![]()

Attributed to Honoré Daumier, Exit from the Theater, after 1863

| Artist | Attributed to Honoré Daumier, French, 1808–79 |

| Title | Exit from the Theater |

| Object Date | after 1863 |

| Alternate and Variant Titles | Au Théâtre; Sortie du Theatre; L’Attente |

| Medium | Oil on panel |

| Dimensions (Unframed) | 12 13/16 x 16 1/8 in. (32.7 x 41 cm) |

| Signature | Signed lower left: h. D |

| Credit Line | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 32-31 |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “Attributed to Honoré Daumier, Exit from the Theater, after 1863,” catalogue entry in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.512.5407.

MLA:

Marcereau DeGalan, Aimee. “Attributed to Honoré Daumier, Exit from the Theater, after 1863,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.512.5407.

Forgeries after Daumier’s prints are an acknowledged problem.5Forgeries began in earnest following the 1889 Exposition Centennale, which drove prices higher and attracted many forgers. See K. E. Maison, “Daumier’s Paintings and Drawings,” in Daumier Paintings and Drawings, exh. cat. (London: Arts Council of Great Britain, 1961), 18–19. These fraudulent works capitalized on accepted subject matter and misunderstandings of the artist’s technical development and process in response to increasing market demands for his work. A plethora of weak copies, with variations after well-known compositions, were the result. Bruce Laughton, a leading recent authority on Honoré Daumier, strongly questioned the attribution of Exit from the Theater to Daumier on these grounds, although he never saw the work in person.6See letter from Simon Kelly, former associate curator, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, to Bruce Laughton, December 27, 2008, NAMA curatorial files. Subsequent scholars have generally deferred to his opinion, and as a result the painting has spent more than twenty years off view in storage awaiting further study.

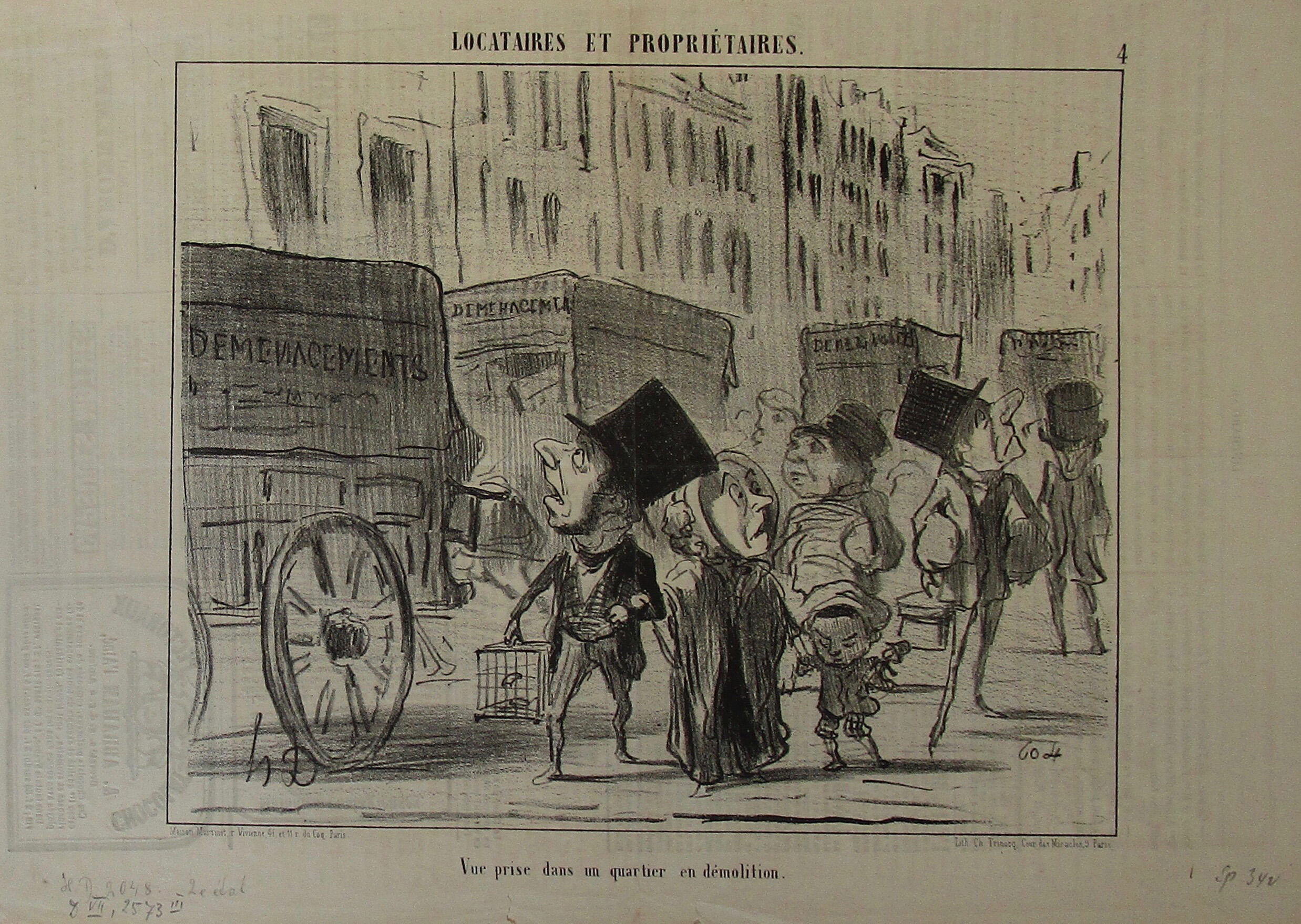

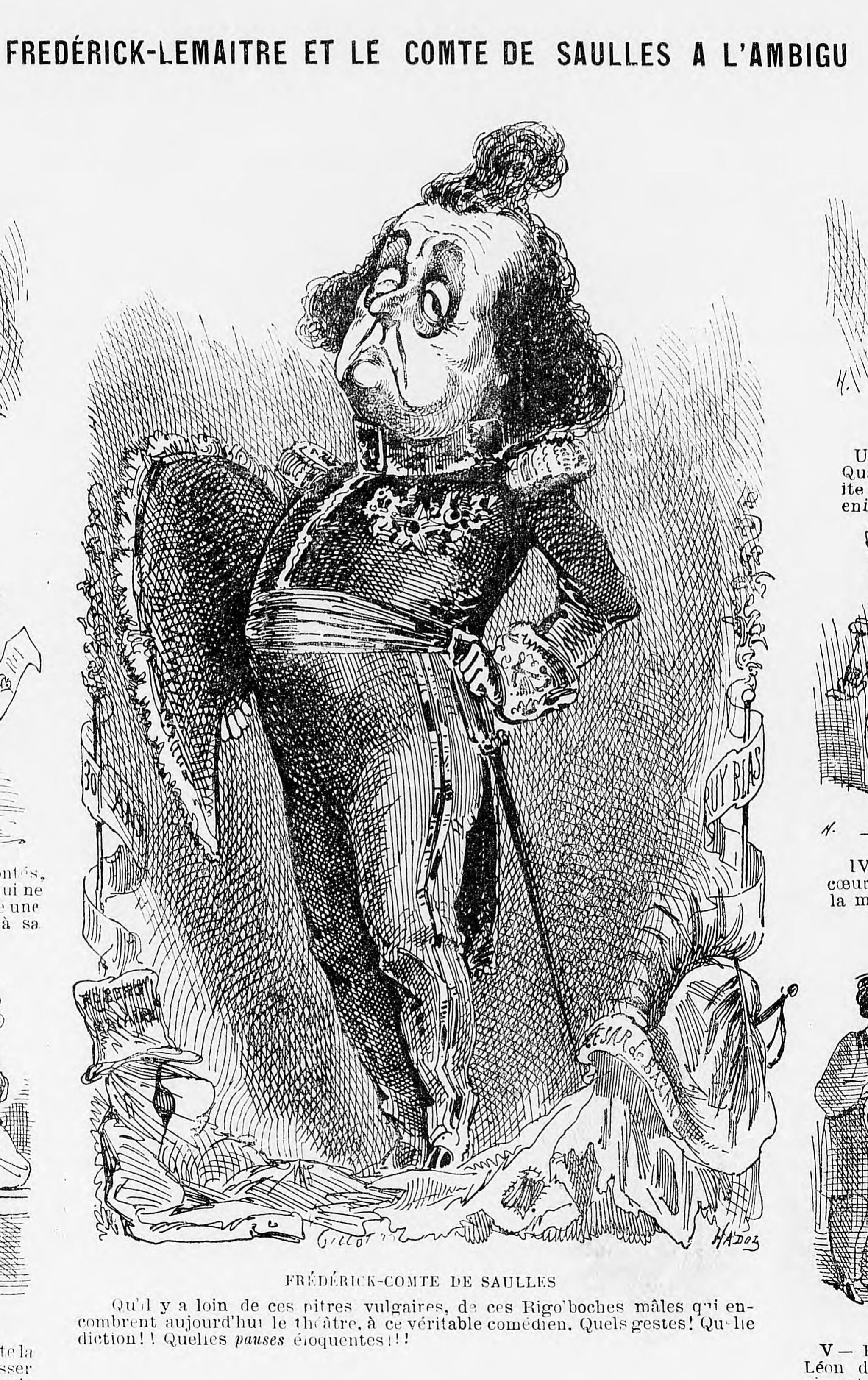

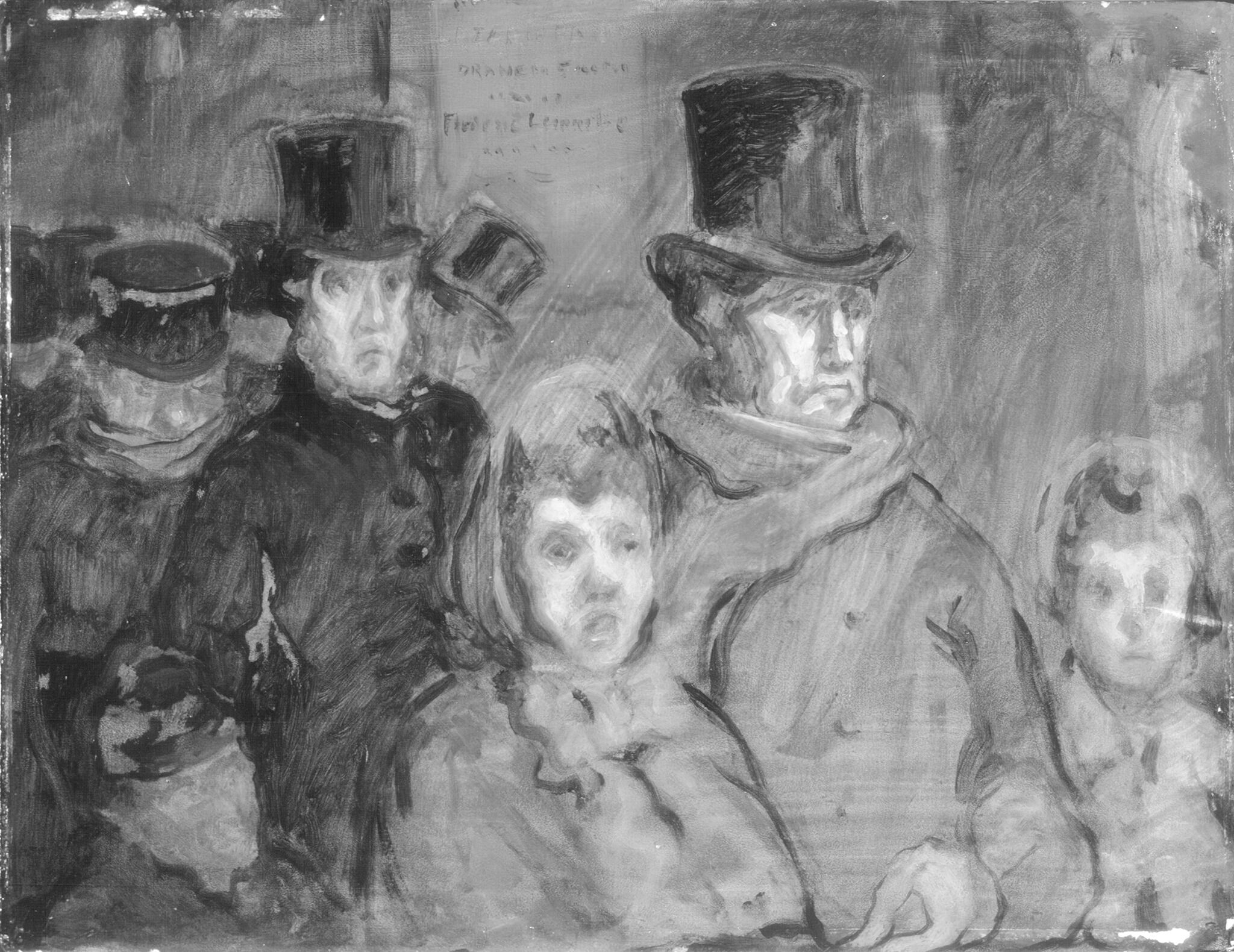

Counterpoints to Laughton’s opinion emerge from several different areas. To start, Exit from the Theater is not a direct copy of Boulevard du Temple à Minuit but rather an adaptation, with critical differences that play off of and inform one another. The painting presents a single group of theatergoers exiting a sobering performance, whereas the print features two groups of theatergoers: those at left, who exit a drama, and those at right, who exit a comedy or some other kind of lighthearted fare. This is evident not only by the stark contrasts of the facial expressions of the two groups but also by the accompanying captions in the print: “Sortant du Drame” (exiting a drama) and “Sortant des Funambules” (exiting the Funambules). “Funambules” literally translates to “tightrope walkers,” but here it probably refers to an actual place, the Théâtre des Funambules on the famed Boulevard du Temple. The theater was associated with the early career of Frédérick LeMaître (1800–76), who went on to become a great classical actor. His name appears in the playbill in the background of the Nelson-Atkins painting, which reads “Lazare le Patre, Drame en Cinq Actes, Frederic Lemaître.” Lazare le Pâtre (Lazarus the Shepherd), however, was four acts, not five, and LeMaître did not perform in it.7See email from Cindy Kang, contract researcher, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, to Nicole R. Myers, former associate curator, NAMA, February 2012, NAMA curatorial files. Kang and Myers consulted archival records at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BnF) and the Arts du Spectacle. The play premiered at the Théâtre Ambigu in November of 1840, which by then was no longer operating on the Boulevard du Temple. See Marie-Noëlle, La Musique à Paris en 1830–1831 (Paris: Bibliothèque Nationale de France, 1983), 79. Is the erroneous playbill the mark of a slipshod copyist who did not know theater history? Or was the reference to LeMaître a subtle, yet intentional clue, pointing to a deeper meaning?8As Mary Schafer and John Twilley have shown in the accompanying technical entry, the lettering on the playbill in the Nelson-Atkins painting is original to the painting, and thus not an addition by a later hand.

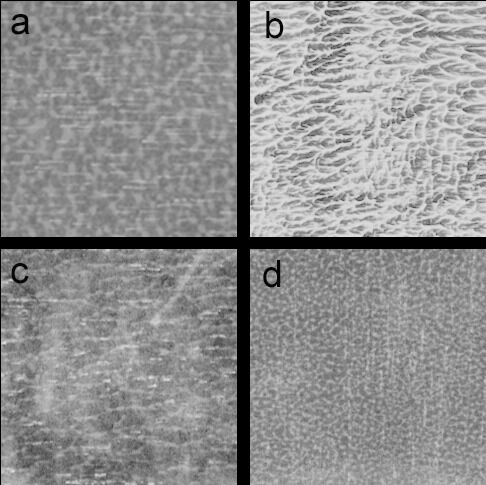

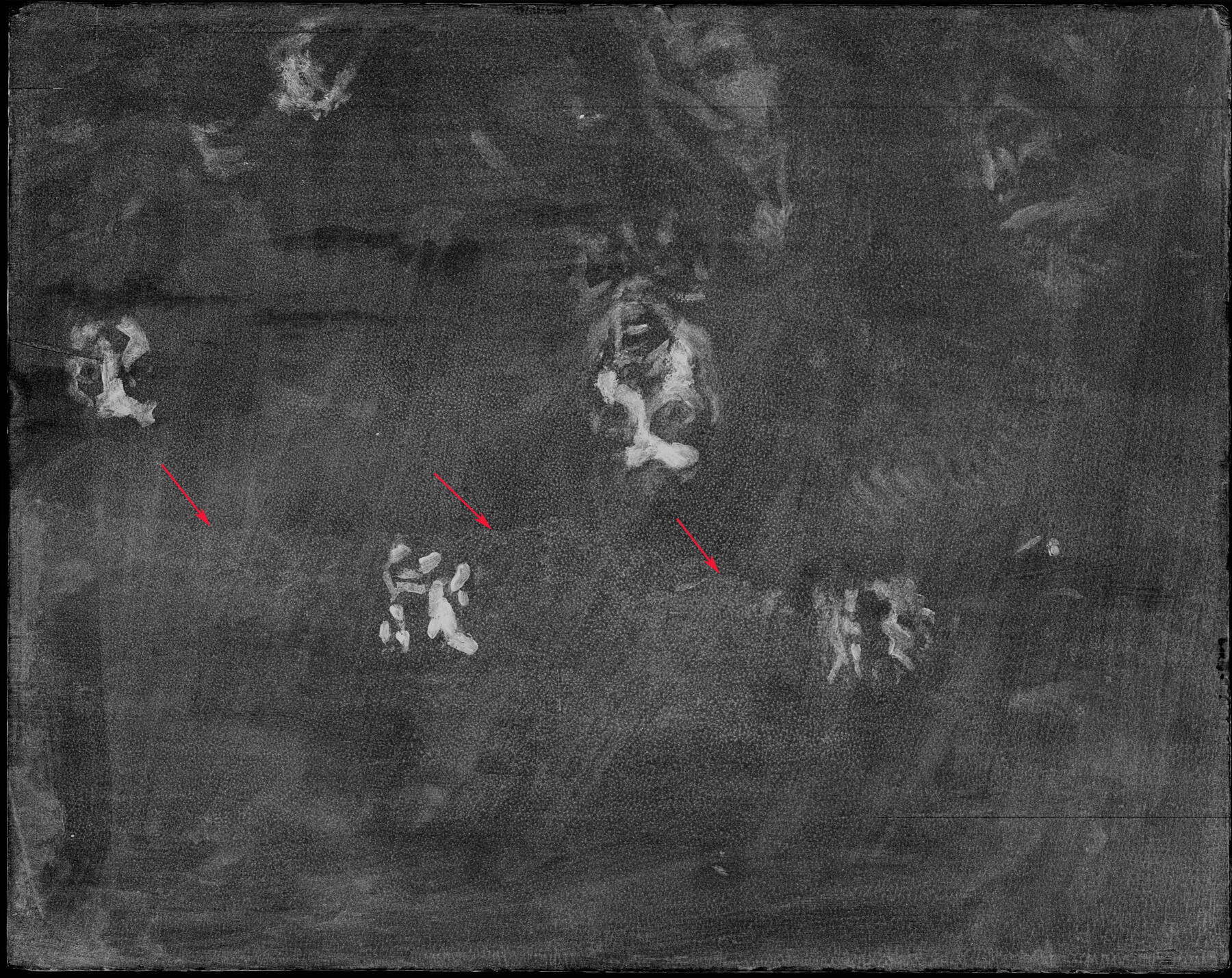

Structure was important to Daumier, and he attempted to render the plastic forms of his compositions’ principal elements through a series of successive thin washeswash: An application of thin paint that has been diluted with solvent. placed over his initial linear designs. He often redrew his original outlines, as other scholars have shown, in materials associated more with drawing than with painting—charcoal, ink, lithographylithography: Invented by Alois Senefelder (German, 1771–1834) in the late eighteenth century, lithography is a planographic printmaking technique. The name (literally: stone drawing) comes from the use of a stone as the printing matrix; however, grained aluminum and metal plates are also used. Preparation and printing of the images is a based on the hydrophobic nature of grease. The design is drawn with greasy crayons or an oily ink called tusche. The stone is then synthesized so that printing can be accomplished by first wetting the stone (the water is repelled by the grease in the media) and then inking the stone with a greasy ink (the ink adheres grease in the crayon and tusche). The image is transferred to the paper with a press that exerts tremendous pressure on the stone. Like other printing techniques the printed image reverses the image on the stone. There is no platemark as seen in monotypes; instead the area of contact between the stone and the paper will have a flatter appearance than the surrounding paper. crayon, or water-based media—in an effort to maintain structural clarity and articulate details within his forms.15See Aviva Burnstock and William Bradford, “An Examination of the Relationship between the Materials and Techniques used for Works on Paper, Canvas, and Panel by Honoré Daumier,” in Painting Techniques: History, Materials and Studio Practice; Contributions to the Dublin Congress, 7–11 September 1998 (London: International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works, 1998), 217–22. Although paintings conservator Mary Schafer and Mellon scientist John Twilley did not find such drawing materials in the Nelson-Atkins painting, as confirmed in the accompanying technical essay, they did find evidence of double lines from a quill or reed pen scored into the wet groundground layer: An opaque preparatory layer applied to the support, either commercially or by the artist, to prevent absorption of the paint into the canvas or panel. See also priming layer. around the edge of the central male figure’s cheek, scarf, and top hat (see Technical Entry, Fig. 9).16See the accompanying technical entry by Schafer and Twilley. They also discovered that Daumier used a printmaker’s brayer, or ink roller, in the application of his ground (see Technical Entry, Figs. 7, 8).17See the accompanying technical entry by Schafer and Twilley, as well as Louisa Smieska, John Twilley, Arthur Woll, Mary Schafer, and Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “Energy-Optimized Synchrotron XRF Mapping of an Obscured Painting Beneath Exit from the Theater, attributed to Honoré Daumier,” Microchemical Journal 146 (May 2019): 679–91, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.microc.2019.01.058. On at least two additional occasions, as Schafer and Twilley have shown, Daumier utilized a brayer in the production of an oil painting, a technique that produced the stipple-like texture revealed by radiographsX-ray radiography (also referred to as x-radiography or radiography): Radiography is an examination tool analogous to the use of X-rays in medicine whereby denser components of a painted composition can be recorded as an inverted shadow image cast on film or a digital X-ray imaging plate from a source such as an X-ray tube. The method has been used for more than a century and is most effective with dense pigments incorporating metallic elements such as lead or zinc. It can reveal artist changes, underlying compositions, and information concerning the artwork’s construction and condition. The resulting image is called an x-radiograph or radiograph. It differs from the uses of X-ray spectrometry in being dependent on the density of the paint to absorb X-rays before they reach the film or image plate and being non-specific as to which elements are responsible for the resulting shadow image..18The two paintings unquestionably by Daumier that also reveal the use of the brayer are The Print Collector (ca. 1857–63; Art Institute of Chicago) and French Theater (ca. 1856; National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC). In the case of the Nelson-Atkins panel, Schafer and Twilley believe that “the texture may have had the additional advantage of reducing the visibility of brushstrokes associated with the discovery of an underlying landscape beneath Exit from the Theater by a different hand” (see their accompanying technical report). As the pigments utilized in the construction of the underlying painting are consistent with the time frame proposed for Exit from the Theater, I have chosen not to deal with it directly in this essay. For more on the underlying painting’s history and process of discovery, see Smieska et al., “Energy-Optimized Synchrotron XRF Mapping.” Due to the built-up layers of oil and varnish used to model Exit from the Theater, this subtle texture within the ground layer is not visible on the painting’s surface, and therefore not likely to be the result of duplication by a forger.

Censorship laws in France from 1835 to 1848 and starting again with the reign of Napoleon III in 1852 prohibited caricatures of political subjects; however, as Judith Wechsler has shown, they met with varying degrees of enforcement.20Judith Wechsler, “Daumier and Censorship, 1866–1872,” Yale French Studies, no. 122 (2012): 53–78, at 54. Authority for censorship laws shifted in 1858 and then again in 1860, when the duc de Persigny, a loyal follower of Napoleon III, became responsible for the enforcement of civil law.21Wechsler, “Daumier and Censorship,” 54. As the government did not outline the changing rules of censorship, artists and writers had to tread carefully in delivering their antigovernment messages or else risk fines, suppression, or even imprisonment.22Henry Zeldin, France 1848–1945, vol. 2, Intellect, Taste and Anxiety (Oxford, 1977), 547, cited in Wechlser, “Daumier and Censorship,” 54. See also the act of February 17, 1852, Article 22, which spells out the censorship laws: Gustave Rousset, Code general des lots sur la presse et autre moyen de publication (Paris, 1869), 223, as cited in Wechsler, 54n1. Daumier, who had always understood the theater as a powerful vehicle for the delivery of social messages, utilized the stage and other forms of spectacle to help wage this battle, not only specifically with what he saw as the destruction of his beloved city and the displacement of its urban and mostly poor residents but also more broadly against Napoleon III’s regime. In the case of the Nelson-Atkins painting, he specifically summoned the name and reputation of the actor Frédéric LeMaître, who was associated with antigovernment positions both personally and professionally.

All of this assumes, of course, that the Nelson-Atkins painting is an autograph work, by Daumier himself. While forgeries after Daumier’s prints are commonplace and reveal a lack of understanding of the artist’s technical development and process, when considered in a different light—in this instance, quite literally under greater illumination and through extensive technical study—the Nelson-Atkins painting presents new evidence to counter old questions of attribution. Foremost among them is the artist’s use of printmaking tools, including the unusual use of a brayer to apply the ground—a technique not visible on the surface or acknowledged in publication prior to the 1932 acquisition by the Nelson-Atkins, and thus not something a forger would ever know. The painting also presents subtle yet important variations from the print—rather than being a direct copy of it—as well as evidence of an artist who utilized the stage and other forms of spectacle to wage battle with government in an era of heightened censorship. In this new and clarifying light, it is time, after twenty years, to reconsider this painting anew.

Notes

-

The image, engraved by Charles Maurand, is also known as Sortant du Drame et Sortant des Funambules. Reprints appeared in the Journal Illustré on March 19, 1865, and in Presse Illustré on March 1, 1868.

-

The spelling of Junger[s]’s name varies, but is most often found as Jungers. See the provenance section of this entry for further details. Junger[s?] (d. 1934, Paris), may have owned the work as early as May 1923, when the painting may have been exhibited at the Exposition Daumier et Gavarni, Maison de Victor-Hugo, Paris, May–July 1923. The catalogue featured eleven Daumier paintings in the collection of Jungers. The Nelson-Atkins acquired several pictures with this dual Jungers/Owen provenance, a number of which have subsequently lost their attribution. See unknown artist, probably French, View in Italy, ca. 1850, https://nelson-atkins.org/fpc/nineteenth-century-realism-barbizon/518. Jungers brokered at least three other Daumier pictures whose attributions have held. See K. E. Maison, Honoré Daumier: Catalogue Raisonné of the Paintings, Watercolours, and Drawings (London: Thames and Hudson, 1968), nos. I-7, I-172, and I-194, pp. 54, 146, 158. That neither Fuchs nor Maison included the Nelson-Atkins painting in their catalogues does not imply that the work is a forgery. The painting also does not appear in their respective sections of known forgeries, suggesting that they simply were not aware of the painting at the time they wrote their respective publications.

-

I use the term “unknown to Daumier’s cataloguers” because if they had known about the work and did not believe it to be autograph, they would have included it in their respective forgeries’ sections of their publications. Edward Fuchs, Der Maler Daumier (E. Weyhe, New York, 1927); and Maison, Honoré Daumier: Catalogue Raisonné.

-

See letter from Ebria Feinblatt, curator of prints and drawings, Los Angeles Museum of History, Science and Art, to Patrick Kelleher, former curator of European art, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, October 2, 1958, NAMA curatorial files. Although Feinblatt never saw the painting in person, she wrote to Kelleher that the painting was undoubtedly a forgery based on the artist’s print of 1863.

-

Forgeries began in earnest following the 1889 Exposition Centennale, which drove prices higher and attracted many forgers. See K. E. Maison, “Daumier’s Paintings and Drawings,” in Daumier Paintings and Drawings, exh. cat. (London: Arts Council of Great Britain, 1961), 18–19.

-

See letter from Simon Kelly, former associate curator, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, to Bruce Laughton, December 27, 2008, NAMA curatorial files.

-

See email from Cindy Kang, contract researcher, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, to Nicole Myers, former associate curator, NAMA, February 2012, NAMA curatorial files. Kang and Myers consulted archival records at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BnF) and the Arts du Spectacle. The play premiered at the Théâtre Ambigu in November of 1840, which by then was no longer operating on the Boulevard du Temple. See Marie-Noëlle, La Musique à Paris en 1830–1831 (Paris: Bibliothèque Nationale de France, 1983), 79.

-

As Mary Schafer and John Twilley have shown in the accompanying technical entry, the lettering on the playbill in the Nelson-Atkins painting is original to the painting, and thus not an addition by a later hand.

-

As noted by Schafer and Twilley in the accompanying technical entry.

-

As observed by Elizabeth Childs, department chair, Etta and Mark Steinberg Professor of Art History, 19th and 20th Century European Modernism, Washington University, St. Louis, during her visit to the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, December 11, 2017. I am extremely grateful to Dr. Childs for sharing her critical assessment of the painting and agreeing to go on record.

-

Childs visit to the Nelson-Atkins, December 11, 2017.

-

See accompanying technical entry by Schafer and Twilley.

-

Childs visit to the Nelson-Atkins, December 11, 2017. It is important to note that Childs does not outright accept the Nelson-Atkins painting as autograph Daumier, but rather finds that select passages, when better illuminated, bear more resemblance to Daumier’s hand than previously acknowledged.

-

Childs visit to the Nelson-Atkins, December 11, 2017.

-

See Aviva Burnstock and William Bradford, “An Examination of the Relationship between the Materials and Techniques used for Works on Paper, Canvas, and Panel by Honoré Daumier,” in Painting Techniques: History, Materials and Studio Practice; Contributions to the Dublin Congress, 7–11 September 1998 (London: International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works, 1998), 217–22.

-

See the accompanying technical entry by Schafer and Twilley.

-

See the accompanying technical entry by Schafer and Twilley, as well as Louisa Smieska, John Twilley, Arthur Woll, Mary Schafer, and Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “Energy-Optimized Synchrotron XRF Mapping of an Obscured Painting Beneath Exit from the Theater, attributed to Honoré Daumier,” Microchemical Journal 146 (May 2019): 679–91, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.microc.2019.01.058.

-

The two paintings unquestionably by Daumier that also reveal the use of the brayer are The Print Collector (ca. 1857–63; Art Institute of Chicago) and French Theater (ca. 1856; National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC). In the case of the Nelson-Atkins panel, Schafer and Twilley believe that “the texture may have had the additional advantage of reducing the visibility of brushstrokes associated with the discovery of an underlying landscape beneath Exit from the Theater by a different hand” (see their accompanying technical report). As the pigments utilized in the construction of the underlying painting are consistent with the time frame proposed for Exit from the Theater, I have chosen not to deal with it directly in this essay. For more on the underlying painting’s history and process of discovery, see Smieska et al., “Energy-Optimized Synchrotron XRF Mapping.”

-

Napoleon III’s new vision for the city allowed for the expropriation of private property to create new streets through the existing urban core. As part of this plan, the Boulevard du Temple was demolished in an effort to link the Place du Château-d’Eau (today “Place de la République”) to the Place du Trône (today “Place de la Nation”). For more on Napoleon III’s efforts to modernize Paris, see David Jordan, Transforming Paris: The Life and Labors of Baron Haussmann (New York: Free Press, 1995); and David Harvey, Capital of Modernity (New York: Routledge, 2003).

-

Judith Wechsler, “Daumier and Censorship, 1866–1872,” Yale French Studies, no. 122 (2012): 53–78, at 54.

-

Wechsler, “Daumier and Censorship,” 54.

-

Henry Zeldin, France 1848–1945, vol. 2, Intellect, Taste and Anxiety (Oxford, 1977), 547, cited in Wechlser, “Daumier and Censorship,” 54. See also the act of February 17, 1852, Article 22, which spells out the censorship laws: Gustave Rousset, Code general des lots sur la presse et autre moyen de publication (Paris, 1869), 223, as cited in Wechsler, 54n1.

-

Lemaître played Macaire—a redevelopment of a character from Benjamin Antier, Saint-Amand and Paulyanthe’s play L’Auberge des Adrets—as a financial schemer that lampooned financial speculation and government corruption; he became a thinly veiled stand-in for King Louis Philippe. This new play was a satire on Louis Philippe’s July Monarchy and its financial oligarchy, with a central thesis of unmaking the bourgeoisie in power. It premiered in 1835 and was a wild success. See Stanislav Osiankovski, “History of Robert Macaire and Daumier’s Place in It,” Burlington Magazine 100, no. 668 (November 1958): 388–93. See also David S. Kerr, Caricature and French Political Culture 1830–1848: Charles Philipon and the Illustrated Press (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 41–42.

-

Frédéric Lemaître created the title role in Balzac’s Vautrin, which premiered in 1840. Lemaître played the role in a comedic way and wore a wig shaped like a pyramid, which was associated with the well-known toupee worn by Louis Philippe. See Mary F. Sandars, Honoré de Balzac, His Life and Writings, 2nd ed. (New York: Dodd, Mead, 1905), 237–41.

-

For more information concerning censorship during the Second Empire, see Judith Wechsler, “Daumier and Censorship”; see also Robert Justin Goldstein, “Censorship of Caricature and the Theater in Nineteenth-Century France: An Overview,” Yale French Studies, no. 122 (2012): 14–36; and Elizabeth Childs, “The Body Impolitic: Censorship and the Caricature of Honoré Daumier,” in Suspended License: Censorship and the Visual Arts (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1997), 151–89. For the ban on the Robert Macaire play, see John McCormick, Popular Theatres of Nineteenth Century France (London: Routledge, 1993), 106.

-

Osiankovski, “History of Robert Macaire,” 389.

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Mary Schafer and John Twilley, “Attributed to Honoré Daumier, Exit from the Theater, after 1863,” technical entry in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.512.2088.

MLA:

Schafer, Mary, and John Twilley. “Attributed to Honoré Daumier, Exit from the Theater, after 1863,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.512.2088.

Exit from the Theater, an oil on panel attributed to Honoré Daumier (1808–79), depicts a group of audience members departing a dramatic evening performance. The composition corresponds to the left half of Boulevard du Temple à Minuit (Fig. 1), an engraving after Daumier by Charles Maurand (1824–1904) that was first published in Le Monde Illustré in 1863. Acquired in 1932 as an authentic painting by Daumier, doubts about Exit from the Theater surfaced in 1958. Several historical inaccuracies were identified in the painted playbill, and the question of whether Daumier would have painted an abbreviated version of the Maurand engraving was raised. The painting’s lack of provenance before 1923 and its absence from the 1930 and 1968 catalogues raisonnés only deepened the uncertainty.1See accompanying catalogue entry by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan for an overview of the painting’s provenance and early questions regarding its authenticity.

Paintings that exist outside of Daumier’s accepted oeuvre require a cautious approach to authenticity and chronology due to a number of complicating factors. While his lithographs can be dated based on their publication in newspapers, definitive dates for his oil paintings are rare. Another obstacle is the large number of forgeries that exist, some materializing within Daumier’s own lifetime.2Karl Eric Maison, Honoré Daumier, Catalogue Raisonné of the Paintings, Watercolors, and Drawings. (London: Thames and Hudson, 1968), 1:37. See also Douglas Campbell and Usher Caplan, eds., Daumier 1808-1879 (Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada, 1999), 30. Unfinished works in the artist’s studio at the time of his death were completed by later hands with the addition of signatures.3Campbell and Caplan, eds., Daumier 1808-1879, 27. In other instances, some autograph paintings have been irreversibly altered by restoration campaigns. It is also important to recognize Daumier’s unevenness as a painter, reflected in late nineteenth-century descriptions of his work that range from “a remarkable energy, sureness of palette, and tonal intensity” to “‘rather laborious execution,’ technical deficiencies, and problems of completion.”4Edmond Duranty, “Études sur Daumier,” Gazette des beaux-arts 17, 2nd ser., no. 6 (June 1878): 539 and N[oéme] C[adiot], “L’Exposition de Daumier,” Courrier du soir (May 24, 1878): 2, respectively, as cited and translated in Campbell and Caplan, eds., Daumier 1808–1879, 13. In light of these many challenges, recent technical studies of authentic Daumier paintings have introduced critical information about the artist’s materials and technique that served as a point of comparison in the technical study of the Nelson-Atkins painting.5The authors are grateful to former Nelson-Atkins curators Simon Kelly and Nicole R. Myers, and conservation scientist Johanna Bernstein for their contributions in the early stages of this research project.,6Results from the technical study were disseminated in two prior publications. See Louisa M. Smieska, John Twilley, Arthur R. Woll, Mary Schafer, and Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “Energy-optimized Synchrotron XRF Mapping of an Obscured Painting beneath Exit from the Theater, Attributed to Honoré Daumier,” Microchemical Journal 146 (2019): 679-91. Mary Schafer, John Twilley, Louisa Smieska, Arthur Woll, and Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “Technical Study of a Painting Attributed to Honoré Daumier at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art” AIC Paintings Specialty Group: Postprints; Papers Presented at the 47th Annual Meeting, New England (Washington, DC: American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works, 2021), 101–24.

Daumier struggled financially and occasionally repurposed materials for his drawing and painting supports.9Campbell and Caplan, eds., Daumier 1808-1879, 23. Two Daumier works in the collection of the Musée d’Orsay—Le Baiser (ca. 1845) and Martyrdom of Saint Sébastian (ca. 1849)—were painted on panels that were once part of a cabinet or other piece of furniture.10EROS database 2.0, Department of Archives and Innovative Information Technology, Center for Research and Restoration of Museums of France, F13445 and F10969, accessed August 7, 2011.,11Campbell and Caplan, eds., Daumier 1808-1879, 23. Notably, there are also examples in which Daumier repurposed the painting supports of other artists. The Uprising (1848 or later; Phillips Collection, Washington, DC) was executed on top of a discarded canvas featuring a portrait from a much earlier period,12Elizabeth Steele, paintings conservator, Phillips Collection, noted in her 1999 examination report that the underlying portrait “does not bear any resemblance to any style of painting by Daumier, but rather, appears to be from a much earlier period (17th–19th century).” and in another instance, Daumier reused the reverse side of a watercolor fragment painted by another artist.13See Campbell and Caplan, eds., Daumier 1808-1879, 23.

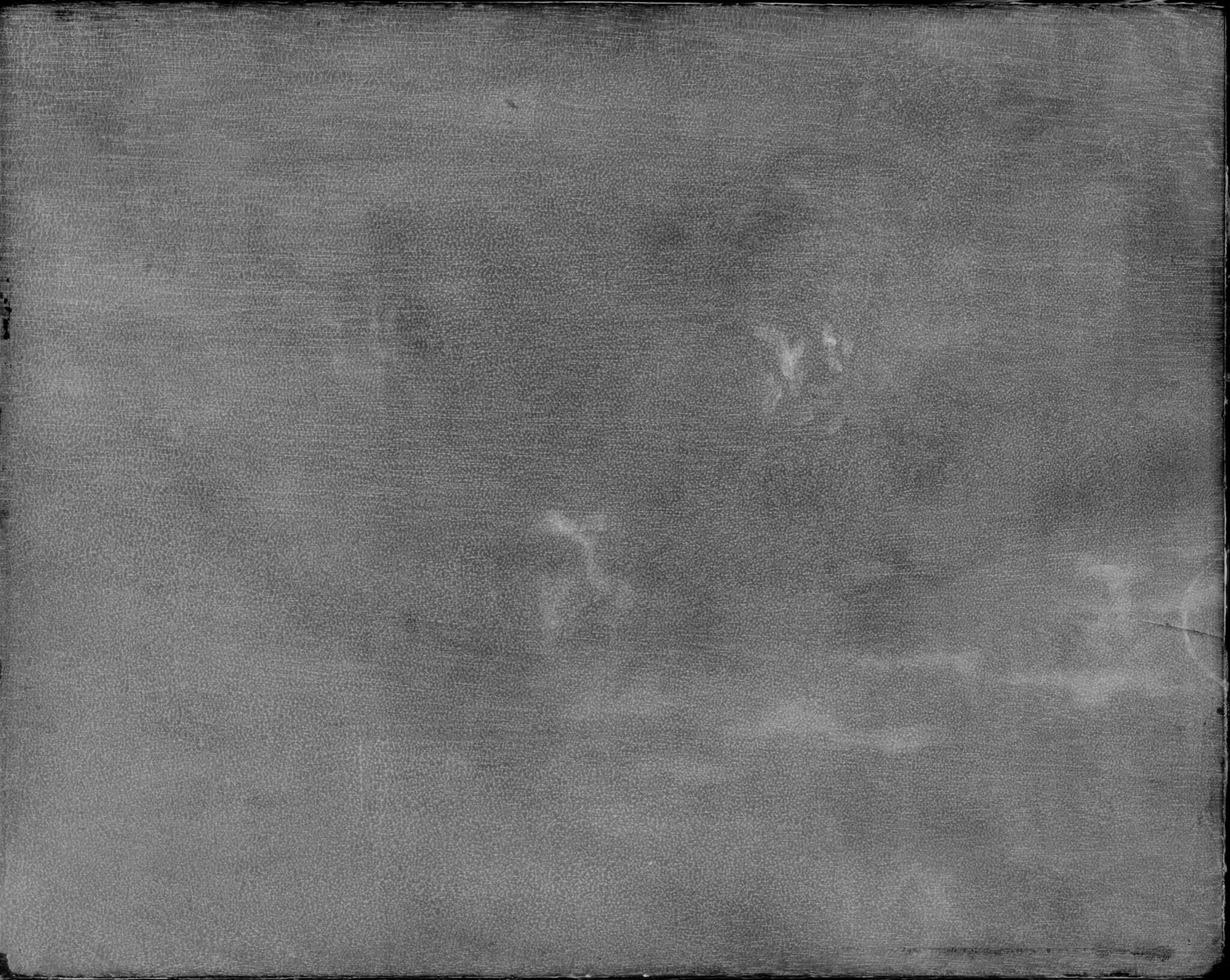

Fig. 7. Radiograph of Exit from the Theater (after 1863)

Fig. 7. Radiograph of Exit from the Theater (after 1863)

Figs. 8a–d. 8a. radiograph detail of Fig. 7, Exit from the Theater (after 1863); 8b. test panel with brayer-applied lead white; 8c. The Print Collector (ca. 1857/1863; Art Institute of Chicago, 1957.305); 8d. French Theater (ca. 1856; National Gallery of Art, Washington DC, 1963.10.13). Brighter pixels correlate to radio-opaque material. Each field of view is 2 centimeters.

Figs. 8a–d. 8a. radiograph detail of Fig. 7, Exit from the Theater (after 1863); 8b. test panel with brayer-applied lead white; 8c. The Print Collector (ca. 1857/1863; Art Institute of Chicago, 1957.305); 8d. French Theater (ca. 1856; National Gallery of Art, Washington DC, 1963.10.13). Brighter pixels correlate to radio-opaque material. Each field of view is 2 centimeters.

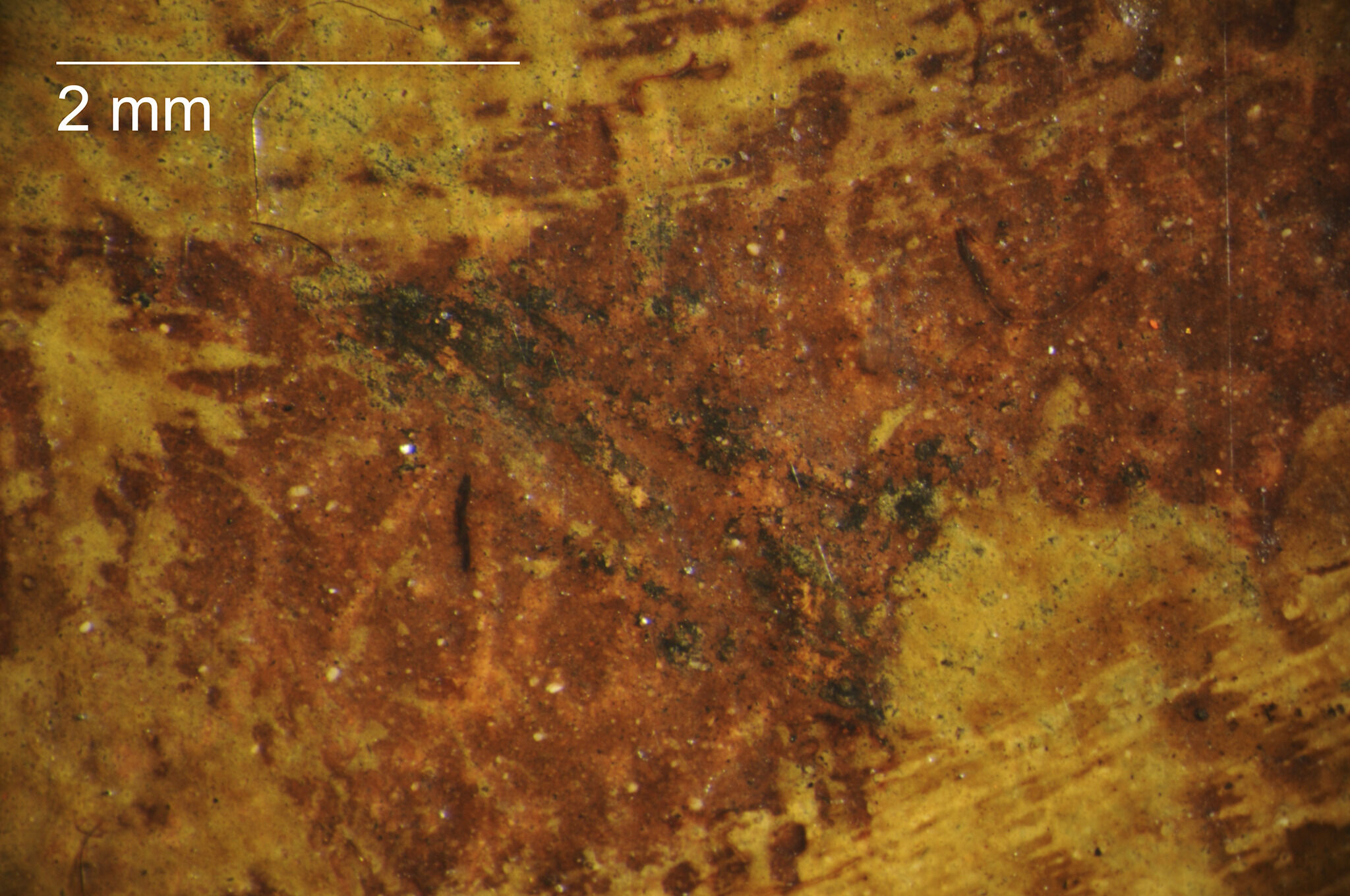

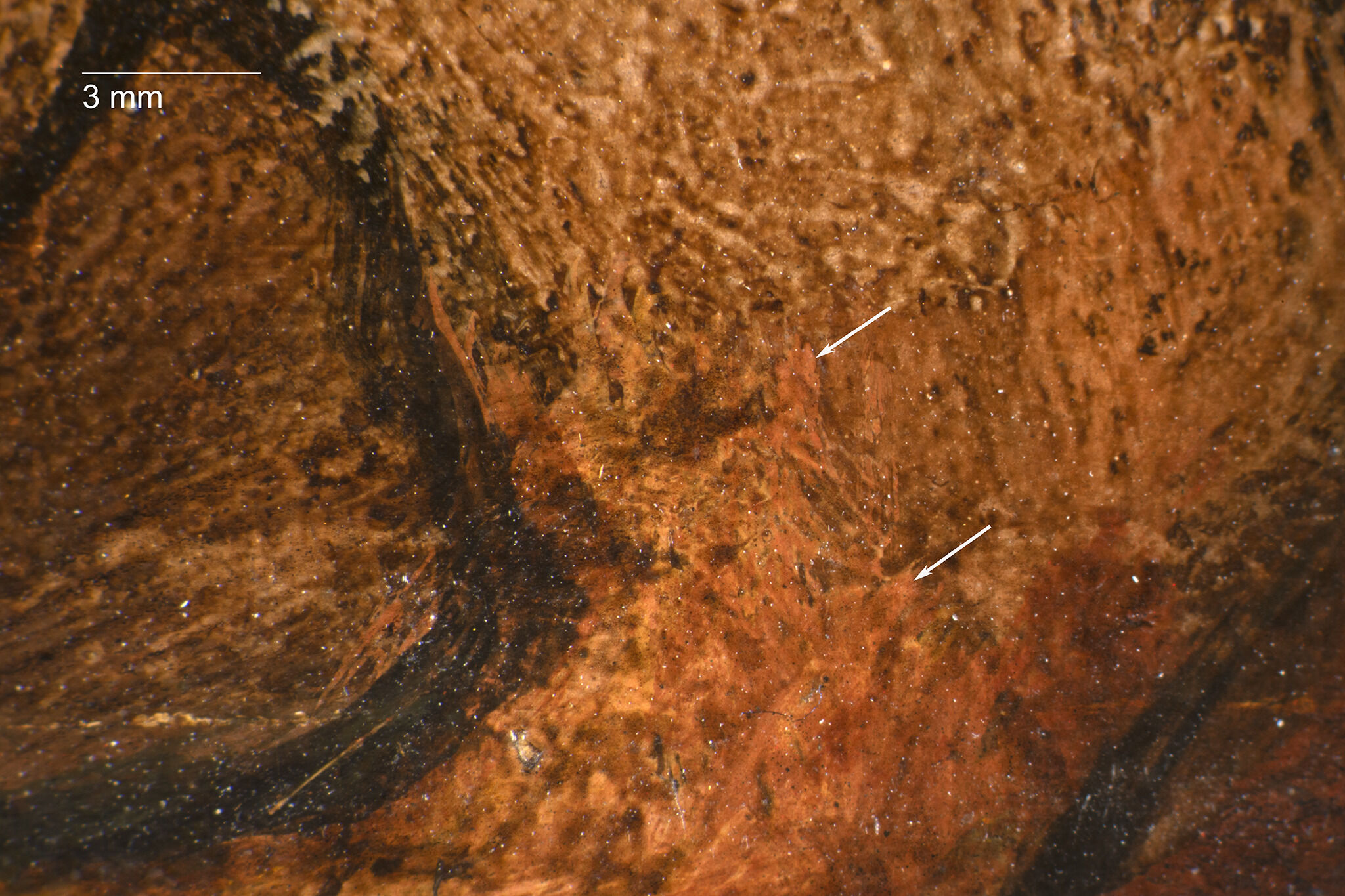

Above the lead white ground of the Nelson-Atkins panel, a sienna-colored imprimaturaimprimatura: A thin layer of paint applied over the ground layer to establish an overall tonality. was applied to establish a warm tonality overall. The imprimatura remains visible between compositional elements but also produces the reddish-brown color evident beneath the garments of the female figures and right male (Fig. 10). The infrared reflectograminfrared reflectogram: An infrared image captured with an electronic infrared imager, typically in the 1000-2500 nanometer range. See Infrared reflectography (IRR). in Figure 11 reveals a few sketch lines of unidentified medium, applied on top of the imprimatura, that loosely mark the right female’s bonnet, the bow of the central female’s bonnet (Fig. 12), a wider shape for the red scarf, and a few diagonal lines at the upper right corner.20Rik Klein Gotink, of the Bosch Research and Conservation Project, kindly captured infrared imagery of Exit from the Theater using an Osiris InGaAs camera.

Fig. 10. Detail of the right male’s jacket, Exit from the Theater (after 1863)

Fig. 10. Detail of the right male’s jacket, Exit from the Theater (after 1863)

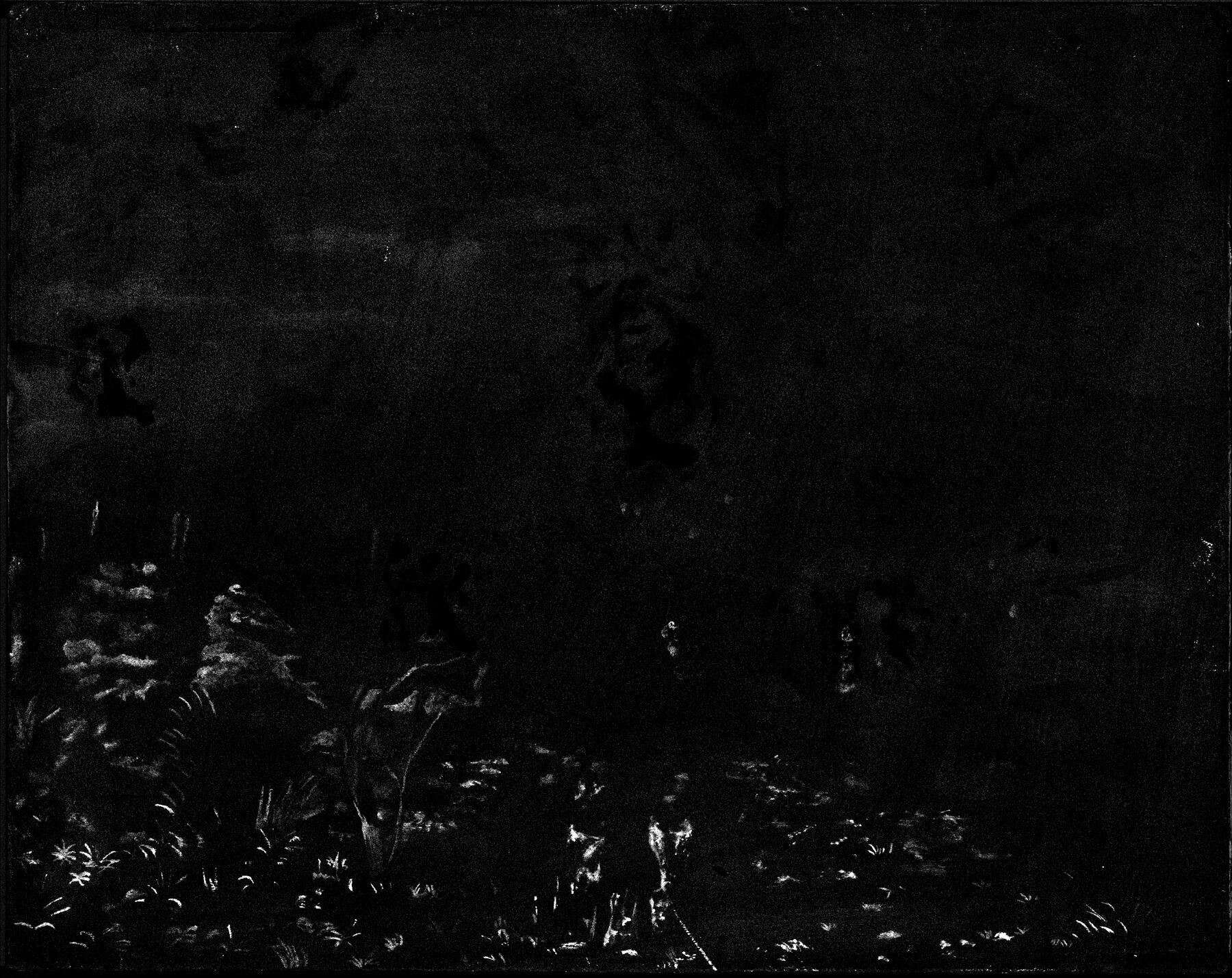

Fig. 11. Infrared reflectogram of Exit from the Theater (after 1863), captured with an OSIRIS InGaAs camera. Courtesy of Rik Klein Gotink.

Fig. 11. Infrared reflectogram of Exit from the Theater (after 1863), captured with an OSIRIS InGaAs camera. Courtesy of Rik Klein Gotink.

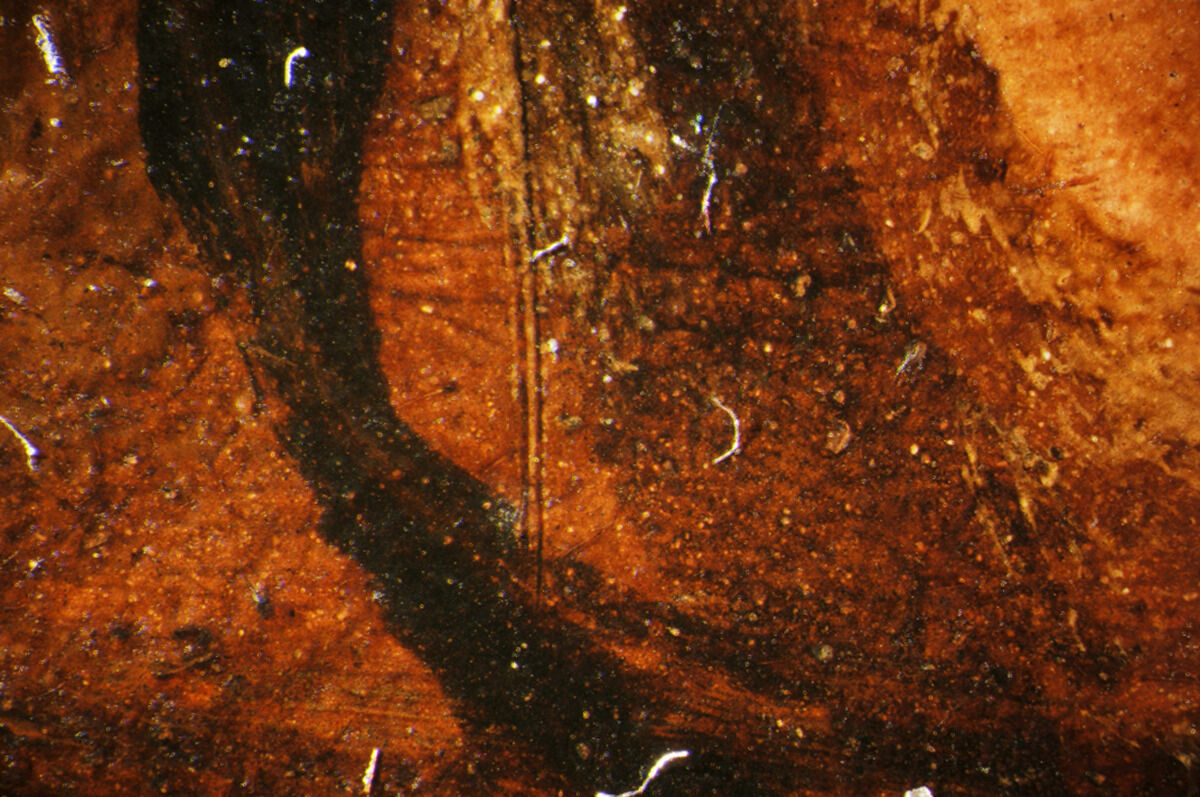

Fig. 12. Photomicrograph of black drawn line beneath the bow of the central female figure, Exit from the Theater (after 1863)

Fig. 12. Photomicrograph of black drawn line beneath the bow of the central female figure, Exit from the Theater (after 1863)

Fig. 13. Detail of two gentlemen on the left side of Exit from the Theater (after 1863), showing the painted lines used to sketch the faces

Fig. 13. Detail of two gentlemen on the left side of Exit from the Theater (after 1863), showing the painted lines used to sketch the faces

Fig. 14. Detail of the lower left male, Exit from the Theater (after 1863)

Fig. 14. Detail of the lower left male, Exit from the Theater (after 1863)

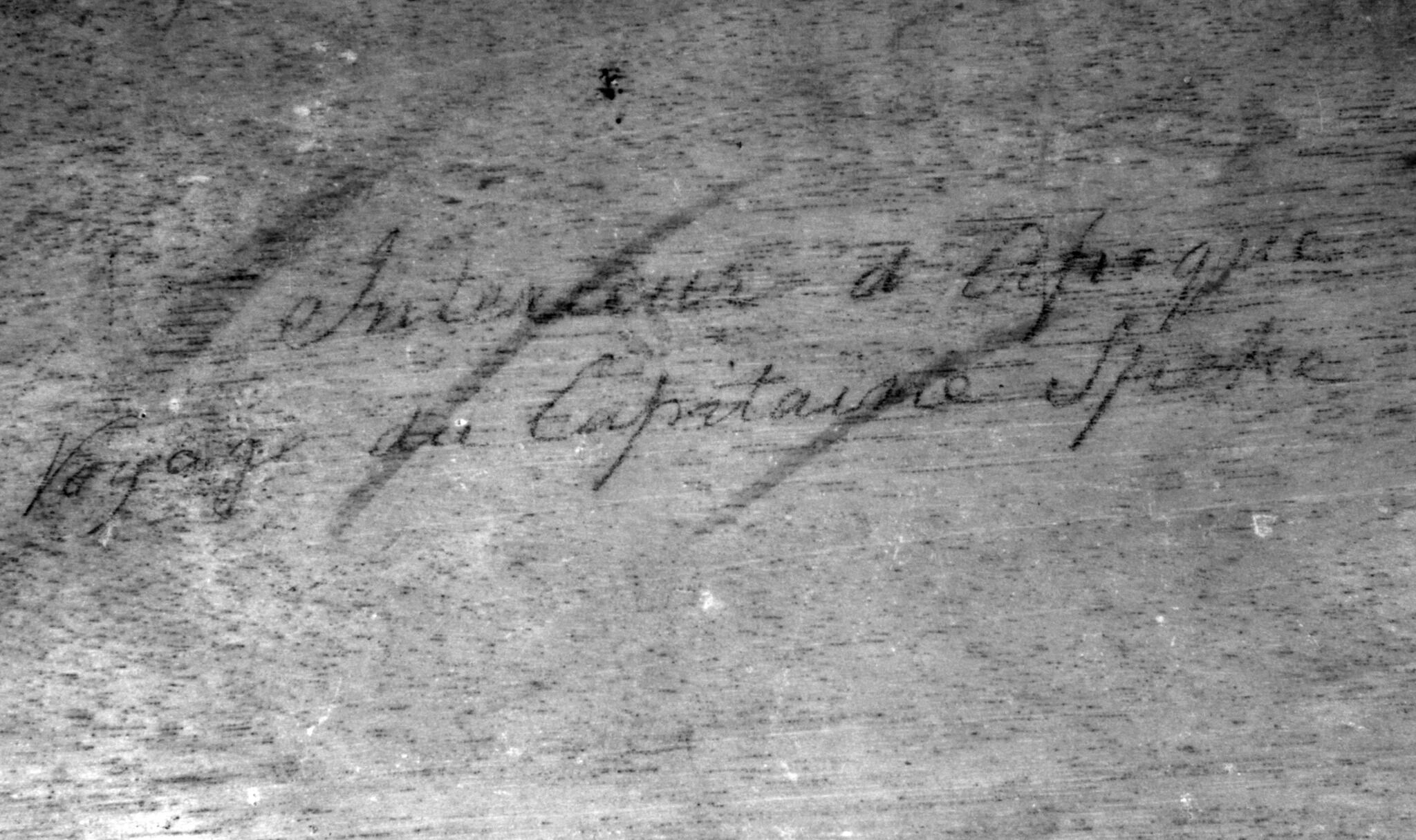

Fig. 15. Photomicrograph of the playbill, Exit from the Theater (after 1863), 12.5x

Fig. 15. Photomicrograph of the playbill, Exit from the Theater (after 1863), 12.5x

A discolored and unsaturated natural resin varnish has shifted the

colors and darkened the theater scene. The varnish produces an opaque

yellow-green UV-induced visible fluorescenceultraviolet (UV) fluorescence or UV-induced visible fluorescence: The reflected visible light produced when painting materials interact with ultraviolet (UV) radiation. Not all materials fluoresce, but the color and intensity of the fluorescence is frequently used to differentiate between original and restoration materials, characterize the varnish layers, or reveal the distribution of pigments across the composition. that may conceal the

presence of non-original paint beneath the surface coating (Fig. 16). A

small amount of retouchingretouching: Paint application by a conservator or restorer to cover losses and unify the original composition. Retouching is an aspect of conservation treatment that is aesthetic in nature and that differs from more limited procedures undertaken solely to stabilize original material. Sometimes referred to as inpainting or retouch. was added to the rightmost figure’s face

where a split in the panel, approximately 3 centimeters long, was

stabilized with a wooden inset on the panel reverse. Paint along the

lower left and bottom edges, near to, and including the right male’s

fingers, may contain later additions of paint, as these areas have a

different color and texture when compared to the surrounding original

paint (Fig. 17).

Fig. 16. Ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescence photograph, Exit from the Theater (after 1863)

Fig. 16. Ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescence photograph, Exit from the Theater (after 1863)

Fig. 17. Photomicrograph of Exit from the Theater (after 1863), showing orange retouching along the bottom edge and right male’s fingers

Fig. 17. Photomicrograph of Exit from the Theater (after 1863), showing orange retouching along the bottom edge and right male’s fingers

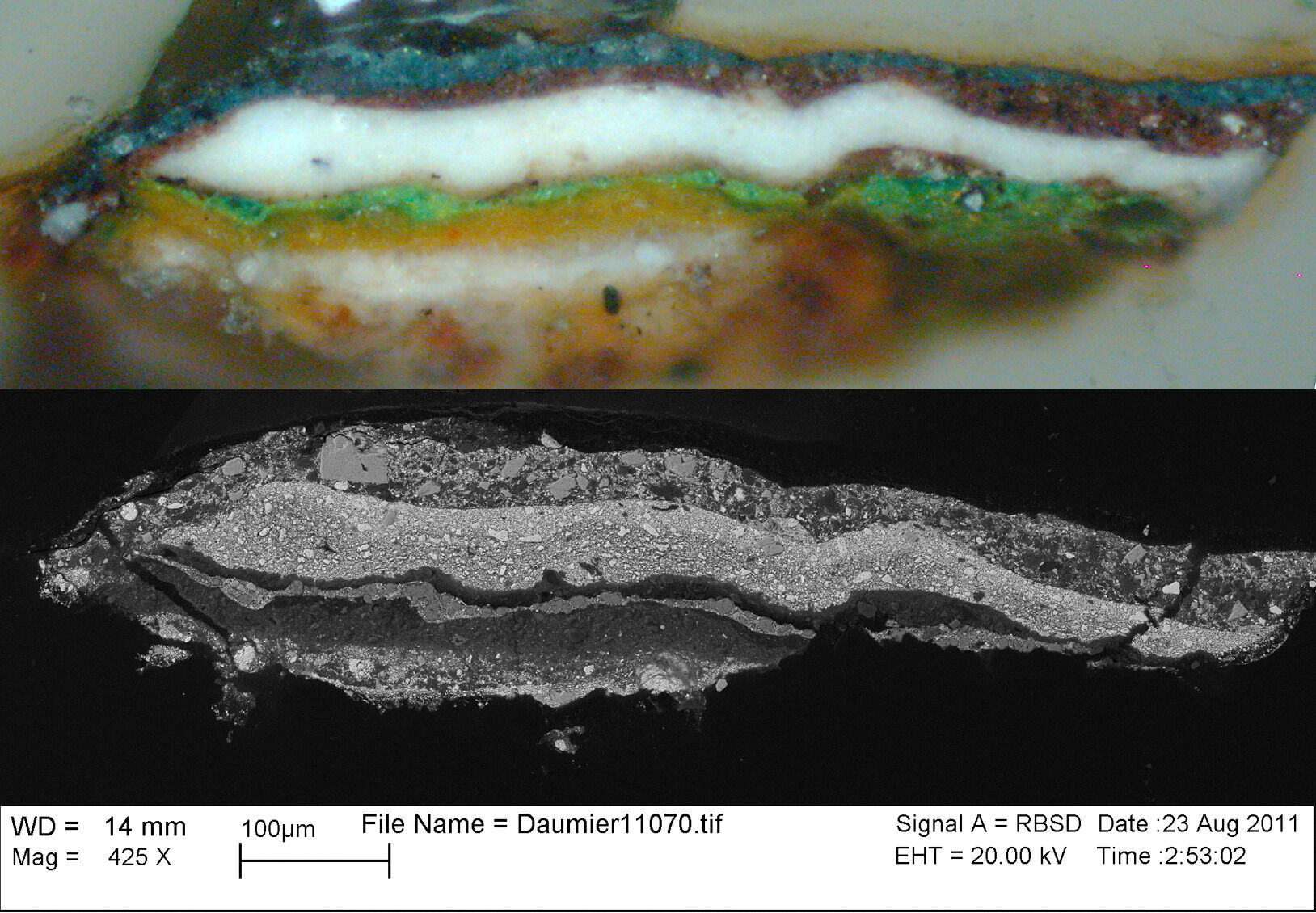

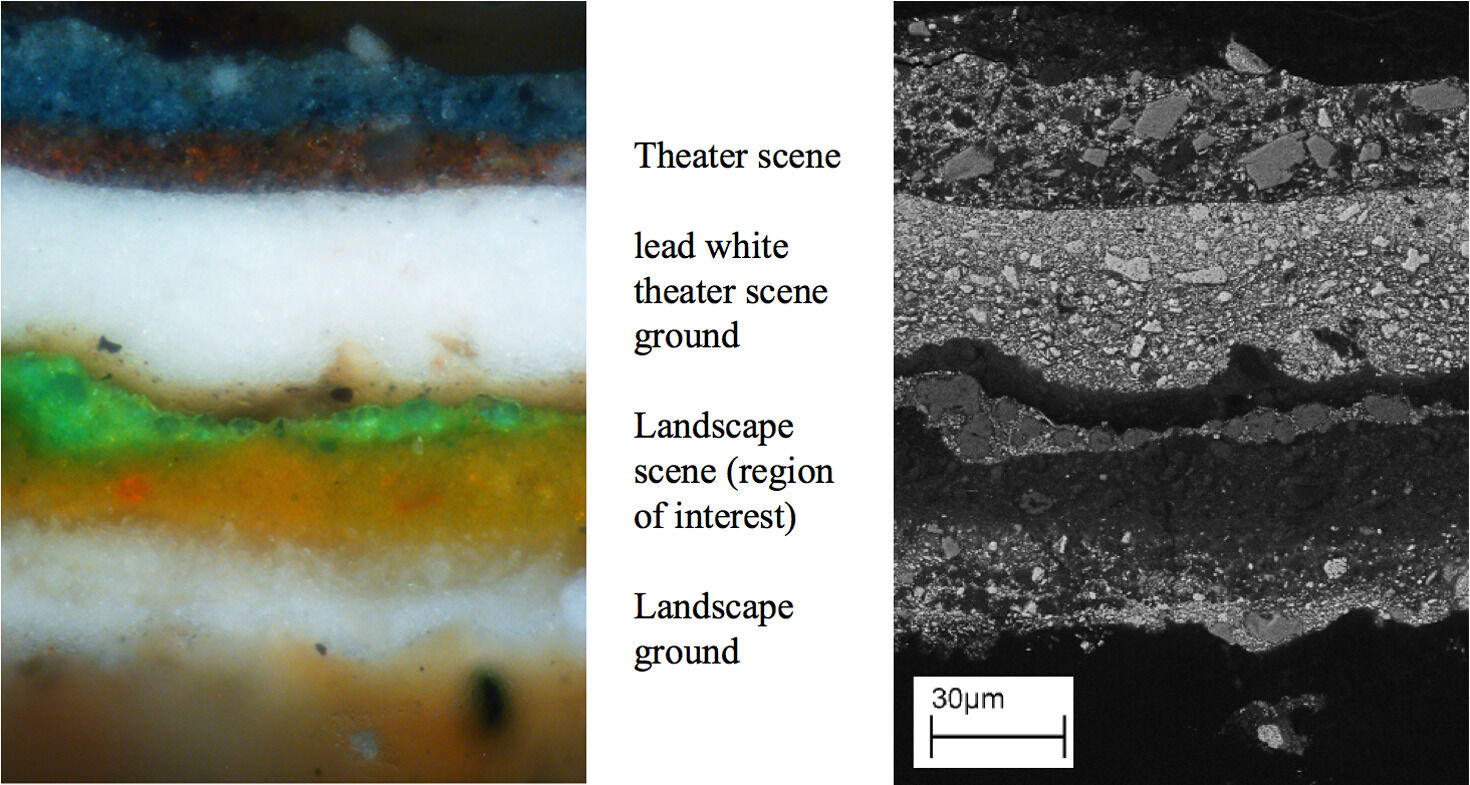

Considering the number of Daumier forgeries and the questions surrounding the Nelson-Atkins painting, it was essential to confirm that the materials used were entirely among those available to Daumier. The reused panel provided yet another level of materials scrutiny since the pigments of the underlying landscape must also have been in use prior to Daumier’s execution of Exit from the Theater if, indeed, he was the artist. While the stippled ground texture connects the Nelson-Atkins painting more securely to authentic works by Daumier, this thick application of lead white was the main impediment to study of the underlying landscape, obscuring details that would otherwise be visible through radiography and infrared reflectography.

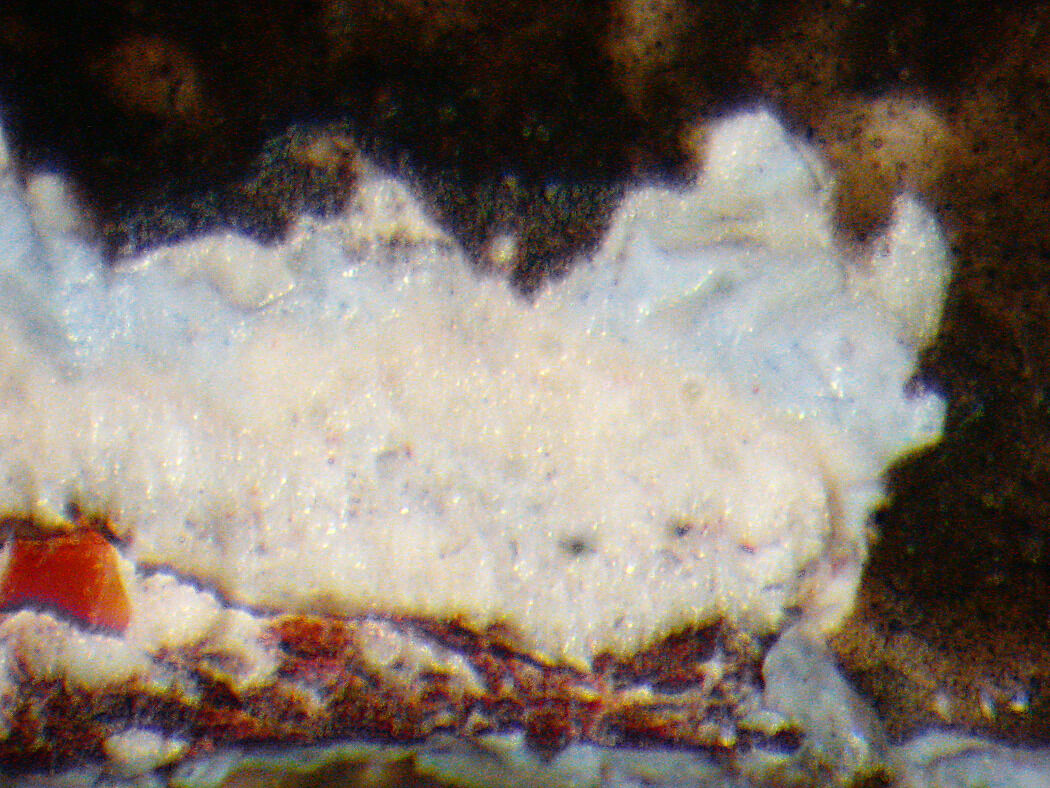

Fig. 19. Paint cross section details of Exit from the Theater (after 1863) in visible and backscatter electron images with the various strata labeled. Scale bar = 0.03mm.

Fig. 19. Paint cross section details of Exit from the Theater (after 1863) in visible and backscatter electron images with the various strata labeled. Scale bar = 0.03mm.

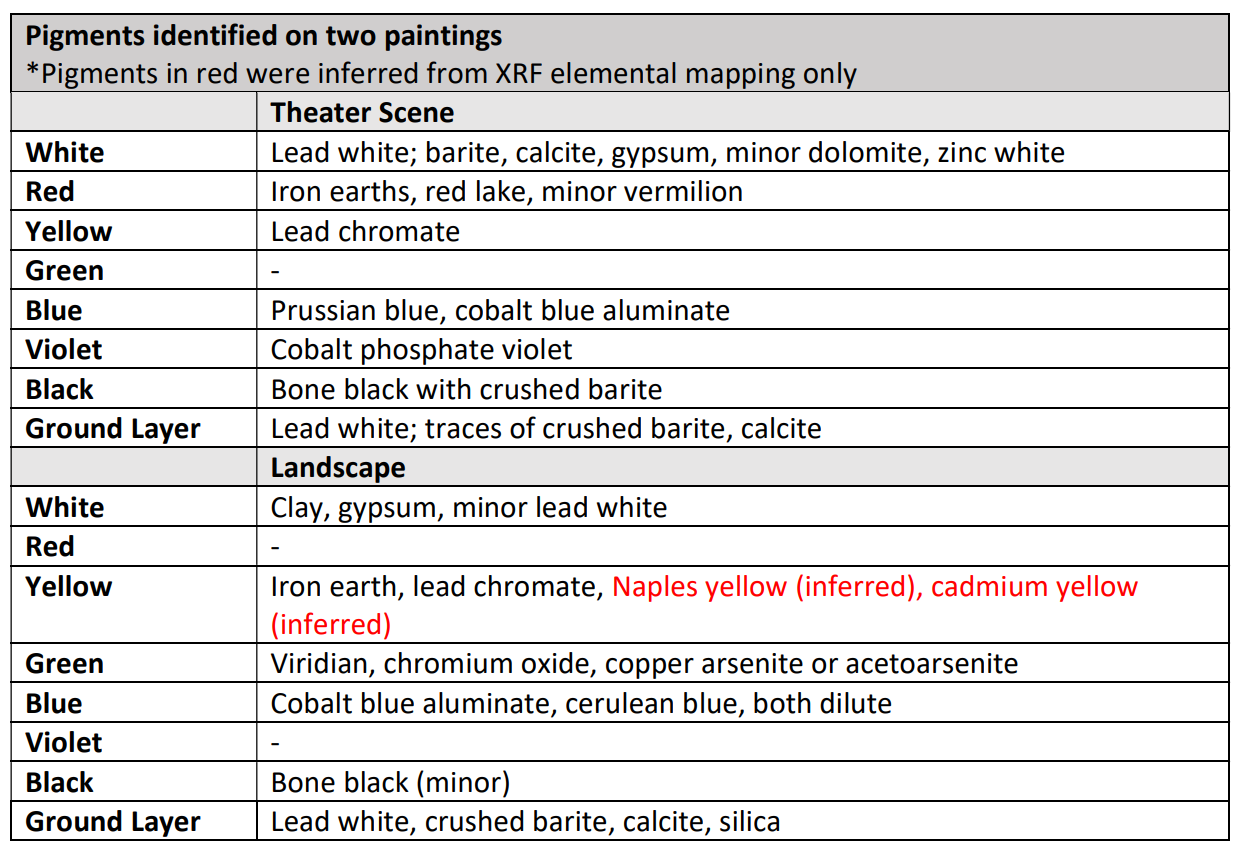

Table 1. List of pigments identified on Exit from the Theater (after 1863) and the underlying landscape

Table 1. List of pigments identified on Exit from the Theater (after 1863) and the underlying landscape

Fig. 20. Photomicrograph of Exit from the Theater (after 1863), showing sky blue paint from the underlying landscape and its ground layer exposed at an edge loss, field of view is approximately 0.5mm

Fig. 20. Photomicrograph of Exit from the Theater (after 1863), showing sky blue paint from the underlying landscape and its ground layer exposed at an edge loss, field of view is approximately 0.5mm

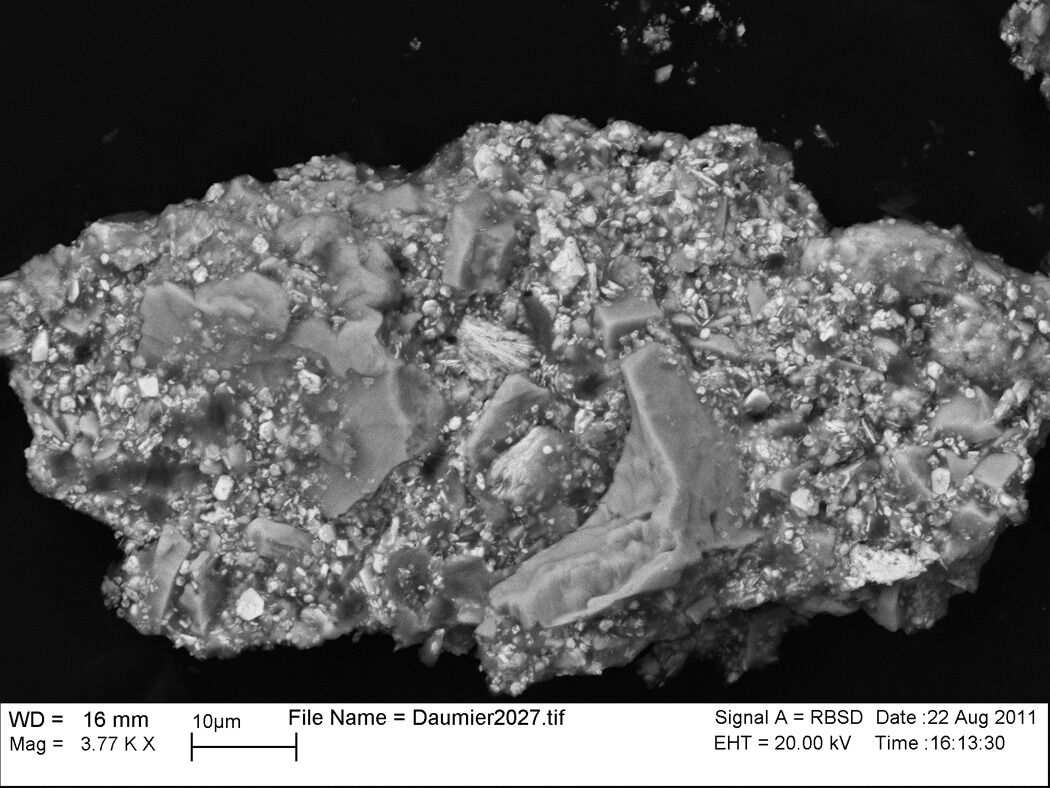

Fig. 21. Jagged particles of coarse natural barite make up most of this sample of flesh color from the mouth of the largest male figure, Exit from the Theater (after 1863). Size and shape differentiate them from synthetic barium sulfate which was also in common use. Smaller particles of lead white and chrome yellow surround the barite. Backscatter electron image, scale bar = 0.01mm.

Fig. 21. Jagged particles of coarse natural barite make up most of this sample of flesh color from the mouth of the largest male figure, Exit from the Theater (after 1863). Size and shape differentiate them from synthetic barium sulfate which was also in common use. Smaller particles of lead white and chrome yellow surround the barite. Backscatter electron image, scale bar = 0.01mm.

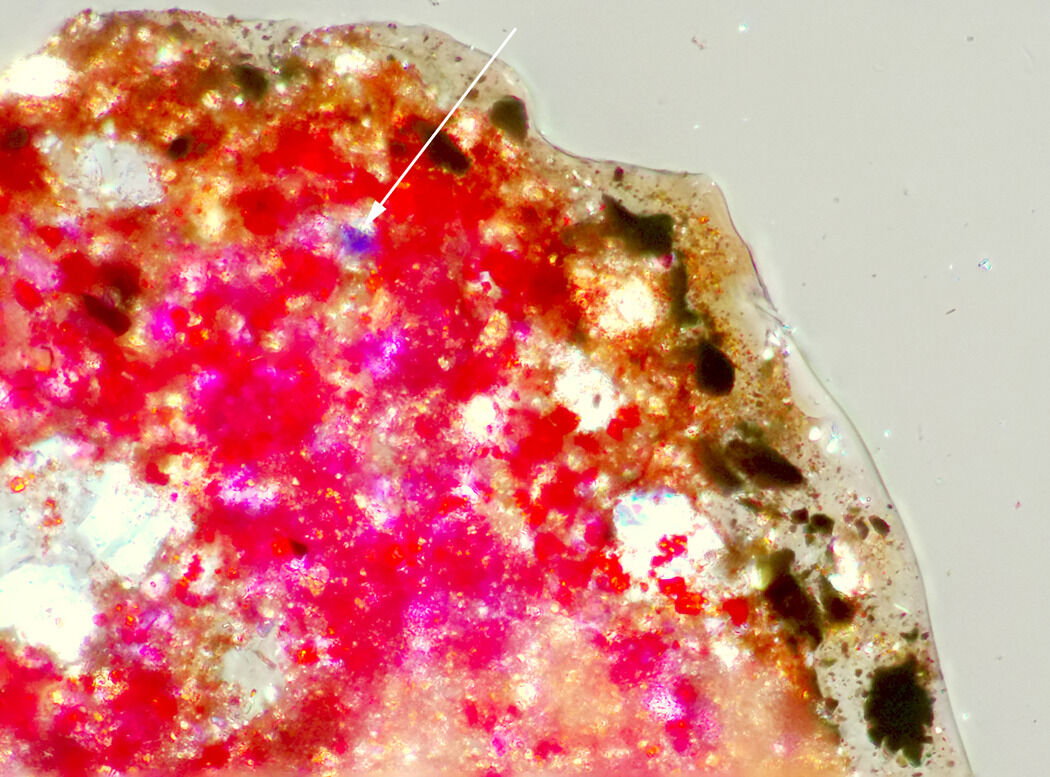

Fig. 22. Red pigments that make up the shadows in the faces of Exit from the Theater (after 1863), including cobalt phosphate violet beneath a semitransparent layer of bone black and iron earth. A single particle of cobalt blue is present at the arrow. Transmitted light with crossed polars, 200x.

Fig. 22. Red pigments that make up the shadows in the faces of Exit from the Theater (after 1863), including cobalt phosphate violet beneath a semitransparent layer of bone black and iron earth. A single particle of cobalt blue is present at the arrow. Transmitted light with crossed polars, 200x.

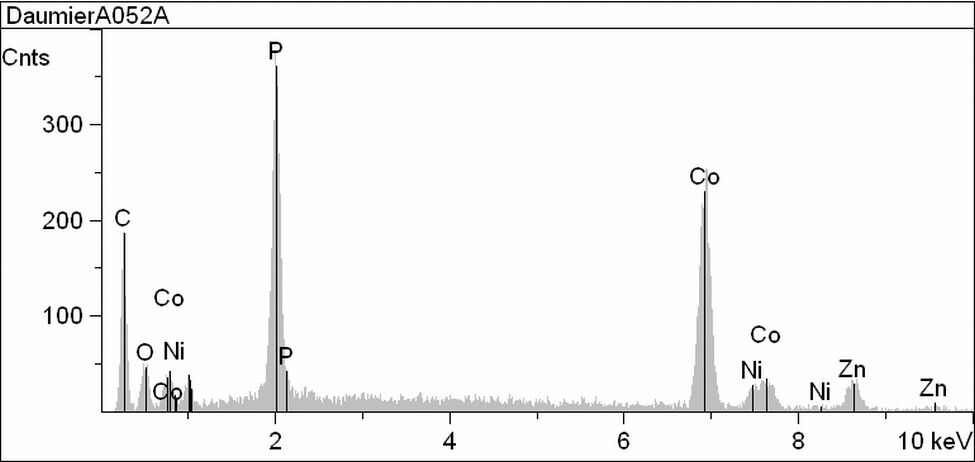

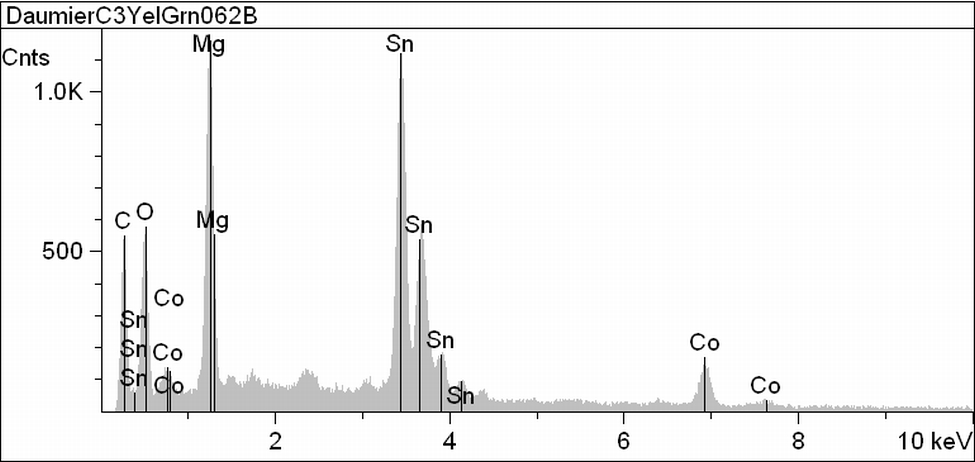

Fig. 23. X-ray spectrum from an individual particle of cobalt violet probed in the SEM showing a small amount of nickel (Ni) detectable along with the elements phosphorus (P), cobalt (Co), and oxygen (O), Exit from the Theater (after 1863)

Fig. 23. X-ray spectrum from an individual particle of cobalt violet probed in the SEM showing a small amount of nickel (Ni) detectable along with the elements phosphorus (P), cobalt (Co), and oxygen (O), Exit from the Theater (after 1863)

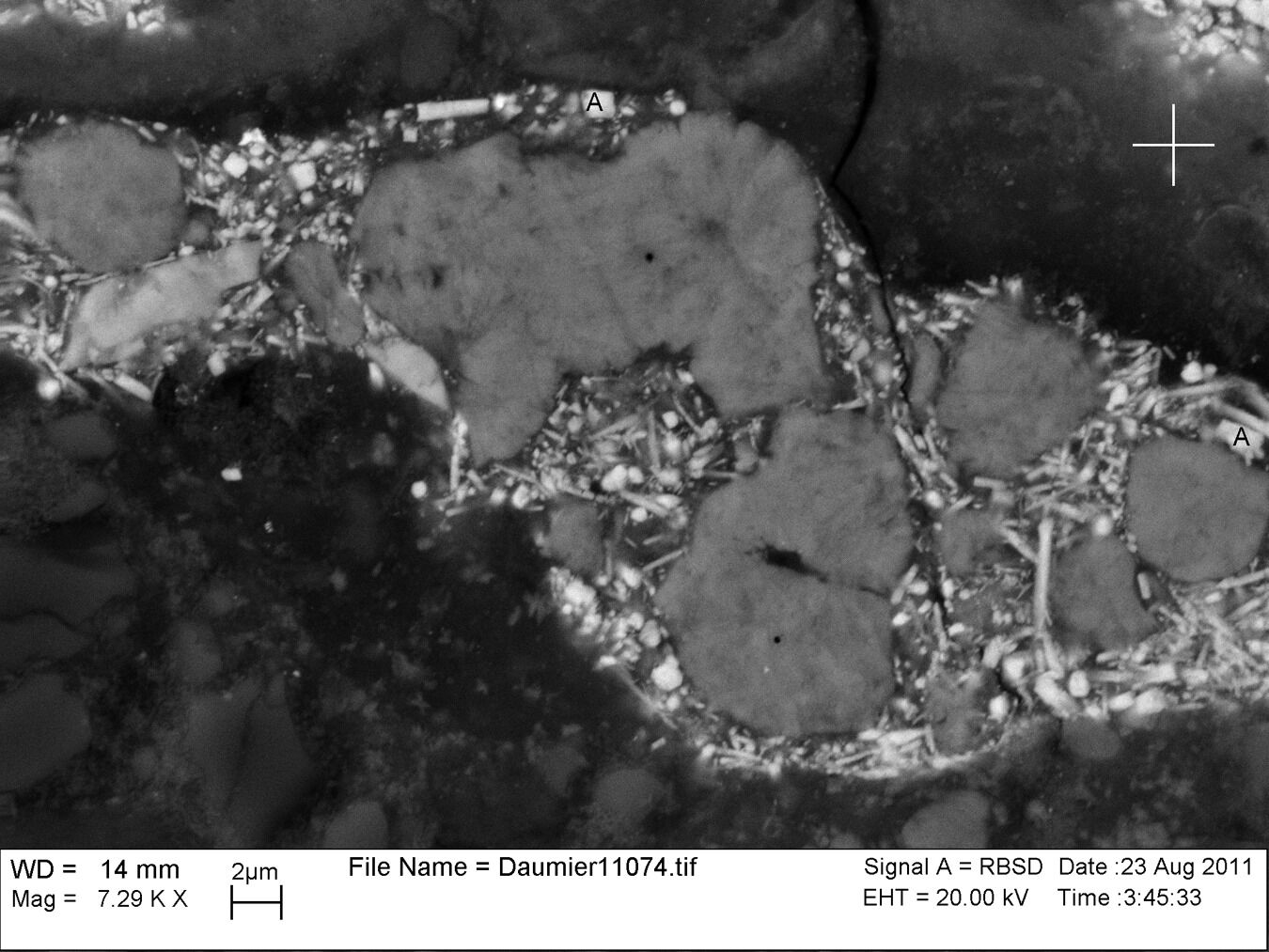

Fig. 24. Cross section detail of Exit from the Theater (after 1863), showing the landscape green layer in Figure 18 with coarse, rounded grains of copper arsenite green surrounded by brighter needles of lead chromate yellow, backscatter electron image, scale bar = 0.002mm

Fig. 24. Cross section detail of Exit from the Theater (after 1863), showing the landscape green layer in Figure 18 with coarse, rounded grains of copper arsenite green surrounded by brighter needles of lead chromate yellow, backscatter electron image, scale bar = 0.002mm

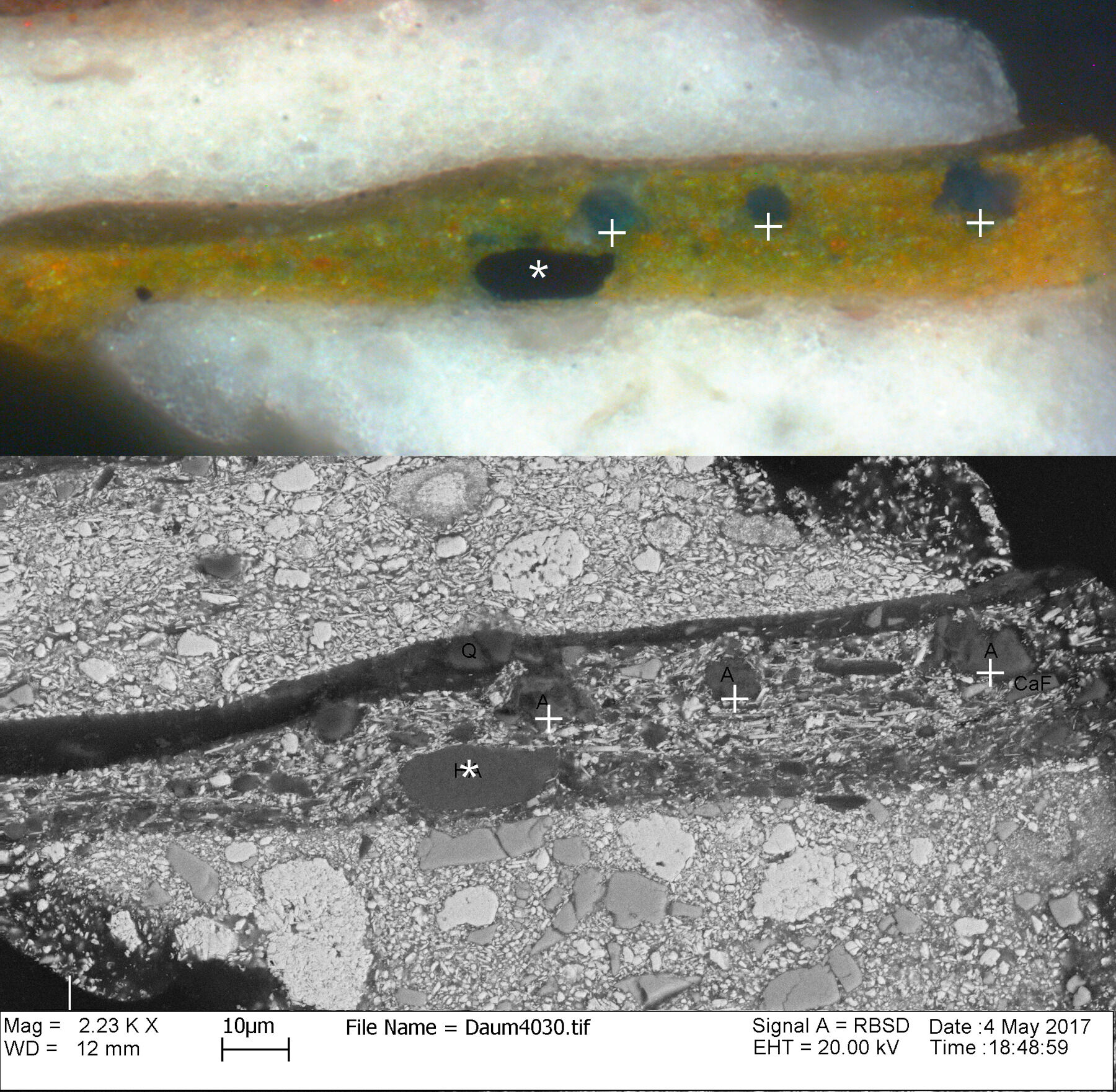

Fig. 25. Cross section detail of Exit from the Theater (after 1863), showing a second landscape yellow-green sample; (top) visible light microscope image and (bottom) backscatter electron image, showing sparse grains of cobalt blue “+” and a single example of bone black “*”, scale bar = 0.010mm

Fig. 25. Cross section detail of Exit from the Theater (after 1863), showing a second landscape yellow-green sample; (top) visible light microscope image and (bottom) backscatter electron image, showing sparse grains of cobalt blue “+” and a single example of bone black “*”, scale bar = 0.010mm

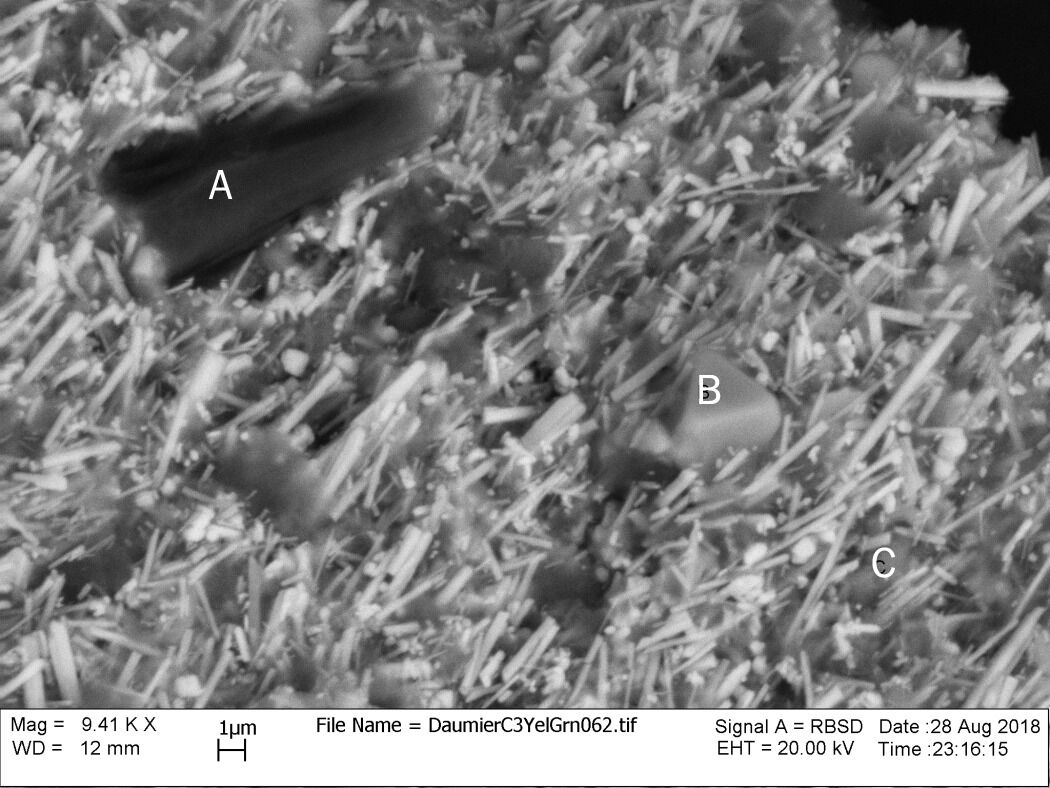

Fig. 26. Microsample beneath the chin of the man on the left corresponding with a tin response from the hills in the mid distance, backscatter electron image, Exit from the Theater (after 1863). Cerulean blue in the form of a blocky hexagon (B), a stray particle of charcoal (A), and an iron earth particle (C) are surrounded by needles of chrome yellow. Scale bar = 0.001mm.

Fig. 26. Microsample beneath the chin of the man on the left corresponding with a tin response from the hills in the mid distance, backscatter electron image, Exit from the Theater (after 1863). Cerulean blue in the form of a blocky hexagon (B), a stray particle of charcoal (A), and an iron earth particle (C) are surrounded by needles of chrome yellow. Scale bar = 0.001mm.

Fig. 27. X-ray spectrum from the cerulean blue particle in Figure 21 probed in the SEM showing a high level of magnesium (Mg) along with the required elements tin (Sn), cobalt (Co), and oxygen (O), Exit from the Theater (after 1863)

Fig. 27. X-ray spectrum from the cerulean blue particle in Figure 21 probed in the SEM showing a high level of magnesium (Mg) along with the required elements tin (Sn), cobalt (Co), and oxygen (O), Exit from the Theater (after 1863)

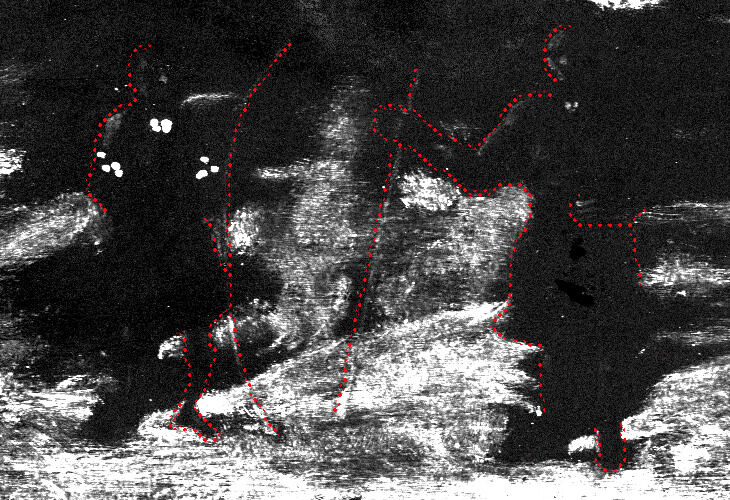

Fig. 28. X-ray fluorescence elemental map for arsenic acquired at 12.9 keV primarily showing green foliage of the underlying landscape depicted with copper arsenite green, Exit from the Theater (after 1863)

Fig. 28. X-ray fluorescence elemental map for arsenic acquired at 12.9 keV primarily showing green foliage of the underlying landscape depicted with copper arsenite green, Exit from the Theater (after 1863)

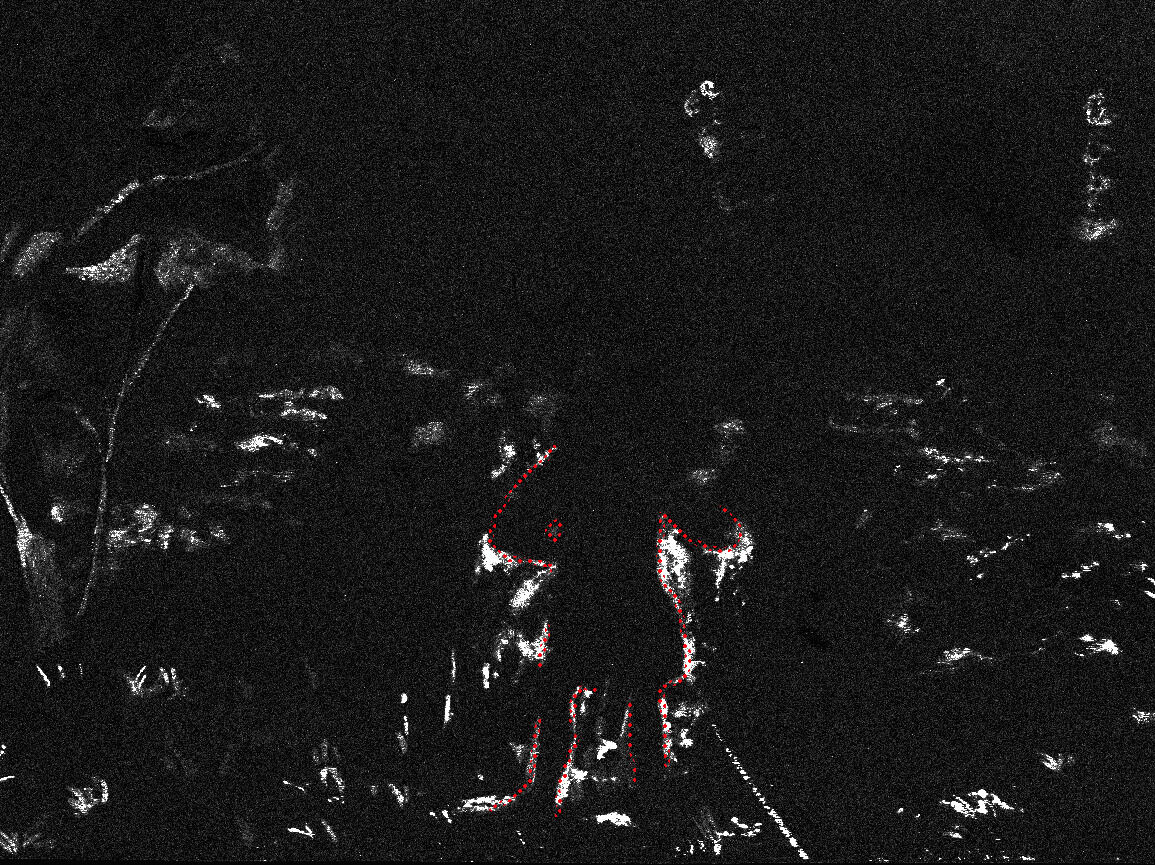

Fig. 29. Annotated detail from the center foreground of the arsenic K map acquired at 12.9 keV in Figure 28 showing figures in silhouette surrounded by arsenic in the foliage green, Exit from the Theater (after 1863)

Fig. 29. Annotated detail from the center foreground of the arsenic K map acquired at 12.9 keV in Figure 28 showing figures in silhouette surrounded by arsenic in the foliage green, Exit from the Theater (after 1863)

Fig. 32. Annotated detail from the center foreground of the cadmium map in Figure 31 showing a third figure in silhouette located between the two figures in Figure 29, Exit from the Theater (after 1863)

Fig. 32. Annotated detail from the center foreground of the cadmium map in Figure 31 showing a third figure in silhouette located between the two figures in Figure 29, Exit from the Theater (after 1863)

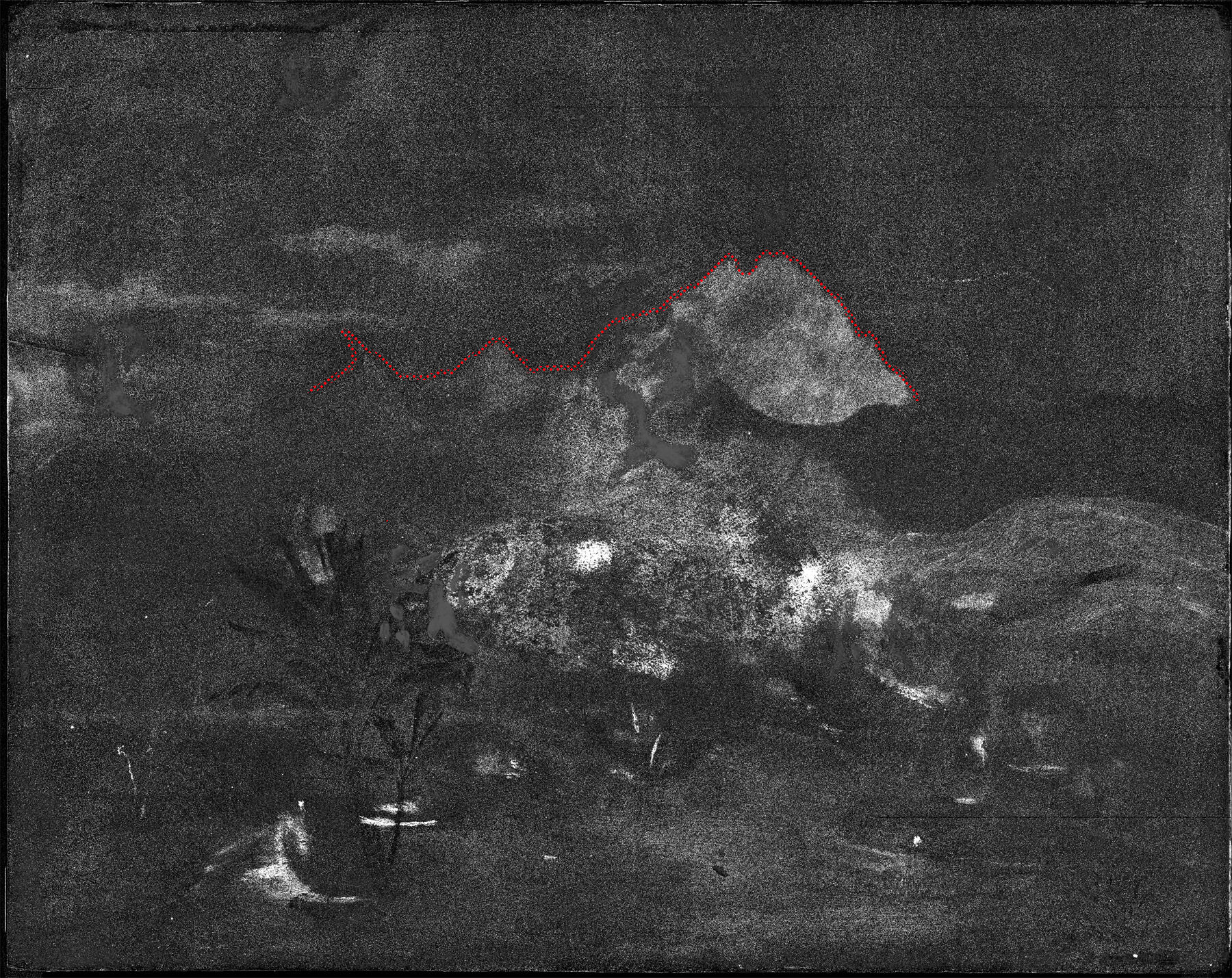

Fig. 33. X-ray fluorescence elemental map for the antimony K-line acquired at 36.5 keV, minus an overlapping contribution from barium, showing an intermediate range of mountains, Exit from the Theater (after 1863)

Fig. 33. X-ray fluorescence elemental map for the antimony K-line acquired at 36.5 keV, minus an overlapping contribution from barium, showing an intermediate range of mountains, Exit from the Theater (after 1863)

Fig. 34. X-ray fluorescence elemental map for the barium K-line acquired at 36.5 keV showing a range of foothills along with highlights from the overlying theater composition thought to be rich in calcium. The energetic barium K response from small amounts present in the calcium serves as a surrogate for calcium whose less energetic X-rays are absorbed by the overlying paint. Exit from the Theater (after 1863).

Fig. 34. X-ray fluorescence elemental map for the barium K-line acquired at 36.5 keV showing a range of foothills along with highlights from the overlying theater composition thought to be rich in calcium. The energetic barium K response from small amounts present in the calcium serves as a surrogate for calcium whose less energetic X-rays are absorbed by the overlying paint. Exit from the Theater (after 1863).

A third mountain range, to the immediate foreground of that indicated by antimony, was confirmed by both the strontium and barium maps (Fig. 34).

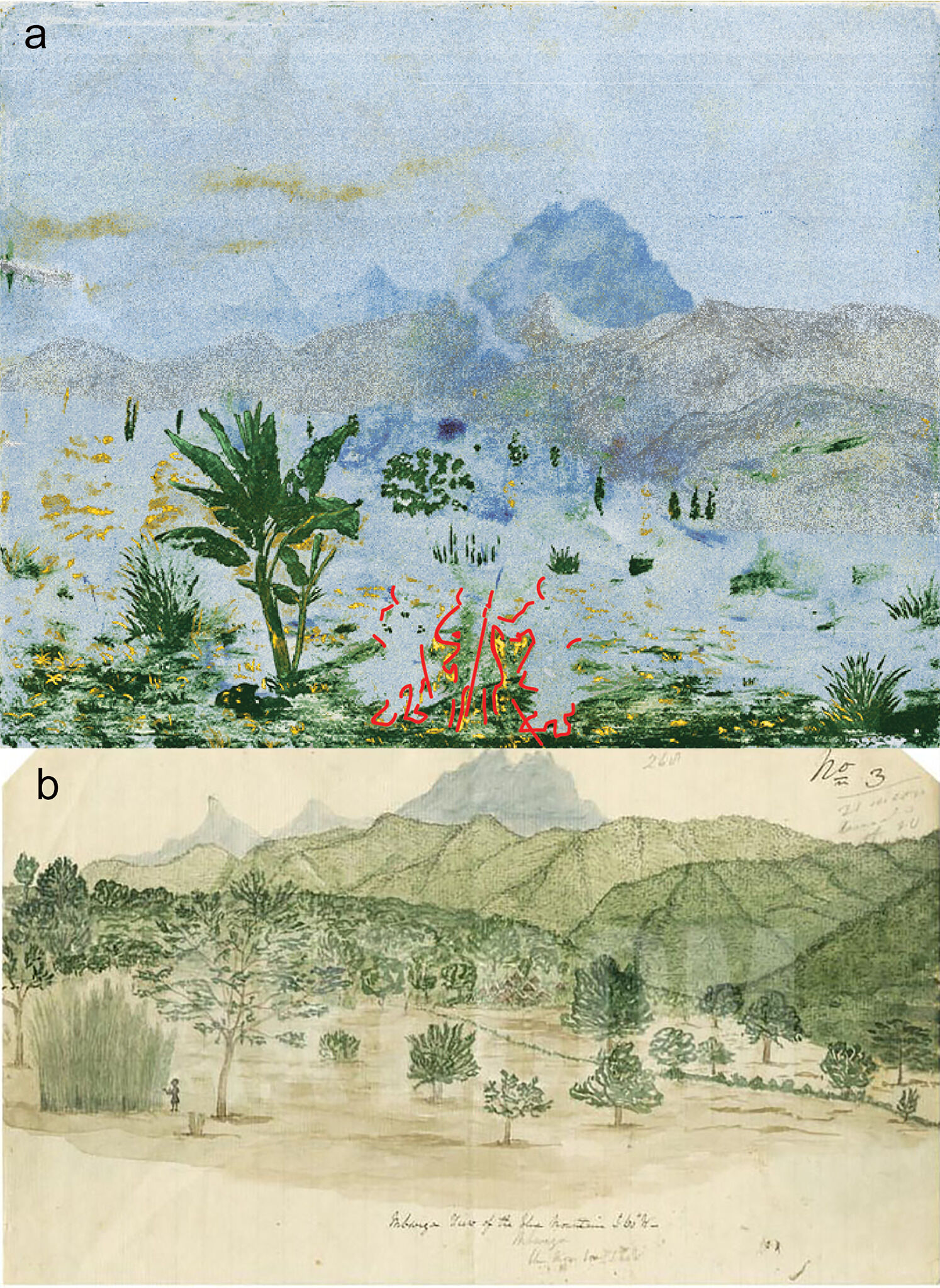

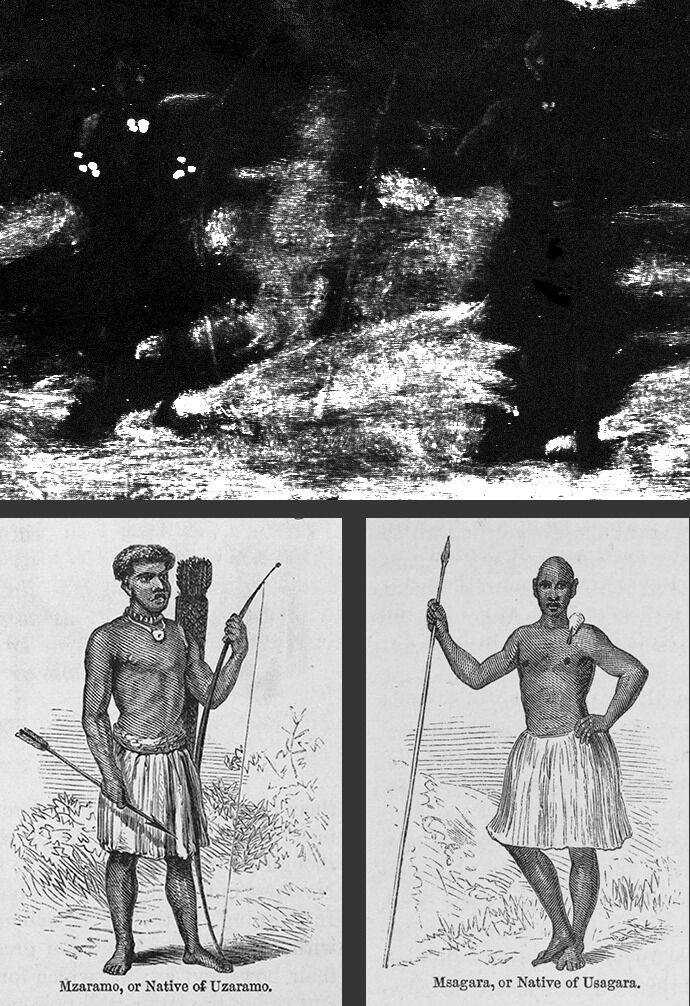

Figs. 36a–b. 36a. Overlaid elemental maps of Exit from the Theater (after 1863), revealing an image of the underlying landscape. Courtesy of Louisa Smieska; 36b. John Hanning Speke, Mbwiga, View of the Blue Mountains S 60’W, 1858, watercolor, Royal Geographical Society, S0016604

Figs. 36a–b. 36a. Overlaid elemental maps of Exit from the Theater (after 1863), revealing an image of the underlying landscape. Courtesy of Louisa Smieska; 36b. John Hanning Speke, Mbwiga, View of the Blue Mountains S 60’W, 1858, watercolor, Royal Geographical Society, S0016604

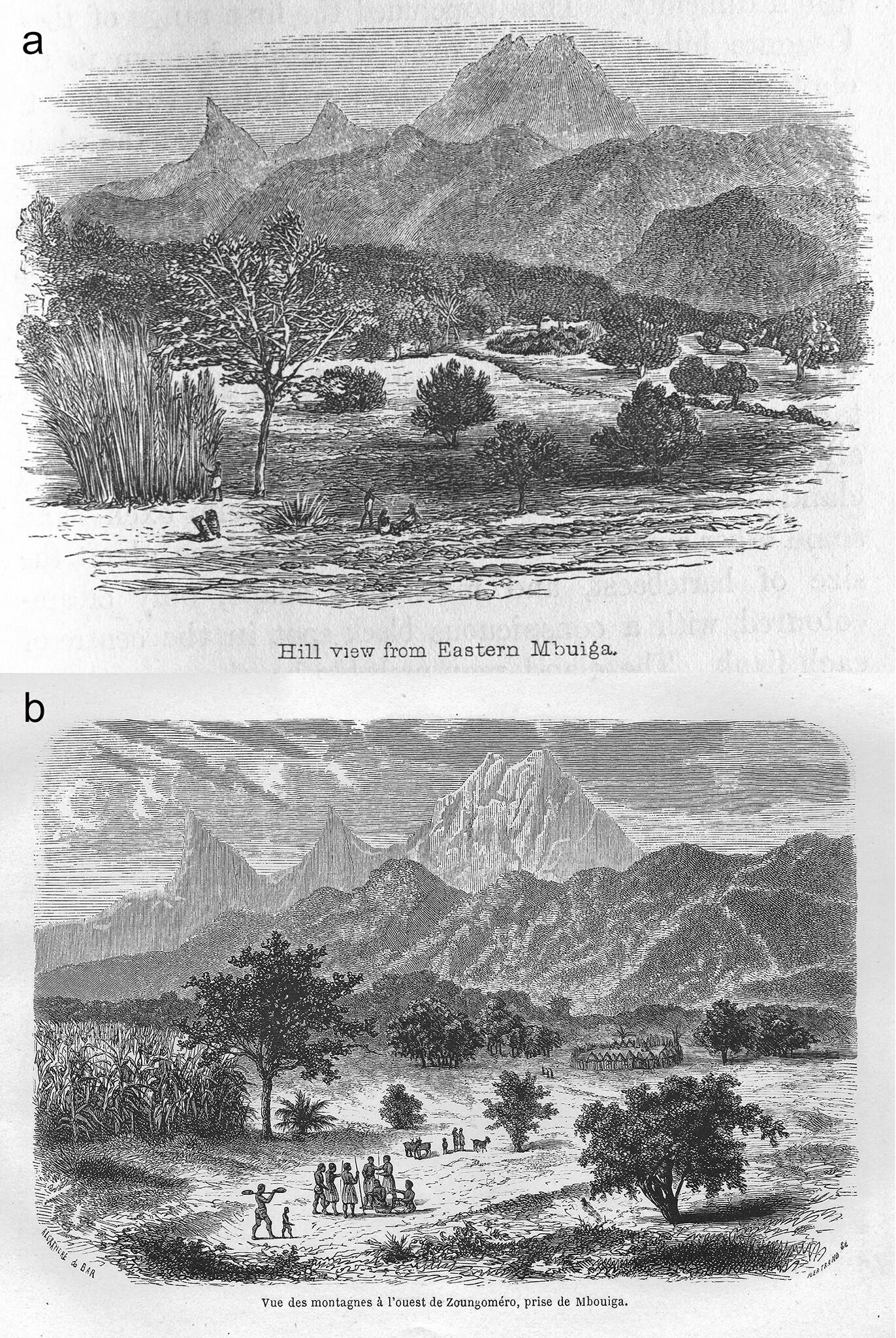

Figs. 37a–b. 37a. Hill View from Eastern Mbûiga, engraving from Speke, Journal of the Discovery of the Source of the Nile (Edinburgh and London: Blackwood, 1863), 45; 37b. Vue des montagnes á l’ouest de Zoungoméro, prise de Mbouiga, engraving from Speke, Journal of the Discovery of the Source of the Nile (Paris: Hachette, 1864), 59

Figs. 37a–b. 37a. Hill View from Eastern Mbûiga, engraving from Speke, Journal of the Discovery of the Source of the Nile (Edinburgh and London: Blackwood, 1863), 45; 37b. Vue des montagnes á l’ouest de Zoungoméro, prise de Mbouiga, engraving from Speke, Journal of the Discovery of the Source of the Nile (Paris: Hachette, 1864), 59

Another possibility is that the landscape painting, a composite of expedition imagery, was associated with the illustrative process of the French edition of Speke’s 1863 travel account, published in Paris with numerous reworked engravings just one year later (Fig. 37b).36John Hanning Speke, Journal of the Discovery of the Source of the Nile (Hachette: Paris, 1864). The development of printed imagery for books in the late nineteenth century is described as a complicated, multistage process in which publishers, artists, engravers, lithographers, and printers influenced the final image, and “visual elements were invariably borrowed and reused in new contexts in order to visualize places and cultures previously unfamiliar.”37Leila Koivunen, Visualizing Africa in Nineteenth-Century British Travel Accounts (New York: Routledge, 2009), 7, 109. In this scenario several connections can be drawn between Daumier, who was first and foremost a printmaker, and the engravers and book illustrators working on the publication. François Auguste Trichon (1814–98), an engraver whose name is featured below several of the illustrations in the French publication, was one of more than 60 different engravers working on the printed production of Daumier’s works from 1833 to 1878.38Eugene Bouvy, Daumier: L’Oeuvre gravé du maître (Paris: Le Garrec, 1933), 1:11. Daumier’s friendship with Gustave Doré (1832–83) provides yet another link to Speke’s publication, as Trichon and six other artists associated with the 1864 engravings also collaborated with Doré on book illustrations.39These artists include Adolphe François Pannemaker (1822–1900), Antoine Valérie Bertrand (b. 1823), J. Gauchard Brunier (n.d.), Alexandre de Bar (1821-1901), Charles LaPlante (1837–1903), and Jules Jean Marie Joseph Huyot (1841–1921). Charles Maurand, the artist responsible for the wood engraving associated with Exit from the Theater (Fig. 1), also worked on Doré illustrations.

At its conclusion, the technical study made new discoveries in relation to the painting’s technique, materials, and execution date. The combination of palette studies and MA-XRF verified that all of the pigments—those present in the first and second compositions—are among those commonly encountered in later nineteenth-century European paintings. No anachronistic materials were uncovered that would definitively expose the Nelson-Atkins painting as a forgery. Despite similarities between the two palettes, there are clear differences that distinguished all components of the two paintings, making it unlikely that they were produced by the same individual working from a single stock of materials.

Many pigments of the underlying landscape are shared with the theater scene. One that is not, cerulean blue, deserves special attention. Not only was it a key means of recognizing the underlying scene through mapping of its tin content, but it is also a pigment better known in this period for use in watercolor. Because the travel sketches that inspired the landscape were executed in watercolor, use of cerulean blue to maintain constancy in the transfer to oil medium makes more sense than it might for a scene whose original execution was in oil and unrelated to preparatory watercolors. The commercial history of cerulean blue is not well-documented but it was available as a watercolor pigment long before being commercialized for oils and, thus, available to artists as a pigment.40The commercial introduction of cerulean blue is generally credited to Rowney in the year 1860 for use as a watercolor pigment, with its introduction for oil coming only in 1870. These dates could be seen as discrediting the attribution of the theater scene to Daumier since the pigment occurs in oil in the underlying landscape that must have preceded it in date. However, the material itself was known as early as 1805 and has been reported to have been sold earlier in Germany in the 1800s. (Winsor Newton, http://www.winsornewton.com/na/articles/colours/spotlight-on-cerulean-blue/, accessed November 9, 2020)

The parallels in technique between Exit from the Theater and authentic works by Daumier are significant, particularly the distinguishing texture of the ground layer. The presence of a similar ground texture in the radiographs of two unquestioned paintings, one of which is a theater scene, provides the strongest correlation between Daumier and the Nelson-Atkins painting to date. The stippled ground texture is subtle and a feature of the artist’s preparatory process that is not easily observed on the paint surface for replication by a forger. Connections between Daumier and engravers affiliated with the French edition of Speke’s publication offer possible avenues by which Daumier may have obtained and repurposed the wooden panel. The underlying landscape, originally painted as a watercolor in 1858 and first published in modified form in 1863, provides the earliest possible date by which Exit from the Theater could have been completed. It is this latter date that fits within the time period in which Daumier was producing oil paintings that focused on the subject of the theater.41Bruce Laughton, Honoré Daumier (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996), 60.

Notes

-

See accompanying catalogue entry by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan for an overview of the painting’s provenance and early questions regarding its authenticity.

-

Karl Eric Maison, Honoré Daumier, Catalogue Raisonné of the Paintings, Watercolors, and Drawings. (London: Thames and Hudson, 1968), 1:37. See also Douglas Campbell and Usher Caplan, eds., Daumier 1808–1879 (Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada, 1999), 30.

-

Campbell and Caplan, eds. Daumier 1808–1879, 27.

-

Edmond Duranty, “Études sur Daumier,” Gazette des beaux-arts 17, 2nd ser., no. 6 (June 1878): 539 and N[oéme] C[adiot], “L’Exposition de Daumier,” Courrier du soir (May 24, 1878): 2, respectively, as cited and translated in Campbell and Caplan, eds., Daumier 1808–1879, 13.

-

The authors are grateful to former Nelson-Atkins curators Simon Kelly and Nicole R. Myers, and conservation scientist Johanna Bernstein for their contributions in the early stages of this research project.

-

Results from the technical study were disseminated in two prior publications. See Louisa M. Smieska, John Twilley, Arthur R. Woll, Mary Schafer, and Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “Energy-optimized Synchrotron XRF Mapping of an Obscured Painting beneath Exit from the Theater, Attributed to Honoré Daumier,” Microchemical Journal 146 (2019): 679–91. Mary Schafer, John Twilley, Louisa Smieska, Arthur Woll, and Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “Technical Study of a Painting Attributed to Honoré Daumier at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art” AIC Paintings Specialty Group: Postprints; Papers Presented at the 47th Annual Meeting, New England (Washington, DC: American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works, 2021), 101–24.

-

Regis B. Miller, wood information specialist, November 29, 2016, unpublished report, NAMA conservation file, no. 31–30. Miller identified the panel as African mahogany, a species of Khaya.

-

Aviva Burnstock and Mark Evans, “Three Daumiers in Cardiff Reassessed,” Burlington Magazine 142, no. 1166 (May 2000): 283.

-

Campbell and Caplan, eds., Daumier 1808–1879, 23.

-

EROS database 2.0, Department of Archives and Innovative Information Technology, Center for Research and Restoration of Museums of France, F13445 and F10969, accessed August 7, 2011.

-

Campbell and Caplan, eds., Daumier 1808–1879, 23.

-

Elizabeth Steele, paintings conservator, Phillips Collection, noted in her 1999 examination report that the underlying portrait “does not bear any resemblance to any style of painting by Daumier, but rather, appears to be from a much earlier period (17th–19th century).”

-

See Campbell and Caplan, eds., Daumier 1808–1879, 23.

-

The film-based radiograph of Exit from the Theater was captured under the following conditions: 80 kV, 1 mA, 20 seconds. See radiograph no. 502, June 14, 2010, NAMA conservation file, 32–31.

-

The mock-up panel was sized to simulate the absorbency of a painted surface, and commercial lead white paint was applied with a brayer. See digital radiograph no. 470, November 2, 2011, NAMA conservation file, no. 32–31.

-

Radiographs for these paintings were graciously provided by conservators Ann Hoenigswald, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, and Allison Langley, Art Institute of Chicago. The authors are grateful to the many conservators who shared scans of existing Daumier radiographs as well as the following colleagues who captured new radiographs on behalf of this project: Miho Takashima (National Museum of Western Art, Tokyo), Ellen Hanspach-Bernal and Aaron Steele (Detroit Institute of Arts), Barbara Buckley (Barnes Foundation), and Alexander Kossolapov (Hermitage Museum).

-

Aviva Burnstock and William Bradford, “An Examination of the Relationship between the Materials and Techniques Used for Works on Paper, Canvas, and Panel by Honoré Daumier” in Painting Techniques: History, Materials and Studio Practice; contributions to the Dublin Congress, 7–11 September 1998 (London: International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works, 1998), 217–22.

-

Schafer, Twilley, Smieska, Woll, and Marcereau DeGalan, “Technical Study of a Painting Attributed to Honoré Daumier at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art,” 103.

-

Burnstock and Bradford, “An Examination of the Relationship between the Materials and Techniques Used for Works on Paper, Canvas, and Panel by Honoré Daumier,” 219.

-

Rik Klein Gotink, of the Bosch Research and Conservation Project, kindly captured infrared imagery of Exit from the Theater using an Osiris InGaAs camera.

-

These inconsistencies are outlined in the accompanying entry by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan.

-

Maison, Honoré Daumier, 39.

-

Smieska, Twilley, Woll, Schafer, and Marcereau DeGalan, “Energy-optimized Synchrotron XRF Mapping of an Obscured Painting beneath Exit from the Theater, Attributed to Honoré Daumier,” 679–91.

-

This work is based upon research conducted at the Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source (CHESS) which is supported by the National Science Foundation under award DMR-1332208. Our colleagues Arthur Woll and Louisa Smieska at CHESS were essential to all aspects of the synchrotron XRF and post processing with GeoPIXE. The microanalytical study and costs associated with XRF mapping were supported by an endowment from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation for conservation science at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Logistical support in Ithaca was provided by the Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art at Cornell University, especially Andrew Weislogel and Matt Conway.

-

C. G. Ryan et al., “The Maia Detector and Event Mode,” Synchrotron Radiation News Technical Reports (2018): 21–27, doi:10.1080/08940886.2018.1528430.

-

R. Kirkham et al., “The Maia Spectroscopy Detector System: Engineering for Integrated Pulse Capture, Low-latency Scanning and Real-time Processing,” American Institute of Physics Conference Proceedings 1234, no. 1 (June 2010): 240–43, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3463181.

-

“GeoPIXE: Quantitative PIXE Imaging and Analysis Software,” CSIRO Earth Science and Resource Engineering, accessed November 9, 2020, http://nmp.csiro.au/GeoPIXE.html. The dynamic analysis (DA) approach contained in GeoPIXE is a fundamental-parameters technique for extracting element concentrations from XRF intensity, formally equivalent to linear least-squares fitting of spectra.

-

Performed with an excitation energy of 12.9 keV, below the lead L3 absorption edge (13.035 keV), to improve imagery for elements with x-ray ionization edges below that of lead.

-

Performed with an excitation energy of 38.5 keV, resulting in maps from several elements known to be present in both paintings but whose emission cannot be induced by the lower incident energy of the first run, namely the lead (Pb) L, strontium (Sr) K, and barium (Ba) K lines.

-

Deterioration of the pigments, along with their small proportion, may also be a factor in this difficulty. Early versions of cadmium yellow have often been observed to undergo oxidation and may suffer adverse interactions with copper pigments such as the copper arsenite known to be used in the landscape. See, for example: E. Pouyet et al., “2D X-ray and FTIR Micro-analysis of the Degradation of Cadmium Yellow Pigment in Paintings of Henri Matisse,” Applied Physics A 121 (2015): 967, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00339-015-9239-4; and J. Mass, J. Sedlmair, C. Schmidt Patterson, D. Carson, B. Buckley, C. Hirschmugl, “SR-FTIR Imaging of the Altered Cadmium Sulfide Yellow Paints in Henri Matisse’s Le Bonheur du vivre (1905–6)—Examination of Visually Distinct Degradation Regions,” Analyst 138 (2013): 6032–43, https://doi.org/10.1039/C3AN00892D.

-

John Hanning Speke, Journal of the Discovery of the Source of the Nile (London: William Blackwood and Sons, 1863), 45.

-

James Augustus Grant, watercolor sketches, MS 17920, Archives and Manuscript Collection, National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh.

-

Speke, Journal of the Discovery of the Source of the Nile, 47, 62.

-

John Hanning Speke to William Blackwood, February 9, 1864, MS 4191, fols. 162–163, Blackwood Papers, Archives and Manuscript Collection, National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh.

-

Speke traveled to Paris in 1864 and could have commissioned an artist at that time. His correspondence confirms that he was in Paris correcting proofs for the French publication of his travel account. See John Hanning Speke to William Blackwood, March 31, 1864, Folio 4193, Archives and Manuscript Collection, National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh. He was also in Paris at the invitation of Emperor Napoleon III, who offered support for a future expedition. Sidney Lee, ed., Dictionary of National Biography 53 (New York: MacMillan Company, 1898), 326.

-

John Hanning Speke, Journal of the Discovery of the Source of the Nile (Hachette: Paris, 1864).

-

Leila Koivunen, Visualizing Africa in Nineteenth-Century British Travel Accounts (New York: Routledge, 2009), 7, 109.

-

Eugene Bouvy, Daumier: L’Oeuvre gravé du maître (Paris: Le Garrec, 1933), 1:11.

-

These artists include Adolphe François Pannemaker (1822–1900), Antoine Valérie Bertrand (b. 1823), J. Gauchard Brunier (n.d.), Alexandre de Bar (1821–1901), Charles LaPlante (1837–1903), and Jules Jean Marie Joseph Huyot (1841–1921).

-

The commercial introduction of cerulean blue is generally credited to Rowney in the year 1860 for use as a watercolor pigment, with its introduction for oil coming only in 1870. These dates could be seen as discrediting the attribution of the theater scene to Daumier since the pigment occurs in oil in the underlying landscape that must have preceded it in date. However, the material itself was known as early as 1805 and has been reported to have been sold earlier in Germany in the 1800s. (Winsor Newton, http://www.winsornewton.com/na/articles/ colours/spotlight-on-cerulean-blue/ accessed November 9, 2020)

-

Bruce Laughton, Honoré Daumier (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996), 60.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Attributed to Honoré Daumier, Exit from the Theater, after 1863,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.512.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Attributed to Honoré Daumier, Exit from the Theater, after 1863,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.512.4033

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Attributed to Honoré Daumier, Exit from the Theater, after 1863,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.512.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Attributed to Honoré Daumier, Exit from the Theater, after 1863,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.512.4033.

[Paul?] Junger[s?] (d. ca. 1934), Paris, possibly by May 1923–no later than December 11, 1931 [1];

With Richard Owen, Paris, by December 1931–April 1, 1932 [2];

Purchased from Owen, through Harold Woodbury Parsons, by The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1932 [3].

NOTES

[1] The spelling of this constituent’s name varies, but is most often found as Jungers. See K. E. Maison, Honoré Daumier Catalogue Raisonné of the Paintings, Watercolours and Drawings (London: Thames and Hudson, 1968), no. I-7, I-172, and I-194. For the possible first name Paul, see deaccession proposal for Felix Zeim, Still Life with Fish, 32–178, NAMA registrar files. In December 1931, Paris-based art dealer and specialist in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century drawings, Richard Owen (1873–1946), was looking for buyers for four Daumier pictures he had recently purchased from a “well-known French collector [Jungers]”. See correspondence from Harold Woodbury Parsons, NAMA art agent, to J. C. Nichols, NAMA trustee, December 11, 1931, NAMA curatorial files. Through the assistance of Owen, NAMA acquired the Daumier and several other works from this collector. See Harold Woodbury Parsons to William Mathewson Milliken, former director of the Cleveland Museum of Art, June 10, 1932, Cleveland Museum of Art Archives.

[2] Jungers may have owned the painting as early as May 1923 when it may have been exhibited at Exposition Daumier et Gavarni, Maison de Victor-Hugo, Paris, May–July 1923.

[3] The painting was placed on view at the Kansas City Art Institute from March 14, 1932 until after May 20, 1932, since the museum was not yet built. See “Objects owned by the W.R. Nelson Trust on exhibit at the K.C. Art Institute as of March 14, 1932,” March 14, 1932, NAMA Archives, William Rockhill Nelson Trust Office Records 1926–33, RG 80/05, Series I, box 02, folder 17, Exhibition at the Kansas City Art Institute, 1932 and remained in the Art institute after May 20, 1932. See also, “Pictures remaining in the Art Institute after May 20, 1932,” May 20, 1932, NAMA Archives, William Rockhill Nelson Trust Office Records 1926–33, RG 80/05, Series I, box 02, folder 17, Exhibition at the Kansas City Art Institute, 1932.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Attributed to Honoré Daumier, Exit from the Theater, after 1863,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.512.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Attributed to Honoré Daumier, Exit from the Theater, after 1863,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.512.4033.

Charles Maurand, after Honoré Daumier, Sortant du Drame: Boulevard du Temple à Minuit, 1862, wood engraving on paper, 8 7/8 x 6 5/16 in. (22.6 x 16 cm), The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City.

Charles Maurand, after Honoré Daumier, Les théâtres: sortant du drame et sortant des funambules, 1862, wood engraving on paper, 8 7/8 x 6 5/16 in. (22.6 x 16 cm), The Cleveland Museum of Art.

Charles Maurand, after Honoré Daumier, Boulevard du Temple à Minuit, 1862, wood engraving on paper, 8 7/8 x 6 5/16 in. (22.6 x 16 cm), National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

Honoré Daumier, Leaving the Theater, ca. 1865, oil on canvas, 13 1/8 in. x 16 1/4 in. (33.3 x 41.3 cm), San Diego Museum of Art.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Attributed to Honoré Daumier, Exit from the Theater, after 1863,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.512.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Attributed to Honoré Daumier, Exit from the Theater, after 1863,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.512.4033.

Possibly Exposition Daumier et Gavarni, Maison de Victor-Hugo, Paris, May–July 1923.

One Hundred Years of French Painting, 1820–1920, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, March 31–April 28, 1935, no. 15, as Exit from the Theater.

Forty-Seventh Annual Exhibition of Paintings, Nebraska Art Association, Lincoln, NE, February 28–March 28, 1937, no. 42, as Exit from a Theater.

Old Master of the Month, Mulvane Art Center, Washburn University, Topeka, KS, April 6–26, 1949, no cat.

Fine Arts Festival, Allyn Art Gallery, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, IL, February 26–March 10, 1956, no. 6, as Exit from the Theater.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Attributed to Honoré Daumier, Exit from the Theater, after 1863,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.512.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Attributed to Honoré Daumier, Exit from the Theater, after 1863,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.512.4033.

Possibly Exposition Daumier et Gavarni, exh. cat. (Paris: Maison de Victor-Hugo, 1923).

M[inna] K. P[owell], “A New Nelson Group: Paintings and Drawings are Added to Gallery,” Kansas City Star 52, no. 206 (April 10, 1932): 11A, as Theater Exit.

M[inna] K. P[owell], “Art: Mr. Parsons Will Be Heard Thursday Night on ‘The Italian Renaissance;’ What Is to Be Seen in the Group of Recently Acquired Paintings for the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art Was Told the Hospitality Committee Yesterday by Him,” Kansas City Times 95, no. 88 (April 12, 1932): 10, as Theater Exit.

M[inna] K. P[owell], “Daumier, Greatest of All the French Artists, Unsung in his Own Country,” Kansas City Star 53, no. 233 (May 8, 1933): C[14].

M[inna] K. P[owell], “The Gallery and Studio,” Kansas City Star 53, no. 308 (July 22, 1933): 5.

M[inna] K. P[owell], “Art Shows the Layman Something He is Unable to See for Himself,” Kansas City Star 54, no. 49 (November 5, 1933): 8D, (repro.).

“Nelson Gallery of Art Special Number,” Art Digest 8, no. 5 (December 1, 1933): 13–14, 21, 25 (repro.), as Exit from the Theatre.

Alfred M. Frankfurter, “Paintings in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art,” Art News 32, no. 10 (December 9, 1933): 29–30, 43, (repro.), as Sortie du Theatre.

Minna K. Powell, “The First Exhibition of the Great Art Treasures: Paintings and Sculpture, Tapestries and Panels, Period Rooms and Beautiful Galleries Are Revealed in the Collections Now Housed in the Nelson-Atkins Museum,” Kansas City Star 54, no. 84 (December 10, 1933): 4C, as Leaving the Theater.

“$15,000,000 Nelson Art Gallery Opens: Gift of Kansas City Star Publisher,” Boston Evening Transcript 104, no. 288 (December 11, 1933): 11.

“Art Critics View Nelson Gallery: Preview of Edifice, Costing $15,000,000 With Contents, Held at Kansas City,” New York Times 80, no. 27,715 (December 11, 1933): 24.

“Nelson Gallery of Art Opened at Kansas City: $14,000,000 Gift of ‘Star’ Publisher and His Heirs Already Fully Furnished; Has Many Innovations; Oriental, Roman, Colonial Objects World Famous,” New York Herald Tribune 93, no. 31,802 (December 11, 1933): 12, as Sortie du Theater.

Nan Sheets, “Programs, Plays, Pageants Planned by The Nelson Gallery of Art,” Daily Oklahoman 41, no. 341 (December 15, 1933): 15.

“Nelson Gallery of Art Opens,” New York City Editor and Publisher 66, no. 31 (December 16, 1933): 10.

M[inna] K. P[owell], “The Gallery and Studio,” Kansas City Star 54, no. 90 (December 16, 1933): 12.

Luigi Avian, “Art Dream Becomes Reality with Official Gallery Opening at Hand: Critic Views Wide Collection of Beauty as Public Prepares to Pay its First Visit to Museum,” Kansas City Journal-Post 80, no. 193 (December 17, 1933): 7, as Sortie de Theatre.

“Praises the Gallery: Dr. Nelson M’Cleary, Noted Artist, a Visitor,” Kansas City Star 54, no. 98 (December 24, 1933): 9A, as Exit from a Theater.

Thomas Carr Howe, “Kansas City Has Fine Art Museum: Nelson Gallery Ranks with the Best,” [unknown newspaper] (ca. December 1933), clipping, scrapbook, NAMA Archives, vol. 5, p. 6, as Sortie du Theater.

The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Handbook of the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1933), 41, 52, 136, (repro.), as Exit from a Theater.

A. J. Philpott, “Kansas City Now in Art Center Class: Nelson Gallery, Just Opened, Contains Remarkable Collection of Paintings, Both Foreign and American,” Boston Sunday Globe 125, no. 14 (January 14, 1934): 16.

“Pupils Act Story of Art: Growth of The Nelson Gallery Dramatized at Ashland School,” Kansas City Times 97, no. 58 (March 8, 1934): 20, Exit From the Theater.

“A Thrill to Art Expert: M. Jamot is Generous in his Praise of Nelson Gallery,” Kansas City Times 97, no. 247 (October 15, 1934): 7.

Ellen Josephine Green, “The Fine Arts,” Musical Bulletin 23, no. 2 (November 1934): 8, as Sortie du Theatre.

One Hundred Years French Painting, 1820–1920 , exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1935), unpaginated, (repro.), as Exit from the Theater.

P[aul] V. B[eckley], “Art News,” Kansas City Journal-Post 81, no. 197 (April 7, 1935): 8–B.

“Wilmington Sees Old Masters’ Art,” New York Times 84, no. 28,202 (April 12, 1935): 21.

Harold Callender, “A Reply to Critics Of the Midwest Mind,” New York Times 83, no. 28, 876 (February 14, 1937): 5.

Forty-Seventh Annual Exhibition of Paintings, exh. cat. (Lincoln, NE: Nebraska Art Association, 1937), unpaginated, (repro.), as Exit from a Theater.

“Annual Nebraska Art Association Exhibit Officially Opens February 28,” Lincoln Sun Journal and Star (February 21, 1937), clipping, scrapbooks, NAMA Archives, vol. 7, pp. 64–66.

“A Great Newspaper Builds a Great Art Museum,” Life 7, no. 15 (October 9, 1939): 56, (repro.), as Exit from the Theater.

The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, The William Rockhill Nelson Collection, 2nd ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1941), 168, as Exit from the Theatre.

Dorothy Adlow, “Art in Kansas City—Music and Theaters—Exhibitions in San Francisco: Masterpieces of Many Schools To Be Seen in Nelson Gallery,” Christian Science Monitor 40, no. 197 (July 17, 1948): 12, as Exit of Theater.

“New Mulvane Exhibit Opens Wednesday,” Washburn Review (April 1, 1949): 6, as Exit from the Theater.

“12 Dutch Masters Sent Here by Metropolitan Make Up One of the New Mulvane Museum Exhibits,” Topeka State Journal (April 4, 1949): unpaginated, as Exit from the Theater.

Winifred Shields, “Daumier’s Paint Brush Could Assume the Shape of a Rapier: Eloquent in its Criticism is ‘Exit from the Theater,’ which is in Nelson Gallery,” Kansas City Star 74, no. 351 (September 3, 1954): 12, as Exit from the Theater.

Fine Arts Festival , exh. cat. ([Carbondale: Southern Illinois University, 1956]), unpaginated, (repro.), as Exit from the Theatre.

Ross E. Taggart, ed., Handbook of the Collections in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts , 4th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1959), 260, as Exit from the Theater.

John H. Bens, Some Shapers of Men (New York: Hold, Rinehart and Winston, 1968), (repro.).

Ross E. Taggart and George L. McKenna, eds., Handbook of the Collections in The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Kansas City, Missouri , vol. 1, Art of the Occident, 5th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1973), 258, as Exit from the Theater.

John D. Morse, Old Master Paintings in North America: Over 3000 Masterpeices by 50 Great Artists (New York: Abbeville Press, 1979), 88, as Exit from the Theater.

Louisa M. Smieska, John Twilley, Arthur R. Woll, Mary Schafer, and Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “Energy-optimized synchrotron XRF mapping of an obscured painting beneath Exit from the Theater, attributed to Honoré Daumier,” Microchemical Journal 146 (2019): 679–91, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.microc.2019.01.058.

Mary Schafer, John Twilley, Louisa Smieska, Arthur Woll, and Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “Technical Study of a Painting Attributed to Honoré Daumier at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art” AIC Paintings Specialty Group: Postprints; Papers Presented at the 47th Annual Meeting, New England (Washington, DC: American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works, 2021), 101–24.