![]()

Alfred Sisley, The Lock of Saint-Mammès, 1885

| Artist | Alfred Sisley, English, born Paris, 1839–99 |

| Title | The Lock of Saint-Mammès |

| Object Date | 1885 |

| Alternate and Variant Titles | L’ecluse de Saint-Mammès; Le Loing à Saint-Mammès |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (Unframed) | 15 x 21 1/2 in. (38.1 x 54.6 cm) |

| Signature | Signed and dated lower right: Sisley. 85 |

| Credit Line | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Gift of Henry W. and Marion H. Bloch, 2015.13.24 |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Alfred Sisley, The Lock of Saint-Mammès, 1885,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.662.5407.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Alfred Sisley, The Lock of Saint-Mammès, 1885,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.662.5407.

Canal and river locks were a source of perennial fascination for “English Impressionist” Alfred Sisley, so called because of his English heritage.1Though the artist was born in Paris, his parents, William (1799–1879) and Felicia (née Sell, 1808–66) Sisley, hailed from the United Kingdom. This ancestry earned him the moniker made famous by Vivienne Couldrey’s monograph, Alfred Sisley: The English Impressionist (Newton Abbot, UK: David and Charles, 1992). Between the mid-1870s and early 1890s, he created numerous oil and pastel renderings of locks at Bougival, Moret-sur-Loing, Ouzouer-sur-Trézée, and Saint-Mammès in France, as well as East Molesey in England.2See, for example, Sylvie Brame and François Lorenceau, Alfred Sisley: Catalogue critique des peintures et des pastels (Lausanne: La Bibliothèque des arts, 2021), cats. 68, 151, 153, 492, 493, 657, 658, 800, 917, and P46, pp. 62, 89–90, 201, 252, 300, 341, and 395. This interest may have stemmed, in part, from Sisley’s early exposure to John Constable’s (1776–1837) paintings of locks, which he discovered while living in London from 1857 to 1860.3On Sisley’s debt to Constable, see MaryAnne Stevens, “Un peintre entre deux traditions,” in Alfred Sisley: Poète de l’impressionnisme, exh. cat. (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 2002), 53. As Stevens notes, one painting that Sisley had opportunity to see was Constable’s A Boat Passing a Lock, 1826, oil on canvas, 40 x 50 in. (101.6 x 127 cm), Royal Academy of Arts, London, 03/923. Some of Sisley’s lock pictures offer close-range views of weirsweir: A dam constructed on a canal or navigable river to retain the water and regulate its flow., sluice gatessluice: A wood or masonry structure for impounding the water of a river or canal, provided with an adjustable gate or gates by which the volume of water is regulated or controlled., and towpathstowpath: A path by the side of a canal or navigable river for use in towing., while others show the locks from afar, largely obscuring their control mechanisms. The Nelson-Atkins landscape is one of the latter. Completed while Sisley was living in the town of Sablons, it depicts the eastern shore of the Canal du Loing in Saint-Mammès, just south of where it empties into the Seine River. During the 1880s, Sisley produced a significant body of work devoted to the Saint-Mammès waterfront, which earned him many accolades. Art critic Gustave Geffroy dubbed Sisley the “charming poet” of Saint-Mammès in an 1883 exhibition review, and symbolist writer Henri de Régnier paid tribute to Sisley’s images of the Loing, Marne, and Seine rivers in a 1918 poem.4For Geffroy’s description of “le paisible Saint-Mammès dont Sisley est le poète charmant” (the peaceful Saint-Mammès of which Sisley is the charming poet), see Gustave Geffroy, “Chronique: A. Sisley,” La Justice, June 23, 1883, 1. For the poem, see Henri de Régnier, “Médaillons de peintres,” Revue des Deux Mondes 48, no. 3 (December 1, 1918): 619.

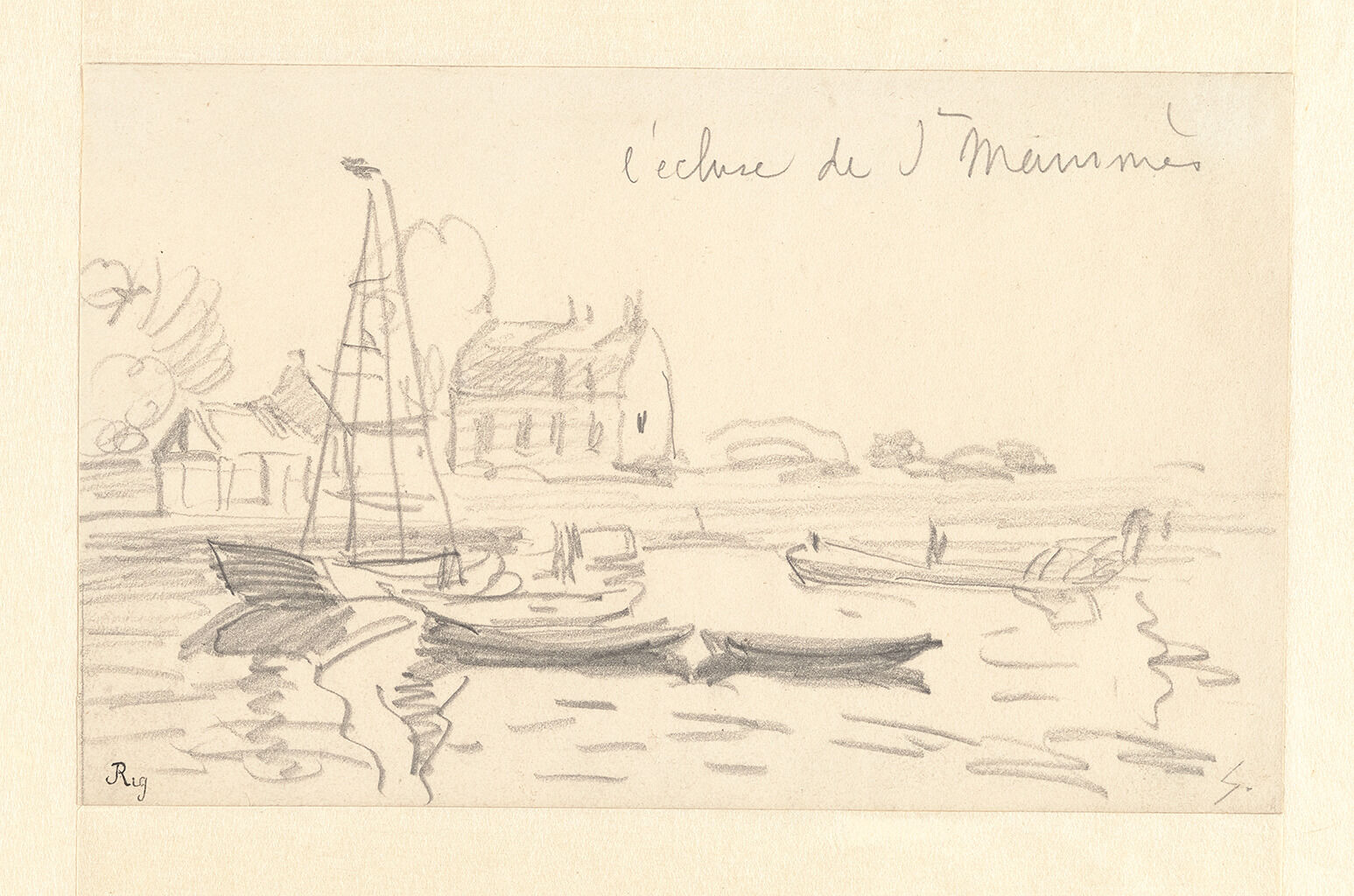

Fig. 2. Alfred Sisley, The Saint-Mammès Lock (Department Seine-et-Marne, France) [L’Écluse de Saint-Mammès (Département de Seine-et-Marne, France)], ca. 1885, black chalk on paper, 5 1/16 x 8 1/4 in. (12.9 x 21 cm), Collection Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam. Loan: Stichting Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen 1940 (former collection Koenigs). Photographer: Studio Tromp

Fig. 2. Alfred Sisley, The Saint-Mammès Lock (Department Seine-et-Marne, France) [L’Écluse de Saint-Mammès (Département de Seine-et-Marne, France)], ca. 1885, black chalk on paper, 5 1/16 x 8 1/4 in. (12.9 x 21 cm), Collection Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam. Loan: Stichting Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen 1940 (former collection Koenigs). Photographer: Studio Tromp

Fig. 3. Alfred Sisley, Barges, 1885, oil on canvas, 21 9/16 x 15 3/16 in. (54.7 x 38.5 cm), private collection. Photo © Christie’s Images / Bridgeman Images

Fig. 3. Alfred Sisley, Barges, 1885, oil on canvas, 21 9/16 x 15 3/16 in. (54.7 x 38.5 cm), private collection. Photo © Christie’s Images / Bridgeman Images

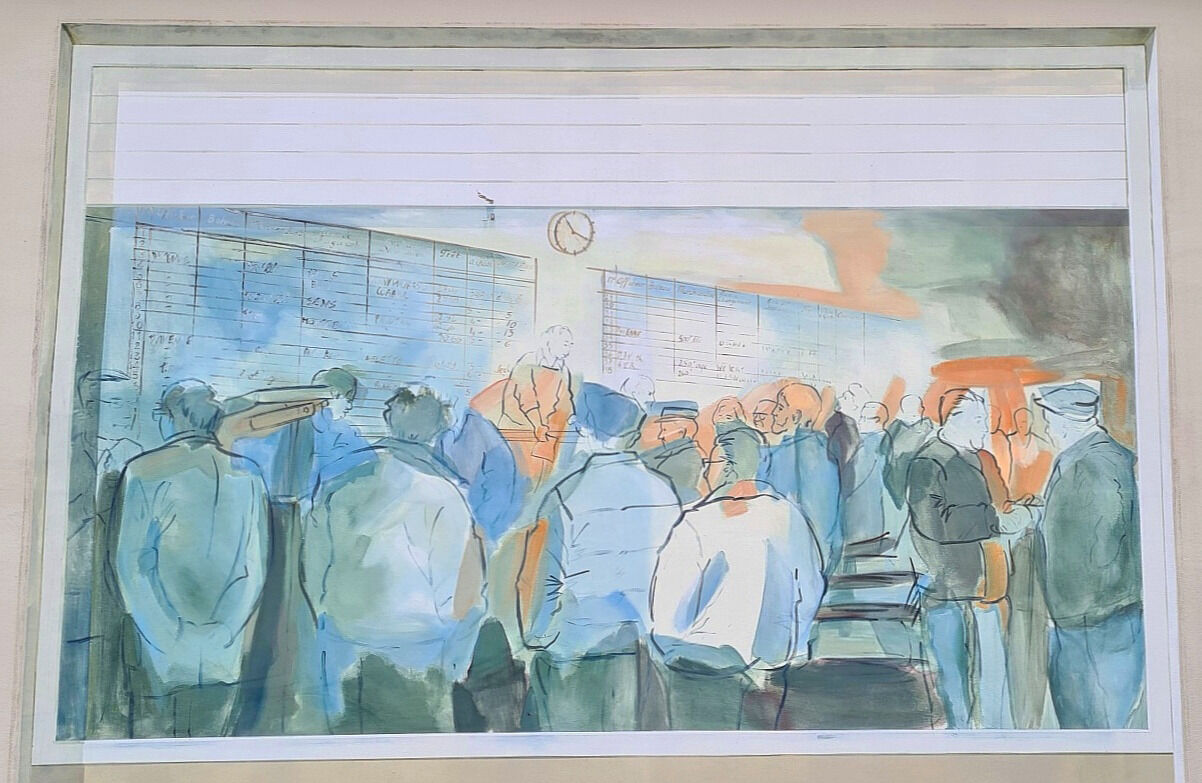

Over time, the larger house ceased to serve as a dwelling, and in 1936 the National Office of Shipping opened a bourse d’affrètement (freight exchange office) on its ground floor as part of a countrywide effort to better regulate river transport. Previously, local bargeman had been forced to negotiate deals through brokers, in meetings that often took place at bars and involved bribes, but now they could accept loads for transport at this government bureau.19See Mairie de Saint-Mammès, “La Bourse d’Affrètement.” The bourse remained a hub of economic activity until December 31, 1999, when France did away with the then-outdated system and closed all remaining exchange offices.20Dominique Malécot, “La libéralisation du transport fluvial entre dans les faits le 1er janvier,” Les Échos, December 24, 1999, https://www.lesechos.fr/1999/12/la-liberalisation-du-transport-fluvial-entre-dans-les-faits-le-1er-janvier-783331 On the wall outside the now-vacant building—the same wall that divides The Lock of Saint-Mammès into two horizontal registers—a mural painting by the Lyonnais cooperative CitéCréation commemorates the bourse (Fig. 5).21For more on CitéCréation, see their website at https://citecreation.fr Crafted using the technique of marouflagemarouflage: A technique in which canvas is pasted to a wall as a base for mural painting, traditionally using an adhesive made of white lead ground in oil., it shows more than a dozen bargeman inside the exchange office crowded around a chart that lists the merchandise available for transport, along with their respective tonnage, docking dates, and destinations.

In recent times, the lock of Saint-Mammès and its facing property have made headlines. The erstwhile bourse is today owned by the Voies navigables de France (Waterways of France, or VNF), the government agency charged with managing France’s inlands waterways network and its associated facilities. Since 2020, the VNF has sought to sell the unused building. Many community stakeholders are keen to purchase the building for the municipality of Saint-Mammès, to petition the Ministry of Culture to classify it as a historical monument, and to turn it into a shipping museum, library, or other cultural space.24Geoffrey Faucheux, “Seine-et-Marne: La bourse d’affrètement de Saint-Mammès bientôt classée aux monuments historiques?,” actu.fr, December 8, 2020, https://actu.fr/ile-de-france/saint-mammes_77419/seine-et-marne-la-bourse-d-affretement-de-saint-mammes-bientot-classee-aux-monuments-historiques_37974135.html Joël Surier, mayor of Saint-Mammès, compiled a dossier to this effect with the help of two local groups, the Association Fluviale entre Seine et Loing (Seine and Loing River Association) and the Collectif 1000 Sabords (1000 Portholes Collective).25Biard to Boyle, April 1, 2022. However, efforts stalled in September 2021, much to the dismay of those partner organizations. As recently as April 3, 2022, residents of Saint-Mammès staged a protest outside the padlocked bourse, demanding that the mayor establish a commission to see the project through.26See “Quel avenir pour la bourse,” Saint-Mammès en transition: Collectif 1000 Sabords, April 19, 2022, https://collectif1000sabords.wordpress.com/2022/04/19/quel-avenir-pour-la-bourse It is this author’s hope that their plans are realized. The building and its environs are important not only for the history of Saint-Mammès, but also as a memorial to the town’s most celebrated painter, who recorded its canal lock again and again and made a lasting imprint on this quiet village.

Notes

-

Though the artist was born in Paris, his parents, William (1799–1879) and Felicia (née Sell, 1808–66) Sisley, hailed from the United Kingdom. This ancestry earned him the moniker made famous by Vivienne Couldrey’s monograph, Alfred Sisley: The English Impressionist (Newton Abbot, UK: David and Charles, 1992).

-

See, for example, Sylvie Brame and François Lorenceau, Alfred Sisley: Catalogue critique des peintures et des pastels (Lausanne: La Bibliothèque des arts, 2021), cats. 68, 151, 153, 492, 493, 657, 658, 800, 917, and P46, pp. 62, 89–90, 201, 252, 300, 341, and 395.

-

On Sisley’s debt to Constable, see MaryAnne Stevens, “Un peintre entre deux traditions,” in Alfred Sisley: Poète de l’impressionnisme, exh. cat. (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 2002), 53. As Stevens notes, one painting that Sisley had opportunity to see was Constable’s A Boat Passing a Lock, 1826, oil on canvas, 40 x 50 in. (101.6 x 127 cm), Royal Academy of Arts, London, 03/923.

-

For Geffroy’s description of “le paisible Saint-Mammès dont Sisley est le poète charmant” (the peaceful Saint-Mammès of which Sisley is the charming poet), see Gustave Geffroy, “Chronique: A. Sisley,” La Justice, June 23, 1883, 1. For the poem, see Henri de Régnier, “Médaillons de peintres,” Revue des Deux Mondes 48, no. 3 (December 1, 1918): 619.

-

Hélène Fatoux, Histoire d’Eau en Seine-et-Marne (Le Mée-sur-Seine, France: Editions Amattéis, 1987), 1:49.

-

See Mairie de Saint-Mammès, “La Bourse d’Affrètement de Saint-Mammès: L’entretien et la modernisation des ouvrages,” accessed May 9, 2022, https://mairiesaintmammes.fr/bourse-ouvrages. I thank Bérengère Biard, Association Fluviale entre Seine et Loing, for referring me to this site.

-

E. Lèbe-Gigun, “Canal du Loing,” Rapports du préfet: Conseil général du Loiret (August 1890): 70. Due to changes in the Seine’s water levels, the Saint-Mammès lock is no longer active.

-

For a list of principal merchandise by tonnage, see Lèbe-Gigun, “Canal du Loing,” 73.

-

The drowned man likely served as lockkeeper when Sisley painted the Nelson-Atkins work. Given the artist’s frequent visits to Saint-Mammès during the 1880s, it is possible that the two men were acquainted.

-

Germaine Decaris, “À la croisée des fleuves: L’écluse de Saint-Mammès,” Le Soir, September 8, 1929, 1, 3. Péan’s successor faced a steep learning curve. Barely five weeks after Péan resigned his post, a horse-drawn boat refused to cede the right of way to a steam-powered one at the Saint-Mammès lock, blocking traffic and necessitating police intervention. This incident was widely covered in the French press. See “Deux bateliers entêtés obstruent le canal du Loing à l’écluse de Saint-Mammès,” Le Petit parisien, November 8, 1929, 3; and Lucien Louage, “On ne passe pas!: La navigation est interrompue à l’écluse Saint-Mammès,” L’Informateur de Fontainebleau, November 8, 1929, 1.

-

Sisley’s best-known livre de raison belongs to the Musée du Louvre (RF 11596) and contains sixty sketches of completed paintings; see Georges Wildenstein, “Un carnet de dessins de Sisley au musée du Louvre,” Gazette des beaux-arts 53, no. 1080 (January 1959): 57–60. The current drawing comes from a slightly larger livre de raison. See H[endrik] R[ichard] Hoetink, Franse tekeningen uit de 19e eeuw: Catalogus van de verzameling in het Museum Boymans-van Beuningen (Rotterdam: Museum Boymans-van Beuningen, 1968), 144.

-

Bérengère Biard, Association Fluviale entre Seine et Loing, to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, April 7, 2022, NAMA curatorial files.

-

For a discussion of this legislation and its ramifications, see Anne L. Cowe, “Sisley and the Seine: A River of Change,” in Marina Ferretti Bocquillon, Impressionism on the Seine, exh. cat. (Giverny: Musée des impressionnismes, 2010), 29–41.

-

See Brame and Lorenceau, Alfred Sisley: Catalogue critique des peintures et des pastels, cats. 115 and 427, pp. 76 and 180. Both paintings are in private collections. The former was sold at Impressionist and Modern Art, Bonham’s, London, February 4, 2016, lot 10; the latter at Impressionist and Modern Art: Part Two, Sotheby’s, New York, November 3, 2005, lot 117.

-

“Make A Stop at the Village of the Bargemen,” Office de Tourisme Moret Seine et Loing, accessed May 9, 2022, https://www.msl-tourisme.fr/en/discover-moret-seine-loing/history-heritage/msl-distillation-french-history/the-village-of-the-bargemen.html.

-

It is unclear precisely when construction began on the lockkeeper’s house, but it was likely after 1755, since the building is absent from a 1755 map of the property. Biard to Boyle, April 6, 2022, NAMA curatorial files. See also Mairie de Saint-Mammès, “La Bourse d’Affrètement de Saint-Mammès: Origines et histoires,” accessed May 9, 2022, https://mairiesaintmammes.fr/bourse-origines/.

-

Biard to Boyle, April 6 and 7, 2022.

-

For contrasting examples, see Brame and Lorenceau, Alfred Sisley: Catalogue critique des peintures et des pastels, cats. 666 and 800, pp. 255 and 300.

-

See Mairie de Saint-Mammès, “La Bourse d’Affrètement.”

-

Dominique Malécot, “La libéralisation du transport fluvial entre dans les faits le 1er janvier,” Les Échos, December 24, 1999, https://www.lesechos.fr/1999/12/la-liberalisation-du-transport-fluvial-entre-dans-les-faits-le-1er-janvier-783331. France was the last member of the European Union to implement this change. Since 2000, French bargemen have offered their services directly to shippers.

-

For more on CitéCréation, see their website at https://citecreation.fr.

-

Ministère de la Culture, “Site d’écluse dit écluse 20 de Saint-Mammès,” POP: La plateforme ouverte du patrimoine, accessed May 9, 2022, https://www.pop.culture.gouv.fr/notice/merimee/IA77000036.

-

See Mairie de Saint-Mammès, “La Bourse d’Affrètement.”

-

Geoffrey Faucheux, “Seine-et-Marne: La bourse d’affrètement de Saint-Mammès bientôt classée aux monuments historiques?,” actu.fr, December 8, 2020, https://actu.fr/ile-de-france/saint-mammes_77419/seine-et-marne-la-bourse-d-affretement-de-saint-mammes-bientot-classee-aux-monuments-historiques_37974135.html.

-

Biard to Boyle, April 1, 2022.

-

See “Quel avenir pour la bourse,” Saint-Mammès en transition: Collectif 1000 Sabords, April 19, 2022, https://collectif1000sabords.wordpress.com/2022/ 04/19/quel-avenir-pour-la-bourse.

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Becca Goodman, “Alfred Sisley, The Lock of Saint-Mammès, 1885,” technical entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.662.2088.

MLA:

Goodman, Becca. “Alfred Sisley, The Lock of Saint-Mammès, 1885,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.662.2088.

Alfred Sisley produced dozens of works in Saint-Mammès, France, but the painting at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art is particularly striking due to the unique depiction of a tall, tower-like piece of equipment on the leftmost boat. This structure, which appears to be a floating pile driver, is noteworthy because Sisley depicted it in only three other known paintings (see two of them in Figs. 3–4).1Sylvie Brame and François Lorenceau, Alfred Sisley: Catalogue Critique des Peintures et des Pastels (Lausanne: La Bibliothèque des Arts, 2021). See Barges, 1885 (no. 657, p. 252); Cargo Ship on the Loing, ca. 1880 (no. 427, p. 180); and Le bac à l’entrée de Bougival, ca. 1874 (no. 115, p. 76). Regarding nineteenth-century pile drivers, see Alan J. Lutenegger, “Historical Application of Screw-Piles and Screw-Cylinder Foundations for 19th-Century Ocean Piers,” International Conference on Case Histories in Geotechnical Engineering (Rolla, MO: Missouri University of Science and Technology, 2013), https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/icchge/7icchge/session02/20. Such uncommon sightings were likely captivating for an artist with a keen interest in mechanical subjects; they also must have been fleeting, as it seems Sisley did not expect the arrival of the equipment when he planned the composition. While there is minimal underdrawingunderdrawing: A drawn or painted sketch beneath the paint layer. The underdrawing can be made from dry materials, such as graphite or charcoal, or wet materials, such as ink or paint. anchoring the major elements of the imagery, there is no preliminary sketching associated with the pile driver. Moreover, the machinery was painted wet-over-drywet-over-dry: An oil painting technique that involves layering paint over an already dried layer, resulting in no intermixing of paint or disruption to the lower paint strokes., suggesting it was an addition painted after the composition was nearly finished.

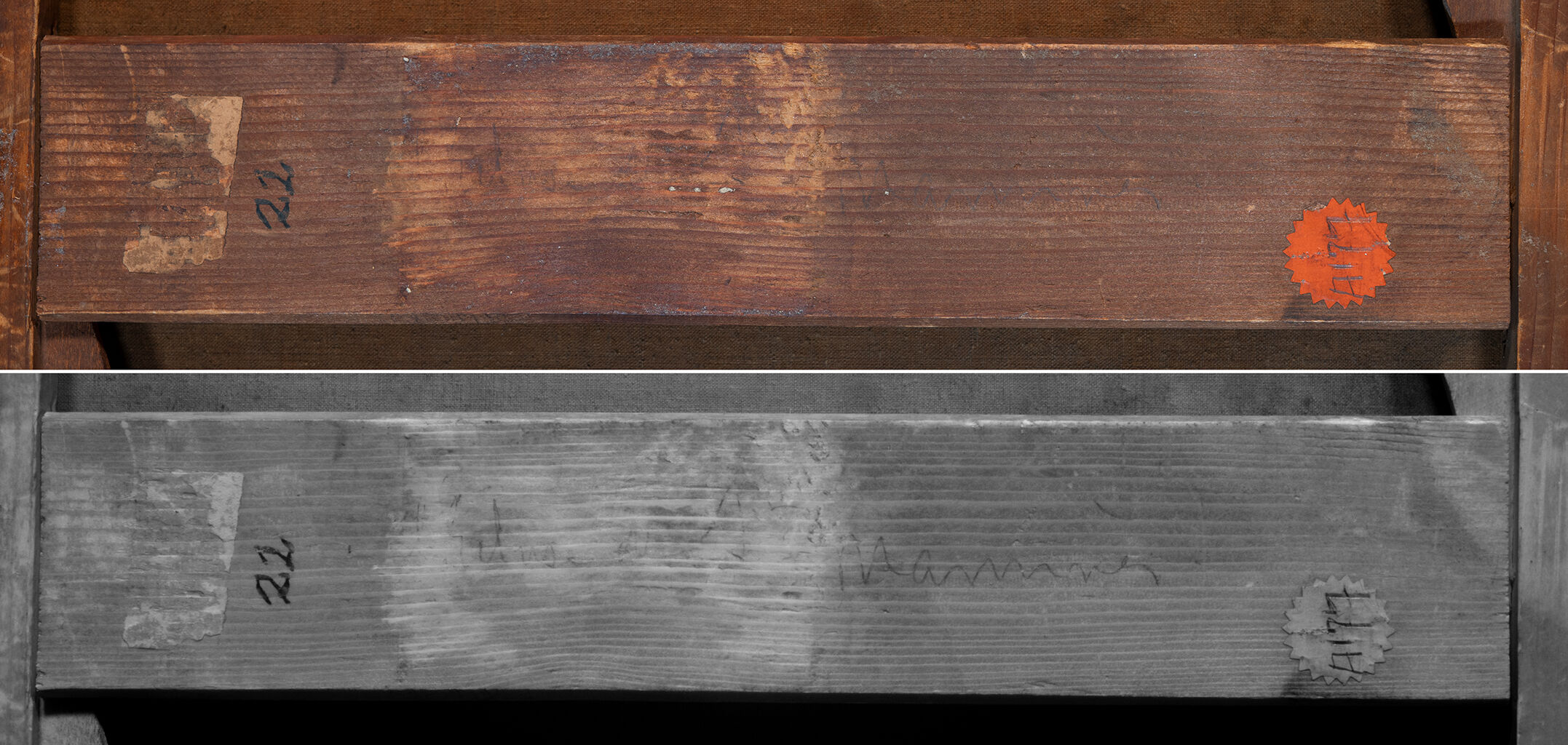

Sisley executed the painting on canvas tensioned to a five-membered stretcherstretcher: A wooden structure to which the painting’s canvas is attached. Unlike strainers, stretchers can be expanded slightly at the joints to improve canvas tension and avoid sagging due to humidity changes or aging. that measures approximately 55 x 38 cm, a standard sizestandard-format supports: Commercially prepared supports available through art suppliers, which gained popularity in the nineteenth century during the industrialization of art materials. Available in three formats figure (portrait), paysage (landscape), and marine (marine), these were numbered 1 through 120 to indicate their size. For each numbered size, marine and paysage had two options available: a larger format (haute) and smaller (basse) format. no. 10 paysage. The stretcher is original, and a graphite inscription reading “L’Écluse de St. Mammès” is present along the length of the vertical crossbar (Fig. 6).2The inscription may have been overlooked in the past, as there are remnants of a now-missing label on the crossbar. This label would have obscured the graphite inscription. It appears to be written in Sisley’s own hand. The text corresponds to the original French title of the work recorded in Durand-Ruel’s stock books in 1885.3The initial title of L’Écluse de St. Mammès with the abbreviated spelling of “St. Mammès” is found in Durand-Ruel’s 1885 stock book and likely came from Sisley’s spelling on the back of the stretcher. By 1899, Durand-Ruel recorded the painting’s title in their stock book as L’Écluse de Saint-Mammès, with “Saint-Mammès” fully spelled out and hyphenated. This spelling was retained in François Daulte’s 1959 catalogue raisonné. See Brigid M. Boyle, “Alfred Sisley, The Lock of Saint-Mammès, 1885, Working Document,” April 26, 2022, NAMA curatorial files. As on the verso of Sisley’s The Embankment at Billancourt—Snow, ca. 1879, “10w.” surrounded by an oval is stamped in black ink at the lower center of the vertical crossbar. The oval line overlaps the red Durand-Ruel label, meaning the work was stamped after Durand-Ruel registered and photographed it.4The red label bears the inscription “A177,” which is the number associated with Durand-Ruel’s photo-documentation of the work. The number can be found on the back of a historical photograph of the painting: Durand-Ruel photo stock card, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Photo Archives, no. A177. See Boyle, “Working Document,” April 26, 2022, NAMA curatorial files. This suggests the stamp is related to Durand-Ruel’s framing system, as discussed in The Embankment’s technical entry.

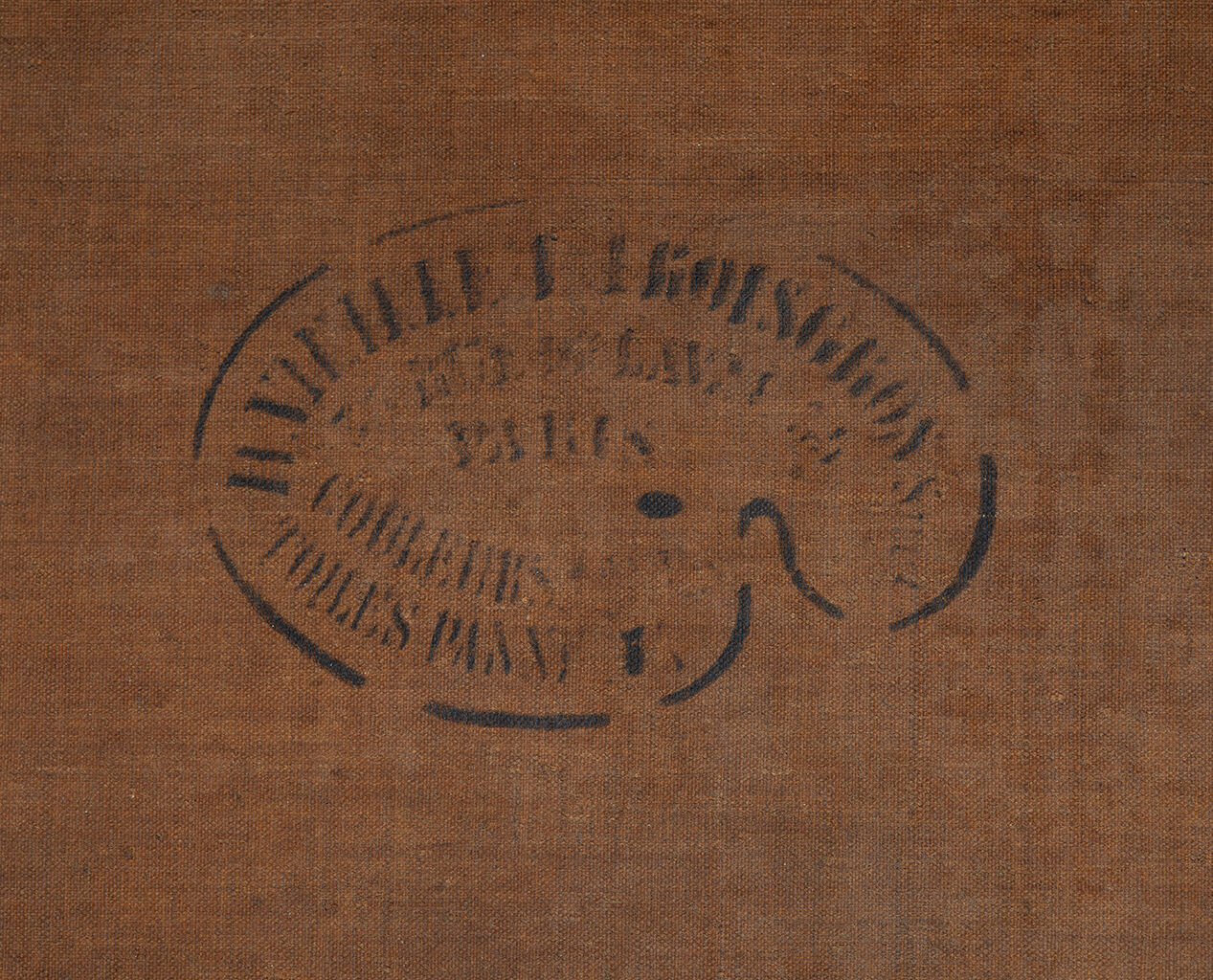

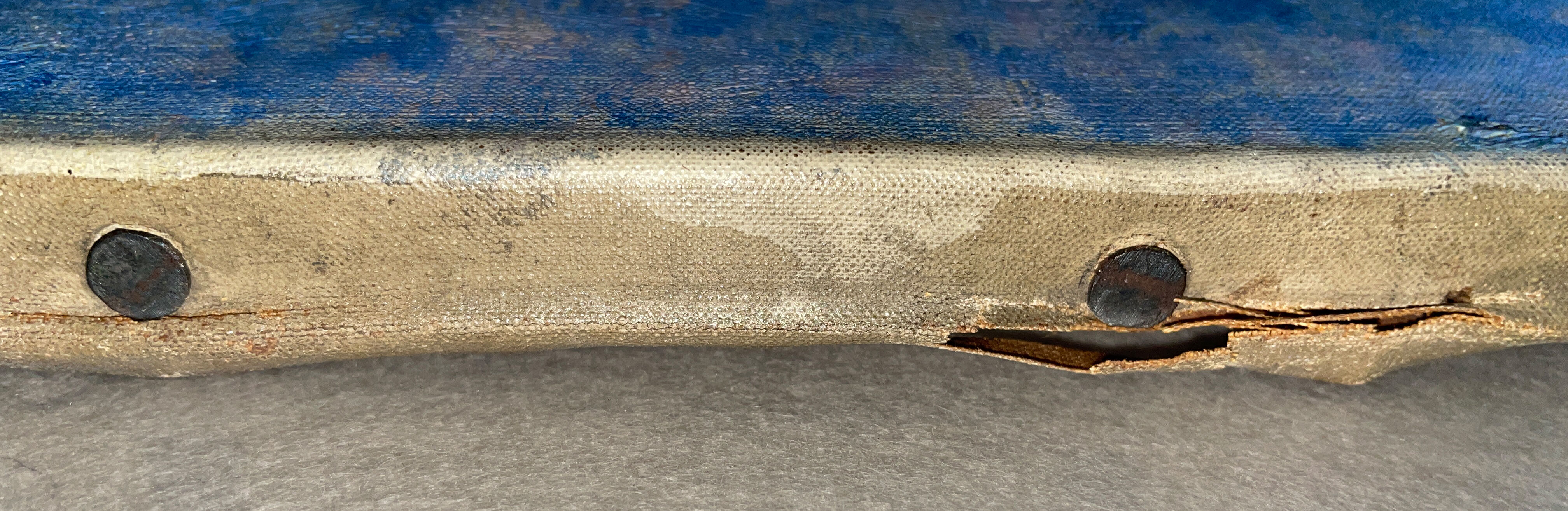

The canvas is unlinedlining: A procedure used to reinforce a weakened canvas that involves adhering a second fabric support using adhesive, most often a glue-paste mixture, wax, or synthetic adhesive. and bears an intact canvas stampcanvas stamp: An ink stamp, often present on the reverse of the canvas, signifying the company that sold or prepared the canvas. As these companies sometimes performed framing and restorations, these stamps could also reflect these services. See also supplier mark. on the proper right side of the work. The text is stenciled within the shape of a palette and reads, “H. VIEILLE, E. TROISGROS Sucr/ 35 RUE DE LAVAL 35/ PARIS/ COULEURS [FINES]/ TOILES PANNE[AUX]” (Fig. 7). This particular stamp was in use between 1878 and 1883, but it has been noted on at least three other Sisley paintings from 1885 to 1889.5An Orchard (1885; Leventis Gallery, Nicosia, Cyprus), The Port of Saint-Mammès, Morning (1885; private collection), and Le Loing, Gelée Blanche (1889; Leicester Museums and Galleries). For the first two paintings, see “GL-Vieille-(H.)-et-Troisgros-(e.)-M-2,” Guide Labreuche: Guide historique des fournisseurs de matériel pour artistes à Paris, 1790–1960, https://www.guide-labreuche.com/file-index/gl-1680. For the third painting, see Emma Jansson and Christina Young, “Alfred Sisley’s Quiet Evolution,” Kermes 30, no. 106 (April–June 2017): 41–49. This suggests that Sisley amassed extra canvases for use throughout the 1880s or the merchant continued selling old stock after the stamp was retired.6These possible scenarios are discussed in more detail in the context of Claude Monet’s paintings, specifically Poppy Field (Giverny) (1890; Art Institute of Chicago), which bears the same palette-shaped stamp. See Kimberly Muir, Inge Fiedler, Don H. Johnson, and Robert Erdmann, “Thread Count, Weave, and Ground Analysis of Claude Monet’s Vieille & Troisgros/Troisgros Frères Canvases in the Art Institute of Chicago” in Arie Wallert, ed., Fifth International Symposium: Painting Techniques: History, Materials and Studio Practice (Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, 2016), 226–36.

Most of the original tacks are still in place along the tacking marginstacking margins: The outer edges of canvas that wrap around and are attached to the stretcher or strainer with tacks or staples. See also tacking edge.. There are only a few replacement tacks (6 of 36 total). There is a second set of four empty holes along the top and bottom edges. Since there are no extra holes on the left and right, these cannot be associated with a full set of tacks. Furthermore, there is no scallopingcusping: A scalloped pattern along the canvas edges that relates to how the canvas was stretched. Primary cusping reveals where tacks secured the canvas to the support while the ground layer was applied. Secondary cusping can form when a pre-primed canvas is re-stretched by the artist prior to painting. associated with these missing tacks and no other proof that the work has ever been restretched. In an examination of Sisley’s Hampton Court Bridge (1874; Wallraf-Richartz-Museum and Fondation Corboud, Cologne), conservators noted “careful stretching with intermediate fastening,” suggesting the empty holes were associated with the initial preparation of the support.7Hans Portsteffen and Katja Lewerentz, “Alfred Sisley, Hampton Court Bridge: Brief Report on Technology and Condition,” Research Project Painting Techniques of Impressionism and Postimpressionism, (Cologne: Wallraf-Richartz-Museum and Fondation Corboud, 2008), http://forschungsprojekt-impressionismus.de/bilder/pdf/52.pdf. While the tacking margins are now brittle and torn in a few places, the canvas remains taut and planar overall.

The canvas was likely commercially primedpriming layer: An opaque preparatory layer applied to the support, either commercially or by the artist, to prevent absorption of the paint into the canvas or panel. See also ground layer. with a thin, bright white ground layer that extends over the entirety of the tacking margins. Upon initial examination of the tacking margins, it appeared that there was a double ground: a warm beige layer with a cool white layer on top.8This layering structure and coloring was observed on Hampton Court Bridge. See Portsteffen and Lewerentz, “Alfred Sisley, Hampton Court Bridge: Brief Report on Technology and Condition.” However, it is more likely that there is only one ground layer, which has become partially discolored with grime and (unoriginal) varnish. What looked like a secondary white ground spilling over onto the tacking margins is probably the result of a previous cleaning, especially because the ground that has been protected by the tack heads still appears bright white (Fig. 8).

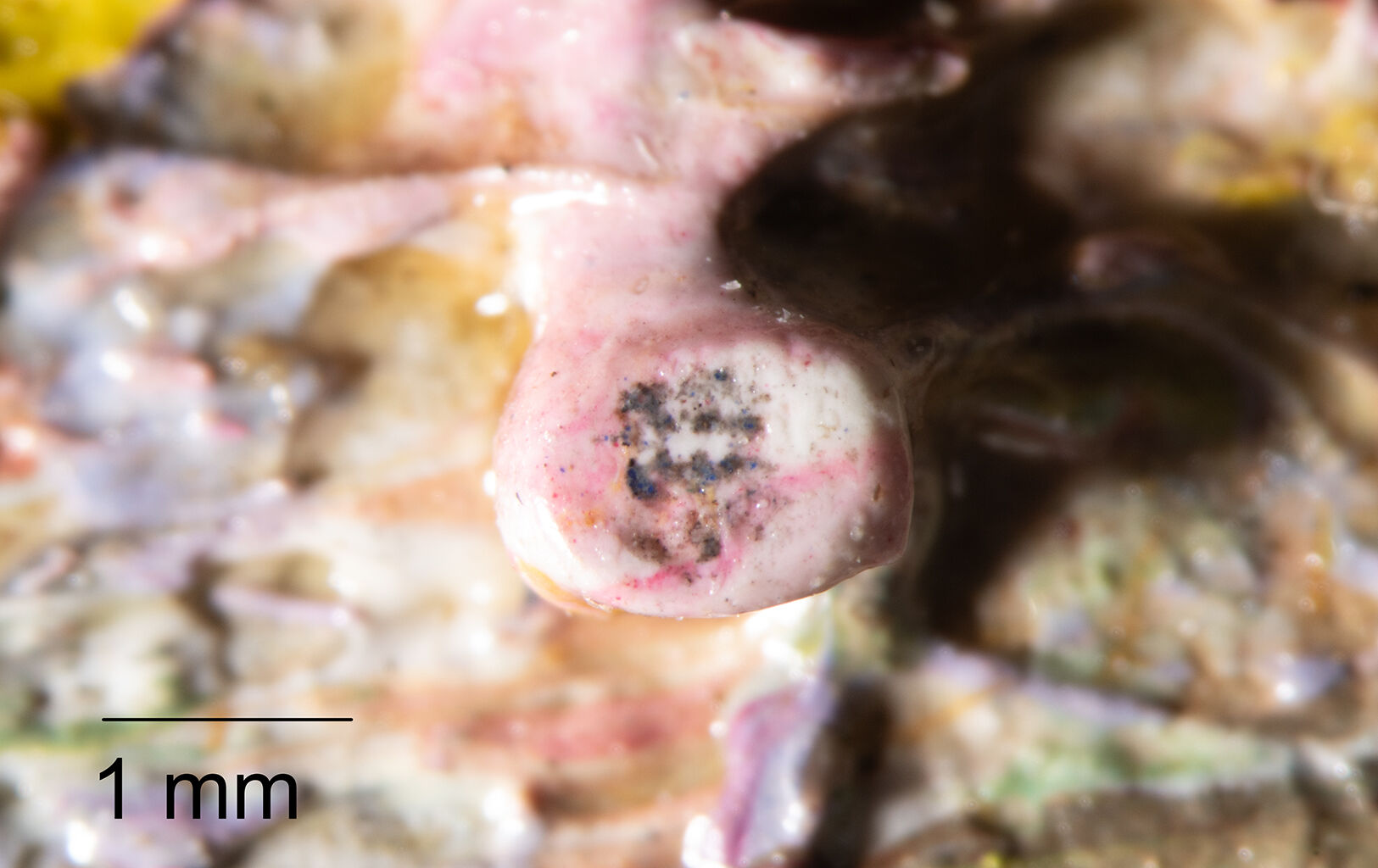

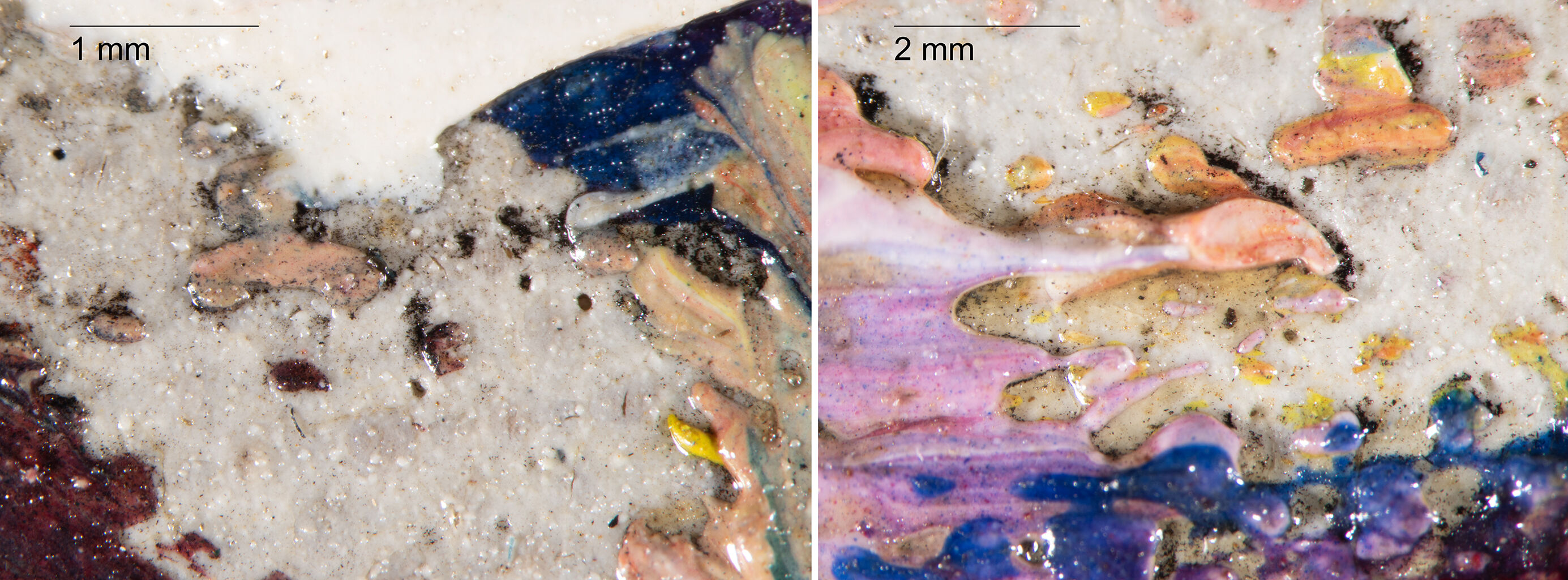

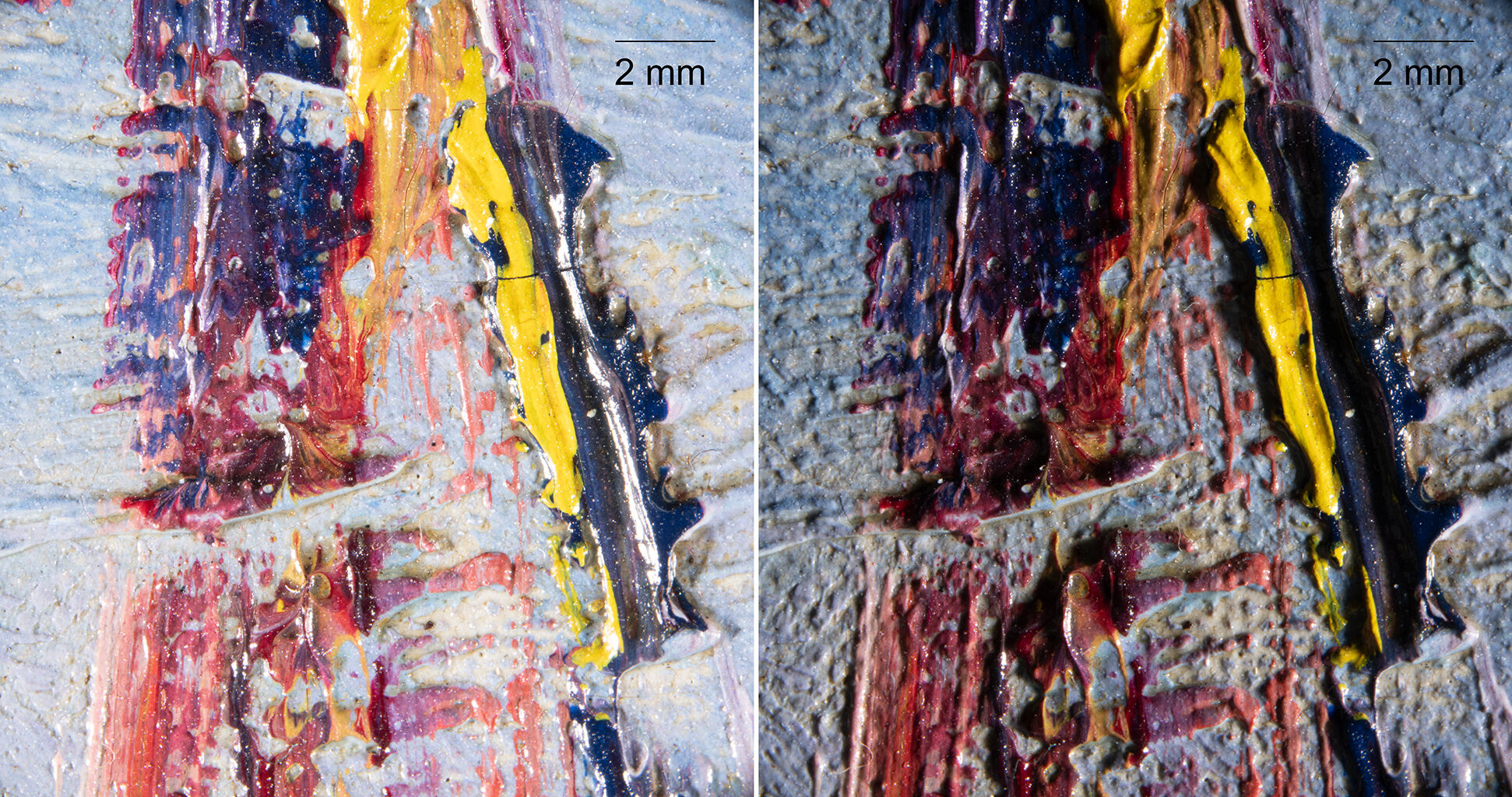

Like the other Sisley paintings in the museum’s collection, underdrawing was observed directly on the primed surface. The black granular medium is characteristic of charcoal, which could be smudged and brushed away. Since remnants are sparse and mixed into the subsequent paint layers, they are not detectable with infrared imaging techniquesinfrared (IR) photography: A form of infrared imaging that employs the part of the spectrum just beyond the red color to which the human eye is sensitive. This wavelength region, typically between 700-1,000 nanometers, is accessible to commonly available digital cameras if they are modified by removal of an IR blocking filter that is required to render images as the eye sees them. The camera is made selective for the infrared by then blocking the visible light. The resulting image is called a reflected infrared digital photograph. Its value as a painting examination tool derives from the tendency for paint to be more transparent at these longer wavelengths, thereby non-invasively revealing pentimenti, inscriptions, underdrawing lines, and early stages in the execution of a work. The technique has been used extensively for more than a half-century and was formerly accomplished with infrared film.. Still, the splintered black particles are visible under high magnification, notably in the major compositional elements such as the horizon line (specifically above the yellow stripe) and the contours of the boats (Fig. 9). It appears that there is no underdrawing associated with the pile driver, suggesting that Sisley did not plan to include it or that the equipment was not yet present when he first observed the scene.

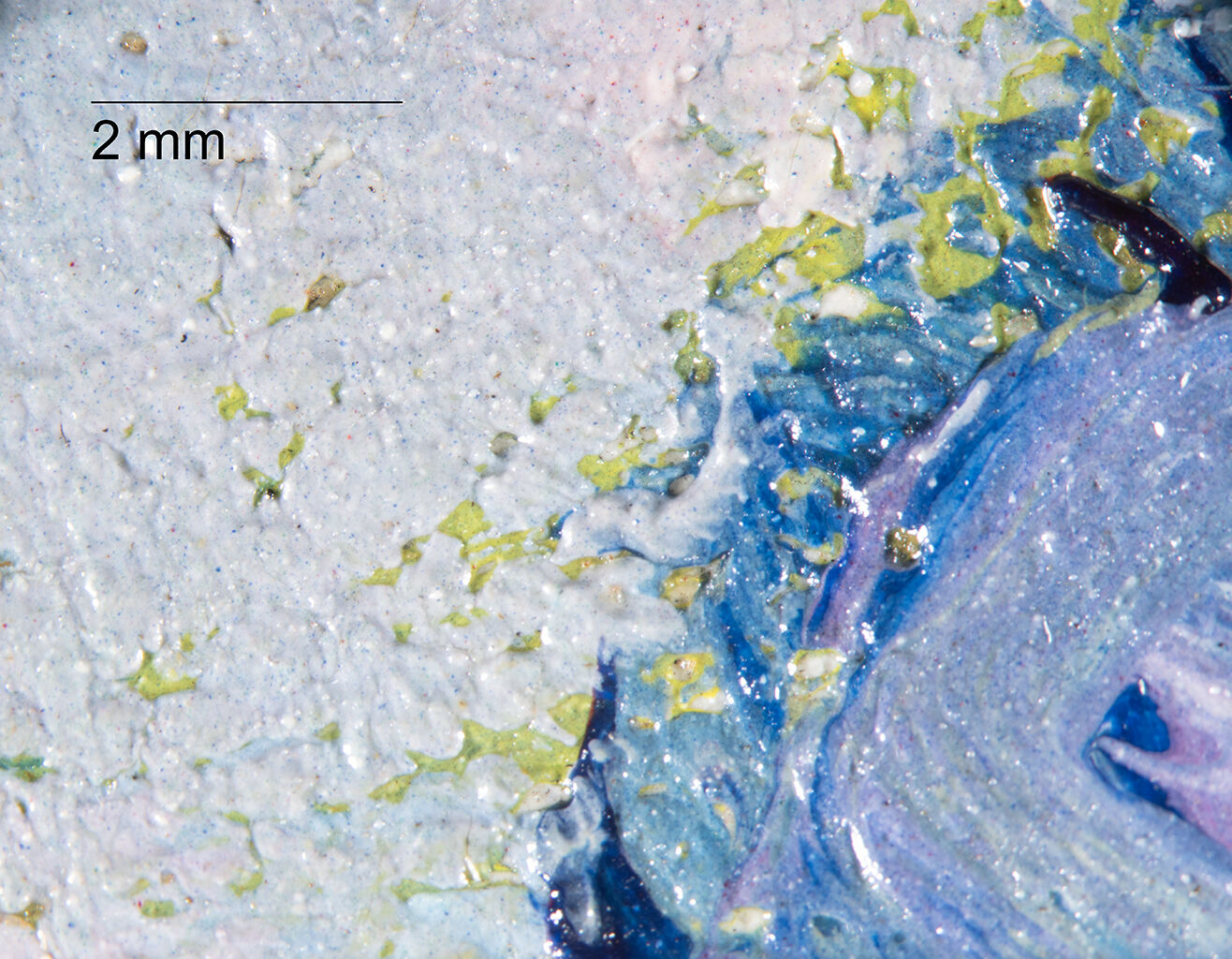

Sisley built up the imagery with a variety of energetic brushstrokes typical of his works from the 1870s to 1880s. The sky was laid in first with repetitive, long brushstrokes peppered with short daubs of crimson, deep blue, and bright green. The foliage and buildings were left in reservereserve: An area of the composition left unpainted with the intention of inserting a feature at a later stage in the painting process., and there is very little sky blue beneath them. For example, there is white ground showing through the central clump of foliage, but the tips of the treetops overlap the sky. The artist likely added final touches of blue to refine the trees, sandwiching tiny areas of green between layers of sky (Fig. 10). Almost all the compositional elements were planned and laid in directly on top of the white ground, which is visible through the broken brushstrokes. The ground was also intentionally exposed to serve as highlights. Despite there being thin passages and visible ground in much of the painting, Sisley used heavy applications of paint in the buildings and parts of the water to achieve high impastoimpasto: A thick application of paint, often creating texture such as peaks and ridges..

Sisley returned to the painting in a subsequent session. Wet-over-dry technique is apparent in the roof of the house, some parts of the sky, and even in the signature and date. The initial blue strokes forming the inscription at the bottom right corner seem to have been applied wet-into-wetwet-into-wet: An oil painting technique which involves blending of colors on the picture surface., but the glazy crimson was added wet-over-dry. Although the far-right boat and its surroundings were laid in directly on top of the ground, the cab was modified or fully added after the underlying layers had dried. Likewise, most of the figures were painted on top of dry layers of paint.

The largest compositional change is the addition of the pile driver. Painted completely wet-over-dry, the paint comprising the vertical tower catches the peaks and fills the valleys of the horizontal brushwork below (Figs. 11–12). Naturally, the pile driver’s spidery reflection in the water was also added on top of dry paint, but Sisley camouflaged it with more blue and green brushstrokes to help sink it into the water rather than let it remain solely on top.

Fig. 11. Photomicrographs of the tip of the pile driver in visible (left) and raking light (right), The Lock of Saint-Mammès (1885)

Fig. 11. Photomicrographs of the tip of the pile driver in visible (left) and raking light (right), The Lock of Saint-Mammès (1885)

Fig. 12. Photomicrograph of the leg of the pile driver, The Lock of Saint-Mammès (1885)

Fig. 12. Photomicrograph of the leg of the pile driver, The Lock of Saint-Mammès (1885)

In two instances, the highest peaks of impasto are flattened and imparted with a texture (Fig. 13). This may suggest the finished painting was leaned against another one while still slightly wet.

The painting remains in excellent condition today. Minor cracks are present in occasional thick applications of paint, such as in the central building. There are virtually no losses to the paint surface, and there is minimal, restrained retouchingretouching: Paint application by a conservator or restorer to cover losses and unify the original composition. Retouching is an aspect of conservation treatment that is aesthetic in nature and that differs from more limited procedures undertaken solely to stabilize original material. Sometimes referred to as inpainting or retouch. in the upper left corner. Although the painting was cleaned and varnished in 1994, yellowed remnants of an earlier natural resin coating remain in the interstices of the paint and on the tacking margins.

Notes

-

Sylvie Brame and François Lorenceau, Alfred Sisley: Catalogue Critique des Peintures et des Pastels (Lausanne: La Bibliothèque des Arts, 2021). See Barges, 1885 (no. 657, p. 252); Cargo Ship on the Loing, ca. 1880 (no. 427, p. 180); and Le bac à l’entrée de Bougival, ca. 1874 (no. 115, p. 76). Regarding nineteenth-century pile drivers, see Alan J. Lutenegger, “Historical Application of Screw-Piles and Screw-Cylinder Foundations for 19th-Century Ocean Piers,” International Conference on Case Histories in Geotechnical Engineering (Rolla, MO: Missouri University of Science and Technology, 2013), https://scholarsmine.mst.edu

/icchge ./7icchge /session02 /20 -

The inscription may have been overlooked in the past, as there are remnants of a now-missing label on the crossbar. This label would have obscured the graphite inscription.

-

The initial title of L’Écluse de St. Mammès with the abbreviated spelling of “St. Mammès” is found in Durand-Ruel’s 1885 stock book and likely came from Sisley’s spelling on the back of the stretcher. By 1899, Durand-Ruel recorded the painting’s title in their stock book as L’Écluse de Saint-Mammès, with “Saint-Mammès” fully spelled out and hyphenated. This spelling was retained in François Daulte’s 1959 catalogue raisonné. See Brigid M. Boyle, “Alfred Sisley, The Lock of Saint-Mammès, 1885, Working Document,” April 26, 2022, NAMA curatorial files.

-

The red label bears the inscription “A177,” which is the number associated with Durand-Ruel’s photo-documentation of the work. The number can be found on the back of a historical photograph of the painting: Durand-Ruel photo stock card, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Photo Archives, no. A177. See Boyle, “Working Document,” April 26, 2022, NAMA curatorial files.

-

An Orchard (1885; Leventis Gallery, Nicosia, Cyprus), The Port of Saint-Mammès, Morning (1885; private collection), and Le Loing, Gelée Blanche (1889; Leicester Museums and Galleries). For the first two paintings, see “GL-Vieille-(H.)-et-Troisgros-(e.)-M-2,” Guide Labreuche: Guide historique des fournisseurs de matériel pour artistes à Paris, 1790–1960, https://www.guide-labreuche.com

/file-index . For the third painting, see Emma Jansson and Christina Young, “Alfred Sisley’s Quiet Evolution,” Kermes 30, no. 106 (April–June 2017): 41–49./gl-1680 -

These possible scenarios are discussed in more detail in the context of Claude Monet’s paintings, specifically Poppy Field (Giverny) (1890; Art Institute of Chicago), which bears the same palette-shaped stamp. See Kimberly Muir, Inge Fiedler, Don H. Johnson, and Robert Erdmann, “Thread Count, Weave, and Ground Analysis of Claude Monet’s Vieille & Troisgros/Troisgros Frères Canvases in the Art Institute of Chicago” in Arie Wallert, ed., Fifth International Symposium: Painting Techniques: History, Materials and Studio Practice (Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, 2016), 226–36.

-

Hans Portsteffen and Katja Lewerentz, “Alfred Sisley, Hampton Court Bridge: Brief Report on Technology and Condition,” Research Project Painting Techniques of Impressionism and Postimpressionism (Cologne: Wallraf-Richartz-Museum and Fondation Corboud, 2008), http://forschungsprojekt-impressionismus.de

/bilder ./pdf /52.pdf -

This layering structure and coloring was observed on Hampton Court Bridge. See Portsteffen and Lewerentz, “Alfred Sisley, Hampton Court Bridge: Brief Report on Technology and Condition.”

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Alfred Sisley, The Lock of Saint-Mammès, 1885,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.662.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M.. “Alfred Sisley, The Lock of Saint-Mammès, 1885,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.662.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Alfred Sisley, The Lock of Saint-Mammès, 1885,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.662.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M.. “Alfred Sisley, The Lock of Saint-Mammès, 1885,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.662.4033.

Purchased from the artist by Galeries Durand-Ruel, Paris, stock no. 774, as L’Écluse de St. Mammès, December 22, 1885–August 1888 [1];

Transferred from Galeries Durand-Ruel, Paris, to Durand-Ruel Galleries, New York, August 1888 [2];

Erwin Davis (1831–1903), New York, by April 14, 1899;

Purchased from Davis by Durand-Ruel Galleries, New York, stock no. 2232, as L’Écluse de Saint-Mammès, 1899–February 1, 1943 [3];

Purchased from Durand-Ruel Galleries by Sam Salz Inc., New York, stock no. 596, as L’Écluse de St Mammé, February 1–March 22, 1943 [4];

Purchased from Salz by Mr. George S. Gregory (né Grisha Josefowitz, 1895–1983) and Mrs. Elizabeth “Lydia” Gregory (née Sliosberg, 1905–78), New York, 1943–March 5, 1983 [5];

By descent to their son, Alexis Gregory (1936–2020), New York, 1983–September 30, 1994;

Purchased from Gregory by Richard L. Feigen and Co., New York, stock no. 19627-D, as Le Loing à Saint-Mammès (The River Loing at Saint-Mammès), September 30–November 8, 1994 [6];

Purchased from Feigen by Marion (née Helzberg, 1931–2013) and Henry (1922–2019) Bloch, Shawnee Mission, KS, 1994–June 15, 2015;

Their gift to the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 2015.

Notes

[1] See emails from Flavie Durand-Ruel, Durand-Ruel et Cie., Paris, to Brigid M. Boyle, the Nelson-Atkins, April 6 and 19, 2022, NAMA curatorial files. A consular invoice on the painting’s stretcher indicates that The Lock of Saint-Mammès was shipped from Paris to New York on April 11, 1888. Durand-Ruel officially transferred ownership of the painting to its New York branch in August 1888.

[2] Durand-Ruel’s stock books do not record when or to whom stock no. 774 was sold. See email from Paul-Louis and Flavie Durand-Ruel, Durand-Ruel et Cie., Paris, to Nicole Myers, the Nelson-Atkins, January 11, 2016, NAMA curatorial files.

[3] For the purchase date, sale date, and stock number, see email from Paul-Louis Durand-Ruel and Flavie Durand-Ruel, Durand-Ruel et Cie., Paris, to Nicole Myers, the Nelson-Atkins, January 11, 2016, NAMA curatorial files. The stock number is corroborated by a Durand-Ruel paper label on the stretcher and a Durand-Ruel photo stock card, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Photo Archives, no. A177.

[4] Durand-Ruel recorded the purchase date as February 1, 1943, while Sam Salz recorded it as February 2, 1943; we have adopted the former. Salz recorded the sale date as March 22, 1943. See email from Paul-Louis Durand-Ruel and Flavie Durand-Ruel, Durand-Ruel et Cie., Paris, to Nicole Myers, the Nelson-Atkins, January 11, 2016, NAMA curatorial files; and Inventory Book, 1940–1944, pages 38 and 123, Sam Salz Archive, Department of Image Collections, National Gallery of Art Library, Washington, DC, Gift of Marc Salz in memory of his father Sam Salz.

[5] When George S. Gregory passed away on March 5, 1983, his son Alexis Gregory inherited The Lock of Saint-Mammès. Verbal communication from Peter Gregory, younger brother of Alexis Gregory, to Brigid M. Boyle, the Nelson-Atkins, March 21, 2022; see notes in NAMA curatorial files.

[6] For the purchase date of September 30, 1994, see email from Cynthia Conti, Richard L. Feigen and Co., to Brigid M. Boyle, the Nelson-Atkins, March 18, 2022, NAMA curatorial files. For the sale date of November 8, 1994, see Richard L. Feigen and Co. invoice, NAMA curatorial files. For the stock number, see paper label from Richard L. Feigen and Co. on the painting’s backing board.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Alfred Sisley, The Lock of Saint-Mammès, 1885,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.662.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M.. “Alfred Sisley, The Lock of Saint-Mammès, 1885,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.662.4033.

Alfred Sisley, Boats on the Canal du Loing, Saint-Mammès, ca. 1885, 21 9/16 x 15 3/16 in. (54.7 x 38.5 cm), private collection, cited in Sylvie Brame and François Lorenceau, Alfred Sisley: Catalogue critique des peintures et des pastels (Lausanne: La Bibliothèque des arts, 2021), no. 657, p. 252.

Alfred Sisley, The Saint-Mammès Lock (Department Seine-et-Marne, France), ca. 1885, black chalk, 5 1/16 x 8 1/4 in. (12.9 x 21 cm), Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, no. F II 144 (PK).

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Alfred Sisley, The Lock of Saint-Mammès, 1885,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.662.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M.. “Alfred Sisley, The Lock of Saint-Mammès, 1885,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.662.4033.

Loan Exhibition of Paintings from Collections of Associate Members, The New School for Social Research, New York, March 3–17, 1946, no. 41, as Ecluses a Saint Mammes [sic].

New York Collects, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, July 3–September 2, 1968, no. 202, as The Lock at Saint-Mammes [sic].

Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, June 9–September 9, 2007, no. 11, as The Lock of Saint-Mammès (L’écluse de Saint-Mammès).

References

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Alfred Sisley, The Lock of Saint-Mammès, 1885,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.662.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M.. “Alfred Sisley, The Lock of Saint-Mammès, 1885,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.662.4033.

Loan Exhibition of Paintings from Collections of Associate Members, exh. cat. (New York: New School for Social Research, 1946), unpaginated, as Ecluses a Saint-Mammes [sic].

Howard Devree, “New School Gives Exhibition of Art,” New York Times 95, no. 32,182 (March 5, 1946): 22.

François Daulte, Alfred Sisley: Catalogue raisonné de l’œuvre peint (Lausanne: Éditions Durand-Ruel, 1959), no. 605, pp. 345, 351, 353, 358, (repro.), as l’Ècluse de Saint-Mammès.

H[endrik] R[ichard] Hoetink, Franse tekeningen uit de 19e eeuw: Catalogus van de verzameling in het Museum Boymans-van Beuningen (Rotterdam: Museum Boymans-van Beuningen, 1968), 144.

New York Collects, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1968), 41, as The Lock at Saint-Mammes [sic].

Hilton Kramer, “In the Genteel Tradition,” New York Times 117, no. 40,349 (July 14, 1968): D25.

Christopher Lloyd, Retrospective Alfred Sisley, trans. Nobuyuki Senzoku, exh. cat. (Tokyo: Art Life, 1985), 153, 174.

Impressionist and Modern Paintings and Sculpture: Part I (London: Sotheby’s, November 28, 1989), 46.

MaryAnne Stevens, ed., Alfred Sisley, exh. cat. (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 1992), 38, 42, 50, 52n66, 53n105, 58, 72n16, as Saint-Mammès Lock.

Alfred Sisley: poète de l’impressionnisme, exh. cat. (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 2002), 89, 354, 357n16.

Rebecca Dimling Cochran and Bobbie Leigh, “100 Top Collectors who have made a difference,” Art and Antiques 28, no. 3 (March 2006): 90.

Bobbie Leigh, “Magnificent Obsession,” Art and Antiques 28, no. 6 (June 2006): 62, as The Locks of Saint-Mammès.

Alice Thorson, “Some Nelson shows add admission charge,” Kansas City Star 127, no. 196 (April 1, 2007): G7, (repro.), as The Lock of Saint-Mammès.

Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 14, 70–73, 158, (repro.), as The Lock of Saint-Mammès (L’écluse de Saint-Mammès).

Alice Thorson, “A Tiny Renoir Began Impressive Obsession,” Kansas City Star 127, no. 269 (June 3, 2007): E4, as The Lock of Saint-Mammès.

“Lasting Impressions: A Tribute to Marion and Henry Bloch,” Member Magazine (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (Fall 2007): 11–12.

Steve Paul, “Pretty Pictures: Marion and Henry Bloch’s collection of superb Impressionist masters,” Panache 4, no. 3 (Fall 2007): 20.

“A 75th Anniversary Celebrated with Gifts of 400 Works of Art,” Art Tattler International (February 2010): http://arttattl.ipower.com/archivemagnificentgifts.html.

Alice Thorson, “Blochs add to Nelson treasures,” Kansas City Star 130, no. 141 (February 5, 2010): A1, A8.

Carol Vogel, “O! Say, You Can Bid on a Johns,” New York Times 159, no. 54,942 (February 5, 2010): C26.

Alice Thorson, “Gift will leave lasting impression,” Kansas City Star 130, no. 143 (February 7, 2010): G1–G2.

Thomas M. Bloch, Many Happy Returns: The Story of Henry Bloch, America’s Tax Man (Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons, 2011), 174–75.

Diane Stafford, “Bloch gift to go for Nelson upgrade,” Kansas City Star 135, no. 203 (April 8, 2015): A1, A8.

“Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art officially accessions Bloch Impressionist masterpieces,” Artdaily.org (July 25, 2015): http://artdaily.com/news/80246/Nelson-Atkins-Museum-of-Art-officially-accessions-Bloch-Impressionist-masterpieces.

Julie Paulais, “Le Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art reçoit des tableaux impressionnistes en échange de leurs répliques,” Le Journal des arts (July 30, 2015): https://www.lejournaldesarts.fr/patrimoine/le-nelson-atkins-museum-art-recoit-des-tableaux-impressionnistes-en-echange-de-leurs.

Josh Niland, “The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Acquires a Renowned Collection of Impressionist and Postimpressionist Art,” architecturaldigest.com (July 31, 2015): https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/nelson-atkins-museum-accessions-bloch-art-collection.

Nancy Staab, “Van Gogh is a Go!” 435: Kansas City’s Magazine (September 2015): 76.

“Nelson-Atkins to unveil renovated Bloch Galleries of European Art in winter 2017,” Artdaily.org (July 20, 2016): http://artdaily.com/news/88852/Nelson-Atkins-to-unveil-renovated-Bloch-Galleries-of-European-Art-in-winter-2017 ->.

Diane Stafford, “What you may not know about Henry Bloch,” Spirit (September 23, 2016): http://www.kansascity.com/living/spirit/article102669387.html [repr., Diane Stafford, “What’s less known about Henry Bloch,” Kansas City Star 137, no. 8 (September 25, 2016): 1E, 6E.]

“Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art celebrates generosity of Henry Bloch with new acquisition,” Artdaily.org (October 18, 2016): https://artdaily.cc/news/90923/Nelson-Atkins-Museum-of-Art-celebrates-generosity-of-Henry-Bloch-with-new-acquisition#.XnKATqhKiUk.

Catherine Futter et al., Bloch Galleries: Highlights from the Collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2016), 77, (repro.), as The Lock of Saint-Mammès.

Kelly Crow, “Museum Rewards Donor with Fake Art to Hang at Home,” Wall Street Journal (January 25, 2017): https://www.wsj.com/articles/museum-rewards-donor-with-fake-art-to-hang-at-home-1485370768.

David Frese, “Bloch savors paintings in redone galleries,” Kansas City Star (February 25, 2017): 1A, 14A.

Albert Hecht, “Henry Bloch’s Masterpieces Collection to Go On Display at Nelson-Atkins Museum,” Jewish Business News (February 26, 2017): http://jewishbusinessnews.com/2017/02/26/henry-bloch-masterpieces-collection/.

David Frese, “A collection of stories,” and “Inside the Bloch Galleries: An interactive experience,” Kansas City Star 137, no. 169 (March 5, 2017): 1D, 4D–6D, (repro.), as The Lock of Saint-Mammès.

“Editorial: Thank you, Henry and Marion Bloch,” Kansas City Star (March 7, 2017), http://www.kansascity.com/opinion/editorials/article137040948.html [repr., in “Thank you, Henry and Marion Bloch,” Kansas City Star 137, no. 172 (March 8, 2017): 16A].

Hampton Stevens, “(Not Actually) 12 Things To Do During The Big 12 Tournament,” Flatland: KCPT’s Digital Magazine (March 9, 2017): http://www.flatlandkc.org/arts-culture/sports/not-actually-12-big-12-tournament/.

Laura Spencer, “The Nelson-Atkins’ Bloch Galleries Feature Old Masterworks and New Technology,” KCUR (March 10, 2017): http://kcur.org/post/nelson-atkins-bloch-galleries-feature-old-masterworks-and-new-technology#stream/0, (repro.), as The Lock of Saint-Mammes [sic].

Victoria Stapley-Brown, “Nelson-Atkins Museum’s new European art galleries come with a ‘love story,’” Art Newspaper (March 10, 2017): http://theartnewspaper.com/news/museums/nelson-atkins-museum-s-new-european-art-galleries-come-with-a-love-story/.

Harry Bellet, “Don du ciel pour le Musée Nelson-Atkins,” Le Monde (March 13, 2017): http://www.lemonde.fr/arts/article/2017/03/13/don-du-ciel-pour-le-musee-nelson-atkins_5093543_1655012.html.

Menachem Wecker, “Jewish Philanthropist Establishes Kansas City as Cultural Mecca,” Forward (March 14, 2017): http://forward.com/culture/365264/jewish-philanthropist-establishes-kansas-city-as-cultural-mecca/ [repr., in Menachem Wecker, “Kansas City Collection Is A Chip Off the Old Bloch,” Forward (March 17, 2017): 20–22].

Juliet Helmke, “The Bloch Collection Takes up Residence in Kansas City’s Nelson Atkins Museum,” Blouin ArtInfo International (March 15, 2017): http://www.blouinartinfo.com/news/story/2005267/the-bloch-collection-takes-up-residence-in-kansas-citys.

Louise Nicholson, “How Kansas City got its magnificent museum,” Apollo: The International Art Magazine (April 7, 2017): https://www.apollo-magazine.com/how-kansas-city-got-its-magnificent-museum.

Lilly Wei, “Julián Zugazagoitia: ‘Museums should generate interest and open a door that leads to further learning,’” Studio International (August 21, 2017): http://studiointernational.com/index.php/julian-zugazagoitia-director-nelson-atkins-museum-of-art-kansas-city-interview.

Robert D. Hershey Jr., “Henry Bloch, H&R Block’s cofounder, dies at 96,” Boston Globe (April 23, 2019): https://www3.bostonglobe.com/metro/obituaries/ 2019/04/23/henry-bloch-block-cofounder/?arc404=true.

Robert D. Hershey Jr., “Henry W. Bloch, Tax-Preparation Pioneer (and Pitchman), Is Dead at 96,” New York Times (April 23, 2019): https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/23/obituaries/henry-w-bloch-dead.html.

Megan McDonough, “Henry Bloch, whose H&R Block became world’s largest tax-services provider, dies at 96,” Washington Post (April 23, 2019): https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/obituaries/henry-bloch-whose-handr-block-became-worlds-largest-tax-services-provider-dies-at-96/2019/04/23/19e95a90-65f8-11e9-a1b6-b29b90efa879_story.html.

Claire Selvin, “Henry Wollman Bloch, Collector and Prominent Benefactor of Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Is Dead at 96,” ArtNews (April 23, 2019): http://www.artnews.com/2019/04/23/henry-bloch-dead-96/.

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “Henry Bloch, co-founder of H&R Block, dies at 96,” Kansas City Star 139, no. 219 (April 24, 2019): 1A, 2A.

“Henry Wollman Bloch (1922–2019),” Artforum (April 24, 2019): https://www.artforum.com/news/henry-wollman-bloch-1922-2019-79547.

Frank Morris, “Henry Bloch, Co-Founder Of H&R Block, Dies At 96,” NPR (April 24, 2019): https://www.npr.org/2019/04/24/716641448/henry-bloch-co-founder-of-h-r-block-dies-at-96.

Ignacio Villarreal, “Nelson-Atkins mourns loss of Henry Bloch,” ArtDaily.org (April 24, 2019): http://artdaily.com/news/113035/Nelson-Atkins-mourns-loss-of-Henry-Bloch#.XMB76qR7laQ.

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “H&R Bloch co-founder, philanthropist Bloch dies,” Cass County Democrat Missourian 140, no. 29 (April 26, 2019): 1A, 3A, (repro.).

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “KC businessman and philanthropist Henry Bloch dies,” Lee’s Summit Journal 132, no. 79 (April 26, 2019): 1A.

Luke Nozicka, “Family and friends remember Henry Bloch of H&R Block,” Kansas City Star 139, no. 225 (April 30, 2019): 4A [repr., in Luke Nozicka, “Family and friends remember Henry Bloch of H&R Block,” Kansas City Star 139, no. 228 (May 3, 2019): 3A].

Eric Adler, “Sold for $3.25 million, Bloch’s home in Mission Hills may be torn down,” Kansas City Star 141, no. 90 (December 16, 2020): 2A, (repro.), as The Lock of Saint-Mammes [sic] (L’Ecluse de Saint-Mammes) [sic].

Kristie C. Wolferman, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A History (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2020), 344–45.

Sylvie Brame and François Lorenceau, Alfred Sisley: Catalogue critique des peintures et des pastels (Lausanne: La Bibliothèque des arts, 2021), no. 658, pp. 252, 477, 516–19, 522–23, 550, (repro.), as L’écluse de Saint-Mammès, canal du Loing.