![]()

Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, Portrait of Joachim Lebreton, 1795

| Artist | Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, French, 1749–1803 |

| Title | Portrait of Joachim Lebreton |

| Object Date | 1795 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (Unframed) | 28 3/4 x 23 1/2 in. (73.0 x 59.7 cm) |

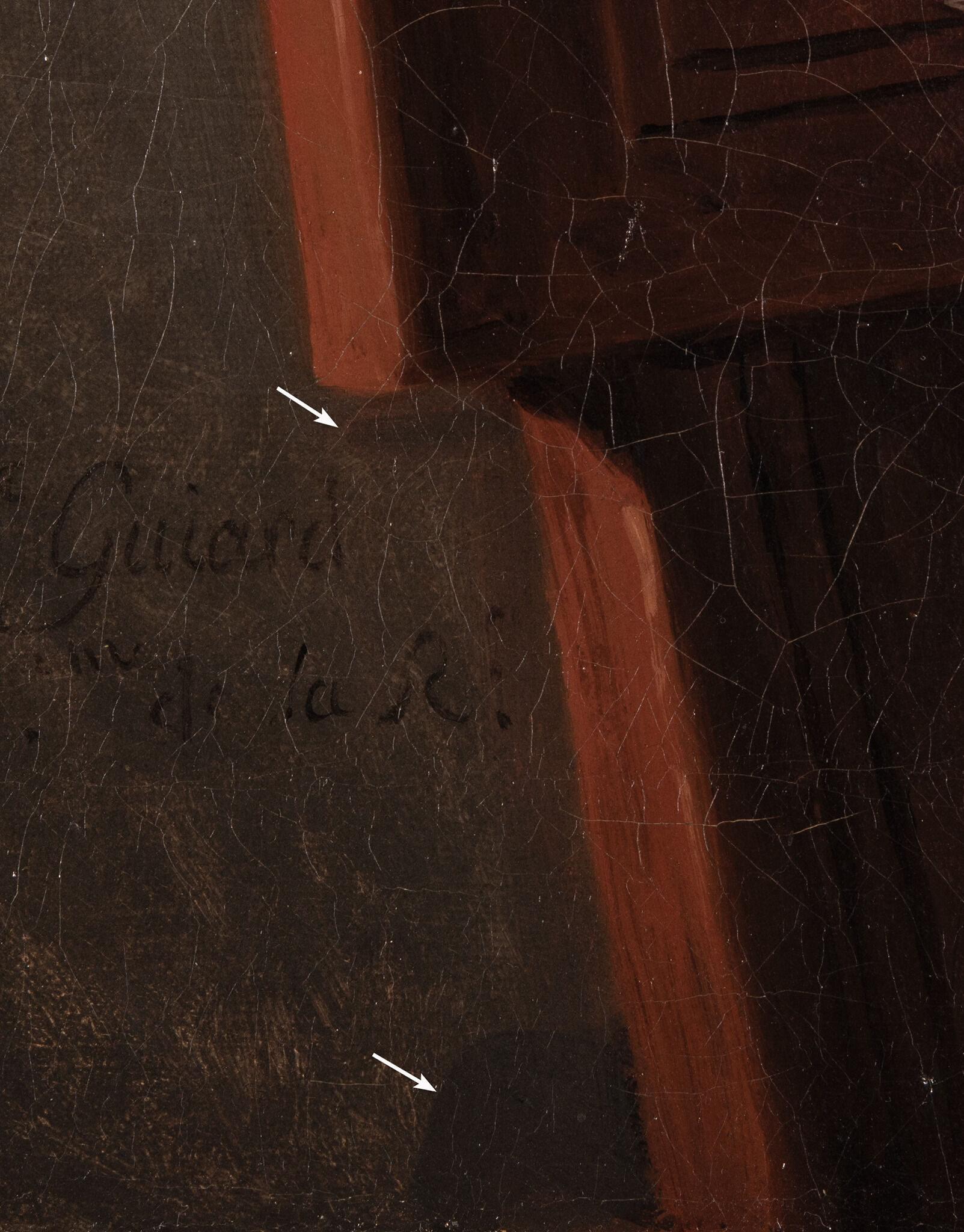

| Signature | Signed lower left, recto: Labille d.tte Guiard /l’an 3.eme de la R: |

| Inscription | Inscribed upper half of canvas verso: Md G / 20 |

| Credit Line | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust through the George H. and Elizabeth O. Davis Fund and the exchange of the bequests of Ethlyne Jackson Seligman and William Rockhill Nelson, the gifts of Robert L. Bloch and Kenneth Baum, and other Trust properties, 94-34 |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Laura Auricchio, “Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, Portrait of Joachim Lebreton, 1795,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.416.5407.

MLA:

Auricchio, Laura. “Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, Portrait of Joachim Lebreton, 1795,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.416.5407.

This half-length portrait of Joachim Lebreton exemplifies the intimate yet elegant style of portraiture that Adélaïde Labille-Guiard developed in the aftermath of the French Revolution’s Reign of TerrorReign of Terror: A period of the French Revolution that lasted from March 1793 until July 1794. The Revolutionary government, known as the Convention, executed the king, and then set about attacking and executing opponents and anyone else considered a threat to the regime. The Reign of Terror is associated with the Jacobin consolidation of power in the National Convention under their leader Maximilien Robespierre. It ended with his downfall and execution on 9-10 Thermidor (July 27) in the summer of 1794, although spurts of violence and executions continued throughout the Revolution. (1793–94). Unlike Labille-Guiard’s most accomplished paintings of the 1780s, which portray their sitters in elaborate spaces that revel in illusionism and abound with markers of status and identity (Fig. 1), her portraits of the late 1790s emphasize naturalism over artifice and establish a less formal relationship between sitter and viewer (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1. Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, Portrait of Marie-Adelaide de France, called Madame Adélaïde, 1787, oil on canvas, 106 11/16 x 76 3/4 in. (271 x 195 cm), Musée national des châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon, Versailles

Fig. 1. Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, Portrait of Marie-Adelaide de France, called Madame Adélaïde, 1787, oil on canvas, 106 11/16 x 76 3/4 in. (271 x 195 cm), Musée national des châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon, Versailles

Fig. 2. Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, Portrait of the Comedian Tournelle, Called Dublin, 1799, oil on canvas, 28 1/8 × 22 1/2 in. (71.4 × 57.2 cm), Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge, MA

Fig. 2. Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, Portrait of the Comedian Tournelle, Called Dublin, 1799, oil on canvas, 28 1/8 × 22 1/2 in. (71.4 × 57.2 cm), Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge, MA

Lebreton appears in three-quarters view, with the right side of his body leaning against the back of the chair. His bent right elbow juts out behind him; his right hand rests nonchalantly on his left forearm; and his left hand grips the top of the rectangular backrest. Turning his face toward the picture plane, he gazes softly ahead and to the left, at a point beyond our view, while the corners of his closed mouth rise in the stirrings of a smile, giving him a welcoming air.

Labille-Guiard depicts Lebreton in the stylishly relaxed fashions that reigned in Paris in the mid-1790s. The flowing waves and flyaway wisps of his shoulder-length brown hair echo the suppleness of his generously cut brown redingote—a double-breasted coat with wide, flat lapels, inspired by the English riding coat in both appearance and name. The coat depicted here—which features a tall, unstructured collar and a wide, loosely draped lapel that spills onto Lebreton’s sleeve—is worn open, revealing a shimmering silk vest in a bold pattern of diagonal red-and-black stripes. A narrow gold ring gleams on the little finger of his left hand, adding a note of understated luxury.

The daughter of a mercer, Labille-Guiard grew up amid fabrics and fashion and excelled at capturing the look and feel of materials.1On Labille-Guiard’s biography and career, see Laura Auricchio, Adélaïde Labille-Guiard: Artist in the Age of Revolution (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2009); Anne-Marie Passez, Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, 1749-1803: Biographie et Catalogue raisonné de son œuvre (Paris: Arts et Métiers Graphiques, 1973); and Roger Portalis, Adélaïde Labille-Guiard (1749–1803) (Paris: Imprimerie Georges Petit, 1902). Technical analysis of Portrait of Joachim Lebreton reveals some of the methods that she employed to foster this verisimilitude.2Technical notes by Mary Schafer, NAMA paintings conservator, May 24, 2011, NAMA conservation file, 94-34. For instance, on a canvas that is otherwise thinly painted, subtle passages of impasto applied to the cuffs, the cravat, and the edges of the lapel foster an illusion of comparative stiffness in these areas. Near the sitter’s right shoulder, the red and black of the vest are visible through an overlaid triangle of translucent linen, an effect created by painting wet-into-wetwet-into-wet: An oil painting technique which involves blending of colors on the picture surface., whereas dry brushwork was used to generate feathery effects in the sitter’s hair. Dabs of transparent, bright magenta paint add glints of light to Lebreton’s silk vest and suggest lifelike notes of moisture on his lips and nose.

The unusual signature and date visible at the lower left of the painting—“Labille d.tte Guiard / l’an 3.eme de la R”—situate the work specifically in the life of both the artist and the nation. The signature refers to the artist’s marital history: Adélaïde Labille married Nicolas Guiard in 1769 and began signing her paintings “Labille wife [femme] of Guiard,” but after her 1793 divorce, she adopted the signature “Labille called [dite] Guiard.” The date—“year 3 of the Republic”—refers to the new calendar adopted in 1793 by the National Convention, which started with September 22, 1792 (when France was declared a republic); “year 3” ran from September 22, 1794 through September 21, 1795.

Portrait of Joachim Lebreton is one of at least six portraits that Labille-Guiard sent to the SalonSalon, the: Exhibitions organized by the French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture (Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture) and its successor the Academy of Fine Arts (Académie des Beaux Arts), which took place in Paris from 1667 onward. exhibition that opened on October 2, 1795.3The published guide to the Salon of 1795 lists four paintings by Labille-Guiard in addition to “Plusieurs Portraits sous le même numéro” (Several Portraits under the same number); see Jean-François Heim, Claire Béraud, and Philippe Heim, Les Salons de peinture de la Révolution française, 1789–1799 (Paris: C.A.C. Sarl. ÉDITION, 1989), 248. This was the first exhibition in which Labille-Guiard had participated since 1791. Having been elected to the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture in 1783, Labille-Guiard went on to attract the patronage of several members of the royal family in the final years of the ancien régimeancien régime: The period in French history from about 1650 to 1789 (before the French Revolution). It was characterized by a divine-right absolute monarchy, a society based upon privileges for the rich and well-connected, and the Catholic Church as the religious establishment. The monarchy fell on August 10, 1792, after months of royal intransigence, and the Revolution entered a new more radical phase. King Louis XVI was executed in January 1793., attaining the status of “Painter to Mesdames” (the unmarried aunts of Louis XVI) and receiving major commissions from two of them, Madame Adélaïde and Madame Victoire; their niece, Madame Élisabeth (the king’s sister); the comte de Provence (a brother of the king); and even Louis XVI himself.4The academy had admitted female artists in small numbers since the seventeenth century, although no more than four women were permitted to be members at any one time. On the uneasy relationship between women and the academy, see Mary D. Sheriff, The Exceptional Woman: Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun and the Cultural Politics of Art (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), 73–104. For a more general history of women in the academy, see Octave Fidière, Les Femmes artistes a [sic] l’académie royale de peinture et de sculpture (Paris: Charavay Frères, 1885). During the revolution, she advocated for moderate reforms in the academy and in the nation, arousing the ire of her more radical colleagues. She survived the Reign of Terror, in part, by moving to the countryside on the eastern outskirts of Paris, but several of her paintings depicting members of the royal family were destroyed in public bonfires in 1793 by order of the Paris city government.5According to a report delivered to the Committee on Public Instruction on 13 Floréal Year III (May 2, 1795), “the Director of the Department of Paris, by an order of August 11, 1793, forced citoyenne Guiard to deliver to the procureur syndic the large and small portraits of the former prince and all the studies related to these works, to be devoured by flames.” Pierre-Louis Ginguené, “Rapport au Comité d’instruction publique,” 13 Floréal an III (May 2, 1795), Archives Nationales, Paris, DXXXVIII/4.

The nation’s art institutions were also in the midst of reinvention in 1795, with Joachim Lebreton playing an important role in the process. Born in Saint-Méen-le-Grand, Brittany, in 1760, Lebreton moved in 1772 to Paris, where he was educated and ordained by the brothers of the Theatine Order.6For the most current biography of Joachim Lebreton, see Elaine Dias, “Lebreton, Joachim,” in Dictionnaire critique des historiens de l’art actifs en France de la Révolution à la Première Guerre mondiale (Paris: L’institut national de l’histoire de l’art, 2009), online at http://www.inha.fr/spip.php?article2403. See also Henry Jouin, Joachim Lebreton, premier secrétaire perpétuel de l’Académie des beaux-arts (Paris: Bureaux de l’Artiste, 1892). The Theatine Order was an order of secular clergy founded in Rome and approved by Clement VII in 1524. Members of the Order were required to take a vow of poverty and obedience, but didn’t have to attend multiple masses day and night. They wore simple black cassocks and nursed the needy and sick in their communities. Due to their lack of evangelizing zeal, the Order was waning by the 18th century and now they exist only in their original country, Italy. See Deborah Howard, “Theatine Order,” Grove Art Online (2003): http://doi.org/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T084340. In his position teaching at the College de Tulle, which was overseen by the Theatins from 1764 to 1791, Lebreton was friends with several other men of letters who would go on to have careers during the Revolution and successive regimes. See Marcel Dorigny, “Victor Lanneau, Prêtre, Jacobin et Fondateur du Collège des Sciences et des Arts (1758–1830),” Annales Historiques de La Révolution Française, no. 274 (October–December 1988): 347–65. In 1779, he obtained a post teaching rhetoric in a Theatine school in Tulle, in the Limousin region of south-central France. As Father Lebreton, he published his first book, La logique adaptée à la rhétorique, in 1788.7The censor’s approval refers to the author as “le P. Le Breton,” “P.” being an abbreviation for “Père.” P. Le Br. Clerc-Régulier Théatin, La Logique adaptée a [sic] la rhétorique (Paris: Jean-Louis Pichard, 1788), 141. At the outbreak of revolution in 1789, Lebreton left the order and returned to Paris. In 1794, he married Anne-Julie d’Arcet, the eldest daughter of the chemist Jean d’Arcet.8When the Portrait of Joachim Lebreton first went on the market, its sitter was misidentified as Lebreton’s father-in-law, Jean d’Arcet. See Tableaux Anciens et du XIXème Siècle (Monte Carlo:, Christie’s Monaco S.A.M., December 4, 1993), 38–39. Joachim Lebreton and Anne-Julie d’Arcet wed on June 7, 1794. See Anne-Julie d’Arcet, “4.44. Las de Julie Darcet à son frère J.P.J. Darcet, à Sainte-Palaye, 3 p. De son mariage le 7 juin avec Le Breton,” 16 prairial an II (June 4, 1794), Institut de France, Académie des sciences, Paris, collection d’Arcet, 47 J, folder 4. When Labille-Guiard exhibited his portrait, Lebreton was serving as head of the museum department of the Committee of Public Instruction and was an important contributor to the journal La Décade philosophique, littéraire et politique. He would soon be named head of the Ministry of the Interior’s Bureau of Fine Arts and a founding member of the newly created National Institute of Arts and Sciences, which replaced the old regime’s system of royal academies. Lebreton served as the first secretary of the Class of Moral and Political Sciences and, after an 1803 reorganization of the institute, he was appointed “Perpetual Secretary” of the Class of Fine Arts. Unlike the defunct Royal Academy, the National Institute permitted no female members.

With support from Lebreton and other administrators whose patronage Labille-Guiard cultivated, she began rebuilding her shattered career. In May 1795, the Committee of Public Instruction awarded Labille-Guiard two thousand livres as a measure of compensation for the destruction of her paintings, and in September of the same year the National Convention also granted her a prize. She exhibited several oil portraits at the Salon exhibitions of 1795, 1798, and 1799, yet she never regained the stature that she enjoyed before the revolution. When Labille-Guiard died in 1803, Lebreton eulogized her in an eight-page published “Notice” that summarized her life, her career, and her character, furnishing the basis for all subsequent biographies of the artist.9Joachim Lebreton, “Nécrologie: Notice sur Madame Guyard [sic],” Magasin encyclopedique [sic], ou Journal des science, des lettres et des arts 9, no. 1 (1803): 405–14. Lebreton did the same after the deaths of several other artists and intellectuals; see, for example, Joachim Le Breton [sic], Notice Historique sur la vie et les ouvrages de Pierre Julien, Statuaire, de l’ancienne Académie royale de peinture et sculpture, membre de l’Institut national et de la Légion d’honneur (Paris: Baudouin, 1805).

Lebreton’s career also waxed and waned with the vagaries of political circumstance. During the Napoleonic era (1799–1815), Lebreton was a central actor in the articulation and implementation of national arts policies.10See, for example, Udolpho van de Sandt, ed., Rapports à l’Empereur sur le progrès des sciences, des lettres et des arts depuis 1789, vol. 5, Beaux-arts par Joachim Le Breton (Paris: Belin, 1989). In recognition of his service, he was honored with the title of Chevalier of the Legion of Honor in 1803. A vocal opponent of repatriating the antiquities seized by French Army expeditions, Lebreton was removed from his post at the National Institute after Napoleon’s fall.11Indeed, Lebreton made a direct jab at the British when he asserted, “It was not the French who ripped off the sculptures of Phidias” (referring to the Parthenon sculptures, known as the “Elgin Marbles”). This stance made him some enemies. See Maria Teresa Caracciolo and Gennaro Toscano, eds., Jean-Baptiste Wicar et son temps, 1762–1834 (Villeneuve d’Ascq: Presses Universitaires du Septentrion, 2007), 90. At the invitation of John VI, King of Portugal (1767–1826), Lebreton relocated to Brazil with the intention of establishing a school of fine arts modeled on the French system. Lebreton died in Rio de Janeiro in 1819.12See Afonso De Escragnolle Taunay, A Missão Artística de 1816 (Rio de Janeiro: Ministério da Educação e Cultura, 1956), 53–71. Joachim Lebreton brought approximately sixty paintings with him to Brazil; these pictures remain to this day in the Museu Nacional de Belas Artes de Rio. See Panzanelli and Monica Preti-Hamard, eds., La circulation des œuvres d’art: The Circulation of Works of Art in the Revolutionary Era, 1789–1848 (Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2007), 275. Although he did not live to see his project realized, he is acclaimed as a founding father of Brazilian art education.13See Elaine Dias, “Correspondências entre Joachim Le Breton e a corte portuguesa na Europa: O nascimento da Missão Artística de 1816,” Anais do Museu Paulista: História e Cultura Material 14, no. 2 (July–December 2006): 301–13.

Notes

-

On Labille-Guiard’s biography and career, see Laura Auricchio, Adélaïde Labille-Guiard: Artist in the Age of Revolution (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2009); Anne-Marie Passez, Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, 1749–1803: Biographie et Catalogue raisonné de son œuvre (Paris: Arts et Métiers Graphiques, 1973); and Roger Portalis, Adélaïde Labille-Guiard (1749–1803) (Paris: Imprimerie Georges Petit, 1902).

-

Technical notes by Mary Schafer, NAMA paintings conservator, May 24, 2011, NAMA conservation file, 94-34.

-

The published guide to the Salon of 1795 lists four paintings by Labille-Guiard in addition to “Plusieurs Portraits sous le même numéro” (Several Portraits under the same number); see Jean-François Heim, Claire Béraud, and Philippe Heim, Les Salons de peinture de la Révolution française, 1789–1799 (Paris: C.A.C. Sarl. ÉDITION, 1989), 248.

-

The academy had admitted female artists in small numbers since the seventeenth century, although no more than four women were permitted to be members at any one time. On the uneasy relationship between women and the academy, see Mary D. Sheriff, The Exceptional Woman: Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun and the Cultural Politics of Art (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), 73–104. For a more general history of women in the academy, see Octave Fidière, Les Femmes artistes a [sic] l’académie royale de peinture et de sculpture (Paris: Charavay Frères, 1885).

-

According to a report delivered to the Committee on Public Instruction on 13 Floréal Year III (May 2, 1795), “the Director of the Department of Paris, by an order of August 11, 1793, forced citoyenne Guiard to deliver to the procureur syndic the large and small portraits of the former prince and all the studies related to these works, to be devoured by flames.” Pierre-Louis Ginguené, “Rapport au Comité d’instruction publique,” 13 Floréal an III (May 2, 1795), Archives Nationales, Paris, DXXXVIII/4.

-

For the most current biography of Joachim Lebreton, see Elaine Dias, “Lebreton, Joachim,” in Dictionnaire critique des historiens de l’art actifs en France de la Révolution à la Première Guerre mondiale (Paris: L’institut national de l’histoire de l’art, 2009), online at http://www.inha.fr/spip.php?article2403. See also Henry Jouin, Joachim Lebreton, premier secrétaire perpétuel de l’Académie des beaux-arts (Paris: Bureaux de l’Artiste, 1892).

The Theatine Order was an order of secular clergy founded in Rome and approved by Clement VII in 1524. Members of the Order were required to take a vow of poverty and obedience, but didn’t have to attend multiple masses day and night. They wore simple black cassocks and nursed the needy and sick in their communities. Due to their lack of evangelizing zeal, the Order was waning by the 18th century and now they exist only in their original country, Italy. See Deborah Howard, “Theatine Order,” Grove Art Online (2003): http://doi.org/10.1093/gao/9781884446054. article.T084340 In his position teaching at the College de Tulle, which was overseen by the Theatins from 1764 to 1791, Lebreton was friends with several other men of letters who would go on to have careers during the Revolution and successive regimes. See Marcel Dorigny, “Victor Lanneau, Prêtre, Jacobin et Fondateur du Collège des Sciences et des Arts (1758–1830),” Annales Historiques de La Révolution Française, no. 274 (October–December 1988): 347–65.

-

The censor’s approval refers to the author as “le P. Le Breton,” “P.” being an abbreviation for “Père.” P. Le Br. Clerc-Régulier Théatin, La Logique adaptée a [sic] la rhétorique (Paris: Jean-Louis Pichard, 1788), 141.

-

When the Portrait of Joachim Lebreton first went on the market, its sitter was misidentified as Lebreton’s father-in-law, Jean d’Arcet. See Tableaux Anciens et du XIXème Siècle (Monte Carlo:, Christie’s Monaco S.A.M., December 4, 1993), 38–39. Joachim Lebreton and Anne-Julie d’Arcet wed on June 7, 1794. See Anne-Julie d’Arcet, “4.44. Las de Julie Darcet à son frère J.P.J. Darcet, à Sainte-Palaye, 3 p. De son mariage le 7 juin avec Le Breton,” 16 prairial an II (June 4, 1794), Institut de France, Académie des sciences, Paris, collection d’Arcet, 47 J, folder 4.

-

Joachim Lebreton, “Nécrologie: Notice sur Madame Guyard [sic],” Magasin encyclopedique [sic], ou Journal des science, des lettres et des arts 9, no. 1 (1803): 405–14. Lebreton did the same after the deaths of several other artists and intellectuals; see, for example, Joachim Le Breton [sic], Notice Historique sur la vie et les ouvrages de Pierre Julien, Statuaire, de l’ancienne Académie royale de peinture et sculpture, membre de l’Institut national et de la Légion d’honneur (Paris: Baudouin, 1805).

-

See, for example, Udolpho van de Sandt, ed., Rapports à l’Empereur sur le progrès des sciences, des lettres et des arts depuis 1789, vol. 5, Beaux-arts par Joachim Lebreton (Paris: Belin, 1989).

-

Indeed, Lebreton made a direct jab at the British when he asserted, “It was not the French who ripped off the sculptures of Phidias” (referring to the Parthenon sculptures, known as the “Elgin Marbles”). This stance made him some enemies. See Maria Teresa Caracciolo and Gennaro Toscano, eds., Jean-Baptiste Wicar et son temps, 1762–1834 (Villeneuve d’Ascq: Presses Universitaires du Septentrion, 2007), 90.

-

See Afonso De Escragnolle Taunay, A Missão Artística de 1816 (Rio de Janeiro: Ministério da Educação e Cultura, 1956), 53–71. Joachim Lebreton brought approximately sixty paintings with him to Brazil; these pictures remain to this day in the Museu Nacional de Belas Artes de Rio. See Panzanelli and Monica Preti-Hamard, eds., La circulation des œuvres d’art: The Circulation of Works of Art in the Revolutionary Era, 1789–1848 (Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2007), 275.

-

See Elaine Dias, “Correspondências entre Joachim Le Breton e a corte portuguesa na Europa: O nascimento da Missão Artística de 1816,” Anais do Museu Paulista: História e Cultura Material 14, no. 2 (July–December 2006): 301–13.

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Mary Schafer, “Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, Portrait of Joachim Lebreton, 1795,” technical entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.416.2088.

MLA:

Schafer, Mary. “Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, Portrait of Joachim Lebreton, 1795,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.416.2088.

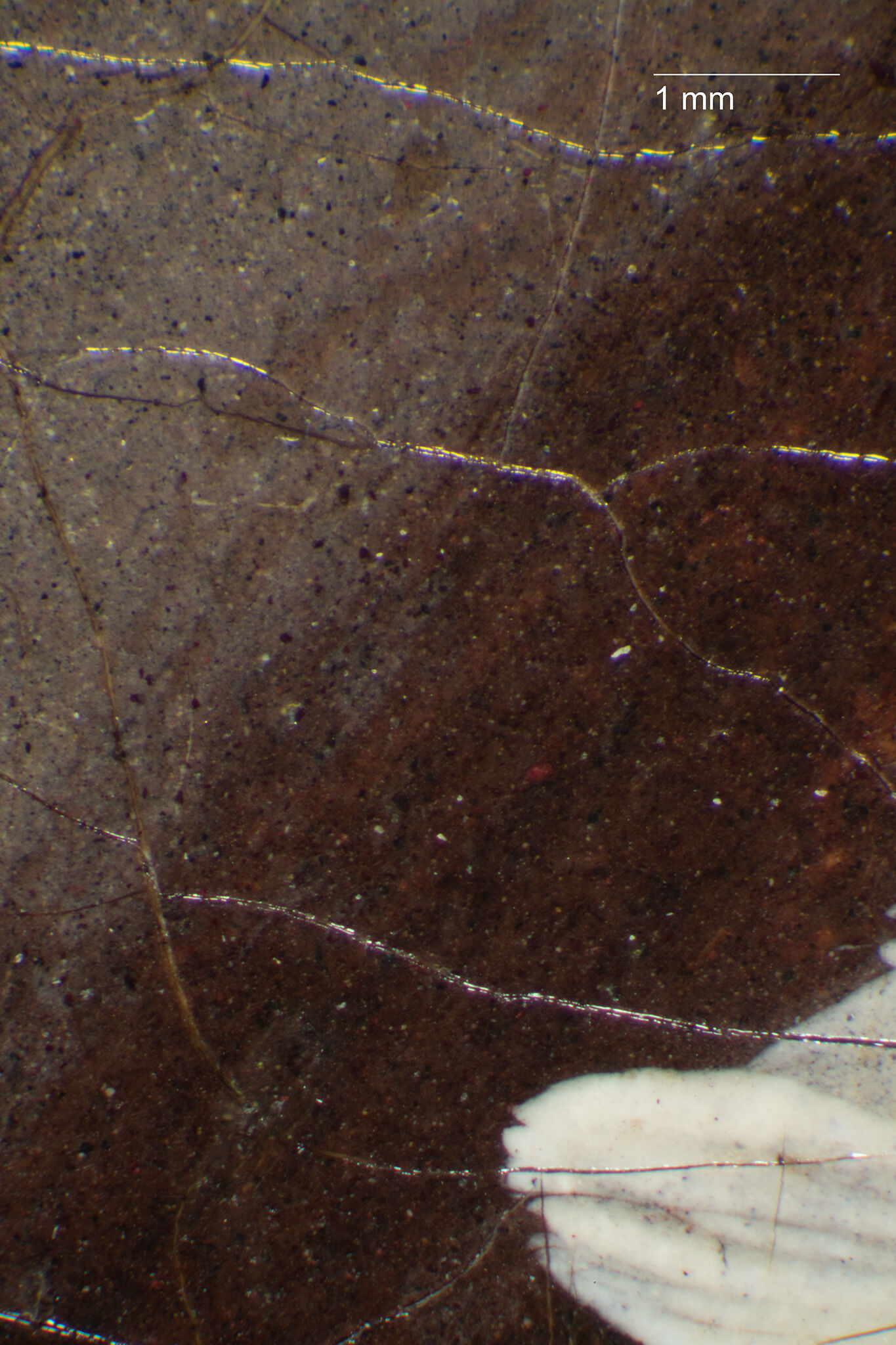

Portrait of Joachim Lebreton, completed in 1795 by Adélaïde Labille-Guiard (1749–1803), was quickly executed with loose, confident strokes and wet-over-wetwet-over-wet: An oil painting technique which involves drawing a stroke of one color across the wet paint of another color. brushwork. The somewhat open, plain-weaveplain weave: A basic textile weave in which one weft thread alternates over and under the warp threads. Often this structure consists of one thread in each direction, but threads can be doubled (basket weave) or tripled to create more complex plain weave. Plain weave is sometimes called tabby weave. canvas contains numerous slubs and weave irregularities, and a selvedgeselvedge: The original woven edge of fabric formed by the weft threads looping over the warp during the loom weaving process. The selvedge runs the length of the fabric bolt, parallel to the warp threads, and forms a finished edge. is present on the right tacking margintacking margins: The outer edges of canvas that wrap around and are attached to the stretcher or strainer with tacks or staples. See also tacking edge.. The ground layerground layer: An opaque preparatory layer applied to the support, either commercially or by the artist, to prevent absorption of the paint into the canvas or panel. See also priming layer. appears to be off-white in color, and its application is thin enough to allow the canvas texture to remain somewhat visible. Paint from the picture planepicture plane: The two-dimensional surface where the artist applies paint. does not continue onto the preserved tacking margins, confirming that the dimensions of the portrait are original.

Subsequent applications of paint were thinly applied, forming only a small amount of low impastoimpasto: A thick application of paint, often creating texture such as peaks and ridges. in the highlights of the white collar and cuff (Fig. 3). The sitter’s expressive face was constructed using opaque layers of peach, pink, pale yellow, and beige in the highlights, while shades of gray and brown define the mid-tones and shadows. The subtle transitions between light and shade create volume and effectively model the face, even as the artist’s brushwork remains prominent (Fig. 4). With a fine-tipped brush and precisely placed strokes, Labille-Guiard portrayed the reflections and glistening appearance of the sitter’s eyes (Fig. 5).1A similar technique is described in the rendering of Portrait of the Comedian Tournelle, Called Dublin (Fig. 2), in which “‘pinpoint’ touches of paint highlight the eyes.” See Andrew K. Kagan, “A Fogg ‘David’ Reattributed to Madame Adélaide Labille-Guiard,” Acquisitions (Fogg Art Museum) (Cambridge, MA: Fogg Art Museum, 1969–1970), 32. Touches of transparent magenta, most likely a red lake, are apparent in the lower layers of the nostrils and lips. While a bright, opaque pink highlights the tip of the nose (proper left side), cool blue accents are present below the nose and proper right fingernail (Figs. 4, 6).

Fig. 4. Detail of the sitter’s face, Portrait of Joachim Lebreton (1795)

Fig. 4. Detail of the sitter’s face, Portrait of Joachim Lebreton (1795)

Fig. 5. Detail of the sitter’s proper left eye, Portrait of Joachim Lebreton (1795)

Fig. 5. Detail of the sitter’s proper left eye, Portrait of Joachim Lebreton (1795)

Fig. 6. Detail of the sitter’s forefinger, Portrait of Joachim Lebreton (1795)

Fig. 6. Detail of the sitter’s forefinger, Portrait of Joachim Lebreton (1795)

Fig. 7. Photomicrograph of Portrait of Joachim Lebreton (1795), showing the wet-over-wet brushwork used to construct the vest collar

Fig. 7. Photomicrograph of Portrait of Joachim Lebreton (1795), showing the wet-over-wet brushwork used to construct the vest collar

Fig. 8. Photomicrograph with raking illumination of Portrait of Joachim Lebreton (1795), revealing the wet-over-wet brushwork of the cravat’s decorative edge

Fig. 8. Photomicrograph with raking illumination of Portrait of Joachim Lebreton (1795), revealing the wet-over-wet brushwork of the cravat’s decorative edge

Fig. 9. Detail of the cravat, Portrait of Joachim Lebreton (1795)

Fig. 9. Detail of the cravat, Portrait of Joachim Lebreton (1795)

Fig. 10. Photomicrograph of the sitter’s collar, Portrait of Joachim Lebreton (1795)

Fig. 10. Photomicrograph of the sitter’s collar, Portrait of Joachim Lebreton (1795)

Fig. 11. Photomicrograph of Portrait of Joachim Lebreton (1795), showing the gray background paint that covers the brown coat

Fig. 11. Photomicrograph of Portrait of Joachim Lebreton (1795), showing the gray background paint that covers the brown coat

The painting is in excellent condition. The edges of the canvas are supported by a strip liningstrip lining: A conservation technique used to strengthen/repair tacking margins that have weakened or failed. New fabric is adhered to the painting’s damaged tacking margins to allow the stretcher to exert its normal tensioning on the original canvas., which was attached before the painting entered the museum’s collection in 1994. A slightly cupped craquelurecraquelure: The network or pattern of cracks that develop on a paint surface as it ages. is somewhat visually distracting in the darker passages of the portrait. Careful retouchingretouching: Paint application by a conservator or restorer to cover losses and unify the original composition. Retouching is an aspect of conservation treatment that is aesthetic in nature and that differs from more limited procedures undertaken solely to stabilize original material. Sometimes referred to as inpainting or retouch. was applied to reduce the prominence of a few of these cracks and address a small amount of paint abrasionabrasion: A loss of surface material due to rubbing, scraping, frequent touching, or inexpert solvent cleaning. below the nose and at the lower left corner. Retouching also covers frame abrasion at the outermost edges. The current varnish, estimated to be a natural resin, has an appropriate level of saturation and does not appear to be discolored.

Notes

- A similar technique is described in the rendering of Portrait of the Comedian Tournelle, Called Dublin (Fig. 2), in which “‘pinpoint’ touches of paint highlight the eyes.” See Andrew K. Kagan, “A Fogg ‘David’ Reattributed to Madame Adélaide Labille-Guiard,” Acquisitions (Fogg Art Museum) (Cambridge, MA: Fogg Art Museum, 1969–1970), 32.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, Portrait of Joachim Lebreton, 1795,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.416.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, Portrait of Joachim Lebreton, 1795,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.416.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, Portrait of Joachim Lebreton, 1795,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.416.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, Portrait of Joachim Lebreton, 1795,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.416.4033.

Probably given by the artist to the sitter, Joachim Lebreton (1760–1819), Paris, 1795–1819 [1];

Probably to his wife, Anne-Julie Lebreton (née d’Arcet, 1772–1857), Paris, 1819;

To her daughter, Juliette Cloquet (née Lebreton, 1800–42), Paris, by 1842 [2];

To her daughter, Marie Lévesque (née Cloquet, 1825–ca. 1881), Paris, by 1842 [3];

By descent to her daughter, Louise-Henriette Marin (née Lévesque, 1858–1937), Paris, by 1881;

To her son, Victor-Paul Marin (d. ca. 1929), Paris, by 1929;

Inherited by one of his nephews, Jules or Charles Amiot, by 1929–July 2, 1993 [4];

Sold by Jules or Charles Amiot at Tableaux Anciens et du XIXème Siècle, Christie’s Monaco S. A. M., Monte Carlo, December 4, 1993, lot 38, erroneously as Portrait de Jean d’Arcet;

With Didier Aaron, Inc., Paris, as Portrait de Joachim le Breton, by May 13, 1994–November 21, 1994;

Purchased from Didier Aaron, Inc., Paris, by The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1994.

Notes

[1] When the portrait first entered the art market with Christie’s in 1993, it was mistakenly identified as a portrait of Jean d’Arcet, the father-in-law of Joachim Lebreton. Christie’s is the first to suggest the painting was in the collection of Jean d’Arcet, but it seems more likely that the painting would have been in the collection of the sitter, Joachim Lebreton (1760–1819), and afterwards passed to his wife, Anne-Julie d’Arcet. Labille-Guiard probably gave this portrait to Lebreton in appreciation for his assistance in rebuilding the artist’s shattered career after the Revolution (see correspondence from Patricia Telles, Postdoctoral student from Coimbra University CEAACP, Borba, Portugal, to Glynnis Napier Stevenson, NAMA, September 17, 2017, NAMA curatorial file). The painting was not part of the group of art which Lebreton brought to Rio de Janeiro (now in the collection of the Museu Nacional de Belas Artes de Rio) in 1816. Therefore, the painting likely remained in Paris with his wife, Anne-Julie Lebreton.

[2] This and the following provenance is from Tableaux Anciens et du XIXème Siècle (Monte Carlo: Christie’s Monaco S.A.M., December 4, 1993), 38.

[3] Marie Cloquet was the daughter of Jules-Germain Cloquet (1790–1883), a celebrated doctor, and his first wife, Juliette Lebreton, rather than the daughter of Cloquet and his second wife, Frances-Mary Corney, whom he married in 1846. See Pierre C. Berteau, “De Jules Cloquet aux Flaubert,” www.chu-rouen.fr (Accessed October 6, 2017), https://www.chu-rouen.fr/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2017/04/De-Jules-Cloquet-aux-Flaubert-Dr.-Pierre-Berteau-seance-GHHR-5-novembre-2008.pdf.

[4] The Marin family’s last name is often misspelled as “Morin,” as it is in both the Christie’s and Didier Aaron catalogues. Further research has shown that “Marin” is the correct spelling. Victor-Paul Marin died ca. 1929 without an heir. He and his wife never drew up a marriage contract. As a result, his two nephews, Jules and Charles Amiot, and godson, M. Renaud, inherited his property. Charles Amiot was a minor at the time; Jules Amiot was of an age to represent himself legally. The bulk of Victor-Paul Marin’s estate was left to his godson, M. Renaud. See “Certificat de propriété,” Supplément au Journal du Notariat (April 25, 1929): 55–56. The Christie’s 1993 catalogue specifies that the painting came to them from a nephew of the son of “Madame Paul Morin [sic]”. This was probably either Jules or Charles Amiot.

Christie’s Monaco had the painting by July 2, 1993, when they began auctioning off items that belonged to the d’Arcet family.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, Portrait of Joachim Lebreton, 1795,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.416.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, Portrait of Joachim Lebreton, 1795,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.416.4033.

Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, Portrait of a Man, ca. 1795, oil on canvas, 35 ¼ x 23 3/4 x 2 1/4 in. (89.54 x 60.33 x 5.72 cm), Dallas Museum of Art, gift of Michael L. Rosenberg Foundation, 2017.18.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, Portrait of Joachim Lebreton, 1795,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.416.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, Portrait of Joachim Lebreton, 1795,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.416.4033.

Salon de l’an IV, 1795, Musée du Louvre, Paris, no. 236, as Le C. Lebreton, chef des bureaux des Musées a l’instruction publique.

The International Fine Art Fair, The Seventh Regiment Armory, New York, May 13–17, 1994, Booth D6, as Portrait of Joachim Lebreton.

America Collects Eighteenth-Century French Paintings, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, May 21–August 20, 2017, no. 55, as Portrait of Joachim Le Breton.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, Portrait of Joachim Lebreton, 1795,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.416.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, Portrait of Joachim Lebreton, 1795,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.416.4033.

Musée du Louvre, Explication des ouvrages de peinture, sculpture, architecture, gravure, dessins, modèles, etc. (Paris: Imprimerie de la Veuve Hérissant, 1795), 33 [repr. in H. W. Janson, ed., Catalogues of the Paris Salons, 1673 to 1881, vol. 7, Paris Salons de 1793, 1795 (New York: Garland, 1977)], as Le C. Lebreton chef des bureaux des Musées, à l’Instruction publique.

Jules Renouvier, Histoire de l’art pendant la Révolution, considéré principalement dans les estampes (Paris: Veuve Jules Renouard, 1863), 360, as C. Lebreton.

Émile Bellier de la Chavignerie and Louis Auvray, Dictionnaire général des artistes de l’école française depuis l’origine des arts du dessin jusqu’à nos jours (Paris: Librairie Renouard, 1882), 1:718, as Portrait du citoyen Lebreton, chef des bureaux des musées.

Spire Blondel, L’Art pendant la Révolution: Beaux-arts, arts décoratifs, par Spire Blondel (Paris: Henri Laurens, 1887), 58, as le citoyen Lebreton.

Henry Jouin, Joachim Lebreton, premier secrétaire perpétuel de l’Académie des beaux-arts (Paris: Bureaux de l’Artiste, 1892), 23n1, as citoyen Lebreton, chef des bureaux des Musées, à l’Instruction publique.

Roger Portalis, “Adélaïde Labille-Guiard (1749–1803) (quatrième et dernier article),” Gazette des beaux-arts 27, no. 3 (1902): 345, as Citoyen Lebreton.

Roger Portalis, Adélaïde Labille-Guiard (1749–1803) (Paris: Imprimerie Georges Petit, 1902), 79, 92, as Portrait du citoyen Lebreton, chef des Bureaux des musées, à l’Instruction publique.

Arnauld Doria, Gabrielle Capet (Paris: Les Beaux-arts, Édition d’études et de documents, 1934), 23.

Paul Ratouis de Limay, “Une portraitiste du XVIIIème siècle, Madame Labille-Guiard (1749–1803),” Le Dessin; revue d’art, d’éducation et d’enseignement 13, no. 3 (1947): 108, as Joachim Lebreton.

Anne Marie Passez, Adélaide Labille-Guiard, 1749–1803: Biographie et Catalogue raisonné de son œuvre (Paris: Arts et Métiers Graphiques, 1973), no. 139, pp. 8, 40, 271, as Portrait de Joachim Lebreton.

Jean-François Heim, Claire Béraud, and Philippe Heim, Les Salons de peinture de la Révolution française, 1789–1799 (Paris: C. A. C. Sarl. Édition, 1989), 248, as Le C. Lebreton, chef des bureaux des Musées, à l’Instruction publique (n° 236).

Dessins de maître anciens: dessins italiens de la collection d’un amateur français, dessins français de la collection Marcel Puech (Monaco: Christie’s Monaco S.A.M., July 2, 1993), 169, (repro.), erroneously as Portrait de Monsieur Darcet.

Tableaux Anciens et du XIXème Siècle (Monte Carlo: Christie’s Monaco S.A.M., December 4, 1993), 38–39, 42–43, (repro.), erroneously as Portrait de Jean d’Arcet (1749–1803), de buste et assis, portant un gilet rayé rouge et une veste marron.

Catalogue (Paris: Didier Aaron, 1994–1995), unpaginated, (repro.), as Portrait de Joachim Le Breton.

Peter H. Falk and Andrea Ansell Bien, eds., Art Price Index International ’95: 1993–1994 Auction Season (Madison, CT: Sound View Press, 1994), 2:1372, erroneously as Portrait de Jean d’Arcet (1749–1803), de buste et assis.

Enrique Mayer, International Auction Records: January 1 through December 31, 1993; Prints, Drawings, Watercolors, Paintings, Sculpture (Lausanne, Switzerland: Editions Acatos, 1994), 139, 657, erroneously as Portrait Jean-d’Arcet (1749–1803), de buste et assis, portant un gilet rayé rouge et une veste marron.

G. Mohr, M. Wienert, and S. Gerum, eds., Kunstpreis Jahrbuch 1994: Deutsche und Internationale Auktionsergebnisse, vol. 49, no. 1 (Munich: Weltkunst Verlag GmbH, 1994), 742, erroneously as Bildnis Jean d‘Arcet.

The International Fine Art Fair: the Seventh Regiment Armory, Park Avenue at 67th Street, New York City, exh. cat. (London: International Fine Art Fair, 1994), 26, (repro.), as Portrait of Joachim Lebreton.

Patricia J. Fidler, “New at the Nelson: Painting by Noted 18th Century Artist Acquired,” Newsletter (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (June 1995): 2, (repro.), as Portrait of Joachim Le Breton.

Roger Ward, “Recent acquisitions of painting, sculpture and decorative arts at The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art,” Burlington Magazine, supplement, 137, no. 1112 (November 1995): S785, (repro.), as Portrait of Joachim Le Breton.

Philippe Bordes, Portraiture in Paris around 1800: Cooper Penrose by Jacques-Louis David, exh. cat. (San Diego: Timken Museum of Art, 2003), 59–60.

Margaret A. Oppenheimer, The French Portrait: Revolution to Restoration (Northampton, MA: Smith College Museum of Art, 2005), 22, (repro.), as Portrait of Joachim Le Breton.

Mary Sprinson de Jesús, “Adélaïde Labille-Guiard’s Pastel Studies of the Mesdames de France,” Metropolitan Museum Journal 43 (2008): 172n35.

Deborah Emont Scott, ed., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collection, 7th ed. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2008), 108, (repro.), as Portrait of Joachim Le Breton.

Laura Auricchio, Adélaïde Labille-Guiard: Artist in the Age of Revolution (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2009), 100–01, (repro.), as Portrait of Joachim Lebreton.

Bénézit Dictionary of Artists (Paris: Éditions Gründ, 2006), 8:245, as Portrait of Citizen Lebreton, Chief Administrator of the Museums of the Ministry of Education.

Christophe Marcheteau de Quinçay, Marie-Gabrielle Capet (1761–1818): une virtuose de la miniature, exh. cat. (Ghent: Éditions Snoeck, 2014), 19, 67, 94n115, (repro.), as Portrait de Joachim Lebreton.

Patricia Delayti Telles, Retrato entre baionetas: prestígio, política e saudades na pinture do retrato em Portugal e no Brasil, entre 1804 e 1834 (Évora, Portugal: Universidade de Évora, 2015), 225, LIII, (repro.), as Retrato de Joachim Lebreton.

Yuriko Jackall et al., America Collects Eighteenth-Century French Paintings, exh. cat. (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2017), 237, 274, 328, (repro.), as Portrait of Joachim Le Breton.

Patricia Delayti Telles, O Cavaleiro Brito e o Conde da Barca: dois diplomatas portugueses e a missão francesa de 1816 ao Brasil (Lisbon: Documenta, 2017), 18, 92, 179, (repro.), as Retrato de Joachim Lebreton.

Martine Lacas, Peintres femmes, 1780–1830: Naissance d’un combat, exh. cat. (Issy-les-Moulineaux, France: Beaux-arts Editions, 2021), 189, 193, (repro.), as Portrait de Joachim Lebreton.