Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “Camille Pissarro, Waterworks of the Marly Machine at Bougival, 1871,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.638.5407.

MLA:

Marcereau DeGalan, Aimee. “Camille Pissarro, Waterworks of the Marly Machine at Bougival, 1871,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.638.5407.

In December 1870, with the help of a loan from friends of his neighbor Ludovic Piette, Camille Pissarro and his family sailed from the French port city Saint-Malo to England to escape the dangers of the Prussian invasion in ParisFranco-Prussian War: The war of 1870–71 between France (under Napoleon III) and Prussia, in which Prussian troops advanced into France and decisively defeated the French at Sedan. The defeat marked the end of the French Second Empire. For Prussia, the proclamation of the new German Empire at Versailles was the climax of Bismarck’s ambitions to unite Germany..1Ralph E. Shikes and Paula Harper, Pissarro, His Life and Work (New York: Horizon, 1980), 88. Although the time Pissarro spent in England was financially challenging, it proved to be a fertile period for the growth of ideas and the expansion of his subject matter.2In a letter to his friend Théodore Duret in June 1871, Pissarro wrote, “En fait d’affaires, de vente, je n’ai rien fait, excepté Durand-Ruel qui m’a acheté deux petits tableaux. Ma peinture ne mord pas, mais pas du tout, cela me poursuit un peu partout” (In terms of business, sales, I did nothing, except Durand-Ruel who bought from me two small paintings. My painting does not bite, no, not at all; it pursues me everywhere); Janine Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro (Saint-Ouen-l’Aumône, France: Éditions du Valhermeil, 2003), 1:64n9. All translations are by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan unless otherwise noted. While there, he took advantage of the opportunity to study English painting by artists such as John Constable (1776–1837) and Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851), whose techniques for depicting the mechanization of water through locks, mills, weirsweir: A dam constructed on a canal or navigable river to retain the water and regulate its flow., and dams proved influential. These works, along with the industrial landscapes surrounding London, introduced Pissarro to new subject matter, inspiring his newfound interest in the expansion of France’s industrial suburbs through its waterways. Waterworks of the Marly Machine at Bougival was painted shortly after Pissarro’s return to France in 1871.

Water enacts a continual process of transformation and fluidity in the landscape, and its representation in painting showcases the artist’s deep understanding of how broader historical and geographical factors play a crucial role in shaping a specific location.3Stephen Daniels expresses this idea in his article “Liquid Landscape: Southam, Constable, and the Art of the Pond,” British Art Studies 10 (November 29, 2018): https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-10/sdaniels. The inclusion of rivers and waterways as an aspect of modernity in art—as opposed to the subject of the industrial landscape—has only more recently become the focus of academic study.4These topics find new form through an ecocritical lens in more recent scholarship, including a thoughtful work by Genevieve Westerby, “Pissarro at Pontoise: Picturing Infrastructure and the Changing Riverine Environment,” Athanor 39 (2022): 155–70. See also Maura Coughlin, “Biotopes and Ecotones: Slippery Images on the Edge of the French Atlantic,” Landscapes: The Journal of the International Centre for Landscape and Language 7, no. 1 (2016): 1–23; and John Ribner, “The Poetics of Pollution,” in Turner, Whistler, Monet: Impressionist Visions, ed. Katharine Lochnan (Toronto: Art Gallery of Ontario, 2004), 51–63. Throughout the nineteenth century, France underwent a range of infrastructure projects aimed at transforming its river systems to meet the demands of an industrializing economy. Starting in 1838, the Seine River, in particular, underwent significant transformations as riverbeds were dredged, locks and dams were constructed to address its inconsistent depth and tendency to flood, and new canals were established to connect major river systems for the efficient transportation of goods.5Sir Edward Thorpe, The Seine: From Havre to Paris (London: Macmillan, 1913), 19–23. Improvements such as these in the fluvial section of the river completely revolutionized the system of tractiontraction: A method of transportation for large stones or boulders in a river. The water rolls the stones along the river bottom since they are too heavy to be suspended in the water. and towage by horses, which was practically abandoned in France by the mid-nineteenth century, with steamers and small motorized boats using internal mechanization to self-propel up the river.6Thorpe, Seine, 24. These aspects of modern life would become a defining characteristic of Impressionist paintings in the 1870s, and the Waterworks of the Marly Machine at Bougival marks one of Pissarro’s first attempts at incorporating this theme into his own practice.7Richard Thomson is among the first scholars to acknowledge this point. See his Camille Pissarro: Impressionism Landscape and Rural Labour, exh. cat. (London: South Bank Centre, 1990), 19. Pissarro painted The Weir at Pontoise (ca. 1868; private collection) with a number of barges on the opposite shore. He repeated the motif with subtle changes around 1872, after his return from London: Camille Pissarro, The Lock at Pontoise, 1872, Cleveland Museum of Art, https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1990.7 In fact, it was one of at least twenty compositions featuring working aspects of the river that the artist realized in the two years after his trip to London, compared to only three that he had created before he left.8Paintings created before the artist’s trip to London: The Weir at Pontoise (1868; private collection, CR 129); The Marly Hydraulic Works at Bougival (1869; current location unknown, CR 132); The Seine at Bougival (1870; Bridgestone Museum of Art, Ishibashi Foundation, CR 154). Paintings created in the two years after his trip to London: The Seine at Bougival (1871; private collection, Switzerland, CR 200); Banks of the Seine at Bougival (1871; stolen in the Netherlands, 1993, CR 201); Barges on the Seine at Bougival (1871; private collection, CR 202); Banks of the River (1871; private collection, CR 204); The Seine at Port-Marly, The Wash-House (1872; Musée d’Orsay, Paris, CR 229); Banks of the Seine at Bougival (1872; Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, CR 234); The Seine at Port-Marly (1872; private collection, UK, CR 236); The Weir at Pontoise (1872; Cleveland Museum of Art, CR 243); The Weir and the Lock at Saint-Quen-l’Aumône (1872; private collection, CR 244); Banks of the Oise at Pontoise (1872; private collection, Chicago, CR 249); View of Pontoise, the Timber Raft (1872; private collection, CR 250); Banks of the Oise, Pontoise (1872; private collection, CR 251); Banks of the Oise near Pontoise (1872; private collection, CR 274); Road on the Banks of the Oise, Pontoise (1872; private collection, CR 275); Factory at St Quen-l’Aumône, the Flood of the Oise (1873; private collection, CR 297); Factory at Saint-Quen-l’Aumône (1873; Springfield [MA] Museum of Fine Arts, CR 298); Factory on the Banks of the Oise, Saint-Quen-l’Aumône (1873; The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, CR 299); Factory on the Banks of the Oise, Saint-Quen-l’Aumône (1873; Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, MA, CR 300); The Factory on the Banks of the Oise, Épluches (1873; private collection, CR 302); Route d’Auvers on the Banks of the Oise, Pontoise (1873; Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, CR 303).

The Nelson-Atkins painting depicts a stretch of the lower Seine in Bougival, a town located in the Yvelines department of the Île-de-France region in north-central France, about seventeen miles west of the center of Paris. Villages west of Paris, including Bougival, saw rapid and steady change at this time with the extension of the rail line, putting them within easy reach from the Gare Saint-Lazare (Saint-Lazare train station). Although Bougival was still somewhat rural, its proximity attracted bourgeois day-trippers who boated, promenaded, and dined there. Swimming was also popular at the local swimming hole, La Grenouillère, immortalized in paint by Pissarro’s contemporaries Claude Monet (1840–1926) and Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919), who set up their easels there in the summer of 1869.9See, for example, Claude Monet, La Grenouillère, 1869, Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/437135 In the Nelson-Atkins composition, however, Pissarro looks at the river through the lens of work rather than leisure. He includes a glimpse of the locks of Bougival at the right, in the midground; they were the first to be implemented as part of the canalization project for the Seine in 1838.10Thorpe, Seine, 20. These altered the flow of water into two channels around the Île de la Loge (Island of la Loge), seen on the opposite bank of Pissarro’s painting with the red-roofed house, and the Île Gautier, at the far right, home to the white mansard-roofed house.11Mont Valérien, occupied by the Prussian Army Corps during the Franco-Prussian War just months before Pissarro’s return, is visible in the distance beyond the houses of Croissy. Joachim Pissarro and Claire Durand-Ruel Snollaerts identified this and several other architectural and geographical features in the canvas in their 2005 catalogue raisonné. See Pissarro and Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Critical Catalogue of Paintings (Paris: Wildenstein Institute Publications, 2005), no. 203, p. 2:173. To access these islands, one needed to traverse the Seine via a small boat, like several of those featured in Pissarro’s composition, two of which are being maneuvered by standing figures wielding a single oar. Most of the boats are working types, including a canoe moored to the black landing at left; a green NorwegianNorwegian: A solid boat for walking and angling. It is a canoe with a very elegant rounded lift often seen in other Impressionist paintings. at center left, which may have been used for fishing; a double bachotbachot: A small flat-bottomwed boat used to cross rivers and reconizable for its lifting front, which facilitates standing on the bank. to its right, which was used as a work boat for the French public works department, which managed the dam; and a single bachot at far right, which may have been used to ferry inhabitants of the islands across the Seine, which was not possible upstream of the dam.12I am extremely grateful for the assistance of Frederic Delaive, associate researcher at the Tempora Laboratory, Rennes 2 University, and president of the Carré des canotiers. Delaive to Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, NAMA, February 22, and 25–26, 2023, NAMA curatorial files. The sketchy nature of the figures in these boats makes it difficult to determine their costume; however, Jean-Louis Lenhof, professor at Université de Caen-Normandiem, feels that at least those in the green boat appear in the bourgeois attire of shirtsleeves and waistcoats, rather than the overalls or plain shirts worn by manual workers. I am thankful for clarifying exchanges with him. Lenhof to Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, NAMA, February 14, 2023, NAMA curatorial files. In the foreground, Pissarro includes a prominent wooden rake-like structure which transects the river and the canvas from left to right. Known as a boom or estacade, it formed an extension of the “Marly Machine,” a remarkable hydraulic pumping system used to provide water uphill to the palace and gardens of Versailles during the late seventeenth century.13For information on the Marly Machine and the king’s garden, see Ian Thompson, The Sun King’s Garden: Louis XIV, André Le Nôtre and the Creation of the Gardens of Versailles (London: Bloomsbury, 2006), 251.

Fig. 2. Joseph Mallord William Turner, Marly-sur-Seine, ca. 1831, watercolor touched with bodycolor, 11 3/4 x 16 3/4 in. (28.6 x 42.6 cm), British Museum, London, 1958,0712.433. © The Trustees of the British Museum. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Fig. 2. Joseph Mallord William Turner, Marly-sur-Seine, ca. 1831, watercolor touched with bodycolor, 11 3/4 x 16 3/4 in. (28.6 x 42.6 cm), British Museum, London, 1958,0712.433. © The Trustees of the British Museum. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Fig. 3. Camille Pissarro, The Seine near Port Marly, 1872, oil on canvas, 18 1/8 x 22 in. (46 x 55.8 cm), Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, 2727. Photo: © Staatsgalerie Stuttgart

Fig. 3. Camille Pissarro, The Seine near Port Marly, 1872, oil on canvas, 18 1/8 x 22 in. (46 x 55.8 cm), Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, 2727. Photo: © Staatsgalerie Stuttgart

Fig. 4. Alfred Sisley, The Machine at Marly, 1873, oil on canvas, 17 3/4 x 25 3/8 in. (45 x 64.5 cm), Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen, SMK 3272

Fig. 4. Alfred Sisley, The Machine at Marly, 1873, oil on canvas, 17 3/4 x 25 3/8 in. (45 x 64.5 cm), Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen, SMK 3272

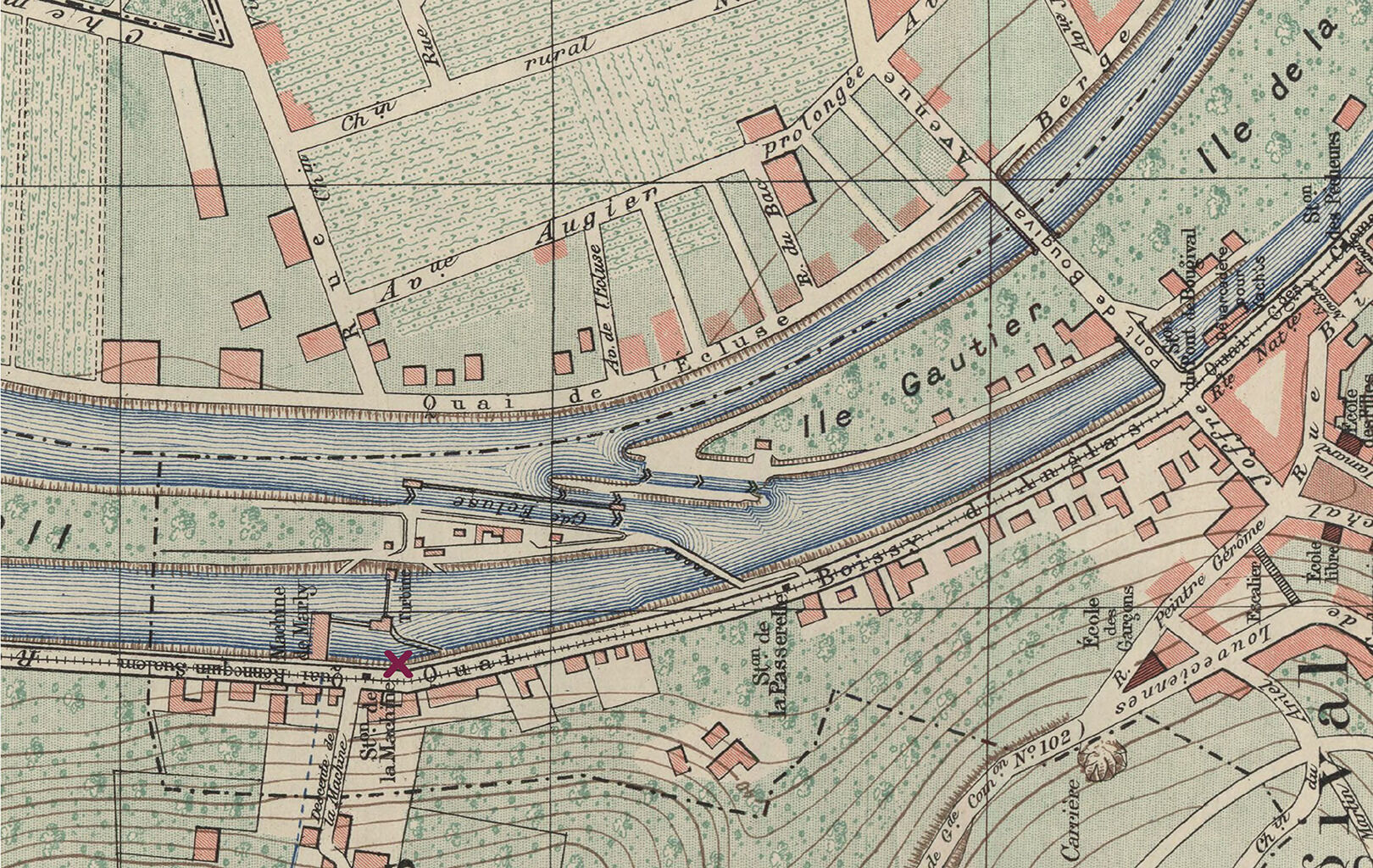

Fig. 5. Édouard Blondel de Rougery (designer and engraver, 1877–before 1955), Map of la Vésinet, Chatou, Croissy-s, le Pecq, Port-Marly and the surrounding area (detail), published 1924, sheet: 29 1/2 x 24 13/16 in. (75 x 63 cm), Bibliothèque National de France, Paris. The red X marks where Pissarro may have painted the Nelson-Atkins canvas.

Fig. 5. Édouard Blondel de Rougery (designer and engraver, 1877–before 1955), Map of la Vésinet, Chatou, Croissy-s, le Pecq, Port-Marly and the surrounding area (detail), published 1924, sheet: 29 1/2 x 24 13/16 in. (75 x 63 cm), Bibliothèque National de France, Paris. The red X marks where Pissarro may have painted the Nelson-Atkins canvas.

Notes

-

Ralph E. Shikes and Paula Harper, Pissarro, His Life and Work (New York: Horizon, 1980), 88.

-

In a letter to his friend Théodore Duret in June 1871, Pissarro wrote, “En fait d’affaires, de vente, je n’ai rien fait, excepté Durand-Ruel qui m’a acheté deux petits tableaux. Ma peinture ne mord pas, mais pas du tout, cela me poursuit un peu partout” (In terms of business, sales, I did nothing, except Durand-Ruel who bought from me two small paintings. My painting does not bite, no, not at all; it pursues me everywhere); Janine Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro (Saint-Ouen-l’Aumône, France: Éditions du Valhermeil, 2003), 1:64n9. All translations are by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan unless otherwise noted.

-

Stephen Daniels expresses this idea in his article “Liquid Landscape: Southam, Constable, and the Art of the Pond,” British Art Studies 10 (November 29, 2018): https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-10/sdaniels.

-

These topics find new form through an ecocritical lens in more recent scholarship, including a thoughtful work by Genevieve Westerby, “Pissarro at Pontoise: Picturing Infrastructure and the Changing Riverine Environment,” Athanor 39 (2022): 155–70. See also Maura Coughlin, “Biotopes and Ecotones: Slippery Images on the Edge of the French Atlantic,” Landscapes: The Journal of the International Centre for Landscape and Language 7, no. 1 (2016): 1–23; and John Ribner, “The Poetics of Pollution,” in Turner, Whistler, Monet: Impressionist Visions, ed. Katharine Lochnan (Toronto: Art Gallery of Ontario, 2004), 51–63.

-

Sir Edward Thorpe, The Seine: From Havre to Paris (London: Macmillan, 1913), 19–23.

-

Thorpe, Seine, 24.

-

Richard Thomson is among the first scholars to acknowledge this point. See his Camille Pissarro: Impressionism Landscape and Rural Labour, exh. cat. (London: South Bank Centre, 1990), 19. Pissarro painted The Weir at Pontoise (ca. 1868; private collection) with a number of barges on the opposite shore. He repeated the motif with subtle changes around 1872, after his return from London: Camille Pissarro, The Lock at Pontoise, 1872, Cleveland Museum of Art, https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1990.7.

-

Paintings created before the artist’s trip to London: The Weir at Pontoise (1868; private collection, CR 129); The Marly Hydraulic Works at Bougival (1869; current location unknown, CR 132); The Seine at Bougival (1870; Bridgestone Museum of Art, Ishibashi Foundation, CR 154). Paintings created in the two years after his trip to London: The Seine at Bougival (1871; private collection, Switzerland, CR 200); Banks of the Seine at Bougival (1871; stolen in the Netherlands, 1993, CR 201); Barges on the Seine at Bougival (1871; private collection, CR 202); Banks of the River (1871; private collection, CR 204); The Seine at Port-Marly, The Wash-House (1872; Musée d’Orsay, Paris, CR 229); Banks of the Seine at Bougival (1872; Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, CR 234); The Seine at Port-Marly (1872; private collection, UK, CR 236); The Weir at Pontoise (1872; Cleveland Museum of Art, CR 243); The Weir and the Lock at Saint-Quen-l’Aumône (1872; private collection, CR 244); Banks of the Oise at Pontoise (1872; private collection, Chicago, CR 249); View of Pontoise, the Timber Raft (1872; private collection, CR 250); Banks of the Oise, Pontoise (1872; private collection, CR 251); Banks of the Oise near Pontoise (1872; private collection, CR 274); Road on the Banks of the Oise, Pontoise (1872; private collection, CR 275); Factory at St Quen-l’Aumône, the Flood of the Oise (1873; private collection, CR 297); Factory at Saint-Quen-l’Aumône (1873; Springfield [MA] Museum of Fine Arts, CR 298); Factory on the Banks of the Oise, Saint-Quen-l’Aumône (1873; The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, CR 299); Factory on the Banks of the Oise, Saint-Quen-l’Aumône (1873; Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, MA, CR 300); The Factory on the Banks of the Oise, Épluches (1873; private collection, CR 302); Route d’Auvers on the Banks of the Oise, Pontoise (1873; Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, CR 303).

-

See, for example, Claude Monet, La Grenouillère, 1869, Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/437135.

-

Thorpe, Seine, 20.

-

Mont Valérien, occupied by the Prussian Army Corps during the Franco-Prussian War just months before Pissarro’s return, is visible in the distance beyond the houses of Croissy. Joachim Pissarro and Claire Durand-Ruel Snollaerts identified this and several other architectural and geographical features in the canvas in their 2005 catalogue raisonné. See Pissarro and Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Critical Catalogue of Paintings (Paris: Wildenstein Institute Publications, 2005), no. 203, p. 2:173.

-

I am extremely grateful for the assistance of Frederic Delaive, associate researcher at the Tempora Laboratory, Rennes 2 University, and president of the Carré des canotiers. Delaive to Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, NAMA, February 22, and 25–26, 2023, NAMA curatorial files. The sketchy nature of the figures in these boats makes it difficult to determine their costume; however, Jean-Louis Lenhof, professor at Université de Caen-Normandiem, feels that at least those in the green boat appear in the bourgeois attire of shirtsleeves and waistcoats, rather than the overalls or plain shirts worn by manual workers. I am thankful for clarifying exchanges with him. Lenhof to Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, NAMA, February 14, 2023, NAMA curatorial files.

-

For information on the Marly Machine and the king’s garden, see Ian Thompson, The Sun King’s Garden: Louis XIV, André Le Nôtre and the Creation of the Gardens of Versailles (London: Bloomsbury, 2006), 251.

-

General information on the Marly Machine has been extracted from Bruno Bentz and Éric Soullard, “La Machine de Marly,” Château de Versailles: De l’Ancien régime à nos jours, no. 1 (April/June 2011): 73–77. For more specifics on the early history of the machine, as well as excellent diagrams, see L. A. Barbet, Les grandes eaux de Versailles: Installations mécaniques et étangs artificiels, description des fontaines et de leurs origins (Paris: H. Dunod et E. Pinat, 1907), 95–126.

-

For further details, see Thompson, The Sun King’s Garden, 247–51; and Jacques Laÿ and Monique Läy, Louveciennes: Histoire et rencontres (Paris: Éditions Riveneuve, 2016), 46–51.

-

This was eventually replaced by electromechanical pumps in 1968, which continued to draw water from the river.

-

Pissarro and Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Critical Catalogue of Paintings, no. 132, p. 2:124.

-

I am grateful to Benjamin Ringot, Centre de recherche du château de Versailles, and Jacque Läy, independent historian, and his son Xavier Läy for their help and supplemental images, maps, and photographs in an effort to pinpoint Pissarro’s location. See Ringot and Läy to Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, NAMA, February 13–15, 2023, NAMA curatorial files.

-

See the respective provenance and bibliography sections for this painting completed by Danielle Hampton Cullen. When the painting appeared in the sale of George Feydou in 1903, it was listed as a scene of Pontoise; however, when it was sold in 1933 from Galerie Étienne Bignou to Kunsthandel Paul Cassirer in Amsterdam, it was called The Port of Marly. In 1959, when it was exhibited at Wildenstein Gallery in New York, it appeared as The Banks of the Seine at Bougival. It was also Bougival in both Pissarro catalogues raisonnés (1939 and 2005). See Ludovic Rodo Pissarro and Lionello Venturi, Camille Pissarro, Son Art—Son Œuvre (Paris: Paul Rosenberg, 1939), no. 125, pp. 1:97, 2: unpaginated, reproduced as Barrage sur la Seine a [sic] Bougival; and Pissarro and Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Critical Catalogue of Paintings, no. 203, p. 2:173. However, in 2007, Richard Brettell noted two verso inscriptions on the painting’s paper backing that read “Au bord de la Seine à Port Marly” (Banks of the Seine at Port Marly), which he argued was “probably more accurate than its traditional title, Weir on the Seine at Bougival.” See Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 51.

-

See forthcoming accompanying technical study by Nelson-Atkins assistant paintings conservator Diana Jaskierny.

-

Wynford Dewhurst, Impressionist Painting: Its Genesis and Development (London: G. Newnes, 1904), 31–32.

-

Malcolm Warner and Julia Marciari Alexander, This Other Eden: Paintings from the Yale Center for British Art (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998), 138.

-

Although not formally accessioned into the Victoria and Albert Museum’s collection until 1900, the full-scale study for Constable’s The Leaping Horse, ca. 1825, was on view there since 1862.

-

Jonathan Clarkson, Constable (London: Phaidon, 2010), 211.

Technical Entry

Technical entry forthcoming.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Camille Pissarro, Waterworks of the Marly Machine at Bougival, 1871,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.638.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Camille Pissarro, Waterworks of the Marly Machine at Bougival, 1871,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.638.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Camille Pissarro, Waterworks of the Marly Machine at Bougival, 1871,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.638.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Camille Pissarro, Waterworks of the Marly Machine at Bougival, 1871,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.638.4033.

Purchased at his sale, Catalogue des Tableaux Modernes, Aquarelles, Pastels, Dessins appartenant à M. Georges Feydeau, Hôtel Drouot, Paris, April 4, 1903, lot 39, as Barrage de la Seine à Pontoise, by M. Gobe[t]ski, April 4, 1903 [1];

With Raphaël Gérard, Paris [2];

With Galerie Étienne Bignou, Paris, by October 18, 1933;

Purchased from Bignou by Kunsthandel Paul Cassirer, Amsterdam, as Port de Marly, October 18, 1933–July 1934 [3];

Purchased from Kunsthandel Paul Cassirer by Robert “Rudi” Maas (1878–1940), Amsterdam, July 1934–40 [4];

Inherited by his wife, Elisabeth “Lili” Maas (née Jonas, 1885–1954), Amsterdam, 1940–at least 1942 [5];

Prof. Dr. Boss, Zürich, by September 30, 1966 [6];

Purchased from Boss by Marlborough Fine Art Galerie, Zürich, September 30, 1966–July 19, 1967 [7];

Purchased from Marlborough by Thomas D. Neelands Jr. (1902–72), New York, July 19, 1967–72;

Purchased at his posthumous sale, Important 19th and 20th Century Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, Sotheby Parke-Bernet, New York, April 26, 1972, lot 6, as Barrage sur la Seine à Bougival, by Wildenstein and Co., New York, 1972–May 20, 1987 [8];

Purchased from Wildenstein by Marion (née Helzberg, 1931–2013) and Henry (1922–2019) Bloch, Shawnee Mission, KS, May 20, 1987–June 15, 2015;

Their gift to The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 2015.

Notes

[1] In both the annotated catalogues for his 1903 sale, it is uncertain how the buyer’s name is spelled: either M. Gobetski or M. Gobeski; see copies in NAMA curatorial files. The buyer may have been a member of the artistic Godebski family, whose name was often misspelled in contemporary journals. Sculptor “Cyprian” Quentin Godebski (1835–1909) or his son and composer, François Joseph Joachim “Cyprien” Godebski (1866–1948) are likely candidates. The younger Godebski was in the same social circles as Feydeau. Other candidates are Cyprien’s daughter and pianist, Maria Sofia Olga Zenaida Godebski (1872–1950; later known as Misia Sert), who was also a friend and model to Pierre-Auguste Renoir; or Cyprian’s eldest son, Cyrien Xavier Leonard Godebski (1875–1937), who was a literary man and friends with the Post-Impressionists.

[2] For constituent, see Joachim Pissarro and Claire Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Critical Catalogue of Paintings (Paris: Wildenstein Institute Publications, 2005), no. 203, p. 2:173.

[3] See email from Walter Feilchenfeldt Jr. to Danielle Hampton Cullen, April 21, 2021, NAMA curatorial files. Walter Feilchenfeldt Sr. was head of Kunstsalon Paul Cassirer, Berlin, from 1926 until 1933, when Hitler’s rise to power forced him to resign from the Berlin firm. The head of the firm became Grete Ring. Feilchenfeldt worked primarily at the Amsterdam branch until 1939, and in 1948, he established his own gallery in Zürich. See http://www.walterfeilchenfeldt.ch/gallery/.

[4] Rudi and Lili Maas were clients of Walter Feilchenfeldt, who looked after their collection, which, beginning before World War II, was in storage with Kunsthandel Paul Cassirer, Amsterdam (the gallery was directed by Dr. Helmuth Lütjens). Rudi and Lili Maas emigrated to California in 1938, but the painting remained in Amsterdam. Feilchenfeldt made notes about the collections he looked after during the war. The Pissarro “Port de Marly” is recorded in the “Maas Collection” twice, in 1937 and 1942. See email from Walter Feilchenfeldt Jr. to Danielle Hampton Cullen, April 20, 2021, NAMA curatorial files.

[5] Robert Maas died in 1940. It is not clear when the painting left Paul Cassirer, Amsterdam, and if or when it was shipped to his widow; see email from Walter Feilchenfeldt Jr. to Danielle Hampton Cullen, April 20, 2021, NAMA curatorial files.

[6] Marlborough Fine Art Galerie identified the collector as “Prof. Dr. Boss, Zürich;” see email from Franz K. Plutschow, director, Marlborough International Fine Art, to Mackenzie Mallon, April 21, 2015, NAMA curatorial files.

This might be Prof. Dr. Medard Boss (1903–90), Zürich, a renowned Swiss psychoanalytic psychiatrist who was a medical faculty member at the University of Zürich. Boss was also an art collector. In 1959, he was a visiting professor at Harvard University, Cambridge, MA; at the University of Washington, Medical School, Washington, DC; and at the University of Madison, WI. That same year, the painting was lent to Wildenstein in New York, although Wildenstein does not have records on the identity of the lender, and the museum is unable to make a direct connection to Medard Boss. See email from Joseph Baillio, Wildenstein and Co., to MacKenzie Mallon, May 4, 2015, NAMA curatorial files.

[7] See email from Franz K. Plutschow, director, Marlborough International Fine Art, to MacKenzie Mallon, April 21, 2015, NAMA curatorial files.

[8] See email from Joseph Baillio, Wildenstein and Co., to Mackenzie Mallon, May 4, 2015, NAMA curatorial files.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Camille Pissarro, Waterworks of the Marly Machine at Bougival, 1871,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.638.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Camille Pissarro, Waterworks of the Marly Machine at Bougival, 1871,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.638.4033.

Camille Pissarro, The Seine at Bougival, 1870, oil on canvas, 20 1/4 x 32 3/8 in. (51.4 x 82.2 cm), Artizon Musuem, Tokyo.

Camille Pissarro, Barges on the Seine at Bougival, 1871, oil on canvas, 16 7/8 x 23 3/8 in. (43 x 59.5 cm), illustrated in Impressionist and Modern Art Evening Sale (New York: Sotheby’s, June 23, 2014), 190, (repro.).

Camille Pissarro, The Seine at Bougival, 1871, oil on canvas, 17 3/8 x 23 5/8 in. (44 x 60 cm), private collection, Switzerland.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Camille Pissarro, Waterworks of the Marly Machine at Bougival, 1871,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.638.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Camille Pissarro, Waterworks of the Marly Machine at Bougival, 1871,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.638.4033.

Possibly Exposition de tableaux par C. Pissarro, Bernheim-Jeune, Paris, March 22–April 15, 1899, no. 16, as Barrage à Pontoise.

Contrasts in Landscape: 19th and 20th Century Paintings and Drawings, Wildenstein, New York, closed October 31, 1959, no. 11, as The Banks of the Seine at Bougival.

Nature as Scene: French Landscape Painting from Poussin to Bonnard , Wildenstein, New York, October 29–December 6, 1975, no. 48, as The Weir on the Seine at Bougival.

Impressionists on the Seine: A Celebration of Renoir’s “Luncheon of the Boating Party,” The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC, September 21, 1996–February 23, 1997, no. 5, as The Lock on the Seine at Bougival.

Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, June 9–September 9, 2007, no. 6, as Banks of the Seine at Port Marly (Au bord de la Seine à Port Marly).

References

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Camille Pissarro, Waterworks of the Marly Machine at Bougival, 1871,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.638.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Camille Pissarro, Waterworks of the Marly Machine at Bougival, 1871,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.638.4033.

Possibly Exposition de tableaux par C. Pissarro, exh. cat. (Paris: Bernheim-Jeune, 1899), unpaginated, as Barrage à Pontoise.

Catalogue des Tableaux Modernes, Aquarelles, Pastels, Dessins appartenant à M. Georges Feydeau (Paris: Hôtel Drouot, 1903), 26, (repro.), as Barrage de la Seine à Pontoise.

Le Bonhomme, “La vie de Paris,” Le Figaro 49, no. 93 (April 3, 1903): 1.

T. S., “La Collection Feydeau,” Le Temps 43, no. 15,267 (April 3, 1903): [2], as Barrage de la Seine à Pontoise.

“Pour les Collectionneurs et les amateurs,” Journal des artistes 28, no. 15 (April 19, 1903): 4093, as Barrage de la Seine à Pontoise.

G. R., “A Chronicle of the Hôtel Drouot,” Burlington Gazette 1, no. 2 (May 1903): 58.

Ludovic Rodo Pissarro and Lionello Venturi, Camille Pissarro, Son Art—Son Œuvre (Paris: Paul Rosenberg, 1939), no. 125, pp. 1:97, 2: unpaginated, (repro.), as Barrage sur la Seine a [sic] Bougival.

Contrasts in Landscape: 19th and 20th Century Paintings and Drawings, exh. cat. (New York: Wildenstein, 1959), unpaginated, as Barrage of the Seine at Bougival.

Important 19th and 20th Century Paintings, Drawings, and Sculpture (New York: Sotheby, Parke-Bernet, 1972), 22–23, (repro.), as Barrage sur la Seine a [sic] Bougival.

Jacques Lorcey, “Feydeau Peinture et Collectionneur,” Bulletin de la société d’étude et de promotion des arts du spectacle 8 (1973): 39, as Barrage de la Seine à Pontoise.

Nature as Scene: French Landscape Painting from Poussin to Bonnard, exh. cat. (New York: Wildenstein, 1975), unpaginated, as The Weir on the Seine at Bougival.

Ralph E. Shikes and Paula Harper, Pissarro, His Life and Work (New York: Horizon Press, 1980), 97, (repro.), as Dam on the Seine at Louveciennes.

John Rewald et al., Camille Pissarro, 1830-1903, exh. cat. (London: Arts Council of Great Britain, 1980), 86.

Ludovico Rodo Pissarro and Lionello Venturi, Camille Pissarro, Son Art—Son Œuvre, 2nd rev. ed. (San Francisco: Alan Wofsy Fine Arts, 1989), no. 125, pp. 1:97, 2: unpaginated, (repro.), as Barrage sur la Seine a [sic] Bougival.

Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Pissarro and Pontoise: The Painter in a Landscape (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990), 41, 206n14.

Henry Gidel, Georges Feydeau (Paris: Flammarion, 1991), 187.

Eliza Rathbone et al., Impressionists on the Seine: A Celebration of Renoir’s Luncheon of the Boating Party, exh. cat. (Washington, DC: Counterpoint, 1996), 258, (repro.), as The Lock on the Seine at Bougival.

Jacques Lorcey, L’homme de chez Maxim’s: Georges Feydeau, sa vie (Paris: Séguier, 2004), 1:180.

Joachim Pissarro and Claire Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Critical Catalogue of Paintings (Paris: Wildenstein Institute Publications, 2005), no. 203, pp. 2:173, 3: 393, 402, 419, (repro.), as Barrage sur la Seine à Bougival.

Rebecca Dimling Cochran and Bobbie Leigh, “100 Top Collectors who have made a difference,” Art and Antiques (March 2006): 90.

Bobbie Leigh, “Magnificent Obsession,” Art and Antiques 29, no. 6 (June 2006): 60, 65, (repro.), as Lock on the Seine at Bougival.

Alice Thorson, “A final countdown—A rare showing of Impressionist paintings from the private collection of Henry and Marion Bloch is one of the inaugural exhibitions at the 165,000-square-foot glass-and-steel structure,” Kansas City Star (June 29, 2006): B1.

“Inaugural Exhibitions Celebrate Kansas City,” Member Magazine (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (Fall 2006): 3.

Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 10–11, 13, 48–51, 70, 156, (repro.), as Banks of the Seine at Port Marly (Au bord de la Seine à Port Marly).

Alice Thorson, “A Tiny Renoir Began an Impressive Obsession,” Kansas City Star (June 3, 2007): E4, (repro.), as Banks of the Seine at Port Marly.

“Lasting Impressions: A Tribute to Marion and Henry Bloch,” Member Magazine (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (Fall 2007): 11–12.

Steve Paul, “Pretty Pictures: Marion and Henry Bloch’s Collection of Superb Impressionist Masters,” Panache 4, no. 3 (Fall 2007): 20.

Alice Thorson, “Museum to Get 29 Impressionist Works from the Bloch Collection,” Kansas City Star (February 5, 2010): A1, as Banks of the Seine at Port Marly.

Carol Vogel, “Inside Art: Kansas City Riches,” New York Times 159, no. 54,942 (February 5, 2010): C26.

Thomas M. Bloch, Many Happy Returns: The Story of Henry Bloch, America’s Tax Man (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, 2011), 175.

Diane Stafford, “Bloch Gift to Go for Nelson Upgrade,” Kansas City Star 135, no. 203 (April 8, 2015): A8.

“Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Officially Accessions Bloch Impressionist Masterpieces,” Artdaily.org (July 25, 2015): http://artdaily.com/news/80246/Nelson-Atkins-Museum-of-Art-officially-accessions-Bloch-Impressionist-masterpieces#.V6oGwlKFO9I.

Julie Paulais, “Le Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art reçoit des tableaux impressionnistes en échange de leurs répliques,” Le Journal des arts (July 30, 2015): http://www.lejournaldesarts.fr/site/archives/docs_article/129801/le-nelson-atkins-museum-of-art-recoit-des-tableaux-impressionnistes-en-echange-de-leurs-repliques.php.

Josh Niland, “The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Acquires a Renowned Collection of Impressionist and Postimpressionist Art,” architecturaldigest.com (August 6, 2015): https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/nelson-atkins-museum-accessions-bloch-art-collection.

Nina Siegal, “Upon Closer Review, Credit Goes to Bosch,” New York Times 165, no. 57130 (February 2, 2016): C5.

“Nelson-Atkins to unveil renovated Bloch Galleries of European Art in winter 2017,” Artdaily.org (July 20, 2016): http://artdaily.com/news/88852/Nelson-Atkins-to-unveil-renovated-Bloch-Galleries-of-European-Art-in-winter-2017-#.W-NDepNKhaQ.

“Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art celebrates generosity of Henry Bloch with new acquisition,” Artdaily.org (October 18, 2016): http://artdaily.com/news/90923/Nelson-Atkins-Museum-of-Art-celebrates-generosity-of-Henry-Bloch-with-new-acquisition#.W-NDv5NKhaQ.

Catherine Futter et al., Bloch Galleries: Highlights from the Collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2016), 72, (repro.), as Banks of the Seine at Port Marly.

Kelly Crow, “Museum Rewards Donor with Fake Art to Hang at Home,” Wall Street Journal (January 25, 2017): https://www.wsj.com/articles/museum-rewards-donor-with-fake-art-to-hang-at-home-1485370768.

Albert Hect, “Henry Bloch’s Masterpieces Collection to Go on Display at Nelson-Atkins Museum,” Jewish Business News (February 26, 2017): http://jewishbusinessnews.com/2017/02/26/henry-bloch-masterpieces-collection/.

David Frese, “Inside the Bloch Galleries: An interactive experience,” Kansas City Star 137, no. 169 (March 5, 2017): 1D, 4D, (repro.), as Banks of the Seine at Port Marly.

“Editorial: Thank you, Henry and Marion Bloch,” Kansas City Star (March 7, 2017): http://www.kansascity.com/opinion/editorials/article137040948.html [repr., “Thank you, Henry and Marion Bloch,” Kansas City Star 137, no. 172 (March 8, 2017): 16A].

Hampton Stevens, “(Not Actually) 12 Things To Do During The Big 12 Tournament,” Flatland: KCPT’s Digital Magazine (March 9, 2017): http://www.flatlandkc.org/arts-culture/sports/not-actually-12-big-12-tournament/.

Laura Spencer, “The Nelson-Atkins’ Bloch Galleries feature Old Masterworks and New Technology,” KCUR (March 10, 2017): http://kcur.org/post/nelson-atkins-bloch-galleries-feature-old-masterworks-and-new-technology#stream/0.

Victoria Stapley-Brown, “Nelson-Atkins Museum’s new European art galleries come with a ‘love story’,” Art Newspaper (March 10, 2017): http://theartnewspaper.com/news/museums/nelson-atkins-museum-s-new-european-art-galleries-come-with-a-love-story/.

Harry Bellet, “Don du ciel pour le Musée Nelson-Atkins,” Le Monde (March 13, 2017): http://www.lemonde.fr/arts/article/2017/03/13/don-du-ciel-pour-le-musee-nelson-atkins_5093543_1655012.html.

Menachem Wecker, “Jewish Philanthropist Establishes Kansas City as Cultural Mecca,” Forward (March 14, 2017): http://forward.com/culture/365264/jewish-philanthropist-establishes-kansas-city-as-cultural-mecca/ [repr., in Menachem Wecker, “Kansas City Collection Is A Chip Off the Old Bloch,” Forward (March 17, 2017): 20–22], as Banks of the Seine at Port Marly.

Juliet Helmke, “The Bloch Collection Takes up Residence in Kansas City’s Nelson Atkins Museum,” BoulinArtInfo International (March 15, 2017): http://www.blouinartinfo.com/news/story/2005267/the-bloch-collection-takes-up-residence-in-kansas-citys.

Erich Hatala Matthes, “Digital replicas are not soulless—they help us engage with art,” Apollo (March 23, 2017): https://www.apollo-magazine.com/digital-replicas-3d-printing-original-artworks/.

Louise Nicholson, “How Kansas City got its magnificent museum,” Apollo (April 7, 2017): https://www.apollo-magazine.com/how-kansas-city-got-its-magnificent-museum/.

Lilly Wei, “Julián Zugazagoitia: ‘Museums should generate interest and open a door that leads to further learning’,” Studio International (August 21, 2017): http://studiointernational.com/index.php/julian-zugazagoitia-director-nelson-atkins-museum-of-art-kansas-city-interview.

Robert D. Hershey Jr., “Henry Bloch, H&R Block’s cofounder, dies at 96,” Boston Globe (April 23, 2019): https://www3.bostonglobe.com/metro/obituaries/2019/04/23/henry-bloch-block-cofounder/?arc404=true.

Robert D. Hershey Jr., “Henry W. Bloch, Tax-Preparation Pioneer (and Pitchman), Is Dead at 96,” New York Times (April 23, 2019): https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/23/obituaries/henry-w-bloch-dead.html.

Claire Selvin, “Henry Wollman Bloch, Collector and Prominent Benefactor of Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Is Dead at 96,” ArtNews (April 23, 2019): http://www.artnews.com/2019/04/23/henry-bloch-dead-96/.

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “Henry Bloch, co-founder of H&R Block, dies at 96,” Kansas City Star 139, no. 219 (April 24, 2019): 1A.

“Henry Wollman Bloch (1922-2019),” Art Forum (April 24, 2019): https://www.artforum.com/news/henry-wollman-bloch-1922-2019-79547.

Frank Morris, “Henry Bloch, Co-Founder Of H&R Block, Dies At 96,” npr.org (April 24, 2019): https://www.npr.org/2019/04/24/716641448/henry-bloch-co-founder-of-h-r-block-dies-at-96.

Ignacio Villarreal, “Nelson-Atkins mourns loss of Henry Bloch,” ArtDaily.org (April 24, 2019): http://artdaily.com/news/113035/Nelson-Atkins-mourns-loss-of-Henry-Bloch#.XMB76qR7laQ

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “H&R Bloch co-founder, philanthropist Bloch dies,” Cass County Democrat Missourian 140, no. 29 (April 26, 2019): 1A

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “KC businessman and philanthropist Henry Bloch dies,” Lee’s Summit Journal 132, no. 79 (April 26, 2019): 3A, (repro.).

Luke Nozicka, “Family and friends remember Henry Bloch of H&R Block,” Kansas City Star 139, no. 225 (April 30, 2019): 4A [repr., Luke Nozicka, “Family and friends remember Henry Bloch of H&R Block,” Kansas City Star 139, no. 228 (May 3, 2019): 3A].

Eric Adler, “Sold for $3.25 million, Bloch’s home in Mission Hills may be torn down,” Kansas City Star 141, no. 90 (December 16, 2020): 2A.