![]()

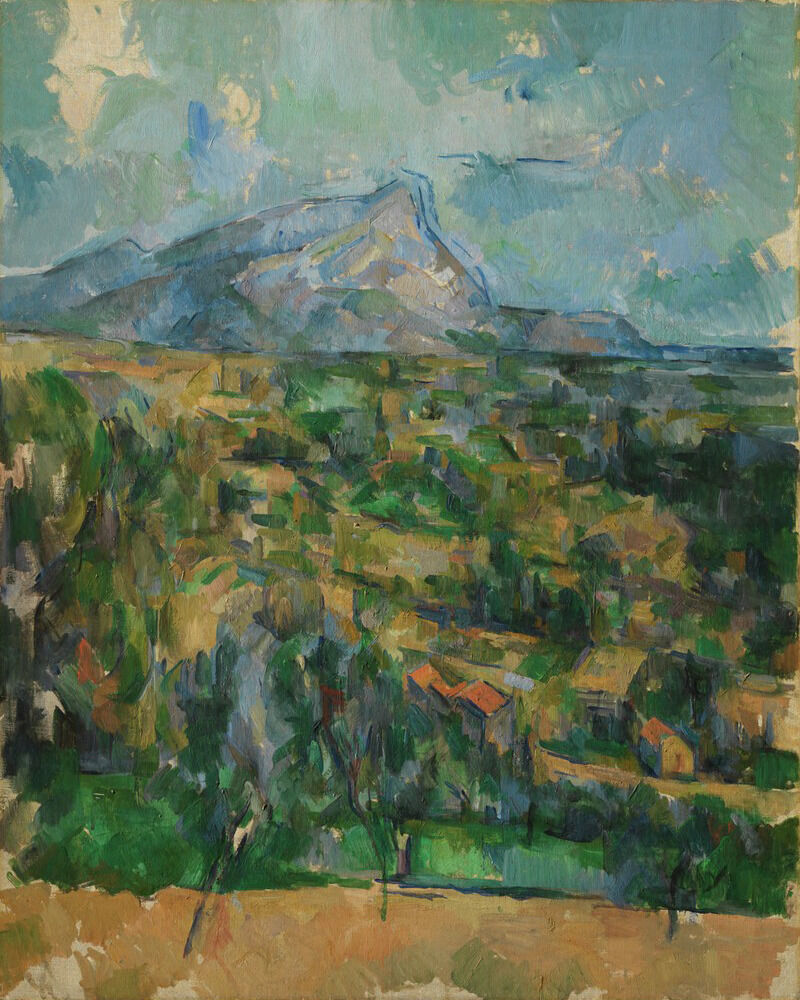

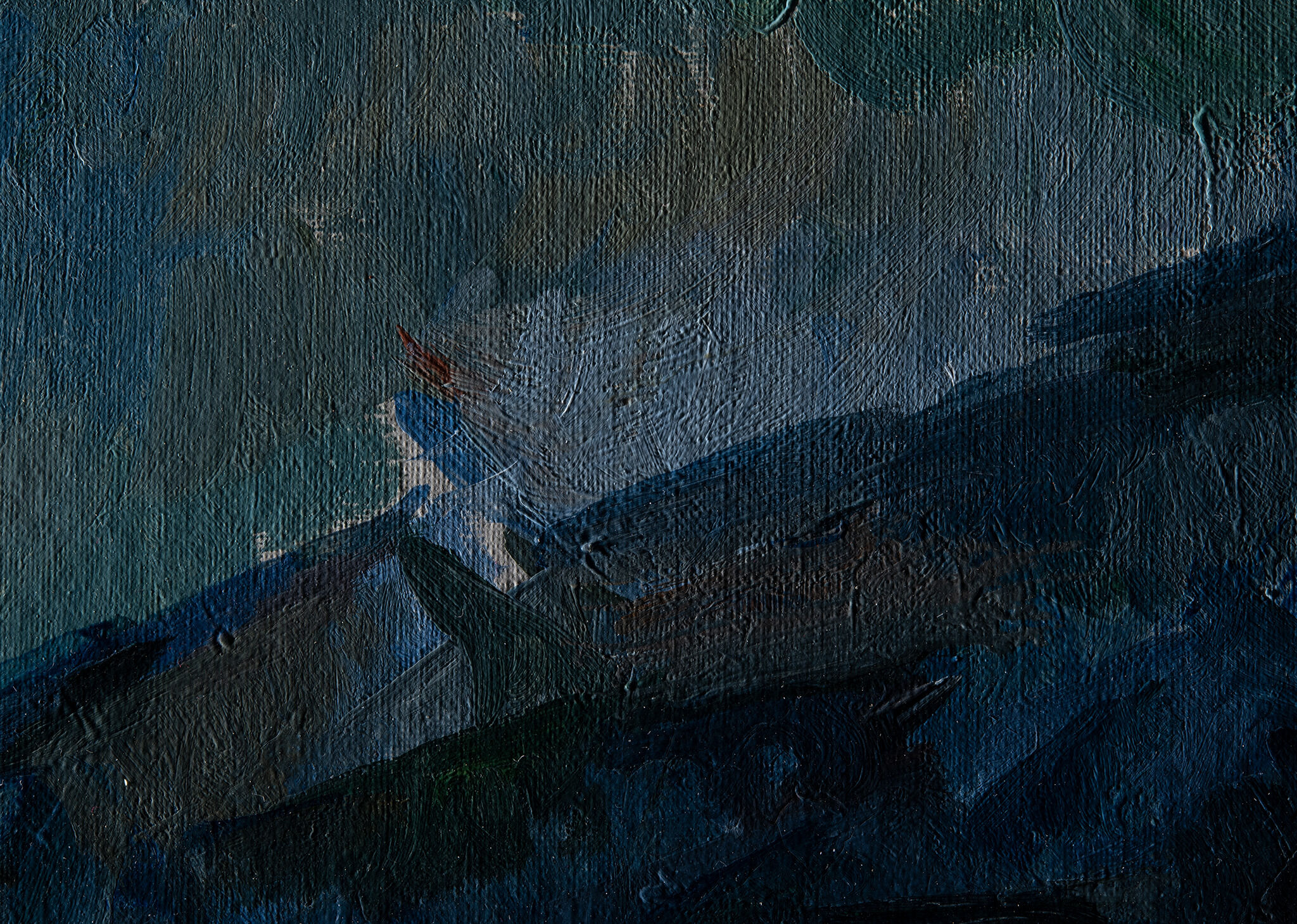

Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves, 1904–05

| Artist | Paul Cezanne, French, 1839–1906 |

| Title | Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves |

| Object Date | 1904–05 |

| Alternate and Variant Titles | La Montagne Sainte-Victoire; Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves; La Montagne Sainte-Victoire vue des Lauves |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (Unframed) | 25 1/8 x 32 1/8 in. (63.8 x 81.6 cm) |

| Credit Line | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 38-6 |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves, 1904–05,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.712.5407.

MLA:

Marcereau DeGalan, Aimee. “Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves, 1904–05,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.712.5407.

Writing from Aix-en-Provence to the artist Émile Bernard (1868–1941) in August 1905, Paul Cezanne remarked, “Time and contemplation modify our vision . . . and in the end, we receive understanding.”1Paul Cezanne to Émile Bernard, Friday, [1905], as cited in Michael Doran, ed., Conversations with Cézanne, trans. Julie Lawrence Cochran (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001), 47, letter 7. The letter was one of several exchanged between the two artists from 1904 to 1905, the time when Cezanne painted this work in which he ruminates on art and influence, life and death, the struggle for acceptance, and lasting memory. Cezanne died fourteen months later, on October 23, 1906, at age sixty-seven, reportedly painting in front of the landscape and the mountain he so loved. Cezanne made more than thirty oil paintings of Mont Sainte-Victoire, from a variety of vantage points, from the early 1880s until his death, continually seeking to understand his subject and also be understood himself.2Although Mont Sainte-Victoire appeared in the background of other works by Cezanne in the 1870s, it was not the central subject of his work until around 1883. Cezanne’s search for clarity and understanding is a continual refrain in his letters to Bernard.

Studying and painting directly from nature aligned Cezanne with Impressionists like Claude Monet (1840–1926), who also painted in series (for example, see Water Lilies). This method of working broke from the academic practice of painting a historical subject from one’s imagination in a studio. Yet Cezanne had an abiding interest in both the past and the present, in tradition and innovation, and these influences can be found in the Nelson-Atkins Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves.

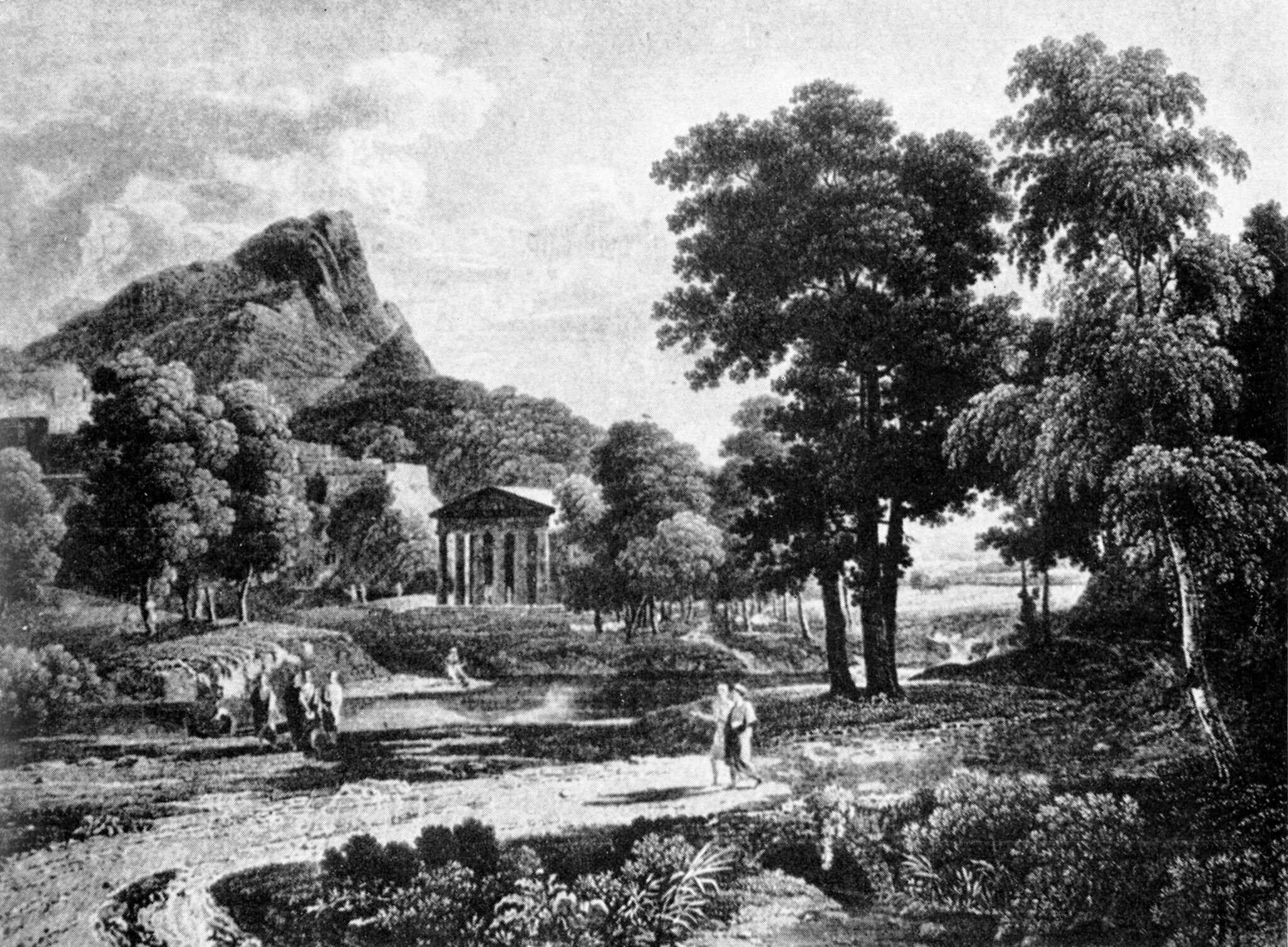

Cezanne activated and fulfilled his interest in the past through visits to the Louvre museum in Paris, registering as a copyist many times in the 1860s.4According to Theodore Reff, Cezanne registered as a copyist at the Louvre on November 20, 1863, as a pupil of Ernest Chesneau (1833–90). He began copying Poussin’s Shepherds of Arcadia on April 19, 1864. He registered again on February 13, 1868, as a pupil of Chesnau; however, no known copies correspond to this registration. Reff claims that copies Cezanne made of Sebastiano del Piombo’s Christ in Limbo were painted from a reproduction, and that those of Delacroix’s Dante and Virgil and Liberty Leading the People were painted in the Musée du Luxembourg, where the originals remained until 1874. See Theodore Reff, “Copyists in the Louvre, 1850–1870,” Art Bulletin 46, no. 4 (1964): 555n2. In 1870, the museum received its single-largest gift of fine art: a collection of 583 paintings from Paris-based collector Dr. Louis La Caze (1798–1869).5La Caze bequeathed 583 paintings to the museum upon his death in 1869. See Guillaume Faroult and Sophie Eloy, et al., La Collection La Caze: Chefs d’œuvre des peintures des XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles (Paris: Hazan, 2007). Significant works by sixteenth-century Italian artists, including Titian, Veronese, and Tintoretto; by seventeenth-century Dutch and Flemish artists, including Rembrandt van Rijn and Peter Paul Rubens; and by eighteenth-century French artists Jean Antoine Watteau, Jean Siméon Chardin, and Jean Honoré Fragonard, among others, strengthened the museum’s holdings. Cezanne returned to the Louvre following the Franco-Prussian WarFranco-Prussian War: The war of 1870–71 between France (under Napoleon III) and Prussia, in which Prussian troops advanced into France and decisively defeated the French at Sedan. The defeat marked the end of the French Second Empire. For Prussia, the proclamation of the new German Empire at Versailles was the climax of Bismarck’s ambitions to unite Germany. to witness this watershed addition to the collection, and he accessed the collection regularly thereafter. The Louvre became a secondary school to guide him in his evolution and understanding of the development of form, structure, and space.

Fig. 2. Peter Paul Rubens, Landscape with the Ruins of the Palatine Hill in Rome, ca. 1614–18, oil on wood, 30 x 42 1/8 in. (76x 107 cm), Musée du Louvre, Paris, MI 966. Photo: RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Franck Raux

Fig. 2. Peter Paul Rubens, Landscape with the Ruins of the Palatine Hill in Rome, ca. 1614–18, oil on wood, 30 x 42 1/8 in. (76x 107 cm), Musée du Louvre, Paris, MI 966. Photo: RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Franck Raux

Fig. 3. Karel DuJardin, White Horse in an Italian Landscape, ca. 1670–80, oil on canvas, 21 x 17 7/16 in. (53.5 x 44.3 cm), Musée du Louvre, Paris, MI 935. Photo: RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Tony Querrec

Fig. 3. Karel DuJardin, White Horse in an Italian Landscape, ca. 1670–80, oil on canvas, 21 x 17 7/16 in. (53.5 x 44.3 cm), Musée du Louvre, Paris, MI 935. Photo: RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Tony Querrec

Cezanne absorbed many influences from the old masters, but he was especially keen on seventeenth-century artists. Rubens, particularly his use of space, figures prominently in Cezanne’s letters from his later years.9See the conversation between Joachim Gasquet and Cezanne in Doran, Conversations with Cézanne, 153–54. The archaeologist Jules Borély recounts a visit he had with Cezanne in 1902, in which the artist “stretched out his arm to measure the bell tower of the cathedral between his thumb and index finger.” Borély recalled that Cezanne remarked, “How little it takes to transform a thing. . . . I try and it’s hard for me. Monet has that rare talent; he looks and can immediately draw in proportion. He takes it here and puts it there; it’s the gesture of a Rubens.”10Jules Borély, “Cezanne à Aix,” as cited in Doran, Conversations with Cézanne, 20–21. At this point late in Cezanne’s career, whether realizing it or not, he too was able to draw in proportion. He may have employed some type of measuring device in delineating the zones in the Nelson-Atkins canvas, because the sky and the middle ground are exactly the same width, whereas the foreground is half the width of the other two zones. There is no technical evidence of the artist’s use of a stylus or other device to measure these zones,11See accompanying technical entry by Diana Jaskierny. so he may have used a combination of an outstretched arm, thumb, and forefinger.

Cezanne’s subtle homage to the Old Masters signaled his allegiance to them while, at the same time, announcing his modernity.12See Judit Geskó, ed., Cézanne and the Past: Tradition and Creativity (Budapest: Museum of Fine Arts, 2012). Writing to Bernard in 1905, Cezanne noted, “The Louvre is the book in which we learn to read. We must now, however, be satisfied with memorizing the attractive formulas of our predecessors. We must leave the museum to study Nature in all its beauty.”13Cezanne to Bernard, Friday [1905]. And study nature he did, directly and en plein airen plein air (adjective: plein-air): French for “outdoors.” The term is used to describe the act of painting quickly outside rather than in a studio., with Camille Pissarro (1830–1903) and Armand Guillaumin (1841–1927) in the 1870s outside of Paris and the surrounding Île de France area. This was a period of great personal development for Cezanne, as he worked to gain clarity of form and color through the development of short and close parallel brushstrokes in subtle tonal gradations, known as “constructive strokes.”14“The constructive stroke” was a term first used by Theodore Reff to describe the parallel brushwork often seen in Cezanne’s paintings. See Reff, “Cézanne’s Constructive Stroke,” Art Quarterly 25, no. 3 (Autumn 1962): 214–27. Through this method, Cezanne built form through color, yet because of his unified tones, the spaces appear flattened. Although credit is largely given to Pissarro for prompting Cezanne’s development in this phase of his career, the latter was also very aware of the sense of structural solidity within Guillaumin’s brushwork in the early 1870s, with its emphasis on architectural forms.15Danielle Hampton Cullen draws these connections in her forthcoming entry for this catalogue on Armand Guillaumin, Landscape, Ivry-sur-Seine, https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.621. Hampton Cullen’s entry builds on John Rewald, “Cézanne and Guillaumin,” in Études d’art Français offertes à Charles Sterling (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1975), 344, 346–47. See also James H. Rubin’s chapter, “Armand Guillaumin and Paul Cézanne in Ile-de-France,” in Denis Coutagne, Cézanne and Paris, exh. cat. (Paris: Éditions de la RMN-Grand Palais, 2011), 67–68. Evidence of this type of brushwork can be found in Guillaumin’s early landscape of Ivry-sur-Seine in the Nelson-Atkins collection.

As Cezanne developed his style and moved from canvases covered entirely in tightly controlled parallel brushstrokes to those in which he allowed the primed white of the canvas to show through, as in Mont Sainte-Victoire, questions invariably arise among scholars about finish. While acknowledging the increasing difficulties he faced due to his advancing age, Cezanne wrote to Bernard around the time he painted the Nelson-Atkins painting, remarking, “It’s sad to have to note that the improvement that manifests itself in the understanding of nature, with respect to the picture and the development of the means of expression, should be accompanied by age and the weakening of the body.”16John Rewald, ed., Paul Cezanne: Correspondence (Paris: 1978), 313, as cited in Felix Andreas Baumann, ed., Cézanne: Finished, Unfinished, trans. Isabel Fede (Ostfildern Ruit: Hatje Cantz, 2000), 346. He struggled with diabetes and related eye issues and lamented in another letter to Bernard that “now old as I am, nearly 70, —color sensations, which make light in my painting, create abstractions that keep me from covering my canvas or defining the edge of objects where they delicately touch other objects, with the result that my image or picture is incomplete.”17According to ophthalmologists P. Ivanišević and M. Ivanišević, Paul Cezanne was diagnosed with diabetes in 1890 at age fifty-one. “A triggering factor was emerald green poisoning caused by his painting ‘a la couillarde,’ which is crude painting with his fingers. Diabetes induced concurrent retinopathy, causing blue-green color blindness.” See P. Ivanišević and M. Ivanišević, “Retinal Diseases and Painting,” Collegium Antropologicum 39, no. 1 (2015): 243–46, https://www.collantropol.hr/antropo/article/view/316. See also Cezanne to Bernard, October 23, 1905, in Doran, Conversations with Cézanne, 48, letter 8. Cezanne was also nearsighted but refused to get glasses. These ailments, in tandem with his age, made him feel that time was running out, which may have pushed him to work more quickly.18Birgit Schwarz cites Joachim Gasquet, “Ce qu’il m’a dit . . . ” (1921), in Doran, Conversations with Cézanne, 110, in her catalogue entry in Baumann, Cézanne: Finished, Unfinished, 346n2. Indeed, there is no underdrawingunderdrawing: A drawn or painted sketch beneath the paint layer. The underdrawing can be made from dry materials, such as graphite or charcoal, or wet materials, such as ink or paint. evident in the Nelson-Atkins composition;19See accompanying technical entry by Diana M. Jaskierny. however, he did leave space for the mountain in reservereserve: An area of the composition left unpainted with the intention of inserting a feature at a later stage in the painting process., sketching its contours with a few deft strokes of dark blue paint. In addition to passages of wet-into-wetwet-into-wet: An oil painting technique which involves blending of colors on the picture surface. brushwork, there are also passages of wet-over-drywet-over-dry: An oil painting technique that involves layering paint over an already dried layer, resulting in no intermixing of paint or disruption to the lower paint strokes. media, suggesting that while he may have worked quickly in the former areas, more time passed between paint application in the latter areas.

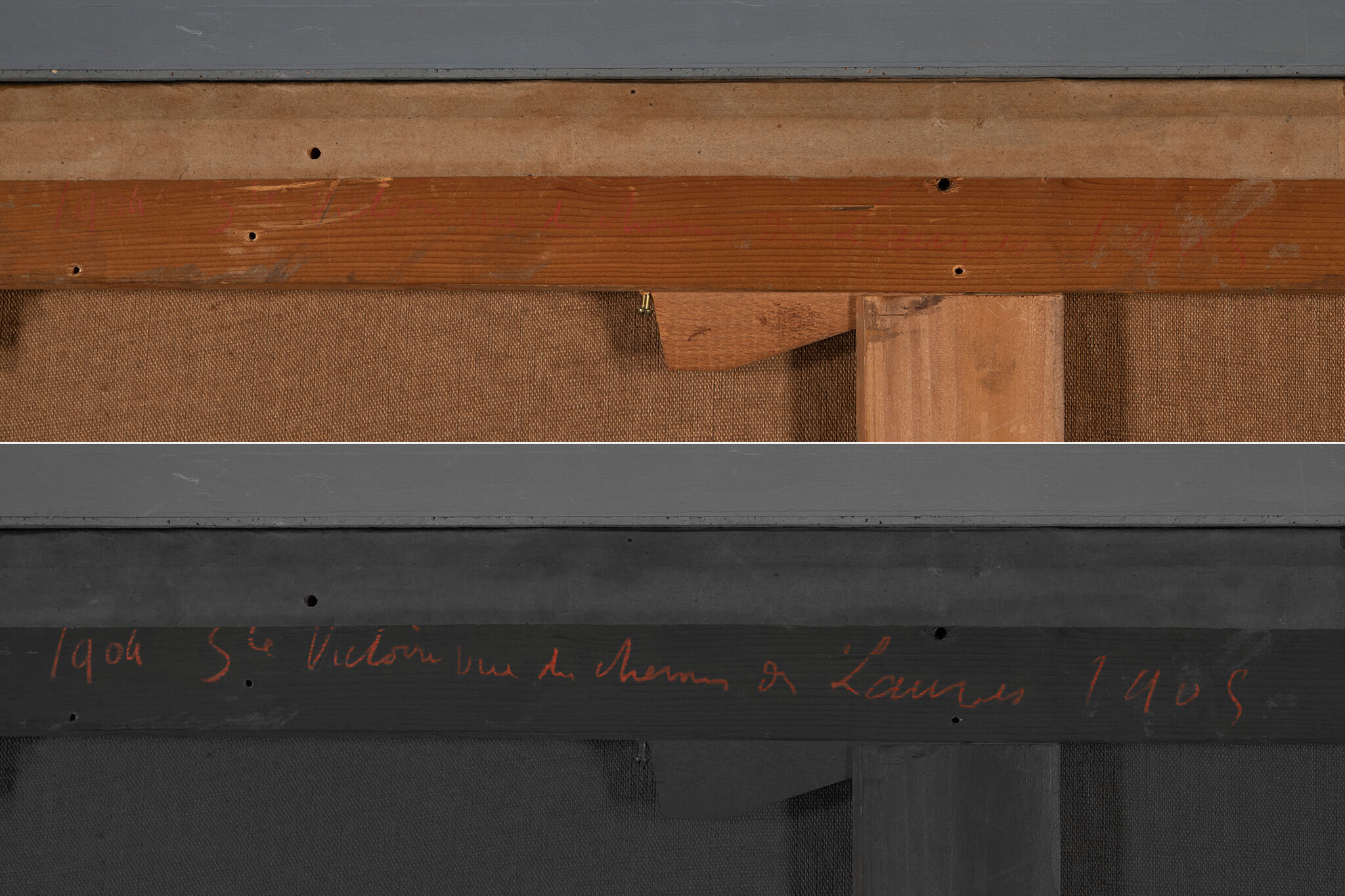

The Nelson-Atkins canvas was one of ten views of Mont Sainte-Victoire dispersed from Cezanne’s studio in Aix-en-Provence shortly after his death in October 1906, purchased jointly by Cezanne’s former dealer Ambroise Vollard and the Galerie Bernheim-Jeune in two lots: February 12, 1907, and March 11, 1907. Recorded in Vollard’s second stock book, the Nelson-Atkins picture was part of the March sale.20Rebecca A. Rabinow, ed., Cézanne to Picasso: Ambroise Vollard, Patron of the Avant-Garde, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2006), 345. See also Jayne Warman to Brigid M. Boyle, April 3, 2020, NAMA curatorial files. Although the painting was relinedlining: A procedure used to reinforce a weakened canvas that involves adhering a second fabric support using adhesive, most often a glue-paste mixture, wax, or synthetic adhesive. and its tacking marginstacking margins: The outer edges of canvas that wrap around and are attached to the stretcher or strainer with tacks or staples. See also tacking edge. removed at some point early in its history,21See accompanying technical essay by Diana M. Jaskierny. a verso sticker with a Vollard stock number, 4477, suggests that the stretcher is indeed original. In addition to the Vollard verso sticker, a faint red chalk inscription across the top of the stretcher bar reads, “1904 Ste Victoire vue du Chemin du Lauves 1905” (Fig. 5). According to independent art historian Jayne Warman, the inscription is not in Cezanne’s son’s hand, and she remains doubtful that it is in the artist’s hand.22See email exchange between Brigid M. Boyle and Jayne Warman, February 21, 2022, NAMA curatorial files. A comparison of handwriting between several individuals in the painting’s early provenance suggests that the handwriting is closest to Vollard’s.23I have looked through several letters from Vollard to various individuals from roughly 1880 to 1907, noting several similarities in his handwriting to the verso inscription on the Nelson-Atkins canvas. Although Vollard often signs his name with a loop in the capital “V,” and there is no visible loop in the verso inscription, some of the letters Vollard writes from 1905 incorporate a similar “s” shape for the 5, which is distinct. There is also a kinship with the letters and the verso inscription in the way the letters “ch” are connected; a smaller, open “4” is used for the date; and the way he connects the “v” to the top of the “u” in the word “vue,” all of which relate to the verso inscription. Comparisons of handwriting with others connected to the painting’s provenance, including Bernheim-Jeune and Carl Montag, proved more definitely not to be a match.

Fig. 5. Detail of verso of Paul Cezanne, Mont Saint Victoire Seen from Les Lauves (1904–05): inscription in red wax pencil or crayon on the top stretcher member in normal viewing light (above) and digitally enhanced for legibility (below)

Fig. 5. Detail of verso of Paul Cezanne, Mont Saint Victoire Seen from Les Lauves (1904–05): inscription in red wax pencil or crayon on the top stretcher member in normal viewing light (above) and digitally enhanced for legibility (below)

Fig. 6. Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire, 1904–06, oil on canvas, 33 x 25 5/8 in. (83.8 x 65.1 cm), The Henry and Rose Pearlman Foundation, on loan since 1976 to the Princeton University Art Museum, L.1988.62.5

Fig. 6. Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire, 1904–06, oil on canvas, 33 x 25 5/8 in. (83.8 x 65.1 cm), The Henry and Rose Pearlman Foundation, on loan since 1976 to the Princeton University Art Museum, L.1988.62.5

Cezanne’s preoccupation with this motif, this mountain—which was the site of struggle during the ancient era, and which figured in his work for over twenty years in a multitude of formats and from a variety of vantage points—came into sharper focus one month before his death. He wrote to Bernard apologizing for returning to the same subject again and again:

. . . but I believe in the logical development of what we see and feel through studying nature, free from preoccupation with methods, methods being only simple means for us to make the public feel what we feel and to make ourselves accepted. The masters whom we admire probably did no more.26Cezanne to Bernard, September 21, 1906, as cited in Doran, Conversations with Cézanne, 49, letter 9.

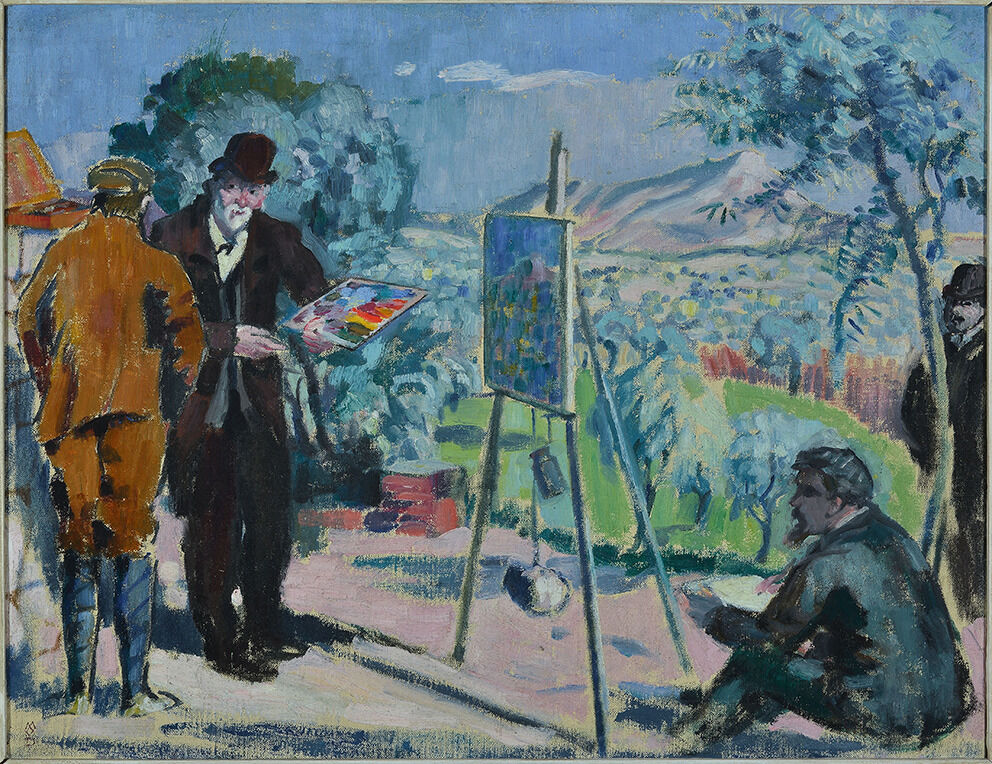

After twenty years of absorbing the lessons of these masters, including Rubens, DuJardin, Bertin, and many others, tempered with new techniques and brushwork of Cezanne’s contemporaries, time and contemplation had, in fact, modified Cezanne’s vision. In the end, he received the understanding for which he so longed as he stood before his beloved mountain with Denis and Roussel, as if to pass on these lessons through his art—as a lasting monument, much like the mountain itself, raised by struggle to his own glory.27This is Émile Bernard’s opinion, as expressed in Doran, Conversations with Cézanne, 78.

Notes

-

Paul Cezanne to Émile Bernard, Friday, [1905], as cited in Michael Doran, ed., Conversations with Cézanne, trans. Julie Lawrence Cochran (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001), 47, letter 7.

-

Although Mont Sainte-Victoire appeared in the background of other works by Cezanne in the 1870s, it was not the central subject of his work until around 1883. Cezanne’s search for clarity and understanding is a continual refrain in his letters to Bernard.

-

As cited in Doran, Conversations with Cézanne, 56.

-

According to Theodore Reff, Cezanne registered as a copyist at the Louvre on November 20, 1863, as a pupil of Ernest Chesneau (1833–90). He began copying Poussin’s Shepherds of Arcadia on April 19, 1864. He registered again on February 13, 1868, as a pupil of Chesnau; however, no known copies correspond to this registration. Reff claims that copies Cezanne made of Sebastiano del Piombo’s Christ in Limbo were painted from a reproduction, and that those of Delacroix’s Dante and Virgil and Liberty Leading the People were painted in the Musée du Luxembourg, where the originals remained until 1874. See Theodore Reff, “Copyists in the Louvre, 1850–1870,” Art Bulletin 46, no. 4 (1964): 555n2.

-

La Caze bequeathed 583 paintings to the museum upon his death in 1869. See Guillaume Faroult and Sophie Eloy, et al., La Collection La Caze: Chefs d’œuvre des peintures des XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles (Paris: Hazan, 2007).

-

We know, for example, that Cezanne sketched the Flemish master’s Marie de Medici cycle at the Louvre. For more on Rubens and his legacy among artists ranging from Anthony van Dyck to Cezanne, see Nico van Hout, Rubens and His Legacy (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2014).

-

The notch appears in a watercolor study Cezanne painted, which is in the Tate Collection. The museum dates it to 1905–06; however, it appears with a wider date range of 1902–06 in Christopher Lloyd, Paul Cézanne: Drawings and Watercolours (London: Thames and Hudson, 2019), 233.

-

See Theodore Reff, “Reproductions and Books in Cezanne’s Studio,” Gazette des Beaux Arts 56, no. 1102 (November 1960): 303–09. Although it is impossible to determine a complete account of Cezanne’s studio contents at his death because family members removed many items, Reff’s article assembles a list of items culled from artist recollections in addition to what remained. Examples include reproductive prints by Rubens, among many others.

-

See the conversation between Joachim Gasquet and Cezanne in Doran, Conversations with Cézanne, 153–54.

-

Jules Borély, “Cezanne à Aix,” as cited in Doran, Conversations with Cézanne, 20–21.

-

See accompanying technical entry by Diana Jaskierny.

-

See Judit Geskó, ed., Cézanne and the Past: Tradition and Creativity (Budapest: Museum of Fine Arts, 2012).

-

Cezanne to Bernard, Friday [1905].

-

“The constructive stroke” was a term first used by Theodore Reff to describe the parallel brushwork often seen in Cezanne’s paintings. See Reff, “Cézanne’s Constructive Stroke,” Art Quarterly 25, no. 3 (Autumn 1962): 214–27.

-

Danielle Hampton Cullen draws these connections in her forthcoming entry for this catalogue on Armand Guillaumin, Landscape, Ivry-sur-Seine, https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.621. Hampton Cullen’s entry builds on John Rewald, “Cézanne and Guillaumin,” in Études d’art Français offertes à Charles Sterling (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1975), 344, 346–47. See also James H. Rubin’s chapter, “Armand Guillaumin and Paul Cézanne in Ile-de-France,” in Denis Coutagne, Cézanne and Paris, exh. cat. (Paris: Éditions de la RMN-Grand Palais, 2011), 67–68.

-

John Rewald, ed., Paul Cezanne: Correspondence (Paris: Bernard Grasset, 1978), 313, as cited in Felix Andreas Baumann, ed., Cézanne: Finished, Unfinished, trans. Isabel Fede (Ostfildern Ruit: Hatje Cantz, 2000), 346.

-

According to ophthalmologists P. Ivanišević and M. Ivanišević, Paul Cezanne was diagnosed with diabetes in 1890 at age fifty-one. “A triggering factor was emerald green poisoning caused by his painting ‘a la couillarde,’ which is crude painting with his fingers. Diabetes induced concurrent retinopathy, causing blue-green color blindness.” See P. Ivanišević and M. Ivanišević, “Retinal Diseases and Painting,” Collegium Antropologicum 39, no. 1 (2015): 243–46, https://www.collantropol.hr/antropo/article/view/316. See also Cezanne to Bernard, October 23, 1905, in Doran, Conversations with Cézanne, 48, letter 8. Cezanne was also nearsighted but refused to get glasses.

-

Birgit Schwarz cites Joachim Gasquet, “Ce qu’il m’a dit . . . ” (1921), in Doran, Conversations with Cézanne, 110, in her catalogue entry in Baumann, Cézanne: Finished, Unfinished, 346n2.

-

See accompanying technical entry by Diana M. Jaskierny.

-

Rebecca A. Rabinow, ed., Cézanne to Picasso: Ambroise Vollard, Patron of the Avant-Garde, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2006), 345. See also Jayne Warman to Brigid M. Boyle, April 3, 2020, NAMA curatorial files.

-

See accompanying technical essay by Diana M. Jaskierny.

-

See email exchange between Brigid M. Boyle and Jayne Warman, February 21, 2022, NAMA curatorial files.

-

I have looked through several letters from Vollard to various individuals from roughly 1880 to 1907, noting several similarities in his handwriting to the verso inscription on the Nelson-Atkins canvas. Although Vollard often signs his name with a loop in the capital “V,” and there is no visible loop in the verso inscription, some of the letters Vollard writes from 1905 incorporate a similar “s” shape for the 5, which is distinct. There is also a kinship with the letters and the verso inscription in the way the letters “ch” are connected; a smaller, open “4” is used for the date; and the way he connects the “v” to the top of the “u” in the word “vue,” all of which relate to the verso inscription. Comparisons of handwriting with others connected to the painting’s provenance, including Bernheim-Jeune and Carl Montag, proved more definitely not to be a match.

-

Scholars continue to revise the dating of Cezanne’s Mont Saint-Victoire paintings. Some historians date the Nelson-Atkins picture to 1902–06, but others propose 1904–06. See Walter Feilchenfeldt, Jayne Warman, and David Nash, “La Carrière de Bibémus, 1898–1900 (FWN 353),” The Paintings, Watercolors and Drawings of Paul Cezanne: An Online Catalogue Raisonné, accessed March 16, 2022, https://www.cezannecatalogue.com/catalogue/entry.php?id=814.

-

Comparisons with both Philadelphia canvases (catalogue raisonné nos. FWN 351 and FWN 352), as well as the Metropolitan Museum of Art (FWN 356), all dated 1902–06, do not present the same degree of banding in the landscape as in the Nelson-Atkins composition. All were left in the artist’s studio and dispersed after his death.

-

Cezanne to Bernard, September 21, 1906, as cited in Doran, Conversations with Cézanne, 49, letter 9.

-

This is Émile Bernard’s opinion, as expressed in Doran, Conversations with Cézanne, 78.

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Diana M. Jaskierny, “Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves, 1904–05,” technical entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.712.2088.

MLA:

Jaskierny, Diana M. “Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves, 1904–05,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.712.2088.

Painted near the end of Paul Cezanne’s (1839–1906) career, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves embodies a range of techniques that the artist developed throughout his oeuvre, including the evolution of the constructive stroke.1“The constructive stroke” was a term first used by Theodore Reff to describe the parallel brushwork often seen in Cezanne’s paintings. Dennis Farr and John House, eds., Impressionist and Post-Impressionist Masterpieces: The Courtauld Collection (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987), cat. 23. The painting was completed on a fine, plain-weaveplain weave: A basic textile weave in which one weft thread alternates over and under the warp threads. Often this structure consists of one thread in each direction, but threads can be doubled (basket weave) or tripled to create more complex plain weave. Plain weave is sometimes called tabby weave. canvas and is affixed to a six-member stretcherstretcher: A wooden structure to which the painting’s canvas is attached. Unlike strainers, stretchers can be expanded slightly at the joints to improve canvas tension and avoid sagging due to humidity changes or aging.. Early in the painting’s history, the tacking marginstacking margins: The outer edges of canvas that wrap around and are attached to the stretcher or strainer with tacks or staples. See also tacking edge. were removed and the painting was linedlining: A procedure used to reinforce a weakened canvas that involves adhering a second fabric support using adhesive, most often a glue-paste mixture, wax, or synthetic adhesive.. It appears the canvas retained its original size through this intervention, though possibly with slight adjustments. As part of the lining process, paper tape was added to all four edges, further limiting information about the canvas. Along the left and bottom edges, the paint layer appears to stop at the interface of the paper tape. In contrast, along the top and right edges, the paint layer extends beneath the paper tape and to the edge of the original canvas.2Due to the central placement of the mountain, it is unlikely that the canvas was significantly cropped in any way. Based on the existing dimensions, the canvas used was a standard-size formatstandard-format supports: Commercially prepared supports available through art suppliers, which gained popularity in the nineteenth century during the industrialization of art materials. Available in three formats figure (portrait), paysage (landscape), and marine (marine), these were numbered 1 through 120 to indicate their size. For each numbered size, marine and paysage had two options available: a larger format (haute) and smaller (basse) format. no. 25 portrait, rotated 90 degrees.3Near the end of his career, Cezanne frequently used standard-format no. 25 canvases, and from 1885 on, “almost 45 percent of his canvases were of those dimensions [81 centimeters] or larger.” Robert Jenson, “Vollard and Cezanne: An Anatomy of a Relationship,” in Cezanne to Picasso: Ambroise Vollard, Patron of the Avant-Garde, ed. Rebecca A. Rabinow (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2006), 44.

The ground layerground layer: An opaque preparatory layer applied to the support, either commercially or by the artist, to prevent absorption of the paint into the canvas or panel. See also priming layer., opaque and slightly off-white or pale gray in color, is visible throughout the composition, most noticeably in the sky and foreground (Fig. 7).4Through microscopic examination, some black and yellow pigment particles are visible. Although present, these particles are sparser than in most colored grounds. This layer is thinly and evenly applied, indicating commercial preparation. With exposed ground visible throughout the composition, it appears there was little to no imprimaturaimprimatura: A thin layer of paint applied over the ground layer to establish an overall tonality. laid in during the early stages of painting.

Fig. 7. Detail of the exposed ground in the sky, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves (1904–05)

Fig. 7. Detail of the exposed ground in the sky, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves (1904–05)

Fig. 8. Photomicrograph of a purplish-blue painted line below the paint in the left tree, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves (1904–05)

Fig. 8. Photomicrograph of a purplish-blue painted line below the paint in the left tree, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves (1904–05)

The composition was overwhelmingly created with thinly applied paint and little impastoimpasto: A thick application of paint, often creating texture such as peaks and ridges..7Some impasto appears to have been impacted by the lining process, reducing its height slightly. While in many places wet-over-wetwet-over-wet: An oil painting technique which involves drawing a stroke of one color across the wet paint of another color. paint application is visible, revealed by displaced paint and inadvertent blending, throughout the painting it is evident that Cezanne frequently layered paint after sections had dried. This is especially noticeable in raking lightraking light: An examination technique in which light is placed at a shallow angle from one direction to reveal the surface topography., where the texture of lower brushstrokes can be seen through the top layer (Fig. 9). By layering the paint in this manner, it is clear Cezanne completed the painting over the course of multiple sessions, as he was known to do.8It is believed that some paintings required dozens of sittings to complete. Erle Loran, Cézanne’s Composition: Analysis of His Form with Diagrams and Photographs of His Motifs (1943; Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006), 26. See also Anthea Callen, Techniques of the Impressionists (1980; London: Tiger Books International, 1990), 72, 114.

Fig. 9. Raking light detail of the sky, showing wet-over-dry brushstrokes, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves (1904–05)

Fig. 9. Raking light detail of the sky, showing wet-over-dry brushstrokes, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves (1904–05)

Fig. 10. Detail of horizonal and vertical brushstrokes in the middle ground, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves (1904–05)

Fig. 10. Detail of horizonal and vertical brushstrokes in the middle ground, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves (1904–05)

Fig. 12. Detail of dashed blue outline of the mountaintop, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves (1904–05)

Fig. 12. Detail of dashed blue outline of the mountaintop, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves (1904–05)

Fig. 13. Detail of smaller trees on the right, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves (1904–05)

Fig. 13. Detail of smaller trees on the right, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves (1904–05)

The blue line is again used to create the twisting trunks and branches of the foreground trees. At first glance, it appears the trees on the right are little more than stumps, with intersecting horizontal lines truncating their shapes at the top of the foreground, suggesting that their rendering was still in progress (Fig. 13). Interestingly, similar intersecting lines are also present across saplings in Normandy Farm, Summer (Hattenville) (ca. 1882; private collection).16Farr and House, Impressionist and Post-Impressionist Masterpieces: The Courtauld Collection, cat. 22. See also House, “Cat. 2, Ferme Normande, été (Hattenville),” in Buck et al., The Courtauld Cézannes, 78. When comparing the Nelson-Atkins composition to another from the same vantage point, Mont Sainte-Victoire (Fig. 6), the same small trees are present, again with their foliage blending seamlessly into the middle ground. While the concept of “finish” is difficult to define, in this instance both the Nelson-Atkins and Pearlman Foundation paintings likely illustrate a range of mature and young trees interweaving between the middle ground and foreground.

The painting is in good condition. Prior to its history at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, the painting was fully lined. Subtle weave interferenceweave interference: A distortion that can occur when excess heat or pressure is applied to a painting, usually during the lining process. As a result, the original canvas weave texture becomes more pronounced or the weave texture of the lining material becomes visible on the painting surface. Also called weave emphasis or weave accentuation. due to the lining process is visible when viewing the painting in raking light. Minimal retouchingretouching: Paint application by a conservator or restorer to cover losses and unify the original composition. Retouching is an aspect of conservation treatment that is aesthetic in nature and that differs from more limited procedures undertaken solely to stabilize original material. Sometimes referred to as inpainting or retouch. is present on the painting. A low-concentration synthetic varnish saturates the paint layer while creating a healthy but unvarnished appearance, allowing variations of the paint’s luster to remain visible.17Solvent testing conducted in 2022 confirmed the varnish classification.

Notes

-

“The constructive stroke” was a term first used by Theodore Reff to describe the parallel brushwork often seen in Cezanne’s paintings. Dennis Farr and John House, eds., Impressionist and Post-Impressionist Masterpieces: The Courtauld Collection (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987), cat. 23.

-

Due to the central placement of the mountain, it is unlikely that the canvas was significantly cropped in any way.

-

Near the end of his career, Cezanne frequently used standard-format no. 25 canvases, and from 1885 on, “almost 45 percent of his canvases were of those dimensions [81 centimeters] or larger.” Robert Jenson, “Vollard and Cezanne: An Anatomy of a Relationship,” in Cezanne to Picasso: Ambroise Vollard, Patron of the Avant-Garde, ed. Rebecca A. Rabinow (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2006), 44.

-

Through microscopic examination, some black and yellow pigment particles are visible. Although present, these particles are sparser than in most colored grounds.

-

A dilute blue line was also found in the foreground below the paint layer but did not appear related to any part of the composition.

-

Elisabeth Reissner, “Ways of Making: Practice and Innovation in Cézanne’s Paintings in the National Gallery,” National Gallery Technical Bulletin 25 (2008): 11–15.

-

Some impasto appears to have been impacted by the lining process, reducing its height slightly.

-

It is believed that some paintings required dozens of sittings to complete. Erle Loran, Cézanne’s Composition: Analysis of His Form with Diagrams and Photographs of His Motifs (1943; Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006), 26. See also Anthea Callen, Techniques of the Impressionists (1980; London: Tiger Books International, 1990), 72, 114.

-

See the technical entry for Quarry at Bibémus for another example of the constructive stroke: Diana M. Jaskierny, “Paul Cezanne, Quarry at Bibémus, 1895–1900,” technical entry in Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, ed., French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.710.2088.

-

For a discussion on the various standardized marks, or taches, of Cezanne, see Øystein Sjåstad, A Theory of the Tache in Nineteenth-Century Painting (Surrey, UK: Ashgate, 2014), 94–96.

-

Although completed a decade earlier, the brushwork in Hillside in Provence (ca. 1890–92; The National Gallery, London) is similarly divided into zones with differing brushwork in each zone. David Bomford, Jo Kirby, John Leighton, and Ashok Roy, Art in the Making: Impressionism (London: Yale University Press, 1991), 198.

-

This application is also described as “intense scrambling.” Sjåstad, A Theory of the Tache in Nineteenth-Century Painting, 95.

-

Another example with looser brushwork found later in Cezanne’s career is Le Lac d’Annecy (1896; The Courtauld Gallery, London). John House, “Cat. 9 Le Lac d’Annecy,” in The Courtauld Cézannes, ed. Stephanie Buck, John House, Ernst Vegelin van Claerbergen, and Barnaby Wright (London: The Courtauld Gallery, 2008), 102–05. For further discussion on his later brushwork, see Farr and House, Impressionist and Post-Impressionist Masterpieces: The Courtauld Collection, cat. 24.

-

Bernard Dunstan, Painting Methods of the Impressionists (New York: Watson-Guptill, 1983), 91.

-

This passage and blocking of light and color is seen repeatedly in Cezanne’s compositions. Loran, Cézanne’s Composition, 26.

-

Farr and House, Impressionist and Post-Impressionist Masterpieces: The Courtauld Collection, cat. 22. See also House, “Cat. 2, Ferme Normande, été (Hattenville),” in Buck et al., The Courtauld Cézannes, 78.

-

Solvent testing conducted in 2022 confirmed the varnish classification.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves, 1904–05,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.712.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves, 1904–05,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.712.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves, 1904–05,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.712.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid. “Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves, 1904–05,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.712.4033.

Paul Cezanne (1839–1906), Aix-en-Provence, 1905–October 22, 1906;

Artist’s estate, Aix-en-Provence, 1906–March 11, 1907;

Purchased from the artist’s estate by Ambroise Vollard, Paris, stock book B, no. 4477, on joint account with the Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, Paris, as Paysage. Ste. Victoire à 3 plans, 1907–no later than 1936 [1];

With Ambroise Vollard, Paris, by 1936 [2];

With Montag, by July 1937 [3];

Purchased from Montag by Wildenstein and Company, Inc., New York, stock no. 1424d, July 1937–38 [4];

Purchased from Wildenstein by The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1938.

Notes

[1] Vollard and the Galerie Bernheim-Jeune jointly purchased ten paintings of Mont Sainte-Victoire from Cezanne’s estate in two batches, one on February 12, 1907 and the other on March 11, 1907; see Rebecca A. Rabinow, ed., Cézanne to Picasso: Ambroise Vollard, Patron of the Avant-Garde, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2006), 345. Jayne Warman confirmed that the Nelson-Atkins version was part of the second batch; see email from Jayne Warman, independent art historian, to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, April 3, 2020, NAMA curatorial files. A Vollard label preserved on the stretcher says “4477.”

[2] Vollard may have purchased Bernheim-Jeune’s ownership share between 1907 and 1936. According to Lionello Venturi, the painting belonged to the “Collection Ambroise Vollard, Paris” by 1936. See Lionello Venturi, Cézanne: Son art, son œuvre (Paris: Paul Rosenberg, 1936), 1:235.

[3] Probably Carl Montag (1880–1956), a dealer in Lausanne, Switzerland.

[4] For the purchase date of July 1937, see letter from Eliot W. Rowlands, Wildenstein and Co., to Meghan Gray, NAMA, May 12, 2011, NAMA curatorial files. A Wildenstein label preserved on the stretcher says “1424d.”

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves, 1904–05,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.712.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves, 1904–05,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.712.4033.

Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves, 1902–04, oil on canvas, 28 3/4 × 36 3/16 in. (73 × 91.9 cm), Philadelphia Museum of Art, The George W. Elkins Collection, 1936, E1936-1-1.

Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves, 1902–06, oil on canvas, 25 5/8 x 31 7/8 in. (65 x 81 cm), Philadelphia Museum of Art, Gift of Helen Tyson Madeira, 1977, 1977-288-1.

Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves, 1902–06, oil on canvas, 25 5/8 x 31 7/8 in. (65 x 81 cm), private collection.

Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves, 1904–06, oil on canvas, 33 x 25 5/8 in. (83.8 x 65 cm), Henry and Rose Pearlman Foundation, New York (on extended loan to the Princeton University Art Museum).

Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves, 1902–06, oil on canvas, 22 5/16 x 38 1/8 in. (56.6 x 96.8 cm), The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves, 1902–06, oil on canvas, 25 x 32 11/16 in. (63.5 x 83 cm), Kunsthaus Zürich.

Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves, 1904–06, oil on canvas, 21 1/4 x 28 11/16 in. (54 x 73 cm), collection of Viktor and Marianne Langen, Neuss, Germany.

Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves, ca. 1904, oil on canvas, 21 1/4 x 25 3/16 in. (54 x 64 cm), location unknown, cited in Impressionist and Modern Art Evening Sale (London: Christie’s, 2020), 121, as La Montagne Sainte-Victoire vue des Lauves.

Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves, 1904–06, oil on canvas, 23 5/8 x 28 5/16 in. (60 x 72 cm), Kunstmuseum Basel.

Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves, 1904–06, oil on canvas, 23 5/8 x 28 11/16 in. (60 x 73 cm), Pushkin Museum, Moscow.

Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves, 1901–06, graphite and watercolor on yellowish paper, 18 3/4 x 24 in. (47.6 x 59.7 cm) The Morgan Library and Museum, New York.

Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves in Winter, 1901–06, graphite and watercolor on wove paper, 12 3/16 x 18 3/4 in. (31 x 47.6 cm), Henry and Rose Pearlman Foundation, New York (on extended loan to the Princeton University Art Museum).

Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves, 1901–06, graphite and watercolor on paper, 17 x 21 in. (41.2 x 52 cm), location unknown, cited in John Rewald, Paul Cezanne: The Watercolours; A Catalogue Raisonné (London: Thames and Hudson, 1983), no. 582, p. 236.

Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves, 1901–06, graphite and watercolor on paper, 11 3/4 x 19 in. (29.9 x 46.3 cm), Musée Granet, Aix-en-Provence.

Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves, 1901–06, graphite and watercolor on paper, 18 11/16 x 24 3/16 in. (47.5 x 61.5 cm), National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin.

Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves, 1901–06, graphite and watercolor on paper, 18 7/8 x 24 13/16 in. (48 x 63 cm), private collection, Munich.

Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves, ca. 1902, graphite and watercolor on paper, 12 3/16 x 19 in. (31 x 47 cm), private collection, Paris.

Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves, 1902–06, graphite and watercolor on paper, 14 3/16 x 21 5/8 in. (36 x 55 cm), Tate Gallery, London.

Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves, 1902–06, graphite and watercolor on wove paper, 19 x 12 3/8 in. (47 x 31.4 cm), Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves, 1902–06, graphite and watercolor on paper, 12 3/8 x 18 15/16 in. (31.5 x 48.1 cm), collection of the Esther Grether family, Basel.

Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves, 1902–06, graphite and watercolor on paper, 12 3/16 x 18 in. (31 x 43.8 cm), private collection.

Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves, 1902–06, graphite and watercolor on paper, 16 15/16 x 23 5/8 in. (43 x 60 cm), private collection, Paris.

Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves, 1902–06, graphite and watercolor on paper, 17 x 21 in. (41.9 x 52 cm), location unknown, cited in Impressionist/Modern Evening Sale (London: Christie’s, 2014), 109.

Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves, 1902–06, graphite and watercolor on paper, 18 11/16 x 22 in. (47.5 x 53.5 cm), location unknown, cited in Christopher Lloyd, Paul Cézanne: Drawings and Watercolors (London: Thames and Hudson, 2015), 232.

Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves, 1902–06, graphite and watercolor on paper, with vertical trace at center right where a second sheet was glued on, 13 x 28 3/8 in. (33 x 72 cm), private collection.

Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves, 1902–06, graphite and watercolor on paper, 16 3/4 x 21 3/8 in. (42.5 x 54.3 cm), The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves, 1902–06, graphite and watercolor on paper, 18 7/8 x 24 7/8 in. (48 x 63.2 cm), Sammlung Oskar Reinhart “Am Römerholz,” Winterthur.

Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from around Saint-Marc, ca. 1906, graphite and watercolor on wove paper, 16 5/8 x 22 in. (42.3 x 54.6 cm), Musée Granet, Aix-en-Provence.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves, 1904–05,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.712.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves, 1904–05,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.712.4033.

Five Years of Collecting, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, December 4–11, 1938, no cat.

Landscapes of the European War Theatre, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, January 1–February 15, 1944, no cat.

Paintings by Paul Cézanne, Cincinnati Art Museum, February 5–March 9, 1947, no. 13, as Montagne Sainte-Victoire.

A Loan Exhibition of Cézanne for the Benefit of the New York Infirmary, Wildenstein, New York, March 27–April 26, 1947, no. 67, as La Montagne Sainte-Victoire.

Masterpieces of 19th Century Painting and Sculpture, Seattle Art Museum, March 7–May 6, 1951, no cat.

Cézanne, Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, RI, September 23–October 20, 1954, no. 20, as Mte. Ste.-Victoire.

Loan Exhibition: Cézanne; Under the Patronage of Mrs. Dwight D. Eisenhower and His Excellency, Monsieur Hervé Alphand, The Ambassador of France to the United States, for the Benefit of The National Organization of Mentally Ill Children, Wildenstein, New York, November 5–December 5, 1959, no. 55, as La Montagne Sainte-Victoire.

Seven Decades, 1895–1965: Crosscurrents in Modern Art, Paul Rosenberg and Co., New York, April 26–May 21, 1966, no. 38, as Mont Sainte Victoire.

Gordian Knot: Design and Content; Biennial Beaux Arts Exhibition, Columbus Gallery of Fine Arts, Ohio, April 7–30, 1967, unnumbered.

Cézanne: The Late Work, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, October 7, 1977–January 3, 1978; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, January 26–March 19, 1978; Galeries nationales du Grand Palais, Paris, April 20–July 23, 1978, no. 61, as Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves [Le Mont Sainte-Victoire vu des Lauves] (New York only).

Cézanne, Musée Saint-Georges, Liège, Belgium, March 12–May 9, 1982; Musée Granet, Aix-en-Provence, June 12–August 31, 1982, no. 26, as La Montagne Sainte-Victoire.

Impressionism: Selections from Five American Museums, The Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, November 4–December 31, 1989; The Minneapolis Institute of Arts, January 27–March 25, 1990; The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, April 21–June 17, 1990; The Saint Louis Art Museum, July 14–September 9, 1990; The Toledo Museum of Art, September 30–November 25, 1990, no. 14, as Mont Sainte-Victoire.

Cézanne Paintings, Kunsthalle Tübingen, Germany, January 16–May 2, 1993, no. 90, as Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves and La montagne Sainte-Victoire vue des Lauves.

Cézanne, Galeries nationales du Grand Palais, Paris, September 26, 1995–January 14, 1996; Tate Gallery, London, February 8–April 28, 1996; Philadelphia Museum of Art, May 26–September 1, 1996, no. 202, as La Montagne Sainte-Victoire vue des Lauves.

Cézanne: Finished, Unfinished, Kunstforum Wien, January 20–April 25, 2000; Kunsthaus Zürich, May 5–July 30, 2000, no. 131, as Mont Sainte-Victoire seen from Les Lauves.

L’Oro e l’Azzurro: I colori del Sud da Cézanne a Bonnard, Casa dei Carraresi, Treviso, Italy, October 10, 2003–March 7, 2004, no. 92, as La montagna Sainte-Victoire.

Inspiring Impressionism: The Impressionists and the Art of the Past, High Museum of Art, Atlanta, October 16, 2007–January 13, 2008; Denver Art Museum, February 23–May 25, 2008; Seattle Art Museum, June 19–September 21, 2008, no. 19, as Mont Sainte-Victoire (Seattle only).

Cézanne and Beyond, Philadelphia Museum of Art, February 26–May 17, 2009, unnumbered, as Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves, 1904–05,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.712.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves, 1904–05,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.712.4033.

Lionello Venturi, Cézanne: Son art, son œuvre (Paris: Paul Rosenberg, 1936), no. 800, pp. 1:64, 235, 403; 2:(repro.), as La Montagne Sainte-Victoire.

John Rewald, “A propos du catalogue raisonné de l’œuvre de Paul Cézanne et de la chronologie de cette œuvre,” La Renaissance 20, nos. 3–4 (March–April 1937): 55.

“Masterpiece of the Month” and “Wednesday Evening Lectures,” News Flashes (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) 4, no. 5 (March 1, 1938): 2–3, as La Montagne Sainte-Victoire.

Paul Gardner, “New Prize in Cezanne Landscape Acquired by the Nelson Gallery: ‘La Montagne Sainte-Victoire’ is Exhibited as the Masterpiece for the Month,” Kansas City Star 58, no. 169 (March 5, 1938): D, as La Montagne Sainte-Victoire.

“Cezanne Landscape Year’s First Purchase at Nelson Art Gallery,” Kansas City Journal-Post 84, no. 165 (March 6, 1938): 8–B, (repro.), as La Montagne Sainte-Victoire.

“Introducing Cezanne,” Kansas City Star 58, no. 171 (March 7, 1938): D, as Montagne Sainte Victoire.

“Nelson Gallery Gets a Cezanne,” New York Times 87, no. 29,262 (March 7, 1938): 14, as Mount Saint Victoire.

Robert J. Goldwater, “Cezanne in America: The Master’s Paintings in American Collections,” Art News 36, no. 26 (March 26, 1938): 151, 156, 158, (repro.), as La Montagne Sainte-Victoire.

“Masterpiece of the Month,” News Flashes (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) 4, no. 6 (April 1, 1938): 2, as Landscape.

“Exhibit of Public School Art Shows Better Teaching Methods,” Kansas City Star 58, no. 203 (April 8, 1938): 17, as Montagne Sainte-Victoire.

H. C. H., “Gallery Gift in Debut: Prized Altarpiece is Added to the Permanent Collection,” Kansas City Star 58, no. 205 (April 10, 1938): 14A.

“Museum Directors Have to Play Detective Now and Then,” Kansas City Star 58, no. 210 (April 15, 1938): 14, as Ste. Victoire.

“Gallery Changes,” News Flashes (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) 4, no. 7 (May 1, 1938): 3, as Montagne St. Victoire.

“Important Gauguin Goes to Missouri Museum,” Art Digest 13, no. 3 (November 1, 1938): 13, as Mont Ste. Victorie [sic].

“‘Visit Your Gallery Week’ Designated December 4–11,” Kansas City Journal 85, no. 66 (November 27, 1938): 36, as Monte Sainte Victoire.

“Five Years of Collecting,” News Flashes (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) 5, no. 2 (December 1, 1938): 1, as Monte Sainte Victoire.

“Footnotes,” Evening State Journal (Lincoln) (December 2, 1938): 8.

Paul Gardner, “Kansas City: Jubilee and an Acquisition,” Art News 37, no. 10 (December 3, 1938): 19, as Mont Ste. Victorie [sic].

“A Good Start on Art: Paintings of Nelson Gallery Are Described by Advisor,” Kansas City Times 101, no. 299 (December 15, 1938): 6.

H. C. H., “Sale of Hearst’s Collection Heads the Art News for 1938,” Kansas City Star 59, no. 104 (December 30, 1938): 6, as Montagne Sainte-Victoire.

Fritz Novotny, Cézanne und das Ende der wissenschaftlichen Perspektive (Vienna: Anton Schroll, 1938), 11, 204, 209.

“A Boast Comes True: Cézanne’s Insistence on His Merit Borne Out by Time,” Kansas City Star 59, no. 142 (February 6, 1939): D, as Montagne Ste. Victoire.

“Collector’s Progress,” Kansas City Times 103, no. 3 (January 3, 1940): C.

“Museums, Art Associations, Other Organizations,” American Art Annual 35 (1941): 268, as Monte Saint Victoire.

The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, The William Rockhill Nelson Collection, 2nd ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1941), 41, 54, 168, (repro.), as La Montaigne [sic] Sainte-Victoire.

“Masterpiece Room,” Gallery News (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) 8, no. 6 (March 1942): 4, as Montagne de Sainte Victoire.

“Nelson Gallery Celebrates First Decade,” Art Digest 18, no. 6 (December 15, 1943): 7, (repro.), as La Montagne Sainte-Victoire.

Ethlyne Jackson, “Museum Record: Kansas City’s Tenth Birthday,” Art News 42, no. 15, (December 15–31, 1943): 16, as Montagne Sainte-Victoire.

Erle Loran, Cézanne’s Composition: Analysis of His Form with Diagrams and Photographs of His Motifs, 3rd ed. (1943; Berkeley: University of California Press, 1963), 11, 105.

“Temporary Exhibitions: Landscapes of the European War Theatre,” Gallery News (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) vol. 10, no. 5 (January 1944): 2, as Monte Sainte Victoire.

“Loan to Other Museums,” Gallery News (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) 13, no. 7 (April 1947), as Mont St. Victoire.

A Loan Exhibition of Cézanne for the Benefit of the New York Infirmary, exh. cat. (New York: Wildenstein, 1947), 65, 67, (repro.), as La Montagne Sainte-Victoire.

Paintings by Paul Cézanne, exh. cat. (Cincinnati: Cincinnati Art Museum, 1947), (repro.), as Montagne Sainte-Victoire.

The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, The William Rockhill Nelson Collection, 3rd ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1949), 68–69, (repro), as La Montagne Sainte-Victoire.

Liliane Guerry, Cézanne et l’expression de l’espace (Paris: Flammarion, 1950), 194n47.

Cézanne, exh. cat. ([Providence]: Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, 1954), unpaginated, as Mte. Ste.-Victoire.

Kurt Badt, The Art of Cézanne, trans. Sheila Ann Ogilvie (1956; repr., Berkeley: University of California Press, 1965), 163, 310.

Ross E. Taggart, “Kansas City Art,” Library Journal 82, no. 12 (June 15, 1957): 1596.

Loan Exhibition: Cézanne; Under the Patronage of Mrs. Dwight D. Eisenhower and His Excellency, Monsieur Hervé Alphand, The Ambassador of France to the United States, for the Benefit of The National Organization of Mentally Ill Children, exh. cat. (New York: Wildenstein, 1959), (repro.), as La Montagne Sainte-Victoire.

John Canaday, “Art: 87 Cezanne Works; Benefit Exhibition at Wildenstein’s Will Be Open Until Dec. 5,” New York Times 109, no. 37,174 (November 4, 1959): 70.

Ross E. Taggart, ed., Handbook of the Collections in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 4th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1959), 123, 260, (repro.), as La Montagne Sainte-Victoire.

Theodore Reff, “A New Exhibition of Cézanne,” Burlington Magazine 102, no. 684 (March 1960): 114, 117, as Montagne Sainte-Victoire.

Maurice Grosser, “Art,” The Nation 191 (July 9, 1960): 38, as Mont Sainte-Victoire [repr., Maurice Grosser, Critic’s Eye (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1962), 180, as Mte. Ste. Victoire].

Robert K. Sanford, “Two Books—Photos and Criticism,” Kansas City Star 82, no. 273 (June 17, 1962): 10E, as Mte. Ste. Victoire.

Henry C. Haskell, “Scanning the Arts,” Kansas City Star 86, no. 65 (November 21, 1965): [1]D.

Peter Selz, Seven Decades, 1895-1965: Crosscurrents in Modern Art, exh. cat. (New York: Public Education Association, 1966), 34, (repro.), as Mont Sainte Victoire.

Mahonri Young, Gordian Knot: Design and Content; Biennial Beaux Arts Exhibition, exh. cat. (Columbus: Anchor Press, 1967), (repro.), as La Montagne Sainte-Victoire.

Sandra Orienti, L’opera completa di Cézanne (Milan: Rizzoli, 1970), no. 762, pp. 120–21, 125, 127–28, (repro.), as Prato e alberi.

Marcel Brion, Paul Cézanne (Milan: Fratelli Fabbri Editori, 1972), 81, (repro.), as La montagna Sainte-Victoire.

Sandra Orienti, The Complete Paintings of Cézanne (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1972), no. 762, pp. 120–21, 125–26, 128, (repro.), as Meadows and Trees.

Judith Wechsler, The Interpretation of Cézanne (1972; repr., Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1981), 50, as Mt. Saint Victoire.

Lilli Fischel, “Von der Bildform der Französischen Impressionisten,” Jahrbuch der Berliner Museum 15 (1973): 82, (repro.), as Landschaft mit Mont Ste Victoire.

Ross E. Taggart and George L. McKenna, eds., Handbook of the Collections in The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Kansas City, Missouri, vol. 1, Art of the Occident, 5th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1973), 150, 165, 257, (repro.), as La Montagne Sainte-Victoire.

Sandra Orienti, Tout l’œuvre peint de Cézanne (Paris: Flammarion, 1975), no. 762, pp. 120–21, 125–27, (repro.), as La Montagne Sainte-Victoire.

Judith Wechsler, ed., Cézanne in Perspective (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1975), (repro.), as Montagne Saint-Victoire.

A[nna] Barskaya, Paul Cézanne (Leningrad: Aurora Art, 1976), 190, 198, (repro.), as Mont Saint-Victoire.

William Rubin, ed., Cézanne: The Late Work, exh. cat. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1977), 27, 67, 95, 205, 313, 405, (repro.), as Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves [Le Mont Sainte-Victoire vu des Lauves].

John Russell, “A Mighty Exhibit of Late Cézannes,” New York Times 127, no. 43,744 (October 30, 1977): 105, as Mont Sainte-Victoire.

Robert H. Terte, “The Phenomenal Nelson Gallery,” Antiques World 1, no. 3 (January 1979): 46.

Richard Shone, The Post-Impressionists (London: Octopus Books, 1979), 108, 110, 112, 114, 175, (repro.), as Mt Ste Victoire seen from Les Lauves and La Montagne Ste Victoire.

Götz Adriani, Cézanne Watercolors, exh. cat., trans. Russell M. Stockman (1981; repr., New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1983), 278.

Marianne R. Bourges, Itinéraires de Cézanne ([Aix-en-Provence]: Ville d’Aix-en-Provence, 1982), (repro.), as La Montagne Sainte-Victoire.

Cézanne, exh. cat. ([Brussels]: Crédit communal de Belgique, 1982), 104–05, (repro.), as La Montagne Sainte-Victoire.

Cézanne ou la peinture en jeu (Limoges: Criterion, 1982), 18, 96, 103–04, 131, 276, 279, (repro.), as La montagne Sainte Victoire.

Bill Marvel, “How Good is the Nelson?” STAR Magazine, supplement, Kansas City Star 103, no. 186 (April 24, 1983): S26, as Le Montagne St. Victoire.

Anna Barskaya, Paul Cézanne: Paintings from the Museums of the Soviet Union; The Hermitage, Leningrad, The Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow, trans. Natalia Johnstone (1983; repr., Leningrad: Aurora Art Publishers, 1985), 148, (repro.), as Mont Sainte-Victoire.

Cézanne au Musée d’Aix, exh. cat. (Aix-en-Provence: Musée Granet, 1984), 55, 101, as La Sainte-Victoire.

Raymond Jean, Cézanne, la vie, l’espace (Paris: Seuil, 1986), 277.

Gene A. Mittler, Art in Focus, 4th ed. (1986; repr., New York: Glencoe McGraw-Hill, 2000), 496, (repro.), as Mont Sainte-Victoire.

John Rewald, Cézanne: A Biography (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1986), 248, 278, (repro.), as Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves.

Lorenz Eitner, An Outline of 19th Century European Painting: From David Through Cézanne (New York: Harper and Row, 1987–1988), 1:437; 2:xv, 237, (repro.), as Mont Sainte-Victoire.

Ellen R. Goheen, The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1988), 106–07, (repro.), as Montagne Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves.

Jean-Jacques Lévêque, La vie et l’œuvre de Paul Cézanne (Courbevoie, France: ACR Édition Internationale, 1988), 208, 238, (repro.), as La Montagne Sainte-Victoire.

Benjamin Martinez and Jacqueline Block, Visual Forces: An Introduction to Design, 2nd ed. (1988; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1995), 196–97, (repro.), as La Montegne [sic] Sainte-Victoire.

Jacques Teboul, Les Victoires de Cézanne (Paris: Éditions Adam Biro, 1988), 50, 115, (repro.), as La Montagne Sainte-Victoire.

Marc S. Gerstein, Impressionism: Selections from Five American Museums, exh. cat. (New York: Hudson Hills, 1989), 50–51, (repro.), as Mont Sainte-Victoire.

Lionello Venturi, Cézanne: Son art, son œuvre (San Francisco: Alan Wofsy Fine Arts, 1989), no. 800. pp. 1:64, 235, 403; 2:(repro.), as La Montagne Sainte-Victoire.

Scott Cantrell, “Keepers of the Light,” Kansas City Star 110, no. 191 (April 22, 1990): M-1.

Toni Wood, “Expatriate Paintings in Midwest,” Kansas City Star 110, no. 233 (June 3, 1990): G-5, as Mont Sainte-Victoire.

Sainte-Victoire: Cézanne 1990, exh. cat. (Paris: Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 1990), 288–89, 353, 355, (repro.), as La Montagne Sainte-Victoire.

Manfred Koch-Hillebrecht, Museen in den USA: Gemälde (Munich: Hirmer Verlag, 1992), 244, as Mont Sainte-Victoire.

Eric de Chassey, “Les quatre leçons de Cézanne,” Beaux Arts, no. 111 (April 1993): 83, (repro.), as la Montagne Sainte-Victoire.

Robert Morris, “Writing with Davidson: Some Afterthoughts after Doing Blind Time IV: Drawing with Davidson,” Critical Inquiry 19, no. 4 (Summer 1993): 626, as Mont Saint Vistoire [sic] seen from Les Lauves, France.

Alice Thorson, “The Nelson Celebrates its 60th: Museum built its reputation, collection virtually ‘from scratch’,” Kansas City Star 113, no. 304 (July 18, 1993): J4.

Götz Adriani, Cézanne: Paintings, exh. cat., trans. Russell Stockman (1993; repr., Cologne: Dumont Buchverlag, 1995), 39, 124, 260, 262–66, 268, as Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves and La montagne Sainte-Victoire vue des Lauves.

Richard Verdi, “Cézanne: Tübingen,” Burlington Magazine 135, no. 1081 (April 1993): 296.

Cézanne: Gemälde; Meisterwerke aus vier Jahrzehnten ([Tübingen, Germany: Kunsthalle Tübingen, 1993]), (repro.), as Das Gebirgmassiv Sainte-Victoire, Mont Sainte-Victoire, Das Gebirgmassiv Sainte-Victoire von Les Lauves aus gesehen, and Mount Saint-Victoire as Seen from the Chemin des Lauves.

Bernard Denvir, The Chronicle of Impressionism: An Intimate Diary of the Lives and World of the Great Artists (London: Thames and Hudson, 1993), 279, as Mont Ste-Victoire.

Roger Ward and Patricia J. Fidler, eds., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collection (New York: Hudson Hills Press, in association with Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1993), 214, (repro.), as Mont Sainte-Victoire.

Jed Jackson, Art: A Comparative Study (Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt, 1994), 155-56, (repro.), as Montagne Sainte-Victoire seen from Les Lauvres [sic] and Mont Sainte-Victoire (Seen from Les Lauvres [sic]).

Alain Madeleine-Perdrillat, “Cézanne,” Le Journal des Arts, no. 1 (1995): 3–5, 19, (repro.), as La Montagne Sainte-Victoire Vue des Lauves.

Ulrike Becks-Malorny, Paul Cézanne 1836–1906: Pioneer of Modernism (Cologne: Benedikt Taschen Verlag, 1995), 73–74, (repro.), as La montagne Sainte-Victoire.

Françoise Cachin and Joseph J. Rishel, Cézanne, exh. cat. (1995; repr., New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1996), 259, 264, 266, 421, 466, 469, 473–74, 597, 599, (repro.), as Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves.

Evmarie Schmitt, Cézanne in Provence, trans. John William Gabriel (Munich: Prestel, 1995), 90, 92–93, 116, (repro.), as Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves.

Wei-kwang Wang, The Art of Chen Te-wang (Taipei, Taiwan: Artist Publishing, 1995), 140, (repro.), as Mont Sainte-Victoire.

Mary Louise Krumrine, “Paris and London: Cézanne,” Burlington Magazine 138, no. 1117 (April 1996): 266, as La Montagne Sainte-Victoire vue des Lauves.

Richard Shone, “London: Cézanne,” Burlington Magazine 138, no. 1118 (May 1996): 342, as Mont Sainte-Victoire.

Lisa N. Peters, A Personal Gathering: Paintings and Sculpture from the Collection of William I. Koch, exh. cat. (Wichita, KS: Wichita Art Museum, 1996), 74, (repro.), as Mont Sainte-Victoire.

John Rewald, The Paintings of Paul Cézanne: A Catalogue Raisonné (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1996), no. 913, pp. 1: 18, 479, 536, 539–40, 561, 570–74, 577, 579–80; 2: 320, (repro.), as Le Mont Sainte-Victoire Vu des Lauves.

Yves Letournel, “Recherches de facture chez Rimbaud et Cézanne,” Parade sauvage: revue d’études rimbaldiennes, no. 14 (May 1997): 111, 131, as Sainte-Victoire.

Françoise Cachin, Henri Loyrette, and Stéphane Guégan, eds., Cézanne aujourd’hui: Actes du colloque organisé par le musée d’Orsay, 29 et 30 novembre 1995 (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 1997), 101, 121, (repro.), as La Montagne Sainte-Victoire vue des Lauves.

Richard McDaniel, Landscape: A Comprehensive Guide to Drawing and Painting Nature (New York: Watson-Guptill, 1997), 17, (repro.), as Mont Sainte-Victoire.

Robert Morris, “Cézanne’s Mountains,” Critical Inquiry 24, no. 3 (Spring 1998): 823, as Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves.

Marilyn and Raymond Zolton, Artists in Light: A Biographical Guide to Southern France (Bethlehem, NH: Raymar Associates, 1998), 12.

Boris von Brauchitsch, Das 20. Jahrhundert: Meisterwerke Jahr für Jahr (Cologne: DuMont Buchverlag, 1999), 16–17, (repro.), as Der Berg Sainte-Victoire, von Les Lauves aus gesehen.

John C. Gilmour, “Improvisation in Cézanne’s Late Landscapes,” Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 58, no. 2 (Spring 2000): 199–200, 202, as Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves.

Felix Baumann et al., eds., Cézanne: Finished, Unfinished, exh. cat. (Ostfildern, Germany: Hatje Cantz, 2000), 56–58, 328, 358–59, 361, 406–07, (repro.), as Mont Sainte-Victoire seen from Les Lauves.

Nils Büttner, Landscape Painting: A History, trans. Russell Stockman (2000; repr., New York: Abbeville Press, 2006), 16–17, 320, 323, 357, 386, 406, (repro.), as Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves.

Hidemichi Tanaka, “Cézanne and Japonisme,” Artibus et Historiae 22, no. 44 (2001): 219n43.

Michael Doran, ed., Conversations with Cézanne, trans. Julie Lawrence Cochran (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001), 206–07.

Maria Teresa Benedetti, Cézanne: Il padre dei moderni (Milan: Mazzotta, 2002), 30 74, 74n54, (repro.), as La Sainte-Victoire vista dai Lauves.

Amano Shige, 美術論 [Art Theory] (Osaka: Osaka University of Arts, Department of Distance Learning, 2002), 134–35, (repro.), as サント・ヴィクトワール山 [Mont Sainte-Victoire].

Atelier Cézanne, 1902–2002: Le Centenaire ([Aix-en-Provence]: Société Paul Cézanne, [2003]), 61, as Sainte-Victoire.

Marco Goldin, L’Oro e l’Azzurro: I colori del Sud da Cézanne a Bonnard, exh. cat. (Conegliano, Italy: Linea d’ombra Libri, 2003), 277, 357–58, (repro.), as La montagna Sainte-Victoire.

Felix A. Baumann, Walter Feilchenfeldt, and Hubertus Gassner, eds., Cezanne and the Dawn of Modern Art, exh. cat. (Ostfildern-Ruit, Germany: Hatje Cantz, 2004), 130–31, (repro.), as Montagne Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves.

Contemporary Art / Evening (New York: Sotheby’s, 2004), 116–17, (repro.), as Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves.

Giuseppe Frangi, Cézanne estremo, 1899–1906: opere, lettere, testimonianze (Bari: Edizioni di Pagina, 2004), 62–63, (repro.), as La montagna Sainte-Victoire vista da Les Lauves.

Michael Humphrey, “Compulsion to Paint,” STAR Magazine, supplement, Kansas City Star 127, no. 91 (December 17, 2006): S30.

Götz Adriani, Paul Cézanne: Leben und Werk (Munich: Verlag C.H. Beck, 2006), 43–48, 72, (repro.), as Das Gebirgsmassiv Sainte-Victoire von Les Lauves aus gesehen.

Jean Arrouye, ed., Cézanne, d’un siècle à l’autre (Marseille: Éditions Parenthèses, 2006), 178.

Philip Conisbee and Denis Coutagne, Cézanne in Provence, exh. cat. (Washington: National Gallery of Art, 2006), 284, 286–87, 342n24, (repro.), as Montagne Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves.

Denis Coutagne, Cézanne en vérité(s): “Je vous dois la vérité en peinture et je vous la dirai” (Arles: Actes Sud, 2006), 476, 480–84, 487–90, 494–95, 512n179, 588, (repro.), as Montagne Sainte-Victoire vue des Lauves.

Rebecca A. Rabinow, ed., Cézanne to Picasso: Ambroise Vollard, Patron of the Avant-Garde, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2006), 345.

Roberta Bernabei, Cézanne (2007; repr., Munich: Prestel, 2013), 130–31, 155, (repro.), as Mont Sainte-Victoire (Seen from Lauves).

Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 16–17, (repro.), as Mont Sainte-Victoire.

Ann Dumas, ed., Inspiring Impressionism: The Impressionists and the Art of the Past, exh. cat. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007), 175, 178, 258, (repro.), as Mont Sainte-Victoire.

Ce que Cézanne donne à penser: Actes du colloque d’Aix-en-Provence, 5, 6 et 7 juillet 2006 (Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 2008), 184.

Pavel Machotka, Cézanne: La sensation à l’œuvre; The eye and the mind (Marseille: Éditions Crès, 2008), 1:(repro.); 2:222, (repro.), as La Montagne Sainte-Victoire Vue des Lauves.

Deborah Emont Scott, ed., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collection, 7th ed. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2008), 35, 128, (repro.), as Mont Sainte-Victoire.

Hans-Günther Van Look, Sehrevolte der Scheinung: Cézanne am Mont Sainte-Victoire (Munich: Karl Alber, 2008), 111, (repro.), as La Montagne Sainte-Victoire.

Joseph J. Rishel and Katherine Sachs, Cézanne and Beyond, exh. cat. (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2009), 57, 433, 443–44, 465, 480, 534, (repro.), as Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves.

Françoise Barbe-Gall, How to Look at Impressionism, trans. Emily Read (2010; repr., London: Francis Lincoln, 2013), 240–46, (repro.), as Mont Sainte-Victoire.

Rudy Chiappini, Cézanne: Les ateliers du Midi, exh. cat. (Milan: Skira, 2011), 54, 54n16.

Denis Coutagne, Cézanne abstraction faite (Paris: Cerf, 2011), 178, 178n194.

Robert Morris: el dibujo como pensamiento, exh. cat. (Valencia: Institut Valenciá d’Art Modern, 2011), 17–18, 28, 55, 64, 271, 297, 300, 308, 311, 326, 333, 337, 345, 348, 350, (repro.), as Mont Sainte-Victoire.

Alex Danchev, Cézanne: A Life (New York: Pantheon Books, 2012), 342, 441n47.

Alice Thorson, “His mythic, intense, cosmic art,” Kansas City Star 135, no. 81 (December 7, 2014): D8.

Impressionist/Modern Evening Sale (London: Christie’s, June 24, 2014), 111.

“Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art celebrates generosity of Henry Bloch with new acquisition,” Artdaily.org (October 18, 2016): https://artdaily.cc/news/90923/Nelson-Atkins-Museum-of-Art-celebrates-generosity-of-Henry-Bloch-with-new-acquisition#.XnKATqhKiUk, as Mont Saint Victoire.

Catherine Futter et al., Bloch Galleries: Highlights from the Collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2016), 104, (repro.), as Mont Sainte-Victoire.

Toni Hildebrandt, Entwurf und Entgrenzung: Kontradispositive der Zeichnung 1955–1975 (Paderborn, Germany: Wilhelm Fink, 2017), 132, 167, 169–71, 175, 360, (repro.), as Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen From Les Lauves and La Montagne Sainte-Victoire, von Les Lauves aus gesehen.

Daniel Marchesseau, Paul Cezanne: Le chant de la terre, exh. cat. (Martigny: Fondation Pierre Gianadda, 2017), 220.

Carol Armstrong, Cézanne’s Gravity (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018), 165, 167, 169, (repro.), as Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves.

Elisabeth Oy-Marra et al., eds., Intermedialität von Bild und Musik (Paderborn, Germany: Wilhelm Fink, 2018), 343.

Lærde Rydal Jørgensen and Mathias Ussing Seeberg, eds., Marsden Hartley: The Earth is All I Know of Wonder, exh. cat. (Humlebæk, Denmark: Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, 2019), 69–70, (repro.), as Mont Sainte-Victoire.

Walter Feilchenfeldt, Jayne Warman, and David Nash, “La Montagne Sainte-Victoire vue des Lauves, 1902–1906 (FWN 353),” The Paintings, Watercolors and Drawings of Paul Cezanne: An Online Catalogue Raisonné, https://www.cezannecatalogue.com/catalogue/entry.php?id=887 (last updated on April 3, 2020, accessed on April 8, 2020).

Christel H. Force, ed., Pioneers of the Global Art Market: Paris-Based Dealer Networks, 1850–1950 (London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2020), 59–61.

Impressionist and Modern Art Evening Sale (London: Christie’s, February 5, 2020), 123.