![]()

Berthe Morisot, Daydreaming, 1877

| Artist | Berthe Morisot, French, 1841–95 |

| Title | Daydreaming |

| Object Date | 1877 |

| Alternate and Variant Titles | Reveuse; Rêverie |

| Medium | Pastel on canvas |

| Dimensions (Unframed) | 19 3/4 x 24 in. (50.2 x 61 cm) |

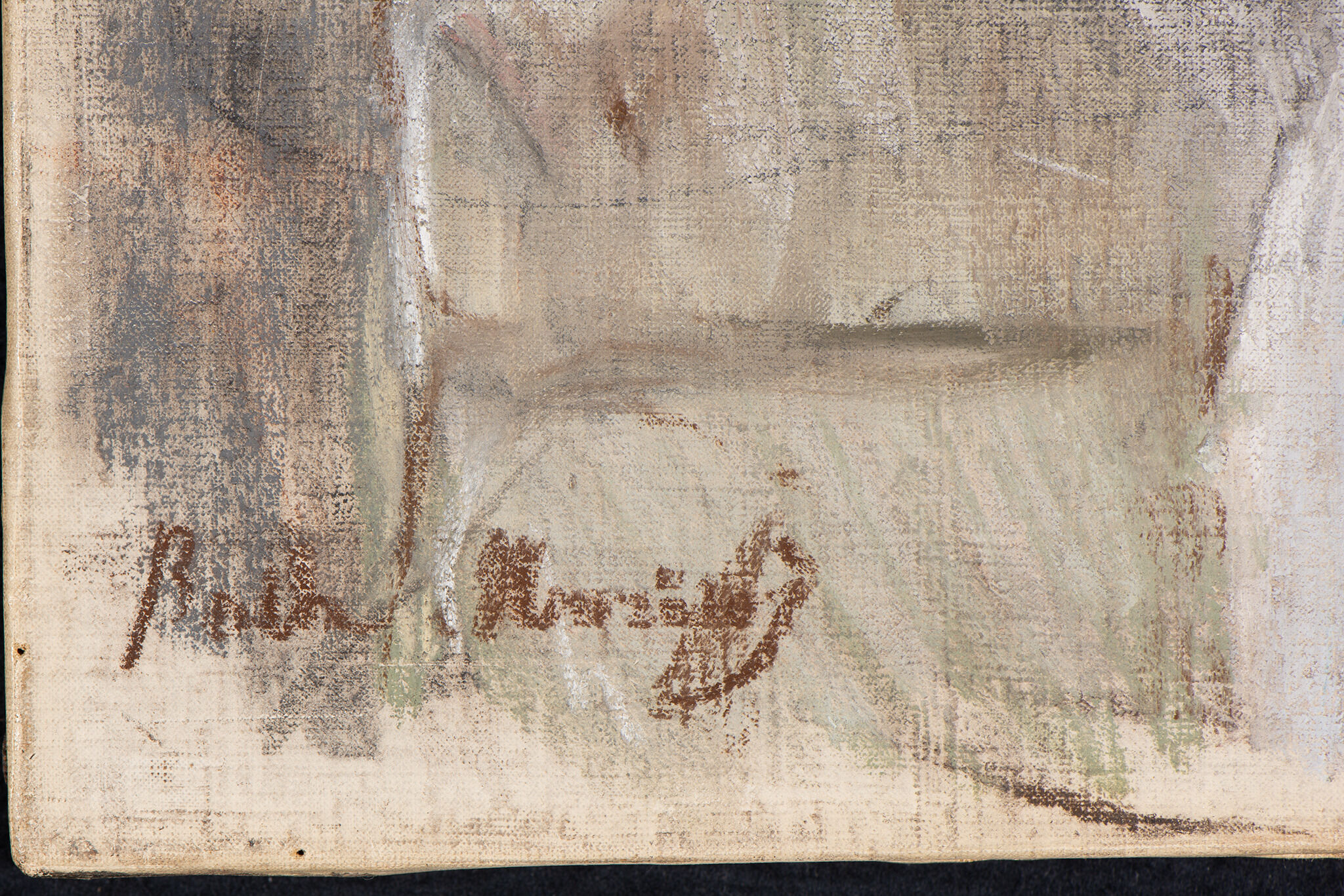

| Signature | Signed lower left: Berthe Morisot |

| Credit Line | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Purchase: acquired through the generosity of an anonymous donor, F79-47 |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Berthe Morisot, Daydreaming, 1877,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.634.5407.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Berthe Morisot, Daydreaming, 1877,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.634.5407.

Perhaps more than any other Impressionist, Berthe Morisot (1841–95) is often singled out for her painterly technique, particularly in pastelpastel: A type of drawing stick made from finely ground pigments or other colorants (dyes), fillers (often ground chalk), and a small amount of a polysaccharide binder (gum arabic or gum tragacanth). While many artists made their own pastels, during the nineteenth century, pastels were sold as sticks, pointed sticks encased in tightly wound paper wrappers, or as wood encased pencils. Pastels can be applied dry, dampened, or wet, and they can be manipulated with a variety of tools including paper stumps, chamois cloth, brushes, or fingers. Pastel can also be ground and applied as a powder, or mixed with water to form a paste. Pastel is a friable media, meaning that it is powdery or crumbles easily. To overcome this difficulty, artists have used a variety of fixatives to prevent image loss.. This medium increasingly occupied the artist’s attention in the years 1870–80, and she most often employed it in her portraits of women.1Of the six pastels at the Impressionist exhibitions between 1874 and 1881, three were portraits of women. See Ruth Berson, The New Painting: Impressionism, 1874–1886: Documentation, Exhibited Works, new ed. (San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1996), no. 1-108, p. 10, as Portrait de Mademoiselle M.T.; no. 1-109, p. 10, as Un Village; no. 1-HC2, p. 11, as Portrait of Madame Pontillon; no. 3-125, p. 119, as Pastel; no. 3-126, p. 119, as Vue de la Tamise; no. 6-59, p. 182, as Portrait d’enfant. Morisot made her debut as a pastelist at the first Impressionist exhibition in 1874, where she showed three pastels, including two portraits of women in the home: Portrait de Mademoiselle M. T. and Portrait of Madame Pontillon.2Marie-Louise Bataille and Georges Wildenstein, Berthe Morisot: Catalogue des Peintures, Pastels et Aquarelles (Paris: Les Beaux-Arts, 1961), no. 426, p. 51, as Portrait de Madeline Thomas; no. 419, p. 51, as Portrait of Madame Pontillon. Critic Gustave Geffroy recognized early on the preeminent qualities of Morisot’s Impressionist style, writing: “This woman is accomplishing the rarest of things: a painting of reality, observed and life driven; a delicate painting that is stroked lightly and filled with presence.”3Gustave Geffroy, “Notre Temps: Berthe Morisot,” La Justice, March 4, 1895. Geoffroy also remarked that “no one represents Impressionism with more refined talent and authority than Madame Morisot.” See Gustave Geffroy, “L’Exposition des artistes Indépendants,” La Justice, April 19, 1881. Morisot’s freely drawn portraits of fashionable women in the home demonstrated that modernity was not an experience reserved only for men in the public sphere but a multifaceted one, lived differently by women in the domestic realm.

Included in the third Impressionist exhibition in 1877, Daydreaming—a title assigned posthumously by dealer Paul Durand-Ruel in 1896—embodies the artist’s ambitions as a pastelist and her profound ability to exploit the medium for its purportedly “feminine” associations.4Berthe Morisot (Madame Eugène Manet): Exposition de son œuvre, exh. cat., 2nd ed. (Paris: Durand-Ruel, 1896), no. 176, p. 31, as Rêveuse. This is also the primary title in the catalogues raisonnées of the artist. See Monique Angoulvent, Berthe Morisot (Paris: Albert Morancé, 1933), no. 93, p. 122, as Jeune fille en rose (Rêveuse); and Bataille and Wildenstein, Berthe Morisot, no. 434, pp. 52, 225, as Rêveuse. Indeed, Morisot saw fit to title the Nelson-Atkins picture simply Pastel, while she gave her other works titles that reflect their subject matter, giving the impression that she considered the Nelson-Atkins picture, above all, an exercise in the technical and conceptional possibilities of the medium. The later title, Daydreaming, was no doubt due to contemporaneous scholars’ and poets’ rapt obsession with likening a woman on a sofa to the idea of the dream.5Artists such as Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Edouard Manet dedicated several works to this theme. See, for example, Edouard Manet, Woman with Fans, 1874, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Portrait of Madame Claude Monet, 1872, Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, Lisbon. For more on this, see Beatrice Farwell’s chapter, “Manet, Morisot and Propriety,” in Kathleen Adler and T. J. Edelstein, Perspectives on Morisot (New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1990), 45–56. For Morisot’s images of women on the sofa, see Bataille and Wildenstein, Berthe Morisot, no. 61, p. 61; no. 434, p. 52; no. 339, p. 46; and no. 338, p. 46.

The Nelson-Atkins picture portrays a private moment: a young woman in an interior is seated with her legs outstretched on a white sofa. With her right hand demurely placed on her lap, she rests her left arm on the back of the sofa. Soft brown tendrils of hair frame the model’s face, while her remaining curls are divided into large braids above her head in a loose coiffure, ornamented with a single black velvet ribbon.6For Parisian hairstyles of the 1870s, see Geri Walton, “Hairstyles of 1870: Curls, Plaits, and Twists,” Geri Walton: Unique Histories from the 18th and 19th Centuries (blog), May 22, 2014, https://www.geriwalton.com/hairstyles-of-1870. Black satin slippers with gold accents dangle from her feet at the edge of the sofa. In her left hand, she casually holds a light blue uchiwauchiwa: The uchiwa is a fan format that is thought to have originated in Japan. The uchiwa is a rigid fan that does not fold and is composed of a bamboo or wooden handle that is split, dampened, and spread out into thin ribs. These are often held in place or spaced out with two lines of string or thread that is woven around the ribs. The ribs are covered with paper, which is often painted or printed., a traditional Japanese fan that was a popular accessory for women in late nineteenth-century Paris.7The presence of the traditional Japanese fan was, no doubt, related to France’s obsession with Japanese art and culture at this time. She engages her viewers with an air of studied indifference, seemingly aware she is on public display.8The male gaze is discussed in the literature of Griselda Pollock and Linda Nochlin. See Linda Nochlin, “Morisot’s Wet Nurse: The Construction of Work and Leisure in Impressionist Painting,” in Adler and Edelstein, Perspectives on Morisot, 231–43; and Griselda Pollock, “Modernity and the Spaces of Femininity,” in Vision and Difference: Femininity, Feminism, and Histories of Art (London: Routledge, 1988), 50–90. For recent scholarship on Morisot’s “modern femininity,” see Sylvie Patry, “Berthe Morisot: Simulating Ambiguities,” in Cindy Kang et al., Berthe Morisot: Female Impressionist, exh. cat. (New York: Rizzoli Electa, 2018), 15–51.

The model is posed inside a room with chintz floral wallpaper, most likely in the artist’s sixteenth arrondissement residence that she occupied with her husband, Eugène Manet, after their marriage in 1874.9Christopher Lloyd, Impressionist and Post-Impressionist Drawings (London: Thames and Hudson, 2019), 138. By the mid-nineteenth century, it had become stylish to decorate the walls and sofas of ladies’ dressing rooms and private sitting rooms with delicate, floral motifs like the one seen here.10For more on the history of chintz wall fabric, see “Textile Influences on Wallpaper,” Victoria and Albert Museum website, last modified May 20, 2013, http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/t/textile-influences-on-wallpaper. Newly married, Morisot would have wanted the interior design of her private quarters to reflect the contemporary taste of the haute bourgeoisiehaute bourgeoisie: French for ”the upper middle class“ in order to affirm her new role as mistress of the home.11For more on the dual history of women and the mid-nineteenth century home, see Beverly Gordon, “Woman’s Domestic Body: The Conceptual Conflation of Women and Interiors in the Industrial Age,” Winterthur Portfolio 31, no. 4 (1996): 281–301. These designated female rooms evidently also acted as a studio for Morisot, as several of her pastel portraits of women in the home include this light chintz floral wallpaper and matching upholstered sofa.12See, for example, Young Woman Seated on a Sofa, ca. 1879, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; The Cheval-Glass, 1876, Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid; Woman at her Toilette, 1875/1880, Art Institute of Chicago; and Reclining Woman in Gray, 1879, private collection. Morisot considered her roles as both an upper-middle-class wife and an artist when carefully selecting this charming, intimate design.

Morisot’s soft palette of pinks and whites exploits the “feminine” associations of the pastel medium. Critics from the third Impressionist exhibition praised Morisot for her exemplary treatment of the model’s peignoir, or dressing gown, with pastel applied in varying, individual strokes of white hues to convey the delicate folds of the gossamer fabric. These reviews also indicate that the peignoir originally appeared more pink than it does now, which could be due to pigment fade.13References dating as far back as 1907 use the title Le Femme en peignoir rose. For this title, see Roger Marx, “Les Femmes Peintres et l’Impressionnisme: Berthe Morisot,” Gazette des Beaux-Arts, no. 606 (December 1, 1907): 304, 498–99. For similar titles that suggest the dress was pink, see also Roger Marx, Maîtres d’hier et d’aujourd’hui (Paris: Calmann-Lévy, 1914), 310, as Femme en peignoir rose; and Monique Angoulvent, Berthe Morisot (Paris: Albert Morancé, 1933), no. 93, p. 122, as Jeune fille en rose (Rêveuse). Critics such as Georges Rivière, for instance, wrote, “what a pretty picture of a young woman in a soft pink peignoir laying on a sofa.”14“quel joli tableau que la jeune femme en peignoir rose couchée sur un canapé.” Georges Rivière, “L’Exposition des impressionnistes,” L’impressionniste, no. 2 (April 14, 1877): 4. The muted color of the model’s dress is just one of the many elements that contribute to the overall delicate sensibility of the composition. The diffusion of light filtering in through the muslin curtains behind the sofa envelops the model as she surrenders to the warmth of the sun and the passing of the morning light, reflecting the often-fleeting moments of domestic life. Made up of a symphony of blushing pinks and soft whites, this dreamlike atmosphere was thoughtfully orchestrated by the artist to complement her model’s ethereal appearance and to further convey a level of domestic intimacy.

One of the most compelling features of this portrait is the model’s peignoir, a loose-fitting dressing gown without a waist seam that became increasingly fashionable for women in late nineteenth-century France. Meaning “to comb the hair,” peignoirs were worn in the home while women performed their morning routines, and they were only worn among close friends and family.15For more on this style of dress, see Gloria Groom and Heidi Brevik-Zender, Impressionism, Fashion and Modernity, exh. cat. (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2012), 107–33. Contemporaneous fashion plates often illustrated the peignoir. A fashion plate from Le Moniteur de la mode, one of the premier fashion magazines and tastemakers of the day, makes an interesting comparison to Daydreaming and illustrates Morisot’s awareness of fashion and her keen understanding of how it had the power to create meaning in her portraits of women (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. E. Préval (b. ca. 1845), “Modele de Peignoir,” in &ldquoDescription de la Toilette,” Le Moniteur de la mode, no. 18 (May 1874): 210

Fig. 1. E. Préval (b. ca. 1845), “Modele de Peignoir,” in &ldquoDescription de la Toilette,” Le Moniteur de la mode, no. 18 (May 1874): 210

Fig. 2. James Tissot, Seaside (July: Specimen of a Portrait), 1878, oil on fabric, 34 7/16 x 24 in. (87.5 x 61 cm), Cleveland Museum of Art, Bequest of Noah L. Butkin, 1980.288

Fig. 2. James Tissot, Seaside (July: Specimen of a Portrait), 1878, oil on fabric, 34 7/16 x 24 in. (87.5 x 61 cm), Cleveland Museum of Art, Bequest of Noah L. Butkin, 1980.288

Fig. 4. Adele d’Affry (Marcello), Berthe Morisot, 1875, oil on canvas, 66 1/8 x 45 1/4 in. (168 x 115 cm), Musée d’art et d’historie Fribourg, Switzerland

Fig. 4. Adele d’Affry (Marcello), Berthe Morisot, 1875, oil on canvas, 66 1/8 x 45 1/4 in. (168 x 115 cm), Musée d’art et d’historie Fribourg, Switzerland

Fig. 5. Charles Reutlinger, Portrait of Louise Méret, actress at the Théâtre du Vaudeville, ca. 1868–72, photograph (albumen print), 3 1/2 x 2 1/8 in. (9 x 5.5 cm), Musée Carnavalet, Histoire de Paris, PH53780. CC0 Paris Musées / Musée Carnavalet

Fig. 5. Charles Reutlinger, Portrait of Louise Méret, actress at the Théâtre du Vaudeville, ca. 1868–72, photograph (albumen print), 3 1/2 x 2 1/8 in. (9 x 5.5 cm), Musée Carnavalet, Histoire de Paris, PH53780. CC0 Paris Musées / Musée Carnavalet

Notes

-

Of the six pastels at the Impressionist exhibitions between 1874 and 1881, three were portraits of women. See Ruth Berson, The New Painting: Impressionism, 1874–1886: Documentation, Exhibited Works, new ed. (San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1996), no. 1-108, p. 10, as Portrait de Mademoiselle M.T.; no. 1-109, p. 10, as Un Village; no. 1-HC2, p. 11, as Portrait of Madame Pontillon; no. 3-125, p. 119, as Pastel; no. 3-126, p. 119, as Vue de la Tamise; no. 6-59, p. 182, as Portrait d’enfant.

-

Marie-Louise Bataille and Georges Wildenstein, Berthe Morisot: Catalogue des Peintures, Pastels et Aquarelles (Paris: Les Beaux-Arts, 1961), no. 426, p. 51, as Portrait de Madeline Thomas; no. 419, p. 51, as Portrait of Madame Pontillon.

-

Gustave Geffroy, “Notre Temps: Berthe Morisot,” La Justice, March 4, 1895. Geoffroy also remarked that “no one represents Impressionism with more refined talent and authority than Madame Morisot.” See Gustave Geffroy, “L’Exposition des artistes Indépendants,” La Justice, April 19, 1881.

-

Berthe Morisot (Madame Eugène Manet): Exposition de son œuvre, exh. cat., 2nd ed. (Paris: Durand-Ruel, 1896), no. 176, p. 31, as Rêveuse. This is also the primary title in the catalogues raisonnées of the artist. See Monique Angoulvent, Berthe Morisot (Paris: Albert Morancé, 1933), no. 93, p. 122, as Jeune fille en rose (Rêveuse); and Bataille and Wildenstein, Berthe Morisot, no. 434, pp. 52, 225, as Rêveuse.

-

Artists such as Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Edouard Manet dedicated several works to this theme. See, for example, Edouard Manet, Woman with Fans, 1874, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Portrait of Madame Claude Monet, 1872, Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, Lisbon. For more on this, see Beatrice Farwell’s chapter, “Manet, Morisot and Propriety,” in Kathleen Adler and T. J. Edelstein, Perspectives on Morisot (New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1990), 45–56. For Morisot’s images of women on the sofa, see Bataille and Wildenstein, Berthe Morisot, no. 61, p. 61; no. 434, p. 52; no. 339, p. 46; and no. 338, p. 46.

-

For Parisian hairstyles of the 1870s, see Geri Walton, “Hairstyles of 1870: Curls, Plaits, and Twists,” Geri Walton: Unique Histories from the 18th and 19th Centuries (blog), May 22, 2014, https://www.geriwalton.com/hairstyles-of-1870.

-

The presence of the traditional Japanese fan was, no doubt, related to France’s obsession with Japanese art and culture at this time.

-

The male gaze is discussed in the literature of Griselda Pollock and Linda Nochlin. See Linda Nochlin, “Morisot’s Wet Nurse: The Construction of Work and Leisure in Impressionist Painting,” in Adler and Edelstein, Perspectives on Morisot, 231–43; and Griselda Pollock, “Modernity and the Spaces of Femininity,” in Vision and Difference: Femininity, Feminism, and Histories of Art (London: Routledge, 1988), 50–90. For recent scholarship on Morisot’s “modern femininity,” see Sylvie Patry, “Berthe Morisot: Simulating Ambiguities,” in Cindy Kang et al., Berthe Morisot: Female Impressionist, exh. cat. (New York: Rizzoli Electa, 2018), 15–51.

-

Christopher Lloyd, Impressionist and Post-Impressionist Drawings (London: Thames and Hudson, 2019), 138.

-

For more on the history of chintz wall fabric, see “Textile Influences on Wallpaper,” Victoria and Albert Museum website, last modified May 20, 2013, http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/t/textile-influences-on-wallpaper.

-

For more on the dual history of women and the mid-nineteenth century home, see Beverly Gordon, “Woman’s Domestic Body: The Conceptual Conflation of Women and Interiors in the Industrial Age,” Winterthur Portfolio 31, no. 4 (1996): 281–301.

-

See, for example, Young Woman Seated on a Sofa, ca. 1879, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; The Cheval-Glass, 1876, Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid; Woman at her Toilette, 1875/1880, Art Institute of Chicago; and Reclining Woman in Gray, 1879, private collection.

-

References dating as far back as 1907 use the title La Femme en peignoir rose. For this title, see Roger Marx, “Les Femmes Peintres et l’Impressionnisme: Berthe Morisot,” Gazette des Beaux-Arts, no. 606 (December 1, 1907): 304, 498–99. For similar titles that suggest the dress was pink, see also Roger Marx, Maîtres d’hier et d’aujourd’hui (Paris: Calmann-Lévy, 1914), 310, as Femme en peignoir rose; and Monique Angoulvent, Berthe Morisot (Paris: Albert Morancé, 1933), no. 93, p. 122, as Jeune fille en rose (Rêveuse).

-

“quel joli tableau que la jeune femme en peignoir rose couchée sur un canapé.” Georges Rivière, “L’Exposition des impressionnistes,” L’impressionniste, no. 2 (April 14, 1877): 4.

-

For more on this style of dress, see Gloria Groom and Heidi Brevik-Zender, Impressionism, Fashion and Modernity, exh. cat. (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2012), 107–33.

-

For more on this, see Anne Schirrmeister’s chapter, “La Dernière Mode: Berthe Morisot and Costume,” in Adler and Edelstein, Perspectives on Morisot, 103–15.

-

The model for Daydreaming and her dress are similar to those of Morisot’s 1870s series of women at their toilette: combing their hair, dressing, and gazing into the mirror, all depicted in progressive stages of undress. See, for example, Woman at her Toilette, 1875/1880, Art Institute of Chicago; The Cheval-Glass, 1876, Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid; and Young Woman Powdering Her Face, 1877, Musée d’Orsay, Paris. For the series, see Anne Higonnet’s chapter, “Mirrored Bodies,” in Berthe Morisot: Images of Women (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1992), 159–94.

-

There are at least four portraits of Morisot by Marcello. See Elisabeth Ryan-Gurley, “Berthe Morisot: Quatre portraits inédits par Marcello,” L’Estampille (February 1985): 14–21. The influence these two women had on one another’s art is palpable through their work from the mid-1870s on and is perceptible in the poses adopted by many of their models. The relationship between these two artists has yet to be fully studied. At the suggestion of Marcello, Morisot did try her hand at sculpture, producing a bronze Head of Julie Manet (1886; North Carolina Museum of Art.) For more on Marcello as an artist, see Gianna A. Mina, Marcello: Adèle d’Affry (1836–1879), Herzogin von Catiglione Colonna (Milan: 5 Continents, 2014), and Caterina Y. Pierre, “Marcello’s Heroic Sculpture,” Woman’s Art Journal 22, no. 1 (2001): 14–20.

-

These fans were often decorated and gifted to her by artists such as Edgar Degas. For more on this, see Marc Gerstein, “Degas’s Fans,” Art Bulletin 64, no. 1 (1982): 105–18.

-

This connection was first proposed by Hughes Wilhelm, Berthe Morisot, 1841–1895: A Retrospective, exh. cat. (Tokyo: APT International, 2007), 74–75. I have been unable to verify the life dates of Louise Méret, but there was a woman named Louise Méret (1851–1909), who was born in Cher, a department in the region of Centre-Val de Loire. Morisot’s family was from this same region in France, and Morisot herself was born in Bourges, a neighboring town to Cher. Moreover, the artist’s father, Edmé Tiburce Morisot, worked as a prefect for the Department of Cher. If this is indeed the same person as the sitter, she would have been twenty-six when she modeled for the pastel by Morisot.

Interestingly, Morisot herself would have her portrait taken by Reutlinger in 1875 (see https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Berthe_Morisot,_1875.jpg). Tracing Méret’s connection to both Morisot and Reutlinger has been a great help in furthering the idea that the model might be her. For more on Méret’s life, see the NAMA curatorial files.

-

The coiffure and profile is also similar to the model in Morisot’s Young Woman in Gray, Reclining, painted in 1879 (private collection). As with the Nelson-Atkins pastel, the identity of the woman is unknown. See Wilhelm, Berthe Morisot, 1841–1895, 74.

-

Méret’s profession is reflected in the title assigned to her portrait by Reutlinger (Fig. 5).

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Rachel Freeman, “Berthe Morisot, Daydreaming, 1877,” technical entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.634.2088.

MLA:

Freeman, Rachel. “Berthe Morisot, Daydreaming, 1877,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.634.2088.

Daydreaming is as much a study of the Purkinje effectPurkinje effect: Discovered by Czechoslovakian physiologist and anatomist Johannes Evangelist Purkinje (1787–1869), the Purkinje effect relates to the human eye’s greater sensitivity to the blue and blue-green region of the visible light spectrum in low light level situations. At very low light levels, when the human eye can no longer see color, lighter blues and greens will appear lighter than reds and oranges of the same value.1Samuel J. Williamson and Herman Z. Cummins, Light and Color in Nature and Art (New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1983), 170. as a depiction of a woman in repose on a warm day. Berthe Morisot explores the light and shadow created by backlighting the sitter with a window covered by a filmy curtain, and the lower light levels cause the highlights to appear blue. The uchiwauchiwa: The uchiwa is a fan format that is thought to have originated in Japan. The uchiwa is a rigid fan that does not fold and is composed of a bamboo or wooden handle that is split, dampened, and spread out into thin ribs. These are often held in place or spaced out with two lines of string or thread that is woven around the ribs. The ribs are covered with paper, which is often painted or printed. fan and the sitter’s slippers are the only objects lit by the full spectrum of sunlight, and they are depicted with shades that include red and yellow. The pastel also recalls Morisot’s oil painting technique and her comfort with canvas and liquid paint.

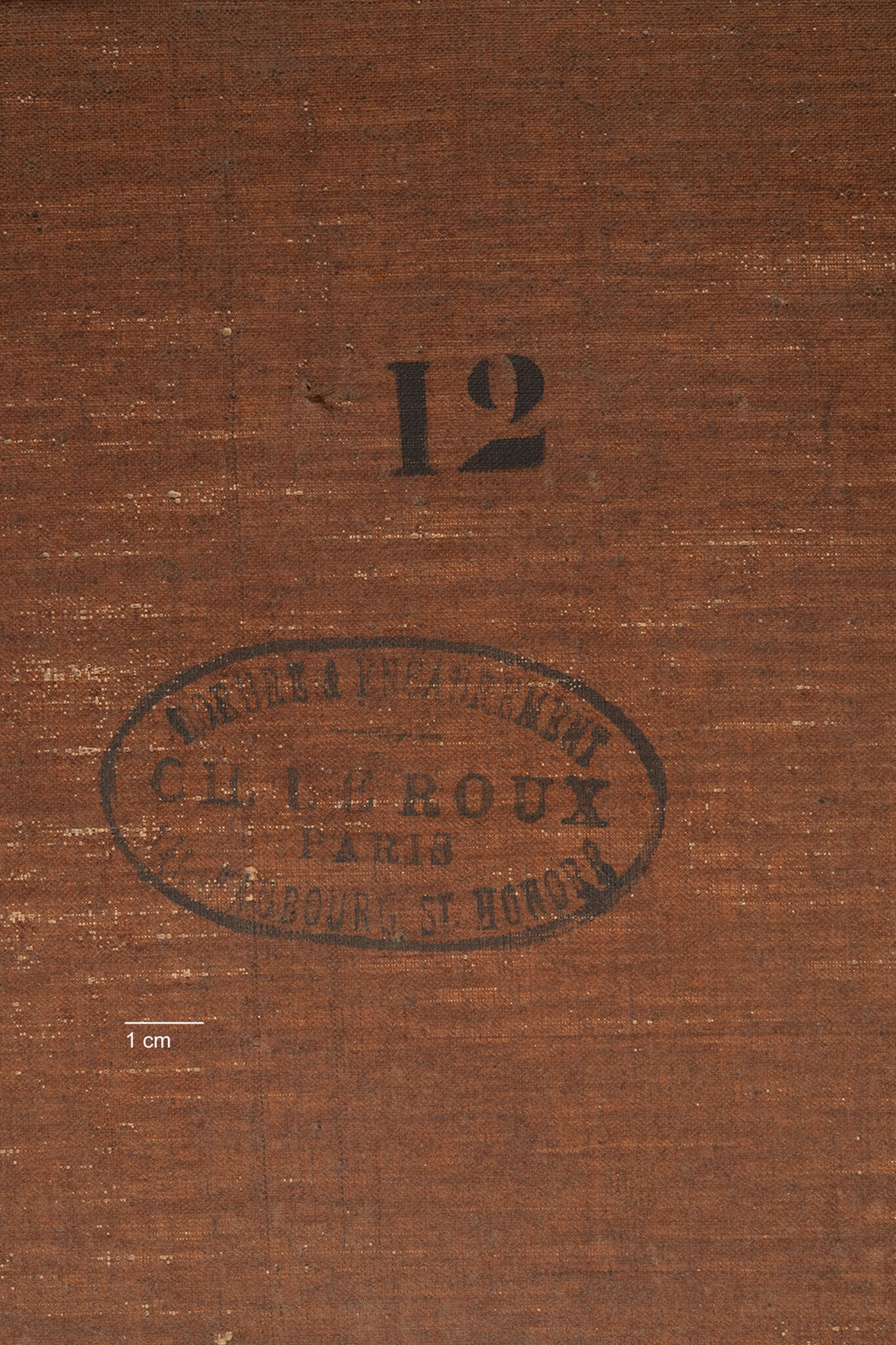

The stretcher is a five-member wooden mortise-and-tenon construction with beveled outer edges. To maintain tension, the stretcher is outfitted with two wooden keys in each corner and a single key on either side of the crossbar (Fig. 7). A 1.3-centimeter (1/2-inch) tacking edgetacking edge: The outer edges of canvas that wrap around and are attached to the stretcher or strainer with tacks or staples. See also tacking margin. is folded around the outer perimeter of the stretcher and attached with evenly spaced tacks. Although the tacks appear to be in their original locations, no two sides bear the same number of tacks. Beyond the tacking margin, approximately three millimeters (approximately 1/8 inch) of canvas wraps around the back of the stretcher. There are several holes in each tacking margin that do not appear to relate to the current stretching and might be the locations of temporary tacks that held the canvas in place while the current tacks were set, or they may be from nails used in a previous framing campaign. The canvas appears to be covered with a single layer of ecru or cream-toned groundground layer: An opaque preparatory layer applied to the support, either commercially or by the artist, to prevent absorption of the paint into the canvas or panel. See also priming layer.,2Commercially prepared grounds came in a range of tints, including ecru and shades of yellow (which were closer to a cream color than yellow). See Anthea Callen, The Art of Impressionism: Painting Technique and the Making of Modernity (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 67. which produces a mild yellow UV-induced fluorescenceultraviolet (UV) fluorescence or UV-induced visible fluorescence: The reflected visible light produced when painting materials interact with ultraviolet (UV) radiation. Not all materials fluoresce, but the color and intensity of the fluorescence is frequently used to differentiate between original and restoration materials, characterize the varnish layers, or reveal the distribution of pigments across the composition. when exposed to ultraviolet radiation and which contains lead.3See XRF report, November 24, 2021, NAMA conservation file. The ground extends to the edge of the canvas, indicating that it was applied before the canvas was attached to the stretcher.

Fig. 7. The back of the artwork showing the joining of the stretcher, location of keys, and remnants of papers used to seal the back of the frame during previous framing campaigns, Daydreaming (1877)

Fig. 7. The back of the artwork showing the joining of the stretcher, location of keys, and remnants of papers used to seal the back of the frame during previous framing campaigns, Daydreaming (1877)

Fig. 8. Infrared image of Daydreaming (1877). The underdrawing includes the panes of window glass, as well as the sitter, the divan, and the pillow behind her back. An “x” in the face is indicated by an arrow.

Fig. 8. Infrared image of Daydreaming (1877). The underdrawing includes the panes of window glass, as well as the sitter, the divan, and the pillow behind her back. An “x” in the face is indicated by an arrow.

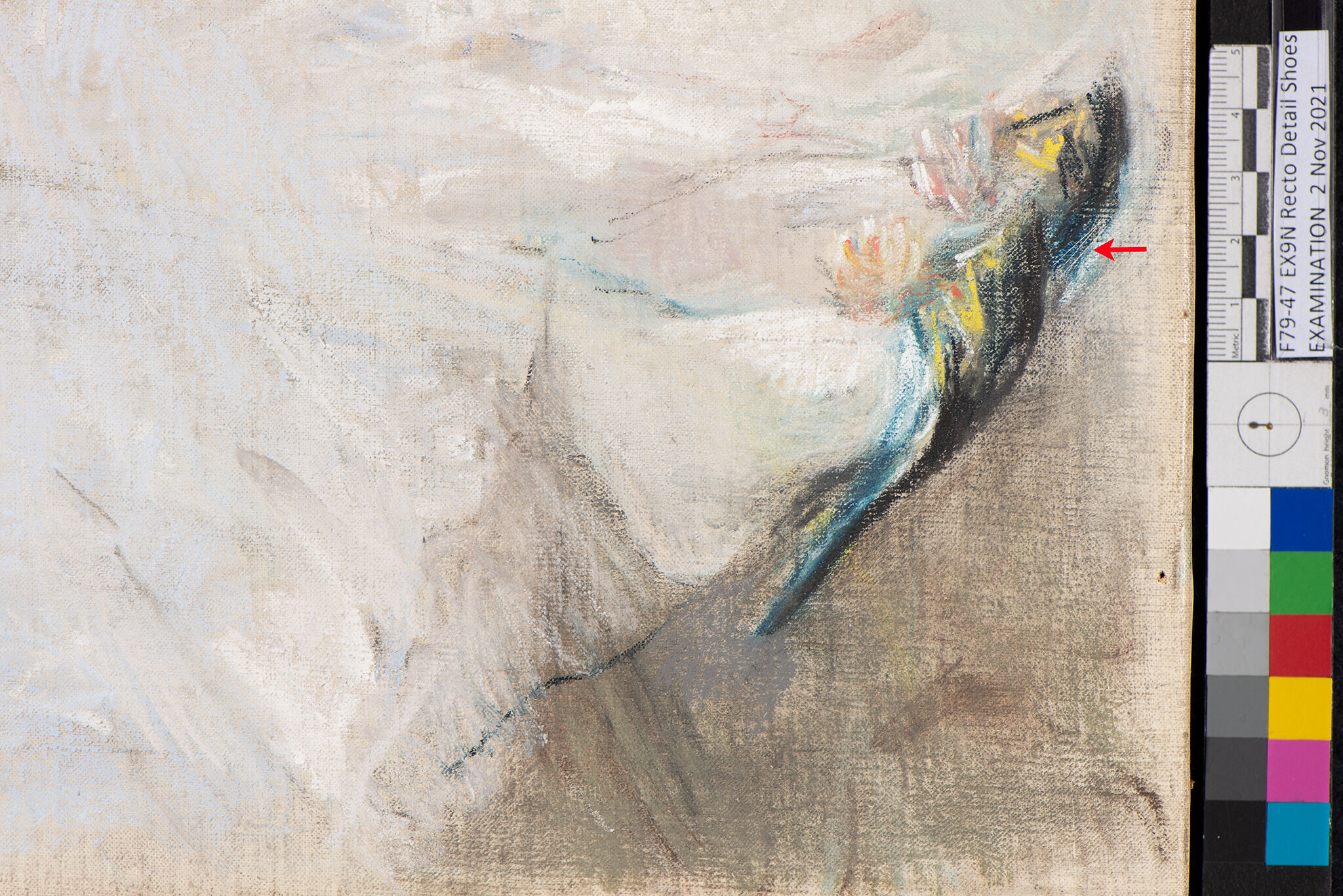

The painting was likely completed in one sitting. Infrared (IR) photographyinfrared (IR) photography: A form of infrared imaging that employs the part of the spectrum just beyond the red color to which the human eye is sensitive. This wavelength region, typically between 700-1,000 nanometers, is accessible to commonly available digital cameras if they are modified by removal of an IR blocking filter that is required to render images as the eye sees them. The camera is made selective for the infrared by then blocking the visible light. The resulting image is called a reflected infrared digital photograph. Its value as a painting examination tool derives from the tendency for paint to be more transparent at these longer wavelengths, thereby non-invasively revealing pentimenti, inscriptions, underdrawing lines, and early stages in the execution of a work. The technique has been used extensively for more than a half-century and was formerly accomplished with infrared film. of the artwork (Fig. 8) shows that Morisot began with an underdrawingunderdrawing: A drawn or painted sketch beneath the paint layer. The underdrawing can be made from dry materials, such as graphite or charcoal, or wet materials, such as ink or paint. in charcoal that indicated the panes of the window, the outlines of the divan, and the sitter, including the approximate location of her legs beneath her skirt, as well as the uchiwa and slippers. Portions of the underdrawing are visible under the overlayers of pastel, and examination of the sitter’s face reveals that pastel was also used in the underdrawing. As she worked, Morisot changed the placement of the proper right shoe and the height and width of the upswept hairstyle.

Morisot’s pastel marks resemble her handling of oil paint: the strokes are fast, delicate, and precisely placed. Per the Purkinje effect, the dominant color is blue, and it appears to be present in the muted grays, light brown, greens, whites, and pinks. Brighter reds, yellows, and vibrant blues were reserved for use in short strokes that highlight the design of the decoration on the uchiwa, the sitter’s slippers, and a reflection or flash of light between the drawn curtains. Strong black strokes appear in the hair ribbon and slippers. Morisot seems to have begun by applying darker colors first. These were frequently blended by smudging or stumpingstumping: Blending, removing, lightening, or softening stokes of powdery media (pastel, charcoal, chalk, or graphite pencil) with a stump or tortillon. The stump is made from paper, leather or thin felt, which is rolled so that it forms a point. If blending is the main object of stumping, then the technique is referred to as stump blending to differentiate between blending with fingers, a brush, or chamois skin., as seen in the upholstery, the pillow behind the sitter’s back, the sitter’s torso and hip, and the walls on either side of the window. Whites and light blues were laid over the darker tones to emphasize the slight transparency of the sitter’s robe, and the skirt was rendered by laying in color with the broad side of a light blue pastel stick and then applying blue, a cool-toned light pink, and white pastel strokes on top. Whites were also used for the highlights on the divan arm and the pillow. The contours of the tufting on the back of the divan were accomplished by applying short strokes of pastel that were blended together, in some areas with a damp brush, and then augmented with lightly blended strokes of pink, green, blue, and red.

Fig. 9. Photomicrograph of the nose and lips. These were applied over an “x” that is visible in infrared (see Fig. 8), Daydreaming (1877).

Fig. 9. Photomicrograph of the nose and lips. These were applied over an “x” that is visible in infrared (see Fig. 8), Daydreaming (1877).

Fig. 10. Detail of the sitter’s face and hair, Daydreaming (1877). The green reflection in the hair is indicated with an arrow.

Fig. 10. Detail of the sitter’s face and hair, Daydreaming (1877). The green reflection in the hair is indicated with an arrow.

Fig. 11. Detail of the uchiwa, Daydreaming (1877)

Fig. 11. Detail of the uchiwa, Daydreaming (1877)

Fig. 12. Detail of the slippers, Daydreaming (1877). The scratches, indicated by the arrow, were made with a sharply pointed stick or the end of a brush.

Fig. 12. Detail of the slippers, Daydreaming (1877). The scratches, indicated by the arrow, were made with a sharply pointed stick or the end of a brush.

Fig. 13. Detail of Berthe Morisot’s signature, Daydreaming (1877)

Fig. 13. Detail of Berthe Morisot’s signature, Daydreaming (1877)

The artwork has been through several framing campaigns. An early framing included attaching spacers to the front of the artwork. Holes from the brads used for attachment can be seen in the center of each edge and a few centimeters from each corner.7Similar placement of brad holes can be found on Manet’s Portrait of Alphonse Moreau (pastel on canvas, prepared with an off-white ground, 547 x 452 mm, The Art Institute of Chicago, bequest of Kate L Brewster, 1950.123). See Rachel Freeman, “Manet, Cat. 18, Portrait of Alphonse Maureau: Technical Report,” in Manet Paintings and Works on Paper at the Art Institute of Chicago (Art Institute of Chicago, 2017), para. 34. Spacers attached with brads are present on The Man with the Dog (pastel on canvas, prepared with an off-white ground, 550 x 350 mm, Art Institute of Chicago, bequest of Brooks McCormick, 2007.287). See Rachel Freeman, “Manet, Cat. 21, The Man with the Dog: Technical Report,” in Manet Paintings and Works on Paper at the Art Institute of Chicago, para. 25. Remnants of blue paper are attached to the tacking margins and back of the stretcher. Over the blue paper are at least three other brown papers that were probably used to seal the back of the frame and protect the back of the painting from dust.

Notes

-

Samuel J. Williamson and Herman Z. Cummins, Light and Color in Nature and Art (New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1983), 170.

-

Commercially prepared grounds came in a range of tints, including ecru and shades of yellow (which were closer to a cream color than yellow). See Anthea Callen, The Art of Impressionism: Painting Technique and the Making of Modernity (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 67. The term écru commonly appears in colormen’s catalogues.

-

See XRF report, November 24, 2021, NAMA conservation file.

-

Fabrique de Couleurs et Vernis; Toiles à Peindre; Carmin, Laques, Jaunes de Chrome de Spooner; Couleurs en Tabettes et en Pastilles, Pastels et Généralement tout ce qui concerne la Peinture et Les Arts; Encres Noires et de Couleurs pour la Typographie et la Lithographie; Fabrique à Grenelle (Paris: Lefranc et Cie, 1862), 47–48. I am grateful to Dr. Kimberly Muir, Art Institute of Chicago, for this reference.

-

Color loss was first noted by Nancy Heugh; see Nancy Heugh, “Technical Examination and Condition Report, French Paintings Catalogue Project: Daydreaming, Berthe Morisot, F79-47,” December 17, 2011, NAMA conservation file.

-

No analysis of the dyes or pigments present in the pastel application has been undertaken at this time.

-

Similar placement of brad holes can be found on Manet’s Portrait of Alphonse Moreau (pastel on canvas, prepared with an off-white ground, 547 x 452 mm, Art Institute of Chicago, bequest of Kate L Brewster, 1950.123). See Rachel Freeman, “Manet, Cat. 18, Portrait of Alphonse Maureau: Technical Report,” in Manet Paintings and Works on Paper at the Art Institute of Chicago (Art Institute of Chicago, 2017), para. 34. Spacers attached with brads are present on The Man with the Dog (pastel on canvas, prepared with an off-white ground, 550 x 350 mm, Art Institute of Chicago, bequest of Brooks McCormick, 2007.287). See Rachel Freeman, “Manet, Cat. 21, The Man with the Dog: Technical Report,” in Manet Paintings and Works on Paper at the Art Institute of Chicago, para. 25.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Berthe Morisot, Daydreaming, 1877,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.634.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Berthe Morisot, Daydreaming, 1877,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.634.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Berthe Morisot, Daydreaming, 1877,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.634.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Berthe Morisot, Daydreaming, 1877,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.634.4033.

Paul-Antoine (1833–1905) and Marguerite Blanche (née Girod, 1844–1901) Bérard, Paris and Wargemont, near Dieppe, France, as Rêverie, by May 25, 1892 [1];

With C. Martin et G. Camentron, Paris, by March 5, 1896;

Auguste Pellerin (1853–1929), Paris, by January 29, 1899–March 27, 1911;

Acquired from Pellerin, through an exchange including Ambroise Vollard, by Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, Paris, March 27, 1911–at least 1933 [2];

With Sam Salz (1894–1981), New York, by 1961 [3];

Leigh B. (1905–87) and Mary Lasker (1904–81) Block, Chicago, by September 1966;

Purchased from the Blocks by E. V. Thaw and Co., Inc., by June 18, 1979 [4];

Purchased from Thaw by Norton Simon (1907–93), Beverly Hills, June 18–November 16, 1979 [5];

Returned by Simon to E. V. Thaw, November 16, 1979;

Purchased from E. V. Thaw and Co., Inc. by The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1979.

Notes

[1] Marie-Louise Bataille and Georges Wildenstein identified the pastel lent by Bérard to the 1892 exhibition, Exposition de Tableaux, Pastels et Dessins par Berthe Morisot, as the Nelson-Atkins pastel. See Bataille and Wildenstein, Berthe Morisot: Catalogue des Peintures, Pastels et Aquarelles (Paris: Les Beaux-Arts, 1961), no. 434, p. 52.

[2] Possible stock no. 18645. On March 27, 1911, Pellerin used Galerie Bernheim-Jeune as his intermediary in an exchange with dealer Ambroise Vollard, where Pellerin acquired Paul Cezanne’s Maison dans les Arbres from Vollard. In exchange, Pellerin gave away several works including the Morisot pastel, Femme sur un canapé. Possibly due to his role in the transaction, Bernheim-Jeune acquired the Morisot pastel. For a complete listing of the exchange, see John Rewald, The Paintings of Paul Cézanne: A Catalogue Raisonné (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1996), 341. It is not clear if the pastel was part of the gallery’s stock or part of the private collection of Jossé (called Joseph, 1870–1941) and Gaston (1870–1953) Bernheim-Jeune; see Henri de Régnier, L’art moderne et quelques aspects de l’art d’autrefois; cent-soixante-treize planches d’après la collection privée de MM. J. et G. Bernheim-Jeune (Paris: Bernheim-Jeune, 1919).

[3] The painting was acquired after January 6, 1943 because it does not appear on the list of paintings imported from France into the United States by Sam Salz from November 1939 to March 1940, nor is it mentioned in his inventory of paintings from January 6, 1943. See National Archives and Records Administration, RG131, Foreign Funds Control Investigative Reports, Box 30, no. N 8-2318, and email from Michelle Bird, curatorial associate, French paintings, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, to Danielle Hampton Cullen, NAMA, July 28, 2021, NAMA curatorial file.

In 1961, the painting was published as being with “A. Th. Sam Sals, New York” in Bataille and Wildenstein, Berthe Morisot: Catalogue des Peintures, Pastels et Aquarelles (Paris: Les Beaux-Arts, 1961), no. 434, p. 52.

[4] See letter from Eugene Victor Thaw to Meghan Gray, NAMA, July 14, 2011, NAMA curatorial files. According to Thaw, the gallery had the pastel for a very short time, as it was purchased by NAMA almost immediately.

[5] See Sara Campbell, Collector Without Walls: Norton Simon and His Hunt for the Best (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010), 426.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Berthe Morisot, Daydreaming, 1877,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.634.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Berthe Morisot, Daydreaming, 1877,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.634.4033.

Berthe Morisot, Woman at the Screen, 1877, oil on canvas, 19 5/16 x 23 1/4 in. (49 x 59 cm), private collection.

Berthe Morisot, Young Woman in Gray Outstretched, 1879, oil on canvas, 23 5/8 x 28 3/4 in. (60 x 73 cm), private collection.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Berthe Morisot, Daydreaming, 1877,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.634.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Berthe Morisot, Daydreaming, 1877,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.634.4033.

3e Exposition de Peinture par MM. Caillebotte, Cals, Cézanne, Cordey, Degas, Guillaumin, Jacques-François, Lamy, Levert, Maureau, C. Monet, B. Morisot, Piette, Pissarro, Renoir, Rouart, Sisley, Tillot [3rd Impressionist Exhibition], 6, Rue Le Peletier, Paris, April 1877, no. 125, as Pastel.

Possibly Exposition de Tableaux, Pastels et Dessins par Berthe Morisot, Boussod, Valadon et Cie, May 25–June 18, 1892, no. 3, as Rêverie.

Berthe Morisot (Madame Eugène Manet): exposition de son œuvre, Galerie Durand-Ruel, Paris, March 5–23, 1896, no. 176, as Rêveuse.

L’Exposition centennale de l’art français de 1800 à 1889, Palais de Fontainebleau, Paris, 1900, no. 506, as Femme étendue sur un divan.

Salon d’Automne, 5ème Exposition: Ouvrages de Peinture, Sculpture, Dessin, Gravure, Architecture et Art décoratif; Exposition Rétrospective d’Œuvres de Berthe Morisot, Grand Palais, Paris, October 1–22, 1907, no. 153, as Intérieur.

Expositions d’Œuvres des XIXe et XXe siècles, Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, Paris, June–July 1925, no. 97, as Femme sur un canapé.

Exposition d’Œuvres de Berthe Morisot au Profit des “Amis du Luxembourg”, Chez MM. Bernheim-Jeune, Paris, May 6–24, 1929, no. 164, as Femme sur un canapé.

Possibly Exhibition of Masterpieces: French and American 19th Century Paintings, Wildenstein, New York, Summer 1947, no. 18, as Young Woman Reclining.

One Hundred European Paintings and Drawings from the Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Leigh B. Bloch, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, February 2–April 14, 1968, no. 7, as Woman on the Sofa.

Impressionism: Selections from Five American Museums, The Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, November 4–December 31, 1989; The Minneapolis Institute of Arts, January 27–March 25, 1990; The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, March 21–June 17, 1990; The Saint Louis Art Museum, July 14–September 9, 1990; The Toledo Museum of Art, September 30–November 25, 1990, hors cat. (Kansas City only), as Portrait of a Woman in White (Reverie).

References

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Berthe Morisot, Daydreaming, 1877,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.634.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Berthe Morisot, Daydreaming, 1877,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.634.4033.

Catalogue de la 3e Exposition de Peinture par MM. Caillebotte, Cals, Cézanne, Cordey, Degas, Guillaumin, Jacques-François, Lamy, Levert, Maureau, C. Monet, B. Morisot, Piette, Pissarro, Renoir, Rouart, Sisley, Tillot, exh. cat. (Paris: Imprimerie E. Capiomont et V. Renault, 1877), 10 [repr. in Theodore Reff, ed., Modern Art in Paris: Two-Hundred Catalogues of the Major Exhibitions Reproduced in Facsimile in Forty-Seven Volumes, vol. 23, Impressionist Group Exhibitions (New York: Garland, 1981), unpaginated], as Pastel.

Possibly A. P., “Beaux Arts,” Le Petit Parisien 2, no. 173 (April 7, 1877): 2.

Possibly C. D., “L’Exposition des impressionnistes,” Le Petit Moniteur Universel, no. 98 (April 8, 1877): 2.

Léon de Lora, “L’Exposition des impressionnistes,” Le Gaulois, no. 3094 (April 10, 1877): 2, as Jeune femme couchée.

Jacques, “Menus Propos: Exposition impressionnistes,” L’Homme Libre (April 12, 1877): 2.

Georges Rivière, “L’Exposition des impressionnistes,” L’impressionniste, no. 2 (April 14, 1877): 4.

Possibly Charles Bigot, “Causerie Artistique: L’Exposition des ‘impressionnistes’,” La Revue politique et littéraire 6, no. 44 (April 28, 1877): 1048.

Fréderic Chevalier, “Les Impressionnistes,” L’Artiste: Revue de Paris, Historie de l’art contemporain 48, no. 1 (May 1, 1877): 332.

Georges Rivière, “Les Intransigeants et les impressionnistes: Souvenirs du salon libre de 1877,” L’Artiste 2, no. 49 (November 1, 1877): 300.

Possibly Exposition de Tableaux, Pastels et Dessins par Berthe Morisot, exh. cat. (Paris: Boussod, Valadon et Cie, 1892), unpaginated [repr. in Theodore Reff, ed., Modern Art in Paris: Two-Hundred Catalogues of the Major Exhibitions Reproduced in Facsimile in Forty-Seven Volumes, vol. 43, Exhibitions of Impressionist Art I (New York: Garland, 1981), unpaginated], as Rêverie.

Berthe Morisot (Madame Eugène Manet): exposition de son œuvre, exh. cat. 2nd ed. (Paris: Durand-Ruel, 1896), 31, as Rêveuse.

Possibly Claude Bienne, “Exposition de l’Œuvres de Berthe Morisot,” La Revue Hebdomadaire 5, 46 (March 1896): 470.

Arsène Alexandre, “l’Œuvre de Mme Berthe Morisot,” Le Figaro 42, no. 66 (March 6, 1896): 5.

Catalogue officiel illustré de l’exposition centennale de l’art français de 1800 à 1889, exh. cat. (Paris: Imprimeries Lemercier, 1900), 212 [repr. in Theodore Reff, ed., Modern Art in Paris: Two-Hundred Catalogues of the Major Exhibitions Reproduced in Facsimile in Forty-Seven Volumes, vol. 7, World’s Fair of 1900 (New York: Garland, 1981), unpaginated], as Femme étendue sur un divan.

André Fontainas, “L’exposition centennale de la peinture française,” Mercure 7, no. 127 (July–September 1900): 157, as Femme étendue sur un divan.

Salon d’Automne, 5ème Exposition: Catalogue des Ouvrages de Peinture, Sculpture, Dessin, Gravure, Architecture et Art décoratif; Exposition Rétrospective d’Œuvres de Berthe Morisot, exh. cat. (Paris: Compagnie Française des Papiers-Monnaie, 1907), unpaginated, as Intérieur.

André Pératé, “Le Salon d’Automne,” Gazette des Beaux-Arts, no. 605 (November 1, 1907), 392.

Roger Marx, “Les Femmes Peintres et l’Impressionnisme: Berthe Morisot,” Gazette des Beaux-Arts, no. 606 (December 1, 1907): 304, 498–99, (repro.), as Le Femme en peignoir rose.

Louis Rouart, “Berthe Morisot (Mme Eugène Manet) 1841–1895,” Art et Décoration: Revue Mensuelle d’art Moderne, no. 5 (May 1908): 174, (repro), as Intérieur.

Roger Marx, Maîtres d’hier et d’aujourd’hui (Paris: Calmann-Lévy, 1914), 310, as Femme en peignoir rose.

Henri de Régnier, L’art moderne et quelques aspects de l’art d’autrefois; cent-soixante-treize planches d’après la collection privée de MM. J. et G. Bernheim-Jeune (Paris: Bernheim-Jeune, 1919), unpaginated, (repro.), as La Femme à l’éventail.

Expositions d’Œuvres des XIXe et XXe siècles, exh. cat. (Paris: Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, 1925), unpaginated, as Femme sur un canapé.

Exposition d’Œuvres de Berthe Morisot au Profit des “Amis du Luxembourg”, exh. cat. (Paris: Moderne Imprimerie, 1929), unpaginated, as Femme sur un canapé.

Monique Angoulvent, Berthe Morisot (Paris: Albert Morancé, 1933), no. 93, p. 122, (repro.), as Jeune fille en rose (Rêveuse).

Lionello Venturi, Les Archives de l’impressionnisme (Paris: Durand-Ruel, 1939), 2:319.

Possibly Exhibition of Masterpieces: French and American 19th Century Paintings, exh. cat. (New York: Wildenstein, 1947), unpaginated, as Young Woman Reclining.

Possibly Howard Devree, “By Groups,” New York Times 96, no. 32663 (June 29, 1947), 6X, as Young Woman Reclining.

Marie-Louise Bataille and Georges Wildenstein, Berthe Morisot: Catalogue des Peintures, Pastels et Aquarelles (Paris: Les Beaux-Arts, 1961), no. 434, pp. 52, 225, (repro.), as Rêveuse.

Francine Du Plessix, “Collectors: Mary and Leigh Block,” Art in America 54, no. 5 (September–October 1966): 69, (repro.), as Woman on a Sofa.

One Hundred European Paintings and Drawings from the Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Leigh B. Bloch, exh. cat. (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1968), unpaginated, (repro.), as Woman on the Sofa.

The Collector in America, compiled by Jean Lipman and the Editors of Art in America (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1971), 109, (repro.).

Donald Hoffman, “Gallery Acquires Degas, Morisot,” Kansas City Star 100, no. 65 (December 2, 1979): 6E, as The Dreamer.

Donald Hoffman, “Intensity and nuance: the Nelson’s new pastels: Impressionist masterworks by Degas and Morisot,” Kansas City Star 100, no. 77 (December 16, 1979): 3, 24-26, (repro.), as The Dreamer.

Rosalind C. Truitt, “What’s new? To find out, take a break and visit the Nelson Gallery,” Kansas City Times 100, no. 267 (July 15, 1980): A6, as Rêveuse.

Donald Hoffman, “The Nelson gets first prize for new artworks,” Kansas City Star 100, no. 263 (July 20, 1980): 4E, as The Dreamer.

Donald Hoffmann, “Benefactors’ gifts help keep inflation at bay at the Nelson,” Kansas City Star 101, no. 225 (June 7, 1981): 1F.

Sophie Monneret, L’Impressionnisme et son Époque (Paris: Éditions Denoël, 1981), 2: 90, 3: 159, as Pastel and Femme étendue sur un divan.

Jean Dominique Rey, Berthe Morisot (Paris: Flammarion, 1982), 41.

Charles S. Moffett, The New Painting: Impressionism 1874–1886, exh. cat. (Geneva: Richard Burton SA, 1986), 205.

Jane Roberts, Growing Up with the Impressionists: The Diary of Julie Manet (London: Sotheby’s Publications, 1987), 159, as Femme en rose sur un canapé.

Charles F. Stuckey and William P. Scott, Berthe Morisot: Impressionist, exh. cat. (New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1987), 72, 74, (repro.), as Daydreaming.

Suzanne G. Lindsay, “Berthe Morisot and the Poets: The Visual Language of Woman,” Helicon Nine: The Journal of Women’s Arts and Letters, no. 19 (Summer 1988): 11, 15, 17, (repro.), as Day-Dreaming (Rêveuse).

Kathleen Adler, Perspectives on Morisot (New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1990), 55, 56n34, 84.

Roger Ward, “Selected Acquisitions of European and American Paintings at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, 1986–1990,” Burlington Magazine 133, no. 1055 (February 1991).

Roger Ward and Patricia J. Fidler, eds., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collection (New York: Hudson Hills Press, in association with Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1993), 208, (repro.), as Daydreaming.

“New Lecture Series Debuts in September,” Newsletter (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (Summer 1995): 8, (repro.), as Daydreaming.

Ruth Berson, The New Painting: Impressionism, 1874–1886: Documentation, Exhibited Works, new ed. (San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1996), no. III-125, pp. 1:119, 139, 142, 157, 162, 174, 183, 186; 2:78, 97, (repro.), as Pastel.

John Rewald, The Paintings of Paul Cézanne: A Catalogue Raisonné (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1996), 341, as Femme sur un canapé.

Margaret Shennan, Berthe Morisot: The First Lady of Impressionism (Gloucestershire, England: Sutton, 2000), 183, 185, as Dreaming (Rêveuse).

Sylvie Patry and et al., Berthe Morisot, 1841–1895, exh. cat. (Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 2002), 178, 186–87, (repo.), as La Rêveuse.

Richard Shone, French Impressionist Painting: The Janice H. Levin Collection, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2003): 78, 80, (repro.) as Daydreaming.

Norio Shimada, The History of Impressionism, exh. cat. (Tokyo: Shōgakukan, 2004), 150–51, (repro.).

Frances Borzello, At Home: The Domestic Interior in Art (New York: Thames and Hudson, 2006), 58–59, 189, (repro.), as Daydreaming (Rêveuse).

Keiko Sakagami, Berthe Morisot, exh. cat. (Tokyo: Shogakukanm, 2006), 32, (repro.).

Pierre Sanchez, Dictionnaire du Salon d’Automne: Répertoire des Exposants et Liste des Œuvres Présentées, 1903–1945 (Dijon: Échelle de Jacob, 2006), 3:1007, as Intérieur.

Hugues Wilhelm, Berthe Morisot, 1841–1895: A Retrospective, exh. cat. (Tokyo: APT International, 2007), 74–75, (repro.), as Dreamer (Rêveuse).

Deborah Emont Scott, ed., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collection, 7th ed. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2008), 120, (repro.), as Daydreaming.

Ingrid Pfeiffer and Max Hollein, ed., Women Impressionists, exh. cat. (Frankfurt am Main: Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, 2008), 69, (repro.), as Dreaming Girl.

Sara Campbell, Collector Without Walls: Norton Simon and His Hunt for the Best (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010), 426, (repro.), as Daydreaming.

Alex Danchev, Cézanne: A Life (New York: Pantheon Books, 2012), 273.

Cindy Kang et al., Berthe Morisot: Female Impressionist, exh. cat. (New York: Rizzoli Electa, 2018), 126, as The Dreamer.

Christopher Lloyd, Impressionist and Post-Impressionist Drawings (London: Thames and Hudson, 2019), 138, 144, (repro.), as Daydreaming.