![]()

Edouard Manet, White Lilacs in a Crystal Vase, ca. 1882

| Artist | Edouard Manet, French, 1832–83 |

| Title | White Lilacs in a Crystal Vase |

| Object Date | ca. 1882 |

| Alternate and Variant Titles | Lilas blancs dans un vase de cristal |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (Unframed) | 22 1/8 x 13 3/4 in. (56.2 x 34.9 cm) |

| Credit Line | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Gift of Henry W. and Marion H. Bloch, 2015.13.12 |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Mary Frances Ivey, “Edouard Manet, White Lilacs in a Crystal Vase, ca. 1882,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.526.5407.

MLA:

Ivey, Mary Frances. “Edouard Manet, White Lilacs in a Crystal Vase, ca. 1882,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.526.5407.

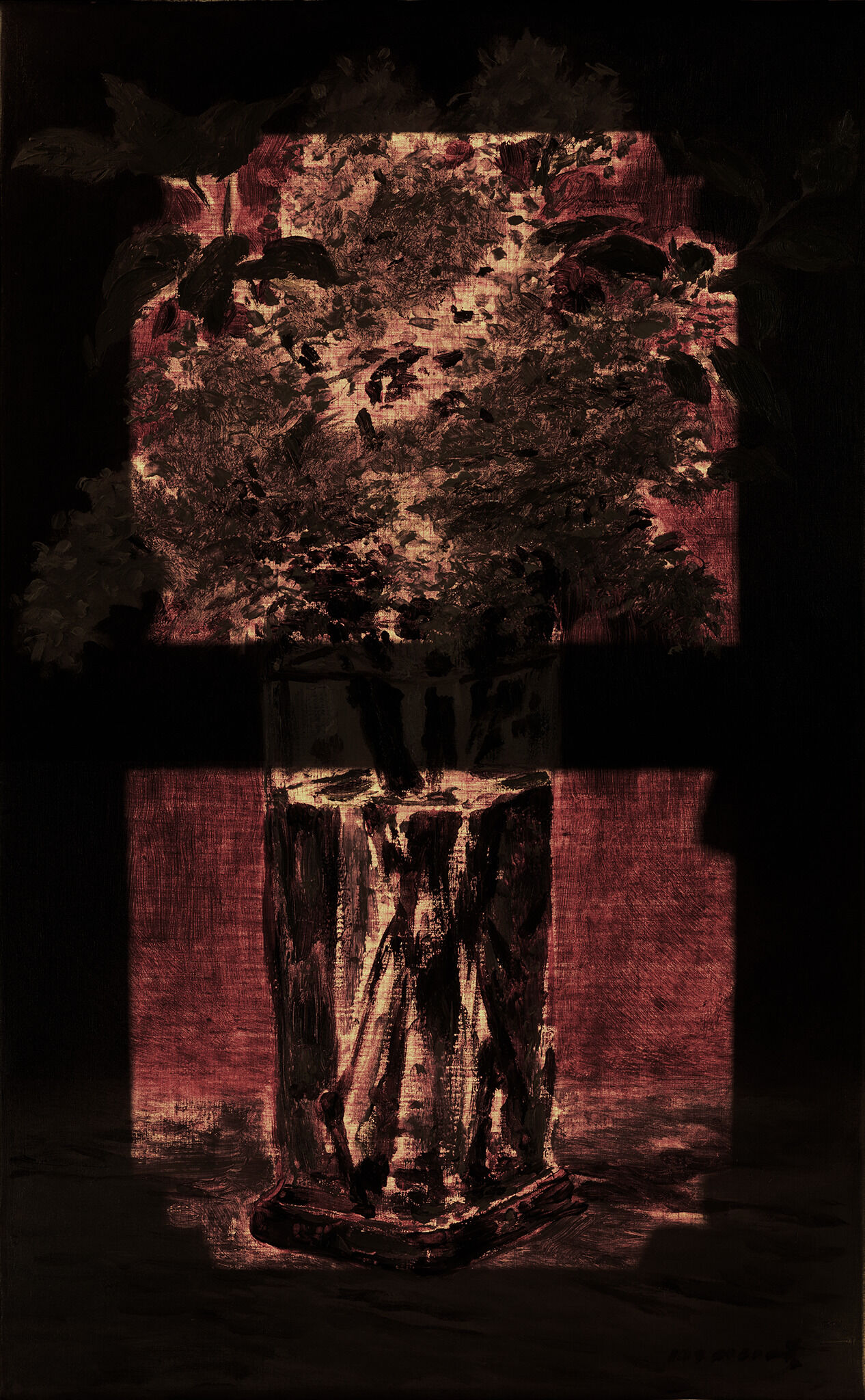

Edouard Manet presents a lively flower arrangement before a dark brown background. Tendrils of white, gray, and green blooms stand, stretch, and spill out of a rectilinear glass. Olive-colored leaves poke out from behind the flowers like plumes from a hat, filling the top half of the canvas with a symmetrical bouquet. Below the blossoms, against the stark surroundings, sketchy strokes of blue, brown, white, and gold form a slender vase, fine details on the surface of the crystal, leggy stems, and refracted reflections in the water. White Lilacs is one of at least twenty tightly cropped still lifes that Manet painted in the last two years of his life. These works represent posies that the convalescent artist received from loved ones during an ultimately fatal bout of illness, and they comprise most of his artistic production in those final months of his life.1For more on Manet’s late work, including his watercolors, see Carol Armstrong’s essay, “Manet’s Little Nothings,” in Scott Allan, Emily A. Beeny, and Gloria Groom, eds., Manet and Modern Beauty: The Artist’s Late Years, exh. cat. (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2019), 113–28. He had been suffering from complications of syphilis and died on April 30, 1883, a few days after the amputation of one of his legs. As Manet’s mobility grew progressively limited throughout this period, smaller-scale subjects were more manageable. These floral gifts provided him with lightweight, portable “models” that held their pose, if only for a day or so.

Manet, typically a painter of portraits and scenes of modern life, had focused on still lifes in one previous body of work, in the 1860s. That imagery ranges from succulent fish, fruit, ham, and close-ups of glistening brioches to cut peonies lying on dark surfaces and game animals hanging by their feet.2Marni Reva Kessler examined representations of food in the work of Manet—as well as Gustave Caillebotte (1819–77) and Edgar Degas (1834–1917)—in Kessler, Discomfort Food: The Culinary Imagination in Late Nineteenth-Century French Art (Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press, 2021). In these earlier pictures, he selected plush rosette forms, heavy with petals, and he splayed them out sideways and upside down on tabletops. His later floral still lifes, by contrast, feature mixed sprays set upright in their vases atop marble slabs; the dahlias, chrysanthemums, cabbage-like rosebuds, and clusters of tiny lilac blooms comprise an array of shapes and structures.3Manet had an enthusiastic buyer for the 1880s flower paintings in Eugène Pertuiset (1833–1909), a contemporary society figure and lion hunter, who acquired more than a dozen of Manet’s food and flower still lifes, including White Lilacs. See Pertuiset, Les aventures d’un chasseur de lions (Paris: M. Dreyfous, 1878), and “pCatalogue of the Exhibition,” in Allan et al., Manet and Modern Beauty: The Artist’s Late Years, 305. Although some of the paintings probably represent the same arrangement, he articulated distinct boughs, hues, and textures differently in each picture, perhaps by rotating the vases and repositioning the flowers to achieve new compositions between painting sessions. In this way, he imbues each fan of flowers and their solitary vases with a sense of individuality.

Until the 2019 exhibition Manet and Modern Beauty: The Artist’s Late Years, organized by the Art Institute of Chicago and the J. Paul Getty Museum, Manet’s late flower pictures mostly had been considered a sort of coda to his corpus that bears little relationship to the rest of his oeuvre.4Many Manet scholars mention the late flower pictures but seldom in relation to his figure paintings. For more on the 1880s flower pictures as a group, see Armstrong, “Manet’s Little Nothings,” and Bridget Alsdorf, “Manet’s Fleurs du mal,” in Manet and Modern Beauty: The Artist’s Late Years, 113–28, 129–146; Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 34–37; Robert Gordon and Andrew Forge, The Last Flowers of Manet, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1986); Stéphane Guégan, ed., Manet: The Man Who Invented Modernity (Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 2011), 239–40; and George L. Mauner, Manet: The Still-Life Paintings (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2000), 144–51. In the accompanying catalogue, the authors contextualize the floral paintings of the 1880s (including the Nelson-Atkins White Lilacs) in relation to Manet’s abiding interest in fashion, beauty, and modernity by firmly connecting the late 1870s and early 1880s to Manet’s prior life and work. I propose that these floral offerings from family and friends are akin to live models brought to his sickbed studio.5Manet resided outside of Paris (in Bellevue and in Rueil) off and on between 1880 and 1883 to seek medical treatment, sunshine, and fresh air during this period of serious illness. Their figural qualities—fleshy blossoms like skin, stalks and stems that resemble gesturing limbs, and containers as varied as physiques—allowed Manet to continue to center the human body in these later paintings, as he had throughout his career.

Fig. 2. Edouard Manet, Branch of Peonies and Pruning Shears, 1864, oil on canvas, 11 13/16 x 18 5/16 in. (30 x 46.5 cm), Musée d’Orsay, Paris, Bequest of comte Isaac de Camondo, RF 1995

Fig. 2. Edouard Manet, Branch of Peonies and Pruning Shears, 1864, oil on canvas, 11 13/16 x 18 5/16 in. (30 x 46.5 cm), Musée d’Orsay, Paris, Bequest of comte Isaac de Camondo, RF 1995

Fig. 3. Edouard Manet, The Dead Toreador, ca. 1864, oil on canvas, 29 7/8 x 60 3/8 in. (75.9 x 153.3 cm), National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Widener Collection, 1942.9.40

Fig. 3. Edouard Manet, The Dead Toreador, ca. 1864, oil on canvas, 29 7/8 x 60 3/8 in. (75.9 x 153.3 cm), National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Widener Collection, 1942.9.40

Notes

-

For more on Manet’s late work, including his watercolors, see Carol Armstrong’s essay, “Manet’s Little Nothings,” in Scott Allan, Emily A. Beeny, and Gloria Groom, eds., Manet and Modern Beauty: The Artist’s Late Years, exh. cat. (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2019), 113–28.

-

Marni Reva Kessler examined representations of food in the work of Manet—as well as Gustave Caillebotte (1819–77) and Edgar Degas (1834–1917)—in Kessler, Discomfort Food: The Culinary Imagination in Late Nineteenth-Century French Art (Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press, 2021).

-

Manet had an enthusiastic buyer for the 1880s flower paintings in Eugène Pertuiset (1833–1909), a contemporary society figure and lion hunter, who acquired more than a dozen of Manet’s food and flower still lifes, including White Lilacs. See Pertuiset, Les aventures d’un chasseur de lions (Paris: M. Dreyfous, 1878), and “Catalogue of the Exhibition,” in Allan et al., Manet and Modern Beauty: The Artist’s Late Years, 305.

-

Many Manet scholars mention the late flower pictures but seldom in relation to his figure paintings. For more on the 1880s flower pictures as a group, see Armstrong, “Manet’s Little Nothings,” and Bridget Alsdorf, “Manet’s Fleurs du mal,” in Manet and Modern Beauty: The Artist’s Late Years, 113–28, 129–146; Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 34–37; Robert Gordon and Andrew Forge, The Last Flowers of Manet, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1986); Stéphane Guégan, ed., Manet: The Man Who Invented Modernity (Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 2011), 239–40; and George L. Mauner, Manet: The Still-Life Paintings (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2000), 144–51.

-

Manet resided outside of Paris (in Bellevue and in Rueil) off and on between 1880 and 1883 to seek medical treatment, sunshine, and fresh air during this period of serious illness.

-

Alsdorf discussed Manet’s familiarity with the ways that the two poets (particularly Baudelaire) explored “negative aesthetics” in their interconnected conceptions of beauty, death, and floral imagery in “Manet’s Fleurs du mal,” 129.

-

Baudelaire, 66 Translations from Charles Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du Mal, trans. James McGowan (Peoria, IL: Spoon River Poetry Press, 1985), 30–31.

-

Baudelaire, 66 Translations, 12–13.

-

Mallarmé, “Sur les bois oubliés,” cited in James H. Rubin, Manet’s Silence and the Poetics of Bouquets (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994), 159.

-

Both paintings feature pruning shears, the instrument of the flowers’ demise, in vulnerable positions that echo the flowers’ poses. Next to the red and pink peonies, the blades and handles are spread-eagled; by the white peonies, the oval form of the closed blades resembles a head lying on the ground. For more on the affinities between dead animals and cut flowers in Manet’s still lifes, see Linda Nochlin, “More Beautiful than a Beautiful Thing: The Body, Old Age, Ruin, and Death,” Bathers, Bodies, Beauty: The Visceral Eye (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2006): 253–92.

-

Manet rendered dead human and animal bodies in positions similar to the 1860s peonies multiple times, as, for example, in The Suicide (1877) and Dead Eagle Owl (1881; both in the Foundation E.G. Bührle Collection) and in Dead Christ with the Angels (1864; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York).

-

Other works that feature death and the postmortem figure include The Dead Christ with the Angels (1864), The Funeral (ca. 1867), and Civil War (1871–73; all in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art); The Suicide (1877); The Execution of Emperor Maximilian (ca. 1867–68; National Gallery, London); and, according to many contemporary critics, Olympia (1864; Musée d’Orsay, Paris). Rubin has related several of these works to Second Empire politics and paintings of dead heroes by Honoré Daumier (1808–79), Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863), and Francisco de Goya (Spanish, 1746–1828). See Rubin’s essay, “Manet’s Heroic Corpses and the Politics of Their Time,” in Therese Dolan, ed., Perspectives on Manet (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2012), 119–38.

Dead animals also appear in Manet’s The Rabbit (1866; Angladon Museum—Collection Jacques Doucet, Avignon, France); Dead Eagle Owl (1881) and Mr. Eugène Pertuiset, the Lion Hunter (1881; both Museu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand); The Ham (ca. 1875–78; The Burrell Collection, Glasgow); and Oysters (1862; National Gallery, London).

-

Theodore Reff contextualizes Manet’s Dead Toreador with the other fragments from Episode from a Bullfight and the artist’s interest in Spanish art and culture, including the work of Diego Velázquez (1599–1660) and Goya. Reff, Manet’s Incident in a Bullfight (New York: Frick Collection, 2005).

-

Beeny probes Manet’s interest in representing corpses and corpse-like bodies by relating his submissions to the Salon of 1864 to the city morgue, which opened to the public that same year, in Beeny, “Christ and the Angels: Manet, the Morgue, and the Death of History Painting?,” Representations 122, no. 1 (Spring 2013): 51–82.

-

That Goya, one of the artists who fascinated Manet most, also represented death throughout his career is no coincidence. Manet’s Execution of Emperor Maximilian is one prime example of his familiarity with and interest in Goya’s imagery of death and dying. See John J. Ciofalo, “Unveiling Goya’s Rape of Galatea,” Art History 18, no. 4 (December 1995): 477–98; and John J. Ciofalo, The Self-Portraits of Francisco Goya (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2011).

-

Manet worked with his loved ones and favorite models repeatedly, including, among others, Jeanne Demarsy, Méry Laurent, Léon Leenhoff, Suzanne Manet, Victorine Meurent, and Berthe Morisot. For more, see Manet and Modern Beauty: The Artist’s Late Years; Armstrong, Manet Manette (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002); Tamar Garb, “Framing Femininity in Manet’s Portrait of Mlle E.G.,” in The Painted Face: Portraits of Women in France 1814–1914 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007), 58–99, 255–259; Kessler, “Unmasking Manet’s Morisot, or Veiling Subjectivity,” Sheer Presence: The Veil in Manet’s Paris (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006), 62–93, 161–165; and Susan Sidlauskas, “The Spectacle of the Face: Manet’s Portrait of Victorine Meurent,” in Therese Dolan, ed., Perspectives on Manet (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2012), 29–48.

-

The artist described his loneliness, his longing for the sights and sounds of Paris, and his desire to work at his usual rhythm in several letters from the countryside. He wrote to Méry Laurent: “I make the most of sunny spells by walking in the garden, but to distract myself and even to feel really well, I’d have to be working.” Cited in Samuel Rodary’s essay, “Édouard Manet: A Selection of Letters, 1878–83,” in Manet and Modern Beauty: The Artist’s Late Years, 180.

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Diana M. Jaskierny, “Edouard Manet, White Lilacs in a Crystal Vase, ca. 1882,” technical entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.526.2088.

MLA:

Jaskierny, Diana M. “Edouard Manet, White Lilacs in a Crystal Vase, ca. 1882,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.526.2088.

Fig. 7. Detail of the lower edge on White Lilacs in a Crystal Vase (ca. 1882), illustrating the exposed ground at bottom with white paint above

Fig. 7. Detail of the lower edge on White Lilacs in a Crystal Vase (ca. 1882), illustrating the exposed ground at bottom with white paint above

Fig. 8. Photomicrograph of paint extending over the exposed ground on the lower edge of White Lilacs in a Crystal Vase (ca. 1882)

Fig. 8. Photomicrograph of paint extending over the exposed ground on the lower edge of White Lilacs in a Crystal Vase (ca. 1882)

Fig. 9. Transmitted light image of White Lilacs in a Crystal Vase (ca. 1882), illustrating the extent of unpainted ground

Fig. 9. Transmitted light image of White Lilacs in a Crystal Vase (ca. 1882), illustrating the extent of unpainted ground

Fig. 10. Detail of the vase in White Lilacs in a Crystal Vase (ca. 1882), revealing the use of exposed ground and minimal paint in the top portion of the vase

Fig. 10. Detail of the vase in White Lilacs in a Crystal Vase (ca. 1882), revealing the use of exposed ground and minimal paint in the top portion of the vase

Fig. 11. Photomicrographs of underpainting found in White Lilacs in a Crystal Vase (ca. 1882), with the top image being the upper lip of the vase and the bottom image being the lower edge of the vase. Black arrows point to the brown outlines.

Fig. 11. Photomicrographs of underpainting found in White Lilacs in a Crystal Vase (ca. 1882), with the top image being the upper lip of the vase and the bottom image being the lower edge of the vase. Black arrows point to the brown outlines.

Fig. 12. Photomicrograph of the lower brown paint layer extending beneath a leaf, White Lilacs in a Crystal Vase (ca. 1882)

Fig. 12. Photomicrograph of the lower brown paint layer extending beneath a leaf, White Lilacs in a Crystal Vase (ca. 1882)

Fig. 13. Photomicrograph within the leaves of White Lilacs in a Crystal Vase (ca. 1882). In the center of this image, a white arrow points to the cooler light green paint, which may relate to the original placement of the leaves.

Fig. 13. Photomicrograph within the leaves of White Lilacs in a Crystal Vase (ca. 1882). In the center of this image, a white arrow points to the cooler light green paint, which may relate to the original placement of the leaves.

Fig. 14. Detail of the dabs of paint used to form the blossoms on the left side of White Lilacs in a Crystal Vase (ca. 1882)

Fig. 14. Detail of the dabs of paint used to form the blossoms on the left side of White Lilacs in a Crystal Vase (ca. 1882)

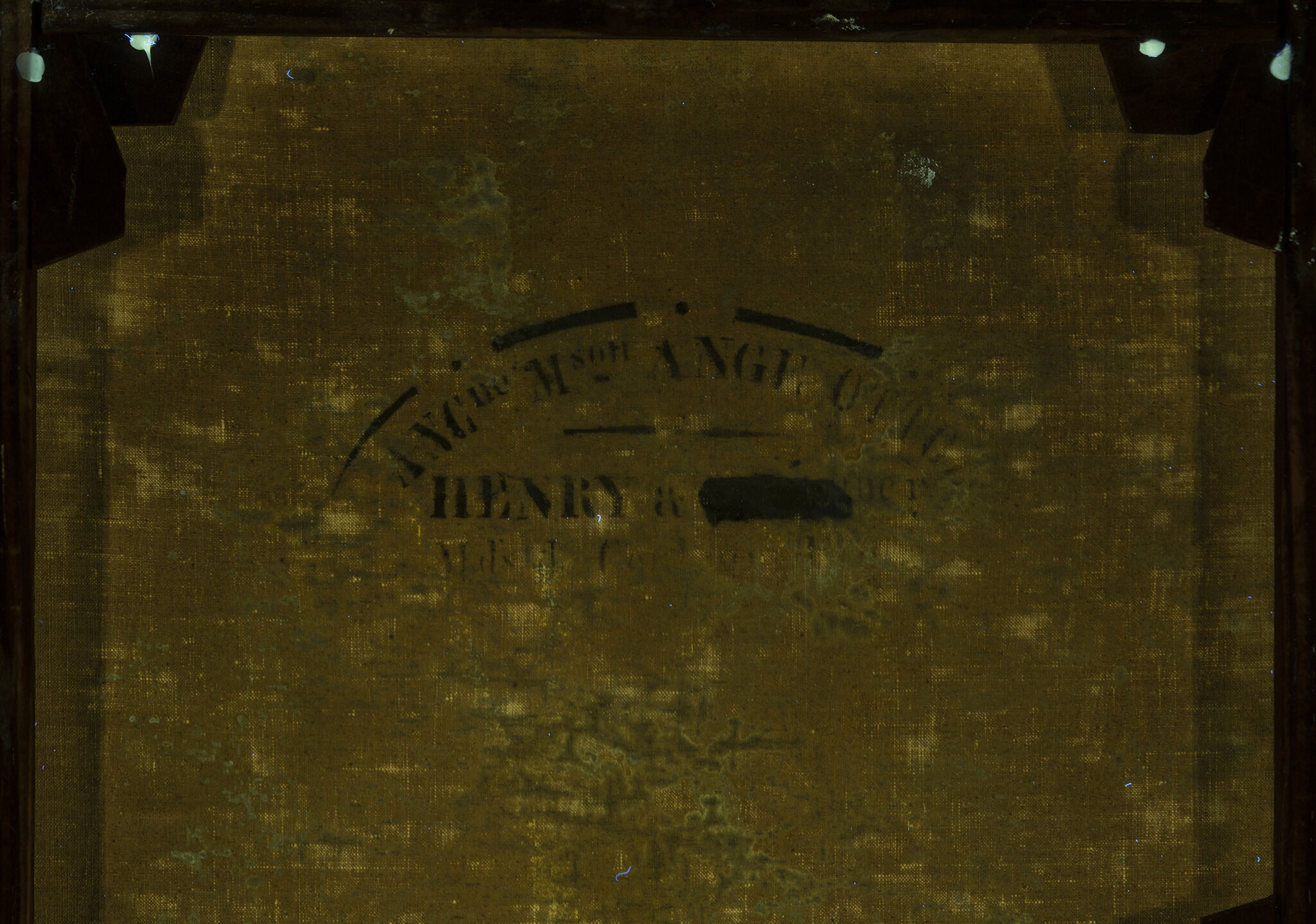

This unlined painting is in excellent condition. Before entering the Nelson-Atkins collection, the painting’s edges were strip linedstrip lining: A conservation technique used to strengthen/repair tacking margins that have weakened or failed. New fabric is adhered to the painting’s damaged tacking margins to allow the stretcher to exert its normal tensioning on the original canvas. to support the weakened tacking margins. A synthetic varnish is present and is in good condition. A minimal amount of retouchingretouching: Paint application by a conservator or restorer to cover losses and unify the original composition. Retouching is an aspect of conservation treatment that is aesthetic in nature and that differs from more limited procedures undertaken solely to stabilize original material. Sometimes referred to as inpainting or retouch. was identified along the edges of the picture plane.

Notes

-

Pascal Labreuche, Guide Labreuche: Guide historique des fournisseurs de matériel pour Artistes à Paris, 1790–1960, 2018, https://www.guide-labreuche.com/en/collection/businesses/henry-et-cre. See also Stéphanie Constantin, “The Barbizon Painters: A Guide to Their Suppliers,” Studies in Conservation 46, no. 1 (2001): 57–58.

-

This same stamp was found on the reverse of Jeanne (Spring), (1881; The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles); however, on this painting, the stamp was transcribed as “Henry & Cie.” Devi Ormond and Catherine Schmidt Patterson with Douglas MacLennan and Nathan Daly, “The Making of a Parisienne: Manet’s Methods and Materials,” in Manet and Modern Beauty, ed. Scott Allan, Emily A. Beeny, and Gloria Groom (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2019), 158.

-

One example of a nearly identically sized painting from this period is Oeillets et Clematites dans un Vase de Cristal (ca. 1882; Musée d’Orsay, Paris). For other examples, see Robert Gordon and Andrew Forge, The Last Flowers of Manet, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1986).

-

Gordon and Forge, The Last Flowers of Manet, 10.

-

The tacking margins were trimmed at some point during the painting’s history, likely during the strip-lining process. However, the ground layer extends to the edges of the remaining tacking margins.

-

This second ground layer was found along the top right corner at the turnover edge, confirming that it is a layer which extends across the entire picture plane.

-

Examples of this are visible in the high-resolution images provided for Allan, Beeny, and Groom, eds., Manet and Modern Beauty, 264, 270.

-

From early in his career, Manet preferred painting over white grounds, using the bright lower layer within the composition and as an aid to luminosity under dark scumbles. Anthea Callen, The Art of Impressionism: Painting Techniques and the Making of Modernity (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 64.

-

It is believed that most of these flower paintings were completed within one or two sessions as flowers were brought to Manet’s bedside. Gordon and Forge, The Last Flowers of Manet, 13. See also Bridget Alsdorf, “Manet’s Fleurs du mal,” in Manet and Modern Beauty, 141–44.

-

Apart from these few marks, no other underdrawing was found using microscopy or detected using infrared reflectography.

-

Øystein Sjåstad, A Theory of the Tache in Nineteenth-Century Painting (Surrey, England: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2014), 66.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Mary Frances Ivey, “Edouard Manet, White Lilacs in a Crystal Vase, ca. 1882,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.526.4033.

MLA:

Ivey, Mary Frances. “Edouard Manet, White Lilacs in a Crystal Vase, ca. 1882,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.526.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Mary Frances Ivey, “Edouard Manet, White Lilacs in a Crystal Vase, ca. 1882,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.526.4033.

MLA:

Ivey, Mary Frances. “Edouard Manet, White Lilacs in a Crystal Vase, ca. 1882,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.526.4033.

Purchased from the artist by Eugène Pertuiset (ca. 1831–1909), Paris, by April 30, 1883–at least 1889 [1];

Victor Guillaume Chocquet (1821–91), Paris, no later than April 7, 1891;

Inherited by his wife, Augustine Marie Caroline Chocquet (née Buisson, 1837–99), Paris, 1891–March 24, 1899;

Purchased at her posthumous sale, Tableaux Modernes par Cézanne, Courbet, Delacroix, Manet, Monet, Renoir, Sisley, Tassaert: Aquarelles et Dessins, Objets d’Art et d’Ameublement Anciennes Porcelaines Tendres de Sèvres; Porcelaines et Faïences diverses, Orfèvrerie; Pendules et Bronzes du XVIIIe Siècle; Sièges et Meubles des Époques Louis XV et Louis XVI, Galerie Georges Petit, Paris, July 1, 1899, lot 68, as Fleurs, through Georges Petit, Paris, by Martine-Marie-Pol, comtesse de Béarn (née de Béhague, 1870–1939), 1899–January 29, 1939 [2];

By descent to her nephew, Octave Marie Hubert, 7th marquis de Ganay (1888–1974), Paris, 1939–at least 1958 [3];

Probably by descent to his son, comte André de Ganay (b. 1924), Paris, by 1975–86 [4];

Purchased from de Ganay by Alex Reid and Lefèvre Ltd., London, 1986–87 [5];

Purchased from Alex Reid and Lefèvre Ltd. through Susan L. Brody Associates, New York, by Marion (née Helzberg, 1931–2013) and Henry (1922–2019) Bloch, Shawnee Mission, KS, August 20, 1987–June 15, 2015;

Their gift to The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 2015.

Notes

[1] See Léon Leenhoff, “Manet [ensemble de notes et de documents sur le peintre; recueillis et transcrits par Léon Leenhoff],” 1900–10, Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Estampes et photographie, RESERVE 8-YB3-2401, p. 82, as Lilas. The painting appears under “1882,” but it is unclear when Manet actually sold the work to Pertuiset. The painting appeared in the April 27, 1888 sale, Œuvres de Pertuiset et de Manet Formant la Collection Particulière de M. Pertuiset, at the Hôtel Drouot, Paris, but appears to have been bought in by Pertuiset.

[2] See annotated copy of the auction catalogue at the Art Institute of Chicago; see also A[dolphe] Tabarant, Manet et ses Œuvres (Paris: Gallimard, 1947), 462.

[3] See letter from Armand Losengard Gérant, Maison Duveen Brothers, Paris, to Duveen Brothers, New York, February 3, 1939, in which he writes, “We have been informed that she left her collection to her favorite nephew, Hubert de Ganay.” “Files regarding works of art: Behagle [sic], Comtesse de, Galerie Georges Petit Sale; ca. 1927–39,” Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, Duveen Brothers records, 1876-1981 (bulk 1909-1964), Series II, Correspondence and papers, Series II.A. Files regarding works of art.

[4] The first publication to cite comte André de Ganay as owner of White Lilacs is Denis Rouart and Daniel Wildenstein, Edouard Manet: Catalogue raisonné, vol. 1, Peintures (Lausanne: Bibliothèque des Arts, 1975), 302.

[5] A reference number in the photograph stock album (86/1/89) suggests that Reid and Lefèvre acquired this work in 1986. It was purchased from André de Ganay. Tate Archive, London, Lefevre Gallery, London records, TGA 200211, photograph stock album. See correspondence from Darragh O’Donoghue, Tate Library and Archive, London, to Glynnis Stevenson, NAMA, October 30, 2018, and correspondence from Alexander Corcoran, Lefevre Fine Art, to MacKenzie Mallon, NAMA, March 18, 2019, NAMA curatorial files.

Acquavella Galleries, New York, may have bought the painting in half-shares with Reid and Lefèvre. See a reproduction of the painting in “A Selection of Sold Paintings, Drawings, and Sculpture,” Acquavella: The First Ninety Years (New York: Acquavella Galleries, 2012), 294.

Related Work

Citation

Chicago:

Mary Frances Ivey, “Edouard Manet, White Lilacs in a Crystal Vase, ca. 1882,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.526.4033.

MLA:

Ivey, Mary Frances. “Edouard Manet, White Lilacs in a Crystal Vase, ca. 1882,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.526.4033.

Edouard Manet, The Lilac Bouquet, ca. 1882, oil on canvas, 21 1/4 x 16 1/2 in. (54 x 42 cm), Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Mary Frances Ivey, “Edouard Manet, White Lilacs in a Crystal Vase, ca. 1882,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.526.4033.

MLA:

Ivey, Mary Frances. “Edouard Manet, White Lilacs in a Crystal Vase, ca. 1882,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.526.4033.

Exposition des Œuvres de Édouard Manet, École Nationale des Beaux-Arts, Paris, January 6–28, 1884, no. 101, as Lilas blancs.

The Exhibition of the Paintings of Mr. Pertuiset, The Lion Slayer, Gainsborough Gallery, London, 1889, no. 43, as Les lilas.

Manet, 1832–1883, Musée de l’Orangerie, Paris, June 16–October 9, 1932, no. 83, as Lilas dans un Vase de Cristal.

Honderd jaar Fransche kunst tentoonstelling / Un siècle de peinture française, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, July 2–September 25, 1938, no. 163, as Lilas dans un vase de cristal.

La Pintura Francesa de David a nuestros días: Oleos, Dibujos, y Acuarelas, Salón Nacional de Bellas Artes, Montevideo, Uruguay, September 1939, no. 15; Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Buenos Aires, October–December 1939, no. 88, as Lilas en un Vaso de Cristal.

The Painting of France Since the French Revolution, M. H. De Young Memorial Museum, San Francisco, December 1940–January 1941, and November 1941–January 1942, no. 68, as Lilacs in a Crystal Vase.

French Painting from David to Toulouse-Lautrec: Loans from French and American Museums and Collections, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, February 6–March 26, 1941, no. 83, as Lilacs in a Crystal Vase.

Masterpieces of French Art, Art Institute of Chicago, April 10–May 20, 1941, no. 98, as Lilacs in a Crystal Vase.

Natures Mortes Françaises du XVIIe Siècle à nos Jours, Galerie Charpentier, Paris, December 1951, no. 106, as Les lilas.

Vier Eeuwen Stilleven in Frankrijk, Museum Boymans, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, July 10–September 20, 1954, no. 90, as Seringen in een kristallen vaas / Lilas dans une vase de cristal.

Peinture et Impressionnisme de Géricault à Monet, Galerie Alfred Daber, Paris, June 7–July 7, 1956, no. 16, as Lilas dans un vase de cristal.

Fem Sekler Fransk Konst: Miniatyrer, Målningar, Teckningar, 1400–1900, Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, August 15–November 9, 1958, no. 145, as Kristallvas med Syrener / Lilas dans un vase de cristal.

Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, June 9–September 9, 2007, no. 2, as White Lilacs in a Crystal Vase (Lilas blancs dans un vase de cristal).

Manet and Modern Beauty, Art Institute of Chicago, May 26–September 7, 2019; J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, October 1, 2019–January 5, 2020, no. 86, as White Lilacs in a Crystal Vase.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Mary Frances Ivey, “Edouard Manet, White Lilacs in a Crystal Vase, ca. 1882,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.526.4033.

MLA:

Ivey, Mary Frances. “Edouard Manet, White Lilacs in a Crystal Vase, ca. 1882,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.526.4033.

Fernand Lochard, “Reproductions d’Œuvres d’Edouard Manet,” ed. Léon Leenhoff, 1883–1884, photograph album with annotations, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, département Estampes et photographie, 4-DC-300 (H), no. 48, (repro.), as Vase de fleurs.

Fernand Lochard, “Reproductions d’Œuvres d’Edouard Manet (peintures, tableaux de 1880 à 1883),” ed. Léon Leenhoff, 1883–1884, photograph album with annotations, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, département Estampes et photographie, 4-DC-300 (G, 4), no. 386, (repro.).

Exposition des Œuvres de Édouard Manet, exh. cat. (Paris: Imprimerie de A. Quantin, 1884), 56, as Lilas blancs.

Anatole Godet, “Exposition rétrospective de l’œuvre d’Édouard Manet, Paris, École des beaux-arts, 6 au 28 janvier 1884,” 1884, photograph album, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, département Estampes et photographie, 4-DC-300 (F,1), folio 21, (repro.).

Tableaux Modernes: aquarelles, dessins, miniatures, sculptures, porcelains, bronzes, meubles (Paris: Hotel Drouot, April 27, 1888), 12, as Lilas blancs.

“Tableaux modernes,” La Chronique des arts et de la curiosité: supplement à la Gazette des beaux-arts 20 (May 19, 1888): 153, as Lilas blancs.

The Exhibition of the Paintings of Mr. Pertuiset, The Lion Slayer, exh. cat. (London: William Clowes and Sons, 1889), 16, as Les lilas.

Catalogue des Tableaux Modernes par Cézanne, Courbet, Delacroix, Manet, Monet, Renoir, Sisley, Tassaert: Aquarelles et Dessins, Objets d’Art et d’Ameublement Anciennes Porcelaines Tendres de Sèvres; Porcelaines et Faïences diverses, Orfèvrerie; Pendules et Bronzes du XVIIIe Siècle; Sièges et Meubles des Époques Louis XV et Louis XVI, exh. cat. (Paris: Galerie Georges Petit, 1899), 16, 45, as Fleurs.

Léon Leenhoff, “Manet [ensemble de notes et de documents sur le peintre; recueillis et transcrits par Léon Leenhoff],” 1900–1910, Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Estampes et photographie, RESERVE 8-YB3-2401, p. 82, as Lilas.

Théodore Duret, Histoire d’Édouard Manet et de son œuvre (Paris: H. Floury, 1902), 276, as Fleurs.

Théodore Guédy, Manuel pratique du Collectionneur de Tableaux: Comprenant les principales Ventes des XVIIIe, XIXe siècles jusqu’à nos jours, des œuvres des Peintres de toutes les écoles (Paris, [1906]), 97, as Fleurs.

Théodore Duret, Histoire d’Édouard Manet et de Son œuvre, Avec un Catalogue des Peintures et des Pastels, new ed. (Paris: Bernheim-Jeune, 1919), no. 320, pp. 283, as Fleurs.

Étienne Moreau-Nélaton, Manet raconté par lui-même, vol. 2 (Paris: Henri Laurens, 1926), 93, 143, (repro.), as Lilas.

A[dolphe] Tabarant, Manet: Histoire catalographique (Paris: Éditions Montaigne, 1931), no. 402, pp. 433, 587, as Lilas (Grand vase à pied carré).

Paul Jamot and Georges Wildenstein, Manet, vol. 1 (Paris: Beaux-Arts, 1932), no. 511, p. 181, as Lilas dans un Vase de Cristal.

Manet, 1832–1883, exh. cat. (Paris: Édition des Musées Nationaux, 1932), 66, (repro.), as Lilas dans un Vase de Cristal.

Honderd jaar Fransche kunst tentoonstelling / Un siècle de peinture française, exh. cat. (Amsterdam: Stedelijk Museum, 1938), 96, as Lilas dans une vase de cristal.

La Pintura Francesa de David a nuestros días: Oleos, Dibujos, y Acuarelas, exh. cat. (Montevideo, Uruguay: Salón Nacional de Bellas Artes, 1939), 40, (repro.), as Lilas en un Vaso de Cristal.

A[dolphe] Tabarant, Manet (Paris: Éditions Albert Skira, 1939), unpaginated, (repro.), as Lilas Dans un Vase de Cristal.

The Painting of France since the French Revolution, exh. cat. (San Francisco: Recorder, 1940), 25–26, 78, (repro.), as Lilacs in a Crystal Vase.

French Painting from David to Toulouse-Lautrec: Loans from French and American Museums and Collections, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1941), 27, as Lilacs in a Crystal Vase.

Masterpieces of French Art, exh. cat. (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 1941), 30, as Lilacs in a Crystal Vase.

A[dolphe] Tabarant, Manet et ses œuvres (Paris: Gallimard, 1947), 462, 545, 616, (repro.), as Lilas blanc.

Natures mortes françaises du XVIIe siècle à nos jours, exh. cat. (Paris: Galerie Charpentier, 1951), unpaginated, as Les lilas.

Vier eeuwen stilleven in Frankrijk, exh. cat. (Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Museum Boymans, 1954), 78, (repro.), as Seringen in een kristallen vaas and Lilas dans une vase de cristal.

Peinture et impressionnisme de Géricault à Monet, exh. cat. (Paris: Galerie Alfred Daber, 1956), unpaginated, (repro.), as Lilas dans un vase de cristal.

Fem Sekler Fransk Konst: Miniatyrer, Målningar, Teckningar, 1400–1900, exh. cat. (Stockholm: Nationalmuseum, 1958), 1:111–12, 202, as Kristallvas med Syrener / Lilas dans un vase de cristal.

Sandra Orienti, The Complete Paintings of Manet, 1st ed. (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1967), no. 411E, pp. 120–21, (repro.).

John Rewald, “Chocquet and Cézanne,” Gazette des beaux-arts 74, nos. 1206–07 (July–August 1969): 64, 75, 79, 93n29.

Sandra Orienti, The Complete Paintings of Manet, 2nd ed. (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1970), no. 411E, pp. 120–21, (repro.).

Denis Rouart and Daniel Wildenstein, Edouard Manet: Catalogue raisonné, vol. 1, Peintures (Lausanne: Bibliothèque des Arts, 1975), no. 418, p. 302, (repro.), as Lilas dans un Vase de Cristal.

Robert Gordon and Andrew Forge, The Last Flowers of Manet, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1986), 13, 38–39, (repro.), as Lilas Blancs dans un Vase de Cristal (White Lilacs in a Crystal Vase).

Bobbie Leigh, “Magnificent Obsession,” Art and Antiques 29, no. 6 (June 2006): 65, as White Lilacs in a Crystal Vase.

Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 10, 15, 30, 34–37, 155, (repro.), as White Lilacs in a Crystal Vase (Lilas blancs dans un vase de cristal).

“Inaugural Exhibitions Celebrate Kansas City,” Member Magazine (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (Fall 2006): 3.

Alice Thorson, “First Public Exhibition: Marion and Henry Bloch’s Art Collection,” Kansas City Star (June 3, 2007): E4.

Steve Paul, “Pretty Pictures: Marion and Henry Bloch’s collection of superb Impressionist masters,” Panache 4, no. 3 (Fall 2007): 20.

“Kansas City Riches,” New York Times 159, no. 54,942 (February 5, 2010): C26.

Alice Thorson, “Museum to Get 29 Impressionist Works from the Bloch Collection,” Kansas City Star (February 5, 2010): A1.

Manet, inventeur du Moderne, exh. cat. (Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 2011), 67, 69n72.

“A Selection of Sold Paintings, Drawings, and Sculpture,” Acquavella: The First Ninety Years (New York: Acquavella Galleries, 2012), 294, (repro.), as White Lilacs in a Crystal Vase.

Diane Stafford, “Bloch Gift to Go for Nelson Upgrade,” Kansas City Star 135, no. 203 (April 8, 2015): A8.

“Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art officially accessions Bloch Impressionist masterpieces,” Artdaily.org (July 25, 2015): http://artdaily.com/news/80246/Nelson-Atkins-Museum-of-Art-officially-accessions-Bloch-Impressionist-masterpieces#.V6oGwlKFO9I.

Julie Paulais, “Le Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art reçoit des tableaux impressionnistes en échange de leurs répliques,” Le Journal des arts (July 30, 2015): unpaginated.

Josh Niland, “The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Acquires a Renowned Collection of Impressionist and Postimpressionist Art,” architecturaldigest.com (August 6, 2015): https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/nelson-atkins-museum-accessions-bloch-art-collection.

Nancy Staab, “Van Gogh is a Go!” 435: Kansas City’s Magazine (September 2015): 76.

Mariantonia Reinhard-Felice, Victor Chocquet: Ami et collectionneur des impressionnistes: Renoir, Cézanne, Monet, Manet, exh. cat. (Munich: Hirmer Verlag, 2015), 226 (repro.), as Lilas blancs dans un vase de cristal.

Nina Siegal, “Upon Closer Review, Credit Goes to Bosch,” New York Times 165, no. 57130 (February 2, 2016): C5.

“Nelson-Atkins to unveil renovated Bloch Galleries of European Art in winter 2017,” Artdaily.org (July 20, 2016): http://artdaily.com/news/88852/Nelson-Atkins-to-unveil-renovated-Bloch-Galleries-of-European-Art-in-winter-2017-#.W-NDepNKhaQ.

“Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art celebrates generosity of Henry Bloch with new acquisition,” Artdaily.org (October 18, 2016): http://artdaily.com/news/90923/Nelson-Atkins-Museum-of-Art-celebrates-generosity-of-Henry-Bloch-with-new-acquisition#.W-NDv5NKhaQ.

Catherine Futter et al., Bloch Galleries: Highlights from the Collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2016), 78, (repro.), as White Lilacs in a Crystal Vase.

Kelly Crow, “Museum Rewards Donor with Fake Art to Hang at Home,” Wall Street Journal (January 25, 2017): https://www.wsj.com/articles/museum-rewards-donor-with-fake-art-to-hang-at-home-1485370768.

Albert Hect, “Henry Bloch’s Masterpieces Collection to Go on Display at Nelson-Atkins Museum,” Jewish Business News (February 26, 2017): http://jewishbusinessnews.com/2017/02/26/henry-bloch-masterpieces-collection/.

David Frese, “Inside the Bloch Galleries: An interactive experience,” Kansas City Star 137, no. 169 (March 5, 2017): 1D, 5D, (repro.), as White Lilacs in a Crystal Vase.

“Editorial: Thank you, Henry and Marion Bloch”, Kansas City Star (March 7, 2017): http://www.kansascity.com/opinion/editorials/article137040948.html.

Hampton Stevens, “(Not Actually) 12 Things To Do During The Big 12 Tournament,” Flatland: KCPT’s Digital Magazine (March 9, 2017): http://www.flatlandkc.org/arts-culture/sports/not-actually-12-big-12-tournament/.

Laura Spencer, “The Nelson-Atkins’ Bloch Galleries feature Old Masterworks and New Technology,” KCUR (March 10, 2017): http://kcur.org/post/nelson-atkins-bloch-galleries-feature-old-masterworks-and-new-technology#stream/0.

Victoria Stapley-Brown, “Nelson-Atkins Museum’s new European art galleries come with a ‘love story’,” Art Newspaper (March 10, 2017): http://theartnewspaper.com/news/museums/nelson-atkins-museum-s-new-european-art-galleries-come-with-a-love-story/.

Harry Bellet, “Don du ciel pour le Musée Nelson-Atkins,” Le Monde (March 13, 2017): http://www.lemonde.fr/arts/article/2017/03/13/don-du-ciel-pour-le-musee-nelson-atkins_5093543_1655012.html.

Menachem Wecker, “Jewish Philanthropist Establishes Kansas City as Cultural Mecca,” Forward (March 14, 2017): http://forward.com/culture/365264/jewish-philanthropist-establishes-kansas-city-as-cultural-mecca/ [repr. in, Menachem Wecker, “Kansas City Collection Is A Chip Off the Old Bloch,” Forward (March 17, 2017): 20-22].

Juliet Helmke, “The Bloch Collection Takes up Residence in Kansas City’s Nelson Atkins Museum,” BlouinArtInfo International (March 15, 2017): http://www.blouinartinfo.com/news/story/2005267/the-bloch-collection-takes-up-residence-in-kansas-citys?utm_source=Blouin+Artinfo+Newsletters&utm_ campaign=a2555adf27-Daily+Digest+03.16.2017+-+8+AM&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_df23dbd3c6-a2555adf27-83695841.

Erich Hatala Matthes, “Digital replicas are not soulless—they help us engage with art,” Apollo (March 23, 2017): https://www.apollo-magazine.com/digital-replicas-3d-printing-original-artworks/.

Louise Nicholson, “How Kansas City got its magnificent museum,” Apollo (April 7, 2017): https://www.apollo-magazine.com/how-kansas-city-got-its-magnificent-museum/.

Lilly Wei, “Julián Zugazagoitia: ‘Museums should generate interest and open a door that leads to further learning’,” Studio International (August 21, 2017): http://studiointernational.com/index.php/julian-zugazagoitia-director-nelson-atkins-museum-of-art-kansas-city-interview.

Robert D. Hershey, Jr., “Henry Bloch, H&R Block’s cofounder, dies at 96,” Boston Globe (April 23, 2019): https://www3.bostonglobe.com/metro/obituaries/2019/04/23/henry-bloch-block-cofounder/?arc404=true.

Robert D. Hershey Jr., “Henry W. Bloch, Tax-Preparation Pioneer (and Pitchman), Is Dead at 96,” New York Times (April 23, 2019): https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/23/obituaries/henry-w-bloch-dead.html.

Claire Selvin, “Henry Wollman Bloch, Collector and Prominent Benefactor of Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Is Dead at 96,” ArtNews (April 23, 2019): http://www.artnews.com/2019/04/23/henry-bloch-dead-96/.

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “Henry Bloch, co-founder of H&R Block, dies at 96,” Kansas City Star 139, no. 219 (April 24, 2019): 1A.

“Henry Wollman Bloch (1922-2019),” Art Forum (April 24, 2019): https://www.artforum.com/news/henry-wollman-bloch-1922-2019-79547.

Frank Morris, “Henry Bloch, Co-Founder Of H&R Block, Dies At 96,” npr.org (April 24, 2019): https://www.npr.org/2019/04/24/716641448/henry-bloch-co-founder-of-h-r-block-dies-at-96.

Ignacio Villarreal, “Nelson-Atkins mourns loss of Henry Bloch,” ArtDaily.org (April 24, 2019): http://artdaily.com/news/113035/Nelson-Atkins-mourns-loss-of-Henry-Bloch#.XMB76qR7laQ.

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “H&R Block co-founder, philanthropist Bloch dies,” Cass County Democrat Missourian 140, no. 29 (April 26, 2019): 1A.

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “KC businessman and philanthropist Henry Bloch dies,” Lee’s Summit Journal 132, no. 79 (April 26, 2019): 1A.

Luke Nozicka, “Family and friends remember Henry Bloch of H&R Block,” Kansas City Star 139, no. 225 (April 30, 2019): 4A [repr. Luke Nozicka, “Family and friends remember Henry Bloch of H&R Block,” Kansas City Star 139, no. 228 (May 3, 2019): 3A].

Manet and Modern Beauty, exh. cat. (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2019), 143, 268, 320, (repro.), as White Lilacs in a Crystal Vase.