Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Henri Fantin-Latour, Annual Chrysanthemums, 1889,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.516.5407.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Henri Fantin-Latour, Annual Chrysanthemums, 1889,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.516.5407.

When Henri Fantin-Latour painted his first floral still life in 1854, France’s traditional hierarchy of artistic genres was in flux.1Fantin-Latour’s first recorded still life is Flowers, 1854, oil on canvas, 18 3/16 x 16 5/16 in. (46.2 x 41.4 cm), Museum voor Schone Kunsten Gent, Belgium, Inv. 1914-AY, https://www.mskgent.be/en/collection/1914-ay. For centuries, history painting had reigned supreme, followed, in descending order, by portraiture, genre scenes, landscapes, and, at the very bottom, still lifes. The latter two categories were held in low esteem by the Académie des Beaux-Arts because they lacked human figures. During the nineteenth century, however, French artists upended these rankings by favoring the very genres that the establishment had long belittled.2For this history, see Mitchell Merling, “The Path to the Modern Floral Still Life: Academy to Avant-Garde,” in Heather MacDonald and Mitchell Merling, Working Among Flowers: Floral Still-Life Painting in Nineteenth-Century France, exh. cat. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), 15–27. Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863) and Gustave Courbet (1819–77) experimented with floral compositions in the 1840s and 1860s, respectively, and many of the Impressionists did likewise between the early 1860s and mid-1880s. Claude Monet (1840–1926), for one, produced at least twenty-two flower pictures between 1878 and 1885, several of which were ambitious in scale and sold well with collectors.3Sylvie Patry, “Impressionist Flower Paintings and the Market,” trans. Chris Miller, in MacDonald and Merling, Working Among Flowers, 35. However, the combined output of all these artists paled in comparison to that of Fantin-Latour, who painted somewhere between five hundred and 850 floral still lifes during his career.4Elisabeth Hardouin-Fugier estimates that Fantin-Latour made between 750 and 850 flower paintings, while Laurent Salomé suggests a range of five hundred to six hundred. See Elisabeth Hardouin-Fugier, “Fantin-Latour, peintre de fleurs,” Gazette des beaux-arts 113, no. 1442 (March 1989): 138; and Laurent Salomé, “La vie avec les fleurs,” in Laure Dalon, Fantin-Latour: À fleur de peau, exh. cat. (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 2016), 41. A more accurate tally may emerge when Sylvie Brame and François Lorenceau publish their revised catalogue raisonné of Fantin-Latour’s oeuvre. Rather than dabbling in flower pictures like some of his peers, Fantin-Latour made them a cornerstone of his production, and he owed much of his success to their commercial appeal.

The collectors most receptive to Fantin-Latour’s floral works were members of the English upper middle class. During the 1860s, American expatriate painter James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903) and Surrey-based dealers Edwin (1823–79) and Ruth (1833–1907) Edwards stoked demand for Fantin-Latour’s flower pictures in England. They corresponded regularly with Fantin-Latour in Paris, sharing tips about interested buyers and requesting still lifes with particular dimensions. Whistler, for example, wrote to Fantin-Latour on February 3, 1864, saying, “You must do two flower pictures the same size, as those you have just done for Mr. Ionides—You will get 150 frs. for each.”5Whistler to Fantin-Latour, January 4–February 3, 1864, Pennell-Whistler Collection, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, PWC 1/33/15. Transcribed and translated in Margaret F. MacDonald, Patricia de Montfort, and Nigel Thorp, eds., The Correspondence of James McNeill Whistler, 1855–1903, online edition, University of Glasgow, 08036, https://www.whistler.arts.gla.ac.uk/correspondence/date/more/?cid=8036&year=1864&month=01&rs=1. “Il faut que tu fasse encore deux bouquets de la meme [sic] grandeur, que ceux que tu viens de faire pour M. Ionides—On te les paie 150. fs. piece [sic].” Emphasis in the original. Translations by Brigid M. Boyle unless otherwise noted. Thanks to these efforts on his behalf, Fantin-Latour built up a steady clientele across the Channel and earned much-needed income from the sale of his floral compositions. By 1871, he had formalized his business relationship with the Edwardses and designated them as his official agents in England.6Douglas Druick and Michel Hoog, eds., Fantin-Latour, exh. cat. (Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada for the Corporation of the National Museums of Canada, 1983), 216. This mutually beneficial partnership persisted for more than fifty years, with Ruth handling all sales of Fantin-Latour’s work in England after Edwin’s death in 1879.

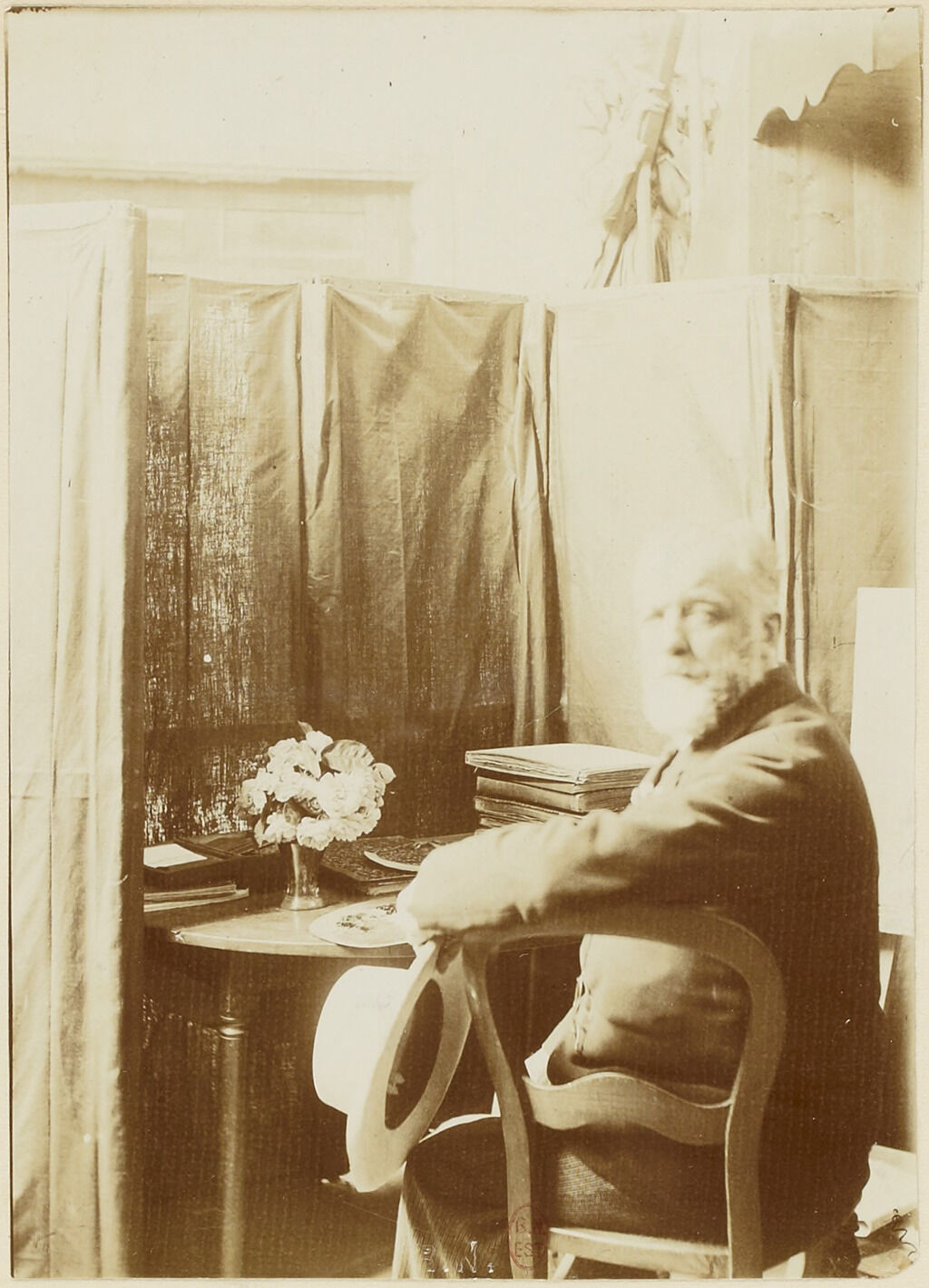

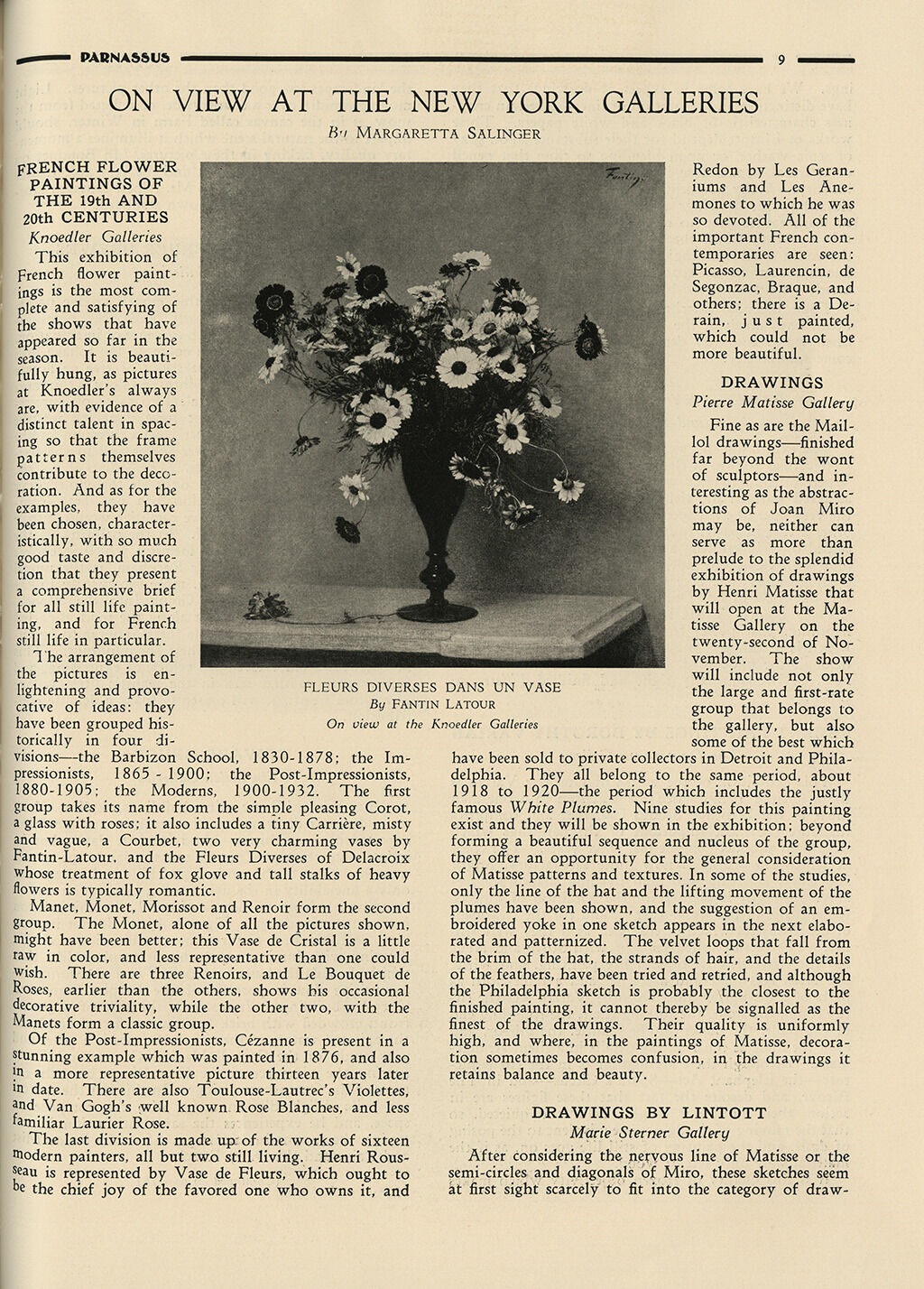

Following the Royal Academy exhibition, Annual Chrysanthemums passed through several private collectors and dealers, beginning with Ruth Edwards, before landing with gallerist Étienne Bignou (1891–1950) by the early 1930s. Bignou lent the picture to a thematic exhibition organized by Knoedler Galleries in New York called “Flowers” by French Painters in November 1932. The American public responded just as warmly to Annual Chrysanthemums as their English counterparts had forty years earlier. Critic and Metropolitan Museum of Art researcher Margaretta Salinger complimented Knoedler on choosing the still lifes “with so much good taste and discretion” and singled out the “two very charming vases by Fantin-Latour” for special notice.23Margaretta Salinger, “On View at the New York Galleries,” Parnassus 4, no. 6 (November 1932): 9. She selected Annual Chrysanthemums to illustrate her article (Fig. 5), as did Ralph Flint in his own effusive review for Art News. Flint waxed poetic about “the brilliant galaxy of French pictures . . . illustrating the Gallic genius in flower painting” and declared Fantin-Latour’s floral contributions “precise and stately and delicately rendered.”24Ralph Flint, “Knoedler Holds Important Exhibit of French Flower Paintings Under the Auspices of Étienne Bignou,” Art News 31, no. 7 (November 12, 1932): 10. The timing of this exhibition, and the critical support for Fantin-Latour that it engendered, brought Annual Chrysanthemums to the attention of the Nelson-Atkins trustees, who acquired it soon after. When critic Minna K. Powell announced this purchase in the April 1, 1933, issue of the Kansas City Star, she emphasized that the museum board had secured “one of the loveliest canvases in the recent ‘Flower Show’ at the Knoedler Galleries” and highlighted its “graceful arrangement, sense of tonality, and the dewy freshness of its flowers.” Her article whetted readers’ appetite to see the Fantin-Latour picture themselves at the museum’s grand opening eight months later.25M[inna] K. P[owell], “In Gallery and Studio,” Kansas City Star, April 1, 1933, 5. The Nelson-Atkins opened its doors on December 10, 1933.

Notes

-

Fantin-Latour’s first recorded still life is Flowers, 1854, oil on canvas, 18 3/16 x 16 5/16 in. (46.2 x 41.4 cm), Museum voor Schone Kunsten Gent, Belgium, Inv. 1914-AY, https://www.mskgent.be/en/collection/1914-ay.

-

For this history, see Mitchell Merling, “The Path to the Modern Floral Still Life: Academy to Avant-Garde,” in Heather MacDonald and Mitchell Merling, Working Among Flowers: Floral Still-Life Painting in Nineteenth-Century France, exh. cat. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), 15–27.

-

Sylvie Patry, “Impressionist Flower Paintings and the Market,” trans. Chris Miller, in MacDonald and Merling, Working Among Flowers, 35.

-

Elisabeth Hardouin-Fugier estimates that Fantin-Latour made between 750 and 850 flower paintings, while Laurent Salomé suggests a range of five hundred to six hundred. See Elisabeth Hardouin-Fugier, “Fantin-Latour, peintre de fleurs,” Gazette des beaux-arts 113, no. 1442 (March 1989): 138; and Laurent Salomé, “La vie avec les fleurs,” in Laure Dalon, Fantin-Latour: À fleur de peau, exh. cat. (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 2016), 41. A more accurate tally may emerge when Sylvie Brame and François Lorenceau publish their revised catalogue raisonné of Fantin-Latour’s oeuvre.

-

Whistler to Fantin-Latour, January 4–February 3, 1864, Pennell-Whistler Collection, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, PWC 1/33/15. Transcribed and translated in Margaret F. MacDonald, Patricia de Montfort, and Nigel Thorp, eds., The Correspondence of James McNeill Whistler, 1855–1903, online edition, University of Glasgow, 08036, https://www.whistler.arts.gla.ac.uk/correspondence/date/more/?cid=8036&year=1864&month=01&rs=1. “Il faut que tu fasse encore deux bouquets de la meme [sic] grandeur, que ceux que tu viens de faire pour M. Ionides—On te les paie 150. fs. piece [sic].” Emphasis in the original. Translations by Brigid M. Boyle unless otherwise noted.

-

Douglas Druick and Michel Hoog, eds., Fantin-Latour, exh. cat. (Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada for the Corporation of the National Museums of Canada, 1983), 216.

-

For Victoria Fantin-Latour’s life and career, see Elizabeth Kane, “Victoria Dubourg: The Other Fantin-Latour,” Woman’s Art Journal 9, no. 2 (Fall 1988–Winter 1989): 15–21.

-

For census data, see Claude Motte and Marie-Christine Vouloir, “Buré,” Des villages de Cassini aux communes d’aujourd’hui, Laboratoire de démographie historique, Centre national de la recherche scientifique, École des hautes études en sciences sociales, accessed April 3, 2024, http://cassini.ehess.fr/fr/html/fiche.php?select_resultat=6306. Buré had 234 residents in 1881 and 204 residents in 1886. Its population dwindled throughout the 1900s, falling below one hundred in 1975. The town is a modest 565 hectares, or 2.2 square miles.

-

For a painting of this space, see Victoria Fantin-Latour, The Garden at Buré, 19th century, oil on canvas, 12 5/8 x 15 15/16 in. (32 x 40.5 cm), Musée de Grenoble, MG 2511, https://www.navigart.fr/grenoble/artwork/victoria-fantin-latour-nee-victoria-dubourg-le-jardin-de-bure-orne-60000000005285.

-

Jacques-Émile Blanche, Propos de Peintre: De David à Degas (Paris: Émile-Paul frères, 1919), 42. “Le peintre, sous un vieux chapeau de paille, le cou enveloppé d’un foulard d’été, toujours chaussé de pantoufles, dès après son petit déjeuner va cueillir dans les plates-bandes ce que la nuit a fait éclore de plus coloré.”

-

For more on Fantin-Latour’s working method, see Blanche, Propos de Peintre, 42–48.

-

Per the testimony of Fantin-Latour’s Parisian dealer, Gustave Tempelaere. See Druick and Hoog, Fantin-Latour, 270.

-

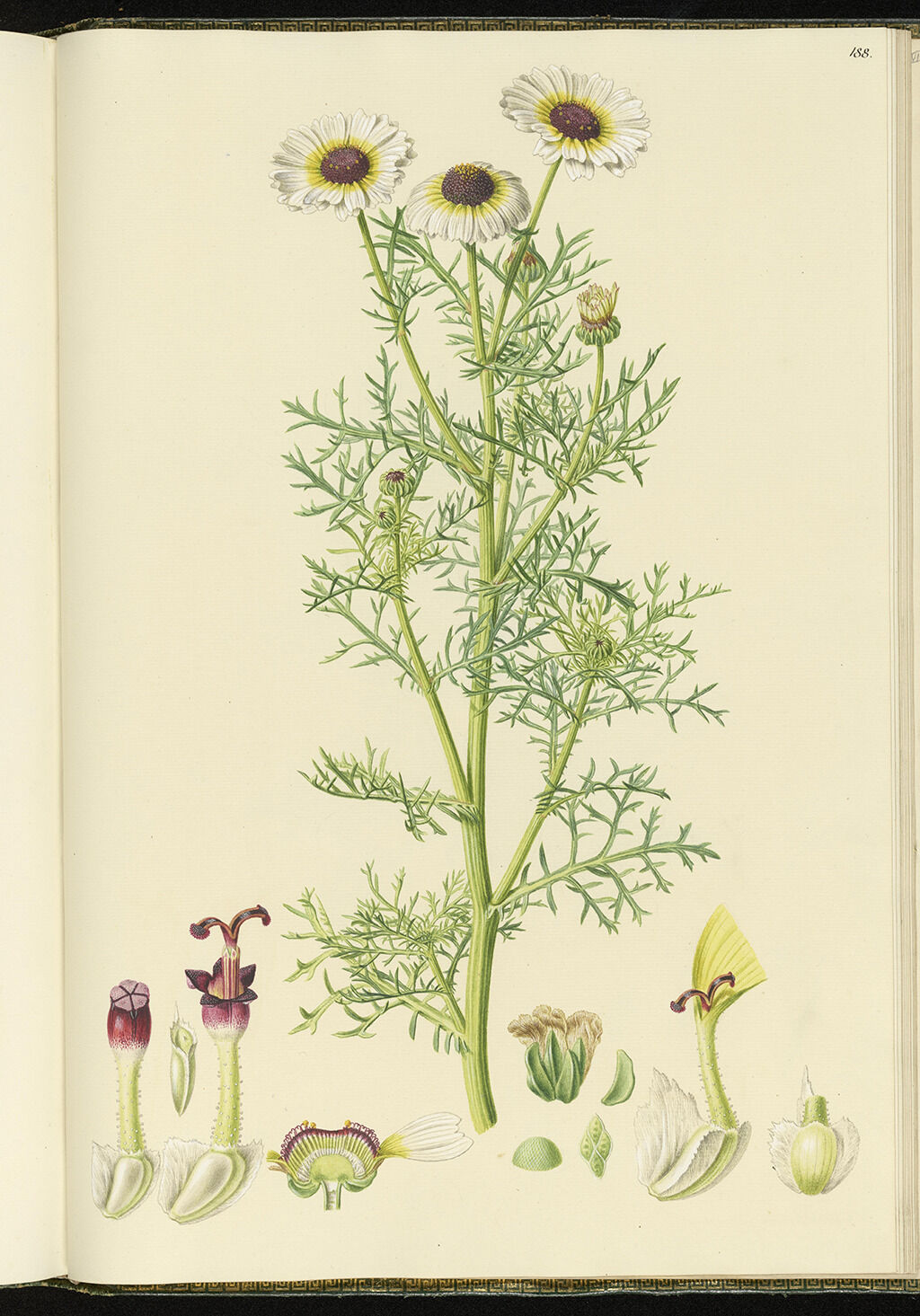

I am indebted to Craig Freeman, senior curator of botany at the KU Biodiversity Institute and Natural History Museum, University of Kansas; and Lena Struwe, director of the Chrysler Herbarium and Mycological Collection and professor at the School of Environmental and Biological Sciences, Rutgers University, for this identification and the description that follows.

-

Friedrich’s engraving was part of a large, multi-artist project begun in 1785 and completed in 1840 under the aegis of Frederick Augustus II (1797–1854), successor to Frederick Augustus I. For a brief overview, see R. G. C. Desmond, “Some Early Cultivated Plants,” Kew Bulletin 22, no. 3 (1968): 392.

-

See, for instance, Still Life with Chrysanthemums, 1862, oil on canvas, 18 1/8 x 21 7/8 in. (46 x 55.6 cm), Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1978-1-16, https://philamuseum.org/collection/object/72087; Chrysanthemums, 1874, oil on canvas, 21 3/4 x 25 1/2 in. (55.2 x 64.8 cm), The Burrell Collection, Glasgow, no. 35.260, https://collections.glasgowmuseums.com/mwebcgi/mweb?request=record;id=37412;type=101; Yellow Chrysanthemums, 1879, oil on canvas, 24 x 19 1/16 in. (61 x 48.4 cm), Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, Glasgow, no. 1795, https://collections.glasgowmuseums.com/mwebcgi/mweb?request=record;id=166784;type=101; and Large Bouquet of Chrysanthemums, 1882, oil on canvas, 24 1/2 x 22 in. (62.2 x 55.9 cm), High Museum of Art, Atlanta, 2019.147, https://high.org/collection/large-bouquet-of-chrysanthemums-grand-bouquet-de-chrysanthemes/. My thanks to Pegeen Blank for her assistance with this research.

-

Druick and Hoog, Fantin-Latour, 257.

-

Laurent Salomé was the first to note this exercise of artistic license. See Salomé, “La vie avec les fleurs,” 44.

-

“Fine Arts: The Royal Academy (First Notice),” Athenaeum, no. 3262 (May 3, 1890): 575.

-

“Fine Arts: The Royal Academy (Third and Concluding Notice),” Athenaeum, no. 3265 (May 24, 1890): 680. The Nelson-Atkins painting was exhibited as Chrysanthèmes d’été (Summer Chrysanthemums) in reference to the plant’s primary growing season.

-

Harry Quilter, “The Art of England: The Royal Academy,” Universal Review 7, no. 25 (May 1890): 45. For Lavery’s painting, see Impressionist and 19th Century Art Pt. 1, Christie’s, London, December 8, 1998, lot 17.

-

“Royal Academy,” Observer (London), May 11, 1890, 5.

-

Paul Leroi, “Chronique des Expositions: Les trois principales Expositions de Londres,” Courrier de l’art 10, no. 27 (July 4, 1890): 214. “Très réussis.”

-

Margaretta Salinger, “On View at the New York Galleries,” Parnassus 4, no. 6 (November 1932): 9.

-

Ralph Flint, “Knoedler Holds Important Exhibit of French Flower Paintings Under the Auspices of Étienne Bignou,” Art News 31, no. 7 (November 12, 1932): 10.

-

M[inna] K. P[owell], “In Gallery and Studio,” Kansas City Star, April 1, 1933, 5. The Nelson-Atkins opened its doors on December 10, 1933.

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Sophia Boosalis, “Henri Fantin-Latour, Annual Chrysanthemums, 1889,” technical entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.516.2088.

MLA:

Boosalis, Sophia. “Henri Fantin-Latour, Annual Chrysanthemums, 1889,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.516.2088.

The painting Annual Chrysanthemums by Henri Fantin-Latour (1836–1904) is one of over five hundred floral still-life paintings made by the artist between 1864 and 1898.1For the estimated number of floral still-life paintings by Fantin-Latour, see the accompanying curatorial essay by Brigid M. Boyle. Information about the original canvas is limited, as the tacking marginstacking margins: The outer edges of canvas that wrap around and are attached to the stretcher or strainer with tacks or staples. See also tacking edge. have been removed and the outer edges are now covered by retouchingretouching: Paint application by a conservator or restorer to cover losses and unify the original composition. Retouching is an aspect of conservation treatment that is aesthetic in nature and that differs from more limited procedures undertaken solely to stabilize original material. Sometimes referred to as inpainting or retouch.. The x-radiographX-ray radiography (also referred to as x-radiography or radiography): Radiography is an examination tool analogous to the use of X-rays in medicine whereby denser components of a painted composition can be recorded as an inverted shadow image cast on film or a digital X-ray imaging plate from a source such as an X-ray tube. The method has been used for more than a century and is most effective with dense pigments incorporating metallic elements such as lead or zinc. It can reveal artist changes, underlying compositions, and information concerning the artwork’s construction and condition. The resulting image is called an x-radiograph or radiograph. It differs from the uses of X-ray spectrometry in being dependent on the density of the paint to absorb X-rays before they reach the film or image plate and being non-specific as to which elements are responsible for the resulting shadow image. does not show any cuspingcusping: A scalloped pattern along the canvas edges that relates to how the canvas was stretched. Primary cusping reveals where tacks secured the canvas to the support while the ground layer was applied. Secondary cusping can form when a pre-primed canvas is re-stretched by the artist prior to painting. along the outer edges, suggesting that the canvas was cut from a larger piece of primedpriming layer: An opaque preparatory layer applied to the support, either commercially or by the artist, to prevent absorption of the paint into the canvas or panel. See also ground layer. material. The painting is linedlining: A procedure used to reinforce a weakened canvas that involves adhering a second fabric support using adhesive, most often a glue-paste mixture, wax, or synthetic adhesive., obscuring the reverse of the original canvas, along with any colormen stampsartist supplier(s): Also called colormen and color merchants. Artist suppliers prepared materials for artists. This tradition dates back to the Medieval period, but the industrialization of the nineteenth century increased their commerce. It was during this time that ready-made paints in tubes, commercially prepared canvases, and standard-format supports were available to artists for sale through these suppliers. It is sometimes possible to identify the supplier from stamps or labels found on the reverse of the artwork. See also canvas stamp, supplier mark, and *color merchant. or inscriptions that may be present.2Colorman stamps of Hardy-Alan (1859–1909) have been noted on the reverse of Fantin-Latour’s paintings dating from 1873 to 1892. Documentary evidence indicates that the artist purchased primed canvases, stretchers, and tubed paints from Hardy-Alan from 1861 to 1904. Barbara A. Ramsay, “A Note on Fantin’s Technique,” Fantin-Latour, exh. cat. (Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada, 1983), 55.

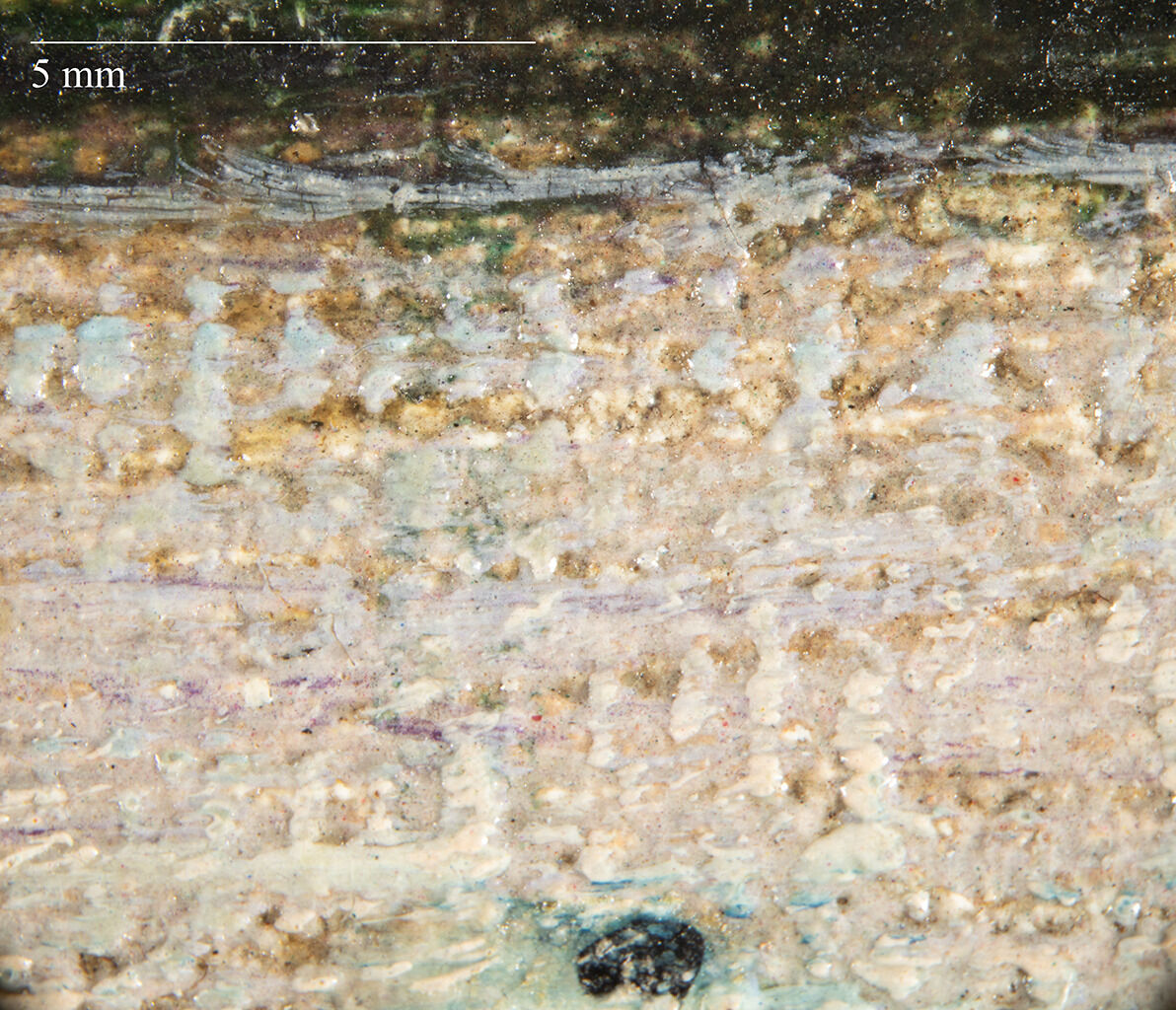

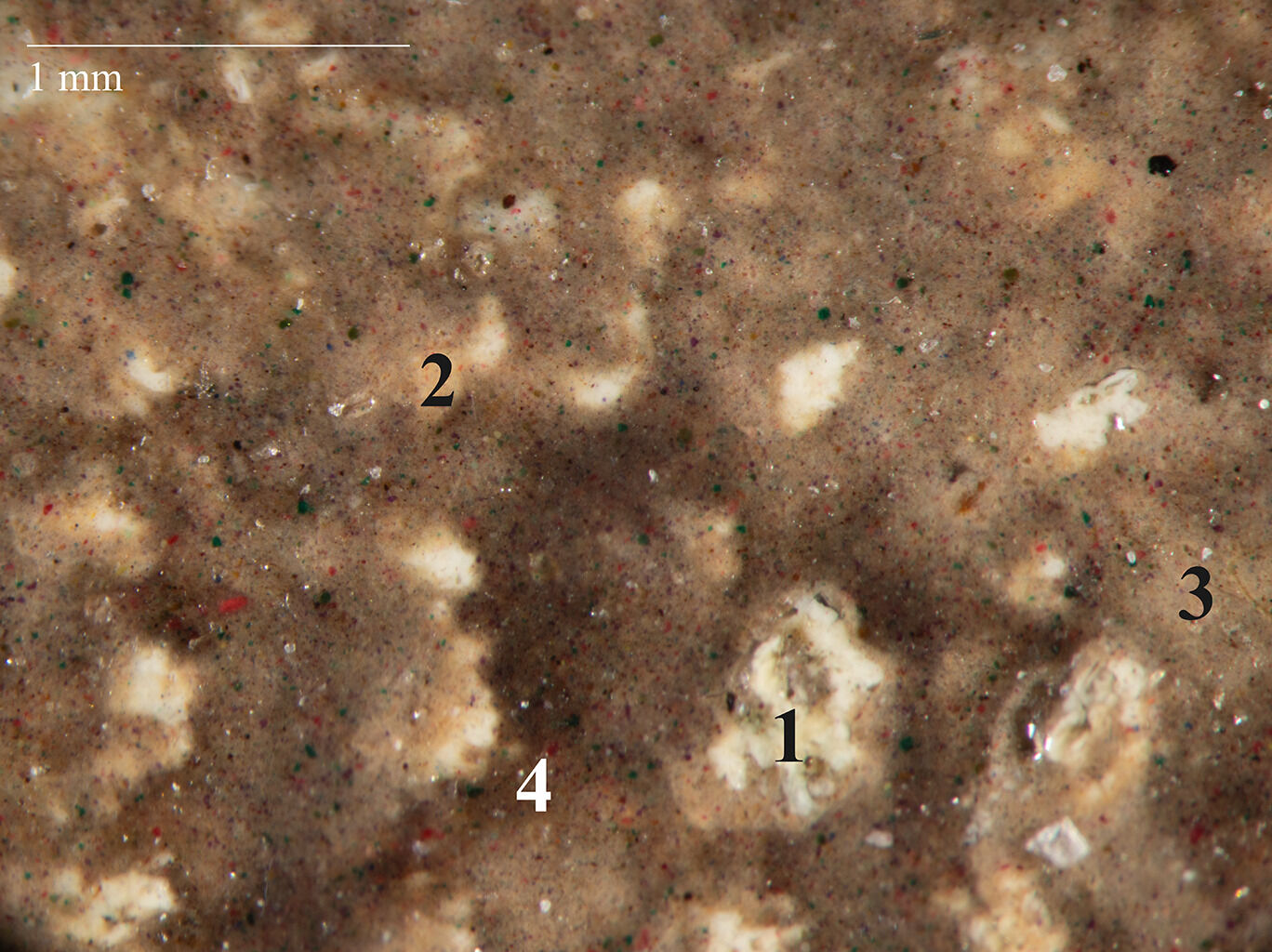

The plain-weaveplain weave: A basic textile weave in which one weft thread alternates over and under the warp threads. Often this structure consists of one thread in each direction, but threads can be doubled (basket weave) or tripled to create more complex plain weave. Plain weave is sometimes called tabby weave. canvas was commercially prepared with a white groundground layer: An opaque preparatory layer applied to the support, either commercially or by the artist, to prevent absorption of the paint into the canvas or panel. See also priming layer., visible on the peaks of the canvas weave texture, between brushstrokes in the background, and along the bottom edge of the canvas. Microscopy examination indicates that the ground layer was first covered with a transparent beige imprimaturaimprimatura: A thin layer of paint applied over the ground layer to establish an overall tonality.. Fantin-Latour typically applied a medium-rich pigment layer to seal the absorbent ground of his commercially primed canvases, which provided a base color for his compositions.3Fantin-Latour preferred to apply imprimatura layers ranging from pale grays to browns and dark reds. Ramsay, “A Note on Fantin’s Technique,” 55.

Fig. 8. Photomicrograph of a few lines at the edge of the vase obscured by retouching in Annual Chrysanthemums (1889)

Fig. 8. Photomicrograph of a few lines at the edge of the vase obscured by retouching in Annual Chrysanthemums (1889)

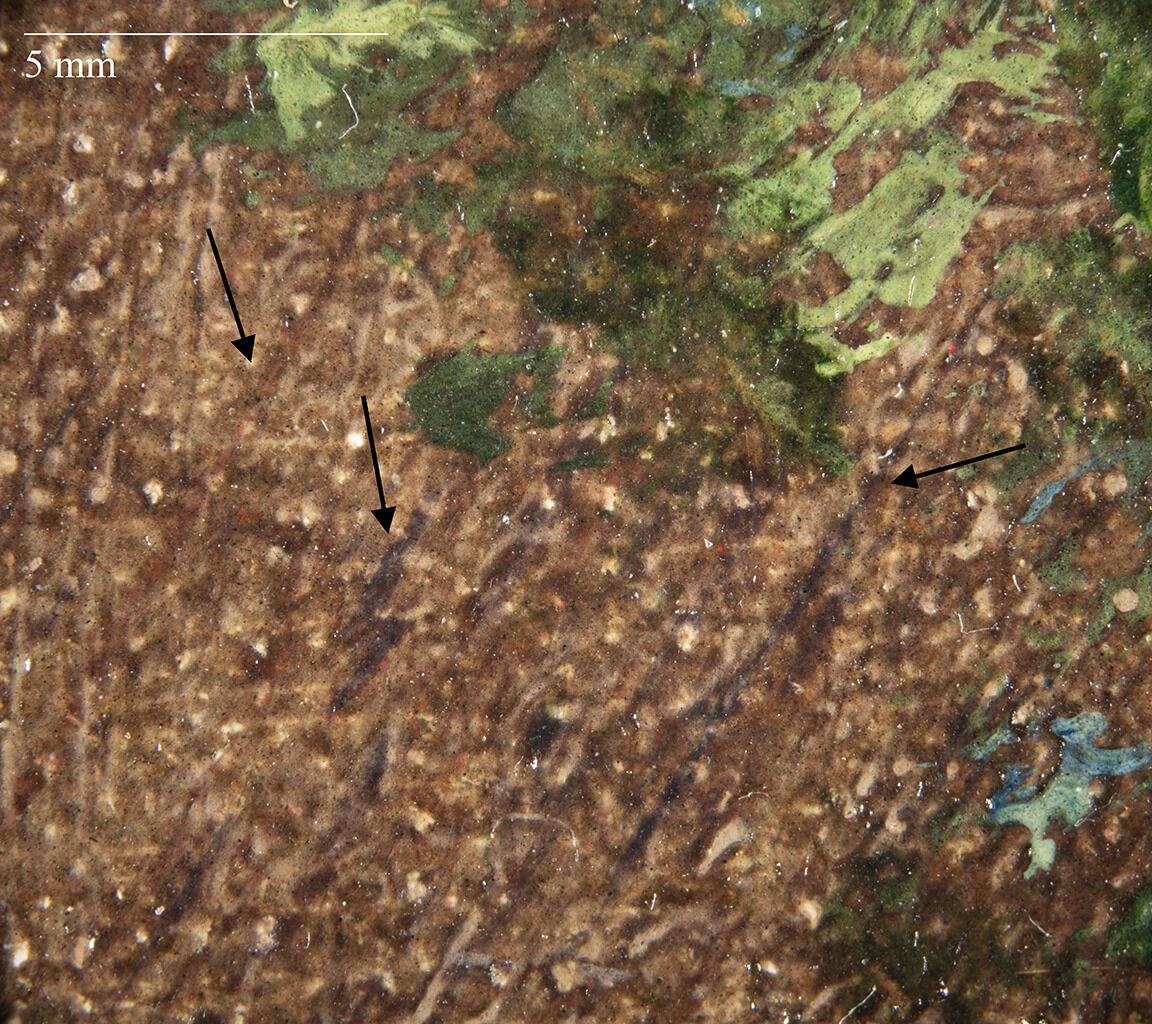

Fig. 9. Photomicrograph of Annual Chrysanthemums (1889), showing the painted lines of a flower petal that was left unpainted

Fig. 9. Photomicrograph of Annual Chrysanthemums (1889), showing the painted lines of a flower petal that was left unpainted

Fig. 10. Photomicrograph of Annual Chrysanthemums (1889), showing painted lines that extend below the foliage

Fig. 10. Photomicrograph of Annual Chrysanthemums (1889), showing painted lines that extend below the foliage

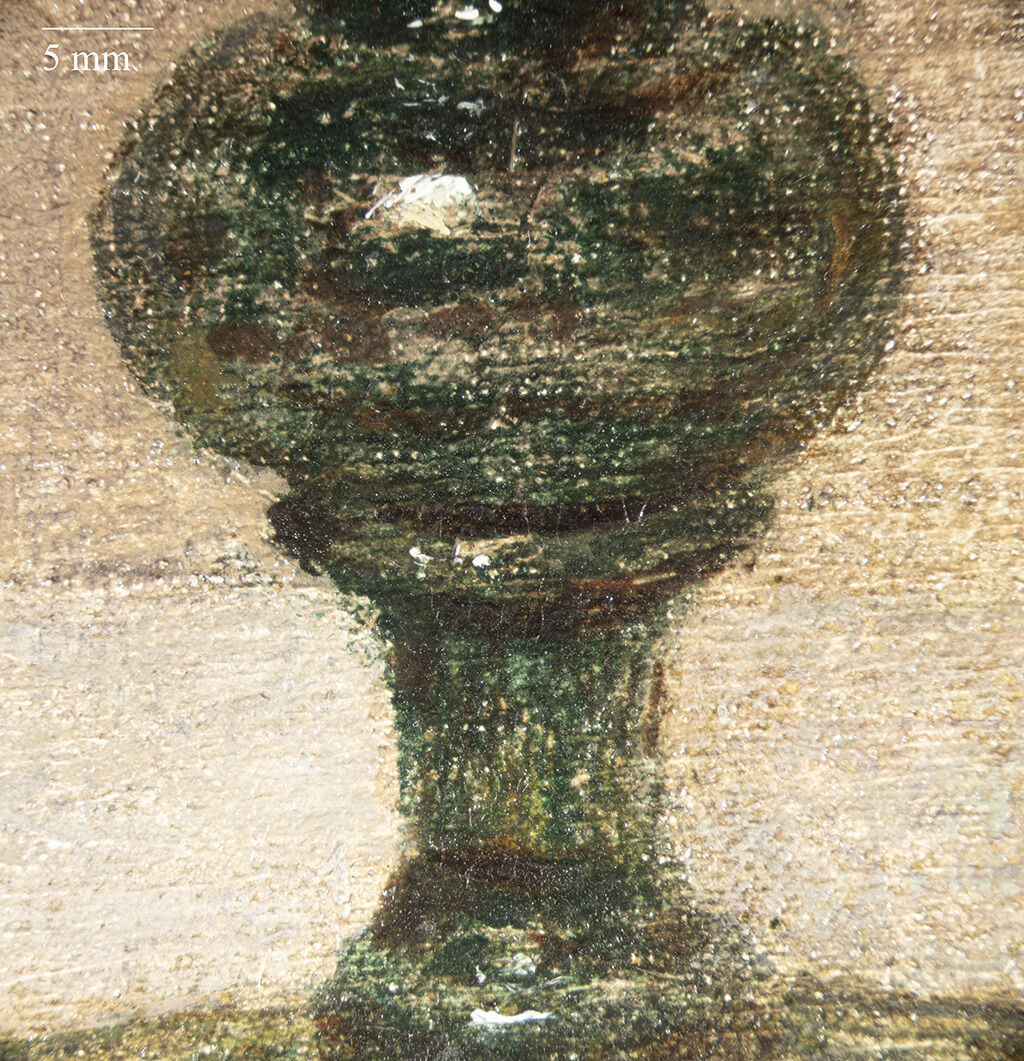

Fig. 11. Photomicrograph of the vase in Annual Chrysanthemums (1889)

Fig. 11. Photomicrograph of the vase in Annual Chrysanthemums (1889)

Fig. 12. Detail of the vase in Annual Chrysanthemums (1889)

Fig. 12. Detail of the vase in Annual Chrysanthemums (1889)

Fig. 13. Photomicrograph of the reserve left for a white chrysanthemum in Annual Chrysanthemums (1889). Black arrows point to the pinkish-gray background that is visible below the white petals.

Fig. 13. Photomicrograph of the reserve left for a white chrysanthemum in Annual Chrysanthemums (1889). Black arrows point to the pinkish-gray background that is visible below the white petals.

Fig. 14. Photomicrograph of the bouquet in Annual Chrysanthemums (1889), showing wet-over-wet paint application

Fig. 14. Photomicrograph of the bouquet in Annual Chrysanthemums (1889), showing wet-over-wet paint application

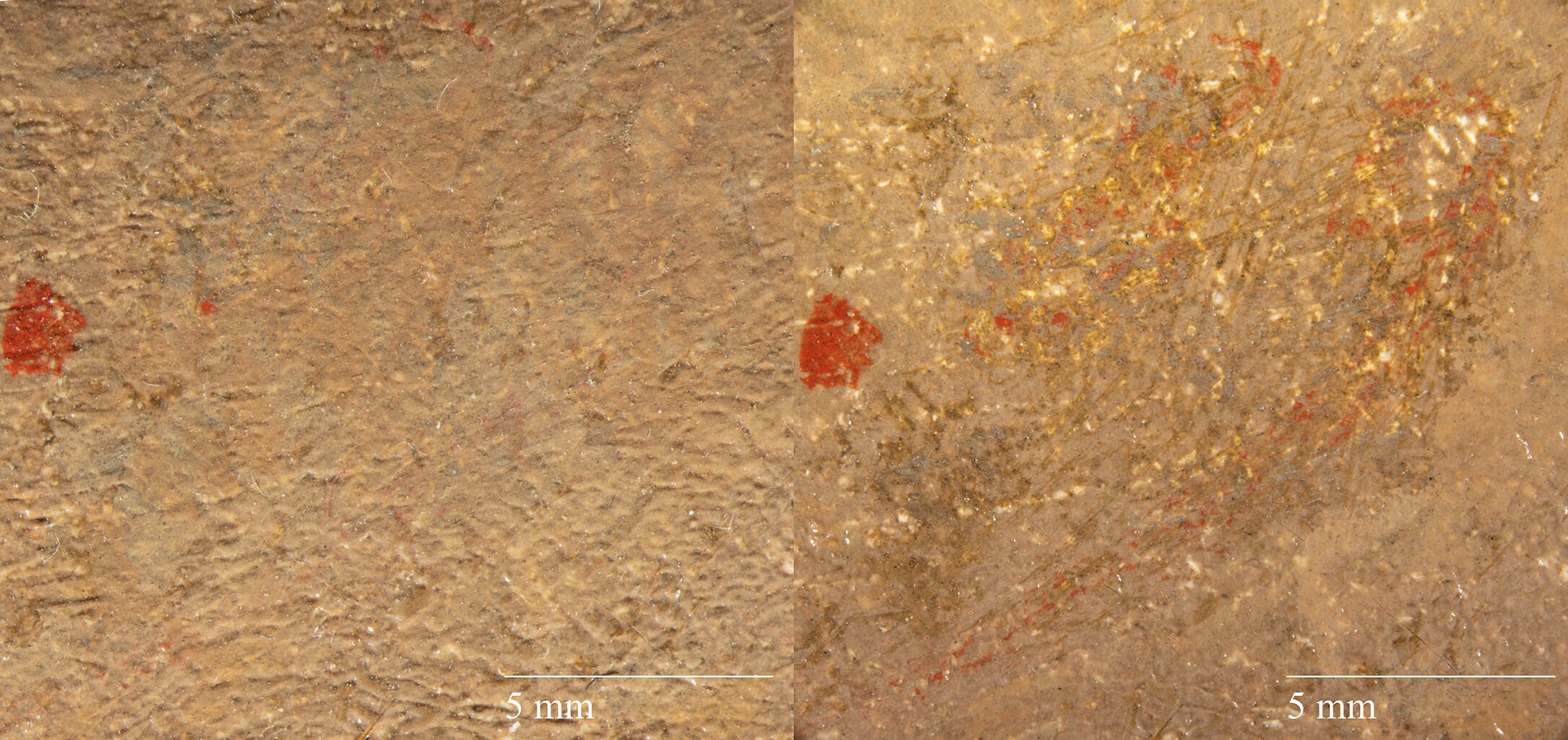

Fig. 15. Details of the bouquet in Annual Chrysanthemums (1889), with the left image in normal light and the right image in UV. The bright orange-red fluorescence in the red flowers is characteristic of madder lake.

Fig. 15. Details of the bouquet in Annual Chrysanthemums (1889), with the left image in normal light and the right image in UV. The bright orange-red fluorescence in the red flowers is characteristic of madder lake.

Fig. 16. Photomicrograph of the flowers and foliage in Annual Chrysanthemums (1889). Black arrows point to the few dabs of purplish-gray paint on top of green paint.

Fig. 16. Photomicrograph of the flowers and foliage in Annual Chrysanthemums (1889). Black arrows point to the few dabs of purplish-gray paint on top of green paint.

Fig. 17. Photomicrograph of the bouquet in Annual Chrysanthemums (1889), showing a few white petals left as an incomplete flower

Fig. 17. Photomicrograph of the bouquet in Annual Chrysanthemums (1889), showing a few white petals left as an incomplete flower

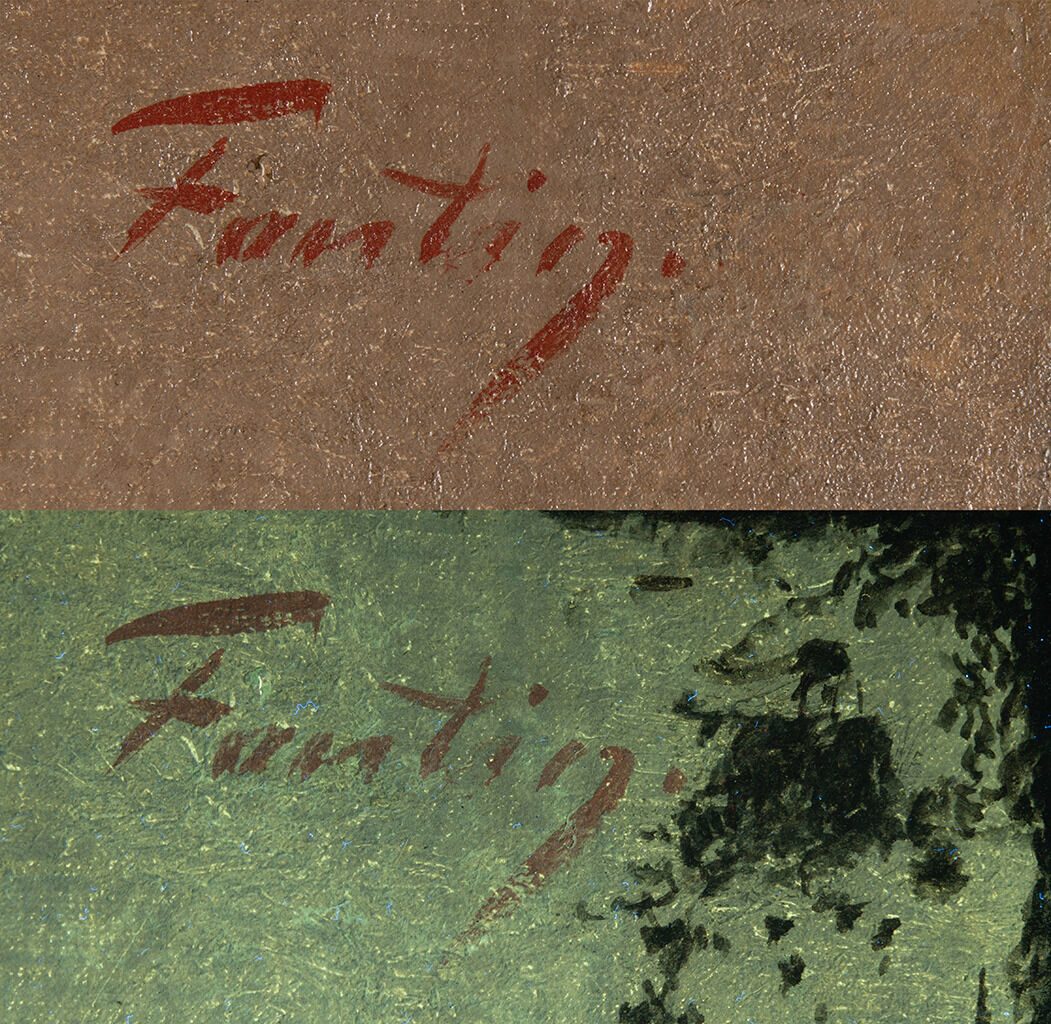

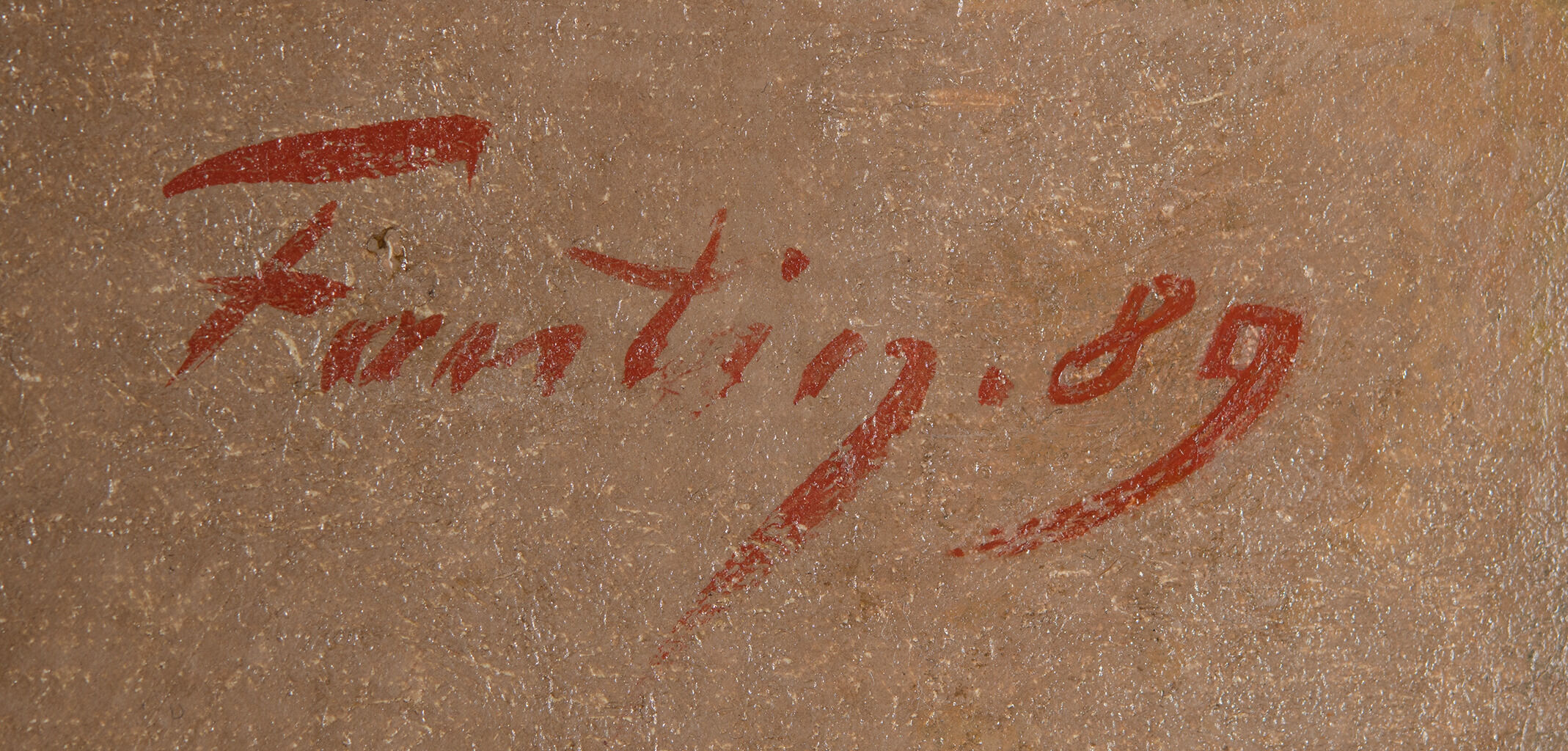

Fig. 19. Details of the artist’s signature near the upper right corner of Annual Chrysanthemums (1889), with the top image in normal light and the bottom image in UV

Fig. 19. Details of the artist’s signature near the upper right corner of Annual Chrysanthemums (1889), with the top image in normal light and the bottom image in UV

Fig. 20. Photomicrograph of the painting’s date in Annual Chrysanthemums (1889), with the left image taken before and the right image taken after cleaning

Fig. 20. Photomicrograph of the painting’s date in Annual Chrysanthemums (1889), with the left image taken before and the right image taken after cleaning

Fig. 21. Detail of the artist’s signature and date after treatment, Annual Chrysanthemums (1889)

Fig. 21. Detail of the artist’s signature and date after treatment, Annual Chrysanthemums (1889)

Notes

-

For the estimated number of floral still-life paintings by Fantin-Latour, see the accompanying curatorial essay by Brigid M. Boyle.

-

Colorman stamps of Hardy-Alan (1859–1909) have been noted on the reverse of Fantin-Latour’s paintings dating from 1873 to 1892. Documentary evidence indicates that the artist purchased primed canvases, stretchers, and tubed paints from Hardy-Alan from 1861 to 1904. Barbara A. Ramsay, “A Note on Fantin’s Technique,” Fantin-Latour, exh. cat. (Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada, 1983), 55.

-

Fantin-Latour preferred to apply imprimatura layers ranging from pale grays to browns and dark reds. Ramsay, “A Note on Fantin’s Technique,” 55.

-

Joyce Hill Stoner refers to this surface aesthetic as “weavism,” where rubbed-down paint reveals the canvas weave as part of the visual effect. Joyce Hill Stoner, “Materials for Immateriality,” in Like Breath on Glass: Whistler, Inness, and the Art of Painting Softly, ed. Marc Simpson, Wanda M. Corn, and C. Hartley, exh. cat. (Williamstown: Clark Art Institute, 2008), 92. Christina Young, “History of Fabric Supports,” in Conservation of Easel Paintings, ed. Joyce Hill Stoner and Rebecca Rushfield (New York: Routledge, 2012), 141.

-

According to Jacques-Emile Blanche (1861–1942), Fantin-Latour “scraped the background with his penknife, as if to suggest the trellis, the shaky and misty atmosphere.” English translation found in Eduardo Lourenço, Olivier Meslay, and Vincent Pomarède, Henri Fantin-Latour, 1836–1904, exh. cat. (Lisbon: Museu Calouste Gulbenkian, 2009), 258. For the French text, see Jacques-Emile Blanche, “Fantin Latour,” La Revue de Paris, May 15, 1906, 310: “Il gratte le fond de la pointe du canif, comme pour suggérer le treillis, le tremblé, la buée de l’atmosphère.”

-

Observations made during the treatment of Gladioli and Roses; see Claire Shepherd, “Conservation of ‘Gladioli and Roses’ by Henri Fantin-Latour,” City of London, February 15, 2024: https://www.thecityofldn.com/article/conservation-of-gladioli-and-roses-by-henri-fantin-latour/.

-

See the accompanying curatorial essay by Brigid M. Boyle.

-

Madder lake is an organic pigment made from the madder plant and used in dyes. Madder has been identified in Fantin-Latour’s paintings such as A Basket of Roses (1890) and The Rosy Wealth of June (1886). Jo Kirby, Marika Spring, Katherine Higgitt, “The Technology of Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century Red Lake Pigments,” National Gallery Technical Bulletin 28 (2007): 91.

-

James Roth, “Department of Conservation,” in Annual Report for 1959, Nelson-Atkins Archives, Kansas City, MO, RG-98, series II, box RG98.05, folder 5, p. 109.

-

Julian Tempelaere (1876–1961) knew Fantin-Latour personally, since his father, Gustave, was one of the artist’s key dealers late in his life. Letter from Julien Tempelaere to Paul Gardner, October 17, 1949, NAMA curatorial files. The author is grateful to Brigid M. Boyle, Bloch Family Foundation Doctoral fellow, who first raised questions about the date. Brigid M. Boyle to Mary Schafer, April 22, 2024, NAMA conservation file, 33-15/2.

-

Sophia Boosalis, August 30, 2024, treatment report, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, 33-15/2.

-

Correspondence from Sylvie Brame to Brigid M. Boyle, April 23, 2024, Nelson-Atkins curatorial files, 33-15/2.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Henri Fantin-Latour, Annual Chrysanthemums, 1889,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.516.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Henri Fantin-Latour, Annual Chrysanthemums, 1889,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.516.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Henri Fantin-Latour, Annual Chrysanthemums, 1889,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.516.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Henri Fantin-Latour, Annual Chrysanthemums, 1889,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.516.4033.

With Elizabeth “Ruth” (née Escombe, 1833–1907) Edwards, London, by August 14, 1890–at least 1891 [1];

Barr Smith, Adelaide, Australia, possibly by June 1924 [2];

Sold by Lockett Thomson, Barbizon House, London, 1932 [3];

Mrs. John D., New York, before October 15, 1932 [4];

With Galerie Étienne Bignou, Paris, stock no. 2059, and Bignou Gallery, New York, as Les Marguerites and Chrysanthèmes d’été, by October 15, 1932–February 13, 1933 [5];

Purchased from Bignou, through Knoedler and Co., New York, by The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1933 [6].

Notes

[1] Ruth Edwards and her husband Edwin Edwards (1823–79) were patrons of Fantin-Latour and acted as art dealers for him in London. After her husband’s death in 1879, Ruth Edwards continued to act as his agent, selling his works from her London house in Golden Square and submitting works to the Royal Academy and Society of French Artists. See William Gaunt, “Fantin-Latour: In the Maturity of His Art,” Connoisseur, no. 152 (January–April 1963): 220–22.

The painting was submitted by Edwards to the Eighth Autumn Exhibition at the Corporation of Manchester Art Gallery in 1890 and on August 14, the sub-committee selected it for exhibition. See GB127.M901/Art Galleries Committee: Art Sub-Committee/2–Oct 1888–Mar 1900, Manchester Central Library. Special thanks to Michelle Owen, archives officer, Archives and Local History, Manchester Central Library. Edwards also submitted the painting a year later to The Sixty-Fifth Autumn Exhibition, Royal Birmingham Society of Artists.

[2] “Barr Smith, Adelaide” is cited in the provenance published in Douglas Druick and Michel Hoog, eds., Fantin-Latour, exh. cat. (Paris: Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 1982), 266.

The constituents were probably Robert (1824–1915) and Joanna (1835–1919) Barr Smith, and/or their son, Australian financier and philanthropist, Thomas Elder Barr Smith (1863–1941). Thomas Elder was reported in June 1924 to own two Fantin-Latour flower pieces, although it is unclear which two these may have been. See Howard Ashton, “Our Southern Collections,” Art in Australia 3, no. 8 (June 1924): unpaginated. Thomas Elder had a significant art collection, some of which he had acquired with his wife, Mary Isobel Mitchell (1863–1941), and some of which had been passed down by his parents, Robert and Joanna. The elder Barr Smiths owned five paintings by Fantin-Latour, including four flower pieces that were acquired from the artist through their English friends Edwin and Ruth Edwards. See Sarah Thomas and Angus Trumble, Vive La France!: Hidden Treasures of French Art (1824–1945) from Adelaide Collections, exh. cat. (Adelaide: Art Gallery of South Australia, 1998), 49.

[3] Lockett Thomson (1898–1990) was the director of the art firm Barbizon House, London, which he took over from his father, art critic and dealer David Croal Thomson (1855–1930), after his death. Their art magazine, Barbizon House: An Illustrated Record, reproduced some of the paintings and drawings that were sold from the gallery each year. In the 1932 issue, the Nelson-Atkins painting, entitled Coreopsis, is listed among the works sold from Barbizon House.

[4] According to a handwritten note on a photograph of the painting in the Bignou Gallery albums, the painting was in the “collection Mrs. John D. New York.” See Frick Art Reference Library Archives, New York, Bignou Gallery Albums, MS.024, Album 1: Boudin, Fantin-Latour.

It is possible that Mrs. John D. is Abigail “Abby” Greene Aldrich Rockefeller (1874–1948), wife of American businessman John Davidson Rockefeller Jr. (1839–1937), whom she married in 1901. Mrs. Rockefeller was an avid art collector and the driving force behind the foundation of the Museum of Modern Art, which opened in November 1929. She often lent works anonymously to the Museum of Modern Art under the name Mrs. John D.

[5] See Frick Art Reference Library Archives, New York, Bignou Gallery Albums, MS.024, Album 1: Boudin, Fantin-Latour; and Musée d’Orsay, Paris, Albums BIGNOU ODO 1996-29, Bobine N°20, Boîte 11, Fantin-Latour, Clichés 235–36. For the beginning date of ownership, see letter from Étienne Bignou to M. Knoedler and Co., New York, October 15, 1932, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, M. Knoedler and Co. records, approximately 1848–1971, Series VI.A. General correspondence, 1879–1971, box 568. The letter includes a list of paintings being sent from Bignou in Paris to Knoedler in New York for the “Flowers” by French Painters exhibition, which opened in November 1932.

[6] The painting appears in Knoedler’s Foreign Consignment Book, which records consignments from foreign firms that were received by the Knoedler office in New York. This seems to indicate that while Knoedler was responsible for the sale to the Nelson-Atkins, the painting was still the property of Bignou. See Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, M. Knoedler and Co. records, approximately 1848–1971, Series III Commission books, 1879–1973, box 110, Foreign consignment book 2, 1915 November–1936 October, p. 68, stock no. 838, as Fleurs diverses dans un vase; and Series II. Sales books, box 75, Sales book 15, 1928 January–1944 December, p. 159, stock no. F-838, as Fleurs diverses dans un vase; and box 274, Daybook 1932–33, p. 35, which records the sale and shipment of the painting to the museum in January and February 1933. Thank you to Karen Meyer-Roux, Sally McKay, and Mahsa Hatam of the Getty Archives for their research on our behalf.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Henri Fantin-Latour, Annual Chrysanthemums, 1889,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.516.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Henri Fantin-Latour, Annual Chrysanthemums, 1889,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.516.4033.

Henri Fantin-Latour, Roses in a Cup, 1882, oil on canvas, 14 3/8 x 18 1/8 in. (36.5 x 46 cm), Musée d’Orsay, Paris, RF 1961 25.

Henri Fantin-Latour, Summer Flowers, 1882, oil on canvas, 21 x 24 1/2 in. (53.3 x 62.3 cm), private collection.

Henri Fantin-Latour, Still Life with Roses in a Vase, 1888, oil on canvas, 17 1/4 x 18 in. (43.8 x 45.7 cm), Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1978-1-16.

Henri Fantin-Latour, Larkspur, 1892, oil on canvas, 27 x 23 5/8 in. (68.6 x 57.9 cm), Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, Glasgow, 2139.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Henri Fantin-Latour, Annual Chrysanthemums, 1889,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.516.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Henri Fantin-Latour, Annual Chrysanthemums, 1889,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.516.4033.

The One Hundred and Twenty-Second Exhibition, The Royal Academy of Arts, London, opened May 5, 1890, no. 13, as Chrysanthèmes d’été.

Eighth Autumn Exhibition, Corporation of Manchester Art Gallery, 1890, no. 250, as Chrysanthèmes d’été.

The Sixty-Fifth Autumn Exhibition, Royal Birmingham Society of Artists, UK, 1891, no. 144, as Summer Chrysanthemums.

Possibly The One Hundred and Thirtieth Exhibition, The Royal Academy of Arts, London, 1898, no. 251, as Chrysanthèmes d’été.

“Flowers” by French Painters, Knoedler Galleries, New York, November 1932, no. 6, as Fleurs diverses dans un vase.

The Development of Flower Painting, City Art Museum of Saint Louis (in association with the Associated Garden Clubs of America), May–June 1937, no. 35, as Flowers in a Vase.

Exhibition of Nineteenth-Century French and American Paintings, Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center, April–June 1938, no cat.

Flower Paintings, The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Art, Kansas City, MO, May 14–25, 1950, no cat.

Fine Arts Festival, Allyn Art Gallery, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, February 26–March 10, 1956, no. 8, as Flower Piece.

Flower Paintings, Colorado Springs Fine Art Center, April 10–May 22, 1956, no cat.

Henri Fantin-Latour, 1836–1904, Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton, MA, April 28–June 6, 1966, no. 18, as A Bouquet of Flowers in a Vase.

Fantin-Latour, Galeries nationales du Grand Palais, Paris, November 9, 1982–February 7, 1983; National Gallery of Art, Ottawa, March 17–May 22, 1983; California Palace of the Legion of Honor, San Francisco, June 18–September 6, 1983, no. 102, as Annual Chrysanthemums.

Working Among Flowers: Floral Still-Life Painting in Nineteenth-Century France, Dallas Museum of Art, October 26, 2014–February 8, 2015; Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, March 21–June 21, 2015; Denver Art Museum, July 19–October 11, 2015, no. 26, as Chrysanthemums.

Fantin-Latour: À fleur de peau, Musée du Luxembourg, Paris, September 14, 2016–February 12, 2017; Musée de Grenoble, March 18–June 18, 2017, no. 70, as Chrysanthemums.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Henri Fantin-Latour, Annual Chrysanthemums, 1889,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.516.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Henri Fantin-Latour, Annual Chrysanthemums, 1889,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.516.4033.

Eighth Autumn Exhibition, exh. cat. (Manchester: Corporation of Manchester Art Gallery, 1890), 23, as Chrysanthèmes d’été.

The One Hundred and Twenty-Second Exhibition, exh. cat. (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 1890), 5, as Chrysanthèmes d’été.

Henry Blackburn, Academy Notes: With Illustrations of the Principal Pictures at Burlington House (London: Chatto and Windus, 1890), 5, as Summer Chrysanthemums.

Harry Quilter, “The Art of England: The Royal Academy,” Universal Review 7, no. 25 (May 1890): 45.

“Fine Arts: The Royal Academy (First Notice),” The Athenaeum, no. 3262 (May 3, 1890): 575, as Chrysanthèmes d’Été.

“Royal Academy,” Observer (London) (May 11, 1890): 5.

“Fine Arts: The Royal Academy (Third and Concluding Notice),” The Athenaeum, no. 3265 (May 24, 1890): 680, as Chrysanthèmes d’Été.

Paul Leroi, “Chronique des Expositions: Les trois principales Expositions de Londres,” Courrier de l’art 10, no. 27 (July 4, 1890): 214.

M[arion] H[arry] Spielmann, “Current Art: The Royal Academy—II,” The Magazine of Art 13 (1890): 260.

The Sixty-Fifth Autumn Exhibition, exh. cat. (Birmingham, United Kingdom: Royal Birmingham Society of Artists, 1891), 26, as Summer Chrysanthemums.

Possibly The One Hundred and Thirtieth Exhibition, exh. cat. (London: The Royal Academy of Arts, 1898), 14, as Chrysanthèmes d’été.

Possibly “The Royal Academy,” Times (London), no. 35,516 (May 14, 1898): 16.

Algernon Graves, ed., A Dictionary of Artists who Have Exhibited Works in the Principal London Exhibitions from 1700 to 1893, 3rd ed. (Bath, UK: Kingsmead Reprints, 1901), 95.

[Victoria] Fantin-Latour, Catalogue de l’Œuvre Complet de Fantin-Latour (1849–1904) (Paris: H. Floury, 1911), no. 1373, p. 144, as Chrysanthèmes.

Possibly Howard Ashton, “Our Southern Collections;” and possibly Lionel Lindsay, “Fantin,” Art in Australia 3, no. 8 (June 1924): unpaginated.

Frank Gibson, The Art of Henri Fantin-Latour: His Life and Work (London: Drane’s ltd, 1924), 66.

Lockett Thomson, Barbizon House: An Illustrated Record (London: Barbizon House, 1932), 11, (repro.), as Coreopsis.

“Flowers” by French Painters (XIX–XX Centuries), exh. cat. (New York: Knoedler Galleries, 1932), unpaginated, (repro.), as Fleurs diverses dans un vase.

Margaretta Salinger, “On View at the New York Galleries,” Parnassus 4, no. 6 (November 1932): 9, (repro.), as Fleurs diverses dans un vase.

Edward Alden Jewell, “French Paintings Exhibited at Knoedler’s Ranging From Late in Eighteenth Century to the Present Day,” New York Times 82, no. 27, 317 (November 8, 1932): 28.

Ralph Flint, “Knoedler Holds Important Exhibit of French Flower Paintings Under the Auspices of Étienne Bignou,” Art News 31, no. 7 (November 12, 1932): 10, (repro.), as Fleurs diverses dans un vase.

M[inna] K. P[owell], “In Gallery and Studio,” Kansas City Star 53, no. 196 (April 1, 1933): 5, as Fleurs Diverses dans un Vase.

“Nelson Gallery, Kansas City, Acquires Art Covering Wide Range,” Art Digest 7, no. 13 (April 1, 1933): 7, as Fleurs Diverses dans un Vase.

“Nelson Gallery of Art Special Number,” Art Digest 8, no. 5 (December 1, 1933): 21, as Flower Piece.

“The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art, Kansas City Special Number,” Art News 32, no. 10 (December 9, 1933): 28, 30, 46, (repro), as Flower Piece.

Luigi Vaiani, “Art Dream Becomes Reality with Official Gallery Opening at Hand: Critic Views Wide Collection of Beauty as Public Prepares to Pay its First Visit to Museum,” Kansas City Journal-Post 80, no. 187 (December 11, 1933): 7, as Flower Piece.

The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Handbook of the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1933), 54, 137, (repro.), as Flower Piece.

A. J. Philpott, “Kansas City Now in Art Center Class: Nelson Gallery, Just Opened, Contains Remarkable Collection of Paintings, Both Foreign and American,” Boston Sunday Globe 125, no. 14 (January 14, 1934): 16.

Musical Bulletin 23, no. 3 (December 1934).

The Development of Flower Painting, exh. cat. (Saint Louis, MO: City Art Museum of Saint Louis, 1937), 16, 27, (repro.), as Flowers in a Vase.

M[eyric] R. R[ogers], “The Development of Flower Painting: From the Seventeenth Century to the Present,” Bulletin of the City Art Museum of St. Louis 22 (May 1937): 16, 27, (repro.), as Flowers in a Vase.

Meyric R. Rogers, “Flower Painting Over Four Centuries,” Art News 35, no. 34 (May 22, 1937): 10, (repro.), as Flowers in a Vase.

“Museum Directors Have to Play Detective Now and Then,” Kansas City Star 58, no. 210 (April 15, 1938): 14, as Flower Piece.

The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, The William Rockhill Nelson Collection, 2nd ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1941), 168, as Flower Piece.

“Loan Exhibitions: Flower Paintings,” Gallery News (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Art) 16, no. 8 (May 1950): unpaginated, as Flower Piece.

Fine Arts Festival, exh. cat. (Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University, 1956), unpaginated, as Flower Piece.

Ross E. Taggart, ed., Handbook of the Collections in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 4th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1959), 260, Flower Piece.

Fantin-Latour, 1836–1904: An Exhibition Organized by the Smith College Museum of Art (Northampton, MA: Smith College of Art, 1966), unpaginated, as A Bouquet of Flowers in a Vase.

Frank Anderson Trapp, “Fantin-Latour at Smith College,” Burlington Magazine 108, no. 760 (July 1966): 394, as A Bouquet of Flowers in a Vase.

Ellen Goheen, “From Romanticism to Pop,” Apollo 96, no. 130 (December 1972): 544, (repro.), as Flower Piece.

Ross E. Taggart and George L. McKenna, eds., Handbook of the Collections in The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Kansas City, Missouri, vol. 1, Art of the Occident, 5th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1973), 159, (repro.), as Flower Piece.

Edward Lucie-Smith, Fantin-Latour (Oxford: Phaidon, 1977), 150, 159, (repro.), Flower-piece.

Harry A. Broadd, “The Floral Motif in Still Life,” Arts and Activities 86, no. 1 (September 1979): 38–39, 74, as Flower Piece.

Douglas Druick and Michel Hoog, eds., Fantin-Latour, exh. cat. (Paris: Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 1982), 50, 268–70, (repro.), as Annual Chrysanthemums.

Paul J. Karlstrom, “Henri Fantin-Latour, master of ‘persistence before nature,’” Smithsonian Magazine 14, no. 4 (July 1983): 72 (repro.), as Annual Chrysanthemums.

Elisabeth Hardouin-Fugier, “Fantin-Latour, peintre de fleurs,” Gazette Des Beaux-Arts 113, no. 1442 (March 1989): 140.

Roger Ward and Patricia J. Fidler, eds., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collection (New York: Hudson Hills Press, in association with Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1993), 211, (repro.), as Chrysanthemums.

Alice Thorson, “Uncover the Painting, Discover the Past: Restoring Artwork Can Be a Touchy Job for This Conservator,” Kansas City Star (June 9, 1998): E1, as Chrysanthemums.

Koji Ariki, Fantin-Latour: Retrospective Exhibition, exh. cat. (Utsunomiya-shi, Japan: Utsunomiya Museum of Art, 1998), 278, 280, as Chrysanthèmes d’été.

Kirk Richards and Stephen Gjertson, For Glory and For Beauty: Practical Perspectives on Christianity and the Visual Arts (Minneapolis, MN: Bruce Printing, 2002), 139, (repro.), as Chrysanthemums.

Valérie M. C. Bajou, “Fantin-Latour family,” Grove Art Online (2003): https://doi.org/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T027517.

Yves Bourel et al., Fantin-Latour: De la Réalité au Rêve, exh. cat. (Lausanne: Bibliothèque des arts, 2007), 79.

Deborah Emont Scott, ed., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collection, 7th ed. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2008), 124, (repro), as Chrysanthemums.

Vincent Pomarède et al., Henri Fantin-Latour (1836–1904), exh. cat. (Madrid: Colección Thyssen-Bornemisza, 2009), 177, 259, as Crisantemos anuales (Chrysanthèmes Annuels).

Heather MacDonald and Mitchell Merling, Working Among Flowers: Floral Still-Life Painting in Nineteenth-Century France, exh. cat. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015), 110, 112, (repro.), as Chrysanthemums.

Guillaume Morel, “Henri Fantin-Latour: Coin de table,” Connaissance des Arts, no. 751 (September 2016): 79.

Laure Dalon, Fantin-Latour: À fleur de peau, exh. cat. (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 2016), 130, 140–41, (repro.), as Chrysanthemums.

Laure Dalon, Henri Fantin-Latour, 1836–1904: Journal de l’Artiste, l’Album de l’Exposition, exh. cat. (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 2016), 34–35, (repro.), as Chrysanthèmes.

Sylvie Brame and François Lorenceau, Henri Fantin-Latour, cat. rais. (Paris: Brame et Lorenceau, forthcoming).