Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Kathryn Calley Galitz, “Attributed to Adèle Romany, Portrait of a Boy, 1799,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.420.5407.

MLA:

Galitz, Kathryn Calley. “Attributed to Adèle Romany, Portrait of a Boy, 1799,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.420.5407.

Eighteenth-century France witnessed the flourishing of the portrait; it was the most widely commissioned type of art, surging in popularity in the decade that followed the Revolution of 1789.1The definitive work on this subject is Tony Halliday, Facing the Public: Portraiture in the Aftermath of the French Revolution (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1999). Portraits painted by the leading history painters of the day, notably Jacques-Louis David (1748–1825) and his students, as well as those by lesser-known artists, lined the walls of the newly democratized SalonsSalon, the: Exhibitions organized by the French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture (Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture) and its successor the Academy of Fine Arts (Académie des Beaux Arts), which took place in Paris from 1667 onward. of the French Republic. This portrait of an unidentified boy, painted in 1799, is typical of the period in its half-length format, neutral background, and painterly restraint, all in keeping with the dominant Neoclassical style.

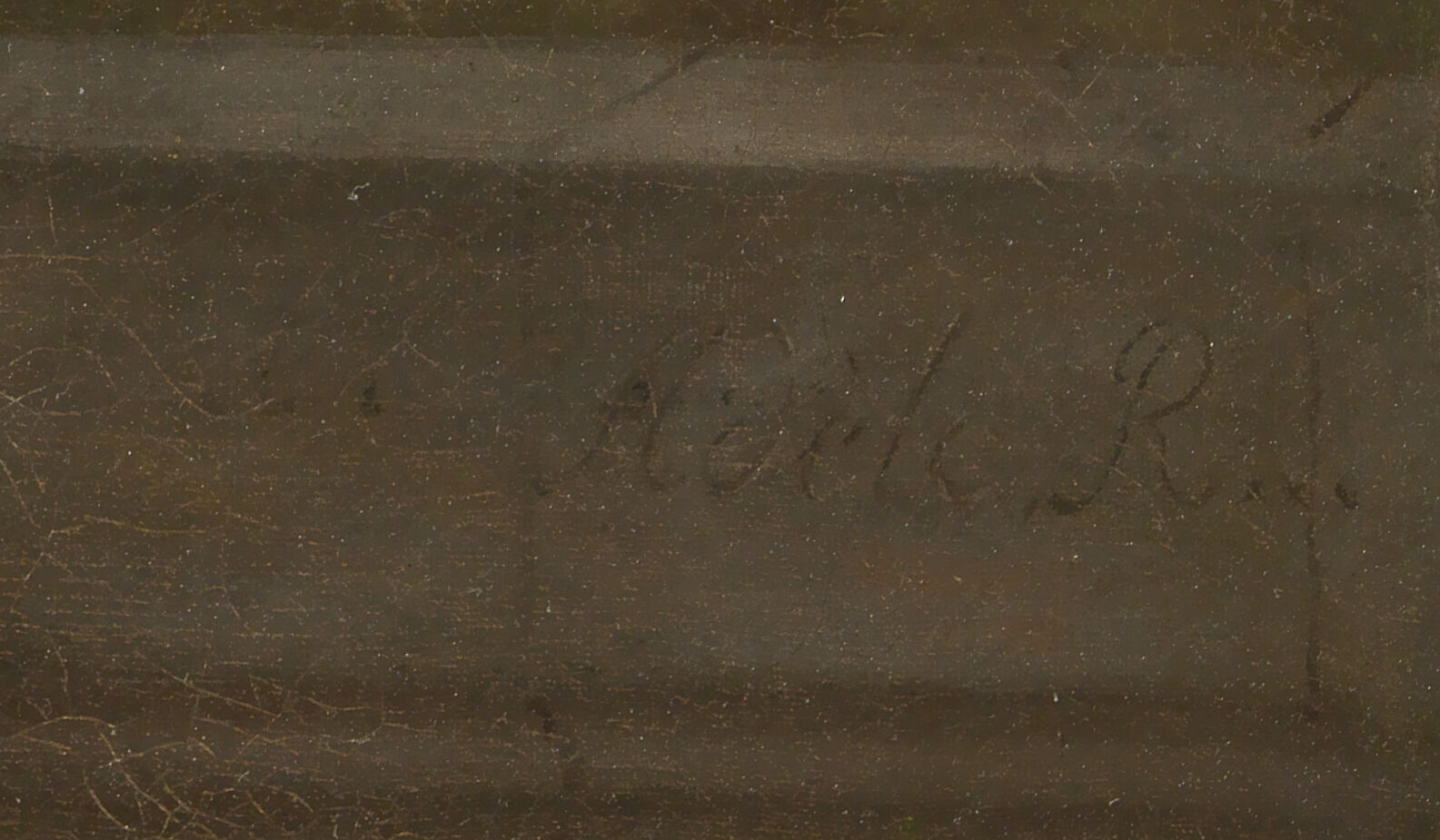

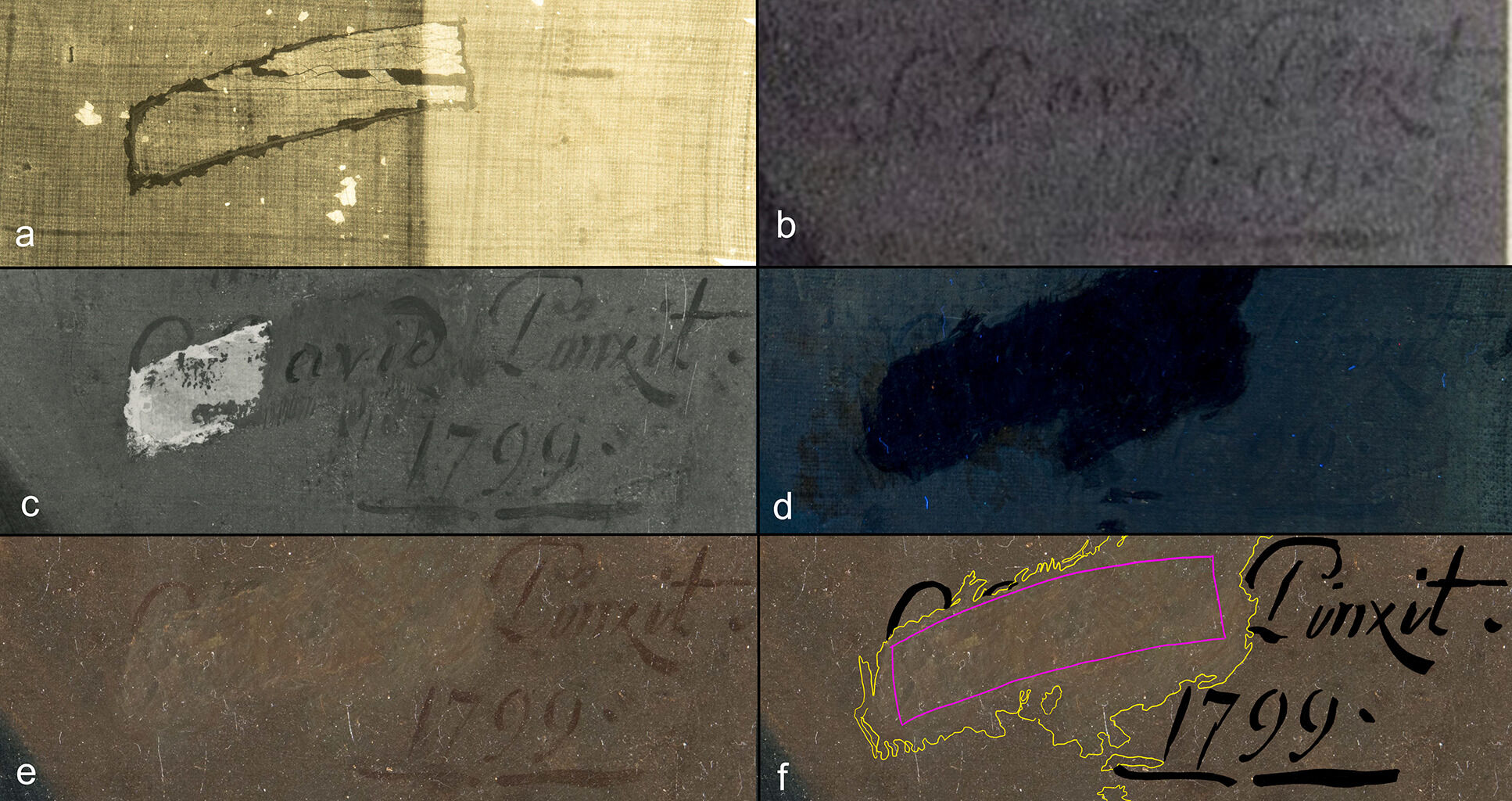

The 1913 exhibition David et ses élèves (David and His Students) in Paris engendered a renewed interest in the work of the Neoclassical master, especially his portraits, which were coveted acquisitions among prominent American collectors in the early decades of the twentieth century. Portraits falsely attributed to David were not uncommon at the time, and some of these misattributions persisted into the late twentieth century.2See Margaret A. Oppenheimer, “Four ‘Davids,’ a ‘Regnault,’ and a ‘Girodet’ Reattributed: Female Artists at the Paris Salons,” Apollo 165, no. 424 (June 1997): 38–44. In 1920, the collector Grenville L. Winthrop purchased a portrait signed “L. David” that much later was discovered to be a work by Adélaïde Labille-Guiard (1749–1803), shown in the Salon of 1799.3Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, Tournelle, called Dublin (1761–1820) (1799; Harvard Art Museums); reproduced as Fig. 2 in Laura Auricchio, “Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, Portrait of Joachim Lebreton, 1795,” entry in this catalogue, https://nelson-atkins.org/fpc/neo-classicism-romanticism/416/. See also https://harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/230367. On the American taste for portraits by David, see Philippe Bordes, “Buying Against the Grain: American Collections and French Neoclassical Paintings” in Yuriko Jackall and Joseph Baillio, America Collects Eighteenth-Century French Painting, exh. cat. (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2017), 102–5. Similarly, the Nelson-Atkins portrait was acquired in 1931 as a signed work by David; it was later discovered that the original signature had been cut out at an unknown date and replaced with “L. David,” most of which was painted on a separate piece of canvas (see Fig. 7a–f). All that remains of the original signature are two curved strokes of paint that once formed the tops of letters followed by “Pinxit” (Latin for “he/she painted [it]”) and the date “1799”. In addition, the sitter’s hair and facial features had been extensively overpaintedoverpaint: Restoration paint that covers original paint that may or may not be damaged. Historically, overpaint has often been applied too broadly, altering the intended aesthetic of the painting and sometimes introducing conceptions foreign to the original artist, thereby altering our understanding of the work and the era to which it belongs.,4For a detailed analysis of the work’s signature, see the accompanying technical essay by Susan Pavlik Enterline. suggesting an attempt to make the portrait look more Davidian. The false “David” signature and overpainting were removed in 1955; nonetheless, the attribution to David remained until 1987, and the identity of the artist has since proved elusive.5In 1987, then-curator Roger Ward publicly deattributed the work; see Donald Hoffman, “Throwing Suspicion on the Masters,” Kansas City Star, July 26, 1987. Since that time, various unsubstantiated attributions have been put forward; see the NAMA curatorial files.

In 2005, the portrait was posited as an early work by Constance Mayer (1774–1821), who exhibited a Portrait d’enfant (Portrait of a Child) at the Salon of 1799.6For the attribution to Mayer, see Margaret A. Oppenheimer, The French Portrait: Revolution to Restoration, exh. cat. (Northampton, MA: Smith College Museum of Art, 2005), 154–57. This attribution was largely based on an analysis of what remained of the work’s original signature and an assumption that a capital “C” had been inscribed. Mayer also occasionally deployed the Latin “pinxit” following her signature, which was not a common practice at the time. However, the attribution to Mayer fails to convince on stylistic grounds. A comparison with an early work by Mayer (Fig. 1) reveals significant differences in the modeling of the flesh and treatment of the hair, which bear little stylistic resemblance to the Nelson-Atkins canvas.7For another comparison, see Constance Mayer, Citoyenne Mayer, Painted by Herself, Showing a Sketch of her Mother’s Portrait, ca. 1796, private collection, illustrated in Paris A. Spies-Gans, A Revolution on Canvas: The Rise of Women Artists in Britain and France, 1760–1830 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2024), 192, fig. 96.

Fig. 2. Adèle Romany, Portrait of Auguste Vestris, 1793, oil on canvas, 37 1/2 x 30 in. (95.2 x 76.2 cm), Rhode Island School of Design Museum, Providence, RI, Purchased with the Edith C. Erlenmeyer Bequest and the Helen M. Danforth Acquisition Fund, 2009.9. Photo: Courtesy of the RISD Museum, Providence, RI

Fig. 2. Adèle Romany, Portrait of Auguste Vestris, 1793, oil on canvas, 37 1/2 x 30 in. (95.2 x 76.2 cm), Rhode Island School of Design Museum, Providence, RI, Purchased with the Edith C. Erlenmeyer Bequest and the Helen M. Danforth Acquisition Fund, 2009.9. Photo: Courtesy of the RISD Museum, Providence, RI

Fig. 3. Detail of signature, exposure brightened for legibility; Attrib. Adèle Romany, Portrait of Auguste Vestris, 1793

Fig. 3. Detail of signature, exposure brightened for legibility; Attrib. Adèle Romany, Portrait of Auguste Vestris, 1793

Portrait of a Boy presents striking similarities with the early work of Adèle Romany (1769–1846), a prolific artist who exhibited more than eighty works, mostly portraits, at the Paris Salon from 1793 to 1833.8On the artist, see Aurélie Vandevoorde, “Adèle Romany, une portraitiste à redécouvirir,” L’Objet d’Art, no. 436 (June 2008): 50–55; Jordana Pomeroy et al., Royalists to Romantics: Women Artists from The Louvre, Versailles, and Other French National Collections, exh. cat. (Washington, DC: National Museum of Women in the Arts, 2012), 107; and Spies-Gans, A Revolution on Canvas, 195–96, 198, 287. In an August 2012 conversation with the author, Kenneth Brummel, former project assistant, NAMA, suggested Romany as a possible attribution based on her 1793 portrait of Auguste Vestris (Fig. 2). The angled placement of the figure, head turned to face outward, echoes the pose of the dancer Auguste Vestris in a portrait by Romany signed and dated 1793 (Fig. 2). The similar treatment of the various textures of the sitters’ attire especially resonates: in both works, the soft folds of the shirt and waistcoat are rendered with loose, painterly brushwork, and scattered highlights of pale blue and white paint run along the edges of the jacket, a particularly idiosyncratic touch. In both portraits, the modeling of the face and handling of the flesh also accord, notably the distinctive way the artist accents the philtrum above the slightly parted lips, which recur in other contemporaneous portraits by Romany. Finally, the portrait of Vestris is signed “Adèle R xxx” (Fig. 3); it may well be that the fragments of the original signature that remain on Portrait of a Boy are the top strokes of the cursive letters “A” and “d.”

A group of family portraits painted by Romany around 1800 appeared on the art market in 2008, among them a double portrait of Romany’s second cousins, which was shown at the Salon of 1800 (Fig. 4). It strongly suggests the same hand as that of the Nelson-Atkins work in the rendering of the facial features, especially the shape and treatment of the heavy-lidded eyes. In addition, the slight head tilt of both sitters, characteristic of Romany’s early portraits, aligns the double portrait with Portrait of a Boy. Another portrait, dated 1795–1800, depicts the same young woman in a pose like that of the sitter in the present work, her silhouetted form rendered in similarly softened contours.9Adèle Romany, Portrait of Amélie-Justine Pontois, ca. 1795–1800, in Tableaux Anciens et du 19ème Siècle (Paris: Christie’s, June 26, 2008), lot 80, https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-5097715. These portraits recall Romany’s self-portrait of about 1798, in which she portrayed herself with similar heavy-lidded eyes, head slightly inclined to the left (Fig. 5). The handling of the long curls that trail down to her shoulder mirrors the way that individual curls are delineated in the portrait at the Nelson-Atkins.10For an additional comparison with Portrait of a Boy, see the fragment of a self-portrait, probably “Portrait de l’auteur, avec ses deux enfans” (Portrait of the Author with her Two Children) (no. 323 in the Salon of 1800), in Christie’s, La Vie de Château, collection Jean-Louis Remilleux, September 29, 2015, Paris, lot 187, https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-5929877. Not incidentally, this magisterial self-portrait was long thought to be by David, and it still bears an erroneous inscription “J. L. David An II” on the footstool to the right.11For the attribution to Romany, see Oppenheimer, “Four ‘Davids,’” 39–40; see also the catalogue entry on the work by Stéphane Guégan in Joseph Baillio and Xavier Salmon, Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, exh. cat. (Paris: Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 2015), 140.

Romany trained in a studio for women artists run by Sophie Regnault (1763–1825), wife of the painter Jean-Baptiste Regnault (1754–1829), and she presented herself as a “student of Regnault” in the Salon livrets, or catalogues, throughout the 1790s. The softened contours and relatively tight brushwork of the facial features in the Nelson-Atkins portrait comport with Romany’s assimilation of Regnault’s Neoclassicism in her early work. The portrait was painted directly on the canvas, with no apparent underdrawingunderdrawing: A drawn or painted sketch beneath the paint layer. The underdrawing can be made from dry materials, such as graphite or charcoal, or wet materials, such as ink or paint. or changes, evidence of the artist’s assured handling. In addition, the paint is fluidly and rapidly laid down, often wet-into-wetwet-into-wet: An oil painting technique which involves blending of colors on the picture surface., as visible in the white stripes of the waistcoat and the flickering highlights on the edges of the jacket’s lapel. The background is thinly and evenly brushed, in contrast to the scumbledscumble: A thin layer of opaque or semi-opaque paint that partially covers and modifies the underlying paint. backgrounds characteristic of David’s portraits from the 1790s.12See the accompanying technical essay by Susan Pavlik Enterline for an analysis of the artist’s technique. The youthful sitter is also in keeping with the subjects of Romany’s contemporaneous portraits on view at the Salons of 1799 and 1800, in which children and young people figure prominently.13Of the eight portraits listed under Romany’s name in the Salon catalogues in 1799 and 1800, children or young people appear in three: A Young Girl Seated on a Stool (“une jeune fille assise sur un tabouret,” no. 276, Salon of 1799); Portrait of the Author with Her Two Children (“Portrait de l’auteur, avec ses deux enfans,” no. 323, Salon of 1800); Portrait of a Young Person and Her Brother (“Portrait d’une jeune personne et de son frère,” no. 325, Salon of 1800; Fig. 4). In addition, an oval portrait of Amélie-Justine Pontois may have been one of the “Deux Portraits ovales, sous le meme numero” (two oval portraits, under the same number) exhibited in 1799 under no. 279 (on this work, see Vandevoorde “Adèle Romany, une portraitiste à redécouvirir,” 52–53). Both the handling and the subject of Portrait of a Boy support an attribution to Adèle Romany, an artist no longer in the shadow of David.

Notes

-

The definitive work on this subject is Tony Halliday, Facing the Public: Portraiture in the Aftermath of the French Revolution (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1999).

-

See Margaret A. Oppenheimer, “Four ‘Davids,’ a ‘Regnault,’ and a ‘Girodet’ Reattributed: Female Artists at the Paris Salons,” Apollo 165, no. 424 (June 1997): 38–44.

-

Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, Tournelle, called Dublin (1761–1820) (1799; Harvard Art Museums); reproduced as Fig. 2 in Laura Auricchio, “Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, Portrait of Joachim Lebreton, 1795,” entry in this catalogue, https://nelson-atkins.org/fpc/neo-classicism-romanticism/416/. See also https://harvardartmuseums.org/collections

/object/230367. On the American taste for portraits by David, see Philippe Bordes, “Buying Against the Grain: American Collections and French Neoclassical Paintings” in Yuriko Jackall and Joseph Baillio, America Collects Eighteenth-Century French Painting, exh. cat. (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2017), 102–5. -

For a detailed analysis of the work’s signature, see the accompanying technical essay by Susan Pavlik Enterline.

-

In 1987, then-curator Roger Ward publicly deattributed the work; see Donald Hoffman, “Throwing Suspicion on the Masters,” Kansas City Star, July 26, 1987. Since that time, various unsubstantiated attributions have been put forward; see the NAMA curatorial files.

-

For the attribution to Mayer, see Margaret A. Oppenheimer, The French Portrait: Revolution to Restoration, exh. cat. (Northampton, MA: Smith College Museum of Art, 2005), 154–57.

-

For another comparison, see Constance Mayer, Citoyenne Mayer, Painted by Herself, Showing a Sketch of her Mother’s Portrait, ca. 1796, private collection, illustrated in Paris A. Spies-Gans, A Revolution on Canvas: The Rise of Women Artists in Britain and France, 1760–1830 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2024), 192, fig. 96.

-

On the artist, see Aurélie Vandevoorde, “Adèle Romany, une portraitiste à redécouvirir,” L’Objet d’Art, no. 436 (June 2008): 50–55; Jordana Pomeroy et al., Royalists to Romantics: Women Artists from The Louvre, Versailles, and Other French National Collections, exh. cat. (Washington, DC: National Museum of Women in the Arts, 2012), 107; and Spies-Gans, A Revolution on Canvas, 195–96, 198, 287. In an August 2012 conversation with the author, Kenneth Brummel, former project assistant, NAMA, suggested Romany as a possible attribution based on her 1793 portrait of Auguste Vestris (Fig. 2).

-

Adèle Romany, Portrait of Amélie-Justine Pontois, ca. 1795–1800, in Tableaux Anciens et du 19ème Siècle (Paris: Christie’s, June 26, 2008), lot 80, https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-5097715.

-

For an additional comparison with Portrait of a Boy, see the fragment of a self-portrait, probably “Portrait de l’auteur, avec ses deux enfans” (Portrait of the Author with her Two Children) (no. 323 in the Salon of 1800), in Christie’s, La Vie de Château, collection Jean-Louis Remilleux, September 29, 2015, Paris, lot 187.

-

For the attribution to Romany, see Oppenheimer, “Four ‘Davids,’” 39–40; see also the catalogue entry on the work by Stéphane Guégan in Joseph Baillio and Xavier Salmon, Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, exh. cat. (Paris: Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 2015), 140.

-

See the accompanying technical essay by Susan Pavlik Enterline for an analysis of the artist’s technique.

-

Of the eight portraits listed under Romany’s name in the Salon catalogues in 1799 and 1800, children or young people appear in three: A Young Girl Seated on a Stool (“une jeune fille assise sur un tabouret,” no. 276, Salon of 1799); Portrait of the Author with Her Two Children (“Portrait de l’auteur, avec ses deux enfans,” no. 323, Salon of 1800); Portrait of a Young Person and Her Brother (“Portrait d’une jeune personne et de son frère,” no. 325, Salon of 1800; Fig. 4). In addition, an oval portrait of Amélie-Justine Pontois may have been one of the “Deux Portraits ovales, sous le meme numero” (two oval portraits, under the same number) exhibited in 1799 under no. 279 (on this work, see Vandevoorde, “Adèle Romany, une portraitiste à redécouvirir,” 52–53).

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Susan Pavlik Enterline, “Attributed to Adèle Romany, Portrait of a Boy, 1799,” technical entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.420.2088.

MLA:

Enterline, Susan Pavlik. “Attributed to Adèle Romany, Portrait of a Boy, 1799,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.420.2088.

A conservation treatment carried out in 1955 on Portrait of a Boy led to a drastic shift in the understanding and visual experience of the painting. Conservator James Roth removed heavy overpaintingoverpaint: Restoration paint that covers original paint that may or may not be damaged. Historically, overpaint has often been applied too broadly, altering the intended aesthetic of the painting and sometimes introducing conceptions foreign to the original artist, thereby altering our understanding of the work and the era to which it belongs., which had thickened the figure’s eyebrows, changed the shape of his nose, and softened his chin (Fig. 6). His hair was almost completely overpainted.1James Roth, treatment report, December 1955, NAMA conservation file, inv. no. 31-58. For more on Roth and conservation at the Nelson-Atkins, see Seth Adam Hindin, “How the West Was Won: Charles Muskavitch, James Roth, and the Arrival of ‘Scientific’ Art Conservation in the Western United States,” Journal of Art Historiography 11 (2014): 1–50. A radiographX-ray radiography (also referred to as x-radiography or radiography): Radiography is an examination tool analogous to the use of X-rays in medicine whereby denser components of a painted composition can be recorded as an inverted shadow image cast on film or a digital X-ray imaging plate from a source such as an X-ray tube. The method has been used for more than a century and is most effective with dense pigments incorporating metallic elements such as lead or zinc. It can reveal artist changes, underlying compositions, and information concerning the artwork’s construction and condition. The resulting image is called an x-radiograph or radiograph. It differs from the uses of X-ray spectrometry in being dependent on the density of the paint to absorb X-rays before they reach the film or image plate and being non-specific as to which elements are responsible for the resulting shadow image. (Fig. 7a) taken during the treatment revealed a rectangular canvas insertcanvas insert: A canvas insert (or inlay) is a piece of fabric that is set into a large area of loss in a painting’s canvas. To differentiate, a patch is typically applied to the back of a canvas to reinforce a small area of damage., measuring approximately 1.5 by 4 centimeters, located in the lower right quadrant. Of consequence, what was considered at the time to be the original signature of artist Jacques Louis David (1748–1825) was inscribed over this repair: “L. David” (Fig. 7b).2See film-based radiographs, no. 45, NAMA conservation file, 31-58. Roth determined that the paint covering the canvas insert differed from that of the rest of the painting, confirming the inscription’s inauthentic status (Fig. 7c). Therefore, the inscription was removed, and the exposed white fillfill material: A material added to a loss of paint and/or ground to create an area level with the surrounding original paint. was retouchedretouching: Paint application by a conservator or restorer to cover losses and unify the original composition. Retouching is an aspect of conservation treatment that is aesthetic in nature and that differs from more limited procedures undertaken solely to stabilize original material. Sometimes referred to as inpainting or retouch. to integrate with the surrounding background (Fig. 7d).

Fig. 6. Comparison of detail images of the figure’s head, Portrait of a Boy (1799). The left photograph was taken prior to the 1955 conservation treatment and reproduced in Georges Wildenstein, David (Paris: Les Beaux-Arts, 1963) as plate 107. On the right, the current state of the painting is shown in normal illumination.

Fig. 6. Comparison of detail images of the figure’s head, Portrait of a Boy (1799). The left photograph was taken prior to the 1955 conservation treatment and reproduced in Georges Wildenstein, David (Paris: Les Beaux-Arts, 1963) as plate 107. On the right, the current state of the painting is shown in normal illumination.

Figs. 7a–f. Comparison of various details of the lower right inscription, Portrait of a Boy (1799). 7a: Detail of radiograph, showing the void in the canvas and canvas insert; 7b: non-original signature, “L. David,” prior to 1955 treatment (Wildenstein, plate 107); 7c: during treatment photograph, showing partially removed non-original signature; 7d: detail from longwave ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescence image, showing the extent of retouching over the canvas insert, visible as dark areas; 7e: current state of inscription in normal light; 7f: diagram tracing what remains of the earlier inscription.

Figs. 7a–f. Comparison of various details of the lower right inscription, Portrait of a Boy (1799). 7a: Detail of radiograph, showing the void in the canvas and canvas insert; 7b: non-original signature, “L. David,” prior to 1955 treatment (Wildenstein, plate 107); 7c: during treatment photograph, showing partially removed non-original signature; 7d: detail from longwave ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescence image, showing the extent of retouching over the canvas insert, visible as dark areas; 7e: current state of inscription in normal light; 7f: diagram tracing what remains of the earlier inscription.

A question remains unanswered: what prompted the canvas to be cut? The clean cuts in this area (evident in the radiograph), coupled with the location over what was likely a signature, suggest a deliberate excision from the original canvas rather than accidental damage. What original characters now remain are a few disjointed reddish-brown paint strokes accompanied by the word “Pinxit .” and the year “1799 ∙” (Figs. 7e–f). Multiple iterations of retouching obscure the original paint left behind; future analysis and study may offer a clearer understanding of the significant yet fragmented inscription.

Prior to its acquisition in 1931, Portrait of a Boy was glue-paste linedlining: A procedure used to reinforce a weakened canvas that involves adhering a second fabric support using adhesive, most often a glue-paste mixture, wax, or synthetic adhesive., and its tacking marginstacking margins: The outer edges of canvas that wrap around and are attached to the stretcher or strainer with tacks or staples. See also tacking edge. were removed. The lining fully obscures the canvas insert and limits study of the original plain-weaveplain weave: A basic textile weave in which one weft thread alternates over and under the warp threads. Often this structure consists of one thread in each direction, but threads can be doubled (basket weave) or tripled to create more complex plain weave. Plain weave is sometimes called tabby weave. canvas.3The x-ray shows the canvas to have a similar thread count to the fine weave of the original canvas (approximately 52 x 58 threads per inch); see Nathan Sutton, technical notes, May 2010, NAMA conservation file, 31-58. When coupled with significant losses to paint and ground on the insert, it suggests the insert may have been repurposed from a piece of the original tacking margins. Though there is strong cuspingcusping: A scalloped pattern along the canvas edges that relates to how the canvas was stretched. Primary cusping reveals where tacks secured the canvas to the support while the ground layer was applied. Secondary cusping can form when a pre-primed canvas is re-stretched by the artist prior to painting. present on all four edges of the painting, the infrared (IR) reflectograminfrared reflectogram: An infrared image captured with an electronic infrared imager, typically in the 1000-2500 nanometer range. See Infrared reflectography (IRR). (Fig. 8) reveals a light band around the perimeter that likely correlates to the groundground layer: An opaque preparatory layer applied to the support, either commercially or by the artist, to prevent absorption of the paint into the canvas or panel. See also priming layer. application and the original stretcherstretcher: A wooden structure to which the painting’s canvas is attached. Unlike strainers, stretchers can be expanded slightly at the joints to improve canvas tension and avoid sagging due to humidity changes or aging.. The measurement of this band is unequal, suggesting that the top edge was reduced by 2.5 centimeters, and the right and left edges were each trimmed .5 centimeters.4The band measures 5 centimeters wide along the bottom edge, 4.5 centimeters on the right and left edges, and only 2.5 centimeters on the top edge.

Fig. 8. Infrared reflectogram captured at 1950 nanometers, showing a light band around the perimeter, Portrait of a Boy (1799). Arrows at the top and bottom show the difference in width. Note also the inclusions in the ground layer, which appear as bright flecks.

Fig. 8. Infrared reflectogram captured at 1950 nanometers, showing a light band around the perimeter, Portrait of a Boy (1799). Arrows at the top and bottom show the difference in width. Note also the inclusions in the ground layer, which appear as bright flecks.

Fig. 9. Comparison of a photomicrograph of the proper right eye and an infrared reflectogram at 1950 nanometers of the same area, Portrait of a Boy (1799)

Fig. 9. Comparison of a photomicrograph of the proper right eye and an infrared reflectogram at 1950 nanometers of the same area, Portrait of a Boy (1799)

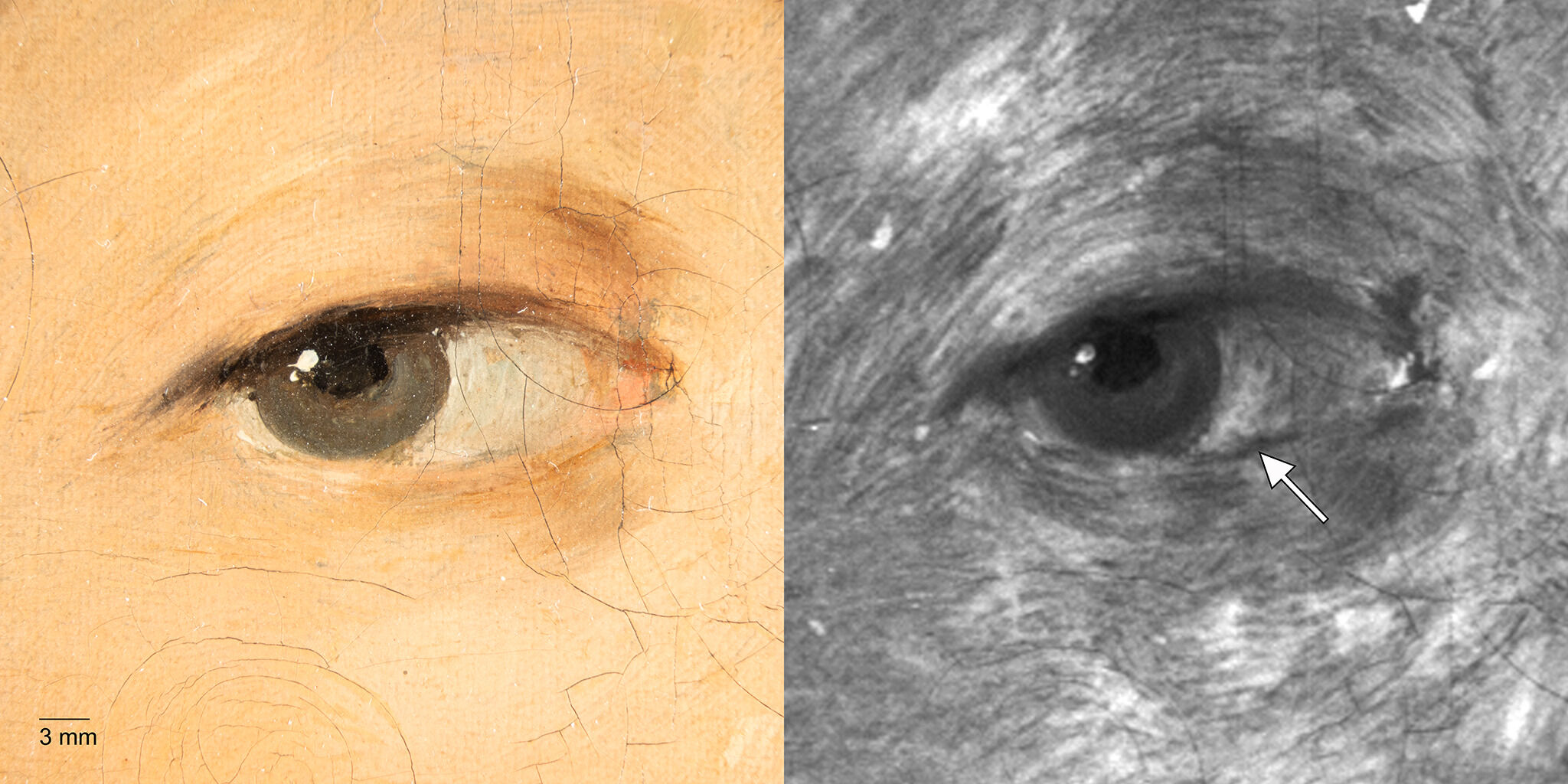

The canvas was prepared with a double ground consisting of a warm tan lower layer and a thin gray upper layer. The lower ground layer appears thick and somewhat textured with numerous radio-opaque inclusions scattered across the surface (see Fig. 8). No clear preliminary sketch or underdrawingunderdrawing: A drawn or painted sketch beneath the paint layer. The underdrawing can be made from dry materials, such as graphite or charcoal, or wet materials, such as ink or paint. was identified during examination, though there is evidence of a slightly darker bluish-gray paint used to situate the facial features (Fig. 9).

The artist painted the figure in a loose and confident manner using predominantly wet-over-wetwet-over-wet: An oil painting technique which involves drawing a stroke of one color across the wet paint of another color. brushwork. The skin tones were built up from strokes of opaque pink, peach, and yellow, allowing glimpses of the gray ground to create subtle modeling, e.g. along the lower eyelids (Fig. 10). Rich browns and reds were added to further develop dimension, for example, in the slightly parted lips (Fig. 11) and upper lash line.

Fig. 10. Photomicrograph of the figure’s proper left eye showing a glimpse of the gray ground in the lower eyelid (see the white arrow) and the transparent brown glaze adding shadow along the proper left side of the nose, Portrait of a Boy (1799)

Fig. 10. Photomicrograph of the figure’s proper left eye showing a glimpse of the gray ground in the lower eyelid (see the white arrow) and the transparent brown glaze adding shadow along the proper left side of the nose, Portrait of a Boy (1799)

Fig. 11. Photomicrograph of the figure’s lips, showing rich red paint marking the shadow and slight parting between the lips, Portrait of a Boy (1799)

Fig. 11. Photomicrograph of the figure’s lips, showing rich red paint marking the shadow and slight parting between the lips, Portrait of a Boy (1799)

Strong light casts the proper left side of the figure’s face in shadow, which was rendered with thin brown glazesglaze: A transparent, oil or resin-rich paint application that influences the tonality of the underlying paint. that extend along the nose (see Fig. 10) and down the neck. On the proper right side of the figure’s face, highlights of pale peach mark the outer corner of the bottom lip (Fig. 11), tip of the nose, and outer corner of the eyebrow. The artist added a thin stroke of white to highlight the outer edge of the lower eyelid, and small white dabs reflect light in both eyes. The same technique was used to accentuate the curve of the golden earring, with a swipe of bright orange added to capture the reflection of the ear (Fig. 12).

Fig. 12. Photomicrograph of the figure’s gold earring, with bright white highlights and orange and red-orange reflections, Portrait of a Boy (1799)

Fig. 12. Photomicrograph of the figure’s gold earring, with bright white highlights and orange and red-orange reflections, Portrait of a Boy (1799)

Fig. 13. Photomicrograph of the right side of the figure’s hair, showing added gray brushstrokes and the resulting wet-into-wet blending, Portrait of a Boy (1799)

Fig. 13. Photomicrograph of the right side of the figure’s hair, showing added gray brushstrokes and the resulting wet-into-wet blending, Portrait of a Boy (1799)

The figure’s feathery curls are constructed from short, curving strokes of rich brown. The brush was pulled from the still-wet forehead outward to the hairline, softening the transition. Strokes of gray, similar in color to the ground, were added around the outer perimeter of the hair, creating some wet-into-wetwet-into-wet: An oil painting technique which involves blending of colors on the picture surface. blending that adds fullness and depth (Fig. 13). Sweeps of an earthy yellow brighten the left side, and deep brown brushstrokes applied wet-over-drywet-over-dry: An oil painting technique that involves layering paint over an already dried layer, resulting in no intermixing of paint or disruption to the lower paint strokes. establish individual locks of hair.

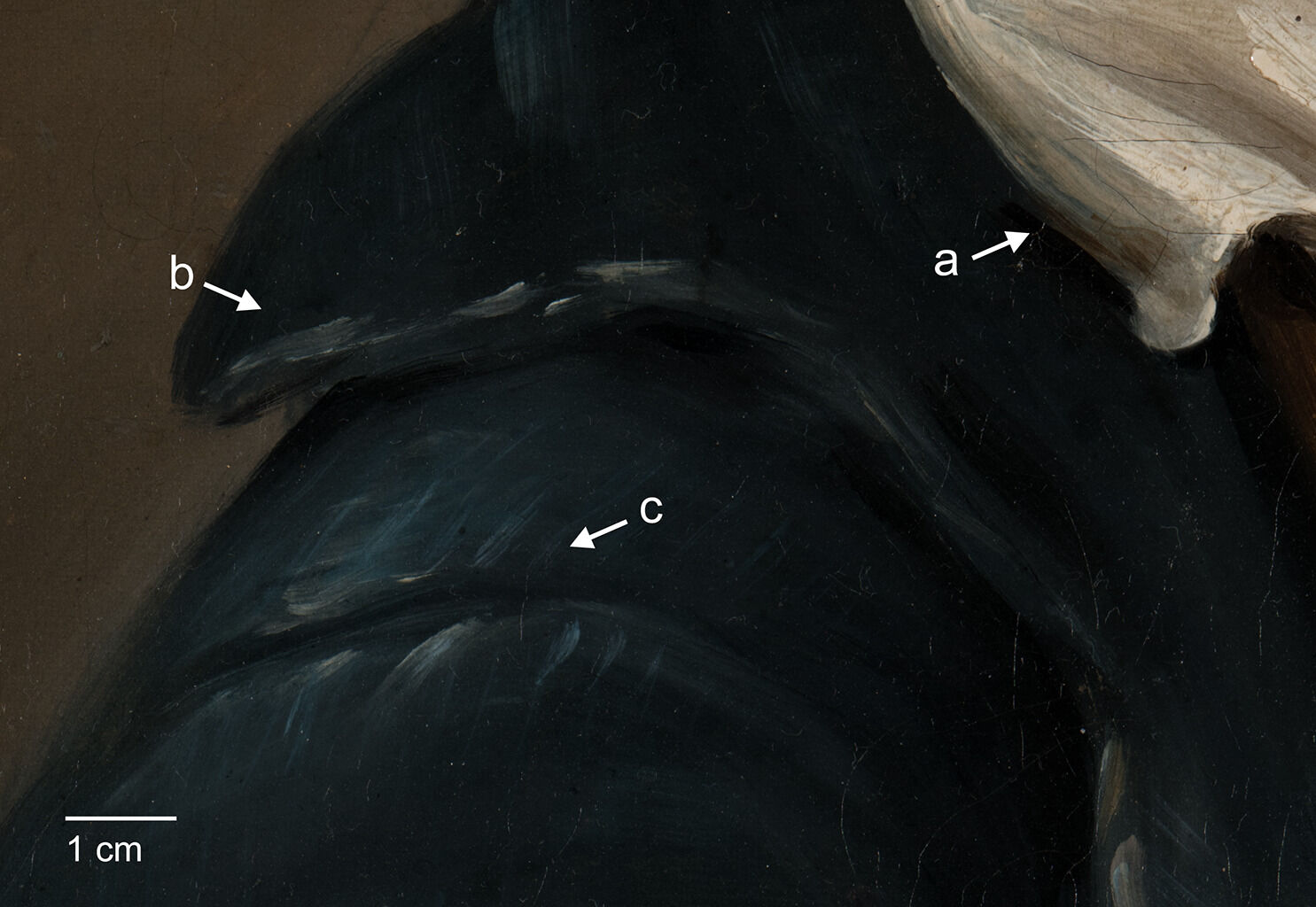

Fig. 14. Detail image showing blue reflection and shadow on the collar where it overhangs the coat (a), dashed strokes along the seam of the coat collar (b), and bright, wispy blue lines on either side of the shoulder seam (c), Portrait of a Boy (1799)

Fig. 14. Detail image showing blue reflection and shadow on the collar where it overhangs the coat (a), dashed strokes along the seam of the coat collar (b), and bright, wispy blue lines on either side of the shoulder seam (c), Portrait of a Boy (1799)

Fig. 15. Photomicrograph showing the gray ground visible between yellow brushstrokes in the vest, Portrait of a Boy (1799)

Fig. 15. Photomicrograph showing the gray ground visible between yellow brushstrokes in the vest, Portrait of a Boy (1799)

The figure’s white shirt collar picks up reflections of blue in the shadows, where it drapes over the coat (Fig. 14). Gray ground that remains exposed in the yellow vest becomes the basis for areas of shadow, augmented by brown glazes and sweeps of deep brown (Fig. 15). Deep blue-black strokes delineate folds and shadows beneath the lapel, collar, and arm of the figure’s coat. These are paired with loosely brushed lighter blues, accentuating the dimensionality of the fabric. Bright blue wispy lines suggest age and wear on either side of the shoulder seam, along the elbow of the right arm, and perpendicular to the rolled edge of the lapel. This sense of wear is intensified by short, dashed strokes of white along the seam of the collar and down the lapel (see Fig. 14). A button peeks from behind the open coat, highlighted by a precise dab of white and flicks of blue and golden brown (Fig. 16).

Fig. 16. Photomicrograph of the coat’s button, with strokes of white, bright blue, and golden-brown paint, Portrait of a Boy (1799)

Fig. 16. Photomicrograph of the coat’s button, with strokes of white, bright blue, and golden-brown paint, Portrait of a Boy (1799)

Fig. 17. Photomicrograph of the corner of the proper left collar, showing a wet-over-wet stroke smoothing the outer edge of the garment, Portrait of a Boy (1799)

Fig. 17. Photomicrograph of the corner of the proper left collar, showing a wet-over-wet stroke smoothing the outer edge of the garment, Portrait of a Boy (1799)

The artist smoothed the outer profile of the figure’s garments using a broad stroke of gray, which is especially noticeable in blended wet-over-wet passages along the proper left collar (Fig. 17) and on the left along the lower back. The same technique was used along the proper left side of the figure’s face to define the curvature of the cheek and jawline (Fig. 18). There is a heavy line of cracks in the adjacent area, possibly related to artist’s changes. The background itself is predominately based on the gray ground layer, with a scumblescumble: A thin layer of opaque or semi-opaque paint that partially covers and modifies the underlying paint. of dark grayish brown applied with energetic brushstrokes and deepening in color toward the outer and lower edges of the painting.

Fig. 18. Photomicrograph of the meeting point of the chin, neck, and background, showing the wet-over-wet stroke used to adjust the profile of the jawline, Portrait of a Boy (1799)

Fig. 18. Photomicrograph of the meeting point of the chin, neck, and background, showing the wet-over-wet stroke used to adjust the profile of the jawline, Portrait of a Boy (1799)

Fig. 19. Longwave ultraviolet (UVA)-induced visible fluorescence image, showing areas of loss that have been retouched, visible as dark areas, Portrait of a Boy (1799)

Fig. 19. Longwave ultraviolet (UVA)-induced visible fluorescence image, showing areas of loss that have been retouched, visible as dark areas, Portrait of a Boy (1799)

The painting is in generally good condition, aside from the small section of excised canvas in the lower right. Mechanical cracksmechanical cracks: Cracks, either localized or overall, that form in response to movement or stress. that have developed across the surface of the painting are dark and visually distracting in the figure’s face. Several sigmoid cracksimpact cracks: A characteristic crack pattern that forms after a blow to a painting. When these appear as circular, spiral, or spiderweb-like, they are sometimes called sigmoid cracks. resulting from impact are clustered around the proper right eye (see Fig. 9) and below the nose. Some cracking in the figure’s face has been retouched to minimize visual disruption. There are four significant losses—in the chin, the proper right side of the neck (above the collar), the proper right shoulder, and the background to the left of the figure’s head—which have been filled and retouched (Fig. 19). Small spots of discoloration throughout the background and some large areas along the bottom edge have also been retouched. Overall paint abrasionabrasion: A loss of surface material due to rubbing, scraping, frequent touching, or inexpert solvent cleaning. is the result of past overcleaning. There are two layers of synthetic varnish on the surface, which have both likely discolored over time.5James Roth, treatment report, December 1955; Scott Heffley, treatment report, November 1988; conservation file, 31-58.

Notes

-

James Roth, treatment report, December 1955, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, inv. no. 31-58. For more on Roth and conservation at the Nelson-Atkins, see Seth Adam Hindin, “How the West Was Won: Charles Muskavitch, James Roth, and the Arrival of ‘Scientific’ Art Conservation in the Western United States,” Journal of Art Historiography 11 (2014): 1–50.

-

See film-based radiographs, no. 45, NAMA conservation file, 31-58.

-

The x-ray shows the canvas to have a similar thread count to the fine weave of the original canvas (approximately 52 x 58 threads per inch); see Nathan Sutton, technical notes, May 2010, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, 31-58. When coupled with significant losses to paint and ground on the insert, it suggests the insert may have been repurposed from a piece of the original tacking margins.

-

The band measures 5 centimeters wide along the bottom edge, 4.5 centimeters on the right and left edges, and only 2.5 centimeters on the top edge.

-

James Roth, treatment report, December 1955; Scott Heffley, treatment report, November 1988; conservation file, 31-58.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Attributed to Adèle Romany, Portrait of a Boy, 1799,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.420.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Attributed to Adèle Romany, Portrait of a Boy, 1799,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.420.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Attributed to Adèle Romany, Portrait of a Boy, 1799,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.420.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Attributed to Adèle Romany, Portrait of a Boy, 1799,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.420.4033.

Possibly Ambroise Joseph Loyer (1842–1922), Paris and Bièvres, France, by February 25, 1922 [1];

Possibly inherited by his son Maurice Alexandre Marie Joseph Loyer (1869–1954), Paris and Bièvres, France, February 25, 1922–30 [2];

Purchased from Loyer by Wildenstein Gallery, New York, stock no. 1059d, June 1930–January 28, 1931 [3];

Purchased from Wildenstein by The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1931.

Notes

[1] According to correspondence from Eliot Rowlands, Wildenstein and Company, Inc., to Meghan L. Gray, May 12, 2011; and to Glynnis Napier Stevenson, April 12, 2022, NAMA curatorial files, Wildenstein purchased the painting from “M. Loyer, Bièvres.” This probably refers to Maurice Alexandre Marie Joseph Loyer (1869–1954), who may have inherited the painting from his father, Ambroise Joseph Loyer (1842–1922), an antiques dealer. The elder Loyer served as mayor of Bièvres from 1904 to 1908, and he also purchased and refurbished the château de la Martinière in 1890 (which Maurice inherited at his father’s death). In 1886, on his son’s birth certificate, Ambroise is listed as a “restaurateur de tableaux” (paintings restorer), and in 1898 as an “antiquaire” (antiques dealer). See Paris, France, Births, Marriages, and Deaths, 1555–1929, 6e arrondissement, 1869, naissances, no. 2477; and 01er arrondissement, 1898, mariages, no. 653; both digitized on Ancestry.com.

In 1905, members of the Société Historique du VIe Arrondissement de Paris toured Ambroise Loyer’s art collection. See Charles Saunier, “Le Collection de M. Loyer,” Bulletin de la Société historique du VIe arrondissement de Paris 8 (1905): 142. Saunier noted that Loyer’s collection included a portrait of a child by Greuze (“portrait d’enfant par Greuze”). Given the murky history of the attribution of the artist, it is possible Saunier is referencing Portrait of a Boy.

[2] Maurice Loyer was an antiques dealer like his father, and he was a lawyer for the Court of Appeals in Paris from at least 1898 until at least 1904. He was a devoted amateur anthropologist as well as Secretary-General of the Anthropological Society of Paris. In 1926, he was made a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor. His name can be found among the lenders in some exhibitions, including Explication des peintures, gravures, miniatures, et autres ouvrages de femmes peintres du XVIIIe siècle exposés au profit de l’Appui Maternel (Hôpital Tarnier) (an exhibition of eighteenth-century art by female painters) at Paris’s Hôtel des négociants en objets d’art, tableaux et curiosités in 1926.

In 1924, Loyer co-organized an exhibition of historic frames, to which he also lent objects. One of them seems to match the frame on the Nelson-Atkins painting when the museum acquired it from Wildenstein. See Arthur Sambon and Maurice Loyer, Exposition du Cadre Ancien du XIVe au XIXe Siècle au Profit de l’œuvre Toute l’Enfance en Plein Air, exh. cat. (Mâcon, France: Imprimerie de Protat frères, 1924), 15, under no. 60.

[3] Letter from Eliot Rowlands, Wildenstein and Company, Inc., to Meghan L. Gray, May 12, 2011, NAMA curatorial files.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Attributed to Adèle Romany, Portrait of a Boy, 1799,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.420.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Attributed to Adèle Romany, Portrait of a Boy, 1799,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.420.4033.

Sculpture by Houdon, Paintings and Drawings by David, The Century Association, New York, February 19–April 10, 1947, no. 25, erroneously as by Jacques Louis David, Portrait of a Young Boy.

D-Day Anniversary Celebration, City Manager’s Office, City Hall, Kansas City, MO, ca. June 6, 1947, erroneously as by Jacques-Louis David, Portrait of a Young Boy.

The Century of Mozart, The Nelson Gallery and Atkins Museum, Kansas City, MO, January 15–March 4, 1956, no. 22, erroneously as by Jacques Louis David, Portrait of a Boy.

The French Portrait: Revolution to Restoration, Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton, MA, September 30–December 11, 2005, no. 39, as attributed to Marie Françoise Constance Mayer La Martinière, Portrait of a Boy.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Attributed to Adèle Romany, Portrait of a Boy, 1799,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.420.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Attributed to Adèle Romany, Portrait of a Boy, 1799,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.420.4033.

Possibly Charles Saunier, “Le Collection de M. Loyer,” Bulletin de la Société historique du VIe arrondissement de Paris 8 (1905): 142, possibly as “portrait d’enfant par Greuze.”

“A Big Gallery Addition: Rembrandt and Hals Paintings to Nelson Group,” Kansas City Star 51, no. 148 (February 12, 1931): 3, erroneously as by Jacques Louis David.

“Half-Million for Art: A Rembrandt in New Purchases for Nelson Gallery,” Kansas City Star 51, no. 156 (February 20, 1931): 3, erroneously as by Jacques Louis David.

“Nelson’s Museum Gets Scores of Old Masters,” Jefferson City Post-Tribune 65, no. 350 (February 20, 1931): 2, erroneously as by David.

“Kansas City Gets $1,000,000 Art Here: William Rockhill Nelson Trust Buys Paintings by Rubens, Rembrandt, and Others; Guelph Objects Included; Treasures to be Placed in New Structure Being Built by Publisher’s Endowment,” New York Times 80, no. 26,690 (February 20, 1931): 16, erroneously as by David.

“Camera Records News Events Here and in Other Parts of the World,” Kansas City Journal-Post 77, no. 284 (March 18, 1931): 26, (repro.), erroneously as by Jacques Louis David, Portrait of a Young Boy.

“Add Seven Artworks: Group for Nelson Gallery on View at Institute,” Kansas City Star 51, no. 182 (March 18, 1931): 15, erroneously as by Jacques Louis David, Portrait of a Young Boy.

“Art,” Kansas City Times 94, no. 67 (March 19, 1931): 7, erroneously as by Jacques Louis David, Portrait of a Young Boy.

“More Works of Art Purchased for the Nelson Gallery of Art,” Kansas City Star 51, no. 186 (March 22, 1931): unpaginated, (repro.), erroneously as by Jacques Louis David, Portrait of a Young Boy.

“Parsons Makes More Purchases for Kansas City,” Art News 29, no. 26 (March 28, 1931): 3, (repro.), erroneously as by Jacques Louis David, Portrait of a Boy in a Blue Jacket.

“He Married the Cook and Painted No More,” Art Digest 5, no. 15 (May 1, 1931): 6, erroneously as by Jacques Louis David, Portrait of a Young Boy.

“What to See In Kansas City: A Guide to Principal Points of Interest Presented in the Style of A Baedeker,” Kansas City Star 52, no. 101 (December 27, 1931): 3C, as Portrait of a Young Boy.

“Treasure in Lore of Art: ‘Read,’ says Parsons to Those Who Would Appreciate Works,” Kansas City Times 95, no. 10 (January 12, 1932): 2, erroneously as by Jacques Louis David.

“Nelson Art Treasures Draw Admiring Throng: Thousands Flock to Temporary Exhibition of Paintings at the Kansas City Art Institute Every Day,” Weekly Kansas City Star 42, no. 48 (January 27, 1932): 4, erroneously as by Jacques Louis David.

“M. Claudel in Rich Land: A Desire to See Harvest Expressed by Ambassador,” Kansas City Times 95, no. 70 (March 22, 1932): 11, erroneously as by Jacques Louis David.

“Nelson Gallery of Art Special Number,” Art Digest 8, no. 5 (December 1, 1933): 13, 21, erroneously as by Jacques Louis David, Portrait of a Young Boy.

“Complete Catalogue of Paintings and Drawings,” Art News 32, no. 10 (December 9, 1933): 28, erroneously as by Jacques Louis David, Portrait of a Young Boy.

Alfred M. Frankfurter, “Paintings in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art,” Art News 32, no. 10 (December 9, 1933): 30, 44, (repro.), erroneously as by Jacques Louis David, Portrait of a Young Boy.

Minna K. Powell, “The First Exhibition of the Great Art Treasures: Paintings and Sculpture, Tapestries and Panels, Period Rooms and Beautiful Galleries Are Revealed in the Collections Now Housed in the Nelson-Atkins Museum,” Kansas City Star 54, no. 84 (December 10, 1933): 4C, erroneously as by Jacques Louis David, Portrait of a Young Boy.

“Nelson Gallery of Art Opened at Kansas City: $14,000,000 Gift of ‘Star’ Publisher and His Heirs Already Fully Furnished; Has Many Innovations; Oriental, Roman, Colonial Objects World Famous,” New York Herald Tribune 93, no. 31,802 (December 11, 1933): 12, erroneously as by Jacques Louis David.

Luigi Vaiani, “Art Dream Becomes Reality with Official Gallery Opening at Hand: Critic Views Wide Collection of Beauty as Public Prepares to Pay its First Visit to Museum,” Kansas City Journal-Post 80, no. 187 (December 11, 1933): 7, erroneously as by Jacques Louis David.

“Praises the Gallery: Dr. Nelson M’Cleary, Noted Artist, a Visitor,” Kansas City Star 54, no. 98 (December 24, 1933): 9A, erroneously as by Jacques Louis David, Portrait of a Boy.

The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Handbook of the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Art, 1933), 41, 48, (repro.), erroneously as by Jacques Louis David, Portrait of a Young Boy.

A. J. Philpott, “Kansas City Now in Art Center Class: Nelson Gallery, Just Opened, Contains Remarkable Collection of Paintings, Both Foreign and American,” Boston Sunday Globe 125, no. 14 (January 14, 1934): 16, erroneously as by Jacques Louis David.

“One of the most important purchases,” Musical Bulletin 24, no. 6 (March 1936): 11, erroneously as by Jacques Louis David, Young Boy.

The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, The William Rockhill Nelson Collection, 2nd ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1941), 168, as Portrait of a Young Boy.

“Loans to Other Museums,” Gallery News (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) 13, no. 7 (April 1947): unpaginated, erroneously as by Jacques Louis David, Portrait of a Young Boy.

“To Mark D-Day: French Paintings are Shown,” Kansas City Times 110, no. 122 (June 6, 1947): 1, erroneously as by Jacques-Louis David, Portrait of a Young Boy.

Sculpture by Houdon, Paintings and Drawings by David, exh. cat. (New York: Century Association, 1947), unpaginated, (repro.), erroneously as by Jacques Louis David, Portrait of a Young Boy.

French XVIIIth Century Paintings, exh. cat. (New York: Wildenstein, 1948), unpaginated, erroneously as by Jacques Louis David, Portrait of a Young Boy.

“The Century of Mozart: January 15 through March 4, 1956,” exh. cat., special issue, Bulletin (The Nelson Gallery and Atkins Museum) 1, no. 1 (January 1956): 26, erroneously as by Jacques Louis David, Portrait of a Boy.

Ross E. Taggart, ed., Handbook of the Collections in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 4th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1959), 117, (repro.), erroneously as by Jacques Louis David, Portrait of a Young Boy.

Maurice Grosser, “Art,” Nation 191 (July 9, 1960): 38 [repr. Maurice Grosser, Critic’s Eye (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1962), 181], erroneously as by Jacques Louis David.

Robert K. Sanford, “Two Books—Photos and Criticism,” Kansas City Star 82, no. 273 (June 17, 1962): 10E.

Georges Wildenstein, David (Paris: Les Beaux-Arts, 1963), pp. 104, 242, no. 133, erroneously as by Jacques Louis David, Portrait d’enfant (Jeune Créole?) [not officially published; available here https://view.publitas.com/wildenstein-plattner-institute-ol46yv9z6qv6/c-r_louis_david_wildenstein_institute_not_published/page/10-11].

John J. Doohan, “Forty Years Ago,” Kansas City Times 103, no. 165 (March 18, 1971): 14D.

Donald Hoffmann, “The Nelson Gallery 40 Years (and More) Seeking Beauty,” Kansas City Star 94, no. 83 (December 9, 1973): 4E, erroneously as by Jacques Louis David, Young Boy.

Ross E. Taggart and George L. McKenna, eds., Handbook of the Collections in The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Kansas City, Missouri, vol. 1, Art of the Occident, 5th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1973), 258, erroneously as by Jacques Louis David, Portrait of a Young Boy.

Donald Hoffmann, “Throwing Suspicion on the Masters: Nelson’s Curator Reassesses Status, Authenticity of Art,” Kansas City Star 107, no. 263 (July 26, 1987): 1D, 6D, (repro.), as Portrait of a Young Boy.

Margaret A. Oppenheimer, The French Portrait: Revolution to Restoration, exh. cat. (Northampton, MA: Smith College Museum of Art, 2005), 154–57, 219, (repro.), as attributed to Marie Françoise Constance Mayer La Martinière, Portrait of a Boy.

MacKenzie Mallon, “Laying the Foundation: Harold Woodbury Parson and the Making of an American Museum,” in Art Markets, Agents, and Collectors: Collecting Strategies in Europe and the United States, 1550–1950, ed. Susan Bracken and Adriana Turpin (New York: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2021), 310, as by David.