![]()

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Jane Avril Looking at a Proof, 1893

| Artist | Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, French, 1864–1901 |

| Title | Jane Avril Looking at a Proof |

| Object Date | 1893 |

| Alternate and Variant Titles | Jane Avril regardant une épreuve; Jane Avril: “La Mélinite”; Jane Avril Examining a Proof, study for cover of ‘L’Estampe Originale’ |

| Medium | Oil and dry media/crayon on paper |

| Dimensions (Unframed) | 20 1/4 × 12 5/8 in. (51.4 × 32.1 cm) |

| Credit Line | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Gift of Henry W. and Marion H. Bloch, 2015.13.27 |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Jane Avril Looking at a Proof, 1893,” catalogue entry in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.732.5407

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Jane Avril Looking at a Proof, 1893,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.732.5407.

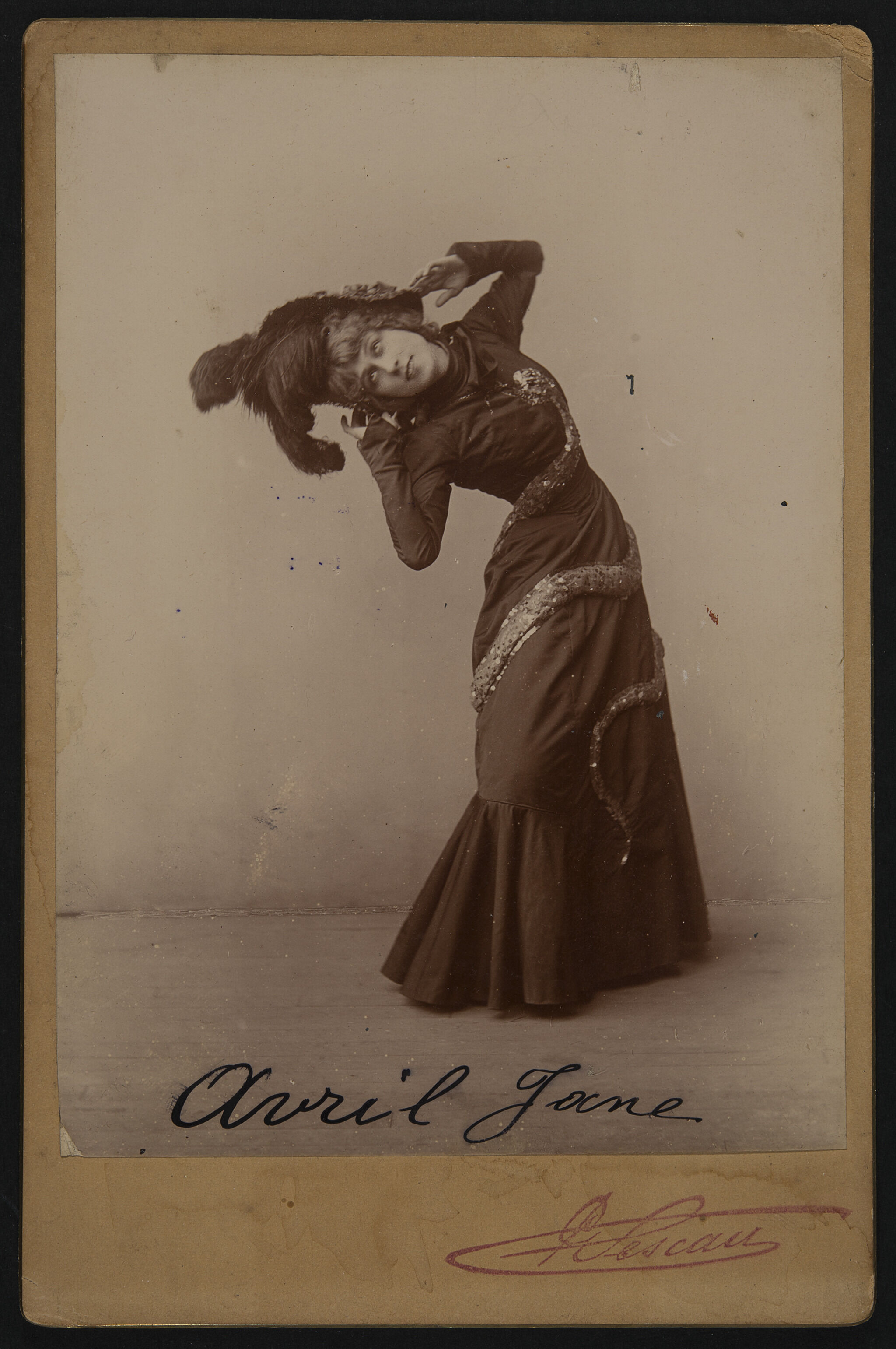

In the opening scene of John Huston’s classic film Moulin Rouge (1952), Jane Avril, played by the Hungarian American actress Zsa Zsa Gabor, is presented as the refined antipode to her fellow entertainer La Goulue (née Louise Weber, 1866–1929). Whereas La Goulue and her costar Aicha throw cognac at one another and, in the words of impresario Charles Zidler, “behave like alley cats,” Avril sings a sentimental ballad and sashays elegantly across the dancehall, enchanting its patrons.1The ballad’s title, “It’s April Again,” is a play on her name, since Avril means April in French. As is often the case with Hollywood, this characterization is partly fictional. Although Avril did perform solo at the famed Paris nightclub and appealed to less raucous cabaret-goers, she was best known for her idiosyncratic style of dance, not her singing. In 1893, when Avril had been appearing at the Moulin Rouge for four years, the art critic Arsène Alexandre described her routine as follows:

She dances, this one, she dances with lateral movements of her legs, back and forth, combining the motions of a jig and an eel, these comical and above all very gracious movements of a female Hanlon that Jane Avril has adapted so originally from English dance, but which she has given a Montmartre accent in the process that, decidedly, it was lacking.2Arsène Alexandre, “Celle qui danse,” supplement to L’Art français (July 29, 1893), repr. and trans. in Nancy Ireson, ed., Toulouse-Lautrec and Jane Avril: Beyond the Moulin Rouge, exh. cat. (London: Courtauld Gallery, 2011), 130–33, at 131. “Elle danse, celle-là, elle danse avec ces mouvements latéraux des jambes, ces sortes de mouvements de gigue et d’anguille, ces très comiques et surtout gracieux mouvements d’hanlon femelle, que Jane Avril si originalement adaptés de la danse anglaise, mais en leur donnant l’accent montmartrois qui, décidément, leur manquait.”

By comparing Avril to the world-famous Hanlon-Lees acrobatic troupe, whose act combined gymnastic feats with knockabout comedy, Alexandre emphasized both the athletic and droll elements of her performance. These features earned her the nickname La Mélinite, an allusion to a French brand of explosives.3Helen Burnham, Toulouse-Lautrec and the Stars of Paris, exh. cat. (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 2019), 39. But neither version of Avril—the singing sensation romanticized in Moulin Rouge or the quirky dancer critiqued by Alexandre—finds visual confirmation in Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s oil sketch Jane Avril Looking at a Proof. Instead, Toulouse-Lautrec recorded his close friend in a moment of quiet contemplation, away from the public eye.

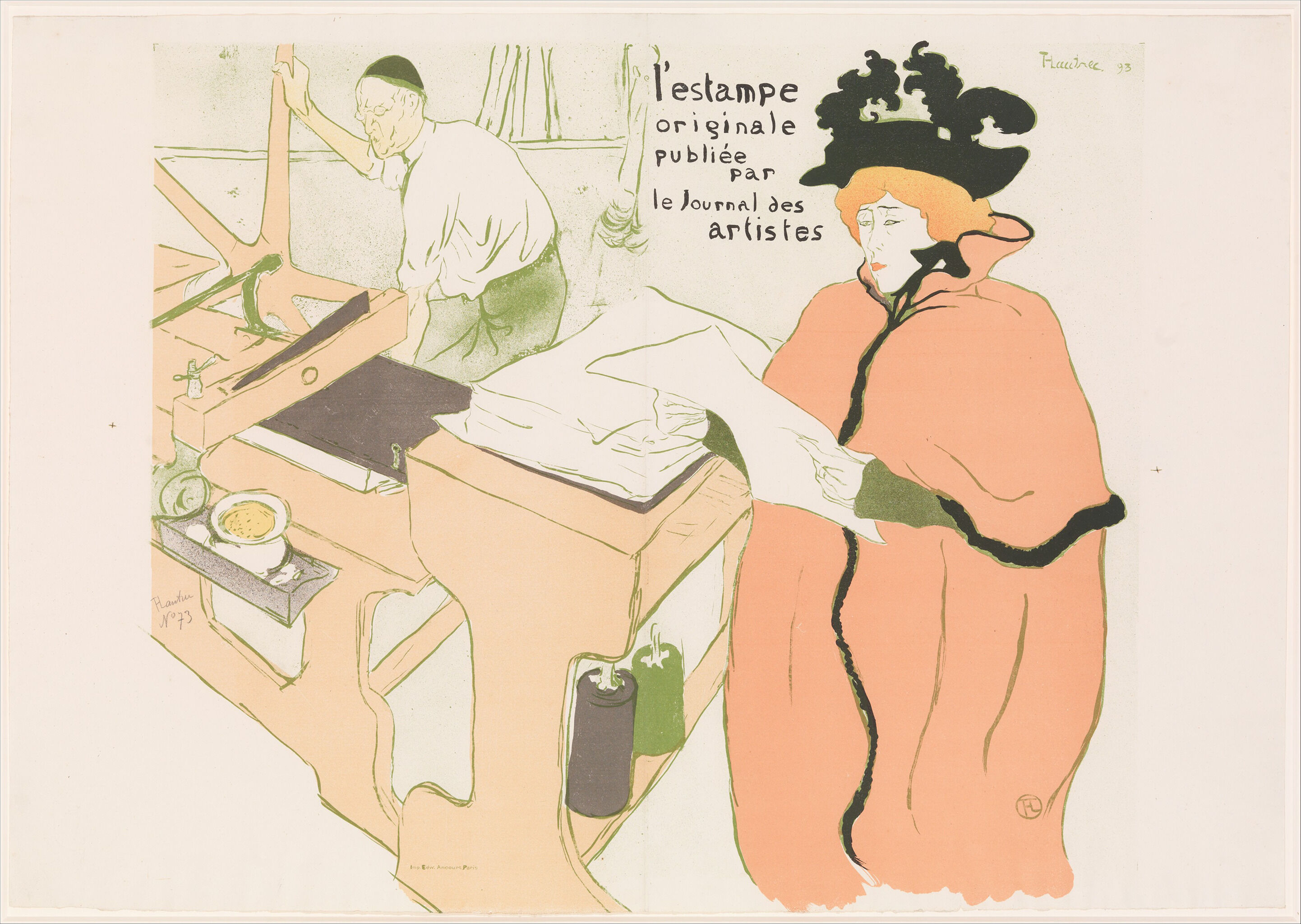

On a formal level, Jane Avril Looking at a Proof distinguishes itself from the Estampe originale cover through its pared-down detail and “hesitation-free execution.”12I borrow this term from Luciano Migliaccio, “Toulouse-Lautrec at MASP: The Scandalous Trace of Freedom,” in Adriano Pedrosa, ed., Toulouse-Lautrec: Em vermelho [in red], exh. cat. (São Paulo: Museu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand, 2017), 60–72, at 63. Although the sketch was included in François Daulte’s monograph French Watercolors of the 20th Century (1968), it is not, in fact, a watercolor.13See François Daulte, French Watercolors of the 20th Century (New York: Viking, 1968), 36–37. Employing a technique known as peinture à l’essencepeinture à l’essence: De-oiled paint. Peinture à l’essence was produced by the artist by leaching much of the linseed oil out of commercial paints and mixing the resulting thickened paint with turpentine. The resulting paint could be applied as a wash and dried more quickly than unmodified paint., Toulouse-Lautrec diluted oil paint with a solvent (probably turpentine), allowing him to apply pigment swiftly over the paper support.14See technical notes by Nancy Heugh, Heugh-Edmondson Conservation Services, December 18, 2016, NAMA conservation files. This rapid brushwork is particularly evident in Avril’s feathered hat and bright red hair. Whereas in the Estampe originale cover her headwear is solid black, unmodeled, and clearly silhouetted, in the sketch it is a muddle of aubergine, mauve, and indigo, heightening its sense of texture and blurring its profile.15Here, I am describing the shades of purple seen in Avril’s headwear, rather than identifying specific dyes present in the Nelson-Atkins sketch. Likewise, the spatter pattern that gives volume to Avril’s coiffure in the lithograph contrasts with the jagged, irregular strokes above her ear in the oil sketch. While these differences stem from the possibilities and limitations of each medium, the painting nevertheless possesses a raw immediacy unmatched in the lithograph.

Notes

-

The ballad’s title, “It’s April Again,” is a play on her name, since Avril means April in French.

-

Arsène Alexandre, “Celle qui danse,” supplement to L’Art français (July 29, 1893), repr. and trans. in Nancy Ireson, ed., Toulouse-Lautrec and Jane Avril: Beyond the Moulin Rouge, exh. cat. (London: Courtauld Gallery, 2011), 130–33, at 131. “Elle danse, celle-là, elle danse avec ces mouvements latéraux des jambes, ces sortes de mouvements de gigue et d’anguille, ces très comiques et surtout gracieux mouvements d’hanlon femelle, que Jane Avril si originalement adaptés de la danse anglaise, mais en leur donnant l’accent montmartrois qui, décidément, leur manquait.”

-

Helen Burnham, Toulouse-Lautrec and the Stars of Paris, exh. cat. (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 2019), 39.

-

Gabriel P. Weisberg, “Consuming Jane Avril: The Mystery of Celebrity Culture in the Symbolist Age,” in European Drama and Performance Studies: Consuming Female Performers (1850s–1950s), ed. Sabine Chacouche and Clara Sadoun-Édouard (Paris: Classiques Garnier, 2015), 281–302, at 284. Charcot admitted Avril on December 28, 1882, and released her on July 11, 1884.

-

Nancy Ireson, “Dancing in the Asile: Jane Avril and Chorea,” in Toulouse-Lautrec and Jane Avril, 42–57, at 52.

-

The Biblioteca Nacional de España proposes a date of 1888 for this photograph, but I follow Sarah Suzuki in dating it to circa 1893; see Sarah Suzuki, The Paris of Toulouse-Lautrec: Prints and Posters from the Museum of Modern Art, exh. cat. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2014), 46. For Sescau’s life and career, see Steven F. Joseph, “Paul Sescau: Toulouse-Lautrec’s Elusive Neighbour,” History of Photography 37, no. 2 (May 2013): 153–66.

-

G[abriele] M[andel] Sugana, The Complete Paintings of Toulouse-Lautrec (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1969), 83.

-

François Caradec, Jane Avril: Au Moulin Rouge avec Toulouse-Lautrec (Paris: Fayard, 2001), 88.

-

Claire Frèches-Thory, Anne Roquebart, and Richard Thomson, Toulouse-Lautrec, exh. cat. (London: South Bank Centre, 1991), 386.

-

About halfway through the film, Toulouse-Lautrec and Père Cotelle collaborate on a color poster of Avril, which is subsequently displayed on kiosks across Paris.

-

Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 134.

-

I borrow this term from Luciano Migliaccio, “Toulouse-Lautrec at MASP: The Scandalous Trace of Freedom,” in Adriano Pedrosa, ed., Toulouse-Lautrec: Em vermelho [in red], exh. cat. (São Paulo: Museu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand, 2017), 60–72, at 63.

-

See François Daulte, French Watercolors of the 20th Century (New York: Viking, 1968), 36–37.

-

See technical notes by Nancy Heugh, Heugh-Edmondson Conservation Services, December 18, 2016, NAMA conservation files.

-

Here, I am describing the shades of purple seen in Avril’s headwear, rather than identifying specific dyes present in the Nelson-Atkins sketch.

-

Weisberg, “Consuming Jane Avril,” 299.

-

For more on the carrick coat, see Yana Glemaud, “Carrick Coat,” Fashion History Timeline, Fashion Institute of Technology, December 12, 2018, https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/carrick-coat/; and Virginia Schreffler Wimberley, “Empire Dress and Fashion,” in José Blanco F. and Patricia Hunt-Hurst, eds., Clothing and Fashion: American Fashion from Head to Toe, vol. 2, The Federal Era through the 19th Century (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2015), 112–15.

-

Weisberg, “Consuming Jane Avril,” 291.

-

For more on this portrait, see Sarah Lees, ed., Nineteenth-Century European Paintings at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute (Williamstown: Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, 2012), 2:794–97.

-

Weisberg, “Consuming Jane Avril,” 294.

-

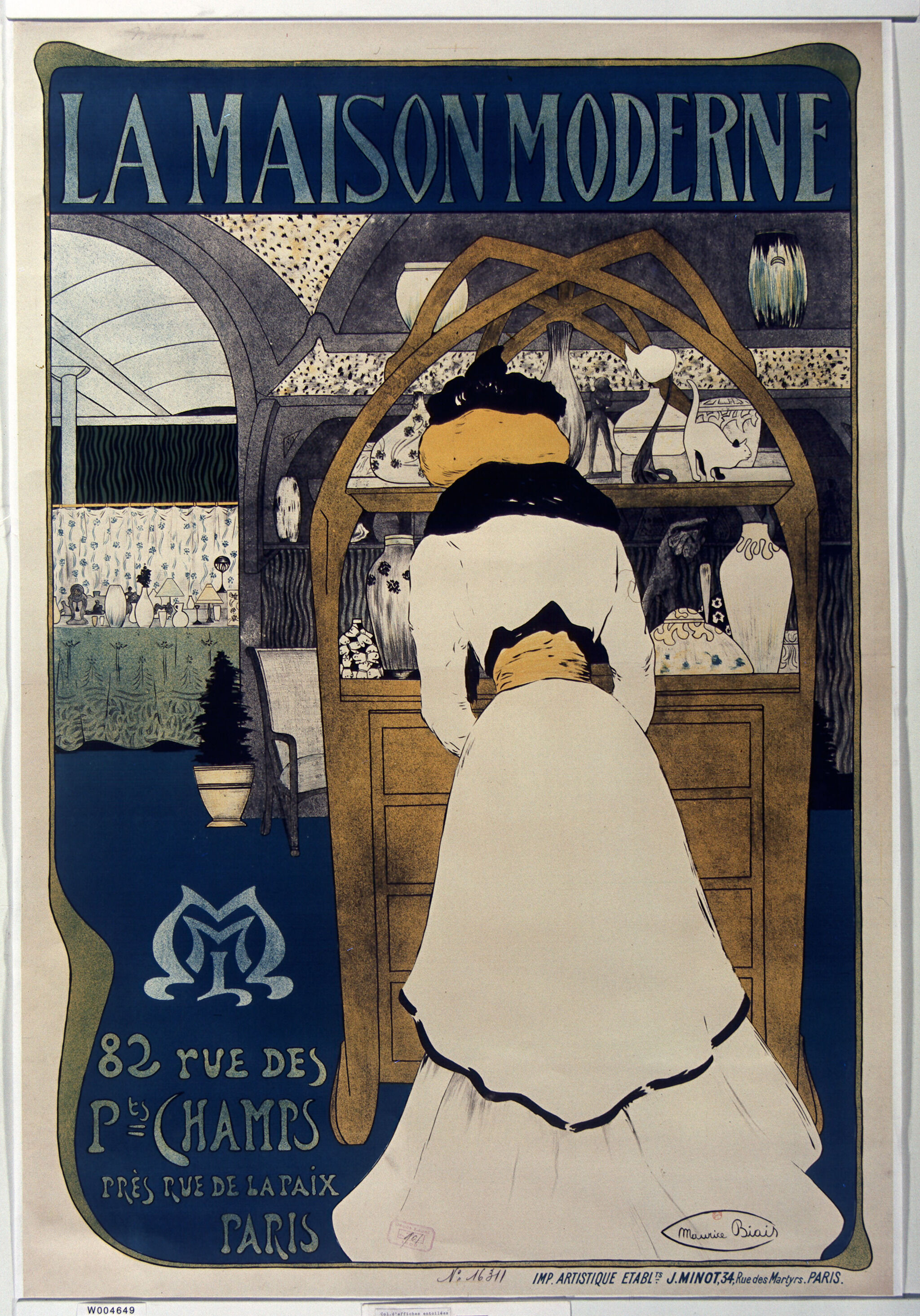

Weisberg was the first to identify the woman in this lithograph as Avril; see Gabriel P. Weisberg, “The Urban Mirror: Contrasts in the Vision of Existence in the Modern City,” in Carrie Haslett et al., Paris and the Countryside: Modern Life in late 19th-Century France, exh. cat. (Portland, ME: Portland Museum of Art, 2006), 1–62, at 1. For a discussion of Biais’s formal appropriations from the German satirical magazine Simplicissimus, see Sarah Sik, “Pirated Posters: International Print Politics and The Graphic Art of Maurice Biais,” in Hardy S. George and Gabriel P. Weisberg, Paris 1900, exh. cat. (Oklahoma City: Oklahoma City Museum of Art, 2007), 110–29. The Bibliothèque nationale de France dates Biais’s lithograph to 1902, but I follow Weisberg and Sik in dating it to circa 1900.

-

Bertrand Mothes, “La Maison Moderne de Julius Meier-Graefe,” in Catherine Méneux, Emmanuel Pernoud, and Pierre Wat, eds., Actualité de la recherche en XIXe siècle: Master 1 (2012–2013) (Paris: Histoire culturelle et sociale de l’art, 2014), 1–22, at 16, https://hicsa.univ-paris1.fr/page.php?r=133&id=681&lang=fr..

-

Eileen Chanin and Steven Miller, Degenerates and Perverts: The 1939 Herald Exhibition of French and British Contemporary Art (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2005), 17.

-

Chanin and Miller, Degenerates and Perverts, 197.

-

John Goodchild, “‘The Advertiser’ Art Exhibition: Lunch Hour Lecture Arranged,” The Advertiser (Adelaide), August 23, 1939. Toulouse-Lautrec’s sketch is the sole illustration in this article.

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Rachel Freeman, “Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Jane Avril Looking at a Proof, 1893,” technical entry in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.732.2088

MLA:

Freeman, Rachel. “Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Jane Avril Looking at a Proof, 1893,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.732.2088.

Jane Avril Looking at a Proof by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1863–1901) is a color study for the cover of the first volume of L’Estampe originale. Although executed in peinture à l’essencepeinture à l’essence: De-oiled paint. Peinture à l’essence was produced by the artist by leaching much of the linseed oil out of commercial paints and mixing the resulting thickened paint with turpentine. The resulting paint could be applied as a wash and dried more quickly than unmodified paint., a painting medium, the paper ties the painting to the lithography process, and the secondary media, wax crayoncrayon: Traditionally, the French term crayon referred to a wide variety of fabricated, dry drawing media including ground and compressed chalks and pastels. For the purposes of this catalogue, crayon refers to a drawing medium where pigments, dyes, or a mixture of the two are mixed with wax, grease, or oils, or any combination of the three, and compressed into a stick., offers insight into Toulouse-Lautrec’s composition for the print.

Toulouse-Lautrec used a cream to beige machine-made, medium-thick, smooth-surfaced wove paperwove paper: One of the two types of paper. Wove papers may be either machine or handmade, and are produced from molds that have a woven wire mesh. The weave of the mesh can be so tight that it produces no visible pattern within the paper sheet, and often wove papers have a smoother surface than laid papers. Wove papers were developed during the mid-eighteenth century, but did not come into widespread use until later. The other type of paper is laid paper.,1The description of paper color/texture/thickness follows the standard set forth in Elizabeth Lunning and Roy Perkinson, The Print Council of America Paper Sample Book: A Practical Guide to the Description of Paper (Boston: Print Council of America, 1996), unpaginated. which was torn down after media application. The front of the paper was prepared with a tinted, water-soluble coating that shifts the paper tone to a muted yellow.2Solubility testing was carried out by Nancy Heugh. Nancy Heugh, technical examination and condition report for French Painting Catalogue Project, October 2015–September 2016, NAMA conservation file, no. 2015.13.27. The coating is slightly glossy and transparent and has no visible brush strokes. Scattered along the left edge, and in a single location in the upper left quadrant, are tiny ruptures in the coating through which the paper fibers are visible. The paper is stiffer than uncoated papers of the same thickness, and the coating has rendered the torn edges jagged and brittle. There are no oil halos on the back of the paper (Fig. 6), indicating that the coating was an effective barrier against residual drying oilsdrying oil: Drying oils are oils which have the property of forming a solid, elastic substance when exposed to the air. Drying oils that commonly occur in oil paints are linseed, walnut, and poppyseed. in the paint.

Fig. 8. Photomicrograph of Jane Avril Looking at a Proof (1893) showing the fingerprint within the plumage on the hat.

Fig. 8. Photomicrograph of Jane Avril Looking at a Proof (1893) showing the fingerprint within the plumage on the hat.

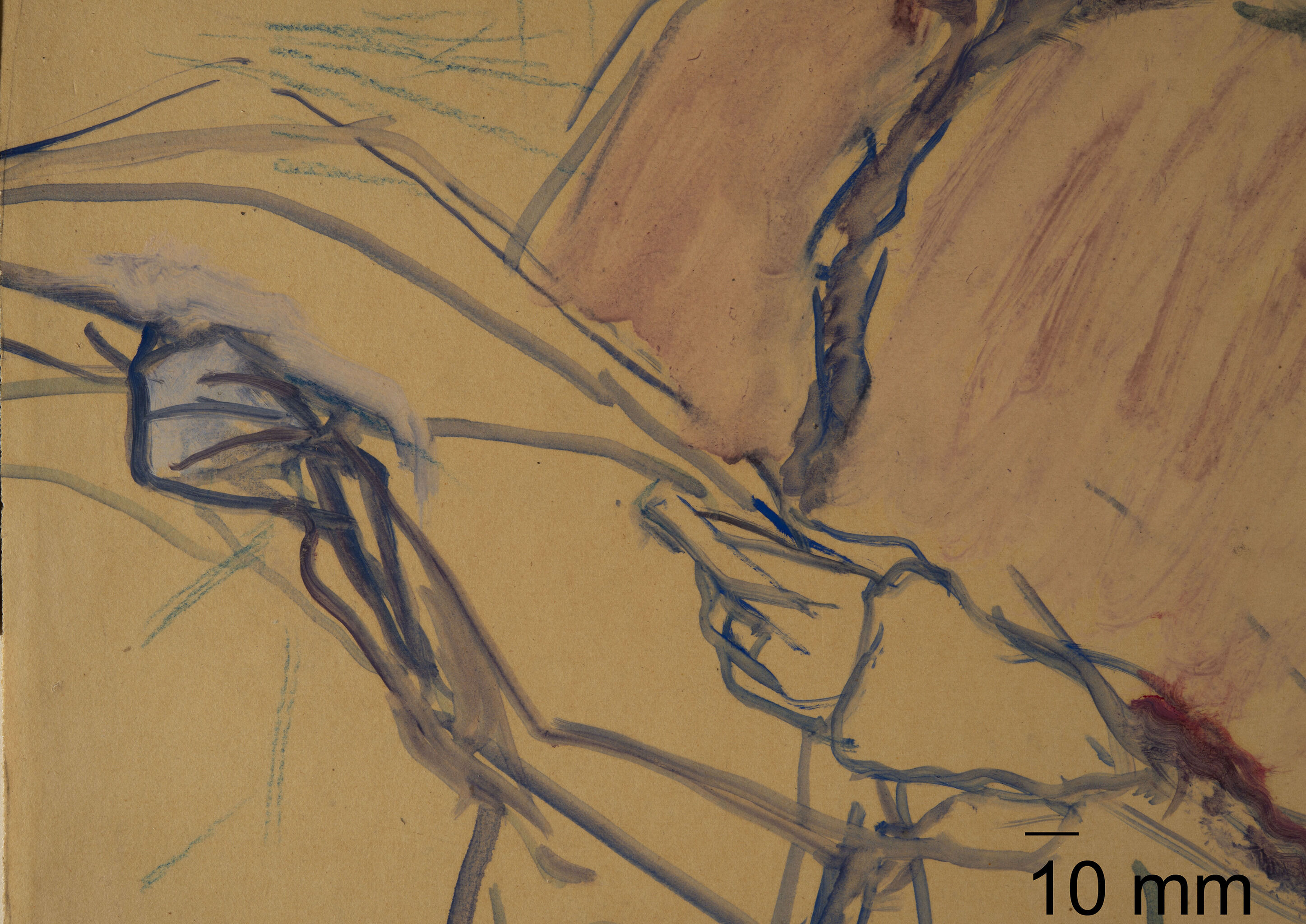

Fig. 9. Detail of Avril’s hands with the printing proofs in Jane Avril Looking at a Proof (1893). This is the only area of the image where Lautrec changed the placement of the lines.

Fig. 9. Detail of Avril’s hands with the printing proofs in Jane Avril Looking at a Proof (1893). This is the only area of the image where Lautrec changed the placement of the lines.

Fig. 10. Photomicrograph of Jane Avril Looking at a Proof (1893) showing the crayon line along the upper edge of the work. This line cuts through the wet paint.

Fig. 10. Photomicrograph of Jane Avril Looking at a Proof (1893) showing the crayon line along the upper edge of the work. This line cuts through the wet paint.

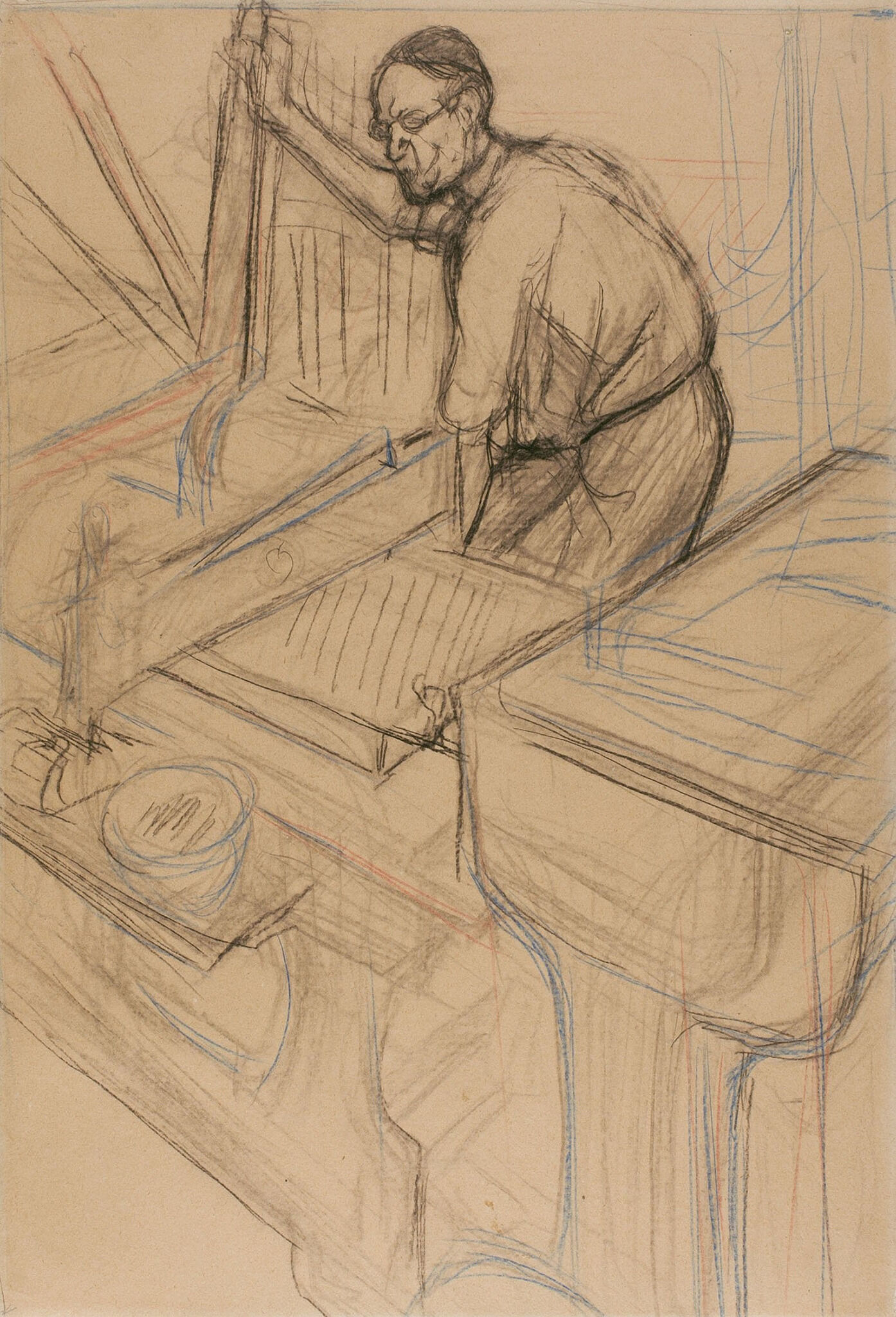

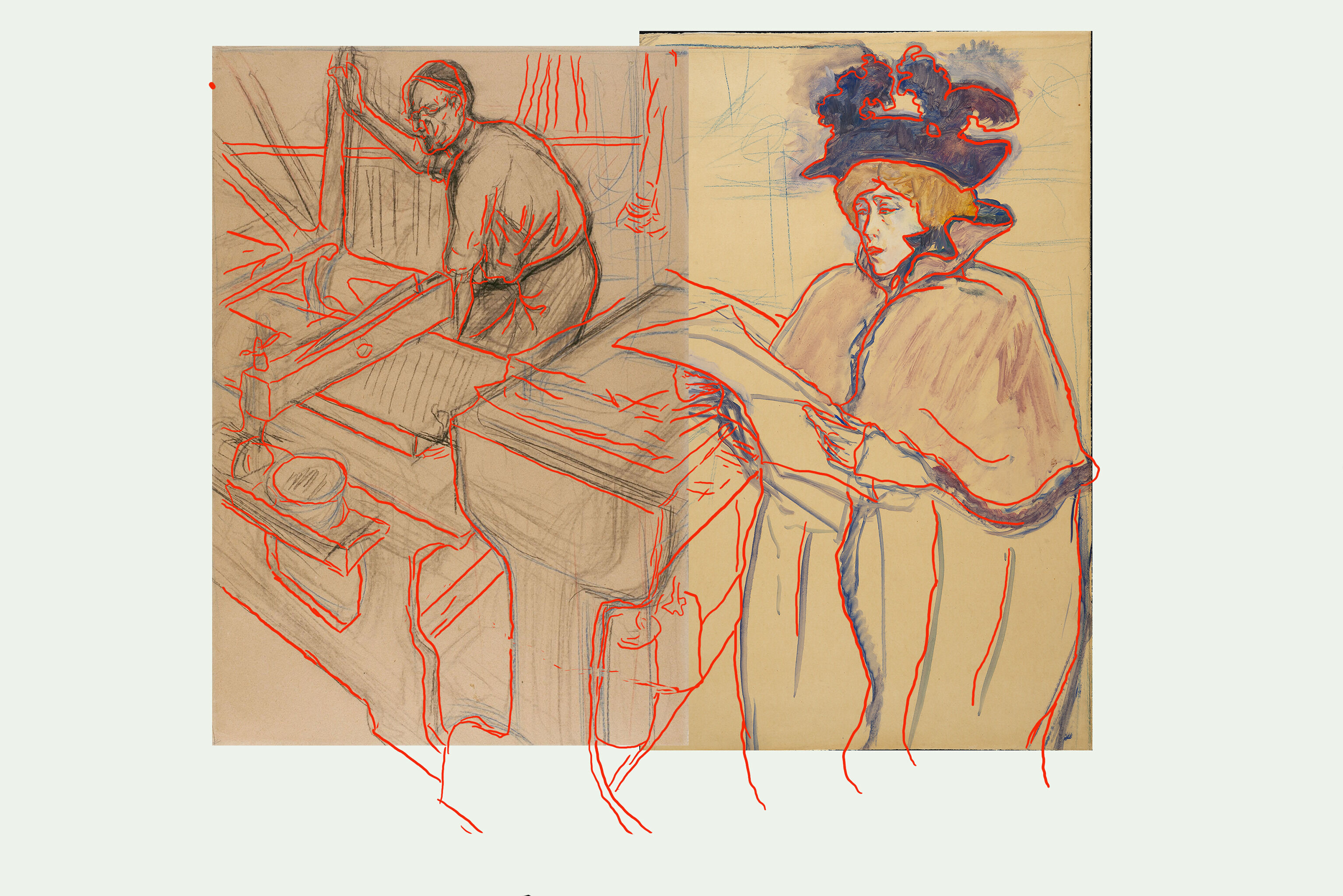

If Study and Jane Avril Looking at a Proof are examined on a line-by-line basis, it is clear that some of the crayon lines overlap both works (Fig. 12). The blue and red crayon lines along the upper edge of Jane Avril Looking at a Proof begin on Study and correspond to the upper edge of the printed image. The three blue lines below Avril’s hands match the lines of the paper stand in Study. The two blue crayon lines that form a point in the center of the paper stack in Study become the corner of the print that Avril is examining. Moving upward, the five blue crayon lines that intersect the print and Jane Avril’s coat are the back edge of the paper stack.

Fig. 12. In this image, Study and Jane Avril Looking at a Proof (1893) are shown at their correct size ratio. The works are aligned along the blue crayon lines at the top of the paper. Places where the crayon lines overlap both artworks are noted in red and include, from top to bottom: the upper border of the print, the paper stack, the corner of the print in Avril’s hands, and the paper stand at the foot of the press.

Fig. 12. In this image, Study and Jane Avril Looking at a Proof (1893) are shown at their correct size ratio. The works are aligned along the blue crayon lines at the top of the paper. Places where the crayon lines overlap both artworks are noted in red and include, from top to bottom: the upper border of the print, the paper stack, the corner of the print in Avril’s hands, and the paper stand at the foot of the press.

Fig. 13. In this image, the size ratio between Study and Jane Avril Looking at a Proof (1893) has been adjusted, and the drawings are overlapped to show how they correspond with the print. The red lines indicate the keystone lines in the lithograph, and the composite image shows how close Lautrec’s painted and drawn lines are to the major compositional features in the print.

Fig. 13. In this image, the size ratio between Study and Jane Avril Looking at a Proof (1893) has been adjusted, and the drawings are overlapped to show how they correspond with the print. The red lines indicate the keystone lines in the lithograph, and the composite image shows how close Lautrec’s painted and drawn lines are to the major compositional features in the print.

Jane Avril Looking at a Proof was edge mounted; however, the acidic and degraded brown paper backing was removed in a 2016 conservation campaign. Except for possible fading of the pigments and staining from an acidic face mat, the painting is in good condition.

Notes

-

The description of paper color/texture/thickness follows the standard set forth in Elizabeth Lunning and Roy Perkinson, The Print Council of America Paper Sample Book: A Practical Guide to the Description of Paper (Boston: Print Council of America, 1996), unpaginated.

-

Solubility testing was carried out by Nancy Heugh. Nancy Heugh, technical examination and condition report for French Painting Catalogue Project, October 2015–September 2016, NAMA conservation file, no. 2015.13.27.

-

Transfer lithography played a pivotal role in the revival of lithography as a fine art, and one of the prints associated with L’Estampe originale Album IV (published in October–December 1893), The Draped Figure Seated, is a transfer lithograph by James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903). Because Toulouse-Lautrec’s cover for L’Estampe originale is not a reversal of the preliminary drawings, it is possible that the design was transferred to stone using lithographic transfer paper.

-

Henry John Rhodes, The Art of Lithography: A Complete Practical Manual of Planographic Printing (London: Scott, Greenwood and Son, 1914), 52–54. https://archive.org/details/artoflithography00rhod/page/n7/mode/2up.

-

At the time of writing, the presence of gamboge in the coating is not confirmed. Gamboge is a yellow colorant extracted from trees of the Garcinia as a gum resin. When it is ground and applied as a watercolor, it produces a bright yellow color with full spectrum illumination and a green yellow fluorescence with ultraviolet light. Unfortunately, gamboge is light sensitive, and the yellow color fades quickly. John Winter, “Gamboge” in Artists’ Pigments: A Handbook of Their History and Characteristic, ed. Elisabeth West Fitzhugh (Oxford: National Gallery of Art, Washington and Oxford University Press, 1997), 3:143–55.

-

Linda Stiber Morenus, “Joseph Pennell and the Art of Transfer Lithography,” Print Quarterly 21, no. 3 (September 2004): 248–65.

-

Helmut Schweppe and John Winter, “Madder and Alizarin,” in Artists’ Pigments, 3:109–42.

-

I am grateful to paper conservator Kristi Dahm, department of conservation and science, The Art Institute of Chicago, for her observations of the paper and media. Email correspondence, September 28, 2020.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Jane Avril Looking at a Proof, 1893,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.614.4033

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Jane Avril Looking at a Proof, 1893,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.614.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Jane Avril Looking at a Proof, 1893,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.614.4033

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Jane Avril Looking at a Proof, 1893,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.614.4033.

Jean-André Marty (1857–1928), Paris, by March 1893;

Purchased from Jean-André Marty by Scossa [1];

Louis Bernard, Paris [2];

Dr. George Viau (1855–1939), Paris [3];

With [Hugh] Willoughby, London, and André Schoeller, Paris, by September 25, 1921;

Purchased from [Hugh] Willoughby and André Schoeller by Galerie Wildenstein, Paris, September 25, 1921–31 [4];

Transferred from Galerie Wildenstein, Paris, stock no. 1189d, to Wildenstein, New York, by 1931 [5];

Transferred from Wildenstein, New York, to Galerie Wildenstein, Paris, by August 1939 [6];

Transferred from Galerie Wildenstein, Paris to Wildenstein, New York, by October 23, 1946–August 1956 [7];

Purchased from Wildenstein and Co., New York, by David (1898–1982) and Anne (1903–72) Rosenthal, Scarsdale, NY, New York City, and West Palm Beach, FL, August 1956–at least November 1972;

With John and Paul Herring and Company, New York, by October 6, 1977;

Purchased from John and Paul Herring and Company by Marion (née Helzberg, 1931–2013) and Henry (1922–2019) Bloch, Shawnee Mission, KS, 1977–June 15, 2015;

Their gift to The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 2015.

Notes

[1] See label on the verso, encapsulated, brown paper, eight-sided with blue borders, in faded brown MS ink at top left corner of red paper dust seal: “Jane Avril / couverture de l’Estampe / originale / Edition Marty / Vendu par lui a / la collection / Scossa / puis Collection Louis Bernard”.

[2] Louis Bernard collected extensively around 1900–14. He owned Toulouse-Lautrec’s paintings Monsieur Émile Davoust (1889, Kunsthaus Zurich), Woman Seated in a Garden (1891, National Gallery, London), and Alfred La Guigne (1894, Chester Dale Collection, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC). A separately listed Bernard (no first name given) also owned an oil on cardboard work titled Jane Avril Dancing (private collection). See M.G. Dortu, Toulouse-Lautrec et son œuvre, vol. 2 (New York: Collectors Editions, 1971).

[3] See label on verso (on the upper right side of red paper dust seal), which reads in part, in gray printing ink: “Collection George Viau” and “No.” and in brown and black manuscript ink, handwritten above the printed name: “exchange [sic] contre une etude [sic] par Manet”. The earliest mention for this work being in the Viau collection is: Waldemar George, “La Collection Viau,” L’Amour de l’Art 5, no. 1 (January 1925): 365–66, (repro.), as Portrait de Jeanne Avril. Given the Wildenstein ownership dates of the picture, it is unlikely that Viau owned it in 1925. Phone call from Joseph Baillio, Wildenstein and Co., New York, with Glynnis Napier Stevenson, NAMA, July 24, 2019; see notes in NAMA curatorial files.

[4] Phone call from Joseph Baillio, Wildenstein and Co., New York, with Glynnis Napier Stevenson, NAMA, July 24, 2019; see notes in NAMA curatorial files. Baillio confirmed that Willoughby and Schoeller were working in their capacities as dealers when they sold the drawing to Wildenstein.

[5] Phone call from Joseph Baillio, Wildenstein and Co., New York, with Glynnis Napier Stevenson, NAMA, July 24, 2019, see notes in NAMA curatorial files. Wildenstein, New York, lent the picture to exhibitions in Cleveland in 1933 and Kansas City in 1935.

[6] By August 23, 1939, Galerie Wildenstein, Paris, had sent the drawing to Adelaide, Australia for the Exhibition of French and British Contemporary Art. Due to the upheaval of World War II, the drawing would not return from Australia until 1945–46. See email from Kylie Best, State Library of Victoria, Melbourne, to Glynnis Napier Stevenson, NAMA, July 3, 2019, NAMA curatorial files. In several sources from the 1940s, this work is listed as being in the collection of Georges Wildenstein (1892–1963). All concrete evidence points to the drawing belonging to Wildenstein’s New York and Paris branches rather than to Mr. Wildenstein personally and being transferred between the two gallery locations. The works of art physically located at the Wildenstein Paris gallery were confiscated by the German National Socialist (Nazi) regime in 1940. Since NAMA’s drawing remained in Australia at the time, it did not suffer this fate.

[7] Latest possible date of transfer is the start date (October 23, 1946) of the exhibition A Loan Exhibition of Toulouse-Lautrec, For the Benefit of the Goddard Neighborhood Center, Wildenstein, New York.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Jane Avril Looking at a Proof, 1893,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.614.4033

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Jane Avril Looking at a Proof, 1893,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.614.4033.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Cover for “L’estampe originale”, 1893, color lithograph on paper, 22 3/4 x 26 1/4 in. (57.8 x 66.7 cm), The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Cover for “L’estampe originale”, 1893, lithograph, 22 1/4 x 25 13/16 in. (56.5 x 65.5 cm), The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Cover for “L’estampe originale”, 1893, lithograph printed in six colors on folded wove paper, 22 1/4 × 25 11/16 in. (56.5 × 65.2 cm), The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Le Père Cotelle, 1893, charcoal, with colored crayons, on tan wove paper, 20 x 13 1/2 in. (50.8 x 34.3 cm), Art Institute of Chicago.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Jane Avril, 1893, oil and crayon on cardboard, 19 7/10 x 50 4/5 in. (50 x 129 cm), illustrated in Impressionist and Modern Paintings and Sculpture, part I (New York: Christie, Manson and Woods, May 11, 1988), 48–49.

Theodore van Rysselberghe, Poster for N. Lembrée, Estampes et Encadrements….Brussels, 1897, color lithograph, 27 3/8 x 20 1/8 in. (69.5 x 51 cm), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Jane Avril Looking at a Proof, 1893,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.614.4033

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Jane Avril Looking at a Proof, 1893,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.614.4033.

The Tenth Annual Exhibition of Water Colors and Pastels, Cleveland Museum of Art, January 10–February 12, 1933, no cat., as Jane Avril.

One Hundred Years of French Painting, 1820–1920, The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and The Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Kansas City, MO, March 31–April 28, 1935, no. 60, as Jane Avril.

Exhibition of French and British Contemporary Art, National Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, August 21–September 17, 1939; Lower Town Hall, Melbourne, Australia, October 16–November 1, 1939; David Jones’ Gallery, Sydney, November 20–December 16, 1939; National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, August 1942; National Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, November–December 1943 and October 5–31, 1944, no. 117, as Portrait de Jane Avril.

A Loan Exhibition of Toulouse-Lautrec, For the Benefit of the Goddard Neighborhood Center, Wildenstein, New York, October 23–November 23, 1946, no. 19, as Jane Avril, “La Melinite” [sic].

A Loan Exhibition of Six Masters of Post-Impressionism: Benefit of Girl Scout Council of Greater New York, Wildenstein, New York, April 8–May 8, 1948, no. 28, as Jane Avril, “La Melinite” [sic].

Toulouse-Lautrec, exhibition organized in collaboration with the Albi Museum, Philadelphia Museum of Art, October 29–December 11, 1955; Art Institute of Chicago, January 2–February 15, 1956, no. 42, as Jane Avril: “La Mélinite”.

Toulouse-Lautrec: paintings, drawings, posters and lithographs, Museum of Modern Art, New York, March 20–May 6, 1956, no. 21, as Jane Avril: “La Mélinite”.

Loan Exhibition: Toulouse-Lautrec, Wildenstein, New York, February 7–March 14, 1964, no. 30, as Jane Avril: “La Mélinite”.

Faces from the World of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism: A Loan Exhibition for the Benefit of the New York Chapter of The Arthritis Foundation, Wildenstein, New York, November 2–December 9, 1972, no. 65, as Jane Avril.

The Bloch Collection, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, June–August 1982, no cat.

Toulouse-Lautrec Prints and Drawings, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, October 27–December 9, 1984, no. 22a, no cat., as Jane Avril Examining a Proof, study for cover of “L’Estampe Originale”.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec: Images of the 1890s, Museum of Modern Art, New York, November 7, 1985–January 26, 1986, no. 13, as Jane Avril Looking at a Proof (Jane Avril regardant une épreuve).

Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, June 9–September 9, 2007, no. 26, as Jane Avril Looking at a Proof (Jane Avril regardant une épreuve).

Painters and Paper: Bloch Works on Paper, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, February 20, 2017–March 11, 2018, no cat.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Jane Avril Looking at a Proof, 1893,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.614.4033

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Jane Avril Looking at a Proof, 1893,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.614.4033.

Waldemar George, “La Collection Viau,” L’Amour de l’Art 5, no. 1 (January 1925): 365–66, (repro.), as Portrait de Jeanne Avril.

Maurice Joyant, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, 1864–1901, vol. 2, dessins, estampes, affiches (Paris: Henri Floury, 1927), 202, as Jane Avril regardant une épreuve.

H. S. F., “The Tenth Annual Exhibition of Water Colors and Pastels,” Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 20, no. 1 (January 1933): 6, as Jane Avril.

One Hundred Years French Painting, 1820–1920, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1935), unpaginated, (repro.), as Jane Avril.

M[inna] K. P[owell], “2,000 See Loan Display: Many Masterly Works Are Shown at the Gallery; Exhibition Is the First of Its Kind Here for Which an Illustrated Catalogue Has Been Provided,” Kansas City Times 98, no. 78 (April 1, 1935): 8, as Jane Avril.

Basil Burdett, Exhibition of French and British Contemporary Art: Paintings and Sculpture obtained on loan from public and private collections and brought to Melbourne by “The Herald”, exh. cat. (Melbourne, Australia: Herald, 1939), unpaginated, as Portrait de Jane Avril.

“Famous Paintings in S.A. Show: World-Wide Collection,” Herald (Adelaide), no. 19,424 (August 19, 1939): 7.

Palette, “Modern British and French Collection Is Fine Feast of Art,” News (Adelaide) 33, no. 5,015 (August 21, 1939): 6.

John Goodchild, “‘The Advertiser’ Art Exhibition: Lunch Hour Lecture Arranged,” Advertiser (Adelaide) 82, no. 25,235 (August 23, 1939): 22, (repro.), as De Jane Avril.

The Sun News-Pictorial (Melbourne) (October 11, 1939): unpaginated, (repro.), as Portrait of Jane Avril.

“Modern artists 7. Toulouse-Lautrec: dwarf aristocrat…haunted Montmartre,” The Herald (Melbourne), no. 19,475 (October 16, 1939): 6.

Clive Turnbull, “Visitors Enthusiastic Over Art Show: Influence on Public Appreciation,” The Herald (Melbourne), no. 19,478 (October 19, 1939): 10.

W.S., “Australia’s Most Important Exhibition,” Art in Australia, no. 77 (November 15, 1939): 25.

Jacques Lassaigne, Toulouse Lautrec, trans. Mary Chamot, ed. André Gloeckner (1939; London: Hyperion Press, 1946), 19, 166, (repro.), as Jane Avril. “La Mélinite”.

A Loan Exhibition of Toulouse-Lautrec, For the Benefit of the Goddard Neighborhood Center, exh. cat. (New York: Wildenstein, 1946), 33, (repro.), as Jane Avril, “La Melinite” [sic].

A Loan Exhibition of Six Masters of Post-Impressionism: Benefit of Girl Scout Council of Greater New York, exh. cat. (New York: Wildenstein, 1948), 37, 45, (repro.), as Jane Avril, “La Melinite” [sic].

Henri Dumont, Masters in Art: Lautrec (New York: Hyperion, 194[8]), 35, (repro.), as Jane Avril, “La Melinite” [sic].

Jean Vallery-Radot, Œuvre graphique de Toulouse-Lautrec, exh. cat. (Paris: Bibliothèque nationale, 1951), unpaginated.

M.G. Dortu, Toulouse-Lautrec (Paris: Éditions du Chêne, 1952), 7, (repro.), as Jane Avril regardant une épreuve.

Sam Hunter, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864–1901) (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1953), unpaginated, (repro.), as Jane Avril: “La Melinite” [sic].

Edouard Julien, Pour connaitre Toulouse-Lautrec (Albi, France: Imprimerie Coopérative du Sud-Ouest, 1953), 25, (repro.), as Jane Avril dite la Mélinite.

Jacques Lassaigne, Lautrec: Biographical and Critical Studies, trans. Stuart Gilbert (Geneva: Skira, 1953), 58.

François Daulte, Le dessin Français de Manet à Cézanne (Lausanne, Switzerland: Editions Spes, 1954), xxiv, 37, 62, (repro.), as Portrait de Jane Avril.

Ugo Nebbia, Gallery of Art Series: Toulouse-Lautrec, trans. Cesare Foligno (Milan: Uffici Press, 1954), 16–17, (repro.), as Jane Avril “La Melinite” [sic].

Toulouse-Lautrec, exhibition organized in collaboration with the Albi Museum, exh. cat. (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1956), unpaginated, (repro.), as Jane Avril: “La Mélinite”.

Toulouse-Lautrec: paintings, drawings, posters and lithographs, exh. cat. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1956), 12, 45–46, (repro.), as Jane Avril: “La Mélinite”.

Howard Devree, “About Art and Artists: Toulouse-Lautrec Exhibition at Modern Museum Offers Many Facets of Work,” New York Times 105, no. 35,851 (March 21, 1956): 30.

“Medical Centers To Gain at Tour of Homes June 9: Visits to 6 Houses in Westchester to Help Fibrosis Research,” New York Times 108, no. 37,012 (May 26, 1959): 38.

Edouard Julien, Lautrec (New York: Crown, 1959), unpaginated, (repro.), as Jane Avril.

Philippe Huisman and M.G. Dortu, Lautrec by Lautrec, trans. and ed. Corinne Bellow (Secaucus, NJ: Chartwell Books, 1964), 101, 274, (repro.), as Jane Avril.

Loan Exhibition: Toulouse-Lautrec, exh. cat. (New York: Wildenstein, 1964), unpaginated, (repro.), as Jane Avril: “La Mélinite”.

Olga Neigemont, Toulouse-Lautrec (Munich: Südwest Verlag, 1966), 35, (repro.), as Jane Avril. Ausschnitt.

François Daulte, French Watercolors of the 20th Century (New York: Viking, 1968), 4, 36–37, (repro.), as Portrait of Jane Avril.

F[ritz] Novotny, Toulouse-Lautrec, trans. Michael Glenney (New York: Phaidon, 1969), 198.

G[abriele] M[andel] Sugana, The Complete Paintings of Toulouse-Lautrec (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1969), no. 334, pp. 108, 126, 128, (repro.), as Jane Avril.

G[abriele] M[andel] Sugana and Giorgio Caproni, Klassiker der Kunst: Das Gesamtwerk von Toulouse-Lautrec (Milan: Rizzoli Editore, 1969), no. 334, pp. 108, 126, 128, (repro.), as Jane Avril betrachtet einen Stich.

Pierre Paret, Lautrec Women (Lausanne, Switzerland: International Art Book, 1970), 23, (repro.), as Jane Avril Looking at a Print.

M.G. Dortu, Toulouse-Lautrec et son œuvre (New York: Collectors Editions, 1971), no. A.206, pp. 1:117, 157, 161–62, 175; 3: 502–03, (repro.), as Jane Avril regardant une épreuve.

Anne Poulet, Faces from the World of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism: A Loan Exhibition for the benefit of The New York Chapter of The Arthritis Foundation, exh. cat. (New York: Wildenstein, 1972), unpaginated, (repro.), as Jane Avril.

James R. Mellow, “Faces From the Impressionists’ World,” New York Times 122, no. 41,923 (November 4, 1972): 29, as Jane Avril.

Possibly Sylvia L. Horwitz, Toulouse-Lautrec: His World (New York: Harper and Row, 1973), 90–91.

G[abriele] M[andel] Sugana, The complete paintings of Toulouse-Lautrec (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1973), no. 334, pp. 108, 126, (repro.), as Jane Avril.

Giorgio Caproni and G[abriele] M[andel] Sugana, L’opera completa di Toulouse-Lautrec (Milan: Rizzoli, 1977), no. 334, pp. 108, 126, 128, (repro.), as Jane Avril osserva un’incisione.

“The Bloch Collection,” Gallery Events (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) (June–August 1982): unpaginated.

Riva Castleman and Wolfgang Wittrock, eds., Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec: Images of the 1890s, exh. cat. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1985), 102–03, (repro.), as Jane Avril Looking at a Proof (Jane Avril regardant une épreuve).

John Russell, “Toulouse-Lautrec At Modern: The Artist As Master Printmaker,” New York Times 135, no. 46,587 (November 8, 1985): C23.

“News of the Print World: People and Places,” Print Collector’s Newsletter 16, no. 5 (November–December 1985): 170.

Wolfgang Wittrock, Toulouse-Lautrec: The complete prints, vol. 1, trans. and ed. Catherine E. Kuehn (London: Sotheby’s, 1985), 56.

Götz Adriani, Toulouse-Lautrec: das gesamte graphische Werk: Sammlung Gerstenberg, exh. cat. (Cologne: Dumont, 1986), 32.

Götz Adriani, Toulouse-Lautrec: The Complete Graphic Works, A Catalogue Raisonné, The Gerstenberg Collection (London: Thames and Hudson, 1988), 32.

Götz Adriani, Toulouse-Lautrec, trans. Anne Lemonnier and Élisabeth Kohler (Paris: Flammarion, 1991), 122.

Blandine Bouret, Claude Bouret, and Anne-Marie Sauvage, eds., Toulouse-Lautrec: Prints and Posters from the Bibliothèque Nationale, exh. cat. (Brisbane, Australia: Queensland Art Gallery, 1991), 144.

Claire Frèches-Thory, Anne Roquebart, and Richard Thomson, Toulouse-Lautrec, exh. cat. (London: South Bank Centre, 1991), 386.

Jürgen Döring, Toulouse-Lautrec und die Belle Époque, exh. cat. (Munich: Prestel, 2002), 14, 121, (repro.), as Jane Avril.

Eileen Chanin and Steven Miller, Degenerates and Perverts: The 1939 Herald Exhibition of French and British Contemporary Art (Melbourne, Australia: Melbourne University Press, 2005), 116, 269, 275–76, 279, (repro.), as Portrait de Jane Avril and Jane Avril. ‘La Mélinite’.

Alice Thorson, “George McKenna was a walking database for Nelson-Atkins Museum,” Kansas City Star (October 7, 2007): H6, as Jane Avril.

Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 10–13, 134–37, 161, (repro.), as Jane Avril Looking at a Proof (Jane Avril regardant une épreuve).

Alice Thorson, “First Public Exhibition-Marion and Henry Bloch’s art collection: A tiny Renoir began impressive obsession Bloch collection gets its first public exhibition-After one misstep, Blochs focused, successfully, on French paintings,” Kansas City Star (June 3, 2007): E4, as Jane Avril.

Alice Thorson, “Museum Review-Bloch Building exhibits,” Kansas City Star (June 10, 2007): G1, as Jane Avril.

“Lasting Impressions: A Tribute to Marion and Henry Bloch,” Member Magazine (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (Fall 2007): 11.

Steve Paul, “Pretty Pictures: Marion and Henry Bloch’s collection of superb Impressionist masters,” Panache 4, no. 3 (Fall 2007): 20–24.

Carol Vogel, “Inside Art: Kansas City Riches,” New York Times 159, no. 54,942 (February 5, 2010): C26.

Thomas M. Bloch, Many Happy Returns: The Story of Henry Bloch, America’s Tax Man (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, 2011), 174–75.

Nancy Ireson, ed., Toulouse-Lautrec and Jane Avril: Beyond the Moulin Rouge, exh. cat. (London: Courtauld Gallery, 2011), 84, (repro.), as Jane Avril looking at a Proof.

Gabriel P. Weisberg, “Review: Toulouse-Lautrec and Jane Avril, Beyond the Moulin Rouge, The Courtauld Gallery, London, June 16–September 18, 2011,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 11, no. 1 (Spring 2012): 136.

Sarah Lees, ed., Nineteenth-Century European Paintings at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, vol. 2 (Williamstown: Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, 2012), 796, 797n5.

Diane Stafford, “Bloch gift to go for Nelson upgrade,” Kansas City Star 135, no. 203 (April 8, 2015): A8.

“Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art officially accessions Bloch Impressionist masterpieces,” Artdaily.org (July 25, 2015): http://artdaily.com/news/80246/Nelson-Atkins-Museum-of-Art-officially-accessions-Bloch-Impressionist-masterpieces#.V6oGwlKFO9I.

Julie Paulais, “Le Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art reçoit des tableaux impressionnistes en échange de leurs répliques,” Le Journal des arts (July 30, 2015): http://www.lejournaldesarts.fr/site/archives/docs_article/129801/le-nelson-atkins-museum-of-art-recoit-des-tableaux-impressionnistes-en-echange-de-leurs-repliques.php.

Josh Niland, “The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Acquires a Renowned Collection of Impressionist and Postimpressionist Art,” architecturaldigest.com (August 6, 2015): https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/nelson-atkins-museum-accessions-bloch-art-collection.

Nancy Staab, “Van Gogh is a Go!” 435: Kansas City’s Magazine (September 2015): 76.

Maria Teresa Benedetti, Toulouse-Lautrec: Luci e ombre di Montmartre, exh. cat. (Milan: Skira editore, 2015), 32, 358.

Possibly Sabine Chaouche and Clara Sadoun-Edouard, eds., European Drama and Performance Studies: Consuming Female Performers (1850s–1950s) (Paris: Classiques Garnier, 2015), 295.

“Nelson-Atkins to unveil renovated Bloch Galleries of European Art in winter 2017,” Artdaily.org (July 20, 2016): http://artdaily.com/news/88852/Nelson-Atkins-to-unveil-renovated-Bloch-Galleries-of-European-Art-in-winter-2017-#.W-NDepNKhaQ.

“Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art celebrates generosity of Henry Bloch with new acquisition,” Artdaily.org (October 18, 2016): http://artdaily.com/news/90923/Nelson-Atkins-Museum-of-Art-celebrates-generosity-of-Henry-Bloch-with-new-acquisition#.W-NDv5NKhaQ.

Catherine Futter et al., Bloch Galleries: Highlights from the Collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2016), 114, (repro.), as Jane Avril Looking at a Proof.

Albert Hect, “Henry Bloch’s Masterpieces Collection to Go on Display at Nelson-Atkins Museum,” Jewish Business News (February 26, 2017): http://jewishbusinessnews.com/2017/02/26/henry-bloch-masterpieces-collection/.

David Frese, “Inside the Bloch Galleries: An interactive experience,” Kansas City Star 137, no. 169 (March 5, 2017): 1D, 5D, (repro.), as Jane Avril Looking at a Proof.

“The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: Presenting the Bloch Galleries,” New York Times (March 5, 2017).

“Editorial: Thank you, Henry and Marion Bloch”, Kansas City Star (March 7, 2017): http://www.kansascity.com/opinion/editorials/article137040948.html.

Hampton Stevens, “(Not Actually) 12 Things To Do During The Big 12 Tournament,” Flatland: KCPT’s Digital Magazine (March 9, 2017): http://www.flatlandkc.org/arts-culture/sports/not-actually-12-big-12-tournament/.

Laura Spencer, “The Nelson-Atkins’ Bloch Galleries feature Old Masterworks and New Technology,” KCUR (March 10, 2017): http://kcur.org/post/nelson-atkins-bloch-galleries-feature-old-masterworks-and-new-technology#stream/0.

Victoria Stapley-Brown, “Nelson-Atkins Museum’s new European art galleries come with a “love story”,” Art Newspaper (March 10, 2017): http://theartnewspaper.com/news/museums/nelson-atkins-museum-s-new-european-art-galleries-come-with-a-love-story/.

Harry Bellet, “Don du ciel pour le Musée Nelson-Atkins,” Le Monde (March 13, 2017): http://www.lemonde.fr/arts/article/2017/03/13/don-du-ciel-pour-le-musee-nelson-atkins_5093543_1655012.html.

Menachem Wecker, “Jewish Philanthropist Establishes Kansas City as Cultural Mecca,” The Forward (March 14, 2017): http://forward.com/culture/365264/jewish-philanthropist-establishes-kansas-city-as-cultural-mecca/ [repr. in Menachem Wecker, “Kansas City Collection Is A Chip Off the Old Bloch,” Forward (March 17, 2017): 20–22].

Juliet Helmke, “The Bloch Collection Takes up Residence in Kansas City’s Nelson Atkins Museum,” BlouinArtInfo International (March 15, 2017): http://www.blouinartinfo.com/news/story/2005267/the-bloch-collection-takes-up-residence-in-kansas-citys.

Erich Hatala Matthes, “Digital replicas are not soulless – they help us engage with art,” Apollo: The International Art Magazine (March 23, 2017): https://www.apollo-magazine.com/digital-replicas-3d-printing-original-artworks/.

Louise Nicholson, “How Kansas City got its magnificent museum,” Apollo (April 7, 2017): https://www.apollo-magazine.com/how-kansas-city-got-its-magnificent-museum/.

Lilly Wei, “Julián Zugazagoitia: ‘Museums should generate interest and open a door that leads to further learning,’” Studio International (August 21, 2017): http://studiointernational.com/index.php/julian-zugazagoitia-director-nelson-atkins-museum-of-art-kansas-city-interview.

Robert D. Hershey Jr., “Henry Bloch, H&R Block’s cofounder, dies at 96,” Boston Globe (April 23, 2019), https://www3.bostonglobe.com/metro/obituaries/2019/04/23/henry-bloch-block-cofounder/?arc404=true[.]{.underline}

Robert D. Hershey Jr., “Henry W. Bloch, Tax-Preparation Pioneer (and Pitchman), Is Dead at 96,” New York Times (April 23, 2019), https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/23/obituaries/henry-w-bloch-dead.html.

Claire Selvin, “Henry Wollman Bloch, Collector and Prominent Benefactor of Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Is Dead at 96,” ArtNews (April 23, 2019): http://www.artnews.com/2019/04/23/henry-bloch-dead-96/.

“Henry Wollman Bloch (1922-2019),” Art Forum (April 24, 2019): https://www.artforum.com/news/henry-wollman-bloch-1922-2019-79547.

Frank Morris, “Henry Bloch, Co-Founder Of H&R Block, Dies At 96,” npr.org (April 24, 2019): https://www.npr.org/2019/04/24/716641448/henry-bloch-co-founder-of-h-r-block-dies-at-96.

Ignacio Villarreal, “Nelson-Atkins mourns loss of Henry Bloch,” Artdaily.org (April 24, 2019): http://artdaily.com/index.asp?int_sec=11&int_new=113035#.XMNtouhKhaQ.

Helen Burnham, Toulouse-Lautrec and the Stars of Paris, exh. cat. (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 2019), 40–41, 107, (repro.), as Jane Avril Looking at a Proof.

Toulouse-Lautrec et son œuvre. Supplément (Albi, France: Musée Toulouse-Lautrec, forthcoming).