![]()

Vincent van Gogh, Restaurant Rispal at Asnières, 1887

| Artist | Vincent van Gogh, Dutch, 1853–90 |

| Title | Restaurant Rispal at Asnières |

| Object Date | 1887 |

| Alternate and Variant Titles | Vue d’Asnières, avec Marronniers en fleurs; Le restaurant Rispal à Asnières |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (Unframed) | 28 7/8 x 23 5/8 in. (73.3 x 60.0 cm) |

| Credit Line | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Gift of Henry W. and Marion H. Bloch, 2015.13.10 |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Meghan L. Gray, “Vincent van Gogh, Restaurant Rispal at Asnières, 1887,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.736.5407.

MLA:

Gray, Meghan L. “Vincent van Gogh, Restaurant Rispal at Asnières, 1887,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.736.5407.

In this sunny scene in Asnières, France, Vincent van Gogh (1853–90) has depicted a simple riverside restaurant with vibrant complementary colors. A tall, creamy building, set diagonally to the picture plane, dominates the scene. Its name, Restaurant Rispal, is spelled out in blue capital letters on its gabled side, while two orange signs in the shaded depths to the right of the building repeat the establishment’s name and advertise “VINS” (wines). The restaurant is capped by four red-and-orange chimneys and punctuated by ten windows framed with light green shutters. Verdant green cypress and chestnut trees border the building. Strolling along the golden street in the foreground are several patrons; one in a white shirt and straw hat heads toward the restaurant door, and another in a dark blue suit and top hat struts awkwardly toward the viewer.

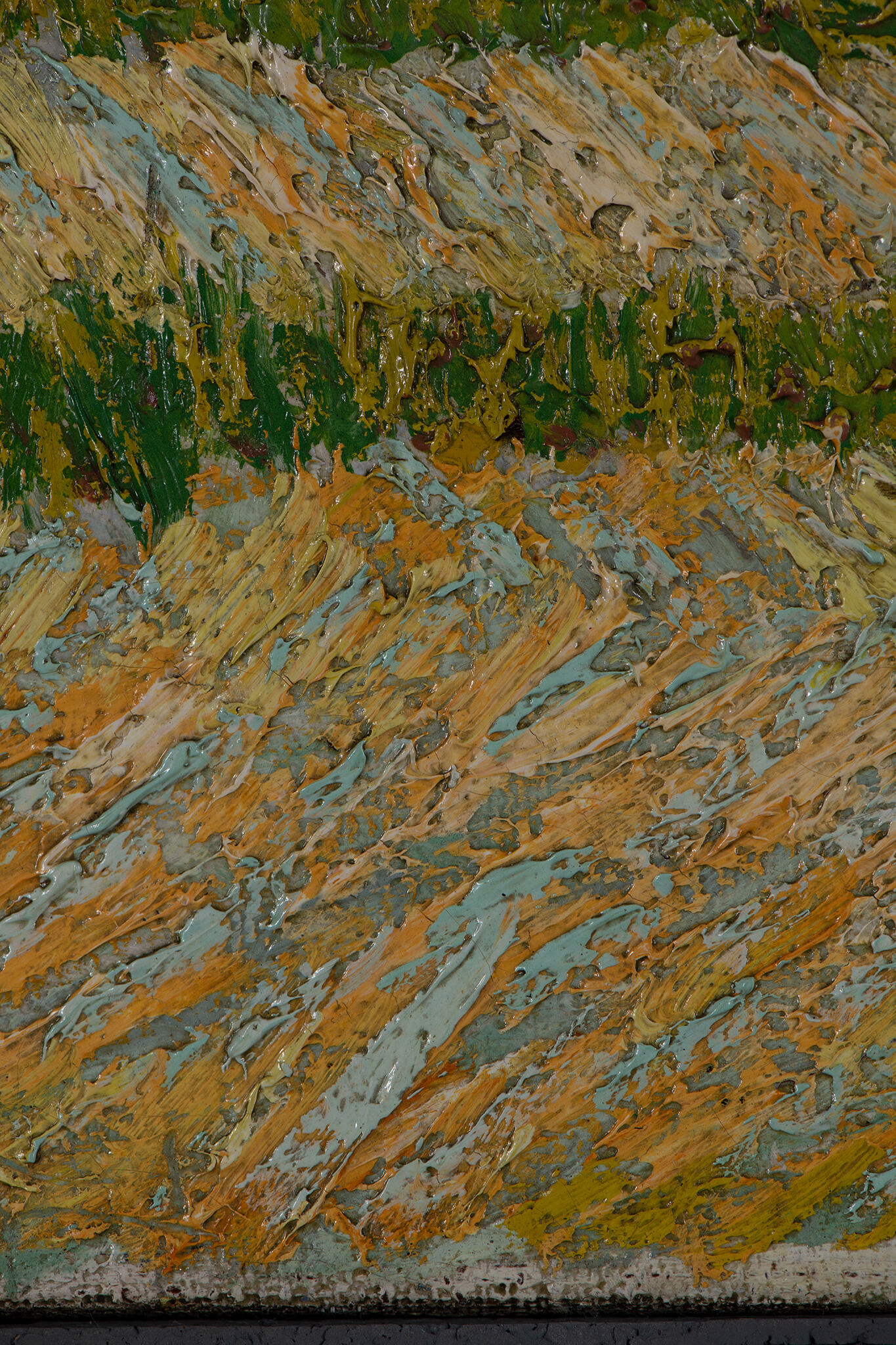

The artist’s unusual choice to turn the canvas vertically for a landscape subject better frames the three-story structure and allows the blue, cloud-filled sky to dominate half the scene. Always with a mind toward salability, Van Gogh may have hoped to inspire city-dwellers to buy his airy painting.1Van Gogh wrote to Theo about other Asnières landscapes on view at his friend “Père” Tanguy’s shop, “I’m well aware that these big, long canvases are hard to sell, but in time people will see that there’s open air and good cheer in them. Now the whole lot will make a decoration for a dining room or a house in the country.” Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, between about Saturday, July 23, and Monday, July 25, 1887, published in Leo Jansen, Hans Luijten, and Nienke Bakker, eds., Vincent Van Gogh: The Letters, online edition (Amsterdam and The Hague: Van Gogh Museum and Huygens, 2009), no. 572, http://vangoghletters.org/en/let572. All English translations are from this publication. Van Gogh enlivened the scene with dynamic strokes of paint, varying the direction of the brushstrokes to contour and define each subject. In the sky, the artist used long, horizontal strokes of blue, aqua, and white paint. The shaded restaurant wall is composed of crosshatched dashes of yellow, peach, aqua, and lavender, while the street is rendered in diagonal stripes of yellow-orange and pale blue. Van Gogh painted the trees impressionistically in short dabs of creamy white, tints of green, and accents of burnt sienna. Throughout the painting, complementary colors predominate: yellow-orange and blue in the road, lavender and yellow in the building, red and green in the adjacent buildings and trees. This technique, combined with Van Gogh’s modern application of paint, is indicative of his formative move away, both literally and artistically, from Dutch tradition.

Having decided at the age of twenty-seven to become an artist, Van Gogh committed wholeheartedly to the endeavor. He spent most of his life as an itinerant painter, living off an allowance from his art dealer brother, Theo (1857–91), to whom he sent all of his artwork. After two years living in Neunen—a town in the Netherlands—and in Antwerp, Van Gogh somewhat suddenly moved in with Theo in his small apartment in Paris in 1886.2See Vincent van Gogh, Paris, to Theo van Gogh, on or about Sunday, February, 28, 1886, in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 567, http://vangoghletters.org/en/let567. The move was formative for Van Gogh’s artistic career, as he became friends with young French artists like Émile Bernard (1868–1941) and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864–1901) and visited important shows like the Eighth Impressionist Exhibition.

In the late spring of 1887, Van Gogh walked the one-hour journey from his apartment at 54 rue Lepic, Paris, across the River Seine to Asnières, a Parisian suburb popular with daytrippers and boaters. Both Bernard and Signac had family homes in Asnières, and they remembered painting with him in the town that spring. Signac recalled, “We painted on the banks of the river and ate in a country café, and we returned to Paris on foot, through the streets of Saint-Ouen and Clichy. Van Gogh wore a blue zinc worker’s smock and had painted colored smudges on the sleeves. Pressed closely against me, he walked along, shouting and gesticulating, waving his freshly painted oversize canvas, smearing paint on himself and the passersby.”7Gustave Coquiot, Vincent van Gogh (Paris: Ollendorff, 1923), 140 (repr. in English in Jan Hulsker, The Complete Van Gogh: Paintings, Drawings, Sketches [New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1980], 282.)

Asnières was popular for boating and swimming, and known for the industrial modernity of the factories across the river at Clichy, but Van Gogh chose not to depict those subjects in this painting. Instead, with his back to the Seine, Van Gogh painted the heart of social life for lower- and middle-class visitors and residents of Asnières: a restaurant. This suburban scene was a modern subject for an artist of the time; it was not an industrialized landscape, like those of the Impressionists a generation earlier, nor a forested scene like those of the Barbizon painters before them, and it was certainly not an academically sanctioned subject from the Bible, history, or mythology.

Indeed, Van Gogh often ended his day at a café, where, according to Signac, “the absinthes and brandies would follow each other in quick succession.”10Hendriks and Van Tilborgh, Vincent van Gogh Paintings, 2:319. This lifestyle was new for Van Gogh. While living in the Netherlands, he aspired to an ideal of a sober and industrious life. But after his move to Paris, Van Gogh adopted a bohemian existence—smoking, drinking, carousing with courtesans, and visiting the cabarets and cafés of the city.11Louis van Tilborgh, “The Bedroom,” in Gloria Groom, ed., Van Gogh’s Bedrooms, exh. cat. (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2016), 56–57. In fact, Van Gogh confessed to Paul Gauguin that he was “very, very upset, quite ill and almost an alcoholic through overdoing it.”12Vincent van Gogh, Arles, to Paul Gauguin, Wednesday, October 3, 1888, in Jansen et al., Letters, http://vangoghletters.org/en/let695. Some of his experiences he saw reflected in Realist novels, like Emile Zola’s L’Assommoir (1877), which describes an entrepreneurial laundress whose life is ruined by drunkenness.13Vincent van Gogh, Paris, to Willemien van Gogh, late October 1887, in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 574, http://vangoghletters.org/en/let574. Van Gogh may have had the novel in mind when he depicted the street in Asnières with the Restaurant Rispal. In fact, he admitted the correlation between the book and his painting, The Yellow House (Fig. 4), which he completed a year later in September 1888.14Vincent van Gogh, Arles, to Theo van Gogh, on or about Saturday, September 29, 1888, in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 691, http://vangoghletters.org/en/let691. Van Gogh mentioned that “Zola did a certain boulevard at the beginning of L’Assommoir.” Part of the description in Zola’s novel is reminiscent of the Nelson-Atkins painting: “The hotel was situated on the Boulevard de la Chapelle, to the left of the Barrière Poissonnière. It was a building of two stories high . . . with shutters all rotted by the rain. Over a lamp with starred panes of glass, one could manage to read, between the two windows, the words, ‘Hôtel Boncœur, kept by Marsoullier,’ painted in big yellow letters, several pieces of which the mouldering of the plaster had carried away.” Émile Zola, The “Assommoir”: (The Prelude to “Nana”): A Realistic Novel (1877; English repr. London: Vizetelly, 1884), 10. The two paintings are strikingly similar, with their green-shuttered buildings set obliquely to the picture plane, the large expanse of blue sky in juxtaposition to the yellow road, and the villagers strolling in front. In both pictures, Van Gogh portrayed a real-life location of prime importance to his own world as well as the towns’ social fabrics.

The painting remained unsold for many years. Van Gogh’s sister-in-law, Johanna Van Gogh-Bonger (1862–1925), became the artist’s de facto dealer after his death in 1890 and Theo’s in 1891. She and her son, Vincent Willem (1890–1978), exhibited the painting at least seventeen times before it found a buyer in Nathan Charles Beechman (ca. 1861–1935), a British collector, in 1927. A few years later, the Jewish German dealer Hugo Moser (1881–1972) purchased the painting for his personal collection. Moser and his family fled the Nazis in 1933, sending the painting ahead of them to the United States. In 1979, Midwestern collectors Marion and Henry Bloch bought the painting from the Moser family at auction and hung it prominently in their home, where it provided a sunny spot of color over their fireplace. In 2015, the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art accepted the generous donation of the Bloch family collection, a star of which is Restaurant Rispal. The painting serves as an important visual bridge from Van Gogh’s darker Dutch campaign to the bright, Post-Impressionist phase of his career, in which he successfully incorporated strokes of complementary colors and a modern subject into a sparkling reminder of a spring day in Asnières.

Notes

-

Van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo about other Asnières landscapes on view at his friend “Père” Tanguy’s shop, “I’m well aware that these big, long canvases are hard to sell, but in time people will see that there’s open air and good cheer in them. Now the whole lot will make a decoration for a dining room or a house in the country.” Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, between about Saturday, July 23, and Monday, July 25, 1887, published in Leo Jansen, Hans Luijten, and Nienke Bakker, eds., Vincent Van Gogh: The Letters, online edition (Amsterdam and The Hague: Van Gogh Museum and Huygens, 2009), no. 572, http://vangoghletters.org/en/let572. All English translations are from this publication.

-

See Vincent van Gogh, Paris, to Theo van Gogh, on or about Sunday, February, 28, 1886, in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 567, http://vangoghletters.org/en/let567.

-

See Hendriks’s chapter on “Developing Technique and Style” in Ella Hendriks and Louis van Tilborgh, Vincent van Gogh Paintings, vol. 2, Antwerp and Paris 1885–1888, Van Gogh Museum, trans. Michael Hoyle (Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum, 2011), 146.

-

See Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, Nuenen, on or about Saturday, April 18, 1885, in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 494, http://vangoghletters.org/en/let494.

-

Theo van Gogh to Elisabeth van Gogh, Sunday, May 15, 1887, in Jansen et al., Letters, http://www.vangoghletters.org/vg/documentation.html. “Vincent is still working hard and is making progress. His paintings are becoming lighter, and his great quest is to get sunlight into them. He’s an odd fellow, but what a head he has on him, it’s enviable.”

-

See Vincent van Gogh, Arles, to Willemien van Gogh, between Saturday, June 16, and Wednesday, June 20, 1888, in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 626, http://vangoghletters.org/en/let626; and Vincent van Gogh, Paris, to Horace Mann Livens, September or October 1886, in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 569, http://vangoghletters.org/en/let569.

-

Gustave Coquiot, Vincent van Gogh (Paris: Ollendorff, 1923), 140 (repr. in English in Jan Hulsker, The Complete Van Gogh: Paintings, Drawings, Sketches [New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1980], 282.)

-

Restaurant Rispal was located beside the river at 117 Boulevard de la Seine (now Quai Aulagnier). Joachim Pissarro notes in his entry on this painting that the Restaurant Rispal might have been entirely forgotten had Van Gogh not immortalized it in paint. Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 114.

-

Many of Van Gogh’s flower still lifes that were on view at Le Tambourin in late July were sold in an auction when that business went bankrupt. See Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, Paris, between about Sunday, July 17, and Tuesday, July 19, 1887, in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 571, http://vangoghletters.org/en/let571.

-

Hendriks and Van Tilborgh, Vincent van Gogh Paintings, 2:319.

-

Louis van Tilborgh, “The Bedroom,” in Gloria Groom, ed., Van Gogh’s Bedrooms, exh. cat. (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2016), 56–57.

-

Vincent van Gogh, Arles, to Paul Gauguin, Wednesday, October 3, 1888, in Jansen, et al., Letters, no. 695, http://vangoghletters.org/en/let695.

-

Vincent van Gogh, Paris, to Willemien van Gogh, late October 1887, in Jansen, et al., Letters, no. 574, http://vangoghletters.org/en/let574.

-

Vincent van Gogh, Arles, to Theo van Gogh, on or about Saturday, September 29, 1888, in Jansen et al., Letters, no. 691, http://vangoghletters.org/en/let691. Van Gogh mentioned that “Zola did a certain boulevard at the beginning of L’Assommoir.” Part of the description in Zola’s novel is reminiscent of the Nelson-Atkins painting: “The hotel was situated on the Boulevard de la Chapelle, to the left of the Barrière Poissonnière. It was a building of two stories high . . . with shutters all rotted by the rain. Over a lamp with starred panes of glass, one could manage to read, between the two windows, the words, ‘Hôtel Boncœur, kept by Marsoullier,’ painted in big yellow letters, several pieces of which the mouldering of the plaster had carried away.” Emile Zola, The “Assommoir”: (The Prelude to “Nana”): A Realistic Novel (1877; English repr. London: Vizetelly, 1884), 10.

-

Andries Bonger, “Catalogue des œuvres de Vincent van Gogh,” 1891, Brieven en Documenten, b 3055 V/1962, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, no. 307, as Vue d’Asnières, avec Marronniers en fleurs.

-

In fact, the painting would not be titled with the name of the restaurant until 1920, when it was exhibited at Vincent van Gogh Exhibition, Montross Gallery, New York, October 23–December 31, 1920, no. 58, and even then, the name “Rispal” was misread as “Cristal.”

-

Relevés Météorologique, Parc de Saint-Maur, May 1887, Paris, Météo-France, cited in Hendriks and Van Tilborgh, Vincent van Gogh Paintings, 2:379.

-

Hendriks and Van Tilborgh, Vincent van Gogh Paintings, 2:387. Hendriks and Van Tilborgh suggest that Restaurant Rispal was painted in the summer rather than the spring. They base their assumption on a letter from Van Gogh to his brother, dated between about Sunday, July 17 and Tuesday, July 19, 1887, where Van Gogh says, “Because remember when I started working at Asnières I had lots of canvases and Tanguy was very good to me.” Jansen, et al., Letters, no. 571, http://vangoghletters.org/en/let571. Hendriks and Van Tilborgh state: “Since we know that he was painting on top of rejected canvases until around the middle of May [editor’s note: two are Square Saint-Pierre, Paris, 1887, Yale University Art Gallery; and Horse Chestnut Tree in Blossom, 1887, Van Gogh Museum]. . . , his first excursions to the village must have taken place after that.” However, the blossoms of the trees in Restaurant Rispal point to a date of May 11 to 25. Indeed, Van Gogh painted the subject on a reused canvas (see the accompanying technical entry by Diana M. Jaskierny). It seems very possible that Van Gogh began the Nelson-Atkins painting on one of those discarded canvases from mid-May that Hendriks and Van Tilborgh reference.

-

See, for example, F313, which he entitled Restaurant de la Sirène à Asnières; F321, Devant le restaurant à Asnières; and F549, Restaurant populaire. F numbers refer to the catalogue raisonné: J.-B. de la Faille, The Works of Vincent van Gogh: His Paintings and Drawings, rev. ed. (Amsterdam: Meulenhoff International, 1970).

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Diana M. Jaskierny, “Vincent van Gogh, Restaurant Rispal at Asnières, 1887,” technical entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.736.2088.

MLA:

Jaskierny, Diana M. “Vincent van Gogh, Restaurant Rispal at Asnières, 1887,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.736.2088.

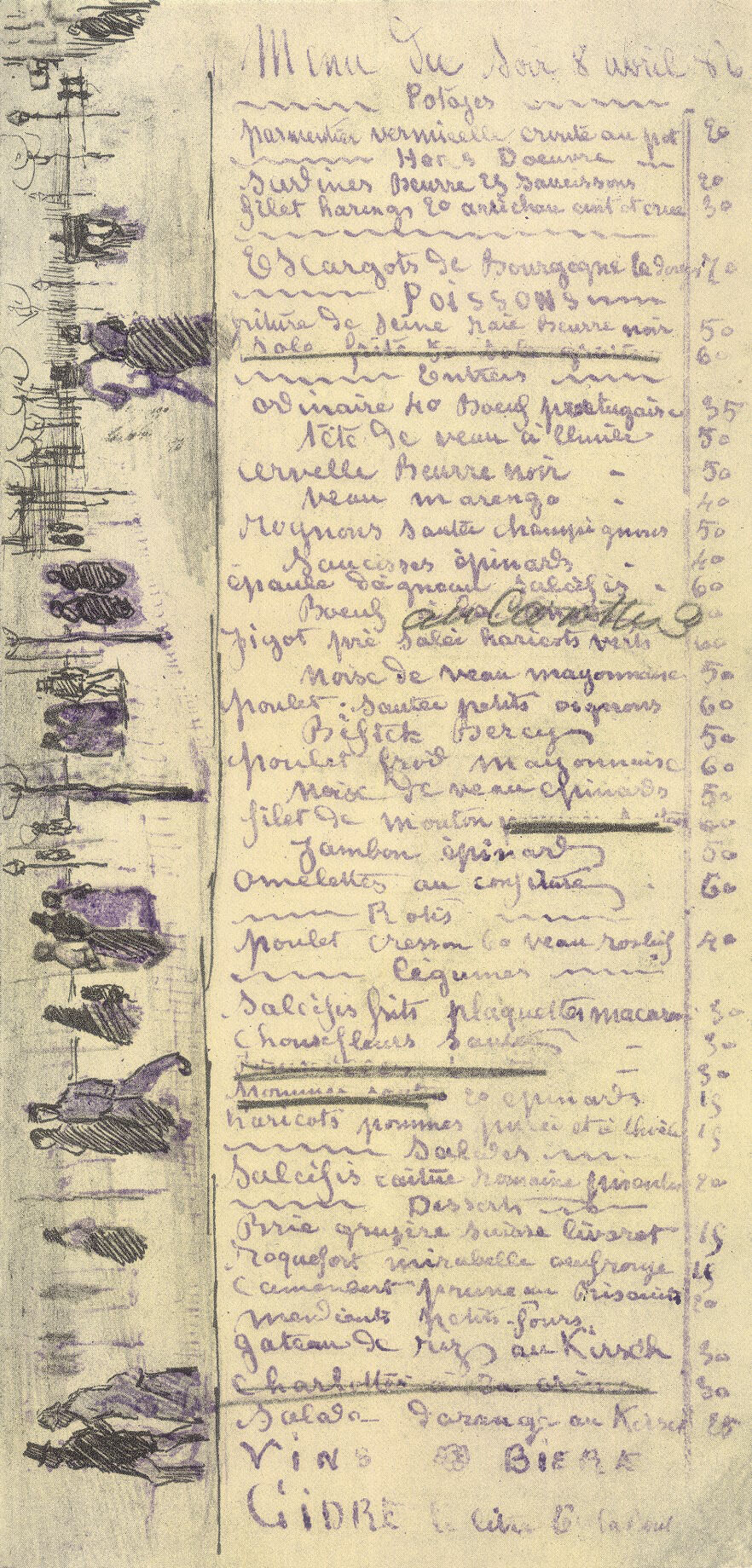

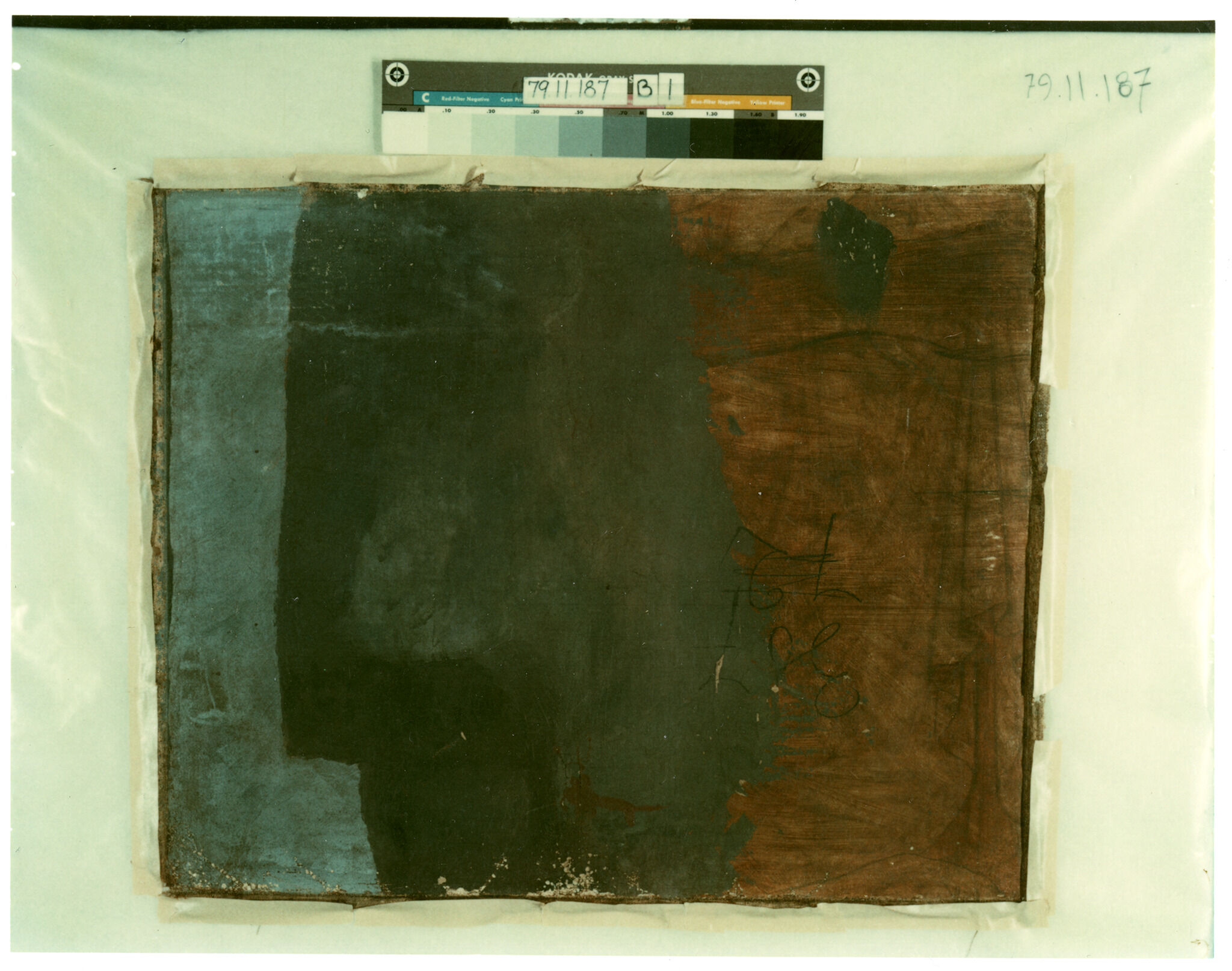

During his brief period in Paris and the surrounding towns, Vincent van Gogh (1853–90) completed Restaurant Rispal at Asnières using vibrant colors, applied with thick impastoimpasto: A thick application of paint, often creating texture such as peaks and ridges. and directional strokes that amplify the perspective of the composition. The painting was executed on a plain-weaveplain weave: A basic textile weave in which one weft thread alternates over and under the warp threads. Often this structure consists of one thread in each direction, but threads can be doubled (basket weave) or tripled to create more complex plain weave. Plain weave is sometimes called tabby weave. canvas, with dimensions corresponding to a standard-formatstandard-format supports: Commercially prepared supports available through art suppliers, which gained popularity in the nineteenth century during the industrialization of art materials. Available in three formats figure (portrait), paysage (landscape), and marine (marine), these were numbered 1 through 120 to indicate their size. For each numbered size, marine and paysage had two options available: a larger format (haute) and smaller (basse) format. no. 20 haute paysage, though rotated 90 degrees. In comparison to other moments in Van Gogh’s career, less is known about his specific supply purchases during his Paris period,1While in Paris, Van Gogh resided with his brother Theo, but when he relocated to the south of France, correspondence between the brothers included discussion of specific canvases and pigments that document many of his materials. Original letters at Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam; published in Leo Jansen, Hans Luijten, and Nienke Bakker, eds., Vincent van Gogh: The Letters, online edition (Amsterdam and The Hague: Van Gogh Museum and Huygens, 2009), http://vangoghletters.org/vg. but he frequented several artist suppliersartist supplier(s): Also called colormen and color merchants. Artist suppliers prepared materials for artists. This tradition dates back to the Medieval period, but the industrialization of the nineteenth century increased their commerce. It was during this time that ready-made paints in tubes, commercially prepared canvases, and standard-format supports were available to artists for sale through these suppliers. It is sometimes possible to identify the supplier from stamps or labels found on the reverse of the artwork. See also canvas stamp, supplier mark, and *color merchant.2During this period, Van Gogh was more concerned with the locations of his suppliers than the quality of materials he purchased. Ella Hendriks, Stéphanie Constantin, and Beatrice Marino, “Various Approaches to Van Gogh Technical Studies: Common Grounds?,” in Reporting Highlights of the De Mayerne Programme, ed. Jaap J. Boon and Ester S.B. Ferreira (The Hague: NOW, 2006), 80. and was given some materials by friends and acquaintances, such as “Père” Tanguy.3Van Gogh’s letter detailing how Tanguy was “very good” to him indicates that canvases were donated to the artist until Tanguy’s wife “objected.” Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, between about Sunday, July 17, and Tuesday, July 19, 1887, published in Jansen et al., Vincent van Gogh: The Letters, no. 571, http://www.vangoghletters.org/en/let571. For more information and lists of the identified suppliers Van Gogh used while in Paris, see Ella Hendriks with scientific analysis by Muriel Geldof, “Van Gogh’s Working Practice: A Technical Study,” in Ella Hendriks and Louis van Tilborgh, Vincent Van Gogh Paintings, vol. 2, Antwerp & Paris 1885–1888, Van Gogh Museum, trans. Michael Hoyle (Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum, 2011), 93-94, 527-530. Complicating matters, it was not uncommon for Van Gogh to reuse canvases for financial reasons while in Paris, specifically in the first half of May and last half of July, 1887.4Hendriks and Van Tilborgh, with Margriet van Eikema Hommes and Monique Hageman, Vincent Van Gogh Paintings, 2:387. Such is the case here, as a photograph of the canvas reverse reveals the beginning of another composition, which includes painted blocks of color and a drawn sketch of drapery (Fig. 6).5The photograph of the original canvas reverse, captured before the 1980 lining, is in the NAMA conservation file, no. 2015.13.10. In most cases, Van Gogh painted directly over his earlier compositions, with few examples in which he reversed the canvas. Hendriks et al., “Van Gogh’s working practice: a technical study,” 112. The paint of this unfinished composition extends to the turnover edgesturnover edge: The point at which the canvas begins to wrap around the stretcher, at the junction between the picture plane and tacking margin. See also foldover edge. but not on the tacking marginstacking margins: The outer edges of canvas that wrap around and are attached to the stretcher or strainer with tacks or staples. See also tacking edge., indicating that the canvas was not resized between uses.6When Van Gogh reused canvases, he often retained the original size. In some instances the canvas was rotated, as it appears to have been here. Ella Hendriks, Luc Megens, and Muriel Geldof, “Van Gogh’s Recycled Works,” in Van Gogh’s Studio Practice, ed. Marije Vellekoop, Muriel Geldof, Ella Hendriks, Leo Jansen, and Alberto de Tagle (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), 310. Additionally, as Restaurant Rispal was painted on the original reverse of the canvas, the street scene covers any possible artist supplier markings. Regardless, the reuse of canvas combined with climate records documenting the arrival of blossoms that season indicates that this painting may have been completed late in May.7Relevés Météorologique, Parc de Saint-Maur, May 1887, Paris, Météo-France, cited in Hendriks and Van Tilborgh, Vincent van Gogh Paintings, 2:379. For a more in-depth discussion, see accompanying catalogue entry by Meghan L. Gray.

Fig. 6. Photograph of original canvas reverse, captured before the 1980 lining, Restaurant Rispal at Asnières (1887)

Fig. 6. Photograph of original canvas reverse, captured before the 1980 lining, Restaurant Rispal at Asnières (1887)

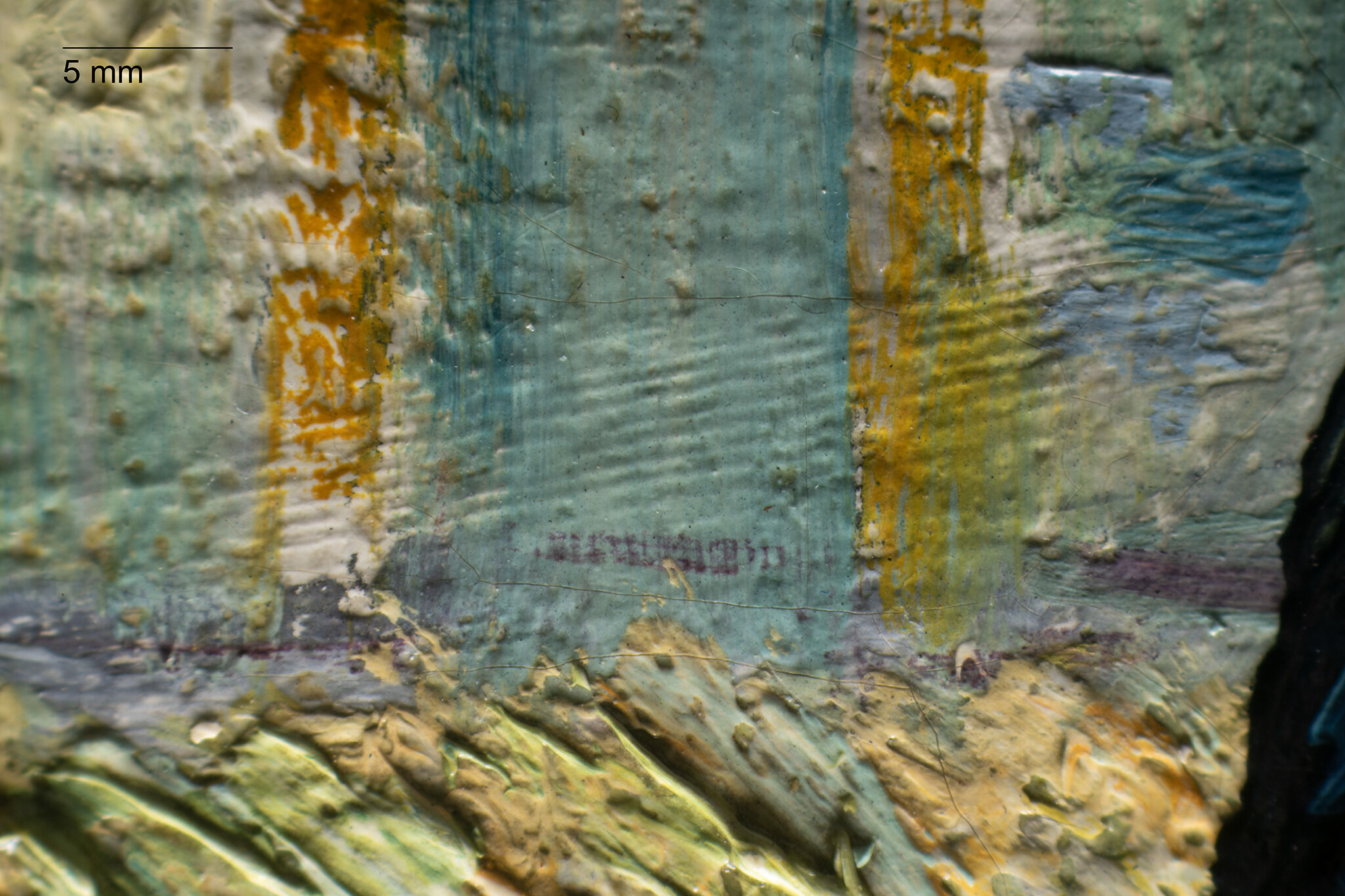

Fig. 7. Photomicrograph in raking light of the serrated ground layer texture, located on the door of the restaurant, Restaurant Rispal at Asnières (1887)

Fig. 7. Photomicrograph in raking light of the serrated ground layer texture, located on the door of the restaurant, Restaurant Rispal at Asnières (1887)

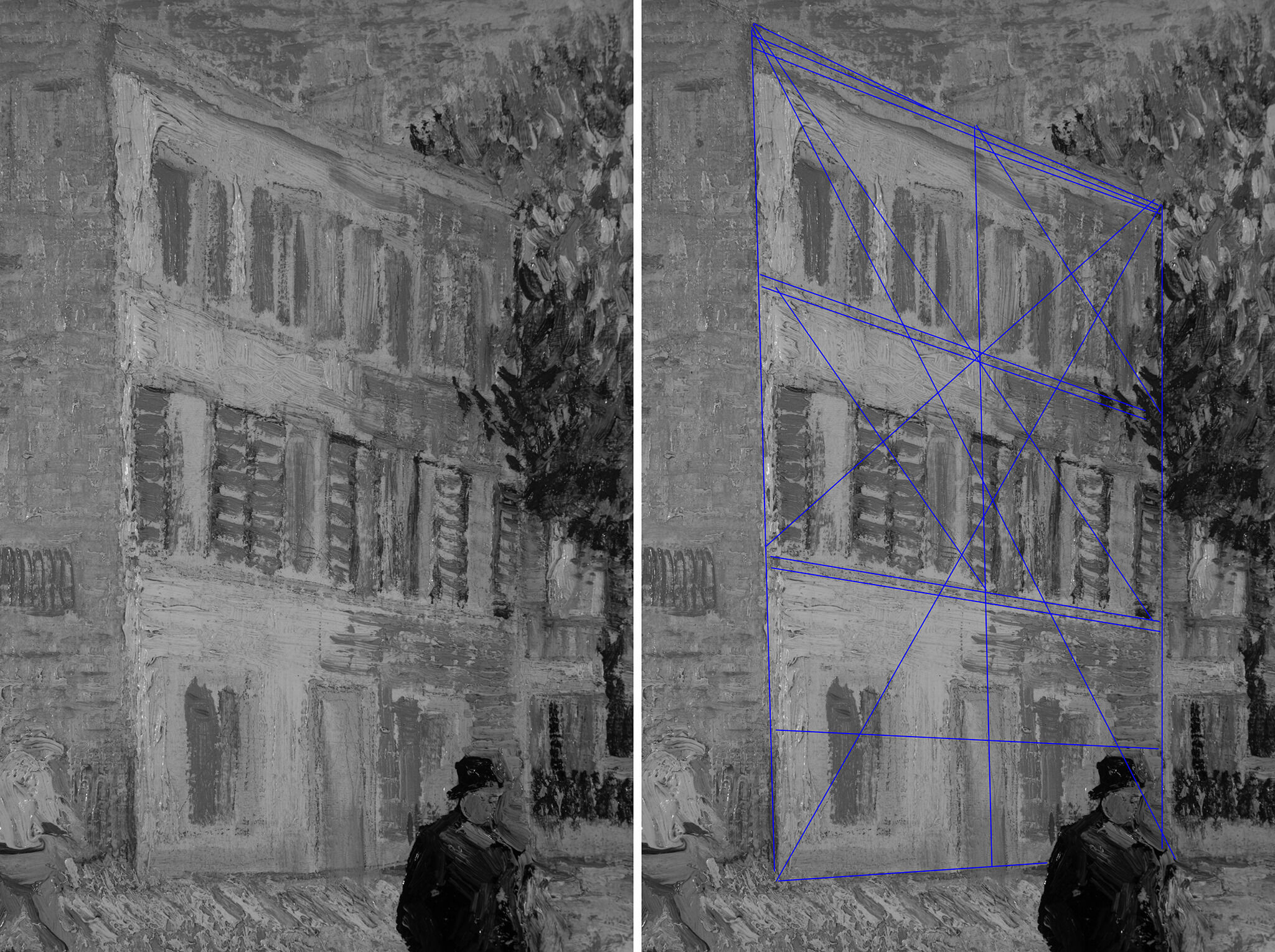

Directly above the ground layer, a carbon-based underdrawingunderdrawing: A drawn or painted sketch beneath the paint layer. The underdrawing can be made from dry materials, such as graphite or charcoal, or wet materials, such as ink or paint. was found through infrared reflectographyinfrared reflectography (IRR): A form of infrared imaging that exploits the behavior of painting materials at wavelengths beyond those accessible to infrared photography. These advantages sometimes include a continuing increase in the transparency of pigments beyond wavelengths accessible to infrared photography (i.e, beyond 1,000 nanometers), rendering underdrawing more clearly. The resulting image is called an infrared reflectogram. Devices that came into common use in the 1980s such as the infrared vidicon effectively revealed these features but suffered from lack of sharpness and uneven response. Vidicons continue to be used out to 2,200 nanometers but several newer pixelated detectors including indium gallium arsenide and indium antimonide array detectors offer improvements. All of these devices are optimally used with filters constraining their response to those parts of the infrared spectrum that reveal the most within the constraints of the palette used for a given painting. They can be used for transmitted light imaging as well as in reflection. and microscope examination. The majority of this underdrawing forms the linear perspectivelinear perspective: A technique in which an artist uses lines to help create the illusion of depth or distance on a two-dimensional picture plane, with objects in the foreground appearing large and objects in the background appearing small. and details of the Restaurant Rispal (windows, doors, and chimneys), with fewer lines marking the more distant structures to the right (Fig. 8). Additional drawn lines exist beneath other passages, unrelated to the linear perspective. Within the cypress trees to the left, upward lines sketch out the branches of the trees and are visible where there are gaps in the paint. Similarly, within the trees to the right there are few drawn lines, mostly forming the basic shapes of the trees and rough placement of the trunks (Fig. 9).

Fig. 8. Reflected infrared digital photograph (left) and detail with blue lines illustrating detected perspective underdrawing lines (right), Restaurant Rispal at Asnières (1887)

Fig. 8. Reflected infrared digital photograph (left) and detail with blue lines illustrating detected perspective underdrawing lines (right), Restaurant Rispal at Asnières (1887)

Fig. 9. Photomicrograph of underdrawing in trees on right side, Restaurant Rispal at Asnières (1887)

Fig. 9. Photomicrograph of underdrawing in trees on right side, Restaurant Rispal at Asnières (1887)

Van Gogh’s Paris period is sometimes referred to as his turning point stylistically. In the winter of 1886 and 1887, the artist began experimenting with various techniques, such as brightly colored peinture à l’essencepeinture à l’essence: De-oiled paint. Peinture à l’essence was produced by the artist by leaching much of the linseed oil out of commercial paints and mixing the resulting thickened paint with turpentine. The resulting paint could be applied as a wash and dried more quickly than unmodified paint. and pointillism, inspired by Toulouse-Lautrec and Seurat and Signac, respectively.12Hendriks, “Developing Technique and Style,” 148-50. In Restaurant Rispal, vibrant colors and short, animated brushstrokes are clearly dominant; however, by this stage, Van Gogh had returned to the use of heavy impastoimpasto: A thick application of paint, often creating texture such as peaks and ridges.. Throughout the painting, Van Gogh used this impasto to vary the textures of each compositional element, enhanced when viewing the painting in raking lightraking light: An examination technique in which light is placed at a shallow angle from one direction to reveal the surface topography. (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11. Raking light digital photograph, Restaurant Rispal at Asnières (1887)

Fig. 11. Raking light digital photograph, Restaurant Rispal at Asnières (1887)

Fig. 12. Detail image of hatching on the restaurant, Restaurant Rispal at Asnières (1887)

Fig. 12. Detail image of hatching on the restaurant, Restaurant Rispal at Asnières (1887)

The painting is in excellent condition. In 1980 a full conservation

treatment was completed, including a wax lininglining: A procedure used to reinforce a weakened canvas that involves adhering a second fabric support using adhesive, most often a glue-paste mixture, wax, or synthetic adhesive.14Due to this lining, the reverse of the canvas is no longer accessible. and the addition of

a glossy synthetic varnish, now slightly discolored. The painting has

few losses and minimal retouchingretouching: Paint application by a conservator or restorer to cover losses and unify the original composition. Retouching is an aspect of conservation treatment that is aesthetic in nature and that differs from more limited procedures undertaken solely to stabilize original material. Sometimes referred to as inpainting or retouch..15Forrest R. Bailey, January 19, 1980, treatment report, NAMA conservation file, no. 2015.13.10.

Fig. 15. Photomicrograph of trunk illustrating outline under orange highlight, Restaurant Rispal at Asnières (1887)

Fig. 15. Photomicrograph of trunk illustrating outline under orange highlight, Restaurant Rispal at Asnières (1887)

Fig. 16. Detail of the central figure with pentimento around profile, Restaurant Rispal at Asnières (1887)

Fig. 16. Detail of the central figure with pentimento around profile, Restaurant Rispal at Asnières (1887)

Notes

-

While in Paris, Van Gogh resided with his brother Theo, but when he relocated to the south of France, correspondence between the brothers included discussion of specific canvases and pigments that document many of his materials. Original letters at Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam; published in Leo Jansen, Hans Luijten, and Nienke Bakker, eds., Vincent van Gogh: The Letters, online edition (Amsterdam and The Hague: Van Gogh Museum and Huygens, 2009), http://vangoghletters.org/vg.

-

During this period, Van Gogh was more concerned with the locations of his suppliers than the quality of materials he purchased. Ella Hendriks, Stéphanie Constantin, and Beatrice Marino, “Various Approaches to Van Gogh Technical Studies: Common Grounds?,” in Reporting Highlights of the De Mayerne Programme, ed. Jaap J. Boon and Ester S.B. Ferreira (The Hague: NOW, 2006), 80.

-

Van Gogh’s letter detailing how Tanguy was “very good” to him indicates that canvases were donated to the artist until Tanguy’s wife “objected.” Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, between about Sunday, July 17, and Tuesday, July 19, 1887, published in Jansen et al., Vincent van Gogh: The Letters, no. 571, http://www.vangoghletters.org/en/let571. For more information and lists of the identified suppliers Van Gogh used while in Paris, see Ella Hendriks, with scientific analysis by Muriel Geldof, “Van Gogh’s Working Practice: A Technical Study,” in Ella Hendriks and Louis van Tilborgh, Vincent Van Gogh Paintings, vol. 2, Antwerp and Paris 1885–1888, Van Gogh Museum, trans. Michael Hoyle (Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum, 2011), 93–4, 527–530.

-

Hendriks and Van Tilborgh, with Margriet van Eikema Hommes and Monique Hageman, Vincent Van Gogh Paintings, 2:387.

-

The photograph of the original canvas reverse, captured before the 1980

lining, is in the NAMA conservation file, no. 2015.13.10. In most cases, Van Gogh painted directly over his earlier compositions, with few examples in which he reversed the canvas. Hendriks et al., “Van Gogh’s working practice: a technical study,” 112. -

When Van Gogh reused canvases, he often retained the original size. In some instances the canvas was rotated, as it appears to have been here. Ella Hendriks, Luc Megens, and Muriel Geldof, “Van Gogh’s Recycled Works,” in Van Gogh’s Studio Practice, ed. Marije Vellekoop, Muriel Geldof, Ella Hendriks, Leo Jansen, and Alberto de Tagle (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), 310.

-

Relevés Météorologique, Parc de Saint-Maur, May 1887, Paris, Météo-France, cited in Hendriks and Van Tilborgh, Vincent van Gogh Paintings, 2:379. For a more in-depth discussion, see accompanying catalogue entry by Meghan L. Gray.

-

If the unfinished composition was the work of Van Gogh, it is likely that this side of the canvas was commercially prepared, as this was the artist’s preference in materials.

-

Soon after his time in Ansières, Van Gogh began experimenting with texture, specifically twill weave canvases. It is possible that the serrated marks on Restaurant Rispal at Ansières were an early experimentation with texture. Ella Hendriks, “Developing Technique and Style,” in Hendriks and Van Tilborgh, Vincent Van Gogh Paintings, 2:154–55.

-

Devi Ormond, Teio Meedendorp, Muriel Geldof, Luc Megens, and Kathrin Pilz, “Interpreting Van Gogh’s Plein Air Painting Practice: Written Sources Versus Painted Image,” in The Artist’s Process: Technology and Interpretation, ed. Sigrid Eyb-Green, Joyce H. Townsend, Mark Clarke, Jilleen Nadolny, and Stefanos Kroustallis (London: Archetype Publications, 2012), 177.

-

Oiled vine charcoal has stronger binding properties than compressed charcoal, allowing for its possible preservation through restoration or conservation campaigns. Paul Goldman, Looking at Prints, Drawings and Watercolours: A Guide to Technical Terms (London: British Museum Press, 2006), 20.

-

Hendriks, “Developing Technique and Style,” 148–50.

-

While the reds in the trees appear to be red lake, it is unclear if any fading has occurred, as has been seen in other Van Gogh paintings. No elemental analysis or sampling was conducted for this examination. For more information on fading red lake, see Mary Schafer and John Twilley, “Vincent van Gogh, Olive Trees, June/September 1889,” technical entry in Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, ed., French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.738.2088.

-

Due to this lining, the reverse of the canvas is no longer accessible.

-

Forrest R. Bailey, January 19, 1980, treatment report, NAMA conservation file, no. 2015.13.10.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Meghan L. Gray, “Vincent van Gogh, Restaurant Rispal at Asnières, 1887,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.736.4033.

MLA:

Gray, Meghan L. “Vincent van Gogh, Restaurant Rispal at Asnières, 1887,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.736.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Meghan L. Gray, “Vincent van Gogh, Restaurant Rispal at Asnières, 1887,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.736.4033.

MLA:

Gray, Meghan L. “Vincent van Gogh, Restaurant Rispal at Asnières, 1887,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.736.4033.

With the artist, Paris, 1887;

To his brother, Theo van Gogh (1857–91), Paris, 1887–January 25, 1891;

Inherited by his widow, Johanna van Gogh-Bonger (1862–1925), Bussum and Amsterdam, The Netherlands, stock no. 307, as Vue d’Asnières, avec Marronniers en fleurs, by 1891 [1];

By descent to her son, Vincent Willem van Gogh (1890–1978), Laren, The Netherlands, by 1925–27;

Purchased from Vincent Willem van Gogh through Leicester Galleries, London, by Nathan Charles Beechman (ca. 1861–1935), London, February 9, 1927–at least 1928 [2];

With Alex Reid and Lefèvre Ltd., London, stock no. 146/29, as Restaurant Rispal à Asnières, on joint account with C. W. Kraushaar Art Galleries, New York, stock no. 24707, and on joint account with Bignou Gallery, New York, stock no. 1596, as Le Restaurant Rispal à Asnières, by July 19, 1929–January 30, 1930 [3];

Purchased from Alex Reid and Lefèvre by Gérard Frères, Paris, January 30, 1930 [4];

With Galerie Georges Bernheim, Paris;

With Hugo L. Moser (1881–1972), Berlin, Zurich, Heemstede, The Netherlands, and New York, by December 1930–until at least 1970 [5];

Transferred to his wife, Mrs. Hugo L. Moser (née Maria Werner, 1893–1987), New York, by the late 1960s–November 7, 1979 [6];

Purchased from the Moser Family Collection sale, Impressionist and Modern Paintings and Sculpture, Sotheby Parke Bernet Inc., New York, November 7, 1979, no. 541, as Le Restaurant Rispal à Asnières, through Richard L. Feigen and Co., New York, stock no. 16435-C, by Marion (née Helzberg, 1931–2013) and Henry W. (1922–2019) Bloch, Shawnee Mission, KS, 1979–June 11, 2015 [7];

Their gift to the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 2015.

Notes

[1] Although, formally speaking, Vincent Willem van Gogh (1890–1978) was joint

owner of the Van Gogh collection from 1891, his mother, Johanna van

Gogh-Bonger, managed the collection until her death in 1925. See the

inventory of van Gogh’s works then in van Gogh-Bonger’s collection:

Andries Bonger, “Catalogue des œuvres de Vincent van Gogh,” 1891,

Brieven en Documenten, b 3055 V/1962 (document), Van Gogh Museum,

Amsterdam, no. 307, as Vue d’Asnières, avec Marronniers en fleurs. See

also photograph of the verso of the painting before its relining in

1980, with the inscription reading, 307/72; copy in NAMA curatorial

files.

[2] The date February 9, 1927 is from Walter Feilchenfeldt, Vincent van Gogh: The Years in France; Complete Paintings 1886–1890: Dealers, Collectors, Exhibitions, Provenance (London: Philip Wilson, 2013), 84. Feilchenfeldt, 30, 33n53, notes that V. W. van Gogh sold the painting through Leicester Galleries on the occasion of the second exhibition at Leicester Galleries in November–December 1926. It is possible that the sale to the next constituent was not finalized until February, well after the exhibition closed. The catalogue raisonné (J.-B. De La Faille, L’Œuvre de Vincent Van Gogh: Catalogue Raisonné [Paris: éditions G. Van Oest, 1928), no. 355]) has the painting in Beechman’s collection in 1928.

[3] See letter from Alex Reid and Lefèvre to Kraushaar, July 19, 1929, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, Kraushaar Galleries Records, 1885–2006, Series II, Incoming Letters, Re General, 1929, box 14, folder 23. See Alex Reid and Lefèvre stock book entry, Tate Britain, London, Alex Reid and Lefèvre archives, TGA 200211, p. 290. See also email from Alexander Corcoran, Lefevre Fine Art, to MacKenzie Mallon, NAMA, March 18, 2019, NAMA curatorial file. See also Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, Kraushaar Galleries Records, 1885–2006, Series 6.4, Financial Records, 1885–1957, Purchase Journal, 1928–1940, Box 74, Folder 7, page 63. See also Musée d’Orsay, Paris, Bignou archive, Albums BIGNOU ODO 1996-29, N°24, Boîte 31, Van Gogh, Clichés 294–295; and The Frick Collection/Frick Art Reference Library Archives, New York, Bignou Gallery Albums, MS.024, Album 24: Post-Impressionnistes. The Bignou Gallery albums at the Frick contain photographs and descriptions of artwork that passed through the hands of the Bignou Gallery (New York) during the 1930s and 1940s, but it is also possible that Bignou only provided a new frame for the painting rather than owning a half share. See letters cited above. Also according to Reid and Lefèvre’s stock book entry, they owed an “additional cost” to Bignou. For the relationship between Bignou and Reid and Lefèvre, see Alex Reid and Lefevre 1926–1976 (London: Lefèvre Gallery, 1976), 17–21.

[4] See record of sale to Gérard in Alex Reid and Lefèvre stock book, Tate Britain, London, Alex Reid and Lefèvre archives, TGA 200211, p. 290. Although the stock book lists “Raphaël Gérard” as the purchaser, the dealer did not establish “Galerie Raphaël Gérard” until 1932. Before that, Raphaël and his brother, Christian Alfred Valère Gérard, ran “Gérard Frères” in Paris (1911–1932). See “Bio and History,” in “Galerie Félix Gérard and Galerie Raphaël Gérard Records, ca. 1899–1959,” Wildenstein Plattner Institute, New York and Paris, https://digitalprojects.wpi.art/archive/detail/453312-galerie-felix-gerard-and-galerie-raphael-gerard-re.

[5] Possibly Moser stock no. L.64.23.2. Moser was an art dealer in Berlin until 1933, when he and his family fled the Nazis, first living in Zurich and then in Heemstede, The Netherlands. In February 1940, just before the Nazis’ invasion of The Netherlands, they crossed through France, Italy, Spain, and Cuba before finally arriving in New York. Prior to their flight from Europe, they sent their art collection from The Netherlands to the Baltimore Museum of Art, which arrived at the museum on May 1, 1939. The present painting appears on the wall of the Moser apartment in New York City in a photograph published in Aftonbladet on January 24, 1953. Letter from Ann Moser, Hugo L. Moser’s daughter-in-law, to Meghan Gray, April 21, 2015, NAMA curatorial files.

[6] The painting was sent on long-term loan to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, from February 16, 1968 until April 28, 1976, and then was transferred to the Baltimore Museum of Art. It remained on loan in Baltimore until it was transported to Sotheby’s on September 14, 1979, where it was sold by Maria Moser on November 7, 1979. All of Hugo L. Moser’s paintings were transferred to his wife, Maria Moser, in the late 1960’s when his health was failing. See emails from Ann Moser to Meghan Gray, April 21, 2015 and May 6, 2015. See also email from Mary Allen, Assistant Registrar, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, April 22, 2015, and email from Caitlin Draayer, Assistant Registrar, Baltimore Museum of Arts, April 22, 2015, to Meghan Gray, NAMA curatorial files.

[7] While Maria Moser was the primary owner of the painting, she gave a portion of each painting in the collection to her two sons, daughters-in-law, and grandchildren each year. By 1979, the present painting was collectively owned by the Moser family. Email from Ann Moser to Meghan Gray, April 30, 2015, NAMA curatorial files.

Richard L. Feigen and Co. was purchaser as agent for the Blochs. See email from Ann Moser to Meghan Gray, April 30, 2015, NAMA curatorial files. Richard L. Feigen and Co. purchased the painting at Sotheby’s on behalf of Henry and Marion Bloch. See email from Emelia Scheidt, Richard L. Feigen and Co., New York, to Meghan Gray, April 13, 2015, NAMA curatorial files.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Meghan L. Gray, “Vincent van Gogh, Restaurant Rispal at Asnières, 1887,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.736.4033.

MLA:

Gray, Meghan L. “Vincent van Gogh, Restaurant Rispal at Asnières, 1887,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.736.4033.

Vincent van Gogh, Exterior of a Restaurant in Asnières, May–June 1887, oil on canvas, 7 7/16 x 10 5/8 in. (18.8 x 27.0 cm), Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.

Vincent van Gogh, The Restaurant de la Sirène at Asnières, June–September 1887, pencil and chalk on paper, 15 11/16 x 21 1/4 in. (39.8 x 53.8 cm), Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.

Vincent van Gogh, The Restaurant de la Sirène at Asnières, summer 1887, oil on canvas, 21 1/2 x 25 13/16 in. (54.5 x 65.5 cm), Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Meghan L. Gray, “Vincent van Gogh, Restaurant Rispal at Asnières, 1887,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.736.4033.

MLA:

Gray, Meghan L. “Vincent van Gogh, Restaurant Rispal at Asnières, 1887,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.736.4033.

Possibly exhibition [organized by Vincent van Gogh], Grand Bouillon-Restaurant du Chalet, Paris, November 1887, no cat.

Possibly paintings by Vincent van Gogh, Theo van Gogh’s apartment, 8, Cité Pigalle, Paris, end of 1890, no cat.

Tentoonstelling van Schilderijen en Teekeningen door Vincent van Gogh, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, July–August 1905, no. 78, as Gezicht op Asnières met bloeiende kastanjes.

XI. Jahrgang: IX. Ausstellung, Werke von Paula Modersohn[-Becker], Regina Mundlak, Vincent van Gogh, Galerie Paul Cassirer, Berlin, May 1909, no cat., as Blühende Kastanien in Asnières.

Vincent van Gogh, Kunsthaus Brakl, Munich, October 7–December 1909, no. 13 [ or 9 or 11], as Asnières.

Vincent van Gogh, Frankfurter Kunstverein, Frankfurt, January 1910; Galerie Ernst Arnold, Dresden, February 1910; Kunstausstellung Gerstenberger, Chemnitz, Germany, April 1910, no cat.

Tentoonstelling Vincent van Gogh, Larensche Kunsthandel, Amsterdam, June 1911, no. 27, as Avenue te Asnières met bloeiende kastanjes.

Galerie Commeter, Hamburg, November 1911, no cat., no. 8/78, as Asnières met figuur.

Ausstellung Vincent van Gogh, 1853–1890, Galerie Ernst Arnold, Breslau [Wrocław], Poland, and Dresden, February 1912, no. 23, as Asmeres [sic].

Vincent van Gogh Exhibition, Montross Gallery, New York, October 23–December 31, 1920, no. 58, erroneously as Restaurant Cristal, Paris.

Possibly Vincent van Gogh Exhibition, Montross Gallery, New York, February 8–28, 1921.

Probably Vincent van Gogh Exhibition, Montross Gallery, New York, 1923, no cat., erroneously as Restaurant Cristal, Paris.

Vincent van Gogh, Kunsthalle Basel, March 27–April 21, 1924, no. 18, erroneously as Restaurant Cristal, Paris.

Vincent van Gogh, Kunsthaus Zürich, July 3–August 10, 1924, no. 18, as Restaurant Rispal, Asnières.

Austellung Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890), Württembergische Kunstverein, Kunstgebäude, Stuttgart, October–November 1924, no. 6, as Garten in Asnières.

Exposition Rétrospective d’Œuvres de Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890), Galerie Marcel Bernheim, Paris, January 5–24, 1925, no. 15, as Le Restaurant Rispal.

Vincent van Gogh, Pulchri Studio, The Hague, March–April 1925, no cat., no. 20, erroneously as Restaurant Cristal.

I. Allgemeine Kunst-Ausstellung: Künstler-genossenschaft, Secession, Neue Secession, Glaspalast, Munich, June 1–early October 1926, no. 2067, erroneously as Restaurant Cristal.

An Exhibition of Works by Vincent Van Gogh, Leicester Gallery, London, November–December 1926, no. 13, as Restaurant Rispal.

An Exhibition of Pictures by Modern French Masters, Arthur Tooth and Sons, London, April 2–May 3, 1930, no. 18, as Le Restaurant Rispal à Asnières.

The Art and Life of Vincent van Gogh: Loan Exhibition in Aid of American and Dutch War Relief, Wildenstein, New York, October 6–November 7, 1943, no. 19, as The Restaurant Rispal.

Work by Vincent Van Gogh, Cleveland Museum of Art, November 3–December 12, 1948, no. 6, as The Restaurant Rispal (Restaurant Rispal, à Asnières).

Van Gogh: Loan Exhibition for the Benefit of the Public Education Association, Wildenstein and Co., New York, March 24–April 30, 1955, no. 26, as The Restaurant Rispal.

Van Gogh and Expressionism, The Soloman R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, July–September 1964, unnumbered, as The Restaurant Rispal.

The Bloch Collection, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, June–August 1982, no cat.

Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, June 9–September 9, 2007, no. 21, as Restaurant Rispal.

Van Gogh à Paris, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, February 2–May 15, 1988, no. 45, as Le Restaurant Rispal à Asnières.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Meghan L. Gray, “Vincent van Gogh, Restaurant Rispal at Asnières, 1887,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.736.4033.

MLA:

Gray, Meghan L. “Vincent van Gogh, Restaurant Rispal at Asnières, 1887,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.736.4033.

Catalogus der Tentoonstelling van Schilderijen en Teekeningen door Vincent van Gogh, exh. cat. (Amsterdam: Stedelijk Museum, 1905), 22, as Gezicht op Asnières met bloeiende kastanjes.

R-th. [Alwin Rath], “Die Mai-Ausstellung bei Paul Cassirer,” Berliner Volks-Zeitung 57, no. 215 (May 9, 1909): 3 [repr. in Bernhard Echte and Walter Feilchenfeldt, eds., Kunstsalon Paul Cassirer, vol. 4, Die Ausstellungen 1908–1910: “Ganz eigenartige neue Werte” (Wädenswil: Nimbus, Junst und Bücher AG, 2013), 213], as blühenden Kastanien zu Aßniereß [sic].

Ausstellung Vincent van Gogh, 1853–1890, exh. cat. (Dresden: Galerie Ernst Arnold, 1912), 13, as Asmeres [sic].

Vincent van Gogh Exhibition, exh. cat. (New York: Montross Gallery, 1920), unpaginated, (repro.), erroneously as Restaurant Cristal, Paris.

“Exhibitions Now On: Vincent Van Gogh at Montross’s,” American Art News 19, no. 2 (October 23, 1920): 2, as Paris Restaurant.

Royal Corissoz, “Vincent Van Gogh Seen At His Best and His Worst,” New York Tribune 80, no. 27,020 (November 7, 1920): 7, erroneously as Restaurant Cristal.

Vincent van Gogh, exh. cat. (Basel: Kunsthalle Basel, 1924), 7, erroneously as Restaurant Cristal, Paris.

Vincent van Gogh, exh. cat. (Zürich: Buchdruckerei Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 1924), 15, as Restaurant Rispal, Asnières. Listed as for sale.

Vincent van Gogh, exh. cat. (Stuttgart: Württembergische Kunstverein, 1924), no. 6.

Exposition Rétrospective d’Œuvres de Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890), exh. cat. (Paris: Galerie Marcel Bernheim, 1925), unpaginated, as Le Restaurant Rispal.

Vincent van Gogh, exh. cat. (The Hague: Pulchri Studio, March–April 1925), no. 20.

I. Allgemeine Kunst-Ausstellung: Künstler-genossenschaft, Secession, Neue Secession, exh. cat. (Munich: Knorr und Hirth, G. m. b. H., 1926), 77, erroneously as Restaurant Cristal.

Catalogue of an Exhibition of Works by Vincent Van Gogh, exh. cat. (London: Ernest Brown and Phillips, 1926), 12, as Restaurant Rispal.

J[acob]-B[aart] De La Faille, L’Œuvre de Vincent Van Gogh: Catalogue Raisonné (Paris: Éditions G. Van Oest, 1928), no. 355, pp. 1: 100, 2pt1: pl. XCV, (repro.), as Restaurant Rispal, à Asnières.

Catalogue of an Exhibition of Pictures by Modern French Masters, exh. cat. (London: Arthur Tooth and Sons Galleries, 1930), 5, 7, (repro.), as Le Restaurant Rispal à Asnières.

Almanach für das jahr 1931, special issue, Omnibus: eine zeitschrift (December 1930): 83, (repro.), as Caf’e Raspail [sic] in Asnières.

J[acob]-B[aart] de la Faille, Vincent van Gogh, trans. Prudence Montagu-Pollock (New York: French and European Publications, 1939), 284, (repro.), as The “Restautant Rispal” at Asnières.

Georges de Batz, The Art and Life of Vincent Van Gogh: Loan Exhibition in Aid of American and Dutch War Relief (New York: Wildenstein, 1943), 23, 61, (repro.), as The Restaurant Rispal.

Work by Vincent van Gogh, exh. cat. (Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art, 1948), 12, 16, (repro.), as The Restaurant Rispal (Restaurant Rispal, à Asnières).

“Van Gogh Revisited: Fifty of His Paintings Are Assembled in Cleveland,” Pictures on Exhibit 11, no 2 (November 1948):10–11, (repro.), as Restaurant Rispal.

Einar Thulin, “Garbo fick ej köpa Renoir: AB på New York-besök hoз mannen bakom Kärlekslektionen,” Aftonbladet 124, no. 22 (January 24, 1953): 3, (repro.).

Van Gogh: Loan Exhibition for the Benefit of the Public Education Association, exh. cat. (New York: Wildenstein, 1955), 21, 41 (repro.), as The Restaurant Rispal.

Possibly Jean-Louis Gauthier, Vincent Van Gogh: peintre de la lumière (Lyon, France: Éditions et imprimeries du Sud-Est, 1957), 47, as Restaurant à Asnières.

Maurice Tuchman, Van Gogh and Expressionism, exh. cat. (New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 1964), unpaginated, as The Restaurant Rispal.

Henri Perruchot, Het Leven van Vincent Van Gogh (Utrecht, The Netherlands: Prisma-Boeken, 1965), 192.

Paolo Lecaldano, L’opera pittorica completa di Van Gogh e i suoi nessi grafici, new series, vol. 1 (1966, 1971; repr., Milan: Rizzoli Editore, 1977), no. 395, pp. 116–17, (repro.), as Il Ristorante ‘Rispal’ (ad Asnières).

Marc-Edo Tralbaut, “Comment identifier Van Gogh?” Bulletin des Archives internationales de van Gogh, no. 1 (1967): 34, as Restaurant Rispal.

Jean Leymarie, Who Was Van Gogh?, trans. James Emmons (Geneva: Editions d’Art Albert Skira, 1968), 81.

J[acob]-B[aart] de la Faille, The Works of Vincent van Gogh: His Paintings and Drawings, rev. ed. (Amsterdam: Meulenhoff International, 1970), no. F355 [H391], pp. 166–67, 625, 680, 688, (repro.), as Restaurant Rispal at Asnières.

Bogomila Welsh-Ovcharov, Vincent Van Gogh: His Paris Period, 1886–1888 (Utrecht: Editions Victorine, 1976), 234, as Restaurant Rispal at Asnières.

Jan Hulsker, Van Gogh en zijn weg: Al zijn tekeningen en schilderijen in hun samenhang en ontwikkeling (Amsterdam: Meulenhoff International bv, 1977), no. 1266, pp. 278, 282–83, (repro.), as Restaurant Rispal in Asnières.

Impressionist and Modern Paintings and Sculpture (New York: Sotheby Parke Bernet, November 7, 1979), unpaginated, (repro.), as Le Restaurant Rispal à Asnières.

“Impressionist-Modern Sales: ‘Staggering’ Prices, Mixed Quality,” Art Newsletter 5, no. 7 (November 27, 1979): 2, as le restaurant Rispal à Asnières.

Paul Aletrino, Tout Van Gogh, 1888–1890, trans. Sylvie Desmaison (Paris: Flammarion, 1980), 74, 80, (repro.), as Le restaurant Rispal, à Asnières.

Jan Hulsker, The Complete Van Gogh: Paintings, Drawings, Sketches (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1980), no. 1266, pp. 278, 282–83, (repro.), as Restaurant Rispal in Asnières.

Bogomila Welsh-Ovcharov, Vincent van Gogh and the Birth of Cloisonnism, exh. cat. (Toronto: Art Gallery of Ontario, 1981), 104, as Rispal.

“The Bloch Collection,” Gallery Events (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) (June–August 1982): unpaginated.

Françoise Cachin and Bogomila Welsh-Ovcharov, ed., Van Gogh à Paris, exh. cat. (Paris: Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 1988), 120, 128–29, (repro.), as Le Restaurant Rispal à Asnières.

Walter Feilchenfeldt, Vincent van Gogh and Paul Cassirer, Berlin: The Reception of Van Gogh in Germany from 1901 to 1914 (Zwolle, The Netherlands: Uitgeverij Waanders, 1988), 30, 89–90, 140, 147–48, as Restaurant Rispal at Asnières.

Jan Hulsker, Van Gogh en zijn weg: Het complete werk, 6th ed., rev. and expanded (Amsterdam: Meulenhoff Nederland bv, 1989), no. 1266, pp. 278, 282–83, (repro.), as Restaurant Rispal in Asnières.

Hans Bronkhorst, Vincent Van Gogh, trans. Tony Langham and Plym Peters (New York: Portland House, 1990), 42–44, (repro.), as Restaurant Rispal at Asnières.

Giovanni Testori and Luisa Arrigoni, Van Gogh: catalogo completo dei dipinti (Firenze: Cantini, 1990), 178, 187, (repro.), as Il Ristorante “Rispal” ad Asnières.

Ingo F. Walther and Rainer Metzger, Vincent van Gogh: The Complete Paintings, part 1 (1990; repr., Cologne: Taschen GmbH, 2012), 240, (repro.), as The Rispal Restaurant at Asnières.

Peter H. Feist, Impressionism in France, vol. 1, Impressionist Art, 1860–1920, ed. Ingo F. Walther (Cologne: Benedikt Taschen, 1993), 282, (repro.), as Restaurant Rispal at Asnières.

Jan Hulsker, Vincent Van Gogh: A Guide to His Work and Letters (Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum, 1993), 75.

Matthias Arnold, Vincent van Gogh: Werk und Wirkung (Munich: Kindler, 1995), 820n103.

Jan Hulsker, The New Complete Van Gogh: Paintings, Drawings, Sketches; Revised and Enlarged Edition of the Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of Vincent Van Gogh, rev. ed. (Amsterdam: J. M. Meulenhoff b.v., 1996), no. 1266, pp. 278, 282–83, (repro.), as Restaurant Rispal at Asnières.

Ronald Pickvance, Van Gogh, exh. cat. (Martigny, Switzerland: Fondation Pierre Gianadda, 2000), 295.

Marina Ferretti-Bocquillon et al., Signac, 1863–1935, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2001), 131, as Restaurant Rispal, Asnières.

Possibly Madeleine Korn, “Collecting Modern Foreign Art in Britain before World War Two” (Ph.D. diss., University of Reading, 2001), 136.

Pierre Leprohon, Vincent Van Gogh (Saint-Ouen-l’Aumone, France: Éditions du Valhermeil, 2001), 353, as Restaurant Rispal.

Madeleine Korn, “Collecting Paintings by Van Gogh in Britain before the Second World War,” Van Gogh Museum Journal (2002): 136, as Restaurant Rispal at Asnières.

D. M. Field, Van Gogh (Edison, NJ: Chartwell Books, 2005), 147, 150, (repro.), as The Restaurant Rispal at Asnières.

Rebecca Dimling Cochran and Bobbie Leigh, “100 Top Collectors Who Have Made a Difference,” Art and Antiques 29, no. 3 (March 2006): 90, as Restaurant Rispal at Asnières.

Bobbie Leigh, “Magnificent Obsession,” Art and Antiques 28, no. 6 (June 2006): 61–62, 65, (repro.), as Le Restaurant Rispal at Asnières.

“Inaugural Exhibitions Celebrate Kansas City,” Member Magazine (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (Fall 2006): 3.

Martin Bailey, Van Gogh and Britain: Pioneer Collectors (Edinburgh: National Galleries of Scotland, 2006), 120, as Restaurant Rispal at Asnières.

Judit Geskó, ed., Van Gogh in Budapest, exh. cat. (Budapest: Museum of Fine Arts, 2006), 540n1.

Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 11–12, 15–16, 112–15, 160, (repro.), as Restaurant Rispal at Asnières (Le restaurant Rispal à Asnières).

Alice Thorson, “First Public Exhibition: Marion and Henry Bloch’s art collection,” Kansas City Star (June 3, 2007): E4, as Restaurant Rispal at Asnières.

Steve Paul, “Pretty Pictures: Marion and Henry Bloch’s collection of superb Impressionist masters,” Panache 4, no. 3 (Fall 2007): 20, 24, (repro.), as Restaurant Rispal at Asnières.

“Lasting Impressions: A Tribute to Marion and Henry Bloch,” Member Magazine (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (Fall 2007): 11.

Walter Feilchenfeldt, Vincent van Gogh: Die Gemälde 1886–1890; Händler, Sammler, Ausstellungen, Frühe Provenienzen (Wädenswil, Switzerland: Nimbus, Kunst und Bücher, 2009), 31n53, 82, 292, 307, 321–22, 328, (repro.), as Restaurant Crystal and Restaurant Rispal in Asnières.

“Kansas City Riches,” New York Times 159, no. 54,942 (February 5, 2010): C26.

Thomas M. Bloch, Many Happy Returns: The Story of Henry Bloch, America’s Tax Man (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, 2011), 174, as Restaurant Rispal at Asnières.

Ella Hendriks and Louis van Tilborgh, Vincent van Gogh Paintings, vol. 2, Antwerp and Paris 1885–1888, Van Gogh Museum, trans. Michael Hoyle (Amsterdam: van Gogh Museum, 2011), 387, 575.

Possibly Kenneth L. Vaux, ed., The Ministry of Vincent Van Gogh in Religion and Art (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2012), 107.

Bernhard Echte and Walter Feilchenfeldt, eds., Kunstsalon Paul Cassirer, vol. 4, Die Ausstellungen 1908–1910: “Ganz eigenartige neue Werte” (Wädenswil: Nimbus, Kunst und Bücher AG, 2013), 213, 222, 485, (repro.), as Restaurant Rispal in Asnières (Blühende Kastanien in Asnières).

Walter Feilchenfeldt, Vincent van Gogh: The Years in France; Complete Paintings 1886–1890: Dealers, Collectors, Exhibitions, Provenance (London: Philip Wilson, 2013), 30, 33n53, 84, 295, 298, 312–13, 319, (repro.), as Restaurant Crystal, Restaurant Rispal at Asnières, and Vue d’Asnières, avec marronniers en fleurs.

Ralph Skea, Vincent’s Trees: Paintings and Drawings by Van Gogh (London: Thames and Hudson, 2013), 54–55, (repro.), as The Rispal Restaurant at Asnières.

Ingo F. Walther, ed., Impressionism, 1860–1920 (Cologne: Taschen GmbH, 2013), 282, 666, (repro.), as Restaurant Rispal at Asnières.

Diane Stafford, “Bloch Gift to Go for Nelson Upgrade,” Kansas City Star 135, no. 203 (April 8, 2015): A8.

“Gallery Renovation Will Showcase Bloch Collection,” Member Magazine (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (Summer 2015): 14, (repro.), as Restaurant Rispal at Asnières.

“Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Officially Accessions Bloch Impressionist Masterpieces,” Artdaily.org (July 25, 2015): https://artdaily.cc/news/80246/Nelson-Atkins-Museum-of-Art-officially-accessions-Bloch-Impressionist-masterpieces#.YeiPs_hMGUk, (repro.), as Restaurant Rispal at Asnières.

Julie Paulais, “Le Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art reçoit des tableaux impressionnistes en échange de leurs répliques,” Le Journal des arts (July 30, 2015): unpaginated.

Josh Niland, “The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Acquires a Renowned Collection of Impressionist and Postimpressionist Art,” Architectural Digest blog (August 6, 2015): https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/nelson-atkins-museum-accessions-bloch-art-collection, (repro.), as Restaurant Rispal at Asnières.

Nancy Staab, “Van Gogh is a Go!” 435: Kansas City’s Magazine (September 2015): 75–76, (repro.), as Restaurant Rispal.

“Nelson-Atkins to unveil renovated Bloch Galleries of European Art in winter 2017,” Artdaily.org (July 20, 2016): https://artdaily.cc/news/88852/Nelson-Atkins-to-unveil-renovated-Bloch-Galleries-of-European-Art-in-winter-2017-#.YeiQUfhMGUk, as Restaurant Rispal at Asnières.

“Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art celebrates generosity of Henry Bloch with new acquisition,” Artdaily.org (October 18, 2016): https://artdaily.cc/news/90923/Nelson-Atkins-Museum-of-Art-celebrates-generosity-of-Henry-Bloch-with-new-acquisition#.YeiQYfhMGUk.

Kelly Crow, “Museum Rewards Donor with Fake Art to Hang at Home,” Wall Street Journal (January 25, 2017): https://www.wsj.com/articles/museum-rewards-donor-with-fake-art-to-hang-at-home-1485370768, (repro.), as Restaurant Rispal at Asnières.

David Frese, “Bloch savors paintings in redone galleries,” Kansas City Star (February 25, 2017): 1A.

Albert Hecht, “Henry Bloch’s Masterpieces Collection to Go on Display at Nelson-Atkins Museum,” Jewish Business News (February 26, 2017), http://jewishbusinessnews.com/2017/02/26/henry-bloch-masterpieces-collection/.

David Frese, “How Henry Bloch acquired the paintings in the new galleries at Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art,” Kansas City Star 137, no. 169 (March 5, 2017): 1D, 4D–6D, (repro.), as Restaurant Rispal at Asnières.

Hampton Stevens, “Impressionist masterpieces are simply radiant,” Kansas City Star 137, no. 169 (March 5, 2017): 1D, 8D, (repro.), as Restaurant Rispal at Asnières.

Kansas City Star editorial board, “Editorial: Thank you, Henry and Marion Bloch,” Kansas City Star (March 7, 2017): http://www.kansascity.com/opinion/editorials/ article137040948.html [repr. “Thank you, Henry and Marion Bloch,” Kansas City Star 137, no. 172 (March 8, 2017): 16A].

Hampton Stevens, “(Not Actually) 12 Things To Do During The Big 12 Tournament,” Flatland: KCPT’s Digital Magazine (March 9, 2017): http://www.flatlandkc.org/arts-culture/sports/not-actually-12-big-12-tournament/.

Laura Spencer, “The Nelson-Atkins’ Bloch Galleries feature Old Masterworks and New Technology,” KCUR (March 10, 2017): http://kcur.org/post/nelson-atkins-bloch-galleries-feature-old-masterworks-and-new-technology#stream/0.

Victoria Stapley-Brown, “Nelson-Atkins Museum’s new European art galleries come with a ‘love story,’” Art Newspaper (March 10, 2017): http://theartnewspaper.com/news/museums/nelson-atkins-museum-s-new-european-art-galleries-come-with-a-love-story/.

Harry Bellet, “Don du ciel pour le Musée Nelson-Atkins,” Le Monde (March 13, 2017): http://www.lemonde.fr/arts/article/2017/03/13/don-du-ciel-pour-le-musee-nelson-atkins_5093543_1655012.html.

Menachem Wecker, “Jewish Philanthropist Establishes Kansas City as Cultural Mecca,” The Forward (March 14, 2017): http://forward.com/culture/365264/jewish-philanthropist-establishes-kansas-city-as-cultural-mecca/ [repr. in Menachem Wecker, “Kansas City Collection Is A Chip Off the Old Bloch,” Forward (March 17, 2017): 20–22].

Juliet Helmke, “The Bloch Collection Takes up Residence in Kansas City’s Nelson Atkins Museum,” BlouinArtInfo International (March 15, 2017): http://www.blouinartinfo.com/news/story/2005267/the-bloch-collection-takes-up-residence-in-kansas-citys

Erich Hatala Matthes, “Digital replicas are not soulless—they help us engage with art,” Apollo: The International Art Magazine (March 23, 2017): https://www.apollo-magazine.com/digital-replicas-3d-printing-original-artworks/.

Louise Nicholson, “How Kansas City got its magnificent museum,” Apollo (April 7, 2017): https://www.apollo-magazine.com/how-kansas-city-got-its-magnificent-museum/.

Lilly Wei, “Julián Zugazagoitia: ‘Museums should generate interest and open a door that leads to further learning,’” Studio International (August 21, 2017): http://studiointernational.com/index.php/julian-zugazagoitia-director-nelson-atkins-museum-of-art-kansas-city-interview, (repro.).

Jan Blanc, Van Gogh: Ni Dieu Ni Maître (Paris: Citadelles et Mazenod, 2017), 115.

Robert D. Hershey Jr., “Henry Bloch, H&R Block’s cofounder, dies at 96,” Boston Globe (April 23, 2019): https://www3.bostonglobe.com/metro/obituaries/2019/04/23/henry-bloch-block-cofounder/.

Robert D. Hershey Jr., “Henry W. Bloch, Tax-Preparation Pioneer (and Pitchman), Is Dead at 96,” New York Times (April 23, 2019): https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/23/obituaries/henry-w-bloch-dead.html.

Claire Selvin, “Henry Wollman Bloch, Collector and Prominent Benefactor of Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Is Dead at 96,” ArtNews (April 23, 2019): http://www.artnews.com/2019/04/23/henry-bloch-dead-96/.

“Henry Wollman Bloch (1922–2019),” Art Forum (April 24, 2019): https://www.artforum.com/news/henry-wollman-bloch-1922-2019-79547.

Megan McDonough, “Henry Bloch, whose H&R Block became world’s largest tax-services provider, dies at 96,” Washington Post (April 23, 2019): https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/obituaries/henry-bloch-whose-handr-block-became-worlds-largest-tax-services-provider-dies-at-96/2019/04/23/19e95a90-65f8-11e9-a1b6-b29b90efa879_story.html.

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “Henry Bloch, co-founder of H&R Block, dies at 96,” Kansas City Star 139, no. 219 (April 24, 2019): 1A.

Frank Morris, “Henry Bloch, Co-Founder Of H&R Block, Dies At 96,” NPR.org (April 24, 2019): https://www.npr.org/2019/04/24/716641448/henry-bloch-co-founder-of-h-r-block-dies-at-96.

Ignacio Villarreal, “Nelson-Atkins mourns loss of Henry Bloch,” ArtDaily.org (April 24, 2019): http://artdaily.com/news/113035/Nelson-Atkins-mourns-loss-of-Henry-Bloch#.XMB76qR7laQ, as Restaurant Rispal at Asnières.

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “H&R Block co-founder, philanthropist Bloch dies,” The Cass County Democrat Missourian 140, no. 29 (April 26, 2019): 1A.

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “KC businessman and philanthropist Henry Bloch dies,” Lee’s Summit Journal 132, no. 79 (April 26, 2019): 1A.

Luke Nozicka, “Family and friends remember Henry Bloch of H&R Block,” Kansas City Star 139, no. 225 (April 30, 2019): 4A [repr. Luke Nozicka, “Family and friends remember Henry Bloch of H&R Block,” Kansas City Star 139, no. 228 (May 3, 2019): 3A].

Eric Adler, “Sold for $3.25 million, Bloch’s home in Mission Hills may be torn down,” Kansas City Star 141, no. 90 (December 16, 2020): 2A.