Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Simon Kelly, “Théodore Rousseau, The Eagle’s Nest, Forest of Fontainebleau, ca. 1837–67,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.532.5407.

MLA:

Kelly, Simon. “Théodore Rousseau, The Eagle’s Nest, Forest of Fontainebleau, ca. 1837–67,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.532.5407.

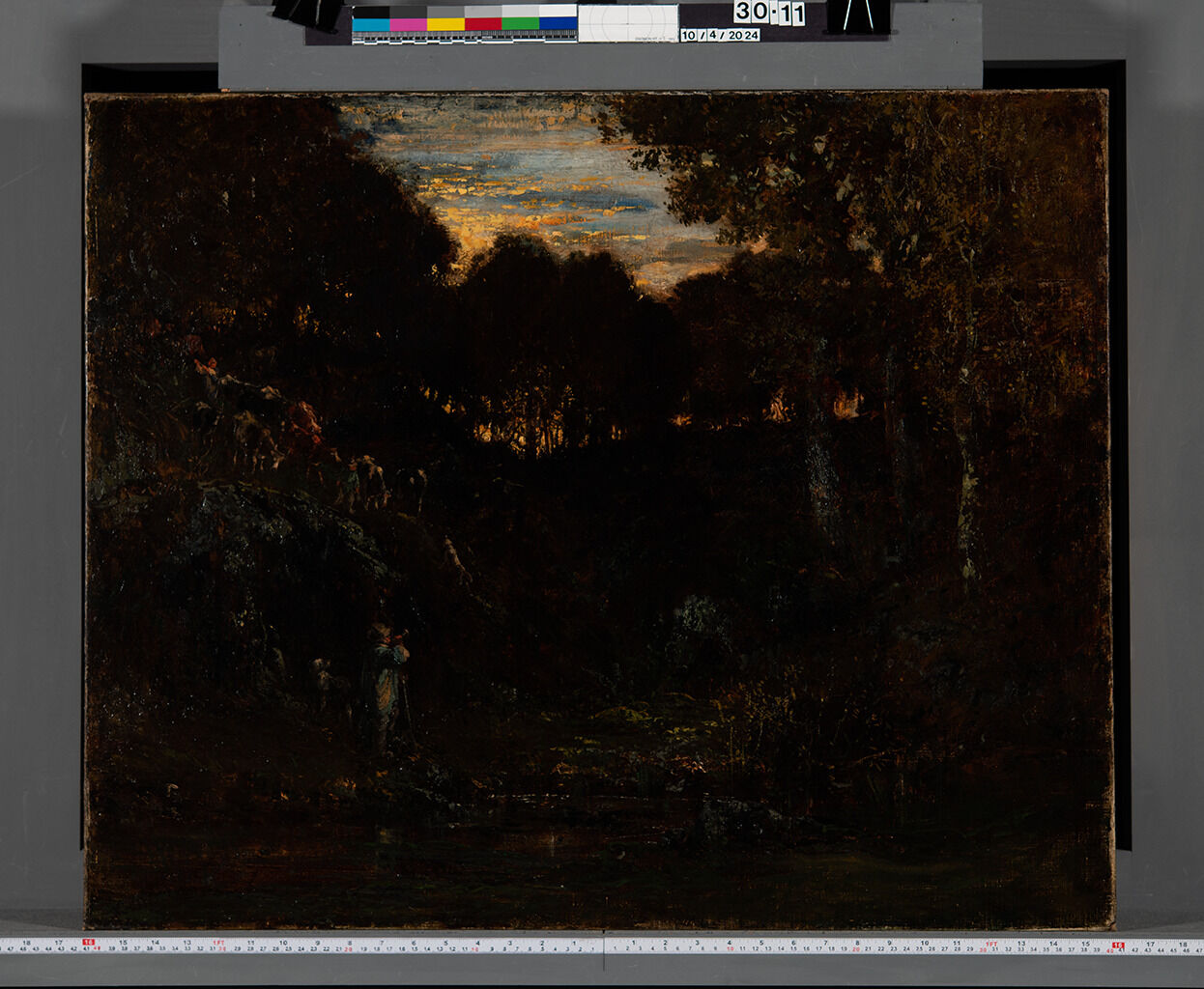

This picture was until recently titled Cows Descending the Hills at Sunset, but the discovery of the location represented—namely the site of The Eagle’s Nest valley in the Forest of Fontainebleau—provides not only a new title but also a more precise meaning for the work.1Thanks to Nicole R. Myers, Meghan L. Gray, and Danielle Hampton Cullen for their assistance in providing this new identification based on an annotation on the final state of the Théophile-Narcisse Chauvel etching (Bibliothèque Nationale de France) after Rousseau’s picture. The annotation reads “LE NID DE L’AIGLE / Gravé par Th[éophile] Chauvel d’aprés le tableau original de Th[éodore] Rousseau” (The Eagle’s Nest/ Engraved by Th [éophile] Chauvel after the original painting by Th[éodore] Rousseau). All translations by Simon Kelly unless otherwise indicated. For the Nelson-Atkins example of the Chauvel etching, see Fig. 5. This is the only known painting by Théodore Rousseau of this location in that expansive forest, some thirty-five miles southeast of Paris. The site was so named since eagles had made their nests there in the past.2Charles-François Denecourt, Le Palais et la Forêt de Fontainebleau: Guide Historique et Descriptif (Fontainebleau, 1840), 22. It was close by the town of Fontainebleau but some distance from the motifs that Rousseau generally favored on the other side of the forest, near the village of Barbizon where he had a house and studio amid the large artist community that would come to be known as the Barbizon School. In this atmospheric evening scene, a cowherd in a blue smock blows on his horn to encourage the descent of cows toward a pond or watering hole. Two other herders, one wielding a stick, also urge on the cattle, while two dogs assist in the process. Such a pond was unusual across the predominantly dry expanse of the forest and would have been sought out by the herders. Rousseau places his protagonists within a landscape of trees with russet foliage and rocky outcroppings.

The Eagle’s Nest was a site that was deeply affected by the rise of tourism in the forest of Fontainebleau, particularly as a result of the efforts of Claude-François Denecourt, an entrepreneur with a military background who wrote detailed guidebooks to the forest starting in 1839.3Charles-François Denecourt, Camp de Fontainebleau, Sa Position Topographique . . . Cet Opuscule fait Suite au Guide du Voyageur dans la Forêt de Fontainebleau (Fontainebleau: S. Petit, 1839). By the middle of the century, Denecourt ensured that every tree and rock of picturesque interest in this location was lettered for the benefit of tourists, who arrived with guidebook in hand. A prominent old oak, for example, was eponymously named “Nid de l’Aigle” (Eagle’s Nest) and was literally marked in blue with an A, while a notable sandstone rock received the name “Amélie” and was indicated with a P.4Charles-François Denecourt, Le Palais et la Forêt de Fontainebleau: Guide Historique et Descriptif, rev. ed. (Fontainebleau, 1856), 206–7. For this site, see Olivier Blaise, “Le Nid de l’Aigle,” Fontainbleau-Photo, accessed June 13, 2025, https://www.fontainebleau-photo.fr/2018/02/le-nid-de-laigle.html; and “Le Bouquet du Nid de l’Aigle (arbre disparu),” En Foret de Fontainebleau, Hier et Aujourd’hui, accessed June 13, 2025, https://foret-fontainebleau.teria.fr/fiches.html?ref1=418&ref2=15&checkbox=paint,photo,card. The location also was well known as a site for quarrying sandstone, close as it was to Mont Ussy, where quarrying was prevalent in the first half of the nineteenth century.5Denecourt, Palais et la Forêt de Fontainebleau (1856), 207. The extraction of such rock in the forest provided paving stones for the streets of Paris, with up to 2.9 million paving stones mined each year.6This number was delivered in 1829 at the height of stone production. Paul Domet, Histoire de la Forêt de Fontainebleau (Paris: Librarie Hachette et Cie, 1873), 217. See also Kimberly Jones, “Landscapes, Legends, Souvenirs, Fantasies: The Forest of Fontainebleau in the Nineteenth Century,” in In the Forest of Fontainebleau: Painters and Photographers from Corot to Monet, ed. Kimberly Jones, exh. cat. (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2007), 6. Notably, however, Rousseau’s pastoral image screens out all reference to such tourism, and his rocks merge into the overall natural vista rather than appearing as a place of extractive mining. The artist focuses on evoking, in a sensory and visceral way, the diverse textures of rough bark, decaying leaves, jagged rocks, wispy pond plants, and shimmering pond water.

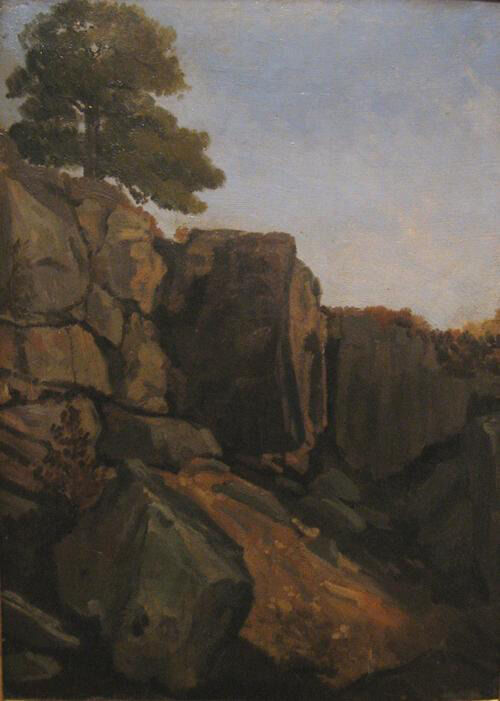

Rousseau first visited the forest of Fontainebleau in the late 1820s and, over the decades, acquired what might be called a deep ecological understanding of it.7For such a reading, see Greg M. Thomas, Art and Ecology in Nineteenth-Century France: The Landscapes of Théodore Rousseau (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000), particularly the discussion of Forest Interior [Old Watering Hole of Bas-Bréau] (1836–37; Musée du Louvre, RF 291, on deposit at Musée d’Orsay) on pp. 165–67. The use of the screen of trees in this image prevents the eye from moving back into the distance and encourages a focus on the various kinds of natural matter on view, as well as the interactions between mossy stone, dense foliage, and nourishing water in this marshy ecosystem. Rousseau’s biographer, Alfred Sensier, related that he spent the fall and winter in the forest from 1837 until 1840 living “like an artist-trapper” and intensely studying forest motifs.8“En artiste-trappeur.” Alfred Sensier, Souvenirs sur Théodore Rousseau (Paris: Léon Techener, 1872), 117. One cannot say that Rousseau ever had a scientifically geological or botanical understanding of the forest; however, he carefully studied its natural forms. Although other artists also represented the Eagle’s Nest—Auguste Anastasi (1820–89) painted an angular rock face that had been mined (Fig. 1), and the printmaker Eugène Bléry (1805–87) made an etching (Fig. 2) that seems to show the same rocks, trees, and pond as Rousseau’s painting does—Rousseau’s anti-academic technique mirrored the materiality of this natural site in a new way.

Fig. 1. Auguste Anastasi, Study of Rocks, Le Nid de l’Aigle, Fontainebleau, late 1840s, oil on panel, 16 1/4 x 11 13/16 in. (41.3 x 30 cm), Musée Départemental des Peintres de Barbizon, MDPB.2006.1.1.

Fig. 1. Auguste Anastasi, Study of Rocks, Le Nid de l’Aigle, Fontainebleau, late 1840s, oil on panel, 16 1/4 x 11 13/16 in. (41.3 x 30 cm), Musée Départemental des Peintres de Barbizon, MDPB.2006.1.1.

Fig. 2. Eugéne Bléry, The Rocks, Le Nid de l’Aigle, Fontainebleau, 1845, etching, 6 3/8 x 8 1/4 in. (16.2 x 20.9 cm), British Museum, London, 1856,0712.294. © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license.

Fig. 2. Eugéne Bléry, The Rocks, Le Nid de l’Aigle, Fontainebleau, 1845, etching, 6 3/8 x 8 1/4 in. (16.2 x 20.9 cm), British Museum, London, 1856,0712.294. © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license.

Despite screening out the quarrying industry, Rousseau did emphasize the Eagle’s Nest as a site of agrarian labor. He highlights the presence of the cowherders and cows, a favorite subject across his career. The pastoral overtones of these elements hark back to Rousseau’s fascination with the poetry of ancient Greece and Rome and the Arcadian herders often depicted in this tradition. However, his cowherders, two of whom wear blue smocks characteristic of Barbizon rural laborers, live very much in the contemporary moment. Rousseau would have been aware of the long-standing practice of communal grazing on forest land. This was permitted all year round and codified numerically at the beginning of the Second EmpireSecond Empire: The regime of Napoléon III in France, which lasted from 1852 to 1870., when an 1853 report on the forest’s future stated that up to 782 cows could graze there. In fact, far fewer grazed in the years that followed.9Thomas, Art and Ecology, 155, 251n19. Paul Domet, an early historian of the forest, noted that the number declined from 1,100 in 1850 to only 297 in 1870, as farmers saw that it was preferable to keep their cattle in the stable, where they could be well nourished, rather than roaming in the forest, where food could be meager and their valuable manure could also not be collected.10Domet, Histoire de la Forêt de Fontainebleau, 209–10. Rousseau’s picture thus recorded a grazing practice that was disappearing by the second half of the century. This context adds a sense of rural nostalgia to the painting.

Recent technical analysis has highlighted Rousseau’s rugged, anti-academic technique. He used a palette knife across much of the canvas surface to evoke the materiality of natural textures.11See Mary Schafer and John Twilley’s accompanying technical entry. His dragged paint suggests the mottled texture of tree bark and evokes the surface of the water. The luminous sunset sky is also rendered with the flattened marks of the palette knife. Gustave Courbet (1819–77) is probably best known for this technique, but Rousseau also used it on occasion, as, for example, in the Charcoal-Burner’s Hut (ca. 1850–51; Musée du Louvre, Paris). Nevertheless, it is unusual in his oeuvre. His experimental approach is also evident here in his scraping away of paintsgraffito (pl: sgraffiti): An Italian term meaning “scratched,” in which a compositional design or decoration is created using a sharp tool to scrape into the wet medium (paint, plaster, glaze, slip, etc) and reveal contrasting underlying layers., probably using the butt end of the brush, as in the areas of foliage to the right.12Schafer and Twilley, technical entry. Technical analysis has indicated that Rousseau revised this picture considerably. Originally the horizon line descended to the right of the composition, offering what would have been a much more open vista on the right of the picture. Rousseau later added the mass of three trees to the right, creating a more closed and claustrophobic composition. The precise timeline for Rousseau’s reworking of this picture remains unclear, but it was not uncommon for him to revise his paintings over a number of years. The picture was probably begun during the late 1830s during Rousseau’s period of intense study in the forest, when he favored a dark palette and rugged impastoimpasto: A thick application of paint, often creating texture such as peaks and ridges. technique. New research from conservator Mary Schafer and science advisor John Twilley indicates that the later paint layer (with the three-tree addition) contains zinc chromate yellow and cadmium yellow, both of which seem to have been only commercially available from the mid-1840s.13Schafer and Twilley, technical entry. The presence of these pigments suggests that Rousseau revised the picture after this latter date, perhaps even as late as the end of his career.14This dating contrasts with the date of 1860–65 in the Rousseau catalogue raisonné: Michel Schulman, Théodore Rousseau, 1812–1867: Catalogue Raisonné de l’Oeuvre Peint (Paris: Éditions de l’Amateur, 1999), no. 642, p. 326. Rousseau’s paint application in this picture, however, is very different from the uniform, “proto-pointillist” brushwork characteristic of his newly produced work of the early 1860s. In fact, he likely sold the picture to the dealers Paul Durand-Ruel (1831–1922) and Hector Brame (1831–99) in the summer of 1867 (see provenance information below).

Rousseau’s subject of cows descending down a ravine suggests that the picture is a horizontal variant on the large-scale The Descent of the Cattle in the High Jura Mountains (Fig. 3), which was a pivotal work in the artist’s early career and the result of protracted study following a visit to the Jura region of eastern France in 1834. Rousseau, indeed, produced both an oil sketch (ca. 1834–35; Mesdag Collection, The Hague) and a full-scale painted study (1834–36; Musée de Picardie, Amiens).15For a recent discussion of the Nelson-Atkins picture within the context of these related works and Rousseau’s interest in bituminous “dark matter,” see Kelly Presutti, Land into Landscape: Art, Environment, and the Making of Modern France (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2024), 126–28. See also Simon Kelly, Théodore Rousseau and the Rise of the Modern Art Market: An Avant-Garde Landscape Painter in Nineteenth-Century France (New York: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2021), 19–23. Rousseau’s painter friend Jules Dupré (1811–89) thought Descent of the Cattle in the High Jura Mountains was as impressive as The Raft of the Medusa (1818–19; Musée du Louvre) by Théodore Géricault (1791–1824).16“Quand Jules Dupré vit la Descente des Vaches . . . elle lui sembla aussi inattendue, aussi prodigieuse que la venue de la terrible Méduse de Géricault” (When Jules Dupré saw the Descent of the Cows . . . it seemed to him as unexpected, as extraordinary as the appearance of the terrible Medusa of Géricault). Sensier, Souvenirs, 79. Rousseau submitted the painting to the Paris SalonSalon, the: Exhibitions organized by the French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture (Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture) and its successor the Academy of Fine Arts (Académie des Beaux Arts), which took place in Paris from 1667 onward. in 1836 and 1838, but it was controversially refused by the conservative Salon jury on both occasions. The artist’s frontal view of the cows, with the vertiginous effect that they almost appear to tumble out of the picture space, was too shocking for these jurors, as was his use of vibrant, gestural impasto.17Rousseau’s rapidly applied paint layers, including emerald green and bituminous materials, subsequently caused the paint surface to darken and crack over time. See René Boitelle, Klaas Jan van den Berg, Muriel Geldof, and Georgiana Languri, “Descending into the Details of Th. Rousseau’s ‘La Descente des Vaches’ (Museum Mesdag, The Hague)—Technical Research of a Darkened Painting,” in “Deterioration of Artists’ Paints”: A Joint Meeting of ICOM-CC Working Groups Paintings 1 and 2 and The Paintings Section, UKIC, London, 10–11 September, 2001, ed. Alan Phenix (London: United Kingdom Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works and International Council of Museums, 2001), 27–31. See also Katrin Keune, Jaap Boon, René Boitelle, and Yoshiko Shimadzu, “Degradation of Emerald Green in Oil Paint and Its Contribution to the Rapid Change in Colour of the Descente des Vaches (1834–35) Painted by Théodore Rousseau,” Studies in Conservation 58, no. 3 (July 2013): 199–210. The Eagle’s Nest, Forest of Fontainebleau indicates that this general subject of descending cowherders remained resonant to Rousseau, although he translated it from the Jura to the forest of Fontainebleau and from a monumentally scaled, vertically oriented picture to a more modestly sized horizontal composition. The pine trees of the Jura were replaced with the oaks, beeches, and birches of Fontainebleau, and the Jura cows and their colorful collars with the undecorated Fontainebleau livestock.

During the late 1830s, Rousseau worked in deep, often tenebrous tones, exploring dark glazes in an attempt to recreate the rich palette of Rembrandt van Rijn (Dutch, 1606–69), an artist who had special meaning for him throughout his career. This was a period of painterly experimentation, as Rousseau explored a variety of techniques that subverted the more polished surfaces favored by academic artists. The nuanced range of tones in the sky of The Eagle’s Nest, Forest of Fontainebleau, from lavender to orange to yellow, is worthy of note. Throughout his career, Rousseau was known for his ability to render a variety of light effects and showed a particular fascination with sunsets. Sensier noted that during the artist’s time in the forest of Fontainebleau, from the late 1830s, he liked to “condense the splendors of the autumnal season and loved to seize these golden sunsets.”18“Il aimait à condenser les splendeurs des températures d’automne, à saisir ces couchers de soleil d’or.” Sensier, Souvenirs, 117. In 1846, Charles Baudelaire described Rousseau’s intoxication with sunsets:

He loves nature in her bluish moments—twilight effects—strange and moisture-laden sunsets—massive, breeze-haunted shades—great plays of light and shadow. His colour is magnificent, but not dazzling. The fleecy softness of his skies is incomparable. Think of certain landscapes by Rubens and Rembrandt; add a few memories of English painting, and assume a deep and serious love of nature dominating and ordering it all—and then perhaps you will be able to form some idea of the magic of his pictures.19“Il aime les natures bleuâtres, les crépuscules, les couchers de soleil singuliers et trempés d’eau, les gros ombrages où circulent les brises, les grands jeux d’ombres et de lumière. Sa couleur est magnifique, mais non pas éclatante. Ses ciels sont incomparables pour leur mollesse floconneuse. Qu’on se rappelle quelques paysages de Rubens et de Rembrandt, qu’on y mêle quelques souvenirs de peinture anglaise, et qu’on suppose, dominant et réglant tout cela, un amour profond et sérieux de la nature, on pourra peut-être se faire une idée de la magie de ses tableaux.” See Charles Baudelaire, “Salon de 1846,” in Art in Paris, 1845–62: Salons and Other Exhibitions Reviewed by Charles Baudelaire, ed. and trans. Jonathan Mayne (London: Phaidon Press, 1965), 108–9.

In the mid-1840s, Rousseau began his large-scale The Forest in Winter at Sunset (Fig. 4), another view of trees silhouetted against the sky, on which he also worked intermittently for decades. The picture shares similar formal methods to Eagle’s Nest, Forest of Fontainebleau: the palette knife for scraping and applying paint, removal of wet paint to reveal underlying colors, and finger blotting.20Schafer and Twilley, technical entry.

Fig. 4. Théodore Rousseau, Forest in Winter at Sunset, ca. 1846–67, oil on canvas, 64 x 102 3/8 in. (162.6 x 260 cm), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Gift of P. A. B. Widener, 1911, 11.4

Fig. 4. Théodore Rousseau, Forest in Winter at Sunset, ca. 1846–67, oil on canvas, 64 x 102 3/8 in. (162.6 x 260 cm), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Gift of P. A. B. Widener, 1911, 11.4

Fig. 5. Théophile-Narcisse Chauvel, after Théodore Rousseau, The Eagle’s Nest in the Forest of Fontainebleau, 1880, etching on buff laid paper, 23 1/8 x 26 in. (58.7 x 66 cm), Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Gift of Findlay Galleries, Kansas City, 2023.12

Fig. 5. Théophile-Narcisse Chauvel, after Théodore Rousseau, The Eagle’s Nest in the Forest of Fontainebleau, 1880, etching on buff laid paper, 23 1/8 x 26 in. (58.7 x 66 cm), Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Gift of Findlay Galleries, Kansas City, 2023.12

The early provenance of The Eagle’s Nest, Forest of Fontainebleau is unclear. It may be the picture listed in the stock books of the dealer Paul Durand-Ruel as Défilé de troupes (Descent of Herds), which was the seventy-eighth picture of a batch of ninety-one that was sold by the artist to Durand-Ruel and Brame in the summer of 1867.21See Durand-Ruel stock book, 1868–73, purchases made fifty-fifty with Hector Brame, no. 10,633, Les Archives Durand-Ruel, Paris. See also the listing in Kelly, Théodore Rousseau and the Rise of the Modern Art Market, appendix 3, p. 232. This picture was given a value of 200 francs in the batch. The dealers then gifted it, in March 1869, to “Mr. Herman,” who was the Parisian violinist, composer, and collector Adolphe Joseph Herman (1822–1903), with the gift made as a gesture of thanks for other purchases that this collector had made.22For more about Herman, see Paul-Louis Durand-Ruel and Flavie Durand-Ruel, eds., Paul Durand-Ruel: Memoirs of the First Impressionist Dealer (Paris: Flammarion, 2014), 40, 112, 250n86. In 1872, Durand-Ruel bought back the picture for 200 francs before selling it at a profit of 500 francs to the chevalier Alfred de Knyff (1819–85), a Belgian collector and painter.23See Durand-Ruel’s purchase of Défilé de troupes dans une forêt (Descent of Herds in a Forest), the title in the 1872 stock book entry, from Herman for 200 francs. It was sold to De Knyff on September 2, 1872, for 500 francs. See Durand-Ruel stock book, 1868–73, no. 1880, Les Archives Durand-Ruel, Paris. The Eagle’s Nest, The Forest of Fontainebleau was definitely owned by the gallery Goupil et Cie by 1880, and at that time they commissioned a reproduction in print by Théophile-Narcisse Chauvel (1831–1910) (Fig. 5).24Goupil et Cie renamed itself Boussod, Valadon et Cie in 1884. Linda Whiteley, “Boussod, Valadon et Cie,” 2003, Grove Art Online, https://doi.org/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T010638. The Nelson-Atkins etching is a rare trial proof, stamped with an early date of December 30, 1880. It was subsequently owned by the noted animal painter Emile van Marcke de Lummen (1827–90), who then passed it on to his daughter, Marie Dieterle (1856–1935), also a noted animalier. The bovine subject would undoubtedly have appealed to these two artists. Marie then gifted the painting to her son, Jean, who retained it until 1930, in which year it was acquired by the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art as one of the first French paintings in the museum’s collection.

Notes

-

Thanks to Nicole R. Myers, Meghan L. Gray, and Danielle Hampton Cullen for their assistance in providing this new identification based on an annotation on the final state of the Théophile-Narcisse Chauvel etching (Bibliothèque Nationale de France) after Rousseau’s picture. The annotation reads “LE NID DE L’AIGLE / Gravé par Th[éophile] Chauvel d’aprés le tableau original de Th[éodore] Rousseau” (The Eagle’s Nest/ Engraved by Th[éophile] Chauvel after the original painting by Th[éodore] Rousseau). All translations by Simon Kelly unless otherwise indicated. For the Nelson-Atkins example of the Chauvel etching, see Fig. 5.

-

Charles-François Denecourt, Le Palais et la Forêt de Fontainebleau: Guide Historique et Descriptif (Fontainebleau, 1840), 22.

-

Charles-François Denecourt, Camp de Fontainebleau, Sa Position Topographique . . . Cet Opuscule fait Suite au Guide du Voyageur dans la Forêt de Fontainebleau (Fontainebleau: S. Petit, 1839).

-

Charles-François Denecourt, Le Palais et la Forêt de Fontainebleau: Guide Historique et Descriptif, rev. ed. (Fontainebleau, 1856), 206–7. For this site, see Olivier Blaise, “Le Nid de l’Aigle,” Fontainbleau-Photo, accessed June 13, 2025, https://www.fontainebleau-photo.fr/2018/02/le-nid-de-laigle.html; and “Le Bouquet du Nid de l’Aigle (arbre disparu),” En Foret de Fontainebleau, Hier et Aujourd’hui, accessed June 13, 2025, https://foret-fontainebleau.teria.fr/fiches.html?ref1=418&ref2=15&checkbox=paint,photo,card.

-

Denecourt, Palais et la Forêt de Fontainebleau (1856), 207.

-

This number was delivered in 1829 at the height of stone production. Paul Domet, Histoire de la Forêt de Fontainebleau (Paris: Librarie Hachette et Cie, 1873), 217. See also Kimberly Jones, “Landscapes, Legends, Souvenirs, Fantasies: The Forest of Fontainebleau in the Nineteenth Century,” in In the Forest of Fontainebleau: Painters and Photographers from Corot to Monet, ed. Kimberly Jones, exh. cat. (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2007), 6.

-

For such a reading, see Greg M. Thomas, Art and Ecology in Nineteenth-Century France: The Landscapes of Théodore Rousseau (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000), particularly the discussion of Forest Interior [Old Watering Hole of Bas-Bréau] (1836–37; Musée du Louvre, RF 291, on deposit at Musée d’Orsay) on pp. 165–67.

-

“En artiste-trappeur.” Alfred Sensier, Souvenirs sur Théodore Rousseau (Paris: Léon Techener, 1872), 117.

-

Thomas, Art and Ecology, 155, 251n19.

-

Domet, Histoire de la Forêt de Fontainebleau, 209–10.

-

See Mary Schafer and John Twilley’s accompanying technical entry.

-

Schafer and Twilley, technical entry.

-

Schafer and Twilley, technical entry.

-

This dating contrasts with the date of 1860–65 in the Rousseau catalogue raisonné: Michel Schulman, Théodore Rousseau, 1812–1867: Catalogue Raisonné de l’Oeuvre Peint (Paris: Éditions de l’Amateur, 1999), no. 642, p. 326. Rousseau’s paint application in this picture, however, is very different from the uniform, “proto-pointillistpointillism: A technique of painting using tiny dots of pure colors, which when seen from a distance are blended by the viewer’s eye. It was developed by French Neo-Impressionist painters in the mid-1880s as a means of producing luminous effects.” brushwork characteristic of his newly produced work of the early 1860s.

-

For a recent discussion of the Nelson-Atkins picture within the context of these related works and Rousseau’s interest in bituminous “dark matter,” see Kelly Presutti, Land into Landscape: Art, Environment, and the Making of Modern France (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2024), 126–28. See also Simon Kelly, Théodore Rousseau and the Rise of the Modern Art Market: An Avant-Garde Landscape Painter in Nineteenth-Century France (New York: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2021), 19–23.

-

“Quand Jules Dupré vit la Descente des Vaches . . . elle lui sembla aussi inattendue, aussi prodigieuse que la venue de la terrible Méduse de Géricault” (When Jules Dupré saw the Descent of the Cows . . . it seemed to him as unexpected, as extraordinary as the appearance of the terrible Medusa of Géricault). Sensier, Souvenirs, 79.

-

Rousseau’s rapidly applied paint layers, including emerald green and bituminous materials, subsequently caused the paint surface to darken and crack over time. See René Boitelle, Klaas Jan van den Berg, Muriel Geldof, and Georgiana Languri, “Descending into the Details of Th. Rousseau’s ‘La Descente des Vaches’ (Museum Mesdag, The Hague)—Technical Research of a Darkened Painting,” in “Deterioration of Artists’ Paints”: A Joint Meeting of ICOM-CC Working Groups Paintings 1 and 2 and The Paintings Section, UKIC, London, 10–11 September, 2001, ed. Alan Phenix (London: United Kingdom Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works and International Council of Museums, 2001), 27–31. See also Katrin Keune, Jaap Boon, René Boitelle, and Yoshiko Shimadzu, “Degradation of Emerald Green in Oil Paint and Its Contribution to the Rapid Change in Colour of the Descente des Vaches (1834–35) Painted by Théodore Rousseau,” Studies in Conservation 58, no. 3 (July 2013): 199–210.

-

“Il aimait à condenser les splendeurs des températures d’automne, à saisir ces couchers de soleil d’or.” Sensier, Souvenirs, 117.

-

“Il aime les natures bleuâtres, les crépuscules, les couchers de soleil singuliers et trempés d’eau, les gros ombrages où circulent les brises, les grands jeux d’ombres et de lumière. Sa couleur est magnifique, mais non pas éclatante. Ses ciels sont incomparables pour leur mollesse floconneuse. Qu’on se rappelle quelques paysages de Rubens et de Rembrandt, qu’on y mêle quelques souvenirs de peinture anglaise, et qu’on suppose, dominant et réglant tout cela, un amour profond et sérieux de la nature, on pourra peut-être se faire une idée de la magie de ses tableaux.” See Charles Baudelaire, “Salon de 1846,” in Art in Paris, 1845–62: Salons and Other Exhibitions Reviewed by Charles Baudelaire, ed. and trans. Jonathan Mayne (London: Phaidon Press, 1965), 108–9.

-

Schafer and Twilley, technical entry.

-

See Durand-Ruel stock book, 1868–73, purchases made fifty-fifty with Hector Brame, no. 10,633, Les Archives Durand-Ruel, Paris. See also the listing in Kelly, Théodore Rousseau and the Rise of the Modern Art Market, appendix 3, p. 232.

-

For more about Herman, see Paul-Louis Durand-Ruel and Flavie Durand-Ruel, eds., Paul Durand-Ruel: Memoirs of the First Impressionist Dealer (Paris: Flammarion, 2014), 40, 112, 250n86.

-

See Durand-Ruel’s purchase of Défilé de troupes dans une forêt (Descent of Herds in a Forest), the title in the 1872 stock book entry, from Herman for 200 francs. It was sold to De Knyff on September 2, 1872, for 500 francs. See Durand-Ruel stock book, 1868–73, no. 1880, Les Archives Durand-Ruel, Paris.

-

Goupil et Cie renamed itself Boussod, Valadon et Cie in 1884. Linda Whiteley, “Boussod, Valadon et Cie,” 2003, Grove Art Online, https://doi.org/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T010638. The Nelson-Atkins etching is a rare trial proof, stamped with an early date of December 30, 1880.

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Mary Schafer and John Twilley, “Théodore Rousseau, The Eagle’s Nest, Forest of Fontainebleau, ca. 1837–67,” technical entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.532.2088.

MLA:

Schafer, Mary and John Twilley. “Théodore Rousseau, The Eagle’s Nest, Forest of Fontainebleau, ca. 1837–67,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.532.2088.

Until recently, The Eagle’s Nest, Forest of Fontainebleau was entitled Cows Descending the Hill at Sunset and was considered to be a variant of three paintings Rousseau completed in the mid-1830s: a large painting submitted to the Paris SalonsSalon, the: Exhibitions organized by the French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture (Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture) and its successor the Academy of Fine Arts (Académie des Beaux Arts), which took place in Paris from 1667 onward. of 1836 and 1838, The Descent of the Cattle in the Haut-Jura Mountains (Fig. 3; 1834–35; The Mesdag Collection, The Hague, HWM0286); an oil sketch (ca. 1834–35; The Mesdag Collection, The Hague, HWM0287); and a painted study (1834–36; Musée de Picardie, Amiens, Inv. Nr. 4371). Additionally, opinion on the date of the Nelson-Atkins painting was divided between the mid-1830s, consistent with these related works, and the later date range of 1860–65 listed in Michel Schulman’s 1999 catalogue raisonné.1Michel Schulman, Théodore Rousseau, 1812–1867: Catalogue Raisonné de l’Œuvre Peint (Paris: Èditions de l’Amateur, 1999), 2:326. Here, the painting (no. 642) is titled Vaches Descendant des Montagnes le Soir (Cows Descending the Mountains in the Evening).

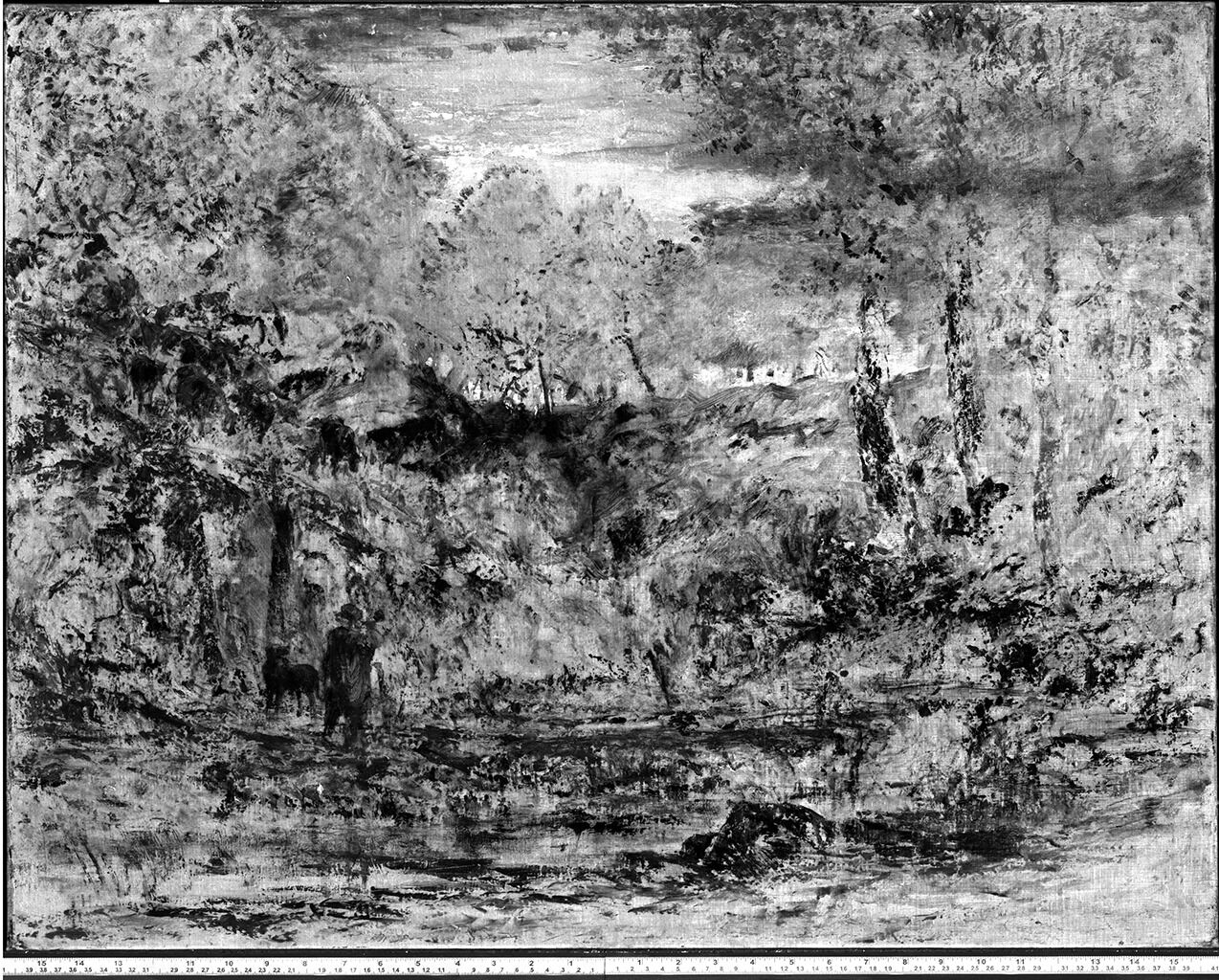

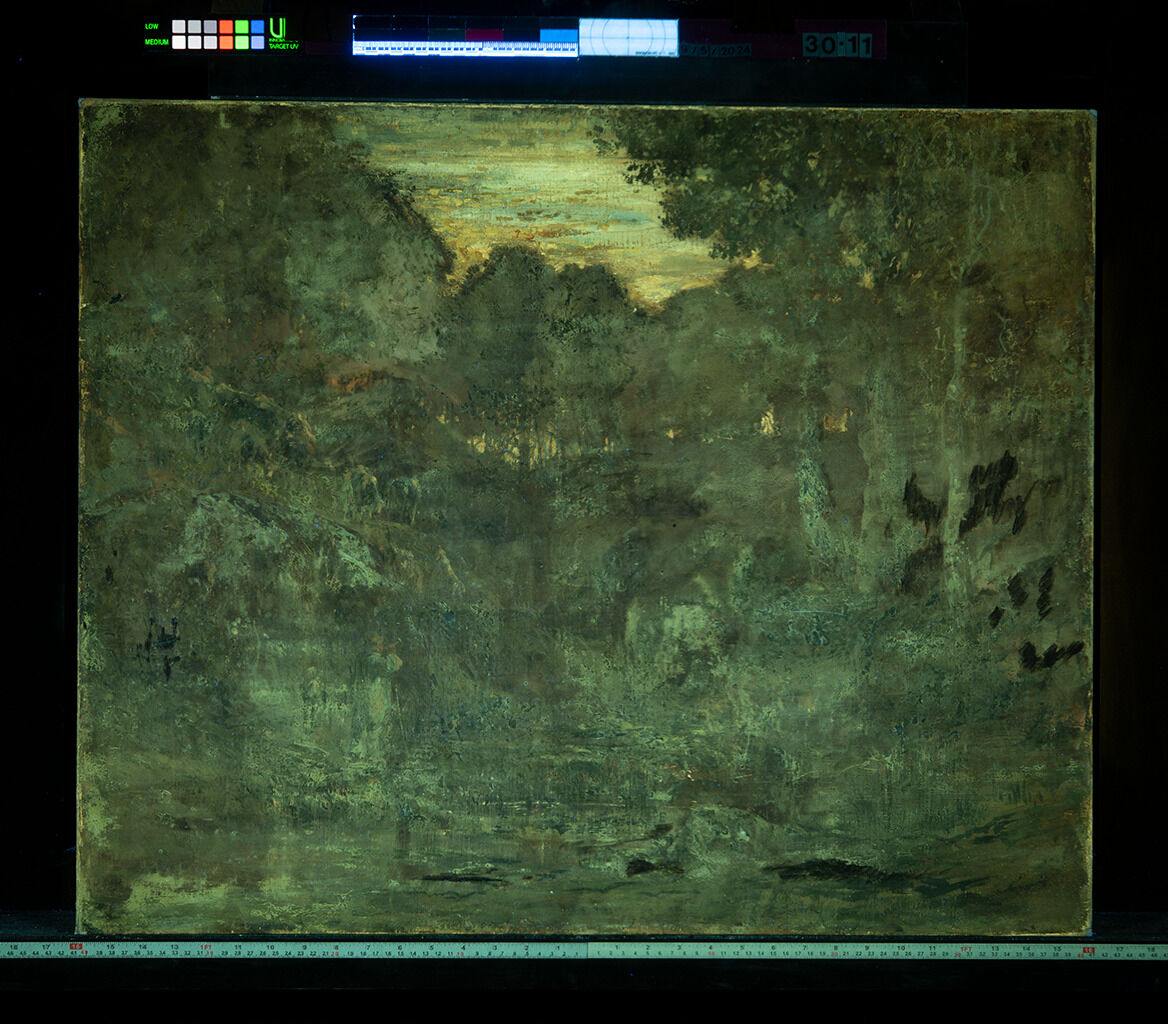

Within forty years after its completion, the Mesdag’s Salon painting (Fig. 3) suffered a ruinous transformation, as Rousseau’s medium-rich layers darkened, and wide fissuring (traction crackingtraction cracks: Also known as drying cracks, these are formed as the paint dries. They are usually the result of a “lean” paint with a small percentage of oil drying faster than an underlying “fat” paint layer with a higher percentage of oil. The quick drying of the top layer causes the paint layer to shrink and crack.) deformed the paint film.2Alfred Sensier, Souvenirs sur Théodore Rousseau (Paris: Leon Techener, 1872), 77–78. Although the Nelson-Atkins painting is also dark in appearance and somewhat illegible, it lacks the severe traction cracking of the Salon painting. A photograph of the Nelson-Atkins painting without exposure adjustment conveys its darkened appearance and the difficulty viewing its terrain (Fig. 6).

Technical study of the Nelson-Atkins painting first began in 2013 with the intention of studying Rousseau’s painting technique in relation to other works, identifying his pigments, determining whether any material changes contributed to the landscape’s dark appearance, and if possible, addressing the date of the painting based on the dates of introduction and availability of its pigments.3The authors are grateful to both Simon Kelly and Nicole R. Myers, former associate curators of European paintings and sculpture, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, for their curatorial contributions in the early stages of this project. Over the course of this collaborative research, new avenues of inquiry were opened as a consequence of new findings. The painting has now been renamed and reinterpreted as The Eagle’s Nest, Forest of Fontainebleau by Simon Kelly in the accompanying essay, and the technical findings provide new means with which to study Rousseau and his materials.

Overview of the Painting Construction

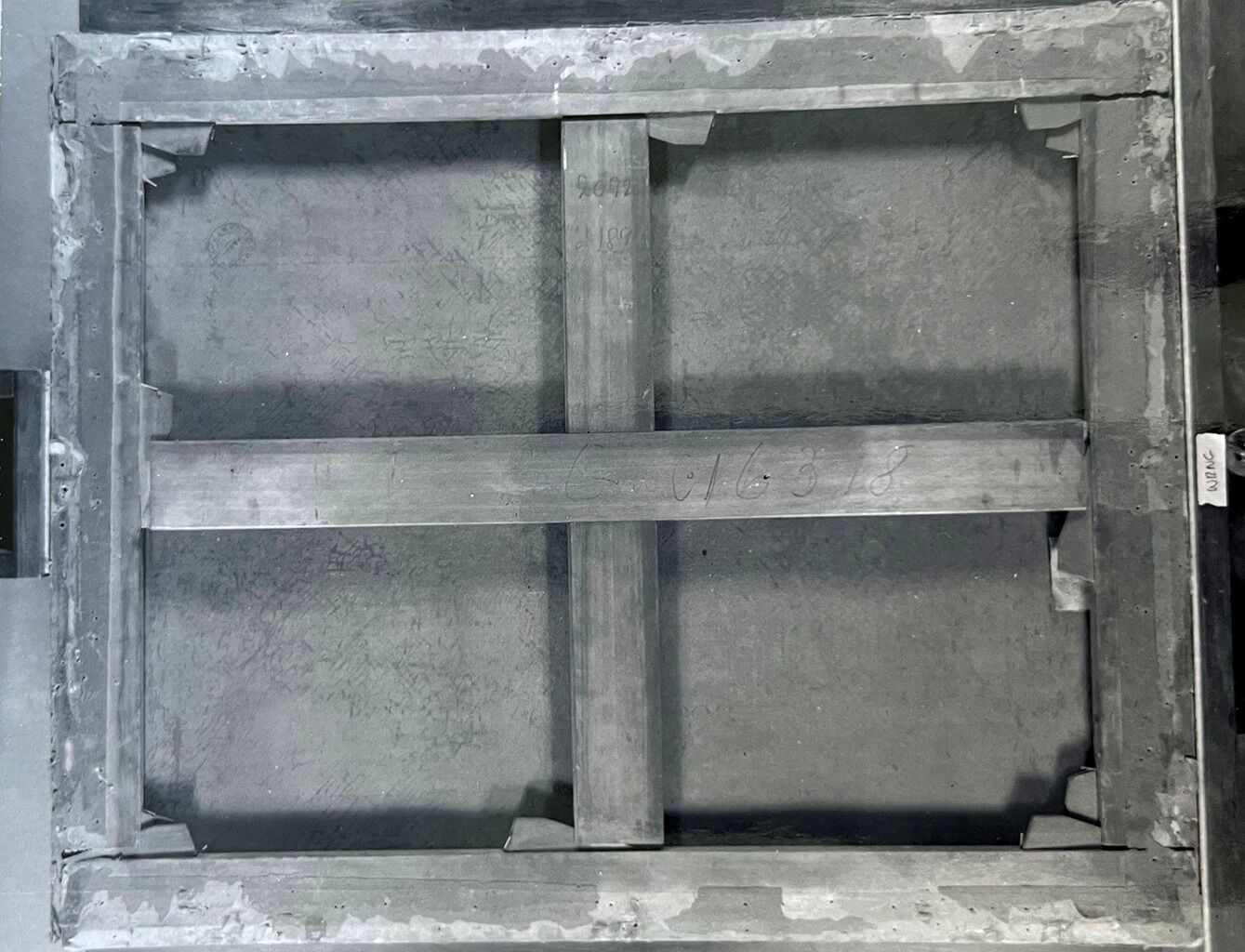

The Eagle’s Nest, Forest of Fontainebleau is close in size to a no. 25 figure standard-formatstandard-format supports: Commercially prepared supports available through art suppliers, which gained popularity in the nineteenth century during the industrialization of art materials. Available in three formats figure (portrait), paysage (landscape), and marine (marine), these were numbered 1 through 120 to indicate their size. For each numbered size, marine and paysage had two options available: a larger format (haute) and smaller (basse) format. canvas,4See the Bourgeois Ainé catalogue of 1888 in David Bomford, Jo Kirby, John Leighton, and Ashok Roy, Art in the Making: Impressionism (London: Yale University Press, 1990), 46. oriented horizontally. Although Rousseau acquired his materials from a variety of colormenartist supplier(s): Also called colormen and color merchants. Artist suppliers prepared materials for artists. This tradition dates back to the Medieval period, but the industrialization of the nineteenth century increased their commerce. It was during this time that ready-made paints in tubes, commercially prepared canvases, and standard-format supports were available to artists for sale through these suppliers. It is sometimes possible to identify the supplier from stamps or labels found on the reverse of the artwork. See also canvas stamp, supplier mark, and *color merchant., no supplier stampcanvas stamp: An ink stamp, often present on the reverse of the canvas, signifying the company that sold or prepared the canvas. As these companies sometimes performed framing and restorations, these stamps could also reflect these services. See also supplier mark. was noted on the canvas reverse during the 1969 treatment before the painting was wax-linedlining: A procedure used to reinforce a weakened canvas that involves adhering a second fabric support using adhesive, most often a glue-paste mixture, wax, or synthetic adhesive. (Fig. 7).5Stéphanie Constantin, “The Painters of the Barbizon Circle and Landscape Paintings: Technique and Working Methods” (PhD Diss., Courtauld Institute of Art, 2001), 113–41; and Pascal Labreuche, “Rousseau (Théodore) 1812–1867,” Guide Labreuche: Guide historique des fournisseurs de matériel pour artistes à Paris, 1790–1960, 2014, https://www.guide-labreuche.com/en/collection/artists-suppliers/rousseau-theodore., 6James Roth, June 15, 1969, examination report, NAMA conservation file, 30-11. The original canvas is a tightly woven plain weaveplain weave: A basic textile weave in which one weft thread alternates over and under the warp threads. Often this structure consists of one thread in each direction, but threads can be doubled (basket weave) or tripled to create more complex plain weave. Plain weave is sometimes called tabby weave. containing numerous slubs and weave irregularities. The tacking marginstacking margins: The outer edges of canvas that wrap around and are attached to the stretcher or strainer with tacks or staples. See also tacking edge. are preserved, and the presence of white groundground layer: An opaque preparatory layer applied to the support, either commercially or by the artist, to prevent absorption of the paint into the canvas or panel. See also priming layer. continuing onto these edges confirms that the dimensions of the painting have not been significantly altered. The ground layer, a mixture of lead white with crushed barite, was commercially applied.

Although Rousseau’s painting methods were experimental, his initial process reflected his academic training, which typically began with an ébauche, a step that he described as “the nerve-centre” of his painting.7Antoine Terrasse, L’Univers de Thèodore Rousseau (Paris: Henri Scrépel, 1976), 50. The ébauche involved a preliminary sketch of the motif, followed by brushstrokes of a dilute mixture of oil and earth pigments. Often referred to as “sauce” by artists of this period, this transparent tint was used to strengthen sketch lines and roughly establish areas of shadow. With the principal masses roughly laid in, the artist would next address the brightest highlights and midtones.8Thomas Couture, Conversations on Art Methods, trans. S. E. Stewart (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1879), 7–8. See also Albert Boime, The Academy and French Painting in the Nineteenth Century (New York: Phaidon, 1971), 37.

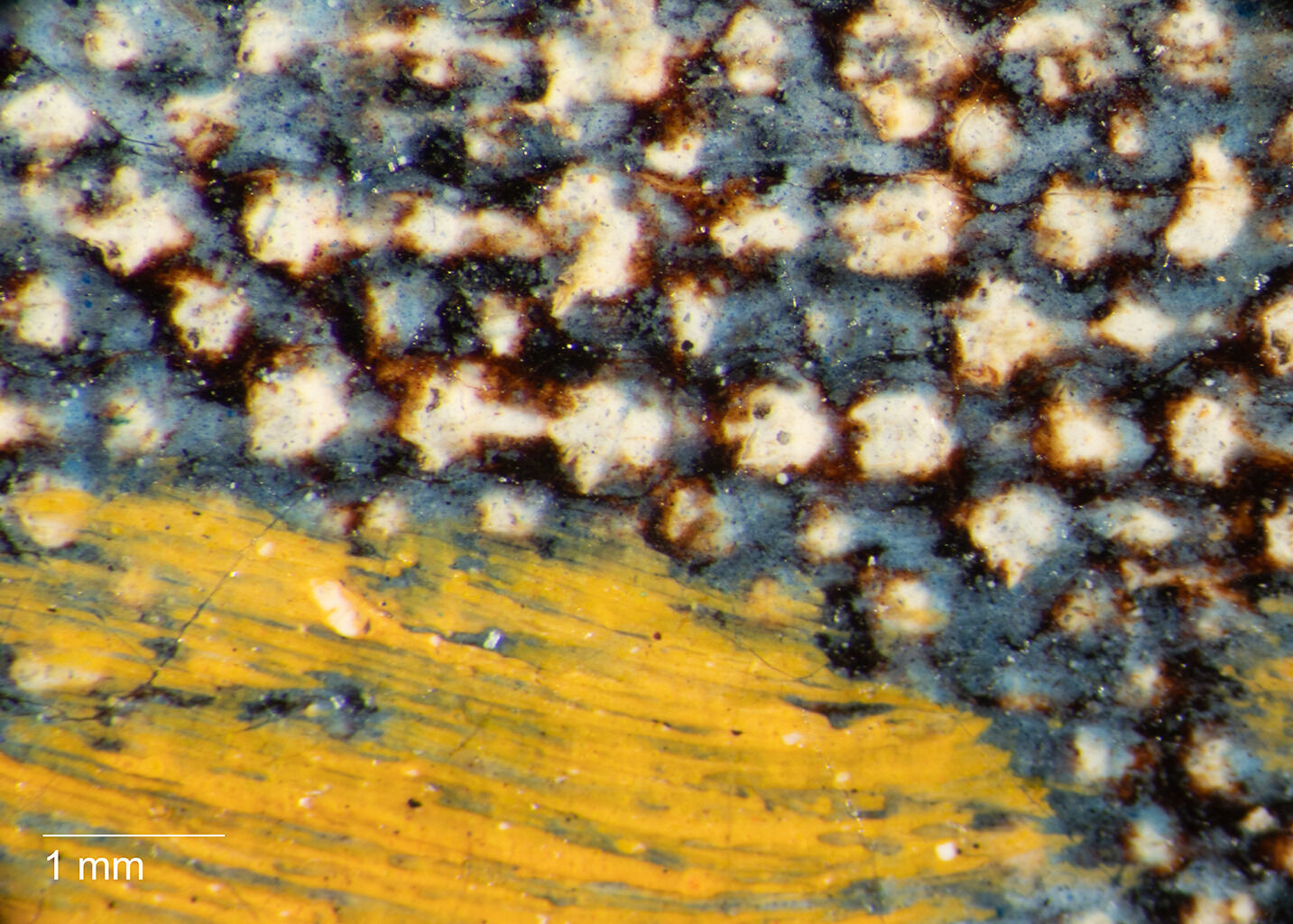

Accounts of Rousseau’s sketching materials vary widely from drawn media—graphite, black crayon, chalk, and charcoal—to ink or fluid brown paint strokes.9Many of Rousseau’s paintings are described as having one of two methods for the initial step. The first method involved a drawn sketch using either charcoal or black crayon, which was followed by dilute brown paint or ink to denote shading. The second method consisted of a graphite sketch, reinforced a second time with graphite or a thin paintbrush. See Constantin, “The Painters of the Barbizon Circle,” 222. According to Alfred Sensier (1815–77), Rousseau sketched out his compositions with charcoal, black crayon, white chalk, sanguine chalk (rarely), graphite, graphite and ink, or a combination of several materials. Sensier, Souvenirs sur Théodore Rousseau, 102. Ludovic Letrône (1832?–89), Rousseau’s student, described a simpler process: “[Rousseau] often laid-in his paintings as follows: with a single color, Mummy, for instance, without having set out the composition in white chalk first, without pentimenti, with an extraordinary confidence he took it to a very advanced stage.” Ludvic Letronne to Phillipe Burty, undated [ca. 1868?], Musée du Louvre, Paris, Département des Arts Graphiques, Bs b22 L177; cited and translated in Constantin, “Painters of the Barbizon Circle,” 222–23. Despite the belief that he often produced more detailed underdrawingsunderdrawing: A drawn or painted sketch beneath the paint layer. The underdrawing can be made from dry materials, such as graphite or charcoal, or wet materials, such as ink or paint. for his forest scenes, no sign of a drawn sketch beneath The Eagle’s Nest was revealed by infrared reflectographyinfrared reflectography (IRR): A form of infrared imaging that exploits the behavior of painting materials at wavelengths beyond those accessible to infrared photography. These advantages sometimes include a continuing increase in the transparency of pigments beyond wavelengths accessible to infrared photography (i.e, beyond 1,000 nanometers), rendering underdrawing more clearly. The resulting image is called an infrared reflectogram. Devices that came into common use in the 1980s such as the infrared vidicon effectively revealed these features but suffered from lack of sharpness and uneven response. Vidicons continue to be used out to 2,200 nanometers but several newer pixelated detectors including indium gallium arsenide and indium antimonide array detectors offer improvements. All of these devices are optimally used with filters constraining their response to those parts of the infrared spectrum that reveal the most within the constraints of the palette used for a given painting. They can be used for transmitted light imaging as well as in reflection. or microscopy.10Constantin, “Painters of the Barbizon Circle,” 221., 11It is possible that Rousseau’s underdrawing cannot be easily detected with these examination tools. For instance, Rousseau applied fluid brown paint strokes rather than a drawn sketch beneath The Forest in Winter at Sunset (Fig. 4). See Charlotte Hale, technical note, “Technical Study of A Forest in Winter at Sunset,” 2020, Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/438816, accessed September 16, 2024. Rousseau’s use of thin, red-brown sauce, a mixture of earth pigments and a tin-based, dark red lakelake pigment: An organic pigment manufactured by precipitating a soluble, natural colorant onto a colorless or white, insoluble, inorganic substrate. Historically, natural colorants were extracted from plants and insects. The substrate is traditionally hydrated aluminum oxide, but other substrates such as chalk (calcium carbonate), clay, or gypsum (calcium sulphate) have also been used., produced a warm tonality that remains prominent across the finished landscape, although the red-brown color shifts to brown and green in parts of the foreground.12Similar color variation in the sauce has been observed in Chopping Trees in the Ile de Croissy (1847; Mesdag Museum) and A Forest in Winter at Sunset (Fig. 4). See Constantin, “Painters of the Barbizon Circle,” 223; and Hale, technical note. With this same color and thicker application, Rousseau began to define the angles of the rocky ravine, while leaving the three tree trunks on the right in reservereserve: An area of the composition left unpainted with the intention of inserting a feature at a later stage in the painting process., with the initial red-brown tint exposed.13This description is similar to the techniques outlined for the Amiens and Salon Mesdag paintings. See René Boitelle, Klaas Jan van den Berg, Muriel Geldof, and Georgiana Languri, “Descending into the Details of Th. Rousseau’s ‘La Descente des Vaches’ (Museum Mesdag, The Hague)—Technical Research of a Darkened Painting,” in “Deterioration of Artists’ Paints”: A Joint Meeting of ICOM-CC Working Groups Paintings 1 and 2 and The Paintings Section, UKIC, London, 10–11 September, 2001, ed. Alan Phenix (London: United Kingdom Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works and International Council of Museums, 2001), 29. The presence of this layer beneath the blue sky contradicts artist manuals of the period that caution against potential darkening of the landscape’s brightest feature (Fig. 8).14Pierre Louis Bouvier, Manuel des jeunes artistes et amateurs en peinture (Paris: F. G. Levrault, 1832), 151. However, the discovery of an underlying composition beneath The Eagle’s Nest (discussed below) could account for this unusual layering. Finally, a few glimpses of bright blue and gray paint beneath the trees and foreground are present on top of the white ground (Figs. 9 and 10). Considering the artist’s similar use of blue in drawings that are highlighted with watercolor (Fig. 11), these underlying brushstrokes might be associated with some aspect of the ébauche.15For other Rousseau drawings with blue and gray watercolor in the trees, see Michel Schulman, Marie Bataillès, and Virginie Sérafino, Théodore Rousseau, 1812–1867: Catalogue Raisonné de L’Œuvre Graphique, vol. 1 (Paris: Editions de l’amateur, Editions des catalogues raisonnés, 1997)., 16Paint strokes of black, dark brown, and dark blue appear to have roughly marked the contours of elements in the lower landscape of the Mesdag oil sketch. Boitelle et al., “Descending into the Details of Th. Rousseau’s ‘La descente des vaches,’” 28.

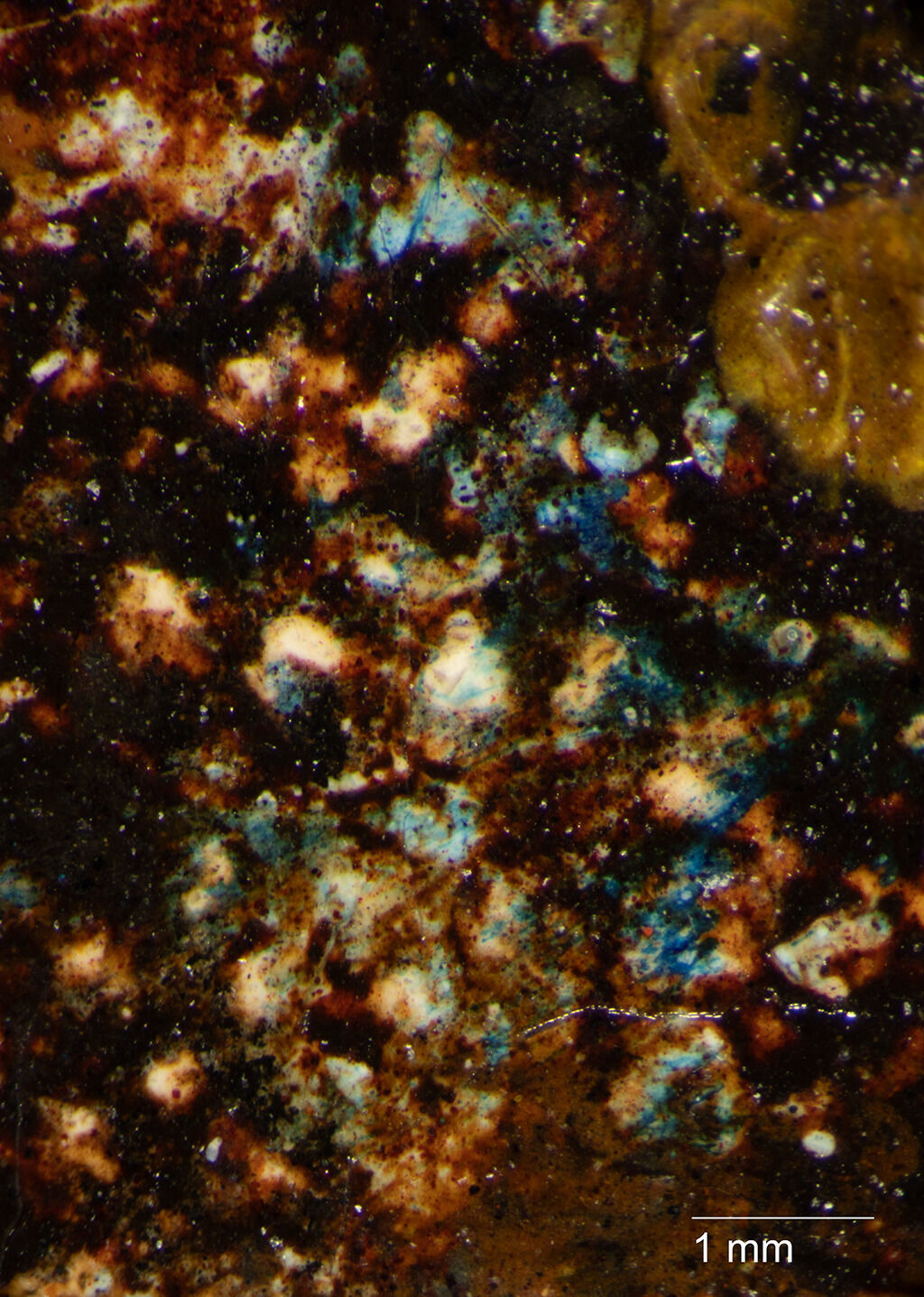

Fig. 9. Photomicrograph of the lower right foreground of The Eagle’s Nest, Forest of Fontainebleau (ca. 1837–67), revealing underlying blue paint

Fig. 9. Photomicrograph of the lower right foreground of The Eagle’s Nest, Forest of Fontainebleau (ca. 1837–67), revealing underlying blue paint

Fig. 10. Photomicrograph of The Eagle’s Nest, Forest of Fontainebleau (ca. 1837–67), showing bright blue paint beneath the reddish-brown tinting layer

Fig. 10. Photomicrograph of The Eagle’s Nest, Forest of Fontainebleau (ca. 1837–67), showing bright blue paint beneath the reddish-brown tinting layer

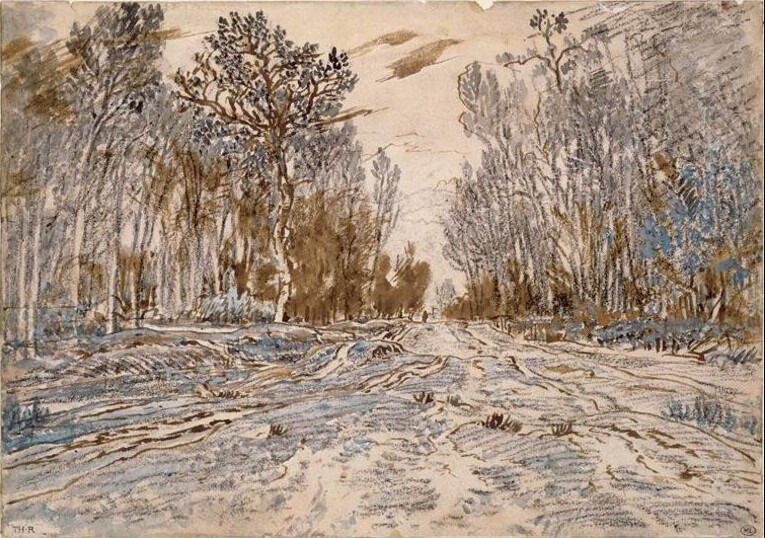

Fig. 11. Théodore Rousseau, The King’s Causeway, in the Forest of Fontainebleau, ca. 1850, charcoal, brown and gray wash, and watercolor highlights on paper, 7 7/8 x 11 3/16 in. (20 x 28.4 cm), Musée du Louvre, Paris, RF 23339. Photo: © RMN, Musée du Louvre / Jean-Gilles Berizzi

Fig. 11. Théodore Rousseau, The King’s Causeway, in the Forest of Fontainebleau, ca. 1850, charcoal, brown and gray wash, and watercolor highlights on paper, 7 7/8 x 11 3/16 in. (20 x 28.4 cm), Musée du Louvre, Paris, RF 23339. Photo: © RMN, Musée du Louvre / Jean-Gilles Berizzi

In spite of the landscape’s dark and murky palette, subtle color variations are present amid the semitransparent brown paint of the trees. Figure 12 shows one such detail in which deep ultramarine blue is visible. The trees and foreground were rendered from dark to light with painterly brushwork, palette knife applications, and, at times, a subtractive painting method. An example of the latter is apparent on the upper right, where Rousseau removed paint with a dry brush to reveal the ground and gray paint, creating a small passage of sky (Fig. 13). With his palette knife, or an equivalent sharp tool, he scratched into the wet paint, loosely marking the lower right embankment and a few branches among the upper right trees. Again, using a subtractive method, several short angular marks were also made into the brown paint at the right horizon (Fig. 14) to portray the passage of light through the trees, while a similar effect on the horizon was achieved with additions of thick yellow impastoimpasto: A thick application of paint, often creating texture such as peaks and ridges..

Fig. 12. Photomicrograph of The Eagle’s Nest, Forest of Fontainebleau (ca. 1837–67), revealing deep blue ultramarine in the dark brown paint of the upper left tree

Fig. 12. Photomicrograph of The Eagle’s Nest, Forest of Fontainebleau (ca. 1837–67), revealing deep blue ultramarine in the dark brown paint of the upper left tree

Fig. 13. Photomicrograph of The Eagle’s Nest, Forest of Fontainebleau (ca. 1837–67), revealing an area of reddish-brown paint that was removed by the artist’s dry brush

Fig. 13. Photomicrograph of The Eagle’s Nest, Forest of Fontainebleau (ca. 1837–67), revealing an area of reddish-brown paint that was removed by the artist’s dry brush

Fig. 14. Photomicrograph of incised marks on the horizon, The Eagle’s Nest, Forest of Fontainebleau (ca. 1837–67)

Fig. 14. Photomicrograph of incised marks on the horizon, The Eagle’s Nest, Forest of Fontainebleau (ca. 1837–67)

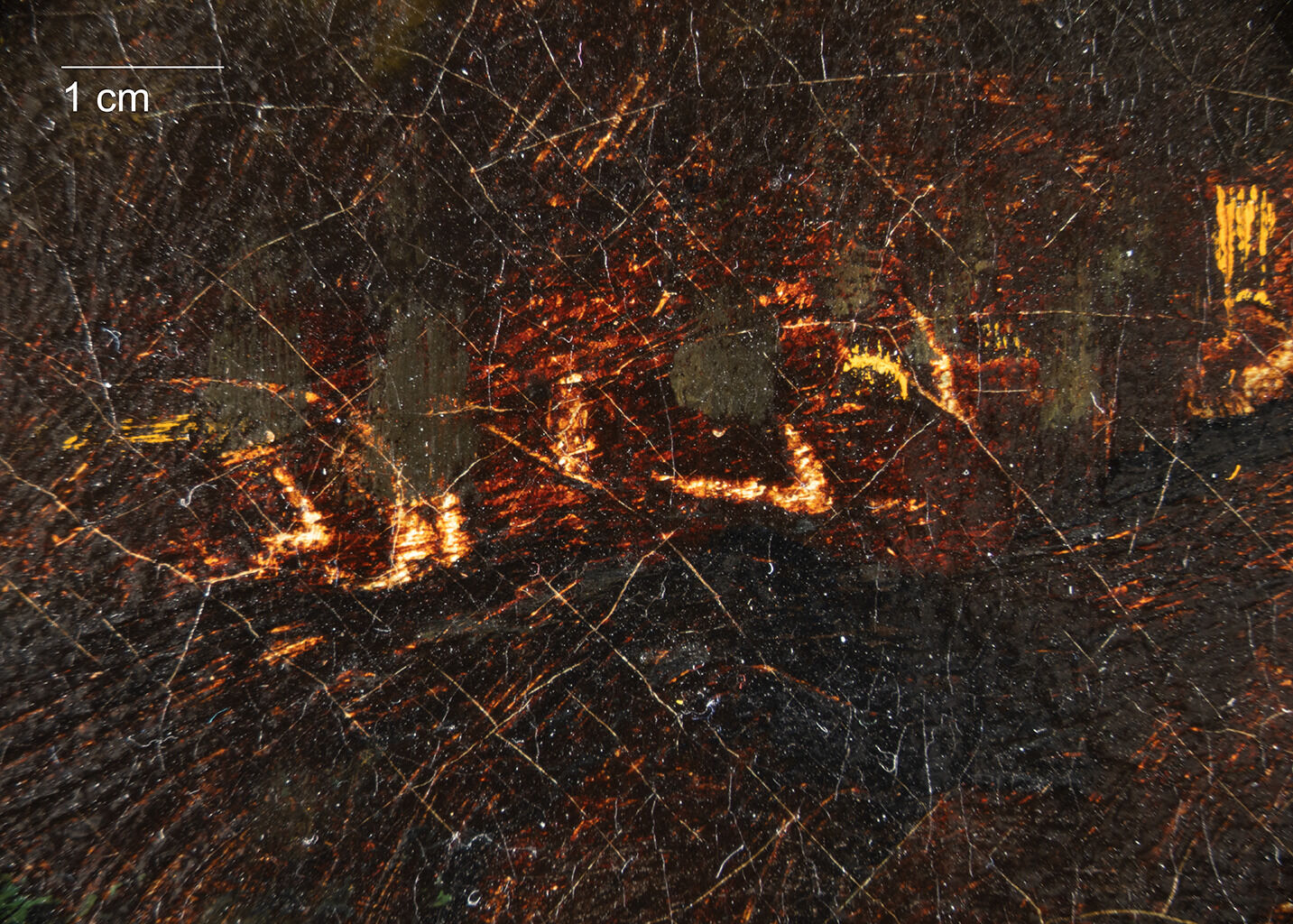

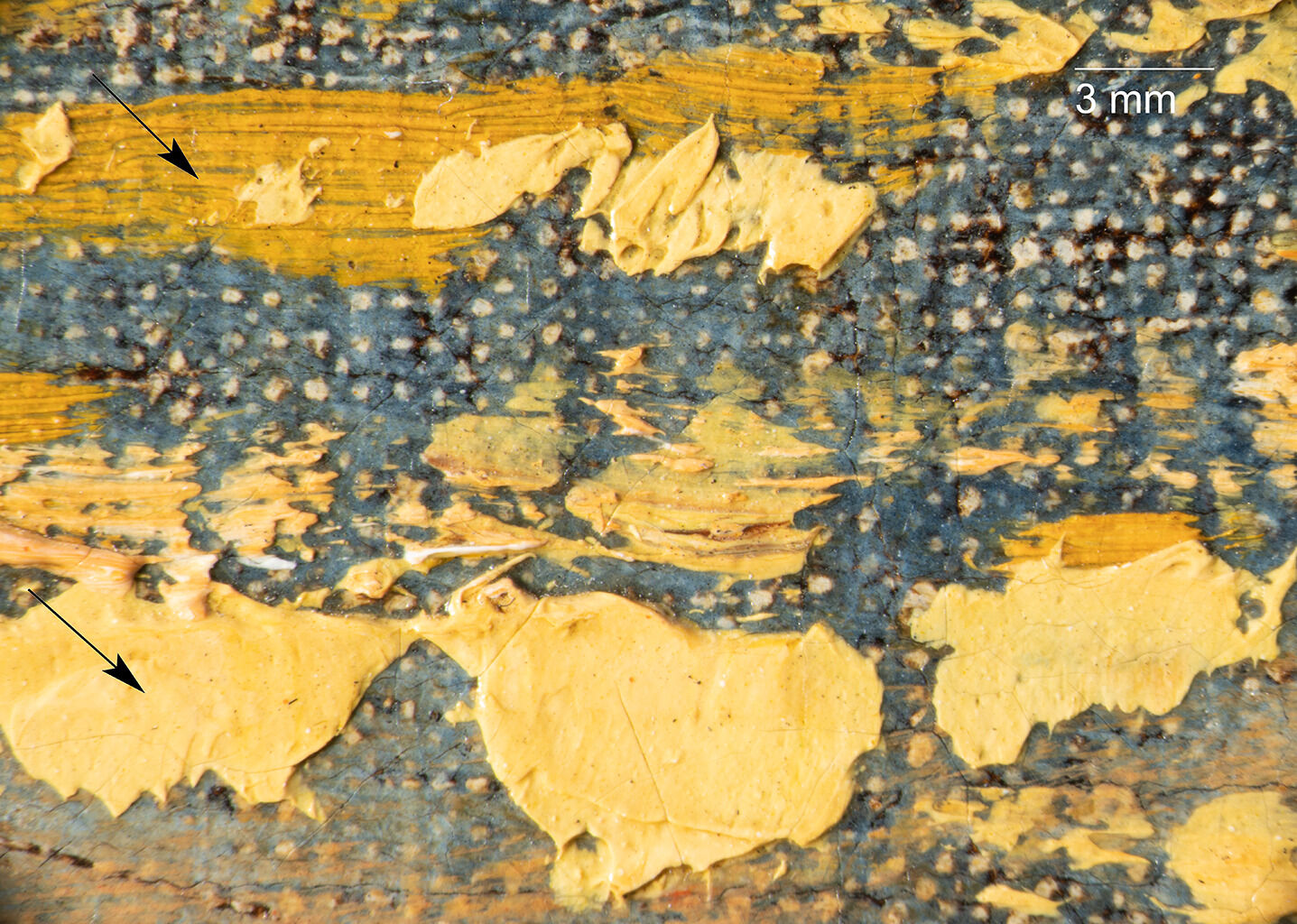

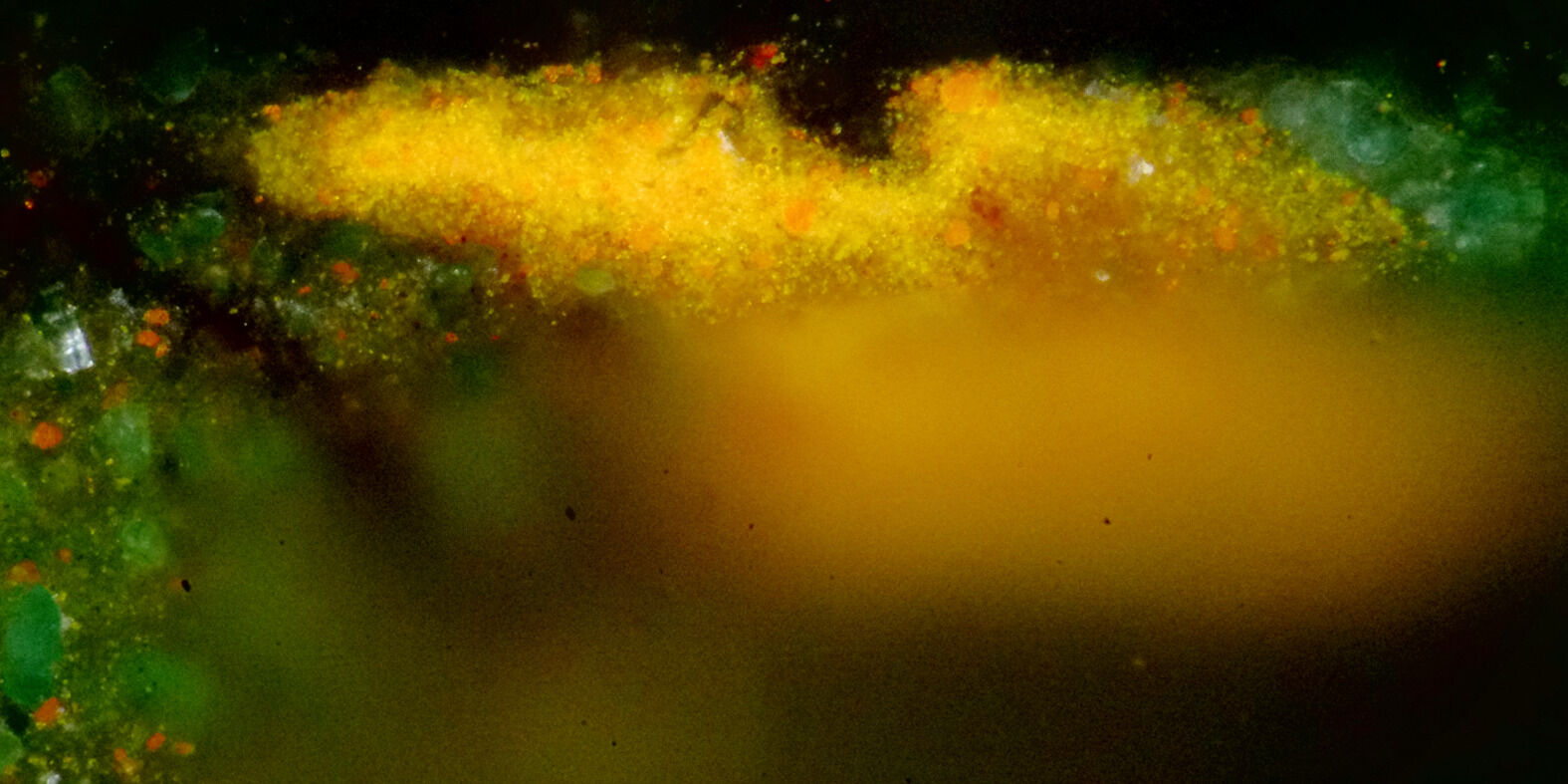

Throughout the landscape Rousseau scraped the paint surface with a palette knife, exposing dots of white ground at the upper points of the canvas weave texture. While the scraped paint could be mistaken for abrasion, subsequent paint strokes cover the exposed layers and confirm that they are part of the artist’s technique. Rousseau remarked on his unconventional techniques: “‘One uses everything, even diabolical conjurings,’ he added laughingly, ‘and when I have employed all resources of colour, I have used the scratcher, the thumb, and if still necessary the handle of my brush.’”17Sensier, Souvenirs sur Théodore Rousseau, 199–200. Translation in David Croal Thomson, The Barbizon School of Painters: Corot, Rousseau, Diaz, Millet, Daubigny, Etc. (London: Chapman and Hall, 1890), 154. In fact, at the top of the left ravine, Rousseau swiped into the yellow-brown paint with his finger, leaving a fingerprint in the wet paint (Fig. 15). The artist used a palette knife to scrape paint horizontally across the upper sky and to deposit thick highlights onto the tree trunks and foreground rocks. Vegetation was dryly painted with 1/8–1/4 inch brushes, while downward strokes of a flat brush produced reflections in the water. Short horizontal dabs of chrome yellow and orange paint, applied by palette knife and brush, produce varying textures in the lower sky (Fig. 16).

Fig. 15. Photomicrograph of the artist’s fingerprint made in the wet paint, The Eagle’s Nest, Forest of Fontainebleau (ca. 1837–67)

Fig. 15. Photomicrograph of the artist’s fingerprint made in the wet paint, The Eagle’s Nest, Forest of Fontainebleau (ca. 1837–67)

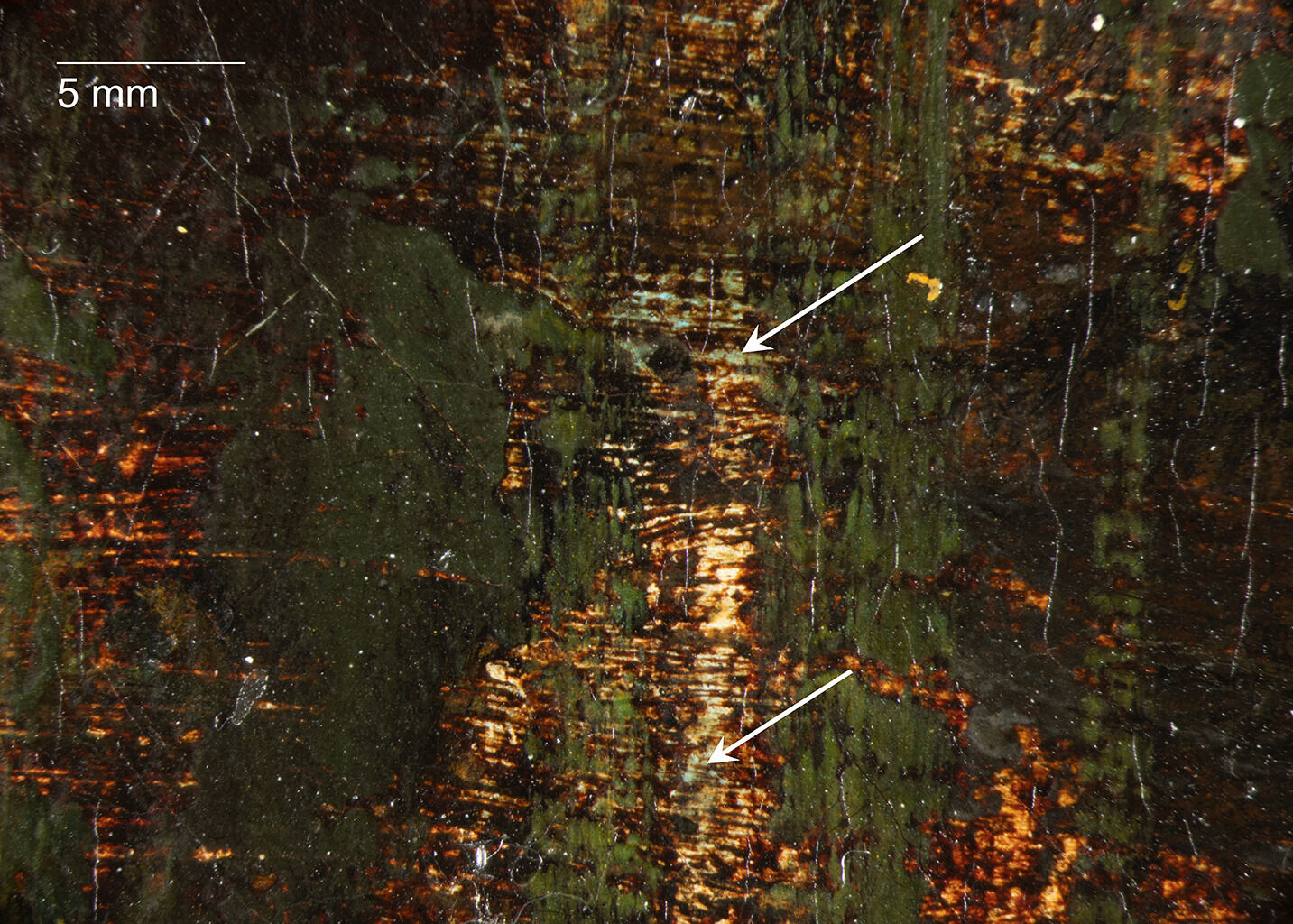

Fig. 16. Thick yellow and orange paint in the lower sky of The Eagle’s Nest, Forest of Fontainebleau (ca. 1837–67), applied by both brush (top arrow) and palette knife (bottom arrow)

Fig. 16. Thick yellow and orange paint in the lower sky of The Eagle’s Nest, Forest of Fontainebleau (ca. 1837–67), applied by both brush (top arrow) and palette knife (bottom arrow)

Fig. 17. A: the distribution of arsenic in the areas mapped by MA-XRF, corresponding to emerald green that surrounds the negative spaces occupied by trees on the left of the composition; B: visual appearance of the painting for comparison; C: the distribution of chromium, corresponding to viridian, chrome yellow, and zinc yellow, which also define negative spaces occupied by the former trees. The Eagle’s Nest, Forest of Fontainebleau (ca. 1837–67)

Fig. 17. A: the distribution of arsenic in the areas mapped by MA-XRF, corresponding to emerald green that surrounds the negative spaces occupied by trees on the left of the composition; B: visual appearance of the painting for comparison; C: the distribution of chromium, corresponding to viridian, chrome yellow, and zinc yellow, which also define negative spaces occupied by the former trees. The Eagle’s Nest, Forest of Fontainebleau (ca. 1837–67)

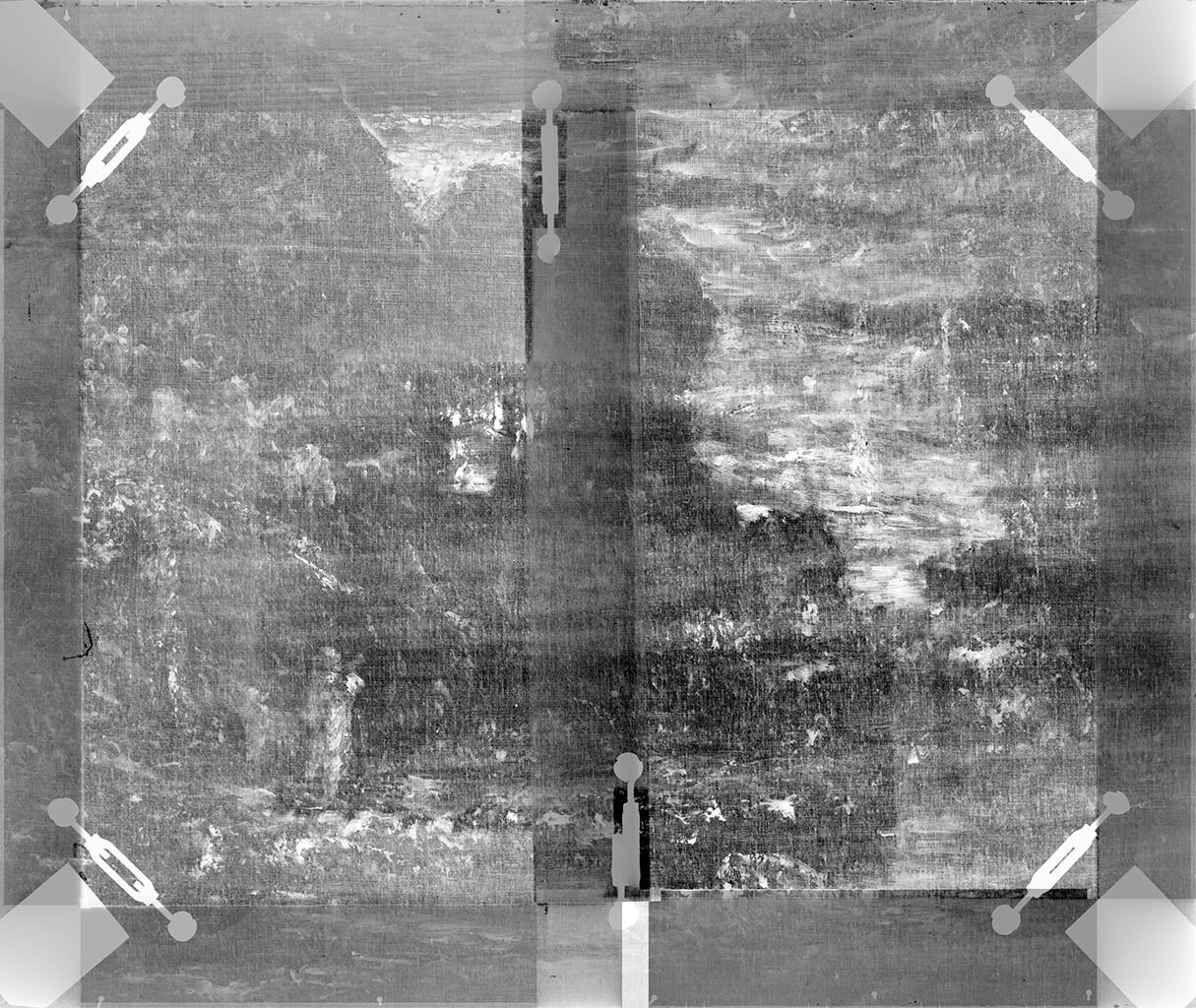

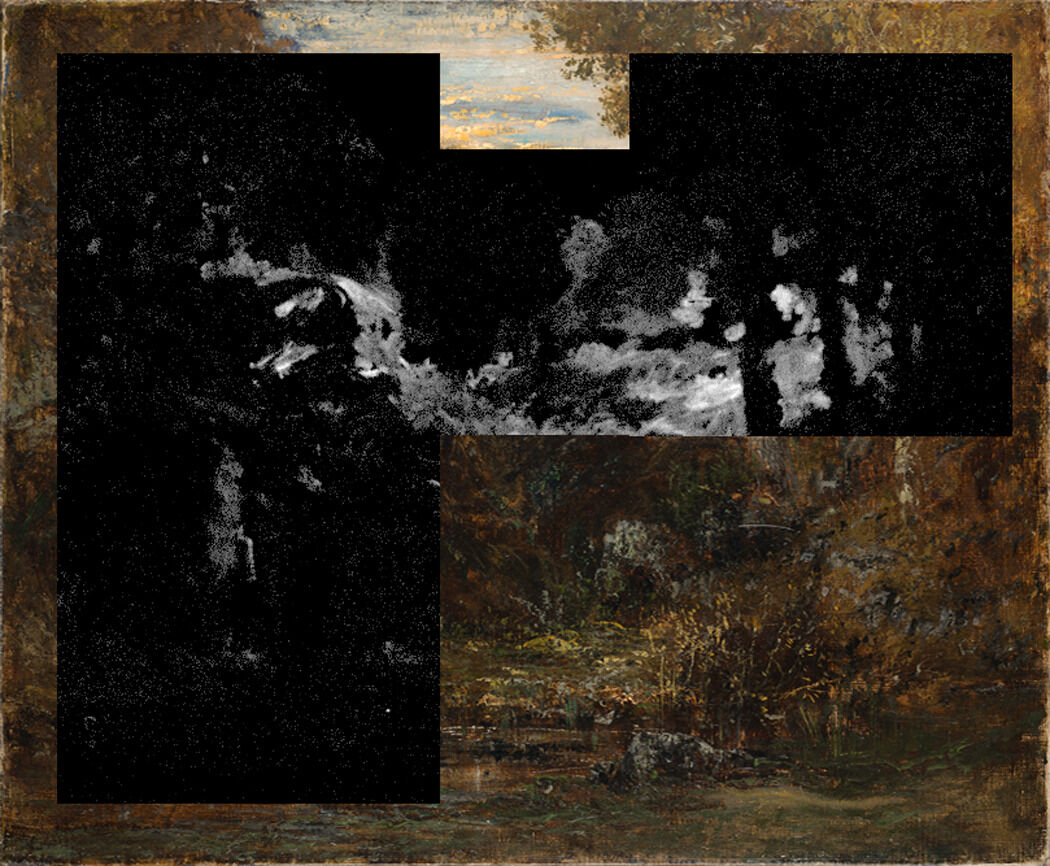

Both x-radiographyX-ray radiography (also referred to as x-radiography or radiography): Radiography is an examination tool analogous to the use of X-rays in medicine whereby denser components of a painted composition can be recorded as an inverted shadow image cast on film or a digital X-ray imaging plate from a source such as an X-ray tube. The method has been used for more than a century and is most effective with dense pigments incorporating metallic elements such as lead or zinc. It can reveal artist changes, underlying compositions, and information concerning the artwork’s construction and condition. The resulting image is called an x-radiograph or radiograph. It differs from the uses of X-ray spectrometry in being dependent on the density of the paint to absorb X-rays before they reach the film or image plate and being non-specific as to which elements are responsible for the resulting shadow image. and partial XRF elemental mapping (MA-XRF)X-ray fluorescence spectrometry elemental mapping (MA-XRF) or XRF elemental mapping: A non-destructive technique that entails collecting thousands of X-ray fluorescence spectra at regular intervals across a painting to build an alternate set of images depicting the locations and amounts of different elements. Although the information is fundamentally the same as measurements gathered from a single-point XRF, the graphical nature of the result is often a more powerful technique for understanding trends in an artist’s use of materials. The high number of spectra allows statistical manipulations of the elemental information to locate correlations between different pigments that would not be possible from a small number of tests. For example, the consistent occurrence of mercury along with chromium, and iron along with copper, could show that vermilion was used to mute the chrome green and red ocher was similarly employed in a mixture that includes emerald green. The resulting correlation maps then serve to show where the two cases occur in the composition. MA-XRF can also reveal preliminary paint applications that became covered as the composition was completed, thereby disclosing aspects of the painter’s method. reveal an underlying forest scene. Six tree trunks that were held in reserve on the left side are readily apparent in the arsenic, copper, and chromium maps (Fig. 17). These early trees were eventually covered by subsequent paint to depict the hillside and cattle, though the reserves for three of these initial tree trunks remain visible in the final painting. Bright yellow and green from the former tree branches are present beneath the cattle on the hilltop (center left), indicating that these compositional elements are mutually incompatible. Indeed, it is unclear whether cattle were ever portrayed in the original concept, as many of the underlying foreground shapes are indistinct. Rousseau made these compositional changes without first obscuring the lower landscape with a second ground layer. The barium map and x-radiograph reveal the initial placement of the sky, covering a much wider area that extended down to the center right (Figs. 18 and 19), although it is unclear if this relates to the first composition or an earlier stage of the second composition. Based on its location, this deeper swath of sky would have produced a strong focal point for either landscape, though it is absent in Rousseau’s final version.

Fig. 18. The distribution of zinc in areas mapped by MA-XRF, corresponding to the presence of zinc yellow and possibly to zinc white, The Eagle’s Nest, Forest of Fontainebleau (ca. 1837–67). A: Arrows mark a freely drawn “corkscrew” shape behind the tree at center right, which has no direct correlation in the final composition. B: visual appearance of the painting for comparison; C: the distribution of barium, showing a void space where the sky formerly extended much lower in an earlier composition.

Fig. 18. The distribution of zinc in areas mapped by MA-XRF, corresponding to the presence of zinc yellow and possibly to zinc white, The Eagle’s Nest, Forest of Fontainebleau (ca. 1837–67). A: Arrows mark a freely drawn “corkscrew” shape behind the tree at center right, which has no direct correlation in the final composition. B: visual appearance of the painting for comparison; C: the distribution of barium, showing a void space where the sky formerly extended much lower in an earlier composition.

Fig. 19. X-radiograph composite of The Eagle’s Nest, Forest of Fontainebleau (ca. 1837–67)

Fig. 19. X-radiograph composite of The Eagle’s Nest, Forest of Fontainebleau (ca. 1837–67)

Contemporaries described Rousseau’s lengthy revisions and struggle to release a painting from his studio to such an the extent that friends resorted to subterfuge to get works out of his hands.18Thomson, Barbizon School of Painters, 99. The substantial changes observed in the Nelson-Atkins painting suggest that the artist had difficulty resolving this first composition and perhaps returned to the unfinished work at a later date.19Rousseau is known to have worked up old studies. Ahead of the 1861 sale of his works at the Hôtel Drouot, Rousseau gathered twenty-five canvases from his reserve and spent an exhaustive five months in his Paris studio finishing them. Sensier, Souvenirs sur Théodore Rousseau, 256. Forest in Winter at Sunset (Fig. 4) is thought to have been in Rousseau’s possession for over twenty years and exhibits some technical similarities to the Nelson-Atkins painting: lack of a drawn sketch; varying colors of sauce; sgraffitosgraffito (pl: sgraffiti): An Italian term meaning “scratched,” in which a compositional design or decoration is created using a sharp tool to scrape into the wet medium (paint, plaster, glaze, slip, etc) and reveal contrasting underlying layers., scraping, and paint application most likely using his palette knife; and subtractive painting methods.20Hale, “Technical Study of A Forest in Winter at Sunset.”

Rousseau’s Palette

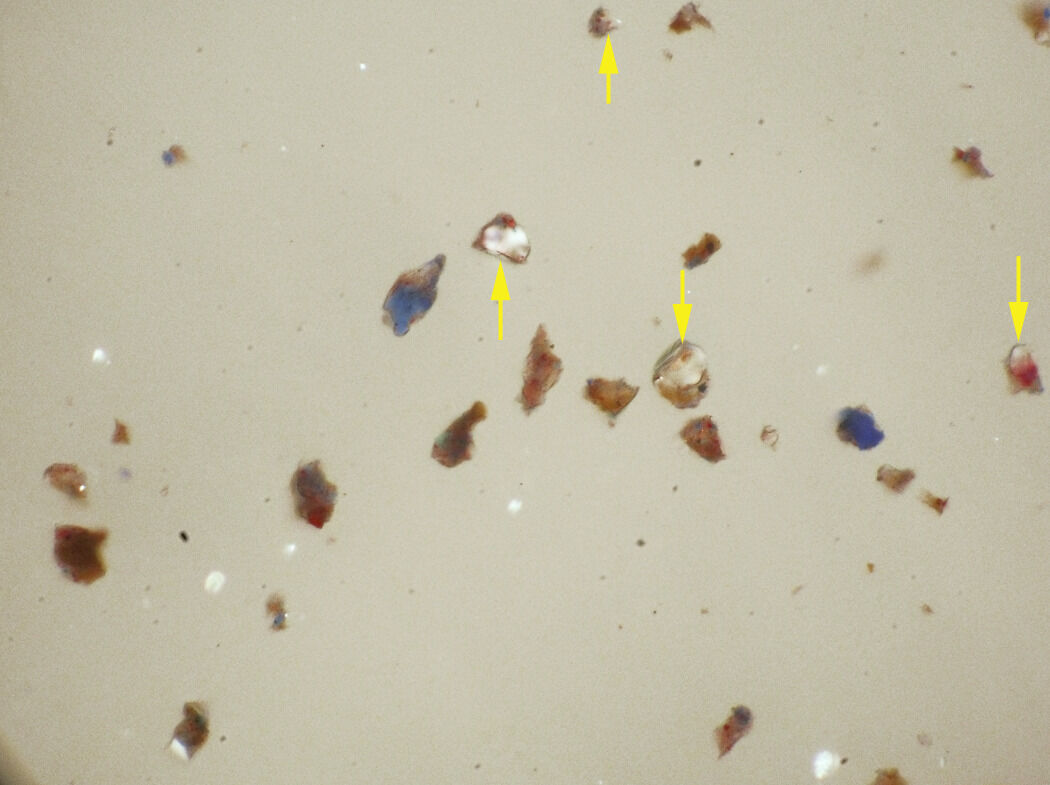

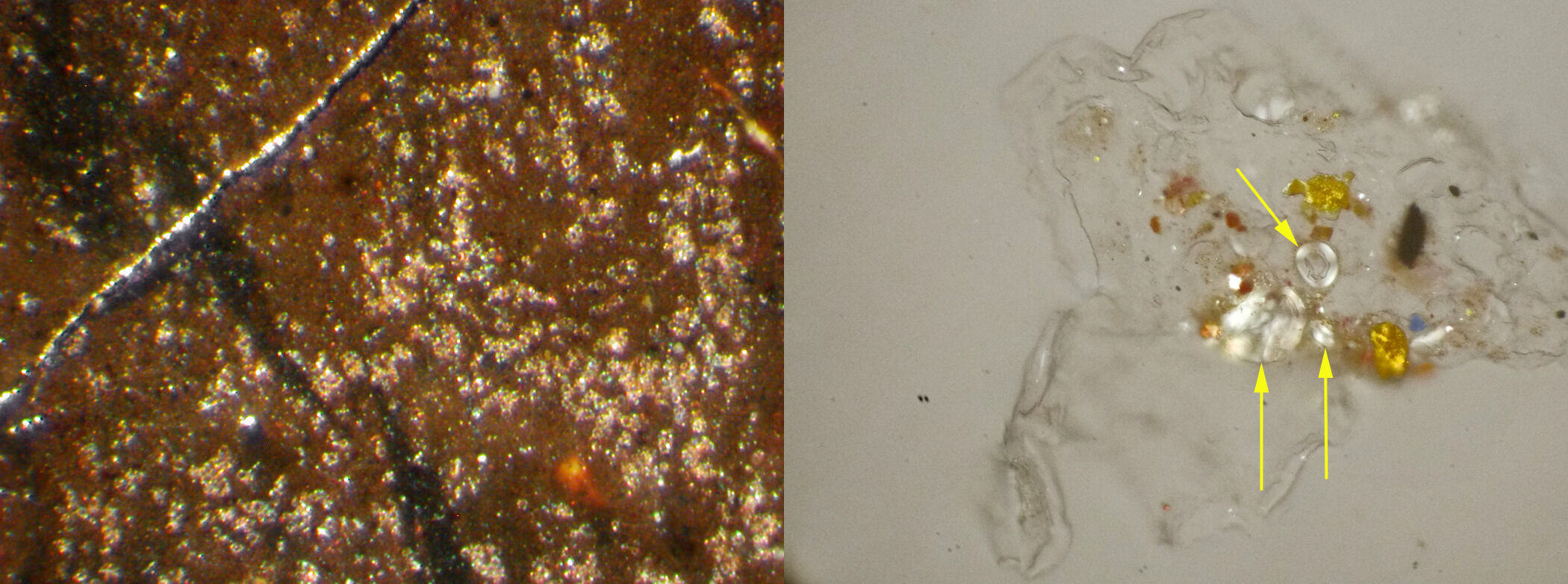

Identification of Rousseau’s palette was carried out by integrating the results of several complementary analytical methods. These involved the preparation of microscopic cross sections of paint that were studied by optical and scanning electron microscopy (SEM)scanning electron microscopy (SEM): Performed on a microsample of paint, the SEM provides a means of studying particle shapes beyond the magnification limits of the light microscope. This becomes increasingly important with the painting materials introduced in the early modern era, which are finer and more diverse than traditional artists’ materials. The SEM is routinely used in conjunction with an X-ray spectrometer, so that elemental identifications can be made selectively on the same minute scale as the electron beam producing the images. SEM methods are particularly valuable in studying unstable pigments, adverse interactions between incompatible pigments, and interactions between pigments and surrounding paint medium, all of which can have profound effects on the appearance of a painting., with elemental analyses of the layer components by X-ray spectrometryX-ray fluorescence spectrometry elemental mapping (MA-XRF) or XRF elemental mapping: A non-destructive technique that entails collecting thousands of X-ray fluorescence spectra at regular intervals across a painting to build an alternate set of images depicting the locations and amounts of different elements. Although the information is fundamentally the same as measurements gathered from a single-point XRF, the graphical nature of the result is often a more powerful technique for understanding trends in an artist’s use of materials. The high number of spectra allows statistical manipulations of the elemental information to locate correlations between different pigments that would not be possible from a small number of tests. For example, the consistent occurrence of mercury along with chromium, and iron along with copper, could show that vermilion was used to mute the chrome green and red ocher was similarly employed in a mixture that includes emerald green. The resulting correlation maps then serve to show where the two cases occur in the composition. MA-XRF can also reveal preliminary paint applications that became covered as the composition was completed, thereby disclosing aspects of the painter’s method.. The addition of ultraviolet fluorescence microscopyultraviolet (UV)-induced visible light fluorescence microscopy (of cross sections): A method used in limited cases with microsamples to determine the layering of paint applications. Differences in both pigmentation and formulation of the paint medium will influence the UV fluorescence behavior of the paint layers. for the study of dark paint strata was particularly beneficial to understanding Rousseau’s methods. Dispersed samples of pigment studied by polarized light microscopy (PLM)polarized light microscopy (PLM): A method used for the study and differentiation of pigments based on the optical properties of individual particles, including color, refractive index, birefringence, etc. PLM is particularly useful in identifying the presence of organic pigments such as indigo and Prussian blue, which often cannot be differentiated from paint medium in the scanning electron microscopy (SEM); differentiating synthetic pigments from their natural analogs by particle shape or the presence of extraneous mineral matter; and disclosing the presence of pigments with similar composition but differing color, such as red and yellow iron oxides. proved essential in differentiating organic components of the palette, locating and differentiating lake pigments, and disclosing instances of the darkening of paint medium.

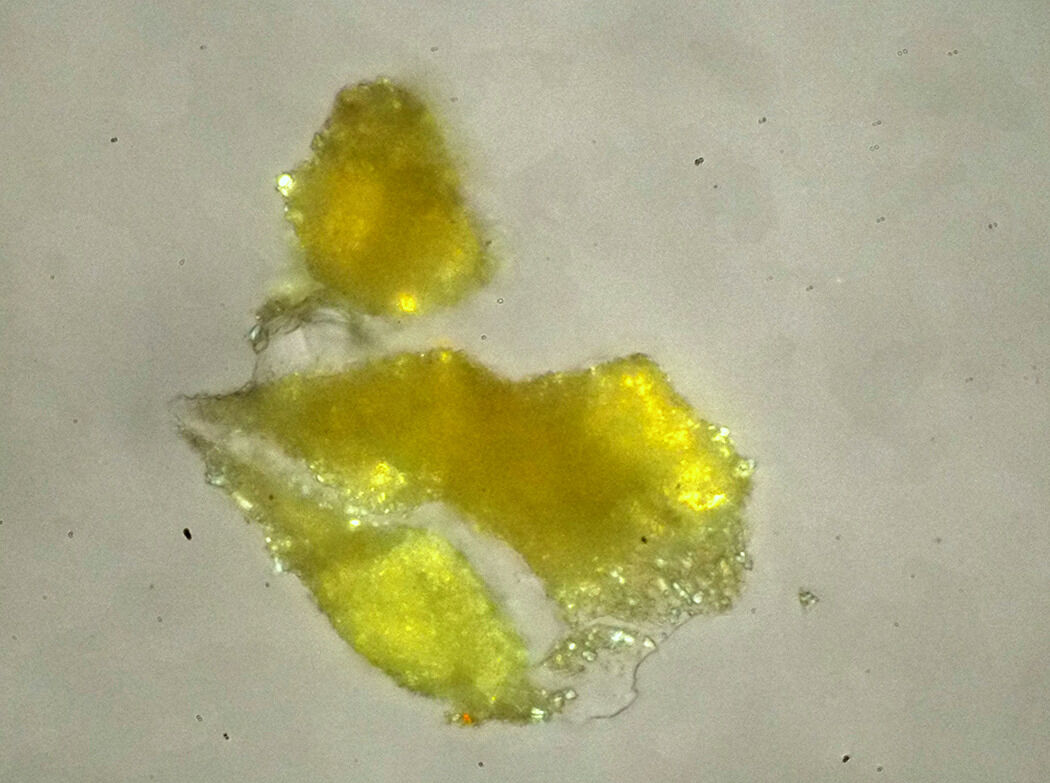

PLM revealed that starch was an additive for a tin-based deep red lake that was used for the ébauche (Fig. 20). Occasional instances of bright yellow seen in PLM that are not associated with well-defined particles indicate some use of a yellow lake. The most subtle distinction found in PLM, and one that could not be resolved by other techniques, involved the discovery of “mineral blue,” a pigment of widely varying composition based on the application of a blue organic color or dye to a colorless, inorganic substrate, such as white clay (Fig. 21). This most often involved Prussian blue, the saturation of which allowed it to be greatly diluted on a colorless filler while retaining a strong tinting capacity. Interestingly, in 1872, Rousseau’s biographer, Alfred Sensier, noted that Rousseau rarely used mineral blue, and his use of Prussian blue was even less frequent.21Sensier, Souvenirs sur Théodore Rousseau, 201.

The full palette consisted of lead white, bone or ivory black, vermilion, red lake, pink lake, red ocher, sienna, yellow ocher, lead chromate yellow, lead chromate orange, zinc potassium chromate yellow, cadmium yellow or orange, suspected yellow lake, viridian, copper acetoarsenite (emerald) green, cobalt blue aluminate, ultramarine blue (possibly in two varieties, pale and dark), mineral blue probably based on Prussian blue, and likely small amounts of pale smalt. Based on elemental mapping, zinc white is suspected as a component of the light blue-gray highlights of the tree trunks and rocks. However, it was not confirmed to be present in the available microsamples. Green earth may be present in mixtures that were too complex for its presence to be confirmed. Colorless minerals encountered in the paint included gypsum, calcium carbonate, dolomite, kaolin, quartz, and barite.

While the foregoing identifications of individual pigments required microanalysis of samples, the integration of this information in relation to Rousseau’s methods and compositional changes required the use of non-sampling instrumental methods to disclose how these materials were distributed in the composition. These results have also been applied to questions about the painting’s execution date and how much time may have passed before the forest scene was transformed into the current composition.

The landscape is thinly painted, based on the high amount of both visible light and infrared (IR) passing through the canvas when illuminated from the verso. Furthermore, in spite of its dark visual appearance, the paint layers are quite reflective at IR wavelengths. IR imaging at a variety of wavelengths differentiated passages that are pigmented with carbon black (in the form of bone or ivory black) from those in which dark colors have been achieved by blending highly saturated colors (Fig. 22). All parts of the painting except those with large amounts of bone or ivory black are highly reflective in the infrared, an outcome that is counterintuitive given the dark visual appearance of the painting. It is remarkable that the underlying left trees belonging to the earlier composition are readily discerned in elemental maps, yet not sufficiently clear in either IR imaging or radiography to have previously been recognized.

Potential Darkening of the Nelson-Atkins Landscape

The former connections between the dark landscape of The Eagle’s Nest (Fig. 6) and the 1830’s Jura landscapes, in particular the rapid darkening and deterioration of the Salon painting (Fig. 3), raised questions about how the Nelson-Atkins painting might have changed over time. Prior investigations of the Mesdag and Amiens paintings focused on a variety of phenomena leading to discoloration. Writers in the late nineteenth century attributed this type of darkening and distortions of the paint layers to bitumen, a form of natural petroleum tar that imparts a warm brown to oil paint, but which is very detrimental to its drying and subsequent stability. For these reasons, bitumen is usually accompanied by severe, disfiguring traction cracking, sometimes referred to as alligatoring or alligator skin.

In 2013, scientific studies of the Mesdag and Amiens paintings ruled out the use of bitumen. Instead, this research produced evidence for instability of the layers due to the use of paints whose oil medium was slow to dry. Rousseau’s haste in the painting process led to improper drying of lower layers before additional paint was added. The dramatic darkening and diminished legibility that occurred involved aging discoloration of the oil medium and, most importantly, deterioration of copper acetoarsenite (“emerald”) green, involving the release of arsenic and adverse interactions with other pigments.22Katrien Keune, Jaap J. Boon, René Boitelle, and Yoshiko Shimazu, “Degradation of Emerald Green in Oil Paint and its Contribution to the Rapid Change in Colour of the Descente des Vaches (1834–35) Painted by Théodore Rousseau,” Studies in Conservation 58, no. 3 (2013): 199–210., 23Yoshiko Shimazu, “Chemical Changes and Decrease of Light Reflected in La Descente des Vaches by Théodore Rousseau (The Mesdag Collection, HMW286, 1834–35),” in “Chemical and Optical Aspects of Appearance Changes in Oil Paintings from the 19th and early 20th century” (MA thesis, University of Amsterdam, 2015), 121–76, figs. 5.2–5.6., 24Katrien Keune, Jennifer Mass, Apurva Mehta, Jonathan Church, and Florian Meirer, “Analytical Imaging Studies of the Migration of Degraded Orpiment, Realgar, and Emerald Green Pigments in Historic Paintings and Related Conservation Issues,” Heritage Science 4 (2016): 10., 25Boitelle et al, “Descending into the Details of Th. Rousseau’s ‘La descente des vaches,’” 27–31.

Comparisons with this prior research confirmed many palette similarities to the Nelson-Atkins painting. However, the absence of traction cracking or distortions combined with the results of our pigment analyses suggest that bitumen was not used. Emerald green was used prominently along with viridian to depict green foliage in this painting. Analysis shows that there are some instances of the presence of arsenic disassociated from copper that could be evidence of the release and migration of this element from emerald green. However, at the particulate level, there were no darkened alteration products found to have a clear association with this unstable pigment.

Elemental mapping by X-ray fluorescence spectrometry was effective in clarifying aspects of the dark composition where the dark scene and color alone are insufficient to discern details. Many of the pigments in the palette contain elements that were effectively mapped, although the simultaneous presence of the same elements in multiple pigments complicates interpretation of the results. Chromium occurs in five different pigments, for example. Iron occurs in at least four. The correlation between calcium and phosphorus helps to understand the placement of bone or ivory black in the dark composition, in which truly black pigments are difficult to discern visually. The placement of vermilion is readily seen from the map of mercury and is thereby distinguished from iron-based reds and reds relying on lake pigments. Cadmium, rarely encountered in concentrated form in the samples, is shown by MA-XRF to be widespread in mixtures, although seldom used alone. The presence of tin in the red lake used for the ébauche allows dark passages involving this pigment to be differentiated from other dark areas (Fig. 23).

However, certain important pigments known to be present cannot be mapped. These include ultramarine (all of whose elements are too light for their weak X-ray emissions to reach the detector), Prussian blue (whose iron content is lost among the iron-containing earth pigments), and lakes based solely on organic pigments and alumina. Cobalt, which exists in relatively low amounts in cobalt blue, is not distinctly seen in the maps when the pigment is diluted in mixtures. Consequently, understanding the relative roles of the two blue pigments, ultramarine and cobalt blue, in pale mixtures requires direct analysis of samples.

The distribution of zinc and the form(s) in which it occurs is important considering the compositional change and a possible date for that change. Maps of copper and arsenic (always present together in emerald green) and chromium (in the green pigment viridian but also present in yellows) show clearly defined negative spaces around the large trees on the left, where the steep hillside and descending cattle have been placed (Fig. 17). On the opposite side of the composition, elemental mapping shows a swirling application of a zinc compound in the region behind the tall tree in the center right. This is the same area where the map for barium shows the sky to have formerly been depicted in the region of ascending terrain and trees. The zinc application exceeds the outline of the tree and lacks the definition of foliage elsewhere in the painting (Fig. 18). It is unclear whether this application was a rapid, first-stage placeholder for the sky or a remnant of some other change that occurred when the trees were eliminated on the left. The only likely form for this zinc in the mid-nineteenth century is either in zinc white (zinc oxide) or zinc yellow (zinc potassium chromate). Zinc white was never confirmed in single-particle pigment analyses. However, it may be present, since elemental mapping suggests that it could be a component of the pale blue-gray used for highlights on tree trunks and in the herdsman’s clothing (Fig. 18A). As discussed in greater detail below, zinc yellow has been confirmed in many locations in the painting.

Due to a lack of samples that clearly belonged to the first composition, it was not possible to determine if zinc yellow was a component of that first phase. It might seem that the MA-XRF distribution of zinc yellow would be straightforward from the simultaneous presence of easily mapped zinc, potassium, and chromium, in the fixed proportions in which they occur in zinc yellow. In spite of complex behavior showing three distinct “populations” in which zinc and chromium were correlated, these populations did not show direct correlation to potassium, the third essential element of the zinc yellow pigment. This difficulty is probably due to the many other pigments in which chromium occurs in this palette as well as the fact that potassium is simultaneously present in earth colors.

Attempts to relate specific pigments to the two phases of the composition were unsuccessful. The same materials appear to be shared in both phases. However, the scraping of the paint surface that has been noted may have diminished some features of the forest scene.

Execution Date of The Eagle’s Nest, Forest of Fontainebleau formerly titled Cows Descending the Hillside at Sunset

Under its previous title, when the Nelson-Atkins painting was still considered a variant of the Mesdag Salon painting of 1834–35 (Fig. 3) and before the underlying composition was known, two separate date ranges had been proposed: ca. 1837–40 and ca. 1860–65. Following the discovery of the painted location through the 1880 etching by Théophile-Narcisse Chauvel (Fig. 5),26See accompanying catalogue essay by Simon Kelly. the date of The Eagle’s Nest remained an important question. The late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries marked a turning point in both chemical achievements and manufacturing innovation that led to improved artist pigments that were often less expensive than traditional colors. Given the limitations of artist pigments up to this point, particularly for landscape painters who were mixing yellow and blue paint to create green colors, the Barbizon artists were enthusiastic adopters of these bright modern pigments. The dates of introduction for three pigments employed in the Nelson-Atkins painting, considered in the context of contemporary accounts of Rousseau’s early acquisition of new pigment types, now argues for a wider date range. Future work to better understand pigments associated with the first composition may allow for greater refinement.

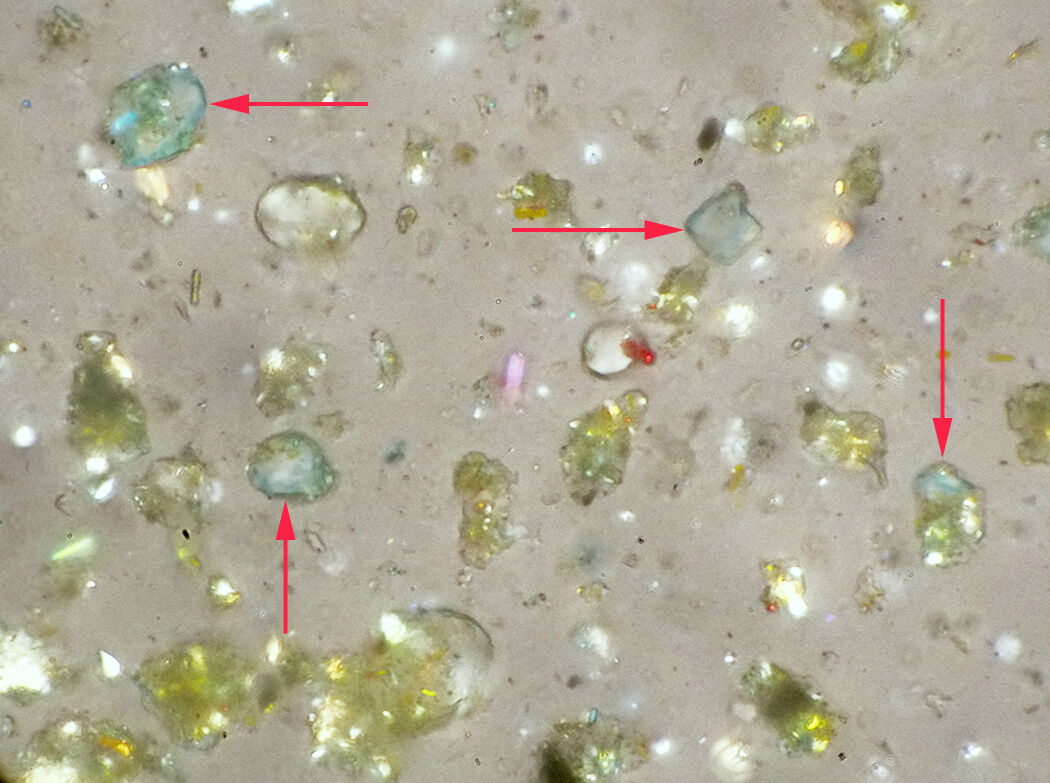

The Eagle’s Nest incorporates pigments based on the elements cadmium and chromium that were newly discovered at the beginning of the nineteenth century.27Louis-Nicholas Vauquelin discovered chromium in 1797. Friedrich Stromeyer discovered cadmium in 1817. Zinc yellow (zinc potassium chromate) is thought to have been synthesized in 1809 but not to have been commercialized until 1850.28Hermann Kuhn and Mary Curran, “Chrome Yellow and Other Chromate Pigments, B Zinc Yellow,” in Artist’s Pigments, ed. Robert L. Feller (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1986), 1:201., 29David A. Crown, The Forensic Examination of Paints and Pigments (Springfield: Charles C. Thomas, 1968), 38. Cadmium yellow (cadmium sulfide), although mentioned by Jean-François-Lénora Mérimée in 1830,30Jean-François-Léonor Mérrimée, De la peinture à l’huile (Paris: Huzard, 1830), 118–19. was synthesized in 1817 and not commercialized until 1846.31Inge Fiedler and Michael A. Bayard, “Cadmium Yellows, Oranges and Reds,” in Feller, Artist’s Pigments, 1:67., 32Crown, Forensic Examination of Paints and Pigments, 34. Viridian is said to have been “introduced” in 1838 but patented only in 1859 and marketed as an artist’s color in 1862.33Crown, Forensic Examination of Paints and Pigments, 47., 34Richard Newman, “Chrome Oxide Greens,” in Feller, Artist’s Pigments, ed. Elizabeth West Fitzhugh (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1997), 3:274–75. This is prima facie evidence supporting a later date of the painting, since neither yellow was thought to be in commercial use during the earlier of the previously proposed years. In 1833, Louis-Charles Arsenne remarked on how promising viridian would be to the landscapist when it became available,35Louis-Charles Arsenne, Manuel du Peintre et du Sculpteur: Ouvrage dans lequel on traite de la Philosophie de l’Art et des moyens pratiques (Paris: Roret, 1833), 2:248. Cited in Andreas Burmester and Claudia Denk, “Blue, Yellow, and Green on the Barbizon Palette,” Zeitschrift für Kunsttechnologie und Konservierung 1, no. 1 (1999): 85. and Sensier wrote in 1872 that Rousseau was using viridian in the late 1830s.36Sensier, Souvenirs sur Théodore Rousseau, 97. Early use of a single, known, but as yet rarely available pigment could be dismissed as an outlier, whereas the simultaneous use of three different pigments in the same painting, prior to their dates of commercial introduction, would be much less likely and could argue for a date later in his career. However, the Barbizon painters had immediate access to new pigments on the Parisian market, and Rousseau was among the first to adopt them into his painting practice.37Burmester and Denk, “Blue, Yellow, and Green on the Barbizon Palette,” 82. To underscore this possibility, one can look to Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796–1875), who was also keen to incorporate these vibrant new colors. Analysis has shown that viridian is present in The Roman Campagna, with the Claudian Aqueduct (National Gallery, London, NG 3285), which Corot completed around 1826.38Sarah Herring, The Nineteenth Century French Paintings, vol. 1, The Barbizon School (London: National Gallery Company Limited, 2019), 34–35, 70–72.

Meanwhile, zinc yellow was never a popular pigment for oil painting, and few identifications in dated works exist. It is also unlikely to have been recognized in mixtures in cases where elemental analysis had not been undertaken at the single particle level. Its color and particle morphology are similar to those of a light chrome yellow (lead chromate), and it would be difficult to recognize zinc yellow through PLM study alone (Fig. 24).

The combination of numerous factors—the possibility of Rousseau’s early acquisition of certain pigments, comparisons in technique between this work and his earlier paintings, the presence of two compositions, the use of mid-1840s yellow pigments during the second composition, and his tendency to hold onto paintings for lengthy periods of time—have led to the date range of ca. 1837–67 presented in this catalogue. As additional works are studied by more sophisticated techniques, greater confidence in the dating implications of pigments employed for this painting should become possible.

The studies of deterioration phenomena affecting the Mesdag and Amiens versions necessarily involved thorough characterization of both palettes, providing the authors with an unusually complete body of comparative information. Cross sections illustrated in those studies show greater degrees of distortion and instability in the paints and often contain more numerous layers. Fifteen layers are attributed to one sample in the Mesdag Salon painting, whereas the Nelson-Atkins samples never exceeded half that. Nonetheless, there is a high degree of commonality in the pigments of all three paintings and the roles in which they were used. The ébauche layer in all three paintings, for example, employs a red lake based on tin and contains starch. The paintings all employ both cobalt blue and ultramarine in combination with each other as well as Prussian blue, although in the Nelson-Atkins case the “mineral blue” variety of stained earth is used. They all employ emerald green, chrome yellow, ocher, and vermilion.39Slight differences among the findings by different researchers may be influenced by the different methods available to them. With the use of mass spectrometry, Cassel earth and “mummy,” two transparent brown pigments based on degraded plant matter, were found to be present in the Mesdag and Amiens paintings. Yellow lake appears to have played a bigger role in those paintings as well, but the authors had better means of detecting it. Where Rousseau’s palette for the Nelson-Atkins painting differs is precisely in those materials that suggest it belongs to a later date: zinc yellow, viridian, and cadmium yellow. Zinc white, whose sparing use is implied by the MA-XRF results, although not confirmed by an independent method, is another instance of a material absent from the Mesdag and Amiens paintings that would scarcely have been in use at the time of their execution in the 1830s. It was commercialized shortly thereafter and readily available by 1860.

The authors anticipate further work to distinguish material differences during the evolution of the Nelson-Atkins painting. Acquiring more accurate dating of the phases of the painting may deepen our understanding of Rousseau’s often lengthy working process and potentially discern his motivations for changing the composition. Future study should also yield important comparative information in relation to other Rousseau works and his Barbizon contemporaries.

Condition of The Eagle’s Nest