![]()

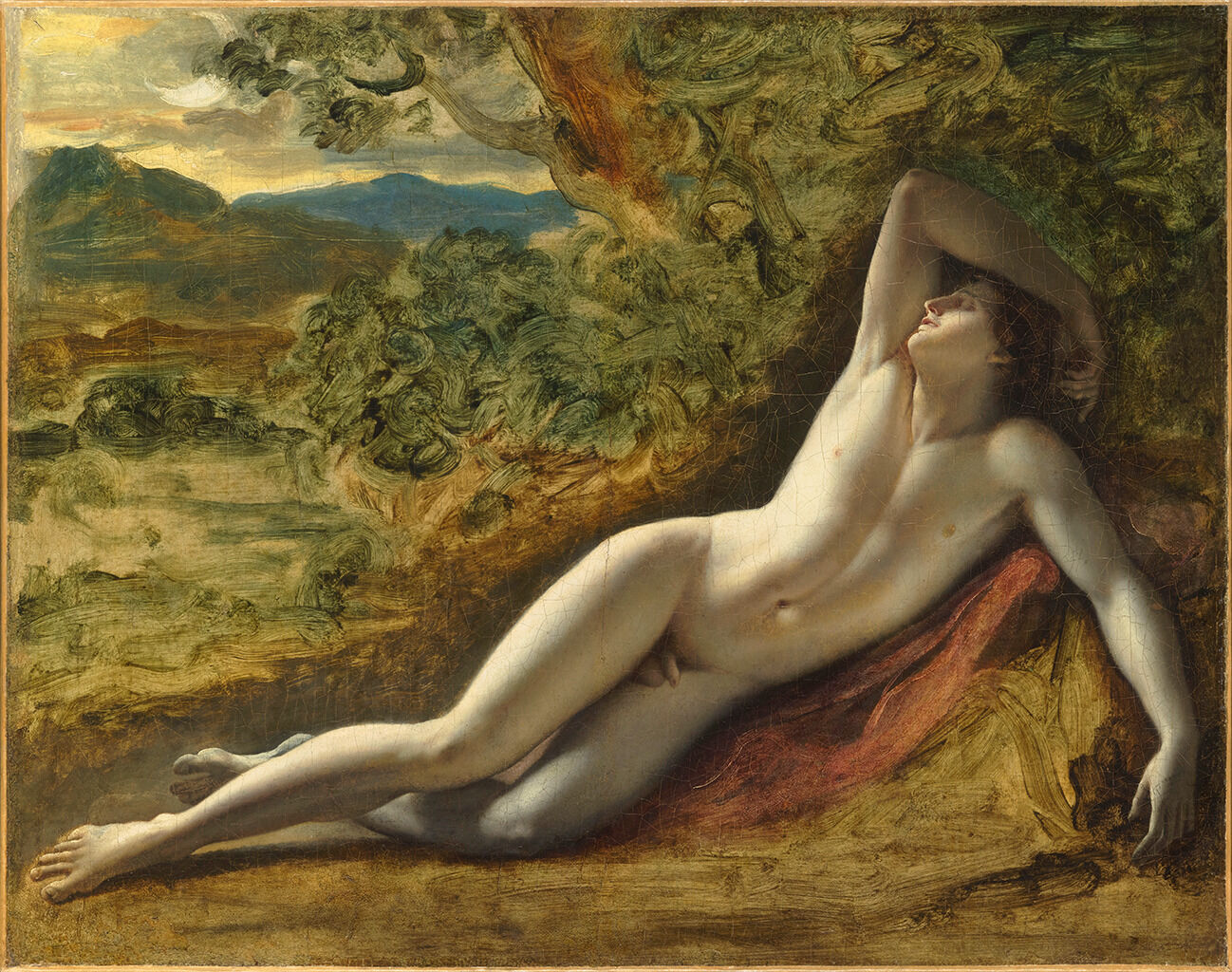

Anne Louis Girodet-Trioson, Sleeping Bacchus, 1790/1791

| Artist | Anne Louis Girodet-Trioson, French 1767–1824 |

| Title | Sleeping Bacchus |

| Object Date | 1790/1791 |

| Alternate and Variant Titles | Le Berger endormi |

| Medium | Oil on panel |

| Dimensions (Unframed) | 14 11/16 × 18 1/4 in. (37.3 × 46.4 cm) |

| Credit Line | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Purchase: Nelson Gallery Foundation through the exchange of various Foundation properties, F98-2 |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Asher Ethan Miller, “Anne Louis Girodet-Trioson, Sleeping Bacchus, 1790/1791,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.412.5407.

MLA:

Miller, Asher Ethan. “Anne Louis Girodet-Trioson, Sleeping Bacchus, 1790/1791,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.412.5407.

Anne Louis Girodet-Trioson first studied drawing in his native Montargis before moving to Paris, approximately seventy miles to the north, with the aim of becoming a professional artist.1Translations are by the author unless otherwise noted. The artist would adopt the name of his guardian, Dr. Benoît François Trioson (d. 1815), long believed to be his biological father, in 1806. In late 1783 or early 1784, after a period of training with architect Étienne Louis Boullée (1728–99), Girodet joined the atelier of history painter Jacques Louis David (1748–1825), where his compatriots and rivals included the most promising young talents of his generation: Jean Germain Drouais (1763–88), François Xavier Fabre (1766–1837), François Gérard (1770–1837), Antoine Jean Gros (1771–1835), and Jean-Baptiste Joseph Wicar (1762–1834). Girodet competed for the Prix de Rome for history painting, which funded an extended stay in Rome, every year from 1786 onward, and he was finally awarded the prize in 1789, for Joseph Recognized by His Brothers (École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, Paris, PRP 28). He arrived in Rome on May 30, 1790, and with one interlude in Genoa, remained there until 1795.2See Bruno Chenique, “La vie d’Anne-Louis Girodet de Roussy (1767–1824), dit Girodet-Trioson: Essai de biochronologie,” digital resource on CD-ROM, included in Sylvain Bellenger, Girodet, 1767–1824, exh. cat. (Paris: Gallimard, 2005).

In a grotto at dawn, the nude Bacchus, god of wine, reclines on a mossy rock, asleep. The curves of his languid form contrast with the simple, straight staff that rests on his shoulder. A leafy wreath pokes through his tousled hair. Other attributes that signal his identity are a leopard skin; assorted gold vessels, including a golden ewer from which wine is spilling; and a tambourine. Bacchus is surrounded by three figures, including two similarly athletic youths and a juvenile faun, all sleeping off a night of revelry. In the distance is a sign that the previous evening’s goings-on are not entirely over: a lusty satyr pursues a female figure who barely manages to evade him.

With the hindsight afforded by Sleeping Endymion, one can gain a sense of why Girodet may not have been satisfied enough with Sleeping Bacchus to proceed with it. Despite its strengths, the sketch represents a balanced and harmonious accumulation of motifs rather than a pictorial conception whose visual impact surpasses the sum of its parts. It was evidently Girodet’s objective to produce something more ambitiously original. That is what he achieved in Sleeping Endymion, with its unbridled sensuality attained through the reduction of the number of figures from six to two, both brought into the same plane, and the animating, ecstatic role of light that makes the daybreak in Sleeping Bacchus seem conventional by comparison. Yet key elements of Sleeping Bacchus were not abandoned in the latter work; rather, they were transformed. Crucially, the two antique sculptures illustrated here share Endymion as a common subject, and thus Girodet was demonstrably preoccupied by the theme. Many years later, Girodet would recall:

The first painting I completed after 1789 is Endymion, painted in Rome in 1790, one year after I won the grand prize for painting. The composition was inspired by a bas-relief at the Villa Borghese [Fig. 4]. I almost copied the [entire] antique Endymion [figural group], but I thought it my duty not to include the figure of Diana [or Selene, because] it seemed to me inappropriate to depict a goddess renowned for her chastity in a scene devoted solely to the contemplation of love. The idea of the ray of light seemed to me more delicate and poetic, and novel besides. The thought came to me whole, as did the cupid in the form of a zephyr, who smiles while pulling aside the foliage. That is why the picture should not be known by the title some people have used, Diana and Endymion, but rather the Sleep of Endymion.7“Le plus ancien de mes tableaux depuis 1789 est l’endymion il fut peint a [sic] Rome en 1790 un an après que j’eux remporté le gd prix de peinture. La composition m’en fut inspirée par un bas relief de la Villa Borghèse. J’ai même presque copié l’endimion antique, mais j’ai cru

inconvenantdevoirsupprimer la déessene point reprendre la figure de Diane il m’a semblé inconvenant derepresenterpeindre dans le moment meme [sic] d’une simple contemplation amoureuse une deesse [sic] renommée par sa chasteté. l’idée du rayon m’a paru plus delicate [sic] et plus poetique [sic] outre qu’elle etait [sic] neuve alors. Cette pensée m’appartient toute entiere [sic] ainsi que celle du jeune amour sous la forme de zephir [sic] qui sourit en ecartant [sic] le feuillage ainsi ce tableau n’est point connu comme quelques personnes l’ont qualifié Diane et Endymion, mais bien le Sommeil d’Endymion.” Girodet, “Endymion,” manuscript note published in Bruno Chenique, “Biochronologie,” 605, under August–September 1807 (original orthography retained).

Girodet’s testimony regarding the ray of light and zephyr coming to him “whole” may be expanded upon. One scholar has suggested that Girodet charged the protagonist of Sleeping Endymion with the energy of Ariadne Sleeping, a celebrated Roman marble installed in 1779 in the Pio Clementino Museum at the Vatican; Ariadne’s pose is close to that of Endymion in the Borghese relief (see Fig. 4).8See Anne Lafont, Girodet (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 2005), 63; and Anne Lafont, “Les Italies de Girodet” in Maria Teresa Caracciolo and Gennaro Toscano, eds., Jean-Baptiste Wicar et son temps, 1762–1834 (Villeneuve d’Ascq: Presses Universitaires du Septentrion, 2007), 431. She employs the term arianisé (an improvised descriptor: “to cause to resemble Ariadne”) in reference to Ariadne Sleeping, Vatican Museums, Rome, inv. 548; on this sculpture, see Francis Haskell and Nicholas Penny, Taste and the Antique: The Lure of Classical Sculpture, 1500–1900 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981), 184–87, cat. no. 24, as Cleopatra. Another, even more rapturous work, the Barberini Faun, which was in the Palazzo Barberini until 1799, may be a further source behind Sleeping Endymion.9See J. J. L. Whitely, “Light and Shade in French Neo-Classicism,” Burlington Magazine 117, no. 873 (December 1975): 773, where Girodet’s Endymion is described as “the Barberini Faun viewed by artificial light.” On the Barberini Faun, now in the Glyptothek, Munich, see Haskell and Penny, Taste and the Antique, 202–05, cat. no. 33, fig. 105. In this way, Girodet amplified themes initially explored in Sleeping Bacchus, departing from the characteristic poise and sober illumination of David’s paintings in favor of a highly dramatic chiaroscuro.

The scene takes place in a grotto, the most common setting in Girodet’s repertoire, encompassing paintings, graphic works, and writings. Anne Lafont has observed that grottos perform a dual symbolic function in the artist’s work, alternately as a “sepulchral vault” or, as here, a sort of “voluptuous den.”10Lafont, Girodet, 39 (voûte sépulcrale; antre volupteux). The best-known example of the former type of grotto serves as the setting in a painting of 1808, Burial of Atala (Musée du Louvre, Paris, inv. 4958), which, given its fictionalized Native American subject—more remote in place than in time—is surprisingly similar to that of Sleeping Bacchus.11The Burial of Atala is based on François-Auguste-René, vicomte de Chateaubriand’s novel Atala, first published in 1801, in Paris, and then included as part of Le Génie du Christianisme (The Genius of Christianity) in 1802; it was finally issued as part of Les Natchez in 1826. More generally, the idealized natural setting of Sleeping Bacchus is suited to its Arcadian subject, fitting squarely into the tradition of Neoclassicism, whose roots can be traced to the seventeenth-century masters Poussin and Claude Lorrain (1604–82). Northern artists who sojourned in Rome followed their forebears’ example by sketching out of doors, a practice that began to flourish in the period of Girodet’s residency, leading to the introduction in 1817 of a prix de Rome in the category of paysage historique (historical landscape). A sleeping figure closely resembling the one in the middle ground of Sleeping Bacchus is found in a characteristic, highly finished drawing dating to Girodet’s Roman years, Landscape with a Woman Frightened by a Serpent (Fig. 5).12See Bellenger, Girodet, 231–32, where the Nelson-Atkins painting is discussed primarily in the context of Girodet’s work as a landscape artist.

There is a copy after the painting, currently unlocated.16Catalogue des Tableaux et des Dessins Provenant de la Collection de Mr. A.-N. Pérignon père, Ancien Commissaire-Expert des Musées Royaux (Paris: Hôtel Drouot, May 17–20, 1865), lot 44. There is also a related drawing, also unlocated, described as “a landscape with a very rich composition; of note are distinct planes, each with groups of nymphs and satyrs, and before them the sleeping Silenus. This drawing is on white paper.”17“Un paysage très-riche de composition; on y remarque sur les différens [sic] plans des groupes de nymphes et de satyres, et en avant Silène endormi. Ce dessin est sur papier blanc.” As described in the catalogue of the second (anonymous) Girodet estate sale, held in his former home at rue Saint-Augustin, Paris, April 3–4, 1826, under lot 24. Cited in Anne Lafont, “Une jeunesse artistique sous la Révolution Girodet avant 1800” (PhD diss., Université Paris IV, Sorbonne, 2001), 2:344.

As an oil sketch by a major figure in the circle of David, Sleeping Bacchus plays a foundational role in the trajectory of history painting as represented in the holdings of the Nelson-Atkins. Neoclassical in subject, style, and function, it anticipates the divide between Neoclassicism and Romanticism embodied in the oil sketch The Oath of Brutus after the Death of Lucretia by Théodore Géricault (1791–1824) and the fully Romantic sketch Christ on the Sea of Galilee by Géricault’s successor, Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863).

Notes

-

Translations are by the author unless otherwise noted. The artist would adopt the name of his guardian, Dr. Benoît François Trioson (d. 1815), long believed to be his biological father, in 1806.

-

See Bruno Chenique, “La vie d’Anne-Louis Girodet de Roussy (1767–1824), dit Girodet-Trioson: Essai de biochronologie,” digital resource on CD-ROM, included in Sylvain Bellenger, Girodet, 1767–1824, exh. cat. (Paris: Gallimard, 2005).

-

For an account of Sleeping Endymion based on the artist’s correspondence between February 1 and October 24, 1791, see Bellenger, Girodet, 209–11.

-

See Stephanie Nevison Brown, “Girodet: A Contradictory Career” (PhD diss., University of London, 1980), 87. A plaster cast of the original marble bas relief is at the University of Cambridge’s Museum of Classical Archaeology, accessed August 4, 2019, https://museum.classics.cam.ac.uk/collections/ casts/endymion-asleep.

-

See Bellenger, Girodet, 209–10. For the Borghese marble, which was acquired by the Louvre in 1808, see Carl Robert, Die Antiken Sarkophag-Reliefs, third series (Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider, 1969), 1:80–82, cat. no. 65, pl. 17; François Baratte and Catherine Metzger, Catalogue des sarcophages en pierre d’époques romaine et paléochrétienne (Paris: Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 1985), 67–69, cat. no. 23; and Jean-Luc Martinez, ed., Les Antiques du Musée Napoléon: Édition illustrée et commentée des volumes V et VI de l’inventaire du Louvre de 1810; Notes et Documents des musées de France 39 (Paris: Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 2004), 428, cat. no. 0865.

-

See Alain Mérot, Nicolas Poussin, trans. Fabia Claris (New York: Abbeville Press, 1990), 273, cat. no. 118, illustrated by means of an eighteenth-century engraving by Mariette after the lost painting of about 1637.

-

“Le plus ancien de mes tableaux depuis 1789 est l’endymion il fut peint a [sic] Rome en 1790 un an après que j’eux remporté le gd prix de peinture. La composition m’en fut inspirée par un bas relief de la Villa Borghèse. J’ai même presque copié l’endimion antique, mais j’ai cru

inconvenantdevoirsupprimer la déessene point reprendre la figure de Diane il m’a semblé inconvenant derepresenterpeindre dans le moment meme [sic] d’une simple contemplation amoureuse une deesse [sic] renommée par sa chasteté. l’idée du rayon m’a paru plus delicate [sic] et plus poetique [sic] outre qu’elle etait [sic] neuve alors. Cette pensée m’appartient toute entiere [sic] ainsi que celle du jeune amour sous la forme de zephir [sic] qui sourit en ecartant [sic] le feuillage ainsi ce tableau n’est point connu comme quelques personnes l’ont qualifié Diane et Endymion, mais bien le Sommeil d’Endymion.” Girodet, “Endymion,” manuscript note published in Bruno Chenique, “Biochronologie,” 605, under August–September 1807 (original orthography retained). -

See Anne Lafont, Girodet (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 2005), 63; and Anne Lafont, “Les Italies de Girodet” in Maria Teresa Caracciolo and Gennaro Toscano, eds., Jean-Baptiste Wicar et son temps, 1762–1834 (Villeneuve d’Ascq: Presses Universitaires du Septentrion, 2007), 431. She employs the term arianisé (an improvised descriptor: “to cause to resemble Ariadne”) in reference to Ariadne Sleeping, Vatican Museums, Rome, inv. 548; on this sculpture, see Francis Haskell and Nicholas Penny, Taste and the Antique: The Lure of Classical Sculpture, 1500–1900 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981), 184–87, cat. no. 24, as Cleopatra.

-

See J. J. L. Whitely, “Light and Shade in French Neo-Classicism,” Burlington Magazine 117, no. 873 (December 1975): 773, where Girodet’s Endymion is described as “the Barberini Faun viewed by artificial light.” On the Barberini Faun, now in the Glyptothek, Munich, see Haskell and Penny, Taste and the Antique, 202–05, cat. no. 33, fig. 105.

-

Lafont, Girodet, 39 (voûte sépulcrale; antre volupteux).

-

The Burial of Atala is based on François-Auguste-René, vicomte de Chateaubriand’s novel Atala, first published in 1801, in Paris, and then included as part of Le Génie du Christianisme (The Genius of Christianity) in 1802; it was finally issued as part of Les Natchez in 1826.

-

See Bellenger, Girodet, 231–32, where the Nelson-Atkins painting is discussed primarily in the context of Girodet’s work as a landscape artist.

-

“Étude légèrement peinte d’après nature, et très piquante d’effet. Elle représente, dans un paysage éclairé par le soleil couchant, Bacchus endormi. On voit, près de lui un jeune faune et plusieurs vases renversés. Dans l’éloignement on aperçoit encore quelques figures légèrement indiquées.” Description of the present work by Pierre-Alexandre Coupin in Tableaux, esquisses, dessins et croquis, de M. Girodet-Trioson, peintre d’histoire, catalogue of the artist’s estate sale, held at 55 Rue Neuve-Saint-Augustin, Paris, April 11, 1825, lot 63.

-

P[ierre]-A[lexandre] Coupin, Œuvres Posthumes de Girodet-Trioson, Peintre d’Histoire; Suivies de sa Correspondance; Précédés d’une Notice Historique, et Mises en Ordre (Paris: Jules Renouard, 1829), 1:lxxiv. Coupin was a staunch partisan of the Neoclassical school, especially after the emergence of Romanticism at the Salon of 1824; his elder brother, the painter Marie Philippe Coupin, called Coupin de la Couperie (1773–1851), had been Girodet’s pupil. See Sidonie Lemeux-Fraitot’s biographical entry on P.-A. Coupin in Rémi Labrusse, Dictionnaire critique des historiens de l’art actifs en France de la Révolution à la Première Guerre mondiale, accessed September 17, 2019, https://www.inha.fr/fr/ressources/publications/ publications-numeriques/dictionnaire-critique-des-historiens-de-l-art/coupin-pierre-alexandre.html.

-

See Laurence Lhinares, “Alexis-Nicolas Perignon (1785–1864), Painter, Expert, Art Dealer and Collector,” Revue des Musées de France 63 (December 2013): 69–78.

-

Catalogue des Tableaux et des Dessins Provenant de la Collection de Mr. A.-N. Pérignon père, Ancien Commissaire-Expert des Musées Royaux (Paris: Hôtel Drouot, May 17–20, 1865), lot 44.

-

“Un paysage très-riche de composition; on y remarque sur les différens [sic] plans des groupes de nymphes et de satyres, et en avant Silène endormi. Ce dessin est sur papier blanc.” As described in the catalogue of the second (anonymous) Girodet estate sale, held in his former home at rue Saint-Augustin, Paris, April 3–4, 1826, under lot 24. Cited in Anne Lafont, “Une jeunesse artistique sous la Révolution Girodet avant 1800” (PhD diss., Université Paris IV, Sorbonne, 2001), 2:344.

Technical Entry

Technical entry forthcoming.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Anne Louis Girodet-Trioson, Sleeping Bacchus, 1790/1791,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.412.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Anne Louis Girodet-Trioson, Sleeping Bacchus, 1790/1791,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.412.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Anne Louis Girodet-Trioson, Sleeping Bacchus, 1790/1791,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.412.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Anne Louis Girodet-Trioson, Sleeping Bacchus, 1790/1791,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.412.4033.

The artist, until December 9, 1824;

Purchased at his posthumous sale, Tableaux, Esquisses, Dessins et Croquis, de M. Girodet-Trioson, peintre d’histoire, membre de l’Institut, officier de la Légion-d’honneur, chevalier de l’ordre de Saint-Michel; De divers ouvrages faits dans son école, De Tableaux, Dessins des trois Écoles, anciens et modernes; Estampes, Recueils, Ouvrages sur les Arts, Lythographies; Médailles et Objets divers d’Antiquité; Armures de tous les pays; Meubles rares, etc., etc., composant son Cabinet; de Figures, Bustes et Fragments divers, moulés en plâtre sur l’Antique; riches Costumes, Peaux d’Animaux, Mannequins, Chevalets, Boîtes à couleur, et objets divers, composant le mobilier de son Atelier, etc., etc., chez Pérignon, rue Neuve-Saint-Augustin, no. 55, Paris, April 11, 1825, lot 63, by Alexis Nicolas Pérignon the Younger (1785–1864), Paris, 1825–September 10, 1864;

His posthumous sale, Tableaux et des Dessins Provenant de la Collection de Mr. A.-N. Pérignon père, Ancien Commissaire-Expert des Musées Royaux, Hôtel Drouot, Paris, May 17–20, 1865, lot 40, as Le Berger endormi, 1865;

Probably a private collection, London, by January 1957 [1];

With Étude Couturier-Nicolay, Paris, by June 2, 1972;

Purchased from their sale, Dessins, Aquarelles et Tableaux Modernes, Dessins et Tableaux Anciens, Objets d’Art, Meubles et Sièges, Tapisseries, Tapis d’Orient et d’Aubusson, Palais Galliéra, Paris, June 2, 1972, lot 92, as Bacchus endormi;

With David Carritt Limited, Artemis Group, London, by summer 1977–at least December 14, 1979 [2];

With E. V. Thaw and Co., New York;

Private collection, United States;

Purchased at the sale, Fine Old Master Pictures: The Properties of the Lady Anne Bentinck (removed from Welbeck Abbey); the late Theodore Besterman; P. Haigh, Esq.; the Vicar and Churchwardens of Hartland Parish, North Devon; the Late the 4th Lord Leigh (sold by order of the Executors); R.E.D. Shafto, Esq.; Sir Sacheverell Sitwell, Bt., and from various sources, Christie’s, London, December 17, 1981, no. 121, as Bacchus asleep;

With Artemis Fine Arts Inc., New York, by October 20–December 15, 1997;

Purchased from Artemis Fine Arts Group by The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1997.

Notes

[1] Per Flora Allen of Christie’s, a painting with the Christie’s inventory number GK598, the same as on the back of the Nelson-Atkins painting, was brought into the auction house for advice in January 1957. However, the painting was not put up for sale through Christie’s and they did not make note of the artist, subject, or current owner. See email from Flora Allen, Old Master Paintings, Christie’s, to Ann Friedman, Nelson-Atkins, January 23, 2020, Nelson-Atkins curatorial files.

[2] See Chiara Savettieri, “‘Il avait retrouvé le secret de Pygmalion’: Girodet, Canova e l’illusione della vita,” Studiolo 2 (2003): 36n36, which asserts that the painting’s owner after the Palais Galliéra sale in 1972 was a Munich-based dealer. That is likely a reference to Arnoldi-Livie, who had it on consignment from David Carritt from summer 1977 to fall 1979. See email from Lea Peyruse-Boroffka, Galerie Arnoldi-Livie, to Ann Friedman, Nelson-Atkins, November 21, 2019, Nelson-Atkins curatorial files.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Anne Louis Girodet-Trioson, Sleeping Bacchus, 1790/1791,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.412.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Anne Louis Girodet-Trioson, Sleeping Bacchus, 1790/1791,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.412.4033.

Anne Louis Girodet-Trioson, Endymion: Moonlight Effect, also called The Sleep of Endymion, 1791, oil on canvas, 77 3/4 x 102 3/4 in. (198 x 261 cm), Musée du Louvre, Paris, INV 4935.

Anne Louis Girodet-Trioson, Sketch for Sleeping Endymion, 1792, oil on canvas, 19 1/8 x 22 1/16 in. (48.6 x 56 cm), Musée du Louvre, Paris, RF 2152.

Anne Louis Girodet-Trioson, The Sleep of Endymion (Blond), ca. 1808–10, oil on canvas, 21 5/8 x 28 3/4 in. (55 x 73 cm), purchased from Stair Sainty, London, 2018.

Possibly Anne Louis Girodet-Trioson, Sleeping Silenus, drawing on white paper, cited in Notice de tableaux, dessins, estampes, vignettes et lithographies, émaux, médailles anciennes et modernes, en argent et en bronze, et objets divers (Paris: C. P. Pérignon et Bonnefons, April 3–4, 1826), no. 24, as Silène endormi.

Copies

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Anne Louis Girodet-Trioson, Sleeping Bacchus, 1790/1791,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.412.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Anne Louis Girodet-Trioson, Sleeping Bacchus, 1790/1791,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.412.4033.

After Anne Louis Girodet-Trioson, Le berger endormi (The Sleeping Shepherd), unknown date, unknown medium, unknown dimensions, location unknown, cited in Catalogue des Tableaux et des Dessins Provenant de la Collection de Mr. A.-N. Pérignon père, Ancien Commissaire-Expert des Musées Royaux (Paris: Hôtel Drouot, May 17–20, 1865), 8.

After Anne Louis Girodet-Trioson, Sleeping Bacchus, ca. 1800, oil on canvas, 15 x 17 5/16 in. (38 x 44 cm), Boris Wilnitsky Fine Arts, Vienna.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Anne Louis Girodet-Trioson, Sleeping Bacchus, 1790/1791,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.412.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Anne Louis Girodet-Trioson, Sleeping Bacchus, 1790/1791,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.412.4033.

Gemälde und Zeichnungen: Neuerwerbungen, Galerie Arnoldi-Livie, Munich, summer 1977, no. 13, as Schlaftrunkener Bacchus mit Gefolge.

The Classical Ideal: Athens to Picasso, David Carritt Limited, London, November 15–December 14, 1979, no. 22, as Sleeping Bacchus.

Selected 19th Century Paintings and Works on Paper, Artemis Fine Arts, Inc., New York, October 20–November 28, 1997, no. 1, as Sleeping Bacchus.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Anne Louis Girodet-Trioson, Sleeping Bacchus, 1790/1791,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.412.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Anne Louis Girodet-Trioson, Sleeping Bacchus, 1790/1791,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.412.4033.

[Alexis Nicolas] Pérignon, Catalogue des Tableaux, Esquisses, Dessins et Croquis, de M. Girodet-Trioson, peintre d’histoire, membre de l’Institut, officier de la Légion-d’honneur, chevalier de l’ordre de Saint-Michel; De divers ouvrages faits dans son école, De Tableaux, Dessins des trois Écoles, anciens et modernes; Estampes, Recueils, Ouvrages sur les Arts, Lythographies; Médailles et Objets divers d’Antiquité; Armures de tous les pays; Meubles rares, etc., etc., composant son Cabinet; de Figures, Bustes et Fragments divers, moulés en plâtre sur l’Antique; riches Costumes, Peaux d’Animaux, Mannequins, Chevalets, Boîtes à couleur, et objets divers, composant le mobilier de son Atelier, etc., etc. (Paris: Pérignon et Bonnefons-Lavialle, April 11, 1825), 18.

P[ierre]-A[lexandre] Coupin, Œuvres posthumes de Girodet-Trioson, peintre d’histoire; Suivies de sa correspondance; Précédés d’une notice historique, et mises en ordre (Paris: Jules Renouard, 1829), 1:lxxiv, as Étude légèrement peinte d’après nature et très piquante d’effet.

Vente par suite de Décès: Catalogue des Tableaux et des Dessins Provenant de la Collection de Mr. A.-N. Pérignon père, Ancien Commissaire-Expert des Musées Royaux (Paris: Hôtel Drouot, May 22–23, 1865), 8, as Le Berger endormi.

Dessins, Aquarelles et Tableaux Modernes, Dessins et Tableaux Anciens, Objets d’Art, Meubles et Sièges, Tapisseries, Tapis d’Orient et d’Aubusson (Paris: Étude Couturier-Nicolay, June 2, 1972), unpaginated, (repro.), as Bacchus endormi.

Emmanuel Bénézit, Dictionnaire critique et documentaire des peintres, sculpteurs, dessinateurs et graveurs de tous les temps et de tous les pays (Paris: Gründ, 1976), 5:43, as Bacchus endormi.

Gemälde und Zeichungen: Neuerwerbungen, Sommer 1977, exh. cat. (Munich: Galerie Arnoldi-Livie, 1977), unpaginated, (repro.), as Schlaftrunkener Bacchus mit Gefolge.

The Classical Ideal: Athens to Picasso, exh. cat. (London: David Carritt, 1979), 31, (repro.), as Sleeping Bacchus.

Neil MacGregor, “Roman Fashions, London,” Burlington Magazine 121, no. 920 (November 1979): 741.

Fine Old Master Pictures: The Properties of the Lady Anne Bentinck (removed from Welbeck Abbey); the late Theodore Besterman; P. Haigh, Esq.; the Vicar and Churchwardens of Hartland Parish, North Devon; the Late the 4th Lord Leigh (sold by order of the Executors); R.E.D. Shafto, Esq.; Sir Sacheverell Sitwell, Bt., and from various sources (London: Christie’s, December 17, 1981), 45, (repro.), as Bacchus asleep.

E. Mayer, International Auction Records 1982 (Paris: Éditions Mayer, 1982), 16:851, as Sleeping Bacchus.

Selected 19th Century Paintings and Works on Paper, exh. cat. (New York: Artemis Fine Arts, 1997), unpaginated, (repro.), as Sleeping Bacchus.

Lee Pentecost, “French Painting Added to European Art Collection,” Newsletter (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (April 1998): 2, (repro.), as Sleeping Bacchus.

Newsletter (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (November 2002): 12, (repro.), as Sleeping Bacchus.

Chiara Savettieri, “‘Il avait retrouvé le secret de Pygmalion’: Girodet, Canova e l’illusione della vita,” Studiolo 2 (2003): 19, 36n36, (repro.), as Bacco addormentato.

Valérie Bajou and Sidonie Lemeux-Fraitot, Inventaire après décès de Gros et de Girodet: Documents inédits (Paris: Valérie Bajou et Sidonie Lemeux-Fraitot, 2003), 257, 354–55, as Etude légèrement peinte d’après nature, et très-piquante d’effet. Elle représente, dans un paysage éclairé par le soleil couchant, Bacchus endormi. On voit près de lui un jeune faune et plusieurs vases renversés. Dans l’éloignement on aperçoit encore quelques figures légèrement indiquées and Bacchus endormi.

Sylvain Bellenger, Girodet, 1767–1824, exh. cat. (Paris: Gallimard, 2005), 210, 231–32, 233n31, (repro.), as Bacchus endormi.

Anne Lafont, Girodet (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 2005), 42, 45, 47, 61, 63, (repro.), as Bacchus endormi.

Maria Teresa Caracciolo and Gennaro Toscano, eds., Jean-Baptiste Wicar et son temps, 1762–1834 (Villeneuve d’Ascq, France: Presses Universitaires du Septentrion, 2007), 428–29, 431, (repro.), as Bacchus endormi.

Véronique Dalmasso, ed., Façons d’Endormis: Le Sommeil entre inspiration et creation (Paris: Éditions Le Manuscrit, 2012), 85.

Larry H. Peer and Christopher R. Clason, eds., Romantic Rapports: New Essays on Romanticism Across the Disciplines (Rochester, NY: Camden House, 2017), 101, as Sleeping Bacchus.

Émilie Beck Saiello and Jean-Noël Bret, eds., Le Grand Tour et l’Académie de France à Rome: XVIIe–XIXe siècles (Paris: Hermann Éditeurs, 2018), 203, as Bacchus endormi.

Chiara Savettieri, Girodet face à Géricault ou la bataille romantique du Salon de 1819, exh. cat. (Montargis, France: Musée Girodet et Liénart, 2019), 116, (repro.), as Bacchus endormi.