![]()

Edouard Manet, Portrait of Lise Campineanu, 1878

| Artist | Edouard Manet, French, 1832–83 |

| Title | Portrait of Lise Campineanu |

| Object Date | 1878 |

| Alternate and Variant Titles | Fillette à mi-corps; erroneously as Portrait de Mlle de Bellio; erroneously as Portrait de Line Campineanu |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (Unframed) | 21 7/8 x 18 5/16 in. (55.6 x 46.5 cm) |

| Signature | Signed and dated lower left: Manet / 1878 |

| Credit Line | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 36-5 |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Edouard Manet, Portrait of Lise Campineanu, 1878,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.524.5407.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Edouard Manet, Portrait of Lise Campineanu, 1878,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.524.5407.

During the summer of 1878, the Romanian Finance Minister Ion Campineanu and his family were among the international crowd of thirteen million who flocked to Paris for the Exposition universelle. It was the city’s third time hosting the world’s fair, reflecting the city’s reputation as a cultural center. At that time, Ion and his wife, Irina, commissioned a portrait of their six-year-old daughter, Eliza Campineanu (called “Lise,” 1872–1949), from Edouard Manet at the suggestion of Irina’s uncle Georges de Bellio (né Gheorge Bellu, 1828–94).1Remus Niculescu, Georges de Bellio, l’ami des impressionnistes, partial reprint of Revue Roumaine d’Histoire de l’Art 1, no. 2 (Bucarest: Éditions de l’Académie de la République Populaire Roumaine, 1964), 220. De Bellio, a homeopathic doctor, had moved to Paris in 1851 and remained there for the rest of his life.2Niculescu, Georges de Bellio, l’ami des impressionnistes, 212. He often gave friends medical advice and would eventually treat Edouard Manet in the late stages of his struggle with syphilis. He was an early supporter of Impressionism, purchasing works by Claude Monet (1840–1926), Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919), and Berthe Morisot (1841–95) when they had little support from critics and buyers. De Bellio’s knowledge of the French art scene proved invaluable for his nephew-in-law’s efforts to present his family as sophisticated and European. As Justine De Young notes, “Manet was praised by critics for his skill in conjuring accurate and realistic portrayals of modern people wearing the correct dress, displaying the proper attitude, and occupying the appropriate milieu for their socioeconomic status.”3Gloria Groom, Impressionism, Fashion, and Modernity, exh. cat. (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2012), 241. With this goal in mind, the Campineanus wisely chose an artist closely identified with the “explicit and implicit signs of Parisian consumer culture.”4Ruth E. Iskin, Modern Women and Parisian Consumer Culture in Impressionist Painting (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 115. Attired in the latest fashions and rendered on canvas by a society artist, Lise Campineanu is a stand-in for her family’s social aspirations to represent Romania on an international stage as a cosmopolitan society.

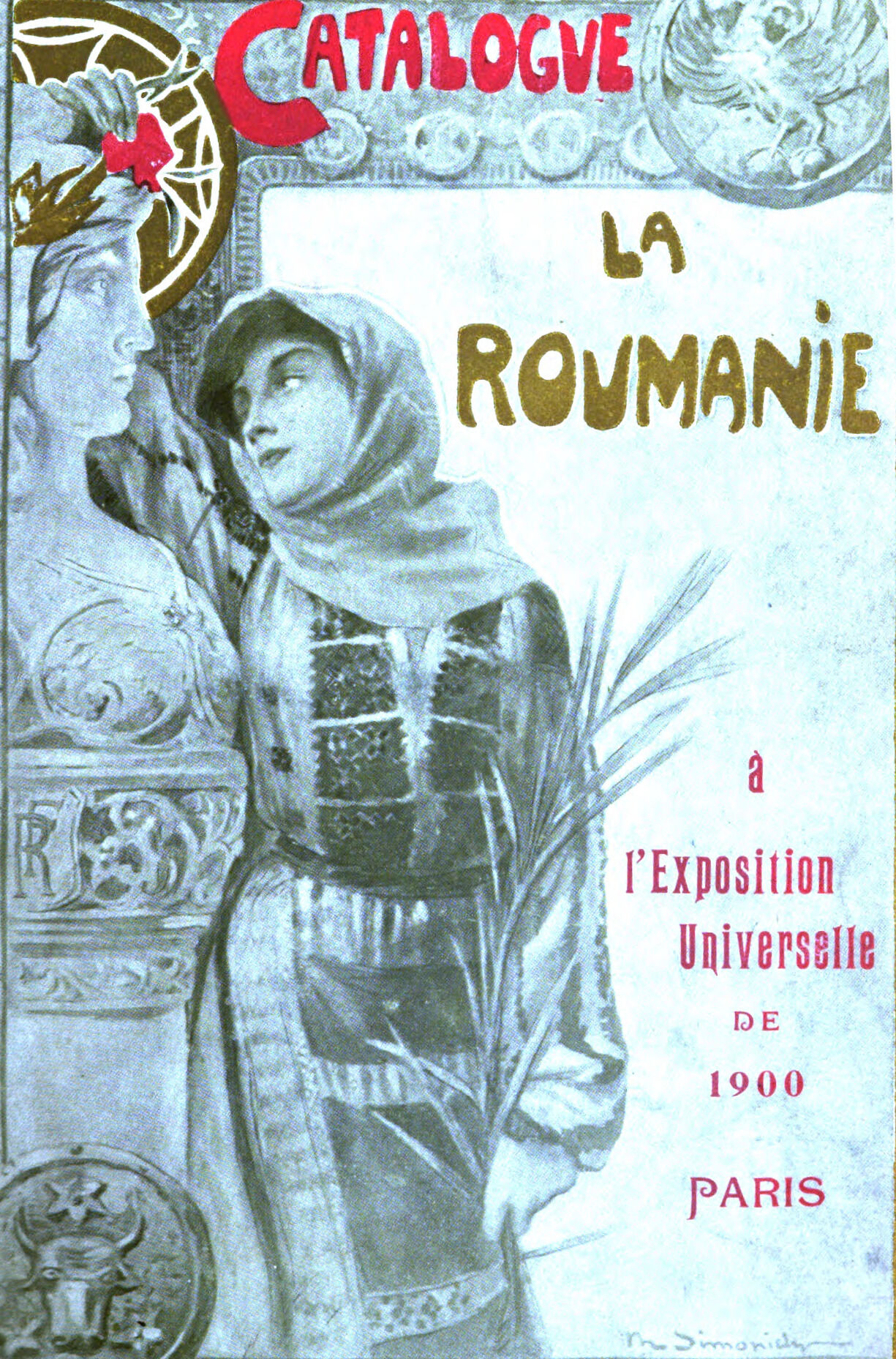

In 1878, the year Manet painted Lise, Romania celebrated its official independence from the Ottoman Empire following Turkey’s defeat in the Russo-Turkish War. Since the 1830s, wealthy Romanians had flocked to Paris for their educations and returned with a strong desire to apply French revolutionary thinking at home.5Shona Kallestrup, Art and Design in Romania, 1866–1927: Local and International Aspects of the Search for National Expression (Boulder, CO: East European Monographs, 2006), 3. Like citizens of many other European nations at the time, Romanians defined themselves in ethnic terms. The majority of Romanians practiced Eastern Orthodoxy, just as their geographic neighbors in the Balkans did, but the Romanian language is Latin in origin, like French, rather than Slavic. Their nation’s name, chosen in 1862, establishes that Romanians saw themselves as “citizens of Rome” rather than denizens of Eastern Europe.6“român,” Explanatory Dictionary of the Romanian Language, accessed August 6, 2020, https://dexonline.ro/definitie/rom%C3%A2n. Western influence, especially French influence, played a significant role in Romania’s election of the German-born Prince Karl of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, later King Carol I, to serve as constitutional monarch. The provisional government of 1866 had “decided that internal stability and international recognition could be best achieved by inviting a foreign prince to rule the principalities.”7Kallestrup, Art and Design in Romania, 1866–1927, 3. After delivering his coronation speech in French, the prince set about importing western artisans to build his summer palace and design the civic spaces of the new country. He had the capital city of Bucharest redesigned along the lines of Baron Haussmann’s ongoing renovation of Paris, complete with gas lighting, wide boulevards, and a train station aptly named the “Gara de Nord,” after Paris’s famous Gare du Nord.8Constantin C. Giurescu, Istoria Bucureştilor Din Cele Mai Vechi Timpuri Pînă În Zilele Noastre (Bucharest: Editura Pentru Literatura, 1966), 154–61, 169–71. France was the paradigm for the first art academies established in Romania, and even then the leading artists of late-nineteenth-century Bucharest studied in Paris.9For more on Nicolae Grigorescu and Ion Andreescu, see S. A. Mansbach, “The ‘Foreignness’ of Classical Modern Art in Romania,” Art Bulletin 80, no. 3 (September 1998): 534–54; and Valentina Iancu and Monica Enache, Nicolae Grigorescu (1838–1907): L’Age de l’Impressionnisme en Roumanie, exh. cat. (Milan: Silvana Editoriale, 2011).

The emblematic attire seen on Simonidi’s cover, however, was not the costume of Romania’s highest social circles. For example, photographs of the queen consort, Elisabeth of Wied, showcase the transition from crinolines to bustles that marked the shift in western European women’s fashions from the 1860s into the 1870s. When Elisabeth donned Romanian national dress, it verged on the fantastical, something the queen’s biographer, Natalie von Stackelberg, commented on extensively. At her wedding in 1869, the German-born Elisabeth received a gift of ethnic dress, and the peasants she waved to from her carriage are described in detail in “dazzlingly white linen and embroidered garments.”13Von Stackelberg, The Life of Carmen Sylva, 148–49, 151. Von Stackelberg goes on to describe the queen donning the Romanian garments herself in order to help “encourage native industry.”14Von Stackelberg, The Life of Carmen Sylva, 163. She continues to describe the queen’s outings in this ethnic garb somewhat romantically:

One could imagine oneself transported into the middle of a fairy tale whilst a troop of lovely ladies, in glittering garments which glow with bright colors, suddenly appear on a hill-side or beside a mountain stream under mighty beech and fir-trees. . . . The whole oriental costume has its charms enhanced by the lively southern temperament of the Romanian ladies.15Von Stackelberg, The Life of Carmen Sylva, 163.

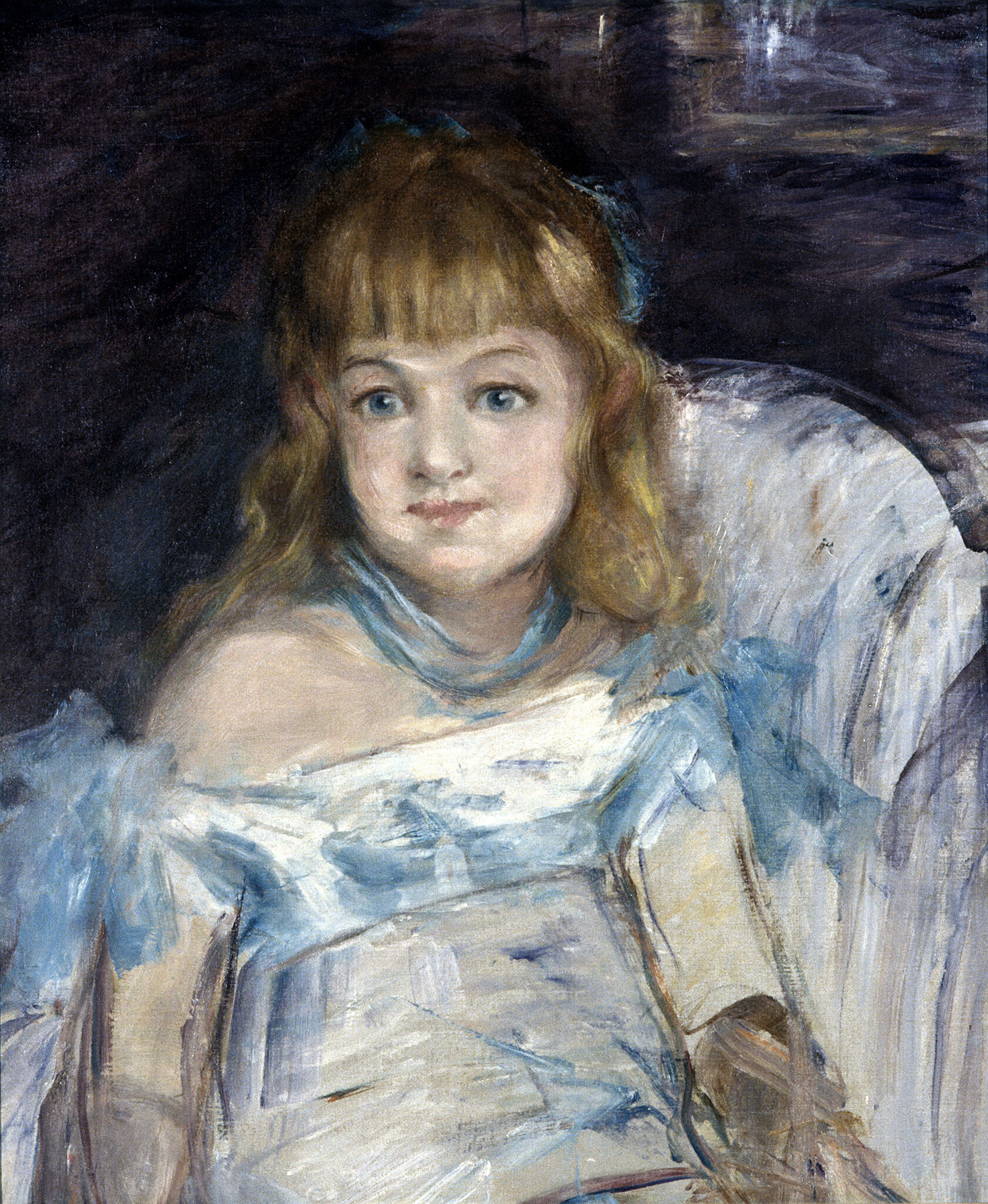

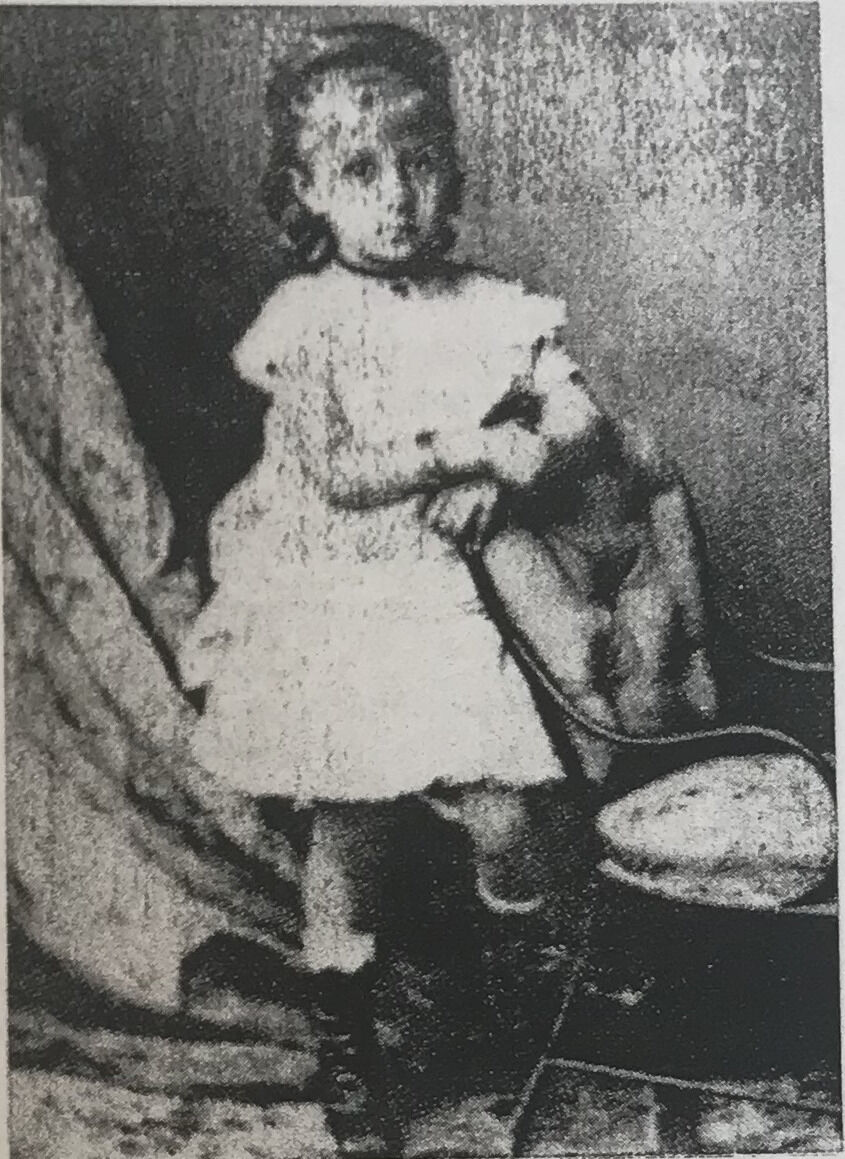

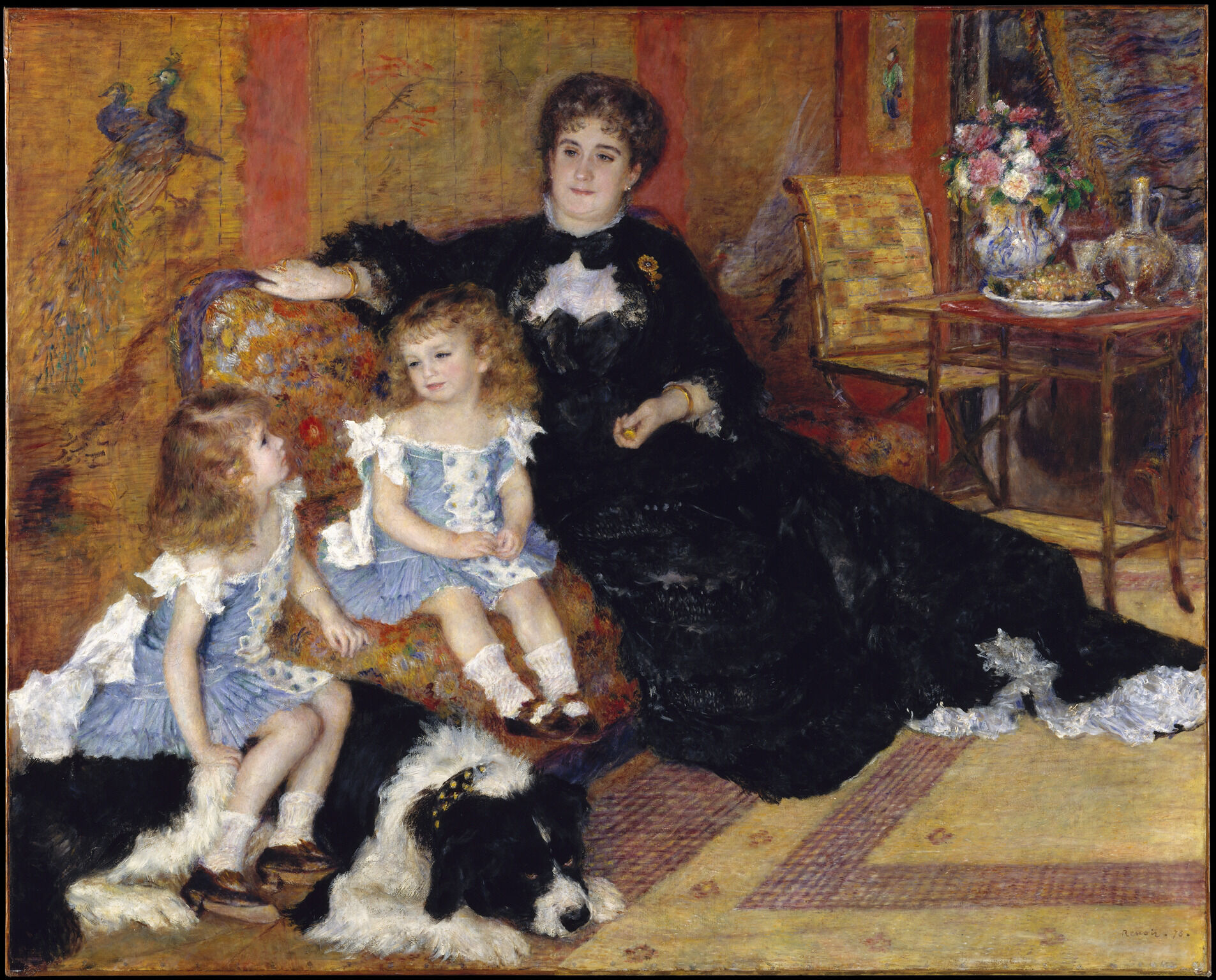

Likewise, the Campineanu family preferred to present young Lise in the style of dress seen in other painted portraits and cartes-de-visitescarte-de-visite: French for “calling card.” A small card bearing a photographic portrait, which a sitter exchanged with family and friends. Cartes-de-visites were very popular in Europe and the United States in the mid-nineteenth century. of French and British children of that time.17In 1854, the photographer André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri patented an inexpensive mode of photography called the carte de visite. It involved a four-lens camera with a sliding plate that allowed the user to capture eight images on one glass plate. Portrait sitters then exchanged these multiples with family and friends. Debra N. Mancoff, Fashion in Impressionist Paris (London: Merrell, 2012), 96–97. In each representation of Lise from this sitting—the Nelson-Atkins canvas, the Spencer Museum study (Fig. 3), and the photograph (Fig. 4)—a gamine blonde child poses with a studio chair in an off-the-shoulder dress very similar to the ones worn by Georgette and Paul Charpentier in Renoir’s 1878 portrait of them with their mother (Fig. 5).18Boys up to the age of five or six were dressed quite similarly to girls of the same age. Anne Buck, Victorian Costume and Costume Accessories (New York: T. Nelson and Sons, 1961), 198. All three images of Lise feature minute versions of the style worn by Mary Cassatt’s sitter in Woman with a Pearl Necklace in a Loge (1879; Philadelphia Museum of Art),19For more information, visit the painting’s page on the Philadelphia Museum of Art website, accessed February 2, 2021, https://www.philamuseum.org/collections/permanent/72182.html. which was intentional, as it was customary in the 1870s for children’s clothes to conform to adult trends.20Buck, Victorian Costume and Costume Accessories, 203. Renoir also had an innate understanding that the Charpentier children were representatives of their family and social class. He reinforced Mme. Charpentier’s urbanity by highlighting “the extreme elegance of her children, who are dressed identically in embroidered white silk reception dresses, according to the custom of the time.”21See Sylvie Patry’s essay on the Charpentier portrait, “Pierre-Auguste Renoir: Madame Georges Charpentier and Her Children,” in Groom, Impressionism, Fashion, and Modernity, 245–51. Renoir also painted studies of each of the three Charpentiers individually, and his 1876 portrait of Georgette Charpentier (Bridgestone Museum of Art, Tokyo), who was the same age as Lise, is another example of the “ideal” stylish European girl seated in a silk reception dress. Like these Parisian children, Lise is dressed to interact with the surrounding society. Each image of Lise is indistinguishable from contemporaneous French society portraits, down to her hair styled à la chien (French for “as the dog”), with a short fringe in the front and a pouf of ringlets in the back.22This style was eminently fashionable, as detailed in a contemporaneous anecdote about the family of writer Victor Hugo: “His wife and daughters put back their hair, as now petite Jeanne learns to toss away her sunny curls and stroke back the fashionable locks ‘à la chien’ when she most wants to please her grandfather.” Theodora Louisa Lane Teeling, “Victor Hugo in Exile,” Irish Monthly 8, no. 82 (April 1880): 196. Jeanne Hugo, granddaughter of the author, grew up to be a socialite of the Belgian Belle Époque.

Fig. 3. Edouard Manet, Little Girl in an Armchair, 1878, oil on canvas transferred to hardboard, 21 11/16 x 18 1/4 in. (55.2 x 46.4 cm), Spencer Museum of Art, Lawrence, KS. Gift of Charles Curry, 1958.0121

Fig. 3. Edouard Manet, Little Girl in an Armchair, 1878, oil on canvas transferred to hardboard, 21 11/16 x 18 1/4 in. (55.2 x 46.4 cm), Spencer Museum of Art, Lawrence, KS. Gift of Charles Curry, 1958.0121

Fig. 4. Photographer unknown, Photograph of Lise Campineanu, ca. 1878, photograph, location unknown, reprinted in John Rewald, The History of Impressionism, 4th rev. ed. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1973), 421

Fig. 4. Photographer unknown, Photograph of Lise Campineanu, ca. 1878, photograph, location unknown, reprinted in John Rewald, The History of Impressionism, 4th rev. ed. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1973), 421

Notes

-

Remus Niculescu, Georges de Bellio, l’ami des impressionnistes, partial reprint of Revue Roumaine d’Histoire de l’Art 1, no. 2 (Bucarest: Éditions de l’Académie de la République Populaire Roumaine, 1964), 220.

-

Niculescu, Georges de Bellio, l’ami des impressionnistes, 212.

-

Gloria Groom, Impressionism, Fashion, and Modernity, exh. cat. (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2012), 241.

-

Ruth E. Iskin, Modern Women and Parisian Consumer Culture in Impressionist Painting (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 115.

-

Shona Kallestrup, Art and Design in Romania, 1866–1927: Local and International Aspects of the Search for National Expression (Boulder, CO: East European Monographs, 2006), 3.

-

“român,” Explanatory Dictionary of the Romanian Language, accessed August 6, 2020, https://dexonline.ro/definitie/rom%C3%A2n.

-

Kallestrup, Art and Design in Romania, 1866–1927, 3.

-

Constantin C. Giurescu, Istoria Bucureştilor Din Cele Mai Vechi Timpuri Pînă În Zilele Noastre (Bucharest: Editura Pentru Literatura, 1966), 154–61, 169–71.

-

For more on Nicolae Grigorescu and Ion Andreescu, see S. A. Mansbach, “The ‘Foreignness’ of Classical Modern Art in Romania,” Art Bulletin 80, no. 3 (September 1998): 534–54; and Valentina Iancu and Monica Enache, Nicolae Grigorescu (1838–1907): L’Age de l’Impressionnisme en Roumanie, exh. cat. (Milan: Silvana Editoriale, 2011).

-

Ambroise Baudry designed the Romanian pavilion for the nation’s inaugural appearance at a world’s fair in 1867. In 1900, Jean-Camille Formigé designed the Romanian pavilion as a conglomeration of elements from Romanian religious sites that, in turn, had been “restored” by fellow Frenchman Emile André Lecomte de Noüy, who also curated the Romanian section. Shona Kallestrup, “Romanian ‘National Style’ and the 1906 Bucharest Jubilee Exhibition,” Journal of Design History 15, no. 3 (2002): 147.

-

Kallestrup, “Romanian ‘National Style’,” 147.

-

According to an account of the Romanian royal wedding of 1859, peasants flanked the royal carriage “in their richest dress. . . . Each one carried a fir-tree decorated with gilded apples and glittering chains of gold tinsel. This is the emblem of a Romanian wedding which must never be wanting at such ceremonies.” Natalie von Stackelberg, The Life of Carmen Sylva, trans. Hilda Elizabeth Deichmann (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner, 1890), 143.

-

Von Stackelberg, The Life of Carmen Sylva, 148–49, 151.

-

Von Stackelberg, The Life of Carmen Sylva, 163.

-

Von Stackelberg, The Life of Carmen Sylva, 163.

-

King Carol I and Elisabeth of Wied’s passion for bringing western European artists to Romania is discussed in Lucia Carta, “Painter and King: Gustav Klimt’s Early Decorative Work at Peleş Castle, Romania, 1883–1884,” Studies in the Decorative Arts 12, no. 1 (Fall/Winter 2004–2005): 98–129; and in Kallestrup, Art and Design in Romania, 1866–1927, 15–41.

-

In 1854, the photographer André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri patented an inexpensive mode of photography called the carte de visite. It involved a four-lens camera with a sliding plate that allowed the user to capture eight images on one glass plate. Portrait sitters then exchanged these multiples with family and friends. Debra N. Mancoff, Fashion in Impressionist Paris (London: Merrell, 2012), 96–97.

-

Boys up to the age of five or six were dressed quite similarly to girls of the same age. Anne Buck, Victorian Costume and Costume Accessories (New York: T. Nelson and Sons, 1961), 198.

-

For more information, visit the painting’s page on the Philadelphia Museum of Art website, accessed February 2, 2021, https://www.philamuseum.org/collections/ permanent/72182.html.

-

Buck, Victorian Costume and Costume Accessories, 203.

-

See Sylvie Patry’s essay on the Charpentier portrait, “Pierre-Auguste Renoir: Madame Georges Charpentier and Her Children,” in Groom, Impressionism, Fashion, and Modernity, 245–51. Renoir also painted studies of each of the three Charpentiers individually, and his 1876 portrait of Georgette Charpentier (Bridgestone Museum of Art, Tokyo), who was the same age as Lise, is another example of the “ideal” stylish European girl seated in a silk reception dress.

-

This style was eminently fashionable, as detailed in a contemporaneous anecdote about the family of writer Victor Hugo: “His wife and daughters put back their hair, as now petite Jeanne learns to toss away her sunny curls and stroke back the fashionable locks ‘à la chien’ when she most wants to please her grandfather.” Theodora Louisa Lane Teeling, “Victor Hugo in Exile,” Irish Monthly 8, no. 82 (April 1880): 196. Jeanne Hugo, granddaughter of the author, grew up to be a socialite of the Belgian Belle Époque.

-

Manet rented a studio at 77 rue d’Amsterdam from July 1878 to April 1879. See Gloria Groom’s essay, “Foregrounding Manet’s Backgrounds,” in Scott Allan, Emily A. Beeny, and Gloria Groom, eds., Manet and Modern Beauty, exh. cat. (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2019), 71–72.

-

In a letter to Claude Monet dated August 31, 1878, Georges de Bellio wrote, “[Manet] made a portrait of my great-niece, a ravishing, eight-year-old [sic] child with blond hair and astonishing large blue eyes. You see from this what he could do with the elements and the talent with which you are familiar.” Cited in Sona Johnston, Faces of Impressionism: Portraits from American Collections, exh. cat. (Baltimore: Baltimore Museum of Art, 1999), 112.

-

According to Susan Vincent, “Girls’ gloves, like mini versions of womens’, came in wool, kid and silk.” The second-skin fit, solidity, and gray color lead me to suggest that Lise’s gloves are kid leather. Susan J. Vincent, “Gloves in the Early Twentieth Century: An Accessory After the Fact,” Journal of Design History 25, no. 2 (2012): 191.

-

Vincent, “Gloves in the Early Twentieth Century,” 193.

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Diana M. Jaskierny, “Edouard Manet, Portrait of Lise Campineanu, 1878,” technical entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.524.2088.

MLA:

Jaskierny, Diana M. “Edouard Manet, Portrait of Lise Campineanu, 1878,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.524.2088.

Portrait of Lise Campineanu was completed on a plain-weave canvasplain weave: A basic textile weave in which one weft thread alternates over and under the warp threads. Often this structure consists of one thread in each direction, but threads can be doubled (basket weave) or tripled to create more complex plain weave. Plain weave is sometimes called tabby weave. that corresponds with a standard-size formatstandard-format supports: Commercially prepared supports available through art suppliers, which gained popularity in the nineteenth century during the industrialization of art materials. Available in three formats figure (portrait), paysage (landscape), and marine (marine), these were numbered 1 through 120 to indicate their size. For each numbered size, marine and paysage had two options available: a larger format (haute) and smaller (basse) format. no. 10 figure.1David Bomford, Jo Kirby, John Leighton, and Ashok Roy, Art in the Making: Impressionism (London: Yale University Press, 1991), 46. The canvas is extremely finely woven, similar to other canvases used by Manet throughout his career, including those of The Croquet Party (1871; Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) and White Lilacs in a Crystal Vase (ca. 1882; Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art). Early in the painting’s history, the tacking marginstacking margins: The outer edges of canvas that wrap around and are attached to the stretcher or strainer with tacks or staples. See also tacking edge. were removed and the canvas was linedlining: A procedure used to reinforce a weakened canvas that involves adhering a second fabric support using adhesive, most often a glue-paste mixture, wax, or synthetic adhesive., obscuring the reverse of the painting.2The lining predates the painting’s 1936 acquisition by the Nelson-Atkins, and paper tape covers what remains of the tacking margins. The stretcherstretcher: A wooden structure to which the painting’s canvas is attached. Unlike strainers, stretchers can be expanded slightly at the joints to improve canvas tension and avoid sagging due to humidity changes or aging. does not appear to be original and likely dates to the lining process.

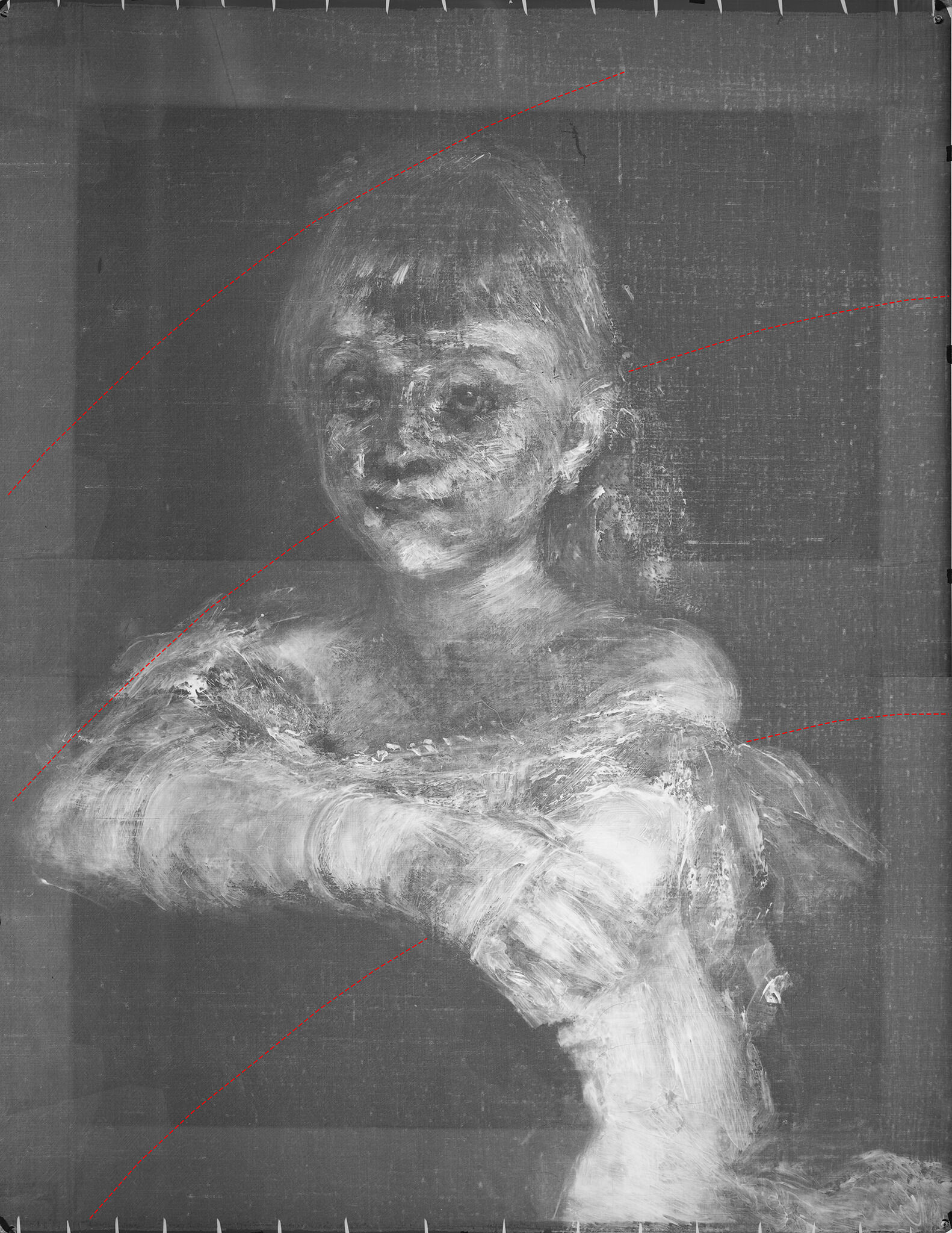

Fig. 6. Radiograph of Portrait of Lise Campineanu (1878). The red dotted line indicates the path of diagonal striations likely caused by a spatula during the ground layer application.

Fig. 6. Radiograph of Portrait of Lise Campineanu (1878). The red dotted line indicates the path of diagonal striations likely caused by a spatula during the ground layer application.

Fig.7. Detail of radiograph from the upper left corner of Portrait of Lise Campineanu (1878). The contrast and exposure of the image have been digitally adjusted in order to enhance the appearance of the striations.

Fig.7. Detail of radiograph from the upper left corner of Portrait of Lise Campineanu (1878). The contrast and exposure of the image have been digitally adjusted in order to enhance the appearance of the striations.

Fig. 9. Reflected infrared digital photograph of Portrait of Lise Campineanu (1878). The brown background layer with blue and brown pigments appears darker in infrared imaging than the lower brown underpaint, which is mostly visible in the top right quadrant.

Fig. 9. Reflected infrared digital photograph of Portrait of Lise Campineanu (1878). The brown background layer with blue and brown pigments appears darker in infrared imaging than the lower brown underpaint, which is mostly visible in the top right quadrant.

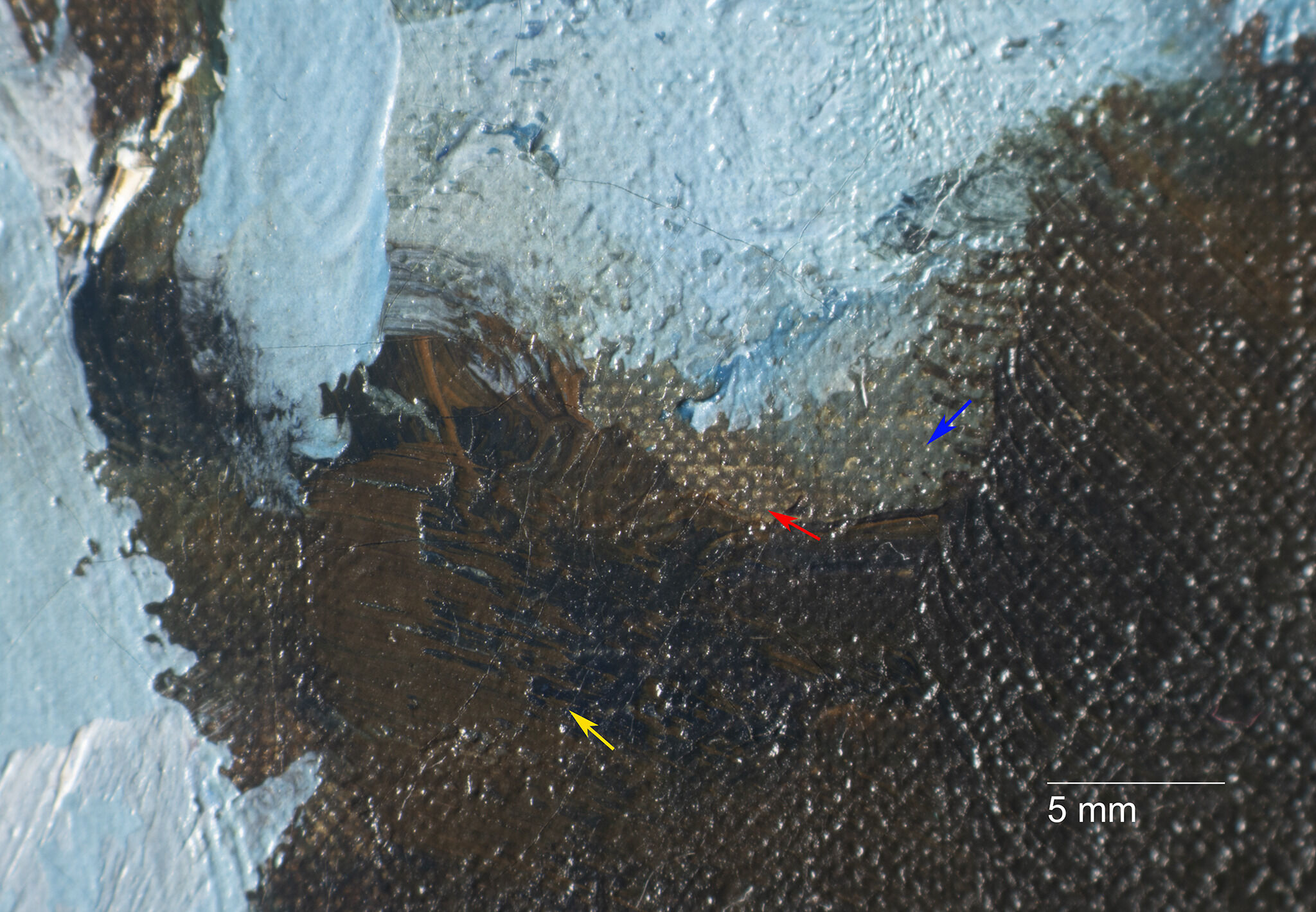

Fig. 10. Photomicrograph of Portrait of Lise Campineanu (1878), detailing the double paint bead along the right edge of the picture plane from when Manet scraped the edges to form a border

Fig. 10. Photomicrograph of Portrait of Lise Campineanu (1878), detailing the double paint bead along the right edge of the picture plane from when Manet scraped the edges to form a border

Fig. 12. Detail of the proper right shoulder of Portrait of Lise Campineanu (1878). Wet-into-wet paint application forms the proper left hand resting on the arm.

Fig. 12. Detail of the proper right shoulder of Portrait of Lise Campineanu (1878). Wet-into-wet paint application forms the proper left hand resting on the arm.

Fig. 13. Detail of the sitter’s face in Portrait of Lise Campineanu (1878). Exposed ground is visible around the eyes, nose, and mouth.

Fig. 13. Detail of the sitter’s face in Portrait of Lise Campineanu (1878). Exposed ground is visible around the eyes, nose, and mouth.

Only one element clearly reveals that this portrait was not completed in one painting session. Once the painting had dried, Manet revisited the profile of the sitter’s right hand and dress where they meet the chair. Originally, the hand and some of the dress seem to have extended over and around the top of the chair. This was revised so that the chair was widened, creating a more continuous arching line. This artist change is visible both in the x-radiograph and normal viewing light, where blues of the dress and peach skin tone are clearly visible beneath overlying brushstrokes and drying cracks (Fig. 16).

Fig. 15. Photomicrograph of Portrait of Lise Campineanu (1878), detailing the proper left eye

Fig. 15. Photomicrograph of Portrait of Lise Campineanu (1878), detailing the proper left eye

Fig. 16. Detail of artist change in the hand of Portrait of Lise Campineanu (1878), with normal view (left) and x-radiograph (right). On the left, the blue dotted line represents the original placement of the hand and dress.

Fig. 16. Detail of artist change in the hand of Portrait of Lise Campineanu (1878), with normal view (left) and x-radiograph (right). On the left, the blue dotted line represents the original placement of the hand and dress.

Notes

-

David Bomford, Jo Kirby, John Leighton, and Ashok Roy, Art in the Making: Impressionism (London: Yale University Press, 1991), 46.

-

The lining predates the painting’s 1936 acquisition by the Nelson-Atkins, and paper tape covers what remains of the tacking margins.

-

Cross-section sampling was not conducted to verify the single ground layer.

-

Manet frequently used the ground layer as a compositional element, as seen in The Croquet Party (1871; Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) and White Lilacs in a Crystal Vase (ca. 1882; Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art).

-

These diagonal striations are subtle and are most easily seen within the top left quadrant. Film-based x-radiograph no. 191, NAMA conservation file, no. 36-5.

-

Bomford et al., Art in the Making: Impressionism, 48–49.

-

Several examples of this can be found in the technical essays of the Art Institute of Chicago catalogue, Manet Paintings and Works on Paper at the Art Institute of Chicago, ed. Gloria Groom and Genevieve Westerby (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2019). One specific example that highlights these marks can be found in Rachel Freeman, “Cat. 18: Portrait of Alphonse Maureau, 1878/79: Technical Report,” in Manet Paintings and Works on Paper at the Art Institute of Chicago, para 21.

-

While artists would sometimes use tape to create crisp edges, in this case paint pressed into the canvas weave interstices indicates that the paint was scraped away from the edges. This technique has been seen on other Manet paintings. See Kimberley Muir, “Cat. 2: Fish (Still Life), 1864: Technical Report,” in Manet Paintings and Works on Paper at the Art Institute of Chicago, para 18.

-

Anne Coffin Hanson, Manet and the Modern Tradition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1977), 160.

-

At least one conservation treatment (lining and likely cleaning) was completed prior to the painting’s acquisition at the Nelson-Atkins. Abrasions in the upper left and right corners are mentioned in the 1986 examination report and are attributed to an earlier cleaning. Scott Heffley, February 4, 1986, examination report, NAMA conservation file, no. 36-5.

-

Scott Heffley, February 25, 1986, treatment report, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, no. 36-5.

-

Scott Heffley, December 8, 2011, treatment report, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, no. 36-5.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Edouard Manet, Portrait of Lise Campineanu, 1878,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.524.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Edouard Manet, Portrait of Lise Campineanu, 1878,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.524.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Edouard Manet, Portrait of Lise Campineanu, 1878,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.524.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Edouard Manet, Portrait of Lise Campineanu, 1878,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.524.4033.

Commissioned from the artist by the sitter’s great-uncle, Dr. Georges de Bellio (né Gheorge Bellu, 1828–94), by August 31, 1878 [1];

His gift to the sitter’s parents, Ion (or Jean, 1841–88) and Irina (née Bellu, 1854–1919) Campineanu, Bucharest, 1878–1919;

By descent to their daughter, the sitter, Mrs. Grégoire Greceanu (née Eliza [or “Lise”] Campineanu, 1872–1949), Bucharest, 1919–at least 1921 [2];

With Eugène Blot, Louis Vauxcelles, and André Schoeller, Paris, by November 18, 1930 [3];

Purchased from Eugène Blot, Louis Vauxcelles, and André Schoeller by Wildenstein, New York, November 18, 1930–January 1, 1936 [4];

Purchased from Wildenstein by the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1936.

Notes

[1] “Manet . . . a fait le portrait de ma petite-nièce, ravissante enfant de huit [sic] ans avec des cheveux blonds et de grands yeux bleus étonnés et étonnants.” Letter from Georges de Bellio to Claude Monet, August 31, 1878, private collection, cited in Denis Rouart and Daniel Wildenstein, Edouard Manet: Catalogue raisonné (Lausanne, Switzerland: La Bibliothèque des arts, 1975), 1:226.

[2] See Remus Niculescu, “Georges de Bellio, l’ami des impressionnistes (I),” Paragone: Arte, 21, no. 247 (September 1970): 82, and Remus Niculescu, Georges de Bellio: L’Ami des Impressionnistes (Firenze: Paragone, 1970), 86. Niculescu states that the painting was sold in Paris around 1930, but does not say who sold it.

[3] Eugène Blot (1857–1938) owned a gallery at 5 Boulevard de la Madeleine. Louis Vauxcelles (né Mayer, 1870–1943) was an art critic who coined the term “Les Fauves” in 1905. André Schoeller (1879–1955) was an expert in French nineteenth-century painting, who in 1947 was arrested for his collaboration with the Nazis. Schoeller sold several works on behalf of the De Bellio extended family in the 1930s.

[4] See email from Sophie Pietri, Wildenstein Institute, Paris, to Meghan Gray, NAMA, July 22, 2011, NAMA curatorial files. Pietri also confirmed that “Wildenstein and Co., Inc. NY” bought the painting rather than Georges Wildenstein, who is listed as the buyer in Tabarant 1931. See email from Sophie Pietri, Wildenstein Institute, Paris, to Meghan Gray, NAMA, November 4, 2011, NAMA curatorial files.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Edouard Manet, Portrait of Lise Campineanu, 1878,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.524.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Edouard Manet, Portrait of Lise Campineanu, 1878,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.524.4033.

Edouard Manet, Little Girl in an Armchair: Portrait of Lise Campineanu, 1878, oil on canvas transferred to hardboard, 21 11/16 x 18 1/4 in. (55.2 x 46.4 cm), Spencer Museum of Art, Lawrence, KS. Gift of Charles Curry, 1958.0121

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Edouard Manet, Portrait of Lise Campineanu, 1878,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.524.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Edouard Manet, Portrait of Lise Campineanu, 1878,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.524.4033.

Manet and Renoir, Pennsylvania Museum of Art, Philadelphia, November 29, 1933–January 1, 1934, unnumbered, erroneously as Portrait of Mlle. Bellio.

One Hundred Years of French Painting 1820–1920, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, March 31–April 28, 1935, no. 33, erroneously as Portrait of Lina Campineanu.

Edouard Manet, 1832–1883: a retrospective loan exhibition for the benefit of the French Hospital and the Lisa Day Nursery, Wildenstein and Co., New York, March 19–April 17, 1937, no. 23, erroneously as Portrait de Line Campineanu (Portrait of Line Campineanu).

Five Years of Collecting, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, December 4–11, 1938, no cat., erroneously as Portrait of Lina Campineanu.

The Child through Four Centuries: Portraits of Children, 17th to 20th centuries; for the benefit of the Public Education Association, Wildenstein and Co., New York, March 1–March 28, 1945, no. 31, erroneously as Portrait of Lina Campineanu.

Portrait Panorama: An Exhibition of Portraits by Artists of Six Centuries, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, September 10–October 12, 1947, no. 17, erroneously as Lina Campineanu.

A Loan Exhibit of Manet for the Benefit of the New York Infirmary, Wildenstein and Co., New York, February 26–April 3, 1948, no. 21, erroneously as Portrait of Line Campineanu.

Forerunners of Modern Painting, Albright Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY, March 23–April 10, 1952, no cat., erroneously as Portrait of Line Campineanu.

Paintings, Drawings and Graphic Works by Manet, Degas, Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt, Baltimore Museum of Art, April 18–June 3, 1962, no. 6, erroneously as Portrait of Line Campineanu.

Édouard Manet, 1832–1883, Philadelphia Museum of Art, November 3–December 11, 1966; Art Institute of Chicago, January 13–February 19, 1967, no. 151, erroneously as Line de Bellio or Line Campineanu (Fillette à mi-corps).

Faces from the World of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism: A Loan Exhibition for the Benefit of the New York Chapter of the Arthritis Foundation, Wildenstein and Co., New York, November 2–December 9, 1972, no. 39, as Lise Campineanu.

Edouard Manet, Isetan Museum of Art, Tokyo, June 26–July 29, 1986; Fukuoka Art Museum, August 2–31, 1986; Osaka Municipal Museum of Art, September 6–October 12, 1986, no. 23, as Portrait of Lise Campineano [sic].

Impressionism: Selections From Five American Museums, The Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, November 4, 1989–December 31, 1990; The Minneapolis Institute of Arts, January 27–March 25, 1990; The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, April 21–June 17, 1990; The Saint Louis Art Museum, July 14–September 9, 1990; The Toledo Museum of Art, OH, September 30–November 25, 1990, no. 44, as Portrait of Lise Campineanu.

Faces of Impressionism: Portraits from American Collections, Baltimore Museum of Art, October 10, 1999–January 30, 2000; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, March 15–May 7, 2000; Cleveland Museum of Art, May 27–July 30, 2000, no. 37, as Portrait of Lise Campinéanu [sic].

Manet: Portraying Life, Toledo Museum of Art, October 7, 2012–January 1, 2013; Royal Academy of Arts, London, January 26–April 14, 2013, no. 48, as Portrait of Lise Campinéanu [sic].

Manet—Sehen Der Blick Der Moderne, Hamburger Kunsthalle, May 27–September 4, 2016, no. 31, as Portrait de Lise Campinéanu [sic] and Porträt Lise Campinéanu [sic].

References

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Edouard Manet, Portrait of Lise Campineanu, 1878,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.524.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Edouard Manet, Portrait of Lise Campineanu, 1878,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.524.4033.

Claymoor [Mihail Văcărescu], “Échos Mondains,” L’Indépendance Roumain 5, no. 27 (January 1882).

Léon Leenhoff, “Manet [ensemble de notes et de documents sur le peintre; recueillis et transcrits par Léon Leenhoff],” 1900–1910, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, département Estampes et photographie, RESERVE 8-YB3-2401, p. 76, as Portrait enfant.

Possibly Ioan Câmpineanu-Cantemir, Dosarul de partaj no. 1276/921 la Tribunalul Ilfov, secţia IV-a civ. cor.. Iunie 1921–Aprilie 1923. Partea 2, Partea 2 (Bucharest: Tipografia Profesională Dimitrie C. Ionescu, 1923), 46.

A[dolphe] Tabarant, Manet: Histoire catalographique (Paris: Éditions Montaigne, 1931), no. 294, pp. 341–42, as Fillette à mi-corps.

Edmond Jaloux, “Le Tragique de Manet,” Formes, no. 24 (April 1932): (repro.), erroneously as Portrait de Mlle de Bellio.

A[dolphe] Tabarant, “À propos de la Rétrospective de Manet à l’Orangerie,” La Renaissance, no. 7–9 (July–September 1932): 139, (repro.), as Portrait de Fillette.

Paul Jamot and Georges Wildenstein, Manet (Paris: Beaux-arts, édition d’études et de documents, 1932), no. 286, pp. 1:155, 2:99, (repro.), erroneously as Portrait de Line Campineanu.

“Manet and Renoir,” exh. cat., Bulletin of the Pennsylvania Museum 29, no. 158 (December 1933): 19, erroneously as Portrait of Mlle de Bellio.

“Manet and Renoir,” Art Digest 8, no. 6 (December 15, 1933): 9, (repro.), erroneously as Portrait of Mlle. de Bellio.

One Hundred Years: French Painting 1820–1920, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: C.E. Brown, 1935), unpaginated, erroneously as Portrait of Lina Campineanu.

M[inna] K. P[owell], “In Gallery and Studio: News and Views of the Week in Art,” Kansas City Star 55, no. 186 (March 22, 1935): [E].

M[inna] K. P[owell], “In Gallery and Studio: News and Views of the Week in Art,” Kansas City Star 55, no. 193 (March 29, 1935): unpaginated, erroneously as Portrait of Lina Campineanu.

“Important Exhibition of French Painting,” News Flashes (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) 1, no. 9 (March 31–April 20, 1935): 1, erroneously as Portrait of Lina Campineanu.

“Art News,” Kansas City Journal-Post, no. 190 (March 31, 1935): 8-B, erroneously as Portrait of Lina Campineanu.

“2,000 See Loan Display: Many Masterly Works Are Shown at the Gallery,” Kansas City Times 98, no. 78 (April 1, 1935): 8.

Art News 33 (April 6, 1935): 3, (repro.), erroneously as Portrait de Mlle. Bellio.

“Art News,” Kansas City Journal-Post, no. 197 (April 7, 1935): 8-B, erroneously as Portrait of Lina Campaineanu [sic].

“Wilmington Sees Old Masters’ Art: Exhibition Is Chief Feature of Week’s Observance—Beaux Arts Ball Tomorrow. Show At Everbrook, PA. Philadelphia Artists' Work Is on View—French Paintings Are Shown at Kansas City,” New York Times 84, no. 28,202 (April 12, 1935): L21.

“French Paintings Favored in Popular Vote Here,” Kansas City Star 55, no. 209 (April 14, 1935): 6, (repro.).

“Art News,” Kansas City Journal-Post 81, no. 211 (April 21, 1935): 8B, erroneously as Lina Campineaunu [sic].

M[inna] K. P[owell], “In Gallery and Studio: News and Views of the Week in Art,” Kansas City Star 55, no. 221 (April 26, 1935): 15, erroneously as Portrait of Lina Campineanu.

“French Loan Exhibition Last Call,” News Flashes (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) 1, no. 10 (April 21–May 3, 1935): 1, erroneously as Portrait of Lina Campineanu.

“The Fine Arts,” Musical Bulletin 23, no. 8 (May 1935): 13.

“Manet Portrait,” News Flashes (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) 2, no. 5 (January 16–31, 1936): 2, erroneously as Portrait of Lina Campineanu.

M[inna] K. P[owell], “In Gallery and Studio: News and Views of the Week in Art,” Kansas City Star 56, no. 129 (January 24, 1936): unpaginated.

“Portrait by Manet Chosen as Week’s Nelson Gallery Masterpiece,” Kansas City Journal-Post 82 (January 26, 1936): 2-B, (repro.), erroneously as Portrait of Lina Campineanu.

“Manet, Clouet, Lorenzo Monaco, Paintings Newly Acquired by the Nelson Galleries in Kansas City,” Art News 34, no. 20 (February 15, 1936): 5, (repro.), erroneously as Portrait of Mme. Line Campineanu.

“Out of Town Visitors,” News Flashes (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) 2, no. 8 (March 15–31, 1936): 4, erroneously as Portrait of Line Campineanu.

“One of the most important purchases,” Musical Bulletin 24, no. 6 (March 1936): 11, erroneously as Lina Campineanu.

“Out of Town Visitors,” News Flashes (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) 2, no. 8 (March 15–31, 1936): 4, erroneously as Portrait of Line Campineaunu [sic].

Helen Comstock, “The Connoisseur in America,” Connoisseur (May 1936): 282–83, (repro.), erroneously as Portrait of Line Campineau [sic] as a Child.

“Local Museums, Art Associations, and Other Organizations,” American Art Annual 33, For the Year 1936 (1937): 239, erroneously as Portrait of Lina Campineanu.

Paul Jamot, Édouard Manet, 1832–1883: A Retrospective Loan Exhibition for the Benefit of the French Hospital and the Lisa Day Nursery, exh. cat. (New York: Wildenstein, 1937), 36, 69 (repro.), erroneously as Portrait de Line Campineanu (Portrait of Line Campineanu).

Edward Alden Jewell, “Manet Exhibition Will Open Today,” New York Times 86, no. 28,909 (March 19, 1937): 21.

Paul Gardner, “New Prize in Cezanne Landscape Acquired by the Nelson Gallery: ‘La Montagne Sainte-Victoire’ Is Exhibited as the Masterpiece for the Month—French Painter’s Unique Contribution to Art is Represented Dramatically in hitherto Unknown Canvas Added to Kansas City’s Permanent Collection,” Kansas City Star 58, no. 169 (March 5, 1938): D, erroneously as Lina Campineaunu [sic].

“Nelson Gallery’s Masterpiece of the Month: Cezanne Landscape Year’s First Purchase at Nelson Art Gallery,” Kansas City Journal-Post, no. 165 (March 6, 1938): 4-B, erroneously as Lina Campineaunu [sic].

H.C.H, “Five 1-Man Art Shows; Diversification and Interest in April Loan Exhibition; The Nelson Gallery Displays Works of Jon Corbino, Waldo Pierce, Reginald Marsh, Sidney Laufman, and Frederic Taubes,” Kansas City Star 58, no. 198 (April 3, 1938): 12A, erroneously as Lina Campineanu.

“Museum Directors Have to Play Detective Now and Then,” Kansas City Star 58, no. 210 (April 15, 1938): 14.

“‘Visit Your Gallery Week’ Designated December 4–11,” Kansas City Journal, no. 66 (November 27, 1938): 36, erroneously as Lina Campineaunu [sic].

“Five Years of Collecting,” News Flashes (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) 5, no. 2 (December 1, 1938): 1, erroneously as Lina Campineaunu [sic].

“Footnotes,” Evening State Journal (Lincoln, NE) (December 2, 1938): 8.

H. C. H., “Art and Artists: The Nelson Gallery Reflects the Spirit of a Modern Medici—The Gallery’s Fifth Anniversary Recalls its Founder’s Resemblance to a Great Florentine Patron of the Arts—Two Shows Begin Sunday,” Kansas City Star 59, no. 76 (December 2, 1938): 19, (repro.), erroneously as Portrait of Lina Campineaunu [sic].

Paul Gardner, “Kansas City: Jubilee and an Acquisition,” Art News 37, no. 10, Special Issue for the “1870s” Exhibition: From Greco to Goya in London, Kansas City Jubilee (December 3, 1938): 19, (repro.), erroneously as Portrait of Lina Campineanu.

Kansas City Journal, no. 73 (December 4, 1938): unpaginated, (repro.), erroneously as Portrait of Lina Campineau.

“A Good Start on Art: Paintings of Nelson Gallery Are Described by Advisor,” Kansas City Times 101, no. 299 (December 15, 1938): 6.

“Kansas City’s Nelson Gallery Celebrates its Fifth Anniversary,” Art Digest 13, no. 6 (December 15, 1938): 7, erroneously as Lina Camineaunu [sic].

H.C.H., “Art and Artists: Gallery’s New Credi Shows Greatness of Florentine,” Kansas City Star 59, no. 167 (March 3, 1939): 15, erroneously as Portrait of Lina Campineanu.

Landon Laird, “About Town,” Kansas City Times 103, no. 253 (October 21, 1940): 6, erroneously as Lina.

H.C.H., “Art and Artists: American Art Gets Surveyed By the Carnegie Institute; Pittsburgh’s Home of International Shows Goes Native This Year—‘Susanna’ Is Given to San Francisco,” Kansas City Star 61, no. 45 (November 1, 1940): 20.

The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, The William Rockhill Nelson Collection, 2nd ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1941), 41, 51, (repro.), erroneously as Portrait of Lina Campineanu.

“Nelson Gallery Celebrates First Decade,” Art Digest 18, no. 6 (December 15, 1943): 6–7, (repro.), erroneously as Portrait of Lina Campineau.

Ethlyne Jackson, “Museum Record: Kansas City’s Tenth Birthday,” Art News 42, no. 15, (December 15–31, 1943): 16, 19, (repro.), erroneously as Portrait of Line Campineanu.

Edward Jewell and Aimée Crane, French Impressionists and their Contemporaries Represented in American Collections (New York: Hyperion Press, 1944), 5, 75, (repro.), erroneously as Portrait of Lina Campineanu.

The Child through Four Centuries: Portraits of Children, 17th to 20th Centuries, exh. cat. (New York: Wildenstein, 1945), unpaginated, (repro.), erroneously as Portrait of Lina Campineanu.

Edward Alden Jewell, “The Child in Art: The Benefit Exhibition at Wildenstein’s Portrays Youth Through Centuries,” New York Times 94, no. 31,816 (March 4, 1945): 8X, erroneously as Portrait of Lina Campineanu.

“Loans,” Gallery News (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) 13, no. 10 (October 1947): unpaginated, erroneously as Line Campineanu.

Fred G Hoffherr, ed., Book of Friendship: le livre de l’amité (New York: La Maison de France, 1947), unpaginated, (repro.), erroneously as Portrait de Line Campineanu.

A[dolphe] Tabarant, Manet et ses œuvres, 5th ed. (Paris: Gallimard, 1947), no. 309, pp. 334–35, 541, 612, (repro.), as Fillette à mi-corps.

Portrait Panorama: An Exhibition of Portraits by Artists of Six Centuries, exh. cat. (Richmond, VA: Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, 1947), unpaginated, erroneously as Lina Campineanu.

Dorothy Adlow, “Art in Kansas City—Music and Theaters—Exhibitions in San Francisco: Masterpieces of Many Schools To Be Seen in Nelson Gallery,” Christian Science Monitor 40, no. 197 (July 17, 1948): 4C, as Portrait of a Little Girl.

A Loan Exhibition of Manet for the Benefit of the New York Infirmary, exh. cat. (New York: Wildenstein, 1948), 56–57, (repro.), erroneously as Portrait of Line Campineanu.

Aline B. Louchheim, “Children Should Be Seen,” Art News Annual 46, no. 9 (1948): 74, 137, (repro.), erroneously as Line Campineanu.

“Manet Art Works Go On View Tonight: Notable Paintings Included in Display at Wildenstein Infirmary Here to Gain,” New York Times 97, no. 32,904 (February 25, 1948): L21.

“Loans to Special Exhibitions,” Gallery News (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) 14, no. 5 (March 1948): unpaginated, erroneously as Portrait of Line Campineaunu [sic].

Art in America (April 1948): (repro.), erroneously as Line Campineanu.

“Gallery Notes,” Gallery News (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) 14, no. 7 (May 1948): unpaginated, erroneously as Line Campineanu.

“Special Exhibitions,” Gallery News (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Art) 15, no. 7 (April 1949): unpaginated, erroneously as Portrait of Line Campineanu.

“Art and Artists: New Wing of Nelson Gallery To Be Opened to Public Sunday; Roman Portrait Busts, Medieval Sculpture, Chinese Paintings Among New Acquisitions—North Loan to Feature Outstanding Pieces of European Works,” Kansas City Star 69, no. 196 (April 1, 1949): 29, erroneously as Portrait of Lina Campineanu.

The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, The William Rockhill Nelson Collection, 3rd ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1949), 65, (repro.), erroneously as Portrait of Line Campineanu.

Alice Elizabeth Chase, Famous Paintings: an Introduction to Art for Young People (New York: Platt and Munk, 1951), 82, (repro.), erroneously as Portrait of Line Campineanu.

Raymond Cogniat, French Painting at the Time of the Impressionists, trans. Lucy Norton (New York: Hyperion, 1951), 29, (repro.), erroneously as Portrait of Lina Campineanu.

P[atrick] J. K[elleher], “Forerunners of Modern Painting,” Gallery Notes (The Buffalo Fine Arts Academy, Albright Art Gallery) 16, nos. 2–3 (May–October 1952): 11, 14, (repro.), erroneously as Portrait of Line Campineanu.

Aline B. Louchheim, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Miniatures: Children in Art (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1953), unpaginated, (repro.), erroneously as Line Campineau [sic].

“New Acquisition,” Gallery News (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) 22, no. 8 (May 1955): unpaginated, (repro.), erroneously as Portrait of Line Campineanu.

Isabel Stevenson and Kate M. Monro, Index to Reproductions of European Paintings; A Guide to Pictures in More Than Three Hundred Books (New York: Wilson, 1956), 99, 372, erroneously as Lina Campineanu.

Ross E. Taggart, “Kansas City Art,” Library Journal 82, no. 12 (June 15, 1957): 1596.

“Open House for New K.U. Art,” Kansas City Times 122, no. 46 (February 23, 1959): 9.

Ross E. Taggart, ed., Handbook of the Collections in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 4th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of fine Arts, 1959), 121, 261, (repro.), erroneously as Portrait of Line Campineanu.

The American Library Compendium and Index of World Art; Architecture, Sculpture, Painting, and the Minor Arts As Compiled from the Archives of the American Library of Color Slides (New York: American Archives of World Art, 1961), 150, erroneously as Portr. of Line Campineanu.

Estere Rubin, “If at First You Don’t Succeed,” Kansas City Star 82, no. 353 (September 5, 1962): 10F, (repro.).

Robert K. Sanford, “Stolen Manet Is of Academic Value,” Kansas City Star 82, no. 357 (September 9, 1962): 11D.

Alice Elizabeth Chase, Famous Paintings: An Introduction to Art (New York: Platt and Munk, 1962), 52, (repro.), erroneously as Portrait of Line Campineanu.

Pierre Courthion, Edouard Manet (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1962), 21, (repro.), erroneously as Portrait of Line Campineanu.

Paintings, Drawings and Graphic Works by Manet, Degas, Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt, exh. cat. (Baltimore: Baltimore Museum of Art, 1962), 20, 45, 51, (repro.), erroneously as Portrait of Line Campineanu.

“Lost K.U. Art Work Is Found: FBI Recovers the $40,000 Manet Painting in Los Angeles,” Kansas City Times 126, no. 13 (January 15, 1963): 1.

Margaret Harold and Gus Baker, Portraits by the Masters (Fort Lauderdale, FL: Allied, 1963), P-26, (repro.), erroneously as Portrait of Line Campineanu.

Remus Niculescu, Georges de Bellio, l’ami des impressionnistes: Tirage à Part de la ‘Revue Roumaine d’Histoire de l’Art’, Tome 1, No 2 ([Bucarest]: Éditions de l’Académie de la République Socialiste de Roumaine, 1964), 220–21, 277, (repro.), as Portrait de Lise Campineano [sic].

Marilyn Stokstad, ed., Images: 23 Interpretations, exh. cat. (Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Museum of Art, 1964), 31.

“Rare Pot Is Stolen From Folger Show,” Kansas City Times 98, no. 21 (October 1, 1965): 3A.

Henry C. Haskell, “Scanning the Arts,” Kansas City Star 86, no. 72 (November 28, 1965): [1]F.

Anne Coffin Hanson, Édouard Manet 1832–1883, exh. cat. (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1966), 164–65, (repro.), erroneously as Line de Bellio or Line Campineanu (Fillette à mi-corps).

George Heard Hamilton, “Is Manet still ‘Modern’?,” Art News Annual 31 (1966): 125, (repro.), erroneously as Line Campineanu.

Martha Schmierer and Richard Verdi, “Some Thoughts Arising from the Philadelphia-Chicago Manet Exhibition,” Art Quarterly (Fall–Winter 1967): 243.

Sandra Orienti, The Complete Paintings of Manet (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1967), no. 255A, pp. 108–09, (repro.), erroneously as Fillette à Mi-Corps (Line Campineanu) (Half-Length Portrait of a Little Girl).

Remus Niculescu, “Georges de Bellio: L’Ami des Impressionnistes,” Paragone 21, no. 247 (September 1970): 40, 81–82, (repro.) [repr. in, Remus Niculescu, Georges de Bellio: L’Ami des Impressionnistes (Florence: Paragone, 1970), 18, 40n59, 85–86], as Portrait de Lise Campineanu.

Sandra Orienti, The Complete Paintings of Manet (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1970), no. 255A, pp. 108–09, (repro.), erroneously as Fillette à Mi-Corps (Line Campineau) (Half-Length Portrait of a Little Girl).

Marion Downer, Children in the World’s Art (New York: Lothrop, Lee, and Shepard, 1970), 114–15, (repro.), erroneously as Portrait of Line Campineanu.

Randolph A. Youle et al., From the collection of the University of Kansas Museum of Art, exh. cat. (Houston: Museum of Fine Arts Houston, 1971), unpaginated.

“Indomitable Innovation: Influence of Edouard Manet on Modern painting,” MD: Medical Newsmagazine 15, no. 9, (September 1971): 132, (repro.), erroneously as Portrait of Line Campineanu.

Ellen Goheen, “From Romanticism to Pop,” Apollo 96, no. 130 (December 1972): 77, (repro.), erroneously as Portrait of Line Campineanu.

Anne Poulet, Faces from the World of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism: A Loan Exhibition for the benefit of The New York Chapter of The Arthritis Foundation, exh. cat. (New York: Wildenstein, 1972), unpaginated, (repro.), as Lise Campineanu.

John Rewald, The History of Impressionism, 4th rev. ed. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1973), 421, (repro.), as Lise Campineanu.

Ross E. Taggart and George L. McKenna, eds., Handbook of the Collections in The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Kansas City, Missouri, vol. 1, Art of the Occident, 5th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1973), 161, (repro.), as Portrait of Lise Campineanu.

Denis Rouart and Daniel Wildenstein, Edouard Manet: Catalogue raisonné, vol. 1, Peintures (Lausanne, Switzerland: La Bibliothèque des arts, 1975), no. 284, pp. 226–27, (repro.), as Portrait de Lise Campinéano [sic].

“The Fourth Annual Joseph S. Atha Lecture: ‘The Part or the Whole: Manet, Degas and the Transformation of Space in Painting,’ Anne Coffin Hanson, Ph.D., John Hay Whitney Professor, Yale University,” Kansas City Times 118, no. 51 (November 6, 1985): A-2, (repro.), as Portrait of Lise Campineanu.

Charles F. Stuckey and Juliet Wilson Bareau, Edouard Manet, exh. cat. (Tokyo: Art Life, 1986), 59, 159, (repro.), as Portrait of Lise Campineano (Portrait de Lise Campineano) [sic].

Marc S. Gerstein, Impressionism: Selections from Five American Museums, exh. cat. (New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1989), 110–11, (repro.), as Portrait of Lise Campineanu.

Anne Distel, Impressionism: The First Collectors, trans. Barbara Perroud-Benson (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1990), 115, as Portrait of Lise Campineanu.

Bernard Denvir, Chronicle of Impressionism: An Intimate Diary of the Lives and World of the Great Artists (London: Thames and Hudson, 1993), 279.

Roger Ward and Patricia J. Fidler, eds., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collection (New York: Hudson Hills Press, in association with Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1993), 208, (repro.) as Portrait of Lise Campineanu.

Toledo Treasures: Selections from the Toledo Museum of Art, exh. cat. (Toledo, OH: Toledo Museum of Art, 1995), 21, (repro.).

Sona Johnston, Faces of Impressionism: Portraits from American Collections, exh. cat. (New York: Rizzoli International, 1999), 112–13, (repro.) as Portrait of Lisa Campinéanu [sic].

“Know Your Museum Tour,” Newsletter (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (Summer 2002): 8, (repro.), as Portrait of Lise Campineanu.

Marco Goldin, L’Impressionismo e l’età di Van Gogh, exh. cat. (Treviso, Italy: Fondazione Cassamarca/Casa dei Carraresi, 2002), 482.

“The Past Updated: Aspects of Manet’s Realism,” Newsletter (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (March–April 2004): 4, (repro.), as Portrait of Lise Campineanu.

Marianne Delafond, À l’apogée de l’impressionnisme: La collection Georges de Bellio, exh. cat. (Lausanne, Switzerland: La Bibliothèque des Arts, 2007), 32.

Deborah Emont Scott, ed., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collection, 7th ed. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2008), XII, 119, (repro.), as Portrait of Lise Campineanu.

MaryAnne Stevens et al., Manet: Portraying Life, exh. cat. (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2012), 125, 142, 196, (repro.), as Portrait of Lise Campinéanu [sic].

“First major exhibition to showcase Manet’s portraiture opens at the Royal Academy,” artdaily.org (January 26, 2013): https://artdaily.cc/news/60356/First-major-exhibition-to-showcase-Manet–146-s-portraiture-opens-at-the-Royal-Academy-of-Arts#.XxhrAqaWy0E, (repro.), as Portrait of Lise Campineanu.

Nicholas Wadley, “Faces in the crowd: A few of Manet’s majestic portraits shine through an uneven exhibition,” Times Literary Supplement (London), no. 5733 (February 15, 2013): 20.

Catherine Futter et al., Bloch Galleries: Highlights from the Collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2016), 71, (repro.), as Portrait of Lise Campineanu.

Hubertus Gaßner and Viola Hildebrand-Schat, eds., Manet—Sehen Der Blick Der Moderne, exh. cat. (Petersberg, Germany: Michael Imhof Verlag, 2016), 158, 160, 162, 166n13, (repro.), as Portrait de Lise Campinéanu [sic] and Porträt Lise Campinéanu [sic].