Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Kenneth Brummel, “Henri Matisse, Seated Young Woman with an Amber Necklace, December 1942,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.802.5407.

MLA:

Brummel, Kenneth. “Henri Matisse, Seated Young Woman with an Amber Necklace, December 1942,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.802.5407.

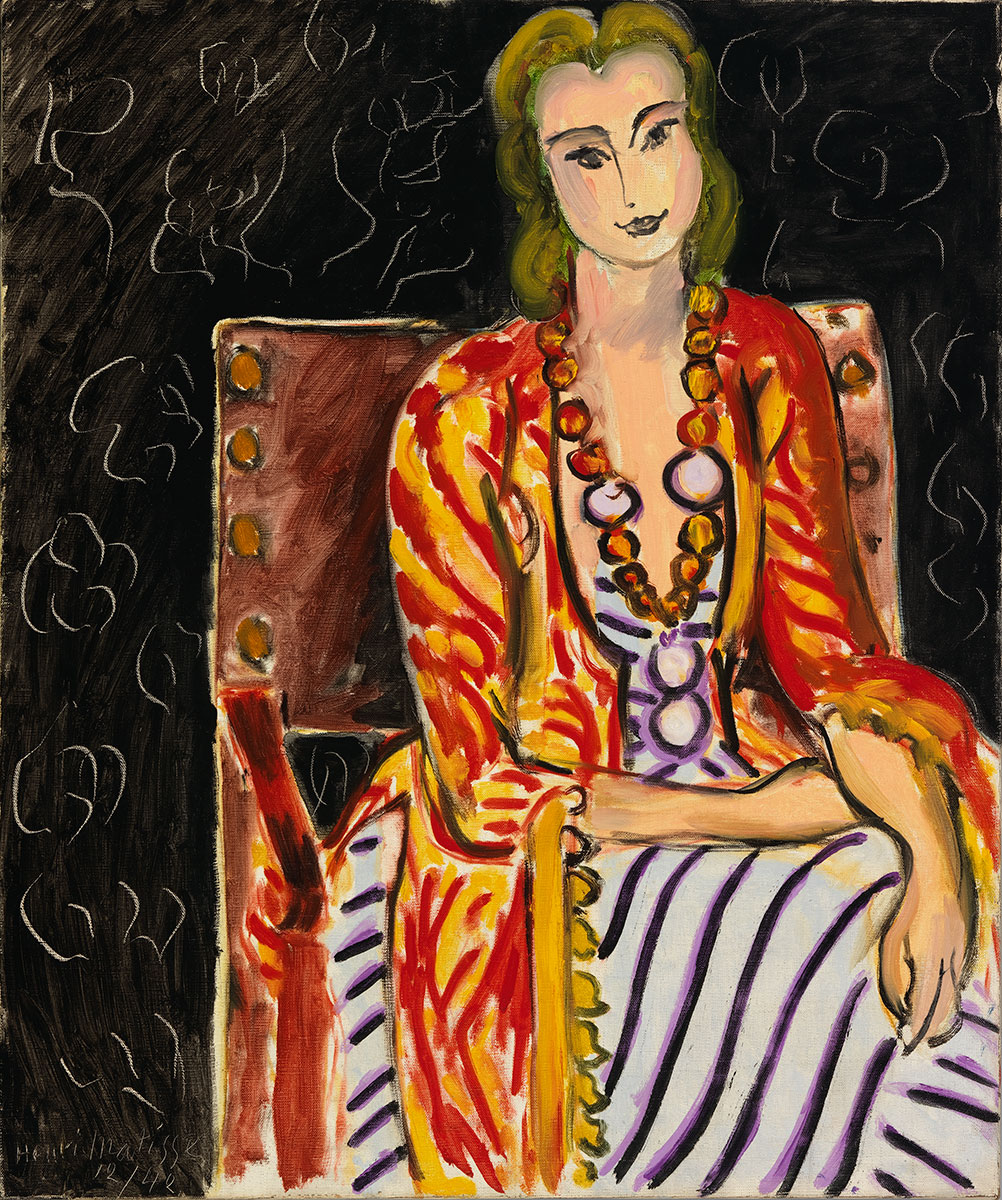

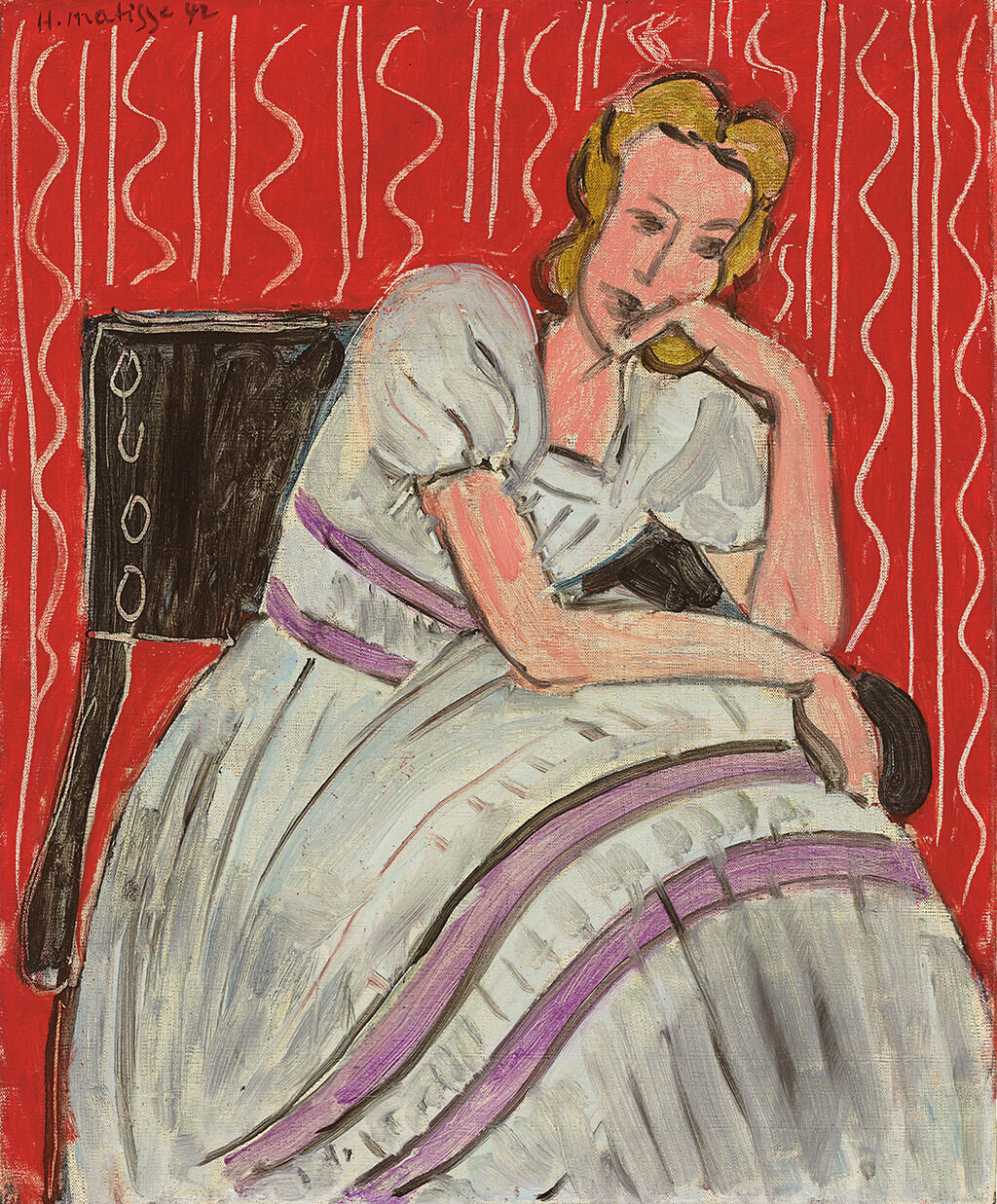

In Seated Young Woman with an Amber Necklace,1Ever since the painting was exhibited at Galerie Beyeler, Basel, in 1980 as Femme assise sur fond noir (Woman seated before a black background), it has retained some variant of that title. See Matisse: Huiles, gouaches, découpées, dessins, sculptures, exh. cat. (Basel: Galerie Beyeler, 1980), unpaginated. Most recently, Saul Nelson, in Never Ending: Modernist Painting Past and Future (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2024), called the painting Woman Seated before a Black Background (180). However, Matisse, in a journal entry dated June 12, 1943, referred to the picture as “Monette au collier d’ambre”; Archives Matisse, Issy-les-Moulineaux, France. Lydia Delectorskaya, Matisse’s model and studio manager, titles the work Robe persane, gros collier d’ambre (Persian dress, large amber necklace) in Henri Matisse: Contre vents et marées: Peinture et livres illustrés de 1939 à 1943 (Paris: Irus et Vincent Hansma, 1996), 429, which is currently the most comprehensive catalogue for Matisse’s work for 1939–43. Because the two other paintings in the series to which the Nelson-Atkins painting belongs are titled Seated Young Woman in a Gray Dress (Fig. 2) and Seated Young Woman in a Persian Dress (Fig. 3), the Nelson-Atkins has chosen the title Seated Young Woman with an Amber Necklace. Describing the model’s pose and distinguishing costume element, this title is consistent with the titles of the other works in the series and with the focus of Matisse and Delectorskaya on the sitter’s necklace. Henri Matisse tackled various binary oppositions that structured his art and modern French painting in the early 1940s. On June 7, 1942, the former FauveFauve: French for “wild beasts.” A term coined in 1905 by the conservative art critic Louis Vauxcelles (1870–1943) to mock Henri Matisse (1869–1954), André Derain (1880–1954), and other artists who exhibited at the Salon d’Automne that year. Vauxcelles objected to these artists’ bold, non-naturalistic colors, which were sometimes applied onto the canvas straight from the paint tube, and their simplified, unsystematically rendered forms, which gave their paintings an almost abstract appearance. The Fauves’ use of vibrant colors to communicate emotional states inspired artists associated with Expressionism and other twentieth-century avant-garde movements. told his son, the art dealer Pierre Matisse, that he wanted to achieve in painting what he had accomplished in drawing “without contradiction.”2“. . . faire en peinture ce que j’ai fait en dessin—rentrer dans la peinture sans contradiction comme dans les dahlias—dans le bouquet de fleurs dont tu m’as envoyé la photographie—et qui a besoin de la forte personnalité du peintre pour que la bataille laisse des restes intéressants.” Henri Matisse to Pierre Matisse, June 7, 1942, quoted in First Papers of Surrealism, exh. cat. (New York: Coordinating Council of French Relief Societies, Inc., 1942), [26]. Jack Flam translates this passage as: “. . . to do in painting what I have done in drawing—return to painting without contradiction as in the dahlias—in the bouquet of flowers that you sent me a photograph of—and which needs the strong personality of the painter in order for the battle to leave interesting remains.” Flam, “On Transformations, 1942,” in Matisse on Art, rev. ed. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), 143. While the artist felt that his freely rendered drawings, such as those in his recently completed Thèmes et variations (1941–42),3Thèmes et variations is a set of 158 drawings Matisse rendered in 1941–42 that were published as a portfolio in 1943 as Henri Matisse, Dessins: Thèmes et variations (Paris: Martin Fabiani, 1943). Beginning with a charcoal drawing, or one of his “thèmes,” Matisse then explored “variations” on that theme in pen and India ink, black Conté crayon, or pencil. The set contains seventeen themes, lettered A to P, with each theme consisting of three to nineteen variations. One example of a drawing from this set is Thèmes et variations (Série L, variation 9) (1942; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art), https://www.sfmoma.org/artwork/54.3280/. captured his sensations and emotions, he worried that his paintings’ expressiveness was hampered by their carefully calibrated, flat areas of color.4For the most relevant example of this articulated concern, see Henri Matisse to Pierre Bonnard, January 13, 1940, in Bonnard/Matisse: Letters between Friends, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Abrams, 1992), 58. Matisse hoped to resolve this dilemma in works like the Nelson-Atkins picture. Executed on a white groundground layer: An opaque preparatory layer applied to the support, either commercially or by the artist, to prevent absorption of the paint into the canvas or panel. See also priming layer. that the artist used to cover a previous paint application,5See accompanying technical essay by Diana M. Jaskierny. this composition was made mostly with thinned pigments and gestural brushwork. The model’s blonde curls, for example, were built up with strokes of yellow paint mixed with an underlying green block-in layer and the black pigment of the painting’s dark background. Painting this and other sections of the picture in an alla prima (Italian for “at first attempt”) fashion, the artist created colorful equivalents to his swiftly made drawings in the medium of oil on canvas.

Squaring painting with drawing in Seated Young Woman with an Amber Necklace, Matisse also deconstructed the differences between shades and colors. He depicted the sitter’s robe with bars of red and yellow, using his paintbrush as if it were a pen or a piece of charcoal to describe her dress with long and short stripes of black and cobalt violet.6John Twilley identifies the purple pigment in the sitter’s dress as cobalt violet in his “Scientific Studies of Matisse’s Woman Seated, 1942, no. 2015-13-13,” unpublished scientific report, October 2, 2024, NAMA conservation file. Because these marks are thin and curvilinear, they resonate with the pattern of arabesques the artist inscribed into the painting’s black backdrop with either a palette knife or the handle of a paintbrush.7See accompanying technical essay by Jaskierny. Transforming that dark field into something that resembles one of his linocutslinocut: A relief printmaking technique characterized by supple lines and flat areas of color. Using a sharp knife, V-shaped chisel, or similar implement, a design is cut into or gouged from a sheet of linoleum, which is softer and easier to carve than wood. The raised, uncarved surface is then inked with a brayer (roller) and impressed onto a paper or fabric support. The resulting composition is a negative image in reverse of the carved design. Introduced in the 1890s, linocuts became increasingly popular in the twentieth century.,8According to Delectorskaya, Matisse became intensely interested in the medium of linocut in the summer of 1938; Delectorskaya, Henri Matisse: Contre vents et marées, 156. Alfred Barr, citing a linocut of a “girl’s head” printed in XXe siècle in 1938, states that Matisse first began to experiment with the “linoleum engraving medium” in 1937; Alfred Barr, Matisse: His Art and His Public (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1951), 271, 548n4. Matisse not only likened painting to a graphic medium but lightened the weight of the black plane and brought it optically forward, enabling it to snap into a flattened, decorative unity with the composition’s other painted elements. Not a shadowed area marginal to the picture but instead what Matisse in a 1941 interview called a coloristic “force” that contributes to the painting’s overall chromatic harmony, the large black background of Seated Young Woman with an Amber Necklace is a source of warmth and luminosity in the composition.9“Instinctivement. J’ai fini par considérer les couleurs comme des forces qu’il fallait assembler selon son inspiration. Les couleurs sont transformables par les rapports, c’est-à-dire qu’on noir deviant tantôt noir-rouge si on le met près d’une couleur un peu froide comme le bleu de Prusse, tantôt noir-bleu si on le met près d’une couleur qui a un froid extrêmement chaud: orangé par exemple” (Instinctively. I finally came to consider colors as forces, to be assembled as inspiration dictates. Colors can be transformed by relation; a black becomes black-red if you put it next to a rather cold color like Prussian blue, blue-black if you put it alongside a color that has an extremely hot basis: orange, for example). “Neuvième Conversation,” in Henri Matisse with Pierre Courthion, Chatting with Henri Matisse: The Lost 1941 Interview, ed. Serge Guilbaut, trans. Chris Miller (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2013), 139, 333. Matisse made similar remarks in 1945 and 1946, which were published in Galerie Maeght’s catalogue for an exhibition titled Le noir est une couleur in Derrière le Miroir, no. 1 (December 1946), unpaginated. For analyses of these remarks, see Dominique Fourcade, Henri Matisse: Écrits et propos sur l’art, rev. ed. (Paris: Hermann, éditeurs des sciences et des arts, 1972), 202, 202n64; and Flam, Matisse on Art, 165–66, 291n5. By treating black not as a shade but as a shimmering chroma, Matisse upends traditional understandings of light and dark in the Nelson-Atkins picture.10Yve-Alain Bois offers a similar analysis of Tulips and Oysters on a Black Background (February 11–12, 1943; Musée National Picasso-Paris, https://cep.museepicassoparis.fr/explorer/tulipes-et-huitres-sur-fond-noir-mp2017-23), another painting by Matisse with a black, scratched background, in Yve-Alain Bois, Matisse and Picasso, exh. cat. (Paris: Flammarion, 1998), 142, 149. Delectorskaya assigns exact dates to this picture in Henri Matisse: Contre vents et marées, 469.

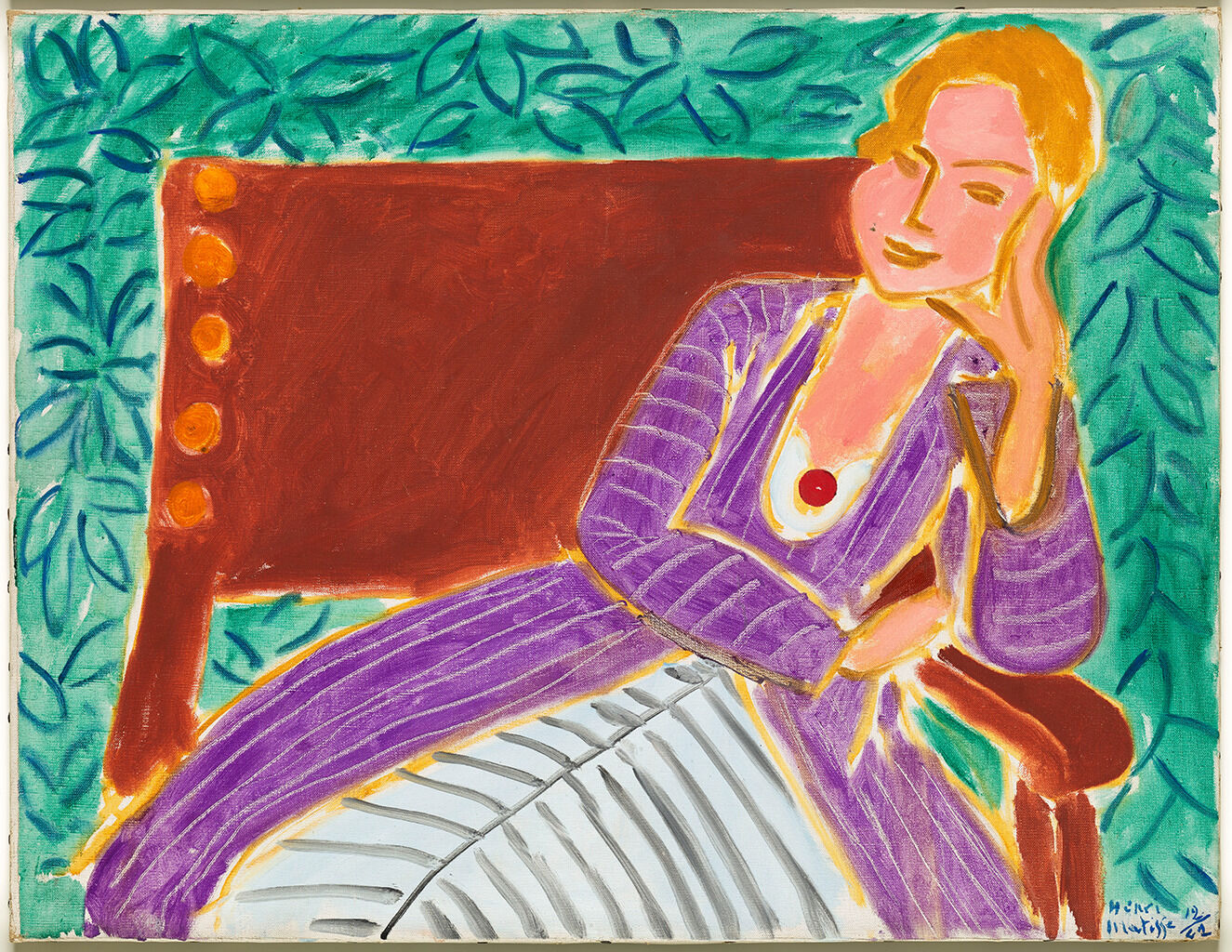

Fig. 3. Henri Matisse, Seated Young Woman in a Persian Dress, 1942, oil on canvas, 17 1/8 x 22 1/4 in. (43.5 x 56.5 cm), Musée National Picasso-Paris, no. MP2017-27. Photo: Mathieu Rabeau / Art Resource, NY. © 2024 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Fig. 3. Henri Matisse, Seated Young Woman in a Persian Dress, 1942, oil on canvas, 17 1/8 x 22 1/4 in. (43.5 x 56.5 cm), Musée National Picasso-Paris, no. MP2017-27. Photo: Mathieu Rabeau / Art Resource, NY. © 2024 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Fig. 4. Hélène Adant, Three carved wooden armchairs in Matisse’s studio, Vence, ca. 1946, gelatin silver print, Fonds Hélène Adant, Archives de la Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Centre Pompidou, Paris, no. M5050_X0031_ADA_3_580

Fig. 4. Hélène Adant, Three carved wooden armchairs in Matisse’s studio, Vence, ca. 1946, gelatin silver print, Fonds Hélène Adant, Archives de la Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Centre Pompidou, Paris, no. M5050_X0031_ADA_3_580

Fig. 5. Turkish entari (woman’s robe), 19th century, silk, 63 x 21 5/8 in. (160 x 55 cm), private collection, reproduced in Matisse, His Art and His Textiles: The Fabric of Dreams, ed. Hilary Spurling and Ann Dumas, exh. cat. (London: Royal Academy, 2004), 103. Photo by Todd May Photography

Fig. 5. Turkish entari (woman’s robe), 19th century, silk, 63 x 21 5/8 in. (160 x 55 cm), private collection, reproduced in Matisse, His Art and His Textiles: The Fabric of Dreams, ed. Hilary Spurling and Ann Dumas, exh. cat. (London: Royal Academy, 2004), 103. Photo by Todd May Photography

Fig. 6. Photograph of Simone “Monette” Vincent, ca. 1942, in Lydia Delectorskaya, Henri Matisse: Contre vents et marées: Peinture et livres illustrés de 1939 à 1943 (Paris: Irus et Vincent Hansma, 1996), 354

Fig. 6. Photograph of Simone “Monette” Vincent, ca. 1942, in Lydia Delectorskaya, Henri Matisse: Contre vents et marées: Peinture et livres illustrés de 1939 à 1943 (Paris: Irus et Vincent Hansma, 1996), 354

Equally transformative was Matisse’s ability to make a sale feel like a gift when he transferred Seated Young Woman with an Amber Necklace to the Parisian banker Max Pellequer (before 1903–after 1973)28While Grammont assigned the life dates of “(?– 1974)” to the collector (entry on Pellequer, in Grammont, Tout Matisse, 881), Anna Jozefacka provides the life dates as “before 1903–after 1973”; Anna Jozefacka, “Pellequer, Max,” The Modern Art Index Project, January 2015, revised by Lauren Rosati, December 2019, Leonard A. Lauder Research Center for Modern Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://doi.org/10.57011/ZXYW6521. on June 12, 1943.29Matisse recorded the exchange in a journal entry dated June 12, 1943, Archives Matisse, Issy-les-Moulineaux, France: “Remis à Max Pellequer son tableau (‘Monette au collier d’ambre’)” (Given to Max Pellequer his painting [“Monette with the Amber Necklace”]). Translation by Kenneth Brummel. The author wishes to thank Anne Théry, Archives Henri Matisse, and MacKenzie Mallon, NAMA, for their assistance with this research. This, at least, is how Pellequer interpreted the exchange. Twelve days after his purchase, Pellequer wrote to thank the artist for the “delicacy” and “chic” with which he offered the painting. “You wanted to give me the impression that I had bought it from you, whereas I still have the pleasant feeling that you gave me a real gift,” he effused.30“Vous m’avez permis d’acquérir un splendide tableau et vous l’avez fait avec une belle délicatesse, un tel chic qui vous avez voulu me donner l’impression que je vous l’avais acheté alors que je garde la sensation agréable que vous m’avez fait un veritable cadeau” (You enabled me to acquire a splendid painting, and you did it with such delicacy and chic, you wanted to give me the impression that I had bought it from you, whereas I still have the pleasant feeling that you gave me a real gift). Max Pellequer to Henri Matisse, June 24, 1943, Archives Matisse, Issy-les-Moulineaux, France; translation by Kenneth Brummel. According to Grammont, the painting mentioned in this passage is the Nelson-Atkins picture. Claudine Grammont to MacKenzie Mallon, NAMA, February 22, 2023, NAMA curatorial files. The author wishes to thank MacKenzie Mallon and Claudine Grammont, Musée Matisse, Nice, for their assistance with this research. Pellequer also gave an account of his recent visit, with the painter Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881–1973), to the studio of the publisher André Lejard, who was photographing a group of Matisse’s paintings for an upcoming publication.31Max Pellequer to Henri Matisse, June 24, 1943, Archives Matisse. For two other discussions of this section of Pellequer’s letter, see Hélène Seckel-Klein’s entry on Henri Matisse in Picasso collectionneur, exh. cat. (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 1998), 172; and Bois, Matisse and Picasso, 133, 136. Lejard’s publication was Matisse: Seize peintures, 1939–1943 (Paris: Éditions du Chêne, 1943). Pellequer began by telling Matisse that Picasso, who for several decades was Matisse’s friend and artistic rival, was delighted with the painting Matisse had recently given to him.32To date, scholars do not know which picture this is. For a discussion about this particular picture, see Bois, Matisse and Picasso, 133. Pellequer then explained that Picasso, as Matisse had authorized, decided to substitute that work for one of the other pictures at Lejard’s: Seated Young Woman in a Persian Dress, the third canvas in the series that includes the Nelson-Atkins picture. According to painter Françoise Gilot (1921–2023), Picasso’s lover and muse from 1943 to 1953, the picture’s gaudy colors attracted the artist. When Picasso collected the painting at Lejard’s, he openly wondered if he would ever be able to replicate the painting’s bold matching of “such a mauve with such a green.”33See Françoise Gilot, Matisse and Picasso: A Friendship in Art (New York: Doubleday, 1990), 29.

Notes

-

Ever since the painting was exhibited at Galerie Beyeler, Basel, in 1980 as Femme assise sur fond noir (Woman seated before a black background), it has retained some variant of that title. See Matisse: Huiles, gouaches, découpées, dessins, sculptures, exh. cat. (Basel: Galerie Beyeler, 1980), unpaginated. Most recently, Saul Nelson, in Never Ending: Modernist Painting Past and Future (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2024), called the painting Woman Seated before a Black Background (180). However, Matisse, in a journal entry dated June 12, 1943, referred to the picture as “Monette au collier d’ambre”; Archives Matisse, Issy-les-Moulineaux, France. Lydia Delectorskaya, Matisse’s model and studio manager, titles the work Robe persane, gros collier d’ambre (Persian dress, large amber necklace) in Henri Matisse: Contre vents et marées: Peinture et livres illustrés de 1939 à 1943 (Paris: Irus et Vincent Hansma, 1996), 429, which is currently the most comprehensive catalogue for Matisse’s work for 1939–43. Because the two other paintings in the series to which the Nelson-Atkins painting belongs are titled Seated Young Woman in a Gray Dress (Fig. 2) and Seated Young Woman in a Persian Dress (Fig. 3), the Nelson-Atkins has chosen the title Seated Young Woman with an Amber Necklace. Describing the model’s pose and distinguishing costume element, this title is consistent with the titles of the other works in the series and with the focus of Matisse and Delectorskaya on the sitter’s necklace.

-

“. . . faire en peinture ce que j’ai fait en dessin—rentrer dans la peinture sans contradiction comme dans les dahlias—dans le bouquet de fleurs dont tu m’as envoyé la photographie—et qui a besoin de la forte personnalité du peintre pour que la bataille laisse des restes intéressants.” Henri Matisse to Pierre Matisse, June 7, 1942, quoted in First Papers of Surrealism, exh. cat. (New York: Coordinating Council of French Relief Societies, Inc., 1942), [26]. Jack Flam translates this passage as: “. . . to do in painting what I have done in drawing—return to painting without contradiction as in the dahlias—in the bouquet of flowers that you sent me a photograph of—and which needs the strong personality of the painter in order for the battle to leave interesting remains.” Flam, “On Transformations, 1942,” in Matisse on Art, rev. ed. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), 143.

-

Thèmes et variations is a set of 158 drawings Matisse rendered in 1941–42 that were published as a portfolio in 1943 as Henri Matisse, Dessins: Thèmes et variations (Paris: Martin Fabiani, 1943). Beginning with a charcoal drawing, or one of his “thèmes,” Matisse then explored “variations” on that theme in pen and India ink, black Conté crayon, or pencil. The set contains seventeen themes, lettered A to P, with each theme consisting of three to nineteen variations. One example of a drawing from this set is Thèmes et variations (Série L, variation 9) (1942; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art).

-

For the most relevant example of this articulated concern, see Henri Matisse to Pierre Bonnard, January 13, 1940, in Bonnard/Matisse: Letters between Friends, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Abrams, 1992), 58.

-

See accompanying technical essay by Diana M. Jaskierny.

-

John Twilley identifies the purple pigment in the sitter’s dress as cobalt violet in his “Scientific Studies of Matisse’s Woman Seated, 1942, no. 2015-13-13,” unpublished scientific report, October 2, 2024, NAMA conservation file.

-

See accompanying technical essay by Jaskierny.

-

According to Delectorskaya, Matisse became intensely interested in the medium of linocut in the summer of 1938; Delectorskaya, Henri Matisse: Contre vents et marées, 156. Alfred Barr, citing a linocut of a “girl’s head” printed in XXe siècle in 1938, states that Matisse first began to experiment with the “linoleum engraving medium” in 1937; Alfred Barr, Matisse: His Art and His Public (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1951), 271, 548n4.

-

“Instinctivement. J’ai fini par considérer les couleurs comme des forces qu’il fallait assembler selon son inspiration. Les couleurs sont transformables par les rapports, c’est-à-dire qu’on noir deviant tantôt noir-rouge si on le met près d’une couleur un peu froide comme le bleu de Prusse, tantôt noir-bleu si on le met près d’une couleur qui a un froid extrêmement chaud: orangé par exemple” (Instinctively. I finally came to consider colors as forces, to be assembled as inspiration dictates. Colors can be transformed by relation; a black becomes black-red if you put it next to a rather cold color like Prussian blue, blue-black if you put it alongside a color that has an extremely hot basis: orange, for example). “Neuvième Conversation,” in Henri Matisse with Pierre Courthion, Chatting with Henri Matisse: The Lost 1941 Interview, ed. Serge Guilbaut, trans. Chris Miller (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2013), 139, 333. Matisse made similar remarks in 1945 and 1946, which were published in Galerie Maeght’s catalogue for an exhibition titled Le noir est une couleur in Derrière le Miroir, no. 1 (December 1946), unpaginated. For analyses of these remarks, see Dominique Fourcade, Henri Matisse: Écrits et propos sur l’art, rev. ed. (Paris: Hermann, éditeurs des sciences et des arts, 1972), 202, 202n64; and Flam, Matisse on Art, 165–66, 291n5.

-

Yve-Alain Bois offers a similar analysis of Tulips and Oysters on a Black Background (February 11–12, 1943; Musée National Picasso-Paris), another painting by Matisse with a black, scratched background, in Yve-Alain Bois, Matisse and Picasso, exh. cat. (Paris: Flammarion, 1998), 142, 149. Delectorskaya assigns exact dates to this picture in Henri Matisse: Contre vents et marées, 469.

-

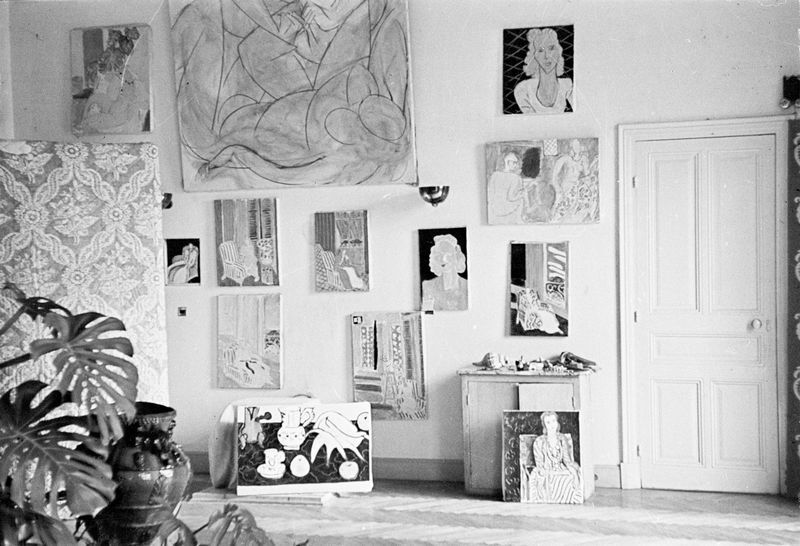

Moving counterclockwise from the painting hanging above the cabinet next to the door, these five works are: Jeune fille en robe blanche, porte noire (Young woman in a white dress, black door) (September 30, 1942; Private collection); Robe orientale violette sur la robe blanche, à la fenêtre (Purple oriental robe over the white dress, at the window) (October 2, 1942; Private collection); Jeune fille en rose dans un intérieur (Young woman in pink in an interior) (October 5, 1942; ISE Cultural Foundation, Tokyo); Jeune fille en robe blanche (Young woman in white dress) (September 28, 1942; Private collection); and Intérieur aux barres du soleil (Interior with bars of sun) (October 22–23, 1942; Musée Matisse, Le Cateau-Cambrésis). For a thorough analysis of this series, see Patrice Deparpe, “La floraison,” in Matisse: Paires et series, ed. Cécile Debray, exh. cat. (Paris: Éditions du Centre Pompidou, 2012), 221–29. Deparpe uses the same dates Delectorskaya assigns to these paintings in Henri Matisse: Contre vents et marées, 392–97, 406–7, 414–15.

-

Claudine Grammont calls these five paintings the Fenêtres in her entry on Monette Vincent, in Claudine Grammont, ed., Tout Matisse (Paris: Éditions Robert Laffont, 2018), 881.

-

“Je me suis engagé dans une certaine couleur des idées depuis longtemps—si elle supprime beaucoup de mois dans la finesse, l’exquis elle est remplie d’air pur. En somme j’ai commencé à labourer” (For a long time now I have been involved with a certain color of ideas—though it suppresses much of myself as regards delicacy and refinement, it is full of fresh air. In short, I am breaking new ground). Henri Matisse to Louis Aragon, September 1, 1942, quoted in Louis Aragon, “La Grande Songerie ou le retour de Thulé” (1945–1946), in his Henri Matisse, roman (Paris: Gallimard, 1998), 258. Translation from Aragon, Henri Matisse: A Novel, trans. Jean Stewart (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1972), 1:207. All subsequent translations from Aragon’s Henri Matisse, roman are from this source.

-

“Quand il a poussé la porte, et à l’improviste surprise la chambre, le fauteuil, c’est une profonde correspondence entre lui-même et ce lieu, qui seule peut expliquer l’enthousiasme qui le prend, le retient. . . . Par des moyens qui sont ceux de la peinture, Matisse exprime un sentiment qui ne pourrait être autrement exprimé; et comme il est peintre, c’est un pas en avant dans la connaissance de soi-même, de ce qu’il cherche. Bref, c’est une porte ouverte sur le monde matissien” (Only some deep-seated correspondence between himself and this place can explain the enthusiasm that seized and held him when he opened the door and caught the room, the armchair, unawares. . . . By means which are those of painting, Matisse expresses a feeling which could not be expressed otherwise; and since he is a painter, this is a step forward in the knowledge of himself, of what he is searching for. In brief, it is a door opening on to Matisse’s world). Aragon, “La Grande Songerie ou le retour de Thulé,” 278, 280, emphasis original. In an annotation to this passage, Aragon notes, “Matisse disait une certain couleur” (Matisse said a certain color), not “une certaine lumière des idées” (a certain light of ideas), as is indicated in the main text (278n2), emphasis original (trans. Stewart, 1:225).

-

Delectorskaya assigns this date to the painting in Henri Matisse: Contre vents et marées, 429.

-

For an analysis of this picture, see the catalogue entry by Claudine Grammont in Claudine Grammont, ed., Matisse: Collection Nahmad, exh. cat. (Paris: LienArt, 2020), 59. Grammont uses the same date Delectorskaya assigns to the picture in Henri Matisse: Contre vents et marées, 428.

-

Delectorskaya assigns this date to the painting in Henri Matisse: Contre vents et marées, 431.

-

“Le tableau n’est pas une glace qui reflète ce qui j’ai vécu en le faisant mais un objet puissant, fort, expressif qui est nouveau pour moi autant que pour quiconque.” Henri Matisse to Pierre Matisse, June 7, 1942, quoted in First Papers of Surrealism, 26. Flam translates this text as: “The painting is not a mirror reflecting what I experienced while creating it, but a powerful object, strong and expressive, which is as novel for me as for anyone else.” Flam, “On Transformations, 1942,” 143.

-

“Cher ami, je remasse les différentes photos que me demande la liste au sujet de la palette-d’objets, que vous avez faite il y a quatre ans” (My dear friend, I am collecting the various photos asked for in the list you made four years ago, referring to the palette of objects). Henri Matisse to Louis Aragon, May 4, 1946, quoted in the marginal annotation to Aragon, “La Grande Songerie ou le retour de Thulé,” 282n1 (trans. Stewart, 1:227).

-

“Cher Louis Aragon, j’ai pour vous une collection complète de ‘palette-d’objets.’ Vous serez satisfait” (Dear Louis Aragon, I have made a complete collection of the ‘palette of objects’ for you. You’ll be satisfied). Henri Matisse to Louis Aragon, May 16, 1946, quoted in the marginal annotation to Aragon, “La Grande Songerie ou le retour de Thulé,” 282n1 (trans. Stewart, 1:227).

-

While the curators who reproduced two views of this garment in Matisse: His Art and His Textiles: The Fabric of Dreams, ed. Hilary Spurling and Ann Dumas, exh. cat. (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2004), 103, do not tie it to any specific painting, its materials, striping, braiding, cut, and silhouette resemble those of the red-and-yellow robe in the Nelson-Atkins picture.

-

Sister Jacques-Marie (née Monique Bourgeois), who posed for Matisse in 1942–44, puts this term in quotation marks in her account of working in Matisse’s studio; Soeur Jacques-Marie, “Henri Matisse,” in “Models,” special issue, Grand Street, no. 50 (autumn 1994): 83.

-

Grammont is unable to assign a birth date to Vincent in her entry on the sitter in Tout Matisse, 881. However, see “Simone Monette Martin, 2016,” from the “United States, Residence Database, 1970–2024,” FamilySearch, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:6YJM-BXPD. She was born in September 1919 and died in January 2016. In a passenger list for the SS Washington sailing from Le Havre in 1946, Vincent is listed as working as “Sectr. UNO” in Washington, DC; see “List or Manifest of Alien Passengers for the United States,” July 19, 1946, from the “New York, New York Passenger and Crew Lists, 1909, 1925–1957” database, FamilySearch, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-L94V-7452, citing National Archives and Records Administration microfilm publication T715. In 1950, she married Georges-Henri Martin, who had been a journalist in Washington since 1941. See “Georges Henri Martin,” in the New York, U.S., Marriage License Indexes, 1907–2018, license no. 36412, December 29, 1950, digitized on Ancestry.com; and Alain Clavien, “Martin, Georges-Henri,” in Dictionnaire historique de la Suisse (DHS), July 31, 2007, https://hls-dhs-dss.ch/fr/articles/046088/2007-07-31. The author wishes to thank Meghan Gray, NAMA, for this research.

-

According to Vincent, Delectorskaya approached her on a bus on the hill in Cimiez in Nice toward the end of winter 1942. Vincent had been working for Matisse’s doctor at the time. See Monique Martin-Vincent, “Je continuerai à me souvenir avec tendresse,” in Hommage à Lydia Delectorskaya, exh. cat. (Le Cateau-Cambrésis: Musée Matisse, 1999), 23–27. This text is reproduced in Irina Antanova et al., Lydia D: Lydia Delectorskaya, muse et modèle de Matisse (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 2010), 200–201. In Matisse’s oeuvre, Vincent first appears in drawings dated July 1942. Three of these are reproduced in Delectorskaya, Henri Matisse: Contre vents et marées, 355.

-

The other is The Lute (former collection of Sidney Brody), which the artist painted on February 22 and 25, 1943. Delectorskaya assigns this date to the painting in Henri Matisse: Contre vents et marées, 475.

-

“Le modèle, pour les autres, c’est un renseignement. Moi, c’est quelque chose qui m’arrête” (The model, for other people, is a source of information. For me, it’s something that arrests me). Quoted in Aragon, “Matisse-en-France” (1942), in Louis Aragon, Henri Matisse, roman, 110 (trans. Stewart, 1:85).

-

“Ce modèle est pour moi un tremplin—c’est une porte que je dois enforcer pour accéder au jardin dans lequel je suis seul et si bien—même le modèle n’existe que pour ce qu’il me sert” (The model is a springboard for me—it’s a door which I must break down to reach the garden in which I am alone and so happy—even the model exists only for the use I can make of it). Quoted in a marginal annotation to Aragon, “La Grande Songerie ou le retour de Thulé,” 292n3 (trans. Stewart, 1:235).

-

While Grammont assigned the life dates of “(?– 1974)” to the collector (entry on Pellequer, in Grammont, Tout Matisse, 881), Anna Jozefacka provides the life dates as “before 1903–after 1973”; Anna Jozefacka, “Pellequer, Max,” The Modern Art Index Project, January 2015, revised by Lauren Rosati, December 2019, Leonard A. Lauder Research Center for Modern Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://doi.org/10.57011/ZXYW6521.

-

Matisse recorded the exchange in a journal entry dated June 12, 1943, Archives Matisse, Issy-les-Moulineaux, France: “Remis à Max Pellequer son tableau (‘Monette au collier d’ambre’)” (Given to Max Pellequer his painting [“Monette with the Amber Necklace”]). Translation by Kenneth Brummel. The author wishes to thank Anne Théry, Archives Henri Matisse, and MacKenzie Mallon, NAMA, for their assistance with this research.

-

“Vous m’avez permis d’acquérir un splendide tableau et vous l’avez fait avec une belle délicatesse, un tel chic qui vous avez voulu me donner l’impression que je vous l’avais acheté alors que je garde la sensation agréable que vous m’avez fait un veritable cadeau” (You enabled me to acquire a splendid painting, and you did it with such delicacy and chic, you wanted to give me the impression that I had bought it from you, whereas I still have the pleasant feeling that you gave me a real gift). Max Pellequer to Henri Matisse, June 24, 1943, Archives Matisse, Issy-les-Moulineaux, France; translation by Kenneth Brummel. According to Grammont, the painting mentioned in this passage is the Nelson-Atkins picture. Claudine Grammont to MacKenzie Mallon, NAMA, February 22, 2023, NAMA curatorial files. The author wishes to thank MacKenzie Mallon and Claudine Grammont, Musée Matisse, Nice, for their assistance with this research.

-

Max Pellequer to Henri Matisse, June 24, 1943, Archives Matisse. For two other discussions of this section of Pellequer’s letter, see Hélène Seckel-Klein’s entry on Henri Matisse in Picasso collectionneur, exh. cat. (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 1998), 172; and Bois, Matisse and Picasso, 133, 136. Lejard’s publication was Matisse: Seize peintures, 1939–1943 (Paris: Éditions du Chêne, 1943).

-

To date, scholars do not know which picture this is. For a discussion about this particular picture, see Bois, Matisse and Picasso, 133.

-

See Françoise Gilot, Matisse and Picasso: A Friendship in Art (New York: Doubleday, 1990), 29.

-

Matisse also repeats the gesture of Mme Moitessier’s hand in Woman in Blue (1937; Philadelphia Museum of Art). For a recent discussion of Matisse’s 1937 response to Picasso’s citation of Ingres in Woman with a Book, see Emily Talbot, “Ingres as Creative Catalyst: Picasso’s Woman with a Book,” in Christopher Riopelle, Emily Talbot, and Susan L. Siegfried, Picasso Ingres: Face to Face, exh. cat. (London: National Gallery Global, 2022), 40–41.

-

See Exposition d’oeuvres récentes de Picasso, exh. cat. (Paris: Paul Rosenberg, 1936), unpaginated, as no. 6, Femme assise tenant un livre; and Les maîtres de l’Art Indépendant 1895–1937, exh. cat. (Paris: Arts et Métiers Graphiques, 1937), 106, as no. 4, Femme assise tennant une livre.

-

See Christian Zervos, “Fait social et vision comique,” Cahiers d’Art 10, nos. 7–10 (1935): 147; and Picasso, 1930–1935 (Paris: Éditions “Cahiers d’Art,” 1936), 11.

-

Girl before a Mirror (March 14, 1932; Museum of Modern Art, New York) is another 1932 painting in which Picasso transforms the breasts and abdomen of a female subject into a testicle and penis. For a recent discussion of Picasso’s fusion of male and female signifiers in the distorted anatomies of figures in his 1932 paintings, see Achim Borchardt-Hume, “The Painter of Today,” in Achim Borchardt-Hume and Nancy Ireson, eds., Picasso 1932: Love Fame Tragedy, exh. cat. (London: Tate Publishing, 2018), 21.

-

For three discussions that outline the differences in the 1920s and 1930s between Matisse’s carefully harmonized color system, based on how objects appear in the natural world, and Picasso’s more intellectualized, non-naturalistic approach to color, see Linda Nochlin, “Picasso’s Color: Schemes and Gambits,” in “Picasso,” special issue, Art in America 68, no. 10 (December 1980): 106–7; Bois, Matisse and Picasso, 72, 74; and Rosalind Krauss, “Color War: Picasso’s Matisse Period,” in Self and History: A Tribute to Linda Nochlin, ed. Aruna D’Souza (London: Thames and Hudson, 2001), 147–49, 151.

-

According to Philip Conisbee, Portrait de Madame Senonnes, née Marie-Geneviève-Marguerite Marcoz, later Vicomtesse de Senonnes, is one of Ingres’s greatest portraits. See his catalogue entry on the painting in Gary Tinterow and Philip Conisbee, Portraits by Ingres: Image of an Epoch, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1999), 150.

-

See, for example, Aragon, “Matisse-en-France,” 116n3, 133n1, 151n3 (trans. Stewart, 1:89n1, 1:125n1, as well as a marginal annotation and a 1968 note by Aragon on 1:105), and Aragon, “La Grande Songerie ou le retour de Thulé,” 277n1, 297n1 (trans. Stewart, see Aragon’s 1946 annotation, reinserted in 1966, on 1:223; and his 1967 annotation on 1:239).

-

Aragon articulates this argument in different passages of “Matisse-en-France,” 98–99, 143–44, 176 (trans. Stewart, 1:72–73, 1:115–16, 1:144), and “La Grande Songerie ou le retour de Thulé,” 298, 302 (trans. Stewart, 1:240, 1:242, 1:244).

-

“Ainsi se fait en lui la synthèse de la France. . . . Le Nord et le Midi. La raison et la déraison. L’imitation et l’invention. La brume et le soleil. L’inspiration et la réalité. Mais les contrastes sont dans l’homme, son attitude, ce qu’il dit: l’oeuvre déjà est équilibre des contraires, la France” (And so he embodies the synthesis of France, North and South. Reason and unreason. Imitation and invention. Sunlight and mist. Inspiration and reality. But these contrasts are in the man, in his attitude, in what he says: his work has achieved a balance of opposites, it is France). See Aragon, “Matisse-en-France,” 110 (trans. Stewart, 1:116).

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Diana M. Jaskierny and John Twilley, “Henri Matisse, Seated Young Woman with an Amber Necklace, December 1942,” technical entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.802.2088.

MLA:

Jaskierny, Diana M. and John Twilley. “Henri Matisse, Seated Young Woman with an Amber Necklace, December 1942,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.802.2088.

With blocks of color and scumbledscumble: A thin layer of opaque or semi-opaque paint that partially covers and modifies the underlying paint. modeling, Henri Matisse’s Seated Young Woman with an Amber Necklace stylistically bridges the artist’s earlier portraiture and the collages or “cut-outs” created at the end of his life. The painting was executed on a plain-weave canvasplain weave: A basic textile weave in which one weft thread alternates over and under the warp threads. Often this structure consists of one thread in each direction, but threads can be doubled (basket weave) or tripled to create more complex plain weave. Plain weave is sometimes called tabby weave., corresponding in size to a French standard canvasstandard-format supports: Commercially prepared supports available through art suppliers, which gained popularity in the nineteenth century during the industrialization of art materials. Available in three formats figure (portrait), paysage (landscape), and marine (marine), these were numbered 1 through 120 to indicate their size. For each numbered size, marine and paysage had two options available: a larger format (haute) and smaller (basse) format. no. 10 figure,1David Bomford, Jo Kirby, John Leighton, and Ashok Roy, Art in the Making: Impressionism (London: Yale University Press, 1991), 46. and retains its original dimensions, with pronounced secondary cuspingcusping: A scalloped pattern along the canvas edges that relates to how the canvas was stretched. Primary cusping reveals where tacks secured the canvas to the support while the ground layer was applied. Secondary cusping can form when a pre-primed canvas is re-stretched by the artist prior to painting. along the left and right sides.2There is one set of tack holes between the canvas and stretcher. There are a few additional holes on the canvas and stretcher that, based on the cusping, were likely where the tacks were originally placed. The painting is mounted to a commercially made, five-member wooden stretcherstretcher: A wooden structure to which the painting’s canvas is attached. Unlike strainers, stretchers can be expanded slightly at the joints to improve canvas tension and avoid sagging due to humidity changes or aging., possibly original to the painting. The commercially prepared canvas has a thin and even, white or slightly off-white ground layerground layer: An opaque preparatory layer applied to the support, either commercially or by the artist, to prevent absorption of the paint into the canvas or panel. See also priming layer. of lead white that extends over the tacking marginstacking margins: The outer edges of canvas that wrap around and are attached to the stretcher or strainer with tacks or staples. See also tacking edge.. A second lead white ground layer of similar color, likely put on by the artist, appears to have been applied across the majority of the picture planepicture plane: The two-dimensional surface where the artist applies paint. but is not present on the tacking margins. This upper ground layer remains visible in many areas of the painting and may have been added to cover an earlier paint application that was painted directly on the first ground layer. In the sitter’s face, the upper ground layer and lower layers appear to have been abraded or scraped away prior to the painting’s completion, evident by canvas weave caps visible through the thin paint application (Fig. 9).

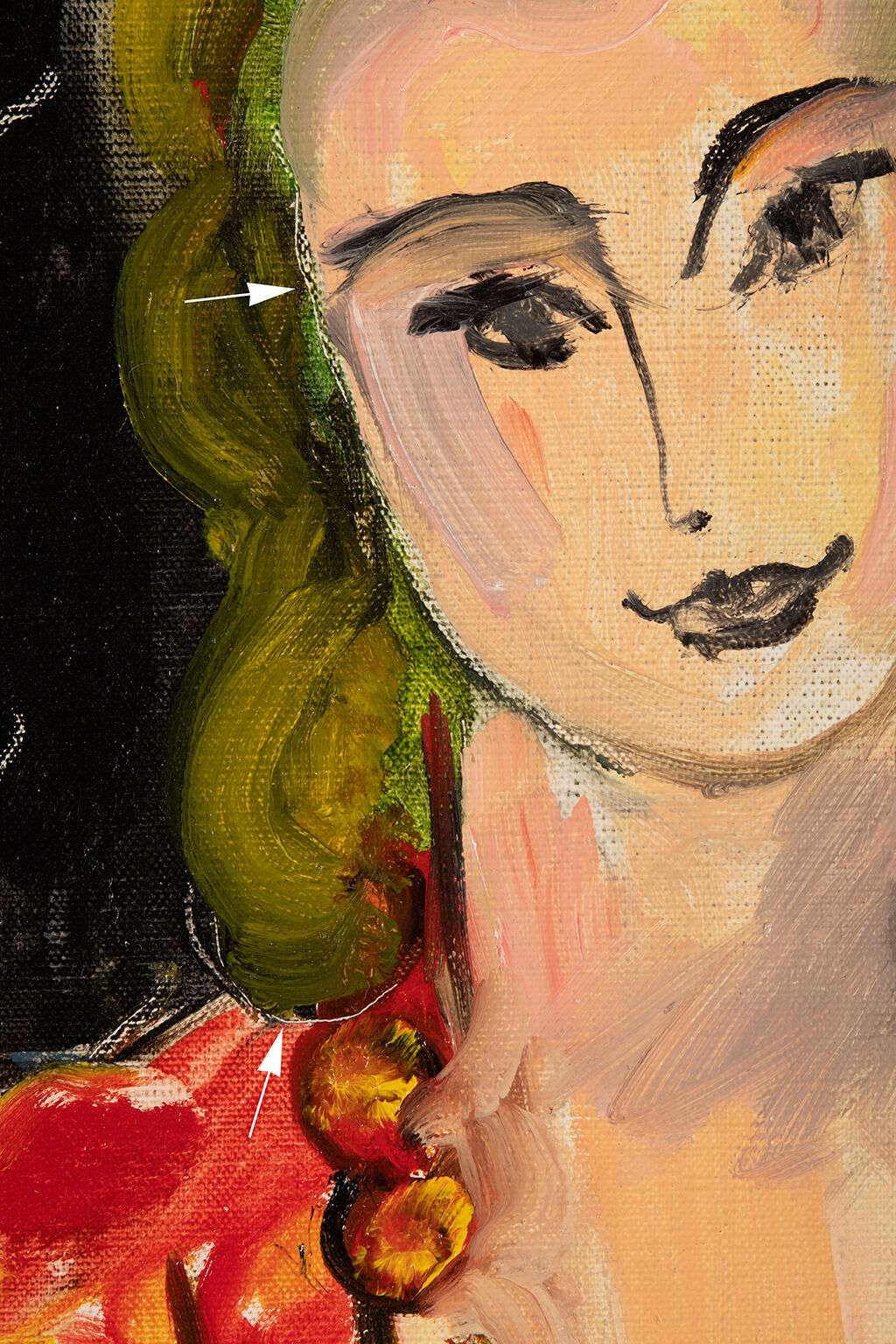

Fig. 9. Detail photograph illustrating the abraded ground layer and the green lower layer of the hair and wet-into-wet paint application in the face, Seated Young Woman with an Amber Necklace (1942)

Fig. 9. Detail photograph illustrating the abraded ground layer and the green lower layer of the hair and wet-into-wet paint application in the face, Seated Young Woman with an Amber Necklace (1942)

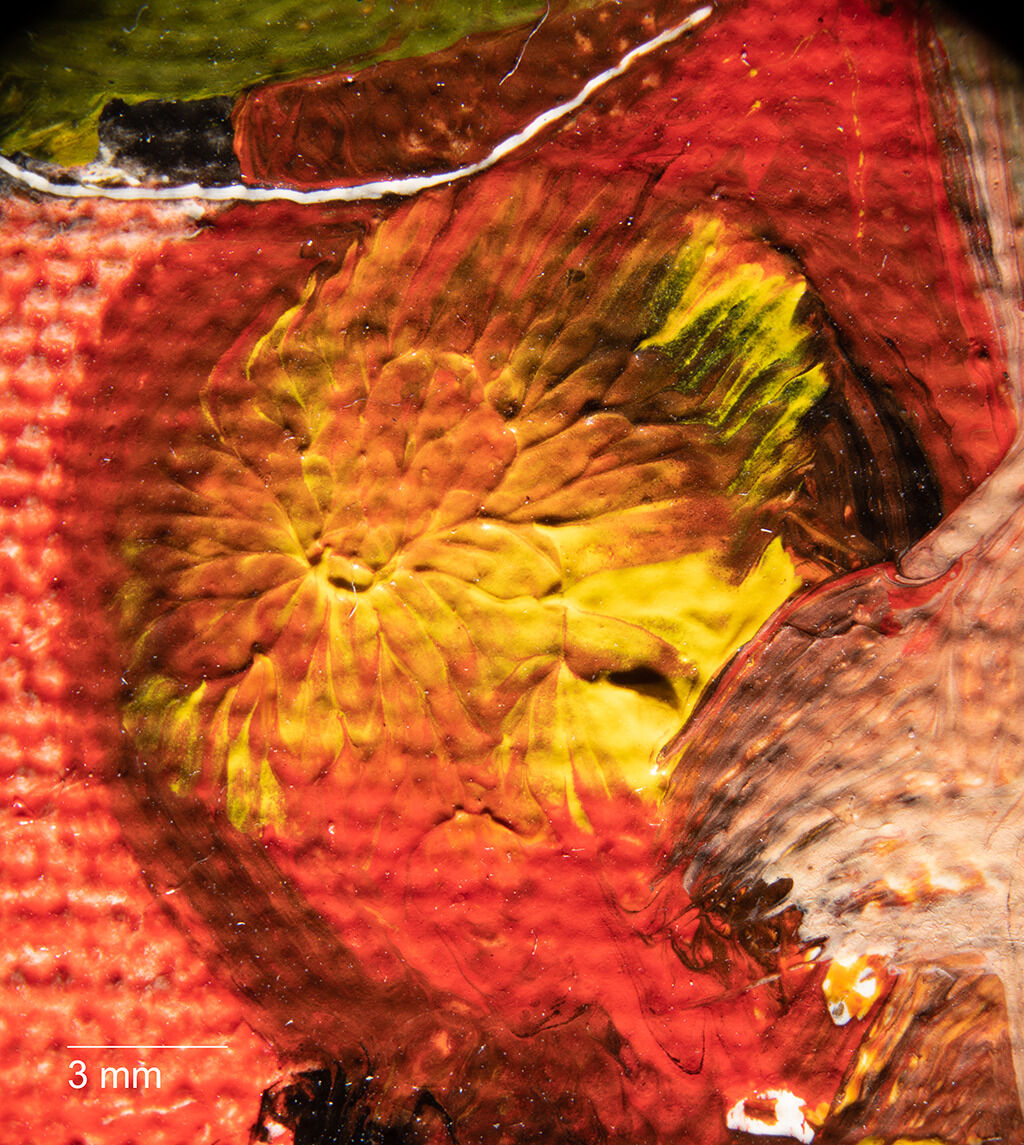

Fig. 10. Photomicrograph of a crack in the recto turnover edge revealing blue and yellow paint beneath a second ground layer, Seated Young Woman with an Amber Necklace (1942)

Fig. 10. Photomicrograph of a crack in the recto turnover edge revealing blue and yellow paint beneath a second ground layer, Seated Young Woman with an Amber Necklace (1942)

Fig. 11. Photomicrograph of a red, yellow, and blue thinly painted outline along the proper left side of the chair, Seated Young Woman with an Amber Necklace (1942)

Fig. 11. Photomicrograph of a red, yellow, and blue thinly painted outline along the proper left side of the chair, Seated Young Woman with an Amber Necklace (1942)

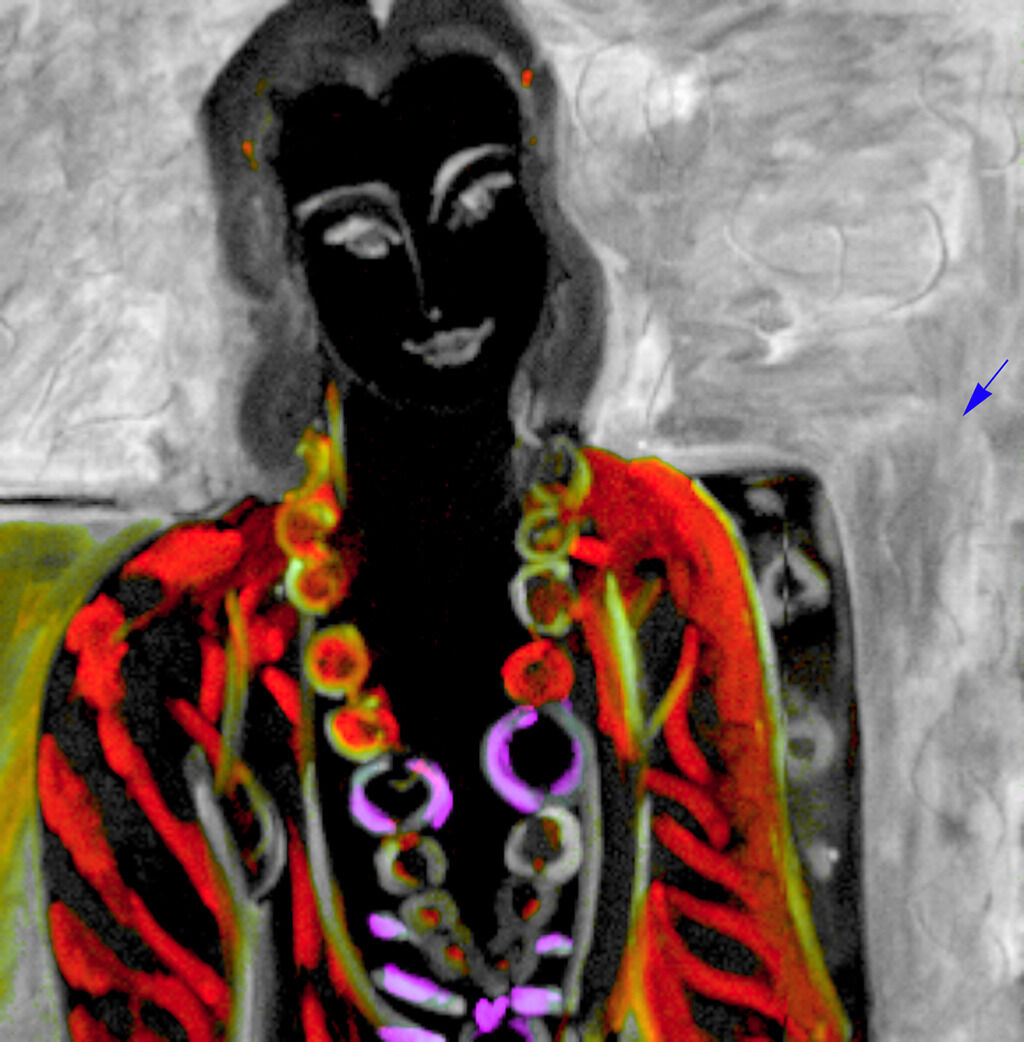

Fig. 12. Detail photograph of sketched red and yellow lines for the forearm (indicated by blue arrows) and wet-over-wet outlines in the outer Persian robe (indicated by green arrows), Seated Young Woman with an Amber Necklace (1942)

Fig. 12. Detail photograph of sketched red and yellow lines for the forearm (indicated by blue arrows) and wet-over-wet outlines in the outer Persian robe (indicated by green arrows), Seated Young Woman with an Amber Necklace (1942)

Working quickly, Matisse appears to have then alternated between painting the chair and the figure, making it difficult to determine the precise order of paint application. While the majority of the composition consists of wet-over-wetwet-over-wet: An oil painting technique which involves drawing a stroke of one color across the wet paint of another color. brushwork, there are also examples of wet-over-drywet-over-dry: An oil painting technique that involves layering paint over an already dried layer, resulting in no intermixing of paint or disruption to the lower paint strokes.. The purple stripes of the inner gown were applied after the lower pale gray-blue color of the gown had dried. Similarly, the black stripes here were applied over the already dried purple stripes (Fig. 13). This differs from many of the other black outlines, such as the those around the arms and outer Persian robe in Figure 12, which were incorporated into the composition when the surrounding or underlying paint was still wet.

Fig. 13. Photomicrograph of wet-over-dry purple and black stripes on the inner gown, Seated Young Woman with an Amber Necklace (1942)

Fig. 13. Photomicrograph of wet-over-dry purple and black stripes on the inner gown, Seated Young Woman with an Amber Necklace (1942)

Fig. 14. Photomicrograph of necklace bead in raking light, Seated Young Woman with an Amber Necklace (1942)

Fig. 14. Photomicrograph of necklace bead in raking light, Seated Young Woman with an Amber Necklace (1942)

Mapping of the chemical elements associated with the pigments was carried out on a detail of the composition covering the sitter’s head and upper torso that contains representative examples of all the colors. By this means, a partial list of pigments was identified that includes lead white, zinc white, cadmium red, small amounts of iron-based red possibly from an earth color, chrome yellow, cadmium yellow, and cobalt arsenate violet (possibly of two varieties). A synthetic organic pigment containing chlorine was employed in red-brown passages. Barium sulfate was commonly encountered as a colorless filler. The infrared behavior, observed throughout the near- and shortwave infrared regions of the spectrum, confirms the presence of carbon black. Phosphorous, associated with only part of these blacks, indicates that two varieties are present, one of which is bone black. Many additional pigment species may be present, including blue that was visible with the microscope but not represented by any mappable elements.

The distribution of calcium is particularly interesting because it appears to correspond to variations in application of the background black that are apparent visually and to reveal an alternative form of chair with a rounded wing adjacent to the sitter’s proper left shoulder. Figure 15 depicts these features in the distribution of calcium (shown in white), alongside selenium associated with cadmium red and cobalt associated with cobalt violet.

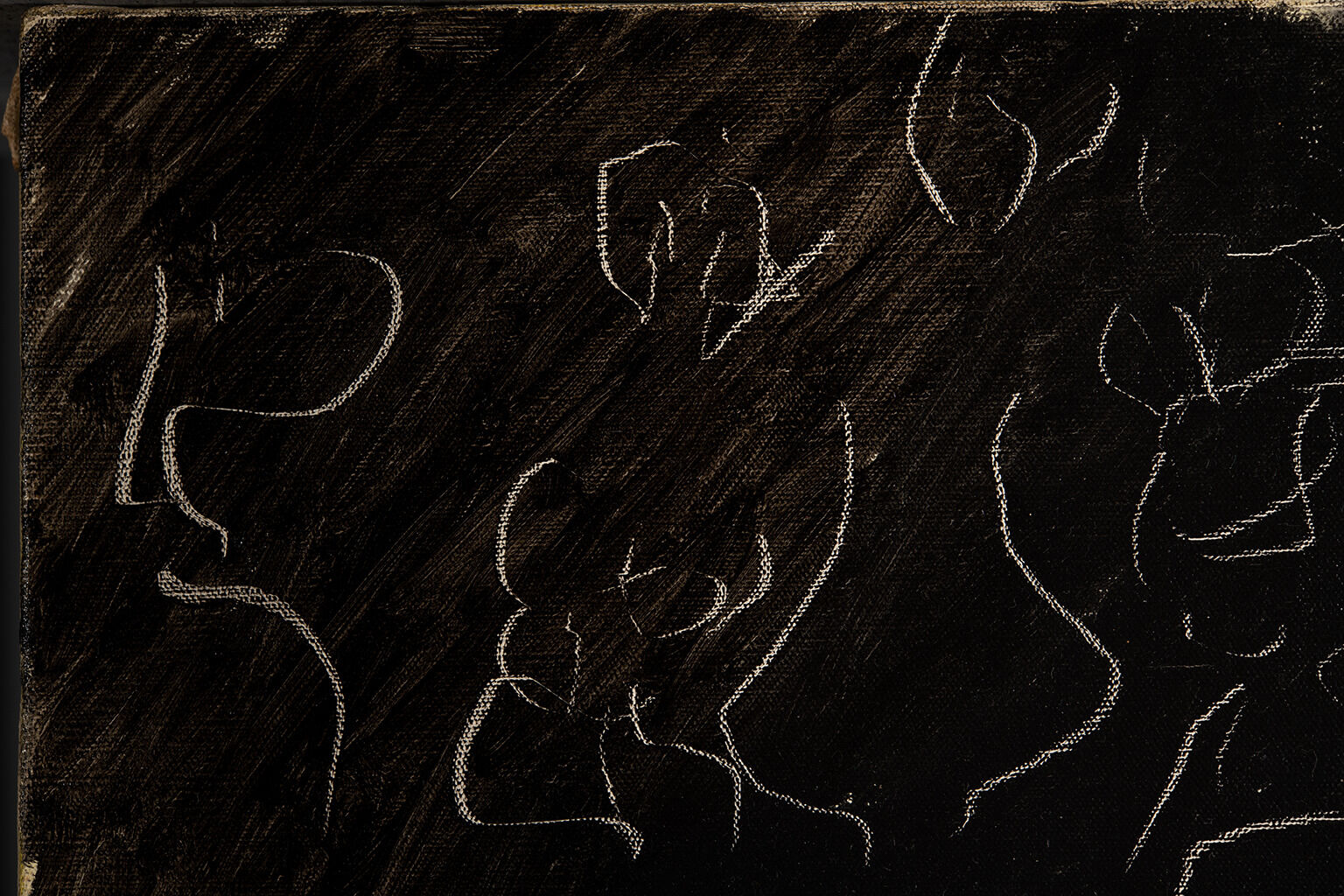

Fig. 16. Detail photograph of sgraffito lines in the upper left background, Seated Young Woman with an Amber Necklace (1942)

Fig. 16. Detail photograph of sgraffito lines in the upper left background, Seated Young Woman with an Amber Necklace (1942)

Fig. 17. Detail photograph of sgraffito lines around the figure’s face and hair (indicated by white arrows), Seated Young Woman with an Amber Necklace (1942)

Fig. 17. Detail photograph of sgraffito lines around the figure’s face and hair (indicated by white arrows), Seated Young Woman with an Amber Necklace (1942)

Notes

-

David Bomford, Jo Kirby, John Leighton, and Ashok Roy, Art in the Making: Impressionism (London: Yale University Press, 1991), 46.

-

There is one set of tack holes between the canvas and stretcher. There are a few additional holes on the canvas and stretcher that, based on the cusping, were likely where the tacks were originally placed.

-

In addition to the paint found within the turnover cracks, smudges of similar paint remain visible on the tacking margin.

-

Similarly, the Art Institute of Chicago found that Matisse wiped away or scraped paint as he made alterations. On Girl in Yellow and Blue with a Guitar, remnants of the scraped paint remain visible, while in the Nelson-Atkins painting, the second ground layer has covered the earlier paint. Kristin Hoermann Lister, with contributions by Inge Fiedler, “Cat. 46, Girl in Yellow and Blue with a Guitar, 1939: Technical Report,” in Matisse Paintings, Works on Paper, Sculpture, and Textiles at the Art Institute of Chicago (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2017), para 8, https://publications.artic.edu/matisse/reader/works/section/86/86_anchor.

-

No lower composition was revealed through infrared reflectography, transmitted infrared photography, transmitted light, or x-radiography, further indicating that any possible past composition was likely removed. Elemental mapping (MA-XRF) and short-wave infrared imaging showed the same absence of features not related to the present scene.

-

“Colors can be transformed by relation; a black becomes red-black if you put it next to a rather cold color like Prussian blue, blue-black if you put it alongside a color that has an extremely hot basis: orange, for example. And from that point on, I began working with a palette especially composed for each painting, while I was working on it, which meant I could eliminate one of the primordial colors, like a red or a yellow or a blue, from my painting. And that goes right against neoimpressionist theory, which is based on optical mixing and color constraints, each color having its reaction. For example: if there is red, there has to be a green.” “Neuvième Conversation,” in Henri Matisse and Pierre Courthion, Chatting with Henri Matisse: The Lost 1941 Interview, ed. Serge Guilbaut, trans. Chris Miller (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2013), 139̵–40.

-

While the inner gown does have a pale gray-blue color, its light tone is nearly imperceptible in standard gallery lighting and prevents it from competing with the composition’s predominant primary colors of red and yellow and the predominant secondary colors of green and purple.

-

Similar marks were found on Girl in Yellow and Blue with a Guitar (1939; The Art Institute of Chicago). Hoermann Lister, “Cat. 46, Girl in Yellow and Blue with a Guitar, 1939: Technical Report,” para 35.

-

Forrest R. Bailey, December 13, 1986, treatment report, NAMA conservation file, 2015.13.13.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, with Pegeen Blank, “Henri Matisse, Seated Young Woman with an Amber Necklace, December 1942,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.802.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M., with Pegeen Blank, “Henri Matisse, Seated Young Woman with an Amber Necklace, December 1942,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.802.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, with Pegeen Blank, “Henri Matisse, Seated Young Woman with an Amber Necklace, December 1942,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.802.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M., with Pegeen Blank, “Henri Matisse, Seated Young Woman with an Amber Necklace, December 1942,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.802.4033.

Purchased from the artist by Max Pellequer (before 1903–after 1973), Paris, by June 12, 1943–after 1973, as Monette au collier d’ambre [1];

Inherited by his nephew, Georges Pellequer (d. 2013), Paris, after 1973–August 30, 1977 [2];

Purchased from Pellequer by Galerie Beyeler, Basel, 1977–November 11, 1980 [3];

Purchased from Beyeler by Giuseppe Nahmad, Geneva, 1980–at least March 1981 [4];

With M. Knoedler Zürich AG, Zürich, stock no. 890K, as Femme assise sur fond noir [5];

Fredrik Roos (1951–91), Stockholm, Paris, London, by November 1984–at least January 6, 1985 [6];

Purchased at Impressionist and Modern Paintings and Sculpture (Part I), Christie’s, New York, November 19, 1986, lot 53, by Marion (née Helzberg, 1931–2013) and Henry (1922–2019) Bloch, Shawnee Mission, KS, 1986–June 15, 2015;

Their gift to The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 2015.

Notes

[1] According to a note in Matisse’s journal, dated June 12, 1943, “Remis à Max Pellequer son tableau (Monette au collier d’ambre)” (Given to Max Pellequer his painting [Monette with an amber necklace]). See Archives Henri Matisse, Issy les Moulineaux, France. The word “son” (his) indicates that it was purchased by Pellequer ahead of time. In a related letter from Pellequer to Matisse, dated June 24, 1943, also in the Archives Henri Matisse, Pellequer mentioned this painting: “Vous m’avez permis d’acquerir un splendide tableau et vous l’avez fait avec une belle delicatesse, un tel chic qui vous avez voulu me donner l’impression que je vous l’avais achete alors que je garde la sensation agreable que vous m’avez fait un veritable cadeau” (You enabled me to acquire a splendid painting, and you did it with such delicacy and chic, you wanted to give me the impression that I had bought it from you, whereas I still have the pleasant feeling that you gave me a real gift). With thanks to Anne Théry, Archives Henri Matisse, for assistance with this research, and to Kenneth B. Brummel, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, Aotearoa New Zealand, for his translations of the letters.

[2] Georges inherited his uncle’s collection; see Anna Jozefacka, “Pellequer, Max,” The Modern Art Index Project (January 2015; revised by Lauren Rosati October 2018, December 2019), Leonard A. Lauder Research Center for Modern Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://doi.org/10.57011/ZXYW6521.

[3] See correspondence from Dr. Simon Crameri, Fondation Beyeler, to MacKenzie Mallon, the Nelson-Atkins, April 29, 2015, NAMA curatorial files.

[4] See Matisse, exh. cat. (Tokyo: National Museum of Modern Art, 1981), 115, 213. Giuseppe “Joe” Nahmad (1932–2012) was a dealer specializing in Impressionist, Post-Impressionist, and Modern art.

[5] According to a label on the back of the painting. No date is indicated.

[6] According to a label on the back of the painting. Fredrik Roos was a collector with apartments in Stockholm, Paris, and London. In 1986, he purchased a building in Malmö and two years later founded a museum, Rooseum Center for Contemporary Art, which closed in 2006.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Henri Matisse, Seated Young Woman with an Amber Necklace, December 1942,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.802.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Henri Matisse, Seated Young Woman with an Amber Necklace, December 1942,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.802.4033.

Henri Matisse, Monette, 1942, charcoal on paper, 20 x 15 5/16 in. (51 x 39 cm), private collection.

Henri Matisse, Seated Young Woman in a Persian Dress, 1942, oil on canvas, 16 15/16 x 22 in. (43 x 56 cm), Musée Picasso-Paris, MP2017-27.

Henri Matisse, Red Persian Dress with Black Door, September 30, 1942, oil on canvas, 24 x 14 15/16 in. (61 x 38 cm), location unknown.

Henri Matisse, Monette Vincent, November 1942, charcoal and stump on paper, 15 7/10 x 12 in. (40 x 30.5 cm), private collection.

Henri Matisse, Seated Young Woman in a Gray Dress, November 1942, oil on canvas, 18 1/4 x 15 in. (46.3 x 38.2 cm), The Nahmad Collection, Monaco.

Henri Matisse, The Lute, February 1943, oil on canvas, 23 7/16 x 31.5/16 in. (59.5 x 79.5 cm), private collection.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Henri Matisse, Seated Young Woman with an Amber Necklace, December 1942,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.802.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Henri Matisse, Seated Young Woman with an Amber Necklace, December 1942,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.802.4033.

Matisse: Huiles, Gouaches, Découpées, Dessins, Sculptures, Galerie Beyeler, Basel, June–September 1980, no. 34, as Femme assise sur fond noir.

Matisse: Oleos, Dibujos, Gouaches Découpées, Esculturas y Libros, La Fundación Juan March, Madrid, October–December 1980, no. 35, as Mujer sentada con fondo negro.

Matisse, National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, March 30–May 17, 1981; National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto, May 26–July 19, 1981, no. 90, as Seated Woman against a Black Background (Femme assise sur fond noir).

Henri Matisse, Moderna Museet, Stockholm, November 3, 1984–January 6, 1985, no. 66, as Femme assise sur fond noir (Sittande kvinna mot svart bakgrund).

Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, June 9–September 9, 2007, no. 30, as Woman Seated before a Black Background (Femme assise sur fond noir).

References

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Henri Matisse, Seated Young Woman with an Amber Necklace, December 1942,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.802.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Henri Matisse, Seated Young Woman with an Amber Necklace, December 1942,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.802.4033.

Matisse: Huiles, Gouaches, Découpées, Dessins, Sculptures, exh. cat. (Basel: Galerie Beyeler, 1980), unpaginated, (repro.).

Matisse: Oleos, Dibujos, Gouaches Découpées, Esculturas y Libros, exh. cat. (Madrid: Fundación Juan March, 1980), unpaginated, (repro.), as Mujer sentada con fondo negro.

Matisse, exh. cat. (Tokyo: National Museum of Modern Art, 1981), 115, 213, (repro.).

Henri Matisse, exh. cat. (Stockholm: Moderna Museet, 1984), 39, (repro.).

Impressionist and Modern Paintings and Sculpture, Part I (New York: Christie’s, 1986), 116–17, (repro.).

Lydia Delectorskaya, Henri Matisse: Contre vents et marées; Peinture et livres illustrés de 1939 à 1943 (Paris: Éditions Irus et Vincent Hansma, 1996), 414, 429, 551, (repro.), as Robe persane, gros collier d’ambre.

Hilary Spurling, Matisse the Master: A Life of Henri Matisse: The Conquest of Colour, 1909–1954 (New York: Albert A. Knopf, 2005), 387.

“Inaugural Exhibitions Celebrate Kansas City,” Member Magazine (Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (Fall 2006): 2–3, (repro.).

Bobbie Leigh, “Magnificent Obsession,” Art and Antiques 29, no. 6 (June 2006): 62, (repro.), as Woman Seated Before a Black Background.

Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 12, 150–53, 162, (repro), as Woman Seated before a Black Background (Femme assise sur fond noir).

Steve Paul, “Pretty Pictures: Marion and Henry Bloch’s collection of superb Impressionist masters,” Panache 4, no. 3 (Fall 2007): 20, 22, 24, (repro.), as Woman Seated Before a Black Background.

Impressionist and Modern Art (New York: Christie’s, November 1, 2011), 37, (repro.).

Cécile Debray, ed., Matisse: Paires et séries, exh. cat. (Paris: Éditions du Centre Pompidou, 2012), 221, (repro.).

Claudine Grammont, ed., Tout Matisse (Paris: Éditions Robert Laffont, 2018), 881, as Robe persane, collier d’ambre.

Saul Nelson, Never Ending: Modernist Painting Past and Future (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2024), 180, (repro.), as Woman Seated Before a Black Background.