![]()

Paul Gauguin, Autumn in Brittany (The Willow Tree), 1889

| Artist | Paul Gauguin, French, 1848–1903 |

| Title | Autumn in Brittany (The Willow Tree) |

| Object Date | 1889 |

| Alternate and Variant Titles | L’Automne en Bretagne; Paysage de Bretagne; Le saule pleurer |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (Unframed) | 36 1/4 x 28 7/8 in. (92.1 x 73.3 cm) |

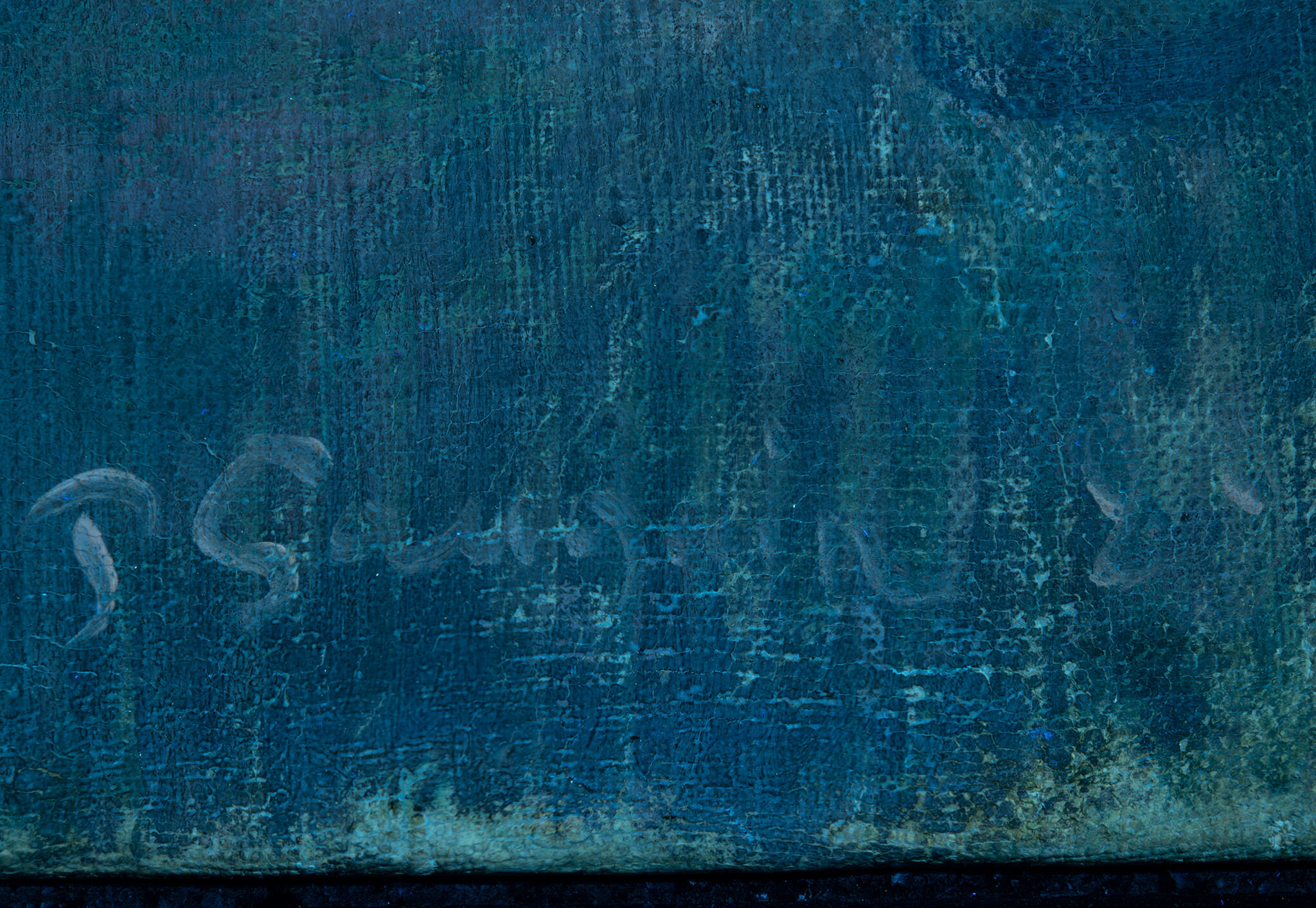

| Signature | Signed and dated: P Gauguin 89 |

| Credit Line | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Gift of Henry W. and Marion H. Bloch, 2015.13.9 |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Elizabeth C. Childs, “Paul Gauguin, Autumn in Brittany (The Willow Tree), 1889,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.714.5407.

MLA:

Childs, Elizabeth C. “Paul Gauguin, Autumn in Brittany (The Willow Tree), 1889,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.714.5407.

Brittany, the northwesternmost province of France, was a source of lasting interest and inspiration for Paul Gauguin. After first visiting the area in the summer of 1886, he found it a pragmatic choice for an artistic base, as it was a well-established artists’ colony that was extremely affordable in comparison to Paris. He was also drawn to Brittany as a remote alternative to the urban modernity of Paris (and even to the smaller city of Rouen, his residence in 1884). Further, it was attractive to him as a region that cultivated and promoted its Celtic and medieval heritage, not only in an era of competition for regional distinction in France, but also for the sake of the waves of international tourists who visited the region and supported its economy in the last decades of the nineteenth century.1A classic reference on this mythology as it informs Gauguin’s practice is Griselda Pollock and Fred Orton, “Les Donées Bretonnantes/La Prairie de la Répresentation,” Art History 3, no. 3 (September 1980): 314–44. For Gauguin, the Breton landscape offered precious solace; he wrote in 1888 that he believed that he could live there “in silent contemplation of nature, devoting myself entirely to my art.”2“Je me laisse vivre dans la muette contemplation de la nature, tout entier à mon art.” Gauguin to Émile Schuffenecker (1851–1934), Pont-Aven, late February 1888, translated and quoted in Belinda Thomson, ed., Gauguin by Himself (London: Time Warner Books, 2004), 62. In Brittany, he regarded both nature and the communities of rural workers within the broader population of the province as equally necessary to his quest for an essentialized rural experience. He wrote, “I like Brittany, I find a certain wildness and primitiveness here. When my clogs resound on this granite soil, I hear the muffled sound, dull and powerful, that I am looking for in my painting.”3“J’aime la Bretagne, j’y trouve le sauvage, le primitif. Quand mes sabots résonnent sur ce sol de granit, j’entends le ton sourd, mat et puissant que je cherche en peinture.” Gauguin to Schuffenecker, late February 1988, translated and quoted in Thomson, Gauguin by Himself, 62. This phrase, while poetic, reveals the romantic and archaizing ideas that underscored his perception of this rural culture as frozen in an allegedly simpler, premodern era. It is through this practice of fusing imaginatively the realms of the human and the botanical in an antimodernist vision (typical of modernist primitivism) that we can best discern his approach to the Breton landscape.4Two essential sources on “modernist primitivism” are Priyanka Basu, “Primitivism,” in The Routledge Encyclopedia of Modernism (Oxfordshire: Taylor and Francis, 2016), https://doi.org/10.4324/9781135000356-REM1108-1; and Frances S. Connelly, The Sleep of Reason: Primitivism in Modern European Art and Aesthetics, 1725–1907 (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1995).

In 1889, Gauguin returned to Brittany from Paris and moved to the seaside town of Le Pouldu, where he took up residence at an inn run by Marie Henry.5Gloria Groom, ed., Gauguin: Artist as Alchemist, exh. cat. (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2017), 15. Gauguin lived there with fellow artist Meyer Isaac de Haan (Dutch, 1852–95) and painted in the area from October 2, 1889, until early February 1890.6Richard Brettell, “The Willow Tree” (catalogue entry), in Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum, 2007), 119. He designed works to enhance an overall decorative scheme in the inn’s dining room and further pondered the powers of form and color in order to construct harmonious compositions that would engage the viewer as much through formal means as through their ostensible subject.

The vertical orientation of the picture allows Gauguin to incorporate a legible receding landscape into his decorative scheme, glimpsed through the intertwined and soaring branches of the willows. Some of the branches are wiry and thin, reaching toward the sky. Some convey the more bulbous and idiosyncratic form of gnarled “air roots,” a distinctive feature of the willow. One tall branch at the far right, piercing the horizon line, demands to be read as an independent form, more like the head of a bass or a cello than a tree. The detail may, in fact, reference Gauguin’s abiding belief in the power of music, which he had come to appreciate as a high form of pure, non-mimetic expression.8The literature on French Symbolism and music is vast. One excellent starting place is Peter Palmer, “Lost Paradises: Music and the Aesthetics of Symbolism,” Musical Times 148, no. 1899 (Summer 2007): 37–50. Indeed, in this moment, Gauguin was developing his larger identification with the Paris-based Symbolist movement, cultivating a capacity to suggest broader and (ideally) universally accessible meanings in his art that transcend empirical form and the imitation of nature.9On Gauguin and Symbolism, one of many useful studies is Henry Dorra, The Symbolism of Paul Gauguin: Erotica, Exotica and the Great Dilemmas of Humanity (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007).

This complex scene is inhabited, but the figures, quasi-hidden in plain sight in the foreground, are subordinate to the explosion of vegetal form and color. The four figures, clothed simply, appear as stock characters compared to the complexity and variety of the landscape they inhabit. At lower right stand two Breton women, identifiable by their regional headdresses and sabots (wooden shoes). Their heads bent over sloped shoulders, they are isolated from the men and, by contrast, they appear less active. One, on the left, holds a wisp of a willow branch, perhaps intended to be used for weaving baskets. Their primary role in the scene, however, is not as laborers, and certainly not as specific individuals, but rather as prominent signposts—by virtue of their costume—for the specific region depicted in the scene. They locate us geographically, just as the blue strip of sea in the opposite corner, at the upper left horizon, speaks to the probable setting of the coastal town Le Pouldu. The landscape in between these two rather standard corner motifs (the rural women, a staple of Salon painting of the time,10Breton women were common in French academic painting, from the work of Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796–1875) in the 1830s to the popular academic images shown in the Salon by (for example) Jules Breton (1827–1906) and Léon-Augustin Lhermitte (1844–1925) in the 1880s. and the sea on the horizon) unfolds unpredictably with intense variety and visual interest.

In the middle foreground, one of the men leans over the ground, perhaps to move a stone. We see no face beneath the round hat, and his two hands fuse as one—all choices that make his cohesive rounded shape harmonize well with nearby forms of trunks and foliage. It is the blue of his farmer’s jacket that first distinguishes him as human, not vegetal. And, most hidden of all, at far left is a dark-clad figure whose form recedes as the salmon-hued foliage he works on first pops to our attention. Unlike the women in the scene, the men reach, stretch, and pull, engaged in labor. They are inhabitants and laborers, but the promise of their own stories and dramas is thin compared to the lure of nature here, in its cacophonous hues and interlocking forms that continually invite our eye and our attention.

Between the laborer on the left and the salmon-hued road is an ambiguous tall gray form, firmly planted in the ground. It probably depicts a stone menhir, a carved ceremonial stone from the Bronze age that is particularly common, even today, in northwestern France and in Britain. This form conjures the Celtic culture of spirits that some in this era still believed to inhabit this landscape. Although much larger menhirs populate the landscape of Brittany, this relatively small one stands like a corporeal or specter-like presence, closely aligned to human scale. In its unarticulated and suggestive form, its presence may signal Gauguin’s efforts to associate this rural population with an abstract sense of mysterious spirituality. We are reminded here of his essentializing perception of a “great rustic and superstitious simplicity” that he proudly discerned in his own representations of Breton peasants.11Dario Gamboni, Paul Gauguin: The Mysterious Centre of Thought, trans. Chris Miller (London: Reaktion Books, 2015), 92–95. Other examples of his construction of a specifically Breton spirituality appear in his well-known images from these years that derived from the ubiquitous Catholic practices and material culture of the area: Vision after the Sermon (1888; National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh) and The Yellow Christ (1889; Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo), another autumnal scene, in this case inspired by late medieval Breton crosses.

Fig. 3. Paul Gauguin, Landscape in Brittany, 1889, oil on canvas, 36 1/2 x 28 3/4 in. (92 x 73 cm), National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design, Oslo, NG.M.01006

Fig. 3. Paul Gauguin, Landscape in Brittany, 1889, oil on canvas, 36 1/2 x 28 3/4 in. (92 x 73 cm), National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design, Oslo, NG.M.01006

Fig. 4. Paul Sérusier, The Seaweed Gatherer, 1889, oil on canvas, 18 1/8 x 21 11/16 in. (46 x 55 cm), Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, Collection Josefowitz, 1998.181.

Fig. 4. Paul Sérusier, The Seaweed Gatherer, 1889, oil on canvas, 18 1/8 x 21 11/16 in. (46 x 55 cm), Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, Collection Josefowitz, 1998.181.

It is above all the force and the ambiguity of nature, in all its variety and unpredictability, that engaged Gauguin’s imagination in this painting. This work may render a specific landscape scene near Le Pouldu in Brittany, but the resulting image foregrounds experimentation, variety, unpredictability, the intense sensations of the visual world, and the constantly shifting capacities of the imagination. Certain geographic referents to Brittany are clear and specific: sabots, willow trees, perhaps a stone menhir. But this picture is at once a constructed recollection of that provincial world (“wild and primitive,” in Gauguin’s terms) and a celebration of the powers of creative sight and the imagination of the artist himself, who prefers to dream before nature rather than to copy what lies before him.14Gauguin wrote to Schuffenecker on August 14, 1888: “Some advice: do not paint too much after nature. Art is an abstraction; derive this abstraction from nature while dreaming before it, and think more of the creation which will result than of nature” (Un conseil, ne copiez pas trop d’après nature. L’art est une abstraction: tirez-la de la nature en rêvant devant et pensez plus à la création qu’au résultat). In In Victor Merlhès, Correspondance de Paul Gauguin: Documents, Témoignages (Paris: Foundation Singer-Polignac, 1984), 172, letter 159. It is no surprise that this painting was produced just over a year before G.-Albert Aurier (1865–92) publicly celebrated Gauguin as the consummate Symbolist artist.15See G.-Albert Aurier, “Le Symbolisme en peinture: Paul Gauguin,” Mercure de France 2, no. 15 (March 1891): 155–56.

Notes

-

A classic reference on this mythology as it informs Gauguin’s practice is Griselda Pollock and Fred Orton, “Les Donées Bretonnantes/La Prairie de la Répresentation,” Art History 3, no. 3 (September 1980): 314–44.

-

“Je me laisse vivre dans la muette contemplation de la nature, tout entier à mon art.” Gauguin to Emile Schuffenecker (1851–1934), Pont-Aven, late February 1888, translated and quoted in Belinda Thomson, ed., Gauguin by Himself (London: Time Warner Books, 2004), 62.

-

“J’aime la Bretagne, j’y trouve le sauvage, le primitif. Quand mes sabots résonnent sur ce sol de granit, j’entends le ton sourd, mat et puissant que je cherche en peinture.” Gauguin to Schuffenecker, late February 1988, translated and quoted in Thomson, Gauguin by Himself, 62.

-

Two essential sources on “modernist primitivism” are Priyanka Basu, “Primitivism,” in The Routledge Encyclopedia of Modernism (Oxfordshire: Taylor and Francis, 2016), https://doi.org/10.4324/9781135000356-REM1108-1; and Frances S. Connelly, The Sleep of Reason: Primitivism in Modern European Art and Aesthetics, 1725–1907 (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1995).

-

Gloria Groom, ed., Gauguin: Artist as Alchemist, exh. cat. (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2017), 15.

-

Richard Brettell, “The Willow Tree” (catalogue entry), in Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum, 2007), 119.

-

See for example, André Derain (1880–1954), Hyde Park, ca. 1906, oil on canvas, 26 x 39 in. (66 x 99 cm), Musée d’Art Moderne, Troyes, France, MNPL56.

-

The literature on French Symbolism and music is vast. One excellent starting place is Peter Palmer, “Lost Paradises: Music and the Aesthetics of Symbolism,” Musical Times 148, no. 1899 (Summer 2007): 37–50.

-

On Gauguin and Symbolism, one of many useful studies is Henry Dorra, The Symbolism of Paul Gauguin: Erotica, Exotica and the Great Dilemmas of Humanity (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007).

-

Breton women were common in French academic painting, from the work of Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796–1875) in the 1830s to the popular academic images shown in the Salon by (for example) Jules Breton (1827–1906) and Léon-Augustin Lhermitte (1844–1925) in the 1880s.

-

Dario Gamboni, Paul Gauguin: The Mysterious Centre of Thought, trans. Chris Miller (London: Reaktion Books, 2015), 92–95.

-

Bretell, “The Willow Tree,” 116.

-

The authenticity of this watercolor, accepted by the late Richard Brettell and by the present author, has been questioned in the past. See “In Brittany (En Bretagne),” website of The Whitworth, University of Manchester, accessed March 29, 2022, http://gallerysearch.ds.man.ac.uk/Detail/3701, esp. “Collection Exhibitions: Fakes and Mistakes: Object Label: D.1926.20.”

-

Gauguin wrote to Schuffenecker on August 14, 1888: “Some advice: do not paint too much after nature. Art is an abstraction; derive this abstraction from nature while dreaming before it, and think more of the creation which will result than of nature” (Un conseil, ne copiez pas trop d’après nature. L’art est une abstraction: tirez-la de la nature en rêvant devant et pensez plus à la création qu’au résultat). In Victor Merlhès, Correspondance de Paul Gauguin: Documents, Témoignages (Paris: Foundation Singer-Polignac, 1984), 172, letter 159.

-

See G.-Albert Aurier, “Le Symbolisme en peinture: Paul Gauguin,” Mercure de France 2, no. 15 (March 1891): 155–56.

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Mary Schafer, “Paul Gauguin, Autumn in Brittany (The Willow Tree), 1889,” technical entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.714.2088.

MLA:

Schafer, Mary. “Paul Gauguin, Autumn in Brittany (The Willow Tree), 1889,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.714.2088.

Autumn in Brittany (The Willow Tree) was executed on a medium-weight, plain-weaveplain weave: A basic textile weave in which one weft thread alternates over and under the warp threads. Often this structure consists of one thread in each direction, but threads can be doubled (basket weave) or tripled to create more complex plain weave. Plain weave is sometimes called tabby weave. canvas that is close in size to a no. 30 figure standard-format supportstandard-format supports: Commercially prepared supports available through art suppliers, which gained popularity in the nineteenth century during the industrialization of art materials. Available in three formats figure (portrait), paysage (landscape), and marine (marine), these were numbered 1 through 120 to indicate their size. For each numbered size, marine and paysage had two options available: a larger format (haute) and smaller (basse) format.,1David Bomford, Jo Kirby, John Leighton, and Ashok Roy, Art in the Making: Impressionism (London: Yale University Press, 1991), 45. although no supplier stampcanvas stamp: An ink stamp, often present on the reverse of the canvas, signifying the company that sold or prepared the canvas. As these companies sometimes performed framing and restorations, these stamps could also reflect these services. See also supplier mark. is evident on the reverse of the unlinedlining: A procedure used to reinforce a weakened canvas that involves adhering a second fabric support using adhesive, most often a glue-paste mixture, wax, or synthetic adhesive. canvas. Gauguin appears to have primed the canvas himself, as the thin white groundground layer: An opaque preparatory layer applied to the support, either commercially or by the artist, to prevent absorption of the paint into the canvas or panel. See also priming layer. does not continue to the tacking marginstacking margins: The outer edges of canvas that wrap around and are attached to the stretcher or strainer with tacks or staples. See also tacking edge..2A selvedge is present on the top and bottom tacking margins, and cusping corresponds to the former tack locations, which were placed approximately six to eight centimeters apart. By 1887, Gauguin was preparing his own canvases with some regularity, preferring to paint upon an absorbent, glue-chalk ground.3Carol Christensen, “The Painting Materials and Techniques of Paul Gauguin,” Studies in the History of Art 41 (1993): 71–73.

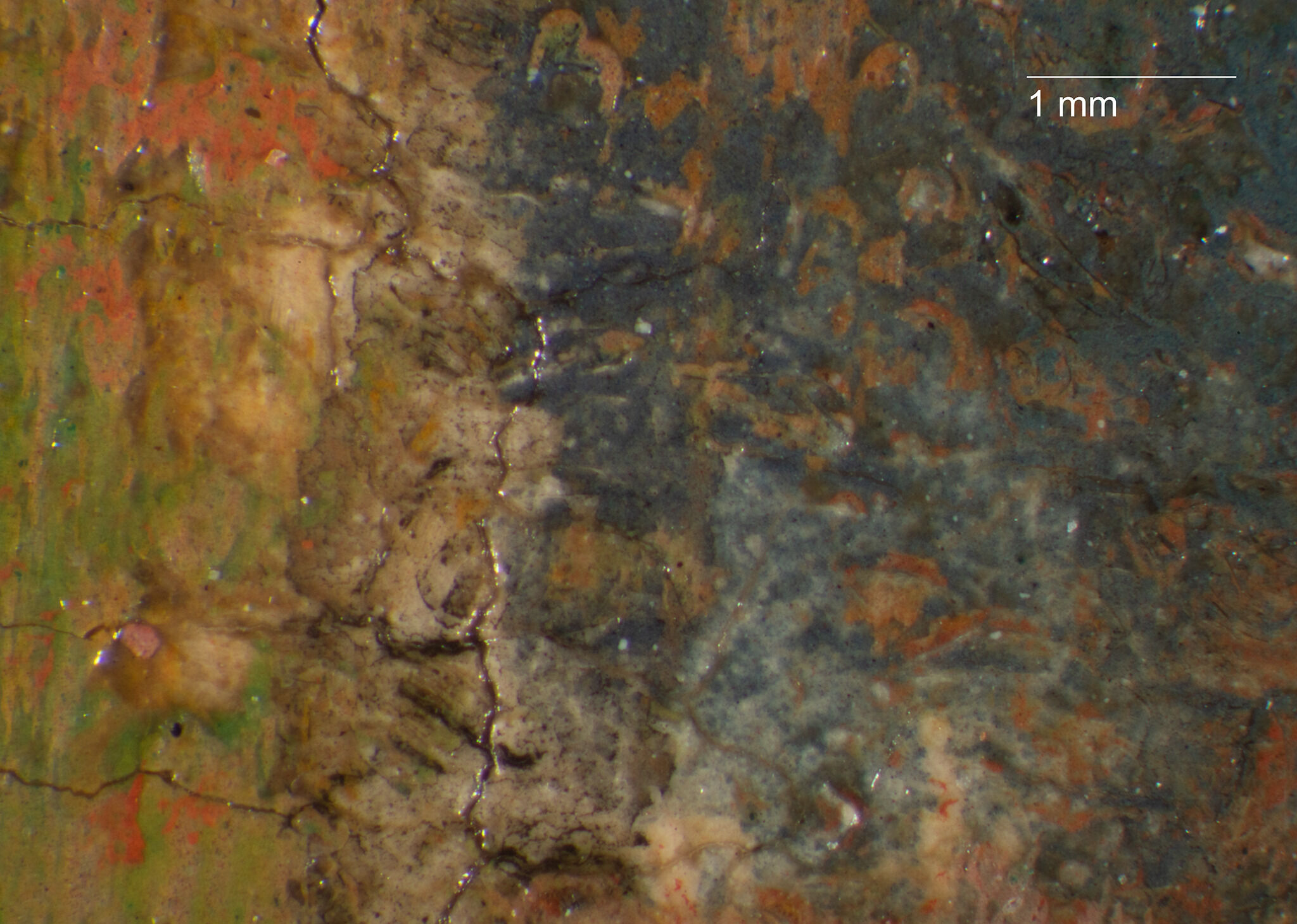

Fig. 6. Photomicrograph of several opaque black lines that correspond to the painted sketch, located at the base of the left figure’s foot, Autumn in Brittany (The Willow Tree) (1889)

Fig. 6. Photomicrograph of several opaque black lines that correspond to the painted sketch, located at the base of the left figure’s foot, Autumn in Brittany (The Willow Tree) (1889)

Fig. 7. Photomicrograph of a dilute black stroke associated with the painted sketch, located at the edge of the central figure’s proper right hand, Autumn in Brittany (The Willow Tree) (1889)

Fig. 7. Photomicrograph of a dilute black stroke associated with the painted sketch, located at the edge of the central figure’s proper right hand, Autumn in Brittany (The Willow Tree) (1889)

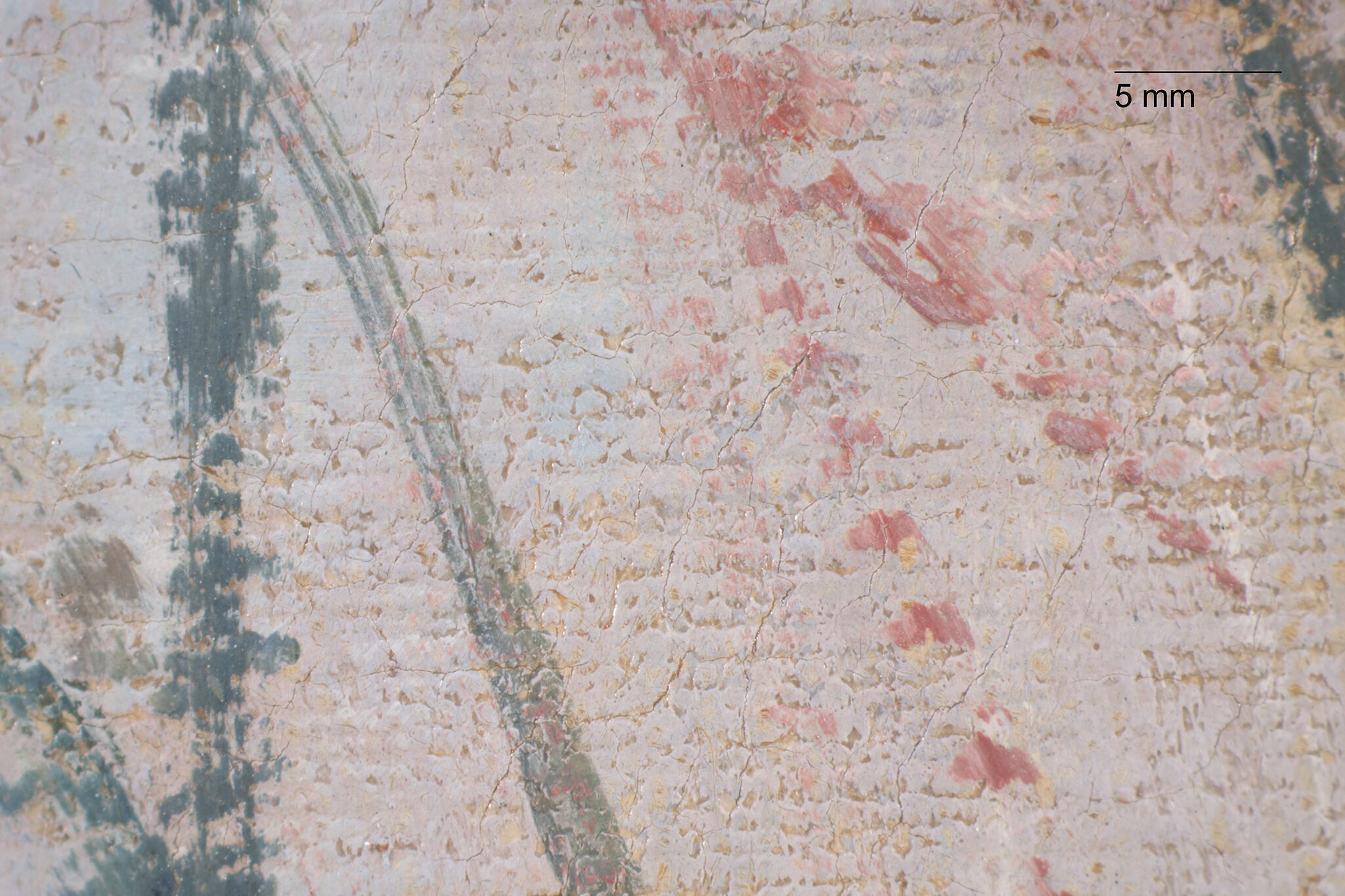

Gauguin blocked in the design with thin layers of color, many of which remain visible at the edge of forms and between subsequent paint strokes.5A similar construction is evident beneath the paint layers of Faaturuma (Melancholic) (1891) and Landscape in Le Pouldu (1894). See the technical entries by Mary Schafer for “Paul Gauguin, Faaturuma (Melancholic), 1891,” and “Paul Gauguin, Landscape in Le Pouldu, 1894,” in this catalogue, https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.716.2088 and https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.718.2088. In select passages, the bright color of this preliminary layer is subdued by later additions of paint, an aspect of the artist’s technique that has been documented on other works from this period.6See H. Travers Newton, “Observations on Gauguin’s Painting Techniques and Materials,” in A Closer Look: Technical and Art-Historical Studies on Works by Van Gogh and Gauguin, ed. Cornelia Peres, Michael Hoyle, and Louis van Tilborgh (Zwolle: Waanders, 1991), 108–09. For instance, a vivid red lies beneath the muted gray-purple strokes of the foliage on the upper right edge (Fig. 8), and the bright teal washwash: An application of thin paint that has been diluted with solvent. of the central bushes was toned down by overlying strokes of dark green (Fig. 9).

Fig. 8. Photomicrograph of Autumn in Brittany (The Willow Tree) (1889), revealing a bright red layer beneath the gray-purple paint of the upper-right foliage

Fig. 8. Photomicrograph of Autumn in Brittany (The Willow Tree) (1889), revealing a bright red layer beneath the gray-purple paint of the upper-right foliage

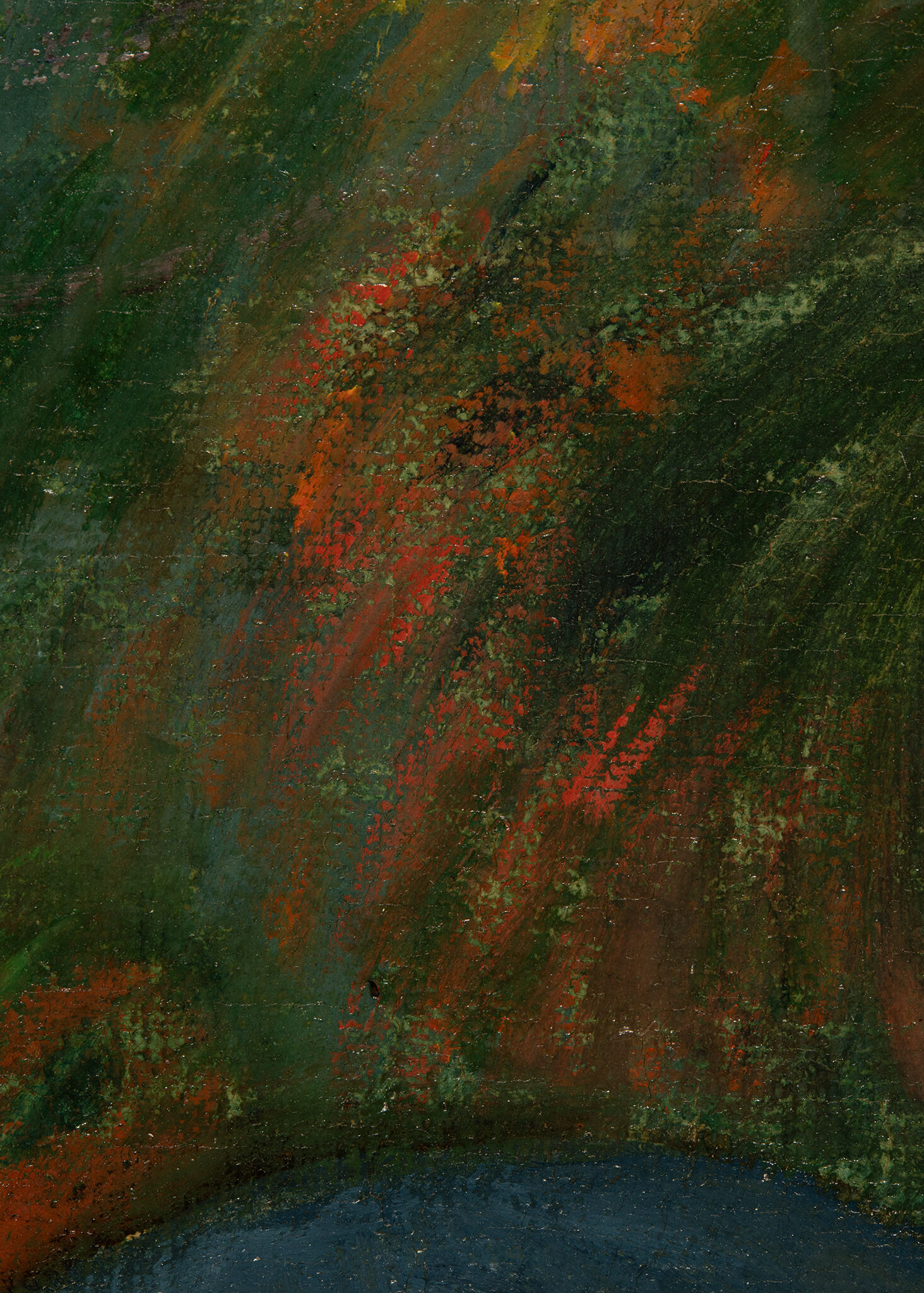

Fig. 9. Detail of Autumn in Brittany (The Willow Tree) (1889), revealing a teal-colored wash beneath the central bushes

Fig. 9. Detail of Autumn in Brittany (The Willow Tree) (1889), revealing a teal-colored wash beneath the central bushes

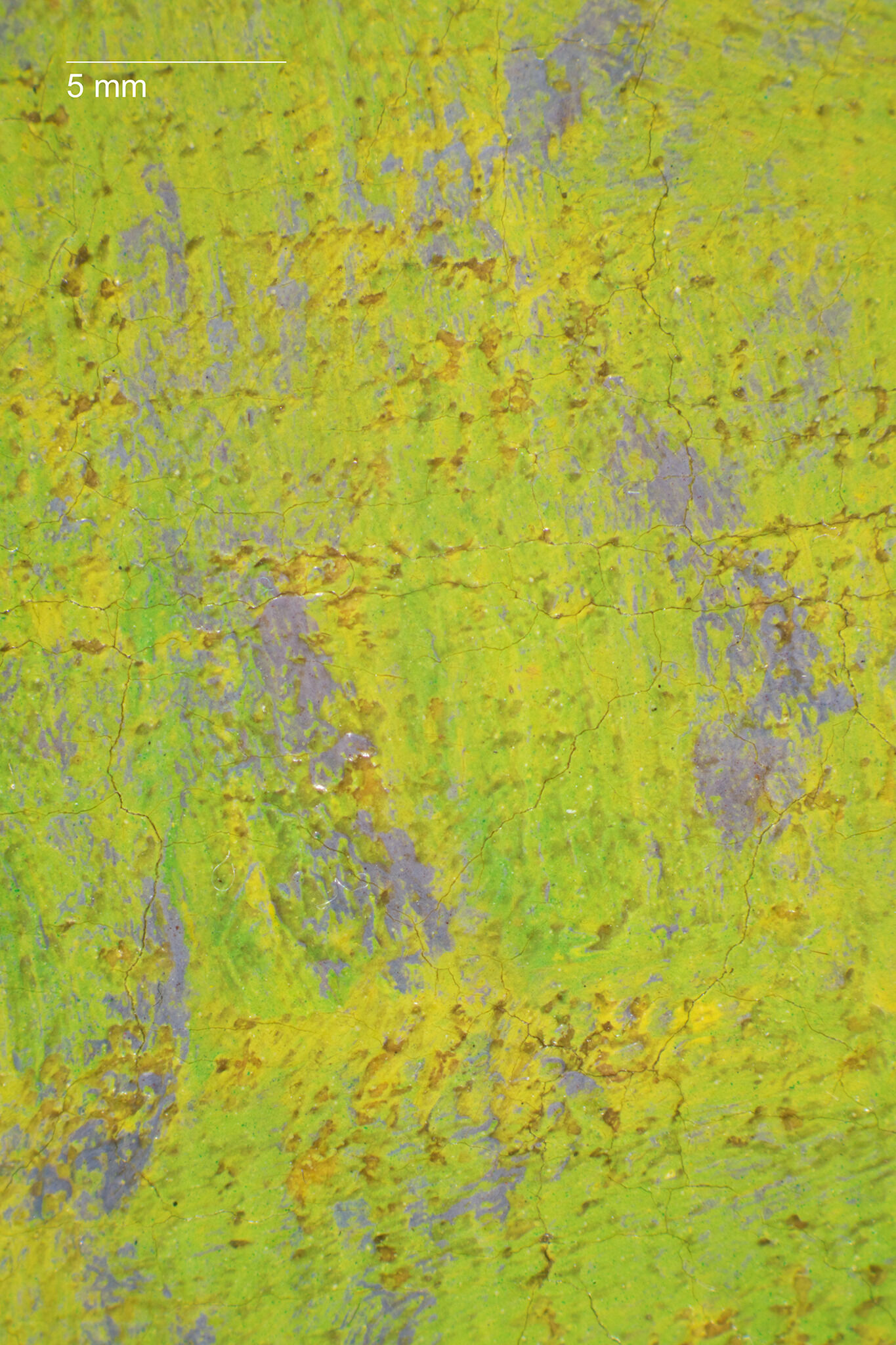

Gauguin made use of complementary color contrasts throughout Autumn in Brittany (The Willow Tree), and, in doing so, heightened the vibrancy of the individual colors. Examples of these color juxtapositions include the bright red paint strokes that accent the dark green, central bushes and the dashes of purple scattered across the bright yellow-green field (Figs. 9, 11). In the foreground, groupings of vertical paint strokes consist of bright, complementary colors—red-orange placed alongside various shades of green—as well as mixtures of these colors (i.e. broken tones) that formed muted tones that range from pink-brown to orange-green (Fig. 12). Collectively, Gauguin’s brushwork and color choices produce a vibrating, striped effect that enlivens the foreground.

Fig. 11. Photomicrograph of Autumn in Brittany (The Willow Tree) (1889), showing the purple dashes of paint applied on top of the bright yellow-green field

Fig. 11. Photomicrograph of Autumn in Brittany (The Willow Tree) (1889), showing the purple dashes of paint applied on top of the bright yellow-green field

Fig. 12. Detail of the foreground of Autumn in Brittany (The Willow Tree), comprised of vertical paint strokes of red-orange and green as well as varying mixtures of these two complementary colors

Fig. 12. Detail of the foreground of Autumn in Brittany (The Willow Tree), comprised of vertical paint strokes of red-orange and green as well as varying mixtures of these two complementary colors

Fig. 13. Detail of an overpainted tree branch, Autumn in Brittany (The Willow Tree) (1889)

Fig. 13. Detail of an overpainted tree branch, Autumn in Brittany (The Willow Tree) (1889)

Fig. 14. Photomicrograph of the date, lower right corner of Autumn in Brittany (The Willow Tree) (1889). Black lines mark the outer edges of lavender and blue-gray paint associated with the final digit.

Fig. 14. Photomicrograph of the date, lower right corner of Autumn in Brittany (The Willow Tree) (1889). Black lines mark the outer edges of lavender and blue-gray paint associated with the final digit.

Fig. 15. UV-induced visible fluorescence detail photograph of the signature, Autumn in Brittany (The Willow Tree) (1889)

Fig. 15. UV-induced visible fluorescence detail photograph of the signature, Autumn in Brittany (The Willow Tree) (1889)

Fig. 16. UV-induced visible fluorescence photograph of Autumn in Brittany (The Willow Tree) (1889). Photo courtesy of Diana M. Jaskierny.

Fig. 16. UV-induced visible fluorescence photograph of Autumn in Brittany (The Willow Tree) (1889). Photo courtesy of Diana M. Jaskierny.

Notes

-

David Bomford, Jo Kirby, John Leighton, and Ashok Roy, Art in the Making: Impressionism (London: Yale University Press, 1991), 45.

-

A selvedgeselvedge: The original woven edge of fabric formed by the weft threads looping over the warp during the loom weaving process. The selvedge runs the length of the fabric bolt, parallel to the warp threads, and forms a finished edge. is present on the top and bottom tacking margins, and cuspingcusping: A scalloped pattern along the canvas edges that relates to how the canvas was stretched. Primary cusping reveals where tacks secured the canvas to the support while the ground layer was applied. Secondary cusping can form when a pre-primed canvas is re-stretched by the artist prior to painting. corresponds to the former tack locations, which were placed approximately six to eight centimeters apart.

-

Carol Christensen, “The Painting Materials and Techniques of Paul Gauguin,” Studies in the History of Art 41 (1993): 71–73.

-

Although Gauguin occasionally used reference lines to transfer drawn imagery onto the primed canvas, he does not appear to have used this particular method for the Nelson-Atkins painting. For a description of the artist’s various transfer techniques, see Morgan Wylder, “Re-examination and Contextualization of Paintings by Paul Gauguin in the Courtauld Gallery” (Third Year Project, The Courtauld Institute of Art, 2015), 11–12, 29, Fig. I.13.

-

A similar construction is evident beneath the paint layers of Faaturuma (Melancholic) (1891) and Landscape in Le Pouldu (1894). See the technical entries by Mary Schafer for “Paul Gauguin, Faaturuma (Melancholic), 1891" and “Paul Gauguin, Landscape in Le Pouldu, 1894” in this catalogue, https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.716.2088 and https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.718.2088.

-

See H. Travers Newton, “Observations on Gauguin’s Painting Techniques and Materials,” in A Closer Look: Technical and Art-Historical Studies on Works by Van Gogh and Gauguin, ed. Cornelia Peres, Michael Hoyle, and Louis van Tilborgh (Zwolle: Waanders, 1991), 108–09.

-

Richard Brettell, “The Willow Tree” (catalogue entry), in Richard R. Brettell

and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection (Kansas City: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 119. “Oddly, the signature and date in the lower right, painted in a pale warm gray shot with pink and blue, are abraded and hence almost invisible, which, for Gauguin, who made the act of signing almost a fetish in the late 1880s, is highly unusual.” With the aid of a stereomicroscope, it is possible to confirm that the final stroke of the “9” is dryly applied, skipping across the upper points of the canvas weave, rather than abraded. -

Helmut Schweppe and John Winter, “Madder and Alizarin,” in Artists’ Pigments: A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics, ed. Elisabeth West FitzHugh (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), 3:124.

-

Color shifts associated with red lake have been identified on other works by the artist. Technical study of Among the Lilacs (1889; private collection), painted by Gauguin in the same year as Autumn in Brittany, verified that a fugitive red lake had caused the foreground colors to shift from pink and violet to white, gray, and blue. See Paolo Cadorin, “Colour Fading in Van Gogh and Gauguin,” in A Closer Look: Technical and Art-Historical Studies on Works by Van Gogh and Gauguin, 16, figs. III, IV, IX, X. The background of Portrait of Vaïte (Jeanne) Goupil (1896; Ordrupgaard Collection, Copenhagen) has faded, and a more intense pink color is visible at the outer edge of the painting, where the frame protected the paint from light exposure. See Christensen, “The Paintings Materials and Technique of Paul Gauguin,” 83–86. A salmon-pink UV-induced fluorescence is evident on the upper left path of Arlésiennes (Mistral) (1888; Art Institute of Chicago), and analysis has confirmed the presence of a now-faded red lake that originally depicted a path with a stronger, deep pink color. Kristin Hoermann Lister, “Gauguin, Cat. 10, Arlésiennes (1934.391): Technical Study,” in Gauguin Paintings, Sculpture, and Graphic Works at the Art Institute of Chicago, ed. Gloria Groom and Genevieve Westerby (Art Institute of Chicago, 2016), para 82–83.

-

Christensen, “The Painting Materials and Technique of Paul Gauguin,” 81–82.

-

“Because of his efforts to create a matte paint surface (draining his oil paints, painting on an absorbent ground, and washing his painting to degrease them), Gauguin was adamant that his paintings not be varnished with the glossy natural resin varnishes common during his time. He occasionally recommended that his paintings be protected with a piece of glass when framed, but more often he made reference to using wax as a protective surface coating.” See Christensen, “The Painting Materials and Technique of Paul Gauguin,” 92.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Paul Gauguin, Autumn in Brittany (The Willow Tree), 1889,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.714.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Paul Gauguin, Autumn in Brittany (The Willow Tree), 1889,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.714.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Paul Gauguin, Autumn in Brittany (The Willow Tree), 1889,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.714.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Paul Gauguin, Autumn in Brittany (The Willow Tree), 1889,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.714.4033.

Deposited by the artist with Claude-Émile Schuffenecker (1851–1934), Paris, probably by December 1890–93 [1];

Purchased from the artist, through Schuffenecker, by George-Daniel de Monfreid (1856–1929), Paris, by August 3, 1893 [2];

Purchased from de Monfreid by Ernest Cros (1857–1946), Paris, 1893–no later than 1938;

To his daughter Dr. Lucile-Marie-Jeanne Ménard (née Cros, 1888–1951), Paris, by 1938–51 [3];

By descent to her niece, Colette-Marie-Christine Andrieu (née May, 1912–2016), Paris, 1951–December 1981 [4];

Purchased from Andrieu by the Galerie Robert Schmit, Paris, December 1981 [5];

Purchased from Galerie Robert Schmit by Alex Reid and Lefèvre Ltd., London, by June 16, 1983–84 [6];

Purchased from Alex Reid and Lefèvre Ltd., through Susan L. Brody Associates, New York, by Marion (née Helzberg, 1931–2013) and Henry (1922–2019) Bloch, Shawnee Mission, KS, June 12, 1984–June 15, 2015;

Their gift to The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 2015.

Notes

[1] Gauguin stayed with Schuffenecker in Paris from December 1890 until he left for Tahiti in April 1891. Jean de Rotonchamp describes Gauguin’s latest paintings stacked up in Schuffenecker’s home “turned to face the wall, sitting directly on the floor” as of December 1890. It is probable that this 1889 picture was amongst those that Gauguin stored in Schuffenecker’s home. Jean de Rotonchamp, Paul Gauguin, 1848–1903 (Paris: Éditions G. Crès et Cie, 1925), 77. A letter from George-Daniel de Monfreid to Ernest Cros, ca. 1893, collection of Daniel Andrieu (copy in NAMA curatorial files), states that Cros saw the painting at the home of Émile Schuffenecker in 1892.

[2] Because de Monfreid was born in New York, he wanted his first name to be spelled the American way without the “S”: “George.” See also letter from George-Daniel de Monfreid to Ernest Cros, ca. 1893, NAMA curatorial files. This letter specifies that de Monfreid purchased the work from Gauguin sometime before Gauguin returned to Paris from his first trip to Tahiti in August 1893.

[3] Raymond Cogniat lists Ménard as the owner of the painting for the first time in 1938. See Raymond Cogniat, Gauguin (Paris: Éditions Braun et Cie, 1938), unpaginated. Ménard had no children and left her Gauguin to her niece, Colette-Marie-Christine Andrieu. See email from Daniel Andrieu, son of Colette Andrieu, to Glynnis Napier Stevenson, NAMA, January 4, 2019, NAMA curatorial files.

[4] See email from Daniel Andrieu, son of Colette Andrieu, to Glynnis Stevenson, NAMA, January 4, 2019, NAMA curatorial files.

[5] See email from Manuel Schmit, Galerie Schmit, Paris, to Brigid Boyle, NAMA, May 4, 2015, NAMA curatorial files.

[6] See email from Alex Corcoran, Lefevre Fine Art, to MacKenzie Mallon, NAMA, March 18, 2019. The painting was featured in a Lefèvre exhibition in the summer of 1983. See Important XIX and XX Century Works of Art, Lefèvre Gallery, London, June 16–July 22, 1983, no. 6, as Le Saule.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Paul Gauguin, Autumn in Brittany (The Willow Tree), 1889,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.714.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Paul Gauguin, Autumn in Brittany (The Willow Tree), 1889,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.714.4033.

Paul Gauguin, The Willows, 1889, oil on canvas, 36 1/4 x 29 5/16 in. (92.0 x 74.5 cm), Nasjonalgalleriet, Oslo.

Paul Gauguin, Study of Willow Heads, 1890, gouache on grayish brown cardboard, 15 1/4 x 11 3/4 in. (38.8 x 29.8 cm), private collection.

Paul Gauguin, Two Breton Women, 1894, watercolor monotype, 9 13/16 x 8 1/4 in. (25.0 x 21.0 cm), location unknown, illustrated in Richard S. Field, Paul Gauguin: Monotypes, exh. cat. (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1973), 69.

Preparatory Works

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Paul Gauguin, Autumn in Brittany (The Willow Tree), 1889,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.714.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Paul Gauguin, Autumn in Brittany (The Willow Tree), 1889,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.714.4033.

Paul Gauguin, Late Winter, Pont-Aven, Breton and Calf, 1888, oil on canvas, 35 3/5 x 27 9/10 in. (90.5 x 71 cm), Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen.

Paul Gauguin, Little Breton Boy Adjusting His Clog, ca. 1888, charcoal enhanced with dry pastel on blue-gray laid paper, sheet: 12 5/8 x 18 3/4 in. (32 x 47.6 cm), Musée de Quai Branly, Paris.

Paul Gauguin, Childhood of Brittany, 1889, pastel and watercolor on paper, 10 1/16 x 14 3/4 in. (25.5 x 37.5 cm), Fukushima Prefectural Museum of Art, Aizuwakamatsu, Japan.

Paul Gauguin, In Brittany, 1889, watercolor, 14 15/16 x 10 5/8 in. (37.9 x 27 cm), The Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester.

Copies

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Paul Gauguin, Autumn in Brittany (The Willow Tree), 1889,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.714.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Paul Gauguin, Autumn in Brittany (The Willow Tree), 1889,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.714.4033.

George-Daniel de Monfreid (1856–1929), after Paul Gauguin, Two Breton Women, ca. 1893, oil on cardboard, 13 19/50 x 10 7/20 in. (34 x 26.3 cm), collection of Daniel Andrieu.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Paul Gauguin, Autumn in Brittany (The Willow Tree), 1889,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.714.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Paul Gauguin, Autumn in Brittany (The Willow Tree), 1889,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.714.4033.

Salon d’Automne: 4me exposition; Œuvres de Gauguin, Grand Palais, Paris, October 6–November 15, 1906, no. 215, as L’Automne en Bretagne.

Exposition Rétrospective: Hommage au génial Artiste Franco-Péruvien Gauguin, Association Paris-Amérique Latine, Paris, opened December 17, 1926, no. 7, as Paysage de Bretagne.

Possibly La Vie Ardente de Gauguin, Gazette des Beaux-Arts, Paris, November 1936, no. 77, as Paysage de Bretagne.

Gauguin: Exposition du centenaire, Musée de l’Orangerie des Tuileries, Paris, July 1949, no. 17, as Paysage de Bretagne: le Saule.

Chefs-d’œuvre des collections françaises, Musée Jacquemart-André, Paris, July–September 1961, no. 79.

Important XIX and XX Century Works of Art, Lefèvre Gallery, London, June 16–July 22, 1983, no. 6, as Le Saule.

Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, June 9–September 9, 2007, no. 22, as The Willow Tree (Le saule).

References

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Paul Gauguin, Autumn in Brittany (The Willow Tree), 1889,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.714.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Paul Gauguin, Autumn in Brittany (The Willow Tree), 1889,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.714.4033.

Catalogue des Ouvrages de Peinture, Sculpture, Dessin, Gravure, Architecture et Art Décoratif, exh. cat. (Paris: Compagnie Française des Papiers-Monnaie, 1906), 201, as L’Automne en Bretagne.

Robert Rey, Masters of Modern Art: Gauguin, trans. F[rédéric] C[esar] de Sumichrast (London: Bodley Head, [1924]), 5, (repro.), as The Willow, Le Saule, Die Weide, Il salice, and El sauce.

Exposition Rétrospective: Hommage au génial Artiste Franco-Péruvien Gauguin, exh. cat. (Paris: Association Paris-Amérique Latine, 1926), 18, as Paysage de Bretagne.

F[elipe] Cossío del Pomar, Arte y Vida de Pablo Gauguin (Escuela Sintetista) (Paris: Léon Sánchez Cuesta, 1930), 119, 364, (repro.), as Paisaje bretón.

Possibly Raymond Cogniat, La Vie Ardente de Paul Gauguin, exh. cat. (Paris: Gazette des Beaux-Arts, [1936]), 61, as Paysage de Bretagne.

Raymond Cogniat, Gauguin (Paris: Éditions Braun et Cie, 1938), (repro.), as Le saule. Bretagne.

R[eginald] H[oward] Wilenski, Modern French Painters (New York: Reynal and Hitchcock, [1940]), 351, as Le saule: Paysage de Bretagne.

Maurice Malingue, Gauguin (Monaco: Documents d’art, 1943), 72, 154, (repro.), as Le Saule, Paysage Breton.

Anne-Marie Berryer, “À Propos d’un Vase de Chaplet Décoré par Gauguin,” Bulletin des Musées Royaux d’Art et d’Histoire 16, nos. 1–2 (January–April 1944): 19, 21, (repro.), as Le Saule.

Hans Graber, Paul Gauguin: Nach Eigenen und Fremden Zeugnissen, 2nd ed. (Basel: Benno Schwabe, 1946), 509, (repro.), as Bretagnelandschaft.

Raymond Cogniat, Gauguin (Paris: Éditions Pierre Tisné, 1947), 50, (repro.), as The Willow-Tree.

René-Jean, Gauguin (Paris: Éditions Braun et Cie, 1948), unpaginated, (repro.), as Paysage de Bretagne. Le Saule.

Maurice Malingue, Gauguin: Le Peintre et Son Œuvre (Paris: Presses de la Cité, 1948), 138, (repro.), as Le Saule.

Jean Leymarie, Gauguin: Exposition du Centenaire, exh. cat. ([Paris]: Éditions des musées nationaux, 1949), 29–30, as Paysage de Bretagne: Le Saule.

John Rewald, Gauguin (New York: Hyperion Press, 1949), 88, 166, (repro.), as The Willow: Landscape in Brittany.

Lee Van Dovski [Herbert Lewandowski], Paul Gauguin, oder die Flucht vor der Zivilisation (Olten, Switzerland: Delphi Verlag, 1950), 345, as Le saule.

Gilberte Martin-Méry, Gauguin et le Groupe de Pont-Aven, exh. cat. (Paris: Éditions des musées nationaux, 1950), 16, as Le Saule.

Raymond Cogniat, Paul Gauguin, 1848–1903 (Paris: Éditions Braun et Cie, 1953), unpaginated, (repro.), as Le Saule. Bretagne.

Richard S. Field, Paul Gauguin: The Paintings of the First Voyage to Tahiti (1963; repr., New York: Garland, 1977), 28, 37, 235n23, as Le Saule.

Georges Wildenstein, Gauguin, vol. 1, Catalogue (Paris: Beaux-Arts, 1964), no. 347, pp. 96, 132–33, 281, (repro.), as Le Saule.

Merete Bodelsen, “The Literature of Art: The Wildenstein-Cogniat Gauguin Catalogue,” Burlington Magazine 108, no. 754 (January 1966): 36.

G[abriele] M[andel] Sugana, L’opera completa di Gauguin (Milan: Rizzoli, 1972), no. 166, pp. 96–97, 119, (repro.), as Il Salice.

Lee van Dowski [Herbert Lewandowski], Die Wahrheit über Gauguin: Mit vielen, zum Teil farbigen Abbildungen und einem “Katalog der Gemälde” (Darmstadt, Germany: Josef Gotthard Bläschke Verlag, 1973), 108, 263, 279, (repro.), as Weidenbaum in der Bretagne and Le Saule.

Richard S. Field, Paul Gauguin: Monotypes, exh. cat. (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1973), 69, as Le Saule.

G[abriele] M[andel] Sugana, La obra pictórica completa de Gauguin (Barcelona: Noguer, 1973), no. 166, pp. 96–97, 119, (repro.), as El sauce.

Roger Cucchi, Gauguin à la Martinique: Le musée imaginaire complet de ses Peintures, Dessins, Sculptures, Céramiques, les Faux, les Lettres, les Catalogues d’Expositions (Vaduz, Liechtenstein: Calivran Anstalt, 1979), 73, as L’Automne en Bretagne.

Elda Fezzi, Tout Gauguin, trans. Simone Darses (1980; Paris: Flammarion, 1982), 1:84, (repro.), as Le saule.

G[abriele] M[andel] Sugana, Tout l’œuvre peint de Gauguin (Paris: Flammarion, 1981), no. 166, pp. 96–97, 117, 119, (repro.), as Le Saule.

Bogomila Welsh-Ovcharov, Vincent van Gogh and the Birth of Cloisonism, exh. cat. (Toronto: Art Gallery of Ontario, 1981), 220n1.

Important XIX and XX Century Works of Art, exh. cat. (London: Lefevre Gallery, 1983), 3, 14–15, (repro.), as Le Saule.

Nicholas Alfrey, “London: Nineteenth-Century French Exhibitions,” Burlington Magazine 125, no. 966 (September 1983): 569, as Le saule.

advertisement, Burlington Magazine 126, no. 970 (January 1984): v, (repro.), as Le Saule.

Denise Delouche, ed., Pont-Aven et ses peintres à propos d’un centenaire (Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes 2, 1986), 54, 78n9, as le Saule.

Paul Gauguin, exh. cat. (Tokyo: National Museum of Modern Art, 1987), 76–77, 82, 166–67, (repro.), as The Willow.

Richard Brettell et al., The Art of Paul Gauguin, exh. cat. (Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1988), 80, 179, as Le Saule (The Willow).

René Huyghe, Gauguin, trans. Helen C. Slonim, rev. ed. (New York: Crown, 1988), 26, 96, (repro.), as The Willow.

G[abriele] M[andel] Sugana, La obra pictórica completa de Gauguin (Barcelona: Planeta, 1988), no. 166, pp. 96–97, 119, (repro.), as El sauce.

Joan Minguet, Gauguin: His Life and Complete Works (Stamford, CT: Longmeadow Press, 1995), 99, (repro.), as The Willow.

Denise Delouche, Gauguin et la Bretagne (Rennes: Éditions Apogée, 1996), 60n2, as Le saule.

Ziva Amishai-Maisels et al., Paul Gauguin: Von der Bretagne nach Tahiti; Ein Aufbruch zur Moderne, exh. cat. (Tulln, Austria: Millenniumsverlag, 2000), 117n20, 118n55, 122, 254, as Le saule (Die Weide).

Daniel Wildenstein et al., Gauguin: A Savage in the Making; Catalogue Raisonné of the Paintings (1873–1888) (Paris: Wildenstein Institute, 2002), no. 347, pp. 2:346, 382, as Willow.

Marco Goldin, Gauguin, Van Gogh: L’avventura del colore nuovo, exh. cat. (Conegliano, Italy: Linea d’ombra libri, 2005), 358n1.

Rebecca Dimling Cochran and Bobbie Leigh, “100 Top Collectors Who Have Made a Difference,” Art and Antiques 29, no. 3 (March 2006): 90, as The Willow.

Bobbie Leigh, “Magnificent Obsession,” Art and Antiques 28, no. 6 (June 2006): 62, 65, as The Willow.

“Inaugural Exhibitions Celebrate Kansas City,” Member Magazine (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (Fall 2006): 3.

Pierre Sanchez, Dictionnaire du Salon d’Automne: Répertoire des Exposants et Liste des Œuvres Présentées (Dijon: Échelle de Jacob, 2006), 2:580, as L’Automne en Bretagne.

Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 10–11, 15–16, 116–21, 160, (repro,), as The Willow Tree (Le saule).

“Lasting Impressions: A Tribute to Marion and Henry Bloch,” Member Magazine (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (Fall 2007): 11.

Steve Paul, “Pretty Pictures: Marion and Henry Bloch’s collection of superb Impressionist masters,” Panache 4, no. 3 (Fall 2007): 20–24.

Stephen F. Eisenman, ed., Paul Gauguin: Artist of Myth and Dream, exh. cat. (Milan: Skira, 2007), 256.

“Kansas City Riches,” New York Times 159, no. 54,942 (February 5, 2010): C26.

Thomas M. Bloch, Many Happy Returns: The Story of Henry Bloch, America’s Tax Man (Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons, 2011), 174, as The Willow.

Diane Stafford, “Bloch gift to go for Nelson upgrade,” Kansas City Star 135, no. 203 (April 8, 2015): A8.

“World-Class Bloch Art Collection Will Be on Permanent View in Renovated Galleries at the Nelson-Atkins,” Artdaily.org (April 9, 2015): http://artdaily.com/news/77729/World-class-Bloch-Art-Collection-will-be-on-permanent-view-in-renovated-galleries-at-the-Nelson-Atkins#.VSayTFI5C9I.

“Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art officially accessions Bloch Impressionist masterpieces,” Artdaily.org (July 25, 2015): http://artdaily.com/news/80246/Nelson-Atkins-Museum-of-Art-officially-accessions-Bloch-Impressionist-masterpieces, as The Willow Tree.

Julie Paulais, “Le Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art reçoit des tableaux impressionnistes en échange de leurs répliques,” Le Journal des arts (July 30, 2015): http://www.lejournaldesarts.fr/site/archives/docs_article/129801/le-nelson-atkins-museum-of-art-recoit-des-tableaux-impressionnistes-en-echange-de-leurs-repliques.php.

Josh Niland, “The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Acquires a Renowned Collection of Impressionist and Postimpressionist Art,” architecturaldigest.com (August 6, 2015): https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/nelson-atkins-museum-accessions-bloch-art-collection.

Nancy Staab, “Van Gogh is a Go!” 435: Kansas City’s Magazine (September 2015): 76, as The Willow Tree.

Nina Siegal, “Upon Closer Review, Credit Goes to Bosch,” New York Times 165, no. 57130 (February 2, 2016): C5.

“Nelson-Atkins to unveil renovated Bloch Galleries of European Art in winter 2017,” Artdaily.org (July 20, 2016): http://artdaily.com/news/88852/Nelson-Atkins-to-unveil-renovated-Bloch-Galleries-of-European-Art-in-winter-2017-, as The Willow Tree.

Catherine Futter et al., Bloch Galleries: Highlights from the Collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2016), 108, (repro.).

Albert Hect, “Henry Bloch’s Masterpieces Collection to Go on Display at Nelson-Atkins Museum,” Jewish Business News (February 26, 2017): http://jewishbusinessnews.com/2017/02/26/henry-bloch-masterpieces-collection/.

David Frese, “Inside the Bloch Galleries: An interactive experience,” Kansas City Star 137, no. 169 (March 5, 2017): 1D, 4D, (repro.), as The Willow Tree.

“The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: Presenting the Bloch Galleries,” New York Times (March 5, 2017).

“Editorial: Thank you, Henry and Marion Bloch”, Kansas City Star (March 7, 2017): http://www.kansascity.com/opinion/editorials/ article137040948.html.

Hampton Stevens, “(Not Actually) 12 Things To Do During The Big 12 Tournament,” Flatland: KCPT’s Digital Magazine (March 9, 2017): http://www.flatlandkc.org/arts-culture/sports/not-actually-12-big-12-tournament/.

Laura Spencer, “The Nelson-Atkins’ Bloch Galleries feature Old Masterworks and New Technology,” KCUR (March 10, 2017): http://kcur.org/post/nelson-atkins-bloch-galleries-feature-old-masterworks-and-new-technology#stream/0.

Victoria Stapley-Brown, “Nelson-Atkins Museum’s new European art galleries come with a ‘love story’,” Art Newspaper (March 10, 2017): http://theartnewspaper.com/news/museums/nelson-atkins-museum-s-new-european-art-galleries-come-with-a-love-story/.

Harry Bellet, “Don du ciel pour le Musée Nelson-Atkins,” Le Monde (March 13, 2017): http://www.lemonde.fr/arts/article/2017/03/13/don-du-ciel-pour-le-musee-nelson-atkins_5093543_1655012.html.

Menachem Wecker, “Jewish Philanthropist Establishes Kansas City as Cultural Mecca,” Forward (March 14, 2017): http://forward.com/culture/365264/jewish-philanthropist-establishes-kansas-city-as-cultural-mecca/ [repr. in Menachem Wecker, “Kansas City Collection Is A Chip Off the Old Bloch,” Forward (March 17, 2017): 20–22].

Juliet Helmke, “The Bloch Collection Takes up Residence in Kansas City’s Nelson Atkins Museum,” BlouinArtInfo International, (March 15, 2017): http://www.blouinartinfo.com/news/story/2005267/the-bloch-collection-takes-up-residence-in-kansas-citys.

Erich Hatala Matthes, “Digital replicas are not soulless—they help us engage with art,” Apollo: The International Art Magazine (March 23, 2017): https://www.apollo-magazine.com/digital-replicas-3d-printing-original-artworks/.

Louise Nicholson, “How Kansas City got its magnificent museum,” Apollo: The International Art Magazine (April 7, 2017): https://www.apollo-magazine.com/how-kansas-city-got-its-magnificent-museum/.

André Cariou, Dessins de Gauguin: la Bretagne à l’œuvre (Paris: Hazan, 2017), 96, (repro), as Le Saule.

June Ellen Hargrove, Gauguin (Paris: Citadelles et Mazenod, 2017), 101–03, 422, (repro.), as Le Saule pleurer.

Robert D. Hershey Jr., “Henry Bloch, H&R Block’s cofounder, dies at 96,” Boston Globe (April 23, 2019), https://www3.bostonglobe.com/metro/obituaries/2019/04/23/henry-bloch-block-cofounder/?arc404=true.

Robert D. Hershey Jr., “Henry W. Bloch, Tax-Preparation Pioneer (and Pitchman), Is Dead at 96,” New York Times (April 23, 2019), https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/23/obituaries/henry-w-bloch-dead.html.

Claire Selvin, “Henry Wollman Bloch, Collector and Prominent Benefactor of Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Is Dead at 96,” ArtNews (April 23, 2019): http://www.artnews.com/2019/04/23/henry-bloch-dead-96/.

“Henry Wollman Bloch (1922–2019),” Art Forum (April 24, 2019): https://www.artforum.com/news/henry-wollman-bloch-1922-2019-79547.

Frank Morris, “Henry Bloch, Co-Founder Of H&R Block, Dies At 96,” npr.org (April 24, 2019): https://www.npr.org/2019/04/24/716641448/henry-bloch-co-founder-of-h-r-block-dies-at-96.

Ignacio Villarreal, “Nelson-Atkins mourns loss of Henry Bloch,” ArtDaily.org (April 24, 2019): http://artdaily.com/news/113035/Nelson-Atkins-mourns-loss-of-Henry-Bloch#.XMB76qR7laQ.

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “H&R Block co-founder, philanthropist Bloch dies,” Cass County Democrat Missourian 140, no. 29 (April 26, 2019): 1A.

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “KC businessman and philanthropist Henry Bloch dies,” Lee’s Summit Journal 132, no. 79 (April 26, 2019): 1A.

Luke Nozicka, “Family and friends remember Henry Bloch of H&R Block,” Kansas City Star 139, no. 225 (April 30 2019): 4A [repr. Luke Nozicka, “Family and friends remember Henry Bloch of H&R Block,” Kansas City Star 139, no. 228 (May 3, 2019): 3A].