![]()

Charles-Émile Jacque, Sheep at the Watering Hole, ca. 1888

| Artist | Charles-Émile Jacque, French, 1813–94 |

| Title | Sheep at the Watering Hole |

| Object Date | ca. 1888 |

| Alternate and Variant Titles | Moutons a L’abreuvoir; Sheep |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (Unframed) | 29 1/8 x 39 15/16 in. (74 x 101.4 cm) |

| Signature | Signed lower left: Ch. Jacque |

| Credit Line | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 31-88 |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Simon Kelly, “Charles-Émile Jacque, Sheep at the Watering Hole, ca. 1888,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.520.5407.

MLA:

Kelly, Simon. “Charles-Émile Jacque, Sheep at the Watering Hole, ca. 1888,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.520.5407.

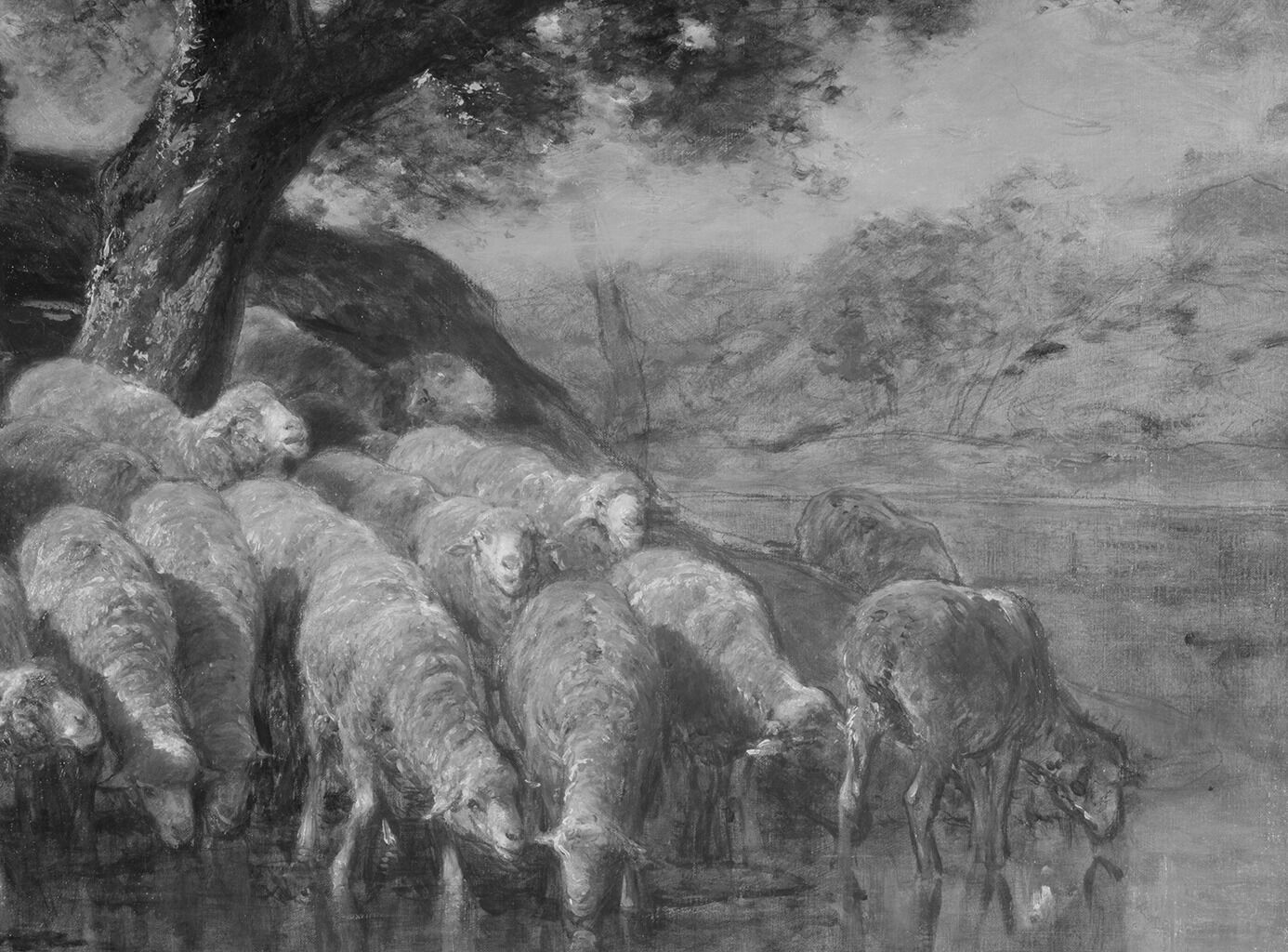

Sheep at the Watering Hole exemplifies Charles-Émile Jacque’s abilities as an animal painter, particularly a painter of sheep. A flock of merino sheep gather by the water, their agitated activity contrasting with the relaxed pose of the shepherd and his sheepdog, who rest on a hill to the left. The painting shows Jacque’s preference for a low “sheep’s-eye view” and his ability to render the range of attitudes of the sheep, even to suggest their character. A few sheep look directly at the spectator while others drink eagerly at the pool. The picture also demonstrates Jacque’s facility in landscape painting, evident in his rendering of textured tree foliage, the sheen of the water surface, and the play of light falling through the trees onto the backs of the sheep.

The scene here probably takes place alongside one of the ponds in the forest of Fontainebleau, the locale that dominated Jacque’s oeuvre. Jacque was an integral member of the community of painters centered in the nearby village of BarbizonBarbizon School: A group of French artists, who united around 1830 to form the Barbizon School, which was named after a small village thirty miles northwest of Paris, where they lived and painted. Rebelling against the French Academy’s refined, idealized landscapes, these artists infused the immediacy of the sketches they created outdoors into their finished studio paintings., about thirty miles southeast of Paris, from the late 1840s until the mid 1860s. Jacque first came to Barbizon in 1848 to escape a cholera outbreak in Paris, encouraging the painter Jean-François Millet (1814–75) to come with him. In the years thereafter, Jacque maintained a house and studio in the village, as well as acquiring much land. He became a prominent figure in the business of the village, buying and renting property, raising hens and chickens, and cultivating an asparagus plantation. By 1867, however, he had sold all of his property at Barbizon, moving instead to the village of Annet-sur-Marne, France, and subsequently splitting his time largely between his home there, his large Paris studio, and the town of Pau in the southwest of France, where he often spent winters. Nonetheless, he continued to visit Barbizon, and the environs of the village still inspired his choice of subject matter.1For Jacque’s property sales, see Pierre-Olivier Fanica, Charles Jacque, 1813–1894: Graveur Original et Peintre Animalier (Montigny-sur-Loing: Art Bizon, 1995), 75. Jacque outlived his friends, including artist colleagues Millet and Théodore Rousseau (1812–67), by a considerable number of years and provided an example for a younger generation at Barbizon, including his fellow animalier (animal painter) Ferdinand Chaigneau (1830–1906).

Sheep at the Watering Hole documents a practice of sheep grazing that was theoretically illegal, according to the forest statutes of Fontainebleau.2Greg M. Thomas, Art and Ecology in Nineteenth-Century France: The Landscapes of Théodore Rousseau (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000). Although the residents of Barbizon and nearby Chailly were allowed to graze pigs and cows in the public forest lands, sheep grazing was forbidden.3An edict of 1853 prevented this practice. However, the practice seems, in fact, to have been widespread and generally overlooked by the authorities.4Thomas, Art and Ecology, 155, 159. Large sheep farms and related businesses remained in the area around the forest of Fontainebleau throughout the late nineteenth century.5See Fanica, Charles Jacque, 1813–1894: Graveur Original et Peintre Animalier, 169–70. Despite the complications around sheep grazing, Jacque’s painting can be read as a pastoral image, an evocation of an idyllic and peaceful landscape. Jacque suggests a space of escape, in contrast to the very real precarity of existence for Barbizon shepherds and their flocks.

Jacque’s body of animalier imagery was diverse. He produced numerous images of cows and their cowherds, including The Watering Place, acquired by the French State in 1849 (Musée des Beaux-Arts d’Angers). He also painted many views of hens, chickens, and roosters and knew these animals well; he even wrote a book on the rearing of hens, Le Poulailler: Monographie des Poules Indigènes et Exotiques (The Henhouse: Monograph on Native and Exotic Poultry) (1858). Jacque was, however, particularly known as a painter of sheep. His friend and biographer, Jules Claretie, noted, “Around 1855, and after having fought hard to have his ‘sheep’ accepted, Charles Jacque was as though penned in with them, and the amateurs who love that artists should specialize and who, God knows, are as sheep-like as sheep, compelled him to remain true to this kind of animal.”6“Vers 1855, et après avoir assez âprement lutté pour faire accepter ses moutons, Charles Jacque fut comme parqué avec eux, et ces amateurs encore, qui tiennent si fort à spécialiser les artistes et qui sont aussi moutonniers que les moutons eux-mêmes, lui imposèrent une sorte d’obligation de rester fidèle à ce genre d’animaux.” Jules Claretie, Peintres et Sculpteurs Contemporains, 2nd series (Paris: Librairie des Bibliophiles, 1884), 303. All translations are by the author unless otherwise noted. Jacque thus carefully studied sheep anatomy, making numerous drawings of the ovine form. The Barbizon insider Georges Gassies remembered Jacque’s study, from the early 1850s onward, of the flock of sheep in the large farm belonging to the mayor of Chailly, Benoni Bellon: “The farmer at that time, who called himself Benoni, . . . willingly welcomed artists and was friendly with them, letting them set up their easels in every corner of the large farm, the buildings of which are on the village outskirts, adjoining the beautiful plain of Barbizon. . . . He [Jacque] also used this sheepfold for many of his paintings.”7“le fermier d’alors, qui s’appelait Benoni . . . accueillait volontiers les artistes, se montrait bon camarade avec eux et les laissait installer leur chevalet dans tous les coins de la grande ferme, dont les bâtiments sont à l’extremité du pays, confidant la belle plaine de Barbizon. . . . Il [Charles Jacque] s’est servi aussi de cette bergerie pour beaucoup de ses tableaux.” Georges Gassies, Le Vieux Barbizon: Souvenirs d’un Paysagiste (Paris: Libraire Hachette, 1907); cited in Fanica, Charles Jacque, 1813–1894: Graveur Original et Peintre Animalier, 169.

Jacque had shown prints at the SalonSalon, the: Exhibitions organized by the French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture (Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture) and its successor the Academy of Fine Arts (Académie des Beaux Arts), which took place in Paris from 1667 onward. beginning in 1845, but he first showed his paintings in 1861, when his large-scale view of a shepherd and sheep on the outskirts of the forest of Fontainebleau, Landscape with Flock of Sheep (Musée d’Orsay, Paris), won critical praise, was acquired by the French State, and was subsequently exhibited in the Musée du Luxembourg. Thereafter, he produced extensive views of sheep on the plains and in the woods around Barbizon, earning a reputation as a leading animalier alongside others like Rosa Bonheur (1822–99) and Constant Troyon (1810–65). In 1880, for example, he produced the grand Shepherd and His Flock (Chrysler Museum, Norfolk, VA), exhibited as one of his three pictures at the 1889 Exposition Universelle, where it won him a gold medal. As Claretie noted, he aspired to produce large-scale paintings until his death.8“Il rêve et achève des tableaux agrandis, plus vastes et plus étonnants que jamais” (He dreams and completes enlarged paintings, larger and more astonishing than ever). Jules Claretie, “Introduction,” in Catalogue des Tableaux . . . Composant l’Atelier de Charles Jacque (Paris: Galerie Georges Petit, November 12–15, 1894), 7.

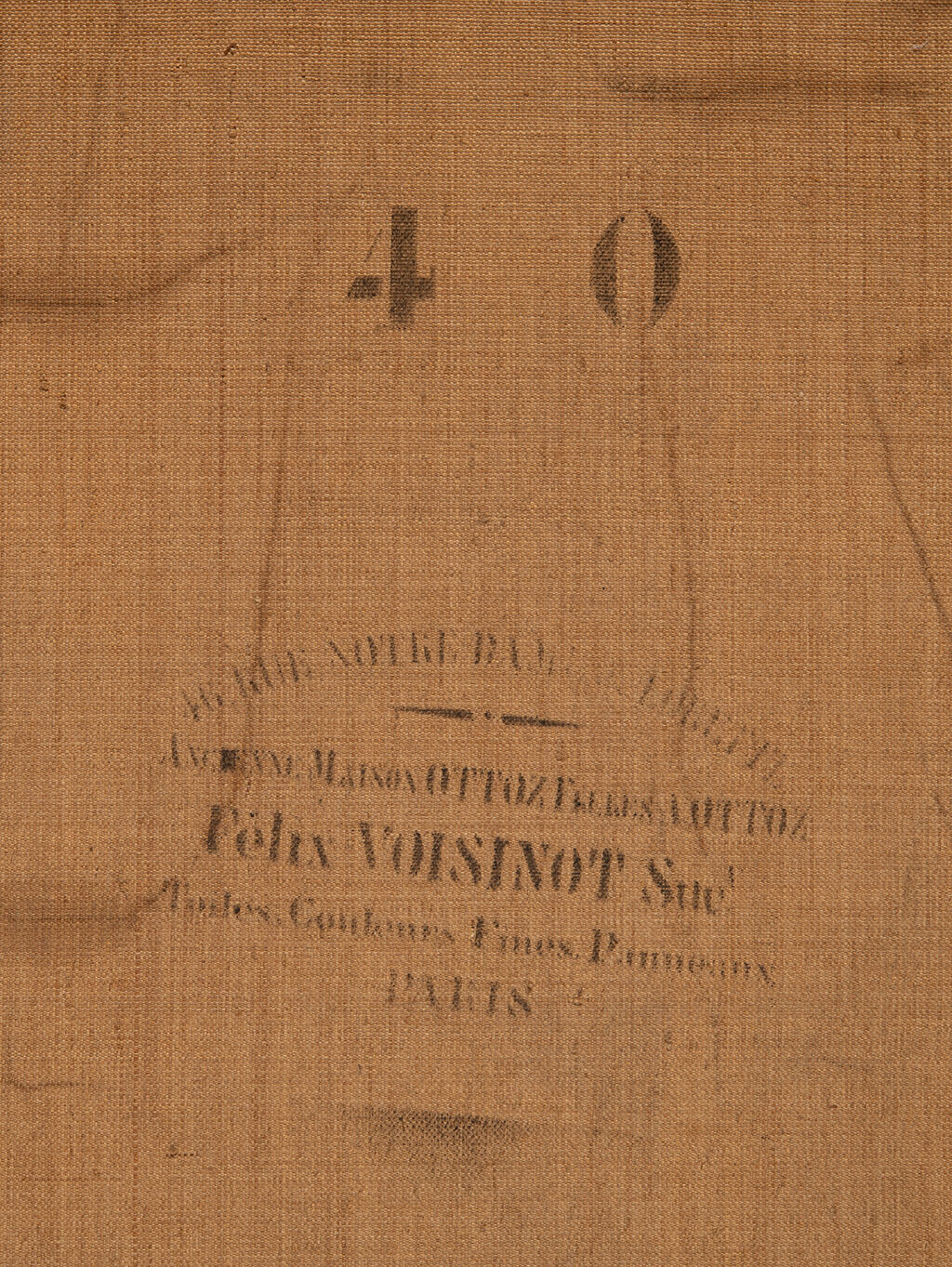

In 1888, he produced a large etching related to the Nelson-Atkins painting, in which he developed an essentially similar composition, although he made subtle changes to the placement of trees, sheep, and shepherd, and added a distant copse of trees. The image was then printed in reverse (Fig. 2).13In Beraldi, Les Graveurs, 8:191, no. 470. Jacque also added two fish on top of one another in a tiny still life in the etching’s border. According to Henri Béraldi’s extensive cataloguing of Jacque’s print oeuvre, this etching was Jacque’s final print. Its size suggests that Jacque also ascribed significance to the Nelson-Atkins canvas. The date of the Nelson-Atkins painting is uncertain. A canvas supplier stamp, belonging to Félix Voisinot, on the painting’s reverse, suggests that the stretcher was purchased between about 1876 and 1881 (see Mary Schafer’s accompanying technical entry). The 1888 date of the related print suggests a comparable date for the painting.

Jacque enjoyed considerable commercial success in his career. Claretie noted that he attracted the prices of the top ten contemporary artists.14“Il a vendu en 1848 dix tableaux pour trois cents francs,—soit trente francs le tableau,—et certaines toiles de lui en valent aujourd’hui trente mille” (In 1848 he sold ten paintings for three hundred francs—that is, thirty francs a painting—and some of his paintings are worth thirty thousand today.) Claretie, Catalogue des Tableaux . . . Composant l’Atelier de Charles Jacque, 6. In the Second EmpireSecond Empire: The regime of Napoléon III in France, which lasted from 1852 to 1870., his work was bought by a range of Rue Laffitte dealers, while the Belgian dealer Gustave Coûteaux particularly favored him. From the 1870s on, American collectors, including Isabella Stewart Gardner and Henry Clay Frick, regularly bought his paintings. The dealers Boussod and Valadon, who were managed by Theo van Gogh, and Paul Durand-Ruel also competed to acquire his work in the 1880s and 1890s. In 1891, the Durand-Ruel gallery even organized an extensive solo exhibition of Jacque’s work.15Exposition de Tableaux, Dessins et Gravures par Ch. Jacque, Galerie Durand-Ruel, Paris, November 15–December 15, 1891. At the same time, they were showing solo exhibitions of the Impressionists, including Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Camille Pissarro. The first known owners of Sheep at the Watering Hole were the dealers Raphaël Gérard and his brother Christian Gérard in 1923. The painting was acquired by several successive dealers in the 1920s before the Nelson-Atkins purchased it in 1931. As a Barbizon painting, it was particularly attractive to the newly formed University Trustees, who were just building the museum’s art collection.

Notes

-

For Jacque’s property sales, see Pierre-Olivier Fanica, Charles Jacque, 1813–1894: Graveur Original et Peintre Animalier (Montigny-sur-Loing: Art Bizon, 1995), 75.

-

Greg M. Thomas, Art and Ecology in Nineteenth-Century France: The Landscapes of Théodore Rousseau (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000).

-

An edict of 1853 prevented this practice.

-

Thomas, Art and Ecology, 155, 159.

-

See Fanica, Charles Jacque, 1813–1894: Graveur Original et Peintre Animalier, 169–70.

-

“Vers 1855, et après avoir assez âprement lutté pour faire accepter ses moutons, Charles Jacque fut comme parqué avec eux, et ces amateurs encore, qui tiennent si fort à spécialiser les artistes et qui sont aussi moutonniers que les moutons eux-mêmes, lui imposèrent une sorte d’obligation de rester fidèle à ce genre d’animaux.” Jules Claretie, Peintres et Sculpteurs Contemporains, 2nd series (Paris: Librairie des Bibliophiles, 1884), 303. All translations are by the author unless otherwise noted.

-

“le fermier d’alors, qui s’appelait Benoni . . . accueillait volontiers les artistes, se montrait bon camarade avec eux et les laissait installer leur chevalet dans tous les coins de la grande ferme, dont les bâtiments sont à l’extremité du pays, confidant la belle plaine de Barbizon. . . . Il [Charles Jacque] s’est servi aussi de cette bergerie pour beaucoup de ses tableaux.” Georges Gassies, Le Vieux Barbizon: Souvenirs d’un Paysagiste (Paris: Libraire Hachette, 1907); cited in Fanica, Charles Jacque, 1813–1894: Graveur Original et Peintre Animalier, 169.

-

“Il rêve et achève des tableaux agrandis, plus vastes et plus étonnants que jamais” (He dreams and completes enlarged paintings, larger and more astonishing than ever). Jules Claretie, “Introduction,” in Catalogue des Tableaux . . . Composant l’Atelier de Charles Jacque (Paris: Galerie Georges Petit, November 12–15, 1894), 7.

-

Jacque also produced several interior views of sheepfolds—for example, Sheepfold (1857; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)—as well as the related etching, arguably his masterpiece in the print form.

-

“Ch. Jacque du temps de ma jeunesse, je l’exécrais, on le préférait à Millet.” Camille Pissarro to Lucien Pissarro, June 28, 1891, in Janine Bailly-Herzberg, ed. La correspondance de Camille Pissarro (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France Editions du Valhermeil, 1988), 3:100.

-

Beraldi lists 487 caricatures, etchings, and lithographs. See Henri Beraldi, Les Graveurs du XIXe siècle (Paris: Librairie L. Conquet: 1889), 8:171–92.

-

The Baltimore Museum of Art has a remarkable collection of Jacque’s prolific print output, largely collected by the American art agent George Lucas, a great admirer of Jacque.

-

In Beraldi, Les Graveurs, 8:191, no. 470.

-

“Il a vendu en 1848 dix tableaux pour trois cents francs,—soit trente francs le tableau,—et certaines toiles de lui en valent aujourd’hui trente mille” (In 1848, he sold ten paintings for three hundred francs—that is, thirty francs a painting—and some of his paintings are worth thirty thousand today). Claretie, Catalogue des Tableaux . . . Composant l’Atelier de Charles Jacque, 6.

-

Exposition de Tableaux, Dessins et Gravures par Ch. Jacque, Galerie Durand-Ruel, Paris, November 15–December 15, 1891. At the same time, they were showing solo exhibitions of the Impressionists, including Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Camille Pissarro.

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Mary Schafer, “Charles-Émile Jacque, Sheep at the Watering Hole, ca. 1888,” technical entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.520.2088.

MLA:

Schafer, Mary. “Charles-Émile Jacque, Sheep at the Watering Hole, ca. 1888,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.520.2088.

Sheep at the Watering Hole was executed on a medium-weight, plain-weaveplain weave: A basic textile weave in which one weft thread alternates over and under the warp threads. Often this structure consists of one thread in each direction, but threads can be doubled (basket weave) or tripled to create more complex plain weave. Plain weave is sometimes called tabby weave. canvas that is attached to a six-member stretcherstretcher: A wooden structure to which the painting’s canvas is attached. Unlike strainers, stretchers can be expanded slightly at the joints to improve canvas tension and avoid sagging due to humidity changes or aging. with mortise-and-tenon joinery. The single set of tacks on the preserved tacking margintacking margins: The outer edges of canvas that wrap around and are attached to the stretcher or strainer with tacks or staples. See also tacking edge. indicate that the dimensions of the painting are original. The no. 40 paysage standard-formatstandard-format supports: Commercially prepared supports available through art suppliers, which gained popularity in the nineteenth century during the industrialization of art materials. Available in three formats figure (portrait), paysage (landscape), and marine (marine), these were numbered 1 through 120 to indicate their size. For each numbered size, marine and paysage had two options available: a larger format (haute) and smaller (basse) format. canvas bears the stampcanvas stamp: An ink stamp, often present on the reverse of the canvas, signifying the company that sold or prepared the canvas. As these companies sometimes performed framing and restorations, these stamps could also reflect these services. See also supplier mark. of Felix Voisinot (1841–84), who was working at 46 rue Notre Dame de Lorette from about 1876 to 1881 (Fig. 3).1Although faint in areas, the stamp on the canvas reverse reads “46, RUE NOTRE DA[ME de] LORET[TE] / ANCIENNE MAISON OTTOZ FRERES A OTTOZ / Félix VOISINOT Suc.r / Toiles, Couleurs Fines, Panneaux. / PARIS”,2Pascal Labreuche, “La maison Ottoz, Voisinot successeur (suite) et La maison Tedesco,” Bulletin de la Société des Amis de Jongkind, no. 48A (December 31, 2017): 27. While the purchase of the support likely occurred during this period, the landscape is presumed to have been painted closer to 1888, the date by which Jacque created a related etching, Sheep at the Watering Place (Abreuvoir aux moutons) (see Fig. 2).3See the accompanying catalogue essay by Simon Kelly.

Fig. 3. Detail of the Voisinot stamp, oriented horizontally and located in the lower right quadrant of the canvas reverse, Sheep at the Watering Hole (ca. 1888)

Fig. 3. Detail of the Voisinot stamp, oriented horizontally and located in the lower right quadrant of the canvas reverse, Sheep at the Watering Hole (ca. 1888)

Fig. 4. Photomicrograph of Sheep at the Watering Hole (ca. 1888), showing sketch lines beneath the paint of a sheep

Fig. 4. Photomicrograph of Sheep at the Watering Hole (ca. 1888), showing sketch lines beneath the paint of a sheep

Fig. 7. Detail of sheep with raking illumination, Sheep at the Watering Hole (ca. 1888)

Fig. 7. Detail of sheep with raking illumination, Sheep at the Watering Hole (ca. 1888)

Fig. 8. Detail of Sheep at the Watering Hole (ca. 1888), showing the wet-over-dry brushwork of the water

Fig. 8. Detail of Sheep at the Watering Hole (ca. 1888), showing the wet-over-dry brushwork of the water

Fig. 9. Detail of the lower portion of the central tree, Sheep at the Watering Hole (ca. 1888), showing dabs of blue-gray overlapping the brown paint of the branches, with finely painted leaves rendered on top of passages of sky

Fig. 9. Detail of the lower portion of the central tree, Sheep at the Watering Hole (ca. 1888), showing dabs of blue-gray overlapping the brown paint of the branches, with finely painted leaves rendered on top of passages of sky

Fig. 10. Photomicrograph in raking illumination, showing a small tack hole at the bottom right corner of Sheep at the Watering Hole (ca. 1888)

Fig. 10. Photomicrograph in raking illumination, showing a small tack hole at the bottom right corner of Sheep at the Watering Hole (ca. 1888)

Fig. 11. Photomicrograph of Sheep at the Watering Hole (ca. 1888), showing a pinhole and incised line, both of which are covered by brown paint

Fig. 11. Photomicrograph of Sheep at the Watering Hole (ca. 1888), showing a pinhole and incised line, both of which are covered by brown paint

Fig. 12. Reflected infrared digital photograph of Sheep at the Watering Hole (ca. 1888)

Fig. 12. Reflected infrared digital photograph of Sheep at the Watering Hole (ca. 1888)

The unlined canvas has become weak and brittle over time, and in addition to mild canvas distortions along the top edge, small splits in the canvas have formed at the turnover edgeturnover edge: The point at which the canvas begins to wrap around the stretcher, at the junction between the picture plane and tacking margin. See also foldover edge.. A mildly cupped craquelurecraquelure: The network or pattern of cracks that develop on a paint surface as it ages. has developed across the paint surface, and diagonal cracks at the corners result from the tension of the stretched canvas. In 1989, the painting was cleaned to remove a discolored natural resin varnish, and a synthetic varnish was brush-applied.6Forrest Bailey, August 29, 1989, treatment report, NAMA conservation file, 31-88. While this surface coating continues to saturate the paint colors, it has become discolored over time. A small amount of retouchingretouching: Paint application by a conservator or restorer to cover losses and unify the original composition. Retouching is an aspect of conservation treatment that is aesthetic in nature and that differs from more limited procedures undertaken solely to stabilize original material. Sometimes referred to as inpainting or retouch. is present on the outermost edges.

Notes

-

Although faint in areas, the stamp on the canvas reverse reads “46, RUE NOTRE DA[ME de] LORET[TE] / ANCIENNE MAISON OTTOZ FRERES A OTTOZ / Félix VOISINOT Suc.r / Toiles, Couleurs Fines, Panneaux. / PARIS”

-

Pascal Labreuche, “La maison Ottoz, Voisinot successeur (suite) et La maison Tedesco,” Bulletin de la Société des Amis de Jongkind, no. 48A (December 31, 2017): 27.

-

See the accompanying catalogue essay by Simon Kelly.

-

Beginning in the 1870s, Jacque employed studio assistants to reproduce his sketches and possibly complete the initial laying-in of the painting according to the artist’s specifications, all in an effort to increase his production. See Stéphanie Constantin, “The Painters of the Barbizon Circle and Landscape Paintings: Techniques and Working Methods” (PhD diss., Courtauld Institute of Art, 2001), 72, 290–92.

-

Constantin, “The Painters of the Barbizon Circle and Landscape Paintings,” 292–93.

-

Forrest Bailey, August 29, 1989, treatment report, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, 31-88.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Charles-Émile Jacque, Sheep at the Watering Hole, ca. 1888,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.520.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Charles-Émile Jacque, Sheep at the Watering Hole, ca. 1888,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.520.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Charles-Émile Jacque, Sheep at the Watering Hole, ca. 1888,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.520.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Charles-Émile Jacque, Sheep at the Watering Hole, ca. 1888,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.520.4033.

With R. et C. Gérard Frères, Paris, by June 15, 1923 [1];

Purchased from Gérard Frères by M. Knoedler and Co., New York, stock no. 15643, as Moutons à l’Abreuvoir, 1923–January 6, 1925 [2];

Purchased from Knoedler and Co., by John Levy Galleries, New York, 1925–April 28, 1931 [3];

Purchased from John Levy Galleries and Findlay Galleries, Kansas City, MO, through Harold Woodbury Parsons, by The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1931 [4].

Notes

[1] According to the Wildenstein Plattner Institute, “From October 1911 to 1927, Félix Isidore’s two sons, Raphaël Louis Félix Gérard (born 1886, Colombes, Île-de-France–died 1963, Paris) and Christian Alfred Valère (born 1887, Colombes, Île-de-France–died 1945, Paris) expanded the family’s activities by opening a gallery at 2 rue La Boétie under the name Gérard Frères.”

[2] See M. Knoedler and Co. records, approximately 1848–1971, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, Painting Stock Book 7, p. 53, no. 15643, as Moutons à L’abreuvoir. See also Series IV. Inventory cards, 1859–1971, Box 118, Knoedler–Mazoh, Item 233, as Sheep and Shepherd at the Pool.

[3] See footnote 2.

[4] See letters from Harold Woodbury Parsons, art adviser to the Nelson-Atkins, to J. C. Nichols, Nelson-Atkins trustee, March 13 and 25, 1931, Nelson-Atkins curatorial files. Parsons sent the painting from John Levy Galleries to an exhibition at Findlay Galleries in the spring of 1931. Parsons encouraged the museum trustees to purchase the picture, and Findlay earned some profit on the arrangement.

According to a certificate of guarantee from John Levy Galleries and Findlay Galleries to Nelson-Atkins, Nelson-Atkins curatorial files, John Levy Galleries purchased the painting from a client of Boussod, Valadon and Co. However, the painting has not been found in Galerie Boussod, Valadon stock books at the Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Charles-Émile Jacque, Sheep at the Watering Hole, ca. 1888,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.520.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Charles-Émile Jacque, Sheep at the Watering Hole, ca. 1888,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.520.4033.

Charles-Émile Jacque, Sheep at a Watering Place, about 1840–50, oil on canvas, 32 x 25 3/4 in. (81.5 x 65.4 cm), National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh.

Preparatory Works

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Charles-Émile Jacque, Sheep at the Watering Hole, ca. 1888,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.520.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Charles-Émile Jacque, Sheep at the Watering Hole, ca. 1888,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.520.4033.

Charles-Émile Jacque, Abreuvoir aux moutons (Sheep at the Watering Hole), pencil on tracing paper, 14 3/8 x 19 3/4 in. (36.5 x 50 cm), Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris.

Reproductions

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Charles-Émile Jacque, Sheep at the Watering Hole, ca. 1888,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.520.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Charles-Émile Jacque, Sheep at the Watering Hole, ca. 1888,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.520.4033.

Charles-Émile Jacque, Sheep at the Watering Place, 1888, etching on imitation vellum paper, plate: 16 3/16 x 21 in. (41.1 x 53.4 cm); sheet: 16 15/16 x 21 13/16 in. (43 x 55.4 cm), National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Charles-Émile Jacque, Sheep at the Watering Hole, ca. 1888,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.520.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Charles-Émile Jacque, Sheep at the Watering Hole, ca. 1888,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.520.4033.

Exhibition, Findlay Galleries, Kansas City, MO, spring 1931.

Winfield (KS) Public Schools, 1941.

Exhibition in conjunction with the Consumers Cooperative Association’s 30th Annual Meeting, Municipal Auditorium, Kansas City, MO, December 2–5, 1958.

Corot to Monet: The Rise of Landscape Painting in France, The Currier Gallery of Art, Manchester, NH, January 27–April 29, 1991; IBM Gallery of Science and Art, July 30–September 28, 1991; Dallas Museum of Art, November 3, 1991–January 5, 1992; High Museum of Art, January 28–March 29, 1992, no. 73.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Charles-Émile Jacque, Sheep at the Watering Hole, ca. 1888,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.520.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Charles-Émile Jacque, Sheep at the Watering Hole, ca. 1888,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.520.4033.

“Another Recent Purchase for the Nelson Gallery of Art,” Kansas City Star 51, no. 263 (June 7, 1931): 4, (repro.), as Sheep.

“What to See In Kansas City: A Guide to Principal Points of Interest Presented in the Style of a Baedeker,” Kansas City Star 52, no. 101 (December 27, 1931): 3C, as Sheep.

“Nelson Gallery of Art Special Number,” Art Digest 8, no. 5 (December 1, 1933): 21, as Sheep.

“The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art, Kansas City Special Number,” Art News 32, no. 10 (December 9, 1933): 28, as Sheep.

The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Handbook of the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1933), 137, as Sheep.

The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, The William Rockhill Nelson Collection, 2nd ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1941), 168, as Sheep.

Ross E. Taggart, ed., Handbook of the Collections in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 4th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1959), 260, a Sheep.

Ross E. Taggart and George L. McKenna, eds., Handbook of the Collections in The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Kansas City, Missouri, vol. 1, Art of the Occident, 5th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1973), 258, as Sheep.

Kermit S. Champa, The Rise of Landscape Painting in France: Corot to Manet, exh. cat. (Manchester, NH: The Currier Gallery of Art, 1991), 174, 229, (repro.), as Sheep (At the Watering Hole).

Catherine Futter et al., Bloch Galleries: Highlights from the Collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2016), 33, 175, (repro.), as Sheep (At the Watering Hole).