![]()

Paul Signac, Portrieux, The Bathing Cabins, Opus 185 (Beach of the Countess), 1888

| Artist | Paul Signac, French, 1863–1935 |

| Title | Portrieux, The Bathing Cabins, Opus 185 (Beach of the Countess) |

| Object Date | 1888 |

| Alternate and Variant Titles | La Mer – De Portrieux (Côtes-du-Nord), juin, juillet, août, septembre 1888; Portrieux, Les cabinés, Opus 185 (Plage de la comtesse) |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (Unframed) | 13 1/8 x 18 1/4 in. (33.3 x 46.4 cm) |

| Signature | Signed and dated lower left: P. Signac. 88 |

| Credit Line | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Gift of Henry W. and Marion H. Bloch, 2015.13.23 |

| Copyright | © 2023 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Paul Signac, Portrieux, The Bathing Cabins, Opus 185 (Beach of the Countess), 1888,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.730.5407.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Paul Signac, Portrieux, The Bathing Cabins, Opus 185 (Beach of the Countess), 1888,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.730.5407.

The town of Portrieux was in a state of flux when Paul Signac, a Neo-ImpressionistNeo-Impressionism: A term coined in 1886 by French art critic Félix Fénéon to describe a style of painting pioneered by Georges Seurat. He and his followers espoused a scientific approach to color and a painting technique known as pointillism. painter in the first decade of his career, arrived there in July 1888. For centuries, life in this quiet Breton village had revolved around deep-sea fishing—not, as one might suppose, in the nearby Bay of Saint-Brieuc, but rather off the coast of Newfoundland in present-day Canadian waters. Each year, beginning in 1664, Portrieux and many other French ports sent hundreds of men across the Atlantic to fish for cod from May to October. When the fishermen returned to France, they would sell their annual hauls in La Rochelle, Bordeaux, and Marseille, as well as some Spanish and Italian towns.1For an excellent account of this industry, see Bernard Corbel, Saint-Quay-Portrieux: Enjeu maritime aux XVIIIe et XIXe siècles (Saint-Brieuc: Presses Bretonnes, 1993), 39–48, 124–42. The fishermen used salt to cure and preserve the cod for later consumption. Their families eagerly awaited these homecomings, as seen in an 1875 painting of Portrieux by Eugène Boudin (1824–98) (Fig. 1).2Boudin visited Portrieux repeatedly between 1870 and 1879, producing more than sixty paintings of the town. See Corbel, Saint-Quay-Portrieux, 322. Figure 1 is inscribed “Portrieux” in the lower left corner. Men, women, and children are gathered around a beached terre-neuvierterre-neuvier: The French term for a vessel used for cod fishing off the coast of Newfoundland., some unloading crates and others simply watching the bustle of activity. However, Portrieux’s economy was already beginning to change drastically when Boudin captured this scene. During the last quarter of the nineteenth century, cod fishing declined in popularity as other industries, particularly tourism and oyster farming, became more lucrative and offered residents a less itinerant lifestyle. By the time of Signac’s sojourn, two major hotels had been built in Portrieux to entice would-be visitors, signaling that this societal shift was well underway.3The Hôtel du Talus and Hôtel de la Plage opened in 1860 and 1877, respectively. They were soon followed by the Hôtel du Mouton Blanc in 1890. See Corbel, Saint-Quay-Portrieux, 318; and Arnaud Collin, Saint-Quay-Portrieux: Mémoire en images (Saint-Cyr-sur-Loire, France: Éditions Alan Sutton, 2008–2009), 2:12, 2:21.

During Signac’s three-month stay on the Breton coast, he produced a total of fifteen oil paintings: six studies on panel and nine finished works on canvas. The latter all received opus numbers, akin to musical compositions, something Signac had introduced the previous year.10For a complete inventory of Signac’s paintings with opus numbers, see Marianne Jakobi, Gauguin-Signac: La genèse du titre contemporain (Paris: CNRS Éditions, 2015), 251–74. As Peter Flagg has noted, the town of Portrieux itself is virtually absent from this series. Signac was wholly absorbed in the port and its environs.11Peter J. Flagg, “The Neo-Impressionist Landscape” (PhD diss., Princeton University, 1988), 131. His paintings depict the octagonal lighthouse, built in 1867; the jetty, greatly expanded in 1876; the ships anchored in the Bay of Saint-Brieuc; and the sandy beach known as the Plage de la Comtesse. The beach appears in two of the opus-numbered pictures: the Nelson-Atkins work and another painting in private hands (Fig. 2).12The latter surfaced at auction in 2018. See The Collection of Peggy and David Rockefeller, vol. 1, 19th and 20th Century Art Evening Sale (New York: Christie’s, May 8, 2018), lot 21, Portrieux, La Comtesse (Opus no. 191). It is likely that Signac worked on these beachscapes simultaneously, because he told Camille Pissarro (1830–1903) in a letter dated August 24, 1888: “I have eight canvases started and not a single one finished!”13Signac to Pissarro, August 24, 1888, Archives de Camille Pissarro (Paris: Hotel Drouot, November 21, 1975), unpaginated, lot 179. “J’ai 8 toiles commencées et pas une seule finie!” All translations are by Brigid M. Boyle. For both beach scenes, Signac painted preparatory oil sketches, similar in size and purpose to the croquetonscroquetons: Georges Seurat’s term, derived from the French word croquis (sketch), for his small oil sketches on panel. They were easily transported, making them ideal for painting outdoors. of his colleague Georges Seurat (1859–91).14The Nelson-Atkins has two examples of Seurat’s croquetons: Study for “Bathers at Asnières,” 1883; and Study for “The Channel of Gravelines, Petit Fort Philippe,” 1890. Signac would later shed this habit and renounce painting from nature. In a journal entry dated September 15, 1902, he wrote: “Peindre d’après nature n’est-ce pas une espèce de servilité; un manque de pouvoir créateur?” (Is not painting after nature a form of servile copycatting; a lack of creative power?) Paul Signac, Journal: 1894–1909, ed. Charlotte Hellman (Paris: Gallimard, 2021), 525. Signac’s study for Portrieux, The Bathing Cabins, Opus 185 (Beach of the Countess) is compositionally close to the finished painting but seems to have been executed under different lighting conditions (Fig. 3). The dramatic shadows from the cabins, so central to the Nelson-Atkins picture, are absent in the study, suggesting an overcast day.

Fig. 2. Paul Signac, Portrieux, Beach of the Countess, Opus 191, 1888, oil on canvas, 23 3/4 x 36 1/4 in. (60.3 x 92.1 cm), private collection. © 2023 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photograph © Private Collection/Bridgeman Images

Fig. 2. Paul Signac, Portrieux, Beach of the Countess, Opus 191, 1888, oil on canvas, 23 3/4 x 36 1/4 in. (60.3 x 92.1 cm), private collection. © 2023 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photograph © Private Collection/Bridgeman Images

Fig. 3. Paul Signac, Portrieux, Beach of the Countess (Study), 1888, oil on panel, 6 1/8 x 9 3/4 in. (15.5 x 24.8 cm), private collection, reproduced in Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 110. © 2023 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Fig. 3. Paul Signac, Portrieux, Beach of the Countess (Study), 1888, oil on panel, 6 1/8 x 9 3/4 in. (15.5 x 24.8 cm), private collection, reproduced in Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 110. © 2023 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

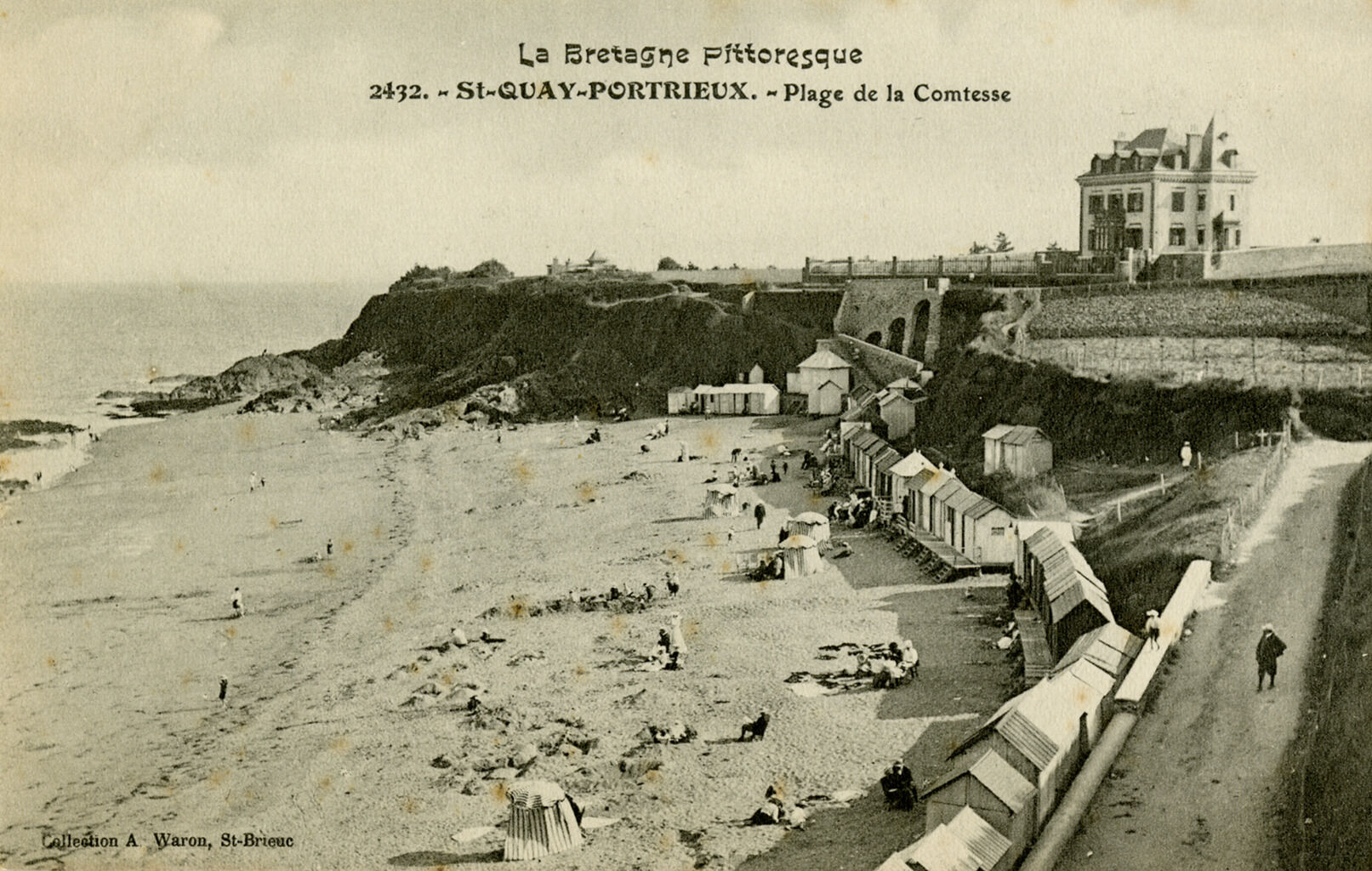

Some bathing cabins were available for short-term rentals by tourists. According to a 1908 guidebook, they generally cost one franc per day.18Paul Joanne, Bretagne: Les routes les plus fréquentées (Paris: Librairie Hachette, 1908), 32. For comparison, hotel rates in Portrieux averaged five to seven francs per day. See Corbel, Saint-Quay-Portrieux, 318; and Collin, Saint-Quay-Portrieux, 2:12. Whether Signac, Roblès, or Ajalbert availed themselves of this opportunity in 1888 is unknown, but Signac certainly found the cabins interesting as motifs. In the Kansas City picture, he rendered them with touches of blue, orange, cream, and occasionally purple pigment. Long, geometric shadows amplify the cabins’ presence within the scene. Richard Brettell, noting the absence of people, assumed that Signac must have risen early to paint the Plage de la Comtesse while it was empty,19For Brettell’s interpretation, see Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 111. but three current residents have independently identified the time of day as mid- to late afternoon, based on the cabins’ shadows.20I am grateful to Florence Lévêque, Office de Tourisme de Saint-Quay-Portrieux; Véronique Lacour, Les Amis de Saint-Quay-Portrieux; and Mathieu Petitjean, author of Saint-Quay-Portrieux: À l’abri de la ronce bénie (Saint-Jacut-de-la-Mer, France: Jean-Pierre Bihr, 1998), for their helpful comments about the shadows. Nearly identical shadows can be seen in an early twentieth-century postcard of the Plage de la Comtesse by Breton photographer Armand Waron (1868–1956) (Fig. 4). Waron captured the beach from a more elevated position but facing the same direction as Signac. Some two dozen figures are scattered across the shore, including several adults lounging on the cabins’ wooden decks and a group of children building a sandcastle.

After Signac left Portrieux in late September 1888, he began making plans to exhibit his finished works. Within two years, all nine of the opus-numbered paintings had been publicly displayed, some multiple times.24Signac exhibited two paintings of Portrieux at the Cinquième exposition de la Société des Artistes Indépendants, Paris, September 3–October 4, 1889; seven at Les XX: XVIe exposition annuelle, Brussels, January 18–February 23, 1890; four at the Sixième exposition de la Société des Artistes Indépendants, Paris, March 20–April 27, 1890; and one at the Théâtre Libre, Paris, for a period of about ten years (1888–98). The Nelson-Atkins picture made its debut in 1890 at the sixth annual exhibition of the Société des Artistes IndépendantsSociété des Artistes Indépendants: A group founded in 1884 in Paris by Odilon Redon, Albert Dubois-Pillet, Georges Seurat, and Paul Signac that created the Salon des Indépendants as an alternative to exhibiting at the Salon organized and juried by the French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture (Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture). The Salon des Indépendants has no selection committee; instead, artists can exhibit on payment of a fee. The exhibitions became the main venue for many artists, particularly the Post-Impressionists in the late nineteenth century. The Salon des Indépendants is still in existence today. See also Salon, the., an organization that Signac had helped found in 1884. Reviews were decidedly mixed. Some commentators praised Signac’s methodical approach to color and his ability to capture both “the diaphanous depths of an azure sky” and the placid, “immensely flat” sea.25See Jules Christophe, “Causerie: L’Impressionnisme; L’exposition des artistes indépendants,” Journal des artistes, no. 13 (April 6, 1890): 102; and Georges Lecomte, “Beaux-Arts: L’Exposition des néo-impressionnistes, Pavillon de la ville de Paris (Champs-Elysées),” Art et critique 2, no. 44 (March 29, 1890): 204. Lecomte lauded Signac’s rendering of les profondeurs diaphanes d’un ciel azur” and the “immensément plane” sea. Others found his pointillistpointillism: A technique of painting using tiny dots of pure colors, which when seen from a distance are blended by the viewer’s eye. It was developed by French Neo-Impressionist painters in the mid-1880s as a means of producing luminous effects. technique and repetition of motifs stultifying. The harshest critique came from Julien Leclercq:

Signac really bores us. No personality. Dots, dots, nothing but dots. . . . And his seascapes—his seascape, we mean to say, because it’s always the same! With Monet, when we encounter the same tree, the same cliff, or the same rock in ten paintings, we appreciate it; with Signac, we wonder: [is this] some punishment imposed by Seurat?26J[ulien] L[eclercq], “Beaux-arts: Aux Indépendants,” Mercure de France 1, no. 5 (May 1890): 175. “Signac nous ennuie bien. Aucune personnalité. Des points, des points, et c’est tout. . . . Et ses marines, sa marine voulons-nous dire, car c’est toujours la même! Chez Monet, lorsqu’en dix tableaux nous retrouvons le même arbre ou la même falaise, le même rocher, nous le sentons; chez Signac, nous nous le demandons: quelque pensum infligé par Seurat.” The latter remark positions Signac as a disciple of Seurat, whose pointillist technique and ideas about color theory strongly influenced him in the mid-1880s.

Leclercq’s unfavorable comparison of Signac with his predecessor Claude Monet (1840–1926) is not without irony, for it was Monet who had inspired Signac’s choice of profession and to whom Signac later paid homage in his book D’Eugène Delacroix au néo-impressionnisme (From Eugène Delacroix to Neo-Impressionism; 1899).27Signac decided to become a painter after attending Monet’s first solo exhibition in 1880. The two artists were in periodic contact for more than four decades, and Monet even visited Signac in Les Andelys in September 1921. See Ferretti-Bocquillon et al., Signac, 69, 317. Leclerq’s dismissive attitude toward Signac’s technique was certainly not shared by all observers. When Signac gave Ajalbert a preview of his Portrieux paintings toward the end of their joint summer vacation, the latter reacted with awe: “Signac showed me his canvases. He works methodically, in small dots. How many per hour? One thousand, two thousand!”28Ajalbert, Mémoires en vrac, 371. “Il travaille méthodiquement, au petit point. Combien à l’heure? Cent mille, deux mille!” Emphasis in the original. Unlike Leclercq, Ajalbert recognized that few artists possessed the patience or tenacity for so painstaking a method.

Created during the first decade of Signac’s career, Portrieux, The Bathing Cabins, Opus 185 is a small but important seascape. On a local level, it bears witness to a transitional moment in Portrieux’s history, when tourism began to overtake deep-sea fishing as an economic driver. In personal terms, it reflects Signac’s love of travel, his deep attachment to the sea, and his anarchist sympathies. The late-afternoon shadows reflect Signac’s keen observational skills, but, at the same time, the unoccupied beach demonstrates his willingness to deviate from reality when it suited his aesthetic or political aims. Over the next forty-odd years, Signac would explore countless other ports, producing hundreds of oils and watercolors of the French waterfront, a perennially favorite theme.29By one scholar’s tally, 484 of Signac’s 611 documented oil paintings depict water. See Marina Ferretti Bocquillon, “Signac, la mer toujours recommencée,” in Marina Ferretti Bocquillon and Pierre Curie, eds., Signac: Les harmonies colorées, exh. cat. (Brussels: Fonds Mercator, 2021), 24–37, at 27.

Notes

-

For an excellent account of this industry, see Bernard Corbel, Saint-Quay-Portrieux: Enjeu maritime aux XVIIIe et XIXe siècles (Saint-Brieuc: Presses Bretonnes, 1993), 39–48, 124–42. The fishermen used salt to cure and preserve the cod for later consumption.

-

Boudin visited Portrieux repeatedly between 1870 and 1879, producing more than sixty paintings of the town. See Corbel, Saint-Quay-Portrieux, 322. Figure 1 is inscribed “Portrieux” in the lower left corner.

-

The Hôtel du Talus and Hôtel de la Plage opened in 1860 and 1877, respectively. They were soon followed by the Hôtel du Mouton Blanc in 1890. See Corbel, Saint-Quay-Portrieux, 318; and Arnaud Collin, Saint-Quay-Portrieux: Mémoire en images (Saint-Cyr-sur-Loire, France: Éditions Alan Sutton, 2008–2009), 2:12, 2:21.

-

Signac met Roblès in 1882. She modeled for many of his early figure paintings. See Marina Ferretti-Bocquillon et al., Signac: 1863–1935, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2001), 92.

-

Like many Neo-Impressionist painters, Signac sympathized with the left-wing political philosophy known as anarcho-communism and befriended some of its leading proponents, including Jean Grave, Émile Pouget, and Élisée Reclus. See Robert L. and Eugenia W. Herbert, “Artists and Anarchism: Unpublished Letters of Pissarro, Signac and Others: I,” Burlington Magazine 102, no. 692 (November 1960): 472–82.

-

For Ajalbert’s description of their accommodations, see Jean Ajalbert, “Un demi-siècle d’art indépendant,” Les Nouvelles littéraires, no. 591 (February 10, 1934): 4.

-

Signac was his father’s sole heir. Ferretti-Bocquillon et al., Signac, 84, 298.

-

It was not until 1905 that the Paris-Saint-Brieuc line was extended north to Plouha, with a stop at Portrieux’s sister village, Saint-Quay. Corbel, Saint-Quay-Portrieux, 322; and Collin, Saint-Quay-Portrieux, 1:81. Portrieux and Saint-Quay officially merged in 1921 to form what is now known as Saint-Quay-Portrieux.

-

Ajalbert, “Un demi-siècle d’art indépendant,” 4; and Jean Ajalbert, Mémoires en vrac: Au temps du symbolisme, 1880–1890 (Paris: Albin Michel, 1938), 371.

-

For a complete inventory of Signac’s paintings with opus numbers, see Marianne Jakobi, Gauguin-Signac: La genèse du titre contemporain (Paris: CNRS Éditions, 2015), 251–74.

-

Peter J. Flagg, “The Neo-Impressionist Landscape” (PhD diss., Princeton University, 1988), 131.

-

The latter surfaced at auction in 2018. See The Collection of Peggy and David Rockefeller, vol. 1, 19th and 20th Century Art Evening Sale (New York: Christie’s, May 8, 2018), lot 21, Portrieux, La Comtesse (Opus no. 191).

-

Signac to Pissarro, August 24, 1888, Archives de Camille Pissarro (Paris: Hotel Drouot, November 21, 1975), unpaginated, lot 179. “J’ai 8 toiles commencées et pas une seule finie!” All translations are by Brigid M. Boyle.

-

The Nelson-Atkins has two examples of Seurat’s croquetons: Study for “Bathers at Asnières,” 1883; and Study for “The Channel of Gravelines, Petit Fort Philippe,” 1890. Signac would later shed this habit and renounce painting from nature. In a journal entry dated September 15, 1902, he wrote: “Peindre d’après nature n’est-ce pas une espèce de servilité; un manque de pouvoir créateur?” (Is not painting after nature a form of servile copycatting; a lack of creative power?) Paul Signac, Journal: 1894–1909, ed. Charlotte Hellman (Paris: Gallimard, 2021), 525.

-

Some people mistakenly believe that the beach and island were named for another countess, Julie Tranchant des Tulayes, who purchased the Île de la Comtesse in 1832, but archival records confirm that the name long predates her period of ownership. See Collin, Saint-Quay-Portrieux, 2:111.

-

The latter view was greatly altered in 1990, when the town of Saint-Quay-Portrieux installed a seventeen-hectare marina at the southern end of the Plage de la Comtesse. I thank Florence Lévêque, Office de Tourisme de Saint-Quay-Portrieux, for this information.

-

For this history and anecdote, see Corbel, Saint-Quay-Portrieux, 267, 285; and Collin, Saint-Quay-Portrieux, 2:61.

-

Paul Joanne, Bretagne: Les routes les plus fréquentées (Paris: Librairie Hachette, 1908), 32. For comparison, hotel rates in Portrieux averaged five to seven francs per day. See Corbel, Saint-Quay-Portrieux, 318; and Collin, Saint-Quay-Portrieux, 2:12.

-

For Brettell’s interpretation, see Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 111.

-

I am grateful to Florence Lévêque, Office de Tourisme de Saint-Quay-Portrieux; Véronique Lacour, Les Amis de Saint-Quay-Portrieux; and Mathieu Petitjean, author of Saint-Quay-Portrieux: À l’abri de la ronce bénie (Saint-Jacut-de-la-Mer, France: Jean-Pierre Bihr, 1998), for their helpful comments about the shadows.

-

The lone exception is Paul Signac, Portrieux, The Port (Study), 1888, oil on panel, 5 7/8 x 9 13/16 in. (15 x 25 cm), Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge, PD.9-1959.

-

Robyn Roslak, Neo-Impressionism and Anarchism in Fin-de-Siècle France: Paintings, Politics, and Landscape (Aldershot, England: Ashgate, 2007), 7, 155. See also Roslak’s discussion of water as an anarchist metaphor for social harmony in Signac’s marine paintings, in Robyn Roslak, “Symphonic Seas, Oceans of Liberty: Paul Signac’s La Mer: Les Barques (Concarneau),” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 4, no. 1 (Spring 2005): http://19thc-artworldwide.org/index.php/component/content/article/64-spring05article/302-symphonic-seas-oceans-of-liberty-paul-signacs-la-mer-les-barques-concarneau.

-

In 1892, Signac followed the lead of his colleague and fellow anarchist Henri Edmond Cross (1856–1910) in relocating to the south of France. Cross had moved from Paris to Cabasson the previous year, and his rhapsodic descriptions of the town’s scenery and climate convinced Signac to make a similar leap. He set his sights on Saint-Tropez, initially renting a villa and later purchasing property there in 1897. For both Cross and Signac, their choice of the Mediterranean coast was motivated, in part, by their politics. Reclus and others characterized this area as “well-suited to the dream of an anarchist utopia” in their writings, praising its ample sunshine, access to the sea, and pre-modern character; see Roslak, Neo-Impressionism and Anarchism in Fin-de-Siècle France, 145–47. This rhetoric persuaded Cross, Signac, and other Neo-Impressionists to explore Provence, with many of them settling there long-term.

-

Signac exhibited two paintings of Portrieux at the Cinquième exposition de la Société des Artistes Indépendants, Paris, September 3–October 4, 1889; seven at Les XX: XVIe exposition annuelle, Brussels, January 18–February 23, 1890; four at the Sixième exposition de la Société des Artistes Indépendants, Paris, March 20–April 27, 1890; and one at the Théâtre Libre, Paris, for a period of about ten years (1888–98).

-

See Jules Christophe, “Causerie: L’Impressionnisme; L’exposition des artistes indépendants,” Journal des artistes, no. 13 (April 6, 1890): 102; and Georges Lecomte, “Beaux-Arts: L’Exposition des néo-impressionnistes, Pavillon de la ville de Paris (Champs-Elysées),” Art et critique 2, no. 44 (March 29, 1890): 204. Lecomte lauded Signac’s rendering of “les profondeurs diaphanes d’un ciel azur” and the “immensément plane” sea.

-

J[ulien] L[eclercq], “Beaux-arts: Aux Indépendants,” Mercure de France 1, no. 5 (May 1890): 175. “Signac nous ennuie bien. Aucune personnalité. Des points, des points, et c’est tout. . . . Et ses marines, sa marine voulons-nous dire, car c’est toujours la même! Chez Monet, lorsqu’en dix tableaux nous retrouvons le même arbre ou la même falaise, le même rocher, nous le sentons; chez Signac, nous nous le demandons: quelque pensum infligé par Seurat.” The latter remark positions Signac as a disciple of Seurat, whose pointillist technique and ideas about color theory strongly influenced him in the mid-1880s.

-

Signac decided to become a painter after attending Monet’s first solo exhibition in 1880. The two artists were in periodic contact for more than four decades, and Monet even visited Signac in Les Andelys in September 1921. See Ferretti-Bocquillon et al., Signac, 69, 317.

-

Ajalbert, Mémoires en vrac, 371. “Il travaille méthodiquement, au petit point. Combien à l’heure? Cent mille, deux mille!” Emphasis in the original.

-

By one scholar’s tally, 484 of Signac’s 611 documented oil paintings depict water. See Marina Ferretti Bocquillon, “Signac, la mer toujours recommencée,” in Marina Ferretti Bocquillon and Pierre Curie, eds., Signac: Les harmonies colorées, exh. cat. (Brussels: Fonds Mercator, 2021), 24–37, at 27.

Technical Entry

Technical entry forthcoming.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Paul Signac, Portrieux, The Bathing Cabins, Opus 185 (Beach of the Countess), 1888,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.730.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Paul Signac, Portrieux, The Bathing Cabins, Opus 185 (Beach of the Countess), 1888,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.730.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Paul Signac, Portrieux, The Bathing Cabins, Opus 185 (Beach of the Countess), 1888,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.730.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Paul Signac, Portrieux, The Bathing Cabins, Opus 185 (Beach of the Countess), 1888,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.730.4033.

Paul Signac (1863–1935), Paris, 1888–no later than 1902;

Given by the artist to Paul Merme, Paris, by 1902 [1];

Dikran Garabed Kelekian (1868–1951), Paris and New York, by September 6, 1930–January 18, 1935 [2];

Purchased at his sale, Paintings, Watercolors, and Drawings of the Moderns: The Private Collection of Dikran G. Kelekian, Rains Galleries, New York, January 18, 1935, lot 36, as The Seashore [3];

Mollie Bragno (née Netcher, 1923–2002), Chicago [4];

With Richard L. Feigen and Co., Chicago, as La Plage, by 1959 [5];

Purchased from Feigen by Jerome Kane Ohrbach (1908–90), Los Angeles, 1959–June 28, 1990 [6];

Jerome K. Ohrbach Trust, 1990–November 8, 1994 [7];

Purchased from the Ohrbach Trust, through Richard L. Feigen and Co., New York, by Marion (née Helzberg, 1931–2013) and Henry (1922–2019) Bloch, Shawnee Mission, KS, November 8, 1994–June 15, 2015;

Their gift to The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 2015.

Notes

[1] During Signac’s lifetime, he created three chronological lists of his paintings: the cahier d’opus (compiled 1887–1902); the cahier manuscript (compiled 1902–1909); and the pré-catalogue (compiled 1929–1932). All three inventories mention a collector named Merme in connection with Portrieux, The Bathing Cabins, Opus 185 (Beach of the Countess). The cahier d’opus states that the painting was “offert à P. Merme” (given to P. Merme), indicating that this transaction must have taken place prior to 1902. The cahier manuscript and pré-catalogue both list “Merme” next to or beneath the painting’s title. See Archives Paul Signac, Paris.

Françoise Cachin identified this individual as “Paul Merme, Paris”; see Françoise Cachin, Signac: Catalogue raisonné de l’œuvre peint (Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 2000), no. 169, p. 188. Several people with this first and last name are known; one likely candidate is Paul Félix Merme (1847–1915), Inspecteur des services administratives et financiers de la marine et des colonies, but it has not been possible to confirm this connection.

[2] The painting belonged to Kelekian by 1930 because he lent it to the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, for the exhibition Vincent van Gogh en zijn tijdgenoten (September 6–November 2, 1930). His descendants have no information about when he acquired the landscape or to whom he sold it in 1935; see letter from Françoise Cachin to Charles D. Kelekian, May 21, 1984, and letter from Nanette B. Kelekian to Françoise Cachin, May 29, 1984, Archives Paul Signac, Paris, copies in NAMA curatorial files.

[3] Founded by Samuel G. Rains (1872–1931), Rains Galleries was active from 1922 to 1937. Its records have not been located and are presumed lost. Multiple copies of the Rains Galleries sale catalogue are annotated with the purchase price, but none of them record the buyer’s name.

[4] Married three times over the course of her life, Bragno died single and childless. Her parents, Charles Netcher Jr. (1892–1931) and Gladys Netcher (née Oliver, 1892–1947), collected art and donated certain objects to the Art Institute of Chicago, but there is no evidence that they owned Portrieux, The Bathing Cabins, Opus 185 prior to their daughter. Bragno’s living relatives have no information about her collection. See email from Maria Stave, niece of Mollie Bragno, to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, August 9, 2022, NAMA curatorial files.

[5] Encapsulated on the backing board is a Richard L. Feigen and Co. label for “Paul Signac, La Plage, 1888” bearing the address “1444 Astor Street, Chicago 10, Illinois.” No stock number is listed for the painting. Feigen opened his Chicago gallery in 1957, so he must have acquired Portrieux, The Bathing Cabins, Opus 185 between 1957 and 1959.

[6] For the year of acquisition, see The Collection of Jerome K. Ohrbach (New York: Sotheby’s, November 13, 1990), lot 10. Richard L. Feigen and Co. was unable to confirm their exact date of sale to Ohrbach in 1959. See emails between Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, and Cynthia Conti, Richard L. Feigen and Co., August 9–10, 2022, NAMA curatorial files.

[7] This painting was offered for sale by the Jerome K. Ohrbach Trust at The Collection of Jerome K. Ohrbach, Sotheby’s, New York, November 13, 1990, lot 10, but failed to sell. The Ohrbach Trust subsequently placed the painting on consignment with Richard L. Feigen and Co. from December 3, 1993 to November 8, 1994. To our knowledge, Sotheby’s did not have a part interest in the painting’s eventual sale. See email from Emelia Scheidt, Richard L. Feigen and Co., to Meghan Gray, NAMA, April 13, 2015, and email from Cynthia Conti, Richard L. Feigen and Co., to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, August 16, 2022, NAMA curatorial files.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Paul Signac, Portrieux, The Bathing Cabins, Opus 185 (Beach of the Countess), 1888,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.730.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Paul Signac, Portrieux, The Bathing Cabins, Opus 185 (Beach of the Countess), 1888,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.730.4033.

Paul Signac, Portrieux, The Jetty, Gray Weather, Opus 180, 1888, oil on canvas, 18 1/8 x 25 9/16 in. (46 x 65 cm), Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, The Netherlands, KM 108.323.

Paul Signac, Portrieux, Gouverlo, Opus 181, 1888, oil on canvas, 18 3/16 x 21 7/8 in. (46.2 x 55.5 cm), Hiroshima Museum of Art.

Paul Signac, Portrieux, Masts, Opus 182, 1888, oil on canvas, 18 1/8 x 25 9/16 in. (46 x 65 cm), whereabouts unknown, illustrated in Paul Signac (New York: Parkstone Press International, 2013), unpaginated.

Paul Signac, Portrieux, The Lighthouse, Opus 183, 1888, oil on canvas, 18 1/8 x 25 9/16 in. (46 x 65 cm), Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, The Netherlands, KM 104.721.

Paul Signac, Portrieux, The Port, Setting Sun, Opus 184, 1888, oil on canvas, 13 x 18 1/8 in. (33 x 46 cm), whereabouts unknown, illustrated in Françoise Cachin, Signac: Catalogue raisonné de l’œuvre peint (Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 2000), no. 168, p. 188.

Paul Signac, Portrieux, Tertre Denis, Opus 189, 1888, oil on canvas, 25 9/16 x 31 7/8 in. (65 x 81 cm), The Phillips Family Collection, United States.

Paul Signac, Portrieux, The Swell, Opus 190, 1888, oil on canvas, 24 x 36 1/4 in. (61 x 92 cm), Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, Inv. Nr. 2698.

Paul Signac, Portrieux, The Port (study), 1888, oil on panel, 5 7/8 x 9 13/16 in. (15 x 25 cm), whereabouts unknown, illustrated in Françoise Cachin, Signac: Catalogue raisonné de l’œuvre peint (Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 2000), no. 173, p. 189.

Paul Signac, Portrieux, The Port (study), 1888, oil on panel, 5 7/8 x 9 13/16 in. (15 x 25 cm), The Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge, PD.9-1959.

Paul Signac, Portrieux, The Port (study), 1888, oil on panel, 6 5/16 x 9 7/16 in. (16 x 24 cm), whereabouts unknown, illustrated in Françoise Cachin, Signac: Catalogue raisonné de l’œuvre peint (Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 2000), no. 175, p. 190.

Paul Signac, Portrieux, The Port (study), 1888, oil on panel, 5 7/8 x 9 13/16 in. (15 x 25 cm), private collection, Paris.

Paul Signac, Portrieux, The Countess, Opus 191, 1888, oil on canvas, 23 3/4 x 36 1/4 in. (60.3 x 92.1 cm), whereabouts unknown, illustrated in The Collection of Peggy and David Rockefeller, vol. 1, 19th and 20th Century Art Evening Sale (New York: Christie’s, May 8, 2018), 161–62.

Paul Signac, Portrieux, The Countess (study), 1888, oil on panel, 5 7/8 x 9 13/16 in. (15 x 25 cm), whereabouts unknown, illustrated in Françoise Cachin, Signac: Catalogue raisonné de l’œuvre peint (Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 2000), no. 178, p. 190.

Preparatory Work

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Paul Signac, Portrieux, The Bathing Cabins, Opus 185 (Beach of the Countess), 1888,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.730.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Paul Signac, Portrieux, The Bathing Cabins, Opus 185 (Beach of the Countess), 1888,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.730.4033. s

Paul Signac, Portrieux, The Countess (study), 1888, oil on panel, 6 1/8 x 9 3/4 in. (15.5 x 24.8 cm), whereabouts unknown, illustrated in Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 110.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Paul Signac, Portrieux, The Bathing Cabins, Opus 185 (Beach of the Countess), 1888,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.730.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Paul Signac, Portrieux, The Bathing Cabins, Opus 185 (Beach of the Countess), 1888,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.730.4033. s

Sixième exposition de la Société des Artistes indépendants, Pavillon de la Ville de Paris, March 20–April 27, 1890, no. 741, as La mer—De Portrieux (Côtes-du-Nord), juin, juillet, août, septembre 1888, Op. 185.

Vincent van Gogh en zijn tijdgenoten, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, September 6–November 2, 1930, no. 280, as Het strand.

Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, June 9–September 9, 2007, no. 20, as Portrieux, The Bathing Cabins, Opus 185 (Beach of the Countess) (Portrieux, les cabines, Opus 185 [Plage de la comtesse]).

References

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Paul Signac, Portrieux, The Bathing Cabins, Opus 185 (Beach of the Countess), 1888,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.730.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Paul Signac, Portrieux, The Bathing Cabins, Opus 185 (Beach of the Countess), 1888,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.730.4033.

Société des Artistes indépendants: Peintres, sculpteurs, graveurs, dessinateurs et architectes; Catalogue des œuvres exposées, exh. cat. (Paris: Imprimerie A. Lahure, 1890), 37 [repr., in Theodore Reff, ed., Modern Art in Paris: Two-Hundred Catalogues of the Major Exhibitions Reproduced in Facsimile in Forty-Seven Volumes, vol. 9, Salons of the “Indépendants” 1884–1891 (New York: Garland, 1981), unpaginated], as La mer—De Portrieux (Côtes-du-Nord), juin, juillet, août, septembre 1888, Op. 185.

Jules Christophe, “Causerie: L’Impressionnisme; L’exposition des artistes indépendants,” Journal des artistes, no. 13 (April 6, 1890): 102.

Gustave Geffroy, “Chronique d’art: Indépendants,” La Revue d’Aujourd’hui 1, no. 4 (April 15, 1890): 270.

J[ulien] L[eclercq], “Beaux-arts: Aux Indépendants,” Mercure de France 1, no. 5 (May 1890): 175.

Gustave Coquiot, Les indépendants: 1884–1920 (Paris: Librairie Ollendorff, [1921]), 14.

Vincent van Gogh en zijn tijdgenooten, exh. cat. (Amsterdam: Stedelijk Museum, 1930), 98, as Het strand.

Paintings, Watercolors, and Drawings of the Moderns: The Private Collection of Dikran G. Kelekian, Esq. (New York: Rains Galleries, January 18, 1935), 16, (repro.), as The Seashore.

Marie-Thérèse Lemoyne de Forges, Signac, exh. cat. (Paris: Ministère d’état, Affaires culturelles, 1963), 29.

Sophie Monneret, L’impressionnisme et son époque: Dictionnaire international illustré (Paris: Editions Denoël, 1979), 2:256.

Peter J. Flagg, “The Neo-Impressionist Landscape” (PhD diss., Princeton University, 1988), 131–32.

The Collection of Jerome K. Ohrbach (New York: Sotheby’s, November 13, 1990), unpaginated, (repro.), as La Plage.

Françoise Cachin, Signac: Catalogue raisonné de l’œuvre peint (Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 2000), no. 169, pp. 188, 356, 358, (repro.), as Portrieux. Les Cabines. Opus 185 (plage de la Comtesse).

Marina Ferretti-Bocquillon et al., Signac, 1863–1935, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2001), 133, 303.

Anne Distel, Signac: Au temps d’harmonie, exh. cat. (Paris: Gallimard / Réunion des musées nationaux, 2001), 47.

Françoise Cachin and Marina Ferretti-Bocquillon, P. Signac, exh. cat. (Paris: A.D.A.G.P., 2003), 48, 262, as Portrieux. Les Cabines.

Jane Munro, French Impressionists (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 132.

Robyn Roslak, “Symphonic Seas, Oceans of Liberty: Paul Signac’s La Mer: Les Barques (Concarneau),” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 4, no. 1 (Spring 2005): 39n11, http://19thc-artworldwide.org/index.php/component/content/article/64-spring05article/302-symphonic-seas-oceans-of-liberty-paul-signacs-la-mer-les-barques-concarneau.

Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 11, 16–17, 108–11, 159–60, (repro.), as Portrieux, The Bathing Cabins, Opus 185 (Beach of the Countess) (Portrieux, Les cabines, Opus 185 [Plage de la comtesse]).

Alice Thorson, “A Tiny Renoir Began Impressive Obsession,” Kansas City Star 127, no. 269 (June 3, 2007): E4–E5.

Louise Pollock Gruenebaum, “Letters: Bloch Building,” Kansas City Star 127, no. 272 (June 16, 2007): B10.

Marina Ferretti Bocquillon, Georges Seurat, Paul Signac e i neoimpressionisti, exh. cat. (Milan: Skira, 2008), 234.

Alice Thorson, “Blochs add to Nelson treasures,” Kansas City Star 130, no. 141 (February 5, 2010): A1, A8.

Carol Vogel, “O! Say, You Can Bid on a Johns,” New York Times 159, no. 54,942 (February 5, 2010): C26.

Alice Thorson, “Gift will leave lasting impression,” Kansas City Star 130, no. 143 (February 7, 2010): G1–G2.

Thomas M. Bloch, Many Happy Returns: The Story of Henry Bloch, America’s Tax Man (Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons, 2011), 174–75.

Diane Stafford, “Bloch gift to go for Nelson upgrade,” Kansas City Star 135, no. 203 (April 8, 2015): A1, A8.

“Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art officially accessions Bloch Impressionist masterpieces,” Artdaily.org (July 25, 2015): http://artdaily.com/news/80246/Nelson-Atkins-Museum-of-Art-officially-accessions-Bloch-Impressionist-masterpieces.

Julie Paulais, “Le Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art reçoit des tableaux impressionnistes en échange de leurs répliques,” Le Journal des arts (July 30, 2015): https://www.lejournaldesarts.fr/patrimoine/le-nelson-atkins-museum-art-recoit-des-tableaux-impressionnistes-en-echange-de-leurs.

Josh Niland, “The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Acquires a Renowned Collection of Impressionist and Postimpressionist Art,” architecturaldigest.com (July 31, 2015): https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/nelson-atkins-museum-accessions-bloch-art-collection.

Nancy Staab, “Van Gogh is a Go!” 435: Kansas City’s Magazine (September 2015): 76.

Marianne Jakobi, Gauguin-Signac: La genèse du titre contemporain (Paris: CNRS Éditions, 2015), 259, (repro.), as Op. 185 and Portrieux, Les Cabines, Opus 185.

Seurat, Van Gogh, Mondrian: Il post-impressionismo in Europa, exh. cat. (Milan: 24 ORE Cultura, 2015), 66.

“Nelson-Atkins to unveil renovated Bloch Galleries of European Art in winter 2017,” Artdaily.org (July 20, 2016): http://artdaily.com/news/88852/Nelson-Atkins-to-unveil-renovated-Bloch-Galleries-of-European-Art-in-winter-2017-.

“Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art celebrates generosity of Henry Bloch with new acquisition,” Artdaily.org (October 18, 2016): https://artdaily.cc/news/90923/Nelson-Atkins-Museum-of-Art-celebrates-generosity-of-Henry-Bloch-with-new-acquisition#.XnKATqhKiUk.

Catherine Futter et al., Bloch Galleries: Highlights from the Collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2016), 100, (repro.), as Portrieux, The Bathing Cabins, Opus 185 (Beach of the Countess).

Kelly Crow, “Museum Rewards Donor with Fake Art to Hang at Home,” Wall Street Journal (January 25, 2017): https://www.wsj.com/articles/museum-rewards-donor-with-fake-art-to-hang-at-home-1485370768.

David Frese, “Bloch savors paintings in redone galleries,” Kansas City Star (February 25, 2017): 1A, 14A.

Albert Hecht, “Henry Bloch’s Masterpieces Collection to Go On Display at Nelson-Atkins Museum,” Jewish Business News (February 26, 2017): http://jewishbusinessnews.com/2017/02/26/henry-bloch-masterpieces-collection/.

David Frese, “A collection of stories,” and “Inside the Bloch Galleries: An interactive experience,” Kansas City Star 137, no. 169 (March 5, 2017): 1D, 4D, (repro.), as Portrieux, the Bathing Cabins, Opus 185 (Beach of the Countess).

“Editorial: Thank you, Henry and Marion Bloch,” Kansas City Star (March 7, 2017), http://www.kansascity.com/opinion/editorials/article137040948.html [repr., in “Thank you, Henry and Marion Bloch,” Kansas City Star 137, no. 172 (March 8, 2017): 16A].

Hampton Stevens, “(Not Actually) 12 Things To Do During The Big 12 Tournament,” Flatland: KCPT’s Digital Magazine (March 9, 2017): http://www.flatlandkc.org/arts-culture/sports/not-actually-12-big-12-tournament/.

Laura Spencer, “The Nelson-Atkins’ Bloch Galleries Feature Old Masterworks and New Technology,” KCUR (March 10, 2017): http://kcur.org/post/nelson-atkins-bloch-galleries-feature-old-masterworks-and-new-technology#stream/0.

Victoria Stapley-Brown, “Nelson-Atkins Museum’s new European art galleries come with a ‘love story,’” Art Newspaper (March 10, 2017): http://theartnewspaper.com/news/museums/nelson-atkins-museum-s-new-european-art-galleries-come-with-a-love-story/.

Harry Bellet, “Don du ciel pour le Musée Nelson-Atkins,” Le Monde (March 13, 2017): http://theartnewspaper.com/news/museums/nelson-atkins-museum-s-new-european-art-galleries-come-with-a-love-story/.

Menachem Wecker, “Jewish Philanthropist Establishes Kansas City as Cultural Mecca,” Forward (March 14, 2017): http://forward.com/culture/365264/jewish-philanthropist-establishes-kansas-city-as-cultural-mecca// [repr., in Menachem Wecker, “Kansas City Collection Is A Chip Off the Old Bloch,” Forward (March 17, 2017): 20–22].

Juliet Helmke, “The Bloch Collection Takes up Residence in Kansas City’s Nelson Atkins Museum,” Blouin ArtInfo International (March 15, 2017): http://www.blouinartinfo.com/news/story/2005267/the-bloch-collection-takes-up-residence-in-kansas-citys.

Louise Nicholson, “How Kansas City got its magnificent museum,” Apollo: The International Art Magazine (April 7, 2017): https://www.apollo-magazine.com/how-kansas-city-got-its-magnificent-museum/.

Lilly Wei, “Julián Zugazagoitia: ‘Museums should generate interest and open a door that leads to further learning,’” Studio International (August 21, 2017): http://studiointernational.com/index.php/julian-zugazagoitia-director-nelson-atkins-museum-of-art-kansas-city-interview.

Vivien Greene, ed., Paris, Fin de Siècle: Signac, Redon, Toulouse-Lautrec, y sus Contemporáneos, exh. cat. (Bilbao: Guggenheim Bilbao, 2017), 12.

The Collection of Peggy and David Rockefeller, vol. 1, 19th and 20th Century Art Evening Sale (New York: Christie’s, May 8, 2018), 352, 354.

Robert D. Hershey Jr., “Henry Bloch, H&R Block’s cofounder, dies at 96,” Boston Globe (April 23, 2019): https://www3.bostonglobe.com/metro/obituaries/2019/04/23/henry-bloch-block-cofounder/?arc404=true.

Robert D. Hershey Jr., “Henry W. Bloch, Tax-Preparation Pioneer (and Pitchman), Is Dead at 96,” New York Times (April 23, 2019): https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/23/obituaries/henry-w-bloch-dead.html.

Megan McDonough, “Henry Bloch, whose H&R Block became world’s largest tax-services provider, dies at 96,” Washington Post (April 23, 2019): https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/obituaries/henry-bloch-whose-handr-block-became-worlds-largest-tax-services-provider-dies-at-96/2019/04/23/19e95a90-65f8-11e9-a1b6-b29b90efa879_story.html.

Claire Selvin, “Henry Wollman Bloch, Collector and Prominent Benefactor of Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Is Dead at 96,” ArtNews (April 23, 2019): http://www.artnews.com/2019/04/23/henry-bloch-dead-96/.

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “Henry Bloch, co-founder of H&R Block, dies at 96,” Kansas City Star 139, no. 219 (April 24, 2019): 1A, 2A.

“Henry Wollman Bloch (1922–2019),” Artforum (April 24, 2019): https://www.artforum.com/news/henry-wollman-bloch-1922-2019-79547.

Frank Morris, “Henry Bloch, Co-Founder Of H&R Block, Dies At 96,” NPR (April 24, 2019): https:www.npr.org/2019/04/24/716641448/henry-bloch-co-founder-of-h-r-block-dies-at-96.

Ignacio Villarreal, “Nelson-Atkins mourns loss of Henry Bloch,” ArtDaily.org (April 24, 2019): https://artdaily.com/news/113035/Nelson-Atkins-mourns-loss-of-Henry-Bloch#.XMB76qR7laQ.

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “H&R Block co-founder, philanthropist Bloch dies,” Cass County Democrat Missourian 140, no. 29 (April 26, 2019): 1A.

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “KC businessman and philanthropist Henry Bloch dies,” Lee’s Summit Journal 132, no. 79 (April 26, 2019): 1A.

Luke Nozicka, “Family and friends remember Henry Bloch of H&R Block,” Kansas City Star 139, no. 225 (April 30, 2019): 4A [repr., in Luke Nozicka, “Family and friends remember Henry Bloch of H&R Block,” Kansas City Star 139, no. 228 (May 3, 2019): 3A].

Eric Adler, “Sold for $3.25 million, Bloch’s home in Mission Hills may be torn down,” Kansas City Star 141, no. 90 (December 16, 2020): 2A.

Kristie C. Wolferman, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A History (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2020), 345.

Marina Ferretti Bocquillon, Paul Signac, l’air du large, exh. cat. (Rouen: Éditions des Falaises, 2021), 78, (repro.), as Portrieux. Les Cabines; Opus 185.

Paul Signac, Journal: 1894–1909, ed. Charlotte Hellman (Paris: Gallimard, 2021), 184n374.