![]()

Camille Pissarro, Chestnut Grove at Louveciennes, 1872

| Artist | Camille Pissarro, French, 1830–1903 |

| Title | Chestnut Grove at Louveciennes |

| Object Date | 1872 |

| Alternate and Variant Titles | Bois de châtaigniers à Louveciennes; Village derrière les arbres |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (Unframed) | 16 3/8 x 21 in. (41.6 x 53.3 cm) |

| Signature | Signed and dated lower left: C. Pissarro. 1872 |

| Credit Line | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Gift of Henry W. and Marion H. Bloch, 2015.13.17 |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Camille Pissarro, Chestnut Grove at Louveciennes, 1872,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.640.5407.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Camille Pissarro, Chestnut Grove at Louveciennes, 1872,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.640.5407.

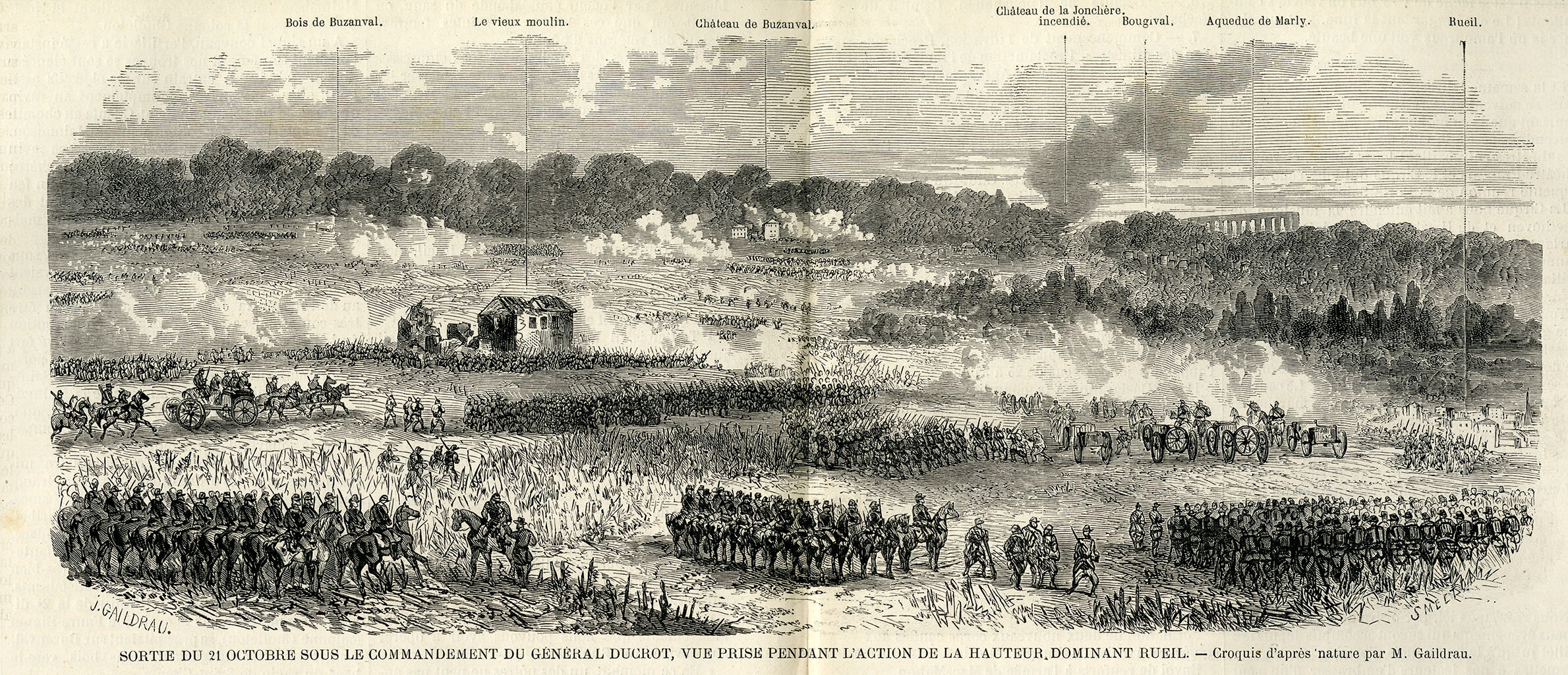

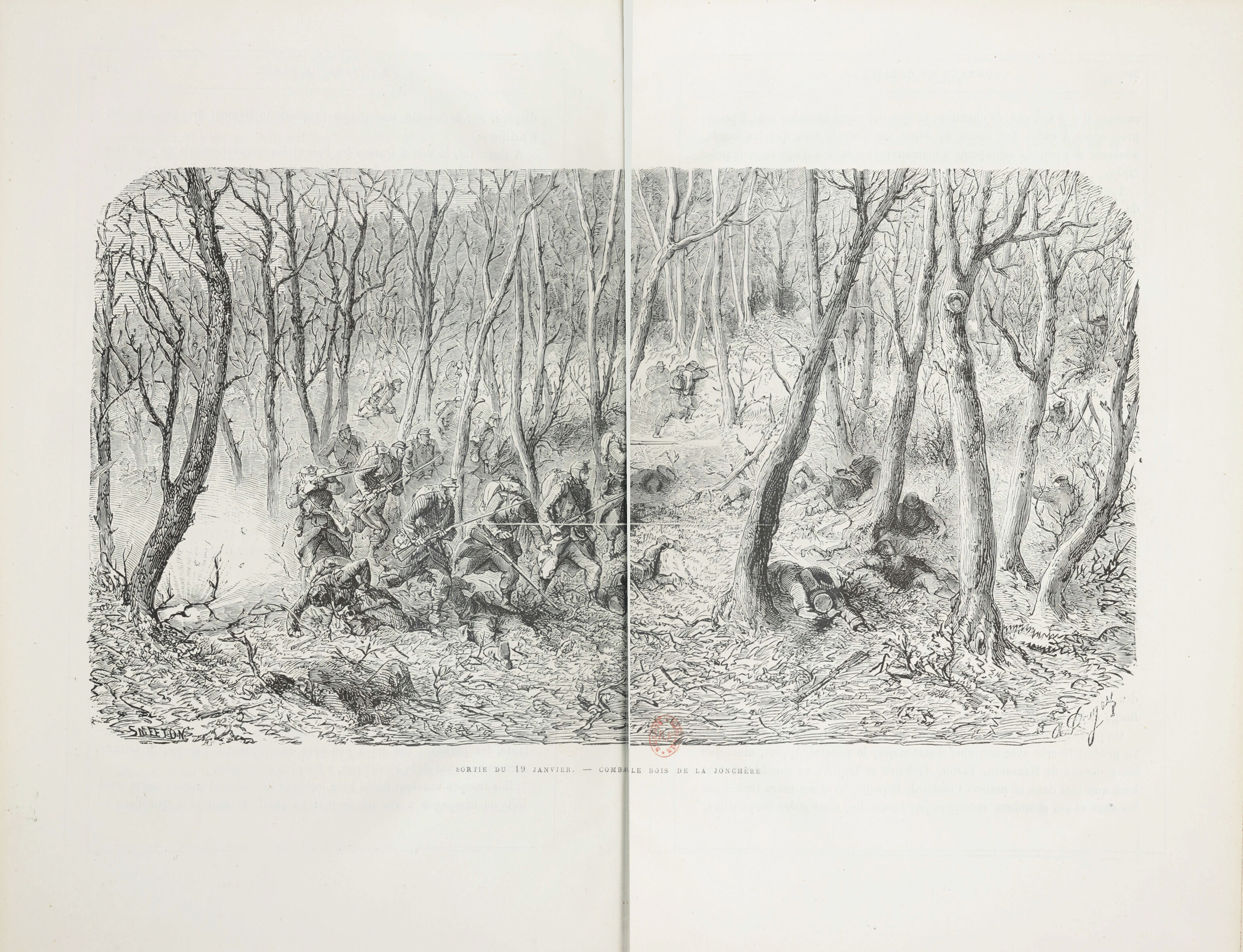

At first blush, Chestnut Grove at Louveciennes seems idyllic. The sun is shining; the air is still; and a woman and child rest beside the trunk of a large tree.11The woman and child reveal Pissarro’s debt to Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796–1875), who often included diminutive figures in his landscapes. Pissarro listed Corot as his teacher when he submitted work to the Salons of 1864 and 1866. See Joel Isaacson, “Constable, Duranty, Mallarmé, Impressionism, Plein Air, and Forgetting,” Art Bulletin 76, no. 3 (September 1994): 438. However, this appearance of Arcadia is deceiving. When Pissarro completed this painting in 1872, Louveciennes was still recovering from the disastrous Franco-Prussian WarFranco-Prussian War: The war of 1870–71 between France (under Napoleon III) and Prussia, in which Prussian troops advanced into France and decisively defeated the French at Sedan. The defeat marked the end of the French Second Empire. For Prussia, the proclamation of the new German Empire at Versailles was the climax of Bismarck’s ambitions to unite Germany.. From October 5, 1870, to March 6, 1871, an estimated three thousand to thirty-five hundred Prussian troops occupied Louveciennes, forcing many residents into exile and causing widespread destruction.12More than eighty percent of residents fled before the Prussians reached Louveciennes. Those who remained behind were forced to pay exorbitant taxes to the invaders on pain of death. Läy and Läy, Louveciennes, mon village, 267–71. Pissarro and his family experienced these upheavals firsthand. Following the French defeat at the Battle of Sedan on September 2, 1870, they fled west to the home of fellow painter Ludovic Piette (1826–77) in Mayenne. Later that autumn, they joined relatives in London, returning to Louveciennes only in late June 1871, after the war and the fall of the Paris CommuneParis Commune: An insurrectionary socialist government in Paris that lasted from March 18 to May 27, 1871..13The precise date of their arrival in London is unknown, but it occurred sometime after the death of Pissarro’s newborn daughter, Adèle-Emma, on November 5, 1870. See letter no. 12, Camille Pissarro to Louis Retrou, late March 1871, in Janine Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro ([Saint-Ouen-l’Aumône, France]: Éditions du Valhermeil, 2003), 1:69n3. During their absence, Prussian soldiers had installed themselves in their home, using the ground floor as a stable and the upper floors as barracks. After the Prussian withdrawal, Pissarro’s sister-in-law Félicie Estruc traveled on foot from Rueil-Malmaison to Louveciennes to assess the damage. What she found was devastating. “The road is impassable for vehicles, the houses are burned, [and] window panes, shutters, doors, staircases and floors are all gone,” she wrote to Pissarro. “As for your home it is uninhabitable.”14Félicie Estruc to Camille Pissarro, March 10, 1871, partially transcribed in Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 1:69n7. “La route est impraticable pour les voitures, les maisons sont brûlées, vitres, volets, portes, escaliers et parquets, tout cela a disparu. . . . Quant à votre maison elle est inhabitable.” Only a few pieces of Pissarro’s furniture were salvageable, and, worse still, hundreds of his paintings had been destroyed.

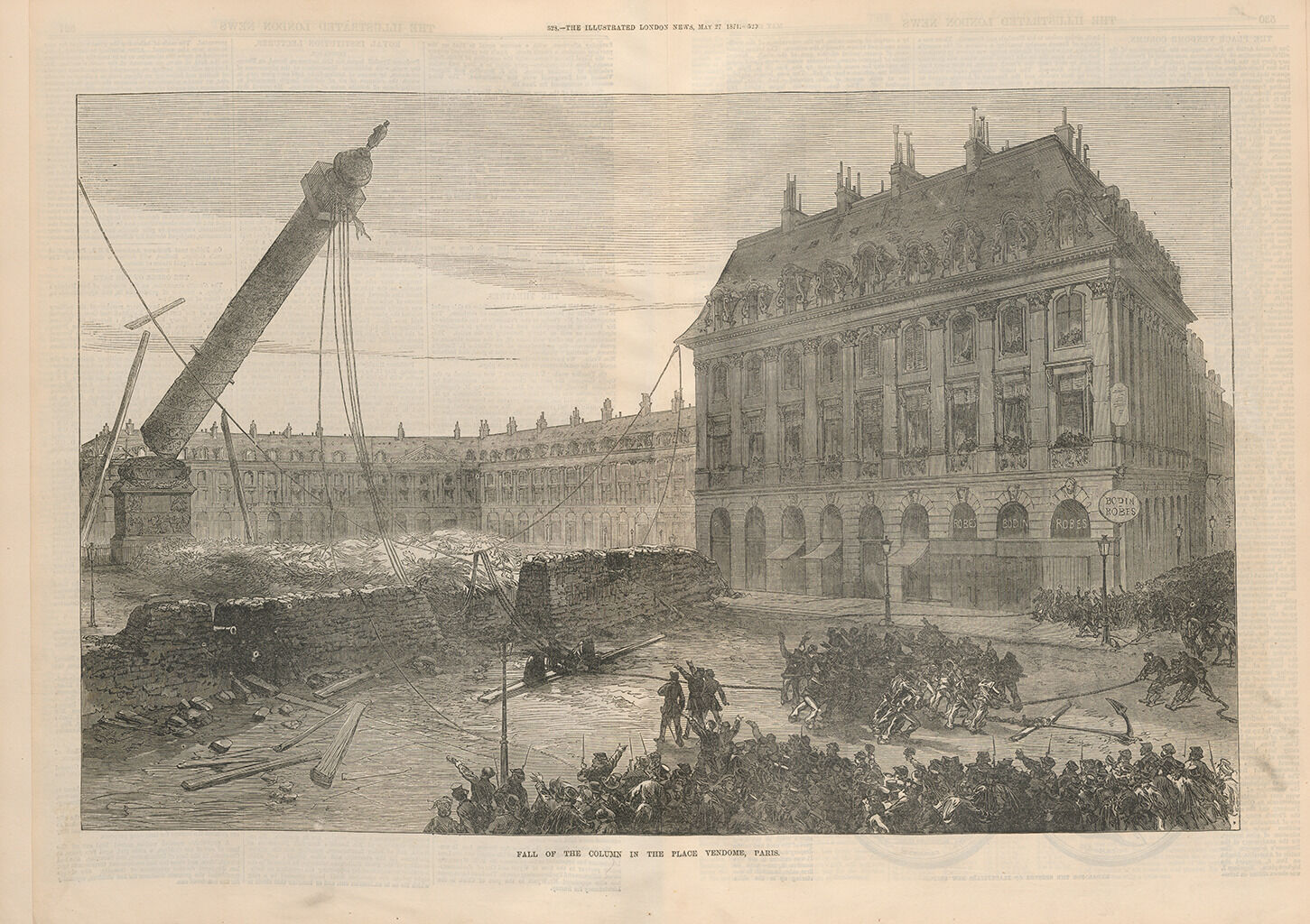

Another possible allusion to recent events is the conspicuously bent tree in the center foreground of Chestnut Grove at Louveciennes. Some scholars consider this tree—which is the defining formal element of the composition—a prime example of Pissarro’s “extreme attachment to the real” and evidence of his refusal to “alter the features presented by nature.”22See Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 52; and John Rewald, Camille Pissarro (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1963), 62. While it is certainly true that Pissarro could have discovered his motif in situ, the tree bears a noticeable resemblance to the Vendôme Column falling to the ground during the Paris Commune. Commissioned in the early 1800s by Napoleon I to commemorate the French victory at the Battle of Austerlitz, this obelisk was denounced by the CommunardsCommunards: A member or supporter of the Paris Commune of 1871. See “Paris Commune.” as an antiquated symbol of imperialism, and they ordered its demolition on May 16, 1871. A crowd watched as the perpetrators sawed through the base of the shaft, attached ropes to the summit, pulled on those cables using a capstan and sheer manpower, and prepared a bed of twigs, straw, and manure on the Rue de la Paix to cushion the column’s landing. At 5:35 p.m., the monument swayed and toppled to the earth as bands played La Marseillaise and spectators cried “Vive la Commune!”23La Marseillaise is the French national anthem. “La chute de la colonne Vendôme,” L’Illustration 57, no. 1474 (May 27, 1871): 299.

Pissarro’s motivations for including a disguised reference to the Vendôme Column in a painting of rural Louveciennes are complex. Several scholars have demonstrated that the artist’s politics were still evolving in the early 1870s.25See Ralph E. Shikes, “Pissarro’s Political Philosophy and His Art,” in Christopher Lloyd, ed., Studies on Camille Pissarro (London: Routledge, 1986), 35–54; Albert Boime, Art and the French Commune: Imagining Paris after War and Revolution (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997), 49; Michel Melot, “Camille Pissarro in 1880: An Anarchist Artist in Bourgeois Society,” in Mary Tompkins Lewis, ed., Critical Readings in Impressionism and Post-Impressionism: An Anthology (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), 205–25; and Richard R. Brettell, Pissarro’s People, exh. cat. (San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 2011), 57–67. Born into a bourgeois family in the Antilles, he married a working-class woman and identified with leftist causes early on but did not develop strong anarchist convictions until the 1880s, when he befriended social radicals Jean Grave and Émile Pouget and read newspapers like La Révolté and Le Père Peinard. Additionally, like many Frenchmen with anti-state views, Pissarro had to be circumspect about broadcasting his opinions so as to avoid arrest.26Brettell, Pissarro’s People, 63. Nevertheless, his support for the Commune can be gleaned from a handful of extant writings. In one letter, sent from London in 1871 to Piette, Pissarro refers to the VersaillaisVersaillais: Name given by the Communards to the French troops who, under the command of General Patrice de MacMahon, suppressed the Paris Commune of 1871. See “Paris Commune.” as “these assassins of the socialists”; in another, written in 1887 to his son Lucien, he criticizes the late Jean-François Millet (1814–75) for describing the Communards as “savages and vandals” in some published correspondence.27Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 1:67, 67n1. Perhaps most tellingly, Pissarro incorporated a caricature of Adolphe Thiers, the French statesman who violently suppressed the Commune, in his 1874 portrait of Paul Cezanne (1839–1906).28See Camille Pissarro, Portrait of Cezanne, 1874, oil on canvas, 28 3/4 x 23 1/2 in. (73 x 59.7 cm), National Gallery, London, on loan from the collection of Laurence Graff OBE, L672, https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/camille-pissarro-portrait-of-cezanne. These comments and actions suggest that the artist likely sympathized with the Communards’ demolition of the Vendôme Column. Perhaps he intended the bent tree in Chestnut Grove at Louveciennes as a subtle tribute to the fédérésfédérés: French term for the troops who fought in support of the Paris Commune of 1871. See Paris Commune. who lost their lives during the infamous semaine sanglantesemaine sanglante: The final week of the Paris Commune (May 21–28, 1871), during which the Versaillais (French troops) launched a major offensive to retake Paris and executed thousands of insurgents. See Paris Commune. (“bloody week”) that ended with the Commune’s defeat.

The Nelson-Atkins painting is among the last works that Pissarro completed before moving his family to Pontoise in July 1872. Ostensibly a tranquil country scene, it nevertheless records a turbulent moment in French history and in the artist’s own life.

Notes

-

For census data, see Claude Motte and Marie-Christine Vouloir, “Louveciennes,” Des villages de Cassini aux communes d’aujourd’hui, Laboratoire de démographie historique, Centre national de la recherche scientifique, École des hautes études en sciences sociales, accessed October 4, 2021, http://cassini.ehess.fr/fr/html/fiche.php?select_resultat=20173. Louveciennes had 912 inhabitants in 1866 and 1,191 inhabitants in 1872.

-

Inaugurated in 1837, the Gare Saint-Lazare soon became an important gateway to northwestern France. Its original line from Paris to Le Pecq was extended to Saint-Germain-en-Laye in 1847. See Robert L. Herbert, Impressionism: Art, Leisure, and Parisian Society (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988), 196. The Chatou station was also easily accessible from Louveciennes. See Jacques Laÿ and Monique Laÿ, Louveciennes, mon village (Paris: Imprimerie de l’Indre, 1989), 370–72.

-

Paris et ses environs: Guide méthodique et raisonné (Paris: Gustave Barba, 1855), 180. “Toujours délicieux.” All translations by Brigid M. Boyle.

-

For more on this landscape, see Sarah Lees, ed., Nineteenth-Century European Paintings at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute (Williamstown, MA: Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, 2012), 2:583–86.

-

I thank Bruno Bentz for this information. Bruno Bentz, École Lamartine, to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, October 1, 2021, NAMA curatorial files.

-

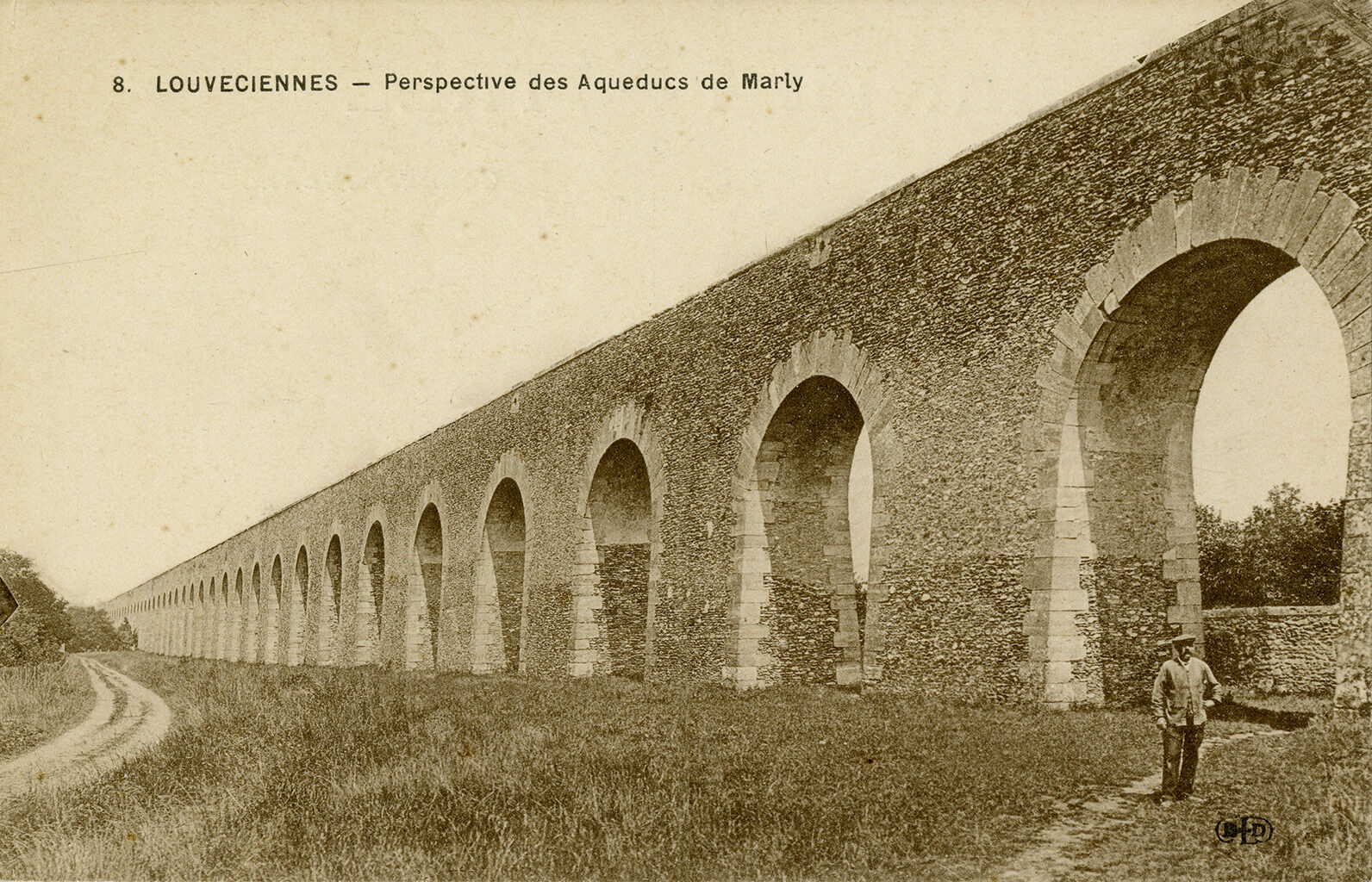

In 1681, Louis XIV commissioned Arnold de Ville and Rennequin Sualem to construct the so-called “Machine de Marly,” a hydraulics system capable of siphoning water 150 meters uphill from the Seine, hoping to solve his water supply problems at Versailles. The apparatus cost an estimated 3,500,000 livres, took three years to build, and required 221 pumps, fourteen massive waterwheels, and more than fifty workers to operate. Although the machine itself was retired from use in 1817, the aqueduct remained operational until 1866, just three years prior to Pissarro’s arrival. For further details, see Ian Thompson, The Sun King’s Garden: Louis XIV, Andre Le Nôtre, and the Creation of the Gardens of Versailles (New York: Bloomsbury, 2006), 247–51; and Jacques Laÿ and Monique Läy, Louveciennes: Histoire et rencontres (Paris: Éditions Riveneuve, 2016), 46–51.

-

See, for example, Joseph Mallord William Turner, Marly Aqueduct, ca. 1827–29, gouache, pen, ink, and pencil on paper, 5 1/2 x 7 1/2 in. (14 x 19 cm), Tate Britain, London, D24886. Other artists who have sketched or painted the aqueduct include Auguste Paul Charles Anastasi (1820–89), Isidore Laurent Deroy (1797–1886), August Alexandre Guillaumot (1815–92), Cécile Marchand (active 1808–33), Pierre-Denis Martin (ca. 1663–1742), Charles Nicolas Ransonnette (1793–1877), and Jean Louis Tirpenne (1801–after 1878). The best-known rendering of this conduit is Sisley’s The Aqueduct at Louveciennes, 1874, oil on canvas, 21 3/8 x 32 in. (54.3 x 81.3 cm), Toledo Museum of Art, 1951.371.

-

A door in the stone wall surrounding Pissarro’s backyard provided him with direct access to the aqueduct. See Läy and Läy, Louveciennes: Histoire et rencontres, 63.

-

I am grateful to Bruno Bentz for passing along Jacques Läy’s comments. Bruno Bentz, École Lamartine, to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, October 1, 2021, NAMA curatorial files.

-

I thank Benjamin Ringot for his help in pinpointing Pissarro’s location. Benjamin Ringot, Centre de recherche du château de Versailles, to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, September 28, 2021, NAMA curatorial files.

-

The woman and child reveal Pissarro’s debt to Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796–1875), who often included diminutive figures in his landscapes. Pissarro listed Corot as his teacher when he submitted work to the Salons of 1864 and 1866. See Joel Isaacson, “Constable, Duranty, Mallarmé, Impressionism, Plein Air, and Forgetting,” Art Bulletin 76, no. 3 (September 1994): 438.

-

More than eighty percent of residents fled before the Prussians reached Louveciennes. Those who remained behind were forced to pay exorbitant taxes to the invaders on pain of death. Läy and Läy, Louveciennes, mon village, 267–71.

-

The precise date of their arrival in London is unknown, but it occurred sometime after the death of Pissarro’s newborn daughter, Adèle-Emma, on November 5, 1870. See letter no. 12, Camille Pissarro to Louis Retrou, late March 1871, in Janine Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro ([Saint-Ouen-l’Aumône, France]: Éditions du Valhermeil, 2003), 1:69n3.

-

Félicie Estruc to Camille Pissarro, March 10, 1871, partially transcribed in Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 1:69n7. “La route est impraticable pour les voitures, les maisons sont brûlées, vitres, volets, portes, escaliers et parquets, tout cela a disparu. . . . Quant à votre maison elle est inhabitable.”

-

For these numbers, see “Rapport du Général Ducrot,” L’Illustration 56, no. 1444 (October 28, 1870): 311.

-

Robert Tombs, The War Against Paris, 1871 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981), 83. For a play-by-play of this battle, see Edmund Ollier, Cassell’s History of the War between France and Germany, 1870–1871 (London: Cassell, Petter, and Galpin, 1871), 1:410–13.

-

The following month, the aqueduct of Marly played another role in the war when Imperial Chancellor Otto von Bismarck himself climbed the aqueduct’s northern tower, known as the Tour du Levant, on November 30, 1870, to gauge some fighting in Nanterre. See Läy and Läy, Louveciennes: Histoire et rencontres, 49.

-

Pissarro’s brother-in-law Louis Estruc blamed his niece’s early demise on her wet nurse. The artist bemoaned the loss of “le travail de vingt ans de ma vie” in an undated letter to his landlord Louis Retrou, likely sent in late March 1871. See letter no. 12, Camille Pissarro to Louis Retrou, late March 1871, in Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 1:69, 69n3.

-

Letter no. 12, Camille Pissarro to Louis Retrou, late March 1871, in Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 1:68n1.

-

Le monde illustré reported on October 8, 1870, that: “À l’ouest, les Allemands occupent les hauteurs de Bougival, de Louveciennes, de Marly, et de Saint Germain. Partout ils se couvrent dans les bois” (To the west, the Germans occupy the heights of Bougival, Louveciennes, Marly, and Saint Germain. They take cover in the woods everywhere). See Maxime Vauvert, “Le Bulletin de la guerre,” Le monde illustré, no. 704 (October 8, 1870): 231.

-

Louis Jezierski was editor of the French daily L’Opinion nationale. His book is an anthology of this newspaper’s wartime coverage. See Louis Jezierski, Combats et batailles du siège de Paris, septembre 1870 à janvier 1871 (Paris: Garnier frères, 1872).

-

See Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 52; and John Rewald, Camille Pissarro (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1963), 62.

-

La Marseillaise is the French national anthem. “La chute de la colonne Vendôme,” L’Illustration 57, no. 1474 (May 27, 1871): 299.

-

The tree forms a rigid diagonal until its highest extremity, where a concave section of trunk surrounded by patches of bare canvas (as if to highlight this segment of tree) intersects the right margin of the canvas.

-

See Ralph E. Shikes, “Pissarro’s Political Philosophy and His Art,” in Christopher Lloyd, ed., Studies on Camille Pissarro (London: Routledge, 1986), 35–54; Albert Boime, Art and the French Commune: Imagining Paris after War and Revolution (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997), 49; Michel Melot, “Camille Pissarro in 1880: An Anarchist Artist in Bourgeois Society,” in Mary Tompkins Lewis, ed., Critical Readings in Impressionism and Post-Impressionism: An Anthology (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), 205–25; and Richard R. Brettell, Pissarro’s People, exh. cat. (San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 2011), 57–67.

-

Brettell, Pissarro’s People, 63.

-

Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 1:67, 67n1.

-

See Camille Pissarro, Portrait of Cezanne, 1874, oil on canvas, 28 3/4 x 23 1/2 in. (73 x 59.7 cm), National Gallery, London, on loan from the collection of Laurence Graff OBE, L672, https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/camille-pissarro-portrait-of-cezanne.

Technical Entry

Technical entry forthcoming.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Camille Pissarro, Chestnut Grove at Louveciennes, 1872,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.640.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Camille Pissarro, Chestnut Grove at Louveciennes, 1872,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.640.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Camille Pissarro, Chestnut Grove at Louveciennes, 1872,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.640.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Camille Pissarro, Chestnut Grove at Louveciennes, 1872,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.640.4033.

With Félix Gérard Fils, Paris [1];

Albert Bellanger, Paris [2];

With Paul Rosenberg, Paris, no. 3729, as Village derrière les arbres or Bois de Châtaigniers à Louveciennes, by February 1937 [3];

Purchased from Rosenberg by Arthur Tooth and Sons, Ltd., London, as Village derrière les arbres, by February 1937–November 9, 1937 [4];

Purchased from Arthur Tooth and Sons, stock ledger 7, no. 7672, as Village derrière les arbes, by Captain Albany “Barney” Kennett Charlesworth (1892–1945), Whitwell Hall, Yorkshire, England, November 9, 1937–45 [5];

Inherited by his wife Lady Marjorie Nell “Diana” Charlesworth (née Beckett-Denison, later Lady Cholmondeley, 1900–65), Whitwell Hall, Yorkshire, England, and Cholmondeley, South Kensington, England, by 1945–at least 1948 [6];

Purchased from Lady George Cholmondeley by Arthur Tooth and Sons, London, stock no. 2441, as Bois des Châtaigniers à Louveciennes, by July 26, 1950 [7];

Purchased from Arthur Tooth and Sons by Sam Salz Gallery, New York, July 26, 1950–March 3, 1952;

Purchased from Sam Salz Gallery by Mr. Alexander M. (1908–88) and Mrs. Elisabeth (née Roulleau, 1912–2012) Lewyt, New York, March 3, 1952–November 11, 1997;

Purchased at their sale, Impressionist and Modern Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture (Part 1), Christie’s, New York, November 11, 1997, lot 119, as Bois de chataigniers à Louveciennes, by Marion (née Helzberg, 1931–2013) and Henry (1922–2019) Bloch, Shawnee Mission, KS, 1997–June 15, 2015;

Their gift to the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 2015.

Notes

[1] Félix Gérard is cited in the painting’s provenance in Joachim Pissarro and Claire Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Critical Catalogue of Paintings (Paris: Wildenstein Institute Publications, 2005), no. 233, p. 2:191. Félix Laurent Joseph Gérard, the elder (1835–1904) had a framing shop in the 1870s and was listed as a marchand de tableaux on his death in 1904. By 1903, his son Félix Isidore Joseph Gérard (1864–1937) had taken over his father’s business, renaming the firm Félix Férard Fils. The younger Félix Gérard probably brokered the deal with Pissarro, as the artist often wrote about his dealings with the firm’s young dealer in his correspondence; see Pissarro and Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Critical Catalogue of Paintings, no. 233, p. 1:312.

[2] See The Paul Rosenberg Archives, a Gift of Elaine and Alexandre Rosenberg, III.D, Rosenberg Galleries: Miniature Photo and Card Index, ca. 1910–87, The Museum of Modern Art, New York. The photo card says, “Collection Bellanger/ S.D.” Ilda François, secretary to Elaine Rosenberg, suggested the S. D. might be an abbreviation for “Signé Droite” (see email from Ilda François to Meghan Gray, October 27, 2016, NAMA curatorial files). However, the artist’s signature is on the left in this painting. Albert Bellanger bought and sold several works from Rosenberg in the 1950s.

Albert Bellanger is possibly Albert-Joseph-Constance-Daniel Bellanger (1893–1970), who lived in Paris.

[3] According to Ilda François, Paul Rosenberg purchased the painting between January and February 1937. See also The Paul Rosenberg Archives, a Gift of Elaine and Alexandre Rosenberg, IV.A.I.a, Liste de Photographies, Paris, [1917–1939] [1940–present], The Museum of Modern Art, New York, and The Paul Rosenberg Archives, a Gift of Elaine and Alexandre Rosenberg, III.D, Rosenberg Galleries: Miniature Photo and Card Index, ca. 1910–1987, The Museum of Modern Art, New York. See also email from Emma Howgill, Tate Britain, to Francesca Whitlum-Cooper, contract researcher, NAMA, May 27, 2015, NAMA curatorial files; and Tate Britain, London, Arthur Tooth and Sons, London and New York, stock album, TGA 20106/2/3/50.

[4] See Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, Arthur Tooth and Sons Stock inventories and accounts, Series I, Box 18, Picture Sales no. 6, 1 June 1934–31 December 1937.

[5] See email from Emma Howgill, Tate Britain, to Francesca Whitlum-Cooper, contract researcher, NAMA, May 27, 2015, NAMA curatorial files. See also Tate Britain, London, Arthur Tooth and Sons, London and New York, stock ledger 7, TGA 20106/4/1.

[6] Albany “Barney” Kennett (1892–1945) married Marjorie Nell “Diana” Beckett-Denison (1900–65) on July 18, 1923. After her husband’s death, Diana remarried on December 21, 1948 to Lt.-Col. Lord George Hugo Cholmondeley (1887–1958), and she became Lady Cholmondeley. See Charles Mosley, ed., Burke’s Peerage and Baronetage, 107th ed. (Crans, Switzerland: Burke’s Peerage, 2003), 3:785.

[7] See email from from Emma Howgill, Tate Britain, to Fran Whitlum-Cooper, contract researcher, NAMA, May 27, 2015, NAMA curatorial files. See also Tate Britain, London, Arthur Tooth and Sons, London and New York, stock ledger 8, TGA 20106/4/2, and card index for P, TGA 20106/3/11.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Camille Pissarro, Chestnut Grove at Louveciennes, 1872,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.640.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Camille Pissarro, Chestnut Grove at Louveciennes, 1872,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.640.4033.

Camille Pissarro, Chestnut Trees at Louveciennes, Spring 1870, oil on canvas, 23 3/8 x 28 3/4 in. (59.5 x 73 cm), Museum Langmatt, Baden.

Camille Pissarro, Snow Landscape in Louveciennes, 1872, oil on canvas, 18 1/8 x 21 5/8 in. (46 x 55 cm), Museum Folkwang, Essen, Germany.

Camille Pissarro, Chestnut Trees in Louveciennes, 1879, oil on canvas, 16 1/8 x 21 1/4 in. (41 x 54 cm), Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Camille Pissarro, Chestnut Grove at Louveciennes, 1872,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.640.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Camille Pissarro, Chestnut Grove at Louveciennes, 1872,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.640.4033.

Possibly Pissarro, Galerie Durand-Ruel, Paris, 1902, no. cat.

Possibly Les chefs-d’œuvre de l’art français, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 1932, no. cat.

“La Flèche d’Or”: Important Pictures from French Collections; Third Exhibition, Arthur Tooth and Sons, London, November 11–December 4, 1937, no. 8, as Village Derrière Les Arbres.

C. Pissarro: Loan Exhibition For the benefit of Recording for the Blind, Wildenstein, New York, March 25–May 1, 1965, no. 9, as Châtaigniers à Louveciennes.

Four Masters of Impressionism: For the Benefit of The Lenox Hill Hospital New York, Acquavella Galleries, New York, October 24–November 30, 1968, no. 6, as Les Chataigniers à Louveciennes.

Pissarro: Camille Pissarro, 1830–1903, Hayward Gallery, London, October 30, 1980–January 11, 1981; Grand Palais, Paris, January 30–April 27, 1981; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, May 19–August 9, 1981, no. 18 (Boston only), as Chestnut trees at Louveciennes.

Camille Pissarro: Impressionist Innovator, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, October 11, 1994–January 9, 1995; The Jewish Museum, New York, February 26–July 16, 1995, no. 40 (Jerusalem only), as Groves of Chestnut Trees at Louveciennes.

Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, June 9–September 9, 2007, no. 7, as Chestnut Grove at Louveciennes (Bois de châtaigniers à Louveciennes).

The Impressionists and Photography, Museo Nacional Thyseen-Bornemisza, Madrid, October 15, 2019–January 26, 2020, no. 20, as Chestnut Grove at Louveciennes (Bois de châtaigniers à Louveciennes).

References

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Camille Pissarro, Chestnut Grove at Louveciennes, 1872,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.640.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Camille Pissarro, Chestnut Grove at Louveciennes, 1872,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.640.4033.

“La Flèche d’Or”: Important Pictures from French Collections; Third Exhibition, exh. cat. (London: Arthur Tooth and Sons, 1937), unpaginated, as Village derrière les arbres.

Ludovic Rodo Pissarro and Lionello Venturi, Camille Pissarro, Son art, Son Œuvre (Paris: Paul Rosenberg, 1939), no. 148, pp. 1:100; 2:unpaginated, (repro.), as Bois de chataigniers a Louveciennes.

John Rewald, Camille Pissarro (1830–1903) (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1954), unpaginated, (repro.), as Chestnut Trees at Louveciennes.

Meϊr Stein, Camille Pissarro, 1830–1903 (Copenhagen: Gyldendal, 1955), unpaginated, (repro.), as Kastanietræer I Louveciennes.

John Rewald, The History of Impressionism, rev. ed. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1961), 295, (repro.), as Chestnut Trees at Louveciennes.

Leopold Reidemeister, Auf den Spuren der Maler der Ile de France: Topographische Beiträge zur Geschichte der französischen Landschaftsmaleri von Corot bis zu den Fauves (Berlin: Propyläen Verlag, 1963), 49, (repro.), as Kastanienbäume in Louveciennes.

John Rewald, Camille Pissarro (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1963), 62, (repro.), as Chestnut Trees at Louveciennes.

C. Pissarro: Loan Exhibition For the benefit of Recording for the Blind, Inc., exh. cat. (New York: Wildenstein, 1965), unpaginated, (repro.), as Chataigniers à Louveciennes.

Four Masters of Impressionism: For the Benefit of The Lenox Hill Hospital New York, exh. cat. (New York: Acquavella Galleries, 1968), unpaginated, (repro.), as Les Châtaigniers A [sic] Louveciennes.

John Rewald, The History of Impressionism, 4th rev. ed. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1973), 295, (repro.), as Chestnut Trees at Louveciennes.

Marina Preutu, Pissarro (Bucharest: Editura Meridiane, 1974), 27, (repro.), as Pădure de Castani La Louveciennes.

John Rewald et al., Pissarro: Camille Pissarro, 1830–1903, exh. cat. (London: Arts Council of Great Britain, 1980), 85, (repro.), as Chestnut Trees at Louveciennes.

Christopher Lloyd, Camille Pissarro (Geneva: Skira, 1981), 52–53, 145, (repro.), as Chestnut Trees at Louveciennes.

Bruce Bernard, ed., The Impressionist Revolution (London: Orbis, 1986), 226, 262, (repro.), as Chestnut Trees at Louveciennes.

Jacques Laÿ and Monique Laÿ, Louveciennes, mon village (Paris: Imprimerie de l’Indre, 1989), 46, as Bois de Châtaigniers à Louveciennes.

Ludovico Rodo Pissarro and Lionello Venturi, Camille Pissarro, Son Art—Son Œuvre, 2nd rev. ed. (San Francisco: Alan Wofsy Fine Arts, 1989), no. 148, pp. 1:100; 2:unpaginated, (repro.), as Bois de chataigniers a [sic] Louveciennes.

Joachim Pissarro, Camille Pissarro (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1993), 66–67, 69–70, (repro.), as Groves of Chestnut Trees at Louveciennes.

Joel Isaacson, “Constable, Duranty, Mallarmé, Impressionism, Plein Air, and Forgetting,” Art Bulletin 76, no. 3 (1994): 437n50, 445n53.

Linda Doeser, The Life and Works of Pissarro (New York: Shooting Star Press, 1994), 24–25, (repro.), as Chestnut Trees at Louveciennes.

Joachim Pissarro and Stephanie Rachum, Camille Pissarro: Impressionist Innovator, exh. cat. (Jerusalem: Israel Museum, 1994), 95, 97, 112–13, (repro.), as Groves of Chestnut Trees.

Impressionist and Modern Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture (Part 1) (New York: Christie’s, November 11, 1997), 60–61, (repro.), as Bois de chataigniers à Louveciennes.

Eva-Maria Preiswerk-Lösel, ed., Ein Haus für die Impressionisten: das Museum Langmatt (Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2001), 110, (repro.), as Bois de châtaigniers à Louveciennes.

John Rewald et al., The History of Impressionism (Tokyo: Kadokawa Gakugei Shuppan, 2004), 218, 435, (repro.), as Chestnut Trees at Louveciennes.

Joachim Pissarro and Claire Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Critical Catalogue of Paintings (Paris: Wildenstein Institute Publications, 2005), no. 233, pp. 1:381, 396, 398, 400, 417; 2:191, (repro.), as Bois de châtaigniers à Louveciennes.

Rebecca Dimling and Bobbie Leigh, “100 Top Collectors Who Have Made a Difference,” Arts and Antiques (March 2006): 90.

Bobbie Leigh, “Magnificent Obsession,” Art and Antiques 29, no. 6 (June 2006): 62.

Alice Thorson, “A final countdown—A rare showing of Impressionist paintings from the private collection of Henry and Marion Bloch is one of the inaugural exhibitions at the 165,000-square-foot glass-and-steel structure,” Kansas City Star (June 29, 2006): B1.

“Inaugural Exhibitions Celebrate Kansas City,” Member Magazine (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (Fall 2006): 3.

Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 12–13, 52–55, 156, (repro.), as Chestnut Grove at Louveciennes (Bois de châtaigniers à Louveciennes).

Alice Thorson, “A Tiny Renoir Began an Impressive Obsession,” Kansas City Star 127, no. 269 (June 3, 2007): E4.

“Lasting Impressions: A Tribute to Marion and Henry Bloch,” Member Magazine (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (Fall 2007): 11–12.

Steve Paul, “Pretty Pictures: Marion and Henry Bloch’s Collection of Superb Impressionist Masters,” Panache 4, no. 3 (Fall 2007): 20.

Alice Thorson, “Museum to Get 29 Impressionist Works from the Bloch Collection,” Kansas City Star (February 5, 2010): A1.

Carol Vogel, “Inside Art: Kansas City Riches,” New York Times 159, no. 54,942 (February 5, 2010): C26.

Thomas M. Bloch, Many Happy Returns: The Story of Henry Bloch, America’s Tax Man (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, 2011), 175.

Diane Stafford, “Bloch Gift to Go for Nelson Upgrade,” Kansas City Star 135, no. 203 (April 8, 2015): A8.

“Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Officially Accessions Bloch Impressionist Masterpieces,” Artdaily.org (July 25, 2015): http://artdaily.com/news/80246/Nelson-Atkins-Museum-of-Art-officially-accessions-Bloch-Impressionist-masterpieces#.V6oGwlKFO9I.

Julie Paulais, “Le Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art reçoit des tableaux impressionnistes en échange de leurs répliques,” Le Journal des arts (July 30, 2015): http://www.lejournaldesarts.fr/site/archives/ docs_article/129801/le-nelson-atkins-museum-of-art-recoit-des-tableaux-impressionnistes-en-echange-de-leurs-repliques.php.

Josh Niland, “The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Acquires a Renowned Collection of Impressionist and Postimpressionist Art,” architecturaldigest.com (August 6, 2015): https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/nelson-atkins-museum-accessions-bloch-art-collection.

Nina Siegal, “Upon Closer Review, Credit Goes to Bosch,” New York Times 165, no. 57130 (February 2, 2016): C5.

“Nelson-Atkins to unveil renovated Bloch Galleries of European Art in winter 2017,” Artdaily.org (July 20, 2016): http://artdaily.com/news/88852/Nelson-Atkins-to-unveil-renovated-Bloch-Galleries-of-European-Art-in-winter-2017-#.W-NDepNKhaQ.

“Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art celebrates generosity of Henry Bloch with new acquisition,” Artdaily.org (October 18, 2016): http://artdaily.com/news/90923/Nelson-Atkins-Museum-of-Art-celebrates-generosity-of-Henry-Bloch-with-new-acquisition#.W-NDv5NKhaQ.

Catherine Futter et al., Bloch Galleries: Highlights from the Collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2016), 73, (repro.), as Chestnut Grove at Louveciennes.

Kelly Crow, “Museum Rewards Donor with Fake Art to Hang at Home,” Wall Street Journal (January 25, 2017): https://www.wsj.com/articles/museum-rewards-donor-with-fake-art-to-hang-at-home-1485370768.

David Frese, “Bloch savors paintings in redone galleries,” Kansas City Star (February 25, 2017): 1A.

Albert Hect, “Henry Bloch’s Masterpieces Collection to Go on Display at Nelson-Atkins Museum,” Jewish Business News (February 26, 2017): http://jewishbusinessnews.com/2017/02/26/henry-bloch-masterpieces-collection/.

David Frese, “Inside the Bloch Galleries: An interactive experience,” Kansas City Star 137, no. 169 (March 5, 2017): 1D, 4D.

“Editorial: Thank you, Henry and Marion Bloch,” Kansas City Star (March 7, 2017): http://www.kansascity.com/opinion/editorials/article137040948.html [repr., “Thank you, Henry and Marion Bloch,” Kansas City Star 137, no. 172 (March 8, 2017): 16A].

Hampton Stevens, “(Not Actually) 12 Things To Do During The Big 12 Tournament,” Flatland: KCPT’s Digital Magazine (March 9, 2017): http://www.flatlandkc.org/arts-culture/sports/not-actually-12-big-12-tournament/.

Laura Spencer, “The Nelson-Atkins’ Bloch Galleries feature Old Masterworks and New Technology,” KCUR (March 10, 2017): http://kcur.org/post/nelson-atkins-bloch-galleries-feature-old-masterworks-and-new-technology#stream/0.

Victoria Stapley-Brown, “Nelson-Atkins Museum’s new European art galleries come with a ‘love story’,” Art Newspaper (March 10, 2017): http://theartnewspaper.com/news/museums/nelson-atkins-museum-s-new-european-art-galleries-come-with-a-love-story/.

Harry Bellet, “Don du ciel pour le Musée Nelson-Atkins,” Le Monde (March 13, 2017): http://www.lemonde.fr/arts/article/2017/03/13/don-du-ciel-pour-le-musee-nelson-atkins_5093543_1655012.html.

Menachem Wecker, “Jewish Philanthropist Establishes Kansas City as Cultural Mecca,” Forward (March 14, 2017): http://forward.com/culture/365264/jewish-philanthropist-establishes-kansas-city-as-cultural-mecca/ [repr., in Menachem Wecker, “Kansas City Collection Is A Chip Off the Old Bloch,” Forward (March 17, 2017): 20-22].

Juliet Helmke, “The Bloch Collection Takes up Residence in Kansas City’s Nelson Atkins Museum,” BoulinArtInfo International (March 15, 2017): http://www.blouinartinfo.com/news/story/ 2005267/the-bloch-collection-takes-up-residence-in-kansas-citys?utm_source=Blouin+Artinfo+Newsletters&utm_ campaign=a2555adf27-Daily+Digest+03.16.2017+-+8+AM &utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_df23dbd3c6-a2555adf27-83695841.

Erich Hatala Matthes, “Digital replicas are not soulless—they help us engage with art,” Apollo (March 23, 2017): https://www.apollo-magazine.com/digital-replicas-3d-printing-original-artworks/.

Louise Nicholson, “How Kansas City got its magnificent museum,” Apollo (April 7, 2017): https://www.apollo-magazine.com/how-kansas-city-got-its-magnificent-museum/.

Lilly Wei, “Julián Zugazagoitia: ‘Museums should generate interest and open a door that leads to further learning’,” Studio International (August 21, 2017): http://studiointernational.com/index.php/julian-zugazagoitia-director-nelson-atkins-museum-of-art-kansas-city-interview.

Robert D. Hershey Jr., “Henry Bloch, H&R Block’s cofounder, dies at 96,” Boston Globe (April 23, 2019): https://www3.bostonglobe.com/metro/ obituaries/2019/04/23/henry-bloch-block-cofounder/?arc404=true.

Robert D. Hershey Jr., “Henry W. Bloch, Tax-Preparation Pioneer (and Pitchman), Is Dead at 96,” New York Times (April 23, 2019): https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/23/ obituaries/henry-w-bloch-dead.html.

Claire Selvin, “Henry Wollman Bloch, Collector and Prominent Benefactor of Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Is Dead at 96,” ArtNews (April 23, 2019): http://www.artnews.com/2019/04/23/henry-bloch-dead-96/.

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “Henry Bloch, co-founder of H&R Block, dies at 96,” Kansas City Star 139, no. 219 (April 24, 2019): 1A.

“Henry Wollman Bloch (1922–2019),” Art Forum (April 24, 2019): https://www.artforum.com/news/henry-wollman-bloch-1922-2019-79547.

Frank Morris, “Henry Bloch, Co-Founder Of H&R Block, Dies At 96,” npr.org (April 24, 2019): https://www.npr.org/2019/04/24/716641448/henry-bloch-co-founder-of-h-r-block-dies-at-96.

Ignacio Villarreal, “Nelson-Atkins mourns loss of Henry Bloch,” ArtDaily.org (April 24, 2019): http://artdaily.com/news/113035/Nelson-Atkins-mourns-loss-of-Henry-Bloch#.XMB76qR7laQ.

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “H&R Bloch co-founder, philanthropist Bloch dies,” Cass County Democrat Missourian 140, no. 29 (April 26, 2019): 1A

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “KC businessman and philanthropist Henry Bloch dies,” Lee’s Summit Journal 132, no. 79 (April 26, 2019): 3A, (repro.).

Luke Nozicka, “Family and friends remember Henry Bloch of H&R Block,” Kansas City Star 139, no. 225 (April 30, 2019): 4A [repr., Luke Nozicka, “Family and friends remember Henry Bloch of H&R Block,” Kansas City Star 139, no. 228 (May 3, 2019): 3A].

Paloma Alarcó, The Impressionists and Photography, exh. cat. (Madrid: Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, 2019), 58, (repro.), as Chestnut Grove at Louveciennes (Bois de châtaigniers à Louveciennes).

Eric Adler, “Sold for $3.25 million, Bloch’s home in Mission Hills may be torn down,” Kansas City Star 141, no. 90 (December 16, 2020): 2A.