![]()

Paul Gauguin, Faaturuma (Melancholic), 1891

| Artist | Paul Gauguin, French, 1848–1903 |

| Title | Faaturuma (Melancholic) |

| Object Date | 1891 |

| Alternate and Variant Titles | Mélancolique; Rêverie |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (Unframed) | 37 x 26 7/8 in. (94 x 68.3 cm) |

| Signature | Signed and dated lower right: P. Gauguin. 91 |

| Inscription | Inscribed upper left: Faaturuma |

| Credit Line | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 38-5 |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Elizabeth C. Childs, “Paul Gauguin, Faaturuma (Melancholic), 1891,” catalogue entry in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.716.5407

MLA:

Childs, Elizabeth C. “Paul Gauguin, Faaturuma (Melancholic), 1891,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.716.5407.

This canvas is one of the best-known compositions from Paul Gauguin’s (1848–1903) highly productive first sojourn to Tahiti, where he resided from June 9, 1891 to June 4, 1893. The painting is one of forty-one Tahitian canvases he included in a landmark exhibition at the Galeries Durand-Ruel in Paris in November 1893;1Exposition d’Œuvres récentes de Paul Gauguin, November 9–25, 1893, no. 28, as Mélancolique (or possibly no. 27, Faturuma [sic] (Boudeuse). This catalogue is not illustrated. its inclusion there demonstrates both his confidence that this painting was a significant work within his new Tahitian oeuvre, and that he conceived his art about Polynesian subjects with a Parisian audience in mind.

The canvas belongs to the group of approximately twenty works he painted late in 1891 after he left the capital of Papeete for Mataiea, a smaller town on the southern coast of Tahiti. This move represented his effort to leave behind the disappointingly pervasive European influence in the colonial capital and to seek a simpler lifestyle more in harmony with what he had imagined traditional Tahitian life would be. There he established a home, although his relationships with local Tahitians were hampered by his imperfect command of the language and his practice of an art that most of them did not appreciate. In the later months of 1891, he probably initiated a domestic partnership with a young Tahitian woman named Tehe’amana; if one were to believe his partly fictionalized autobiography Noa Noa (which he began writing in 1893), she was a youth of thirteen or fourteen years who lived with her family on the remote east coast of the island, and who agreed, with her parents’ permission, to live with Gauguin in Mataiea.2A useful summary of what is known about Tehe’amana is offered in Richard R. Brettell and Genevieve Westerby, “Gauguin, Cat. 50, Merahi metua no Tehamana (Tehamana Has Many Parents or The Ancestors of Tehamana) (1980.613): Commentary,” in Gauguin Paintings, Sculpture and Graphic Works at the Art Institute of Chicago, eds. Gloria Groom and Genevieve Westerby (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2016), para. 3, https://publications.artic.edu/gauguin/reader/gauguinart/section/140288/140288\_anchor. It is often assumed, based on the artist’s own, often exaggerated or invented narrative, that the model in the Nelson-Atkins painting is Tehe’amana. However, there is no clear support for this identification.

In this intensely colored figure study, a young woman sits in a French colonial rocking chair in a shallow interior space defined by an earthen-colored floor and a rich marine blue wall. The copious dress draws attention to the arresting hot salmon color that pulsates on the surface of the canvas. In the course of painting the dress, Gauguin lengthened the skirt’s hemline by several inches, thus accentuating a single bare foot that is elongated beyond natural proportion. A distracting note is introduced by the bright yellow brushwork broadly painted across her brown toes, which announces a purely painterly touch. Other bold touches include two parallel pink strokes that hover improbably on the blue wall at the upper right. By such means, Gauguin asserts that his picture is a poetic and decorative arrangement of form on canvas, an embodiment of visual ideas as much as it is a composed portrait or a memory of his observations.

Close looking reveals how thoroughly he attends to this artistic mission: he uses a dark black or blue outline in the manner of CloisonnismCloisonnism: A style of painting associated with some of the painters who worked at Pont-Aven in Brittany in the 1880s and 1890s. It is characterized by flat forms of bold colors separated by dark outlines. The term is derived from cloisonné, a kind of decorative enamelwork. (a style he adopted in Brittany in 1888 when working with Émile Bernard [1868–1941]) to establish the strong contours of the woman’s figure. In some areas, such as along the right edge of the sitter’s arm and along the edges of her black hair at her temple, those defining lines are brightly elaborated by little hot pink dots to make the lines scintillate. The painting is therefore, based on a subtle contradiction that engages both mind and eye: as much as the mood of the scene is one of silence and enervation, the lines, forms, and colors sing together energetically and in brazen harmony.

Gauguin’s sitter wears a gown known as a Mother Hubbard dress, an extremely common fashion that was first introduced by missionaries in the nineteenth century to “civilize” local women, and was adopted throughout colonial Polynesia from Hawaii to Tahiti.3An exhaustive study on this fashion is Sally Helvenston Gray, “Searching for Mother Hubbard: Function and Fashion in Nineteenth-Century Dress,” Winterthur Portfolio 48, no. 1 (Spring 2014): 29–73. Such gowns were well-favored in the islands because they were relatively easy for novice seamstresses to design and sew; they were suitable as both a day dress to be worn in town, and as a loose garment appropriate for work; and the unfitted lines facilitated ready ventilation in the hot tropical climate. The Mother Hubbard dress replaced the traditional garments made of tapa cloth and also the printed pareu (wraparound garment), covering women in a missionary-approved modest style that largely hid the female body from view. As such, the gown represented the “modern” dress of the proper colonial woman who had adapted to European-approved ways. Other significant details of French style include the ring on the sitter’s left hand, which indicates her married status, and the embroidered handkerchief, a touch of European femininity. These details, along with the modest costume and the colonial rocker, establish the sitter as a modern Tahitienne. Yet other details, such as her bare foot pushed noticeably up against the front of the picture planepicture plane: The two-dimensional surface where the artist applies paint. to command the viewer’s attention, reiterate that her accommodation to European style is only partial. Her clothing thus reaffirms the mix of the local and imported cultural practices, a hybridity typical of this island in the 1890s.

While the woman’s long dark hair and warm brown-orange skin may have hinted at her Pacific Islander identity, two details of the framed image in the upper-left corner of the composition confirm it: both the scene itself, and the inscription of a title in Tahitian on the painted frame. The wide brown rectangular frame sets off a scene of a traditional thatched hut on a verdant plot of land. The brown frame could indicate either a window pierced through the wall, giving a view onto the village, or the frame of a painting on the wall. Given the openly painted facturefacture: The artist’s characteristic handling of paint. of the scene and a highly colorful assortment of hues that denote the thatched vegetation of the roof, the image most likely represents not “nature” through a window, but a painting (now lost) by the artist.4A similar type of landscape is Gauguin’s Dog in front of the hut, Tahiti, 1892, oil on canvas, 16 1/4 x 26 7/16 in. (41.2 x 67.1 cm), Pola Museum of Art, Hakone-machi, Japan. It also emphasizes his role as both artist and observer in this Tahitian world.

There is a tantalizing clue to the overall meaning of the picture: the title Faaturuma is inscribed on that picture frame (or window frame). Gauguin’s command of the Tahitian language was only tentative at this time; as he admitted in November 1891, he was not yet strong in Tahitian in spite of much effort.5In a letter to Paul Serusier (1864–1927), Gauguin wrote, “Je ne suis pas encore bien fort sur la langue du pays, malgré tous les efforts.” Quoted in Marianne Jakobi, Gauguin-Signac: La genèse du titre contemporain (Paris: CNRS Éditions, 2015), 107. Nonetheless, throughout the 1890s he inscribed titles in the Tahitian language prominently on many of his canvases, often in a highly contrasting hue such as the orange-red used here to attract the eye.6Out of the 194 canvases he painted in Tahiti between 1891 and 1901, Gauguin painted titles in Tahitian on 82 of them. Jakobi, Gauguin-Signac, 133. In some cases, he instructed his friend George-Daniel de Monfreid (1856–1929), in Paris, to do the inscriptions. Showcasing such words signaled that the painting’s subject belonged to what was for the Parisian viewer a novel and mysterious culture; Gauguin intended these titles to lure and confound the viewer through their very inscrutability. When he exhibited these canvases in Paris in 1893, the catalogue included many French translations of his Tahitian titles, thus appearing to present him both as an authority on and interpreter of the distant culture.

The title Faaturuma can be translated one of two ways into French:

either as mélancolie or as boudeuse. In English, these words

translate as melancholic, a sulky woman, or silence.7See Sven Wahlroos, English-Tahitian/Tahitian-English Dictionary (Papeete: privately published, 2002), 574. See also correspondence between Meghan Gray, curatorial associate, Nelson-Atkins, and Ervelyne Bernard, translator of Tahitian and French, November 18, 2016, NAMA curatorial files. In a letter he

wrote in 1892 to Mette, his French wife in Paris, Gauguin offered a

translation of the title of a related painting Te Faaturuma (Fig. 1)

as “le silence” (“silence”) or “être morne” (“a gloomy being”), which

demonstrates that he indeed grasped the meaning of the phrase.8Gauguin to Mette, December 8, 1892, in Maurice Malingue, ed., Lettres de Gauguin à sa femme et à ses amis (Paris: Bernard, Grasset, 1946), letter CXXXIV, p. 236. And

indeed, those ideas describe the apparent mood of the sitter in

Faaturuma, and of the painting overall.

Fig. 1. Paul Gauguin, Te Faaturuma (The Brooding Woman), 1891, oil on canvas, 35 7/8 x 27 1/16 in. (91.1 x 68.7 cm), Worcester Art Museum, Worcester, MA. Museum Purchase, 1921.186

Fig. 1. Paul Gauguin, Te Faaturuma (The Brooding Woman), 1891, oil on canvas, 35 7/8 x 27 1/16 in. (91.1 x 68.7 cm), Worcester Art Museum, Worcester, MA. Museum Purchase, 1921.186

Fig. 2. Camille Corot, The Letter, ca. 1865, oil on wood, 21 1/2 x 14 1/4 in. (54.6 x 36.2 cm), The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 29.160.33. H. O. Havemeyer Collection, Gift of Horace Havemeyer, 1929

Fig. 2. Camille Corot, The Letter, ca. 1865, oil on wood, 21 1/2 x 14 1/4 in. (54.6 x 36.2 cm), The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 29.160.33. H. O. Havemeyer Collection, Gift of Horace Havemeyer, 1929

The self-absorbed young woman inclines her head forward and tilts it slightly to the side, as she looks away from the viewer. Her full lips register no emotion, and her eyebrow closest to the viewer arches slightly, suggesting her introspection. Her hands rest listlessly on her lap and on the armrest. She may be quietly rocking forward; the back of the chair does not touch the floor. Her affect is one of quietude, reflection, and even wistfulness. This is no novel subject. The topos of the contemplative young woman recalls in particular the figure studies by Barbizon painter Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796–1875), who was well known for his studies of female models, often dressed in Italian peasant costume and shown reading or dozing in a chair in the studio. One such picture is of particular import here, as Gauguin’s godfather Gustave Arosa had owned just such a painting by Corot, The Letter (Fig. 2), in the 1870s. Gauguin had with him in Tahiti a copy of the illustrated sales catalogue of the Arosa estate sale in 1878, and thus had a collotype reproduction of the Corot painting available to hang on the wall of his studio/hut. He relished having reproductions of famous European paintings with him, as sources of inspiration and as reminders of the broader world of art where he wanted to make his contribution. Before leaving France, Gauguin had written to artist Odilon Redon (1840–1916) that his collection of images would be like having “an entire little world of friends with me in the form of photographs [and] drawings who will talk to me every day.” 9“J’emporte en photographies, dessins, tout un petit monde de camarades qui me causeront tous les jours.” Quoted in Roseline Bacou and Ari Redon, eds., Lettres de Gauguin, Gide, Huysmans, Jammes, Mallarmé, Verhaeren . . . à Odilon Redon (Paris: Librairie José Corti, 1960), letter no. III, p. 193. Corot’s subject of the docile model lost in thought was a prototype Gauguin could transform into a uniquely Tahitian idiom in Faaturuma.

However, the reference here is not only to Corot’s studio muse, but also

to the idea, as Gauguin understood it, of colonial Tahiti at that time.

Gauguin often associated notions of silence and melancholy with the

Tahitians he encountered.10See his letter to Mette, July 1891, “Je comprends pourquoi ces individus peuvent rester des heures, des journées assis sans dire un mot et regarder le ciel avec mélancolie” (I understand why these people can remain hours and days seated saying nothing, and regarding the sky with melancholy), in Malingue, ed., Lettres de Gauguin, letter CXXVI, p. 218. In several pictures, these qualities

assume feminine form. In the related painting Te Faaturuma (Fig. 1), a

somewhat sulky young Tahitienne sits in a brightly colored but

emphatically empty interior, isolating herself in her reverie as a male

companion approaches or waits outside. In these paintings, Gauguin

infuses his Tahitian women with passivity, listlessness, moodiness, and

perhaps regret. The modern Tahitian woman was understood in some popular

travel accounts as being nostalgic for the fading culture of traditional

Tahiti. The young woman in the Nelson-Atkins canvas, who wears a modest

dress and a wedding ring and holds a handkerchief ready to wipe away a

tear, counters the stereotype of the sexually free and uninhibited

vahiné (unmarried young Polynesian woman) that had been so widely

celebrated in European travel descriptions since the time of French

explorer, Louis Antoine de Bougainville (1729–1811). In travel journals

Gauguin could have read in Paris that in the mid-nineteenth century,

Tahiti’s famed “alluring sirens” had still been “free as birds” and

could give their bodies to serve their own pleasures and desires.11“sirènes provocantes”; “libre comme l’oiseau” in Louis d’Hura, “Notre nouvelle colonie, Tahiti,” Journal des Voyages 7, no. 171 (October 17, 1880): 232.

Modernity and civilization, such a narrative argued, had brought these

indigenous women under the control of church and marriage, and now they

could only dream of former liberties.12For a discussion of this idea in the travel literature, such as in the Journal des Voyages in 1880, see Elizabeth C. Childs, Vanishing Paradise: Art and Exoticism in Colonial Tahiti (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013), 119–25. Gauguin’s sitter, at once

resplendent in and contained by her copious missionary gown, and

conspicuously displaying the wedding ring as her only jewelry, belongs

to this contemporary generation of women whom the artist imagined both

regretted their present Europeanized society and dreamt of former times.

In this way, Gauguin sometimes used the figure of the indigenous

Polynesian woman as a metaphor for the inherent losses wrought by the

colonial world. The distant and passive demeanor he imposes on his

sitter also echoes the mood of numerous photographic portraits of

Tahitian women made for sale by commercial studios in Papeete (Fig. 3).

These images, sold both locally and exported to the United States and

France, were collectibles of the time, and offered souvenir images of

the contemporary Tahitian woman enthroned in her colonial chair, looking

as if she quietly accepted her modern colonial status.13For several examples of these photographs, see Elizabeth C. Childs, “Paradise Redux: Gauguin, Photography, and Fin-de-Siècle Tahiti,” in Dorothy Kosinski, ed., The Artist and the Camera: Degas to Picasso, exh. cat. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999), 136.

Fig. 3. Charles Spitz, Tahitian Woman, ca. 1890, albumen print, Musée de Tahiti et des îles /Te Fare Manaha, Puna’auia, Tahiti, D2004.32.152

Fig. 3. Charles Spitz, Tahitian Woman, ca. 1890, albumen print, Musée de Tahiti et des îles /Te Fare Manaha, Puna’auia, Tahiti, D2004.32.152

Fig. 4. Paul Gauguin, Seated Tahitian Woman (related to the painting Te faaturuma [Reverie]), verso, 1891/1893, charcoal on cream wove paper, 18 15/16 x 21 14/16 in. (48 x 55.5 cm), Art Institute of Chicago, Margaret Day Blake Collection, 1944.578V

Fig. 4. Paul Gauguin, Seated Tahitian Woman (related to the painting Te faaturuma [Reverie]), verso, 1891/1893, charcoal on cream wove paper, 18 15/16 x 21 14/16 in. (48 x 55.5 cm), Art Institute of Chicago, Margaret Day Blake Collection, 1944.578V

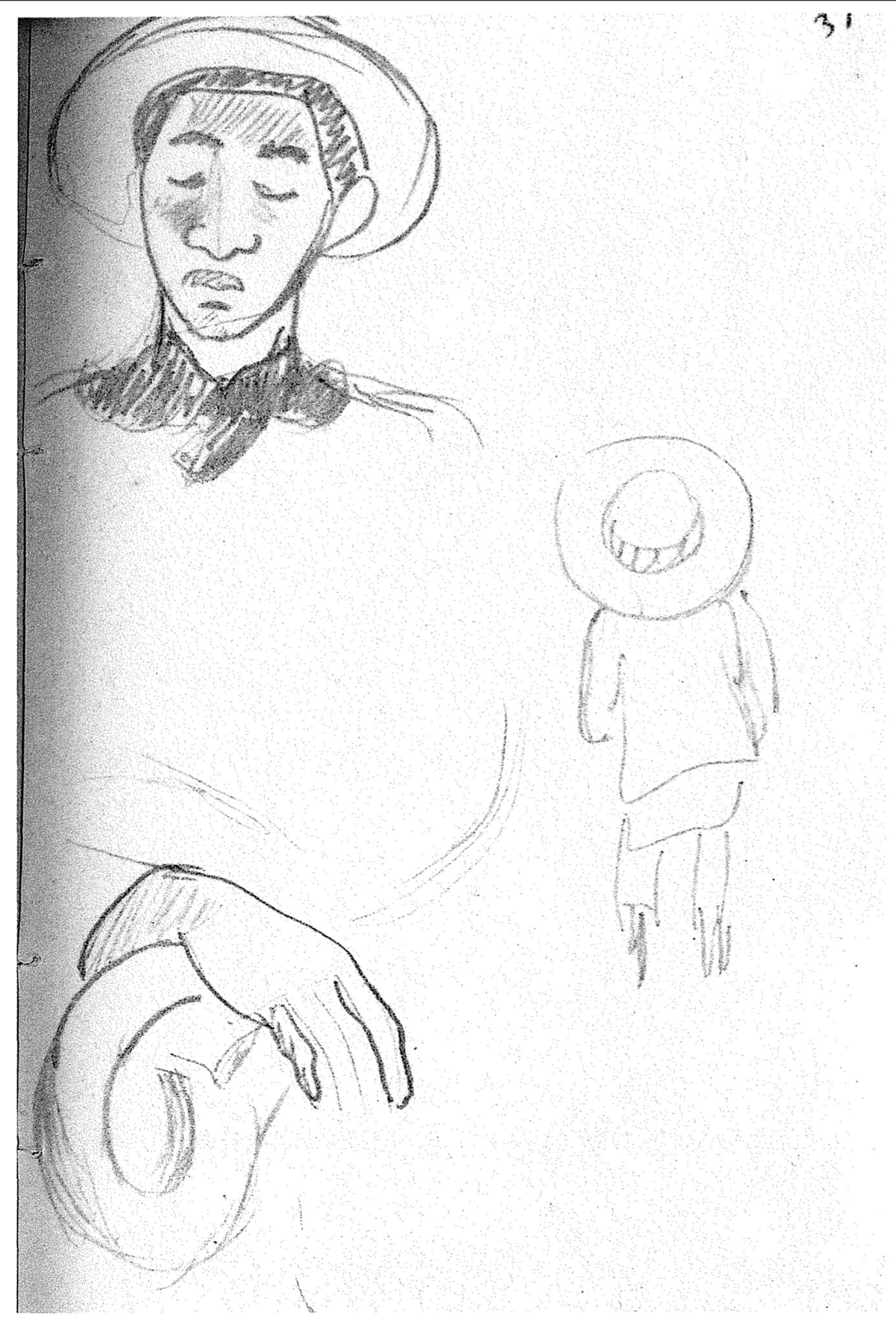

Gauguin only rarely made formal preparatory studies for his large painted compositions. In this case, there are two relatively modest drawings that may be related to his initial thinking about the subject. One is a pencil study of a Tahitian woman wearing a Mother Hubbard gown, whose eyes are lowered or closed, and who cradles a small dog or pig in her lap (Fig. 4). The mood of the scene is as quiet and introverted as Faaturuma, although the two figures may not be drawn from the same model, as the nose of the face in the pencil sketch is decidedly broader than that of the woman in the Nelson-Atkins canvas. Another sketch (Fig. 5) records the detail of a hand listlessly draped across the arm of a rocker, a study that confirms the artist’s ability to observe compelling details of the body at rest. The figure of Faaturuma took shape on the canvas itself: Gauguin made a preliminary outline for the figure in paint directly on the canvas, and pentimentipentimento (pl: pentimenti): A change to the composition made by the artist that is visible on the paint surface. Often with time, pentimenti become more visible as the upper layers of paint become more transparent with age. Italian for "repentance" or "a change of mind." attest to his initial attempts to render the dress that ultimately dominates this composition.14See the accompanying technical essay by Mary Schafer, Nelson-Atkins paintings conservator. This figure thus only came into full focus for the artist as she assumed her place in the painting.

Notes

- Exposition d’Œuvres récentes de Paul Gauguin, November 9–25, 1893, no. 28, as Mélancolique (or possibly no. 27, Faturuma [sic] (Boudeuse). This catalogue is not illustrated.

- A useful summary of what is known about Tehe’amana is offered in Richard R. Brettell and Genevieve Westerby, “Gauguin, Cat. 50, Merahi metua no Tehamana (Tehamana Has Many Parents or The Ancestors of Tehamana) (1980.613): Commentary,” in Gauguin Paintings, Sculpture and Graphic Works at the Art Institute of Chicago, eds. Gloria Groom and Genevieve Westerby (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2016), para. 3, https://publications.artic.edu/gauguin/reader/gauguinart/section/140288/140288_anchor.

- An exhaustive study on this fashion is Sally Helvenston Gray, “Searching for Mother Hubbard: Function and Fashion in Nineteenth-Century Dress,” Winterthur Portfolio 48, no. 1 (Spring 2014): 29–73.

- A similar type of landscape is Gauguin’s Dog in front of the hut, Tahiti, 1892, oil on canvas, 16 1/4 x 26 7/16 in. (41.2 x 67.1 cm), Pola Museum of Art, Hakone-machi, Japan.

- In a letter to Paul Serusier (1864–1927), Gauguin wrote, “Je ne suis pas encore bien fort sur la langue du pays, malgré tous les efforts.” Quoted in Marianne Jakobi, Gauguin-Signac: La genèse du titre contemporain (Paris: CNRS Éditions, 2015), 107.

- Out of the 194 canvases he painted in Tahiti between 1891 and 1901, Gauguin painted titles in Tahitian on 82 of them. Jakobi, Gauguin-Signac, 133. In some cases, he instructed his friend George-Daniel de Monfreid (1856–1929), in Paris, to do the inscriptions.

- See Sven Wahlroos, English-Tahitian/Tahitian-English Dictionary (Papeete: privately published, 2002), 574. See also correspondence between Meghan Gray, curatorial associate, Nelson-Atkins, and Ervelyne Bernard, translator of Tahitian and French, November 18, 2016, NAMA curatorial files.

- Gauguin to Mette, December 8, 1892, in Maurice Malingue, ed., Lettres de Gauguin à sa femme et à ses amis (Paris: Bernard, Grasset, 1946), letter CXXXIV, p. 236.

- “J’emporte en photographies, dessins, tout un petit monde de camarades qui me causeront tous les jours.” Quoted in Roseline Bacou and Ari Redon, eds., Lettres de Gauguin, Gide, Huysmans, Jammes, Mallarmé, Verhaeren. . . à Odilon Redon (Paris: Librairie José Corti, 1960), letter no. III, p. 193.

- See his letter to Mette, July 1891, “Je comprends pourquoi ces individus peuvent rester des heures, des journées assis sans dire un mot et regarder le ciel avec mélancolie” (I understand why these people can remain hours and days seated saying nothing, and regarding the sky with melancholy), in Malingue, ed., Lettres de Gauguin, letter CXXVI, p. 218.

- “sirènes provocantes”; “libre comme l’oiseau” in Louis d’Hura, “Notre nouvelle colonie, Tahiti,” Journal des Voyages 7, no. 171 (October 17, 1880): 232.

- For a discussion of this idea in the travel literature, such as in the Journal des Voyages in 1880, see Elizabeth C. Childs, Vanishing Paradise: Art and Exoticism in Colonial Tahiti (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013), 119–25.

- For several examples of these photographs, see Elizabeth C. Childs, “Paradise Redux: Gauguin, Photography, and Fin-de-Siècle Tahiti,” in Dorothy Kosinski, ed., The Artist and the Camera: Degas to Picasso, exh. cat. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999), 136.

- See the accompanying technical essay by Mary Schafer, Nelson-Atkins paintings conservator.

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Mary Schafer, “Paul Gauguin, Faaturuma (Melancholic), 1891,” technical entry in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.716.2088

MLA:

Schafer, Mary. “Paul Gauguin, Faaturuma (Melancholic), 1891,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.716.2088.

Faaturuma was executed on a tightly woven, cotton canvas with a half basket weavehalf basket weave: A plain weave produced by double yarns in one direction and a single yarn in the other..1Fiber identification was completed using a Zeiss Aus Jena microscope. See examination report by Scott Heffley, February 22, 1988, NAMA conservation file, no. 38-5. During the 1890s, Paul Gauguin (1848-1903) painted on a variety of canvases, and cotton has been identified on several other works by the artist.2For other examples of cotton supports used by Gauguin, see Carol Christensen, “The Painting Materials and Technique of Paul Gauguin,” Studies in the History of Art, 41 (National Gallery of Art, Washington DC: University Press of New England, 1993), 68–69. Vojtêch Jirat-Wasiutyński and H. Travers Newton Jr., Technique and Meaning in the Paintings of Paul Gauguin (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 156. Van Gogh’s Studio Practice, eds. Marije Vellekoop, Muriel Geldolf, Ella Hendriks, Leo Jansen, and Alberto de Tagle (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), 368. Kristin Hoermann Lister, “Gauguin, Cat. 28, Te burao (The Hibiscus Tree) (1923.308): Technical Study,” in Gauguin Paintings, Sculpture, and Graphic Works at the Art Institute of Chicago, eds. Gloria Groom and Genevieve Westerby (Art Institute of Chicago, 2016), para. 15, https://publications.artic.edu/gauguin/reader/gauguinart/section/140265/p-140265-15. Although the tacking marginstacking margins: The outer edges of canvas that wrap around and are attached to the stretcher or strainer with tacks or staples. See also tacking edge. of the glue-linedlining: A procedure used to reinforce a weakened canvas that involves adhering a second fabric support using adhesive, most often a glue-paste mixture, wax, or synthetic adhesive. canvas are preserved, wooden strips added to the top and bottom edges of the stretcherstretcher: A wooden structure to which the painting’s canvas is attached. Unlike strainers, stretchers can be expanded slightly at the joints to improve canvas tension and avoid sagging due to humidity changes or aging. expand the overall height of the painting by approximately 1.6 centimeters.3A wooden strip extends the top edge of Polynesian Woman with Children (1880; Art Institute of Chicago). See Kristin Hoermann Lister, “Gauguin, Cat. 122, Polynesian Woman with Children (1927.460): Technical Study,” in Gauguin Paintings, Sculpture, and Graphic Works at the Art Institute of Chicago, para. 28, https://publications.artic.edu/gauguin/reader/gauguinart/section/140482/p-140482-28. Paper was adhered to the painting edges and covers the wooden strips, indicating that these components may have been added or reattached when the painting was lined. The current six-member stretcher with mortise and tenon joinery is close in size to the no. 30 paysage (basse) standard-formatstandard-format supports: Commercially prepared supports available through art suppliers, which gained popularity in the nineteenth century during the industrialization of art materials. Available in three formats figure (portrait), paysage (landscape), and marine (marine), these were numbered 1 through 120 to indicate their size. For each numbered size, marine and paysage had two options available: a larger format (haute) and smaller (basse) format. stretcher, rotated ninety degrees.4The no. 30 paysage (basse) standard-format stretcher measures 91.8 x 67.5 centimeters. See Anthea Callen, The Art of Impressionism: Painting Technique and the Making of Modernity (London: Yale University Press, 2000), 15. It is unclear if this support dates to the stretching of the canvas following the painting’s arrival in France.

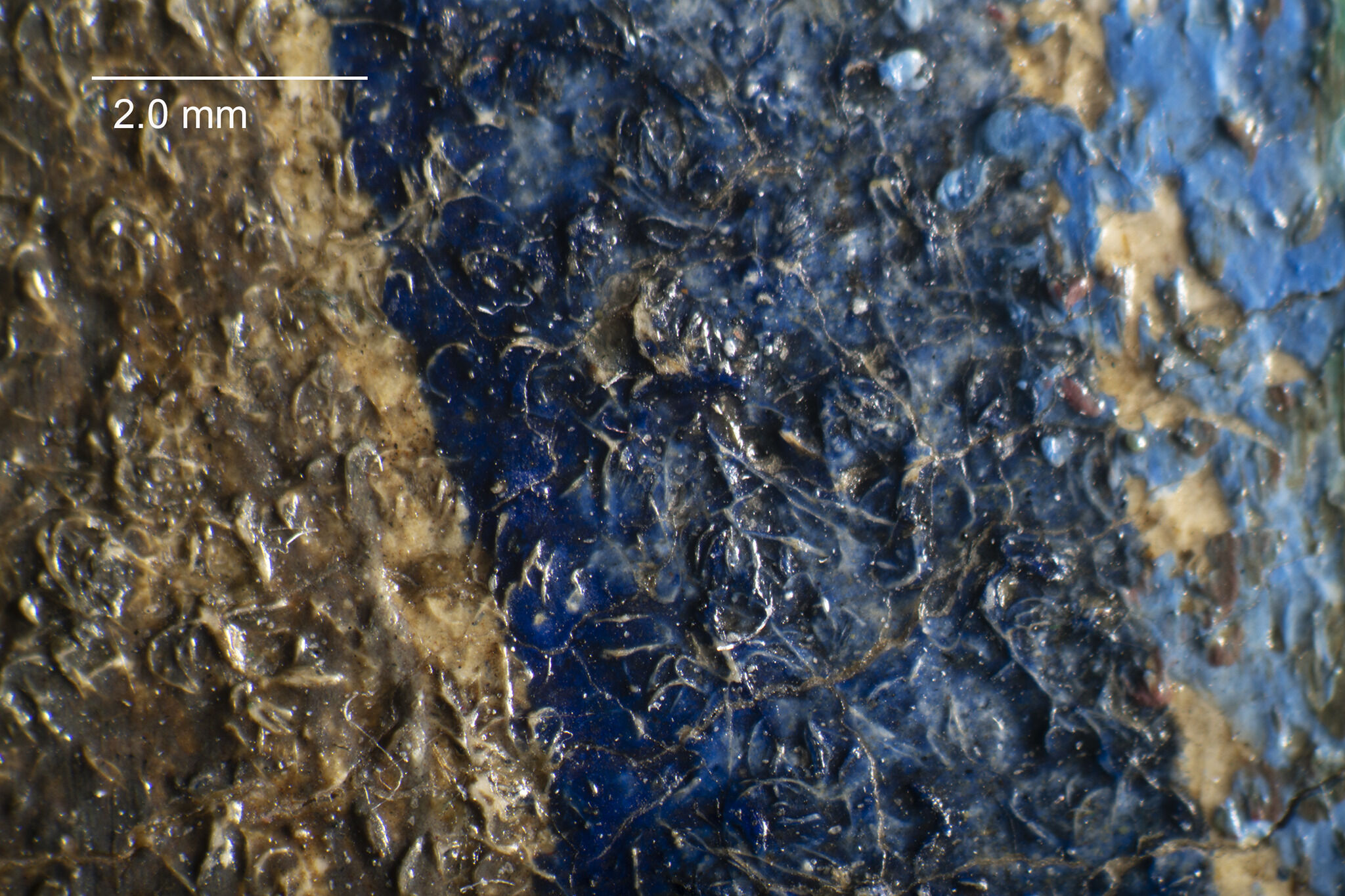

The canvas is primed with a thin, off-white groundground layer: An opaque preparatory layer applied to the support, either commercially or by the artist, to prevent absorption of the paint into the canvas or panel. See also priming layer. that was most likely applied by the artist himself, as it does not continue evenly to the outermost edges of the painting.5During his first trip to Tahiti, Gauguin began to prepare his own canvases. See Colta Feller Ives, Susan Alyson Stein, Charlotte Hale, and Marjorie Shelley, The Lure of the Exotic: Gauguin in New York Collections (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2002), 191. The ground layer is visible throughout the framed painting depicted on the upper left. Under magnification, a fibrous texture is apparent in thinly painted areas, as if Gauguin sanded or roughed up the canvas in some way prior to applying the ground (Fig. 6).6VJirat-Wasiutyński and Newton, Technique and Meaning in the Paintings of Paul Gauguin, 112. The authors observed a “…fuzzy texture of the painting [1888; Self-Portrait, ‘les misérables,’ Van Gogh Museum]…in which the fibers of the canvas, possibly roughed up before application of the paint, were encouraged to stand out and hold tiny peaks of color.” It is possible that a similar sanding or scraping of the canvas caused the fibers to lift, and this effect remains visible in thinly painted areas of Faaturuma. Another example is described in Kristin Hoermann Lister, “Gauguin, Cat. 50, Merahi metua no Tehamana (Tehamana Has Many Parents or The Ancestors of Tehamana) (1980.613): Technical Study,” in Gauguin Paintings, Sculpture, and Graphic Works at the Art Institute of Chicago, para. 25, https://publications.artic.edu/gauguin/reader/gauguinart/section/140288/p-140288-25.

No graphite or charcoal sketch was detected during microscopic

examination or infrared reflectographyinfrared reflectography (IRR): A form of infrared imaging that exploits the behavior of painting materials at wavelengths beyond those accessible to infrared photography. These advantages sometimes include a continuing increase in the transparency of pigments beyond wavelengths accessible to infrared photography (i.e, beyond 1,000 nanometers), rendering underdrawing more clearly. The resulting image is called an infrared reflectogram. Devices that came into common use in the 1980s such as the infrared vidicon effectively revealed these features but suffered from lack of sharpness and uneven response. Vidicons continue to be used out to 2,200 nanometers but several newer pixelated detectors including indium gallium arsenide and indium antimonide array detectors offer improvements. All of these devices are optimally used with filters constraining their response to those parts of the infrared spectrum that reveal the most within the constraints of the palette used for a given painting. They can be used for transmitted light imaging as well as in reflection.. Gauguin outlined compositional

elements using a brush and dilute blue paint, and many of these lines

remain visible between forms. The fluid application of these preparatory

lines is most noticeable within the painted landscape hanging on the

wall (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6. Photomicrograph of raised canvas fibers visible in thinly painted areas, Faaturuma (Melancholic) (1891)

Fig. 6. Photomicrograph of raised canvas fibers visible in thinly painted areas, Faaturuma (Melancholic) (1891)

Fig. 7. Photomicrograph of a dilute blue outline, seen in the lower portion of this image, Faaturuma (Melancholic) (1891)

Fig. 7. Photomicrograph of a dilute blue outline, seen in the lower portion of this image, Faaturuma (Melancholic) (1891)

With the compositional outlines in place, Gauguin began to apply paint

within the confines of these borders. The background wall is made up of

vertical strokes of blue, green, and pink that were applied with a flat

brush approximately 3/8 inches wide. In his rendering of the framed

painting, Gauguin opted to use a palette knife to carefully apply paint

between the blue outlines, forming distinctive marks that differ from

his brushwork elsewhere on the painting. Partially mixed colors and

smooth marks that are characteristic of this tool are evident in Figure 8.

Fig. 8. Raking light detail of the painted landscape in Faaturuma (Melancholic) (1891)

Fig. 8. Raking light detail of the painted landscape in Faaturuma (Melancholic) (1891)

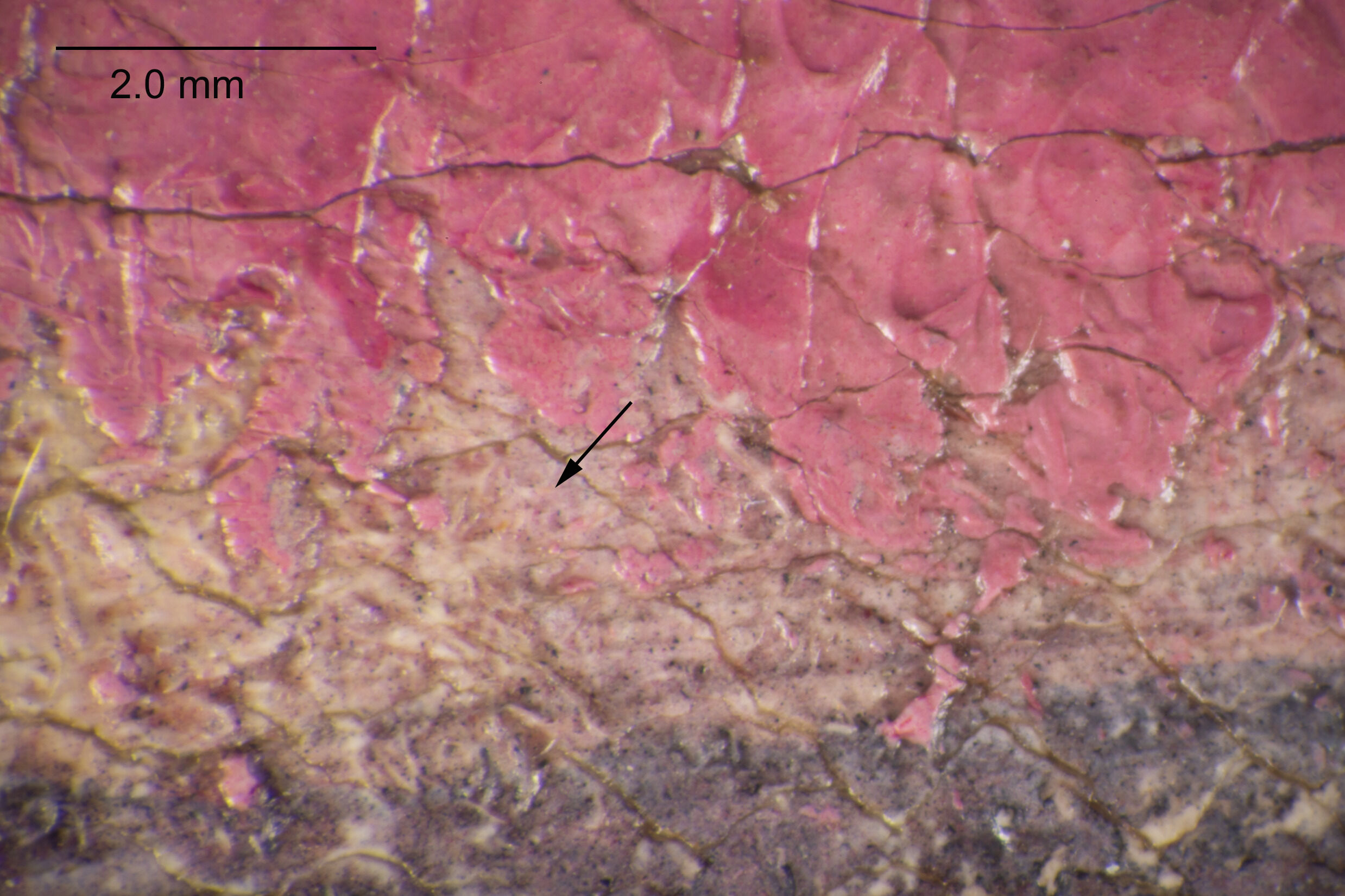

Fig. 9. Photomicrograph of the pale pink underpainting beneath the dress, Faaturuma (Melancholic) (1891)

Fig. 9. Photomicrograph of the pale pink underpainting beneath the dress, Faaturuma (Melancholic) (1891)

Gauguin appears to have underpaintedunderpainting: The first applications of paint that begin to block in color and loosely define the compositional elements. Also called ébauche. the dress with a layer of pale pink (Fig. 9). He then added a range of pink, red, and violet tones, many of which were applied in groupings of parallel hatching strokes. Bright pink at the lower left edge of the dress may have been applied with a palette knife, as it has a smooth, scraped appearance with some exposed ground. A vivid red, applied throughout the sitter’s dress, hair, and lips, produces an intense pink, ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescenceultraviolet (UV) fluorescence or UV-induced visible fluorescence: The reflected visible light produced when painting materials interact with ultraviolet (UV) radiation. Not all materials fluoresce, but the color and intensity of the fluorescence is frequently used to differentiate between original and restoration materials, characterize the varnish layers, or reveal the distribution of pigments across the composition. that suggests the presence of carmine (Fig. 10).7Helmut Schweppe and Heinz Roosen-Runge, “Carmine—Cochineal Carmine and Kermes Carmine,” in Artists’ Pigments: A Handbook of their History and Characteristics, ed. Robert L. Feller (Washington DC: National Gallery of Art, 1986), 1:273.

A fine stroke of bright red paint outlines the proper right cheek and

lower eye, and a diagonal line of orange paint, carefully applied across

the pupil of each eye, creates reflections of light (Fig. 11). A similar

technique was observed on Self-Portrait, ‘les misérables’ (1888; Van

Gogh Museum, Amsterdam): “…after the eye was outlined in blue, brown,

black, and flesh colors and the paint had dried, a very dry brush

lightly loaded with red was delicately dragged across the lid,

depositing color only on the most elevated ridges of the fabric and

paint. Gauguin thus created reflected light in the shadow and a subtle color vibration around the eye.”8VJirat-Wasiutyński and Newton, Technique and Meaning in the Paintings of Paul Gauguin, 112. He produced a similar vibration on the Nelson-Atkins painting when he disrupted the blue outline along the

proper left shoulder and arm with dabs of bright red paint.

Fig. 11. Photomicrograph of the proper right eye and cheek, Faaturuma (Melancholic) (1891)

Fig. 11. Photomicrograph of the proper right eye and cheek, Faaturuma (Melancholic) (1891)

Fig. 12. Reflected infrared digital photograph of Faaturuma (Melancholic) (1891)

Fig. 12. Reflected infrared digital photograph of Faaturuma (Melancholic) (1891)

In the final stages of painting he strengthened many of the blue

outlines, such as the curving edge of the lower right side of the dress. The blue

outlines are prominent with infrared reflectography and reveal some repositioning of the proper right foot, folds of the dress, and dress hem (Fig. 12). Many of the blue lines as well as more substantial compositional changes are evident in the radiographX-ray radiography (also referred to as x-radiography or radiography): Radiography is an examination tool analogous to the use of X-rays in medicine whereby denser components of a painted composition can be recorded as an inverted shadow image cast on film or a digital X-ray imaging plate from a source such as an X-ray tube. The method has been used for more than a century and is most effective with dense pigments incorporating metallic elements such as lead or zinc. It can reveal artist changes, underlying compositions, and information concerning the artwork’s construction and condition. The resulting image is called an x-radiograph or radiograph. It differs from the uses of X-ray spectrometry in being dependent on the density of the paint to absorb X-rays before they reach the film or image plate and being non-specific as to which elements are responsible for the resulting shadow image. of Faaturuma. A radio-dense shape with a rippled edge beside the sitter’s foot was eventually covered by brown paint (Fig. 13).9See radiograph no. 455, NAMA conservation file, no. 38-5. In addition, over the course of painting, Gauguin reduced a larger section of hair at the proper right shoulder, repositioned the sitter’s profile and head at the upper left, and modified the shape of her collar (Fig. 14). The radiograph and reflected infrared digital photographreflected infrared digital photograph: An infrared image produced in the 700–1000 nanometer range, typically captured using an infrared-modified digital camera. See infrared photography. show a dark form beneath the proper right fingertips confirming that the arm of the chair was in place before the sitter’s hand was painted.10This shape is more easily visible with the Hamamatsu vidicon camera, which has a longer wavelength range. Two pentimentipentimento (pl: pentimenti): A change to the composition made by the artist that is visible on the paint surface. Often with time, pentimenti become more visible as the upper layers of paint become more transparent with age. Italian for "repentance" or "a change of mind."

indicate some additional reworking of the composition: the brown

paint of the floor partially covers the dress on the center left,

cropping it by approximately 2 centimeters, and the top of the proper

right hand was raised slightly.

Fig. 13. Detail of radiograph, Faaturuma (Melancholic) (1891)

Fig. 13. Detail of radiograph, Faaturuma (Melancholic) (1891)

Fig. 14. Radiograph of Faaturuma (Melancholic) (1891) with red annotations indicating shapes no longer visible on the paint surface and blue annotations indicating the position of elements in the final composition

Fig. 14. Radiograph of Faaturuma (Melancholic) (1891) with red annotations indicating shapes no longer visible on the paint surface and blue annotations indicating the position of elements in the final composition

The painting is in good condition overall with only a small amount of retouchingretouching: Paint application by a conservator or restorer to cover losses and unify the original composition. Retouching is an aspect of conservation treatment that is aesthetic in nature and that differs from more limited procedures undertaken solely to stabilize original material. Sometimes referred to as inpainting or retouch. present, mainly on the edges of the painting. While there is no indication of substantial color fading at the outermost edges, for example beneath the paper tape where the paint has been protected from light exposure, Gauguin’s palette during this period included red lakes that would be susceptible to fading. A small amount of traction crackingtraction cracks: Also known as drying cracks, these are formed as the paint dries. They are usually the result of a “lean” paint with a small percentage of oil drying faster than an underlying “fat” paint layer with a higher percentage of oil. The quick drying of the top layer causes the paint layer to shrink and crack. is evident on the lower left floor. Residues of yellowed varnish are visible in the paint interstices with magnification. A discolored natural resin varnish was removed during the 1988 treatment, and a synthetic varnish was applied in such a way as to impart a soft, matte, “waxed” look to the painting, in keeping with the artist’s varnish preferences.11Scott Heffley, March 22, 1988, treatment report, NAMA conservation file, no. 38-5. The varnish technique followed recommendations presented by Carol Christensen, “Surface Coatings for Paintings by Gauguin,” AIC Preprints. American Institute for Conservation 14th Annual Meeting, Chicago (Washington DC: American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works, 1986), 150.

Notes

-

Fiber identification was completed using a Zeiss Aus Jena microscope. See examination report by Scott Heffley, February 22, 1988, NAMA conservation file, no. 38-5.

-

For other examples of cotton supports used by Gauguin, see Carol Christensen, “The Painting Materials and Technique of Paul Gauguin,” Studies in the History of Art, 41 (National Gallery of Art, Washington DC: University Press of New England, 1993), 68–69. Vojtêch Jirat-Wasiutyński and H. Travers Newton Jr., Technique and Meaning in the Paintings of Paul Gauguin (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 156. Van Gogh’s Studio Practice, ed. Marije Vellekoop, Muriel Geldolf, Ella Hendriks, Leo Jansen, and Alberto de Tagle (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), 368. Kristin Hoermann Lister, “Gauguin, Cat. 28, Te burao (The Hibiscus Tree) (1923.308): Technical Study,” in Gauguin Paintings, Sculpture, and Graphic Works at the Art Institute of Chicago, ed. Gloria Groom and Genevieve Westerby (Art Institute of Chicago, 2016), para. 15, https://publications.artic.edu/gauguin/reader/gauguinart/section/140265/p-140265-15.

-

A wooden strip extends the top edge of Polynesian Woman with Children (1880; Art Institute of Chicago). See Kristin Hoermann Lister, “Gauguin, Cat. 122, Polynesian Woman with Children (1927.460): Technical Study,” in Gauguin Paintings, Sculpture, and Graphic Works at the Art Institute of Chicago, para. 28, https://publications.artic.edu/gauguin/reader/gauguinart/section/140482/p-140482-28.

-

The no. 30 paysage (basse) standard-format stretcher measures 91.8 x 67.5 centimeters. See Anthea Callen, The Art of Impressionism: Painting Technique and the Making of Modernity (London: Yale University Press, 2000), 15.

-

During his first trip to Tahiti, Gauguin began to prepare his own canvases. See Colta Feller Ives, Susan Alyson Stein, Charlotte Hale, and Marjorie Shelley, The Lure of the Exotic: Gauguin in New York Collections (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2002), 191.

-

VJirat-Wasiutyński and Newton, Technique and Meaning in the Paintings of Paul Gauguin, 112. The authors observed a “…fuzzy texture of the painting [1888; Self-Portrait, ‘les misérables,' Van Gogh Museum]…in which the fibers of the canvas, possibly roughed up before application of the paint, were encouraged to stand out and hold tiny peaks of color.” It is possible that a similar sanding or scraping of the canvas caused the fibers to lift, and this effect remains visible in thinly painted areas of Faaturuma. Another example is described in Kristin Hoermann Lister, “Gauguin, Cat. 50, Merahi metua no Tehamana (Tehamana Has Many Parents or The Ancestors of Tehamana) (1980.613): Technical Study,” in Gauguin Paintings, Sculpture, and Graphic Works at the Art Institute of Chicago, para. 25, https://publications.artic.edu/gauguin/reader/gauguinart/section/140288/p-140288-25.

-

Helmut Schweppe and Heinz Roosen-Runge, “Carmine—Cochineal Carmine and Kermes Carmine,” in Artists’ Pigments: A Handbook of their History and Characteristics, ed. Robert L. Feller (Washington DC: National Gallery of Art, 1986), 1:273.

-

VJirat-Wasiutyński and Newton, Technique and Meaning in the Paintings of Paul Gauguin, 112.

-

See radiograph no. 455, NAMA conservation file, no. 38-5.

-

This shape is more easily viewed with the Hamamatsu vidicon camera, which has a longer wavelength range.

-

Scott Heffley, March 22, 1988, treatment report, NAMA conservation file, no. 38-5. The varnish technique followed recommendations presented by Carol Christensen, “Surface Coatings for Paintings by Gauguin,” AIC Preprints. American Institute for Conservation 14th Annual Meeting, Chicago (Washington DC: American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works, 1986), 150.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Paul Gauguin, Faaturuma (Melancholic), 1891,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.716.4033

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Paul Gauguin, Faaturuma (Melancholic), 1891,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.716.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Paul Gauguin, Faaturuma (Melancholic), 1891,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.716.4033

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Paul Gauguin, Faaturuma (Melancholic), 1891,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.716.4033.

Paul Gauguin (1848–1903), Tahiti and Paris, 1891–no later than September 29, 1901 [1];

Purchased from Gauguin by George-Daniel de Monfreid (1856–1929), Paris, by September 29, 1901–December 21, 1901 [2];

Purchased from de Monfreid by Ambroise Vollard (1866–1939), Paris, Stockbook B, no. 3330, as Femme en rouge dans un fauteuil, and no. 4506, Femme assise sur un fauteuil, December 21, 1901–at least March 15, 1912 [3];

Probably purchased from Vollard by Johann Erwin Wolfensberger (1873–1944), Zurich, ca. spring 1912–at least September 15, 1928 [4];

Probably purchased from Wolfensberger through Justin Kurt Thannhauser (1892–1976), Berlin, by Josef Stransky (1872–1936), New York, ca. October 1928-March 6, 1936 [5];

Stransky estate, New York, 1936-January 4, 1938 [6];

Purchased from the Stransky estate through Wildenstein, New York, by The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1938.

Notes

[1] Some scholars believe that Faaturuma was bought in by Gauguin at the following sale: Vente de tableaux et dessins par Paul Gauguin, Hôtel Drouot, Paris, February 18, 1895, no. 30, as Faturuma [sic]; see Richard Brettell et al., The Art of Paul Gauguin, exh. cat. (Washington: National Gallery of Art, 1988), 228. Others believe Te Faaturuma (Worcester Art Museum) is more likely to have been included in this sale as no. 30; see Jonathan Pascoe Pratt, “Ambroise Vollard: Dealer and Publisher 1893–1900” (PhD diss., The Courtauld Institute of Art, 2006), 77. The Wildenstein Institute and Worcester Art Museum both agree with Pratt; see letter from Sylvie Crussard, Wildenstein Institute, to Meghan Gray and Simon Kelly, NAMA, November 6, 2009; e-mail from Sylvie Crussard, Wildenstein Institute, to Brigid Boyle, NAMA, August 24, 2015; and e-mail from Karysa Norris, Curatorial Assistant, Worcester Art Museum, to Brigid Boyle, NAMA, November 16, 2015, NAMA curatorial files.

On June 28, 1895, Gauguin departed Marseille for Tahiti, leaving behind the paintings from his first Tahitian trip, including Faaturuma. He likely entrusted them to George-Daniel de Monfreid with instructions to sell them. De Monfreid purchased Faaturuma from Gauguin sometime between June 1895 and September 1901.

[2] Because de Monfreid was born in New York, he wanted his first name to be spelled the American way without the “S”: “George.”

In a letter dated September 29, 1901, de Monfreid informs Vollard that an amateur collector has expressed interest in purchasing Faaturuma from him. Since Vollard “avez la priorité sur d’autres” [has priority over others] as Gauguin’s agent, de Monfreid gives him the option of purchasing Faaturuma himself; see letter from George-Daniel de Monfreid to Ambroise Vollard, September 29, 1901, Harry Ransom Center, Carlton Lake Collection, Container 189.10. Vollard agreed to purchase the painting; see letter from Ambroise Vollard to George-Daniel de Monfreid, October 2, 1901, Getty Research Institute, Miscellaneous Papers Regarding Ambroise Vollard (1890–1939), Series I, Box 1, Folder 18. He completed his purchase on December 21, 1901; see letter from Ambroise Vollard to George-Daniel de Monfreid, December 23, 1901, Getty Research Institute, Miscellaneous Papers Regarding Ambroise Vollard (1890–1939), Series I, Box 1, Folder 19.

Bengt Danielsson claims erroneously that Vollard purchased Faaturuma as early as 1893, after it was exhibited at the Galeries Durand-Ruel; see Gauguin in the South Seas, trans. Reginald Spink (1964; Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1966), 155.

[3] Faaturuma remained in Vollard’s possession until at least March 15, 1912, when Vollard shipped the painting to Zurich for the Ausstellung von Werken Paul Gauguin’s im Kunstsalon Wolfsberg (March 17–April 15, 1912); see Musée d’Orsay, Paris, Documentation Center, Fonds Vollard, Ms 421 (4,13), Registre consignant des expéditions, avec adresses des destinataires, du 33 mai 1907 au 15 février 1923, fº 46-47.

Stockbook B is preserved at the Musée d’Orsay, Paris, Documentation Center, Fonds Vollard, Ms 421 (4,5), Registre des entrées et sorties de juin 1904 à décembre 1907 avec des achats aux artistes Gauguin, Redon, Cézanne, Valtat, Denis, Cassatt, K. X. Roussel. There is also a glass plate of Faaturuma preserved at the Musée d’Orsay, Paris, Documentation Center, Archives photographiques du fonds Vollard, ODO 1996-56-3722, which bears the stock number 4506.

[4] After the close of the Ausstellung von Werken Paul Gauguin’s im Kunstsalon Wolfsberg, an exhibition of works loaned by Ambroise Vollard, Johann Erwin Wolfensberger (owner of the Kunstsalon Wolfsberg) purchased a Gauguin painting from Vollard for 9000 francs, which he paid in two installments. The first installment of 2000 francs was received on June 18, 1912 and the second installment of 7000 francs was received on July 12, 1912; see Musée d’Orsay, Paris, Documentation Center, Fonds Vollard, Ms 421 (5,8), Agenda de bureau pour 1912, p. 112 and 131. Vollard’s agenda book does not identify the painting by title or stock number, but Lukas Gloor believes the painting Wolfensberger purchased was Faaturuma; see Raphaël Bouvier and Martin Schwander, eds., Paul Gauguin, exh. cat. (Basel: Beyeler Museum, 2015), 189. As Gloor points out, Faaturuma disappears from Vollard’s books after the spring of 1912; see e-mail from Lukas Gloor, Director, Sammlung E. G. Bührle, to Brigid Boyle, NAMA, July 23, 2015, NAMA curatorial files.

Faaturuma remained in Wolfensberger’s collection until at least September 15, 1928, when the Kunsthalle Basel returned it to him after the close of their exhibition, Paul Gauguin, 1848–1903 (July 1–September 9, 1928); see letter from the Kunsthalle Basel to J. E. Wolfensberger, September 15, 1928, Staatsarchiv des Kanton Basel-Stadt, Basel, Pa 888a N6 (1) 239.

The Wildenstein catalogue raisonné of 1964 tentatively suggests that a certain “Dr. Hahnloser, Zurich” owned Faaturuma between Vollard and Wolfensberger. The best-known collectors fitting this description are Arthur Hahnloser (1870–1936) and his brother Emil Hahnloser (1874–1940). However, neither began collecting works by Gauguin until after World War I. As Lukas Gloor notes, “an acquisition by Arthur Hahnloser of Faaturuma in 1912 would…have been totally out of sync with Arthur’s collecting behaviour at that time” and “an acquisition by Emil Hahnloser of Faaturuma in 1912 would have been a totally isolated affair”; see e-mail from Lukas Gloor, Director, Sammlung E. G. Bührle, to Brigid Boyle, NAMA, July 23, 2015, NAMA curatorial files.

[5] The Wildenstein catalogue raisonné of 1964 claims that Justin K. Thannhauser owned Faaturuma between Wolfensberger and Stransky, but there is no documentary evidence to support this. Shortly after receiving Faaturuma back from the Kunsthalle Basel in September 1928, Wolfensberger presumably shipped it to Berlin for the exhibition Paul Gauguin, 1848–1903 (October 1928) at the Galerien Thannhauser. Sylvie Crussard believes that Justin K. Thannhauser acted as an intermediary for Wolfensberger when he sold Faaturuma; see e-mail from Sylvie Crussard, Wildenstein Institute, to Brigid Boyle, NAMA, August 24, 2015, NAMA curatorial files. This was not without precedent: in 1920, Stransky purchased Gauguin’s A Farm in Brittany (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 54.143.2) from Thannhauser, who had it on consignment from a private collector. However, Dr. Günter Herzog found no reference to Faaturuma in the archives of the Galerien Thannhauser, Zentralarchiv des internationalen Kunsthandels, Cologne; see e-mail from Günter Herzog to Brigid Boyle, NAMA, August 12, 2015, NAMA curatorial files.

Stransky definitely owned Faaturuma by May 16, 1931, when his collection was featured in Art News. Mark Aitken, Stransky’s great-nephew, does not know how Faaturuma came into Stransky’s possession, nor does he believe any documentation of Stransky’s collection has survived; see phone conversation between Mark Aitken and Brigid Boyle, NAMA, June 16, 2015, NAMA curatorial files.

[6] When Stransky died in 1936, married but childless, Faaturuma passed to his estate. Wildenstein negotiated with the estate on behalf of the Nelson-Atkins; see Trustees’ Meeting, December 10, 1937, NAMA curatorial files.

Preparatory Work

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Paul Gauguin, Faaturuma (Melancholic), 1891,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.716.4033

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Paul Gauguin, Faaturuma (Melancholic), 1891,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.716.4033.

Paul Gauguin, Hand on the Armrest of a Chair, 1891, pencil on paper, 6 11/16 x 4 5/16 in. (17.0 x 11.0 cm), originally from the Carnet de Tahiti, p. 31 recto (later dismantled), location unknown, illustrated in Elda Fezzi and Fiorella Minervino, “Noa Noa” e il Primo Viaggio a Tahiti di Gauguin (Milan: Rizzoli, 1974), 97.

Paul Gauguin, Self-Portrait; Sketch for “Faaturuma,” ca. 1891, watercolor, crayon and ink on paper, 6 x 7 7/8 in. (15.2 x 20.0 cm), The Triton Foundation, The Netherlands.

Paul Gauguin, Seated Tahitian Woman: Study for “Faaturuma (Reverie),” 1891, charcoal on tan wove paper, 18 7/8 in. x 21 7/8 (48.0 x 55.5 cm), The Art Institute of Chicago.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Paul Gauguin, Faaturuma (Melancholic), 1891,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.716.4033

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Paul Gauguin, Faaturuma (Melancholic), 1891,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.716.4033.

Exposition d’Œuvres récentes de Paul Gauguin, Galeries Durand-Ruel, Paris, November 9–25, 1893, no. 28, as Mélancolique.

Peintures, Pastels, Aquarelles, Dessins, Sculptures, Céramiques, Objets d’Art, Lithographies, etc., Société des Beaux-Arts de Béziers, Salle Berlioz, rue Solférino, April–May 1901, no. 52, as Tahitienne au rocking-chair.

Exposition Paul Gauguin, Galerie Ambroise Vollard, Paris, November 4–28, 1903, no. 31, as Rêverie.

Salon d’Automne: 4ème exposition; Œuvres de Gauguin, Grand Palais, Paris, October 5–November 15, 1906, no. 72, as Rêveuse.

Galerie Miethke, März–April 1907, Galerie Miethke, Vienna, Austria, March 15–April 28, 1907, no. 65, as Melancholie.

Tavaszi Kiállítás: Gauguin, Cézanne stb. Müvei, Nemzeti Szalon, Budapest, May 1907, no. 8, as Melancholia.

Possibly Exposition d’Œuvres de Paul Gauguin, Galerie Ambroise Vollard, Paris, April 25–May 14, 1910, unnumbered, as Femme dans un fauteuil.

Manet and the Post-Impressionists, Grafton Galleries, London, November 8, 1910–January 15, 1911, no. 45, as Réverie [sic].

Ausstellung von Werken Paul Gauguin’s im Kunstsalon Wolfsberg, Kunstsalon Wolfsberg, Zurich, March 17–April 15, 1912, no. 5127, as La Rêverie. Jeune fille dans un fauteuil. Paysage de Tahiti.

Ausstellung von Werken aus dem Besitz von Mitgliedern der Vereinigung Zürcher Kunstfreunde, Kunsthaus Zürich, September 3–October 2, 1927, no. 92, as Träumerei.

Paul Gauguin, 1848–1903, Kunsthalle Basel, July 1–September 9, 1928, no. 77, as Tahitierin [sic] im Schaukelstuhl (Rêverie).

Paul Gauguin: 1848–1903, Galerien Thannhauser, Berlin, October 1928, no. 52, as Tahitanerin [sic].

First Loan Exhibition: Cézanne, Gauguin, Seurat, Van Gogh, Museum of Modern Art, New York, November 7–December 7, 1929, no. 38, as Reverie.

The Stransky Collection of Modern Art, Worcester Art Museum, Worcester, MA, opened January 6, 1933, no cat.

Paul Gauguin, 1848–1903: A Retrospective Loan Exhibition for the Benefit of les Amis de Paul Gauguin and the Penn Normal Industrial and Architectural School, Wildenstein, New York, March 20–April 18, 1936, no. 21, as Reverie.

Paul Gauguin, 1848–1903, Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge, MA, May 1–21, 1936, no. 19, as Reverie.

Paul Gauguin, 1848–1903: A Retrospective Exhibition of his Paintings, Baltimore Museum of Art, May 24–June 5, 1936, no. 13, as Reverie.

“Collection of a Collector”: Modern French Paintings from Ingres to Matisse (The Private Collection of the Late Josef Stransky), Wildenstein, London, July 1936, no. 25, as Rêverie.

La vie ardente de Gauguin, Gazette des Beaux-Arts, Paris, November 1936, no. 113, as La Rêverie.

Trends in European Painting from the XIIIth to the XXth Century, Art Gallery of Toronto, Canada, October 15–November 15, 1937, no. 40, as Reverie.

Five Years of Collecting, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, December 4–11, 1938, no cat.

French Painting from David to Toulouse-Lautrec, THe Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, February 6–March 26, 1941, no. 51, as Reverie.

A Loan Exhibition of Paul Gauguin for the Benefit of the New York Infirmary, Wildenstein, New York, April 3–May 4, 1946, no. 14, as Reverie.

Gauguin: Exposition du centenaire, Musée de l’Orangerie des Tuileries, Paris, July 1949, no. 26, as Rêverie.

Masterpieces from Museums and Private Collections: Jubilee Loan Exhibition, 1901–1951, Wildenstein, New York, November 8–December 15, 1951, no. 53, as Rêverie.

Twenty Years of Collecting, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, December 11–31, 1953, no cat.

Paul Gauguin: His Place in the Meeting of East and West, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, March 27–April 25, 1954, no. 19, as Reverie.

The Two Sides of the Medal: French Painting from Gérôme to Gauguin, Detroit Institute of Arts, September 28–October 31, 1954, no. 109, as Rêverie.

Gauguin: Loan Exhibition for the Benefit of the Citizens’ Committee for Children of New York City, Inc., Wildenstein, New York, April 5–May 5, 1956, no. 25, as Reverie.

Gauguin: Paintings, Drawings, Prints, Sculpture, Art Institute of Chicago, February 12–March 29, 1959; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, April 23–May 31, 1959, no. 29, as Reverie (Melancolique) [sic].

Man: Glory, Jest, and Riddle; A Survey of the Human Form through the Ages, California Palace of the Legion of Honor, San Francisco, November 10, 1964–January 3, 1965, no. 183, as Reverie.

La revue blanche: Paris in the Days of Post-Impressionism and Symbolism, Wildenstein, New York, November 17–December 31, 1983, unnumbered, as La Rêverie.

The Art of Paul Gauguin, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, May 1–July 31, 1988; The Art Institute of Chicago, September 17–December 11, 1988; Grand Palais, Paris, January 10–April 24, 1989, no. 126, as Faaturuma (Boudeuse).

Impressionism: Selections From Five American Museums, The Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, November 4–December 31, 1989; The Minneapolis Institute of Arts, January 27–March 25, 1990; The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, April 21–June 17, 1990; The Saint Louis Art Museum, July 14–September 9, 1990; The Toledo Museum of Art, September 30–November 25, 1990, no. 29, as Faaturuma (Melancholic).

The Artist and the Camera: Degas to Picasso, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, October 2, 1999–January 4, 2000; Dallas Museum of Art, February 1–May 7, 2000; Fundación del Museo Guggenheim, Bilbao, June 12–September 10, 2000, no. 123 (Dallas only), as Melancholic (Faaturuma).

Vincent van Gogh and the Painters of the Petit Boulevard, Saint Louis Art Museum, February 17–May 13, 2001; Städelsches Kunstinstitut, Frankfurt, June 8–September 2, 2001, unnumbered, as Faaturuma.

Expressive!, Fondation Beyeler, Basel, March 30–August 10, 2003, unnumbered, as Melancholic and Faaturuma (Boudeuse).

Gauguin, Polynesia, Ny Carlsberg Glypotek, Copenhagen, September 24–December 31, 2011; Seattle Art Museum, February 9–April 29, 2012, no. 166 (Seattle only), as Faaturuma (Melancholic).

Expressionism in Germany and France: From Van Gogh to Kandinsky, Kunsthaus Zürich, February 7–May 11, 2014; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, June 8–September 14, 2014; Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, October 6, 2014–January 25, 2015, unnumbered (Montreal only), as Melancholic.

Paul Gauguin, Fondation Beyeler, Basel, February 8–June 28, 2015, unnumbered, as Faaturuma / Boudeuse (The Brooding Woman).

Gauguin: Portraits, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, May 24–September 8, 2019; The Credit Suisse Exhibition: Gauguin Portraits, National Gallery, London, October 7, 2019–January 26, 2020, no. 78, as Melancholic (Faaturuma).

References

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Paul Gauguin, Faaturuma (Melancholic), 1891,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.716.4033

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Paul Gauguin, Faaturuma (Melancholic), 1891,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.716.4033.

Exposition d’Œuvres récentes de Paul Gauguin, exh. cat. (Paris: E. Moreau et Cie, 1893), 19, as Faturuma [sic] (Boudeuse) or Mélancolique.

Possibly Vente de Tableaux et Dessins par Paul Gauguin, Artiste Peintre (Paris: G. Camproger, 1895), 10, as Faturuma [sic].

Possibly “Tableaux et Dessins par Paul Gauguin,” Gazette de l’Hôtel Drouot 5, nos. 61–62 (March 2–3, 1895): unpaginated, as Faturuma [sic] (La boudeuse).

Catalogue des Peintures, Pastels, Aquarelles, Dessins, Sculptures, Céramiques, Objets d’Arts, Lithographies, etc. (Béziers, France: Imprimerie de l’Hérault, 1901), 15, as Tahitienne au rocking-chair.

Exposition Paul Gauguin, exh. cat. (Paris: Galerie Ambroise Vollard, [1903]), unpaginated, as Rêverie.

Catalogue des Ouvrages de Peinture, Sculpture, Dessin, Gravure, Architecture et Art décoratif, exh. cat. (Paris: Compagnie Française des Papiers-Monnaie, 1906), 194, as Rêveuse.

Jean de Rotonchamp [Jean Brouillon], Paul Gauguin, 1848–1903 (Paris: Édouard Druet, 1906), 120, 135, as Mélancolique.

Galerie Miethke, März–April 1907, exh. cat. (Vienna: Galerie Miethke, [1907]), 18, as Melancholie.

Tavaszi Kiállitás: Gauguin, Cézanne stb. Müvei, exh. cat. (Budapest: Légrády Testvérek, 1907), 5, as Melancholia.

Possibly Exposition d’Œuvres de Paul Gauguin, exh. cat. (Paris: Galerie A. Vollard, [1910]), unpaginated, as Femme dans un fauteuil.

Grafton Galleries, Manet and the Post-Impressionists, exh. cat. (London: Ballantyne, [1910]), 19n1, as Réverie [sic].

Possibly H[ippolyte] Mireur, Dictionnaire des Ventes d’Art Faites en France et à l’Étranger Pendant les XVIIIme et XIXme Siècles, vol. 3 (Paris: Maison d’Éditions d’Œuvres Artistiques, 1911), 263, as Faturuma (La boudeuse).

Ausstellung von Werken Paul Gauguin’s im Kunstsalon Wolfsberg, exh. cat. (Zurich: Kunstsalon Wolfsberg, 1912), (repro.), as La Rêverie. Jeune fille dans un fauteuil. Paysage de Tahiti.

Charles Morice, Paul Gauguin (Paris: H[enri] Floury, 1919), 171n1, as Faturuma [sic] (Boudeuse) or Mélancolique.

Kunsthaus Zürich, Ausstellung von Werken aus dem Besitz von Mitgliedern der Vereinigung Zürcher Kunstfreunde, exh. cat. (Zurich: Buchdruckerei Berichthaus Zürich, 1927), 14, as Träumerei.

Paul Gauguin, 1848–1903, exh. cat. (Basel: Kunsthalle Basel, 1928), 21, as Tahitierin im Schaukelstuhl (Rêverie).

Paul Gauguin, 1848–1903, exh. cat. (Berlin: Galerien Thannhauser, 1928), 11, as Tahitanerin [sic].

The Museum of Modern Art, First Loan Exhibition: Cézanne, Gauguin, Seurat, Van Gogh, exh. cat. (1929; repr., [New York]: Arno Press, 1972), 39, (repro.) as Reverie.

Edward Alden Jewell, “The New Museum of Modern Art Opens: A Superb Showing of Work by Four Pioneers; Cezanne, Gauguin, Van Gogh and Seurat; Contemporary Frenchmen,” New York Times 79, no. 26,223 (November 10, 1929): 14X, (repro.), as Reverie.

Possibly F[elipe] Cossío del Pomar, Arte y Vida de Pablo Gauguin (Escuela Sintetista) (Paris: Léon Sánchez Cuesta, 1930), 226, as Faatourouma (Enfurruñada).

Ralph Flint, “The Private Collection of Josef Stransky,” Art News 29, no. 33 (May 16, 1931): 87–88, 105, (repro.), as Reverie, Femme á [sic] la Robe Rouge.

R[eginald] H[oward] Wilenski, French Painting (Boston: Hale, Cushman and Flint, 1931), 289, as Reverie (Tahitian girl in rocking-chair).

P[erry] B. C[ott], “The Stransky Collection of Modern Art,” Bulletin of the Worcester Art Museum 23, no. 4 (Winter 1933): 149, 154, 156, (repro.), as Rêverie, Femme à la Robe Rouge.

Edward W. Forbes, [“Report of the Fogg Art Museum, 1935–36”],Annual Report (Fogg Art Museum), nos. 1935–1936 (1935–1936): 25, as Reverie.

Paul Gauguin, 1848–1903: A Retrospective Loan Exhibition for the Benefit of les Amis de Paul Gauguin and the Penn Normal Industrial and Agricultural School, exh. cat. (New York: Wildenstein, 1936), 31, 48, (repro.), as Reverie.

Edward Alden Jewell, “Gauguin Paintings Shown at Preview: 49 Canvases Represent All Principal Phases of French Artist’s Career; Scrapbooks Also on View; Manuscript of ‘Noa Noa,’ 204 Pages, and Illustrations of Book in Exhibition,” New York Times 85, no. 28,545 (March 20, 1936): 27, as Reverie.

“Gauguin in Retrospect: Loan Exhibition at Wildenstein’s Covers Period from 1875 to His Death in 1903,” New York Times 85, no. 28,547 (March 22, 1936): 8X, as Reverie.

Paul Gauguin, 1848–1903, exh.cat. (New York: Harbor Press, 1936), 29–30, 49, (repro.), as Reverie.

Paul Gauguin 1848–1903: A Retrospective Exhibition of His Paintings, exh. cat. (Baltimore: Baltimore Museum of Art, 1936), unpaginated, (repro.), as Reverie.

“Collection of a Collector”: Modern French Paintings from Ingres to Matisse (The Private Collection of the Late Josef Stransky), exh. cat. ([London]: Wildenstein, 1936), unpaginated, as Rêverie.

Raymond Cogniat, La Vie Ardente de Paul Gauguin, exh. cat. (Paris: Gazette des Beaux-Arts, [1936]), 65, 82, (repro.), as La Rêverie.

Paul Gauguin, 1848–1903: An Exhibition of Original Work and Colour Prints and of Polynesian Art, exh. cat. (Edinburgh: Whytock and Reid, 1937), 8, as Rêverie.

Trends in European Painting from the XIIIth to the XXth Century, exh. cat. ([Toronto]: Art Gallery of Toronto, [1937]), 40, as Reverie.

“A Fine Addition to the Gallery,” Kansas City Star 59, no. 38 (October 23, 1938): D, as Reverie.

“Kansas City Gets a Gauguin,” New York Times 88, no. 29,493 (October 24, 1938): 20, as Reverie.

“‘Reverie’: A Famous Gauguin Just Added to the Kansas City Collections,” Art News 37, no. 5 (October 29, 1938): 5–6, (repro.), as Reverie.

“Important Gauguin Goes to Missouri Museum,” Art Digest 13, no. 3 (November 1, 1938): 13, (repro.), as Reverie.

“Masterpiece of the Month,” “Friends of Art,” and “Radio Broadcasts,” News Flashes (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) 5, no. 1 (November 1, 1938): 2–3, as Reverie.

H. C. H., “Art and Artists: Abstractions Art to Art What Miss Stein Is to Prose,” Kansas City Star 59, no. 48 (November 4, 1938): 19, as Reverie.

“‘Visit Your Gallery Week’ Designated December 4–11,” Kansas City Journal 85, no. 66 (November 27, 1938): 36, as Reverie.

“Five Years of Collecting,” News Flashes (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) 5, no. 2 (December 1, 1938): 1, as Reverie.

“Footnotes,” Lincoln (NE) Evening State Journal (December 2, 1938): 8.

Paul Gardner, “Kansas City: Jubilee and an Acquisition,” Art News 37, no. 10 (December 3, 1938): 19, as Rêverie.

“A Good Start on Art: Paintings of Nelson Gallery Are Described by Advisor,” Kansas City Times 101, no. 299 (December 15, 1938): 6, as Reverie.

“Kansas City’s Nelson Gallery Celebrates its Fifth Anniversary,” Art Digest 13, no. 6 (December 15, 1938): 7, as Reverie.

H. C. H., “Sale of Hearst’s Collection Heads the Art News for 1938,” Kansas City Star 59, no. 104 (December 30, 1938): 6, as Reverie.

John Rewald, Gauguin, ed. André Gloeckner (1938; repr., New York: Hyperion Press, 1949), 112, 167, (repro.), as Rêverie.

“Events Here and There,” New York Times 88, no. 29,562 (January 1, 1939): 10X, as Reverie.

“Radio Programs,” News Flashes (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) 6, no. 1 (November 1939): 3.

“Her Master’s Life to be Dramatized,” Kansas City Star 60, no. 56 (November 12, 1939): 4D, (repro.), as Reverie.

“Collector’s Progress,” Kansas City Times 103, no. 3 (January 3, 1940): C.

R[eginald] H[oward] Wilenski, Modern French Painters (New York: Reynal and Hitchcock, [1940]), 131, 131n1, 351, as Rêverie (Mélancolique).

Harry B. Wehle, “French Painting from David to Toulouse-Lautrec: Loans from French and American Museums and Collections,” Bulletin of the Metropolitan Museum of Art 36, no. 2 (February 1941): 34, as Reverie.

“Museums, Art Associations, Other Organizations,” in “Covering Art Activities during July 1938–July 1941,” American Art Annual 35 (1941): 268, as Reverie.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, French Painting from David to Toulouse-Lautrec: Loans from French and American Museums and Collections, exh. cat. (New York: George Grady Press, 1941), 17, (repro.) as Reverie.

The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, The William Rockhill Nelson Collection, 2nd ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, [1941]), 41, 55, 168, (repro.), as Reverie.

Regina Shoolman and Charles E. Slatkin, The Enjoyment of Art in America: A Survey of the Permanent Collections of Painting, Sculpture, Ceramics and Decorative Arts in American and Canadian Museums; Being an Introduction to the Masterpieces of Art from Prehistoric to Modern Times (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1942), 561, 623, 780, 785, (repro.), as Reverie.

Art News 42, no. 4 (April 1–14, 1943): 5, 17, (repro.), as Rêverie and Reverie.

“Nelson Gallery Celebrates First Decade,” Art Digest 18, no. 6 (December 15, 1943): 6, as Reverie.

Ethlyne Jackson, “Museum Record: Kansas City’s Tenth Birthday,” Art News 42, no. 15 (December 15–31, 1943): 16, as Réverie [sic].

“Loans to Others,” Gallery News (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) 12, no. 10 (Summer 1946): 4, as Reverie.

A Loan Exhibition of Paul Gauguin for the Benefit of the New York Infirmary, exh. cat. (New York: Wildenstein, 1946), 28, 64, (repro.), as Reverie.

Raymond Cogniat, Gauguin (Paris: Éditions Pierre Tisné, 1947), 51, (repro.), as Dreaming.

Fred G. Hoffherr et al., eds., Book of Friendship (New York: Maison de France, 1947), (repro.), as Reverie.

Dorothy Adlow, “Art in Kansas City: Music and Theaters; Exhibitions in San Francisco; Masterpieces of Many Schools To Be Seen in Nelson Gallery,” Christian Science Monitor 40, no. 197 (July 17, 1948): 12, as Reverie.

Maurice Malingue, Gauguin: Le Peintre et Son Œuvre (Paris: Presses de la Cité, 1948), 169, (repro.), as Rêverie.

Jean Leymarie, Gauguin: Exposition du Centenaire, exh. cat. ([Paris]: Éditions des Musées Nationaux, 1949), vi, 39, 98, (repro.), as Rêverie.

Jean Leymarie, “Musée de l’Orangerie: Exposition Gauguin,” Musées de France, no. 5 (June 1949): 112, as Rêverie.

Raymond Cogniat, “À l’Orangerie: L’Exposition Gauguin à Travers les Salles,” Arts, no. 222 (July 8, 1949): 8, as La rêverie.

Bernard Dorival, “Les Nouvelles Artistiques: Grandeur de Gauguin,” Les Nouvelles Littéraires, Artistiques et Scientifiques, no. 1142 (July 21, 1949): 7, as Rêverie.

Winifred Shields, “Gauguin Painting from Nelson Gallery in Paris Exhibition: ‘Reverie,’ a Portrait of Polynesian Wife, is Included in Retrospective Show Commemorating Centenary of Oil Masters [sic] Birth in Paris; Urge to Paint Leads to South Sea Island,” Kansas City Star 69, no. 343 (August 26, 1949): 11, as Reverie.

Denys Sutton, “The Paul Gauguin Exhibition,” Burlington Magazine 91, no. 559 (October 1949): 286n45, as Rêverie.

Alexander Watt, “The Centenary Exhibition of the Work of Gauguin,” Apollo 50, no. 296 (October 1949): 97.

Michael Sadleir, Michael Ernest Sadler (Sir Michael Sadler, K.C.S.I.), 1861–1943: A Memoir by His Son (London: Constable, 1949), 234, as Reverie.

The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, The William Rockhill Nelson Collection, 3rd ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1949), 69, (repro,), as Reverie.

Lee Van Dovski [Herbert Lewandowski], Paul Gauguin, oder die Flucht vor der Zivilisation (Olten, Switzerland: Delphi Verlag, 1950), 348, as Rêverie.

Georg Schmidt, Gauguin (Bern: Alfred Scherz Verlag, 1950), 22, 31, (repro.), as Träumerei.

Jean Loize, Les Amitiés du Peintre Georges-Daniel de Monfreid et Ses Reliques de Gauguin: De Maillol et Codet à Segalen ([Paris]: Jean Loize, 1951), 147, as Tahitienne au rocking-chair.

Masterpieces from Museums and Private Collections: Jubilee Loan Exhibition, 1901–1951, exh. cat. (New York: Wildenstein, 1951), (repro.), as Rêverie.

Winifred Shields, “The Twenty Best, a Special Exhibition at Nelson Gallery: Anniversary Will Be Observed by Showing of Paintings, Some Acquired Recently, Others Even Before the Institution Opened Two Decades Ago; Begins Next Friday,” Kansas City Star 74, no. 78 (December 4, 1953): 36, as Reverie.

Jean Cassou, Les Impressionnistes et leur époque (Paris: Cercle français d’art, 1953), 28, 60, (repro.), as Rêverie.

Die Impressionisten und Ihre Zeit (Lucerne, Switzerland: Kunstkreis Verlag, 1953), 28, (repro.), as Träumerei.

Jean Taralon, Gauguin (Paris: Éditions du chêne, 1953), 6, 11, (repro.), as La Rêverie.

Paul Gauguin, Carnet de Tahiti, ed. Bernard Dorival (Paris: Quatre Chemins-Éditart, 1954), 1:17, 22–23, 28, 59n1; 2:2r, as Rêverie.

Paul Gauguin: His Place in the Meeting of East and West, exh. cat. (Houston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1954), unpaginated, as Reverie.

The Two Sides of the Medal: French Painting from Gérôme to Gauguin, exh. cat. (Detroit: Detroit Institute of Arts, 1954), 56, 65, (repro.), as Rêverie.

Aline B. Saarinen, “The Salon and Some Rebels: Detroit Art Institute Presents Provocative Contrast in Show,” New York Times 104, no. 35,316 (October 3, 1954): X11, as Reverie.

Possibly Lawrence and Elisabeth Hanson, Noble Savage: The Life of Paul Gauguin (New York: Random House, 1955), 208, as Daydream.

Roseline Bacou, Odilon Redon, vol. 1, La Vie et l’œuvre: Point de vue de la critique au sujet de l’œuvre (Geneva: Pierre Cailler, 1956), 207n5, as La Tahitienne au rocking-chair.

Gauguin: Loan Exhibition for the Benefit of the Citizens’ Committee for Children of New York City, Inc. (New York: Wildenstein, 1956), 17, 43, (repro.), as Reverie.

R. F. C., “Una mostra di Gauguin alla galleria Wildenstein di New York,” Emporium 124, no. 740 (August 1956): 77, as Reverie.

John Rewald, Post-Impressionism: From van Gogh to Gauguin, 3rd ed. (1956; New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1978), 465–66, (repro.), as Reverie.

Robert Goldwater, Paul Gauguin (New York: Harry N. Abrams, [1957]), 102–03, (repro.), as Reverie.

Henri Perruchot, Gauguin, Tahiti (New York: Tudor, 1958), (repro.), as Rêverie.

Charles S. Kessler, “Robert Goldwater, ‘Paul Gauguin’; John Rewald, ‘Gauguin Drawings’,” College Art Journal 18, no. 3 (Spring 1959): 275–76, as Reverie.

Gauguin: Paintings, Drawings, Prints, Sculpture, exh. cat. (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 1959), 21, 41, 47, 61, (repro.), as Reverie (Mélancolique).

“Gauguin,” The Art Institute of Chicago Quarterly 53, no. 1 (February 1959): 4, as Reverie.

Edith Weigle, “Gauguin Art Display is Beautiful, Costly,” Chicago Daily Tribune 118, no. 36 (February 11, 1959): pt. 3, p. 5, as Reverie.

Ross E. Taggart, ed., Handbook of the Collections in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 4th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1959), 124, 260, (repro.), as Reverie.

Horváth Tibor, Gauguin, 1848–1903 (Budapest: Képzőművészeti Alap Kiadóvállalata, 1960), 28, 36, (repro.), as Búskomorság (Ábrándozás).

Henri Perruchot et al., Paul Gauguin: Génies et Réalités (1961; repr., Paris: Chêne, 1986), 59, 232, as Rêverie.

Henri Perruchot, La Vie de Gauguin ([Paris]: Hachette, 1961), 252, 252n1, 404, as Rêverie.

Pierre-Francis Schneeberger, Gauguin: Tahiti, trans. Karl Balser (1961; repr., Lausanne: International Art Book, 1962), 26, 40, as Träumerei.

Richard S[ampson] Field, Paul Gauguin: The Paintings of the First Voyage to Tahiti (1963; repr., New York: Garland, 1977), 304, 307, 334, (repro.), as Reverie (Melancolique) [sic].

Kuno Mittelstädt, ed., Paul Gauguin (Berlin: Henschelverlag, 1963), 14, as Träumerei.

Georges Boudaille, Gauguin (New York: Tudor, 1964), 124, 269, (repro.), as Reverie.

Bengt Danielsson, Gauguin in the South Seas, trans. Reginald Spink (1964; repr., Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1966), 155, 164.

Man: Glory, Jest, and Riddle; A Survey of the Human Form through the Ages, exh. cat. (San Francisco: Neal, Stratford and Kerr, 1964), unpaginated, as Reverie.