![]()

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Pinning the Hat, 1890 or 1893

| Artist | Pierre-Auguste Renoir, French, 1841–1919 |

| Title | Pinning the Hat |

| Object Date | 1890 or 1893 |

| Alternate and Variant Titles | The Flowered Hat; Le chapeau épinglé; Jeunes filles arrangeant un chapeau |

| Medium | Pastel on cream laid paper on laminated cardboard |

| Dimensions (Unframed) | 25 5/8 x 20 1/8 in. (65.1 x 51.1 cm) |

| Signature | Signed lower right: Renoir. |

| Credit Line | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Gift of Henry W. and Marion H. Bloch, 2015.13.20 |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Pinning the Hat, 1890 or 1893,” catalogue entry in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.656.5407

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Pinning the Hat, 1890 or 1893,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.656.5407.

In April 1921, sixteenth months after Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s (1841–1919) death at the age of seventy-eight, his longtime dealer Paul Durand-Ruel held an exhibition of the artist’s works on paper.1Claude Monet introduced Renoir to Durand-Ruel in 1872. The dealer represented him for almost fifty years and organized his first solo exhibition of paintings in April 1883. See Barbara Ehrlich White, Renoir: An Intimate Biography (London: Thames and Hudson, 2017), 54, 122. Featuring 142 watercolors, pastels, and drawings, this retrospective was well reviewed in the French press. Like many Impressionists, Renoir had been poorly appreciated during the first half of his career, but he experienced a surge in popularity after 1890, first with American audiences and then in his home country.2White, Renoir, 158, 280, 321. A critic for the French daily Le Temps pronounced the Durand-Ruel show “magnificent” and applauded Renoir’s rendering of body language and emotion:

[T]hese drawings were almost all executed during the second half of his career, at a time when, having become a father late in life—a father passionately enamored of his children—Renoir never tired of observing the constant fluctuations in their looks [and] the variety of expressions, bearings, and gestures wrought by play, yearning, displeasure, satisfaction, sleep. There are sketches that would not be out of place at the Louvre, alongside those of Watteau.3T.-S., “Art et curiosité: Une exposition de dessins de Renoir,” Le Temps, April 6, 1921. “[C]es dessins ont été exécutés presque tout dans la seconde partie de sa carrière, à l’heure où, devenu père sur le tard, et un père passionnément épris de ses enfants, Renoir ne se lassait pas de les observer dans la mobilité incessante de leur physionomie, dans la variété d’expressions, d’attitudes et de mouvements que leur imprimaient le jeu, le désir, le mécontentement, la satisfaction, le sommeil. Il y a là des notations qui ne seraient pas déplacées au Louvre, à côté des feuilles de croquis d’un Watteau.” This and subsequent translations are my own unless otherwise noted. Unbeknownst to the reviewer, Renoir had fathered two illegitimate children in his late twenties with the model Lise Tréhot; see White, Renoir, 40.

Included among this group was Pinning the Hat, a pastel depicting not Renoir’s biological children but two girls for whom he felt paternal affection: Julie Manet (1878–1966), daughter of the artist Berthe Morisot (1841–95), and Paulette Gobillard (1867–1946), Julie’s cousin.4White identifies Julie’s companion as Jeannie Gobillard, Paulette’s younger sister; see White, Renoir, 207. However, she is the exception. Scholarly consensus is that Paulette posed for this genre portrait. See, for example, John Rewald, ed., Renoir Drawings (New York: H. Bittner, 1946), 22; and Frances Carey and Antony Griffiths, From Manet to Toulouse-Lautrec: French Lithographs 1860-1900: Catalogue of an Exhibition at the Department of Prints and Drawings in the British Museum, exh. cat. (London: British Museum, 1978), 71. Although this composition was familiar to the public thanks to Renoir’s treatment of the same subject in other media, discussed below, the Durand-Ruel survey constituted the first time that the pastel was publicly displayed.

Renoir and Morisot had struck up a friendship in 1874, after presenting their work together at the first Impressionist exhibition. Despite their different class backgrounds and Renoir’s initial secrecy about his personal life, they remained close for over twenty years.5While Renoir was too poor to afford his own apartment until 1881, at the age of forty, Morisot was firmly upper class. Renoir did not disclose his relationship with Aline Charigot (1859–1915) or the birth of their son Pierre (1885–1952) to Morisot until 1891, by which time Renoir and Aline had been married for a year and Pierre was six years old. See White, Renoir, 101, 134, 151. In addition to attending weekly dinner parties at Morisot’s apartment in Neuilly-sur-Seine and visiting her vacation estate in Mézy-sur-Seine, Renoir helped her cope with the loss of her husband, Eugène Manet, in 1892. He also developed a bond with Morisot’s only child. Julie’s diary is replete with praise for Renoir, whom she considered “so kind and so charming,” and the artist’s extant correspondence attests to his fondness for her.6Julie Manet, Growing Up with the Impressionists: The Diary of Julie Manet, trans. and ed. Rosalind de Boland Roberts and Jane Roberts (London: Sotheby’s Publications, 1987), 69 (entry dated October 4, 1895). When Renoir wrote to Morisot announcing the birth of his son Jean (1894–1979), he signed the letter: “Regards to the sweet and charming Julie and to the no less charming mother.”7Pierre-Auguste Renoir to Berthe Morisot, September 17, 1894, quoted in White, Renoir, 170. “Amitié à la douce et charmante Julie et à la non moins agréable maman.” Translation by White. After Morisot died suddenly of influenza in 1895, Renoir and Julie’s relationship only grew stronger. Renoir invited Julie and her Gobillard cousins, also orphans, to dine at his house and accompany his family on holidays in Brittany, Essoyes, and Saint-Cloud.8White, Renoir, 182. They saw each other most regularly between the early 1890s and 1900, when Julie married the painter Ernest Rouart (1874–1942).

Indeed, the very act of decorating headwear conjures up an adult female world of consumerism and self-fashioning. With the advent of the French department store in 1852 and the increased buying power of an upwardly mobile bourgeoisie, the Parisian garment trade expanded greatly during the late nineteenth century.13This paragraph’s social history is indebted to Simon Kelly, “‘Silk and Feather, Satin and Straw’: Degas, Women, and the Paris Millinery Trade,” in Simon Kelly and Esther Bell, Degas, Impressionism, and The Paris Millinery Trade, exh. cat. (San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 2017), 17–49. During the 1890s, magazines such as La Modiste universelle advertised the latest hat trends and promoted shopping as a quintessentially modern activity for women. High-end milliners such as Esther Meyer sold hats for between one hundred and 150 francs, while department stores offered cheaper alternatives for thirty francs or less. Another affordable option was to purchase an unembellished hat and adorn it each season with new flowers, feathers, lace, or even stuffed birds. Julie Manet came from a wealthy family and had the means to buy pre-trimmed hats, but there was clearly a social element to decorating them with her older cousin.

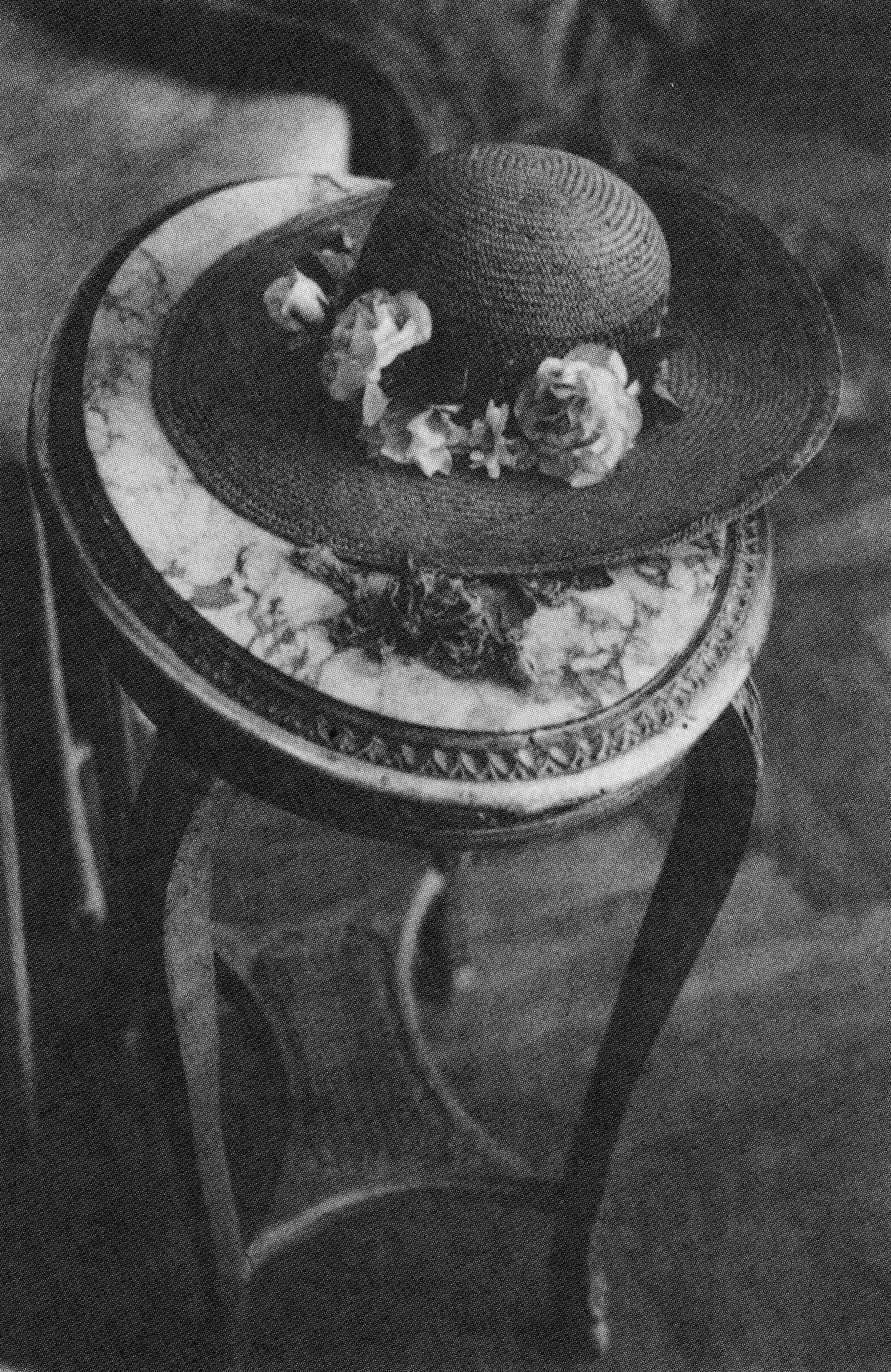

Renoir, on the other hand, hailed from a lower-class background and struggled to stay afloat for the first thirty years of his career. Despite his precarious finances, however, Renoir seems to have indulged a weakness for women’s accessories. The painter Suzanne Valadon (1865–1938), who modeled for Renoir in the 1880s, claimed that “he never ceased buying lots of hats.”14Gustave Coquiot, Renoir (Paris: A. Michel, 1925), 97. “[I]lne cessait pas d’acheter beaucoup de chapeaux.” Likewise, Jeanne Baudot (1877–1957), Renoir’s only student and the godmother to his son Jean, recalled patronizing Esther Meyer’s boutique with Renoir in the mid-1890s, when the artist had achieved some material success.15Jeanne Baudot, Renoir: Ses amis, ses modèles (Paris: Editions Littéraires de France, 1949), 15. An undated photograph of Renoir’s studio confirms his penchant for ladies’ headwear (Fig. 2). Resting atop an oval end table is a straw hat bedecked with artificial blooms and bearing a close resemblance to Julie’s chapeau in Pinning the Hat. Like Edgar Degas (1834–1917) and other artists who specialized in painting the female figure, Renoir prized hats for their ornamental value, but he also admired their craftsmanship. Several of his relatives were active in the garment industry: his father was a tailor; his mother and grandmother earned money as seamstresses; and his mother-in-law found employment as a dressmaker. Their various trades, as well as Renoir’s own experience working for the Lévy porcelain factory as a young teenager, persuaded him that handcrafted wares were superior to machine-made merchandise.16White, Renoir, 15, 78.

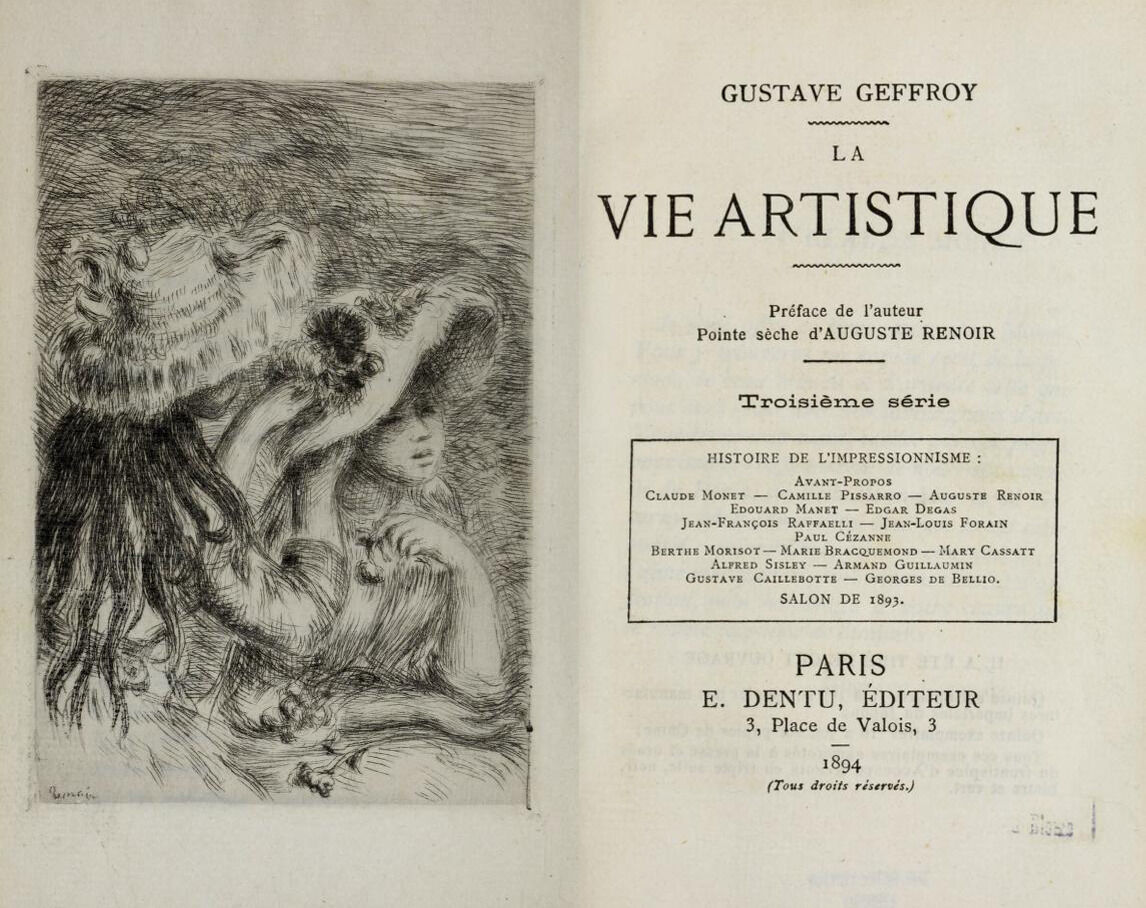

A few years after the publication of Geffroy’s book, the art dealer Ambroise Vollard commissioned Renoir to recreate Pinning the Hat as a lithograph, both in monochrome and in color. Although Renoir had a longstanding partnership with Durand-Ruel, it did not prevent him from occasionally selling work through other galleries or cooperating with rival dealers on specific projects.17Over the years, Renoir and Vollard grew quite close. Renoir even confided the existence of his illegitimate daughter to him, something he never shared with Durand-Ruel. See White, Renoir, 206. The color version, on which Renoir collaborated with Vollard’s printer, Auguste Clot (1858–1936), was not only a virtuoso example of a relatively new technique but also a highly saleable image produced in an edition of two hundred (Fig. 4).18Caroline Joubert et al., L’estampe impressionniste: Trésors de la Bibliothèque nationale de France de Manet à Renoir (Paris: Somogy, 2010), 138. For a detailed explanation of Renoir and Clot’s process, see Lemonedes, “Renoir’s Drawings and Prints,” 238. Oriented the same way as the Nelson-Atkins pastel, it nevertheless differs in significant ways. The placement of Paulette’s right arm is less convincing in the lithograph, and details such as the polka dot pattern of her dress were sacrificed. Although the addition of color represented a significant advance in printmaking for the time, the muted ocher and coquelicot (poppy-red) of the lithograph lack the luminosity of the Nelson-Atkins pastel. Even so, the print proved “wildly appealing” to bourgeois collectors.19Lemonedes, “Renoir’s Drawings and Prints,” 238.

Notes

-

Claude Monet introduced Renoir to Durand-Ruel in 1872. The dealer represented him for almost fifty years and organized his first solo exhibition of paintings in April 1883. See Barbara Ehrlich White, Renoir: An Intimate Biography (London: Thames and Hudson, 2017), 54, 122.

-

White, Renoir, 158, 280, 321.

-

T.-S., “Art et curiosité: Une exposition de dessins de Renoir,” Le Temps, April 6, 1921. “[C]es dessins ont été exécutés presque tout dans la seconde partie de sa carrière, à l’heure où, devenu père sur le tard, et un père passionnément épris de ses enfants, Renoir ne se lassait pas de les observer dans la mobilité incessante de leur physionomie, dans la variété d’expressions, d’attitudes et de mouvements que leur imprimaient le jeu, le désir, le mécontentement, la satisfaction, le sommeil. Il y a là des notations qui ne seraient pas déplacées au Louvre, à côté des feuilles de croquis d’un Watteau.” This and subsequent translations are my own unless otherwise noted. Unbeknownst to the reviewer, Renoir had fathered two illegitimate children in his late twenties with the model Lise Tréhot; see White, Renoir, 40.

-

White identifies Julie’s companion as Jeannie Gobillard, Paulette’s younger sister; see White, Renoir, 207. However, she is the exception. Scholarly consensus is that Paulette posed for this genre portrait. See, for example, John Rewald, ed., Renoir Drawings (New York: H. Bittner, 1946), 22; and Frances Carey and Antony Griffiths, From Manet to Toulouse-Lautrec: French Lithographs 1860-1900: Catalogue of an Exhibition at the Department of Prints and Drawings in the British Museum, exh. cat. (London: British Museum, 1978), 71.

-

While Renoir was too poor to afford his own apartment until 1881, at the age of forty, Morisot was firmly upper class. Renoir did not disclose his relationship with Aline Charigot (1859–1915) or the birth of their son Pierre (1885–1952) to Morisot until 1891, by which time Renoir and Aline had been married for a year and Pierre was six years old. See White, Renoir, 101, 134, 151.

-

Julie Manet, Growing Up with the Impressionists: The Diary of Julie Manet, trans. and ed. Rosalind de Boland Roberts and Jane Roberts (London: Sotheby’s Publications, 1987), 69 (entry dated October 4, 1895).

-

Pierre-Auguste Renoir to Berthe Morisot, September 17, 1894, quoted in White, Renoir, 170. “Amitié à la douce et charmante Julie et à la non moins agréable maman.” Translation by White.

-

White, Renoir, 182.

-

Some scholars identify Julie as the brunette in the lace bonnet and Paulette as her strawberry-blonde companion in the straw hat. See Starr Figura, catalogue entry for Renoir’s Pinning the Hat, in Deborah Wye, ed., Artists and Prints: Masterworks from The Museum of Modern Art (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2004), 35; and Heather Lemonedes, “Renoir’s Drawings and Prints,” in Sounjou Seo, ed., Renoir: A Promise of Happiness, exh. cat. (Seoul: Seoul Museum of Art, 2009), 235–39, at 238. However, Julie’s reddish hair is known from numerous paintings by Morisot, including Le Cerisier, 1891, oil on canvas, 60 5/8 x 33 1/16 in. (154 x 84 cm), Musée Marmottan, Paris, which is contemporary with Pinning the Hat. Julie was also eleven years Paulette’s junior, so she was more likely to seek help with hat decoration from her older cousin.

-

During his six-decade career, Renoir produced 4,019 paintings but only 148 pastels. See White, Renoir, 10.

-

Marie Lhébrard, “Notes on the Works,” in Unmasking Vollard: His Legacy of the Avant Garde, exh. cat. (Singapore: Capricorn Media, 2000), 130.

-

For more on this photograph, see “Recent Acquisitions, A Selection: 2000–2001,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 59, no. 2 (Fall 2001): 45.

-

This paragraph’s social history is indebted to Simon Kelly, “‘Silk and Feather, Satin and Straw’: Degas, Women, and the Paris Millinery Trade,” in Simon Kelly and Esther Bell, Degas, Impressionism, and The Paris Millinery Trade, exh. cat. (San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 2017), 17–49.

-

Gustave Coquiot, Renoir (Paris: A. Michel, 1925), 97. “[I]l ne cessait pas d’acheter beaucoup de chapeaux.”

-

Jeanne Baudot, Renoir: Ses amis, ses modèles (Paris: Editions Littéraires de France, 1949), 15.

-

White, Renoir, 15, 78.

-

Over the years, Renoir and Vollard grew quite close. Renoir even confided the existence of his illegitimate daughter to him, something he never shared with Durand-Ruel. See White, Renoir, 206.

-

Caroline Joubert et al., L’estampe impressionniste: Trésors de la Bibliothèque nationale de France de Manet à Renoir (Paris: Somogy, 2010), 138. For a detailed explanation of Renoir and Clot’s process, see Lemonedes, “Renoir’s Drawings and Prints,” 238.

-

Lemonedes, “Renoir’s Drawings and Prints,” 238.

-

See Exhibition of Paintings: Edouard Manet, Pierre Renoir, Berthe Morisot, exh. cat. ([Pittsburgh]: [Department of Fine Arts, Carnegie Institute], [1924]), cat. no. 34.

-

See technical notes by Nancy Heugh, Heugh-Edmondson Conservation Services, December 27, 2016, NAMA conservation files.

-

T.-S., “Art et curiosité,” 3. “Mais par-dessus tout, il y a le charme et, comme dit le poète, la grâce, plus belle encore que la beauté.” Emphasis in the original.

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Rachel Freeman, “Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Pinning the Hat, 1890 or 1893,” technical entry in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.656.2088

MLA:

Freeman, Rachel. “Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Pinning the Hat, 1890 or 1893,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.656.2088.

Executed on a cream laid paperlaid paper: One of the two types of paper. Laid papers are machine or handmade papers, formed on a screen with parallel and tightly spaced wires that form "laid lines" which are visible on the sheet. The laid wires are held together by more widely spaced wires called "chain" lines. In handmade papermaking, the chain wires also secured the screen to the ribs of a wooden frame (the frame and wire assembly is referred to as a mold) that was dipped into a vat of paper-making fibers. In the late eighteenth century, there were widespread changes in the laid mold structure, and papers produced prior to this time are distinguishable by an accumulation of fibers along the chain lines. The other type of paper is wove paper.,1The description of paper color/texture/thickness follows the standard set forth in Elizabeth Lunning and Roy Perkinson, The Print Council of America Paper Sample Book: A Practical Guide to the Description of Paper (Boston: Print Council of America, 1996), unpaginated. Pinning the Hat is a pastelpastel: A type of drawing stick made from finely ground pigments or other colorants (dyes), fillers (often ground chalk), and a small amount of a polysaccharide binder (gum arabic or gum tragacanth). While many artists made their own pastels, during the nineteenth century, pastels were sold as sticks, pointed sticks encased in tightly wound paper wrappers, or as wood encased pencils. Pastels can be applied dry, dampened, or wet, and they can be manipulated with a variety of tools including paper stumps, chamois cloth, brushes, or fingers. Pastel can also be ground and applied as a powder, or mixed with water to form a paste. Pastel is a friable media, meaning that it is powdery or crumbles easily. To overcome this difficulty, artists have used a variety of fixatives to prevent image loss. painting in which Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919) contrasts color palette and pastel painting technique to emphasize the juxtaposition of his sitters: Julie Manet, facing the viewer, and Paulette Gobillard, who places a red flower in Julie’s hat. Renoir also rendered the composition as an oil painting and later produced etchingsetching: An intaglio printmaking technique where lines are etched with acid into a metal printing plate. The printing plate is covered with an acid resistant ground, and the artist draws a design into the ground with an etcher’s needle (a sharply pointed stylus). The plate is then immersed in an acid bath, and the metal exposed by the needle is eaten away. After removal of the ground, the plate can be printed by rubbing ink into the etched lines and running the plate and printing paper through an intaglio press. and lithographslithography: Invented by Alois Senefelder (German, 1771–1834) in the late eighteenth century, lithography is a planographic printmaking technique. The name (literally: stone drawing) comes from the use of a stone as the printing matrix; however, grained aluminum and metal plates are also used. Preparation and printing of the images is a based on the hydrophobic nature of grease. The design is drawn with greasy crayons or an oily ink called tusche. The stone is then synthesized so that printing can be accomplished by first wetting the stone (the water is repelled by the grease in the media) and then inking the stone with a greasy ink (the ink adheres grease in the crayon and tusche). The image is transferred to the paper with a press that exerts tremendous pressure on the stone. Like other printing techniques the printed image reverses the image on the stone. There is no platemark as seen in monotypes; instead the area of contact between the stone and the paper will have a flatter appearance than the surrounding paper.; an examination of one of the lithographs provides insight into the pastel painting’s original format.

Fig. 7. The L. BERVILLE watermark, located at upper right, from Pinning the Hat (1890 or 1893). The Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI) representation enhances both the laid texture of the paper and the block letters of the watermark. Courtesy of R. Bruce North

Fig. 7. The L. BERVILLE watermark, located at upper right, from Pinning the Hat (1890 or 1893). The Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI) representation enhances both the laid texture of the paper and the block letters of the watermark. Courtesy of R. Bruce North

Fig. 8. Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI) representation of the Lalanne watermark from Pinning the Hat (1890 or 1893), in script, at lower left. Courtesy of R. Bruce North

Fig. 8. Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI) representation of the Lalanne watermark from Pinning the Hat (1890 or 1893), in script, at lower left. Courtesy of R. Bruce North

Two watermarkswatermark: An identifying mark in a paper sheet which is created by tying wires to the papermaking mold. Watermarks are most easily viewed with transmitted light; however, some can be read with raking light. are present on the original support paper: “L. BERVILLE” (Fig. 7), oriented vertically in block letters along the edge at upper right; and “Lalanne” (Fig. 8), also oriented vertically, but in script, at the lower left edge. Léon Berville (b. 1837) was an artist supplierartist supplier(s): Also called colormen and color merchants. Artist suppliers prepared materials for artists. This tradition dates back to the Medieval period, but the industrialization of the nineteenth century increased their commerce. It was during this time that ready-made paints in tubes, commercially prepared canvases, and standard-format supports were available to artists for sale through these suppliers. It is sometimes possible to identify the supplier from stamps or labels found on the reverse of the artwork. See also canvas stamp, supplier mark, and *color merchant. and picture dealer with premises at 25 rue de la Chaussée-d’Antin, Paris. Lalanne refers to François Antoine Maxime Lalanne (1827–86), a Parisian artist known for his mastery of charcoal and etching.4In nineteenth-century France, papers named for artists often include a watermark with the artist’s name in script. A well-known example of this convention is the Ingres paper made by a consortium of mills under the Arches company name. Like Berville’s Lalanne marked paper, Ingres is often a laid paper with a texture that is suitable for pastel, chalk, or charcoal. The paper is named for the French artist Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780–1867). Berville published and sold Lalanne’s treatise on charcoal drawing, Le Fusain, and a listing for a Lalanne watermarked paper appears in the back pages as “Papier vergé spécial, marque Lalanne.”5The back pages of artists’ manuals typically included a catalogue of artists’ materials discussed in the treatise. Maxime Lalanne, Le Fusain (Paris: Leon Berville, 1875), 33, https://archive.org/details/lefusain00lala/page/33/mode/2up. There is also a description of the paper, with a reference to an unwatermarked version of the paper and a reassurance that Berville’s Lalanne marked papers were consistently high in quality:

We have specially manufactured, on precise data of texture, shades and sizing, a kind of Lalanne brand laid paper, combining all the desirable qualities, with the advantage of having a mark only at the edge of the paper, which gives the entire sheet perfect uniformity. This paper exists in two strengths [a reference to the paper’s weight or thickness] and four shades; it measures 60 by 50 cm. Its texture, very homogeneous, holds the charcoal, while also releasing it completely to the bread crumb [bread was used as an eraser] or to the stump [a blending tool], and allows full and nuanced work alongside extremely fine detail.6The author is grateful to Michelle Sullivan, associate conservator, department of paper conservation, J. Paul Getty Museum, for the reference; see Lalanne, Le Fusain, 35, https://archive.org/details/lefusain00lala/page/35/mode/2up.

“Nous faisons fabriquer spécialement, sur des données précises de grains, de nuances et de collage, une sorte de papier vergé marque Lalanne, réunissant toutes les qualités désirables, avec l’avantage de n’avoir de marque qu’au bord du papier, ce qui donne à l’étendue de la feuille une uniformité parfaite. Ce papier existe de deux forces et de quatre nuances; il mesure 0m,60 sur 0m,50. Son grain, très-homogène, accroche le fusain en l’abandonnant complètement à la mie de pain ou à l’estompe, et permet des travaux pleins et nourris à côté de finesses extrêmes.”

Any mistakes or inconsistencies in the translation are the fault of the author.

Pinning the Hat is not the only instance of Renoir’s use of Berville’s charcoal paper. The artist produced a series of drawings to illustrate the publication L’etiquette in the early 1880s. Renoir took exception to the papers supplied by the publisher, complaining that the papers were “disagreeable” because erasure was impossible and highlights had to be scraped into the paper.7“Cats. 12–13. Illustrations for ‘L’étiquette’: Curatorial Entry,” in Renoir Paintings and Drawings at the Art Institute of Chicago, eds. Gloria Groom and Jill Shaw (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2014), para. 12, https://publications.artic.edu/renoir/reader/paintingsanddrawings/section/139332/p-139332-12. Perhaps the papers frustrated the artist to the point that he substituted a half sheet of L. Berville watermarked paper for The Descent from the Summit: Jean Martin Steadies Hélène the Bankers Daughter (1881; The Art Institute of Chicago).8Kimberly Nichols, “Cat. 13 The Descent from the Summit, 1881 (recto); Half-Length Sketch of a Woman, c. 1883 (verso): Technical Report,” in Renoir Paintings and Drawings at the Art Institute of Chicago, https://publications.artic.edu/renoir/reader/paintingsanddrawings/section/135641/p-135641-5.

Although the paper for Pinning the Hat was suitable for erasure, Renoir did not employ subtractive techniques during image composition. Compositional development likely began with an underdrawingunderdrawing: A drawn or painted sketch beneath the paint layer. The underdrawing can be made from dry materials, such as graphite or charcoal, or wet materials, such as ink or paint. in vine charcoal or a pointed black pastel stick. Renoir applied the pastel over the dark lines; however, the underdrawing remains visible to the unaided eye in many areas, especially in Julie Manet’s hand, collar, and hat (Fig. 9). The artist differentiated the background and negative space between the two girls with stump-blendedstumping: Blending, removing, lightening, or softening stokes of powdery media (pastel, charcoal, chalk, or graphite pencil) with a stump or tortillon. The stump is made from paper, leather or thin felt, which is rolled so that it forms a point. If blending is the main object of stumping, then the technique is referred to as stump blending to differentiate between blending with fingers, a brush, or chamois skin., cool-toned greens and blues that create simultaneous contrastsimultaneous contrast: Simultaneous contrast is the interaction of two colors when placed side by side. Depending on the colors, the viewer’s perception of the color will change. For example, blue will cause red to appear orange, and red causes blue to appear green. Complementary colors (colors that are opposite each other in a color wheel, such as red and green, blue and orange, or yellow and purple) produce the most striking simultaneous contrast. While simultaneous contrast was formulated by the French chemist Michel Eugène Chevreul (1786–1889) in his treatise The Principles of Harmony and Contrast of Colors, and Their Applications to the Arts (1839), the use of simultaneous contrast in painting predates the treatise by more than 100 years. with the red polka-dotted fabric of Paulette’s dress. Blending is also present in the girls’ faces, dresses, and hats, but individual strokes from pointed pastel sticks emphasize details such as the lace on Paulette’s hat and her wavy hair. Renoir built up the areas of color so that much of the paper is obscured. Pentimentipentimento (pl: pentimenti): A change to the composition made by the artist that is visible on the paint surface. Often with time, pentimenti become more visible as the upper layers of paint become more transparent with age. Italian for "repentance" or "a change of mind." are present around the proper left brim of Julie’s hat and her face and chin, and the artist appears to have spent much time stumping these areas to achieve some blending of the pastel. No fixative was used on the piece, and Renoir executed the pastel painting over more than one sitting. Renoir signed the pastel painting at lower right.

As noted above, there are added strips of paper on the edges of the artwork, and creases and breaks are present where the paper was folded over a strainer or board. While the color of pastel on the paper strips is consistent with Renoir’s composition, the strokes are hurried and slightly crude when compared with the pastel application on the two young women and are uniformly executed with blunt pastel stick.

The pastel painting is in good and stable condition overall. The outermost cardboard backing retains some of the blue papers that are often seen on the back of French nineteenth-century pastels. It also has some small nail holes at the edges from past reframing campaigns. Nancy Heugh treated the painting for mold hyphae in 2017.12Nancy Heugh, December 27, 2016, treatment report, NAMA conservation file, no. 2015.13.20. Otherwise, there is no documented conservation of the artwork.

Notes

-

The description of paper color/texture/thickness follows the standard set forth in Elizabeth Lunning and Roy Perkinson, The Print Council of America Paper Sample Book: A Practical Guide to the Description of Paper (Boston: Print Council of America, 1996), unpaginated.

-

Use of Berville and Lalanne marked papers can be traced to Paul Gauguin (1848–1903), John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925), and lesser-known artists such as John Douglas Patrick (American, 1863–1937). At some point in the late nineteenth century “(FRANCE)” was added to the L. Berville portion of the mark. See Harriet K. Stratis with scientific analysis by Céline Daher, “Gauguin, Cat. 3, Seated Breton Woman (1933.910): Technical Study,” in Gauguin Paintings, Sculpture, and Graphic Works at the Art Institute of Chicago, eds. Gloria Groom and Genevieve Westerby (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2016), para 7, https://publications.artic.edu/gauguin/reader/gauguinart/section/140227/p-140227-7; John Singer Sargent, Study for Belgium, for “Coming of the Americans,” Widener Library, Harvard University, 1921–22, charcoal on off-white laid paper, 18 7/8 x 24 7/8 in. (47.9 x 63.2 cm), Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, gift of Miss Emily Argent and Ms. Francis Ormond in memory of their brother, John Singer Sargent, 1930.452; John Douglas Patrick, Older Black Woman, Frontal, undated, charcoal on paper 24 5/8 x 18 5.16 in. (62.56 x 46.51 cm), The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, gift of the families of Grayce Patrick Wray and Hazel Patrick Rickenbacher, daughters of the artist from the collection of Cherie Wray Smith and Pattie Rickenbacher Hogan in honor of the 75th Anniversary of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2009.47.1.

-

Like painting canvases, French papers were available in a variety of standard sizes during the nineteenth century. These were not the standard sizes used throughout the world (except in the United States and Canada) today, but they were unique to France. For further information of paper size standardization, see E. J. Labarre, A Dictionary of Paper and Paper-Making Terms with Equivalents in French, German, Dutch and Italian (Amsterdam: N.V. Swets and Zeitlinger, 1937), 228–38.

-

In nineteenth-century France, papers named for artists often include a watermark with the artist’s name in script. A well-known example of this convention is the Ingres paper made by a consortium of mills under the Arches company name. Like Berville’s Lalanne marked paper, Ingres is often a laid paper with a texture that is suitable for pastel, chalk, or charcoal. The paper is named for the French artist Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780–1867).

-

The back pages of artists’ manuals typically included a catalogue of artists’ materials discussed in the treatise. Maxime Lalanne, Le Fusain (Paris: Leon Berville, 1875), 33, https://archive.org/details/lefusain00lala/page/33/mode/2up.

-

The author is grateful to Michelle Sullivan, associate conservator, department of paper conservation, J. Paul Getty Museum, for the reference; see Lalanne, Le Fusain, 35, https://archive.org/details/lefusain00lala/page/35/mode/2up. “Nous faisons fabriquer spécialement, sur des données précises de grains, de nuances et de collage, une sorte de papier vergé marque Lalanne, réunissant toutes les qualités désirables, avec l’avantage de n’avoir de marque qu’au bord du papier, ce qui donne à l’étendue de la feuille une uniformité parfaite. Ce papier existe de deux forces et de quatre nuances; il mesure 0m,60 sur 0m,50. Son grain, très-homogène, accroche le fusain en l’abandonnant complètement à la mie de pain ou à l’estompe, et permet des travaux pleins et nourris à côté de finesses extrêmes.” Any mistakes or inconsistencies in the translation are the fault of the author.

-

“Cats. 12–13. Illustrations for ‘L’étiquette’: Curatorial Entry,” in Renoir Paintings and Drawings at the Art Institute of Chicago, eds. Gloria Groom and Jill Shaw (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2014), para 12, https://publications.artic.edu/renoir/reader/paintingsanddrawings/section/139332/p-139332-12.

-

Kimberly Nichols, “Cat. 13, The Descent from the Summit, 1881 (recto); Half-Length Sketch of a Woman, c. 1883 (verso): Technical Report,” in Renoir Paintings and Drawings at the Art Institute of Chicago, https://publications.artic.edu/renoir/reader/paintingsanddrawings/section/135641/p-135641-5.

-

Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 94–98. Two years prior to the publication of the Bloch collection catalogue, the Adelson Galleries exhibited a number of Renoir counterproofs and published an exhibition catalogue: Renoir: The Pastel Counterproofs (New York: Adelson Galleries, 2005). Catalogue number 18, Les Petites Filles au chapeau (Vollard 1100), is a counterproof of a composition similar to Pinning the Hat (1890 or 1893), and is identified as a study for the transfer lithographs of The Pinned Hat. It is possible that the authors, Warren Adelson, Marc Rosen, and Susan Pinsky, were unaware of the pastel now in the collection of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

-

Antoinette Owen, “Cat. 1, Seated Nude: Technical Report,” in Manet Paintings and Works on Paper at the Art Institute of Chicago, eds. Gloria Groom and Genevieve Westerby (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2017), para 6, https://publications.artic.edu/manet/reader/manetart/section/140027/p-5/p-140027-6.

-

Loys Delteil, Pierre-Auguste Renoir: L’Œuvre gravé et lithographié/The Etchings and Lithographs; Catalogue Raisonné, ed. Alan Hyman (San Francisco: Alan Wolfsy Fine Arts, 1999), no. 29, pp. 60–61. The author is grateful to Laura Neufeld, associate paper conservator, The David Booth Conservation Department, The Museum of Modern Art, for descriptions of transfer lithographs of The Flowered Hat in that collection. The descriptions helped the author properly identify the paper and the state of the print.

-

Nancy Heugh, December 27, 2016, treatment report, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, no. 2015.13.20.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Pinning the Hat, 1890 or 1893,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.656.4033

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Pinning the Hat, 1890 or 1893,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.656.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Pinning the Hat, 1890 or 1893,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.656.4033

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Pinning the Hat, 1890 or 1893,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.656.4033.

With the artist, Paris and Les Collettes, near Cagnes-sur-Mer, France, 1890–December 3, 1919;

Inherited by the artist’s family, Les Collettes, near Cagnes-sur-Mer, France, 1919–October 1922 [1];

By descent to the artist’s son, Pierre Renoir (1885–1952), Paris and Les Collettes, near Cagnes-sur-Mer, France, 1922–at least October 7, 1928 [2];

Possibly with Galerie Alfred Flechtheim, Düsseldorf, Berlin, Cologne and Frankfurt, Germany, by October 1928 [3];

Private collection, U.S., by 1929;

With James Vigeveno Galleries, Los Angeles, photo book 20, no. 1460, as Le Chapeau epinglé [sic], by July 1954 [4];

Purchased from James Vigeveno Galleries by George I. (d. 1984) and Myna Friedland (née Siegel, 1912–95), Merion, PA, July 1954–69;

To Myna Brady (formerly Mrs. George Friedland), by 1969–October 27, 1976 [5];

Purchased from Myna Brady (formerly Mrs. George Friedland) through John and Paul Herring and Co., New York, by Marion (née Helzberg, 1931–2013) and Henry (1922–2019) Bloch, Shawnee Mission, KS, 1976–present [6];

Their gift to The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 2015.

Notes

[1] Distribution of Renoir’s paintings among his three sons did not occur until October 1922, a few months after the youngest son, Claude, came of age. Accordingly, an itemized inventory of Renoir’s paintings titled “Partage par lots” was drawn up, presumably with an indication of which painting went to which son. The “Partage par lots” is undated, however, a typed letter dated August 8, 1922 from Pierre Renoir to his cousin Eugéne suggests that it was drawn up in October 1922; see The Unknown Renoir: The Man, The Husband, The Father, The Artist, Heritage Auctions, New York, September 19, 2013, lot 89007. Unfortunately, this document is not currently accessible to scholars.

[2] A photograph of this pastel in Julius Meier-Graefe, Renoir (Leipzig: Klinkhardt and Biermann Verlag, 1929), 261, is credited to Galerie Alfred Flechtheim, while the caption describes the pastel as being in a private U.S. collection. In the illustration index, the pastel is listed in Pierre Renoir’s collection.

[3] See footnote 2. The pastel was probably on exhibition at Galerie Alfred Flechtheim from October 7-November 9, 1928. It is possible that Pierre Renoir sold the pastel to Flechtheim who in turn sold the pastel to an American collector by 1929. According to Laurie Stein, President, L. Stein Art Research LLC, Chicago, and Senior Advisor for the Provenance Research Initiative at the Smithsonian Institution, Flechtheim records do not survive. See correspondence from Mackenzie Mallon to Laurie Stein, May 2015, NAMA curatorial files.

[4] See stock card, James Vigeveno Galleries records, 1940–75, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC

[5] George I. Friedland and Myna Friedland (née Siegel) married in 1946. Around March 1965, Mr. Friedland left the common home and moved to St. Thomas, Virgin Islands. On February 10, 1966, Mrs. Friedland filed for divorce. After a series of legal injunctions it appears the appeal was taken to the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania (January Term 1969, No. 213). According to the Laurence H. Eldredge Papers, The University of Archives and Records center, University of Pennsylvania, a divorce was granted by the opinion of the court in 1969. Myna Brady (formerly Mrs. George Friedland) married Samuel P. Brady in 1971.

[6] In a telephone call with MacKenzie Mallon on May 7, 2015, John Herring relayed that John and Paul Herring and Co. had the pastel on consignment from Myna Brady (formerly Friedland).

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Pinning the Hat, 1890 or 1893,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.656.4033

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Pinning the Hat, 1890 or 1893,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.656.4033.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Le chapeau épinglé, 1893, pastel on paper (?), illustrated in Guy-Patrice et Michel Dauberville, Renoir: Catalogue Raisonné des Tableaux, Pastels, Dessins et Aquarelles (Paris: Éditions Bernheim-Jeune, 2007), no. 1417, p. 2:460, (repro.), as Le Chapeau épinglé.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Le chapeau épinglé, 1893, pastel on paper (?), illustrated in Guy-Patrice et Michel Dauberville, Renoir: Catalogue Raisonné des Tableaux, Pastels, Dessins et Aquarelles (Paris: Éditions Bernheim-Jeune, 2007), no. 1418, p. 2:461, (repro.), as Le Chapeau épinglé.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Les deux fillettes, 1893, oil on canvas, 25 9/16 x 21 4/16 in. (65 x 54 cm), Emil Bührle Collection, Zürich.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, The Hat Secured with a Pin (Le chapeau épinglé), 1894, etching, first version, 4 9/16 x 3 4/16 in. (11.6 cm x 8.2 cm), Cabinet des Estampes, Bibliothéque de l’Université, Paris.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, The Hat Secured with a Pin (Le chapeau épinglé), 1894, etching, second version, first state, 6 3/8 x 5 1/8 in. (16.2 x 13 cm), Bibliothéque Nationale, Paris.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, The Hat Secured with a Pin (Le chapeau épinglé), 1894, etching, second version, second state, 4 5/16 x 3 5/16 in. (10.9 x 8.4 cm), Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, The Hat Secured with a Pin (Le chapeau épinglé), 1894, etching, third version, first state, 4 8/16 x 3 2/16 in. (11.5 x 8 cm), Bibliothéque Nationale, Paris.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, The Hat Secured with a Pin (Le chapeau épinglé), 1894, etching, third version, second state, 4 8/16 x 3 2/16 in. (11.5 x 8 cm), Bibliothéque Nationale, Paris.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Le chapeau épinglé, 1895–97, oil on canvas, 10 5/8 x 9 in. (27 x 23 cm), illustrated in Ambroise Vollard, Tableaux Pastels et Dessins de Pierre-Auguste Renoir (Paris: Ambroise Vollard, 1918), 2:79. (repro.).

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, The Pinned Hat, 1897, lithograph on laid paper, first version, sheet: 30 13/16 × 22 7/16 in. (78.2 × 57 cm), image: 23 5/8 × 18 7/8 in. (60 × 48 cm), The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, The Hat Secured with a Pin (Le chapeau épinglé), 1898, lithograph on off-white laid paper, second version, 24 3/16 x 19 9/16 in. (61.5 x 49.7 cm), Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, The Hat Secured with a Pin and Woman Bathing (Le chapeau épinglé et la Baigneuse), 1905, 10 6/16 x 12 11/16 in. (26.4 x 32.2 cm), lithograph in black on thick grayish-ivory wove paper, The Art Institute of Chicago.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Pinning the Hat, 1890 or 1893,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.656.4033

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Pinning the Hat, 1890 or 1893,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.656.4033.

Aquarelles, pastels et dessins par Renoir (1841–1919), Galeries Durand-Ruel, Paris, April 4–23, 1921, no. 39, as Jeunes filles arrangeant un chapeau.

Probably Renoir, Galerie Alfred Flechtheim, Berlin, October 7–November 9, 1928, no. 35, as Die Hüte.

Possibly Werke von Auguste Renoir aus Winterthurer Privatbesitz, Kunstverein Winterthur, Winterthur, March 17–April 22, 1935, no. 59, as Le chapeau épinglé.

Possibly Modern French Paintings: New Acquisitions, James Vigeveno Gallery, Los Angeles, June 20–August 31, 1954, unnumbered.

The Bloch Collection, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, June–August 1982, no cat.

Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, June 9–September 9, 2007, no. 17, as The Flowered Hat (Le chapeau épinglé).

Painters and Paper: Bloch Works on Paper, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, February 20, 2017–March 11, 2018, no cat.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Pinning the Hat, 1890 or 1893,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.656.4033

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Pinning the Hat, 1890 or 1893,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.656.4033.

Possibly Ambroise Vollard, Tableaux, Pastels et Dessins de Pierre-Auguste Renoir (Paris: Ambroise Vollard, 1918), unnumbered, p. 2:87, (repro.) [repr., in Pierre-Auguste Renoir: Paintings, Pastels and Drawings (San Francisco: Alan Wofsy Fine Arts, 1989), no. 1169, p. 255].

Aquarelles, pastels et dessins par Renoir (18411919), exh. cat. (Paris: Galeries Durand-Ruel, 1921), unpaginated, as Jeunes filles arrangeant un chapeau.

Possibly Georges Rivière, Renoir et ses amis (Paris: H. Floury, 1921), 91, as Jeunes filles fleurissant leurs chapeaux.

Possibly Gustave Coquiot, Renoir (Paris: Albin Michel, 1925), 229, (repro.), as Jeunes filles fleurissant leurs chapeaux.

Probably Renoir, exh. cat. (Berlin: Galerie Alfred Flechtheim, 1928), 10, as Die Hüte.

Albert André, Renoir (Paris: G. Cres and Cie., 1928), unpaginated, (repro.), as Jeune Fille Arrangeant un Chapeau (pastel).

George Besson, Auguste Renoir (Paris: Les Éditions G. Crès et Cie, 1929), 17, unpaginated, (repro.), as Jeunes Filles au Chapeau (pastel).

Julius Meier-Graefe, Renoir (Leipzig: Klinkhardt und Biermann Verlag, 1929), 261, 443 (repro.), as Sommerhüte.

Werke von Auguste Renoir aus Winterthurer Privatbesitz, exh. cat. (Winterthur: Kunstverein Winterthur, 1935), 9, as Le chapeau épinglé.

Enrico Piceni, Auguste Renoir: 43 tavole (Milano: Ulrico Hoepli, 1945), unpaginated, (repro.), Giovinette.

John Rewald, ed., Renoir Drawings (New York: H. Bittner, 1946), 22, (repro.), as The Flowered Hat.

Possibly Modern French Paintings: New Acquisitions, exh. cat. (Los Angeles: James Vigeveno Gallery, 1954).

Masterpieces of French Painting from the Bührle Collection, exh. cat. (London: Arts Council of Great Britain, 1961), unpaginated.

Peter H. Feist, Auguste Renoir (Leipzig: Veb. E. A. Seemann, 1961), 66.

Possibly Jean Leymarie and Michel Melot, The Graphic Works of the Impressionists: Manet, Pissarro, Renoir, Cezanne, Sisley (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1972), unpaginated.

La vie parisienne: An Exhibition of French Coloured Lithographs, 18901900, exh. cat. (London: Thomas Agnew and Sons, 1972), 34.

Frances Carey and Antony Griffiths, From Manet to Toulouse-Lautrec: French lithographs 18601900: catalogue of an exhibition at the Department of Prints and Drawings in the British Museum, exh. cat. (London: British Museum, 1978), 71.

“The Bloch Collection,” Gallery Events (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) (JuneAugust 1982): unpaginated.

Nagoya-shi Bijutsukan, Renoir Retrospective, exh. cat. (Nagoya: Chunichi Shimbun, 1988), 182, 252.

Unmasking Vollard: His Legacy of the Avant Garde, exh. cat. (Singapore: Capricorn Media, 2000), 130.

Deborah Wye, Artists and Prints: Masterworks from the Museum of Modern Art (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2004), 35.

Rebecca Dimling and Bobbie Leigh, “100 Top Collectors Who Have Made a Difference,” Arts and Antiques 29, no. 3 (March 2006): 90.

Alice Thorson, “A final countdown: A rare showing of Impressionist paintings from the private collection of Henry and Marion Bloch is one of the inaugural exhibitions at the 165,000-square-foot glass-and-steel structure,” Kansas City Star (June 29, 2006): B1.

Bobbie Leigh, “Magnificent Obsession,” Art and Antiques 29, no. 6 (June 2006): 62, as The Flowered Hat.

Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 10, 15, 9499, 159, (repro.), as The Flowered Hat (Le chapeau épinglé).

“A tiny Renoir began impressive obsession Bloch collection gets its first public exhibition,” Kansas City Star (June 2, 2007): https://www.kansascity.com/latest-news/article294930/A-tiny-Renoir-began-impressive-obsession-Bloch-collection-gets-its-first-public-exhibition.html

Alice Thorson, “First Public Exhibition: Marion and Henry Bloch’s art collection: A Tiny Renoir began impressive obsession Bloch collection gets its first public exhibition-After one misstep, Blochs focused, successfully, on French paintings,” Kansas City Star (June 3, 2007): E4.

“Lasting Impressions: A Tribute to Marion and Henry Bloch,” Member Magazine (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (Fall 2007): 11, (repro.).

Guy-Patrice et Michel Dauberville, Renoir: Catalogue Raisonné des Tableaux, Pastels, Dessins et Aquarelles (Paris: Éditions Bernheim-Jeune, 2007), no. 1416, p. 2:460, (repro.), as Chapeau épinglé.

Carol Vogel, “Inside Art: Kansas City Riches,” New York Times 159, no. 54,942 (February 5, 2010): C26.

Alice Thorson, “Henry and Marion Bloch donate impressionist collection to the Nelson,” Kansas City Star (February 7, 2010): G1.

Caroline Joubert and et al., L’estampe impressionniste: trésors de la Bibliothèque nationale de France de Manet à Renoir (Paris: Somogy, 2010), 113.

A. Hyatt Mayor, Prints and People: A Social History of Printed Pictures (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2013), unpaginated.

Diane Stafford, “Bloch Gift to Go for Nelson Upgrade,” Kansas City Star 135, no. 203 (April 8, 2015): A8.

Diane Stafford, “Bloch Family Foundation Will Finance Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Renovation,” Kansas City Star (April 8, 2015): https://www.kansascity.com/entertainment/visual-arts/article17804426.html.

“Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Officially Accessions Bloch Impressionist Masterpieces,” Artdaily.org (July 25, 2015): http://artdaily.com/news/80246/Nelson-Atkins-Museum-of-Art-officially-accessions-Bloch-Impressionist-masterpieces#.V6oGwlKFO9.

Nancy Staab, “Van Gogh is a Go!” 435: Kansas City’s Magazine (September 2015): 76, (repro.), as The Flowered Hat.

“Nelson-Atkins to unveil renovated Bloch Galleries of European Art in winter 2017,” Artdaily.org (July 20, 2016): http://artdaily.com/news/88852/Nelson-Atkins-to-unveil-renovated-Bloch-Galleries-of-European-Art-in-winter-2017-#.W-nfbpNKi70.

“Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art celebrates generosity of Henry Bloch with new acquisition,” Artdaily.org (October 18, 2016): http://artdaily.com/news/90923/Nelson-Atkins-Museum-of-Art-celebrates-generosity-of-Henry-Bloch-with-new-acquisition#.XL88c-TsaUk.

Catherine Futter et al., Bloch Galleries: Highlights from the Collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2016), 89, (repro.), as The Flowered Hat.

Albert Hect, “Henry Bloch’s Masterpieces Collection to Go on Display at Nelson-Atkins Museum,” Jewish Business News (February 26, 2017): http://jewishbusinessnews.com/2017/02/26/henry-bloch-masterpieces-collection/.

David Frese, “Inside the Bloch Galleries: An interactive experience,” Kansas City Star 137, no. 169 (March 5, 2017): 1D, 4D, (repro.), as The Flowered Hat.

“Editorial: Thank you, Henry and Marion Bloch,” Kansas City Star (March 7, 2017): http://www.kansascity.com/opinion/editorials/article137040948.html.

Hampton Stevens, “(Not Actually) 12 Things To Do During The Big 12 Tournament,” Flatland: KCPT’s Digital Magazine (March 9, 2017): http://www.flatlandkc.org/arts-culture/sports/not-actually-12-big-12-tournament/.

Laura Spencer, “The Nelson-Atkins’ Bloch Galleries feature Old Masterworks and New Technology,” KCUR (March 10, 2017): http://kcur.org/post/nelson-atkins-bloch-galleries-feature-old-masterworks-and-new-technology#stream/0.

Victoria Stapley-Brown, “Nelson-Atkins Museum’s new European art galleries come with a ‘love story’,” Art Newspaper (March 10, 2017): http://theartnewspaper.com/news/museums/nelson-atkins-museum-s-new-european-art-galleries-come-with-a-love-story/.

Harry Bellet, “Don du ciel pour le Musée Nelson-Atkins,” Le Monde (March 13, 2017): http://www.lemonde.fr/arts/article/2017/03/13/don-du-ciel-pour-le-musee-nelson-atkins_5093543_1655012.html.

Menachem Wecker, “Jewish Philanthropist Establishes Kansas City as Cultural Mecca,” Forward (March 14, 2017): http://forward.com/culture/365264/jewish-philanthropist-establishes-kansas-city-as-cultural-mecca/.

Juliet Helmke, “The Bloch Collection Takes up Residence in Kansas City’s Nelson Atkins Museum,” BoulinArtInfo International, (March 15, 2017): http://www.blouinartinfo.com/news/story/2005267/the-bloch-collection-takes-up-residence-in-kansas-citys.

Erich Hatala Matthes, “Digital replicas are not soulless—they help us engage with art,” Apollo: The International Art Magazine (March 23, 2017): https://www.apollo-magazine.com/digital-replicas-3d-printing-original-artworks/.

Louise Nicholson, “How Kansas City got its magnificent museum,” Apollo (April 7, 2017): https://www.apollo-magazine.com/how-kansas-city-got-its-magnificent-museum/.

Lilly Wei, “Julián Zugazagoitia: ‘Museums should generate interest and open a door that leads to further learning’,” Studio International (August 21, 2017): http://studiointernational.com/index.php/julian-zugazagoitia-director-nelson-atkins-museum-of-art-kansas-city-interview.

Simon Kelly and Esther Bell, Degas, Impressionism, and The Paris Millinery Trade, exh. cat. (San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 2017), 240, 293, 295, (repro.), as The Flowered Hat.

Robert D. Hershey Jr., “Henry Bloch, H&R Block’s cofounder, dies at 96,” Boston Globe (April 23, 2019), https://www3.bostonglobe.com/metro/obituaries/2019/04/23/henry-bloch-block-cofounder/?arc404=true.

Robert D. Hershey Jr., “Henry W. Bloch, Tax-Preparation Pioneer (and Pitchman), Is Dead at 96,” New York Times (April 23, 2019): https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/23/obituaries/henry-w-bloch-dead.html.

Claire Selvin, “Henry Wollman Bloch, Collector and Prominent Benefactor of Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Is Dead at 96,” ArtNews (April 23, 2019): http://www.artnews.com/2019/04/23/henry-bloch-dead-96/.

“Henry Wollman Bloch (1922-2019),” Art Forum (April 24, 2019): https://www.artforum.com/news/henry-wollman-bloch-1922-2019-79547.

Frank Morris, “Henry Bloch, Co-Founder Of H&R Block, Dies At 96,” npr.org (April 24, 2019): https://www.npr.org/2019/04/24/716641448/henry-bloch-co-founder-of-h-r-block-dies-at-96.

Ignacio Villarreal, “Nelson-Atkins mourns loss of Henry Bloch,” ArtDaily.org (April 24, 2019): http://artdaily.com/news/113035/Nelson-Atkins-mourns-loss-of-Henry-Bloch#.XMB76qR7laQ.

Eric Adler, “Sold for $3.25 million, Bloch’s home in Mission Hills may be torn down,” Kansas City Star 141, no. 90 (December 16, 2020): 2A.