposition Vuillard, exh. cat. (Paris: Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, 1909), 6. While there is a slim possibility that a closely related work, La Grosse Pêcheuse (ca. 1910; location unknown), was the one listed as no. 20 in the Bernheim-Jeune catalogue, Mathias Chivot, author of a forthcoming supplement to the Vuillard catalogue raisonné, believes it was the Nelson-Atkins pastel; Mathias Chivot to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, October 12, 2023, NAMA curatorial files. For a reproduction of the closely related pastel currently in private hands, see Catalogue of Impressionist and Modern Paintings, Drawings, and Sculpture (London: Sotheby’s, July 1, 1964), 97, lot no. 159. While one reviewer balked at the paintings and pastels on display, claiming they were unfinished,2Georges Bal, “M. Sternberg Davids Expose Galerie Petit,” New York Herald, November 3, 1909, 6. most critics commented on the artist’s reconciliation of naturalism and symbolism in this body of work. Calling Vuillard a “harmonist” who carefully calibrated his compositions, Arsène Alexandre, possibly referring to the subtle geometric shapes in The Large Fisherwoman at Low Tide, praised the artist’s “visionary ways of treating real objects and beings” and his “realistic way of rendering visions.”3Arsène Alexandre, “La vie artistique: Petites expositions,” Le Figaro, November 5, 1909, 7. “Ce sont des façons visionnaires de traiter les objets et les êtres réels ou, si l’on préfère, une façon réaliste de rendre des visions. M. Vuillard, et c’est là le secret de l’aventure, est né harmoniste” (These are visionary ways of treating real objects and beings or, if one prefers, a realistic way of rendering visions. Mr. Vuillard, and this is the secret of the adventure, was born a harmonist). All translations by Kenneth Brummel. François Thiébault-Sisson articulated a similar sentiment in his discussion of the “seascapes,” “landscape studies,” and “interiors with figures” that Vuillard executed in pastel. Noting how artists working in this medium are able to record momentary shifts in an object’s appearance, Thiébault-Sisson explained how Vuillard deftly captured such effects but always incorporated them into works that possess “delicacy” and “power.”4François Thiébault-Sisson, “Au jour le jour: Choses d’art,” Le Temps, November 10, 1909, [3]. “Nulle trace d’huile ni dans ses marines, ni dans ses études de paysage, ni dans ses intérieurs à figures. Il n’y a là que des pastels, d’une délicatesse qui n’exclut pas la puissance” (There is no trace of oil in his seascapes, landscape studies, or in his interiors with figures. There are only pastels, with a delicacy that does not exclude power). “Vuillard is a syntheticistSynthetism: Rejecting the Impressionist’s naturalistic approach to depicting observed reality, Paul Gauguin, Emile Bernard, and other Post-Impressionist artists working in and around the Breton town of Pont-Aven in the late 1880s formulated a more symbolic style of representation called “synthétisme” (synthetism). Utilizing thickly painted contours and flat planes of vibrant color, synthetist artists hoped to register their subjective, aesthetic responses to subject matter with purely formal devices. First exhibiting their works in 1889, the “groupe synthétiste” was founded in 1891. Paul Sérusier, who was involved with Synthetism, was also the founder of the Nabis. See also Nabis.,” Thiébault-Sisson wrote, “but a syntheticist solely preoccupied with the effects of light and color.”5Thiébault-Sisson, “Au jour le jour: Choses d’art.” “Vuillard est un synthétiste, mais un synthétiste uniquement occupé des effects de lumière et de couleurs.” Although Jacques-Félix Schnerb also mentioned the subject matter of Vuillard’s works, acknowledging that some are “summer landscapes” and “beaches,” he described them in purely Symbolist terms, stating that the artist used their depicted elements as pretexts to create “delicate,” decorative arrangements.6Jacques-Félix Schnerb, “Petites Expositions,” La Chronique des Arts et de la Curiosité, no. 35 (November 20, 1909): 281. “Paysages d’été, plages, scènes d’intérieur ne sont que des prétextes aux plus délicats arrangements, où les éléments pris au motif n’ont plus d’autre raison de figurer sur le panneau que celle de le décorer” (Summer landscapes, beaches, interior scenes are just pretexts for the most delicate arrangements, where the elements taken from the motif have no reason to appear on the panel than to decorate it). Reading Schnerb’s lopsided assessment of Vuillard’s Saint-Jacut-de-la-Mer output, one wonders if the art critic was only appraising some of the more abstract forms on view, such as the flat, blue triangle representing the sky in the Nelson-Atkins pastel.

While landscapes are not a genre normally associated with Vuillard, they begin to emerge in the artist’s oeuvre in 1900. The year 1900 is often described as a “turning point”7See, for example, Jeanine Warnod, E. Vuillard, trans. Marie-Hélène Agüeros (New York: Crown, 1989), 47; and Mathias Chivot, “The Turning Point. Light from Elsewhere: Holiday Landscapes,” in Édouard Vuillard et Ker-Xavier Roussel (1890–1944): Intimités en plain air / Private Moments in the Open Air: Paysages / Landscapes, ed. Mathias Chivot, exh. cat. (Milan: Silvana, 2017), 111. in Vuillard’s career, as the artist introduced natural light and perspectival space into his NabiNabis: Nabi is the Hebrew word for prophet. Founded by Paul Sérusier, the Nabis were a group of Post-Impressionist painters active in France from 1888 to around 1900. Utilizing a simplified style of thick, undulating contours and flat planes of vibrant color inspired by Synthetism, the Nabis rejected naturalistic depictions of reality and relied instead on metaphor and purely formal devices to evoke feelings and subject matter. An experimental group of painters, the Nabi created stage sets for Symbolist theatre productions and painted on unconventional supports such as velvet and cardboard. See also Synthetism.-style compositions and engaged in more direct observation of his depicted subjects around the turn of the century. Particularly foundational for Vuillard was an experience he had in L’Étang-la-Ville, a suburb west of Paris, on August 10, 1900. Spending time at the country home of his fellow Nabi painter and brother-in-law Ker-Xavier Roussel (1867–1944), Vuillard wrote to Nabi artist Félix Vallotton (Swiss, 1865–1925) that he was “amazed” to see the clouds shift in shape as the sky appeared “sometimes blue, sometimes gray, sometimes green.”8Gilbert Guisan and Doris Jakubec, eds., Félix Vallotton: Documents pour une biographie et pour l’histoire d’une œuvre (Paris: La Bibliothèque des Arts, 1974), 2:47–48. “Je suis étonné de voir le ciel tantôt bleu, tantôt gris, tantôt vert, et que les nuages ont des formes et des couleurs qui peuvent se classer, que sans se décarcasser à chercher des nuances il y a une grande jouissance à comprendre bonnement les choses” (I am amazed to see that the sky is sometimes blue, sometimes gray, sometimes green, and that the clouds have shapes and colors that can be classified, that without bothering to look for nuances there is a great pleasure in simply understanding things). Profoundly affected by this brush with fugitive nature, Vuillard went on to create what some scholars consider to be among his first pure landscape paintings, first in the environs of Vallotton’s home in Romanel, Switzerland, in late August–September 1900, and then in the southern French city of Cannes in the winter of 1900–01.9See, for example, MaryAnne Stevens and Kimberly Jones, “The Triumph of Light,” in Guy Cogeval, Édouard Vuillard, exh. cat. (Washington: National Gallery of Art, 2003), 284.

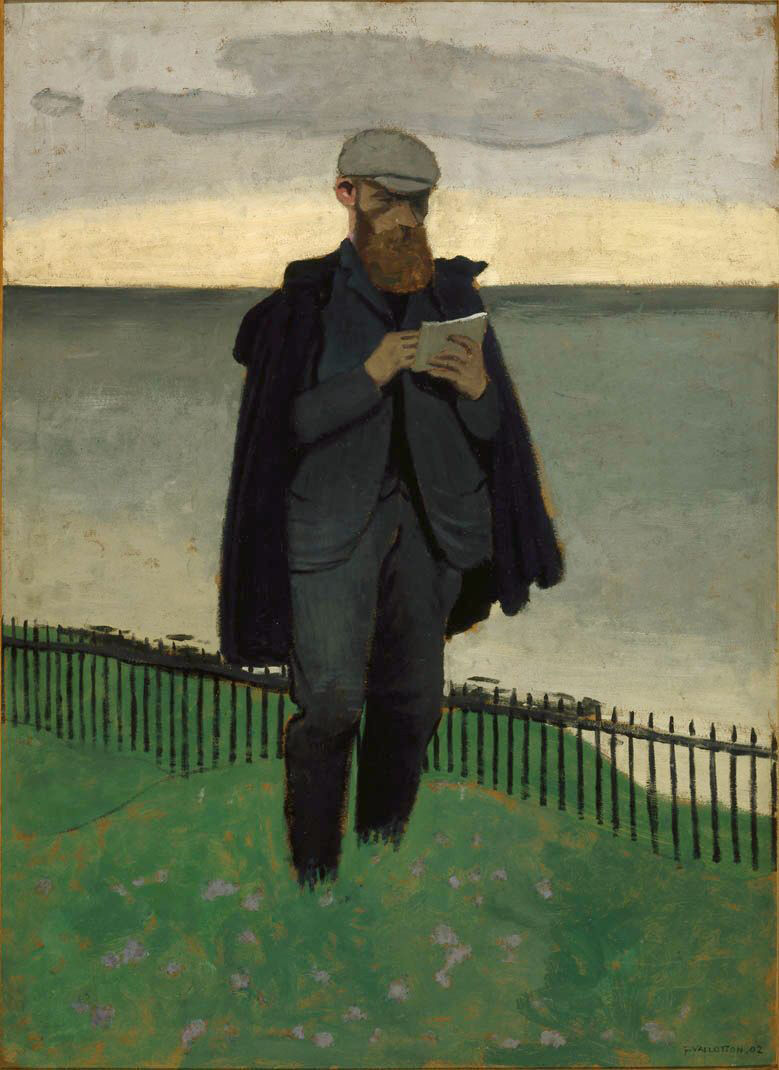

The long summer vacations Vuillard spent in the Norman and Breton countryside from 1901 to 1914 also fueled his interest in the genre of landscape after 1900. The extended length of these two- to three-month holidays enabled the artist to familiarize himself with his rural surroundings and establish a sense of communion with his chosen motifs and locations. In the summer of 1902, for example, Vuillard, as seen in Vallotton’s portrait Vuillard Drawing at Honfleur (Fig. 1), wandered Normandy’s Channel coast to jot down his impressions of that scenic landscape, sketchbook dutifully in hand.

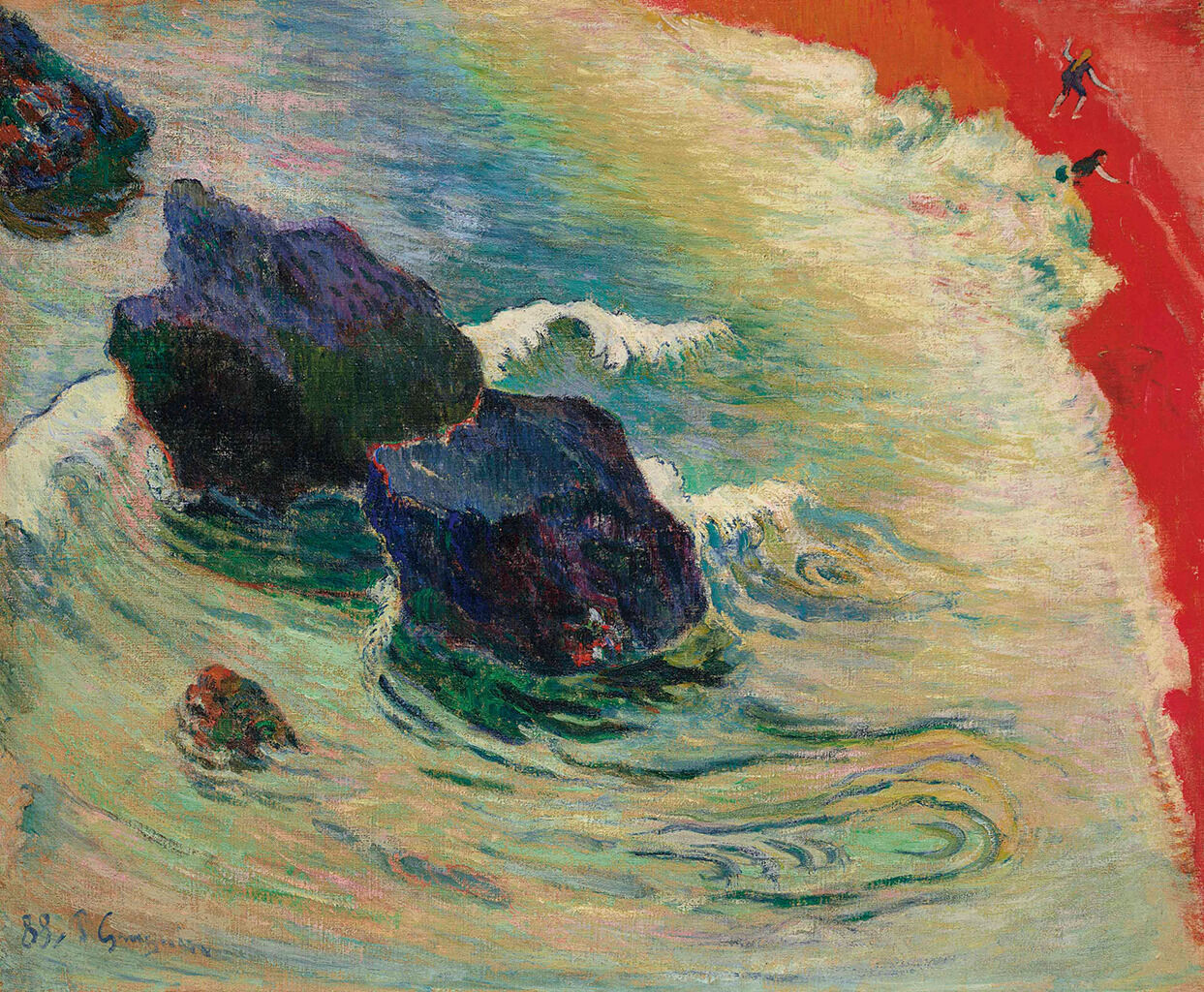

Fig. 4. Paul Gauguin, The Wave, 1888, oil on canvas, 23 3/4 x 28 5/8 in. (60.2 x 72.6 cm), private collection. Photo © Christie’s Images / Bridgeman Images

Fig. 4. Paul Gauguin, The Wave, 1888, oil on canvas, 23 3/4 x 28 5/8 in. (60.2 x 72.6 cm), private collection. Photo © Christie’s Images / Bridgeman Images

Fig. 5. Georges Braque, Trees at L’Estaque, summer 1908, oil on canvas, 31 5/8 x 23 11/16 in. (80.3 x 60.2 cm), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Promised Gift from the Leonard A. Lauder Cubist Collection, SL.17.2014.1.2. © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Fig. 5. Georges Braque, Trees at L’Estaque, summer 1908, oil on canvas, 31 5/8 x 23 11/16 in. (80.3 x 60.2 cm), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Promised Gift from the Leonard A. Lauder Cubist Collection, SL.17.2014.1.2. © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Notes

-

It may have been the picture listed as no. 20, La grosse pêcheuse, in Exposition Vuillard, exh. cat. (Paris: Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, 1909), 6. While there is a slim possibility that a closely related work, La Grosse Pêcheuse (ca. 1910; location unknown), was the one listed as no. 20 in the Bernheim-Jeune catalogue, Mathias Chivot, author of a forthcoming supplement to the Vuillard catalogue raisonné, believes it was the Nelson-Atkins pastel; Mathias Chivot to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, October 12, 2023, NAMA curatorial files. For a reproduction of the closely related pastel currently in private hands, see Catalogue of Impressionist and Modern Paintings, Drawings, and Sculpture (London: Sotheby’s, July 1, 1964), 97, lot no. 159.

-

Georges Bal, “M. Sternberg Davids Expose Galerie Petit,” New York Herald, November 3, 1909, 6.

-

Arsène Alexandre, “La vie artistique: Petites expositions,” Le Figaro, November 5, 1909, 7. “Ce sont des façons visionnaires de traiter les objets et les êtres réels ou, si l’on préfère, une façon réaliste de rendre des visions. M. Vuillard, et c’est là le secret de l’aventure, est né harmoniste” (These are visionary ways of treating real objects and beings or, if one prefers, a realistic way of rendering visions. Mr. Vuillard, and this is the secret of the adventure, was born a harmonist). All translations by Kenneth Brummel.

-

François Thiébault-Sisson, “Au jour le jour: Choses d’art,” Le Temps, November 10, 1909, [3]. “Nulle trace d’huile ni dans ses marines, ni dans ses études de paysage, ni dans ses intérieurs à figures. Il n’y a là que des pastels, d’une délicatesse qui n’exclut pas la puissance” (There is no trace of oil in his seascapes, landscape studies, or in his interiors with figures. There are only pastels, with a delicacy that does not exclude power).

-

Thiébault-Sisson, “Au jour le jour: Choses d’art.” “Vuillard est un synthétiste, mais un synthétiste uniquement occupé des effects de lumière et de couleurs.”

-

Jacques-Félix Schnerb, “Petites Expositions,” La Chronique des Arts et de la Curiosité, no. 35 (November 20, 1909): 281. “Paysages d’été, plages, scènes d’intérieur ne sont que des prétextes aux plus délicats arrangements, où les éléments pris au motif n’ont plus d’autre raison de figurer sur le panneau que celle de le décorer” (Summer landscapes, beaches, interior scenes are just pretexts for the most delicate arrangements, where the elements taken from the motif have no reason to appear on the panel than to decorate it).

-

See, for example, Jeanine Warnod, E. Vuillard, trans. Marie-Hélène Agüeros (New York: Crown, 1989), 47; and Mathias Chivot, “The Turning Point. Light from Elsewhere: Holiday Landscapes,” in Édouard Vuillard et Ker-Xavier Roussel (1890–1944): Intimités en plain air / Private Moments in the Open Air: Paysages / Landscapes, ed. Mathias Chivot, exh. cat. (Milan: Silvana, 2017), 111.

-

Gilbert Guisan and Doris Jakubec, eds., Félix Vallotton: Documents pour une biographie et pour l’histoire d’une œuvre (Paris: La Bibliothèque des Arts, 1974), 2:47–48. “Je suis étonné de voir le ciel tantôt bleu, tantôt gris, tantôt vert, et que les nuages ont des formes et des couleurs qui peuvent se classer, que sans se décarcasser à chercher des nuances il y a une grande jouissance à comprendre bonnement les choses” (I am amazed to see that the sky is sometimes blue, sometimes gray, sometimes green, and that the clouds have shapes and colors that can be classified, that without bothering to look for nuances there is a great pleasure in simply understanding things).

-

See, for example, MaryAnne Stevens and Kimberly Jones, “The Triumph of Light,” in Guy Cogeval, Édouard Vuillard, exh. cat. (Washington: National Gallery of Art, 2003), 284.

-

Edouard Vuillard, journal, May 18, 1909–February 3, 1910, Ms 5397 (3), Bibliothèque de l’Institut de France, Paris, https://bibnum.institutdefrance.fr/ark:/61562/bi24420, entry for July 16, 1909, folio 14r: “La petite Denise Guillaume. À la plage / peu [?] la petite maison voisine, chemin en S. Marée basse. Pêcheuse / aux belles jambes” (Little Denise Guillaume. At the beach / near [?] the small neighboring house, path in S. Low tide. Fisherwoman / with beautiful legs).

-

Vuillard mentions visiting the Plage de Rougeret in the entries for July 13, 23, and 25, 1909, in his journal. See Vuillard, journal, Ms 5397 (3), folios 13r, 15v, and 16r.

-

For a discussion of this other pastel, see n. 1.

-

Claude Roger-Marx, Vuillard: His Life and Work, trans. E. B. d’Auvergne (London: Paul Elek, 1946 [1945]), 141.

-

See, for example, Belinda Thomson, Vuillard (New York: Abbeville Press, 1988), 110; and Warnod, E. Vuillard, 47.

-

Dieter Schwartz, “Die Bretagne–Vuillard’s Japan,” in Édouard Vuillard, 1868–1940, ed. Dieter Schwartz, exh. cat. (Zurich: Kunstmuseum Winterthur, 2014), 215.

-

Mathias Chivot, notes on La Vague (1909), in Chivot, Édouard Vuillard et Ker-Xavier Roussel, 128.

-

Edouard Vuillard, journal, October 1, 1908–May 17, 1909, Ms 5397 (2), Bibliothèque de l’Institut de France, Paris, https://bibnum.institutdefrance.fr/ark:/61562/bi24424, entry for November 25, 1908, folio 19r. Georges Braque’s Trees at L’Estaque (1908; Metropolitan Museum of Art) was exhibited as no. 4, 20, 21, or 22 in in his exhibition at Galerie Kahnweiler, Paris, November 9–28, 1908. See Exposition Georges Braque (Paris: Galerie Kahnweiler, 1908), [5] and [7].

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Rachel Freeman, “Edouard Vuillard, The Large Fisherwoman at Low Tide, 1909,” technical entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.742.2088.

MLA:

Freeman, Rachel. “Edouard Vuillard, The Large Fisherwoman at Low Tide, 1909,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.742.2088.

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art’s collection of French pastel paintings includes two works on paper by Edouard Vuillard: The Large Fisherwoman at Low Tide (1909) and Woman in a Red Dress, or J. R. Against a Window (ca. 1899). Both artworks explore the Nabis’Nabis: Nabi is the Hebrew word for prophet. Founded by Paul Sérusier, the Nabis were a group of Post-Impressionist painters active in France from 1888 to around 1900. Utilizing a simplified style of thick, undulating contours and flat planes of vibrant color inspired by Synthetism, the Nabis rejected naturalistic depictions of reality and relied instead on metaphor and purely formal devices to evoke feelings and subject matter. An experimental group of painters, the Nabi created stage sets for Symbolist theatre productions and painted on unconventional supports such as velvet and cardboard. See also Synthetism. matte aesthetic through different mediums: pastel and oil, respectively. In the curatorial entry for the artwork, Kenneth Brummel outlines the genesis of the composition and identifies the cohort artworks from the artist’s oeuvre. This entry reinforces the notion that The Large Fisherwoman at Low Tide was likely the result of keen observation of the outdoors followed by several sessions in the studio to complete a finished product.

The black pastel or compressed charcoalcompressed charcoal: A dry drawing material composed of charcoal, ground to a powder, and formed into a stick with aid of a small amount of a non-waxy and non-oily binder. The line created by compressed charcoal is characterized by a firm and dense appearance. underdrawingunderdrawing: A drawn or painted sketch beneath the paint layer. The underdrawing can be made from dry materials, such as graphite or charcoal, or wet materials, such as ink or paint. has a fast, gestural quality, and Vuillard was not shy about allowing the outlines to dominate areas of the composition. The fisherwoman at far right is not immediately apparent, even though she may have been an initial anchor for the composition, as the outlines of her legs extend into the rocks (Fig. 7).

Vuillard’s palette is evocative of a bright day with light reflecting off sand and water, and the colors he chose may be the result of the study of the landscape and architecture of the seashore, as well as the garb of people who work close to the water. Foreground colors are simplified to muted browns, ochers and reds, grays, light yellows, and black. The beach consists of sparsely applied yellow and dull-red pastels, with a muted blue to indicate shallow tidal pools. Toward the fore edge of the paper, the pastel application thins and the color of the paper dominates. Green and light blue in the background contrast with the palette of the beach and fisherwoman and emphasize the distant horizon. The background and hillside have some solidity due to heavily applied dark green pastel color. Brighter greens and olive tones applied in strokes of varying weight indicate grass and other foliage. Objects seen from a distance, such as the houses, are indicated with just a few strokes of blue and a rusty red, often applied over black to create a gray. The horizon is a gently blurred black line.

In 2013, paper conservator Nancy Heugh used a fine brush and magnification to test the stability of the pastels.6Nancy Heugh, “French Painting Catalogue Project Technical Examination and Condition Report,” March 29, 2016, NAMA conservation file, no. 60-91. She learned that many areas of the design were either partially or well fixed. The fixativefixative: An adhesive or varnish that is applied to the surface of powdery media (pastel, chalk, charcoal, or graphite pencil) to prevent smudging or smearing. Fixatives may be applied during the composition process, so that new layers of media can be added without disturbing the underlayers, or after the artwork is complete. Historic fixatives include natural resins, vegetable gums or starches, animal or fish glues, casein, egg white, and a variety of other materials. In the nineteenth century, cellulose nitrate and other early synthetic polymers were available, and in the twentieth century, acrylics and polyvinyl co-polymers were included in fixative solutions. Until the early twentieth century, when methods for containing pressurized gasses were developed and disposable spray cans became common, the fixative could be spattered over the paper with a brush or applied with an atomizer (also called a blow-pipe or mouth sprayer). appears to have been applied as a fine mist, although its composition is unknown. The degree of media friabilityfriable: When paint is no longer sufficiently bound. Friable paint often appears powdery or crumbles easily. appears to correspond with time of application: the earliest portions of the composition received repeated application of fixative, while the last areas to be completed remain friable. The black pastel outlines, the yellow within the beach, areas of the sky, and the houses are not powdery. They were likely applied early in the composition process. The landscape, portions of the fisherwoman, and some of the sand are friable and were probably applied late or last in execution.

Vuillard signed the artwork in vine charcoalvine or willow charcoal: Long, thin charcoal sticks created by burning grape vines or willow twigs in a low carbon environment. Vine and willow charcoal produce brown to black shades. With magnification, the pastel particles often have a splintered appearance and display a characteristic sparkle. at lower left. This is the only incidence of the media in the artwork. The signature is well adhered to the paper and underlying layers of pastel and may have been fixed post execution (Fig. 8).

Notes

-

The description of paper color, texture, and thickness follows the standard set forth in Elizabeth Lunning and Roy Perkinson, The Print Council of America Paper Sample Book: A Practical Guide to the Description of Paper (Boston: Print Council of America, 1996), unpaginated. In the case of The Large Fisherwoman at Low Tide, the paper color does not have a match in the sample book.

-

In paper production, “size” refers to a mild waterproofing agent that improves resistivity to liquids and thereby prepares the paper for the application of ink or paint. During the late nineteenth century, papers were either internally sized (also known as engine sized) by adding the agent to the paper pulp; or they were tub-sized by dipping the paper into a sizing vat after sheet production. See E. J. Labarre, A Dictionary of Paper and Paper-Making Terms (Amsterdam: N. V. Swets and Zeitlinger, 1937), 141, 210, and 303.

-

References and price lists for “grand-raisin” size papers manufactured in France specifically for pastel use were located in Fabrique de Couleurs et Vernis, Toiles à Peindre, Carmin, Laques, Jaunes de Chrome de Spooner, Couleurs en Tablettes et en Pastilles, Pastels, et Généralment Tout Ce Qui Concerne la Peinture et les Arts, Encres Noires et de Couleurs Pour la Typograpie et la Lithographie, Fabrique à Grenelle (Paris: Le Franc, 1862), 40.

-

A dandy-roll is a “roll or cylinder, covered with wire gauze . . . which presses gently on the paper while still wet.” It produces texture, watermark impressions, and other embossments. See Labarre, A Dictionary of Paper and Paper-Making Terms, 129.

-

Mottled papers were composed of mixed furnish taken from various sources such as dyed linen, cotton, Union (fabric made from a linen, wool, or cotton warp and a wool weft), and wool rags or fibers, as well as jute fibers and dyed or bleached sulphite wood pulps. See Julius Erfurt, The Dying of Paper Pulp (London: Scott, Greenwood and Co., 1901), 141–52.

-

Nancy Heugh, “French Painting Catalogue Project Technical Examination and Condition Report,” March 29, 2016, NAMA conservation file, no. 60-91.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Edouard Vuillard, The Large Fisherwoman at Low Tide, 1909,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.742.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Edouard Vuillard, The Large Fisherwoman at Low Tide, 1909,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.742.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Edouard Vuillard, The Large Fisherwoman at Low Tide, 1909,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.742.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Edouard Vuillard, The Large Fisherwoman at Low Tide, 1909,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.742.4033.

Possibly purchased from the artist by Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, Paris, stock no. 17689, as La Grosse Pêcheuse à marée basse, October 9, 1909–July 22, 1919 [1];

Possibly purchased from Bernheim-Jeune by Léon Marseille, Paris, 1919 [2];

Probably with Schoneman Galleries Inc., New York [3];

William Motter Inge (1913–73), New York, by February 1, 1958–December 31, 1960 [4];

Given by Inge to The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1960.

Notes

[1] Vuillard created two nearly identical versions of The Large Fisherwoman at Low Tide. Their provenance narratives are conflated in the Vuillard catalogue raisonné; see Antoine Salomon and Guy Cogeval, Vuillard, The Inexhaustible Glance: Critical Catalogue of Paintings and Pastels (Milan: Skira, 2003), no. VIII-335, p. 2:980. It is unclear which version was sold by Galerie Bernheim-Jeune in 1909 as La Grosse Pêcheuse à marée basse. No Bernheim-Jeune labels or inscriptions are present on the verso of the Nelson-Atkins pastel; nevertheless, Mathias Chivot, author of a forthcoming supplement to the Vuillard catalogue raisonné, believes that Bernheim-Jeune owned the Kansas City version, not the version in private hands. See email from Mathias Chivot, independent scholar, to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, October 12, 2023, NAMA curatorial files. Special thanks to Darragh O’Donoghue, Tate Library and Archive, and Thomas Graham, Waddington Custot, for their help in detangling the ownership histories of the two pastels.

[2] For the purchaser, see the following letters: Guy-Patrice Dauberville, Bernheim-Jeune et Cie, to Glynnis Stevenson, NAMA, October 17, 2017; Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, to Guy-Patrice Dauberville, Bernheim-Jeune et Cie, July 27, 2023; and Guy-Patrice Dauberville, Bernheim-Jeune et Cie, to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, September 18, 2023. Léon Marseille operated a gallery with Charles Vildrac at 16 rue de Seine, Paris.

[3] Schoneman Galleries Inc. was founded in 1940 by Dr. Joseph S. Schoneman (1885–1970). After the dealer’s death, his widow Irene Schoneman (née Koopmann, 1894–1972) continued the family business until her own passing two years later. It is unclear when Schoneman Galleries closed or what became of its archives. Extant correspondence confirms that Schoneman Galleries shipped The Large Fisherwoman at Low Tide to the Nelson-Atkins on behalf of William Inge on January 6, 1961, suggesting that Inge had acquired the pastel from them. See letter from Joseph Schoneman to Laurence Sickman, January 6, 1961, NAMA curatorial files.

[4] Inge began collecting modern art shortly after his move from St. Louis to New York City in July 1949; see Ralph F. Voss, A Life of William Inge: The Strains of Triumph (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 1989), 117. He owned The Large Fisherwoman at Low Tide by February 1, 1958, when his new homeowner insurance policy took effect. See Personal Article Floater—Supplemental Policy, Travelers Indemnity, policy no. DC 6621796, February 1, 1958–February 1, 1961, papers of William Inge, collection of his great-niece Paula Brown, copy in NAMA curatorial files. Special thanks to Sophie Ong, Brian P. Kennedy Leadership Fellow, Toledo Museum of Art, for photographing Inge’s records.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Edouard Vuillard, The Large Fisherwoman at Low Tide, 1909,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.742.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Edouard Vuillard, The Large Fisherwoman at Low Tide, 1909,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.742.4033.

Édouard Vuillard, La Grosse Pêcheuse, ca. 1910, pastel on paper, 19 x 25 in. (48 x 63.5 cm), whereabouts unknown, illustrated in Catalogue of Impressionist and Modern Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture (London: Sotheby’s, July 1, 1964), 97.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Edouard Vuillard, The Large Fisherwoman at Low Tide, 1909,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.742.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Edouard Vuillard, The Large Fisherwoman at Low Tide, 1909,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.742.4033.

Possibly Exposition Vuillard, Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, Paris, November 2–20, 1909, no. 20, as La grosse pêcheuse.

Possibly Coming of Age: Retrospective of the Friends of Art Collection, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, September 12–October 3, 1976, no cat.

From Farm to Table: Impressionist and Post-Impressionist Masterworks on Paper, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, March 16, 2018–March 24, 2019, no cat.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Edouard Vuillard, The Large Fisherwoman at Low Tide, 1909,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.742.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Edouard Vuillard, The Large Fisherwoman at Low Tide, 1909,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.742.4033.

Possibly Exposition Vuillard, exh. cat. (Paris: Bernheim-Jeune et Cie, 1909), 6, as La grosse pêcheuse.

Possibly Donald E. Gordon, Modern Art Exhibitions, 1900–16: Selected Catalogue Documentation (Munich: Prestel, 1974), 2:349, as La grosse pêcheuse.

Donald Hoffmann, “Tracing the Ups and Downs of the Friends of Art,” Kansas City Star 97, no. 2 (September 19, 1976): 4E, as Coast of Normandy.

Antoine Salomon and Guy Cogeval, Vuillard, Le Regard innombrable: Catalogue critique des peintures et pastels (Paris: Wildenstein Institute, 2003), no. VIII-335, pp. 2:980, 3:1664, 1702, 1714, 1720, 1726–27, 1741, (repro.), as La Grosse Pêcheuse à marée basse.

Antoine Salomon and Guy Cogeval, Vuillard, The Inexhaustible Glance: Critical Catalogue of Paintings and Pastels (Milan: Skira, 2003), no. VIII-335, pp. 2:980, 3:1664, 1699, 1714, 1720, 1726, 1728, and 1741, (repro.), as The Fat Fisherwoman at Low Tide.